Abstract

This paper analyzes nominal phrases in Swedish with a definite article but no definite suffix on the head noun, which we call quasi-definites (e.g. det största intresse ‘the greatest interest’). These diverge from the usual ‘double definiteness’ pattern where the article and the suffix co-occur (e.g. det största intresse-t ‘the greatest interest-def’). We give several diagnostics showing that this pattern arises only with superlatives on an elative (‘to a very high degree’) interpretation, and that quasi-definites behave semantically as indefinites, although they have limited scope options and are resistant to polarity reversals. Rather than treating the article and the suffix as marking different aspects of definiteness, we propose that both are markers of uniqueness and that the definite article signals definiteness that is confined to the adjectival phrase and combines with a predicate of degrees rather than individuals in this construction. The reason that quasi-definites do not behave precisely as ordinary indefinites has to do with their pragmatics: Like emphatic negative polarity items, elative superlatives require that the assertion be stronger (≈ more surprising) than alternatives formed by replacing the highest degree with lower degrees, and have a preference for entailment scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

In double definiteness varieties of Scandinavian (Swedish, Norwegian, and Faroese), a definite article is ordinarily accompanied by a definite suffix, as in (1), from Swedish.

-

(1)

This situation opens up the possibility for shades of gray between full definiteness marking and complete lack thereof, and this paper addresses one such case. An example of the construction we will focus on is given in (2a), where the article det ‘the’ appears without a corresponding definite suffix on the head noun intresse. This example forms a minimal pair with (2b), where the suffix is present (Delsing 1993).

-

(2)

-

a.

Vi följer utvecklingen med det största intresse.

‘We are following the development with the greatest interest.’

-

b.

Det största intresse-t riktades mot Allsvenskan.

‘The greatest interest- def was directed to Allsvenskan.’

-

a.

We use the term quasi-definite as a label for this kind of noun phrase in double-definiteness varieties of Scandinavian (definite article, bare head noun, and no relative clause; see below on the relevance of relative clauses). Although quasi-definites are found in for example Norwegian as well, we will limit our attention to Swedish in this article.

This paper concerns the obvious question: What allows the article to occur without the suffix in (2a)? One possibility is that the article and the suffix represent different aspects of definiteness. For example, Julien (2005) suggests that the suffix encodes specificity (≈ existence) while the article encodes maximality (≈ uniqueness), though not directly as an explanation for this phenomenon. This analysis is adopted by Alexiadou (2014). Another possibility, also proposed by Julien (2005) as a separate claim, is that the article can relate to a different part of the meaning, operating within the adjectival projection. As evidenced by the very position Julien (2005) holds, it is possible to maintain both of these claims simultaneously, so they are not mutually exclusive, although they are alternative strategies for explaining the phenomenon of quasi-definites. Alternatively, it may be that quasi-definites are really definite, and the lack of a suffix is misleading. Or perhaps quasi-definites are not definite at any level, and the definite article functions under these circumstances as a semantically vacuous expletive. We may also consider the possibility that the article signals reference to kind individuals, as proposed by Aguilar-Guevara and Zwarts (2010) for the ‘weak definites’ in English discussed by Carlson and Sussman (2005).

Let us summarize the range of analytical options more systematically.

-

1.

The degree analysis: Quasi-definites are definite at the level of degrees, and the article may signal definiteness at this level, while the suffix signals definiteness only at the level of individuals.

-

2.

The expletive analysis: There is no definiteness at any level in quasi-definites; the article is semantically vacuous.

-

3.

The aspects-of-definiteness analysis: Quasi-definites carry a uniqueness presupposition, marked by the article, but do not signal existence or specificity, hence the absence of the suffix.

-

4.

The kind analysis: Quasi-definites are definite at the level of kinds, and the definite article signals definiteness at the kind level, while the suffix does not.

We will argue for the degree analysis, and thereby explicate Julien’s (2005) intuition that quasi-definites exhibit “a special kind of definiteness” which is “confined to the adjectival phrase” (p. 41). The analysis is made explicit in Sect. 5; the alternative hypotheses are addressed individually in Sect. 6. We argue that the article and the suffix do not encode different aspects of definiteness, as Julien (2005) proposes; rather, both are markers of uniqueness, as Coppock and Beaver (2015) propose for English the. In a quasi-definite noun phrase, the definite article signals uniqueness with respect to a predicate of degrees rather than individuals.

An advantage of the degree analysis over the others is that it sheds light on the very restricted distribution of quasi-definites. As we show in Sect. 2, the presence of a superlative adjective in (2a) is not an accident; the quasi-definite pattern systematically arises with superlatives. Moreover, several diagnostics show that the superlatives that occur in this construction have a special elative interpretation, meaning ‘to a very high degree’, rather than invoking a comparison class (Teleman et al. 1999). This can be explained under the assumption that the definite article can be interpreted within the adjectival projection and signify uniqueness with respect to a property of degrees.

Our analysis implies that quasi-definites are not definite at the level of ordinary individuals, a consequence which is supported by a number of facts, discussed in Sect. 3. As previous scholars have argued (Delsing 1993; Julien 2005), quasi-definites behave semantically more like indefinites than definites, and we offer additional evidence in support of this. However, we also show that they do not behave entirely like ordinary indefinites, as they have limited scope options and are resistant to polarity reversals. In these respects, they are similar to weak definites, but there are crucial differences between quasi-definites and weak definites, both in English and in Swedish. So this phenomenon illustrates a different kind of intermediacy between definite and indefinite.

We argue in Sect. 4 that the special scope behavior of quasi-definites has its source in the pragmatics of emphasis. Elative superlatives, we propose, are much like emphatic polarity items (such as a whit) as analyzed by Krifka (1995), Israel (2011), and Chierchia (2013), and like even as analyzed by Karttunen and Peters (1979) among others: the clause they participate in must be stronger (more noteworthy/surprising/informative) than alternative assertions. The alternatives in this case are formed by substituting the highest degree with a smaller degree. Nevertheless, only some quasi-definites are negative polarity items, and many are compatible with both positive and negative environments, given an appropriate set of background assumptions and surrounded by lexical items with appropriate content. Quasi-definites thus provide a case where inherently emphatic scalar items are found beyond the realm of polarity sensitivity.

1.2 The landscape of definiteness mismatches

The construction we focus on here is one of several types of cases in which the definite article and the suffix do not co-occur in Scandinavian. Before we delve into quasi-definites, let us place them in the context of other such constructions. Recall from above that a definite article usually co-ocurs with a suffix in double definiteness varieties of Scandinavian.Footnote 1

-

(3)

There are two kinds of exceptions to this correlation: a suffix unaccompanied by an article, and an article unaccompanied by a suffix.

A definite suffix regularly occurs without a definite article whenever there is no pre-nominal modifier. For example, huset means ‘the house’ in Swedish. If a den or det occurs with a single noun and no intervening adjective, it is stressed, indicated by italics, and receives a demonstrative interpretation.Footnote 2

-

(4)

-

a.

-

b.

-

a.

An interpretation of det as a definite article in (4b) is not available. We can show this with associative (‘bridging’) anaphora, which definites can do and demonstratives cannot.Footnote 3

-

(5)

-

a.

I wanted to use my bicycle but the saddle is broken.

-

b.

??I wanted to use my bicycle but this saddle is broken.

-

a.

Example (5b) cannot be used to refer to the saddle of the introduced bicycle if the saddle is not independently salient in the context. The same is true for Swedish noun phrases containing det or den followed immediately by a noun:

-

(6)

-

a.

-

b.

-

a.

Normally, the definite article appears whenever there is an adjectival modifier, but adjectival modifiers can appear unaccompanied by a definite article in some cases. These include name-like expressions and common collocations often involving superlatives (Teleman et al. 1999; Dahl 2015; Simonenko 2007; Borthen 2007, 2008). (Since the examples can for the most part be translated word-for-word, we omit interlinear glosses in the following. If the noun in question has a definite suffix, this will always be indicated in the translation; otherwise the noun lacks the definite suffix.)

-

(7)

Nationella strokekampanj-en startar för sista gång-en.

‘The national stroke campaign- def is starting for the last time- def’

If we were to remove det from (3) above, the result would not be ungrammatical in Swedish, but it would have a name-like interpretation, as in the following example.

-

(8)

Vi träffas på Stora Hotell-et.

‘We’ll meet at Big-Hotel-def.’

Our focus will not be on cases where a suffix occurs without an article, but rather on the opposite type of case where a definite article occurs without the definite suffix. This is relatively common when the noun is modified by a relative clause.

-

(9)

Chefen tackade för det stora arbete [vi lagt ner på uppgiften].

‘The boss thanked us for the great effort [we had made on the task].’

If the relative clause were to be removed from (9), the example would become ungrammatical; a definite suffix would rescue the sentence.

-

(10)

Chefen tackade för det stora arbete-*(t).

‘The boss thanked us for the great effort-def.’

Although it has been argued that the presence or absence of the suffix can affect interpretation (Dahl 1978), drop of the suffix is relatively free in the presence of a relative clause. As (10) shows, this freedom is not present otherwise.Footnote 4

However, there are certain cases in which a definite article can occur without a definite suffix even when no relative clause is present, and this is the type of case we will analyze here: noun phrases with a definite article, no definite suffix and no relative clause (which we call quasi-definites). Example (2a) above contains a quasi-definite. Further examples include the following.Footnote 5

-

(11)

De vackra färgerna lyser upp den gråaste dag.

‘The beautiful colors light up the grayest day.’

-

(12)

Den som aldrig annars kan äta kakor blir överlycklig för den slätaste bulle.

‘Someone who can’t otherwise eat cookies gets overjoyed about the plainest bun.’

-

(13)

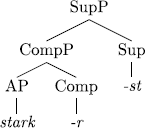

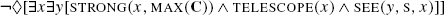

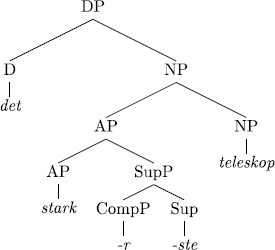

Radioteleskopen gjorde det möjligt att “se” sådant som inte kunde iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop.

‘The radiotelescope made it possible to “see” things that couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope.’

-

(14)

Hon visste att det kortaste ärende kunde ta ett par timmar.

‘She knew that the shortest errand could take a couple of hours.’

-

(15)

Uppenbarligen fyller dessa gamla gregorianska kyrkosångare ett behov som inte den smartaste skivbolagsdirektör hade en aning om att det existerade.

‘Apparently these old Gregorian church singers fulfill a need that the smartest record company director didn’t have any idea existed.’

Note already the wide variety of lexical items: This shows that we are dealing with a fully productive pattern, not just a limited set of fixed expressions. A more thorough sampling of the data is given throughout the discussion below.

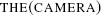

2 The adjective: Always an elative superlative

Examples (11)–(15) all contain superlatives. According to the Swedish Academy Grammar (Teleman et al. 1999), “a formally definite noun phrase with the head word in the indefinite form” (where the ‘indefinite form’ refers to the form of the noun lacking a definite suffix) may be found in the presence of what they call absolute superlatives, denoting “a very high degree of a quality”, where the “comparison class is neither given explicitly nor by the context or speech situation”.Footnote 6 This contrasts with what we will refer to simply as ‘ordinary’ uses of superlatives, as in the tallest kid (in my class), which characterize an individual who has the indicated property to a greater degree than all others in a given comparison class (in this case kids in the class). Instead of ‘absolute’ to describe the ‘to a very high degree’ reading which is not relative to any comparison class, we will use the term ‘elative’, in order to make it clear that the distinction in question is not related to the distinction between ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ or ‘comparative’ readings of superlatives discussed for example by Szabolcsi (1986) and Heim (1999). In our terms, then, what the Swedish Academy Grammar says is that elative superlatives are found in quasi-definites. In this section we give corpus evidence and diagnostics for a stronger claim: Quasi-definites always contain an elative superlative.

2.1 Restriction to superlatives

Above, we defined a quasi-definite as a noun phrase in which there is a definite article, a head noun in the bare form, and no relative clause. Recall that definite articles only appear in the presence of adjectival modifiers, so it follows from this definition that quasi-definites always contain an adjectival modifier as well as a definite article. Nothing in the definition requires this prenominal modifier to be a superlative, though; in principle one could find examples of quasi-definites that have a non-superlative prenominal modifier if they existed.

To find out whether such cases do exist, we did a broad search in a part-of-speech tagged corpus of newspaper text,Footnote 7 and searched for den or det, followed by an adjective, followed by a noun without a definite suffix. After selecting 1000 results to look at and filtering out cases that do not meet the definition of a quasi-definite, we were left with 138 examples that did meet the definition. 90 of these contained a superlative adjective, 19 contained the fixed expression den milda grad ‘the small degree’, two contained the archaic expression (den ljusnande framtid ‘the brightening future’, from an old song), and the remaining 27 appear to have been editing mistakes, based on the judgment survey we carried out with ten native Swedish speakers described in the Appendix. Since superlatives are not more common than non-superlatives in attributive position, we can be reasonably confident that we would have found a non-superlative in this sample if they were productively allowed in this construction. We therefore conclude that quasi-definites in Swedish must contain a superlative adjectival modifier.Footnote 8

In order to have a broad and varied empirical base for our investigation, we carried out additional searches for quasi-definites in the newspaper, blog and fiction corpora in Språkbanken and made a random selection of 200 examples which we refer to throughout the paper as the Korp-200 sample.Footnote 9

2.2 Elative superlatives

Recall that on an elative interpretation, slätaste ‘plainest’, for example, means ‘plain to a very high degree’, rather than ‘plainer than all other members of the comparison class’.Footnote 10 Some languages have dedicated elative morphemes: Berlanda (2013) and Beltrama (2014) for example discuss the Italian -issimo suffix (as in bellissimo ‘extremely beautiful’), Matushansky (2008) discusses a special elative suffix -ejš- in Russian, and elative constructions in several different languages are discussed by Oebel (2012). Elative uses of superlatives can also be found in English with periphrastic most in combination with indefinite determiners (Quirk et al. 1985), e.g.:

-

(16)

We had a most pleasant supper.

-

(17)

Mrs. Wheatley has several most delightful specimens of her improved ability… [from The Portfolio by Oliver Oldschool]

An elative interpretation seems to be available even for morphological superlatives in combination with a definite article:

-

(18)

We are following the development with the greatest interest.

This is easily understood to mean, ‘We are following the development with extremely great interest’ (rather than ‘… with interest that is greater than all others.’). In the glosses of quasi-definites below, we rely on this kind of interpretation in English.

It is only in connection with elative superlatives that the Swedish Academy Grammar (Teleman et al. 1999) notes that a definite article may co-occur with a bare noun (setting aside cases where the noun is modified by a relative clause as in (9)). Let us consider the hypothesis that this listing of such environments is exhaustive, so superlatives in quasi-definites always have an elative interpretation. If quasi-definites always contain an elative superlative, then an elative interpretation should arise whenever the suffix is absent. For example, in (19a) (shortened from (13)), what is being described should be a telescope of the strongest possible variety, not the strongest among a given group of telescopes, as in (19b).

-

(19)

-

a.

Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop.

‘The star couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope.’

(I.e. a telescope of maximum strength)

-

b.

Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop-et.

‘The star couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope-def

(among the relevant telescopes).’

-

a.

Indeed, these glosses fit with native speakers’ intuitions as to the meanings of these examples. But how can we really tell that we do not have an ordinary interpretation of the superlative in these cases? Suppose the comparison class is all telescopes ever built, or even all telescopes imaginable. Then the elative interpretation starts to come very close to the ordinary interpretation.Footnote 11 In other words, Teleman et al.’s (1999) claim is not entirely straightforward to verify, because it is hard to distinguish a telescope of maximum strength from a telescope that is stronger than all others in a sufficiently large comparison class.

We therefore offer two diagnostic tests in support of the claim that the superlatives that occur in quasi-definites are interpreted elatively. The first involves modification with näst ‘next’, as in ‘next/second best’. Ordinary superlatives invoke an ordering of items in the comparison class, hence accept modification with next or second, as in:

-

(20)

John is the second smartest boy in his class.

Elative superlatives in English, formed with periphrastic most, do not accept this kind of modification:

-

(21)

We had a (*second)-most delightful dinner with them yesterday.

If quasi-definites involve elative superlatives, then näst should not be able to modify a superlative adjective inside a quasi-definite. That prediction is borne out:

-

(22)

-

a.

*Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas med det näst starkaste teleskop.

‘The star couldn’t be observed with the second strongest telescope.’

-

b.

Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas med det näst starkaste teleskop-et.

‘The star couldn’t be observed with the second strongest telescope- def.’

-

a.

-

(23)

-

a.

*Den som aldrig annars kan äta kakor blir överlycklig för den näst slästaste bulle.

‘Someone who can’t otherwise eat cookies gets overjoyed about the second plainest bun.’

-

b.

Den som aldrig annars kan äta kakor blir överlycklig för den näst slästaste bulle-n.

‘Someone who can’t otherwise eat cookies gets overjoyed about the second plainest bun- def.’

-

a.

Second, observe that it is not possible to add an explicit comparison class to a quasi-definite:Footnote 12

-

(24)

*De vackra färgerna lyser upp den gråaste dag av alla.

‘The beautiful colors light up the grayest day of all.’

-

(25)

*Den som aldrig annars kan äta kakor blir överlycklig för den slätaste bulle av alla.

‘Someone who can’t otherwise eat cookies gets overjoyed about the plainest bun of all.’

This fact is a straightforward consequence of the fact that elative superlatives do not involve comparison among a set of individuals.

Finally, elatives behave differently from ordinary superlatives in the plural. Plural superlatives on a non-elative interpretation pick out pluralities whose members may very well differ from each other with respect to the relevant gradable property. For example, the tallest mountains picks out a plurality whose members may not all have the property tallest mountain. There is some threshold of tallness above which we find the mountains satisfying the plural superlative description (Stateva 2005; Fitzgibbons et al. 2009; Hackl 2009; Yee 2011). The same is not true for plural elative superlatives. Take the following examples:

-

(26)

Men allt är gjort i de lättaste material.

‘But everything is done in the lightest materials.’

-

(27)

…där alla arbetarna sitter tysta och sammanbitna och täljer på de underligaste trästycken.

… where all the workers sit silently with their mouths clenched and carve the strangest wooden pieces.

The elativity distributes, as it were, across the individuals of the plurality; (26) implies that each of the materials involved is of maximum lightness, and in (27) each of the wooden pieces is of maximum strangeness.

We conclude that it is indeed the case that the superlative adjective in a quasi-definite is interpreted elatively. Unlike its competitors, the analysis according to which the definite article signals definiteness with respect to a property of degrees has the potential to explain this special connection to a degree-based phenomenon. We will show exactly how this works in Sect. 5. Another prediction of the analysis on which the definite article signals definiteness at the degree level (and not the individual level) is that quasi-definites as a whole are indefinite. The next section is devoted to that issue.

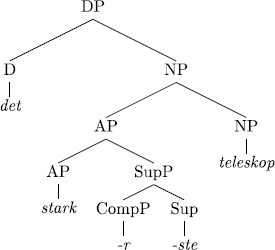

3 Definiteness

Morphologically, quasi-definites give mixed signals as to whether they are definite. On the one hand, they lack a definite suffix. On the other hand, they contain a definite article. The morphology of the adjective also signals definiteness; the superlative adjective occurs in the ‘weak’ form (e.g grå-ast-e ‘gray-sup-w’, as opposed to the strong form grå-ast ‘gray-sup’), and a weak ending on an adjective normally signals definiteness in a singular noun phrase. Any adjectival modifiers following the superlative in a quasi-definite will occur in the weak form as well, as Teleman et al. (1999) point out, using the following example:Footnote 13

-

(28)

Which of the morphological indicators should we believe? Are quasi-definites definite or indefinite, or neither, or both, or somewhere in between? Teleman et al. (1999) and Julien (2005) contend that they are indefinite; Stroh-Wollin and Simke (2014, p. 101) write that they are “semantically quasi-definite”, although they do not explicate this notion.Footnote 14 In this section, we will establish that they are semantically indefinite, although they do not behave entirely like ordinary indefinites.

3.1 Presentational constructions

It is well-known that presentational there-constructions in English are subject to a definiteness restriction (Milsark 1977; Barwise and Cooper 1981; McNally 1992; Abbott 1997; Ward and Birner 1995; Zucchi 1995; Francez 2009, i.a.). As in English, presentational constructions are subject to a definiteness restriction in Swedish:

-

(29)

Det sitter {en prinsessa, *prinsessan} i tornet.

‘There sits {a princess, *the princess} in the tower.’

And as noted by Delsing (1993) and Julien (2005), quasi-definites can occur in presentational constructions:

-

(30)

Det sitter den vackraste prinsessa i tornet. (Delsing 1993)

‘There sits the most beautiful princess in the tower.’

Quasi-definites thus pattern with indefinites with respect to this diagnostic.Footnote 15 (If the suffix were present in (30), the example would no longer be acceptable.)

Example (30) is stylistically marked; Swedish speakers report that it sounds like so-called sagostil, the style of fairy tales. It is possible to find such examples in modern texts though.

-

(31)

Det finns inte den minsta anledning att vara orolig.

‘There isn’t the slightest reason to be worried.’

-

(32)

Om det finns den minsta risk för detta eller osäkerhet om …

‘If there is the slightest risk of that or uncertainty about …’

As we will discuss more below, quasi-definites involving minsta are a bit special in that they appear to be negative polarity items. But this pattern is not limited to such cases. Teleman et al. (1999, Volume III, p. 80) give the following example:

-

(33)

Det härskade (den) största oordning i huset.

‘There was the greatest disorder in the house.’

And a wider range of examples can be found through Google searches:

-

(34)

Det rådde den allra största vänskap mellan de två skolmästarna.

‘There was the absolute greatest friendship between the two schoolmasters.’

-

(35)

Nu såg han oavvänt på sin hustru, såg djupt in i hennes raffinerat melerade nötbruna ögon, in i de rena ögonvitorna där det fanns den allra lättaste anstrykning av mjölkaktigt blått.

‘Now he looked steadily at his wife, looked deep into her refined mottled hazel eyes, into the pure whites of the eyes, where there was the absolute lightest touch of milky blue.’

So quasi-definites are used productively in the pivot of presentational constructions.

3.2 Anaphora

A further indication that quasi-definites are semantically like indefinites is that they have limited anaphoric potential in entailment-cancelling environments. Recall that while ordinary indefinites do establish discourse referents for subsequent anaphora (as in A man came in. He sat down), the ‘lifespan’ of the discourse referents that they establish, to use Karttunen’s (1976) terminology, is limited to the scope of surrounding entailment-cancelling operators such as negation. This is not true of definites, hence the following contrast:

-

(36)

-

a.

I didn’t see the movie last night. It looked boring.

-

b.

I didn’t see a movie last night. # It looked boring.

-

a.

Example (36b) is unacceptable on a narrow-scope reading for the indefinite, where the first clause means that there was no movie seen by the speaker (‘It is not the case that there is a movie that I saw last night’).

We see the same kind of effects with quasi-definites. For example, the quasi-definite under the negated possibility modal in (37) cannot be resumed by a pronoun. (Notice that the translation to English is also quite strange.)

-

(37)

Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop. #I själva verket finns det tusentals planeter som inte kan iakttas med det.

‘The star couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope. #In the universe there are thousands of planets that cannot be seen with it.’

Note that (37) would be rescued by adding a definite suffix to teleskop; in that case the meaning would be ‘The star can’t be observed with the strongest telescope’, where ‘the strongest telescope’ refers to a particular telescope.

Similar effects can be found in the absence of negation, in the presence of a modal or a generic interpretation. For example, (38a) (a naturally occurring and poetic bit of wisdom containing the modal kan ‘can’) cannot be followed by (38b).

-

(38)

-

a.

Ett litet skämt kan skingra det tätaste allvar i .

‘A little joke can disperse the tightest seriousness.’

-

b.

#Jag vet inte om det finns något annat som kan skringra det i .

‘I don’t know if there is anything else that can disperse it i .’

-

a.

We also find this kind of effect in sentences with a generic or habitual interpretation, where the quasi-definite cannot be resumed outside the scope of the generic context:

-

(39)

-

a.

Även det enklaste anfall i börjar med försvarsspel.

‘Even the simplest attack begins with defense.’

-

b.

#Vi kommer att öva på det anfallet i idag.

‘We will practice that attack i today.’

-

a.

Modals and genericity can also limit the anaphoric potential of indefinites, as in the following English examples:

-

(40)

-

a.

A little joke can lighten up a serious situation i .

-

b.

#I don’t know of anything else that can lighten it i up.

-

a.

-

(41)

-

a.

Even a simple attack i begins with defense.

-

b.

#We will practice {it, that attack} i today.

-

a.

The same is true of indefinites in Swedish. This is not characteristic of definites; anaphora would be possible if we were to replace a with the in the above examples. So quasi-definites have a limited ability to establish discourse referents, and in this respect they behave like indefinites.

But quasi-definites do sometimes license anaphora. An anaphor can be used to refer back to the princess in (30), for example:

-

(42)

-

a.

Det sitter den vackraste prinsessa i i tornet.

‘There sits the most beautiful princess i in the tower.’

-

b.

Hon i väntar på att prinsen ska komma.

‘She i is waiting for the prince to come.’

-

a.

Presentational constructions are part of a larger class of examples in which the existence of an entity satisfying the description is at some level the main point of the utterance, such as (43a), which can be followed by (43b):

-

(43)

-

a.

Här gömde sig en rätt fylld med det möraste lamm i .

‘Here was hidden a dish filled with the tenderest lamb i .’

-

b.

Det i formligen smälte i munnen.

‘It i practically melted in the mouth.’

-

a.

In general, when existence is entailed, anaphora is possible.

And like indefinites, quasi-definites license anaphors from the antecedent of a conditional, as in the following examples (from Google):

-

(44)

Har du den minsta fråga i , ställ den i här eller SMS:a till …

‘If you have the slightest question i , pose it i here or text to …’

-

(45)

Om du har den minsta chans i att kunna göra Bibeläventyret i ditt arbete eller på din fritid—ta den i och gå kursen!

‘If you have the slightest chance i to do the Bible Adventure through your work or in your free time—take it i and do the course!’

As is well-known, indefinites also license anphora from the antecedent of a conditional (Geach 1962; Heim 1982; Kamp 1981; Kamp and Reyle 1993).

-

(46)

If a farmer i owns a donkey j , then he i beats it j .

We also find quasi-definites licensing anaphora from the consequent of a conditional.

-

(47)

Även den skickligaste simmare i är chanslös, om han i hamnar mitt i en sådan ström.

‘Even the most skillful swimmer i is without a chance, if he finds himself in that kind of current.’

This is true of indefinites as well (Barker and Shan 2008):Footnote 16

-

(48)

A farmer beats a donkey if he owns it.

So quasi-definites have indefinite-like anaphoric potential (setting aside their limited scope options).

Thus quasi-definites do introduce discourse referents (just as indefinites do), although their lifespan is limited in the context of entailment-cancelling operators including negation, modals, generic operators, and conditionals (just as with indefinites).

3.3 Uniqueness

Julien (2005) proposes to analyze the definite article in Swedish as a marker of uniqueness (maximality, to be precise, in order to accommodate plural cases), and the suffix as a marker of what she calls ‘specificity’. We will address the claim about the suffix in Sect. 5.1.1. Let us now consider whether quasi-definites signal uniqueness at the level of ordinary individuals.

It turns out that they do not. We can see this using a VP-ellipsis test:

-

(49)

Logotypen gör nu det proffsigaste intryck och det gör webbsidan också.

‘The logotype gives the most professional impression and so does the web page.’

-

(50)

Hon kommer att kläs i den vackraste skrud, och det ska hennes syster också.

‘She is going to be dressed in the most beautiful garb, and her sister will be, too.’

-

(51)

Hans lagar den finaste mat, och det gör Rikard också.

‘Hans prepares the finest food, and Rikard does too.’

None of these examples implies that the two protagonists bear the relevant relation to the same object (give the same impression, wear the same clothes, or prepare the same food). They imply only that both bear the relevant relation to something of the relevant sort that is high on the relevant scale (e.g. give an extremely professional impression). So the definite article does not signal uniqueness at the level of ordinary individuals in quasi-definites.

Taken together, the evidence we have seen so far in Sect. 3 shows that quasi-definites are semantically indefinite.Footnote 17 This conclusion is very much in line with what previous scholars have concluded. Julien (2005), for example, also implies that quasi-definites are semantically like indefinites. She writes (p. 41), “Since this definiteness is confined to the adjectival phrase, it does not give rise to the readings that go with definiteness features that are located in n or D,” where the definiteness features that are located in n and D are, according to Julien, specificity and uniqueness, the (only) two components of definiteness. As noted above, Teleman et al. (1999) also claim that this construction is semantically indefinite. So this conclusion is not particularly controversial, although the evidence we have given here has not been brought to bear on the issue. What has not been argued before is that quasi-definites do not behave entirely like ordinary indefinites, as we discuss next.

3.4 Scope

Quasi-definites have more limited scope options than ordinary indefinites. An ordinary indefinite, as in example (36b) from above (“I didn’t see a movie last night. #It looked boring.”), would be acceptable on a wide-scope reading: ‘There is a movie that I didn’t see last night’. (To bring out the wide-scope reading, imagine the sentence in the context of the question, ‘Why are they upset with you?’) Ordinary Swedish indefinites can also take wide scope over negation; take for example:

-

(52)

Jag hälsade inte på en gäst igår (och det visade sig att hon var väldigt berömd).

‘I didn’t greet a guest yesterday (and it turned out that she was very famous).’

And yet there is no wide-scope reading for the quasi-definite in (37) from above, repeated here as (53).

-

(53)

Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop. #I själva verket finns det tusentals planeter som inte kan iakttas med det.

‘The star couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope. #In the universe there are thousands of planets that cannot be seen with it.’

If there were a wide-scope reading, then the anaphor should be licensed.

The same observation can be made for (15) above, repeated here:

-

(54)

Uppenbarligen fyller dessa gamla gregorianska kyrkosångare ett behov som inte den smartaste skivbolagsdirektör hade en aning om att det existerade.

‘Apparently these old Gregorian church singers fulfill a need that the smartest record company director didn’t have any idea existed.’

This does not have a reading that could be paraphrased, ‘There was an extremely smart record company director who didn’t know that the need for these Gregorian church singers existed’, and subsequent anaphora would only be appropriate if a definite suffix were added to the head noun.

We can also see scope restrictions with respect to modals in the following example, a shortened version of (14):

-

(55)

Det kortaste ärende kunde ta över en halvtimme.

‘The shortest errand could take over a half hour.’

This does not have a reading: “There was a very short errand that could take over half an hour.” It has only an interpretation where the possibility modal takes wide scope over the existential quantifier. The same is true in the following example:

-

(56)

Att som före detta filmstjärna på bio tvingas ta steget ner till tv-seriernas värld kan knäcka den kaxigaste skådis.

‘To as a previous film-star be forced to step down to the TV-series world can crack the cockiest actor.’

This example has no reading ‘There is an extremely cocky actor that stepping down to the TV-series world can crack.’

Comparatives provide another environment where quasi-definites behave slightly differently from ordinary indefinites. Consider the following two examples:

-

(57)

Han är teknikern, som trollar med klubban och pucken, elegantare och kvickare än den flinkaste ryss.

‘He’s the technician who conjures magic with his club and the puck, more elegant and quick than the nimblest Russian.’

-

(58)

Ett VM-brons i fotboll är värt betydligt mer än den ädlaste medalj i brottning, det ska ni veta.

‘A World Cup bronze in soccer is worth significantly more than the noblest medal in wresting, I’ll tell you that.’

In (57), we do not get a reading, ‘there is an extremely nimble Russian that he is more elegant and quick than’. Rather, the reading is like the one that English any gets in comparative constructions: ‘He is more elegant and quick than any (extremely nimble) Russian.’ Analogous observations can be made for (58). This behavior can be seen as a scope restriction, depending on the analysis; see Aloni and Roelofsen (2014) on indefinites in comparatives.

However, it is possible for quasi-definites to take wide scope. An example of this is the following constructed example:

-

(59)

Alla rummen var målade i den fulaste färg—en illgrön nyans som påminde om Lisebergskaninerna.

‘All of the rooms were painted in the ugliest color—a sickly green shade that was reminiscent of the Liseberg rabbits.’

This sentence has a wide-scope reading for the quasi-definite, which can be paraphrased, ‘There is an extremely ugly color that all the rooms were painted in.’ and the existence of this reading is shown by the continuation, which identifies the exact color in question. So quasi-definites appear to have a greater penchant for narrow scope than ordinary indefinites, but are not completely resistant to wide scope interpretations.

4 Polarity and emphasis

4.1 Polarity

We established in the previous section that quasi-definites are indefinites that typically take narrow scope, but can under some circumstances take wide scope, as shown in (59). In this section, we connect these facts to their pragmatics. We argue that quasi-definites, because they contain elative superlatives, are inherently emphatic, and this places certain restrictions on their distribution, and renders sentences containing them resistant to polarity reversals.

Indeed, some quasi-definites are negative polarity items, as previous scholars have noted.Footnote 18 Julien (2005, p. 36) gives the following example from Norwegian, noting that den fjernaste aning ‘the faintest idea’ is an “idiomatic negative polarity item”:

-

(60)

Ho hadde ikkje den fjernaste aning. [Norwegian]

‘She didn’t have the remotest idea.’

The most idiomatic correlate in Swedish is den blekaste aning, as in the following example.

-

(61)

Justitieministern har inte den blekaste aning om hur det är att sitta i fängelse.

‘The Minister of Justice doesn’t have the faintest idea about what it is like to be in prison.’

Removing negation in (61) leads to unacceptability.Footnote 19

Quasi-definites involving minsta ‘smallest/least’ also tend to be restricted to NPI-licensing environments, and some are listed as negative polarity items by Teleman et al. (1999, Volume 4, p. 187ff.). Here is one example:

-

(62)

Levern har inte visat det minsta tecken på avstötning.

‘The liver hasn’t shown the slightest sign of rejection.’

In the Korp-200 sample, minsta is used in combination with several different nouns including aning ‘idea’, ansvar ‘responsibility’, spår ‘trace’, tecken ‘sign’, lust ‘desire’, risk ‘risk’, intresse ‘interest’, and inslag ‘element’, and all occurred in a negative polarity item licensing environment.Footnote 20 These kinds of examples can be classified as ‘minimizer NPIs’, along with English examples like an iota and a red cent, as they describe very small things.Footnote 21

But there are also examples in positive environments, as we have seen above. Some of these involve största ‘biggest’, the antonym of minsta ‘smallest’, as in (2a) above, and in:

-

(63)

Även det största problembarn är lämpat för en ljus framtid.

‘Even the biggest problem-child is suited for a bright future.’

Other cases of quasi-definites in positive environments include (26) and (43a), repeated here:

-

(64)

Här gömde sig en rätt fylld med det möraste lamm.

‘Here was hidden a dish filled with the most tender lamb.’

-

(65)

Men allt är gjort i de lättaste material.

‘But everything is done in the lightest materials.’

We can see that these examples are not in downward-entailing environments by applying the usual substitution tests; for example, (65) does not entail that everything is done in the lightest materials made of cotton.

In cases like these, adding negation can make the sentence sound strange. Example (66a), a shortened version of (12), is perfectly acceptable, but the negated version (66b) strikes one as very odd.

-

(66)

-

a.

Eva är nöjd med den slätaste bulle.

‘Eva is satisfied with the plainest bun.’

-

b.

#Eva är inte nöjd med den slätaste bulle.

‘Eva is not satisfied with the plainest bun.’

-

a.

Example (66a) suggests that Eva is very easy to please, but does not suggest that she prefers a plain bun to something more elaborate. Example (66b), in contrast, could only be contextualized under the odd assumption that plainness is a desirable quality, so that the plainer a bun is, the easier it would be to please Eva with it.

The kind of polarity sensitivity that quasi-definites exhibit is quite sensitive to lexical semantics. If we replace slätaste ‘plainest’ with godaste ‘most delicious’, the pattern reverses itself. In this case, it is the version without negation in (67a) which sounds strange, and the negated version in (67b) is the one that sounds acceptable.

-

(67)

-

a.

#Eva är nöjd med den godaste bulle.

‘Eva is satisfied with the most delicious bun.’

-

b.

Eva är inte nöjd med den godaste bulle.

‘Eva isn’t satisfied with the most delicious bun.’

-

a.

Example (67a) would have the very odd implication that the more delicious a bun is, the more difficult it is to please someone with it, as if being delicious were not pleasing. Example (67b) does not have this implication; it sounds as if Eva is picky, but it does not sound as if she would prefer a less delicious bun over a more delicious one. Thus even when it does not impact the acceptability of the sentence, negation changes the underlying assumptions, just as the choice of positive or negative adjectives.

Note also that not all of the quasi-definites that happened to occur in NPI-licensing environments are restricted to such environments in principle. Consider (19a), repeated here as (68a).

-

(68)

-

a.

… sådant som inte kunde iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop.

‘… things that couldn’t be observed even with the strongest telescope.’

-

b.

#… sådant som kunde iakttas med det starkaste teleskop.

‘… things that could be observed with the strongest telescope.’

-

a.

The example without negation, (68b), would be a very strange thing to say. But det starkaste teleskop is not an NPI. It can occur in straightforwardly positive environments; the following constructed example is acceptable:

-

(69)

En vanlig kamera fungerar lika bra som det starkaste teleskop.

‘A regular camera works as well as the strongest telescope.’

If “polarity items are forms or expressions whose interpretation or acceptability depends on the polarity of the contexts in which they occur” (Israel 2011), then quasi-definites are not, as a rule, polarity items, and this quasi-definite in particular is not. So the reason that removing negation in this case makes the sentence unacceptable is not that the phrase is a polarity item. This raises the question: why, then, does removing negation render the example unacceptable?

4.2 Emphasis

The constraints governing the use of quasi-definites fit Krifka’s (1995) characterization of the pragmatics of emphatic prosody, according to which emphasis requires that the assertion is stronger than all of its alternatives. Consider the following example, where capital letters indicate emphasis:

-

(70)

John would distrust Albert SCHWEITzer!

Krifka’s idea is that in order for this to be felicitous, “John would distrust Albert Schweitzer” must be stronger than all alternatives of the form “John would distrust X”. Assume that an assertion is stronger than another if it is the more surprising of the two. Then the felicity conditions on (70) can be satisfied if Albert Schweitzer is more trustworthy than any relevant alternative individual. Krifka’s principle can be spelled out as follows:

-

(71)

Emphatic assertion principle

It is felicitous to assert ϕ emphatically in context c only if it is stronger than all of its expression-alternatives in c.

By ‘expression-alternatives’, we mean alternative ways the speaker could have expressed him- or herself, like the other elements of a Horn scale, if the expression is part of a Horn scale, or Chierchia’s (2006) ‘scalar alternatives’. ‘Strength’ is characterized in terms of what is more or less surprising: A is stronger than B if A is more surprising than B.

Similar conditions have been advocated for the scalar particle even, at least in positive environments (Karttunen and Peters 1979; Rooth 1985; Kay 1990; Wilkinson 1986; Lahiri 1998; Giannakidou 2007; Crnič 2011, i.a.). For example, Even JOHN arrived late suggests that John is the least likely of the relevant individuals to have arrived late. In general, the clause that so-called ‘weak even’ attaches to ought to be the most surprising of its focus alternatives; in other words, that clause must meet the conditions for emphatic assertion à la Krifka.

The same kind of condition has been invoked in order to explain the distribution of minimizing NPIs as in drink a drop, lift a finger and give a damn, in combination with specific assumptions about their alternatives. In his groundbreaking article, Krifka (1995) shows for example that by assuming that a drop is subject to the principle of emphatic assertion, and that its alternatives are other, larger quantities of liquid, it is possible to derive its status as a negative polarity item. Chierchia (2013), building closely on work by Lahiri (1998), implements a similar insight in terms of a silent operator E (for ‘even’), which introduces the presupposition that all of the expression-alternatives are less surprising than the semantic content of the clause to which it attaches. This operator serves to value a feature σ, introduced by inherently emphatic items such as minimizer NPIs. Following a less formal tradition, Israel (2011) proposes to give a unified treatment of all kinds of polarity sensitivity in terms of this kind of scalar reasoning (though see Chierchia 2013, p. 82f. for skepticism as to whether such a model can cover all cases).

The data we have just seen can be understood under the assumption that elative superlatives are inherently emphatic in the same sense: They must be in a clause that meets the conditions for emphatic assertion, with expression-alternatives involving lower degrees. More specifically, the alternatives are identified as follows: Assume that a sentence containing an elative superlative has a meaning of the form “… to the highest degree”. The expression-alternatives are variants of the sentence where the highest degree is replaced by a lower degree. We may call these alternatives degree alternatives for short. For example, the degree alternatives for (66a) above (“Eva är nöjd med den slätaste bulle” ∼ ‘Eva is satisfied with the plainest bun’) are as follows:

-

(72)

Eva is satisfied with a \(d_{1}\)-plain bun

Eva is satisfied with a \(d_{2}\)-plain bun

Eva is satisfied with a \(d_{3}\)-plain bun

…

Eva is satisfied with a \(d_{n}\)-plain bun

where \(d_{1},\ldots d_{n}\) are degrees of plainness. The maximum degree of plainness is the one picked out by the elative superlative expression. The alternative expressions all involve smaller degrees of plainness. What it means for elatives to be inherently emphatic is that the proposition corresponding to the maximum degree must be more surprising than all of the degree alternatives. In other words, there must be an alignment between the degree scale and the scale of likelihood for the degree alternatives.

Note that this requirement very much echoes Fauconnier’s (1975b) ‘scale principle’, according to which a ‘quantifying superlative’ corresponds to the most specific end of an entailment scale, where the scale elements correspond to propositions formed by abstracting over parts of the sentence in question. According to Fauconnier, for a case like (73), the alternative propositions are of the form ‘x bothers y’, for noises x of various strength.Footnote 22

-

(73)

The faintest noise bothers my uncle.

Here we have a ‘quantifying superlative’, as diagnosed by the any-substitution test: The sentence can be paraphrased, Any noise bothers my uncle. It is reasonable to assume that if the faintest noise bothers y, then any fainter noise will bother y. Fauconnier’s observation is that superlatives have a quantifying reading when their surrounding assertion lies at the most specific end of an entailment scale. What we are saying here builds on very similar ingredients, but is slightly different: The claim is that elative superlatives require their surrounding clause to be at the top of the scale of pragmatic strength, and are not licensed unless that is the case.

Note also that in the above formulation we specified that the surrounding clause must meet the conditions for emphatic assertion because the relevant unit for computing whether the condition is met is not always the root clause (and hence not always asserted). The relevant unit can for example be a relative clause, as we see in (13) (‘… things that couldn’t be seen even with the strongest telescope’). Similar observations have been made for negative polarity items, leading Baker (1970, 178) to characterize the situation as follows:

We can think metaphorically of a presentational negative element as giving off paint, which spreads through any structure within the scope of that negative element. The flow of paint can, however, be stopped at any S, so that each S represents a sort of valve which, if shut, stops the flow of paint. However, if a valve is left open, the flow of paint cannot be stopped again except by some lower S.

While a detailed discussion of the locality conditions for licensing elative superlatives would take us beyond the scope of this paper, it is clear that local licensing is to some extent possible, and an implementation of Baker’s (1970) characterization may capture the conditions accurately. Chierchia’s (2013) detailed treatment of intervention and locality for alternative-sensitive pragmatic operators in the grammar is a good candidate for such an implementation.

Let us consider an example to see how this works. Recall the contrast in (66a), repeated here as (74a) and (74b). Uttering (74a) conveys that Eva is easy to please when it comes to baked goods.

-

(74)

-

a.

Eva är nöjd med den slätaste bulle.

‘Eva is satisfied with the plainest bun.’

-

b.

#Eva är inte nöjd med den slätaste bulle.

‘Eva isn’t satisfied with the plainest bun.’

-

a.

What our analysis requires is that (74a) is stronger than all alternatives of the form Eva is satisfied with a bun that is plain to degree d, where d is a degree below the maximum degree. For example, it is required that “Eva is satisfied with the plainest bun” is stronger than “Eva is satisfied with a medium-plain bun” and “Eva is satisfied with a bun that is not at all plain”. This is the case assuming that people are more likely to want fancy cakes than plain buns. Then it is more surprising that Eva can be satisfied with the plainest bun then that she can be satisfied with a less plain bun. We can notate this visually as follows, where the sentence in question is in bold:

(most surprising) | Eva is satisfied with the plainest bun. |

↕ | Eva is satisfied with a medium-plain bun. |

(least surprising) | Eva is satisfied with a non-plain bun. |

In (74b), in contrast, the assertion is the least strong of the degree alternatives, assuming again that plain buns are harder to satisfy people with than fancy buns (or, in other words, that people are less likely to be satisfied with a plain bun than with a non-plain bun).

(most surprising) | Eva isn’t satisfied with a non-plain bun. |

↕ | Eva isn’t satisfied with a medium-plain bun. |

(least surprising) | Eva isn’t satisfied with the plainest bun. |

But of course if we change our assumptions about what kinds of buns are likely to satisfy Eva, then we can make the sentence felicitous. In particular, if we assume that Eva is a very picky eater and prefers plain buns to fancy buns, then it is more surprising that she isn’t satisfied with the plainest bun than that she isn’t satisfied with a less plain bun. This explains why the sentence is felicitous only under changed assumptions about buns.Footnote 23

This analysis also correctly predicts that by changing slätaste ‘plainest’ to godaste ‘most delicious’, we will reverse the pattern of acceptability. Consider the examples below.

-

(75)

-

a.

#Eva är nöjd med den godaste bulle.

‘Eva is satisfied with the most delicious bun.’

-

b.

Eva är inte nöjd med den godaste bulle.

‘Eva isn’t satisfied with the most delicious bun.’

-

a.

Now it is the example without negation, namely (75a), that is unacceptable and the one with it, namely (75b), that is acceptable. This is of course because it is easier to satisfy people with delicious buns than less delicious buns, so not being satisfied with a maximally delicious bun is quite surprising. We can represent this visually as follows. In (75a), the assertion is the weakest of the degree alternatives:

(most surprising) | Eva is satisfied with a non-delicious bun. |

↕ | Eva is satisfied with a medium-delicious bun. |

(least surprising) | Eva is satisfied with the most delicious bun. |

In (75b), the assertion is the strongest of the degree alternatives:

(most surprising) | Eva isn’t satisfied with the most delicious bun. |

↕ | Eva isn’t satisfied with a medium-delicious bun. |

(least surprising) | Eva isn’t satisfied with a non-delicious bun. |

Example (75a) is extremely hard to contextualize, harder than (74b), so in this case the presence or absence of negation affects acceptability more strongly.

For another example, consider the contrast between (19a), repeated here as (76a), and a version of it without negation, (76b).

-

(76)

-

a.

… sådant som inte kunde iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop.

‘… things that couldn’t be observed even with a telescope of maximum strength.’

-

b.

#… sådant som kunde iakttas med det starkaste teleskop.

‘… things that could be observed with a telescope of maximum strength.’

-

a.

That something cannot be seen with a very strong telescope is more surprising than that something cannot be seen with a medium-strong telescope. So there is an alignment between the scale of strength and the scale of surprisal in (76a). In (76b), there is no such alignment. It is not particularly surprising that something can be seen with a very strong telescope. What would be more surprising is if it could be seen with a less strong telescope.

Summarizing an elative superlative requires alignment between a rhetorical scale and a scale over degrees.Footnote 24 An elative superlative always picks out the top-ranked degree, and requires furthermore that the statement formed with this top degree is also at the top of another scale: the scale of suprisal, for the associated propositions. This explains why adding and removing negation can drastically affect the underlying implications or render examples unacceptable.

Assuming that elative superlatives are inherently emphatic also helps to explain why some quasi-definites behave as negative polarity items. In general, when the quasi-definite describes something very small or weak, it is predicted that there will be an affinity for negative (or downward-entailing) environments. Take Han har inte den minsta aning ‘He doesn’t have the slightest idea’, vs. *Han har den minsta aning ‘He has the slightest idea’. With the former variant, the assertion is stronger than all of the alternatives, and this does not hold for the latter. The reasoning involved can be made explicit using analogues of Krifka’s (1995) ‘principle of extremity’ and ‘involvement of parts’, used to explain why NPIs often denote very small entities (a drop of wine, a red cent) or entities with very low values on a scale (lift a finger, bat an eyelash). For example, Krifka’s ‘involvement of parts’ assumption regarding a drop is that if someone drinks something, he or she drinks every part of it. The corresponding assumption for den minsta aning would be that if someone has an idea, he or she has every part of that idea. Krifka’s ‘principle of extremity’ for a drop is that it should always be less probable that someone drank a minimal quantity of liquid than that someone drank a more substantial quantity of liquid. The corresponding principle of extremity for den minsta aning is that it should always be more probable that someone has a tiny idea than that someone has a larger idea. So ‘He has an extremely small idea’ is less surprising than ‘He has a medium-small idea’. And on the other side, ‘He doesn’t have an extremely small idea’ is more surprising than ‘He doesn’t have a medium-small idea’, as required by the requirement that the rhetorical and degree scales are aligned. Together with the assumption that elative superlatives are inherently emphatic, this pattern of assumptions predicts that quasi-definites involving minsta will typically behave as negative polarity items.

For other quasi-definites, the scale of surprisal will typically align with the degree scale so they are felicitous in a positive sentence but not its negation. Many quasi-definites do not show any consistent affinity for one polarity or another. From the perspective we have outlined, it is to be expected that there are many fine shades of gray between quasi-definites that prefer positive environments and those that prefer negative ones. What unites quasi-definites is that they are inherently emphatic. Inherent emphasis, then, is a category that transcends polarity.

In this connection, it is useful to consider Israel’s (2011) simple typology of polarity items, which encompasses two cross-classifying features: emphatic vs. attenuating, and being inherently high on a scale or being inherently low on a scale. Minimizer-NPIs like a whit are emphatic and low on a scale. The NPI much, as in He doesn’t talk much is inherently high on a scale and has an attenuating function. A ton is inherently high on a scale, and inherently emphatic (according to Israel), from which it follows that it is a positive polarity item. PPIs also include items that are inherently low on a scale and attenuating such as somewhat. Quasi-definites can fall into either of the two ‘emphatic’ cells: PPIs with inherently high-on-scale items, or NPIs with inherently low-on-scale items. But they can also lack an inherent placement on a scale, in which case they acquire a preference for positive or negative environments depending on the context in which they appear.

4.3 Entailment down the scale and scope

4.3.1 Mere surprisal suffices

Many of the examples we have discussed have the property that the assertion involving a greater degree entails (or practically implies) variants with strictly smaller degrees. For example, if someone is satisfied with the plainest bun, then, normally, someone is also satisfied with a less plain bun.Footnote 25 This raises the question of whether ‘strength’ ought to be characterized in terms of this sort of entailment, rather than surprisal, as Israel (2011) proposes for polarity items, building on Fauconnier’s (1975a) characterization of the conditions governing ‘quantificational’ readings of superlatives. Fauconnier (1975a) noticed that examples like (77) have a ‘quantificational’ reading (=‘Norm can solve any puzzle’), and that this correlates with a certain kind of entailment.

-

(77)

Norm can solve the hardest puzzle.

As Israel (2011) writes (p. 59), “Very clever people can be confused by things which should be obvious, and very simple problems can sometimes baffle a brilliant mind. Still, an assertion that one can solve the most difficult puzzle normally invites the inference that one can in fact solve any puzzle.” Fauconnier (1975a) calls this kind of entailment ‘pragmatic entailment’, and Israel characterizes it as follows (p. 59): “Pragmatic entailments assume a sort of ceteris paribus condition: they are inferences which do not necessarily hold in all the possible worlds, but just in all the worlds one might reasonably consider on any given occasion. They are thus practically, if not logically, valid.” This looser sort of entailment holds in many of the cases we have seen.

However, there are cases in which this entailment property does not hold, including (64) and (65) above, as well as:

-

(78)

Han har de bästa vitsord.

‘He has the best grades.’

Example (78) does not imply that the protagonist (‘he’) has grades that are less than the best. Parallel observations can be made for (64) and (65). So there is no entailment down the scale in these cases.

This entailment property correlates perfectly with whether the meaning of the sentence can be reinforced by ‘even’-like elements.Footnote 26 In positive environments, even corresponds to either även or till och med (lit. ‘to and with’). We see även in (63), and we can add till och med to for example (11) without a change in meaning:

-

(79)

De vackra färgerna lyser upp till och med den gråaste dag.

‘The beautiful colors light up even the grayest day.’

In negative polarity environments, ‘even’ surfaces as ens in Swedish.Footnote 27 So we can make a parallel observation for (62) by inserting ens:

-

(80)

Levern har inte ens visat den minsta tecken på avstötning.

‘The liver hasn’t even shown the smallest sign of rejection.’

This reinforces the close connection between quasi-definites and the semantics of even-like items. Both require the relevant clause to be stronger than all of its alternatives.

But there is a difference: even is, in addition, additive, carrying a presupposition that one of the alternatives holds (see e.g. Crnič 2011, p. 22f., i.a.).Footnote 28 The additivity presupposition is satisfied in case there is entailment down the degree scale, so even can be used to reinforce the meaning. But when there is no entailment down the degree scale, reinforcement with even is not possible. In the following cases, for example, the entailment property is lacking, and adding till och med ‘even’ sounds odd.

-

(81)

-

a.

Han har de bästa vitsord.

‘He has the best grades.’

↛ He has medium-good grades.

-

b.

#Han har till och med de bästa vitsord.

‘He has even the best grades.’

-

a.

-

(82)

-

a.

Men allt är gjort i det lättaste material.

‘But everything is done in the lightest material.’

↛ Everything is done in medium-light material.

-

b.

#Men allt är gjort i till och med det lättaste material.

‘But everything is done in even the lightest material.’

-

a.

-

(83)

-

a.

Här gömde sig en rätt fylld med det möraste lamm…

‘Here was hidden a dish filled with the most tender lamb…’

↛ Here was hidden a dish filled with medium-tender lamb

-

b.

#Här gömde sig en rätt fylld med till och med det möraste lamm…

‘Here was hidden a dish filled with even the most tender lamb.’

-

a.

These examples are not at all exceptional. The examples in Korp-200 are divided roughly equally among these two classes: cases where there is entailment down the scale and where even can be inserted to reinforce the meaning, and cases which lack both of these properties. We conclude that elative superlatives do not require entailment of the degree alternatives; greater surprisal value suffices.

4.3.2 … but entailment drives scope preferences

The previous section established that entailment down the degree scale does not always hold (i.e. alternatives corresponding to higher degrees do not always entail alternatives corresponding to lower degrees). However, there does appear to be a preference for interpretations on which there is entailment down the degree scale, and this preference results in a preference for certain scopings over others. As mentioned above, quasi-definites tend to take narrow scope, and this tendency is greater than for ordinary indefinites. Recall (53), showing that there is no wide-scope reading for det starkaste teleskop in Stjärnan kunde inte iakttas ens med det starkaste teleskop ‘The star couldn’t be seen even with the strongest telescope’. (Evidence that there was no wide-scope reading came from the awkwardness of subsequent anaphora.) A wide-scope reading would amount to ‘There is a maximally strong telescope that the star cannot be seen with’. The degree alternatives would be of the form ‘There is a telescope of strength d that the star cannot be seen with’, for strengths d below the maximum strength. Not all such alternatives are entailed under this scoping—it is not entailed that for every degree d, there is a (merely) d-strong telescope that the star cannot be seen with. So there is no entailment down the scale on a wide scope reading. On a narrow-scope reading, there is entailment down the scale. If something cannot be seen with a telescope of maximal strength, then it cannot be seen with a less-strong telescope.

If the scope facts are driven by a preference for entailment scales, then it should be possible for a quasi-definite to take wide scope over another scope-bearing element if neither scoping yields an entailment scale. This was seen in example (59) above, repeated here:

-

(84)

Alla rummen var målade i den fulaste färg—en illgrön nyans som påminde om Lisebergskaninerna.

‘All of the rooms were painted in the ugliest color—a sickly green shade that was reminiscent of the Liseberg rabbits.’

Again, this sentence has a wide-scope reading for the quasi-definite, which can be paraphrased, ‘There is an extremely ugly color that all the rooms were painted in’. In this case, the choice of scoping does not bear on whether there is entailment down the degree scale. Even if we took a narrow scope reading (‘For each room, there was an extremely ugly color that it was painted in’), then we would not have entailment down the degree scale (because it would not be implied for each degree d that for each room, there was a color of ugliness d that it was painted in). So the choice is open.

We conclude that the scope possibilities for quasi-definites are limited not by some inherent referential deficiency, but rather by their rhetorical function. With respect to their referential properties, quasi-definites can be seen as being on a par with ordinary indefinites; apparent differences are driven by the pragmatics of emphasis, triggered by the presence of an elative superlative.

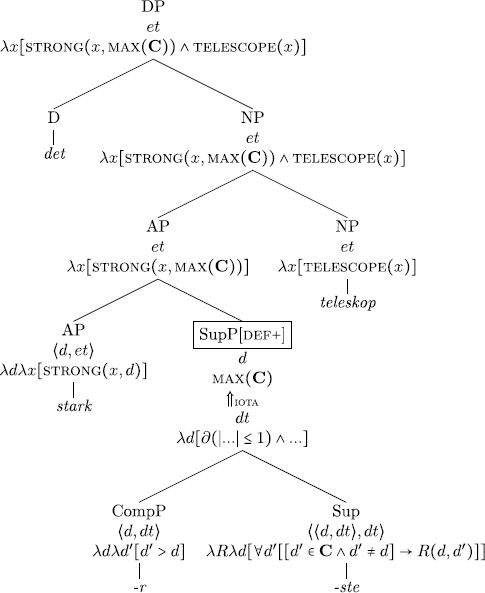

5 Formal proposal

5.1 Semantics

So far, we have established the following facts about quasi-definites:

-

They occur only with superlatives, and in particular only with superlatives on an elative interpretation.

-

They behave like indefinites with respect to their distribution and anaphoric potential.

-

However, they have limited scope options and are sensitive to polarity reversals.

In this section, we develop a formal analysis of the semantics of quasi-definites accounting for the first two observations. In Sect. 5.2 we offer a syntactic analysis from which the semantics can be derived compositionally, but in the current section (Sect. 5.1), we focus on the semantics. (While this analysis is motivated by the pragmatic considerations discussed in the previous section, we will not go any further in making the pragmatics precise.)

We begin with the suffix, and argue for an analysis on which it, like the definite article, marks uniqueness. However, the definite article indicates uniqueness with respect to a property of degrees rather than individuals, and forms a semantic constituent with the superlative. Under this view, the combination of the definite article with the elative superlative affix denotes a degree which is higher than all other (contextually relevant) degrees. An example like det starkaste teleskop will thus end up with the meaning ‘a telescope that is strong to the greatest degree’. This description need not uniquely characterize an individual, and if such uniqueness is not taken for granted in the discourse context, then the suffix is to be left off.

5.1.1 Suffix

Let us begin with the analysis of the suffix. As mentioned above, it has been proposed that the suffix is a marker of ‘specificity’ (Julien 2005, adopted by Alexiadou 2014). One reason to suspect that the definite suffix does encode specificity, as Julien says, involves evidence from minimal pairs as in the following example from Norwegian (Julien 2005, ex. 2.14 p. 36):

-

(85)

-

a.

De uppfører seg som dei verst-e bøll-ar.

‘They behave themsleves like the worst brutes.’

-

b.

De uppfører seg som dei verst-e bøll-a-ne.

‘They behave themselves like the worst brutes- def [and we know who they are].’

-

a.

According to Julien, when the suffix is absent, the noun phrase gets an ‘intensional’ reading, by which Julien means that no specific set of brutes is referred to. When the suffix is present, there is a specific set of brutes, as shown in the English paraphrase. Similar examples are found in Swedish.

A similar contrast emerges with relative clauses. The following two examples are from Dahl (1978) and Delsing (1993, 119) respectively:Footnote 29

-

(86)

-

a.

Student-en [som har kört på den här skrivning-en] är en idiot.

‘The (particular) student [who has failed this exam] is an idiot’

-

b.

Den student [som har kört på den här skrivning-en] är en idiot.

‘Any student [who has failed this exam] is an idiot.’

-

a.

-

(87)

-

a.

% Den sju-år-ig-e pojke-n [som klarar detta] finns inte.

-

b.

Den sju-år-ig-e pojke [som klarar detta] finns inte.

‘The seven-year-old boy [who can do this] does not exist.’

(i.e. There is no such boy.)

-

c.

Den sju-år-ig-e pojke-n [som klarar detta] finns inte längre.

‘The seven-year-old boy [who can do this] does not exist anymore.’

(i.e. He has passed on.)

-

a.

The presence or absence of a suffix in a noun phrase containing a relative clause can thus affect the meaning and/or the acceptability of the sentence (for some speakers). With the suffix, as in (86a), it is felt that a particular student is being referred to, and without the suffix, as in (86b), it is felt that a general statement is being made. The variant of (87) with the suffix, (87a), is felt by some speakers to both presuppose and deny that there is a boy of the relevant kind. Removing the suffix as in (87b) renders the sentence acceptable as a way of denying the existence of such a boy.Footnote 30

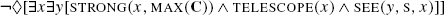

While not purporting to have a complete explanation for these contrasts, we would nevertheless like to convince the reader that the suffix is not a specificity marker. Recall that (87a) was argued to be unacceptable because the predicate finns inte ‘does not exist’ denies the existence of something, and this clashes with the notion that the subject is specific and therefore refers to some individual that the speaker has in mind. It seems quite reasonable indeed to assume that finns inte ‘does not exist’ creates an environment that is hostile to specifics. But if that is so, and if the definite suffix encodes specificity, then why would the definite suffix be not only possible but required in (88)?

-

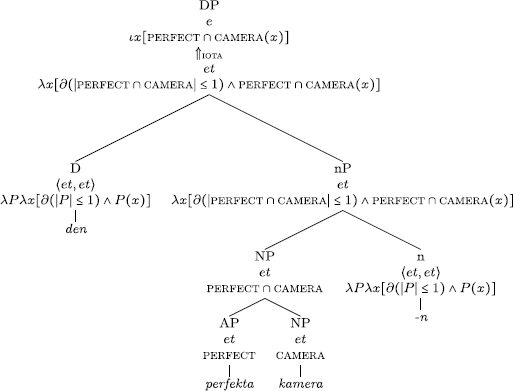

(88)

Den perfekta kamera-n finns inte.

‘The perfect camera- def does not exist.’

A speaker who asserts that the perfect camera does not exist surely does not have an existing camera in mind as the referent for the description. One might want to argue that in some sense den perfekta kameran still does refer to a specific camera. But in that case finns inte is not an environment that is hostile to specifics, and the contrast in (87) does not provide evidence that the suffix encodes specificity. Either finns inte is not hostile to specifics, or the definite suffix does not encode specificity.

Intensional verbs provide evidence for the latter. Consider the following example, where again the definite suffix is not only possible but required.

-

(89)

Varje musiker söker det perfekta instrument-et.

‘Every musician is looking for the perfect instrument- def.’

For every musician, there is a different perfect instrument, and the perfect instrument that the musician seeks may or may not exist, so this noun phrase is not specific in any of Farkas’s (2002) senses. It does not refer to any individual that the speaker has in mind, so it is not epistemically specific; it does not have scope over varje musiker ‘every musician’, so it is not scopally specific; and it is not linked via a partitive relation to a given discourse entity, so it is not partitively specific. Unless there is any other sense in which this noun phrase could be argued to be ‘specific’, we can conclude that it is not specific. And yet it bears the suffix.

Another kind of example in which a suffix occurs on a non-specific noun phrase involves the adjective enda ‘only/sole’ as in ‘the only X’. As Coppock and Beaver (2012) discuss with respect to English, examples like (90) give rise to what they call “anti-uniqueness effects”: For example, in the following case, it is implied that there are multiple sources of calcium in the diet.

-

(90)

Mjölk är inte den enda källa-n till kalcium i kosten.

‘Milk is not the only source- def of calcium in the diet.’

If there are multiple sources of calcium, then there is nothing satisfying the description ‘only source of calcium in the diet’. This means that the existence presupposition that is normally associated with the definite article is absent here. In other words, there is no object to which den enda källan till kalcium ‘the only source of calcium’ refers.

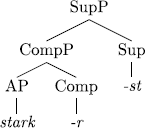

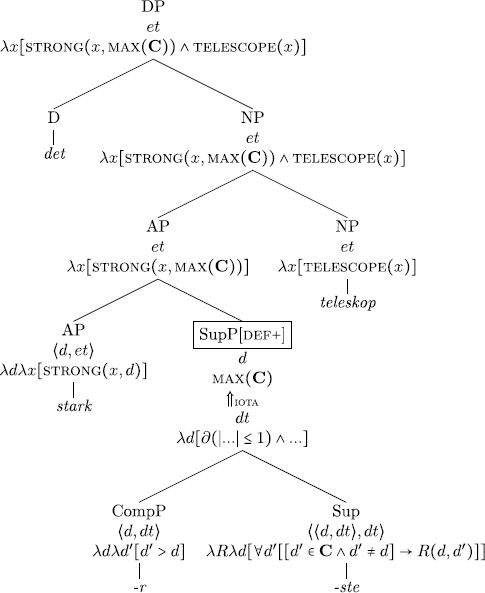

So we conclude that the definite suffix in Swedish is not a marker of specificity, nor does it carry an existence presupposition. According to Coppock and Beaver (2012, 2015), this is true of English the as well, and not unusual for a definiteness-marker. On their view, definiteness-marking encodes a uniqueness presupposition, and existential import for definite, indefinite, and possessive descriptions arises through independent type-shifting operations.