Abstract

We distinguish between two types of interrogative particles, (regular) question particles and polar question particles. The first, canonically exemplified by Japanese -ka, occurs in all interrogatives, in matrix as well as embedded contexts. The second, the object of the present study, is exemplified by the Hindi-Urdu particle kya:. Polar kya: occurs in polar questions but not in wh questions, and it occurs optionally in matrix questions but only in a restricted way in embedded questions. We analyze this particle as presupposing that its prejacent denotes a singleton propositional set and as partitioning the questioned proposition into two parts that can be characterized as at-issue and not at-issue. These two aspects of its meaning are shown to capture several facets of the behavior of the polar question particle kya: that have not previously been analyzed or even systematically described. The paper also touches upon well-known phenomena, such as interrogative selection and alternative questions, but from a new perspective and opens up a way of looking at interrogative particles in other languages that do not seem to neatly fit the mold of regular question particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper has two inter-related foci, one specific to Hindi-UrduFootnote 1 and the other more general. Its empirical focus is a particular lexical item in Hindi-Urdu that we refer to as polar kya:. We identify various syntactic restrictions on its occurrence and provide a descriptively adequate account of those restrictions. Its theoretical contribution is to leverage the account of polar kya: to draw a distinction between two types of interrogative particles that have often been grouped together. One type of interrogative particle is the one typically referred to as a Q-morpheme. We take this to be the overt realization of C[+Q]. The other we call a polar question particle (PQP), which occurs only in a subset of clause-types marked C[+Q]. The first class is well-established in the literature, with Japanese -ka and -no as prototypical examples. The second class is exemplified by Hindi-Urdu polar kya:, the new kid on the block.

We begin by introducing the signature properties of the Hindi-Urdu polar question particle in Sect. 2: its restriction to polar questions, its flexible syntactic positioning, and its selectiveness in appearing inside embedded polar questions. In Sect. 3, we present diagnostics distinguishing polar question particles from a clause-typing Q-morpheme. We analyze the Hindi-Urdu PQP kya: as having a presupposition that targets polar questions exclusively and we locate it high in the left periphery, at a structure with the prosodic profile of matrix polar questions. We also account for its clause-internal distribution. In Sect. 4, we consider the pragmatic contribution of kya:. We present diagnostics to establish that it partitions the clause into a segment that is not open to challenge and a segment that is unspecified in this respect and may be challenged. The precise distinctions that arise from this partition are shown to follow from independently motivated constraints that are operative in the grammar of Hindi-Urdu. Section 5 deals with two issues that arise when we consider polar kya: in connection with disjunction. One bears on the presupposition we ascribe to it, the other is an unexpected restriction against final kya:. We conclude in Sect. 6 by noting two domains of inquiry that our analysis of polar question particles opens up. The overall message we try to highlight is that Hindi-Urdu polar kya: belongs to a class of items that has not so far been given formal recognition but for which there is cross-linguistic evidence in the literature.

2 Properties of the polar particle kya:

In this section we establish that the particle kya: is restricted to polar questions, that it can occur almost anywhere within a clause, that it can appear in matrix as well as embedded clauses, albeit with some restrictions.

2.1 Hindi polar questions and kya:

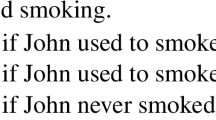

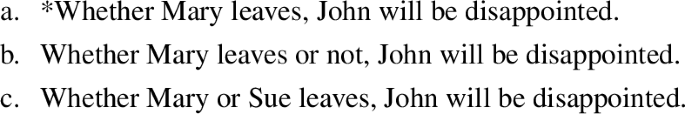

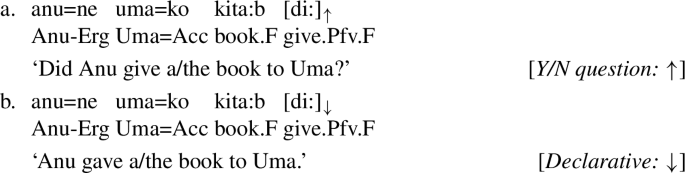

To an initial approximation, polar questions, also known as Yes/No questions, have rising intonation on the verbal complex in Hindi-Urdu, whereas declaratives generally have falling intonation.Footnote 2 Butt et al. (2017) and Biezma et al. (2017) associate rising intonation with L/H-H% and falling intonation with L-L% in (1).

-

(1)

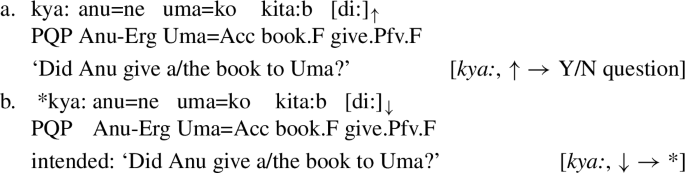

Unlike English, they do not involve inversion of the finite verb. The characteristic prosody noted above is, however, obligatory for a Y/N question interpretation. Y/N questions optionally co-occur with the wh-word kya:. It should be noted that the presence of the polar particle kya: does not make the characteristic prosody optional. Note also that despite the presence of this prosody, Hindi-Urdu polar questions are neutral questions unlike English declarative questions (Bartels 1997; Gunlogson 2003, see also Jeong 2018; Farkas and Roelofsen 2017, and Westera 2018).

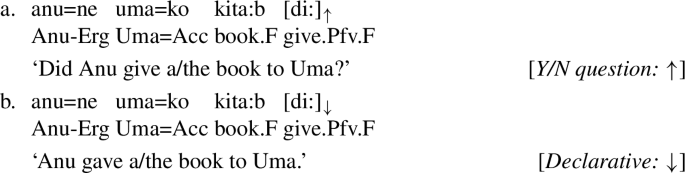

-

(2)

In (2), kya: is not the argument of any predicate. But kya: can also function as an argument of a predicate with the meaning ‘what.’

-

(3)

To distinguish these two cases, we dub the athematic kya: in (2) the polar question particle kya: and gloss it as ‘PQP,’ short for ‘Polar Question Particle.’ The kya: in (3), we call thematic kya:. Butt et al. (2017) note that the polar particle kya: has a flat intonation while the thematic kya: has a H* pitch accent, which accent also appears more generally on wh-phrases in Hindi-Urdu.Footnote 3

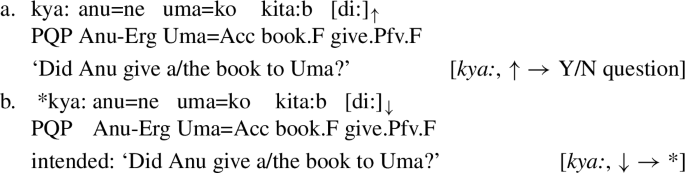

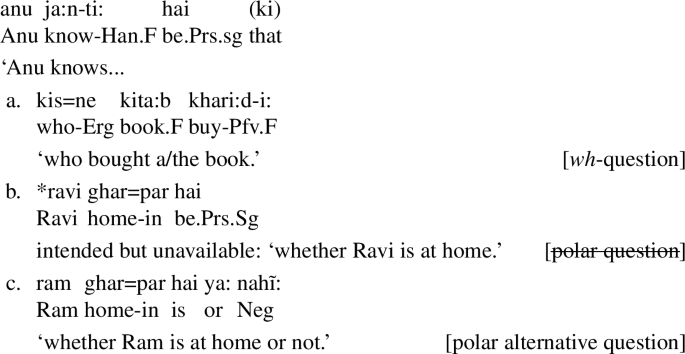

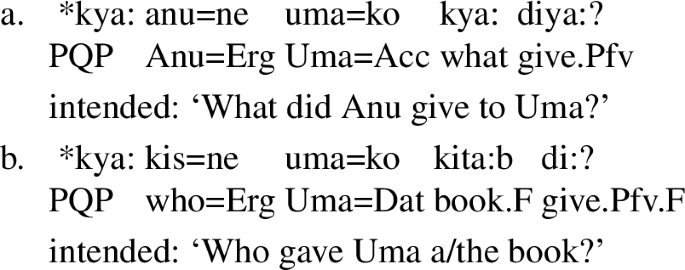

Polar kya: does not appear in constituent questions.

-

(4)

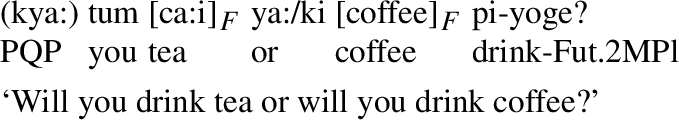

Polar kya: can appear in alternative questions; we will argue that its appearance there follows from its appearance in Y/N questions.

-

(5)

2.2 The basic distribution of polar kya:

The most unmarked location for polar kya: is the clause-initial position. But it can appear in almost any other position. It can be clause-medial or clause-final.Footnote 4

-

(6)

In an almost mirror image pattern, thematic kya: is natural in the immediately pre-verbal position but odd/marked elsewhere.Footnote 5

-

(7)

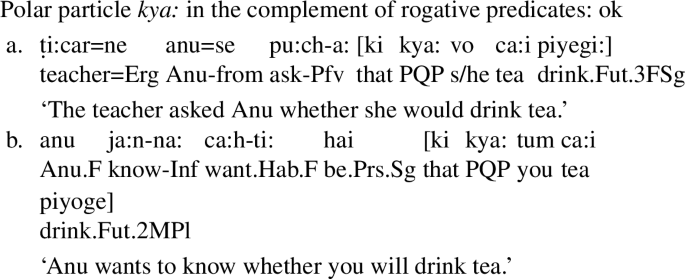

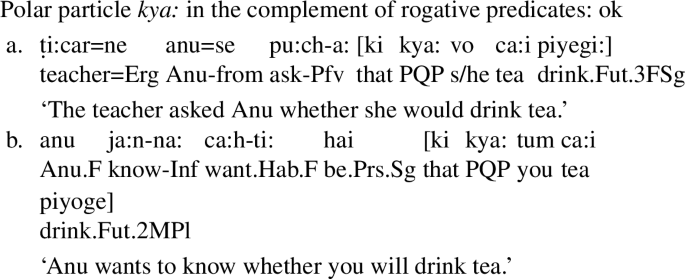

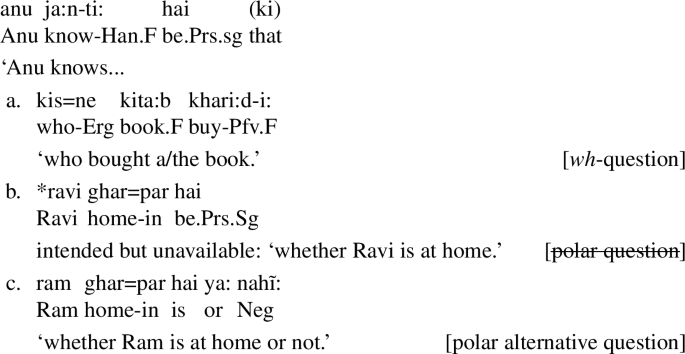

All else being the same, one might expect that the distribution of polar kya: in embedded clauses would simply track the distribution of embedded Y/N questions. However, this expectation is not borne out. To a first approximation, polar kya: can only appear in complements of rogative predicates, predicates that take only interrogative complements, but not in complements of responsive predicates, predicates that take interrogative as well as declarative complements. Note that the Hindi-Urdu complementizer ki tracks finiteness but is otherwise compatible with declarative, interrogative and subjunctive clauses.

-

(8)

-

(9)

Note that in (9b), the predicate that takes the embedded question as a complement is ja:n ‘know’, which is a responsive predicate but in combination with the attitude predicate ca:h ‘want’ functions like a rogative.

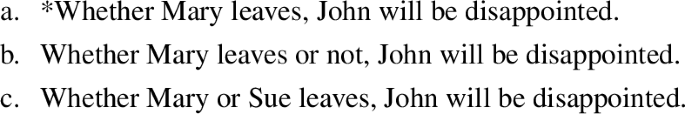

2.3 Embedded polar kya: and embedded inversion in English

We confirmed the unavailability of polar kya: in complements of the responsive predicate ja:n ‘know’ by searching the Corpus Of Spoken Hindi (COSH) using the COSH Conc [Software].Footnote 6 There was no shortage of embedded kya: questions in the corpus but we did not find cases like (8). We did find cases of polar kya: under responsives but only under specific conditions. In each of the following examples, the responsive combines with another operator.

-

(10)

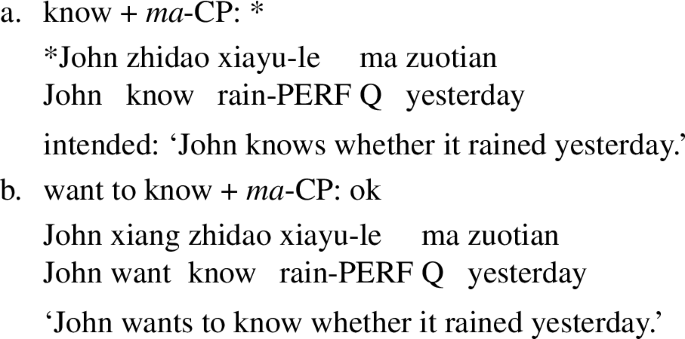

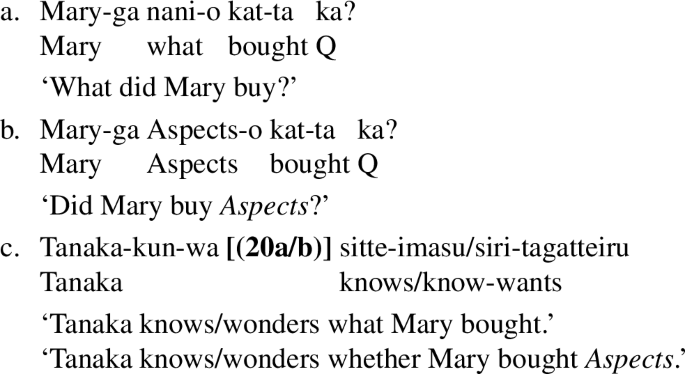

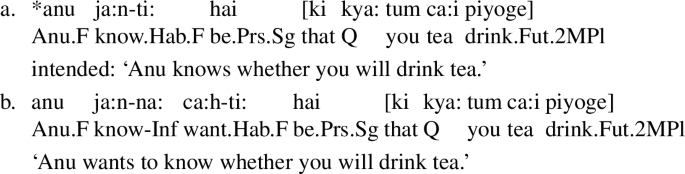

The responsive versus rogative distinction that we see in the distribution of embedded polar kya: has been noted by McCloskey (2006) to play a role in the distribution of embedded inversion in English.Footnote 7

-

(11)

As indicated in the schematic version of these examples, McCloskey takes the possibility of embedded inversion as indicating the presence of additional CP-structure but he goes on to note that the distribution of embedded inversion cannot be reduced to the choice of embedding predicate. As the following example shows, the responsive predicate know can combine with embedded inversion if it is part of a larger structure want to know.

-

(12)

Everybody wants to know [did I succeed in buying chocolate for Winifred].

A question that arises about such examples is whether the complement clause is a quotation. McCloskey gives detailed arguments against this possibility from pronominal binding and sequence of tense. Here we note that if the complement clause in (12) was a quote, I would be bound by everybody but this particular sentence is noted by McCloskey to be a a naturally occurring sentence where I refers to the speaker in the context.

McCloskey also notes that questioning or negating the responsive improves the acceptability of embedded inversion.

-

(13)

-

a.

*I remember was Henry a communist.

-

b.

Do you remember was Henry a communist?

-

c.

?I don’t remember was Henry a Communist.

-

a.

It is striking that in Hindi-Urdu some of the same features modulate the acceptability of embedded polar kya: with responsives, as we have already seen in (9b) and (10). In fact the parallelism extends to question complements of nouns. Compare (14a) from COSH with (14b) from Gunlogson (2003).

-

(14)

Further examples could be constructed to show the parallel between English embedded inversion and Hindi-Urdu embedded PQPs but we believe that we have established the pattern sufficiently. The distribution of the Hindi PQP kya:, then, is not as arbitrary as it might seem at first glance. When seen in the broader perspective of what Dayal and Grimshaw (2009) label quasi-subordination, it appears quite systematic. It appears in matrix polar questions and in quasi-subordinated embedded polar questions. We started with the responsive/rogative distinction but it has turned out not to be what underlies the distribution of embedded inversion in English and embedded kya: in Hindi-Urdu. We have already seen examples of modified responsives that can take kya: complements and Dayal (2019) notes that there is a class of rogative predicates that do not allow embedded inversion in English or embedded kya: in Hindi-Urdu.

-

(15)

3 The syntactic and semantic contribution of polar particle kya:

In this section we work towards an account of polar particle kya:, focusing on its distributional properties. We first discuss the possibility that it functions as a clause-typing particle. We then offer an alternative in which it is a particle that is situated higher in the left periphery than CP and which selects for singleton propositional sets. We also discuss how kya: can appear in different positions in the clause.

3.1 What polar particle kya: is not

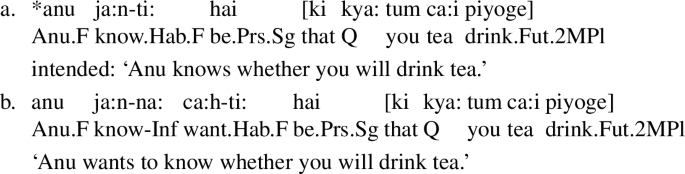

A plausible first pass at analyzing polar particle kya: is to treat it as a Q-morpheme, that is optionally overt. Indeed, this is how Cheng (1991:21) characterizes its role. There is, however, good reason to doubt that kya: is a marker of the clause type interrogative. Consider the contrast in embedding possibilities that we have been studying.

-

(16)

We have seen that the contrast above represents a more general pattern. Polar particle kya: does not seem to embed under responsive predicates but it can be embedded under rogative predicates. We saw in Sect. 2 that matrix polar questions do not differ syntactically from their declarative counterparts. Their status as interrogatives is signaled by a rising vs. a falling intonation. However, the situation is different in embedded positions, where prosody cannot play the same role. (17) shows that responsive predicates cannot take such a complement under an indirect question interpretation.

-

(17)

We note that in order to get an indirect question interpretation, the embedded clause must be a polar alternative question, with an overt disjunction plus negation ya: nahĩ: ‘or not’. Interestingly, we cannot add kya: in this case, as shown in (18b):

-

(18)

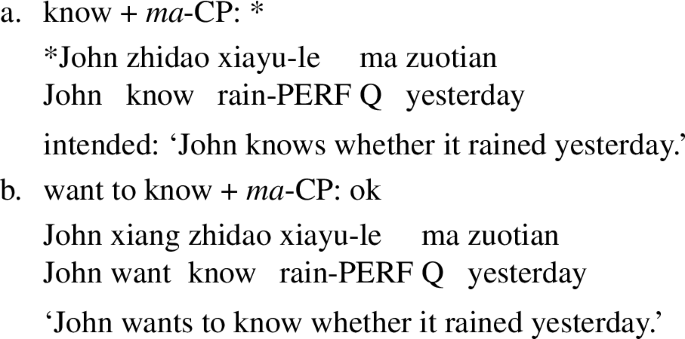

The contrast between responsive and rogative predicates with respect to embeddability of kya: is replicated in Mandarin, with respect to the particle ma, which Cheng treats in the same terms as Hindi kya:.Footnote 8

-

(19)

The facts discussed here establish that Hindi-Urdu kya:, and Chinese ma by extension, is not the yes/no operator. If it were, it would be able to occur optionally or obligatorily in all embedded positions. It is also not a straightforward clause-typing particle, marking an interrogative clause. If it were, one would again expect it to occur in all cases of embedding. One could even argue that such a particle might be obligatory when embedded under responsive predicates where there may be more functional pressure to distinguish between declarative and interrogative structures.

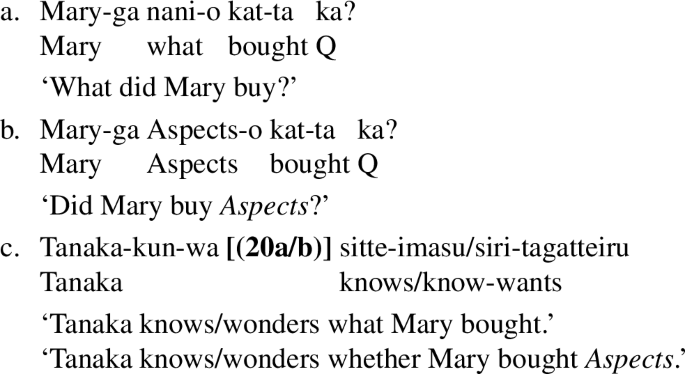

The crucial point for us is to distinguish Hindi-Urdu kya: and Chinese ma from straightforward Question Particles like Japanese -ka/-no, which are not subject to the restrictions found with kya:. The Japanese Q-morpheme, then, exemplifies the kind of clause-typing that was proposed by Cheng (1991).

-

(20)

One analysis that is compatible with the restricted distribution of polar particle kya: and may still qualify as a form of clause typing is to take kya: to occur in a projection above CP, let’s call it ForceP. We wish to emphasize though that this would be different from clause-typing of the Japanese kind which targets all questions. In fact, this account of polar kya: mirrors the analysis proposed by McCloskey (2006) to explain the parallel facts about inversion in English discussed in Sect. 2.3. McCloskey entertains the possibility that some predicates can only take regular CP complements that denote questions, while others may also take ForceP complements that denote the question speech actFootnote 9:

-

(21)

-

a.

(wonder): [[C []]]

-

b.

(know): [C []]

-

a.

Our claim, then, is that kya: is only acceptable in the complements of predicates that can take ForceP. These are canonically the set of rogative predicates. However, as we have seen, there are some cases where kya: can occur in the complement of responsive predicates if those predicates are negated or questioned. We have also seen the case of a rogative predicate that does not take embedded kya:. We set aside the issue of why selection of a complement should be a fluid matter, and focus here on the fact that the fluidity is entirely systematic and in keeping with the proposal to treat kya: as occurring in a projection above CP, which we are taking to be ForceP.Footnote 10

3.2 What polar kya: is

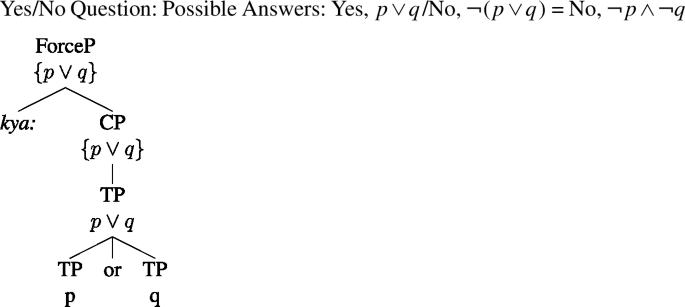

The issue we will now address is the fact that polar particle kya: is acceptable in Y/N questions but not in wh-questions. In addressing this, we will assume that Y/N questions differ from wh-questions in denoting singleton sets of propositions:

-

(22)

The view that wh-questions denote a set with more than one member is standard. It rests on the view that wh-phrases must range over a plural domain in order for the conditions for proper questioning to be satisfied. That is, a question like (22a) carries an existential presupposition that someone left and an uncertainty presupposition about who that person may be. An insight going back to Bolinger (1978), and recently revived in the literature, is that Y/N questions are fundamentally different in privileging the nucleus proposition. A yes answer or a no answer can then be treated as anchored to this proposition. See Gawron (2001), van Rooij and Šafářová (2003), Biezma (2009), Farkas and Bruce (2010), Biezma and Rawlins (2012), Krifka (2013) and Roelofsen and Farkas (2015). In line with the spirit of these works, we propose that the basic denotation of (22b) would be the singleton set {John left}.

We now show how this independently motivated distinction can help explain the distribution of polar kya:, drawing on the account of similar restrictions discussed by Xu (2012, 2017) in connection with the Mandarin particle nandao. We define kya: as an expression that encodes a presupposition that its complement is a singleton set:Footnote 11

-

(23)

\(\mbox{$[\![ \text{\textit{kya:}} ]\!]^{}$} = \lambda Q_{(st)t}: \exists p \in Q [\forall q [q \in Q \to q = p]]. Q\)

Since kya: is defined on a set of propositions, it rules out kya: with declarative statements. It further restricts kya: to a subset of questions, namely those with just one proposition. Wh-questions, as we have just discussed, do not pass the requirement of singularity.Footnote 12 Interestingly, neither do alternative questions. This may appear to be a potential problem for our account as we have seen that kya: is fully acceptable in alternative questions like (5). We will return to this in Sect. 5, where we will see that appearances notwithstanding, the pattern falls well within the terms of our account.

Our proposal relies on a type distinction between declaratives and interrogatives. We have further assumed that polar questions are distinguished by being singleton sets from other types of questions. A reviewer points out that it is possible to distinguish polar questions from declaratives as well as other kinds of interrogatives semantically without making these assumptions. This can be done by replacing the singleton requirement of kya: by a requirement that kya: presupposes that the clause it combines with highlights a single proposition. The notion of highlighting is as in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015). This would be the way forward in theories which do not make a type distinction between declaratives and interrogatives (see Roelofsen 2019 and Uegaki 2019). In fact, Xu (2017), that we mentioned earlier, does precisely this for Mandarin nandao.

3.3 Intonation and Hindi-Urdu Yes/No Questions

At this point, we would like to clarify our assumptions about the connection between our syntactic proposal and the intonation associated with Hindi-Urdu Yes/No Questions. We do this by introducing a problem in the syntax and semantics of Hindi-Urdu that is independent of the issue of polar question particles. Consider the paradigm in (24).

-

(24)

The examples in (24a, c) tell us that Hindi-Urdu has the same pattern of embedding questions as English. For this reason we allow Hindi-Urdu responsive predicates to take CP complements headed by C[+Q], where we take \(\mbox{$[\![ \text{C[+Q]} ]\!]^{}$}\) to denote λqλp[p = q]] as proposed, for example, in von Stechow (1996). The only point of cross-linguistic variation is the indirect question interpretation of the polar question in (24b). We believe that in English the presence of the complementizer if/whether allows for an indirect question interpretation while Hindi-Urdu requires matrix clause intonation for this purpose. Footnote 13 This makes embedding polar questions, in effect, a root phenomenon in Hindi-Urdu since the indirect question interpretation piggy-backs on rising intonation, which may well be a root phenomenon cross-linguistically.Footnote 14

Here is a prediction that follows from our account. Consider the following sentence.

-

(25)

In principle, the complement in this sentence has two possible parses, as [C…] and as [↑ [C…] . But the first option (=CP) is ruled out analogously to (24b). The second option (=ForceP) saves the sentence but it brings with it a short prosodic break after the matrix clause and the prosody of matrix polar questions on the complement. And, not surprisingly, it becomes possible to have kya: in the embedded clause: ki kya: dharti: gol hai.

The crucial role of intonation in licensing monoclausal yes/no questions raises issues that are independently interesting. We refer the reader to Dayal (2019) for further discussion. For present purposes the following points are important. Rising intonation of the kind seen in matrix Yes/No questions is associated with ForceP[+Q], in embedded contexts rising intonation shows the hallmarks of embedded root phenomena and, to the extent that we only see kya: in the presence of rising intonation, we consider PQPs to also be an embedded root phenomenon.Footnote 15 Note that a ForceP[+Q] associated with a Yes/No question may or may not have a kya:. But such a ForceP is always associated with rising intonation.Footnote 16

3.4 Deriving non-initial kya:

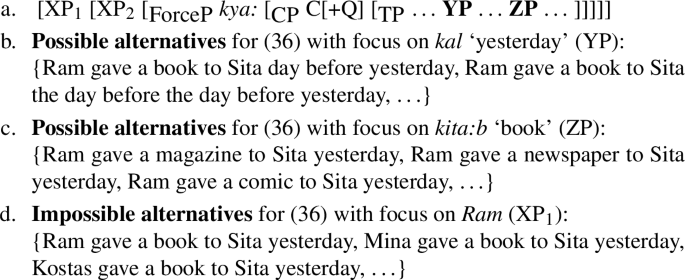

We now come to the third part of the distributional puzzle, which has to do with the position of the polar question particle kya: within the clause it occurs in. The various possibilities for the occurrence of kya: can be derived by assuming the base structure in (26) followed by movement to the left of kya: as illustrated in (27).

-

(26)

[kya: [C[+Q] [anu-ne uma-ko kita:b di:]]]

-

(27)

Some support for the movement proposal comes from the fact that kya: is difficult after weak indefinites like kuch ‘something’ and idiomatic expressions, which are elements whose movement leads to deviance.Footnote 17

-

(28)

According to our proposal, the appearance of the polar question particle kya: in an immediately pre-verbal position in (28) indicates that the pre-kya: material has moved over kya:. In (28), we have direct objects that are resistant to movement, as shown by the following contrasts.

-

(29)

-

(30)

Since the direct objects in (28) are resistant to movement, it follows that the variants of (28a, b) where the polar particle kya: is immediately pre-verbal are deviant. That the deviance of immediately pre-verbal polar particle kya: is related to the movement potential of the direct object is shown below. Here we have an object that can move freely and we find that kya: can appear in an immediately pre-verbal position without deviance.

-

(31)

Following a similar logic as for the above examples, clause-final kya: is derived by scrambling of the whole finite clause to the left of kya:.

-

(32)

This accounts for the attested word order variations observed with respect to kya:.

4 The pragmatic contribution of polar particle kya:

In this section we consider the pragmatic contribution of kya:. Starting with non-initial kya: we present diagnostics to establish that kya: partitions the clause into a segment that is not open to challenge and a segment that is unspecified in this respect and may be challenged. The precise distinctions that arise from this partition are determined by independently motivated constraints that are operative in the grammar of Hindi-Urdu.

4.1 kya: Induced partitions

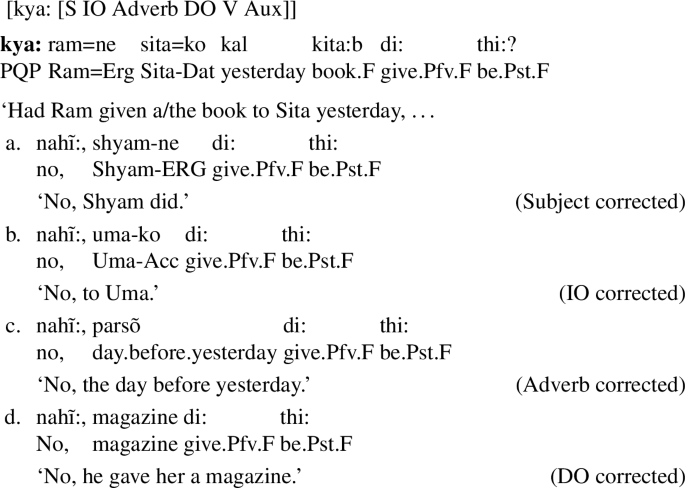

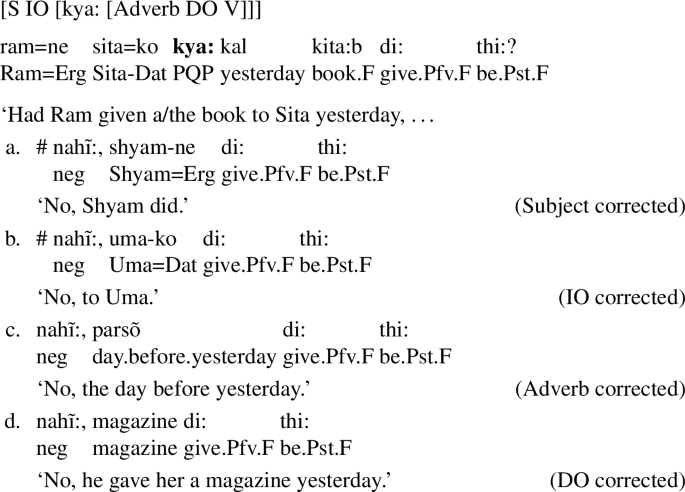

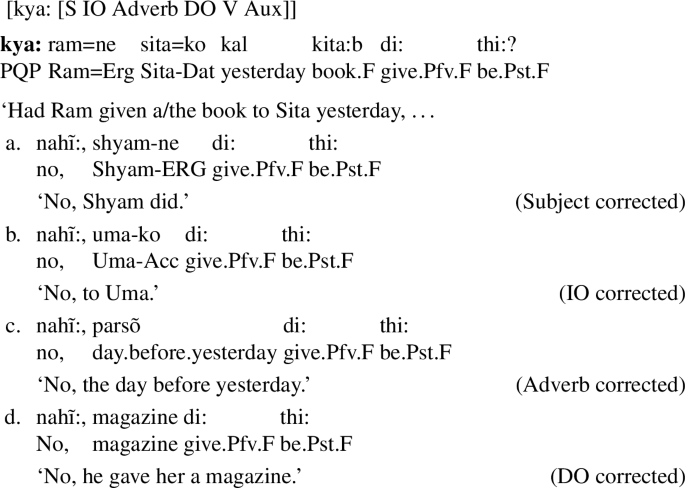

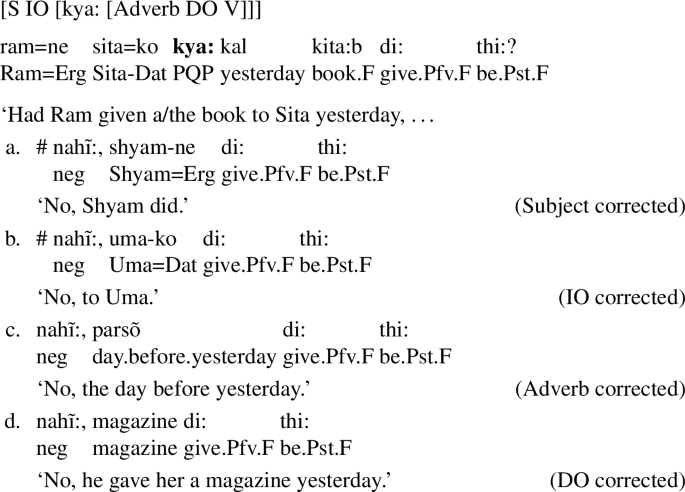

When kya: is clause-initial (or absent), an alternative question can be formed on any element in the clause.

-

(33)

When kya: is not clause-initial, alternative questions can only be formed on phrases that follow but not those that precede it—providing alternatives to them using the above syntactic frame is unacceptable. We illustrate this in (34), where kya: follows the subject and the indirect object but precedes the temporal adverb and the direct object.

-

(34)

The partition contrasts found with gapping are replicated in a paradigm where we consider possible negative responses to a Yes/No question with kya:. With initial kya:, any phrase can be targeted for correction. This is shown in (35).

-

(35)

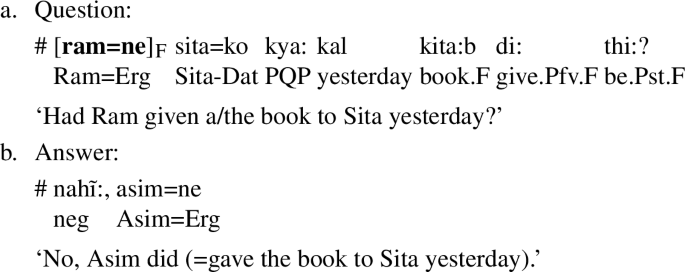

But when kya: is clause-medial, the constituents which precede it cannot be corrected while the post-kya: elements can be.

-

(36)

The pattern we have noted so far holds if the pre-kya: material is read with neutral intonation. But prosody can make a difference. Biezma et al. (2017) note that when the material to the left of kya: is stressed, it is in fact possible to correct/challenge it as in (37).

-

(37)

We agree with the judgement that they report in (37) but we do not think that prosody is sufficient in general to make just any pre-kya: element contrastable. Consider (38).

-

(38)

Prosodic prominence on the subject in (38) does not make it open to challenge. The focus marking on Ram feels unmoored; it does not help in identifying the contrasted element. Footnote 18

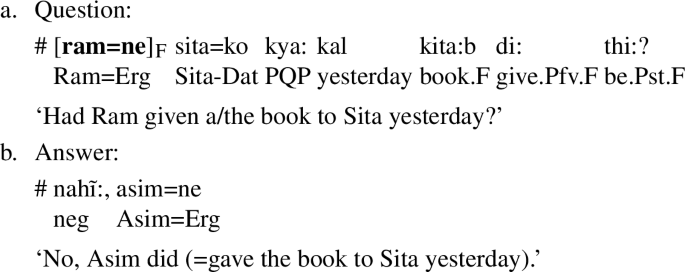

Comparing (37) and (38), we see that there is an adjacency effect for focus on the left: stress on the immediately pre-kya:-XP makes it contrastable but this is not an option for other pre-kya:-XPs. Syed and Dash (2017) claim that there is a similar adjacency effect on the right i.e. only the immediately post-kya: XP can be contrasted. But the data in (33b-d) and (34d), which are robust and widely-accepted (see Biezma et al. 2017), show that adjacency is not required on the right of kya:. To sum up, we claim that all post-kya: material and only the immediately pre-kya: XP can be contrasted. Before we turn to an explanation of this generalization in Sect. 4.3, we briefly explore the theoretical underpinnings of our analysis.

4.2 Deriving the partitions

We have argued that pre-kya: material gets to its surface position via movement. Moreover we have shown that being in a pre-kya: position is associated with certain interpretive restrictions. What motivates these movements? And where do these interpretive restrictions stem from?

It is attractive to connect the answers to both these questions to properties of kya:. Perhaps kya: has syntactic features which look for constituents that bear a matching feature whose semantic reflex is that the constituent is interpreted as backgrounded and hence not being open to challenge. kya: would attract any constituent in its local domain with such a feature and move it to its specifier. This would require us to treat kya: as a head in ForceP. But we believe that this proposal faces a number of challenges.

The first challenge is that what precedes kya: is not necessarily a single constituent. In principle, there can be any number of constituents preceding kya:. This makes a feature based account difficult to maintain. A deeper problem is that the pre-kya: domain is not homogenous. As we have discussed in Sect. 4.1, immediately pre-kya: material can go either way with respect to the challengability diagnostic depending upon the presence of focus.

For these reasons, we are partial to a different implementation, one that does not give kya: all that much to do. In this conception, the movement of phrases in Hindi-Urdu takes place for a variety of reasons—this is a language with scrambling, which we know to be a non-uniform process with a range of motivations. The fronting of phrases that we see with kya: is then not motivated by kya:. What kya: does, however, is reveal that the movement is to a location past ForceP. The interpretive effects are associated with material being in a location past ForceP; they are not encoded in the meaning/lexical entry of kya:.

4.3 Deriving contrastability through focus

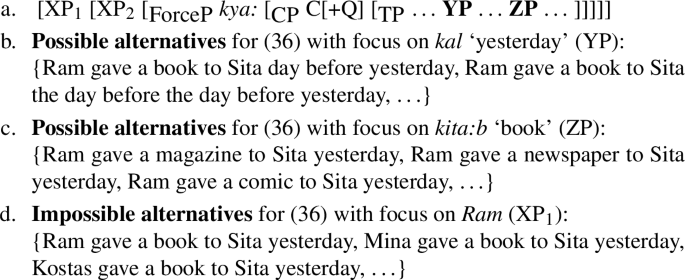

According to our syntactic proposal, kya: is in ForceP and pre-kya: material gets there via movement to a position higher than kya:. We add to our analysis that kya: demarcates the domain that can be focused, which is minimally its c-command domain. This means that in the schema in (39a), YP and ZP can be focused. Deferring discussion of XPfor the moment, we can also say that XPcannot be focused.

-

(39)

Recall that we have taken the ordinary semantic value of polar questions to be a singleton propositional set. The response particle yes is anaphoric to the unique member of this set and asserts it. The response particle no is also anaphoric to this proposition but denies it. What we need to add is a characterization of how permissible corrections arise.

We follow the literature in taking prosodically stressed elements to create a set of alternatives. The focus semantic values shown in (39b) and (39c) draw on alternatives to YP and ZP respectively. A plausible continuation of a no answer draws on such sets. In this we are essentially following the analysis of Turkish polar questions with mı in Atlamaz (2015). In making reference to the focus semantic value of questions, our analysis also shares properties with the proposal in Biezma et al. (2017) which is couched in terms of Questions under Discussion.

Turning now to XP, we note that Hindi-Urdu has several particles that associate to the immediate left: hi: ‘only’ (Bajaj 2016), bhi: ‘also’ (Dayal 1995; Lahiri 1998), nahiĩ ‘not’ (Kumar 2003) among others. Given this broader perspective on the grammar of Hindi-Urdu, we conclude that the paradigm regarding kya: is not unexpected. Given appropriate prosody, the focus semantic value of (37) will include alternatives generated by the immediately pre-kya: XP: {Anu gave Uma a present, Ram gave Uma a present, Vina gave Uma a present, …}.

Allowing the immediately pre-kya: constituent to be open to challenge has interesting implications for another structure that our account makes available. Consider final kya:.

-

(40)

An important difference between the fronting seen here and the cases discussed earlier in (39) is that the fronted constituent is a clause and is therefore able to be have internal prosodic structure (for an overview of theories relating prosody to information structure see Büring (2017); for studies specifically looking at Hindi-Urdu see Féry et al. 2016, Patil et al. 2008, and Genzel and Kügler 2010). With appropriate stress on Uma as in (41), for example, the focus semantic value can shift even though Uma neither follows kya: nor is it left-adjacent.

-

(41)

This focus semantic value allows for corrections and alternatives to Uma.

We have ended up with near synonymy between clause-initial and clause-final kya:, which can both allow alternatives and corrections on any focused constituent in their focus domain. As we will see in the next section, however, the parallelism breaks down when polar kya: interacts with disjunction.

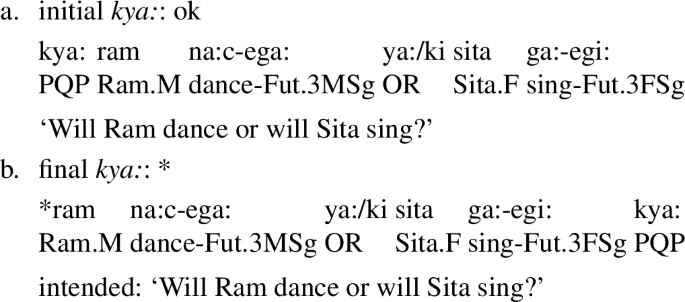

5 Polar kya: and alternative questions

There are two issues that arise when we consider polar kya: in connection with disjunction. One bears on the singleton-set requirement that we have claimed for it, the other is an unexpected restriction against final kya:.

5.1 The singleton set requirement and disjunction

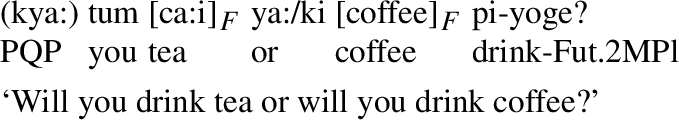

In Sect. 3, we alluded to Bolinger in connection with the difference between polar questions as singleton propositional sets and wh-questions as non-singletons. Let us consider now polar questions with disjunction.Footnote 19

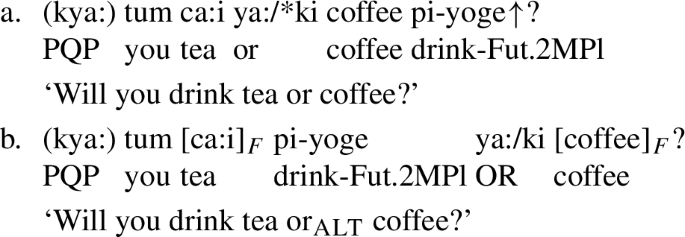

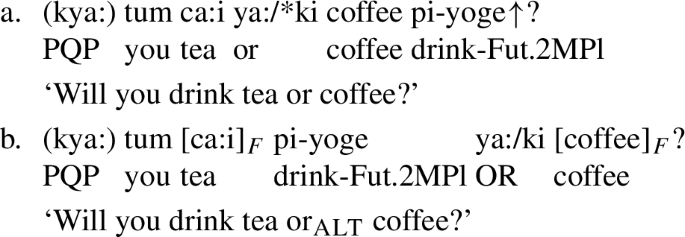

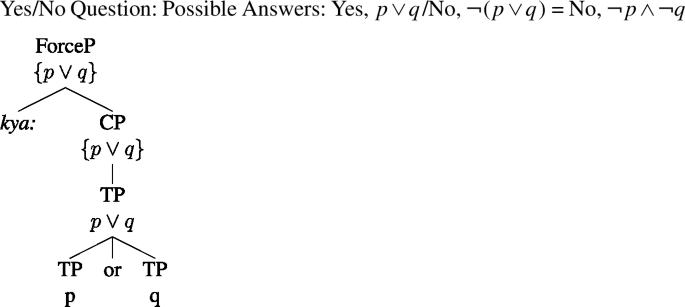

-

(42)

The distinction between Y/N questions and Alternative Questions is not always easy to make but they can be identified on the basis of prosody. In English, Y/N questions have a rising intonation while Alternative Questions have pitch accents on the two alternatives and a final fall. In Hindi too, there is a similar prosodic difference, which we have indicated in (42b) using square brackets. Additionally, Hindi has two lexical items for disjunction, ya: and ki. While ya: can occur in both types of questions, ki can only occur in alternative questions, not in Y/N questions or declarative sentences. We use capital OR to indicate those instances of disjunction where only an alternative reading is available. (42b) shows that kya: is compatible with alternative questions.

This may be a good place to clarify our position on how the prosodic features of alternative questions relate to structure. Bartels (1997) identifies three signature properties, a pitch accent on each disjunct, a prosodic break between the disjuncts, and a final fall. Pruitt and Roelofsen (2013) establish that pitch accents and the prosodic break are more significant than the final fall in identifying alternative questions. From our perspective, the placement of pitch accents and prosodic break is a clause-internal phenomenon that we expect to be always in evidence, in matrix alternative questions as well as alternative questions embedded under rogative or responsive predicates. We have argued that the matrix intonation contour enters the derivation at ForceP, which is also the position at which we see PQP kya: in Hindi-Urdu and embedded inversion in English. We would venture to say that this is also where the final fall that marks the closure of proffered options in alternative questions is located. Since this final fall is indistinguishable from lack of matrix intonation in complements of predicates that do not embed ForceP, the final fall on its own does not help us separate out alternative questions that project up to CP from those that project up to ForceP. Interestingly, Ciardelli et al. (2019) also note cases of alternative questions that have a final rise. Such questions, however, have the behavior of root phenomena. This adds further support to our claim that matrix question intonation is located in ForceP, even in alternative questions.

With respect to answerhood conditions, Alternative Questions typically expect a positive response to exactly one of the proffered alternatives but the choice between them is open. This is taken as evidence that each alternative is included in the question denotation.Footnote 20 If alternative questions denote multi-membered sets, the Hindi-Urdu PQP kya:, as we have defined it, should be incompatible with them. So the fact that they are in fact compatible calls for an explanation. Our solution rests on the view that it is possible to analyze an alternative question with kya: as (44) instead of (43), optionally followed by ellipsis of material in either CP1 or CP2. The account of Hindi-Urdu alternative questions that we develop below is directly inspired by Han and Romero (2004).

-

(43)

-

(44)

For completeness, we add the structure with kya: and disjunction inside a polar question in (45) below but in what follows we will set aside Yes/No interpretations.

-

(45)

In support of our proposal, we note that alternative questions can be conveyed by what looks like an explicit disjunction of two Yes/No questions.Footnote 21 In Hindi-Urdu also, we find that two kya: questions can be disjoined to yield an alternative question.

-

(46)

This disjunction of two kya: questions seems to have the same meaning as the version with just one initial kya:. In fact, as far as we can tell, all the following four variants are acceptable and can be used to convey alternative question readings, of course with the appropriate prosody.

-

(47)

We can interpret all these alternatives with our assumption concerning polar questions and kya: and an assumption about how to interpret disjoined polar questions. In our analysis, p and q individually combine with C[+Q] to form polar questions. By the semantics we have assumed, this means that each polar question denotes a singleton set, {p} and {q} respectively. kya:, if present, only applies to the singleton set corresponding to one of the polar questions and as a result its requirement is met. The crucial component for us is that when we disjoin two Y/N questions, we end up with a multi-membered set {p,q}. (Also see Alonso-Ovalle (2006) and Krifka (2015) among others.Footnote 22)

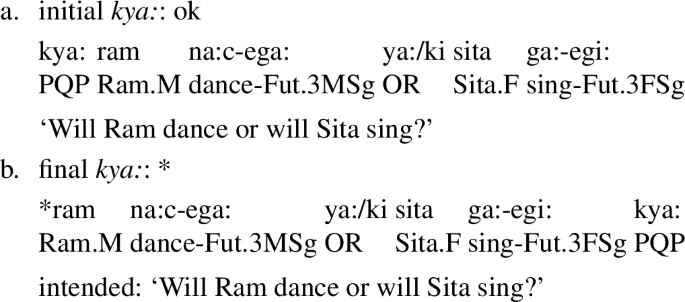

5.2 Final kya: and disjunction

In Sect. 4.3 we saw that clause-initial kya: and clause-final kya: allow the same set of answers. One might therefore expect them to display similar behavior across the board. The two come apart rather spectacularly, however, in the context of disjunction. As we have seen, initial kya: is compatible with a disjunction of finite clauses. But final kya: is not.

-

(48)

Let us remind ourselves of what we take to be the syntactic structure of final kya:. According to our analysis, clause final kya: is derived by movement of the full clause to the left of kya:.

-

(49)

We want to understand the ungrammaticality of final kya: with disjunction of finite clauses, which we can schematically refer to as ‘p or q kya:’. The following parses are in principle available.

-

(50)

Limiting ourselves to alternative questions, we first consider the parse in (50a).

-

(51)

For the needs of kya: to be met in an alternative question, kya: must scope under disjunction but in this structure kya: scopes over it. We have now shown why (50a) is unavailable. What about the structure in (50b) (‘[p or [q kya:]]’)? where kya: is attached to the second disjunct i.e. the disjunction takes scope over ForceP.Footnote 23

-

(52)

This derivation is well-formed and it predicts that the structure should have an alternative question interpretation, which is not in fact available. Why is such an interpretation unavailable? A structure very similar to it is, in fact, what we have argued underlies alternative questions with initial kya:, namely ‘[[kya: p] or q]’.

While we do not have an explanation for the unavailability of the ‘[p or [q kya:]]’ structure, we believe that restrictions on the disjunction of structures with internal topicalization play a crucial role. The significant difference between the unacceptable ‘[p or [q kya:]]’ and the acceptable ‘[[kya: p] or q]’) is that there is clausal topicalization over kya: in the first case. One might imagine that fronting over kya: and disjunction of polar questions would operate independently of each other. This turns out not to be the case. There seem to be stringent restrictions on what combinations of frontings are legitimate in disjoined polar questions. Unlike the well-formed disjunction of two kya:-initial polar questions in (53a), its medial kya: counterpart in (53b) is ungrammatical.

-

(53)

The restriction on ‘p or [q kya:]’ is, from this perspective, part of a larger restriction on the interaction of disjunction and topicalization within the disjuncts.

6 Extensions

We would like to end our discussion by considering two domains in which our account calls for follow-up work. One is specific to polar kya: and involves the extension of our account beyond information-seeking questions. The other is the cross-linguistic application of the distinction we have made betwen PQPs and Q-morphemes.

6.1 Polar kya: and types of polar questions

We have established that polar kya: is restricted to polar questions but we would like to see if there are restrictions within the class of polar questions that may give us further insight into its semantics and pragmatics. We find that polar kya: is perfectly acceptable, for example, in polar questions used as rhetorical and quiz questions.

-

(54)

In the above examples, kya: can occur in all the positions one might expect, of course with appropriate prosody.

We would like to point out that kya: is unacceptable in rhetorical uses of wh-questions. We follow the approach of Rohde (2006) and Caponigro and Sprouse (2007) in taking rhetorical questions to have the same denotation as information seeking questions. In our terms, this amounts to singleton sets as denotations for polar questions and non-singleton sets for wh-questions. The rhetorical use surfaces in contexts where one proposition in the set is known by both participants to be the only true member of the set. Given this approach and the singleton set requirement of kya:, it follows that PQP kya: is not compatible with rhetorical wh questions (see also Dayal 2016: 283-285 for alternative views of rhetorical questions).

kya: is also acceptable in negative and/or biased questions.Footnote 24

-

(55)

In fact, we have so far only been able to definitively identify one type of polar question where polar kya: is not possible. These may be classified as incredulity questions. Footnote 25 Consider the following in a context where the addressee was supposed to have left town and the speaker is surprised to see him:

-

(56)

To be completely upfront about this, it is unclear to us whether (56) is a polar question or an exclamation. It certainly has a prosody very similar to a polar question. If it is a polar question, then the singleton presupposition requirement of kya: would be satisfied and its unacceptability would have to be traced to a different aspect of its pragmatic profile. If, however, (56) is an exclamation and denotes a proposition rather than a set of propositions, the unacceptability of kya: here would follow from the presupposition we have posited. We leave the precise status of (56) for the future, noting only the significance of direct evidence—the speaker directly witnesses the presence of the interlocutor— in regulating the distribution of kya:.

This admittedly brief discussion of the pragmatics of Yes/No questions with polar kya: resonates with, but is not identical to, the more detailed investigations of this topic conducted in a series of papers by Biezma et al. (2017).

6.2 Interrogative question particles crosslinguistically

In the preceding sections we have presented a fairly detailed account of the polar question particle kya: in Hindi-Urdu. In doing so, we have uncovered a complex set of interwoven grammatical effects: the restriction of the polar question particle to polar questions, its sensitivity to quasi-subordination, its appearance in alternative questions, and the relationship between its position in the clause and information structure. One may well wonder if this is simply a quirky phenomenon restricted to the grammar of Hindi-Urdu. In this concluding section we would like to suggest that polar question particles are a robust cross-linguistic phenomenon whose full character is still to be understood. We believe Hindi-Urdu polar kya:, as the first of its kind to be analyzed, can help in this process of discovery.

We take the following to be a necessary criterion for determining whether a particular lexical item in a language is a polar question particle: it should only occur in polar questions. There may well be other significant features associated with polar question particles, such as optionality, information structural effects, and/or selectivity in embedding. As indicated earlier, this rules out Japanese -ka/-no as a polar question particle. We have taken -ka/-no to be Q-morphemes, an overt realization of C[+Q], following a fairly well-established practice in the syntactic and semantic literature. There are other candidates, however, that may qualify as polar question particles. Syed and Dash (2017) have extended the analysis of Hindi-Urdu polar kya: in Bhatt and Dayal (2014) to similar particles in the closely related Indo-Aryan languages, Odia and Bangla. And we have already alluded to the possibility that Mandarin -ma may belong with polar kya: as a PQP. Mandarin nandao, is another candidate for PQP, though it also obligatorily introduces bias (Xu 2017). Other candidates are Turkish -mi (Aygen 2011; Kamali and Büring 2011; Göksel and Kerslake 2004; Atlamaz 2015; Özyıldız 2018), Italian che (Nicoletta Loccioni, Paolo Crisma, Giuseppe Longobardi p.c.) and Slovenian kaj (Adrian Stegovec p.c.). The latter two are homophonous with the interrogative pronoun that means what, similar to the situation in Hindi-Urdu, Bangla and Odia.

We would like to end this discussion with a broader question: why do languages have Polar Question Particles? What would be lost if they did not? Do they add any expressive power? Our account has shown that the Hindi-Urdu kya: does not add any identifiable component of meaning. Its presence correlates with information structure effects but does not seem to cause those effects; rather it just makes them visible. To the extent that PQPs in other languages show a similar profile, we have evidence that natural language lexicalizes items that may not themselves contribute very much but their existence is justified in virtue of the mere fact that they hold up a mirror to other independently available processes.

Notes

We follow a common practice in the South Asian linguistic literature of using Hindi-Urdu to refer to Hindi and Urdu, which for a large number of linguistic phenomena can be considered the same language.

We thank a reviewer for help with the wording.

We will, however, not address the link between polar question particle kya: and thematic kya: in this paper. These two elements seem to be homophonous not just in Hindi-Urdu but in a number of other Indo-Aryan languages as well as in Italian and Slovenian. We have not conducted a wider investigation but it is likely that there is a deeper connection. What such a connection could be though is not clear to us. There is also the fact that the two elements are not fully homophonous—thematic kya: has a pitch accent. This wouldn’t eliminate an analysis where the two have a common core. Another factor to consider is that, as discussed in Syed and Dash (2017), in Bangla and Odia, the polar question particle (ki) cannot be sentence-initial while the homophonous thematic ki can be.

It is possible to have the PQP in a preverbal position, but its acceptability seems to vary based on a number of factors such as the the heaviness of the following verbal complex—see for example the fully acceptable (31c) where the verbal complex consists of a participle and an auxiliary.

The kya: that appears in the Hindi-Urdu scope marking construction patterns with thematic kya: in its distribution and prosodic profile.

This resource was created by Miki Nishioka (Osaka University) and Lago Language Institute (2016–2017). It has around 200 million words. The full reference is: Miki Nishioka (Osaka University) and Lago Language Institute (2016–2017). Corpus Of Spoken Hindi (COSH) and COSH Conc [Software]. Available from http://www.cosh.site. Last accessed 4 January 2020.

An anonymous reviewer notes that (11a) does not form a minimal pair with (11b) and offers us the following example which does form a minimal pair with the rogative.

-

(i)

I found out from what source the reprisals could come.

*I found out from what source could the reprisals come.

The fact that the restriction holds of CPs that are syntactically sisters to a P and not to the embedding verb highlights that selection cannot be a simple lexical matter.

-

(i)

We thank Mingming Liu, Beibei Xu, Jess H.-K. Law and Yi-Hsun Chen for these judgments. See also Song (2018) for discussion related to polar question particles in Mandarin.

The idea that some embedding predicates can take complements with more structure is anticipated in discussions of Spanish. The connection between structural complexity and semantic type-distinctions is articulated most explicitly in Suñer (1993). See Lahiri (2002:147) and Dayal (2016:144–147) for relevant discussion.

We thank Manfred Krifka and Maria Biezma for helpful comments in this connection.

See Sect. 6.1 for non-canonical uses of polar and wh-questions.

We note, though, that there are other contexts, such as unconditionals, discussed by Rawlins (2013), where the presence of complementizers such as whether is insufficient for delivering a plurality of propositions and an explicit (polar) alternative question is needed even in English.

-

(i)

-

(i)

For a recent survey of embedded root phenomena, see Heycock (2017).

More broadly, ForceP[+Q] will realize the intonation that characterizes the question that it embeds. So wh-questions, alternative questions, and rhetorical questions would be associated with different prosodic contours. Put differently, ForceP[+Q] will not always be realized as rising intonation. We thank a reviewer for asking us to clarify the link between our syntax and the prosody of Yes/No questions.

Note that we are not claiming that there is a blanket ban on the movement of weak indefinites in Hindi-Urdu. It is, in fact, possible to move weak indefinites under appropriate conditions (Dayal 2011).

An anonymous reviewer wonders whether (38) improves in the following context: A tells B that Asim and Ram visited Sita yesterday because it was her birthday. A further says that Asim gave Sita a book. B replies ‘what about Ram?’ followed by (38a). What is special about this environment is that the discourse makes available an explicit alternative to Ram and hence one might expect the left-adjacency requirement to be lifted. However, we find that (38a) is still deviant in this context while variants where ‘Ram’ follows or immediately precedes kya: are perfectly natural, especially when supplemented with bhi: ‘also’.

The reader will note that (42a) and (42b) do not form a minimal pair. The minimal pair of (42a), given below in (i), is noted to be ungrammatical in Han and Romero (2004:538–543).

-

(i)

We do not think that (i) is ungrammatical; the source of the problem, we believe, lies in generating the prosody needed for the Alternative Question interpretation with this structure. Some speakers, including one of us, cannot generate the required prosody but accept the Alternative Question reading when presented with questions that have the appropriate prosody.

-

(i)

Questions with disjunction can have a choice reading where the speaker provides a choice of alternatives (e.g. What is your name or your social security number? Either will do). They can also have a cancellation reading where the speaker retracts the first question and substitutes it with a new question (e.g. What is your name? or rather what is your social security number?). We are focusing here on the choice reading of alternative questions, which has been shown to be possible with clause-level disjunction (Hirsch 2017; Ciardelli et al. 2019). See also Groenendijk and Stokhof (1984), Haida and Repp (2013), Krifka (2001), Szabolcsi (1997, 2016). An interesting fact about Hindi-Urdu is that the disjunction operators ya:/ki do not lend themselves to cancellation type readings, for which balki ‘rather’ needs to be used. We set this aside as it does not affect the analysis of the PQP kya: in this paper.

Maribel Romero (p.c.) has directed our attention to examples like Are you or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?. Syntactically these are disjunctions of two polar questions and yet it is natural to respond to them as a Yes/No question i.e. the explicit disjunction of polar questions does not force an Alternative Question interpretation. We believe that for a Yes/No interpretation to be available the two polar questions have to be asking parts of a higher-level question—here this could be Do you have an association with the Communist Party?

Two anonymous reviewers ask how we derive an alternative question, one that presupposes the answer to be only ‘p’ or ‘q’, from a disjunction of two Yes/No questions, each of which allows for a positive and a negative answer (‘p’, ‘¬ p’, ‘q’, ‘¬ q’). On our view, each polar question disjunct denotes only one answer that can either be accepted or denied. When the two combine by set union, we get {p, q} and it is to this set that an answerhood operator applies to yield the unique true answer (see Dayal 2016). Other approaches to building alternative questions out of a disjunction of polar questions have to make analogous moves (see Dayal 2016:261–265 for discussion and further references).

We only show the TP fronting option as fronting the CP is semantically equivalent.

Biezma et al. (2017; slide 32) note that polar questions can be asked even when a speaker expects a negative answer but polar kya: questions cannot. They are considering kya: questions with prosodically focused expressions and we agree. But without such focus, our judgement is that expectations about a negative answer pose no problems to kya:.

Incredulity questions have not been studied in depth and in the case of polar questions they are notoriously hard to separate from echo questions and/or biased declarative questions. The interested reader is directed to the discussion in Dayal (2016: 8, 279–282) and references there.

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis. 2006. Disjunction in alternative semantics. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Atlamaz, Ümit. 2015. A bidimensional semantics for questions. Qualifying Paper, Rutgers University.

Aygen, Gulsat. 2011. Q-particle. Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi 4 (1).

Bajaj, Vandana. 2016. Scaling up exclusive -hii. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Bartels, Christine. 1997. Towards a compositional interpretation of English statement and question intonation. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Bhadra, Diti. 2017. Evidentiality and questions: Bangla at the interfaces. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Veneeta Dayal. 2014. Polar-kyaa: Y/N or Speech Act Operator? Presented at the Workshop on Non-Canonical Questions and Interface Issues, Hegne February 2014. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/6/2964/files/2020/01/polar-kyaa.pdf.

Biezma, María. 2009. Alternative vs polar questions: The cornering effect. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 19, eds. Ed Cormany, Satoshi Ito, and David Lutz, 37–54. Ithaca: Cornell Linguistics Club.

Biezma, María, and Kyle Rawlins. 2012. Responding to alternative and polar questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 35 (5): 361–406.

Biezma, María, Miriam Butt, and Farhat Jabeen. 2017. Interpretations of Urdu/Hindi polar kya. Slides of talk at the Workshop on Non-At-Issue Meaning and Information Structure at the University of Konstanz.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1978. Yes-no questions are not alternative questions. In Questions, ed. Henry Hiz, 87–105. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Büring, Daniel. 2017. Intonation and meaning. Oxford surveys in semantics and pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butt, Miriam, Tina Bögel, and Farhat Jabeen. 2017. Urdu/Hindi questions at the syntax-pragmatics-prosody interface. Slides of talk at Formal Approaches to South Asian Languages (FASAL) 7 at MIT.

Caponigro, Ivano, and Jon Sprouse. 2007. Rhetorical questions as questions. In Sinn und Bedeutung 11, ed. Estela P. Waldmüller, 121–133. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Cheng, Lisa L. S. 1991. On the typology of wh-questions. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Distributed by MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Ciardelli, Ivano, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen. 2019. Inquisitive semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1995. Quantification in correlatives. In Quantification in natural languages, eds. Emmon Bach, Eloise Jelinek, Angelika Kratzer, and Barbara H. Partee. Studies in linguistics and philosophy, 179–205. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2011. Hindi pseudo-incorporation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29 (1): 123–167.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2016. Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2019. The fine structure of the interrogative left periphery. Ms., Yale University.

Dayal, Veneeta, and Jane Grimshaw. 2009. Subordination at the interface: A quasi-subordination hypothesis. Ms., Rutgers University.

Farkas, Donka F., and Kim B. Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27 (1): 81–118.

Farkas, Donka F., and Floris Roelofsen. 2017. Division of labor in the interpretation of declaratives and interrogatives. Journal of Semantics 34 (2): 237–289.

Féry, Caroline, Pramod Pandey, and Gerrit Kentner. 2016. The prosody of focus and givenness in Hindi and Indian English. Studies in Language 40 (2): 302–339.

Gawron, Jean Mark. 2001. Universal concessive conditional and alternative nps in English. In Logical perspectives on language and information, eds. Cleo Condoravdi and Gerard Renardel de Lavalette, 73–105. Stanford: CSLI.

Genzel, Susanne, and Frank Kügler. 2010. The prosodic expression of contrast in Hindi. In Speech prosody 2010. Available at http://www.isle.illinois.edu/speechprosody2010/papers/100143.pdf. Accessed 4 January 2020.

Göksel, Asli, and Celia Kerslake. 2004. Turkish: A comprehensive grammar. London: Routledge.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1984. Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

Gunlogson, Christine. 2003. True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. London: Routledge.

Haida, Andreas, and Sophie Repp. 2013. Disjunction in wh-questions. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 40, eds. Seda Kan, Claire Moore-Cantwell, and Robert Staubs, 259–272. Amherst: GLSA.

Han, Chunghye, and Maribel Romero. 2004. Syntax of whether/q...or questions: Ellipsis combined with movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22 (3): 527–564.

Heycock, Caroline. 2017. Embedded root phenomena. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, vol. 2, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 174–209. Malden: Blackwell.

Hirsch, Aron. 2017. Disjoining questions. Ms., McGill.

Jeong, Sunwoo. 2018. Intonation and sentence type conventions: Two types of rising declaratives. Journal of Semantics 35 (2): 305–356.

Kamali, Beste, and Daniel Büring. 2011. Topics in questions. Handout of a talk presented at the Workshop on the Phonological Marking of Focus and Topic: GLOW 34.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9 (1): 1–40.

Krifka, Manfred. 2013. Response particles as propositional anaphors. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 23, 1–18. Ithaca: Cornell Linguistics Club.

Krifka, Manfred. 2015. Bias in commitment space semantics: Declarative questions, negated questions, and question tags. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 25, 328–345. Ithaca: Cornell Linguistics Club.

Kumar, Rajesh. 2003. The syntax of negation in Hindi. PhD diss, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Lahiri, Utpal. 1998. Focus and negative polarity in Hindi. Natural Language Semantics 6 (1): 57–123.

Lahiri, Utpal. 2002. Questions and answers in embedded contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCloskey, James. 2006. Questions and questioning in a local English. In Crosslinguistic research in syntax and semantics: Negation, tense, and clausal architecture, eds. Raffaella Zanuttini, Héctor Campos, Elena Herburger, and Paul H. Portner, 87–126. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Özyıldız, Deniz. 2018. Move to mi but only if you can. In Papers from Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL) 11, ed. Ryo Masuda. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Patil, Umesh, Gerrit Kentner, Anja Gollrad, Frank Kügler, Caroline Féry, and Shravan Vasisth. 2008. Focus, word order and intonation in Hindi. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 1 (1): 55–72.

Pruitt, Kathryn, and Floris Roelofsen. 2013. The interpretation of prosody in disjunctive questions. Linguistic Inquiry 44 (4): 632–650.

Rawlins, Kyle. 2013. (un)conditionals. Natural Language Semantics 21 (2): 111–178.

Roelofsen, Floris. 2019. Semantic theories of questions. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roelofsen, Floris, and Donka F. Farkas. 2015. Polarity particle responses as a window onto the interpretation of questions and assertions. Language 91 (2): 359–414.

Rohde, Hannah. 2006. Rhetorical questions as redundant interrogatives. In San Diego linguistics papers 2, 134–168. San Diego: Department of Linguistics, UCSD.

Song, Yixiao. 2018. A comparative study of German and Chinese alternative questions. Poster presented at the MiQ Workshop at the University of Konstanz.

Suñer, Margarita. 1993. About indirect questions and semi-questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 16 (1): 45–77.

Syed, Saurov, and Bhamati Dash. 2017. A unified account of the yes/no particle in Hindi, Bangla and Odia. In Generative Linguistics in the Old World (GLOW) in Asia 11, volume 1, ed. Michael Yoshitaka Erlewine, Vol. 84. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1997. Quantifiers in pair-list readings. In Ways of scope taking, ed. Anna Szabolcsi, 311–349. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2016. Direct vs. indirect disjunction of wh-complements, as diagnosed by subordinating complementizers. Ms., NYU.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2019. The semantics of question-embedding predicates. Language and Linguistics Compass 13(1): 1–17.

van Rooij, Robert, and Marie Šafářová. 2003. On polar questions. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 13, eds. Robert Young and Yuping Zhou, 292–309. Ithaca: Cornell Linguistics Club.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1996. Against lf pied-piping. Natural Language Semantics 4 (1): 57–110.

Westera, Matthijs. 2018. Rising declaratives of the Quality-suspending kind. Glossa 3(1): 121. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.415.

Xu, Bebei. 2012. Nandao questions as a special kind of rhetorical question. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 22, ed. Anca Chereches, 488–507. Ithaca: Cornell Linguistics Club.

Xu, Bebei. 2017. Question bias and biased question words in Mandarin, German and Bangla. PhD diss., Rutgers University, New Brunswick.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not exist if Miriam Butt had not invited both of us and then told us to give a joint talk at the workshop on non-canonical questions in Hegne in February 2014. That got us working on this topic. We are very grateful to audiences at that workshop and at LISSIM 8, the GIAN lecture series at the University of Mumbai, the 2nd CreteLing, UMass Amherst, UCSD, Johns Hopkins, UConn, MIT, UCLA, seminars at Rutgers between 2014 and 2018, and the IATL conference in Beer Sheva. Miriam Butt, Tina Bögel, Maria Biezma, Farhat Jabeen, Gennaro Chierchia, Anoop Mahajan, Dominique Sportiche, Hilda Koopman, Roger Schwarzschild, Aron Hirsch, Irene Heim and Adrian Stegovec helped us refine our initial understanding of this phenomenon. Finally, we would like to thank our three anonymous reviewers for incredibly detailed and helpful reviews and our editor Hedde Zeijlstra who expertly shepherded us through the process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatt, R., Dayal, V. Polar question particles: Hindi-Urdu kya:. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 1115–1144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09464-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09464-0