Abstract

In many languages, past-marking on stative predicates has been reported to trigger an inference of ‘cessation,’ that the past state in question does not hold at the present (Altshuler and Schwarzschild 2013, 2014). In English and many other languages, this inference can be shown to be defeasible, and so is therefore non-semantic. However, in other languages—such as the Tlingit language (Na-Dene; Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon)—the cessation inference of past-marked statives cannot be cancelled in the same way. This has lead some to propose that in these latter languages, the cessation inference is semantic, and is lexically encoded into the meaning of the past marker (Leer 1991; Copley 2005). Such a view would, of course, broaden the range of semantic tenses that exist in the world’s languages, to include a sub-category some have dubbed ‘Discontinuous Past’ (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006). Through in-depth investigation of one such putative ‘discontinuous past’ marker in the Tlingit language, I argue that—to the contrary—these morphemes are in their lexical semantics simply (plain) past tenses. On the basis of original field data I show that—while the cessation inferences of Tlingit are different from English-style ‘cessation implicatures’—they are nevertheless still defeasible, and so non-semantic. I develop an account of the cessation inference in Tlingit, whereby it arises from the optionality of the past-tense marker in question. I argue that this account should be extended to all putative instances of ‘Discontinuous Past,’ since it would capture the fact that putative cases of ‘Discontinuous Past’ only ever arise in optional tense languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: Variation in tense semantics and variation in cessation inferences

This paper seeks to advance understanding of cross-linguistic variation in tense semantics by investigating an alleged subspecies of past tense marking that has been reported for numerous languages across the world. The potential existence of this special sub-variety of past tense meaning directly impacts the following, overarching question in the cross-linguistic study of tense semantics.

-

(1)

Overarching question :

What tense features does Universal Grammar (UG) allow for?

That is, taking for granted that UG permits languages to contain T(ense) P(hrases), the question naturally arises as to what tense features the T-heads of these phrases can bear. Decades of formal semantic study of familiar Indo-European languages has established that T-heads can bear the features ‘past’ [PST] and possibly ‘present’ [PRS].Footnote 1 More recently, in-depth theoretically informed investigation of superficially ‘tenseless’ languages such as Lillooet (Salish; BC) has strongly suggested that T-heads in some languages can bear a ‘non-future’ feature [NFUT] (Matthewson 2006). It is also widely reported in traditional descriptive literature that certain languages possess so-called ‘graded tenses,’ morphemes that indicate how far into the past or future a particular eventuality occurs (Comrie 1985; Dahl 1985; Bybee et al. 1994). However, recent investigations by formal semanticists have shown that the status of these morphemes as true ‘tenses’ (T-heads) is potentially in doubt (Cable 2013; cf. Klecha and Bochnak 2016; Mucha 2016). It is therefore of acute interest whether there are any languages where T-heads can be shown to bear a feature other than [PST], [PRS], or [NFUT].

Bearing directly upon this question is a puzzle concerning the apparent variation across languages in the ability for past-marking to give rise to so-called ‘cessation inferences.’ To begin, it has been observed in many languages that the use of a past-marked stative predicate can give rise in certain contexts (specified later in Sect. 4) to an inference that a state of the kind described by the predicate does not exist at present. Such ‘cessation inferences’ have long been noted for English (Musan 1997; Magri 2011; Thomas 2014a; Altshuler and Schwarzschild 2013).

-

(2)

Cessation inferences in English Footnote 2

a.

(i)

Dialog:

Person 1:

Who wrote that song ‘Sledgehammer’?

Person 2:

Oh, I knew this!…

(ii)

Inference:

Person 2 does not currently know the answer.

b.

(i)

Dialog:

Person 1:

How are you feeling?

Person 2:

Well, I was nauseous.

(ii)

Inference:

Person 2 is not currently nauseous.

c.

(i)

Dialog:

Person 1:

Is Dave enjoying the party?

Person 2:

Well, he was dancing.

(ii)

Inference:

Dave is not currently dancing.

d.

(i)

Dialog:

Person 1:

Tell me something about Dave.

Person 2:

Well, he was from Montana.

(ii)

Inference:

Dave is not currently from Montana (and so is dead).

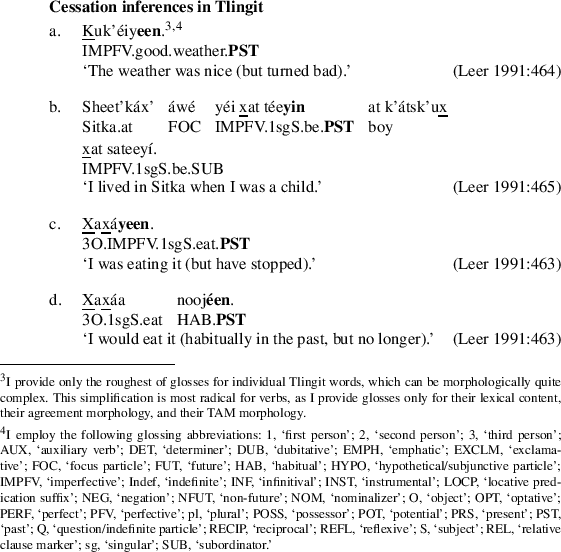

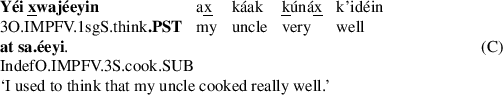

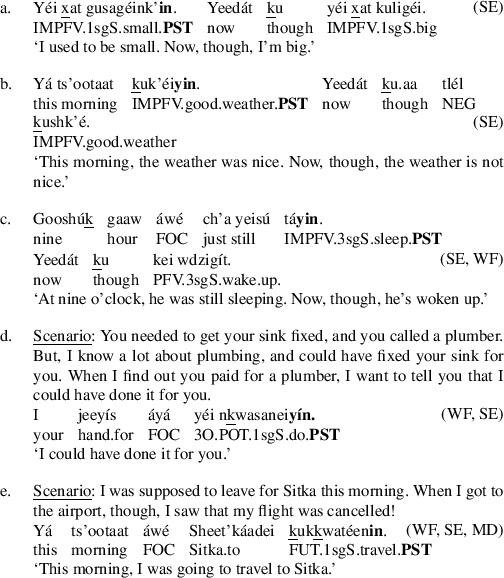

Similar such inferences are reported for the Tlingit language (Na-Dene; Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon) by Leer (1991). In all the sentences below, the main verb bears past-marking, and Leer reports that the comments made by speakers indicate that the states in question are understood not to continue into the present. The accompanying English free translations are those provided by Leer (1991).

-

(3)

Furthermore, Leer (1991:465) states regarding sentence (3a) that “… [This sentence] means that a specific situation, namely an instance of good weather, was true in the past and is not true now” (Leer 1991:465), and regarding sentence (3b) that “… [This sentence] could be said by someone who left Sitka during childhood…”Footnote 3

It seems, then, that both English and Tlingit exhibit cessation inferences with past-marked statives. Importantly, however, it has long been recognized that in English, these inferences have the status of (conversational) implicatures (Musan 1997; Magri 2011; Thomas 2014a; Altshuler and Schwarzschild 2013). That is, in English, these cessation inferences are defeasible, as shown by the felicity of the conjunctions in (4).

-

(4)

-

a.

I knew this years ago, and I still know it now.

-

b.

I was nauseous this morning, and I’m still nauseous now.

-

c.

Dave was dancing an hour ago, and he’s still dancing now.

-

d.

Dave was from Montana this morning, and (of course) he’s still from there now.

-

a.

Furthermore, there are certain contexts in English where past-marked statives do not give rise to a cessation inference. In particular, if prior discourse establishes a topical past time—i.e., a past ‘Topic Time’—then the cessation inference is defeated (Klein 1994). For example, in none of the sentences below, is the state generally understood to end prior to the time of the utterance.

-

(5)

-

a.

As soon as you asked me the question, I knew the answer.

-

b.

When the doctor saw me, I was (already) nauseous.

-

c.

I just saw Dave in the kitchen. He was dancing.

-

d.

I met this really cool guy named Dave yesterday. He was from Montana.

-

a.

Facts such as these establish that the cessation inferences of English past tense are non-semantic; they are not encoded as part of the lexical semantics of English past-marking.

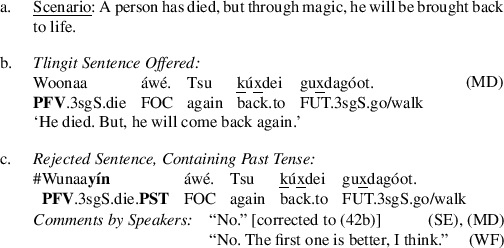

Curiously, however, the cessation inferences found in Tlingit do not pass these important tests for implicature-hood. To begin, it is not possible in Tlingit to directly cancel the cessation inference in the way done in (4). To express conjunctions like those in (4), Tlingit requires the verbs of both conjuncts to be unmarked for tense. As shown below, use of the overt past-marking in the first conjunct results in infelicity.

-

(6)

-

(7)

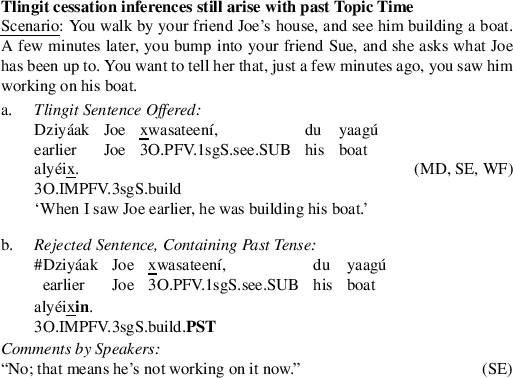

Furthermore, while the cessation inference of English past tense disappears when there is a past Topic Time (5), the cessation inferences of Tlingit still arise in such contexts. Consider the rejection of the past-marked sentences in (8) and (9) below.

-

(8)

-

(9)

In both (8) and (9), a preceding clause establishes a particular past time—the time of the speaker seeing Joe—as the Topic Time (Klein 1994). Nevertheless, the rejection of (8b)–(9b) and the comments provided by the speakers indicate that use of an overtly past-marked stative triggers a cessation inference. In contrast, note that the English translations of (8a) and (9a) both contain past-marked statives, but are nevertheless felicitous in these scenarios, due to the cancellation of the English cessation implicature.

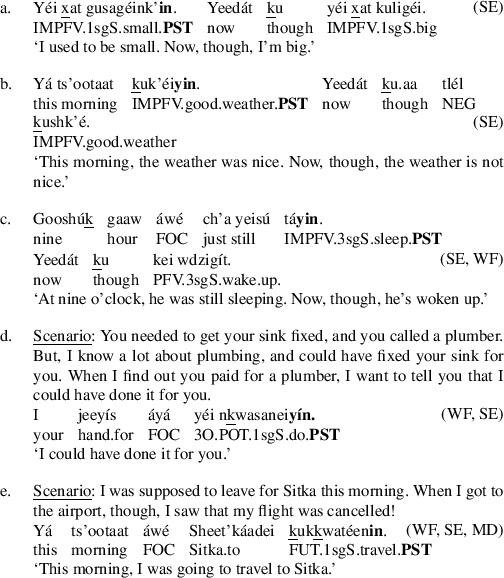

It should also be briefly noted that the speakers judging the sentences in (6)–(9) do readily accept the use of past-marked statives, just as long as the context makes clear that the associated cessation inference holds. This is illustrated by the felicity of the sentences in (10) below.

-

(10)

It summary, it seems that the cessation inferences associated with Tlingit past-marking do not behave like those associated with English past tense, and do not pass the tests in (4) and (5) for being implicatures. This, of course, raises the crucial question of why: why does this difference exist between the cessation inferences of Tlingit and English? One obvious possibility is that—while the cessation inference found in English is non-semantic—the cessation inference of Tlingit is semantic. That is, it could simply be that the past-tense marker in Tlingit has the cessation inference built into its very lexical semantics. Exactly this answer is put forth by Leer (1991), who claims that the marker in question “…means that (the sentence) was true at some time in the past, but is no longer true at present” (Leer 1991:461).

The notion that past-marking in some languages might lexically encode a cessation inference has indeed been independently proposed multiple times. For example, Copley (2005) investigates and analyzes the past-marker cem in Tohono O’odham, and puts forth an analysis whereby this particle directly entails cessation when marking a stative predicate. Furthermore, Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) catalog numerous cases from around the world where past-markers are reported to contribute ‘cessation’ as part of their lexical meaning, including such languages as Wolof (Niger-Congo; West Africa), Tokelauan (Polynesian; Tokelau), Lezgian (Nakh-Daghestanian; Dagestan), Sranan (Creole; Suriname), Bamana (Mande; Mali), and Washo (isolate; California). The abundance and similarity of such cases lead Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) to propose the existence of a special tense category, which they dub ‘discontinuous past,’ defined for our purposes as in (11).

-

(11)

‘Discontinuous past’ (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006 ) Footnote 4

A past tense marker for which the cessation inference has become part of its conventionalized, lexicalized meaning.

Thus, Plungian and van der Auwera propose that languages like Tlingit, Tohono O’Odham, etc. all contain a special sub-variety of past tense—discontinuous past—which is distinguished semantically from the (plain) past tense of languages like English, in that only the former lexically encodes a cessation inference.

We find, then, that the behavior of cessation inferences in languages like Tlingit directly bears upon our overarching question in (1). If the reason for the contrasts between (4) and (5) and (6)–(9) is indeed that Tlingit possesses a special subcategory of past-marking (‘discontinuous past’) then this would suggest that the inventory of tense features allowable by UG should be expanded to include a ‘discontinuous past’ feature, [DisPST], one that is semantically stronger than (plain) [PST].

In this paper, however, I will argue against the existence of ‘discontinuous past’ as a distinct (sub)category of tense feature. More acutely, I will argue that despite the facts in (6)–(9), the cessation inference found in Tlingit is non-semantic; it is a pragmatic effect and is not encoded in the lexical semantics of the past-marker itself. As we will see, there are grammatical and contextual environments where the Tlingit past-marker does not give rise to a cessation inference, just as with English past tense. I will propose, however, that the cessation inference associated with Tlingit past-marking arises from different pragmatic mechanisms than the ones responsible for English cessation implicatures. In particular, I will develop a semantic/pragmatic analysis whereby the Tlingit cessation inference in (6)–(9) arises from two key factors: (i) the optionality of past-marking in Tlingit, and (ii) a special principle relating to the topicality of the utterance time. I will then go on to argue that this same analysis should be extended to all putative instances of ‘discontinuous past.’ The principal argument for treating all cases of ‘discontinuous past’ in this manner is that it would capture the following striking fact: all reported instances of ‘discontinuous past’ are found in ‘optional tense’ languages, where they are the optional marker for past tense (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006). Consequently, I will conclude that there is yet no evidence for ‘discontinuous past’ as a separate (sub)category of tense feature.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the following section, I provide some basic background concerning the Tlingit language and the nature of the Tlingit language data presented here. Section 3 then presents the paper’s main empirical arguments that Tlingit cessation inferences are non-semantic, as they are absent in the following cases: (i) in certain naturally occurring corpus data, (ii) in elicited examples where the speaker asserts ignorance concerning the present, and (iii) in elicited examples where the past-marked verb appears embedded below another past-marked verb. Having shown that Tlingit does not contain a ‘discontinuous past’ as defined in (11), I then provide my typological argument against the notion that any language contains such a category of past marking. The conclusion of this argument is that all alleged instances of discontinuous past are, in their semantics, simply optional past tense markers. This raises the question of how such ‘optional pasts’ could come to trigger cessation inferences exhibiting the properties in (6)–(9). In Sect. 4, I present my proposed analysis of the semantics and pragmatics of these tense markers, whereby their cessation inferences are crucially tied to their optionality.

With the semantic/pragmatic analysis in place, I show in Sect. 5 that this analysis can capture one additional puzzling feature of these putative ‘discontinuous past’ markers: their interactions with perfect(ive) predicates. As we’ll see, in Tlingit and many other languages, optional past-marking on perfect(ive) predicates can give rise to two different, additional forms of inference: (i) that the state resulting from the described event fails to extend into the present, or (ii) that the described event failed to have some expected consequence. I will show that, given independent facts about perfect(ive)-marking in these languages, these facts will follow from the analysis put forth in Sect. 4.

2 Linguistic and methodological background regarding Tlingit language

The Tlingit language (Lingít; /ɬın.kít/) is the traditional language of the Tlingit people of Southeast Alaska, Northwest British Columbia, and Southwest Yukon Territory. It is the sole member of the Tlingit language family, a sub-branch of the larger Na-Dene language family (Campbell 1997; Mithun 1999; Leer et al. 2010). It is thus distantly related to the Athabaskan languages (e.g., Navajo, Slave, Hupa), and shares their complex templatic verbal morphology (Leer 1991). As mentioned in fn. 3, I will largely be suppressing this complex structure in my glossing of Tlingit verbs.

Tlingit is a highly endangered language. While there has been no official count of fully fluent speakers, it is privately estimated by some that there may be less than 200 (James Crippen (Dzéiwsh), Lance Twitchell (X’unei), p.c.). Most of these speakers are above the age of 70, and there is likely no native speaker below the age of 50. There are extensive, community-based efforts to revitalize the language, driven by a multitude of Native organizations and language activists too numerous to list here. Thanks to these efforts, some younger adults have acquired a significant degree of fluency, and there is growing optimism regarding a new generation of native speakers.

Unless otherwise noted, all data reported here were obtained through interviews with native speakers of Tlingit. Six fluent Tlingit elders participated: Margaret Dutson (Shaksháani), Selena Everson (Kaséix), William Fawcett (Kóoshdaak’w Éesh), Carolyn Martin (K’altseen), John Martin (Keihéenák’w), and Helen Sarabia (Kaachkoo.aakw). All six were residents of Juneau, AK at the time of our meetings, and are speakers of the Northern dialect of Tlingit (Leer 1991). Two or three elders were present at each of the interviews, which were held in classrooms at the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau, AK.

The linguistic tasks presented to the elders were straightforward translation and judgment tasks. The elders were presented with various scenarios, paired with English sentences that could felicitously describe those scenarios. The scenarios were described orally to the elders, all of whom are entirely fluent in English, and a written (English) description was also distributed. The elders were asked to freely describe the scenarios, as well as to translate certain targeted English sentences describing them. In order to more systematically study their semantics—and to obtain negative data—sentences containing past tense morphology were examined using truth/felicity judgment tasks, a foundational methodology of semantic fieldwork (Matthewson 2004). The elders were thus asked to judge the ‘correctness’ (broadly speaking) of various Tlingit sentences relative to certain scenarios. The sentences evaluated were either ones offered earlier by the speakers for other scenarios, or ones constructed by myself and judged by the speakers to sound natural and correct for other scenarios. Unless otherwise indicated, all speakers agreed upon the reported status of the sentences presented here.

2.1 Further background on Tlingit past-marking: The ‘decessive epimode’

The Tlingit sentences in (6)–(10) above were said to contain ‘past-marking.’ The key morphology in question, however, is referred to by Tlingit language specialists as the ‘decessive epimode.’ This morphological category is realized by two non-consecutive exponents: (a) the so-called ‘[-I]’ feature of the verbal classifier, and (b) a verbal suffix.Footnote 5 The form of the verbal suffix depends upon the kind of clause headed by the verb. In a main clause, the decessive suffix is underlyingly -een, but phonological processes can cause it to surface as -yeen, -éen, -yéen, -oon, -woon, -óon, or -wóon. Furthermore, for speakers of the Northern Dialect of Tlingit, these allomorphs can all optionally contain short vowels (-in, -yin, -ín, -yín, -un, -wun, -ún, -wún). In a relative clause, however, the decessive suffix is underlyingly -i, and much the same phonological processes apply to generate varying allomorphs (-yi, -u, -wu). Finally, in all other subordinate clauses, the decessive is realized by the post-verbal particle yéeyi.Footnote 6 Throughout the example sentences in this paper, the suffix realizing the decessive will be boldfaced for the reader.

In the earliest descriptive literature on Tlingit, the decessive is simply analyzed as an optional marker of past tense (Boas 1917:84; Story 1966:143). Later, in their extensive verbal dictionary for the language, Story and Naish (1973:356) add the detail that the decessive “refer(s) to a time when the situation was other than it was, is, or will be.” This aspect of the decessive’s meaning is greatly expanded upon in the work of Leer (1991:460–478), who—as noted above—proposed that the decessive lexically encodes a cessation inference.

In the following section, however, we will see that the Tlingit ‘decessive epimode’ is in its lexical semantics nothing more than an optional past tense. For this reason, in all the example sentences found here, I will gloss this morphology as a past tense (PST).

3 Evidence that the cessation inference in Tlingit is not semantic

In Sect. 1, we saw that the cessation inferences of the Tlingit decessive cannot be cancelled in the way that the cessation implicatures of English past tense can. This fact, however, doesn’t necessarily show that those inferences are lexically encoded in Tlingit. All we know for certain is that they are not perfectly identical to English-style cessation implicatures; they could nevertheless be generated via other pragmatic processes. In this section, I will present evidence that this is indeed the case. That is, despite the facts in (6)–(9), Tlingit cessation inferences can be cancelled in certain environments, and so we must conclude that they are not part of the conventionalized, lexical content of the Tlingit decessive. Furthermore, once these facts are on the table, we will see that they call into question whether there is any language where cessation inferences are lexically encoded into the semantics of a past-marker (cf. Plungian and van der Auwera 2006).

3.1 Absence of cessation in examples taken from naturally produced texts

As one would expect from the data in (6)–(10), within naturally produced Tlingit narratives, decessive-marked statives most commonly appear in contexts that support a cessation inference. However, upon further examination, this seems only to be a tendency. Within the published corpus of naturally produced Tlingit narratives, there are examples of decessive statives where a cessation inference is not contextually supported. Most importantly, there are even examples where such an inference would seem to be inconsistent with the surrounding context. For reasons of space, I will provide just one striking example.

In sentence (12) below, the narrator is referring to a petroglyph carved by Kaax’achgóok, an ancestral hero of the Kiks.ádi clan in Sitka, AK. This petroglyph is generally known to still exist in Sitka (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1987:330), and in the line immediately following (12), the narrator tells the addressee that they will go visit it later.

-

(12)

With all this in mind, the decessive stative in (12) does not seem to imply in its original context that the carving no longer exists or has moved from its former location. Consequently, we find that there are naturally produced examples of decessive statives lacking the cessation inference at play in (6)–(9), and so that inference cannot be encoded in the lexical semantics of the decessive.

3.2 Cancellation of cessation inference with explicit statements of ignorance

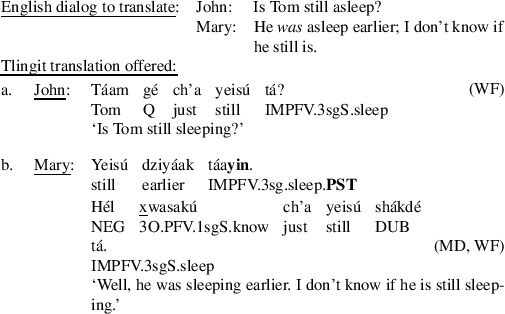

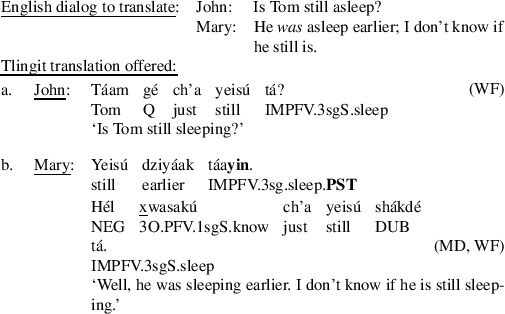

In Sect. 1, it was shown that, unlike a cessation implicature in English, the cessation inference found in Tlingit is not cancelled simply by there being a past Topic Time. Importantly, however, it does seem that a Tlingit cessation inference can be cancelled by an explicit statement of ignorance concerning the present (i.e., the Utterance Time). That is, as shown by dialogs like the following, Tlingit speakers can use a decessive stative when they don’t know whether the past state/event extends into the present.

-

(13)

In the dialog above, Joe explicitly states that he doesn’t know whether John is still currently in Sitka. Nevertheless, the decessive suffix appears in the translation under (13c): Áa yéi teeyín ‘he was there.’ Since Joe admittedly doesn’t know whether John is still in Sitka, he could not be asserting in (13c) that John is no longer in Sitka. Thus, we find that the decessive stative in (13c) does not imply here that John is no longer in Sitka. Consequently, it seems that the cessation inference is cancelled in this context. Another example of such cancellation is given below.

-

(14)

In the dialog above, Mary doesn’t know whether a particular state (Tom’s sleeping) extends into the present or not. Nevertheless, in the Tlingit translation of her statement, she uses the decessive suffix when describing that past state. It follows, then, that the decessive sentence in this dialog cannot be asserting that the past state in question fails to extend into the present. We can therefore conclude that in this example, the decessive suffix does not contribute a cessation inference.

In summary, it is possible after all to cancel the cessation inference of a decessive stative in Tlingit. Although that inference is not cancelled merely by the existence of a past Topic Time, it can be cancelled by an explicit statement of ignorance concerning the present. Consequently, that cessation inference is not a lexicalized part of the semantics of the past-marker.

3.3 Absence of cessation inference in embedded clauses

Further evidence for the non-semantic nature of the Tlingit cessation inference can be found in the behavior of past-marked verbs that are in the complement of a propositional attitude verb. The key generalization is as stated in (15) below.

-

(15)

Decessive statives in the complement to decessive attitude verbs

If a propositional attitude verb in Tlingit is past-marked, then the verb of its complement can also bear past-marking, without contributing any cessation inference.

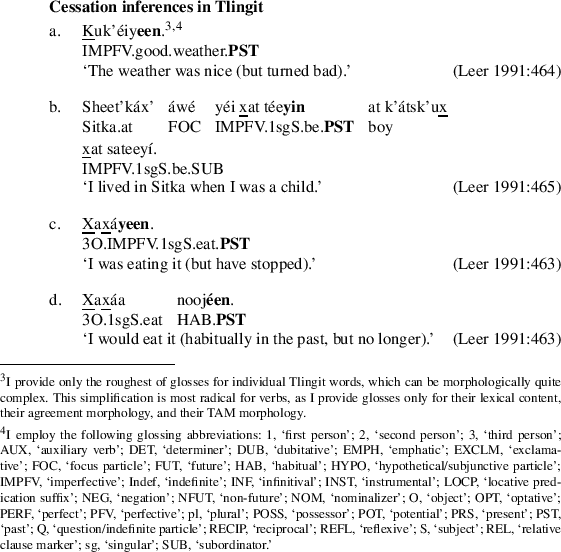

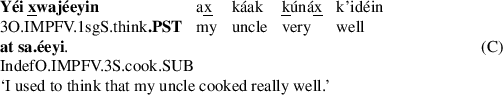

To illustrate, consider the scenario in (16a), as well as the felicitous Tlingit sentence in (16b).

-

(16)

What’s crucial here is that in scenario (16a), what the imagined speaker actually believed was “my uncle cooks really well.” They did not ever believe “my uncle used to cook really well, but then he stopped doing so.” Thus, the decessive suffix on the embedded imperfective verb at sa.éeyin ‘he cooked’ seems not to contribute a cessation inference in (16b).

One might nevertheless doubt whether cases like (16b) really provide convincing evidence that the cessation inference is not a part of the lexical semantics of Tlingit past-marking. To begin, let us note that in cases like (16), the embedded past-marking also seems not to contribute an inference of past-ness; again, in scenario (16a), the speaker believed “my uncle cooks well”, not “my uncle cooked well.” With this in mind, the use of embedded past-marking in (16b) is quite reminiscent of the so-called ‘simultaneous readings’ of embedded past tense in languages like English, as illustrated by sentences like (17) in contexts like (16a).

-

(17)

I thought that my uncle cooked really well.

Given the similarity between (16b) and (17), one might wonder whether Tlingit (16b) should receive the same general analysis as English (17). Now, one well-known analysis of simultaneous readings in English posits that the embedded past tense in sentences like (17) is not actually semantically interpreted (Abusch 1997; Kratzer 1998; von Stechow 2003). Therefore, one might wonder whether the possibility of (16b) is rather due to a general ‘semantic invisibility’ of the embedded past-marking, an analysis that would be consistent with that past-marking lexically encoding a cessation inference.

In response to this concern, it should first be noted that it remains controversial whether English sentences like (17) truly contain a semantically invisible past tense. Altshuler (2016:Chap. 3), for example, proposes an analysis of cases like (17) where the embedded past is fully interpreted. Furthermore, even if we accept the ‘vacuous tense’ analysis of English (17), we shouldn’t necessarily conclude from its surface similarity that the Tlingit sentence in (16b) also contains a ‘vacuous’ past marker. Ogihara and Sharvit (2012) argue that while English sentences like (17) indeed contain a semantically invisible past tense, superficially similar cases of such ‘simultaneous readings’ of embedded past in Hebrew must receive a different analysis. While space precludes a full comparison of accounts, it should be noted that Tlingit shares with Hebrew a property that Ogihara and Sharvit (2012) claim distinguishes languages that lack the ‘vacuous tense’ of English. In both Hebrew and Tlingit, a simultaneous reading is also possible for sentences in which the embedded clause does not bear past-marking. That is, along with (16b) in Tlingit, the sentence in (18) is also acceptable in context (16a).

-

(18)

Similarly, while sentence (19bi)—with embedded past—is accepted by Hebrew speakers for context (19a), such speakers also readily accept sentence (19bii), which lacks embedded past.

-

(19)

In Ogihara and Sharvit’s (2012) account, languages exhibiting this behavior are not ones where embedded past tense can be semantically uninterpreted. Rather, they are languages where a fully interpreted embedded past tense allows for a special de re construal, one that renders them acceptable in contexts like (16a) and (19a). Adopting their approach, we would conclude that the embedded decessive marking in Tlingit (16b) is semantically interpreted, but given a de re construal. Consequently, the lack of an (embedded) cessation inference in (16b) cannot be due to the embedded decessive marker not being semantically interpreted. We therefore again conclude that the failure of the embedded decessive marker in (16b) to trigger a cessation inference suggests that such inferences are not encoded within the lexical semantics of the decessive.Footnote 7

Some further data supporting the key generalization in (15) are presented below. Again, in scenario (20a), what the imagined speaker believed was “Juneau is a big city.” They didn’t ever hold the belief “Juneau was a big city, but isn’t anymore.” Thus, again the past-suffix on the embedded imperfective verbs in (20b) seems not to contribute a cessation inference.

-

(20)

3.4 Consequences for the existence of ‘discontinuous past’ across languages

The preceding sections have demonstrated that despite the facts in (6)–(9), the cessation inference found with past-marking (‘decessive epimode’) in Tlingit is not a part of its lexical semantics, but is instead a defeasible, pragmatic effect.Footnote 8 Thus, the Tlingit ‘decessive epimode’ is not an instance of ‘discontinuous past,’ in the theoretically importance sense of (11). This, of course, raises the question of whether there are any other, clearer examples of such ‘discontinuous past’ in the languages of the world. In this section, I present some reasons for doubt.

First and foremost, it should be noted that—to my knowledge—no other alleged instances of discontinuous past have ever been tested in the environments in Sects. 3.2–3.3. Since they provide the crucial evidence that Tlingit past-marking is not, after all, an instance of discontinuous past, any alleged cases of discontinuous past should be examined in those environments before we can be confident that their cessation inferences are indeed lexicalized.

Furthermore, as briefly mentioned in Sect. 1, Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) themselves note the following curious generalization regarding their putative cases of discontinuous past.

-

(21)

‘Discontinuity’ and optionality

In all languages containing a ‘discontinuous past,’ (i) there is no obligatory past tense morphology (i.e., unmarked verbs can receive either past or present interpretation), and (ii) the ‘discontinuous past’ is the only morpheme that contributes past tenseFootnote 9

According to the typological generalizations in (21), there are no languages containing both (i) a discontinuous past, and (ii) an optional ‘pure’ past tense (one for which the cessation inference is merely pragmatic). Similarly, there appears not to be any ‘obligatory tense’ language that also contains a discontinuous past marker, optional or obligatory. Relatedly, there does not appear to be any language with an obligatory discontinuous past marker; that is, in every language with a putative ‘discontinuous past,’ the marker in question does not have to be used in contexts supporting a cessation inference.

These facts, of course, raise the question of why the typological pattern in (21) should hold. Importantly, this pattern is quite unexpected if ‘discontinuous past’ is simply another tense feature, on par with Past, Present, and Future. Even the less frequent ‘graded’ tense categories (such as ‘Hodiernal’ or ‘Hesternal’ Past) can (i) appear in obligatory tense languages, or (ii) co-occur with regular ‘pure’ past tense (Hayashi 2011; Cable 2013). Why, then, should a Discontinuous Past feature be any different? Why should it seem to be incompatible with (i) its marker being obligatory, or (ii) there being a separate realization of ‘pure’ past tense?Footnote 10

With these questions in mind, let us consider instead another possibility. Suppose that, despite the facts in (6)–(9), the Tlingit decessive—and by extension, all putative cases of ‘discontinuous past’—is in its lexical semantics simply an optional, ‘pure’ past tense. That is, suppose that these markers only contribute the ‘anteriority’ semantics of English past tense. Let us also suppose that the cessation inference associated with these markers could somehow be predicted as a pragmatic inference arising from the very properties invoked in (21). It would, of course, then trivially follow that only languages and morphemes exhibiting the properties in (21) would also trigger such special cessation inferences. That is, we would straightforwardly predict that these kinds of cessation inferences would be restricted to morphemes/languages for which (21) hold, and so the typological pattern would be accounted for.

For this reason, the typological facts in (21) provide some additional motivation for exploring an analysis where the special inferences associated with putative cases of ‘discontinuous past’ are not part of their lexical semantics, but are instead somehow predicted via pragmatics. Let us now attempt to construct just such an account.

4 Cessation inferences in English and in Tlingit

We have seen that, just like the cessation implicatures of English, the cessation inferences of Tlingit are non-semantic, and arise through some form of pragmatic reasoning. This, of course, re-raises the core question of why those inferences in Tlingit cannot be cancelled in the way that English cessation implicatures can be (4)–(9). Any answer to this question will necessarily assume some theory of how cessation implicatures arise in English. For this reason, I will begin here by laying out an analysis of the English data in (2)–(5). My account builds heavily upon the analysis of Altshuler and Schwarzschild (2013), though it differs from theirs in significant ways.

To begin, let us review some assumptions regarding the syntax and semantics of tense. Following much of the prior literature on tense (Klein 1994; Abusch 1997; Kratzer 1998; Matthewson 2006, inter multa alia), I assume that syntactic T(ense)-heads function as temporal anaphors, directly referring to a so-called ‘Topic Time’ (TT). Tense features, such as Past are thus pronominal features, and so introduce presuppositions that constrain the reference of the T-heads. These ideas can be formalized as in (22) below.

-

(22)

-

a.

[[ [Tense PST ]i ]]w,t,g = g(i), only if g(i) < t; undefined otherwise

-

b.

[[ [Tense PRES ]i ]]w,t,g = g(i), only if g(i) = t; undefined otherwise

-

a.

As shown in (22a), a T-head bearing the feature Past (PST) is a temporal pronoun, and so bears a pronominal index i. Relative to an evaluation world w, evaluation time t, and a variable assignment g, the denotation of such a T-head is simply the value of its index, g(i), just as long as that value g(i) precedes the evaluation time t. Consequently, if a T-heads bears Past, it can only ever end up denoting times that are in the past of the evaluation time t. A similar semantics can be given for Present (PRES) T-heads (22b), where they end up only ever denoting times that are equal to the evaluation time t.

In this way, the semantics in (22) instantiates Klein’s (1994) view that tense features serve to constrain the relation between the Topic Time (denoted by the tense head) and the Utterance Time (the evaluation time of the matrix clause). I will also follow much of the prior literature on aspect by assuming the Kleinian hypothesis that aspectual features serve to constrain the relation between the Topic Time and the Event Time (Klein 1994). That is, as formalized in (23), Aspect heads take as argument a property of events (denoted by the VP), and return a property of times, ultimately predicated of the Topic Time denoted by the Tense head.

-

(23)

-

a.

[[ [Aspect IMPFV ] ]]w,t,g = [ λQ<εt>: [ λt′: ∃e. Q(e) & t′ ⊆ T(e) ] ]

-

b.

[[ [Aspect PFV ] ]]w,t,g = [ λQ<εt>: [ λt′: ∃e. Q(e) & T(e) ⊂ t′ ] ]

-

a.

For example, an Aspect head bearing imperfective (IMPFV) will take as argument the denotation of the VP (Q) and will return a predicate that is true of the topic time t′ iff there is an event e of the kind denoted by the VP, such that the topic time t′ is contained with the Event Time of e (T(e)). Thus, IMPFV contributes the information that the TT is contained within the ET. A similar denotation is offered for perfective aspect (PFV) in (23b), which implements the classic notion that perfective aspect locates the ET within the TT.

The denotations in (22) and (23) fit most naturally within a syntax where the Aspectual Projection is complement to the Tense head, as is illustrated by the LF in (24b) below.

-

(24)

-

a.

Sentence: Scotty was nauseous.

-

b.

LF of (24a), in a context with past Topic Time:

[TP [T PST ]i [ IMPFV [ Scotty be nauseous] ] ]

-

c.

Predicted Truth-Conditions:

[[(24b)]]w,t,g is defined only if g(i) < t. If defined, is true iff

∃e. nauseous(e) & Thm(e) = Scotty & g(i) ⊆ T(e)

‘There is an eventuality e of Scotty being nauseous whose run-time T(e) contains the topic time g(i).’

-

a.

As shown in (24c), in contexts where there is a past Topic Time g(i), sentence (24a) is predicted by our semantics to be true iff there is an eventuality (state) of Scotty being nauseous which contains the TT. What, though, of contexts where there isn’t any past Topic Time? That is, what about contexts like those in (2), where the past tense sentence is uttered in a context where there is no contextually given past time yet in the discourse? I will assume that in such contexts—i.e., when there is no antecedent available for a tense head—a special ‘rescuing’ operation of existential closure can apply and bind the T-head (Ogihara and Sharvit 2012). The intended LF and predicted truth-conditions are as represented in (25a,b) below.

-

(25)

-

a.

LF of (24a), in a context with no past Topic Time:

[TP ∃i [TP [T PST ]i [ IMPFV [ Scotty be nauseous ] ] ] ]

-

b.

Predicted Truth-Conditions:Footnote 11

[[(25a)]]w,t,g is true iff

∃t′. t′ < t & ∃e. nauseous(e) & Thm(e) = Scotty & t′ ⊆ T(e)

‘There is a past time \(\mathrm{t}'\) and there is an eventuality e of Scotty being nauseous whose run time T(e) contains the past time t′.’

-

a.

Thus, in a context such as (2b), sentence (24a) is predicted to assert that there is some past time t′ at which Scotty is nauseous. Now, notice that it is exactly in such contexts that cessation implicatures are triggered in English. That is, following Musan (1997) and others, I make the following assumption regarding where English-style cessation implicatures are triggered.

-

(26)

Key generalization about cessation implicatures in English

In English, a cessation implicature is triggered when a past tense stative sentence is uttered in a context where there is no past Topic Time.

Note, for example, that in the dialogs in (2), the discourse-initial sentence does not introduce a past time that the second, past-tense sentence can take as its Topic Time. Consequently, the past-tense statives in (2) are all uttered in contexts lacking a past Topic Time.

Interestingly, this connection between cessation implicatures and the absence of past time antecedents can follow from the semantic system in (22)–(25), if we adopt the following crucial assumption, originally proposed by Altshuler and Schwarzschild (2013).

-

(27)

The Open Interval Hypothesis (Altshuler and Schwarzschild 2013 )

The run-time of a state is an open interval. That is, if e is a stative eventuality and t′ is a temporal instant contained within T(e) (t′ ⊆ T(e)), then there is a temporal instant t″ such that t″ < t′ and t″ is also contained within T(e) (t″ ⊆ T(e)).

According to the Open Interval Hypothesis above, there is no ‘first instant’ in the Event Time of any stative eventuality. For any temporal instant in the run-time of a state, there is always an (infinitesimally) prior temporal instant preceding it in the run-time.Footnote 12 Note that, as discussed by Altshuler and Schwarzschild (2013), this in no way implies that stative eventualities do not have a ‘beginning’; indeed, it is difficult to find any truly substantive metaphysical consequences of the hypothesis in (27).Footnote 13 Nevertheless, as first observed by Altshuler and Schwarzschild, this hypothesis does give us a possible explanation of the cessation implicatures in (2). In particular, it can derive them as simple cases of scalar implicature. To see this, let us compare the LF and truth-conditions in (25) to that of a (pragmatically competing) present tense sentence.

-

(28)

-

a.

Sentence: Scotty is nauseous.

-

b.

LF of (28a): [TP [T PRES ]i [ IMPFV [ Scotty be nauseous ] ] ]

-

c.

Predicted Truth-Conditions:

[[(28b)]]w,t,g is defined only if g(i) = t. If defined, is true iff

∃e. nauseous(e) & Thm(e) = Scotty & g(i) ⊆ T(e)

‘There is an eventuality e of Scotty being nauseous whose run-time T(e) contains the topic time g(i) (which is equal to the utterance time t)’

-

a.

Importantly, because of the Open Interval Hypothesis (27), the truth-conditions in (28c) are strictly stronger than the truth-conditions in (25b). Note that since the utterance time is (by common assumption) a temporal instant, (28c) and assumption (27) would together entail that there is a time t′ prior to the utterance time t (= g(i)) such that t′ ⊆ T(e). But, this of course is simply what the truth-conditions in (25b) state. Those latter truth-conditions, however, in no way entail that the Event Time T(e) encompasses the utterance time t as well as the past time t′.

Consequently, in contexts like (2), where there is no past Topic Time, a past tense stative will be strictly weaker than a corresponding present tense stative. For this reason, standard Gricean reasoning will lead to an inference that the present tense variant is false (or not known to be true).Footnote 14 In this way, the assumptions in (22)–(27) can account for key generalization in (26). Importantly, they can also account for the cancellation of such implicatures in contexts like (5), where there is a past Topic Time. Note that in such contexts, the existential closure in (25) will not occur, and a past tense sentence will have the LF and truth-conditions in (24). Furthermore, the truth-conditions in (24c) are simply incompatible with the present-tense truth-conditions in (28c); the two sets of truth-conditions make incompatible demands of the Topic Time g(i). Since the truth-conditions in (24c) and (28c) are incompatible, neither is stronger nor weaker than the other, and so no Gricean scalar inference will be triggered upon the utterance of (24a) in a context with a possible antecedent for ‘[T PST]i’. We therefore predict the absence of the cessation implicature in such contexts.

With this as background, let us now turn our attention to languages with ‘optional past tense,’ and let us see whether the special cessation inferences of such optional tenses can follow in a similarly principled way.

To begin, recall that in such languages, simple unmarked statives can describe states that held prior to the utterance time. Such uses of unmarked statives in Tlingit can be observed in sentences (6)–(9), and are further highlighted in (29a) below.

-

(29)

a.

Kuwak’éi.

b.

Kei kukgwak’éi.

IMPFV.weather.be.nice

FUT.weather.be.nice

‘The weather is/was nice.’

‘The weather will be nice.’

Note, however, that as in many such ‘superficially tenseless’ languages (Matthewson 2006), unmarked statives in Tlingit cannot be freely used to describe future eventualities. To describe states occurring in the future, Tlingit requires use of the so-called ‘future mode’ in (29b). Given facts such as these, I will follow the work of Matthewson (2006) and others by assuming that in Tlingit and other putative ‘optional tense’ languages, unmarked verbs actually contain a phonologically empty T-head, one whose featural value is Non-Future (NFUT). This NFUT feature is given the semantics below.Footnote 15

-

(30)

[[ [Tense NFUT ]i ]]w,t,g = g(i), only if ¬(t < g(i)); undefined otherwise

Thus, a T-head bearing NFUT will only ever denote temporal intervals that do not follow the evaluation time t. An immediate consequence of this semantics is that such NFUT T-heads can easily denote temporal intervals that precede the evaluation time t. They can also denote the evaluation time t itself. Thus, the semantics in (30) correctly predicts that ‘simple unmarked’ stative verbs in these languages can describe states holding either in the past or the present.

A second, more important consequence of (30), however, is that T-heads bearing NFUT are also predicted to denote temporal intervals covering both the utterance time t and a past time t′; such intervals, after all, would not follow t, just as long as t were the final point in the interval. Such ‘past-cum-present’ intervals, however, could never serve as Topic Times in languages possessing only Past and Present, whose semantics in (22) would require the denotation of T to either strictly precede or be equal to the utterance time. Their surprising possibility in languages with ‘optional past tense,’ however, is shown by Matthewson (2006), who observes that in contexts like (31a), speakers of Lillooet (Salish; British Columbia) accept sentences like (31b).

-

(31)

Note that sentence (31b) has no straightforward English translation in context (31a). The issue is, of course, that while Theresa did throw up, Charlie is currently throwing up. Thus, to translate (31b) directly, we would have to simultaneously translate wat’k’ ‘vomit’ as threw up (Past) and is throwing up (Present). Importantly, however, the semantics in (30) would easily predict the possibility of (31b) in scenario (31a). The predicted LF and truth-conditions of (31b) are as in (32) below.

-

(32)

-

a.

LF of (31b): [TP [T NFUT ]i [ PFV [ [Theresa and Charlie] vomit ] ] ]

-

b.

Truth-Conditions:

[[(32a)]]w,t,g is defined only if ¬(t < g(i)). If defined, is true iff

∃e. vomit(e) & Ag(e) = T + C & T(e) ⊆ g(i)

‘There is an event e of Theresa and Charlie throwing up whose run time T(e) is contained in the topic time g(i).’

-

a.

Note that if g(i) were a temporal interval covering the time of Theresa’s vomiting and extending up to the utterance time, it would both satisfy the presupposition of NFUT and render the truth-conditions in (32b) true. We find, then, that the possibility of sentences like (31b) in contexts like (31a) lends important support to the notion that ‘optional past tense’ languages allow the denotation of a (non-past) T-node to be an interval containing both past times and the UT. It should be noted that parallel data can be found in Tlingit as well.

-

(33)

This ability for the Topic Time of a sentence to be an interval containing both the Utterance Time and a past time will be a principle ingredient in our analysis of cessation inferences in Tlingit and other ‘optional past tense’ languages. To begin laying out that analysis, let us first note that if simple, unmarked statives in ‘optional past tense’ languages bear ‘NFUT’ (30), this raises a rather straightforward analysis of the optionality of past tense in those languages. Let us simply suppose that past tense morphology in those languages has precisely the same syntax and semantics as proposed for English past tense in (22)–(25). Note that Past tense will effectively be ‘optional’ in these languages, merely because the additional existence of Non-Future would entail that in sentences describing past eventualities, the T-head needn’t bear the ‘PST’ feature. That is, tense per se is not ‘optional’ in these languages; there is simply more than one tense allowing for the Topic Time to precede the Utterance Time.

But, if the past marking of Tlingit is no different in its syntax or semantics from that of English, what then accounts for the key contrasts in Sect. 1? Why do Tlingit speakers reject conjunctions like those in (6), (7) or discourses like those in (8), (9), when parallel structures are entirely acceptable in English? That is, why are the cessation inferences of Tlingit past marking not defeated in the environments in (6)–(9)? Recalling that our analysis of English cessation implicatures in (25)–(27) correctly predicts that they are defeasible in those contexts, we must conclude that the cessation inferences found with Tlingit past marking have a different nature, and are due to different pragmatic mechanisms.

With this is mind, let us further note that, as we saw in Sect. 3, the cessation inference of Tlingit is cancelled if the speaker explicitly states that they are ignorant concerning the present (Sect. 3.2). This invites the following generalization concerning the contexts where Tlingit cessation inferences do arise.

-

(34)

Key generalization about cessation implicatures in Tlingit

In Tlingit, the cessation inference arises for a past-marked stative whenever the speaker is (assumed / presented to be) knowledgeable about whether the past state in question extends into the present.

Importantly, the environments in (6)–(9)—where we could not cancel the Tlingit cessation inference—all exhibit the key property in (34). In sentences (6) and (7), the past-marked sentence is conjoined with a sentence asserting that the past state continues to hold at present. Therefore, the speaker in these cases is presenting themselves as knowledgeable about whether the past state extends into the present. Furthermore, in the contexts under (8)–(9), the speaker is again presented as knowing (or strongly suspecting) that the event in question is still ongoing. Therefore, the generalization in (34) would correctly predict that the Tlingit cessation inference will still arise in the environments in (6)–(9), unlike the cessation implicatures found in English.

Let us, then, aim to develop an analysis that predicts the key generalization in (34). To begin, let us suppose that there exists in Tlingit a principle that has the following crucial effect: if the speaker can assert a sentence where the Topic Time (TT) contains the Utterance Time (UT), then they must assert that sentence. Put more precisely, let us imagine that the principle enforces the following:

-

(35)

Include UT inside the TT, whenever possible Footnote 16

If all the following conditions hold, then the speaker must use sentence S1, and not S2:

-

a.

Sentences S1 and S2 are identical except for their T-heads (T1 and T2).

-

b.

[[ T1 ]]w,t,g contains both t′ and t, while [[ T2 ]]w,t,g = t′.

-

c.

Both S1 and S2 are ‘assertable’ (i.e., speaker’s knowledge entails them).

-

a.

As we’ll see in a moment, principle (35) will predict the key generalization in (34). First, though, let us briefly note that (35) may itself be a specific subcase of an even more general principle.

-

(36)

Make the TT as large as possible

If all the following conditions hold, then the speaker must use sentence S1, and not S2:

-

a.

Sentences S1 and S2 are identical except for their T-heads (T1 and T2).

-

b.

[[ T1 ]] w,t,g contains both t′ and t″, while [[ T2 ]] w,t,g = t′.

-

c.

Both S1 and S2 are ‘assertable’ (i.e., speaker’s knowledge entails them).

-

a.

The more general principle in (36) could account for the judgment in (37b), regarding the discourse in (37a).

-

(37)

-

a.

Discourse: Dave jumped, then Fred jumped. Mary was dancing.

-

b.

Judgment: The time of Mary’s dancing includes both jumping events.

-

a.

Note that the first sentence in (37a) introduces both the time of Dave’s jumping and the time of Fred’s jumping as possible antecedents for the past T-head of the second sentence of (37a). The principle in (36) would therefore require that the second sentence’s T-head denote an interval encompassing both those antecedent past times, rather than just one of them. Consequently, it would predict the intuition in (37b) that Mary was dancing places the time of both ‘jumpings’ within the Event Time of Mary’s dancing. Be this as it may, since only the more specific principle in (35) is necessary for the proposed account, I will reserve judgment regarding (36).

Let us now observe how the principle in (35) can predict both the key generalization in (34) and the puzzling contrasts with English cessation implicatures observed in Sect. 1. To begin, the principle in (35) would yield a Tlingit cessation implicature as follows.

-

(38)

Thus, the principle in (35) predicts that Tlingit speakers will infer from a past-marked stative that the past state in question does not extend into the present (38gii), just as long as the speaker is assumed to know whether the past eventuality extends into the present or not (38gi).Footnote 17 Therefore, Tlingit speakers will not draw a cessation inference if the speaker is not assumed to know whether the past eventuality extends into the present. In this way, the principle in (35) is able to capture the key generalization in (34).Footnote 18

Furthermore, since English (and other ‘obligatory tense’ languages) lack the NFUT tense of Tlingit, there is not an NFUT competitor (S1) to the use of a past tense sentence (S2) in a context where the speaker can be presumed to know whether the past state in question extends into the present. Therefore, even if we suppose that the principle in (35) (or (36)) is active in English, the reasoning in (38) will not go through for English speakers, and so Tlingit-like cessation inferences will not be drawn for past-tense English sentences in such contexts. Consequently, English sentences like (4) and (5) will not be in any way anomalous, contrary to the structurally parallel Tlingit sentences in (6)–(9).

In summary, the semantic/pragmatic account proposed here can capture the key properties of and differences between the cessation implicatures of English and those of Tlingit. A crucial component of the account is the fact that Tlingit allows the Topic Time of a sentence to cover both a past time t′ and the present t, while English does not. If we assume that such ‘past-cum-present’ TTs are a characteristic property of ‘optional tense languages,’ we can straightforwardly extend this account to other such languages. In this way, our account can capture the typological pattern in (21): past-marking in ‘optional tense languages’ will exhibit the same peculiar cessation inferences found in Tlingit. Consequently, under this analysis, there needn’t be any ‘discontinuous past’ tense in the languages of the world; past-marking exhibiting the properties in (6)–(9) need not differ in its lexical semantics from English PST tense in (22a).

4.1 Absence of cessation inferences with certain embedded pasts

We’ve just seen how the principle in (35) can predict the generalization from Sect. 3.2, that Tlingit cessation inferences are not triggered if the speaker is explicitly ignorant about the present. We also saw in Sect. 3.3 that, in Tlingit, past-marked statives in the complement to past-marked attitude verbs do not trigger cessation inferences. For example, the sentence in (16b)—repeated below—is acceptable in contexts like (16a).

-

(16)

Let us see briefly how the analysis offered above can, when combined with the theory of Ogihara and Sharvit (2012), predict the acceptability of (16b) in context (16a).

For reasons of space, I will need to rely on a relatively informal presentation of Ogihara and Sharvit’s (2012) proposals. Of key importance to us here is their proposal that in sentences like (16b), the embedded past tense receives a so-called de re construal. Simplifying greatly, under such a construal, the embedded past-tense undergoes movement into the matrix VP, creating (roughly) the LF in (39a). A greatly simplified paraphrase of the resulting truth-conditions is provided in (39b).

-

(39)

There are two key features of this analysis to note here. First, because the embedded past-tense undergoes so-called ‘res-movement,’ it becomes an argument of the matrix verb, and no longer serves to locate the time of the embedded event. Consequently, even though the time g(j) denoted by the embedded past tense fails to include the (matrix) UT, nothing is entailed about the time of the uncle’s cooking relative to the time of the speaker’s belief. Secondly, it’s worth noting that our principle in (35) refers only to the T-nodes of matrix sentences. Consequently, that principle does predict (correctly) that there is a cessation inference associated with past-marked yéi x wajeeyín ‘I believed (thus)’ in (16b). It does not, however, generate any chain of reasoning concerning the head ‘[PAST]j’ moved inside the VP in (39a). Consequently, our analysis does not predict any kind of embedded cessation implicature of the form “my uncle cooked really well, but stopped doing so.”

In this way, our analysis predicts the key facts and generalizations from Sect. 3.3. Again, a crucial assumption of this explanation is that the so-called ‘decessive’ suffix in Tlingit is semantically just a temporal pronoun, denoting a past interval of time.

5 Extending the account: The special inferences of past tense perfect(ive)

Thus far, our discussion has focused upon the cessation inference associated with statives marked by optional past tense in Tlingit and other languages. However, as reported by both Leer (1991) and Plungian and van der Auwera (2006), there are yet other types of inferences that these optional past markers can trigger, when they combine with predicates bearing perfective (or perfect) aspect.

Leer (1991) identifies two kinds of inferences that can be contributed by the Tlingit ‘decessive epimode’ when it appears on a verb in so-called ‘perfective mode.’ The first of these will be referred to as the ‘cancelled result’ inference, and is characterized by Leer as follows.

-

(40)

The ‘cancelled result’ inference (Leer 1991 )

“Decessive perfective means that the situation as well as the state of affairs resulting from it was true in the past, but that the state of affairs resulting from the situation has ceased to be valid” (Leer 1991:468).

As his own examples make clear, this cancelled result inference is basically a species of cessation inference, one that concerns the resulting state of the past eventuality, rather than the past eventuality itself. For example, Leer reports that sentence (41a) below implies that the marriage—the state resulting from the event of being married—has ended by the Utterance Time. Similarly, (41b) is reported to imply that the knowledge of the speaker—the state resulting from the learning/realization event—has been lost by the Utterance Time.Footnote 19

-

(41)

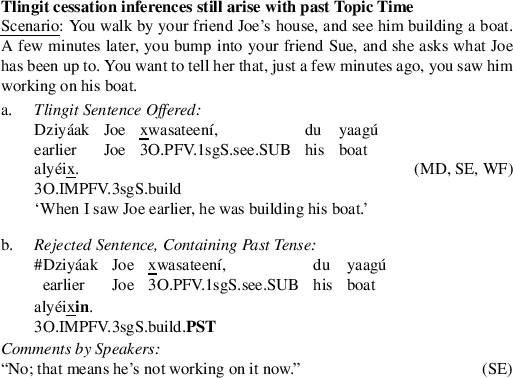

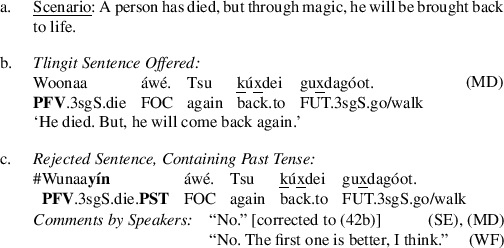

Independent evidence for these cancelled result inferences can be found in contrasts like that in (42) below. In the scenario presented in (42a), the state resulting from the subject’s death—his being dead—is known to still hold at the Utterance Time. Consequently, speakers report that only sentence (42b)—lacking optional past tense—is acceptable in this scenario.

-

(42)

In addition to these cancelled result inferences, Leer (1991) reports that perfective verbs bearing optional past tense in Tlingit can trigger an inference that I will refer to as the ‘unexpected result inference.’ Leer characterizes this inference as follows.

-

(43)

The ‘unexpected result’ inference (Leer 1991 )

A ‘decessive perfective’ in Tlingit can be used to indicate that some “expected result” (Leer 1991:468) failed to occur.

To illustrate, Leer (1991:469) reports that in sentence (44a) below, “the expected result of the priest’s warning the newlywed husband not to touch a knife was that he would heed the warning, but this result was subsequently invalidated by the fact that the husband did touch a knife…” Similarly, Leer (1991:469) reports that in sentence (44b), “the mother roasted some salmon for her son to eat, expecting that he would eat it, but he didn’t.”Footnote 20

-

(44)

Importantly, these generalizations in (40) and (43) are not mere idiosyncrasies of the Tlingit ‘decessive,’ or Leer’s (1991) description of it.Footnote 21 Indeed, similar effects have been widely reported for other languages with optional past tense. Observing this tendency, Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) ultimately include these inferences as part of their characterization of ‘discontinuous past’ markers, stating:

“… The combinations of perfective verbs and discontinuous past markers do exist. The meaning this combination yields can be characterized as the non-existence of a consequent state at the moment of speech (or its ‘current irrelevance’).” (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006:324; emphasis theirs)

Plungian and van der Auwera illustrate their claim with data that are strikingly similar to the Tlingit data in (41) and (44). For example, the optional past-tense suffix -oon in Wolof appears in (45b) to trigger a ‘cancelled result’ inference, where the state resulting from the subject’s departure—their being absent—no longer holds at the Utterance Time (and thus the subject has returned).

-

(45)

a.

dem na

b.

dem-oon na

go.PFV.3sgS

go.PST.PFV.3sgS

‘S/he has gone.’

‘S/he has gone (but is back).’

(Wolof; Plungian and van der Auwera 2006:332)

Furthermore, Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) report that in the Sranan sentence in (46), the presence of the optional past marker indicates that the expected result of the past speech event—that the subject would keep their promise—failed to occur. Thus, this usage of optional past in Sranan is quite reminiscent of the ‘unexpected result’ inference in Tlingit (44a).

-

(46)

In summary, the appearance of optional past tense on verbs bearing perfective (or perfect)Footnote 22 aspect is reported in many languages to trigger one of the following inferences: (i) the state resulting from the event in question fails to hold at the UT, or (ii) some expected result of the event in question failed to occur. Just as with the cessation inferences discussed in Sect. 1, various prior authors have claimed that these special inferences are somehow encoded directly in the lexical semantics of the optional past tense (Leer 1991; Copley 2005; Plungian and van der Auwera 2006; Kagan 2011). In this section, however, I will show that these facts can instead follow from the principle in (35), and so needn’t be due to a special ‘discontinuous’ semantics for the tense-marker. Before I present this analysis, however, I will first present empirical evidence that in the Tlingit language, both the cancelled result and unexpected result inferences are defeasible, and so are not directly encoded in the meaning of the Tlingit decessive.

5.1 Evidence that ‘cancelled’ and ‘unexpected’ result inferences are non-semantic

In Sect. 3, it was shown that the cessation inference associated with past-marked statives in Tlingit fails to arise in (i) certain textually attested examples, (ii) contexts where the speaker is ignorant of the present, and (iii) clauses embedded under other past-marked predicates. In this section, we will see that the cancelled result and unexpected result inferences found with past-marked perfectives in Tlingit also fail to arise in these three cases. On these grounds, it can be concluded that those inferences are in principle defeasible, and so are not directly encoded in the lexical semantics of the Tlingit decessive past-marker.

5.1.1 Absence in examples taken from naturally produced texts

As was found for decessive statives, there are examples of decessive-marked perfective verbs in published Tlingit texts where either a cancelled result or an unexpected result inference would be inconsistent with the surrounding context. Again, for reasons of space, I will provide just one striking example. The following textual excerp contains two decessive perfective verbs.Footnote 23

-

(47)

In the narrative from which (47) is taken, the narrator is explaining how her mother-in-law once showed her that the village of Taakw Aani, near Metlakatla, was originally Tlingit land (though it subsequently became Tsimshian territory). It is clear in the original narrative that the narrator continues to believe her mother-in-law’s claim. Consequently, both the resulting states of the ‘seeing’ in (47a) and the ‘coming to believe’ in (47c) continue to hold at the time of speech. Thus, we can conclude that the decessive perfectives in (47a) and (47c) are not construed with ‘cancelled result’ implications. Furthermore, there is again in context no unexpected results of either the seeing event in (47a) or the ‘coming to believe’ event in (47c). It seems, then, that in their original context, the decessive perfectives in (47a) and (47c) don’t contribute either of the special inferences in (40) or (43), and so those inferences cannot be part of the lexically encoded meaning of the Tlingit decessive.

5.1.2 Cancellation with statements of ignorance

Despite the anomaly of sentences like (42c), it is possible to use a past-marked perfective in Tlingit in contexts where the speaker explicitly doesn’t know whether the result state of the past event extends into the present or not. The dialog in (48) illustrates

-

(48)

In this dialog, Tom reports that he doesn’t know whether the state resulting from Anne and Joe’s marriage—their being married—still holds at present. Nevertheless, in the Tlingit translation of Tom’s statement, a decessive suffix is used in the description of that past marriage event. It follows, of course, that this suffix cannot in this dialog be triggering a ‘cancelled result’ inference, since Tom explicitly denies having such knowledge. Furthermore, there is in context (48) no ‘unexpected’ result of the marriage, and so an ‘unexpected result’ inference here would also be perceived as anomalous. We can therefore conclude that in cases like (48), use of the decessive does not trigger either a ‘cancelled result’ or an ‘unexpected result’ inference, and so those inferences are not directly encoded in the lexical semantics of the Tlingit decessive.

5.1.3 Absence of the inferences in certain embedded clauses

Like the cessation inferences with past-marked statives (Sect. 3.3), the cancelled result and unexpected result inferences with past-marked perfectives appear to be absent in certain embedded clauses. That is, the facts below will show that the generalization in (15) could be amended to the one in (49).

-

(49)

Decessive verbs in the complement to decessive propositional attitude verbs

If a propositional attitude verb in Tlingit is past-marked, then the verb of its complement can also bear past-marking, without contributing any cessation inference, cancelled result inference, or unexpected result inference.

To illustrate, consider the scenario in (50a), as well as the felicitous Tlingit sentence in (50b).

-

(50)

In this scenario, what the speaker believed was simply “my brother knows (came to know) everything”; they did not ever believe “my brother knew everything, but has since forgotten it.” Consequently, the decessive suffix on the embedded perfective verb awsakóowun ‘he knew (had come to know) it’ seems not to contribute the cancelled result implication found in (41b). Similarly, in scenario (50a), the speaker did not ever believe that there was some kind of ‘unexpected result’ that followed from his brother’s knowledge. Consequently, the embedded decessive appears not to contribute in (50b) the unexpected result implication either. Thus, as stated in (49), in structures like (50b), the embedded decessive perfective seems not to trigger either of the inferences in (40) or (43).

There is also another embedded environment where Tlingit decessive perfectives seem not to contribute those special inferences: counterfactual conditionals. The key generalization here is as stated in (51) below.

-

(51)

Decessive verbs in the antecedent of past counterfactuals

If the verb heading the main clause (consequent) of a counterfactual conditional bears decessive (and so is a ‘past counterfactual’), then the verb heading the antecedent must also bear decessive. In such structures, the embedded decessive perfective does not trigger either a ‘cancelled result’ or an ‘unexpected result’ inference.

Before illustrating the generalization in (51), let us first introduce the structure of past counterfactual conditionals in Tlingit. As shown below, such conditionals are formed from (i) a main clause (consequent) headed by a decessive verb (in ‘potential’ mode), and (ii) a subordinate clause (antecedent) headed by a verb also bearing decessive morphology (Leer 1991:476–478).

-

(52)

In addition to illustrating the general form of past counterfactuals in Tlingit, sentence (52b) also nicely illustrates the key generalization in (51). Note that the antecedent of the conditional in (52b) is a decessive perfective verb. Now, it is most natural to assume (at least, provisionally) that past counterfactuals in Tlingit have approximately the semantics of past counterfactuals in English. Consequently, a conditional like that in (52b) states (approximately) that in all the hypothetical situations where the antecedent clause is true, the consequent clause is also true (Ogihara 2000; Arregui 2009; Romero 2015). Thus, (52b) would state that in all the hypothetical situations where the antecedent is true, the addressee gets over their stomachache. Now, given the information in scenario (52a), the addressee gets better in those hypothetical situations where the medicine was drunk and the resulting state / expected consequences of the drinking hold. Therefore, the antecedent clause must be understood as contributing those kinds of situations. In particular, the antecedent could not be felicitously interpreted as contributing situations where the medicine was drunk and either (i) the resulting state of the consumption no longer holds, or (ii) the usual consequences of the consumption don’t happen. Consequently, we must conclude that both the ‘cancelled result’ (40) and ‘unexpected result’ (43) inferences are not contributed by the decessive suffix in the antecedent of (52b).

To put it another way, if the inferences in (40) and (43) were semantic—if they were an obligatory part of the lexical semantics of Tlingit decessive—then the conditional in (52b) would mean something approximately like “If you had drunk this medicine, and the normal result of the drinking either no longer held or never happened, it would have helped you.” Clearly, such a conditional meaning would not be felicitous in scenario (52a), precisely because the medicine is assumed to be an effective cure for stomachaches. We must conclude, then, that those inferences in (40)–(43) are indeed not a part of the lexical semantics of the Tlingit decessive.Footnote 24

Importantly, the reasoning just laid out regarding (52b) would appear to generalize beyond Tlingit, to putative instances of ‘discontinuous past’ in many other languages. Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) report that in many languages containing ‘discontinuous past,’ the putative ‘discontinuous past’ morpheme must appear in the antecedent of past counterfactuals.

-

(53)

Although Plungian and van der Auwera do not provide contexts for these sentences, their translations strongly suggest that the inferences in (40) and (43) are not contributed to the antecedents of these conditionals. Thus, these all appear to be cases where those inferences are not associated with use of a ‘discontinuous past,’ and so support the view that in all putative cases of ‘discontinuous past,’ the special inferences observed with those morphemes are pragmatic effects, and are not part of their lexical semantics.

5.2 Analysis of the cancelled result and unexpected result inferences

The facts above strongly suggest that the cancelled result (40) and unexpected result (43) inferences are defeasible pragmatic effects, and are not semantically encoded in the lexical meaning of the optional past-marking in Tlingit. Furthermore, given our typological argument from Sect. 3.4—as well as the facts concerning counterfactual conditionals in (53)—it is reasonable to conclude that these inferences are likewise pragmatic effects in the other languages where they are reported to occur.

But, if these inferences are indeed pragmatic, how exactly are they triggered? In this section, I argue that in the Tlingit language, they will follow from the general principle in (35), given an important independent fact about Tlingit: its so-called ‘perfective mode’ can be interpreted as a perfect aspect. To put forth this account, I will begin in the following subsection by presenting the evidence that ‘perfective’ verbs in Tlingit are ambiguous, and can be interpreted as perfects.

5.2.1 ‘Perfective’ in Tlingit (and in other languages) can be interpreted as a perfect

Unlike in English, there is in Tlingit no morphological distinction between so-called ‘perfect’ and ‘perfective’ aspect. Rather, there is one morphological verb form—which specialists label ‘perfective mode’—that can be used to translate either English perfective (simple past) or perfect (have V-ed). Importantly, there is evidence to suggest that this broad translational equivalence may be due to an actual ambiguity in the meaning of ‘perfective mode’ in Tlingit. That is, it seems that verbs in ‘perfective mode’ do sometimes have a meaning that is closer to that of a perfect than that of a (past) perfective (Leer 1991:345, 366, 377).

One striking piece of evidence for this ambiguity concerns modification by the adverb yeedát ‘now.’ First, let us note that in discourses like those in (54a,b), English speakers report a contrast in acceptability between the use of ‘now’ with present perfect and its use with past perfective (simple past).Footnote 25

-

(54)

This contrast would follow from our semantics in (22)–(23), if we assume that the understood pragmatic function of ‘now’ in these sentences is to signal that the Topic Time of the second sentence is the present (i.e., now). Given our semantics in (22), such use of ‘now’ would only be consistent with present tense, since past tense requires that the Topic Time is a time in the past.Footnote 26

With this in mind, let us observe that the Tlingit adverb yeedát ‘now’ is entirely compatible with (morphologically) ‘perfective’ verbs. Note that in such cases the ‘perfective’ aspect is most naturally translated into English as a (present) perfect (see (10c) above, as well).Footnote 27

-

(55)

It seems, then, that Tlingit verbs in ‘perfective mode’ can be interpreted as present perfects, rather than as (past) perfectives.Footnote 28 Furthermore, there is evidence that past-marked ‘perfectives’ in Tlingit (decessive perfectives) can be interpreted as past perfects (pluperfects). To begin, in languages that morphologically distinguish perfective and perfect aspect, past perfectives play a very different role in connected narratives from past perfects. That is, past perfectives serve to advance the events of the narrative, while past perfects introduce events that occur prior to the main events of the narrative. To illustrate, in the brief English narrative in (56a), the presence of past perfective in the second sentence places the event of Bill’s sitting after the event of Dave’s walking in the room. By contrast, in (56b), the use of past perfect in the second sentence places the event of Bill’s sitting prior to Dave’s walking in the room.

-

(56)

-

a.

Dave walked in the room. Bill sat down. (walking < sitting)

-

b.

Dave walked in the room. Bill had sat down. (sitting < walking)

-

a.

Interestingly, in Tlingit narratives, it is quite common for decessive perfectives to introduce events occurring prior to the main events of the narrative, just like a past perfect. The following examples, taken from naturally produced texts, illustrate this usage. Each is paired with its original context, to demonstrate that the decessive perfective verb introduces an event preceding the main events of the past narrative. (Note also that in each example, the decessive perfective is translated into English as a past perfect.)Footnote 29

-

(57)