Abstract

Spanish comparatives have two morphemes that can introduce the standard of comparison: the complementizer que (‘that’) and the preposition de (‘of’/‘from’). This paper defends the idea that comparatives introduced by the standard morpheme de are phrasal comparatives that always express overt comparison to a degree. I show how this analysis derives the key properties of de comparatives, including the fact that they are acceptable in a much more restricted set of environments than their que counterparts. The latter are argued to involve additional covert structure, which accounts for their general flexibility. If correct, these data point to a previously unnoticed locus of cross-linguistic variation in comparative formation, whereby a standard morpheme is subject to semantic as well as syntactic well-formedness conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

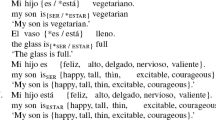

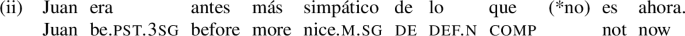

This paper investigates two comparative constructions in Spanish characterized by the use of different standard morphemes, as illustrated in (1).

Spanish is not special in this respect. Especially in languages that lack a construction-specific morphological marker for comparatives (e.g. the English than), we find that the standard morpheme may have different kinds of exponents. By far the most common alternative to having a dedicated comparative marker is to employ a complementizer, which in Romance corresponds to que/che, as shown in (1a). It is also common to find languages that have a second standard morpheme, formed by some other expression, usually a preposition with a directional meaning (Stassen 1985), like the preposition de in (1b), but sometimes also a genitive marker, as in Greek (Merchant 2009).

The precise role of these different morphemes is contentious, the debates centering on whether they are semantically vacuous elements that surface solely for purposes of syntactic well-formedness, and whether they introduce their own further, semantically meaningful, selectional restrictions. For example, in languages like Greek (Merchant 2009), Russian (Pancheva 2006) and Hungarian (Wunderlich 2001), to name a few, it has been argued that the choice of the standard morpheme depends on the phrasal (i.e. nominal) or clausal nature of the standard.

In spite of the fact that comparative constructions in Spanish have received a great deal of attention in the literature, the difference between comparatives using the two different standard morphemes has yet to receive a proper analysis. Historically, the efforts to account for the restricted distribution of de comparatives have focused either on (i) syntactic considerations pertaining to the size of the standard, or on (ii) intuitions about the semantic differences of de comparatives when compared to their que counterparts.Footnote 1 In the syntactic camp, it has been variously argued that de can only take full clauses as standards (Plann 1984), reduced clauses (Price 1990), small clauses (Gallego 2013) or DPs (Brucart 2003). On the other hand, the semantic factors that are said to play a role in the limited distribution of de comparatives are far more consistent in the literature. The guiding intuition behind this restriction is that complements of de comparatives must refer to a “quantity,” an “extent,” a “degree” or an “amount,” and it can be traced as far back as Bello (1847). For concreteness, let us call this requirement the Quantity Requirement.

As we will see below, this descriptive characterization does some justice to the distributional properties of de comparatives, but answers to the question of what exactly constitutes a “quantity denoting” expression have never gone beyond this intuitive notion. Thus, while the consensus on the Quantity Requirement seems to be pointing in the right direction, its loose and vague nature calls for a more precise characterization.

The two lines of analyses, syntactically and semantically centered, reflect the tension between the two aspects of de comparatives that seem to drive the choice of the standard morpheme. In this respect, the literature thus far has been lacking in two ways: a tendency to focus on one or other of the two aspects—syntactic vs semantic—of de comparatives, and within each camp, a lack of consistency and precision about what the relevant factors driving the distribution of de are. This paper contributes to this body of literature by (i) arguing that both syntactic and semantic factors must be taken into account (and in turn, both camps in the previous literature were in fact right, albeit only partially), and (ii) formally clarifying what those conditions are. More specifically, I propose two different constraints, one syntactic and one semantic, that de comparatives are subject to. From a semantic point of view, the presence of de overtly signals that the comparison is with a degree, rather than an individual. From a syntactic perspective, I argue that de comparatives are always phrasal, that is, the complement of de must always combine with nominals, either DPs or Numeral/Measure Phrases. This is summarized in (3):

Each of the two conditions in (3) is necessary but on its own insufficient to account for the limited distribution and range of interpretations observed with de comparatives.

The task now is twofold: we must show that standards of comparison are syntactically nominal, and that semantically de comparatives can only combine with d-denoting objects. The syntactic distribution of de comparatives and their inability to host multiple remnants speaks in favor of their phrasal nature. Semantically, I show that de comparatives are grammatical only with DPs that can denote definite descriptions of degrees. Furthermore, they are shown to be scopally inert, providing support for a direct analysis where no additional DegP movement is required. The resulting analysis is fully compositional, and so de comparatives are not taken to be an instance of “contextual” comparison (cf. Beck et al. 2004; Kennedy 2009). In contrast to de, comparatives with the standard que realize the default strategy for forming comparatives in Spanish (either clausal or phrasal), where the composition involves movement of the comparative marker -er and degree abstraction. As a consequence, we will find that even in environments where both de and que standard morphemes are possible, the resulting semantic interpretations vary in predictable ways.

The paper is divided in two main parts: the first half provides the main body of empirical facts that the formal analysis presented in the second half aims at accounting for. The first part starts off in Sect. 2 by describing the semantic properties of de comparatives and establishing a distinction between comparison to a degree and comparison to an individual. In Sect. 3, I present a series of arguments showing that de comparatives must always be phrasal (i.e. the standard must always be nominal), and Sect. 4 shows why neither of the conditions in (3) is reducible to the other. Thus, the main goal of the first part is to refine and precisify many of the observations already present in the literature. The second part of the paper focuses on providing a unified formal account for all instances of de comparatives discussed so far. Section 5 presents a baseline theory based on degree semantics, providing a standard analysis of que comparatives against which simpler cases of de comparatives are compared; the analysis is then extended to more complex cases in Sect. 6. Finally, Sect. 7 discusses the cross-linguistic significance of the analysis provided, as well as some odd-ends and open questions.

Before we continue, it is useful to establish some terminology. First, the constitutive parts of comparative constructions will be referred to as follows:

Second, the literature commonly distinguishes between two types of comparative constructions, depending on the syntactic size of the standards of comparison: “clausal” and “phrasal” comparatives. While clausal comparatives typically involve CP standards, either full or reduced clauses, in phrasal comparatives the standard of comparison is invariably a nominal projection, either a full DP or a Measure/Degree Phrase. I adhere to this conventional terminology here, and thus “phrasal comparatives” should be taken to be those whose standard is nominal, and not just any phrase.

2 Semantic properties of de comparatives

This section showcases the main semantic properties of de comparatives by directly comparing them to the more garden variety comparatives with que. It introduces the distinction between comparison to a degree and comparison to an individual, and shows that de comparatives are only capable of expressing instances of the former.

2.1 Reference to “simplex” degrees

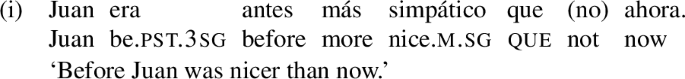

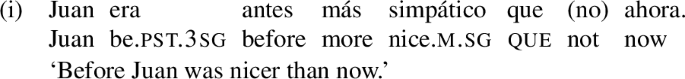

Demonstratives in Spanish provide a good testing ground to highlight the semantic differences between de/que comparatives. The neuter demonstrative eso (“that”) can easily refer to either an individual or a degree. (In the examples below, this difference is signaled by using the e subscript for individuals and a d subscript for degrees.) This is not unlike the English demonstrative that: in addition to its ability to point to individual entities, that can also point to degrees. For instance, if you told me that your paper is fifty pages long, I could reply that thatdis too long, where thatd refers to the length of the paper and not to the paper itself. Comparatives with de are compatible with demonstratives that refer to degrees, like thatd in English.

However, if the context is such that the demonstrative is referring to an individual rather than a degree, the standard que is required.

The difference between using one or other standard marker amounts to what the object of the comparison itself is: de comparatives are cases of comparison to a degree,Footnote 2 whereas que comparatives are cases of comparison to an individual. If what I mean is that the railing is taller than some object that has been mentioned/referred to before, I cannot use de, (6). Instead, if the railing is taller than some height already salient in the context, only a de comparative is able to express such comparison, as illustrated by (5). As a consequence, the potentially ambiguous referent of the pronominal form eso must resolve to esod with de, and to esoe with que. It must be noted that some speakers seem to allow esod with que standards, i.e. they are more willing to accept (5) with que as grammatical. It is difficult to determine the status of these idiolects because there appears to be some within-speaker inconsistencies, and so I defer a better discussion of these cases until a future occasion (see also fn. 7). In what follows I will only consider that que is limited to esoe.Footnote 3

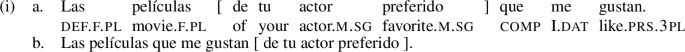

We can corroborate these facts by looking into the distinction between the neuter and non-neuter forms of the demonstrative. When the demonstrative refers to a degree it must carry neuter ϕ-features. In turn, non-neuter demonstratives can only refer to individual entities. The consequence is that demonstratives with non-neuter ϕ-morphology are not allowed with de comparatives, as illustrated below.Footnote 4

This limitation extends to all instances of de comparatives: with de, only the neuter form of the pronominal is allowed. The standard in (8a) below can only refer to the length of the book I read. In contrast, que comparatives are grammatical with non-neuter demonstratives, but then the target of the comparison can only be the book I read, instead of its length, (8b).

A similar case can be made by looking into measure nouns. Measure nouns do not usually have individual referents—i.e. we do not often speak of one particular meter or a certain kilo. Instead, they denote measurements or, in our lingo, degrees, and thus they provide a natural way of establishing a comparison to a degree. In accordance with the restriction to neuter demonstratives, we observe that de comparatives are only compatible with measure nouns.

Of course, ordinary DPs like a car and Boston may be used to allude to some associated degree when they constitute instances of comparison to individuals. That is, there is nothing wrong with expressing a comparison between the weights of stones and cars, or the distance between any two cities. Those are instances of comparison to an individual, however, and so the choice of the standard morpheme is reverted.

Altogether, these examples—and their contrast with the que variants—point out the limitation of de to appear in contexts where a degree is referenced to, in line with the semantic restriction introduced in (3) above.

2.2 Reference to “complex” degrees

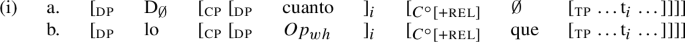

The examples we have seen so far involve a seemingly simple DP in the standard of comparison that must be interpreted relative to some default or contextually determined degree. But there are other means by which degrees can be referenced. In Spanish, the most commonly used degree expressions that participate in de comparatives involve constructions where the complement of de is a headless relative clause. These can be either in the form of a quantity free relative or a null NP relative clause—a term that for the moment must be understood in descriptive theory-neutral sense.Footnote 5

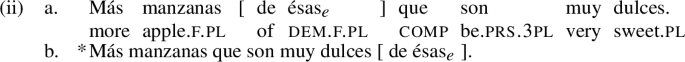

In quantity free relatives, the relative clause is headed by the relative pronoun cuanto (“how much”), which is the specific relative pronoun for quantity in Spanish. Semantically, cuanto-phrases and its variants have been extensively argued to denote a definite degree (see Gutiérrez-Rexach 2014 for a summary of arguments). Following the earlier patterns, only the standard morpheme de is grammatical when the standard of comparison is a free relative headed by cuanto (Plann 1984; Real Academia de la Lengua Española 2010).

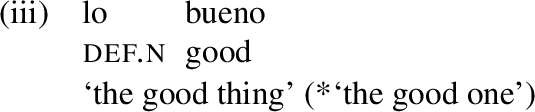

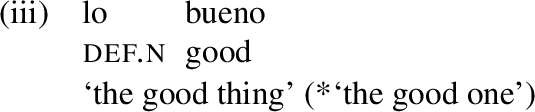

In the second case, the relative clause is characterized by a definite determiner combining directly with the complementizer que that introduces the subordinate clause. The distinguishing property of these null NP relative clauses is that the noun that the subordinate clause modifies is missing, very much like in free relatives. These [D que] clusters have been argued to be syntactically akin to relative pronouns like cuanto (e.g. Brucart 1992; Real Academia de la Lengua Española 2010) and semantically capable of denoting definite degrees (Gutiérrez-Rexach 1999).

Examples (11) and (12) above are semantically equivalent, the two constitute cases of comparison to a degree, where the only licit interpretation amounts to a comparison of cardinalities. The corresponding variants with que are degraded in the two cases.

Just like we saw with demonstrative pronouns, we can use differences between neuter and non-neuter forms to track the referent of the relative clause construction. The difference is visible only with comparatives that have non-nominal restrictors. For instance, attributive comparatives with a gradable predicate in the restrictor position admit relative clause constructions bearing both neuter and non-neuter morphology. But, as we saw with demonstratives, the difference between neuter and non-neuter forms tracks the type of referent of the full relative clause construction. Below we have a case of non-neuter ϕ-morphology on the definite article, rendering the variant with the standard morpheme de ungrammatical.

Informally, (13) states that the trouts that Pedro fished are bigger than some other individual x, where x corresponds to the trouts that I fished. Rather than comparing sizes directly, (13) compares two sets of individuals along the dimension of size. Once again, this is a case of a comparison to an individual. As expected, then, the relevant comparison to a degree interpretation can be achieved by using neuter morphology, which in turns results in the opposite choice of standard morpheme:

Now in (14) the comparison happens between sizes alone: the size of the trouts that she fished is greater than the some size corresponding to the upper bound of what is allowed. Thus, the distribution of the different morphological forms and the interpretations of the two variants follows the same pattern we observed with demonstratives. (The interpretations are the same if we substitute the relative clause constructions in (13) and (14) for a demonstrative with matching ϕ-morphology.)

2.3 Section summary

From a semantic point of view, the difference between the two standard morphemes seems to boil down to the object of the comparison itself: unlike que, de must compare degrees directly. Thus, de uniformly expresses comparison to a degree, and que must be recruited to express comparison to an individual. More formally, I take these facts as indication that the complement of the standard morpheme de invariably combines with a degree. When the restriction of the comparative marker is adjectival, the comparison is between different degrees of the same entity along the dimension determined by the adjective. When the restrictor is nominal, the standard morpheme de indicates that the comparison is between two cardinalities of two sets of objects. Thus, the Quantity Requirement, here re-characterized as a constraint on these comparatives as expressing comparisons to a degree seems to give us non-trivial empirical coverage.

Those familiar with the semantic literature on comparatives will, at this point, wonder whether this conclusion leads us to problematic predictions. After all, on most theories of comparatives standard phrases are usually ascribed a degree type, either 〈d,t〉 or d (see Morzycki 2016 for an overview), seemingly washing out the intuitive differences between comparison to degrees vs. individuals. Thus, given the semantic constraint in (3a) and the intuitions behind the Quantity Requirement, it would seem that de comparatives should be the norm, not the exception. Then, why and how are de comparatives different from other comparative constructions?

As advanced earlier, the answer lies in the fact that (3a) only covers half of the picture, as de comparatives are also syntactically restricted. In particular, the standard of comparison must always be nominal. This effectively limits the ability of de-standards to two kinds of objects: (i) nominal phrases that are born as degree denoting expressions, like Number Phrases, Measure Phrases, and demonstratives referring to degrees; and (ii) degrees derived via movement operations, as in the case of some relative clause constructions. The goal of the next section is to show that these expectations correspond to the empirical landscape of de comparatives in Spanish.

3 Syntactic restrictions on de comparatives

As before, this section contrasts the properties of de comparatives with those of que variants. It shows that, while que comparatives show a greater degree of flexibility with respect to the syntactic size of their standard, de comparatives can only be phrasal (i.e. nominal).

From a syntactic point of view, the distribution of de comparatives is more restricted than its que counterparts. As a starting point, (15) illustrates the long-standing observation that de comparatives are incompatible with run-of-the-mill (full) clausal comparatives:

Less conspicuous is the question of whether de comparatives are cases of reduced clausal comparatives or phrasal comparatives. Phrasal comparatives are comparative constructions where the complement of the standard morpheme is a simple nominal phrase, a DP (e.g. Heim 1985; Kennedy 1997). Reduced clausal comparatives are derived from full clausal comparatives by a process of reduction/elision, as in (16) (Bresnan 1973; Hankamer 1973; Pinkham 1982, a.o). As a consequence, they superficially resemble phrasal comparatives.

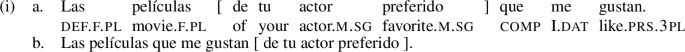

A reliable method of uncovering true phrasal comparatives is by looking into the syntactic size of the standard, for instance by checking whether it admits more than one syntactic remnant. All else equal, true phrasal (non-reduced) comparatives do not admit syntactic remnants in the standard of comparison other than the nominal selected by the standard morpheme, since there is no reduced clause in which the offending remnant could have originated. This is illustrated below with Greek and Hindi, both languages which have been shown to possess phrasal comparatives with a dedicated standard morpheme.

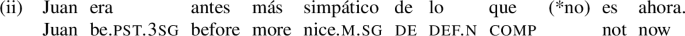

Turning now to Spanish comparatives, we observe that de comparatives, unlike their que counterparts, do not allow multiple remnants. The following example sets up a context where both que and de variants are possible and contrasts their availability with single and multiple remnants.

In (19) the comparison is relative to an individual, in this case relative to the robot that jumped yesterday. This is only possible with que. On the other hand, (20) compares directly the lengths of the two jumps. Crucially, when the standard of comparison includes more than one remnant, only reference to an individual is possible (i.e. with esoe), and only the que variant is allowed.

Thus, the fact that de comparatives cannot host more than one remnant suggests that they only take phrasal (nominal) standards.Footnote 6

A further argument for the phrasal status of de comparatives comes from a ban on reduction. A logical consequence of the full/reduced clausal analysis is that material within the standard of comparison can always be elided (in fact, sometimes it must; Reglero 2007). Important for us is the fact that eliding the verb is always a possibility for clausal que comparatives.

The same is not possible with de comparatives. As is well-known, it is not possible to elide the verb of a relative clause construction in Spanish.

Accordingly, the verb cannot be elided in comparatives with de, suggesting that it must be a DP—a conclusion in line with current assumptions about the constituency of free relatives as well, which are generally argued to be nominal; see Jacobson (1995), Caponigro (2002), Ojea (2013), a.o.

4 Taking stock: Two conditions for de comparatives

Recall our key generalization: the distribution and range of interpretations of de comparatives are the result of the interplay between two independent restrictions:

From (3a) it follows that de comparatives must always express a comparison to a degree, and the fact that they are limited to DPs of various sorts is accounted for by (3b). There are a number of additional facts that fall out of the joint action of the two constraints that speak against the possibility of reducing the limited distribution of de comparatives to one or the other.

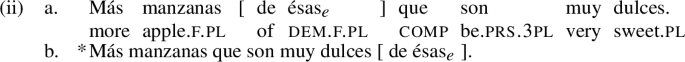

For the sake of the argument, suppose that de comparatives were not limited by (3a), that is, that their only restriction was a syntactic necessity to take nominal standards. This syntacto-centric account would lead us to make two wrong predictions. Consider first subset comparatives. These are comparative constructions where the restrictor and the standard are in a set membership relation. For instance, in (25) below, El Quijote is a member of the sets of all books (Grant 2013).

Aparicio (2014) shows that subset comparatives are phrasal. Evidence comes from their inability to host multiple remnants (26) and their incompatibility with bona fide phrasal standard morphemes in languages like Greek (27).

In addition, the standard of comparison in subset comparatives must always denote an individual (or a kind; see Grant 2013). Evidence for this requirement comes from the fact that elements denoting outside the domain of individuals cannot form subset comparatives, despite standing in similar entailment (set to subset) relationships:

Now, if the only restriction of Spanish de comparatives was syntactic, de should be grammatical in subset comparatives. This is not the case: subset comparatives are only grammatical with the que standard morpheme.

In addition to subset comparatives, there are a number of other constructions that have been argued in the literature to correspond to “true” phrasal comparatives in Spanish, and not simply reduced clauses. Brucart (2003: 39), for instance, mentions cases of DP-internal comparison as paradigmatic of phrasal comparatives (see also Gutiérrez Ordóñez 1994a and Sáez and Sánchez López 2013). These are comparatives where the object of the comparison is always DP-internal, although the comparison itself may target constituents of different categories, such as APs, PPs, etc. None of these comparative constructions can be formed with de.

Sáez del Álamo (1999) provides a final testing case. He argues that nominal comparative phrases in subject position in Spanish must always be phrasal. The main reason is that no licit elision process could have derived the corresponding surface order. However, these are environments that do not admit the standard de.

The conclusion is clear: it is not possible to reduce the overall behavior of de comparatives to their syntactic idiosyncratic properties. Because they are syntactically well-formed, the offending variants with de in (29) through (31) must be unacceptable because of some other reason. In my view, this is good evidence that we need the semantic restriction expressed in clause (3a). Notice that there is also a secondary corollary that follows these data: unlike de comparatives, que comparatives are much freer in their distribution, as they may take full clauses and a variety of different phrases as their standards, such as DPs, APs and PPs.Footnote 7

We can ask ourselves the same question in the opposite direction. Suppose that de comparatives were not limited by any syntactic considerations, and all they require is a certain semantic constraint on their standards. It is easy to show that the Quantity Requirement, as phrased in (2), is insufficient, in part because it is too vague and general about what should count as quantity-denoting. For example, there is agreement that expressions like “many athletes” are quantity-denoting, but that is not enough to grant their compatibility with de.

The more concrete proposal in (3a) argues that de comparatives only allow comparison to a degree. The cases we have explored so far have been limited to (i) simplex denoting-expressions like Number/Measure Phrases and degree-referring demonstratives and (ii) degree and quantity free relatives. To show that this semantic restriction is insufficient, however, we must show that a degree-denoting expression (i.e. the semantic criterion) that is nevertheless not expressed as a DP (the syntactic criterion) is ill-formed with de.Footnote 8 I suggest that subcomparatives with gradable predicates as standards provide such a case.

The sentence in (33) constitutes an instance of comparison to a degree, whereby two distinct degrees pertaining to the same individual are compared along the dimension of length. It cannot be a case of comparison to an individual because there are no two individuals being compared. There is also little doubt that the gradable predicate constitutes a degree expression.Footnote 9 The ill-formedness of (33) must therefore be attributed to extra-semantic factors. As defended above, the syntactic requirement that the standard be nominal is not met in subcomparatives like (33). This is easily demonstrable by showing that the standard can accept multiple remnants, effectively establishing a comparison to individuals, which, as shown in Sect. 3, is never possible with truly nominal standards.

What these examples show is that establishing a comparison to a degree is a necessary but not sufficient condition to form de comparatives in Spanish. The main conclusion so far is that, taken independently, none of the two requirements in (3) suffices to account for the distribution and range of interpretations observed in de comparatives.

5 Formal implementation

In this section I present a formal analysis of de comparatives that accounts for the body of data discussed above. Before doing so, I lay out my assumptions about the syntax and semantics of comparatives in Spanish using que comparatives as an illustrative baseline.

5.1 Background: Setting a baseline

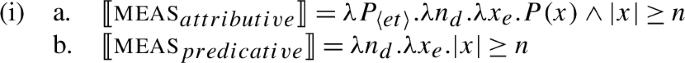

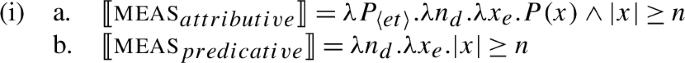

The analysis appeals to degree-semantics. Degrees are ways of representing measurements along a scale, that is, they are measures of some property, like being d-tall, d-big, d-many, etc. (Seuren 1978; Cresswell 1976; von Stechow 1984; Heim 1985; Bierwisch 1989, a.o.). Scales are sets whose elements are totally ordered according to some ordering relation, and degrees can be regarded as primitive members of these sets (Cresswell 1976; Bierwisch 1989). Thus, not just any set of degrees can conform a scale: every degree in it must be ordered with respect to each other. As a consequence, degrees cannot be compared across scales—i.e. we cannot compare degrees of size to degrees of weight; this is the problem of incommensurability. In this view, gradable predicates are regarded as ways of relating individuals and degrees (Bartsch and Vennemann 1972; Cresswell 1976; Kennedy 1999); because nothing is just “big,” it must be big to some degree. I assume then that gradable predicates conform to the following general schema.

The degree argument in (35) can be provided by either degree expressions like 6’ and \(20\,^{\circ}\)C, demonstratives like thatd and can even be contextually supplied. What is important for us is that any measure can be represented by appealing to degrees, regardless of whether there is a natural language unit to directly express such degree. Thus, quantities, amounts, sizes, are all expressible via degrees, as is the extent to which somebody is bored, interesting, and so on.

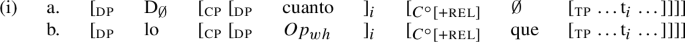

Turning now to Spanish, we have seen that que comparatives have a much wider distribution than comparatives with de. Using que is the only strategy when it comes to construct clausal comparatives in Spanish, either full or reduced, which constitute the vast majority of constructions that are available with the standard morpheme que (Bolinger 1950, 1953 a.o.). For the syntax and semantics of Spanish clausal que comparatives, I assume the standard framework pioneered by Bresnan (1973) and von Stechow (1984) as spelled-out by Heim (2001) and others. In Spanish que comparatives, standards of comparison have an underlying clausal structure and are generated as complements of the comparative marker más, which constitutes the head of its own projection, a Degree Phrase (DegP). The syntactic geometry of the comparative clause is the one depicted in (36).Footnote 10

Semantically, DegP is a generalized quantifier over degrees (type 〈dt,t〉), which undergoes Quantifier Raising to resolve a type mismatch, and does so by leaving a trace of type d. The comparative marker itself is a generalized quantifier-determiner over degrees (of type 〈dt,〈dt,t〉〉), analogous to generalized quantifier-determiners over individuals. The assumed lexical entry is provided in (37a), together with the denotation of the maximality operator max in (37b) (Heim 2001).

Finally, I assume the movement of a silent operator Op (analogous to a silent wh-pronoun) in the standard of comparison (Chomsky 1977). This movement originates out of the degree argument position of the gradable adjective and yields a set of degrees (type 〈dt〉). This property of degrees serves as the restrictor of the comparative marker más. For the sake of concreteness, consider example (38), with the relevant LF configuration illustrated in (39) below.Footnote 11

What is important for us is that the subordinate CP is of a type that allows it to be taken as the first argument of the comparative marker más after the movement of the wh-operator. This type of analysis allows us to do so.

5.2 Standards as definite descriptions of degrees

If the characterization of de comparatives in Sect. 3 is correct and the arguments go through, there are good reasons to believe that these constitute an instance of phrasal comparison (against Plann 1984 but with Sáez del Álamo 1999 and Brucart 2003). This accounts for the syntactic restriction on de comparatives, in (3b). In what follows, I present a concrete semantic implementation of the semantic condition in (3a) that allows for a unified analysis of de comparatives discussed in Sect. 2 through Sect. 4. I begin by first presenting the general analysis with simpler cases, where de comparatives take standards that are minimal, and then I extend it to the more complex cases with relative clause constructions.

The semantic literature contains a handful of suggestions about what the denotation of the comparative marker should be. Part of this discussion is concerned with the type of the first argument of the comparative marker, as well as the order in which the operator takes its arguments, its currying. Some authors (e.g. Heim 1985) argue that the first argument is an individual (type e), while others (e.g. von Stechow 1984) defend that it must be a property of degrees (type 〈dt〉). It is also possible, however, to find comparative operators that combine with an expression that denotes a degree, of type d:

Here the pronominal thatd refers to 6’. The semantic truth conditions of such sentences can be represented as height(Pedro) > 6’, i.e. true iff the height of Pedro is greater than some relevant height in the discourse (in this case 6’). As emphasized by Beck et al. (2012), this type of comparison is quite common across languages. In fact, examples like (40) are no different than cases where the standard of comparison is not given by a than phrase (see Kennedy 2009). In (41), the standard of comparison usually expressed by the than phrase is left unspoken and yet the interpretation of the sentence is equivalent to its counterpart with an overt standard phrase than thatd.

The similarity between the two constructions in (40) and (41) suggests a syntactic and semantic isomorphism between them, relating to their ability to directly pick a degree, either explicitly or implicitly. In order to achieve the right truth-conditions for these and all other degree comparatives with de in Spanish, I propose the lexical entry for the comparative marker in (42) (see Pinkal 1989; Beck et al. 2012, a.o.).

The lexical entry in (42) directly takes a gradable predicate (an adjective in the case of (40)) and then it relates a degree and an individual along the dimension established by said gradable predicate. This is the lexical entry suggested by Pinkal (1989) for certain cases of comparative constructions in English and German, and by Beck et al. (2004) for yori comparatives in Japanese. Notice also that prima facie (42) does not require any sort of covert movement to get to the right semantics, allowing us to assume a simple syntactic structure for (40) like in (43).

The order in which elements combine at LF matches their arrangement in the surface syntactic structure. With these ingredients in place, the semantic computation for sentences like (40) proceeds along the following lines:

5.3 Assessment

The main syntactic and semantic properties of de comparatives mentioned earlier in (3) follow directly from this analysis. From a syntactic standpoint, the inability of de comparatives to host multiple remnants follows naturally from its phrasal nature: de comparatives must take nominal complements, and so there is no space for multiple remnants. It also follows that comparatives with esoe, which do allow multiple remnants, require the que standard morpheme.

From a syntactic standpoint, the analysis proposes a categorical distinction between de comparatives, whose standard is invariably a DP, and que comparatives, whose standard is a clause, a CP.Footnote 12 Given the two geometries assumed for the que and de comparatives, and that CPs, unlike certain PPs, are easier to extrapose, we would expect that extraposing the standard of comparison is easier in the case of que comparatives as compared to their de counterparts. This is precisely what we find: extraposing the de-phrase and allowing material to intervene between más and the restrictor render (45a) below ungrammatical.Footnote 13

Instead, these configurations are not problematic for que cases taking an individual denoting standard, given the greater facility to extrapose CPs across the board.

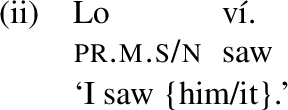

From a semantic standpoint, the analysis directly captures the difference between comparison to a degree and comparison to an individual. If what I intend to convey is, for instance, that Pedro is taller than some height I explicitly mentioned before, then (5)/(40) must be used in a comparison to a degree construal. Instead, if Pedro is taller than some object that I am pointing at, only a sentence like (6) above can be used to express such comparison (see also the contrasts in (8a) vs. (8b), (9) and (13) vs. (14)).

We have already calculated the truth-conditions of (5)/(40): the neuter demonstrative pronoun eso can refer either to an individual, esoe or to a degree, esod. The presence of de signals that a certain comparative marker más must be used, más\(_{\textsc{degree}}\), which can only take degrees as its second argument. When the demonstrative pronoun refers to an entity, más\(_{\textsc{clausal}}\) is required, since esoe, being of type e will not provide the right input to a comparative marker like más\(_{\textsc{degree}}\).Footnote 14 This choice comes with a number of consequences. First, the standard must denote a set of degrees. One possible LF is provided below.

The computation proceeds as explained in Sect. 5.1 above. The denotation of the CP in the standard is the set of degrees d such that the referent picked by esoe is d-tall. This difference with respect to the de case in (5)/(40) captures their semantic difference from que, the comparison is always between individuals along some scale, whereas with de comparatives, different degrees are compared directly. In order for the CP to arrive at a 〈dt〉-type denotation, movement of a wh-operator within the subordinate clause is required. Since the source of the degree is clausal, material other than esoe could be spelled out, accounting for the fact that que comparatives may have more than one remnant (see (21) above).

There is, in addition, a further semantic prediction of the present analysis. In the semantics literature, one can find two types of semantic definitions for the comparative marker: those that require rearrangement at LF and those that do not. For the case of que comparatives, we have assumed a classical approach that requires más to be mobile, if only for type reasons. In the case of de, however, no mobility is predicted, since the lexical entry in tandem with the syntactic geometry allows every piece to be interpreted in-situ. This is shown schematically below.

Not only can the computation proceed following the surface arrangement, but in fact movement from out of the DegP is not possible without further stipulations: if más moved, it would not find any other gradable predicate in the structure to take as its first argument. If the standard moved, the same problem arises: it will not find any predicate of degrees that would take it as an argument; and if the two moved, leaving traces of type d in each case, there would be a type clash with the gradable predicate. Thus, the immediate consequence is that, all else equal, we expect DegP to take low scope with respect to other operators in the sentence (e.g. subjects, sentential negation, intensional verbs, etc.).

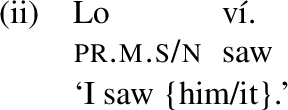

For reasons extensively discussed in Rullmann (1995), Kennedy (1997) and Heim (2001) a.o., one must be careful when trying to prove the scopal mobility of comparative markers like más.Footnote 15 Scope interactions must be tested using either a non-monotonic differential (like exactly n) or switching from more to the downward-entailing comparative less. In those situations, it can be argued that DegP interacts with some intensional verbs (example from Heim 2001).

The example in (49) is ambiguous: when DegP takes low scope, the sentence has the strong meaning that the paper is not allowed to be as long as 10 pages. If DegP takes high scope, the sentence provides a weaker meaning, namely that the paper is not required to be as long as 10 pages. That is, the paper is shorter than 10 pages in some accessible world, but it could be that it is longer than 10 pages in some other.

In Spanish, too, it is possible to reproduce this ambiguity with que.

The low scope reading of (51) states that there is an upper bound on the height of Pedro’s jump, whereas such restrictions do not come to being if DegP scopes above the intensional predicate. Thus, if Pedro jumps higher than Juan, he will meet the requirements only under the high scope reading of (51), but not under the low scope reading. This is the same weak reading that arises in (50b). (The same ambiguity arises with demonstratives like esoe and ése.) Therefore, this constitutes a good test for looking for truth-conditional ambiguities between different scope configurations also in Spanish. In (52) below, the context imposes a weak requirement, namely that Pedro jump some height below what Juan jumped. In this context, utterance of a de variant of (51) is odd:

The incompatibility of examples like (52) in these contexts provide support for the conclusion that de comparatives are scopally inert. In contrast, the ambiguity of examples like (51) show that que comparatives do allow DegP movement.

To sum up, this section provided evidence for a characterization of de comparatives as not involving complex structure with multiple LF movements, in contrast to garden-variety comparatives with que. In fact, every aspect of the derivation of such constructions can be kept minimally simple just by assuming that the standard of comparison must denote a degree and that it does not have a clausal source. This type of “direct” semantics has been argued to be independently necessary for cases of contextual comparison, which are ubiquitous across languages (Kennedy 2009; Beck et al. 2012). Thus, the analysis accounts for the syntactic limitations of de comparatives, and it does so by appealing to a comparative construction that is attested elsewhere. These results are moreover in accordance to the hypothesis put forth earlier in (3), where it was suggested that de comparatives are subject to two distinct conditions, one syntactic and one semantic. This analysis is able to capture this intuition and fits well with the general sentiment expressed in the previous literature, that de comparatives are specialized to compare “quantities” directly.

6 Extending the analysis: relative clauses

So far I have presented how the analysis applies to standards of comparison that were d-denoting. But this is not immediately obvious with all standards that are compatible with the standard morpheme de. As shown in Sect. 2, certain relative clause constructions are compatible with de comparatives, a fact that has been used in the past to argue for the syntactically clausal nature of their standards (see Plann 1984). From a semantic standpoint, it is also not immediately clear how such relative clause constructions come to denote definite descriptions of degrees, which is the denotation required by the comparative marker más in de comparatives if the above analysis is on the right track. The goal of this section is to show that the same analysis can be extended to cases where the standard of comparison is given by a relative clause construction.

6.1 Degree relatives

In order to extend the analysis outlined above to degree relatives we must show that the relevant relative clauses meet the syntactic and semantic criteria laid out in (2): they must be syntactically nominal, and they must denote a definite description of a degree, of type d.

There are two kinds of relative clauses that are compatible with de comparatives in Spanish: free relatives headed by the degree relative pronoun cuanto (“how much”) and relative clauses with an elided head.

Both sentences above yield the same semantic interpretation: the number of trouts fished by Pedro is greater than the number of trouts fished by the speaker. Thus, intuitively at least, both relative constructions seem to refer to degrees—amounts in this case—rather than individuals. This behavior is not unique to Spanish. In English too, relative clause constructions can receive degree interpretations without containing any overt degree morphology, an observation that goes back to Carlson (1977). When they give rise to these interpretations, the relative clause constructions are commonly referred to as “amount” or “degree” relatives. Consider the following example, from Heim (1987):

The sentence in (53) is ambiguous between an ordinary individual and a degree interpretation. In the first case, the relative clause is interpreted as a run-of-the-mill restrictive relative clause, where the relative clause is intersected with the head champagne (Partee 1973), yielding the odd interpretation that involves drinking champagne from the floor. Under its more natural interpretation, however, the sentence refers to the amount of champagne that they spilled. This is precisely the degree interpretation of (53). Free relatives are no different in the availability of the individual/degree ambiguity, and they may also range over degrees as well as over individuals. The following is an example from Carlson (1977), where the degree reading is again more salient:

Spanish also displays the same type of ambiguity in the same contexts. For one, ordinary relative clauses are also compatible with degree readings in the general case:

Moreover, Spanish also behaves like English in contexts like (54). In the absence of a counterpart to the relative pronoun what, the composite form lo que must be used, which, like in English, can denote both individuals and degrees. Under the degree interpretation, (56a) is equivalent to (56b) with the quantity relative pronoun cuanto.

In sum, these examples show that referencing degrees via relative clauses is by no means unique to Spanish. Most analyses of degree relatives resort to degree semantics to account for degree interpretations like these (Grosu and Landman 1998; von Fintel 1999; Herdan 2008; Meier 2015; Mendia 2017 a.o.). The main idea according to this type of analysis is that the relative clause provides a set of degrees: a CP-internal copy of the head of the relative clause is modified by an indefinite determiner with a semantic interpretation akin to much/many, and a wh-operator moves at LF creating a degree denoting lambda-abstract. In the case of (53), the result is a set of degrees at CP level, representative of the quantity of champagne that they spilled.

In the next section I lay out the syntactic and semantic assumptions that, building up on structures like (57), allow relative clause constructions to denote definite descriptions of degrees.

6.2 Syntactic and semantic housekeeping

Syntactic assumptions

Following Sáez del Álamo (1999) and Brucart (2003), I assume that the relative clauses that participate in de and que comparatives are in fact different. For de comparatives, I endorse the idea that [D que] constructions constitute free relatives, where the cluster [D que] functions as a complex relative pronoun akin to cuanto (Real Academia de la Lengua Española 2010), for instance in the following configuration.

Comparatives with que, instead, take regular headed relative clauses whose head, when missing, has simply been elided; they thus conform to the following geometry:

There are a number of reasons to believe that, despite the string-identity, the two standards combine with different structures. First, only que comparatives are freely allowed with both headed and null head relative clauses; de comparatives do not easily allow headed relative clauses (but see the discussion in Sect. 7.2).

Second, free relatives do not accept intervening material between the determiner and the complementizer. As indicated by the glosses, sentences like (61a) where a modifier is disrupting the [D que] cluster cannot get a comparative interpretation (the only available interpretation is a partitive). In the case of quantity free relatives, further modification of the relative pronoun results in ungrammaticality.

Third, comparatives with que are possible also if we replace the definite determiner by any other determiner or demonstrative. This is not possible with de comparatives, suggesting that [D que] indeed acts as a complex relative pronoun in a free relative, admitting no other constructions.Footnote 16 In (62) we have a demonstrative pronoun modified by a relative clause, and only the que variant can constitute a comparative construction (the de variant can still get a partitive interpretation).

Thus, I take it that (i) [D que] clusters behave in every respect like relative pronouns and that (ii) relative clauses in de comparatives are always free relatives, whereas (iii) relative clauses in que comparatives are ordinary headed relative constructions with a possibly elided head.

Semantic assumptions

Following Jacobson (1995) and Caponigro (2002) I assume that free relatives are semantically equivalent to definite descriptions. In particular, building on Rullmann (1995), I take quantity free relatives to denote maximal entities, i.e. definite descriptions of degrees. I also follow Jacobson (1995) and Caponigro (2004) in assuming that wh-words in definite free relatives and in wh-interrogatives are the same lexical item and contribute the same semantics in both constructions—as attested by the fact that in Spanish both can be complements of verbs that select for propositional and nominal complements.

Below I sketch one possible way of arriving at this result. The idea is that the relative pronouns cuanto and [D que] embody the otherwise null operator Op which A̅-moves to the edge of CP and is interpreted as λ-abstract over degrees.Footnote 17 Schematically:

In the lower position, the quantity relative pronouns cuanto and [D que] leave a trace of type d. This trace combines then with a gradable predicate which can be supplied in one of two ways: by means of a possibly elided adjective, or by means of a silent measurement operator manyμ/muchμ modifying an NP (Schwarzschild 2006; Rett 2014; Solt 2014 a.o.). The role of the measure function is simply to map entities to degrees, just like a regular gradable predicate. As it was pointed out above in Sect. 3, ϕ-morphology on the relative pronoun correlates with the target of the comparison: if the relative pronoun contains non-neuter ϕ-features, the comparison can only range over degrees of cardinality (or volume for mass nouns), and so the only dimension that is accessible to muchμ is quantity. On the other hand, predicative comparatives come with their own gradable predicate and trigger neuter ϕ-features, thereby precluding the use of manyμ/muchμ.

Finally, following Rullmann (1995), I assume that a maximality operator max extracts the maximal degree from the property of degrees denoted by the CP. To keep derivations short I assume that max is introduced by the wh-operator itself, as in Rullmann (1995), but see fn. 17. For [D que] I generalize the definition so that it can take properties of both individuals and degrees.

The general structure of the relative clause looks as in (66b). The result of the derivation is the maximal degree d, such that the number of things x that Pedro ate is d.

The object in the subordinate clause must undergo Comparative Deletion, which is known to be different from ordinary elliptical processes in that it is not optional (see Lechner 2001 and Kennedy 2002 for discussion). With this background we are ready to spell out the analysis of de comparatives when they take a relative clause as the standard of comparison.

6.3 Degree relatives in comparative constructions

The derivation of a predicative case proceeds exactly as we saw in Sect. 5.2. Take a sentence like (67).

First, the subordinate clause provides a degree as explained above. The LF of the free relative is represented in (68), its denotation is calculated in (69). In this case, the measure function in the subordinate clause is set to the dimension of height.Footnote 18

The rest of the computation proceeds as described for the simplex cases in Sect. 5.2. The full syntactic structure is represented (70), its final truth-conditions calculated in (71).

These are the right truth-conditions: they simply state that Pedro’s maximal height exceeds yours.

Consider now instead the case of attributive comparatives like (72).

There are two main differences between attributive and predicative comparatives. The first difference is that, unlike in predicative cases, the comparative marker más in (72) cannot directly combine with its restrictor, since nouns are not of a suitable type—they are not gradable predicates. To solve this problem, I assume that nominals come with a silent Measure Phrase, where the head denotes a function meas that relates an individual to a degree, in that order (e.g. Solt 2014; note that meas and manyμ are curried differently).

The function meas and the NP cannot yet combine, since their types do not match (〈e,dt〉 and 〈et〉 respectively). Moreover, the motivation for introducing meas is to create a gradable predicate, and so the resulting phrase [meas NP] must be of type 〈d,et〉; that is, existentially closing the NP will not do. The problem is solved by appealing to the mode of composition Degree Argument Introduction, suggested and independently motivated by Solt (2014):Footnote 19

The mode of composition DAI is reminiscent of Variable Identification (Kratzer 1996), except the argument targeted for composition in this way—the individual argument—is demoted to the second position in the lambda prefix. The semantic computation of más and its restrictor is illustrated below.

The second difference with respect to predicative comparatives is the treatment of the object which, being of type 〈et〉, cannot serve as argument to a transitive verb. I argue that rather than providing an argument to the verb, these objects semantically restrict its denotation: instead of the verb taking the object as its argument via Functional Application, they combine via Restrict (Chung and Ladusaw 2004).

This mode of composition has three main properties: (i) it identifies the first two e-type variables in the two expressions (x and z above), (ii) it does not saturate the argument slot of the verb and (iii) and it demotes the lambda term corresponding to the modified argument to the last position. As a result, after combining with the object, a transitive VP will not denote an 〈et〉 function; it will still be of type 〈e,〈et〉〉, but the order of the arguments in the lambda prefix will have switched with respect to the original denotation of V.

There is independent motivation for Restrict. Nominals combining via Restrict show a number of properties. First, they take lowest scope with respect to other sentential operators (e.g. McNally 2004). In Sect. 5.3 we saw that this was the case for simplex de comparatives and below in Sect. 6.4 we will see that this is the case as well for de comparatives taking degree relatives. Thus, this immediately rules out resolving the offending type mismatch by appealing to scope-shifting type shifters, such as A (Partee 1987) and, in general, any operation requiring Quantifier Raising.Footnote 20

The second argument for Restrict is that only nominals combining via Restrict are compatible with existential constructions with the copulative verb haber. As López (2012) shows, NPs with either definite or indefinite determiners are ungrammatical as complements to haber, and so these objects must be semantically incorporated to the verb (note the unos variant is grammatical with a locative coda).

Comparatives as well as degree relatives are grammatical in these contexts, suggesting that Restrict may be the main mode of composition in such cases.

Now everything is in place to provide an analysis of (72). The LF of the free relative is as in (79), its derivation proceeds as in (80). By adopting Restrict, we allow the semantic computation to proceed as if the object slot of the predicate were saturated, when in fact it is not. Existential closure at the TP level closes the remaining unsaturated argument slot, bringing the valency of the predicate to zero.Footnote 21

As before, the standard denotes a maximal degree. The rest of the derivation proceeds as expected. The nominal restrictor combines by DAI with the silent predicate meas to form a gradable predicate, that is then taken by the comparative marker as argument. Then, DegP restricts the denotation of the verb.Footnote 22

The resulting truth-conditions correctly claim the existence of some apples that Pedro ate in an amount greater to the amount of (different) apples that Juan ate.

6.4 Assessment

Like before, the analysis successfully derives the fact that de comparatives cannot express comparison to an individual. The standard de can only combine with objects denoting a definite degree, and so the construction is only compatible with a small number of standards.

There are other welcome semantic consequences, as well. A first consequence is the prediction that, without further stipulations, scope interactions between DegP and other operators should not be expected. Like in the cases discussed in Sect. 5.2, this is what we find. In (51) above we showed that a que comparative taking an individual denoting standard is ambiguous in the same way as reported for English in Heim (2001). In the case of de comparatives, this ambiguity is not present: (84a) cannot be used to express the weak claim that the jump does not need to be higher than Juan’s height; it can only mean that the jump is required to be less high than Juan.

These facts are in line with the use of Restrict as the main mode of composing Degree Phrases with verbal predicates in de comparatives.

A second welcome prediction is that the contrast in (13) is captured.

Let us first clarify how the derivation of (13) proceeds with que. This is possible with our current assumptions about que comparatives by applying a number of LF movements (as in, e.g. Beck 2011).

The truth-conditions derived for (85) are the following, which seem to be in place:

As argued before, que comparatives do not involve free relatives, but headed relatives with a sometimes silent head. In the example above, the denotation of the standard corresponds to the set of degrees d such that I fished d-sized trouts. This is a good input for the clausal comparative marker in (37a), but it is unusable for the degree comparative marker in (42), as required by de comparatives.

The current analysis provides a new insight for the ungrammaticality of (13) in terms of semantic ill-formedness. Recall that non-neuter ϕ-morphology on the relative pronoun requires the selection of the silent measuring operator manyμ, which in turn maps entities to cardinalities. As a consequence, when the standard of the comparison is introduced by a relative pronoun showing plural morphology, the dimension of the measuring operator is set to quantity. What this means is that in (13), the de-variant would involve comparison across two dimensions—size and quantity.

This is a case of incommensurable comparison, that is, a comparison constructed from gradable predicates that measure along distinct dimensions. Given our semantic assumptions, degrees can be compared if and only if they belong to the same scale, so that they can be ordered with respect to each other. It is therefore impossible to carry out a comparison between degrees that belong in different dimensions because they are not ordered, rendering them incomparable. This kind of ban on incommensurability is “a signature property” of ordinary comparatives (Morzycki 2011). If incommensurable comparison is not allowed in natural languages (outside, perhaps, of metalinguistic comparatives), the ill-formedness of (13) with de does not come as a surprise. Further evidence for incommensurability comes from the fact that phrasal attributive comparatives with de are possible, at least for some speakers, if the noun modified by the numeral is a measure noun that relates to the same dimension of the restrictor. The kind of adjectives these constructions allow is quite limited, since the dimension of the noun has to belong to the same dimension of the gradable predicate (e.g. “long” and “meters” in the dimension length, “heavy” and “kilos” in the dimension weight, etc.); otherwise the construction is not possible.

The same constructions are not freely available with a noun in the restrictor position, and although rare they are not completely unattested. The following are two such cases.

The following examples show a similar case. Here de comparatives appear with a headed relative clause where the head refers directly to the scale that the adjective is interpreted in (as in “fast” and “speed”, etc.). This type of example is also rare, but not unattested.

Thus, what looked like a syntactic restriction on de comparatives is here derived as a semantic restriction, as a ban on cross-dimensional comparison.Footnote 23

7 Extensions and further issues

If the present analysis is on the right track, then Spanish de comparatives involve a special type of comparison which is subject to both syntactic and semantic restrictions. In this section, I discuss where within the cross-linguistic landscape of comparative constructions de-comparatives may be placed. Before closing, I will also point to some further issues that arise as a consequence of my analysis.

7.1 Cross-linguistic significance

The combination of syntactic and semantic well-formedness conditions Spanish de-comparatives are subject to points to a hitherto unnoticed locus of cross-linguistic variation. With respect to the typology of standard morphemes, the literature so far has taken the main axis of cross-linguistic variation to be syntactic. For languages that display more than one standard morpheme it has been argued that the choice depends solely on the phrasal vs. clausal nature of the standard; i.e. on its syntactic size. This is the case for Greek (Merchant 2009), Russian (Pancheva 2006) and Hungarian (Wunderlich 2001), a.o. The distinguishing property of these languages is that they syntactically discriminate between true phrasal comparatives and reduced clausal comparatives: in true phrasal comparatives, the standard is nominal, a DP, whereas in reduced comparatives all the material from the CP in the standard is removed, except the DP that is being compared to its associate. In languages like the ones mentioned above, reduced clausal comparatives differ from phrasal comparatives in the DP standard, whose case marking reveals its true clausal nature and, crucially, on the standard morpheme. Below in (91) I illustrate with Hungarian (examples from Wunderlich 2001).

In languages with a single standard morpheme, phrasal and reduced clausal comparatives, if available, are surface-identical (cf. English).

Spanish is Hungarian-like in that more than one standard morphemes coexist within a single language.Footnote 24 The difference between de and que comparatives in Spanish, however, does not track the differences found in languages like Hungarian. Even though de comparatives are always phrasal, it is not possible to form just any phrasal comparative with de (see Sect. 4). As was argued earlier, the restriction on the kind of standards that de comparatives admit is partially established by certain semantic criteria as well: concretely, the standard of the comparison must denote a definite description of a degree. To my knowledge, none of the languages previously discussed in the comparatives literature have been noted to impose a semantic restriction that the comparison be to a degree.

That said, there are reasons to believe that such semantic restrictions are not exclusive to Spanish. An interesting comparison point for Spanish de-comparatives might a type of clausal comparative in Japanese. Japanese, like English, has two constructions that, on the surface at least, seem to reflect a phrasal/clausal distinction (examples from Sudo 2015).

Observing that Japanese clausal comparatives in (92b) do not quite behave like English run-of-the-mill clausal comparatives (see Beck et al. 2004 and Sudo 2015 for discussion), recent studies (Hayashishita 2009; Bhatt and Takahashi 2011; Shimoyama 2012) have claimed that Japanese clausal comparatives motivate a new kind of clausal comparative. Other authors (Beck et al. 2004; Oda 2008; Kennedy 2009; Sudo 2015) have argued instead that Japanese clausal comparatives show properties characteristic of complex DP constructions, treating the complement of yori as a DP rather than a CP. For instance, Sudo (2015) argues that the underlying structure of so-called clausal comparatives like (92b) contains a hidden nominal that is deleted under identity conditions.

Sudo (2015) attributes the ungrammaticality of certain comparative constructions in Japanese to the fact that none of the possible underlying structures are grammatical themselves. That is, a clausal comparative like (94) is argued to be grammatical because one of the underlying phrasal comparatives, namely (95a), which involves a measure noun, is acceptable.

The rationale of this analysis resembles the explanation we offered above for examples like (88)–(90). In both cases, these DPs involve degree/measure nouns, nouns that are intrinsically related to some scale (like the nouns amount, size, height, weight etc.). Although Sudo (2015) does not provide a semantic analysis of the Japanese facts, he does provide good syntactic evidence that the hidden nominal must be present. Thus, Japanese provides at least one case where the well-formedness of a comparative construction relies on both syntactic and semantic considerations; in the best case scenario, the analysis provided here may apply there as well.Footnote 25

7.2 Odd ends

As is well known, comparatives with de do not easily allow comparison between quantities of two different objects. This is reflected by the impossibility of forming de comparatives with headed relative clauses as standards, a restriction which is sometimes referred to as the Single Sortal requirement.

The main issue with (96) comes from the contradictory evidence in the literature with respect to whether the Single Sortal requirement applies across the board. While the ungrammaticality of (96) is uncontroversial, sentences where the head is present but identical to the restrictor of the comparative marker are acceptable for some speakers, as illustrated by the following pair of conflicting judgments from Sáez del Álamo (1999: 1133) and Gutiérrez Ordóñez (1994a: 38) respectively.

It is difficult to determine what lies behind this variability. The present analysis rules out (96) in the syntax, by assuming that the sentence contains a free relative, which are headless by nature. If so, it could be that the different behavior of the cases in (97) reflects simply a preference for NP-ellipsis, in that some speakers are more accepting of lack of elision where it would ordinarily happen. In such cases, we might expect these speakers to be more charitable with overtness in other similar environments, e.g. with comparative deletion. However, the issue is further confounded by the fact that cuanto and [D que] clusters can be relative pronouns as well (see Sect. 6.2). This type of syntactic rationale would explain the ungrammaticality of (96) and (97b), but is at odds with the grammaticality of (97a).

One could alternatively think that the ill-formedness of (96) is not syntactic, but semantic. For comparison, recall (90b), a case where a de comparative appears with a headed relative clause whose head refers directly to the same scale of the adjective.

The same kind of configuration obtains with so-called Degree Neuter Relatives, formed by a modified gradable predicate and the neuter definite determiner lo (cf. (33) and (34) above).Footnote 26

In view of the ill-formedness of (96) and the availability of examples like (90b) (repeated above) and (98), it would seem that what de comparatives require is not so much a certain kind of relative clause construction, but a semantic condition that both the restrictor of más and the standard denote in the same dimension—as this effectively allows the two degrees to be ordered with respect to each other and avoid issues of incommensurable comparison. If so, the ill-formedness of (96) would follow from the fact that “quantities of trouts” and “quantities of sardines” belong to different scales, whereas (90b)/(98) simply establish a comparison between different degrees in the same scale, along the dimensions of speed and distance. Then, the rarity of cases like (90b)/(98) could derive from the fact that noun-adjective and adjective-adjective pairs referring to the same scale (e.g. ‘speed’/‘fast’ and ‘width’/‘length’) are themselves scarce. The problem with this semantic explanation is, of course, that the ungrammaticality of (97b) is left unexplained.

The resulting state of affairs is one where, either way, one of the two sentences in (97) is left unexplained. Moreover, choosing one strategy or the other comes with consequences that deserve more discussion than space limitations permit here, so I will leave these questions open.Footnote 27

A final issue that this paper is leaving open pertains the semantic contribution of the two comparative markers. In accordance to the vast majority of the literature, I have assumed throughout that que and de are semantically vacuous. Because of this choice, the unique compatibility of de with más\(_{\textsc{degree}}\) is a matter of a two step process: first the preposition de c-selects for a nominal complement which, in turn, denotes a definite description of degrees and thus can only provide a suitable input for másdegree, but not másclausal. A similar reasoning accounts for the unique compatibility of the que standard morpheme with másclausal. Nevertheless, recent works in the literature have suggested that than in English should be in fact interpreted (cf. Alrenga et al. 2012; Alrenga and Kennedy 2014; Wellwood 2015). From a cross-linguistic perspective, this is certainly a promising venue: as Alrenga et al. (2012) emphasize, languages that morphologically mark a phrasal/clausal distinction usually do so by means of different standard morphemes, and yet assuming that these morphemes are semantically vacuous forces us to have ambiguous comparative markers whose different exponents are never reflected morphologically. On the other hand, assuming that que and de are semantically bleached is better understood from the perspective of their syntactic distribution, and thus tailoring their semantics to operate on degree constructions would lead to systematic ambiguities in this respect. The question remains open, and my hope is that the results reported in this paper will help future work on the division of labor between comparative markers and standard morphemes.

8 Conclusion

This paper examined two types of comparative constructions in Spanish, differentiated on the surface by the morpheme that introduces the standard of comparison. This standard morpheme can either be the complementizer que (“that”) or the preposition de (“of” or “from”). The main descriptive difference between the two standard morphemes is the highly restricted distribution of de when compared to que. It was argued that (i) comparatives introduced by de always express comparison to a degree, and so, the standard of comparison is always, in all these cases, an object whose denotation must be of type d; and (ii) de comparatives can only take nominal standards (DPs, Number/Measure Phrases), and so they always constitute phrasal comparatives. A formal analysis was provided that captured these generalizations and made further welcome empirical predictions, e.g. the consistent low scope of de-comparatives.

The analysis has interesting consequences for the overall landscape of comparative semantics. For one, comparison to a degree is a very common phenomenon, found in most languages which express comparisons with dedicated constructions. Similarly, it is very common to find languages that, lacking a dedicated morpheme to specify the standard of comparison, utilize more than one morpheme that already exists in the language. This paper argued that Spanish displays a division of labor between two morphemes that has not been noted before in the literature: the criteria for picking one or other standard marker depend on syntactic as well as semantic properties. By identifying this new axis of cross-linguistic variation, the paper contributes to our understanding of the semantics of comparatives, as well as the different strategies that natural languages have available to form comparative constructions.

Notes

For an overview, see Sáez and Sánchez López (2013). Works that have attributed the limited distribution of de comparatives to syntactic factors include Bolinger (1950, 1953), Solé (1982), Plann (1984), Price (1990), Gutiérrez Ordóñez (1994a,b), Sáez del Álamo (1999) and Gallego (2013), a.o. Works that have tried to explain it in terms of the denotational properties of de comparatives include Bello (1847), Prytz (1979), Rivero (1981), and Brucart (2003), a.o.

Here “degree” is used as an umbrella term that covers all types of measures; quantities, amounts, sizes, volumes…all are referred to as degrees.

The struggle to characterize the source of this variation is not new: Bello (1847: 301) already notes that although que may be admissible in some contexts similar to (5), the de variants “sound better” (sic).

The sentence in (7) is grammatical as a partitive construction, which also makes use of the preposition de, resulting in a construction superficially identical to a comparative construction. They are not to be confused. In these cases, the interpretation of the sentence is that of a simple additive; for (7), we have that Pedro ate some more apples from that set of apples. Unless specifically noted, all the reported judgments are about comparative constructions alone.

As before, the sentence may be construed as a partitive construction interpreted as a simple additive. Judgments only address the comparative constructions.

As an anonymous reviewer points out, there could be independent reasons to rule out configurations like (21b), such as difficulties to recover a meaningful antecedent. Thus, while an underlying structure like “Yesterday my robot jumped more than 〈

my robot jumped〉 [that-much]d today” is conceivable and interpretable, its interpretation involves additional steps which may result in further complexity.The speaker variation mentioned earlier in Sect. 2.1 with respect to (5) could be related to que’s greater flexibility: it is conceivable that while in some idiolects que expresses any comparison, thus overlapping with de uses, in others the two are in complementary distribution. In comparison, the data regarding the distribution of de comparatives is much clearer, only with a few exceptions; see Sect. 7.2.

This is a difficult task. Given current degree-based analyses of comparatives, standards of comparison also constitute degree expressions even in clausal comparatives—either a maximalized degree (type d) or a set of degrees (type 〈dt〉). Moreover, one could appeal to a theory where the standard moves from its base position, resulting in a type d trace in the launching site. These concerns are difficult to address partly because the discussion quickly leads to theory-dependent reasoning. Thus, it could be that the right choice of theoretical assumptions captures the properties of de comparatives by appealing solely to a semantic requirement. While I regard this as a possibility that is worth exploring further, I will continue to assume that de comparatives are subject to a syntactic as well as a semantic restriction, as expressed in (3).

In fact, many theories derive truth-conditions for (33) along the following lines: the degree d such that the table is d-long > the degree d’ such that the table is d’-wide, where two definite degrees are said to be in a “greater than” relation to each other.

The adjective ancha in the subordinate clause overtly moves to the edge of the clause, prior to the movement of the operator that abstracts over degrees. This inversion pattern is known from Spanish focus inversion constructions (Ordóñez 1997) as well as questions (Ormazabal and Uribe-Etxebarria 1994), and comparatives (Reglero 2007).

This categorical distinction can be formally captured by exploiting the fact that the two standard morphemes belong to two distinct syntactic categories, thereby imposing different c-selectional restrictions. This can be modeled by means of uninterpretable features [uF], syntactic features which must be valued by a matching [F] feature on its sister node, and some principle (e.g. Full Interpretation) that obligatorily requires all uninterpretable features to be deleted prior to interpreting any one tree structure (e.g. Chomsky 2001). As is usually assumed, we can take the feature specification of a preposition such as de to be [P,uD], and that of a complementizer like que to be [C[-wh],uT], effectively forcing de to take DP and que to take TP complements.

Notice that, although PPs may extrapose in certain contexts like (i), this is not allowed when they are embedded within a Degree Phrase, as in additives (ii).

As mentioned earlier in Sect. 4, it is possible that a third different más is required for certain phrasal que comparatives after all. If so, it is an open question whether the best analysis of (6) involves such a third type of standard marker or just más\(_{\textsc{clausal}}\). The scope data discussed below lends preliminary support for más\(_{\textsc{clausal}}\).

As Kennedy (1997) showed, DegP can never scope beyond a quantificational DP in subject position. This is known as the Kennedy/Heim Constraint: if the scope of a quantificational DP contains the trace of a DegP, it also contains that DegP itself. Moreover, Heim (2001) showed that not every scope ambiguity translates into a truth-conditional ambiguity, making putative scope movements of DegP hard to assess.

For this reason too, [D que] structures cannot be light headed relative clauses, in the sense of Citko (2004). Light headed relatives are relative clause constructions with a semantically “light” lexical head, usually a pronoun or demonstrative. Citko (2004: 98) provides the following example from Polish.