Abstract

In this article I provide a syntactic analysis for the non-standard liketa and its uncontracted counterpart liked to in Appalachian English. I argue that both forms are verbal and are related via restructuring, following similar analyses of wanna contraction. However, liketa is different from wanna in that it places unique aspectual restrictions on its complements. Specifically, it requires that the verb appearing immediately to the right be marked with past participle morphology for felicitous interpretation. A comparison of liketa and liked to reveals that both are verbal and liketa has many hallmark properties of restructuring predicates. In fact, it shares many properties with wanna contraction, an example of restructuring in English. I analyze liketa in the spirit of Wurmbrand (2001) who provides a mono-clausal approach to restructuring. I consider dialect variation among grammars which allow slightly different syntactic constraints on the usage of liketa. Finally, I sketch out an alternative bi-clausal restructuring account in order to compare the consequences of two prominent theories of restructuring verbs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this paper, I provide a syntactic analysis of the understudied form liketa in Appalachian English as spoken in eastern Kentucky. Data in this paper stem from the author’s native speaker intuitions. These intuitions were checked against the intuitions of five informants from the small communities of Chloe Creek and JonancyFootnote 1 in Pike County, Kentucky as well as the community of McRoberts in Letcher County, Kentucky.

In Appalachian English, the lexical item liketa pronounced [laktə] is often used to describe events which ‘came close to happening but which did not happen’ (Wolfram and Christian 1976: 91).

-

(1)

-

a.

John has liketa punched Bill.

-

b.

John had liketa punched Bill before you arrived.

-

a.

-

(2)

-

a.

John has almost punched Bill.

-

b.

John had almost punched Bill before you arrived.

-

a.

Example (1) shows that liketa is compatible with both the past and present tense marked auxiliary have. In these examples the meanings of almost and liketa are the same. Further, the meanings of (1) and (2) are identical in the case of achievement verbs like punch. However liketa only has a subset of the possible meanings attributed to almost when modifying accomplishment verbsFootnote 2 (Johnson 2013; Wolfram and Christian 1976). Modulo tense, they share the meaning in (3)

-

(3)

John came close to punching Bill before you arrived, but he did not punch Bill before you arrived.

Liketa in Appalachian English has an uncontracted counterpart. Consider the contracted form below with the non-contracted form in (4b).

-

(4)

-

a.

John had liketa punched Bill before you arrived.

-

b.

John had liked to have punched Bill before you arrived.

-

a.

For clarity, the meaning is the same for both forms. I take the phonetic difference between liketa and liked to in normally paced speech to be one of vowel reduction commonly found with contractions. The [u] in [laktu] in the non-contracted form corresponds to [ə] in the contraction [laktə]. I make this distinction only to clarify what the difference between these two forms sounds like for non-dialect speakers.

In the non-contracted liked to form, the auxiliary have and past participle morphology on the verb are required.

-

(5)

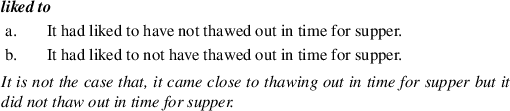

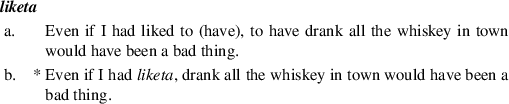

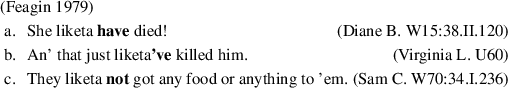

Example (5a) shows liked to is acceptable with an infinitival complement containing auxiliary have. Example (5b) shows that liked to accepts a bare form in its complement. (5c) shows that participle morphology is not licensed under liked to without a corresponding overt auxiliary have. Finally, comparing these facts, I conclude that only infinitival complements containing auxiliary have are licensed under liked to.

With contracted liketa however, the embedded auxiliary is banned but the participle is required. Example (6a) shows that liketa is acceptable with only past participle morphology on the embedded verb. Example (6b) shows that past participle morphology on the embedded verb is required and yet the overt auxiliary in (6c) is banned.

-

(6)

Thus the difference between the two forms is that auxiliary have is not licit under contracted liketa, even though the participle morphology is required on the embedded verb. Specifically, I argue that the verb directly embedded under liketa bears morphology associated with the English past participle. Evidence supporting this claim is discussed below in Sect. 3. However, briefly consider the following evidence that simple past verb forms are insufficient under liketa.

-

(7)

The failure to take a complement headed by overt have is unique to liketa. Notice that no such restriction holds for wanna or gonna contraction; assuming they are contracted forms of want to and going to.

-

(8)

In summary, liketa in Appalachian English is similar in meaning to almost. Within the dialect it exhibits morphosyntactic variation. It can appear as the contracted liketa or the non-contracted liked to. Liked to selects for an infinitive participle form of the verb and liketa appears to select only for a participle form of the verb. However, contracted liketa requires participle morphology on the embedded verb but does not allow an overt embedded auxiliary have. This fact is unique to liketa as other infinitival contractions do not seem to exhibit this restriction.

I argue that we can capture the syntactic relationship between liketa and liked to in a way that accounts for the ban on auxiliary have in the contracted form. More specifically, I will argue that both the contracted and non-contracted forms are verbal and that the relationship between them, including the ban on embedded auxiliary have, is best captured in terms of restructuring or clause union. Such an analysis informs the syntax of infinitival contractions such as wanna, gonna, hafta as well as the morphosyntax of auxiliary selection in embedded clauses. My analysis will account for the allowance of auxiliary have under wanna contraction as well as variation in liketa between grammars. I will then compare analyses of liketa in Appalachian English in two different theories of restructuring. I argue that the mono-clausal approach found in Wurmbrand (2001) is superior to a bi-clausal head movement approach found in Roberts (1997).

This paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, I will briefly review previous observations about liketa. Then, I will provide a syntactic analysis of the form in Sect. 3 showing that liketa is verbal. Section 4 concerns liketa’s complement clauses and introduces the notion of restructuring verbs and their complements. In Sect. 5, I argue that some instances of infinitival contraction are instances of restructuring. The analysis of liketa is in Sect. 6 along with a discussion of alternate varieties of liketa, and a comparison of restructuring mechanisms. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Previous work on liketa

In this section, I discuss the observations that have been made about liketa beginning with Walt Wolfram and Donna Christian’s observations from Appalachian English in nearby West Virginia. Then I will move outward to observations about liketa in African American Vernacular English of New York from Labov, and Feagin’s observations from Alabama English. Lastly, I present some observations taken from various written language corpora.

2.1 Adverbial accounts of liketa

Wolfram and Christian (1976) discuss liketa as it occurred in Mercer and Monroe counties in southwestern West Virginia. The data consists of 33 tokens of liketa in at least 42 hours of conversation from 52 sociolinguistic interviews.Footnote 3

-

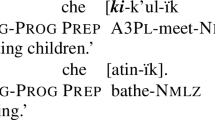

(9)

(Wolfram and Christian 1976)

-

a.

And I knew what I’d done and boy it liketa scared me to death.

-

b.

That thing looked exactly like a real mouse and I liketa went through the roof.

-

c.

When we got there, we liketa never got waited on.

-

d.

I liketa never went to sleep that night.

-

a.

Wolfram and Christian (1976: 92) note that “a past form” of the verb is required on the verb that follows liketa. They are not specific about whether those past forms are simple past or past participles. They also note that liketa itself does not bear tense, and there are no cases of liketa appearing in questions or embedded clauses. Finally, they observe that the only negative element that occurs under the scope of liketa is never, as shown in examples (9c) and (9d).

Recall the introductory claim that liketa, at least in eastern Kentucky, requires the past participle morphology on the embedded verb. I would point out that this claim is not at odds with the data from West Virginia which contains what appear to be simple past forms of irregular verbs following liketa. As one reviewer points out, many varieties of AppE exhibit alternate past irregular verb forms. The reviewer notes that went is listed as the past participle form of the verb go in Appalachian English of eastern Tennessee (Montgomery and Hall 2004). Similarly, Wolfram and Christian (1976: 80–84) note that many verbs like get, go, and know commonly exhibit alternate forms in past and participle contexts. For example, they may be found directly under auxiliary have marked with only simple past morphology in the AppE of southern West Virginia. The same is true for AppE in eastern Kentucky.

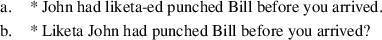

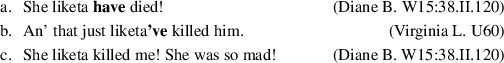

Following observations from Labov (1972) made about liketa in African American Vernacular English of New York City, Wolfram and Christian adopt the idea that liketa must be an adverb because it does not show tense marking in (10a) or undergo subject/aux inversion in (10b).

-

(10)

Here I will summarize the claims from the adverbial accounts of liketa. The negative time adverbial never is the only negation allowed under liketa. The verb under liketa must be marked for past and there are no observed instances of liketa appearing in questions or embedded contexts. Labov and Wolfram and Christian argue that liketa also does not show overt tense marking or invert in questions, ruling it out as an auxiliary verb form. Keep in mind that in Sect. 3, I argue that liketa is verbal, must be marked for the past participle, and does in fact occur in yes/no questions.

2.2 The contraction described

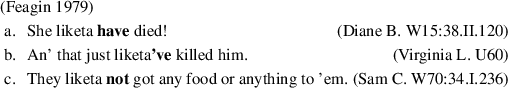

Feagin (1979) describes the distribution of liketa in her corpusFootnote 4 of the Southern English of Anniston, Alabama. She argues that liketa is derived either from the transitive verb liken meaning ‘to see, mention, or show as like or similar’ or from the adjective like. While Feagin refers to liketa as a quasi-modal, she argues that liketa is related to or derived from like to have V-ed. She argues that the verb to the right of liketa is a participle form when it appears with auxiliary have but that the verb may appear in simple past form in cases where auxiliary have is missing. To be clear, if a verb to the right of liketa appears with simple past morphology then Feagin speculates that liketa has undergone some type of grammatical change from selecting a participle to selecting a preterite form. Like Wolfram and Christian she in effect only goes so far as to say that some past morphology is required on the embedded verb and that liketa does not occur in questions or commands.

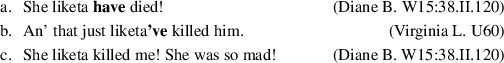

She notes fluctuation in the appearance of auxiliary have in the embedded clause. An auxiliary have either appeared in the data in its full form in (11a), a contracted form as in (11b), or deleted as in (11c).

-

(11)

Out of 70 tokens, liketa occurred with not once (12a) and with never three times (12b–12d). Note that, the bare like forms in (12c–12d) are still reportedly interpretable as approximatives.

-

(12)

Ultimately, the presence of full have in the complement of liketa in Alabama English should only be taken as evidence of different trajectories of grammaticalization in two different dialects. I will revisit this issue after I present my analysis. However, for the moment we must keep the following in mind. The dialect spoken in Anniston, Alabama and the dialect spoken in eastern Kentucky are not the same dialect even if they happen to share cognate lexical items. There is no evidence to suggest these dialects, or individual lexical items within them should behave identically.

2.3 Liketa has a history with auxiliary have

There is a long historical record of the usage of liketa-related forms in various British and American English corpora (see Kytö and Romaine 2005). Kytö and Romaine find that non-contracted constructions like have/had liked to + V, appear as early as the mid-fifteenth century in conditional if clauses.

-

(13)

Kytö and Romaine suggest that liketa has roots in adjectival like, with a meaning of imminent likelihood or probability. In their extensive corpora study, virtually all instances of liketa (contracted or not) exhibit counterfactual meaning when they appear as have/had liked to + V. Beyond this, the majority of constructions involving past tense auxiliary have also exhibit a have auxiliary in the infinitival clause to the right of liketa. There is however a related form be like to + V which features a high be auxiliary instead of the familiar have auxiliary. Interestingly, these be forms tend not to be counterfactual. They are usually only assigned an interpretation of high probability.

Thus, Kytö and Romaine show that the counterfactual interpretation (came close to X, but didn’t X) is strongly associated with past participle morphology and the have auxiliary in both clauses. I show that this historical correlation between the counterfactual interpretation, auxiliary have, and its associated participle morphology remains robust in modern Appalachian English. For example, if we remove the past participle morphology from the embedded verb, then liketa is unacceptable on a counterfactual interpretation (contracted or not). Instead, it is only marginally acceptable and can only be interpreted with the common enjoyment or desire interpretation as in I like bourbon or I like to drink bourbon.

-

(14)

Thus in (14a) and (14b) the only possible interpretation for either form is the common transitive ‘enjoy’ meaning of like.

Previous observations about liketa in AppE, Alabama English, and African American Vernacular English of New York City, may be summarized as follows. What little research there is suggests that liketa is non-verbal, based on the fact that it is not marked for tense. In terms of negation, it allows adverbial never in its complement in AppE and in addition to this, liketa in Alabama English exhibits one token of not. It does not undergo subject auxiliary inversion in yes/no questions and there are no previously observed instances of liketa being embedded or appearing in commands or questions.Footnote 5 Finally, liketa appearing with auxiliary have and so-called past morphology is always accompanied by counterfactual interpretations of completed eventualities. It should be noted that any lack of data in these studies is most likely the result of the sociolinguistic interview process and might even be expected given the rather small number of tokens of liketa in each corpus.

In what follows, I will argue that liketa is a verb which selects for smaller than TP clauses. Thus, we will revisit liketa’s interaction with negation, its lack of ability to undergo subject auxiliary inversion, and its unique interactions with auxiliary have and the assignment of what I argue is past participle morphology in liketa’s complement. I will have nothing more to say about liketa’s observed lack of appearance in commands or embedded contexts.

3 Liketa in the AppE of eastern Kentucky is verbal: Arguments against adverbial accounts

In this section, I will establish the syntactic category of the lexical item liketa and determine the relationship between liketa, liked to, and their respective complement clauses. I will provide evidence that the forms in question are verbal rather than adverbial.

Adverbs are generally less restricted in their distribution in sentences than verbs are.

-

(15)

Example (15b) shows that almost may appear post-verbally, while (15d) shows that liketa may not.

Adverbs are licit as answers to questions, liketa is not.

-

(16)

Even though liketa and liked to are constrained in the types of aspectual auxiliaries and participle morphology that may appear on either side of them, we can still learn about their syntactic categories by looking at their distributions in a hierarchy of projections. In what follows, I show that neither liketa or liked to pattern with the adverb almost. First, notice in (17a) that liked to may appear between two auxiliary haves.

-

(17)

This is indicative of a bi-clausal structure in which the liked of liked to occupies the position of the matrix verb and to is the head of a TP complement. Example (17b) shows that this position in the sentence is unavailable to the adverb almost.

Second, since liketa does not license the overt embedded auxiliary, comparison with almost reveals a superficially similar distribution.

-

(18)

-

a.

John had liketa (*have) finished his work.

-

b.

John had almost (*have) finished his work.

-

a.

However, we see in (19) that liketa selects for a particular participle form of the embedded verb, while almost does not.

-

(19)

Specifically, liketa selects for the past participle on the verb which appears to its right. This is explicitly visible only when the verb to the right of liketa is passivized and requires auxiliary be. Auxiliary be may only ever appear in the past participle form and never in the simple past. Recall this fact from (7) repeated below.

-

(20)

This fact is extremely important given that this variety of AppE exhibits variation in simple past and past participle verb forms such that virtually all irregular verbs, except auxiliary be, exhibit some type of variation. For example, almost all standard past participle -en verb forms may follow an auxiliary have in AppE marked either for simple past as in ‘John had broke the vase before...’ or even an unmarked form ‘John had eat the bread before...’. Under the common assumption that been is the past participle form of auxiliary be, this is one of the strongest, albeit rare, pieces of evidence that liketa complements involve a head that assigns the past participle in the dialect under discussion.

This data is not consistent with an adverbial analysis for liketa, because adverbs like almost do not commonly select particular tense or aspectual forms of verbs. Moreover, time adverbials that are constrained to certain tense and aspectual contexts do not block subject verb agreement.

-

(21)

-

a.

He always finishes his work.

-

b.

He never finishes his work.

-

c.

He now finishes his work.

-

a.

This means that if liketa were an adverb, we would have to account for the fact that liketa resists appearing with all but participle morphology in its complement.

The facts leave open the possibility that liketa is itself an aspectual auxiliary like be or have,Footnote 6 but this is unlikely because all standard lone finite aspectual auxiliaries in English undergo T to C movement in yes/no questions. Liketa does not.

-

(22)

In fact, liketa can only appear in yes/no questions which are formed with the auxiliary have.

-

(23)

We can capture this fact by assuming that, in accordance with the historical findings from Kytö and Romaine (2005), liketa always occurs with a matrix auxiliary have and is optionally pronounced.

-

(24)

John (has/had) liketa finished your work.

I leave discussion of optionally null have until Sect. 6.1 where I discuss the position of liketa within the larger clause. Nevertheless, I assume that an auxiliary have is always present in the syntax above liketa.

These facts taken together suggest that liketa is verbal even though it appears in distributions similar to almost. As I will argue later in this paper, analyzing liketa as a verb accounts for a broader set of facts in which it is shown to be virtually identical to wanna, the contraction of want to.

Thus liketa is verbal and not adverbial. It cannot appear in multiple locations like many adverbs and it is not a felicitous response to a yes/no question. Further, liked to appears in a verbal position between two auxiliary have heads and even though liketa does not, its unique selectional properties set it apart from adverbs and aspectual auxiliaries.

4 The embedded clause

Having established that liketa and liked to are both basically verbal, we can turn our attention to the embedded clause. I argue that even though they appear to be related by some mechanism of contraction, they select different embedded complements. If they selected the same complements then the alternation between the contracted and non-contracted form might be a purely phonological one. However, as I point out below, there are syntactic differences between the complements associated with the liketa and liked to forms. Any differences in the syntactic behavior of the complements should be accounted for syntactically. Thus, whatever conditions led to the creation of these two forms, I assume that they are separate lexical items with differing selectional restrictions and consequent syntactic effects.

I assume following Feagin (1979), that liketa is the contracted form of liked to and this is parallel to the contraction of wanna from want to. Since wanna has been shown to have features associated with clausal restructuring or clause union (Postal and Pullum 1982; Roberts 1997; Goodall 2006), it is likely that liketa will have those properties as well. Thus identifying liketa as a restructuring predicate is a starting point for analyzing any differences in the complement clauses of liketa and liked to forms and providing a principled account of the relationship between them.

Embedded clauses are traditionally thought of as consisting of CP/TP. However, there is reason to think that this is not always the case based on evidence from a certain class of verbs. The term restructuring describes instances of clausal embedding in which either the embedded or matrix clauseFootnote 7 behave as if they are smaller than usually thought. These smaller than usual clauses are often referred to as having undergone clause union or clause reduction. More specifically, Wurmbrand (2001) argues that restructuring predicates across languages ban complementizers associated with (CP), sentential negation associated with (TP), and tend to describe bare events.

Consider the well known case of auxiliary switch in Italian as mentioned in Roberts (1997) and observed by Rizzi (1982) and Burzio (1986). Keep in mind that the transitive verb voluto requires the auxiliary avere as in (25a). The unaccusative verb venire requires the auxiliary essere. However, in (25b) we see that when voluto takes venire as an infinitival complement either auxiliary is allowed. These examples are taken from Roberts (1997: 433)

-

(25)

The crucial idea is that there is some property of the complement that renders the clause boundary transparent. Note that when the verb voluto appears without an infinitival clause, it cannot select for the auxiliary essere in (25a). However, when voluto appears above venire in (25b) the auxiliaries are allowed to ‘switch’ and either auxiliary is allowed. The requirement that voluto take the auxiliary avere seems to be circumvented by the fact that voluto has selected a complement that contains an unaccusative verb that requires the auxiliary essere. In this sense, the matrix clause containing voluto may share the selectional properties of its complement clause. It seems that the selectional requirement on auxiliaries of the embedded clause is realized in the matrix clause.

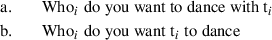

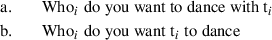

Now consider restructuring in English as exemplified by wanna contraction (Postal and Pullum 1982; Roberts 1997; Goodall 2006). In the uncontracted form shown in (26), wh-movement is licit from either the subject or the object argument position of the embedded clause. However, with wanna in (27) this is not possible. Wh-movement is not licit from the external argument position of the embedded clause.

-

(26)

-

(27)

The analyses contained in Postal and Pullum (1982), Roberts (1997) and Goodall (2006) treat this alternation as if the external argument position is unavailable in wanna contraction.

Thus, in both the case of Italian auxiliary switch and the case of wanna contraction in English, it appears as though their respective complement clauses are behaving as if they are smaller than previously thought or have been unified via some syntactic operation or mechanism.

In this article, I analyze liketa as a restructuring verb. In line with analyses of wanna contraction, the presence or absence of properties associated with CP or TP are what determine a complement’s status as a restructuring clause. Complements with properties demonstrably associated with CP and TP are considered non-restructuring complements. Complements which do not exhibit properties associated with CP and TP are candidates for restructuring effects. Here, I present evidence that liketa differs from liked to in the presence of T. Specifically, liketa does not license infinitival-to or sentential negation from the embedded clause.

Liked to requires infinitival-to while liketa does not allow it. This is important because in most standard theories, infinitival-to in English is associated with T. The absence of infinitival-to is indicative of an absent T.Footnote 8

-

(28)

-

(29)

Further, restructuring predicates in VP fronting and ellipsis contexts should be unacceptable because T in such instances must be overt.Footnote 9 Example (30) shows that this is exactly what we find with liketa contraction and VP fronting cases.

-

(30)

The example in (30a) is acceptable because the second conjunct is a non-restructuring complement and an embedded T is present in the form of infinitival-to. Thus it complies with the overt T requirement of VP fronting. However, liketa in (30b) is unacceptable in the second conjunct because it is a restructuring verb and T is not present. The same logic may be applied to the VP ellipsis cases shown in (30c) and (30d). Finally, example (30e) shows that facts shown in the immediately preceding examples (30c–30d) are not due to a constraint against conjoining liketa and liked to. This is further support for the idea that contracted liketa and uncontracted liked to differ in terms of what complements they take.

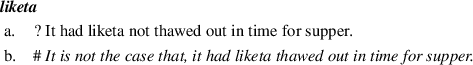

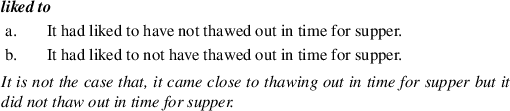

Liked to licenses sentential negation with not, liketa does not. Considering the common assumption that sentential negation with not is parasitic on the presence of T (Zanuttini 1996), this also indicates that T is absent in the structure of contracted liketa. The uncontracted liked to allows sentential negation from its complement. Keep the meaning of liked to in mind. Without the negation associated with not, liked to has the following meaning.

-

(31)

It came close to thawing out in time for dinner but it did not thaw out in time for supper.

The addition of negation in the case of liked to changes the truth value of the entire proposition.

-

(32)

It came close to not thawing out in time for dinner but it did thaw out in time for supper.

Finally, the position of negation with respect to infinitival-to has no effect on the interpretation of negation.

-

(33)

Sentential negation like this is not possible with contracted liketa and in fact negation with not, as shown in (34a), is only marginally acceptable. What is pertinent to the discussion here is that unlike liked to, sentential negation interpretations of not are semantically infelicitous (as indicated by #) embedded under liketa. This is shown in (34b).

-

(34)

You may recall that Feagin observed an instance of negation to the right of contracted liketa yet I have just claimed that it is only marginally acceptable in AppE. Beyond this, one reviewer points out that there are other observations of liketa occurring with negation. According to the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project website page on liketa (Ruffing and McCoy 2015), it may also appear under liketa as didn’t.

-

(35)

I speculate that instances of negation found in these varieties are indicative of micro-variation in the selectional restrictions on liketa’s complement. The differing availability of configurations involving negation between dialects reflect different pathways of grammaticalizationFootnote 10 in the sense of Roberts and Roussou (2003). However, as far as I can tell liketa in AppE of eastern Kentucky selects complements that do not allow negation. I believe the question to ask in those other dialects is not about negation but whether liketa in those dialects is actually a verb. It may in fact be an adverb, an aspectual auxiliary, or a non-restructuring verb all of which may occur in different configurations with respect to negation. I will return to observations about variation in liketa complements after the current analysis.

Minimally, this data shows a difference in properties associated with T in the embedded clauses of liketa and liked to. I argue that liked to is non-restructuring and is maximally headed by TP, while the complements of liketa either do not have a tense phrase or have a tense phrase that has different properties with respect to negation and insertion of infinitival-to.

Considering that liketa and liked to in AppE are both raising predicates because they license expletive subjects as in It had liketa rained and It had liked to have rained, I argue that the structure of liked to is uncontroversial and minimally involves a TP. It is a non-restructuring verb and it selects a standard TP infinitive complement. I will assume it has the following structure.

-

(36)

In this section, I gave a bare sketch of the theory of restructuring that I will use to analyze contracted liketa. I assumed that restructuring verbs select for complements smaller than TP. Then I argued that only contracted liketa has restructuring properties; the uncontracted liked to form is a not a restructuring verb and can be set aside. These facts taken in conjunction with the observation that infinitival contractions superficially seem to involve a type of union across clause boundaries, suggest that a logical starting point for investigation is comparison with wanna contraction. The differences in liketa and liked to clauses are not simply superficial, contracted liketa does not license infinitival-to or sentential negation from inside the embedded complement. Thus, liketa seems to be a restructuring counterpart to liked to. In the next section, I present more evidence for the argument that some infinitival contractions may be thought of as restructuring predicates.

5 Contractions and restructuring complements

Goodall (1991, 2006) argues that infinitival contractionsFootnote 11 like wanna are restructuring predicates; a notion that he attributes to Frantz (1977) and Postal and Pullum (1982). Goodall establishes several parallels between the restructuring process known as clitic climbing in Romance languages and wanna contraction.

-

(37)

(Goodall 2006: 691)

-

a.

The host of contraction is modal or aspectual in nature.

-

b.

The infinitival must be a complement of the host of the contraction.

-

c.

The subject of the matrix and embedded clauses must be co-referential.

-

a.

-

(38)

(Goodall 1991: 240–241)

-

a.

The host of the contraction must be a syntactic verb.

-

b.

Infinitival contraction is not possible with conjoined verbs.

-

c.

Infinitival contraction is not possible with conjoined complements.

-

a.

Liketa and wanna fit the semantic class of verbs that exhibit restructuring effects across languages. Consider the list of ‘core’ restructuring verbs and their corresponding semantic classes, adapted here from (Wurmbrand 2001: 7).

-

(39)

Goodall (2006: 691) goes on to note that plenty of verbal contractions which are arguably contractions of V + to are all either aspectual or modal in terms of their semantics. Consider his list below.

-

(40)

In the remainder of this section, I compare Goodall’s observations about restructuring wanna with liketa. I should mention that Goodall’s work actually compares wanna contraction to clitic-climbing in Romance. I only consider liketa as compared to wanna for reasons of clarity and space. Transitively though, liketa will behave like clitic-climbing if it behaves like wanna contraction. The following examples are adapted from Goodall (1991: 243–248) and all examples involving liketa receive the relevant counterfactual interpretation.

For wanna and liketa, contraction is not possible if the infinitive is not a complement of the verb. This rules out a purely phonological explanation. If the contraction were only phonological, we would expect it to be possible regardless of syntactic context.

-

(41)

Notice that wanna contraction in (41) is not possible with adjunct clauses. Similarly (42) shows that liketa contraction is also only possible when the infinitive is a complement to the verb.

-

(42)

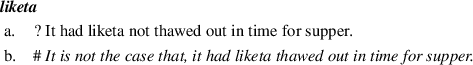

Example (43) shows that extraction of the external argument of the complement under wanna contraction is not possible, presumably because this position must be co-indexed with the external argument of the matrix clause. As shown in (43b), wh-extraction from this site is an example of a strong-crossover effect.Footnote 12

-

(43)

A similar fact holds for liketa in (44). Extraction from the external argument position under liketa is also not possible. This is to be expected given my previous claim that liketa behaves like a raising verb.

-

(44)

It is worth noting that while wanna and liketa pattern together in disallowing the extraction of the external argument of their complement clauses, their respective uncontracted counterparts do not pattern together.

-

(45)

Importantly, this difference is to be expected if (as I assume) uncontracted liked to is a raising verb and want is not. The difference shown in (45) is orthogonal to the comparison of wanna and liketa. It does however tell us that the data in (43) and (44) are not useful for revealing the restructuring status of uncontracted liked to. Because of this, the only positive evidence for the restructuring status of liketa is the sentential negation facts set out in Sect. 4.

As shown in examples (46) and (47), liketa and wanna are unacceptable when conjoined with another verb. The explanation of this fact is found in the differing selectional properties of the verbs. Need selects a non-finite clause which includes infinitival-to but wanna only selects for a bare infinitive. The selectional properties of neither verb can be satisfied via conjunction.

-

(46)

Again, the facts are virtually identical for liketa contraction.

-

(47)

Goodall notes that conjoined complements are also unacceptable in cases of wanna contraction. The same is true of liketa contraction.

-

(48)

-

(49)

Recall that liketa fits the more superficial mold of well behaved restructuring verbs. It is a raising verb with both intensional properties and aspectual constraints. More conclusively however, liketa shares syntactic restrictions and properties with wanna. Those properties and restrictions parallel the more well known restructuring phenomenon of clitic climbing. The non-contracted liked to form does not share those parallels.

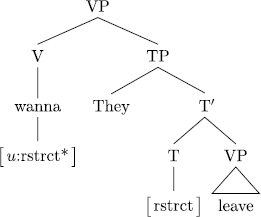

6 Mono-clausal restructuring

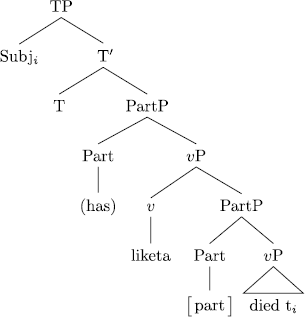

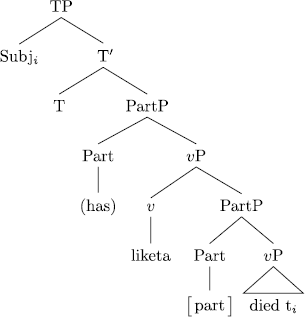

I will use Wurmbrand (2001) and the diagnostics contained there to analyze liketa under the mono-clausal approach to restructuring. Given liketa’s similarities to wanna contraction and its general list of properties, the contracted form is best analyzed as a restructuring verb. In this section, I will use Wurmbrand’s mono-clausal approach to the classification of restructuring verbs in order to provide an analysis of liketa. Once the primary analysis is in place, I will return to the issue of variation in liketa complements. Finally, I briefly sketch an alternative bi-clausal restructuring analysis for liketa and compare the two theories. In what follows, I will argue for the following structure for contracted liketa.

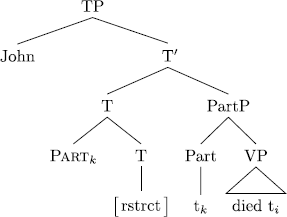

-

(50)

Specifically, I will provide further evidence in accordance with Wurmbrand (2001) that liketa is a restructuring verb generated in v. Then, in accordance with the mono-clausal approach I will argue that liketa selects for complements that are smaller than TP, namely they are maximally headed by the auxiliary phrase which I will refer to as PartP. Next, I will derive the ban on the auxiliary have. In the last bit of analysis, I will address dialectal variation in liketa and compare the current restructuring approach to a bi-clausal head-movement approach.

6.1 Liketa is a restructuring verb generated in v

Recall from Sect. 3 that liketa is verbal and not adverbial. It cannot appear in multiple locations and it is not a felicitous response to a yes/no question. Many adverbs have both of those properties. Further, liked to appears in a verbal position between two auxiliary have heads and even though liketa cannot, its unique selectional properties set it apart from adverbs and aspectual auxiliaries.

Aside from the parallels that I have drawn from Goodall’s observations, liketa contractions exhibit many other properties that we associate with verbs that select for smaller than TP complements. Complements of restructuring verbs do not allow sentential negation associated with T, they never license complementizers, and though they might allow aspectual marking on their verbs, they never show overt tense marking.

According to the mono-clausal approach to restructuring presented in Wurmbrand (2001), restructuring verbs that do not undergo matrix passivization make up a specific class. Wurmbrand argues that this is explained if they are in competition with the passive, thus in v.

-

(51)

-

(52)

-

(53)

Examples (51)–(53) show restructuring verbs in English that do not undergo matrix passivization. Wurmbrand (2001: 215) terms verbs like these semi-functional restructuring predicates. This means that they tend to show a mixture of properties commonly associated with verbs and auxiliaries. Assuming this, let us first locate liketa itself in the matrix clause. Liketa does not undergo matrix passivization.

-

(54)

Liketa patterns with those restructuring verbs in (51) which is consistent with it being semi-functional and not a true restructuring predicate in terms of matrix passivization. However, a reviewer points out that if uncontracted liked to and contracted liketa are both raising verbs, then neither is predicted to undergo matrix passivization. In fact, liked to also does not allow matrix passivization.

-

*

The whiskey had been liked to have drunk.

Thus the unacceptability of matrix passivization in liketa sentences cannot be solely attributed to it originating in little v and so the matrix passivization diagnostic used in Wurmbrand (2001) is not decisive in this case. The question as to whether liketa is V, solely in v, or is inserted as an auxiliary head remains open. I will return the question of whether liketa is a v or V after showing that liketa is not an aspectual auxiliary.

The question of whether or not liketa is an auxiliary can be answered by once again looking at its distribution relative to auxiliary heads. We know from Kytö and Romaine (2005) that liketa is historically found preceded by the auxiliary have. This is still the case in Appalachian English today although the overtness of the matrix auxiliary seems to be optional. Common assumptions about the hierarchy of projections lead us to the conclusion that liketa is as low as v. This is illustrated in (56).

-

(55)

Supporting evidence comes from the fact that liketa occurs below modal auxiliaries.

-

(56)

John might have liketa drunk the whiskey by the time we arrived.

In fact, it seems that auxiliary have is always structurally present and optionally phonologically expressed. There are four pieces of evidence which support this hypothesis. First, auxiliary have may always optionally appear to the left of liketa. Second, question formation is possible only with auxiliary have.

-

(57)

This is in turn supported by the fact that auxiliary have also appears in emphatic contexts where other verbs would take do.

-

(58)

Similarly, when negative not or n’t is used in the clause above liketa, it forces have and not do-support.

-

(59)

Thus, have seems to appear as a type of have-support analogous to do-support. I speculate that have is required and do-support is disallowed in these contexts because have is favorable for counterfactual contexts.Footnote 13 A reviewer points out that the ban on do in y/n question formation might be due to the fact that do requires a bare form of the verb. If this is right, then the y/n question data could be viewed as support for the idea that liketa always requires selection by a higher auxiliary have. These selectional requirements would block do-support in y/n question formation. I take these four facts as evidence for the presence of an auxiliary have in the auxiliary space located above contracted liketa.

In a fully articulated English clause the only other auxiliary head that might be a viable candidate for housing liketa is ProgP which assigns progressive morphology. For reference, I assume the basic functional structure in (61) for Standard English and AppE clauses.

-

(60)

Crucially, liketa never occurs with progressive aspect. Example (62) illustrates this fact for both matrix and embedded clauses.

-

(61)

Given the basic clause structure in (61) and the fact that liketa may never appear with the progressive aspect in (62), the evidence again indicates that liketa is located in v.

If liketa were an auxiliary then we might expect it to undergo auxiliary inversion in yes/no questions. Again, this is not the case. Liketa doesn’t undergo aux-inversion. But as one anonymous reviewer points out, only finite auxiliaries raise to C in subject auxiliary inversion. Thus it follows that, if liketa occurs below auxiliary have as I have suggested, then we should not expect it to invert. Rather, the highest tense bearing auxiliary in the T/Aspect domain would be expected to undergo inversion. This, I assume, is exactly what has occurred when we see have appearing in C in yes/no questions with liketa. Thus, the subject/auxiliary inversion fact alone cannot be taken as evidence that liketa is not an auxiliary. A more refined view is required.

I would argue that the fact that only finite auxiliaries undergo inversion supports the view that liketa is housed just below the auxiliary domain. Many auxiliaries may appear in both tensed and non-tensed contexts in a main clauses. Again, consider progressive be and auxiliary have. If they happen to be the highest auxiliary in a clause, then it is commonly assumed that they end up in T and are viable targets for subject-auxiliary inversion. However, they may also appear embedded under other auxiliaries and we assume that they will not undergo subject-auxiliary inversion. If liketa were an auxiliary like progressive be, or auxiliary have, then it is odd in at least two ways. First, it only appears below have. Second, unlike be and have auxiliaries it is never a possible candidate for inversion by virtue of always occurring below auxiliary have; a situation that sounds more verbal than auxiliary-like. In sum, I argue that the finite/non-finite distinction in subject auxiliary inversion reveals more evidence which separates liketa from aspectual auxiliaries.

Keeping in mind that the passivization facts, while not conclusive, are consistent with semi-functional restructuring predicate status, it still seems that liketa could be base generated as high as v and yet below PartP, as in (56). Following Wurmbrand (2001: 25, 215–223) on semi-functional restructuring predicates, I assume that liketa is an unaccusative predicate housed in v.

The theoretical considerations that lead me to locate liketa in v and not V are as follows. Like lexical verbs, liketa does not undergo subject auxiliary inversion and yet like an auxiliary it also does not assign a theta role. Moreover, the argument structure which is present in liketa sentences stems from the embedded verb.Footnote 14 Then there are the clausal hierarchy facts which show that it occurs below other aspectual auxiliaries in the architecture of the clause. In addition to this, the fact that liketa patterns with wanna as a restructuring predicate suggests that it does not select a CP/TP clause like other main verbs in V (a fact which sets it apart from uncontracted like to). So all traditional reasons for the categorization of something as a verb either do not hold or are not required. Still, there is precedent for one high verbal category, unaccusative v, which satisfies all of the descriptive facts surrounding liketa. As an unaccusative v, liketa would not license external arguments of its own, assign a theta role, or introduce its own argument structure.Footnote 15 An unaccusative v liketa could also be selected for by a higher have auxiliary and would not be predicted to undergo subject auxiliary inversion.

In this section, I have argued that liketa is a restructuring verb generated in v based on independent grammatical properties shared by both Standard and Appalachian English, in the spirit of Wurmbrand (2001).

6.2 Complements of liketa are headed by PartP

As argued in previous sections, the morphology that appears on the verb in liketa’s complement is the past participle. So, I contend that clauses embedded under liketa are headed by auxiliary phrases which license that morphology. Further evidence that PartP heads the embedded predicate is shown in passivized liketa complements. The example below in (63a) shows the participle form of passive auxiliary be under liketa and above the embedded verb. In example (63b) we see that the past participle morphology on be is required. Lastly, example (63c) shows that the be of the infinitival passive is also unacceptable.

-

(62)

The acceptable case shows that the be head of PassiveP may only appear as been, the commonly assumed past participle form of the passive auxiliary be. It is the PassiveP head been which is responsible for marking the verb below it for the passive participle. One could argue that this is simply showing that a high auxiliary have is required in all cases to mark the auxiliary be for past participle morphology in its own clause. If this were the case then it is not clear why removing auxiliary had does not result in the acceptability of a be passives in (64b) and (64c).

-

(63)

However, given that I assume AppE allows null have to the left of liketa, this point needs further clarification. If the structure is truly mono-clausal, it might not be implausible for the T or null have to the left of liketa to be licensing the morphology on the right of liketa. I argue that this situation is ruled out if liketa is verbal. In short, only liketa will enter into an agreement relationship with auxiliaries to its left. Later, I will argue that wanna does not. The details of this and a comparison with wanna are below.

In sum, I argued that liketa complements lack a tense phrase and are maximally headed by a past participle phrase which we see the effects of even though it is banned as a stand-alone lexical item.

6.3 Deriving the ban on the embedded auxiliary have

Reconsider the data from the introduction. It illustrates the ban on overt auxiliary have in the complement of liketa clauses; an interesting and unexpected fact given the acceptability of an overt auxiliary have in the uncontracted form.

-

(64)

The ban on embedded have under liketa is explainable under current assumptions only if we adopt a particular view of auxiliary licensing. Specifically, I propose that auxiliary insertion is the result of agreement with a higher auxiliary head. Under this account, the auxiliary head is still responsible for licensing aspectual morphology on lower heads but its own realization as a lexical auxiliary is dependent on the presence of and agreement with a higher T/Aux head. Thus, under the approach and assumptions presented in this section, the ban is predicted as there is no evidence for T in the embedded clause. In this sense, liketa completes a paradigm found with other restructuring verbs where morphology may be licensed in the embedded clause though the corresponding auxiliaries for that morphology need not be overt.

-

(65)

The examples in (66a) and (66b) show that progressive morphology is licensed in the complement of causative have and perception complements without progressive be. Likewise, the complements in (66c) and (66d) exhibit passive morphology in the absence of passive be. Finally, liketa in (66e) completes the paradigm by licensing past participle morphology in the absence of auxiliary have.

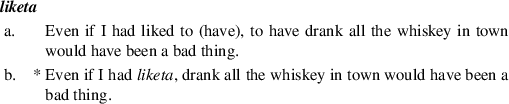

However, not all restructuring verbs exhibit the same restrictions on auxiliary licensing. Notice that in the following sentence, contracted wanna does seem to somehow license an embedded auxiliary. This is surprising given the fact that there is no more evidence for an embedded T head under wanna contraction than under liketa.

-

(66)

I wanna have eaten before you arrive.

In order to maintain our assumptions about mono-clausal restructuring, the ban on auxiliary have under liketa, and the view of auxiliary licensing presented here, we are forced to say that auxiliary have in (67) is licensed by a higher interpretable inflection feature. In example (68) below, I propose that it is licensed by an infinitive inflectional feature on wanna itself.

-

(67)

The agreement relations in (68) are as follows. The uninterpretable inflection feature on the verb eat is satisfied by the past participle feature of the auxiliary head. The uninterpretable inflection feature of the past participle head is only satisfiable by the interpretable inflection feature on wanna. This is a plausible state of affairs because wanna never exhibits agreement and is incompatible with morphology assigning heads. Note that as we have seen liketa does not share all of these restrictions.

-

(68)

This is not just a semantic restriction because wanna is compatible with those contexts if agreement is handled elsewhere or the heads also assign infinitival inflectional morphology to lower heads commensurate with wanna’s bare form.

-

(69)

Finally, auxiliary have under liketa is not licensed because of locality conditions on Agree and intervention effects (Chomsky 2001), where intervention is formalized in (71).

-

(70)

If probe P matches inactive K that is closer to P than matching M, this bars agree (P,M).

This is demonstrated in the following structure where the uninterpretable inflection feature on the lower auxiliary is barred from receiving interpretable inflection from a higher tense or auxiliary head because liketa in this case is an intervener.

-

(71)

Let’s begin with the derivation of the lower auxiliary head and the verb died. I follow common assumptions and assume that die has head moved to v. Though these steps are not shown in the tree, at this point the verb die would still have its own uninterpretable inflectional feature to be satisfied. Next, we merge the lower auxiliary head Part, which contains an interpretable past participle feature that satisfies the uninterpretable inflectional feature on die resulting in the participle form died. I assume features become inactive after valuation, thus the past participle feature on the lower auxiliary head is not able to satisfy the uninterpretable inflectional features of any other head in the derivation.

The crucial point for the discussion about example (72) is the point of merger of the higher auxiliary or past participle head. After the auxiliary head merges to the vP headed by liketa, the uninterpretable past participle feature on liketa will establish an agree relation with the higher participle head and be valued for past participle. Again, the past participle features of this higher auxiliary and liketa are rendered inactive for further operations. Thus the lower past participle head is left with no interpretable inflection. Then we only have to assume that a default morphological rule for uninflected auxiliary heads inserts a null auxiliary form on the lower Part head. This leaves us with the proposed structure in (50) repeated as (73) below.

-

(72)

Deriving the ban on the auxiliary have under liketa while also accounting for the presence of that auxiliary with wanna contraction requires a particular view of auxiliary licensing. Specifically, I made the claim that auxiliaries are only inserted if they agree with some higher T/Aux head which assigns morphology. This is especially important if we want to maintain what I consider the rather economical assumptions about clause structure made in Wurmbrand’s mono-clausal approach to restructuring. The difference between wanna and liketa clauses can then be explained in terms of intervention effects on auxiliary licensing. I now turn to explaining some of the variation that is found in liketa for other grammars.

6.4 Other varieties of liketa

This analysis presents one grammar of liketa that happens to be accessible to the author and informants in eastern Kentucky. It is important to keep in mind that ultimately, it is one grammar of liketa among many. In this spirit, I will briefly outline just how data generated by other grammars of liketa can be accounted for while maintaining the current analysis.

Recall the following data from Feagin and from the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project website:

-

(73)

-

(74)

Under the current account, liketa in these varieties must receive a slightly different analysis. Though there are several possibilities that we might consider, all are dependent on our assumptions about the syntactic category of liketa in each variety. Assume the data in (74) represents one grammar and the data in (75) represents another. For either grammar, it is possible that liketa has been grammaticalized as either an adverb, an auxiliary, a restructuring verb with a syntax akin to wanna, or a non-restructuring verb. I do not assume that either grammar is identical to the grammar of liketa in AppE. I examine the data from these alternate grammars to determine the syntactic category of liketa in these dialects in accordance with the analysis here. This will reveal a sketch of plausible options for each grammar and outline a particular set of predictions and questions for future research.

Under the analysis of auxiliary insertion presented here, the Alabama English data in (74) indicates that auxiliary have insertion is being licensed via agreement with some higher T/Auxiliary head. This is compatible with analyses which identify liketa as either an adverb, an auxiliary, as something akin to wanna in the previous section, or as a non-restructuring verb (listed as -rstrct in the example below). Liketa in these cases, would not constitute an intervener. That is, it would not contribute the necessary configuration of features to prevent auxiliary insertion. For simplicity, I am assuming that the contraction of auxiliary have would be subsumed by an analysis which accounts for the full auxiliary. Consider the data below where feature agreement is shown abstractly via co-indexation:

-

(75)

Example (76a) explicitly shows how adverbial liketa would have virtually nothing to do with feature agreement between the auxiliary and verbal heads; this is similar to the behavior of almost. Although, if liketa is an adverb in such grammars, it is not clear why auxiliary have appears in bare form with the pronoun she which requires the present has or simple past had. Example (76b) shows how an aspectual auxiliary version of liketa might simultaneously agree with T for tense and with auxiliary have below it for an unmarked form. Example (76c) depicts liketa being akin to wanna as analyzed in the preceding section. By hypothesis, liketa would not carry agreement features and would not interrupt feature valuation between T and auxiliary have. However, the liketa as wanna hypothesis predicts no restrictions on aspectual auxiliaries below it. This means there should not be a restriction on the morphology of the verb below liketa. Feagin observed otherwise. Lastly, (76d) illustrates liketa as a non-restructuring verb similar to the uncontracted liked to form. This analysis would require evidence of an embedded TP minimally, and a subsequent explanation for the lack of complementizers and/or infinitival-to. Given the limited data at hand, I must tentatively forward the aspectual auxiliary analysis for liketa in Alabama English.

A final question about the Alabama English data revolves around the interpretation of not in (74c). I simply do not know how speakers of Alabama English interpret not there. I only know that for speakers like myself, such examples are only marginally acceptable and the meaning, though unclear, can not be one of sentential negation. If it is interpretable for Alabama English speakers as sentential negation then, we kill the non-restructuring hypothesis because not is parasitic on overt T and the only candidate element in the sentence is liketa. This would confirm the aspectual auxiliary hypothesis assuming liketa is in a T or Auxiliary head. On the other hand, not in (74c) as constituent negation is unrevealing.

Given that one of the core assumptions made about restructuring verbs in this paper is that they select for smaller than TP complements, the account of auxiliary insertion proposed here precludes an AppE style restructuring account for liketa in Alabama English. However, if we examine Alabama English liketa using the same framework of diagnostics and assumptions about clausal architecture, it is analyzable as an aspectual auxiliary which occurs in a single clause above auxiliary have but below T. Of course it remains to be seen how well liketa in Alabama English patterns with other aspectual auxiliaries in terms of the wider list of properties that make up the class. I leave this question to further research.

Similar reasoning may be brought to bear on the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project data involving didn’t, repeated below.

-

(76)

I liketa didn’t make it! (Ruffing and McCoy 2015)

If didn’t is interpretable as sentential negation, then this variety of liketa is plausibly an adverb in a single clause adjoined in or above T. If it were an aspectual auxiliary it would have to be merged rather high. This would require that this particular liketa is located above T, unlike other aspectual auxiliaries. Further, it cannot be analyzed as being akin to wanna if didn’t here is sentential negation because it is banned in restructuring complements. Finally, we might analyze it as being a non-restructuring verb like the uncontracted liked to form. However, then we have to explain why liketa in this case is able to select only past as opposed to past participle morphology. It only seems plausible given the limited amount of data that this liketa is an adverb.

Liketa in AppE of eastern Kentucky is analyzable as a restructuring verb similar but not identical to wanna. Though the two differ minimally, they both exhibit restructuring properties. That is they both appear to be verbal elements which select for smaller than TP clauses. I have also argued that liketa is generated in v. Further, liketa selects smaller than TP complements maximally headed by an auxiliary PartP which assigns participle morphology to the embedded verb or passive auxiliary. These assumptions force a particular view of participle assignment and auxiliary insertion. Recall that, liketa allows the past participle to be assigned to verbs beneath it even though the associated auxiliary head is banned from appearing. These assumptions taken together require a slightly different analysis of wanna which does license auxiliary insertion beneath it; what I termed ‘exceptional’ auxiliary licensing. Without further analysis, I can only speculate that wanna is perhaps in a different stage of grammaticalization, up and leftward into the English auxiliary system. Such a view is in accordance with minimalist views of grammaticalization (see Roberts and Roussou 2003). Finally, I described how variation observed in previous studies of liketa in other dialects may be folded into the current analysis but again, further research is necessary. In the remainder of this section, I compare a different approach to restructuring to the account assumed so far.

6.5 Mono-clausal vs. bi-clausal approaches

Wurmbrand (2001: 9–10) notes that although the mono-clausal approach does not require any external mechanism of restructuring such as head-movement, it complicates the general typology of possible clauses selected for by various restructuring verbs. Here, I add to the discussion by providing an alternate analysis of the same facts for comparison of the assumptions and consequences involved in each theory of restructuring.

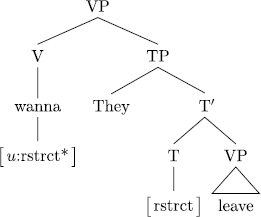

Roberts (1997) argues for a bi-clausal head-movement driven account of wanna contraction in English. The data is repeated in (78).

-

(77)

-

a.

They want to leave.

-

b.

They wanna leave.

-

a.

In the next few paragraphs, I will discuss the relevant pieces of Roberts’ analysis of wanna contraction. I will then show that such an account is directly extendable to liketa. I will also discuss the repercussions that Roberts’ account has for an explanation of the ban on the embedded auxiliary have in contracted liketa forms. A proper treatment of all facets and properties of wanna is beyond the scope of this work, see (Pullum 1997; Roberts 1997; Goodall 2006) for an overview of the issues.

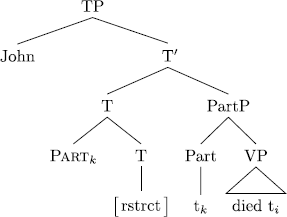

Roberts (1997: 453–454) accounts for the lack of an independent infinitival-to in these contractions directly. He argues that wanna is a separate lexical item which is subcategorized to select for a bare T which precludes overt realization of infinitival-to. He also suggests that verbs like wanna contain a phonological affix (-a in this case) which is a morphologically attached feature that triggers restructuring. The movement itself is driven by another assumption that verbs like wanna have no thematic structure of their own and so must raise the T below them via head movement (Roberts 1997: 430, 453). Thus the embedded T head moves to the matrix verb.

Beginning with merge of matrix V, wanna is added.Footnote 16

-

(78)

Notice that the embedded non-finite T has an interpretable restructuring feature and is phonologically null. Also note that wanna has been merged and comes from the lexicon with a strong uninterpretable restructuring feature.

As shown in (80), this will trigger movement of the embedded T to matrix V by requiring feature checking in a local spec-head relationship.

-

(79)

This strong feature is a brute force instantiation of Roberts’ claim that restructuring verbs like wanna lack argument structure and must be satisfied by other syntactic objects like T.

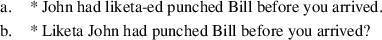

6.5.1 A bi-clausal head-movement analysis of liketa

We can extend Roberts’ analysis to liketa with minimal modifications. Just as Roberts operationalized the descriptive fact that wanna selects a bare infinitive by positing a restructuring feature on the -a suffix on wanna, we can make a similar move. First, liketa selects a bare past participle infinitive. That is, an infinitival complement where both the T and Part heads are precluded from allowing the realization of infinitival-to or auxiliary have. Second, the verb in the bare past participle complement must be overtly marked with participle morphology. The bare infinitive requirement and the participle morphology requirement can be operationalized as Roberts’ restructuring feature and an additional past participle feature on liketa. The ban on the auxiliary have will then fall out analogously to the ban on infinitival-to if both of these features are strong and uninterpretable.

It will not do to have a strong uninterpretable restructuring feature which triggers movement and a weak uninterpretable past participle feature which is valued by agreement in a non-local fashion. This strong/weak feature configuration would predict that an embedded auxiliary have is available when in fact it is not.

If we also assume that satisfaction of strong features must take place as soon as possible then the quickest way to achieve this is to move both goals at once. Thus, any T selected by liketa must have both features. The idea is that, the uninterpretable restructuring feature on liketa will trigger head movement as soon as its probe values its features against its interpretable counterpart. At this point the strong uninterpretable past participle features must be satisfied as well. Consider the derivation of the embedded clause in John liketa died where Part has already undergone head movement and adjoined to T.

-

(80)

This partial derivation shows the head movement of the past participle head to embedded T where the past participle and restructuring feature will be simultaneously visible to the probe from matrix V in order for the derivation to converge. While it is hard to motivate the movement of Part to T in this case, I would stipulate that it moves to the restructuring T in the same way that lone auxiliaries seem to move to T in matrix clauses.

Next in (82), liketa is added. Notice that it contains strong uninterpretable features which are required to be satisfied via a local relationship in the next operation lest they crash the derivation. Having undergone a previous head movement, all necessary features on non-finite T are in a position to be checked.

-

(81)

The strong uninterpretable features on the verb will probe down the tree and be satisfied simultaneously by T. This is shown in (83).

-

(82)

This is how liketa may be analyzed as having an almost identical derivation to wanna contraction assuming a head movement style analysis of restructuring. The final derivation shows how we might simultaneously get the required past participle morphology on the embedded verb, ban the insertion of the auxiliary have, and account for the fact that T seems to be non-existent in restructuring liketa complements. The past participle morphology appears on the embedded verb because there was a participle head there to assign it. The presence of infinitival-to and the auxiliary have are banned only if we assume that liketa is specified for a strong uninterpretable past participle feature as well as a restructuring feature to trigger movement. It also shows why wanna contraction does not bar auxiliary have in (84a). This is reflected by the fact that, the past participle head is not ‘rolled up’ with T via a previous head movement operation because wanna is not required to select a past participle infinitive complement and does therefore not have a strong uninterpretable past participle feature. Example (84b) shows that wanna does not select for a past participle infinitive. If it did, we would expect the appearance of participle morphology on the verb in the absence of the overt auxiliary in (84b) to be acceptable.

-

(83)

The bi-clausal account requires that liketa have somewhat special features that make it possible for the verb to ‘trigger’ restructuring via head-movement. Further, the idiosyncratic aspectual requirements of liketa must also be built directly into the restructuring verb as well. This in turn requires either some further instance of head movement of Part to T in the embedded clause or some other combination of assumptions which put features of the past participle on T while simultaneously preventing auxiliary insertion. On the other hand, the mono-clausal approach only requires c-selectional features and not special restructuring features. The special aspectual requirements of liketa then fall out of those c-selectional requirements. The ban on the inserted auxiliary falls out of the assumption that insertion is only licensed by an agreement relationship from a higher T/Aux head which assigns morphology. A fact which independently explains the behavior of other restructuring verbs whose complements exhibit verbal morphology in the absence of an overt auxiliary. Finally, the comparison with wanna contractions suggests that restructuring verbs may come in various stages of grammaticalization which means that they may bear certain verbal inflection features to varying degrees. Thus assuming a mono-clausal approach with respect to other restructuring contractions might be one way to further illuminate their individual agreement properties and relations to other elements in the structure.

7 Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that liketa in the Appalachian English of eastern Kentucky, is best analyzed as a verb. Further, identification of liketa as a restructuring verb allows for an analysis which helps to explain the properties of both the restructuring and non-restructuring forms of the verb, much like previous restructuring analyses of wanna contraction. The particular properties that liketa and wanna contraction share and do not share make a comparison of the two forms interesting for theories of restructuring. By providing an analysis of liketa in two different theories of restructuring, we compare the relative strengths and weaknesses of each theory. The bi-clausal head movement analysis of liketa is able to capture the phenomena but does not allow us to make any predictions about why the ban on the auxiliary should exist, at least not in any interesting way. On the other hand the analysis of liketa in terms of mono-clausal restructuring suggests that auxiliary insertion in embedded clauses of restructuring verbs proceeds in a certain way. Namely, auxiliary heads license morphology below them, while auxiliary insertion is the result of agreement with a higher morphology-assigning auxiliary head. This in turn makes predictions for other restructuring verbs in English which also have peculiar aspectual requirements associated with their embedded clauses.

Notes

The author of this work is from Jonancy.

For example, when build is modified by almost as in ‘John almost built a chair,’ there are 3 possible interpretations (Rapp and von Stechow 1999). There is (i) a counterfactual interpretation where the agent almost initiates an action which causes a change of state, (ii) a scalar interpretation where the agent initiates an action which almost causes a change of state, and (iii) a resultative interpretation where an agent initiates an action which causes something to almost change states. Liketa does not license a resultative interpretation shown in (1c).

-

(1)

In this way, liketa has only a subset of the three reported interpretations that almost has.

-

(1)

The primary corpus contained 36 interviews of at least 60 minutes in length, while the remainder were 16 interviews of at least 30 minutes in length which were of lesser quality (Wolfram and Christian 1976: 10–12).

The corpus that Feagin created consisted of 85 recorded interviews ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 hours.

According to my and other native speaker judgments liketa may appear in an embedded clause.

-

(1)

This seems to have no bearing on the current analysis. Rather, I would speculate that it is also at least possible in the grammar of Wolfram and Christian’s AppE speakers but simply has a low frequency of occurrence.

-

(1)

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, there may be a connection between liketa in AppE and other non-standard aspectual constructions like aspectual done (see Green 1993; Feagin 1979). As I understand the phenomenon in African American Vernacular English, Alabama English, and Appalachian English, there is nothing which precludes done from being analyzed in much the same way as I will analyze liketa; as a restructuring predicate in the spirit of Wurmbrand (2001). The details would of course have to be worked out, but consider the following state of affairs. According to Green, aspectual done is base generated in an AspP which appears below AuxP and above VP in the clausal architecture of the phrase. Aspectual predicates appearing in this exact position are identified as a sub-type of restructuring predicates by Wurmbrand. I leave an attempt at a fully detailed synthesis of these facts to further research.

Johnson (2014) argues that there are smaller than usual matrix clauses as exemplified by non-finite usages of how come as in “How come them to leave.”

A reviewer points out that the fact that infinitival-to is missing is also compatible with a view that the tense of the clause is finite, specifically past. I would like to point out that while that may be true in some cases, it is not necessarily true in all cases. Consider the following data with wanna.

-

(1)

This example shows that infinitival-to is not possible in wanna constructions and that past interpretations are not possible. Further, we will see later that sentential negation which is associated with T is also not allowed in liketa complements.

-

(1)

Roberts and Roussou (2003: 2) argue that grammaticalization is, in effect, parameter setting that results from the reanalysis of either functional or lexical material.

Following Goodall, I will continue to use the term contraction here because a majority of the literature refers to the difference between ‘want to’ and ‘wanna’ as wanna contraction. I don’t intend to make any claims about how elements come to be contracted.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for clarifying this point.

There is a connection documented in the literature between past/participle morphology and counterfactuality or irrealis mood (Steele 1975; Givón 1994; Iatridou 2000; Palmer 2001; Matthewson 2006). Though this connection is beyond the scope of the current work, it would seem that the requirements of liketa are another instance in which we can see that either the auxiliary head or the participle morphology it assigns is associated with a counterfactual interpretation.

While it is true that the argument structure in liked to sentences is also dependent on its complement because it is a raising verb, the possibility of embedding sentential negation in such structures hints at the presence and selection of a TP complement. TPs are commonly thought to be selected for by V directly or by C.

A reviewer asks why liketa is in v, since many theories assume that v’s sole function is accusative case and theta role assignment associated with external arguments. The reviewer also notes that the ban on auxiliary have under liketa would be accounted for if we assume that liketa is instead housed in a low aspectual projection above v. First, there is precedent in the literature for assuming an unaccusative v. I assume that v is roughly voiceP argued for in Kratzer (1996). Kratzer argues that voiceP may be essentially unaccusative and still carry tense and aspectual information (Kratzer 1996: 123–124). More importantly, while putting liketa in a higher aspectual projection might more easily account for the ban on have in its compliment, it would not account for the fact that liketa and wanna behave similarly with respect to restructuring diagnostics and differ with respect to the presence or absence of auxiliary have; a fact which I deal with in Sect. 6.3.

I assume wanna is a V here so I don’t color Roberts’ analysis with my own assumptions.

References

Burzio, Luigi. 1986. Italian syntax: A government-binding approach, Vol. 1. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Feagin, Crawford. 1979. Variation and change in Alabama English: A sociolinguistic study of the white community. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Frantz, Donald. 1977. A new view of to-contraction. In Work papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, Vol. 21, 71–76. Grand Forks: University of North Dakota.

Givón, Talmy. 1994. Irrealis and the subjunctive. Studies in Language 18 (2): 265–337.

Goodall, Grant. 1991. Wanna-contraction as restructuring. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S.-Y. Kuroda, eds. S. Y. Kuroda, Carol P. Georgopoulos, and Roberta L. Ishihara, 239–254. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Goodall, Grant. 2006. Contraction. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk C. van Riemsdijk, Vol. 19, 688–703. Malden: Wiley–Blackwell.

Green, Lisa J. 1993. Topics in African American English: The verb system analysis. Ph.D. diss., University of Massachusetts.

Iatridou, Sabine. 2000. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (2): 231–270.

Johnson, Greg. 2013. Liketa is not almost. In 36th annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium (PLC), Vol. 19.1. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics.

Johnson, Greg. 2014. Restructuring and infinitives: The view from Appalachia. Ph.D. diss., Michigan State University.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Springer.