Abstract

In many languages with ergative morphology, transitive subjects (i.e. ergatives) are unable to undergo A’-extraction. This extraction asymmetry is a common hallmark of “syntactic ergativity,” and is found in a range of typologically diverse languages (see e.g. Deal 2016; Polinsky 2017, and works cited there). In Kaqchikel, the A’-extraction of transitive subjects requires a special verb form, known in Mayanist literature as Agent Focus (AF). In a recent paper, Erlewine (2016) argues that the restriction on A’-extracting transitive subjects in Kaqchikel is the result of an Anti-Locality effect: transitive subjects are not permitted to extract because they are too close to C0. This analysis relies crucially on Erlewine’s proposal that transitive subjects undergo movement to Spec,IP while intransitive subjects remain low. For Erlewine, this derives the fact that transitive (ergative) subjects, but not intransitive (absolutive) subjects are subject to extraction restrictions. Furthermore, it makes the strong prediction that phrasal material intervening between IP and CP should obviate the need for AF in clauses with subject extraction. In this paper, we argue against the Anti-Locality analysis of ergative A’-extraction restrictions along two lines. First, we raise concerns with the proposal that transitive, but not intransitive subjects, move to Spec,IP. Our second, and main goal, is to show that there is variation in whether AF is observed in configurations with intervening phrasal material, with a primary focus on intervening adverbs. We propose an alternative account for the variation in whether AF is observed in the presence of adverbs and discuss consequences for accounts of ergative extraction asymmetries more generally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

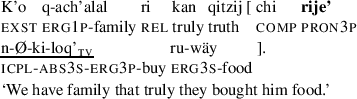

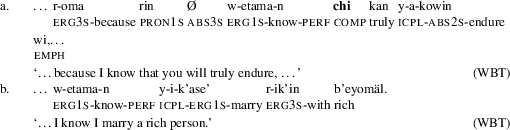

Kaqchikel, like many Mayan languages, constrains the A’-extraction of transitive subjects from a normal transitive clause. Consider, for instance, example (1), where A’-extraction of the transitive subject is simply banned.Footnote 1 To A’-extract the transitive subject—for focus, relativization, and wh-questions—the Agent Focus (AF) construction is required, as illustrated in (2). Here and throughout, we underline verb stems and indicate with subscripts whether the stem is in its regular transitive form (‘tv’), or in the Agent Focus form (‘af’), each described in more detail below.

-

(1)

-

(2)

While the alternation between transitive and AF forms raises a series of analytical puzzles, a central question is: what is it about transitive (ergative) subjects that makes them difficult or impossible to extract? In recent work, Erlewine (2016) proposes that the restriction on transitive-subject extraction in Kaqchikel is the result of an Anti-Locality effect.Footnote 2 The core idea of the proposal is that A’-movement should not be too local, as in (3).

-

(3)

Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality (Erlewine 2016: 2):

A’-movement of a phrase from the Specifier of XP must cross a maximal projection other than XP.

Erlewine proposes that transitive subjects in Kaqchikel must raise to Spec,IP, which he suggests is the locus of ergative agreement. This movement places transitive subjects in a position too close to undergo further A’-movement to Spec,CP, per (3). According to Erlewine, Agent Focus constructions like (2) permit A’-extraction because in these constructions, the subject extracts directly from its base position in Spec, vP; Anti-Locality is not violated, and since the subject does not move through IP, the lack of ergative agreement in AF forms is explained (compare (1) and (2)). The first part of this paper challenges the proposal that transitive subjects move to Spec,IP, a critical ingredient for the account in (3).

While the evidence against subjects raising to Spec,IP already undermines the Anti-Locality account, we also aim to provide an alternative explanation of the types of constructions that Erlewine uses to motivate Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality in the first place. Empirical support for (3) in Erlewine (2016) comes from sentences like those in (4), in which a preverbal adverb appears to permit transitive subject extraction without the use of AF.Footnote 3 Compare extraction of the transitive subject from a transitive stem form in (4) with the ungrammatical adverb-less form in (1) above.

-

(4)

If movement over adverbials truly obviated the need for AF, it would provide an argument that A’-movement in Kaqchikel is sensitive to the number of maximal projections between the origin and landing site of a given movement operation. We will show, based on new data from both corpora and elicitation, that the generalization that adverbials obviate the need for AF is incorrect.

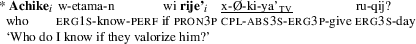

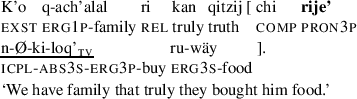

First, as Erlewine (fn. 11) notes, not all intervening adverbs have the effect seen in (4). While this is already troubling for Anti-Locality, our new data concerning the interaction of AF and adverbials provides a second, stronger challenge to the generalization that intervening adverbs obviate the need for AF. In particular, we show that even the same adverb may vary in whether or not it permits extraction without AF, shown in the corpus examples involving relativization in (5) and (6).Footnote 4 While we make extensive use of naturally occurring data, every corpus example presented here has been confirmed as grammatical by elicitation work with native speakers.Footnote 5

-

(5)

-

(6)

Alternations like these are unexpected under an Anti-Locality account. If the movement of the transitive subject over kan qitzij in (6) is long-distance enough to permit a canonical transitive clause, then the movement of the transitive subject in (5) should also be sufficiently long.

These data not only challenge the core empirical generalization supporting (3) in Kaqchikel, but they also raise a puzzle of their own: What does account for the fact that adverbials appear to only sometimes obviate the need for AF in clauses that otherwise look as if they have subjects that have undergone A’-extraction? We argue that despite their surface similarity, the classes of examples exemplified by (5) and (6) have radically different structures, schematized for relative clauses in (7) and (8).

-

(7)

-

(8)

We propose that the extraction examples without AF, like (4) and (6) above, are actually biclausal, as in (8). In these forms the adverb acts as a matrix predicate embedding a lower clause which contains a resumptive pronoun. These examples contain no actual movement of the subject, and AF morphology is therefore not predicted. In contrast, examples like (5), schematized in (7), are monoclausal with true A’-movement of the subject over the adverb. Here AF morphology appears because it is necessary in Kaqchikel for the extraction of ergative subjects, and for reasons that do not make reference to Anti-Locality (see e.g. Aissen 2011, 2017; Coon and Henderson 2011; Coon et al. 2014). Because the non-bold-faced items in (8) either are, or may be, unpronounced, the two constructions can appear very similar on the surface.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents background on the Agent Focus construction and the Anti-Locality account. Section 3 concerns the location of subjects in Mayan, and argues against Erlewine’s proposal that transitive subjects move to Spec,IP. In Sect. 4 we examine purported Anti-Locality effects with adverbs. Here we present new empirical evidence that adverbs do not uniformly obviate the need for AF in Kaqchikel. Section 5 presents our analysis of examples like (4) and (6) in terms of clausal embedding and resumption. In Sect. 6 we briefly review multiple wh-extraction and conclude.

Before turning to AF, we briefly clarify the intended scope of this paper. This article does not provide a full account of either (i) the exact mechanism by which transitive (ergative) subjects are restricted from extraction, or (ii) how Agent Focus obviates this restriction. While we discuss some alternatives to Anti-Locality from existing literature below, the main goal of this reply article is to demonstrate that an Anti-Locality account of ergative extraction restrictions is unsupported, both in terms of evidence about the nature of subjects and agreement in the language, as well as by the adverbial constructions discussed below. We conclude that some other analysis of syntactic ergativity is needed. With respect to the adverb alternations foreshadowed in (5) and (6) above, we provide an alternative, empirically-supported account of the adverb construction which appears to evade syntactic ergativity. Further work will be needed to fully understand the details of the choice of AF versus biclausal forms in (7) and (8), as well as which adverbs are subject to this variation. We discuss these issues further below.

2 AF and the Anti-Locality account

This section begins in Sect. 2.1 with some brief background information on Kaqchikel, the extraction restriction on transitive subjects, and the Agent Focus construction found in a number of Mayan languages. In 2.2 we review the relevant details of Erlewine’s proposal.

2.1 Kaqchikel Agent Focus

Kaqchikel transitive and intransitive examples are shown in (9a) and (9b).

-

(9)

As shown here, overt nominal arguments appear post-verbally in non-extraction contexts. Like other Mayan languages, Kaqchikel has two sets of person markers used to cross-reference core arguments on predicates, labelled “Set A” (ergative/possessive) and “Set B” (absolutive) in Mayan linguistics. Preconsonantal and prevocalic allomorphs of each series are shown in (10) and (11). The ergative morphemes in (10) cross-reference transitive subjects (9a), while Set B absolutive morphemes cross-reference transitive objects (9a) and intransitive subjects (9b). Note that third person singular absolutive is null, a fact which will be relevant below.Footnote 6

-

(10)

ergative (“Set A”)

sg

pl

1st

in- / inw-

qa- / q-

2nd

a- / aw-

i- / iw-

3rd

(r)u- / r-

ki- / k-

-

(11)

absolutive (“Set B”)

sg

pl

1st

i- / in-

oj-

2nd

a- / at-

ix-

3rd

Ø

e- / e’-

Across the Mayan family, arguments appear in preverbal position for topic, focus, relativization and wh-questions (England 1991; Aissen 1992). While all Mayan languages show an ergative-absolutive system of morphological marking, only a subset of these languages restrict the A’-extraction of ergative subjects (Tada 1993; Stiebels 2006; Coon et al. 2014; Aissen 2017), a hallmark of what has been called “syntactic ergativity” (Polinsky 2017; Deal 2016).

As noted at the outset, this restriction is observed in Kaqchikel: transitive objects and intransitive subjects extract with no other change to the clause, as shown in the object-extraction example in (12a), but extraction of a transitive (ergative) subject is ungrammatical, as in (12b).

-

(12)

Instead, in order to extract a transitive subject, the Agent Focus (AF) construction must be used, repeated in (13):

-

(13)

While Agent Focus constructions are common across the Mayan family, there is also variability in properties of these constructions; see Stiebels (2006), Aissen (2011), Aissen (2017), Henderson et al. (2013), Coon et al. (2014) and works cited there for discussion. As shown in (13), the AF verb in Kaqchikel bears the suffix -o or -on and has only one agreement morpheme, drawn from the set of absolutive markers in (11); ergative marking does not appear. Despite the fact that the verb takes only a single person/number marker, Agent Focus constructions are not antipassives. First, unlike antipassives, the AF form is only possible when the transitive subject undergoes A’-movement. Second, the object—ri äk’ in (13)—remains a direct argument of the verb; it is not made oblique, as in antipassive constructions. Either the subject or object argument can control agreement depending on a person/number hierarchy (see Preminger 2014).

2.2 Anti-locality

Any successful account of the ergative extraction restriction and Agent Focus construction should answer (at least) two questions, summarized in (14).

-

(14)

AF Desiderata

-

1.

What prevents a transitive subject (but not an object or intransitive subject) from undergoing A’-movement out of a canonical transitive clause?

-

2.

Why is extraction of the transitive subject possible when the verb is in the AF form?

-

1.

As foreshadowed above, Erlewine (2016) accounts for these properties as follows. First, transitive subjects in all regular Kaqchikel transitive clauses must move to Spec,IP. This position is too close to CP, per Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality in (3) above, preventing the transitive subjects from then undergoing A’-movement. Intransitive subjects and transitive objects, on the other hand, do not move to Spec,IP and are thus free to extract. The AF form is special in that it permits transitive subjects to extract directly from their base position in Spec, vP.

For Erlewine, the lack of ergative morphology in the AF form reflects the fact that the subject does not move to Spec,IP. His account posits that the agreement probes responsible for the realization of the ergative and absolutive morphemes in (10) and (11) above are located on Infl0: the absolutive probe is obligatory (i.e. present in all clauses), accounting for the fact that absolutive marking is found in both transitive and intransitive clauses. The ergative probe is active only in transitive clauses; it triggers ergative agreement with the subject and also has an EPP feature which requires that the transitive subject move to Spec,IP (see also Bobaljik 1993 on Infl0 as the source of ergative). The presence of the additional ergative probe in transitives is required by a constraint which gives preference to derivations which realize as much agreement as possible (Woolford 2003). Erlewine’s system is summarized in (15).

-

(15)

In the following section we draw on existing Mayan literature to discuss first the lack of evidence that transitive subjects move to Spec,IP, and second problems with the proposal that ergative agreement originates in Infl0.

3 Ergative agreement and the location of subjects

Erlewine’s (2016) account of Kaqchikel contrasts with work on Mayan languages which takes transitive subjects to remain, and trigger ergative agreement, in situ (e.g. Aissen 1992; Coon 2013, 2017; AnderBois and Armstrong 2014). In fact, a number of analyses of syntactic ergativity—both within and outside of the Mayan family—are based on the premise that ergative subjects are licensed low in the derivation, discussed below. In Sect. 3.1 we begin by briefly reviewing these case-based approaches to ergative A’-extraction restrictions. We show how case-based and Anti-Locality accounts make different predictions about the nature of ergative agreement, and in Sect. 3.2 we raise concerns with the proposal that ergative subjects in Kaqchikel raise to Spec,IP, a crucial ingredient of the Anti-Locality account.

3.1 A case-based account of extraction asymmetries

Recent analyses of Agent Focus in Mayan attribute the ban on extracting ergatives to a problem with how arguments are licensed or assigned abstract case in the derivation (Ordóñez 1995; Coon et al. 2014; Assmann et al. 2015). Though these case-based analyses differ from one another in the details, the core problem with extracting transitive subjects is argued to be the configuration of licensing: transitive subjects are licensed by a low functional head v 0 or Voice0, and finite Infl0 must license the transitive object (see also Bok-Bennema 1991; Campana 1992; Johns 1992; Bittner and Hale 1996, and discussion in Deal 2016; on low licensing of ergative arguments see also Woolford 1997; Aldridge 2004; Legate 2008, 2017). The proposed relationship between arguments and the heads which license them is schematized in (16).

-

(16)

The case-based accounts of Coon et al. (2014) and Assmann et al. (2015) propose that the licensing configuration in (16) is the cause of the ban on extracting ergative subjects in Mayan (see also Campana 1992 and Bittner and Hale 1996 for work on unrelated languages). In Coon et al.’s approach, for example, the transitive object must raise above the subject in order to be licensed by Infl0 (i.e. assigned abstract nominative case), trapping the subject in situ. In Assmann et al.’s account, an ergative subject moving through the left edge of the clause robs the available case from Infl0, leaving the object unlicensed. Though the implementations differ, the core idea is the transitive object must be licensed by a probe above the subject, creating a restriction on extracting the subject.Footnote 7

Note that the case-based and Anti-Locality accounts differ critically in two related domains: (i) the source of licensing/agreement for the ergative subject, and (ii) the nature of the extraction problem. In the Anti-Locality account, ergative comes from Infl0, while in case-based accounts the source of ergative is low. The extraction problem arises from the position of the ergative subject in the Anti-Locality account, but from a licensing configuration in the case-based account. We review the evidence from Mayan below.

3.2 Licensing and ergative agreement

Following previous work on Mayan languages, we take clause-initial TAM (tense, aspect, mood) markers to instantiate Infl0 (Aissen 1992). Under the configuration in (16) above, ergative licensing/agreement should be available so long as a transitive vP layer is present (we do not discuss possible separation of Voice0 and v 0 heads for simplicity). In the structure assumed in the Anti-Locality account, however, ergative should only be possible if finite Infl0 is present—it should be unavailable in nonfinite (TAM-less) embedded clauses.

While ergative is clearly available in nonfinite embedded clauses in some Mayan languages (see e.g. Vázquez Álvarez 2013; Coon 2017, and discussion in Coon et al. 2014), the Kaqchikel facts are complicated. In Kaqchikel, as in many other Mayan languages (see e.g. England 2013), transitives may not be embedded in nonfinite contexts. In order to be embedded, a transitive verb must first be passivized, as in (17a), or antipassivized, as in (17b).

-

(17)

These facts are discussed in detail by Imanishi (2014), who concludes that the source of absolutive in Kaqchikel is finite Infl0, accounting for the impossibility of absolutives in nonfinite embedded clauses. This is compatible with both case-based and Anti-Locality accounts.

Note that in (17a) the remaining embedded argument is coindexed with ergative agreement.Footnote 8 This initially appears problematic for an account in which ergative is assigned by finite Infl0 (since the embedded nonfinite clause would lack this head). However, given the ergative∼possessive morphological syncretism found throughout the Mayan family, and the nominal morphology on the embedded form, one might reasonably argue that the ergative marking in (17a) is possessor agreement, and thus not a problem for the Anti-Locality account. Though the availability of ergative agreement in non-finite embedded contexts in other Mayan languages may lend support to the case-based account, the Kaqchikel facts are at best inconclusive.

More problematic for the Anti-Locality account are the environments in Mayan languages in which ergative agreement co-indexes the argument which has apparently been A’-extracted, even in the absence of intervening material. One such environment is shown in (18). In contexts in which the subject binds into the object—as in reflexive (18a) and so-called “extended reflexive” constructions (18b)—we find the A’-extracted subject triggering ergative agreement, and no AF-marking on the verb (see also Mondloch 1981 and Coon and Henderson 2011 on K’ichee’; Hou 2013 on Chuj; Coon et al. 2014 on Q’anjob’al). Examples like these demonstrate that the connection between ergative agreement and the ergative extraction restriction is indirect.

-

(18)

An ergative-agreeing agent may also extract from constructions in which the transitive verb takes a CP complement. This is shown in (19), where the relativized subject of b’ij ‘say’ controls ergative agreement in the presence of a CP complement. As in (18), extraction of the ergative-agreeing subject occurs in the absence of AF marking.

-

(19)

We see a similar effect with light verb constructions. Verbs borrowed from Spanish, like manifestar ‘protest’ in (20), may not directly inflect as predicates, but instead appear as complements of the transitive verb b’än ‘do’. Subjects extracted from this construction can again still trigger ergative agreement, as in (20).Footnote 9

-

(20)

These types of examples highlight the fact that there is no general ban on ergative agreement in agent-extraction environments. Recall that in Erlewine’s Anti-Locality account, it is the ergative probe on Infl0 which requires the transitive subject to move to Spec,IP; ergative agreement and the high position of the ergative subject are thus directly linked. The facts above show that any account which ties the inability for subjects to extract to ergative agreement will require modification. It is unclear, however, how such modification would be achieved. The Anti-Locality account requires transitive—but not intransitive—subjects occupy Spec,IP. Since neither word order (fn. 7), nor licensing provides independent evidence for a connection between transitive subjects and Infl0, the connection to ergative agreement is crucial for Erlewine (2016). Furthermore, the Anti-Locality account would require further modification in order to explain why AF is not required in these examples, since apparently no intervening projections are present.

In contrast, proposals for Mayan extraction restrictions in which the object’s need for case-licensing blocks the extraction of transitive subjects (e.g. Coon et al. 2014; Assmann et al. 2015) have the clear potential to explain these patterns. In all three cases above, the object or complement of the transitive verb is somehow special—reflexive (18a), extended reflexive (18b), an embedded CP (19), or the complement in a light-verb construction (20)—and so might not be case-licensed through normal means. It is exactly this type of alternation which is expected to govern the possibility of agent extraction in the case-based proposals described above.Footnote 10

4 Adverbs and Anti-Locality effects

Having reviewed problems with (i) the proposal that ergative subjects raise to Spec,IP (a necessary ingredient of an Anti-Locality account), and (ii) the direct connection between ergative agreement and ergative extraction restrictions, we now turn to one of the original empirical motivations behind Erlewine’s proposal. Recall that an important argument in favor of the Anti-Locality analysis is that intervening adverbial elements appear to obviate the need for AF, as in (21).

-

(21)

If the Agent Focus construction allows a transitive subject to move when its movement would otherwise be too short, then the adverbial kan qitzij in (21) appears to fix the locality problem by adding a maximal projection between IP and CP; movement of the ergative subject from Spec,IP to Spec,CP would thus not violate Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality in (3).

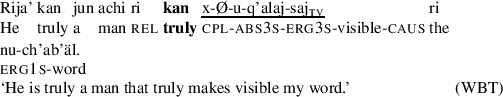

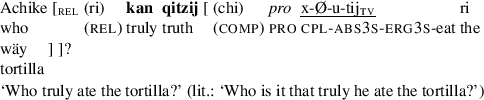

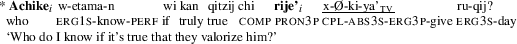

As noted above, however, the data are more complex: sometimes an intervening adverbial obviates the need for AF and sometimes it does not. Consider the following near-minimal pair in (22) and (23), repeated from above. Here we have the same relative clause complementizer, adverb, and verb; yet one verbs bears AF morphology, while the other does not.

-

(22)

-

(23)

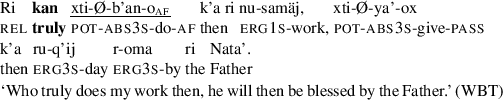

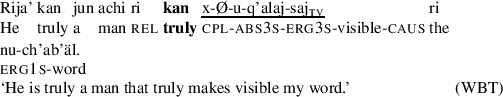

This is not an isolated example. We similarly find variation in attested examples with the adverbial kan ‘truly’ appearing alone. In (24) and (25) we see transitive stem forms even though the transitive subject has been purportedly extracted, as predicted under the Anti-Locality analysis.

-

(24)

-

(25)

In contrast, the examples in (26) and (27) show AF-morphology appearing with a relativized ergative subject, even in the presence of the same intervening adverb, kan.

-

(26)

-

(27)

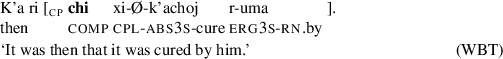

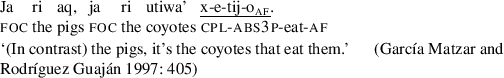

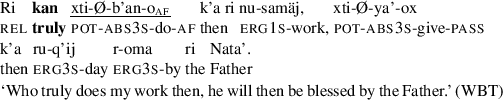

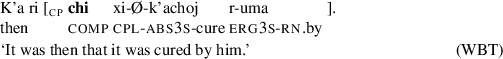

We see the same pattern with other adverbials. For instance, consider the behavior of k’a ri ‘then’ or ‘after’. The examples in (28) and (29) show that k’a ri can obviate the need for AF morphology, as expected under the Anti-Locality account.

-

(28)

-

(29)

Once again, though, it is equally possible to find examples where AF is present when a transitive subject appears to have A’-extracted over k’a ri, which should not be possible under an Anti-Locality account.

-

(30)

-

(31)

The same facts can be generated for other adverbials, but even these raise concerns for Anti-Locality. The Anti-Locality account predicts that Agent Focus should not appear when a maximal projection intervenes between the verb and a subject’s A’-landing site. While Erlewine (2016, fn. 11) acknowledges that some adverbs consistently do not obviate the need for AF, here we have shown that the problem is more severe: even the same adverb shows variability in whether or not AF is present in contexts of ergative A’-extraction.

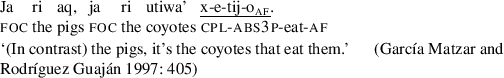

Finally, though not discussed in Erlewine (2016), sentential negation does not obviate the need for Agent Focus in Kaqchikel, despite the fact that negation appears to sit high in the clause. This is shown in examples (32)–(33).

-

(32)

-

(33)

This contrasts with the behavior of negation in some languages which show anti-agreement effects, in which A’-movement alters or suppresses canonical argument agreement (for example some varieties of Berber; Ouhalla 1993). We suggest that this casts further doubt on efforts to collapse ergative extraction restrictions and anti-agreement as the same type of effect (see also Baier 2017), a point to which we return below. The difference in behavior between adverbs (which sometimes obviate the need for AF) and negation (which never does) receives a natural explanation under the account we propose in the next section: adverbs may serve as predicates, while negation may not.

5 Adverbs and embedding

Given that (i) interveners do not uniformly block AF (Sect. 4), and (ii) there are independent problems with the crucial ingredients of an Anti-Locality account (Sect. 3), we propose a retreat to one of the previously-defended accounts of Mayan Agent Focus which do not rely on Anti-Locality (e.g. Ordóñez 1995; Aissen 2011; Coon and Henderson 2011; Coon et al. 2014; Assmann et al. 2015, discussed in Sect. 3.1 above). We do not review the details of these proposals here, nor do we endorse any particular account (see Aissen 2017 for discussion), but instead focus on explaining the examples raised by Erlewine (2016) and enumerated above in which adverbs appear to obviate the need for AF (e.g. (23), (24), (25), (28), (29)).

In our proposal, these examples do not involve A’-extraction and are thus not predicted to invoke the need for Agent Focus. We propose that the AF-less adverbial constructions—in which an ergative argument appears to A’-extract from a transitive clause—are characterized by the following properties: (i) the adverb is the predicate of a copular clause, (ii) the adverb embeds a CP complement, and (iii) the purported subject trace is actually a bound (resumptive) null pronoun, pro. We call this the Adverbial Predication (APred) construction. The core goal of this section is to establish the existence of the APred construction and to compare it to the AF construction. The two structures are schematized in (34) and (35), repeated from (7) and (8) above, for the case of subject relatives (though it is generalizable to other A’-constructions, discussed briefly below).

-

(34)

-

(35)

With no A’-movement, the APred construction is correctly predicted to not show AF. Moreover, because Kaqchikel has a null copula, null 3rd person singular absolutive agreement, null pro, and null complementizers, the APred construction is predicted to be potentially string-equivalent to a mono-clausal structure with A’-movement over an intervening adverb. This can be seen by focusing on the bold-faced expressions in (34) and (35), which are those that are necessarily overt.

The analysis makes three testable predictions. The first two follow from the fact that while often unpronounced, the null complementizers and pronouns in (35) also have an overt form in Kaqchikel, as in other Mayan languages (Armstrong 2009; Coon 2016). We might thus expect to find clauses with overt complementizers or wh-expressions embedded under adverbs in the APred constructions represented in (35). Similarly, based on our proposal that the pro in the lower clause of (35) is resumptive, we should find evidence of overt resumption, but crucially only with transitive (non-AF) verb forms. Finally, under our analysis, variation in AF-marking is correlated with an adverb’s ability to embed a complement clause. This predicts that those adverbs that cannot embed clauses should uniformly occur in AF-marked clauses when the standard conditions on AF are met. We show below that all three of these predictions are borne out.

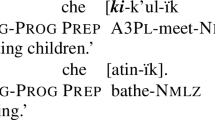

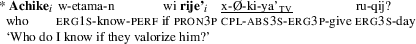

5.1 Overt complementizers

First, note that we find naturally-occurring examples of the adverbs discussed embedding a full CP, as evidenced by wh-words and the complementizer chi. This establishes that Kaqchikel does in fact allow adverbs to embed CPs, exactly as the APred analysis in (35) requires.Footnote 11

-

(37)

-

(38)

As predicted under the APred analysis, we find examples in which these adverbials embed CPs under relative clauses. This is exactly the configuration studied in Sect. 4 where we observed variation in the presence of Agent Focus marking.

-

(39)

-

(40)

-

(41)

If the APred construction is biclausal, as these examples show, and does not canonically involve A’-movement, then we expect that Agent Focus marking is not required. This is confirmed by the fact that we have no examples of overt complementizers in constructions with Agent Focus verb forms in our corpus (of over 400,000 words). Of course, we would like to show that Agent Focus verb forms are, in fact, banned in the biclausal APred construction schematized in (35). We take up this question in the next section, where we show that Agent Focus verb forms are only possible in the APred construction resulting from local A’-movement within the embedded clause. Otherwise, Agent Focus marking is banned in the APred construction, as expected.

In sum, we have shown here that the adverbials that appear to obviate the need for AF may embed clauses, exactly as predicted by the APred account. Moreover, we have a refined prediction that AF should be impossible in the APred construction unless there is local A’-movement within the embedded clause. It is easiest to show that this prediction is borne out by considering cases of overt resumption in the lower clause, which is what we turn to next.

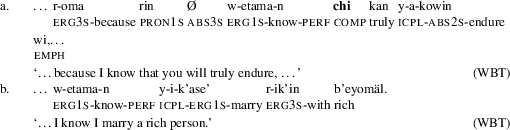

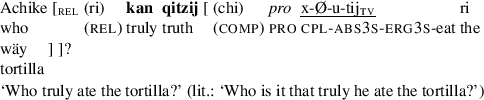

5.2 Resumptive pronouns

We now review evidence for the presence of null resumption in the APred constructions in (35). Kaqchikel, like other Mayan languages, allows all core arguments and possessors to be realized by null pronominals. For instance, in example (42) a covert pro controls ergative agreement on the relational noun -ik’in. Though it would be pragmatically unusual, the pro in (42) could be replaced by the overt third person plural pronoun rije’.

-

(42)

This contrasts with a wh-relative like (43); here the wh-expression, achoj, controls agreement on the relational noun. A gap is left after the relational noun and, as expected, replacing the gap in (43) with a pronoun is ungrammatical.

-

(43)

The fact that Kaqchikel allows null resumption in some environments lends plausibility to the proposal that the APred construction involves a null resumptive pronoun. We can go further, though, and show directly that the APred construction involves resumption. Though pragmatically marked, it is possible to elicit overt resumptive pronouns in APred structures like those in (39)–(41) above. Consider example (44), which is unambiguously an APred construction in virtue of the overt complementizer chi. The fact that it is possible to have an overt pronoun here establishes that the APred construction does not involve a gap (as would be expected in true A’-extraction), but instead has either overt resumption, as in (44), or null pro resumption, as in the attested example (39) above.Footnote 12

-

(44)

Given that Kaqchikel allows a null complementizer and null resumptive pronouns, it is unsurprising that the adverb constructions with and without Agent Focus in (34) and (35) are difficult to distinguish. Recall from (34), however, that we only predict AF to appear in the construction which involves A’-extraction with a gap, not a resumptive pronoun. Examples (45) and (46) with an overt resumptive pronoun and an Agent Focus verb form are judged ungrammatical, as predicted under our account.

-

(45)

-

(46)

In contrast, the minimally different examples in (49) and (50) show that overt resumptive pronouns with transitive verb forms are grammatical, which is expected in a gapless construction like the APred construction.Footnote 13

-

(49)

-

(50)

As alluded to at the end of Sect. 5.1, however, there should be one way to get AF morphology in the embedded clause of the APred construction. Since the APred construction involves an embedded CP, it should be possible to A’-move the resumptive pronoun internally to the embedded clause. This is exactly what we find, as shown in (51). Now, since the resumptive pronoun has undergone A’-movement (indicated in (51) with the focus marker ja), AF is correctly predicted.

-

(51)

To this point, this section has focused on relative clauses, though the same example can be extended to cases of focus and wh-questions, like in (52).

-

(52)

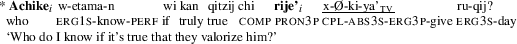

Kaqchikel allows wh-expressions to serve as predicates with relative clause arguments, as shown in the attested examples in (53) and (54).

-

(53)

-

(54)

Once again, though, the relative clause marker ri can be null. This means that a monoclausal wh-construction can be indistinguishable from a biclausal wh-question with a relative clause (i.e. an APred construction). In the latter case, the overt wh-expression does not move out of the lower clause. We propose, then, that examples like (55)—in which ri and chi can be either overt or null—have exactly the kind of relative clause structure we’ve seen above, where there is no movement out of the lower clause, and thus no AF.

-

(55)

Example (55) would then covary with a string-equivalent monoclausal construction with A’-movement over the adverbial, as in (56), triggering AF. Similar facts can be shown for focus constructions, which we do not review here in the interest of space.

-

(56)

5.3 Non-embedding adverbials

Biclausality plays a critical role in the proposed account of variation in AF-marking. Specifically, we propose that constructions in which the transitive subject of a non-AF verb appears to have A’-extracted across an intervening adverb are in fact biclausal resumptive constructions in which no movement of the subject has taken place. The clear prediction then is that those adverbials that cannot embed a complement clause should fail to precipitate variation in AF-marking of the kind seen with adverbs like (kan) qitzij ‘truly’. While fully exploring the syntax of adverbials must wait for future work, preliminary work suggests that this prediction is correct. While adverbials like kan qitzij embed full CP complements, as in (57), other adverbs, like jantäq and jumul in (58) and (59) do not.

-

(57)

-

(58)

-

(59)

Our account correctly predicts the fact that speakers who strongly reject (58) and (59) require AF marking when jantäq and jumul appear in a clause with a preverbal wh-element. Grammatical AF forms with subject extraction are shown in (60a) and (61a). The forms in (60b) and (61b) are only acceptable under an interpretation in which the preverbal element is interpreted as the object; in other words, the APred construction is judged impossible.

-

(60)

-

(61)

While facts like these need to be more deeply explored, they are predicted by our account, which ties variation in AF-marking with certain adverbials to their availability to embed clauses. What we have found in our preliminary investigation is that while there is variation across speakers concerning which adverbials embed clauses, for a given speaker, an adverb’s ability to embed a CP correlates with its ability to appear in an APred construction (i.e. to appear to obviate the need for AF). In particular, there are those adverbials, like (kan) qitzij, which robustly embed clauses and which trigger free variation in the appearance of AF. On the other hand, there are adverbials like jumul which always co-occur with AF-marking in the relevant contexts, and which do not take clausal complements, as our account would predict. We leave for future work whether there is semantic or structural predictability concerning the adverbs that do and do not embed CPs.Footnote 14

5.4 Summary

The data from overt complementizers and resumptive pronouns in this section show that Kaqchikel has exactly the morphological and syntactic resources to support the analysis proposed in (34) and (35) above. First, we saw that certain adverbs in Kaqchikel—namely, the ones that appear to allow extraction without AF—can embed clauses. Moreover, these adverbs can occur in relative clauses, intervening between the NP host of the relative clause and a resumptive pronoun it binds.

Crucially, in clauses which lack AF, we argue that there is no A’-movement of the ergative subject. Instead, these involve a biclausal construction in which an adverb embeds a CP with a resumptive pronoun, which we call the APred construction. The absence of AF in certain constructions with adverbs thus has nothing to do with the locality of extraction; the lack of AF indicates the absence of extraction. The facts are thus compatible with any account in which the A’-extraction of transitive subjects is sufficient for AF (e.g. Aissen 2011; Coon and Henderson 2011; Coon et al. 2014; Assmann et al. 2015). But, because Kaqchikel has null complementizers, a null copula, and null resumptive pronouns, this resumptive construction can appear string-equivalent to a relative clause in which an A’-operator moves over an adverb. It is this equivalence that accounts for the minimal pairs seen in Sect. 4, where adverbs only sometimes appear to block AF.Footnote 15

Finally, this section established an important correct prediction of the analysis. In the presence of overt material disambiguating the APred construction and the canonical A’-movement construction (e.g. an overt complementizer or resumptive pronoun), we no longer see variation in AF-marking. Unambiguous APred constructions do not show AF unless there is A’-movement internal to the clause embedded under the adverbial.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we argued that Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality is not responsible for ergative extraction asymmetries in Kaqchikel. We began by reviewing problems with the proposal that ergative subjects move to Spec,IP in Kaqchikel, a necessary ingredient of Erlewine’s account. Independently of these problems, we showed that the adverbial facts which initially appeared to lend support to an Anti-Locality account are in fact more complicated: not only is there variation in which adverbs appear to permit A’-extraction of ergative subjects without the use of the Agent Focus construction, but even the same adverbial element shows variation as to whether it appears with a transitive or AF verb form in extraction environments. We argued that constructions which appear to allow ergative agent extraction from a transitive clause are in fact biclausal. Because the copula, embedded complementizer, and resumptive pronoun may all be null, this biclausality is not always readily apparent. However, our account was shown to make correct predictions about where possibly-overt elements (complementizers and pronouns) may surface.

This result is important because variation in the appearance of AF in agent-extraction contexts has been noted not just with adverbial interveners, but across a variety of constructions in Mayan languages. In some cases it has been proposed that the AF construction is being gradually lost (e.g. Heaton 2015). In conducting elicitation for this work, we encountered younger speakers who had non-standard AF marking even in clauses without adverbials, in line with Heaton’s observations. That said, our work suggests that some cases of prima facie missing AF marking might be more complicated, and so attrition should be investigated on a construction-by-construction basis.

The idea that anomalous AF-marking should be investigated on a case-by-case basis extends to other constructions Erlewine (2016) uses to argue for an Anti-Locality account of Agent Focus. We have focused here on the argument from adverbials because if, as we have shown, adverbial interveners do not obviate the need for Agent Focus, it becomes difficult to maintain an Anti-Locality account in general. That said, Erlewine (2016) also considers constructions that involve multiple A’-movement, as in the pair of examples shown in (62) and (63). When the subject appears to have moved across the object, the transitive form is used, as in (62). In the reverse configuration, the Agent Focus form is used, as in (63).

-

(62)

-

(63)

While we leave exploration of multiple-wh cases for future work, we believe that they are actually a homogeneous set of constructions with various, construction-specific, implications for the distribution of Agent Focus. For instance, in examples like (62) and (63), there is reason to believe that the left-most nominal has not actually undergone A’-movement (explaining the lack of AF-marking in (62)), but is instead a high, base-generated topic. First, the higher nominal, while focus-marked, actually receives the interpretation of a contrastive topic (see, for example, Pixabaj and England 2011). Moreover, there is an intonational break between to the two preposed arguments, which is diagnostic of high base-generated topics in K’ichean languages (Aissen 1992). While this is only one possible counteranalysis of (62) and (63), it illustrates the kind of construction-specific properties that support a case-by-case exploration of the multiple-wh examples Erlewine (2016) discusses.Footnote 16 Given the facts considered in this paper, we suggest that an appeal to Anti-Locality will not be the best explanation of the distribution of Agent Focus across these constructions.

Importantly, we have not argued against the general existence of a restriction like Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality in (3). Rather, we have argued that it is not responsible for the ergative extraction restriction in Kaqchikel. This type of Anti-Locality may indeed play a role in subject/non-subject asymmetries (as argued, for example, in Brillman and Hirsch to appear for English; see Bošković 2016 for further discussion and references). For Mayan, however, we are left with the result that the extraction of an ergative subject requires a special construction—Agent Focus—regardless of the presence of intervening material. The results in Sect. 3 suggest that this ban is due neither to height of the transitive subject, nor to a problem with ergative agreement.

These results are important for accounts of syntactic ergativity more broadly. Though not discussed in detail in this paper (but see Erlewine 2016, and discussion in Baier 2017), an Anti-Locality-based account of Kaqchikel is initially appealing because of the potential to connect the restriction on extracting transitive subjects to anti-agreement effects or other subject/non-subject asymmetries in nominative-accusative languages (see Ouhalla 1993, discussed in Erlewine 2016). Though tempting, this type of unification does not seem to be right for Mayan—a conclusion corroborated in recent work by Baier (2017), who argues independently that Spec-to-Spec Anti-Locality cannot account for anti-agreement effects in Berber. We suggest that this should lead us to question whether such an extension is generally warranted for ergative extraction restrictions (cf. Deal 2016).

We conclude that, in the absence of strong language-internal evidence, ergative extraction restrictions should not be grouped together with anti-agreement or other subject effects in nominative-accusative languages. Indeed, work on ergativity increasingly converges on the idea that while there is considerable variation among ergative languages, ergative subjects are low (see Legate 2017). This is consistent with the possibility that it is the low licensing of ergative subjects—and thus the need in some ergative languages for finite Infl0 to license transitive objects at a distance—that creates the restriction on ergative extraction (Campana 1992; Ordóñez 1995; Bittner and Hale 1996; Coon et al. 2014; Assmann et al. 2015).

Notes

Abbreviations used in glosses are as follows: abs—absolutive; af—Agent Focus; ap—antipassive; caus—causative; comp—complementizer; cpl—completive; deic—deictic; erg—ergative; exst—existential; foc—focus; icpl—incompletive; irr—irrealis; mov—movement particle; nml—nominal; p—plural; part—particle; pass—passive; perf—perfect; pot—potential; prep—preposition; pron—pronoun; rel—relative clause marker; rn—relational noun; s—singular. In some cases we simplify glosses (e.g. not parsing out status suffixes), where not directly relevant to the discussion. Note that we have altered Erlewine’s examples to be in accordance with standard Kaqchikel orthography. Unattributed examples are from direct elicitation.

Erlewine also discusses cases of multiple wh-movement, which we review in Sect. 6.

Note that ‘to valorize’ in Kaqchikel is an idiomatic construction that literally means ‘to give its day.’ We point this out because the construction occurs in many of the corpus examples we discuss.

The source for many of the naturally occurring examples is a Kaqchikel bible whose text the first author has extracted and cleaned (Wycliffe Bible Translators, Inc 2012, abbreviated ‘WBT’). This particular bible was translated by a team of native speakers of Kaqchikel, and the translation is extremely loose. The result is that the text, while clearly biblical in content, is similar to other Kaqchikel texts concerning the range of constructions one finds. We include these corpus forms as evidence that even in non-elicited environments, these alternations can be found. As also noted in the text, every construction discussed here has also been replicated in elicitation.

We parse out a null 3rd person singular absolutive morpheme in the examples in this paper for clarity, i.e. to make clear that the verb would show absolutive morphology here if the indexed argument were 1st or 2nd person. We do not make a theoretical commitment to the existence of a null morpheme.

Note that these case-based approaches are also compatible with existing analyses of verb initial word order in Mayan languages in which transitive subjects are taken to remain low. That subjects occupy a low position is proposed both in accounts in which the order of specifiers is parameterized (Aissen 1992), and in which a predicate fronts to a position above the subject (Coon 2010b; Clemens and Coon to appear). Erlewine (2016: fn. 20) suggests that Spec,IP is ordered to the right in Kaqchikel. Though feasible, we do not know of independent support for this account.

More needs to be said about why the ergative cross-references the theme in the embedded form in (17a). Under the analysis in Imanishi (2014), this is taken as evidence that ergative is assigned as a default to the highest unlicensed argument in the lower phase. An alternative, compatible with the case-based account, would be that a- in (17a) is truly possessor agreement, and that the possessor controls a null subject internal to the nominalization, here the passive subject; see Coon (2010a), Coon and Carolan (2017).

A similar pattern is described for related K’ichee’ by Aissen (2011), who notes that ergative-extraction from a regular transitive clause is possible when the object is a bare non-referential NP.

Facts like these also cast doubt on the applicability to Mayan languages of other explanations for syntactic ergativity which tie the ban on extracting ergatives directly to properties of the ergative subject. Such accounts include the proposal that some ergative subjects are in fact PPs (Polinsky 2016), or that the ban on extraction may be attributed to case-discrimination on the A’-probe (Deal 2016).

Note that complementizers are not just optional in the APred construction, but generally optional with embedded CPs, as illustrated here for the verb -etamaj ‘know’.

-

(36)

-

(36)

Note that while the resumptive pronouns in examples like (44) are preposed, they have not undergone A’-extraction. Kaqchikel allows subjects of all types to be preposed to a topic position, and pronouns are preferentially preposed. Such subjects never trigger AF unless marked with the focus particle, which indicates A’-extraction.

Having established that the APred construction involves resumption, and not A’-movement, the question of islands immediately arises. If resumption rescues island violations, then we would predict the APred construction should appear inside of islands with its pro subject bound by some higher A’-element, in contrast to the AF construction which requires a gap.

The problem is that resumptive pronouns in Kaqchikel do not obviate island violations in general, and so we cannot differentiate the AF and APred constructions in such contexts. That is, the fact that (47) is ungrammatical means that we do not expect (48) with the APred construction to be better than an AF construction in the same context, even though it has a resumptive pronoun.

-

(47)

-

(48)

We know that the APred construction involves a resumptive pronoun, but the precise distribution of resumptive pronouns elsewhere in Kaqchikel still requires further work. Note, though, that there are other cases where a resumptive pronoun construction alternates with a bona fide A’-construction (e.g. (42)–(43) above). We leave a fuller investigation of the distribution of resumptive pronouns in Kaqchikel to future work.

-

(47)

A reviewer asks whether jantäq ‘sometimes’ and jumul ‘always’ might be low in the structure, and thus would not render the subject sufficiently distant from CP to permit extraction. This is entirely plausible, and may also be connected to their inability to embed clauses. Note however that this alone does not explain why the other (potentially higher) adverbs show the variability we have identified here.

An anonymous reviewer asks whether additional tests for biclausality can be found to support the analysis presented here, for example, from the distribution of NPIs. At this point, we are unaware of other tests which would be applicable in the case of Kaqchikel. No NPIs have been described for Kaqchikel, and to the best of our knowledge, none exist. Similarly, Mayan languages generally lack A-movement, which might be expected to be clause-bound. Finally, as noted in Sect. 3.2, reflexives never appear in Agent Focus constructions, so we do not predict variation here.

Another possibility would be to appeal to the Principle of Minimal Compliance (Richards 1998), which has been used to explain the fact that the second movement in languages with multiple-wh-movement often need not meet grammatical conditions imposed on the first.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Aissen, Judith. 1992. Topic and focus in Mayan. Language 68 (1): 43–80.

Aissen, Judith. 2011. On the syntax of agent focus in K’ichee’. In Formal Approaches to Mayan Linguistics (FAMLi), eds. Kirill Shklovsky, Pedro Mateo Pedro, and Jessica Coon. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Aissen, Judith. 2017. Correlates of ergativity in Mayan. In Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aldridge, Edith. 2004. Ergativity and word order in Austronesian languages. PhD diss., Cornell University.

AnderBois, Scott, and Grant Armstrong. 2014. On a transitivity-based split in Yucatec Maya control complements. Paper presented at Workshop on Structure and Constituency in Languages of the Americas (WSCLA) 19, Memorial University, St. John’s.

Armstrong, Grant. 2009. Copular sentences in Yucatec Maya. In The Conference on Indigenous Languages of Latin America (CILLA) 4. Austin: University of Texas.

Assmann, Anke, Doreen Georgi, Fabian Heck, Gereon Müller, and Philipp Weisser. 2015. Ergatives move too early: On an instance of opacity in syntax. Syntax 18 (4): 343–387.

Baier, Nico. 2017. Antilocality and antiagreement. Linguistic Inquiry 48 (2).

Bittner, Maria, and Kenneth Hale. 1996. Ergativity: Toward a theory of a heterogeneous class. Linguistic Inquiry 27 (4): 531–604.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 1993. Nominally absolutive is not absolutely nominative. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 11. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Bok-Bennema, Reineke. 1991. Case and agreement in Inuit. Dordrecht: Foris.

Bošković, Željko. 1997. The syntax of nonfinite complementation: An economy approach. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2016. On the timing of labeling: Deducing comp-trace effects, the subject condition, the adjunct condition and tucking in from labeling. The Linguistic Review 33 (1): 17–66.

Brillman, Ruth J., and Aron Hirsch. To appear. An anti-locality account of English subject/non-subject asymmetries. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 50. Chicago Linguistic Society.

Campana, Mark. 1992. A movement theory of ergativity. PhD diss., McGill University.

Clemens, Lauren Eby, and Jessica Coon. To appear. Deriving verb initial order in Mayan. Language

Coon, Jessica. 2010a. Rethinking split ergativity in Chol. International Journal of American Linguistics 76 (2): 207–253.

Coon, Jessica. 2010b. VOS as predicate fronting in Chol. Lingua 120 (2): 354–378. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2008.07.006.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. Aspects of split ergativity. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

Coon, Jessica. 2016. Mayan morphosyntax. Language and Linguistics Compass 10 (10): 515–550.

Coon, Jessica. 2017. Little-v agreement and templatic morphology in Chol. Syntax 20 (2): 101–137.

Coon, Jessica, and Elizabeth Carolan. 2017. Nominalization and the structure of progressives in Chuj Mayan. Glossa 2 (1): 22.

Coon, Jessica, and Robert Henderson. 2011. Two binding puzzles in Mayan. In Representing language: Essays in honor of Judith Aissen, eds. Rodrigo Gutiérrez Bravo, Line Mikkelsen, and Eric Potsdam, 51–67. University of California, Santa Cruz: Linguistic Research Center.

Coon, Jessica, Pedro Mateo Pedro, and Omer Preminger. 2014. The role of case in A-bar extraction asymmetries: Evidence from Mayan. Linguistic Variation 14 (2): 179–242.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2016. Syntactic ergativity: Analysis and identification. Annual Review of Linguistics 2: 165–185.

England, Nora. 1991. Changes in basic word order in Mayan languages. International Journal of American Linguistics 57: 446–486.

England, Nora C. 2013. Cláusulas con flexión reducida en mam. In Estudios sintácticos en lenguas de Mesoamérica, eds. Enrique L. Palancar and Roberto Zavala, 277–303. Mexico City: CIESAS.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. 2016. Anti-locality and optimality in Kaqchikel Agent Focus. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34 (2): 429–479.

García Matzar, Pedro Oscar, and José Obispo Rodríguez Guaján. 1997. Rukemik ri kaqchikel chi’, gramática kaqchikel. Guatemala City: Cholsamaj.

Heaton, Raina. 2015. The status of syntactic ergativity in Kaqchikel. In The Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (SSILA), 1–8.

Henderson, Robert, Jessica Coon, and Lisa Travis. 2013. Micro- and macro-parameters in Mayan syntactic ergativity. Paper presented at Towards a Theory of Syntactic Variation, Bilbao.

Hou, Liwen. 2013. Agent Focus in Chuj reflexive constructions. BA Thesis, McGill University.

Imanishi, Yusuke. 2014. Default ergative. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Johns, Alana. 1992. Deriving ergativity. Linguistic Inquiry 23 (1): 57–88.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2008. Morphological and Abstract Case. Linguistic Inquiry 39 (1): 55–101. doi:10.1162/ling.2008.39.1.55.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2017. The locus of ergative case. In The Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa Travis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mondloch, James. 1981. Voice in Quiche-Maya. PhD diss., SUNY Albany.

Murasugi, Keiko, and Mamoru Saito. 1995. Adjunction and cyclicity. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 13, 302–317.

Ordóñez, Francisco. 1995. The antipassive in Jacaltec: A last resort strategy. Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics (CatWPL) 4 (2): 329–343.

Ouhalla, Jamal. 1993. Subject-extraction, negation, and the anti-agreement effect. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11: 477–518.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2001. T-to-C movement: Causes and consequences. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 355–426. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pixabaj, Can, and Nora England. 2011. Nominal topic and focus in K’ichee’. In Representing language: Essays in honor of Judith Aissen, eds. Rodrigo Guitérrez-Bravo, Line Mikkelsen, and Eric Potsdam, 15–30.

Polinsky, Maria. 2016. Deconstructing ergativity: Two types of ergative languages and their features. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Polinsky, Maria. 2017. Syntactic ergativity, 2nd edn. In Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk. Hoboken: Blackwell.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Richards, Norvin. 1998. The Principle of Minimal Compliance. Linguistic Inquiry 29 (4): 599–629. doi:10.1162/002438998553897.

Saito, Mamoru, and Keiko Murasugi. 1998. Subject predication within IP and DP. In Beyond principles and parameters: Essays in memory of Osvaldo Jaeggli, eds. Kyle Johnson and Ian Roberts, 159–182. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Stiebels, Barbara. 2006. Agent focus in Mayan languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24 (2): 501–570.

Tada, Hiroaki. 1993. A/A-bar partition in derivation. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Vázquez Álvarez, Juan J. 2013. Dos tipos de cláusulas no finitas en chol. In Estudios sintácticos en lenguas de Mesoamérica, eds. Enrique L. Palancar and Roberto Zavala. Mexico City: CIESAS.

Woolford, Ellen. 1997. Four-way case systems: Ergative, nominative, objective and accusative. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 15 (1): 181–227. doi:10.1023/A:1005796113097.

Woolford, Ellen. 2003. Clitics and agreement in competition: Ergative cross-referencing patterns. In Papers in Optimality Theory II, 421–449. Amherst: GLSA.

Wycliffe Bible Translators, Inc. 2012. El nuevo testamento en Cakchiquel Oriental. Orlando: Wycliffe Bible Translators, Inc.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Juan Ajsivinac, Gonzalo Ticun, Kanb’alam Batz, Ryan Bennett, Colin Brown, Lauren Clemens, Meaghan Fowlie, Henrison Hsieh, Hadas Kotek, Mitcho Erlewine, Justin Royer, Carlos Humberto Sactic, Byron Socorec, Lisa Travis, and Omer Preminger for helpful comments and discussion, as well as to audiences at NELS 46 and McGill for feedback. Special thanks to three anonymous reviewers and to Julie Anne Legate for detailed feedback at various stages of this work. Any errors are of course our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This reply refers to the article available at doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9310-z

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Henderson, R., Coon, J. Adverbs and variability in Kaqchikel Agent Focus. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 149–173 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9370-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9370-3