Abstract

Korean subject honorification and Korean negation have both affixal and suppletive exponents. In addition, Korean negation has a periphrastic realization involving an auxiliary verb. By examining their interaction, we motivate several hypotheses concerning locality constraints on the conditioning of suppletion and the insertion of dissociated morphemes (‘node-sprouting’). At the same time, we come to a better understanding of the nature of Korean subject honorification. We show that Korean honorific morphemes are ‘dissociated’ or ‘sprouted,’ i.e., introduced by morphosyntactic rule in accordance with morphological well-formedness constraints, like many other agreement morphemes. We argue that the conditioning domain for node-sprouting is the syntactic phase. In contrast, our data suggest that the conditioning domain for suppletion is the complex X0, as proposed by Bobaljik (2012). We show that the ‘spanning’ hypotheses concerning exponence (Merchant 2015; Svenonius 2012), the ‘linear adjacency’ hypotheses (Embick 2010), and ‘accessibility domain’ hypothesis (Moskal 2014, 2015a, 2015b; Moskal and Smith 2016) make incorrect predictions for Korean suppletion. Finally, we argue that competition between honorific and negative suppletive exponents reveals a root-outwards effect in allomorphic conditioning, supporting the idea that insertion of vocabulary items proceeds root-outwards (Bobaljik 2000).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Distributed Morphology (DM) model of the morphology-syntax interface has posited several distinct constructs to account for the idiosyncratic character of morphological phenomena. An important strand of research has addressed the interaction of these constructs. One leading idea is that locality restrictions derived from syntactic structure play an important role in constraining rule application (Arad 2003, 2005; Bobaljik 2012; Embick 2003, 2010; Marantz 2013; Merchant 2015; Moskal 2014, 2015a, 2015b; a.o.). For each morphological operation, it is important to establish what its locality domain is and the point in the derivation at which it applies. Using the empirical domain of Korean subject honorification and negation as our lens, we elucidate the nature of two such operations: dissociated morpheme insertion (re-christened ‘node-sprouting’) and morphologically conditioned vocabulary insertion. We argue that node-sprouting rules apply locally once per phase, as an early step after Spell-Out. To derive the realization of suppletive Korean verbs, we show it is necessary to allow conditioning by hierarchically and linearly nonlocal nodes within a complex X0 head, contra, e.g., Embick (2010), Merchant (2015), Moskal (2014, 2015a, 2015b), Svenonius (2012). Of extant proposals, Korean honorific and negative suppletion is only consistent with the X0 conditioning domain restriction posited in Bobaljik (2012). However, hierarchical locality is nonetheless relevant for vocabulary insertion, because we demonstrate that if two vocabulary items with equivalently complex conditioning specifications compete with each other, the item with the more local conditioning context wins.

En route, we draw several conclusions regarding Korean subject honorification. We argue that verbal subject honorification is syntactically governed grammatical agreement with the honorified NP, with Ahn (2002), Ahn and Yoon (1989), Chung (2009), Koopman (2005), Yun (1993), among others. Although the pattern is syntactically governed, we argue that it is morphologically implemented, rather than adopting the purely syntactic approaches of previous studies. This is motivated by the fact that subject honorification can be realized both low and high in the syntactic structure. We show that most counterexamples to an agreement approach—sentences in which verbal subject honorification appears in the absence of an honorific subject NP—can be explained by the availability within Korean of the syntactic process of possessor-raising to subject position, which we argue applies ‘covertly’ in these cases.Footnote 1 We also provide arguments that Korean suppletive verbs are truly suppletive, rather than distinct semantically related lexical items, contra Bobaljik (2012) and Moskal (2015b).

In the remainder of this section we briefly introduce the mechanisms of interest, namely node-sprouting (aka dissociated morpheme insertion) and vocabulary item competition (aka morphologically conditioned allomorphy), and review previous proposals concerning locality domains for vocabulary item conditioning. In Sect. 2, we then turn to regular Korean subject honorification, first arguing that it should be treated as syntactically conditioned but morphologically implemented agreement. In Sect. 3, with our structural proposal in place, we consider suppletive exponence of honorification and short-form negation, showing that the structural locality of the conditioning feature determines the choice of suppletive exponent, and arguing against both linear and structural adjacency constraints on suppletive conditioning. In Sect. 4, we show that the within-X0 locality constraint on suppletion correctly predicts the suppletive pattern in restructuring serial verb constructions (‘po-constructions’), and motivates a reanalysis of suppletive honorific exponents as monomorphemic, as well as further refuting alternative theories of locality constraints on suppletion.

1.1 Dissociated morpheme insertion and conditioned vocabulary insertion

First we briefly introduce dissociated morpheme insertion and conditioned vocabulary insertion, and situate them within a DM derivation.

Dissociated morpheme insertion, which we will call ‘node-sprouting’ here (suggested by Marantz p.c.), occurs when the syntax outputs a syntactically well-formed structure that is nonetheless morphologically deficient, and the morphological component repairs the deficiency by inserting an additional morpheme, or terminal node, in the representation (Embick 2000; Halle and Marantz 1993). Bobaljik’s (1994) treatment of English do-insertion provides an illustration.Footnote 2 When syntactic T0-to-C0 movement in English results in a structure in which the T0 node is not structurally local to a verb that could support its realization, a node-sprouting rule adds a verbal terminal node to the structure, realized as a form of ‘do’. This is illustrated for Does John go? in (1) below.

-

(1)

Does John go?

Morphological agreement in DM has long been analyzed as such a dissociated morpheme (Halle and Marantz 1993; Bobaljik 2008, a.o.). Sprouted Agr0 nodes are inserted according to language-specific sprouting rules, and are subsequently realized by agreement markers. The rules are triggered by particular morphosyntactic configurations, and hence are syntax-dependent, but they are not part of the syntactic computation. They are hence LF-neutral, as noted by Chomsky (1995). Similarly, the interpretation of the English past tense is not affected by whether it is affixal to the main verb or affixal to the sprouted morpheme vDO0; the application of do-insertion is also LF-neutral. We argue that Korean subject honorification morphemes are normal agreement, and should therefore be analyzed as sprouted nodes.

Vocabulary Insertion is the ‘realization’ of abstract nodes (sprouted or otherwise) by phonological material, which is specified in a list of ‘Vocabulary Items’ that provide the forms available for use in a language. DM adopts the key insight of the Elsewhere Condition (Kiparsky 1973), according to which multiple forms can be eligible to realize a given morpheme, and the winning form is the single compatible form which is most highly specified. To continue with our English past tense example, in the structural context in (2a) below, both the vocabulary items /d/ and /t/ in (2b) are eligible to realize the T0 terminal node, but /t/ wins, because it is more highly specified.

-

(2)

-

a.

[

LEND v0]\(_{v^{0}}\) T0[+past]]\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\)

LEND v0]\(_{v^{0}}\) T0[+past]]\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\) -

b.

Vocabulary items:

T0[+past] ↔ t / [{

LEND,

LEND,  BEND,

BEND,  FEEL,…} ___ ]

FEEL,…} ___ ]T0[+past] ↔ d / elsewhere

-

a.

Competition between distinct vocabulary items is central to all morphologically conditioned allomorphy in DM, as it is for most morphological theories. Some DM literature has been devoted to resolving competitions in which the Elsewhere Condition is insufficient to determine a single winner (Harley 1994; Noyer 1992, 1997); more recently, there has been investigation of locality constraints on conditioning contexts (Bobaljik 2012; Embick 2010; Merchant 2015; a.o.). It seems clear that features several clauses away cannot condition an allomorph, but what exactly the structural constraints are remains a hotly debated topic.

In our analysis, suffixal honorification is implemented by node-sprouting, and suppletive honorification is a case of conditioned allomorphy. We argue that these two operations are subject to distinct locality constraints. Node-sprouting applies once in each cycle of the syntactic derivation, after Spell-Out of a phase. The featural conditioning of suppletive honorification is constrained by a distinct locality domain, the complex X0 head.

We next briefly describe five recent proposals concerning locality constraints on conditioned allomorphy, drawing heavily on Merchant’s (2015) overview.

1.2 Theories of locality effects in morphologically conditioned allomorphy

In morphologically conditioned allomorphy, the correct choice of vocabulary item for one node often depends on the features in another node, which is why conditioned allomorphs give the appearance of ‘secondary’ or ‘multiple’ exponence (cf. Caballero and Harris 2012). For example, in the comparative form better, the choice of stem allomorph for  GOOD, bett-, is conditioned by the [+comparative] feature on the degree node, itself realized by the suffix -er. Recent work has asked when such secondary conditioning is possible. Are there limits on how local a conditioning feature has to be?

GOOD, bett-, is conditioned by the [+comparative] feature on the degree node, itself realized by the suffix -er. Recent work has asked when such secondary conditioning is possible. Are there limits on how local a conditioning feature has to be?

There have been several proposals. Arad (2003, 2005) suggests that morphologically conditioned allomorphs of a nominalizing n0 head must be sisters to the conditioning root node; intervening categorizing head blocks allomorphy. Harley (1995, 2008) also argues along these lines with regard to Japanese causative morphology, and many other proposals build on this idea (Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 2008; Jackson 2005; Svenonius 2005; a.o.). Although sisterhood is clearly sufficient to license morphologically conditioned allomorphy, the example of the English past tense in (2) above shows that sisterhood is not necessary, since the conditioned T0 head is sister to v0, rather than to the conditioning  node.

node.

Embick (2010) argues that linear adjacency is a crucial locality consideration in morphologically conditioned allomorphy. There can be structurally intervening material, iff it is null; Embick proposes that null nodes are ‘pruned’ during the course of the derivation, and hence do not interfere with conditioning. Overtly realized linearly intervening morphemes do block conditioning, however.

Merchant (2015) shows that Embick’s Node Adjacency Hypothesis is too strong, since some Greek verb insertion is conditioned both by features of Voice0 and features of Aspect0, which is not adjacent to the root. He suggests instead the ‘Span Adjacency Hypothesis,’ which holds that allomorphy can be conditioned only by an adjacent span of nodes. In the diagram below, e.g., the exponence of N01 could be conditioned by N02 or by N02 + N03 together, since they constitute a ‘span,’ but the exponence of N01 could not be conditioned by N03 to the exclusion of N02, since N03 is not part of an adjacent span to N01.

-

(3)

Other locality domains have also been suggested. Bobaljik (2012) argues that the upward bound for morphological conditioning of allomorphy is the complex X0, and that allomorph selection cannot be conditioned across an XP boundary. He proposes the ‘Root Suppletion Condition’ schematized in (4) (2012:13), which permits conditioning of α by β across a (word-internal) X0 boundary (4a) but bans conditioning of α by β across a phrasal boundary (4b):

-

(4)

-

a.

α … ]\(_{\mathrm{X}^{0}}\) … β

-

b.

*α … ]XP … β

-

a.

This condition captures the observation that periphrasis always yields regularity (2012:3), which holds true in his cross-linguistic survey of comparative morphology. He finds affixal patterns like small ∼ smaller, with no root allomorphy, and good ∼ better, where root allomorphy is conditioned by a terminal within the word. He also finds periphrastic patterns like minuscule ∼ more minuscule, with no root allomorphy, but no periphrastic patterns like *good ∼ more bett, where root allomorphy is conditioned by a terminal outside the word (though see Bobaljik and Harley 2017 for further discussion).

Bobaljik enriches his theory with an adjacency condition (Bobaljik 2012:149), which has the same ultimate effect as Merchant’s Span Adjacency condition: Conditioning features must occur in nodes, or sequences of nodes, which are adjacent to the root. Even more stringently, he also proposes that substructures of suppletion-conditioning contexts must themselves have suppletive realizations (2012:150).

Some others have proposed that there are cyclic domain nodes within words which function somewhat like the cyclic domain nodes in the phrasal syntax (Moskal 2014, 2015a, 2015b), involving an ‘Accessibility Domain’ which includes the phase head plus one additional layer of structure. Patterns which have been argued to support this ‘phases-within-words’ approach include the usual inner vs. outer morphology effects, as well as ‘level 1’ vs ‘level 2’ phonological cycles and related phenomena (see, e.g., Marvin 2003; Newell 2008; Newell et al. 2016; Piggot and Newell 2006; Samuels 2011).

We show that Korean root suppletion patterns require the rejection of most of these locality constraints. Allomorphic Vocabulary Items can be conditioned across structurally intervening nodes within the complex word, hence Spanning-dependent approaches like Merchant (2015), the adjacency constraint of Bobaljik (2012), and the Accessibility Domain approach of Moskal (2014, 2015a, 2015b) are not adequate.Footnote 3 We also show that allomorphic vocabulary items can be conditioned across linearly intervening nodes, hence linear-adjacency approaches like Embick (2010) are also problematic. Arad-style analyses do not countenance the possibility of structural intervention at all, so they are also not able to account for the Korean data. We also do not make use of the notion of phases-within-words in our analysis, though see discussion in Sect. 4.

The strongest extant constraint that the Korean analysis is consistent with is Bobaljik’s basic Root Suppletion Condition in (4) above: allomorphic conditioning can occur within the complex X0 domain. We also show that hierarchical locality is relevant to allomorphic conditioning, because of the independent nature of Korean negation and honorification, arguing against the Fusion-based approach of Chung (2009). This is reminiscent of, though not identical, to Bobaljik’s (2012) finding that when one potential conditioning environment strictly contains another more local conditioning environment, the more local environment takes precedence. We show that in contexts where two competing items are equally featurally complex, the item conditioned by the most local feature wins. We suggest that this is a necessary result of a theory which requires bottom-up, root-outwards vocabulary insertion, and hence dub this the Local Allomorph Selection Theorem:

-

(5)

Local Allomorph Selection Theorem:

If two vocabulary items are in competition, and the Subset Principle does not apply, then the vocabulary item conditioned by a more local feature blocks the vocabulary item conditioned by the less local feature.

We begin by developing an account of regular subject honorification, marked by the suffix -si.

2 Analysis of regular Korean subject honorification

Subject honorification in Korean provides a rich empirical domain in which to investigate the morphology-syntax interface, as it depends on the interaction of many independent syntactic and morphological processes. It exhibits agreement-like behavior with specially case-marked subject NPs (6), it can be expressed through suppletion (6b) as well as affixation (6a, c, d), and it can optionally exhibit multiple exponence in some contexts (6c, d).Footnote 4

-

(6)

We first establish that an agreement treatment of -si inflection is appropriate, following Ahn (2002), Ahn and Yoon (1989), Han (1993), Koopman (2005), Yun (1993), among others, and address concerns about the syntactic approach raised in Brown (2011) and Kim and Sells (2007), and discussed in Yun (1993).

2.1 Honorification as subject agreement

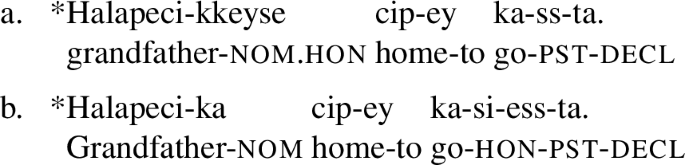

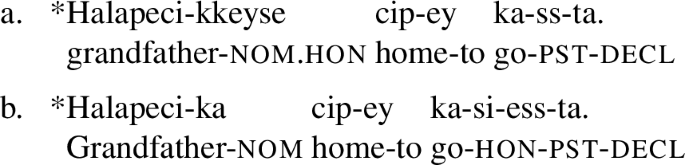

An agreement approach to honorific marking is suggested by the simple fact that any overtly honorific nominative NP—i.e., any NP marked with the special honorific nominative case suffix -kkeyse—must co-occur with honorific verbal suffix -si, as in (7) and (8). (Schütze 2001 establishes that -kkeyse is indeed a nominative case marker.) Mandatory co-occurrence of this kind is the hallmark of syntactic agreement patterns.

-

(7)

-

(8)

Most previous literature has adopted an agreement-based approach (Ahn 2002; Ahn and Yoon 1989; Han 1993; Koopman 2005; Yun 1993; a.o.). The -kkeyse nominative marker realizes a nominative case node that is bundled with a [+hon] feature, and this [+hon] feature mandatorily triggers agreement marking on the verb.

However, there are contexts where -si appears but the triggering NP is not a nominative -kkeyse-marked subject. Such cases have caused Brown (2011) and Kim and Sells (2007) to question whether honorification should be treated syntactically. We argue below that most such cases can be treated as syntactic agreement once another important property of Korean syntax is taken into account, namely multiple-subject constructions created via possessor-raising. We show that most of the counterexamples have grammatical variants with overt possessor-raising, and that in contexts where overt possessor raising is impossible, exceptional subject honorification is also impossible. This suggests that in these cases, the possessor raises covertly, creating an honorific nominative subject and triggering honorific agreement. We follow Yun (1993) in analyzing other counterexamples involving subject nominals denoting respected professions or social positions as being lexically bundled with the [+hon] feature.Footnote 5

2.1.1 Honorification triggered by honorific possessors

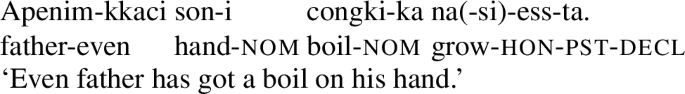

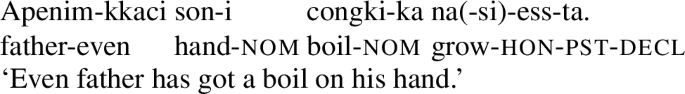

Brown (2011:31–32) points out that when a subject contains an honorific possessor, honorific marking is possible on the verb, even when -kkeyse is not present:

-

(9)

Because the NP halapeci-uy ‘Grandfather’s’ is contained within the subject NP halapeci-uy cip-i ‘Grandfather’s house’, in (9b), the honorific NP is not itself a subject and the grammaticality of -si here is unexpected on an agreement analysis.

However, Korean has a well-known process of possessor-raising, which can produce multiple-nominative structures with some predicates (see, e.g., Choe 1987; Kang 1987; Yoon 1989; Ura 1996; Yun 2004; see also Ko 2007:Sect. 4 and references therein).Footnote 6 For example, (9a) and (9b) respectively have grammatical alternates (10a) and (10b), where the possessor NP is marked with a second nominative, surfacing as -kkeyse:

-

(10)

We build on the conclusions of Han and Kim (2004), who propose that such structures involve adjoining the first ‘raised’ nominative possessor to the IP whose subject position is occupied by the possessed NP, where the second nominative is checked. This adjunction operation involves movement from the possessor position to the adjoined position; the structure is illustrated in (11) with ‘IP’ updated to ‘TP’.

-

(11)

We hypothesize that structures of this type underlie the examples in (9), i.e., that they involve ‘covert’ possessor raising, modelled as optional spell-out of the tail of the movement chain illustrated in (11). When honorification is present, a higher copy of the honorific possessive NP is present but unpronounced, the chain instead being realized by the lower copy within the possessed NP.Footnote 7 The covert higher subject licenses the appearance of -si on the verb. At LF, they are identical to the examples in (10), where overt possessor raising with an honorific case marker mandatorily triggers honorification. (See Kishimoto 2013:Sect. 3 for an independent argument for covert possessor raising in Japanese.)

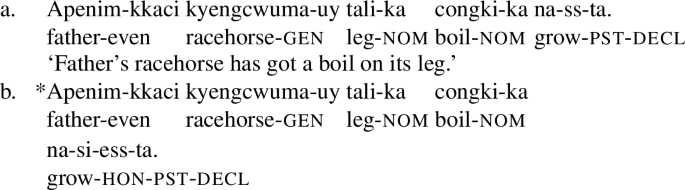

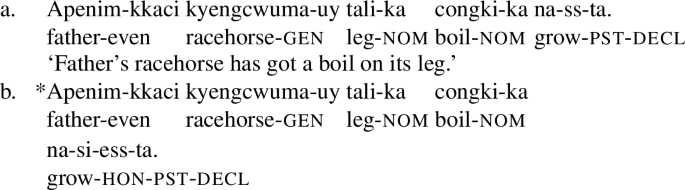

This predicts that in sentences where multiple nominative constructions are impossible, i.e., in sentences with possessed subjects expressing alienable possession (12a), as opposed to (12b), honorific marking in agreement with an honorific possessor should also be impossible (13a), as opposed to (13b).

-

(12)

-

(13)

The correlation between the availability of possessor-raised multiple subjects and exceptional subject honorification thus supports an agreement treatment of honorification.

2.1.2 Multiple-topic honorification is possessor honorification

A second class of examples in which the honorific NP does not stand in a normal agreement-triggering configuration with the verb involves multiple topic structures, like those in (14) and (15) (Yun 1993:34–67):

-

(14)

-

(15)

We argue that such cases are also best understood as subcases of the previous type, taking into consideration the possibility of pro-drop in multiple nominative constructions. Korean permits a topic-comment construction, with a topic phrase in the left periphery that is co-indexed with a (null) pronominal in the argument structure of the clause (Huang 1984). This suggests a potential hypothesis concerning (14) and (15): if the left-dislocated topics apenim-kkaci ‘father-even’ and kyoswunim-ulopwuthe ‘professor-from’ are co-indexed with pro possessors in the subjects of these examples (pro congki-ka ‘his boil-nom’, pro yensel-i ‘his speech-nom’), then the potential for honorification can be understood in the same way as that of the possessive examples in the previous section, in terms of possessor raising (in this case of pro) to nominative subject status. As expected, the subject honorification examples above have explicitly possessive and multiple-nominative variants:

-

(16)

-

(17)

We show that a possessor relation between the topicalized element and the nominative NP in (14) is necessary by introducing an overt possessor, disjoint from the topic (18). This yields ungrammaticality, showing that the honorific topic NP must stand in a possessor relation with the subject in such exceptional honorification examples:

-

(18)

Similarly with respect to (15), we show in (19) it is impossible to construct the sentence with a disjoint possessive NP in combination with the professor-from topic PP. Without the from-PP, the nominative subject speech can have an overt possessor NP, as in (19a), but it is impossible to combine this with a topicalized from-PP (with or without honorific marking), as in (19b). That is, in this construction, the from-PP must be co-referential with the possessor of the speech, which we claim is syntactically represented by a pro NP. This pro possessor introduces the possibility of possessor raising and hence has the potential to license subject honorific agreement.

-

(19)

We conclude that these apparent cases of honorific topics should be subsumed under the honorific nominative possessor proposal.

2.1.3 Lexically honorific nouns do not need overt -kkeyse

Finally, Kim and Sells (2007) identify cases where honorific marking appears in the absence of honorific nominative case (20a):

-

(20)

Here, no covert multiple nominative can be relevant, since there is no possession structure possible and nominative marking is overt and non-honorific. If honorification is a reflex of syntactic agreement with an honorific nominative NP, how can such a non-honorific nominative NP trigger it?

In fact, as argued by Yun (1993), in the usual case, non-honorific NPs are ungrammatical with honorific agreement on the predicate; as we showed in (7) and (8) above, -kkeyse is normally required in order for honorific marking to occur. Nouns which can occur in contexts like (20a) above, where -kkeyse is not present, can optionally encode honorific status lexically, depending on the perspective of the speaker. They belong to a class of lexical items which denote necessarily high-status roles, and hence may entail honorific status for the NP in relation to the status of the speaker.Footnote 8 Yun (1993:Sect. 2.5.2) proposes a system of lexically inherent features for such nouns, which we adopt here. An NP which can bear an inherent honorific feature can trigger honorific agreement even without a [+hon] nominative suffix, but an NP without such an inherent feature can (and must) only trigger honorific agreement when the [+hon] feature is in the case node (a choice at the discretion of the speaker). Yun proposes that lexically honorific nouns have non-honorific equivalents, which are used when the relative status of the speaker makes honorification unnecessary, explaining the apparent optionality of honorific agreement with such nouns. We summarize the patterns of agreement below:

-

(21)

-

a.

Noun-nom[+hon] Predicate-hon

-

b.

*Noun-nom[+hon] Predicate

-

c.

Noun[+hon]-nom[-hon] Predicate-hon

-

d.

*Noun-nom[-hon] Predicate-hon

-

e.

Noun-nom[-hon] Predicate

-

a.

Following Yun, then, honorification is syntactically triggered in examples like (20a) above, by virtue of the (optional) lexical honorific property of the subject nominal. In Yun’s treatment, the honorific and non-honorific versions of these nouns represent two separate lexical entries. We hypothesize instead that the [+hon] feature is optionally bundled with a high-status root when it is selected for inclusion in the numeration, allowing for the context-dependence of honorification. Either formalization would account for the documented patterns, and nothing hangs on the choice.

Having argued that subject honorification is a type of agreement, we next argue that Korean provides support for treating agreement as a syntactically governed but morphologically executed operation.

2.2 Agreement as a post-syntactic operation: Double exponence and ellipsis

Many syntactic accounts of agreement have posited dedicated AgrP projections (Ahn 2002; Ahn and Yoon 1989; Chomsky 1993; Pollock 1991). Subject agreement in such accounts is the realization of an AgrS0 head which projects an AgrSP, usually adjacent to TP in the extended verbal projection. In contrast, DM accounts of agreement (Bobaljik 2008; Halle and Marantz 1993; Deal 2016, a.o.) argue that agreement nodes are adjoined in the morphological component, via node-sprouting, when an appropriate structural configuration is met. In this kind of analysis, agreement marking is a morphological response to a syntactic configuration, rather than a purely syntactic operation or structure. We argue, with Yi (1994) and Sells (1995), that -si subject honorification cannot be treated via syntactic AgrP projection, and subsequently propose a node-sprouting analysis within DM.

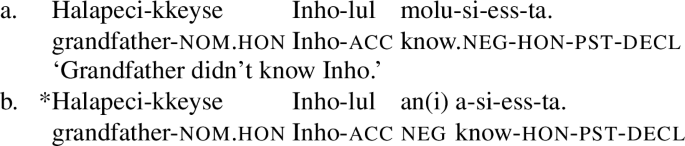

2.2.1 What long-form negation tells us about honorification

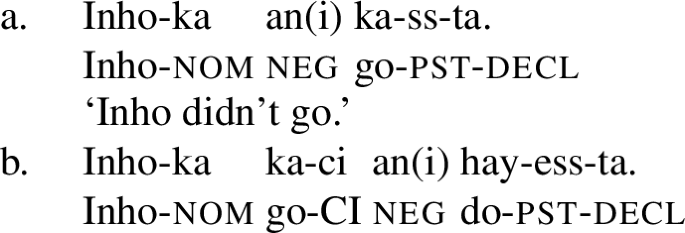

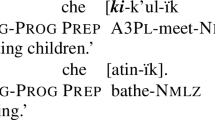

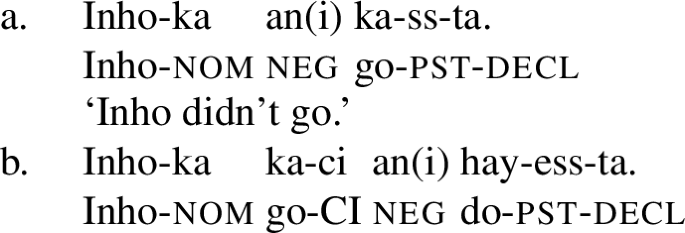

The first argument for a morphological approach to honorific agreement comes from the interaction of honorification with so-called ‘long-form’ negation. Korean has two types of sentential negation: ‘long-form’ and ‘short-form’ negation. In short-form negation, the negative morpheme an(i) simply precedes the main verb (22a). Long-form negation, in contrast, requires a non-finite main verb followed by the dummy verb ha- ‘do’. The negation marker an(i) precedes ha- ‘do’ (22b).

-

(22)

The by-now standard view of the long-form negation construction in (22b) is that the main verb remains in the VP domain (i.e., within VoiceP/vP, in modern architectures; we use the ‘vP’ terminology here), and a light verb ha- is inserted to support the stranded inflectional material above vP, i.e., it’s a form of do-support.Footnote 9 In contrast, in short-form negation, the negative an(i) is an adverbial adjoined to vP (Han and Lee 2007; see also Han and Park 1994), which cliticizes to the verb (see discussion in Sect. 3.2.1 below). The do-support analysis of Korean long-form negation is illustrated in (23), an updated version of proposals in many previous accounts, including Han and Lee (2007).Footnote 10

-

(23)

Taking a do-support analysis of long-form negation as a base, Yi (1994) considers the interaction of honorification and long-form negation.Footnote 11 Yi (1994) points out that regular honorific -si can occur either on the lower main verb (24a), the higher dummy verb (24b), or both (24c).Footnote 12

-

(24)

Yi argues, as does Sells (1995:305), that the pattern in (24), particularly (24c), is a fatal problem for projection-based AgrP treatments of honorification, given the usual assumption that each functional projection is only instantiated once in the extended projection of the verb.Footnote 13 Assuming the Mirror Principle applies as usual, a low position for AgrSP predicts the possibility of (24a) but rules out (24b) and (24c); a high position allows (24b) but not (24a) and (24c); and no such approach can account for the double-marking in (24c), given the standard view that two AgrSPs should not occur in the same functional sequence.Footnote 14

Yi (1994) instead proposes that honorific agreement is the reflex of a spec-head relationship between an honorific subject and a verb in either Spec-VP, Spec-TP, or both. Yi assumes a Chomsky (1993)-style lexical approach to the packaging of agreement morphology on verbs; a verb may be inserted into the syntactic derivation with or without an agreement feature. She suggests that as long as an honorific subject enters into a spec-head relation with some agreeing verb, the derivation will converge.

A syntactic feature-checking approach also falls short, however. The particular insight of the do-support view of long-form negation is that the insertion of dummy ha- is a post-syntactic phenomenon, driven by the morphological ill-formedness of the negation-tense complex when the syntax fails to place a verbal root in an appropriate position. If this is correct, then honorification on the dummy ha- must also be post-syntactic. Since the appearance of honorific marking depends on the presence of a verb, and the verb ha- does not appear until after the syntactic derivation is handed off to the morphological component, it follows that -si marking also must occur in the morphological component. The optional HonP projection analysis of Kim and Sells (2007) is problematic for the same reason: Since the honorific -si is attached to the post-syntactic dummy verb, HonP cannot be present in syntax.Footnote 15

2.2.2 Ellipsis and the nature of honorific agreement

Korean has a variety of ellipsis types, including gapping, sluicing and yey-ellipsis (Kim 2012). In such cases, an antecedent clause containing an honorific subject and overt honorification can license ellipsis of a non-honorific constituent (25a), and vice versa (25b):

-

(25)

These patterns provide another reason to think that a post-syntactic approach to honorification may have an advantage over a purely syntactic approach in which honorification is projected as a constituent in the syntactic spine (Chung 2009; Kim and Sells 2007). Under syntactic-identity approaches to ellipsis, like that of Merchant (2013), a syntactic approach to honorification would predict that the honorific projection should be necessarily copied under ellipsis, and mismatches of honorific properties between antecedent and ellipsis site should be impossible.Footnote 16 If, instead, the honorification node is sprouted, inserted post-syntactically when certain structural conditions are met, its presence or absence is not expected to affect ellipsis.

To sum up the previous two sections, we have argued that honorific marking in Korean is structurally determined, and that it occurs in the presence of an honorific nominative NP. We have further argued, however, that a purely syntactic account is problematic, based on the potential for double exponence in long-form negation, the morphological status of the dummy verb ha- in long-form negation, and the distribution of honorification in ellipsis constructions. We conclude that an appropriate structural configuration triggers the application of a morphological honorification rule, sprouting a dissociated agreement node post-syntactically. We spell this out next.

2.3 A node-sprouting analysis of regular subject honorification

DM’s general approach to agreement marking extends naturally to account for Korean honorification. The key is the mechanism of dissociated morpheme insertion, which as we have mentioned above, we have rechristened ‘node-sprouting.’

Halle and Marantz (1993) propose that agreement morphemes are the reflex of language-specific well-formedness constraints that apply at the level of Morphological Structure. They are triggered when certain configurational requirements are met by the structure handed off at Spell-Out. A node-sprouting rule adjoins a ‘dissociated’ Agr0 node to a target and copies features of the controlling NP into it. The Agr0node is subsequently spelled-out by a vocabulary item that realizes its featural content. The fact that agreement has no LF reflex follows, since node-sprouting happens after Spell-Out, on the PF branch only. Their proposal is thus consistent with Chomsky’s (1995:349–355) conclusion that AgrPs, lacking interpretable LF properties, do not appear in the syntax. (See also Bobaljik 2008 and Deal 2016, among others, for additional treatments of agreement as a post-syntactic operation.)

2.3.1 Honorification in simple affirmative clauses

We propose that a sprouted [+hon] agreement morpheme (notated Hon0) is adjoined to a terminal v0 node c-commanded by an honorific nominative NP. This structurally-conditioned insertion rule is schematized in (26) below.

-

(26)

Hon 0 -sprouting rule:

v0 → [v0 Hon0] / [NP[+hon] … [... __ ...]]

This rule expresses the intuition that honorification applies all and only to verbs, since in DM verbs are created by the v0 head. The ellipses allow for any c-commanding NP[+hon] to condition Hon0-sprouting, regardless of structural distance, but the cyclic character of Spell-Out means that in practice the structural distance is phase-bound: the triggering NP and the target v0 must be in the same Spell-Out domain. The unbounded structural description in the rule is thus consistent with the Minimalist view of locality as an interface effect arising from the cyclicity of phase-based Spell-Out.

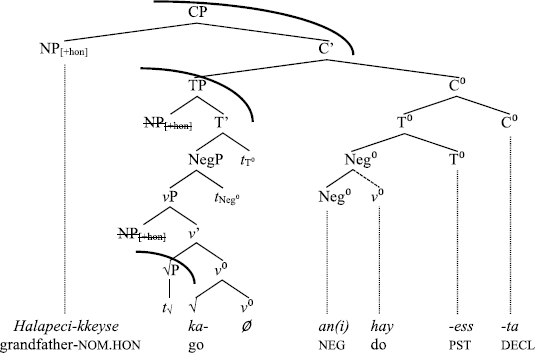

We illustrate how this rule operates in an affirmative declarative sentence like halapeci-kkeyse ka-si-ess-ta ‘Grandfather went’. We assume an articulated structure for the VP. The lexical verb heads a  P which is verbalized by a vP. The [+hon] external argument of the verb, with a uNom case feature, is base-generated in Spec-vP.Footnote 17 (The external argument ultimately enters into an Agree relationship with Tense to value its uNom feature.) The root of the verb,

P which is verbalized by a vP. The [+hon] external argument of the verb, with a uNom case feature, is base-generated in Spec-vP.Footnote 17 (The external argument ultimately enters into an Agree relationship with Tense to value its uNom feature.) The root of the verb,  , head-moves to v0, forming a complex head

, head-moves to v0, forming a complex head  -v0 in the edge of the phase.Footnote 18 We assume that the edge of a phase consists of its head and its specifier(s), as in Chomsky (2001), and that these elements remain accessible to further syntactic operations in the next phase. When a phase is ‘transferred to Spell-Out’, it is the phase complement, in this case

-v0 in the edge of the phase.Footnote 18 We assume that the edge of a phase consists of its head and its specifier(s), as in Chomsky (2001), and that these elements remain accessible to further syntactic operations in the next phase. When a phase is ‘transferred to Spell-Out’, it is the phase complement, in this case  P, which is spelled-out and becomes inaccessible to further operations. The construction of the next phase continues with the merger of T0 and C0. The complex verb in v0 head-moves to T0 and C0, illustrated in (27) below. Spelled-out phasal complement constituents are demarcated by bold curves. Following head-movement, the verb ends up in the C0 head, whose internal structure is illustrated in (28a).

P, which is spelled-out and becomes inaccessible to further operations. The construction of the next phase continues with the merger of T0 and C0. The complex verb in v0 head-moves to T0 and C0, illustrated in (27) below. Spelled-out phasal complement constituents are demarcated by bold curves. Following head-movement, the verb ends up in the C0 head, whose internal structure is illustrated in (28a).

-

(27)

At the end of the derivation, a final spell-out cycle applies (represented by the topmost bold curve in (27)). Assuming that Korean subjects occur in discourse-related positions in the left periphery (see, e.g., Sohn 1980 on the topichood of Korean subjects), the nominative subject c-commands the complex head in C0 (28a) in this final cycle. Since the structural condition for the Hon0-sprouting rule in (26) is met, Hon0 is adjoined to v0, yielding (28b).Footnote 19

-

(28)

The terminal nodes of this complex and now honorified verb are subsequently realized by the appropriate honorific and tense suffixes, following Vocabulary Insertion at the end of the morphological component.

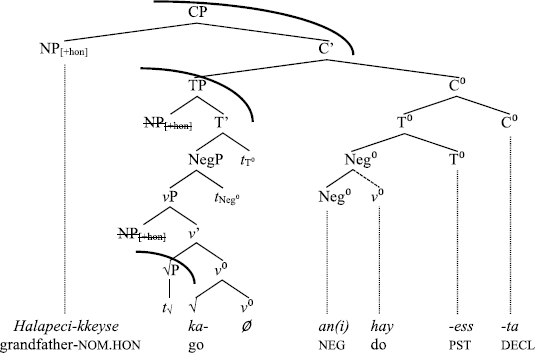

2.3.2 Long-form negation and double honorific exponence

Now consider how the node-sprouting rule behaves in a long-form negation structure. In the derivation of a negative sentence like (24) the same sequence of events as in an affirmative sentence occurs up to the vP level. This results in the formation of a complex head in v0.Footnote 20 In the next phase, however, the  -v0 complex does not raise to T0, because of the intervening Neg0 head. Instead, Neg0 raises to T0 and C0 on its own, ultimately forming a verbless complex head in the matrix C0 position. The full clausal syntax is illustrated in (29):

-v0 complex does not raise to T0, because of the intervening Neg0 head. Instead, Neg0 raises to T0 and C0 on its own, ultimately forming a verbless complex head in the matrix C0 position. The full clausal syntax is illustrated in (29):

-

(29)

In this structure, two spell-out cycles are relevant. The first occurs when C0 is merged. Its complement domain undergoes a spell-out cycle. The complex head containing the main verb is part of this spell-out domain, since it remains low, in v0. The Hon0-sprouting rule is thus triggered (by the copy of NP[+hon] in spec-TP) and adjoins Hon0 to v0 within this complex head (see the diagram in (31)).

The second relevant cycle of spell-out is the final one, applying to the root clause. The complex head in C0 has no verbal root in it. This triggers do-support, which we formalize as the node-sprouting rule in (30), inserting a sprouted v0 morpheme to support Neg0 when it lacks a v0 sister in the [[Neg0-T0]\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\)-C0]\(_{\mathrm{C}^{0}}\) complex head.Footnote 21

-

(30)

v0-sprouting (do-insertion) rule:

Neg0 → [Neg0v0] / [ ___ T0]\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\)

Following v0-sprouting, the structural configuration for the Hon0-sprouting rule in (26) is met. This results in a sprouted Hon0 node adjoined to the sprouted v0 node, yielding (31):

-

(31)

At the end of the morphological derivation, Vocabulary Insertion rules apply, spelling out each adjoined Hon0 node with a rule that inserts the Vocabulary Item -si.

-

(32)

Rule for spelling out Hon0 (to be updated): Hon0 ↔ -si

The inclusion of a v0 node in the conditioning environment for Hon0-sprouting, then, predicts double honorific marking to appear when two verbal categories are present, as in the long-form negation construction, and, as we will shortly see, in other constructions involving two verbal categories.Footnote 22 As we have seen above in Sect. 2.2.1, double honorific marking is optional. Before discussing the optionality, we first illustrate the other contexts in which double marking is possible, namely in the verb-copy constructions discussed by Jo (2013) and Chung (2009).

2.3.3 Verb-copy constructions and the optionality of double exponence of Hon0

Like many languages (Landau 2007), Korean has a ‘verb-(phrase)-copy’ construction which is used in certain focus- and polarity-related discourse environments. There are three varieties, which follow the general schema [Subject-[(Obj) V1]-[ V2]], analyzed most recently in Jo (2013). V1 and V2 must be interpreted identically, and can be morphologically identical, although they need not be; V1 can bear a subset of the inflection of V2, which Jo consequently treats as the head of the clause. A basic example is given in (33).

Chung (2009) points out that honorification marking need not be fully copied, as it is in (33b) and (33c); it can occur on just the head, V2, as in (33b), or just the copied verb (V1) as in (33c).

-

(33)

Placing this case side by side with the long-form-negation case in (24) above, we see that when multiple occurrences of regular -si are possible, their actual realization is subject to variation. At least one honorific exponent must appear, but multiple occurrences are typically optional. The availability of double marking confirms that Hon0 nodes are inserted in both locations, by the regular application of the dissociated-Hon0 insertion rule.

We hypothesize that optionality of -si is a surface phenomenon, representing ellipsis of -si under identity with another copy of -si. An ellipsis analysis is consistent with the requirement that at least one copy be pronounced, a phenomenon observed in ellipsis quite generally. In ellipsis, a linguistic antecedent is necessary to recover the content of the elided element.Footnote 23

There are some conditions on -si ellipsis—for example, in verb-copy constructions it is somewhat better to retain -si on the main, inflected predicate and elide it on the adjoined copy; a similar pattern is seen in long-form negation, where the inflected head verb ha- is more likely to bear honorific marking, and a single occurrence of -si on the nonfinite embedded verb is less preferred.Footnote 24

We return to multiple honorification and provide an argument for the presence of a sprouted Hon0 node even in contexts where the surface appearance of -si is optional, in our analysis of suppletive honorification in Sect. 3.

3 Analysis of honorific and negative suppletion

Chung (2009) was the first to point out the theoretical importance of the interaction of two suppletion-triggering environments in Korean, namely short-form negation and honorification. We first give a brief overview of the relevant data and argue for an inflectional (i.e., ‘paradigmatic,’ competition-based) approach to both cases of suppletion. We provide a formal analysis of honorific and negative suppletion individually, and then address their interaction. The ‘transparency’ of regular honorification for suppletive negation contrasts importantly with the blocking effect of suppletive honorification on suppletive negation. From this, we draw conclusions about the locality domains for suppletion conditioning and about the bottom-up character of Vocabulary Insertion. Finally, we discuss the distinct accessible domains we have identified for node-sprouting rules and suppletion.

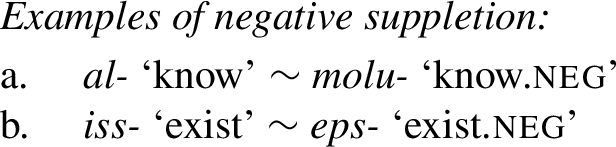

3.1 Suppletive honorification and suppletive negation are suppletion: Idioms and ellipsis

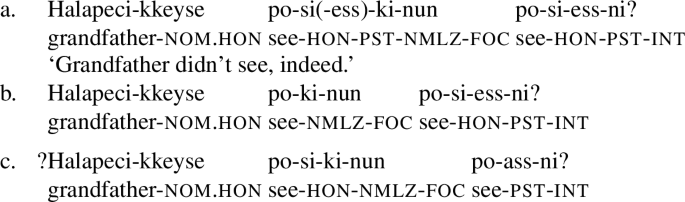

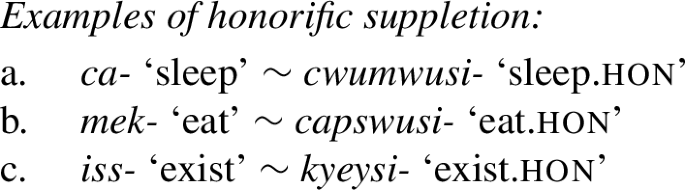

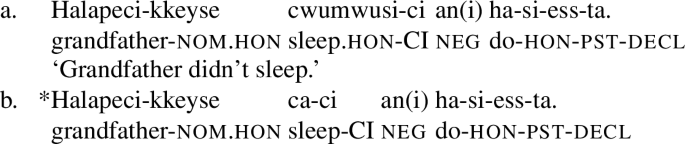

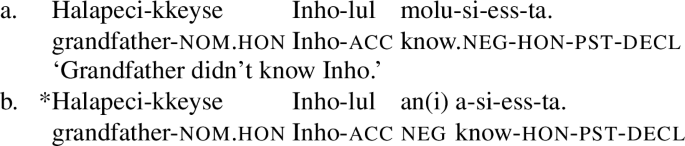

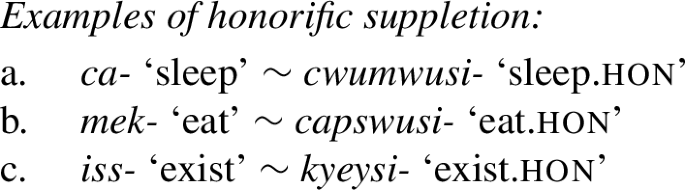

As mentioned above, a small number of Korean verbs have suppletive forms conditioned by honorification (34):

-

(34)

Two verbs have negative suppletive forms (35). Chung (2007) argues convincingly that the structural environment which triggers negative suppletion is short-form negation.

-

(35)

Note, importantly, that one verb, iss- ‘exist’ ∼ eps- ‘exist.neg’ ∼ kyeysi- ‘exist.HON’, is on both lists; the behavior of suppletion when short-form negation and honorification co-occur is revealed by this verb.

Suppletion is often a controversial topic. Although most of the literature accepts the notion that these Korean forms stand in a suppletive relationship, it is perhaps worth pausing to motivate the inflectional, paradigmatic status of these alternations. It could be suggested that each of the negative and honorific verb forms is in fact an individual lexeme which just happens to have a closely related complementary distribution to an independent affirmative or non-honorific lexeme with a similar meaning.Footnote 25 In fact, Bobaljik (2012:155–156) and Moskal (2015b:205–209) suggest that the very Korean suppletive honorific verbs discussed here may be separate lexical entries, rather than suppletive elements in competition. First we argue for a suppletive analysis with data from idioms, and then from ellipsis.

Besides paradigmatic distribution, a key diagnostic for suppletion involves coextensive interpretive variation. For example, in all English idioms involving the verb go, the form went occurs in the past tense, suggesting that both go and went realize a single underlying verb GO which participates in the idiom (compare, for example, go/went/*goed bananas ‘become/became insane’). Similar arguments can be made for honorific and negative suppletive forms in Korean, where an idiomatic interpretation available to the non-suppletive form is also available to the suppletive form. This is illustrated for two verbs, mek- ‘eat’ ∼ capswusi- ‘eat.hon’ and al- ‘know’ ∼ molu- ‘know.neg’ below.

In (36), the idiomatic interpretation of a phrase literally meaning ‘to eat crow meat’ is available with capswusi- ‘eat.hon’ as well as with the unmarked stem form mek- ‘eat’:

-

(36)

In (37), the idiomatic interpretation of a phrase literally meaning ‘to know lifting situations and putting situations’ is available in a negative context with the suppletive stem molu- ‘know.neg’.Footnote 26

-

(37)

The availability of these idiomatic interpretations with the suppletive stem alternants suggests that the different stems realize the same underlying abstract verb, and thus are true cases of suppletion.Footnote 27

Another diagnostic for suppletive status is presented in Harley (2015), who follows a suggestion of Bobaljik (p.c.) and Gribanova (2015) in using ellipsis constructions as a test for suppletion (cf. also Furbee 1974 on gapping as an argument for treating different verbs of consumption in Tojolabal as allomorphs). It is a well-accepted condition on ellipsis that the meaning of the antecedent and the elided constituent must be identical (no matter what specific approach to ellipsis is adopted, e.g., Merchant 2001 and Chung et al. 1995). Consider the VP ellipsis in (38):

-

(38)

John went to Hawai’i in the fall, but Mary didn’t [VP

].

].

The suppletive form of GO, went, licenses ellipsis in the second clause despite the fact that if the second clause were articulated, the verb would be pronounced go, rather than went. It is the identical abstract content GO TO HAWAI’I IN THE FALL, that licenses the ellipsis, not identity of the surface form. Similar patterns obtain with other elliptical processes, including sluicing and swiping.

In Korean, a suppletive form can license ellipsis of a non-suppletive form, and vice versa, as shown by the examples of verbal gapping in (39) below.

-

(39)

Other forms of ellipsis in Korean, including yey-ellipsis (Kim 2012), and sluicing also are licensed across suppletion, again confirming the underlying identity of the abstract verb, and the appropriateness of a competition-based analysis of these alternations.

We conclude that the two forms are competing to realize an abstract  node,

node,  EAT or

EAT or  KNOW, just like the morphologically-conditioned allomorphs of any abstract morpheme. If the appropriate conditioning context is present, the more specified form (e.g., capswusi- ‘eat.hon’or molu- ‘know.neg’) blocks the insertion of the elsewhere form (e.g., mek- ‘eat’ or al- ‘know’). To present the full analysis of this competition, we first must briefly discuss the morphosyntax of short-form negation below; the actual analysis of suppletion in terms of competing vocabulary insertion rules follows.

KNOW, just like the morphologically-conditioned allomorphs of any abstract morpheme. If the appropriate conditioning context is present, the more specified form (e.g., capswusi- ‘eat.hon’or molu- ‘know.neg’) blocks the insertion of the elsewhere form (e.g., mek- ‘eat’ or al- ‘know’). To present the full analysis of this competition, we first must briefly discuss the morphosyntax of short-form negation below; the actual analysis of suppletion in terms of competing vocabulary insertion rules follows.

3.1.1 The structure of short-form negation and negative suppletion

Han and Lee (2007) argue that the syntactic structure underlying short-form negation results from adjunction of an adverbial Neg0 to vP, with syntactic cliticization of Neg0 to the v0. Support for short-form negation as adverbial, rather than as the head of a sentential NegP projection, comes from the observation that short-form and long-form negation can co-occur in the same clause (see Han and Lee 2007), yielding a double-negation interpretation:

-

(40)

Chung (2007), in contrast, assumes that short-form negation is the realization of the head of NegP. That analysis predicts either that (40) is ungrammatical, or else that it somehow involves double exponence of a single Neg0 head, assuming that a single verbal extended projection should contain only a single NegP. The fact that each negative element is interpreted separately suggests that they occupy independent structural positions.

We therefore adopt Han and Lee’s proposal that short-form negation is adverbialFootnote 28 and requires cliticization of the negative adverb to the verb. It must be the case that the cliticization requirement is syntactic, i.e., it is a property of the Neg0 head itself, and is not specific to the Elsewhere an(i) vocabulary item which usually realizes it, since cliticization feeds suppletion in the case of the negative suppletive verbs: recall that Bobaljik (2012) argues that suppletion cannot be triggered across a phrasal boundary, so the cliticization of adjoined Neg0 to the verb form, creating a complex X0, is crucial to the conditioning of the negative suppletive forms.

We implement the operation which cliticizes Neg0 to v0 via morphological merger at the syntactic level, as discussed by Embick and Noyer (2001:561) and Matushansky (2006:81).Footnote 29 This is Embick and Noyer’s Lowering operation generalized to adjuncts, with the further observation that the complex head thus created can then feed further syntactic operations, as proposed by Matushansky in her treatment of head-movement.

-

(41)

Lowering (Embick and Noyer 2001:561)

[XP X0 … [YP … Y0 …]] → [XP … [YP … [\(_{\mathrm{Y}^{0}}\) Y0+X0] …]]

In Embick and Noyer’s treatment, Lowering is constrained by selection. If we assume that adjuncts select for their phrasal hosts, as proposed by Bruening (2010b), Toosarvandani (2013) and Winter (2001), we expect that the Neg0 head adjoined to vP can undergo Lowering, adjoining to the head of its complement, v0, immediately following Merge of Neg0 with vP. This operation is the e-Merge equivalent of Matushansky’s i-Merge head-movement operation, a predicted consequence of Matushansky’s proposal (Matushansky 2006:Sect. 5.1.2). The input and the output of this operation as applied to Korean Neg0 is illustrated below:

-

(42)

Note that the pre-Lowering position of Neg0 is the position in which it is interpreted at LF, so we assume this operation leaves a copy, which we indicate as a trace; this is consistent with the uncontroversial idea that m-merger/Lowering is triggered to satisfy morpho-syntactic well-formedness conditions, and lacks LF consequences. In effect, m-merger of Neg0 serves the same purpose that v0-sprouting does in long-form negation: It is a repair operation which enables a Neg0 head to prefix to a verb, albeit a Neg0 head with a different structural source.

In the context of a negative-suppletive verb like  KNOW, the vocabulary items in (43) compete to realize the verb root.

KNOW, the vocabulary items in (43) compete to realize the verb root.

-

(43)

-

a.

KNOW ↔ molu- / [Neg0 [[ ___ v0]\(_{v^{0}}\)]

KNOW ↔ molu- / [Neg0 [[ ___ v0]\(_{v^{0}}\)] -

b.

KNOW ↔ al- / elsewhere

KNOW ↔ al- / elsewhere

-

a.

In a short-form negation construction, the structural description for the vocabulary item in (43a) is met and the suppletive variant will be inserted. The relevant structure is a complex v0 head containing Neg0 as its least embedded element. This Neg0 conditions the suppletive realization of the root  KNOW. The v0 head itself is structurally more local to the root than Neg0, but this intervening structure is irrelevant to the conditioning of the root. This rule, involving conditioning by a structurally non-adjacent feature, is thus problematic for the stringent structural adjacency constraints inherent in Arad (2005), Bobaljik (2012), Merchant (2015) and Svenonius’s (2012) theories, but it may be permitted by Moskal’s (2014, 2015a, 2015b) Accessibility Domain condition.Footnote 30 (See Sect. 4 below for discussion of case that is problematic for Moskal’s proposal.)

KNOW. The v0 head itself is structurally more local to the root than Neg0, but this intervening structure is irrelevant to the conditioning of the root. This rule, involving conditioning by a structurally non-adjacent feature, is thus problematic for the stringent structural adjacency constraints inherent in Arad (2005), Bobaljik (2012), Merchant (2015) and Svenonius’s (2012) theories, but it may be permitted by Moskal’s (2014, 2015a, 2015b) Accessibility Domain condition.Footnote 30 (See Sect. 4 below for discussion of case that is problematic for Moskal’s proposal.)

We assume, contra Chung (2009), that the Neg0 head itself is realized by a zero allomorph conditioned by the suppletive root form.Footnote 31

3.1.2 Analysis of honorific suppletion

We propose that suppletive honorific root forms are inserted when the abstract root occurs in the same complex X0 head as an Hon0 morpheme, in accordance with Bobaljik’s (2012) Locally Conditioned Suppletion hypothesis. The Vocabulary Items below compete to realize the abstract roots of suppletive verbs, with the honorific forms blocking the elsewhere forms if an Hon0 node is present in the X0.Footnote 32

-

(44)

The derivation of the honorific verb form in (39b) is given in (45) below. Following Hon0-sprouting, the structural description of the suppletive allomorph of  SLEEP is met (see (44a)), and so

SLEEP is met (see (44a)), and so  SLEEP is realized as cwumwusi-, rather than ca-.

SLEEP is realized as cwumwusi-, rather than ca-.

-

(45)

3.1.3 Locality domains for suppletion and periphrastic contexts

Let us consider how negative and honorific suppletive verbs are predicted to behave in our analysis in a long-form negation construction. Recall that an honorific subject triggers node-sprouting of an Hon0 node on both the lower, stranded v0 and on the higher dummy v0. Honorific suppletion of the lower main verb in long-form negation is thus predicted, since the local Hon0 node matches the contextual requirement for insertion of the honorific suppletive root. An honorific subject in long-form negation does indeed trigger suppletion on the lower verb:

-

(46)

In contrast, however, a negative suppletive verb does not use its suppletive alternant in long-form negation (Chung 2007:119). The non-negative verb root must be used instead:

-

(47)

Importantly, these different distributions of honorific and negative suppletive roots in long-form negation contexts support the hypothesis that an Hon0 node appears low in the structure in long-form negation. Recall Bobaljik’s observation, discussed in Sect. 1.2, that periphrastic expression of a suppletion-triggering feature blocks root suppletion cross-linguistically. He concludes that the locality domain for suppletion is the complex X0 head. In long-form negation, the negative-suppletive root remains in a separate X0, and does not exhibit negative suppletion, despite the presence of negation elsewhere in the structure. That is, the periphrastic expression of negation bleeds root suppletion, as expected. The fact that verbal periphrasis does not bleed suppletive exponence in honorific root suppletion confirms that there is an Hon0 node in both the main and dummy verbal complexes, and bolsters the notion that the X0 domain is the locality frame relevant to suppletive conditioning.

We have now spelled out our proposals for the structures underlying honorification, long-form negation and short-form negation, including the idea that honorification is accomplished via structurally-conditioned node-sprouting rule in the morphological component. We have asserted, though not yet argued, that the domain of application for node-sprouting rules is phasal, applying when each phasal complement domain is cyclically transferred to the PF branch for Spell-Out. We have further articulated how vocabulary item competition interacts with these structures to generate the surface forms of both regular and suppletive honorification and negation, suggesting that the relevant locality domain within which suppletive vocabulary items can be conditioned is the complex X0. We next turn to the interaction of honorific marking and short-form negation in suppletive contexts first discussed by Chung (2009).

3.2 Interaction of suppletive negation with regular and suppletive honorification

Now consider the structure involved when honorification co-occurs with short-form negation. Node-sprouting of Hon0 on the terminal v0 head, and cliticization of Neg0 to the v0 complex, generates the complex head illustrated in (48) below.

-

(48)

In a regular verb, each terminal node is realized by the single relevant vocabulary item, yielding, e.g., [an(i)\(_{\mathrm{Neg}^{0}}\)=[[ka ]-[\(\emptyset_{v^{0}}\)-si\(_{\mathrm{Hon}^{0}}\)]]-ess\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\)-ta\(_{\mathrm{C}^{0}}\)].

]-[\(\emptyset_{v^{0}}\)-si\(_{\mathrm{Hon}^{0}}\)]]-ess\(_{\mathrm{T}^{0}}\)-ta\(_{\mathrm{C}^{0}}\)].

In (48) the Hon0 morpheme, sprouted on the sister to the  , is more local to the verb root than the Neg0 morpheme. We argue that this drives the interaction of negative and honorific suppletion that occurs with Korean’s only triply-suppletive verb,

, is more local to the verb root than the Neg0 morpheme. We argue that this drives the interaction of negative and honorific suppletion that occurs with Korean’s only triply-suppletive verb,  EXIST. As mentioned above, this verb has an elsewhere root, a negative root, and an honorific root, each of which is illustrated in (49) below. The elsewhere form occurs in affirmative non-honorific contexts (49a) and non-honorific long-form negation contexts. The negative form occurs in non-honorific short-form negation contexts (49b). The honorific form occurs in honorific contexts (49c):

EXIST. As mentioned above, this verb has an elsewhere root, a negative root, and an honorific root, each of which is illustrated in (49) below. The elsewhere form occurs in affirmative non-honorific contexts (49a) and non-honorific long-form negation contexts. The negative form occurs in non-honorific short-form negation contexts (49b). The honorific form occurs in honorific contexts (49c):

-

(49)

Crucially, in honorific and short-form negation contexts, as emphasized by Chung (2009), the honorific form blocks the negative form:

-

(50)

The morphological structure of the inflected verb of (50a) and the relevant Vocabulary Insertion rules which determine the choice of allomorph for  EXIST are respectively illustrated in (51) and (52).

EXIST are respectively illustrated in (51) and (52).

-

(51)

-

(52)

Let us examine how these VIs interact with the complex honorific short-form negation head in (48). The outcome of the competition for the realization of  EXIST is not obvious. Both the negative and the honorific root are conditioned by the presence of a single feature, so there is no clear Subset-principle ordering of the two conditioned allomorphs. Yet the honorific form of

EXIST is not obvious. Both the negative and the honorific root are conditioned by the presence of a single feature, so there is no clear Subset-principle ordering of the two conditioned allomorphs. Yet the honorific form of  EXIST blocks the insertion of the negative form. Why? Some competition-resolving constraint must be at work.

EXIST blocks the insertion of the negative form. Why? Some competition-resolving constraint must be at work.

Let us revisit the various locality principles from the previous literature given in Sect. 1.2, and ask whether any of them resolve the competition between kyeysi- ‘exist.hon’ and eps- ‘exist.neg’ in negative honorific structures.

Embick (2010) argues that suppletion requires linear adjacency between the conditioned and conditioning nodes, highlighting the irrelevance of null exponents in potentially intervening nodes in cases like the English past tense. However, in the case of Korean, the short-form negative (pro)clitic is prefixal while the honorific exponent is suffixal. The v0 node that arguably intervenes between the root and the honorific suffix is null, with the result that both negation and honorification are linearly adjacent to the conditioned root. The linear adjacency condition, then, does not resolve the competition between (52a) and (52b).

Similarly, Bobaljik’s (2012) X0 condition, according to which allomorph selection cannot be conditioned across a phrasal boundary, does not resolve the competition. Both Neg0 and Hon0 are contained within the complex X0 head, and hence both are in principle local enough to condition a suppletive alternant (and both can, independently). The X0 condition, then, also does not by itself yield a blocking effect.

It seems clear that hierarchical locality—structural locality—must play a role in determining allomorph selection. Merchant’s (2015:294) Span Adjacency Hypothesis, rather like the earliest proposals stipulating strict structural adjacency between trigger and target (e.g., Arad 2003, 2005), has the potential to resolve the competition in the case of  EXIST. Merchant does not address the span-relatedness of right-branching nodes within a structural hierarchy of this kind, but it is clear that Hon0 is more local to v0 than Neg0, and hence the Neg0-v0 span is interrupted by the Hon0 node in (48). If anything forms a span with v0 to condition the root, it is Hon0. Consequently, Merchant’s Span Adjacency Hypothesis can correctly predict the choice of the honorific allomorph kyeysi- in this context, since the conditioner of the negative allomorph eps- is not span-adjacent to the root.

EXIST. Merchant does not address the span-relatedness of right-branching nodes within a structural hierarchy of this kind, but it is clear that Hon0 is more local to v0 than Neg0, and hence the Neg0-v0 span is interrupted by the Hon0 node in (48). If anything forms a span with v0 to condition the root, it is Hon0. Consequently, Merchant’s Span Adjacency Hypothesis can correctly predict the choice of the honorific allomorph kyeysi- in this context, since the conditioner of the negative allomorph eps- is not span-adjacent to the root.

Unfortunately, the Span Adjacency Hypothesis runs into insurmountable problems when confronted with the interaction of honorification and negation in the suppletive negative verb  KNOW. As illustrated in Sect. 3.2.1 above,

KNOW. As illustrated in Sect. 3.2.1 above,  KNOW only has two forms, the negative form and the elsewhere form. Consider Merchant’s prose description of the Span Adjacency Hypothesis:

KNOW only has two forms, the negative form and the elsewhere form. Consider Merchant’s prose description of the Span Adjacency Hypothesis:

“This hypothesis permits nonadjacent heads and their features to participate in the conditioning of an allomorph, but requires that such nonadjacent heads (or their features) form a span with heads (or their features), up to and including the head that is adjacent to the conditioned form.” (2015:294)

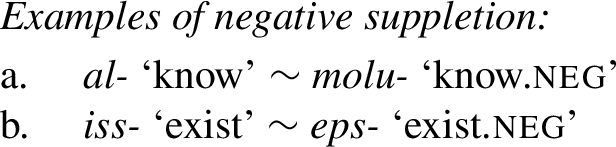

The important case here is that of molu- ‘know.neg’, which must occur in any environment involving short-form negation, with or without an Hon0 terminal node in the structure. When Hon0 co-occurs with short-form Neg0, the verb takes its negative form and Hon0 is spelled-out with its regular exponent -si, even though Hon0 intervenes between Neg0 and  KNOW in the span.

KNOW in the span.

-

(53)

To account for this pattern, Merchant would have to assume that Neg0 is more local to the verb root than Hon0 (as in Chung 2009). However, that assumption would make the incorrect prediction for the verb  EXIST, where honorific suppletion blocks negative suppletion, and run into the inverse problem with honorific suppletive verbs like

EXIST, where honorific suppletion blocks negative suppletion, and run into the inverse problem with honorific suppletive verbs like  SLEEP, where short-form negation receives its regular allomorph an(i) = but does not block the occurrence of the honorific suppletive root in honorific contexts. We conclude that the combined evidence from the patterns of exponence for

SLEEP, where short-form negation receives its regular allomorph an(i) = but does not block the occurrence of the honorific suppletive root in honorific contexts. We conclude that the combined evidence from the patterns of exponence for  KNOW and

KNOW and  EXIST in honorific contexts is fatal to the case for Span Adjacency.Footnote 33

EXIST in honorific contexts is fatal to the case for Span Adjacency.Footnote 33

Instead, a new proposal regarding allomorph selection is needed, one which will not rule out negative conditioning across Hon0 when there is no honorific root allomorph at stake, thus permitting the derivation of (48) with  KNOW, but which will block negative conditioning when a negative root allomorph is at stake, thus choosing (52a) over (52b) with

KNOW, but which will block negative conditioning when a negative root allomorph is at stake, thus choosing (52a) over (52b) with  EXIST.

EXIST.

We propose to relate the blocking effect of Hon0 to the root-outward nature of the Vocabulary Insertion process (Bobaljik 2000). We hypothesize that the search for conditioning features within the complex X0 domain operates root-outward also. At the point when forms are competing to realize the root in a negative, honorific context, both eps- and kyeysi- are equally specified. If the search for conditioning features proceeds incrementally from the root, the honorific form kyeysi- will be activated first and hence inserted first. This bleeds the insertion of any competing allomorph conditioned by any single more distant feature in the complex X0.Footnote 34 However, if Hon0 is not present in the structure (as in (41) above), the search continues to the edge of the X0 domain, eventually finding Neg0 and triggering the insertion of eps-. If the X0 domain is exhausted and no conditioning feature is found, the elsewhere form iss- is inserted.

In the case of  KNOW, this procedure correctly results in the insertion of suppletive molu- even when an honorific feature is present, since Hon0 is not relevant to either of the allomorphs of

KNOW, this procedure correctly results in the insertion of suppletive molu- even when an honorific feature is present, since Hon0 is not relevant to either of the allomorphs of  KNOW, as illustrated in (54). The choice of allomorph for

KNOW, as illustrated in (54). The choice of allomorph for  KNOW is determined by the Vocabulary Insertion rules in (43), repeated in (55).

KNOW is determined by the Vocabulary Insertion rules in (43), repeated in (55).

-

(54)

-

(55)

The search domain must consist of the entire X0 even when a more local terminal is independently realized. No ‘pruning’ of intervening null X0 nodes is necessary or possible in this case, contra Embick (2010); see also Merchant (2015) for the same point regarding English ain’t.

To summarize: The insertion mechanism has to see the entire complex X0 head, since either Neg0 or Hon0 can condition the insertion of a special root form. However, when two forms compete that are each conditioned by a single feature, the insertion mechanism is triggered by the most local conditioning feature. We summarize these two results in the following hypotheses concerning allomorph selection. The first is a restatement of Bobaljik’s (2012) locality principle, here given a name, the Complex Head Accessibility Domain (56). The second is the novel observation made possible by the unique constellation of Korean facts, namely that hierarchical locality considerations give preference to more local features over more distant ones. We term this latter principle the Local Allomorph Selection Theorem (57).

-

(56)

The Complex Head Accessibility Domain (Bobaljik 2012):

Vocabulary Items can only be conditioned by features contained within a complex X0 head, not by features across an XP boundary.

-

(57)

Local Allomorph Selection Theorem:

If two vocabulary items are in competition within an X0 domain and are equally specified with respect to the Subset Principle, the item conditioned by the more hierarchically local feature blocks the item conditioned by the less local feature.

The role of the Local Allomorph Selection Theorem has not been previously recognized, though it is a very natural hypothesis given the standard inside-out view of vocabulary insertion (Bobaljik 2000).Footnote 35 This principle then joins the recognized competition-resolving principles from previous work, such as the Subset Principle, which orders more specific competitors before less specific ones (Halle 1997; Kiparsky 1973), and markedness considerations, which give preference to VIs realizing marked feature types over less marked ones (Moskal 2014; Noyer 1992, 1997).

The overall moral is that the Korean facts show that the hierarchical properties of the morphosyntactic structure being realized are important in determining the winning candidate.

4 The morphological structure of suppletive verbs: po-constructions and reanalysis

We have exhibited two cases in which constructions that include multiple verbs permit or require multiple exponence of honorification, namely verb-copy constructions and long-form negation. We have proposed that on each phase-based Spell-Out cycle, a node-sprouting operation applies. When there are multiple verbal predicates in distinct phases, this yields multiple Hon0 nodes in a single clause.

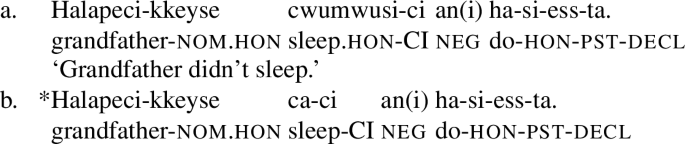

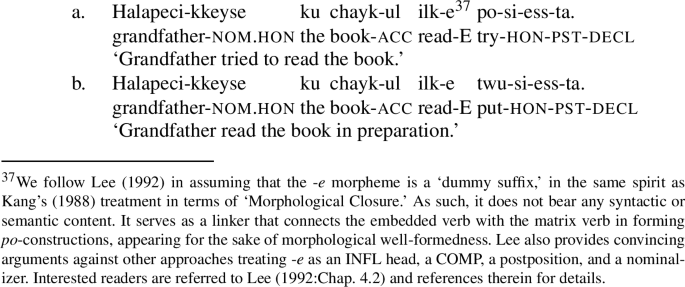

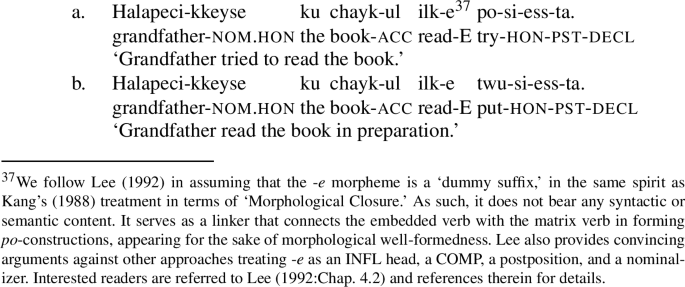

However, we have not considered another family of multiple-verb constructions first mentioned in the honorification literature in Yun (1993). These constructions involve a main lexical verb suffixed with -e followed by an inflected matrix verb, either po- ‘try’, cwu- ‘give’, twu- ‘put’, chiwu- ‘clean’. We give two examples in (58) below. We pretheoretically call these po-constructions for convenience.

-

(58)

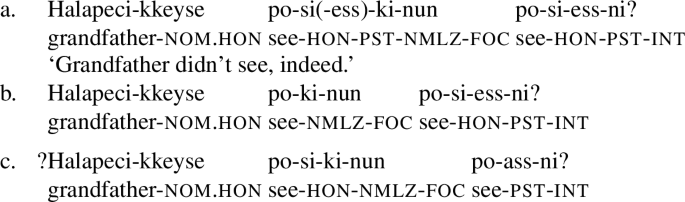

First, we demonstrate that these constructions provide evidence against analyzing the -si at the end of many suppletive verb stems as a regular exponent of Hon0, instead supporting a monomorphemic, single-exponent view of such vocabulary items, contra Chung (2009). We propose that honorific po-constructions involve verbal head-movement from the embedded clause to the matrix clause. This locates the entire complex construction in a single phasal spell-out domain and rules out multiple occurrences of Hon0, since the Hon0-sprouting rule applies but once per phase. We then go on to address the implications of these findings.

4.1 Reanalysis of -si in suppletive vocabulary items

It has likely not escaped the reader’s attention that the suppletive honorific vocabulary items in (44) above appear to overlook a morphological generalization: all suppletive honorific forms end in -si:

-

(59)

This overlap between the regular honorific exponent -si and suppletive honorific forms suggests the possibility that the suppletive forms are actually multimorphemic, i.e., contain both a bound root exponent (e.g., cwumwu-) and an exponent of Hon0, -si. The dependence between the form cwumwu- and the suffix -si would be explained by the morphological conditioning environment required for the insertion of cwumwu-: since cwumwu- is only inserted in the context of an Hon0 node, it will only appear adjacent to the -si exponent that realizes Hon0. This is the approach taken by Chung (2009).

However, we can see that this tempting idea runs into difficulties when the distribution of regular -si is examined in the context of po-constructions. In (54) above, -si occurs on the inflected main verb. Sells (1995:292–293) pointed out that -si may not be marked on the embedded verb suffixed with -e, as shown in (60). In this regard, po-constructions are strikingly different from the other multi-verbal constructions discussed above, in which -si could appear twice.

-

(60)

If the -si of suppletive verb forms like cwumwusi- ‘sleep.hon’ were the regular honorific exponent, then we expect it to have the same distribution as regular Hon0 in (55) and (60) above, i.e., we would expect -si to be forbidden in the complement verb of a po-construction, even when that complement verb is suppletive. If the -si of capswusi- is regular -si, the verb should surface as plain capswu- in an honorific po-construction. In fact, this is ungrammatical, as illustrated in (61) below. The embedded suppletive verb must surface as capswusi-, not capswu-.

-

(61)

This shows that the -si of suppletive verb stems is different from regular honorific -si.

This pattern is also reflected in the fact that the -si of suppletive verb stems is not optional in any of the contexts where regular -si is optional, for example in long-form negation (62) and in verb-copy constructions (63).

-

(62)

-

(63)

Since the distributions of regular -si and the -si of suppletive verb forms are distinct, we conclude that the verb stem of suppletive verbs has undergone reanalysis such that the string -si simply forms part of the root exponent. This idea is captured in our analysis by the vocabulary items we proposed in (44) above, which include -si as part of the exponent of the root.

This in turn means that in regular matrix clauses involving these suppletive verbs, the Hon0 terminal node must have a zero exponent, conditioned by the suppletive root. This zero exponent will block the realization of the elsewhere exponent -si, preventing the appearance of *cwumsusi-si-, etc. The final set of exponents for Hon0 in our analysis are given in (64) below.

-

(64)

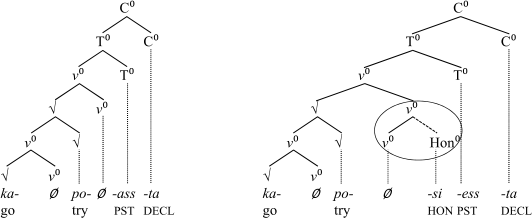

4.2 Head-movement in po-constructions

What accounts for the impossibility of Hon0 on the embedded verb of po-constructions? We hypothesize that the entire constituent V-e po-ass-ta ‘V-E try-PST-DECL’ forms a single complex head created by head movement, and that the interaction of the Hon0-sprouting rule with the complex head accounts for this pattern. We follow Lee (1992), who argues that po-constructions are formed by means of head-movement. Lee (1992:Chap. 4.3.3) shows that po-constructions do not allow insertion of the morpheme -se (meaning ‘by means of’ or ‘and then’) or an adverb, between the embedded verb and the matrix verb.Footnote 36 Also, when po-constructions are negated, only a wide scope interpretation is available, in which the matrix verb is negated; no narrow scope interpretation is available in which only the embedded verb is negated. Lee takes both of these facts to show that two verbs comprising the po-construction form a single X0 unit.

We propose that the embedded verb, marked by -e, head-moves upward to adjoin to the matrix verb po-, which then itself head-moves to the matrix T0 and C0 nodes. The entire complex is spelled-out on the final cycle, in which the Hon0-sprouting rule in (26) above applies to it. We suggest that such rules apply once per phase, and then are satisfied (much like Richards’ 1997 Principle of Minimal Compliance; see also Lomashvili and Harley 2011 concerning Georgian complex verbal forms). The node-sprouting rule attaches an Hon0 node to the least embedded v0 it encounters in the complex form—the matrix v0 associated with po- itself. Other v0 elements in these forms do not sprout an Hon0 node, since they all are contained within the same complex head.

-

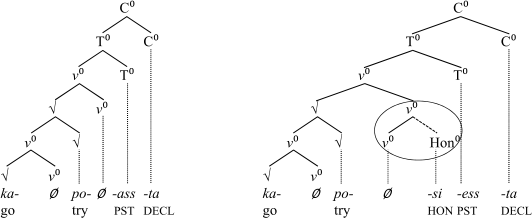

(65)

a. Non-honorific po-construction: b. Honorific po-construction:

Note that if long-form negation is embedded under po-, honorification cannot be applied to the dummy ha-verb that forms part of po-’s verbal complex, but it can appear on the main verb stranded below, since, as in the basic analysis of long-form negation presented in Sect. 2.3.2. This is predicted, because that verb occurs in a separate spell-out domain which is subject to its own application of the Hon0-sprouting rule, with phasal boundaries indicated by right brackets.

-

(66)