Abstract

This paper proposes an analysis of unagreement, a phenomenon involving an apparent mismatch between a definite third person plural subject and first or second person plural subject agreement observed in various null subject languages (e.g. Spanish, Modern Greek and Bulgarian), but notoriously absent in others (e.g. Italian, European Portuguese). A cross-linguistic correlation between unagreement and the structure of adnominal pronoun constructions suggests that the availability of unagreement depends on whether person and definiteness are hosted by separate heads (in languages like Greek) or bundled on a single head (i.e. pronominal determiners in languages like Italian). Null spell-out of the head hosting person features high in the extended nominal projection of the subject leads to unagreement. The lack of unagreement in languages with pronominal determiners results from the interaction of their syntactic structure with the properties of the vocabulary items realising the head encoding both person and definiteness. The analysis provides a principled explanation for the cross-linguistic distribution of unagreement and suggests a unified framework for deriving unagreement, adnominal pronoun constructions, personal pronouns and pro.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

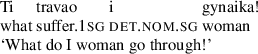

The term agreement implies some form of harmony, or match between the properties of the elements that partake in the agreement relation. A prominent example of the application of the notion of agreement in linguistic theory is subject-verb agreement. In languages that morphologically mark it, the φ-features (person, number, gender) expressed on the verb need to be compatible with those of the subject of the clause. This means that while not necessarily all of the properties person, number and gender are expressed on both the subject and the verb, the relevant markings may not be contradictory. Interestingly, languages occasionally seem to violate this requirement (cf. e.g. Corbett 2006, ch. 5).

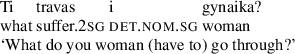

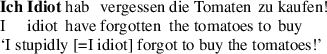

One such apparent agreement mismatch has been described prominently for Spanish under the labels unagreement, subset control, anti-agreement and disagreement (Bosque and Moreno 1984; Hurtado 1985; Suñer 1988; Taraldsen 1995; Torrego 1996; Ordóñez and Treviño 1999; Ordóñez 2000; Saab 2007, 2013; Rivero 2008; Rodrigues 2008; Villa-García 2010; Ackema and Neeleman 2013). Descriptively, unagreement configurations in Spanish involve first or second person plural agreement on the verb, while the apparent subject is a definite plural noun phrase. Since full DPs typically control third person agreement and have the interpretation that no participant of the conversation is partaking in the described event, a common assumption is that las mujeres in (1) is actually third person.

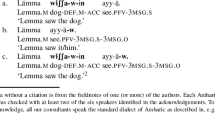

-

(1)

This poses a problem for the common view that φ-features on the verb, represented by agreement morphology, are uninterpretable reflexes of the interpretable φ-features on the subject noun phrase. If las mujeres in the Spanish example is actually a third person plural subject, the origin of the first person plural agreement on the verb remains mysterious.

While most theoretical treatments of unagreement have focused on Spanish, it seems to be anything but an exceptional, language-specific quirk, as a small survey of languages that show unagreement(-like) configurations will show. The main goal of this paper is to propose an analysis of unagreement that can also account for at least part of its cross-linguistic distribution. The empirical focus will be on Modern Greek, and I will point out some differences between the range of unagreement structures in Greek and Spanish.

The basic hypothesis to be defended is that unagreement does not result from a special form or the lack of agreement between subject and verb. Instead, unagreement is the surface effect of zero spell-out of a functional head in the extended nominal projection (xnP) that hosts person features. I argue that its cross-linguistic distribution, at least for languages with overt articles, results from the interaction between variation in the structure of the xnP, particularly of adnominal pronoun constructions, and conditions on the null realisation of D. If person features are hosted on the same head that also encodes definiteness, unagreement cannot arise. On the other hand, unagreement is possible if person is encoded on a separate head.

In this paper I will not be concerned with the gender-mismatch phenomena often observed for Slavic languages (e.g. Corbett 2006, 158). I also distinguish unagreement from Collins and Postal’s (2012) imposters. Imposters involve subjects that behave like third person DPs for agreement and lack any overt first or second person marking, but their denotation—somewhat exceptionally—involves the author or addressee of the utterance. Collins and Postal (2012) characterise this as a mismatch between “notional” and “grammatical” person of a DP. Unagreeing subjects, on the other hand, while also lacking overt first or second person marking, behave as one would expect them to based on their denotation, i.e. they trigger first or second person agreement. To adapt the above terminology, there is then no mismatch between “notional” and “grammatical” person of an unagreeing DP, but at best only between its grammatical and “morphological” person.

Similarly, I am going to leave aside Lichtenberk’s (2000) Inclusory Pronominals. These seem to involve constructions with a non-singular pronoun and a singular nominal expression whose referent is included in the reference of the pronominal. Unagreement, to the extent that it is comparable, works the other way around, i.e. the plural nominal expression forming the subject is interpreted as including the speech act participant indicated by the verbal inflection. So while a comparison of these phenomena might be a fruitful area for future research, for the purpose of this paper I will focus on unagreement alone.

The article is structured as follows. I am going to present an overview of the cross-linguistic distribution of unagreement in the next section, and a more detailed survey of underdiscussed unagreement data from Modern Greek in Sect. 3. Section 4 outlines the theoretical issue raised by the phenomenon for theories of agreement. In Sect. 5, I specify the notion of adnominal pronoun constructions (APCs) and present a cross-linguistic correlation between their structure and the availability of unagreement. Section 6 presents the details of my analysis, as well as some predictions and consequences. Section 7 summarises the results and points out some open questions.

2 The cross-linguistic distribution of unagreement

There has been ample recognition in the literature of unagreement in Spanish, as well as a variety of analyses, cf. Bosque and Moreno (1984), Hurtado (1985), Suñer (1988), Taraldsen (1995), Torrego (1996), Ordóñez (2000), Saab (2007, 2013), Longobardi (2008), Rivero (2008), Rodrigues (2008), Villa-García (2010), Ackema and Neeleman (2013). Instances of unagreement in other languages have received less attention though, and to my knowledge there are very few accounts attempting to explain the cross-linguistic distribution of unagreement. Those previous accounts will be dealt with in Sect. 4 and 6.6 below.

As for further instances of unagreement, Norman (2001) and Osenova (2003) deal with Bulgarian, for Modern Greek the phenomenon is mentioned by Stavrou (1995, 236f., fn. 33) and analysed in more detail by Choi (2013, 2014b).Footnote 1 In the remainder of this section I am going to survey various instances of the unagreement phenomenon to identify factors relevant to its cross-linguistic distribution.

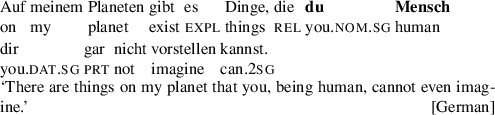

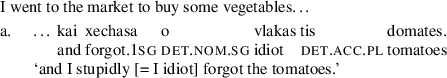

The examples in (1) show five cases of unagreement following the Spanish pattern. The first three are from Romance. Catalan and Galician are found on the Iberian Peninsula, while Aromanian (or Vlach) is a minority language spoken in Greece. Furthermore, I provide an example of unagreement from each of Modern Greek and Bulgarian. Note that although each language allows for both first and second person plural subject agreement marking in these contexts, for reasons of space I will only give one example per language here. Unattributed examples were elicited by the author.

-

(2)

However, unagreement is not restricted to Indo-European languages as the examples in (1) from Swahili (Niger-Congo), Georgian (Kartvelian) and Warlpiri (Pama-Nyungan) show. It may be noticed that in contrast to the previous examples there are no overt definite articles involved here, clearly due to the general lack of definite articles in these languages.

-

(3)

All clear cases of unagreement that I am aware of involve languages with null subjects. As pointed out by a reviewer, French may pose a possible problem for that generalisation. While it is typically not assumed to allow pro-drop, at least some varieties of the language seem to allow constructions such as (1), which are reminiscent of unagreement.

-

(4)

Although I will not attempt to give an account of the French data here, it seems important to point out that a subject clitic, either the first plural nous or the impersonal on replacing nous in colloquial French, is mandatory in these expressions. If these clitics are indeed in subject position, this would suggest that the unagreeing DPs are actually (left-)dislocated, with the clitics representing resumptive pronouns. This would dissimilate these structures from standard unagreement, which is not restricted to left-peripheral “subjects” (see Sect. 3.1). While such an analysis would raise further questions as to the relation between the dislocated phrase and the resumptive pronoun, it should be noted that under the analysis to be proposed here French displays the appropriate nominal structure for unagreement (cf. Sect. 6.1), which could prove important for understanding the French facts above.

Alternatively, French subject clitics could actually represent subject agreement, in line with the proposal that colloquial French has null subjects (Zribri-Hertz 1994; Roberts 2010c; Culbertson 2010). In a similar vein, notice that Kayne (2009) proposes a silent first person plural pronoun NOUS for the analysis of the colloquial first plural use of impersonal on. In the current context, these analyses would suggest that some form of pro-drop is possible in French at least in the environment relevant for the phenomenon in (0), which in this case would indeed represent a form of unagreement.

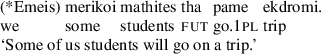

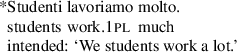

Pending an analysis of the French data, I will tentatively assume that pro-drop is a necessary condition for unagreement (cf. also Choi 2013, 2014b for the same view). Crucially, however, pro-drop is clearly not a sufficient condition for unagreement, as pro-drop languages like Italian, European Portuguese (EP), Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS) and Turkish disallow the prototypical unagreement configuration, as illustrated in (1) and (2).

-

(5)

-

(6)

The presence of a definite article is a hallmark of the classical unagreement configurations in (2). Nevertheless, the existence of articleless languages with unagreement (3) and of languages with a definite article but without unagreement (5) suggests that unagreement is not related to the lack of an overt article per se. The relevance for unagreement of the definite article in those languages that have it will become clearer in Sect. 5, where I will argue that the availability of unagreement correlates with the presence of definiteness marking in adnominal pronoun constructions (APCs).

For the rest of this paper, I will only be concerned with null subject languages showing overt definite articles, i.e. the contrast between the languages in (2) and (5). The question of how the current analysis relates to the languages without articles in (3) will remain open for future research.

3 Unagreement in Modern Greek

For a more detailed view of the phenomenon, this section presents the contexts in which unagreement can be found in Modern Greek. I will also indicate where Greek unagreement behaves differently from what has been reported for Spanish in the literature.

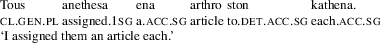

3.1 Definite plural noun phrases

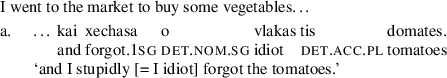

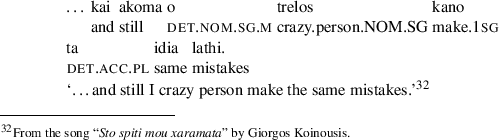

The prototypical unagreement configuration in Greek consists of a nominative definite plural DP and first or second plural agreement on the verb.Footnote 2 As in Spanish, the DP may in principle appear pre- or postverbally, cf. (1) and (2).

-

(7)

-

(8)

Some speakers report a slight degradation with postverbal subjects. This seems to be mainly an information-structural effect due to independent restrictions on VSO orders (Roussou and Tsimpli 2006). In appropriate contexts, postverbal unagreeing subjects are accepted by those speakers as well. Consider a setting in which a group of students and professors occasionally have dinner together. Usually, everybody pays for themselves, but one day one of the professors might utter (1) to a student looking for her or his wallet.Footnote 3

-

(9)

An overt pronoun is optionally possible in unagreement constructions, cf. (1), and its use seems to be emphatic.

-

(10)

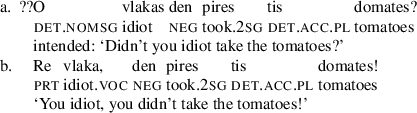

Further, DPs involving demonstratives are clearly disallowed in unagreement configurations, i.e. with first or second person plural agreement, as the contrasts in (1) show.

-

(11)

Finally, pronouns that are co-indexed with an unagreeing subject need to match the person marking on the verb, see (1). The same holds for Spanish (Olarrea 1994; Ordóñez and Treviño 1999, 59).

-

(12)

3.2 Quantifiers

Most Greek quantifiers can appear as unagreeing subjects as shown in (13), rather similar to what has been observed for Spanish.

-

(13)

In contrast to their Spanish counterpart ninguno in (14) however, Greek negative quantifiers (kaneis, kanenas) cannot participate in unagreement relations as shown in (15).Footnote 4 The example in (15-c) seems slightly less degraded to some speakers. Since this type of sentence is nevertheless judged to be unacceptable, this may be a performance effect of the features of the restrictor “spilling over”, somewhat comparable to number attraction effects in English (*The key to the cabinets are on the table), cf. e.g. Bock and Miller (1991) and Wagers et al. (2008).

-

(14)

-

(15)

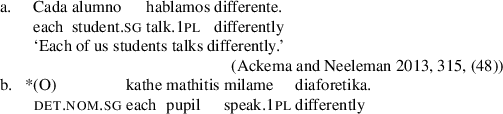

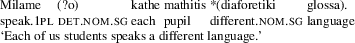

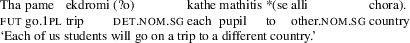

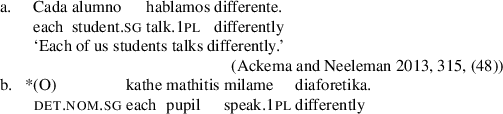

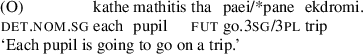

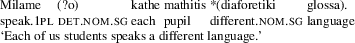

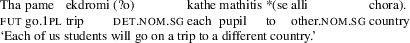

Furthermore, the contrast in (1) shows that the Greek distributive universal quantifier kathe ‘each’ also differs from its Spanish counterpart cada with respect to unagreement, irrespective of the presence of the optional definite article. For present purposes, I assume that Greek kathe does not regularly allow unagreement.Footnote 5

-

(16)

On a cross-linguistic note, it seems that Bulgarian and Aromanian pattern with Greek in ruling out unagreement with negative and (universal) distributive quantifiers. On the other hand, Galician and Catalan seem to behave similar to Spanish in allowing it. However, the relevant cases of unagreement with these quantifiers, while available, seem to be systematically more marked in Catalan than in Spanish (Javier Fernández Sanchez, personal communication).Footnote 6 It remains an open question how the liberality of some Iberian languages as opposed to the restrictivity of the mentioned Balkan languages is explained or whether one of the options is more marked than the other.

To return to the Greek data at hand, the variation in the availability of unagreement with different quantifiers is probably not related to the distinction between weak and strong quantifiers. Kanenas and kaneis, which both share the same accusative form, qualify as weak quantifiers, since they occur in existential constructions like (17).

-

(17)

On the other hand, the other quantifier that is at least restricted with respect to unagreement, universal kathe, is clearly strong, cf. (1). Furthermore, quantifiers like ligoi ‘few’ or polloi ‘many’ qualify as weak quantifiers just like negative kaneis, see (19), while still allowing unagreement.

-

(18)

-

(19)

So while the weak-strong distinction does not seem to be a common denominator of the two types of quantifiers that disallow unagreement (negative quantifiers and distributive universal kathe ‘each’), the way they pattern with respect to “regular” third person agreement distinguishes them from the quantifiers that license unagreement. Both control singular agreement and have a singular restrictor as shown in (20) and (21) respectively. The remaining quantifiers, which allow unagreement, appear with plural restrictors and control plural agreement on the verb in third person readings as exemplified in (22). Since unagreement typically involves plural verbal agreement, the relevant difference between Greek and Spanish in this respect may have to do with the number specifications of the negative and distributive universal quantifiers. While I cannot provide a full account here, I offer some speculations in Sect. 6.2.

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

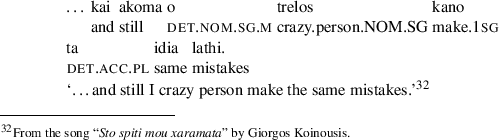

3.3 Object unagreement

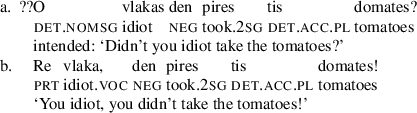

While clitic doubling of direct objects is restricted to certain varieties of Spanish, Greek generally allows clitic doubling of direct and indirect objects (e.g. Anagnostopoulou 2006). A similar mismatch phenomenon as with subject unagreement can also be found between an object and a co-referring clitic.

Example (1) has a second person plural accusative clitic coreferring with the direct object DP, yielding the apparent person mismatch characteristic of unagreement. The word order is VOS with the subject bearing main stress in order to ensure that the object is clitic-doubled rather than just right-dislocated (Anagnostopoulou 2006, 546f.). Notice that it is possible for the direct object to contain an overt second plural pronoun esas in addition to the clitic. This version is more prone to displaying intonational breaks before and after the esas tous protoeteis constituent, but they are by no means obligatory.

-

(23)

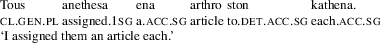

Indirect object doubling displays the same behaviour. Example (24) shows unagreement between the first person plural genitive clitic mas and the genitive object ton foititon. Just as with direct object doubling, the doubled indirect object may—but need not—contain a full pronoun in addition to the doubling clitic.

-

(24)

4 The theoretical challenge of unagreement

In this section, I outline the issues unagreement raises for asymmetric theories of agreement and the types of responses to them in the literature. In contrast to the symmetric view of agreement taken in lexicalist theories like LFG (Bresnan 2001, ch. 8) and HPSG (Müller 2008, ch. 13), where verbal and nominal φ-features are independently generated and their compatibility insured by unification, asymmetric theories of agreement treat subject-agreement morphology on the verb as dependent on, or controlled by, the φ-features of the subject. For concreteness, consider the probe-goal conception of Chomsky (2001, 2004, 2008) where a head acts as a probe by virtue of having an unvalued feature and enters into an Agree relation with the closest element with a corresponding valued feature in its c-command domain. The relevant value of this goal is then transferred onto the probe by a Match operation like (1), following Roberts (2010a, 60, (29)). In subject-verb agreement the valued φ-features of a subject DP are the source for the verbal ones on the unvalued probe T.

-

(25)

Given a well-formed Agree relation of which α and β are the terms (i.e., Probe or Goal) where α’s feature matrix contains [Atti:_] and β’s contains [Atti: val], for some feature Atti, copy val into _ in α’s feature matrix.

Unagreement configurations present a challenge to this view since they seem to involve lexical DPs, by assumption third person, causing verbal first or second person agreement. Irrespective of the exact characterisation of the problem, which depends on the analysis of third person,Footnote 7 this feature mismatch raises serious questions about the viability of asymmetric approaches to agreement.

There are two general approaches to this problem in the literature. One set of analyses treats unagreement as a real lack of agreement and as evidence for the need to revise the agreement mechanism (Ordóñez and Treviño 1999; Ordóñez 2000; Norman 2001; Osenova 2003; Villa-García 2010; Mancini et al. 2011; Ackema and Neeleman 2013). In contrast, a variety of alternative analyses identify the controller or goal of agreement as the key to explaining unagreement—either because the actual agreement controller in unagreement configurations is a silent pronoun rather than the overt “unagreeing” DP (Bosque and Moreno 1984; Hurtado 1985; Popov 1988; Suñer 1988; Torrego 1996; Rodrigues 2008), or because the overt subject DP actually contains the relevant φ-features (Stavrou 1995; Saab 2007, 2013; Choi 2013, 2014b), as I will also argue in Sect. 6. The remainder of this section will briefly discuss the alternative approaches.

4.1 Unagreement is related to the agreement mechanism

The hypothesis that unagreement involves an actual lack of agreement has been adopted by what I will call ALA (actual lack of agreement) accounts. They advocate two sorts of reactions to the presumed lack of agreement: either modification or rejection of asymmetric theories of agreement.

The former approach is represented by Villa-García’s (2010) claim that unagreement and similar effects in the grammar of Spanish show that Chomsky’s (2001) Maximize Matching Effects Condition may be violated in Spanish to the effect that exactly one φ-feature on a probing T may remain syntactically unvalued. This feature is then free to receive a value by other means, e.g. through pragmatics.

On the other hand, several analyses implicitly or explicitly reject the asymmetric view of agreement in favour of a symmetric one, where nominal and verbal φ-features are generated independently from each other,Footnote 8 for example Osenova’s (2003) HPSG-based account of Bulgarian unagreement and Mancini et al.’s (2011) notion of “reverse Agree.” The most detailed argument from unagreement for symmetric agreement is probably made by Ackema and Neeleman (2013).

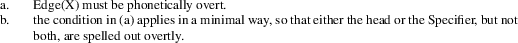

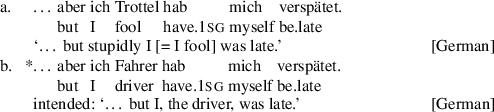

They adopt a grammatical architecture of “mappings between semantics and LF, between LF and PF, and between PF and phonology” (Ackema and Neeleman 2013, 296) with specific well-formedness conditions on mappings and representations. Furthermore, φ-feature are represented by geometries as advocated by Harley and Ritter (2002), meaning that third person is radically underspecified for φ-features (cf. fn. 10 above) and hence less specific than first or second person. Feature hierarchies can be associated in the style of autosegmental phonology with DPs as well as verbs. These associations may be manipulated by syntactic operations. On this basis, Ackema and Neeleman (2013) propose that an operation of φ-feature spreading is responsible for unagreement by associating non-third person features base-generated on the verb with the DP as in (1). This is possible because the DP is assumed to be third person, which in this framework effectively equates to the absence of φ-features. For further details on the proposal the reader is referred to the original paper.

-

(26)

φ-feature spreading (Ackema and Neeleman 2013, 302, (19))

Finally, Ordóñez and Treviño (1999) and Ordóñez (2000) develop the hypothesis that unagreement involves a lack of agreement on the basis of Uriagereka’s (1995) big DP analysis for clitic doubling. They suggest that subject agreement inflexion is a clitic heading a big DP containing the doubled subject. This big DP inherits the φ-features of the clitic and the doubled DP by Spec-head agreement, accounting for the fact that pronouns coindexed with an unagreeing DP have to agree in person with the verbal inflexion (Sect. 3.1). Hence, this view implies that there is no direct Agree relation between the doubled subject and the verb.

This solution seems unattractive since the issue with unagreement is not a general lack of agreement. Some relationship between the subject agreement clitic and the doubled DP is still needed in order to rule out illicit feature mismatches, otherwise it is not clear why a third plural pronominal DP could not combine with first plural subject inflexion or the other way around as in (1) (for this line of argument and comparable Spanish examples cf. Saab 2013, 198f.).

-

(27)

An issue which concerns all ALA accounts is that they have not so far offered a satisfactory explanation for the cross-linguistic distribution of the phenomenon. Although Ackema and Neeleman (2013) suggest that the availability of feature spreading is what sets Spanish apart from Italian in that respect, the explanatory power of that approach seems rather limited. Unless feature spreading is shown to operate elsewhere in the grammar, it is basically a restatement of the fact that Spanish has unagreement and Italian does not.

The matter is further complicated by the observation that languages seem not to be necessarily uniform in their availability of unagreement. Although unagreement is not normally an option in European Portuguese as discussed in Sect. 2 and shown by (28-a), it turns out to be possible in constructions involving cardinal numbers as illustrated in (28-b), due to João Costa (personal communication).

-

(28)

For ALA accounts, this would seem to suggest that EP has some operation like Ackema and Neeleman’s (2013) φ-feature spread or Villa-García’s (2010) pragmatic feature valuation after all, but it is not clear how it could be non-stipulatively restricted to apply only in the appropriate contexts. On the other hand, a structure-based account like the one to be advocated in Sect. 6 can link such language-internal variation to the presence of the definite article in adnominal pronoun constructions with a numeral in EP (Costa and Pereira 2013), see (1).

-

(29)

Moreover, the variation between Spanish and Modern Greek with respect to the availability of unagreement with distributive and negative quantifiers, discussed in Sect. 3.2, is problematic for accounts of this type. With respect to the Spanish data, Ackema and Neeleman (2013) suggest that this possibility is a result of the lack of contrasting plural forms for the quantifiers ninguno ‘nobody’ and cada ‘each’. Their principle of Maximal Encoding (essentially a variant of Kiparsky’s 1973 Elsewhere Condition or Halle’s 1997 Subset Principle) only blocks plural agreement morphology with singular subjects if there is an alternative plural form of the subject. This account runs into problems with the Greek data. Neither kathe ‘each’ nor kaneis ‘nobody’ (nor their variants discussed in Sect. 3.2) have a plural form, so Ackema and Neeleman’s (2013) account predicts the same pattern for Greek and Spanish—contrary to fact. Unagreement is strictly out with kaneis and restricted to very specific distributive contexts with kathe (cf. fn. 8). So while it may be possible to retain Ackema and Neeleman’s intuition that the relevant Spanish quantifiers are underspecified for number, the generalisation “that quantificational unagreement is allowed with plural quantifiers, and with singular quantifiers as long as they do not have a plural counterpart” (Ackema and Neeleman 2013, 317) cannot be quite correct. In addition to the controversial status of paradigms as a primitive of grammar (Bobaljik 2008), lack of a paradigmatic opposition turns out to be also empirically problematic as a predictor for quantificational unagreement in the face of the Greek data.

Finally, it is not clear that non-pronominal DPs necessarily have to be analysed as third person across languages, cf. the discussion in Sect. 4.2.2, although that assumption is crucial for the hypothesis that there is an actual lack of agreement in unagreement which would pose additional requirements on possible theories of agreement. Against this background, I will now turn to proposals that link the phenomenon to properties of the unagreeing DP itself.

4.2 Unagreement is related to properties of the DP

There are several alternative analyses of unagreement that do not view it as a lack of agreement, but explain it in terms of the make-up of the unagreeing DP. They fall into a group of accounts where the overt DPsubj is not in fact the subject, but related to the actual subject and agreement controller, typically pro, by means of either an A-Bar chain (Hurtado 1985; Torrego 1996) or appositionFootnote 9 (Bosque and Moreno 1984; Rodrigues 2008; according to Norman’s 2001 summary also Popov 1988 for Bulgarian), and a group that argues that the subject DP itself contains the φ-features expressed in the verbal agreement morphology—the “hidden feature” perspective in Ackema and Neeleman’s (2013) terminology.

4.2.1 DPsubj is not the agreement controller

One way of analysing unagreement is to assume that the overt DP in unagreement configurations is left dislocated and forms an A-Bar chain with the silent pronominal subject of the clause. Sentence initial full DP subjects in null-subject languages have indeed been argued to be left dislocated (e.g. Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998; Ordóñez and Treviño 1999). The fact that unagreement is not restricted to sentence initial subjects, however, is problematic for an account relying on left-dislocation and I refer to Ackema and Neeleman (2013, 311–313) for further discussion.

The appositive analysis, on the other hand, capitalises on the optionality of an overt pronoun in the core unagreement cases, cf. e.g. (1) repeated from (10) above, and holds that unagreement involves the same structure with pro in place of an overt pronoun. Crucially, this relies on an appositive analysis of we linguists-type adnominal pronoun constructions (Cardinaletti 1994), which I will argue against in Sect. 5 where I will also propose a modified version of the pronominal determiner analysis (Postal 1969) instead.

-

(30)

4.2.2 Hidden features

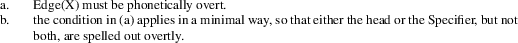

According to the hidden-feature view, which I am defending in this paper, the impression of a mismatch arises because the relevant non-third person features are not overtly expressed on the agreement controlling DP. This type of account is explicitly rejected by Norman (2001) and Ackema and Neeleman (2013, 310f.). The latter raise the four points of criticism in (1). I will briefly address them here with the exception of (31-d), which will be the subject of Sect. 6.

-

(31)

The first issue concerns an ERP experiment on Spanish by Mancini et al. (2011) that showed a three-way distinction in the processing of items with an agreement mismatch, regular agreement and unagreement. Ackema and Neeleman (2013) follow them in interpreting this as indication of a “reverse agreement” mechanism. Considering that Mancini et al.’s (2011) experimental material only contained preverbal subjects though, their results can at least as plausibly be interpreted as an issue of performance as of competence grammar (cf. in particular Neeleman and van de Koot 2010). Since the subject xnP is parsed before the verbal inflection and lacks overt person marking, assigning it third person by default is a plausible parsing strategy. Upon encountering the verbal inflection the parser will be forced to amend the structure (and interpretation) of the subject xnP, while in “regular” agreement no such recovery mechanism is required, accounting for the difference in behaviour between both types of agreement. Importantly, the default nature of third person is a property of the parser on this interpretation, not of all non-pronominal DPs.

Regarding (31-b) notice that, in contrast to gender and number, person is a discourse-related property, dependent on the role of the denoted entity with respect to the speech act (cf. e.g. Heim 2008). An R-expression with inherent person features would denote an entity that is inherently speaker, addressee or non-participant in any speech context. Maybe Portuguese a gente ‘the people’ in its first person plural use (Costa and Pereira 2013) could be viewed as such a case, but the scarcity of the phenomenon does not seem very surprising.

Finally, contrary to Ackema and Neeleman’s claim in (31-c), overt person marking on DPs is actually attested. Lyons (1999, 143) gives the examples in (32) for person marked DPs in Khoekhoe/Nama (Khoesan). For more details compare also Haacke (1976).

-

(32)

saá kxòe-ts

(you person-2SG+M)

‘*you man’

tii kxòe-ta

(I person-1SG+M)

‘*I man’

saá kxòe-ts

(you person-2SG+M)

‘*you man’

kxòe-p

(person-3SG+M)

‘the man’

sií kxòe-ke

(we person-1PL+M)

‘we men’

saá kxòe-kò

(you person-2PL+M)

‘you men’

kxòe-ku

(person-3PL+M)

‘the men’

Rust (1965, 18) explicitly relates them to adnominal pronoun constructions, which I discuss in the next section:

Das Substantiv wird auch mit den Suffixen der 1. und 2. Person verbunden. […] Wir haben ja auch im Deutschen solche Verbindungen wie ‘ich Mann’, ‘du Mann’, ‘wir Hirten’ u.s.w.

(The noun can also be connected with the suffixes of first and second person. […] We have similar expressions in German like “I man”, “you man”, “we shepherds” etc.)

Moreover, similar markers seem to be attested in Alamblak (East Sepik; cf. Bruce 1984, 96f.), and the so-called proximate plural in Basque (Hualde and Ortiz de Urbina 2003, 122; Areta 2009, 67) may also be related to a comparable category. In conclusion, the criticism directed at the hidden feature account does not seem to be sufficient to dismiss it.

The main difference between the hidden feature proposals in the literature is where the person features of the unagreeing subject are located: on the same head as the definite article (Saab 2007, 2013), on a head distinct from it (Stavrou 1995; the present account), or on a phrasal constituent in SpecDP (Choi 2013, 2014b).

Saab’s (2007, 2013) analysis builds on the classical pronominal determiner account (cf. Postal 1969 and next section). In contrast to English, Spanish simply does not realise the D head with its person features by a pronominal. However, this account does not address the cross-linguistic distribution of unagreement nor the problem that the pronominal determiner analysis does not transfer to the analysis of Spanish adnominal pronoun constructions (cf. Sect. 5.3).

Choi (2013, 2014b), on the other hand, rejects the pronominal determiner analysis and locates person features in a separate, silent pronominal DP in the specifier of an unagreeing DP. The differences from the present account are discussed in more detail in Sect. 6.6.

Finally, the analysis sketched briefly by Stavrou (1995, 236f., fn. 33) suggests that the structure of the unagreeing subject in (1) is something like (2).

-

(33)

-

(34)

[DP [D pro ] [DEFP [DEF oi ] [NP kalitechnes ] ] ]

Although she does not detail her assumptions about the nature of pro, this sketch clearly locates person and definiteness features on separate functional heads in the same xnP and thereby represents a direct predecessor of the line of thought to be further developed in Sect. 6. In preparation for that, the next section discusses structural variation in adnominal pronoun constructions.

5 Adnominal pronoun constructions (APCs)

In this section, I present a cross-linguistic generalisation regarding the expression of adnominal pronoun constructions (APCs) and the availability of unagreement and argue for a distinction between two types of APCs. After summarising the main arguments for a pronominal determiner analysis (in the sense of Postal 1969 and Abney 1987) of one type of APCs in Sect. 5.2, I argue for a modified version of that analysis for the other relevant type of APC in Sect. 5.3. This second type of APC will play an important role in the analysis of unagreement to be proposed in Sect. 6.

The term APC is used here as a cover term for referring expressions involving at least a pronoun and a noun, sometimes also described as pronoun-noun collocations or constructions.Footnote 10 Crucially, I limit this term to expressions that involve a single extended nominal projection (xnP), that is, excluding various kinds of “apposition” as will become clear later in this section.

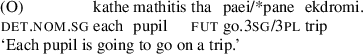

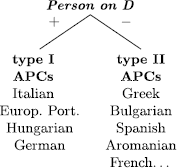

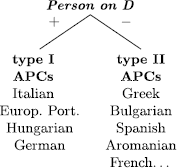

5.1 A cross-linguistic generalisation

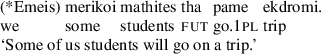

Restricting attention to languages with overt articles as indicated in Sect. 2, the following two patterns emerge from our small sample. In the null subject languages without unagreement discussed in Sect. 2 APCs exclude the definite article. I will call these type I APCs.

-

(35)

Languages without unagreement

noi

(*gli)

studenti

[Italian]

nós

(*os)

estudantes

[European Portuguese]

mi

(*a)

diákok

[Hungarian]

we

det. pl

students

The null subject languages showing unagreement, on the other hand, require a definite article in APCs. I will refer to these as type II APCs.

-

(36)

From these observations emerges a tentative generalisation of the following form:Footnote 11

-

(37)

In the remainder of this section I will discuss the syntactic structures of both types of APCs, before presenting an analysis of unagreement drawing on this generalisation in Sect. 6.

5.2 Type I APCs and the pronominal determiner analysis

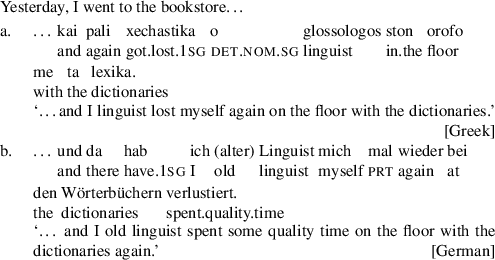

Most previous research on APCs has focused on type I APCs, which exclude a definite article as illustrated in (35) above and additionally for German and English below.Footnote 12

-

(38)

wir Studenten [German]

we students

Postal’s (1969) classical “pronominal determiner” analysis treats the pronoun in these APCs as an instance of the definite article. This analysis, illustrated in (39), has since been argued for by Pesetsky (1978), Abney (1987), Lawrenz (1993), Lyons (1999), Déchaine and Wiltschko (2002), Panagiotidis (2002), Rauh (2003) and Roehrs (2005). A competing analysis, sketched in (40), takes the lexical noun to be an apposition to the pronoun. Variants of this “appositional” analysis have been assumed by Delorme and Dougherty (1972), Olsen (1991), Cardinaletti (1994), Ackema and Neeleman (2013), and all appositional analyses of unagreement that I am aware of (cf. Sect. 4.2.1).

-

(39)

-

(40)

In order to substantiate the decision to adopt the pronominal determiner analysis here, this section summarises several of the arguments from the literature showing that APCs differ from appositions in various ways. I will start by discussing a series of differences between APCs and “loose” apposition, which seems to be the option most widely considered in the literature, before going on to provide some reasons to distinguish APCs from “close” appositions as well (for the distinction between two types of apposition cf. Burton-Roberts 1975 and Stavrou 1995).

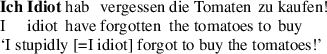

5.2.1 Differences between type I APCs and loose apposition

One difference between APCs and appositional constructions can be observed in the behaviour of pronominal objects of particle verbs, which generally have to precede the particle, cf. (1) after Pesetsky (1978, (15)). Pesetsky’s (1978) example (16), reproduced here in (42), shows that the same holds when the pronoun is accompanied by an apposition or a relative clause (a-c), but crucially not for the APC in (d), which behaves like a “regular” full DP in being able to follow the particle.

-

(41)

-

(42)

Moreover, the variation in case marking of the pronoun mentioned in fn. 16 is restricted to APCs and not attested in appositional constructions, as shown in the following examples from Pesetsky (1978, 355, (17)).

-

(43)

A further point raised by Pesetsky (1978, 354, (12)) exploits a scope variability of appositions which is lacking in APCs. The some of… others of… construction relates two complementary subsets of a set, and requires the restrictors of both quantifiers to be identical. The example in (44-a) is felicitous because the restrictor of both quantifiers is the same group containing the speaker, while the appositions attach high, at the quantifier level, giving a salient property for each of the two subsets determined by the construction. The resulting reading is that of a ‘we’ group consisting of (at least) linguists and philosophers, with members of the former subgroup thinking that members of the latter are crazy. The APCs in (44-b), on the other hand, do not allow that option. The nouns have to scope low, leading to two non-identical restrictors—a group of philosophers and another one of linguists—accounting for the lack of a coherent interpretation.

-

(44)

Lawrenz (1993, ch. 6) produces several further arguments in favour of a pronominal determiner analysis. While her discussion is focused on German, most of her arguments can be easily transferred to English examples.

-

(1)

Reinforcers like here or there are allowed in the context of the definite article or of an adnominal pronoun, but they are ruled out in appositions consisting of an articleless, indefinite noun phrase:

they, the girls there and we girls here vs. *they, ∅ girls there or *we, ∅ girls here

-

(2)

The article obligatorily accompanying certain proper names may be replaced by an adnominal pronoun, but must not be dropped in cases of apposition:

The/you Wright brothers are brilliant vs. *∅ Wright brothers are brilliant and they, *(the) Wright brothers, …

-

(3)

Certain adverbials that are licensed in appositions are out in the context of the definite article as well as with adnominal pronouns:

the/you (*formerly) admirers of modern art… vs. you, formerly admirers of modern art, …

-

(4)

Restrictive post-nominal modifiers are obligatorily located after the complete pronoun-noun complex of an APC, while they can intervene between a pronoun and an apposition, presumably because the apposition scopes over the pronoun + modifier expression (cf. Pesetsky’s 1978 argument from the some of…, others of … construction):

you rich boys with your fancy dresses vs. *you with your fancy dresses rich boys; cf. you with your fancy dresses, rich boys, …

-

(5)

APC are available in right-dislocated contexts where “loose apposition” constructions would be infelicitous:

Back then we had dreams, we simple folks vs. %Back then we had dreams, we, simple folks

-

(6)

APCs lack a comma intonation. An expression in construction with a pronoun requires the comma intonation indicative of appositions if there is a morphosyntactic number mismatch:

*we father and son… vs. we, father and son, …; but: we fathers and sons

Furthermore, the pronominal determiner analysis also seems to be in a better position to explain why APCs are incompatible with indefinite expressions, cf. the contrast in (45) where only an appositional structure, marked by a clear comma intonation and optionally accompanied by that is, licenses the phrase in (45-a).

-

(45)

5.2.2 Differences between type I APCs and close apposition

The above diagnostics focus on the distinction between APCs and “loose” apposition. Let me now turn to so-called “close” apposition as in the poet Burns, which, in fact, seems to pattern with APCs in some respects—e.g. the final three diagnostics quoted from Lawrenz (1993) or the definiteness restriction of (0).

Nevertheless, there are good reasons to distinguish APCs from close apposition. Burton-Roberts (1975, 397) notes that close apposition has to involve a proper name (in fact, his analysis treats the first noun as a modifier of the proper name, parallel to the ingenious Chomsky). APCs, on the other hand, are not restricted in this way.

Even if one were to claim that the pronominal part of APCs fulfilled the role of a proper noun for the purpose of that restriction, one would inevitably run into a further problem. While the pronominal element in APCs invariably comes first, the proper name comes last in the unmarked form of close apposition. While the latter allows an inverted variant with some form of contrastive interpretation (Burns the poet; cf. Burton-Roberts 1975, 402), APCs arguably only allow one order (*linguists you).

Finally, Roehrs (2005) notes that adjectival modifiers cannot intervene between the first and the second noun in close appositions, cf. (1). On the other hand, in APCs they need to interfere in the pronoun-noun complex, as illustrated in (2).

-

(46)

-

(47)

5.2.3 The structure of type I APCs

I conclude that type I APCs, those lacking an overt definite article, are properly analysed as pronominal determiners. I assume that they parallel the structure of simple (strong) pronouns in that in both cases D bears definiteness and person features, which are eventually spelled out as a pronoun.Footnote 13 Following the analysis of pronouns in (1) proposed by Panagiotidis (2002, 2003), the crucial difference is that in simple pronouns a silent empty noun, eN, forms the core of the xnP instead of the full noun found in APCs (cf. also Elbourne 2005). The functional head Num is assumed to host number features (Ritter 1995).

-

(48)

5.3 Extending the pronominal determiner analysis to type II APCs

The pronominal determiner analysis does not carry over directly to the type II APCs found in unagreement languages (Greek, Spanish etc.), since these require the presence of the definite article instead of the complementary distribution between article and pronoun characteristic for type I APCs (cf. Sect. 5.1).Footnote 14 So considering that several of the arguments listed above for a pronominal determiner analysis of type I APCs build on the lack of an overt definite article, an appositional analysis might seem more promising for type II APCs.

In this section, I argue that, just like type I APCs, type II APCs should nevertheless be distinguished from loose and close apposition. However, I am not going to take the co-occurrence of the definite article and the pronoun in type II APCs as an argument against the pronominal determiner analysis per se. Instead, I propose an extension of that analysis, which retains the view that the adnominal pronoun is part of the same extended nominal projection as the noun, but places person features on a separate functional head higher than D in type II APCs, rather than on D itself as in type I.

5.3.1 Differences between APCs and loose apposition in Greek

This section establishes the distinction between close and loose apposition in Greek and presents arguments against treating type II APCs as cases of loose apposition.

Stavrou (1995) presents a series of reasons to distinguish between two types of apposition also in Modern Greek, illustrated by string-equivalent sequences like o aetos to pouli ‘the eagle (which is) a bird’ and o aetos, to pouli ‘the eagle, the bird’ (cf. also Stavrou 1990–1991, Lekakou and Szendrői 2012 and references cited there).Footnote 15 The differences she discusses include, among others, different intonational patterns (i.e. comma intonation in loose apposition), the restrictions of discourse markers like diladi ‘namely’ to loose apposition and the fact that only loose appositions may involve an indefinite DP (cf. also the discussion of (54) below):

-

(49)

The distinction between the two constructions is also evident in the contrast between the close apposition in (50-a) and the structure involving loose apposition in (50-b), based on Stavrou (1995, 221). She observes that in loose apposition “the first definite noun phrase […] itself denotes a specific referent already established in the linguistic context or uniquely retrievable from the situation of discourse” (Stavrou 1995, 221). Accordingly, (50-b) is deviant because it is tantamount to saying ??Den eida to Gianni, alla to Gianni ‘I didn’t meet John, but John.’

-

(50)

APCs, on the other hand, pattern with close apposition in this respect as shown by the contrast of the APCs in (51-a) with the string-equivalent loose appositions in (51-b).

-

(51)

Further, Pesetsky’s (1978) argument from the wider scope options of loose apposition, discussed for type I APCs in Sect. 5.2.1, can be adapted to type II APCs. In addition, Greek allows for a more fine-grained manipulation of the attachment site of the apposition, since appositions match the case of the element they characterise. In (52-a), the loose apposition—marked prosodically and detectable by the availability of diladi ‘that is’—matches the case of the pronoun, yielding a contradictory low attachment interpretation where “us” is simultaneously exhaustively characterised as consisting of “the linguists” and “the physicists”. In contrast, when the apposition case-matches the whole quantifier phrase as in (52-b), the resulting high attachment interpretation is fine like in Pesetsky’s (1978) English example in (44-a). Notice that, while only the second sentence is felicitous, both attachment possibilities are grammatical for loose appositions.

-

(52)

APCs also yield an infelicitous low attachment reading under case matching between the pronominal and the following DP, cf. (53-a). Crucially, however, the high attachment configuration involving case matching with the quantifier is not even grammatical as illustrated in (53-b). This represents a further clear contrast between loose apposition and APCs.

-

(53)

Finally, the definiteness effect observed above in (45) for type I APCs holds for type II as well. An indefinite phrase can be attached to a pronoun as a loose apposition in (54-a), but cannot appear in an APC as shown in (54-b).

-

(54)

This all strongly suggests that type II APCs must be distinguished from loose apposition, and in several respects behave rather similarly to close apposition. However, in spite of the similarity in terms of the tight structural coherence displayed by these two constructions, there are reasons not to view type II APCs as simply a special form of close apposition either, as I will discuss next.

5.3.2 Differences between APCs and close apposition in Greek

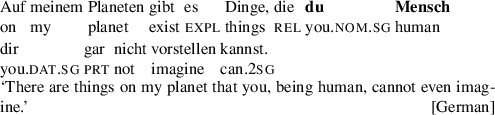

Lekakou and Szendrői (2007, 2012) observe that close apposition involves a symmetric relationship between two nominal phrases, so that “neither subpart of a close apposition is the unique head of the construction” (Lekakou and Szendrői 2012, 114; cf. also Roehrs 2005 for a different implementation of that insight), and note an important contrast with APCs in that respect. Consider the examples from Lekakou and Szendrői (2012, 114, (12); transliteration adapted) given in (55). While a predicative adjective can agree in gender with either component of the appositive irrespective of their linear order, the APC in (55-c) exclusively triggers first plural agreement on the verb. If the APC consisted of a close apposition of two DPs, first plural emeis and third plural oi glossologoi, we would instead expect a similar alternation in agreement possibilities for person as in the other two examples for gender.

-

(55)

Another effect highlighting the asymmetry between the pronominal and the “full” nominal part of APCs is that only one linear order is possible, i.e. the pronominal must be phrase-initial as shown in (1).

-

(56)

I follow Lekakou and Szendrői’s conclusion that APCs are not close appositions and that “arguably the pronominal part is the unique head” (Lekakou and Szendrői 2012, 114) in Greek APCs.

5.3.3 The structure of type II APCs

Remember that type II APCs require the presence of the definite article in addition to the pronoun, and that the pronoun strictly precedes the noun and the article, see the examples in (1).

-

(57)

Building on the aforementioned proposal by Stavrou (1995, 236f., fn. 33) for Greek, I suggest a modification of the pronominal determiner analysis for type II APCs. While both types of APC consist of one xnP, in type II person is encoded in a functional head distinct from the one hosting the definite article. Departing from Stavrou, I assume that the definite article is located in D, while (interpretable) person features are hosted by a higher functional head Pers as illustrated in (1). Like D, Pers agrees with the Num head for number.

-

(58)

The central idea is that APCs do not arise from combining a third person DP oi foitites ‘the students’ with a pronominal DP like emeis ‘we’, i.e. two separate xnP constructions. Instead, the pronoun simply spells out the person features of the one xnP, just like in type I APCs. The crucial difference is that in type I definiteness and person are encoded on the same head, whereas in type II person is encoded on a separate functional head higher than D. The following section shows how this view of APCs helps to shed light on the analysis of unagreement.

6 Nominal structure and unagreement

In this section, I develop a hidden feature analysis of unagreement that relates the cross-linguistic variation of unagreement to the variation in the structure of APCs discussed in the previous section. The analysis adopts the framework of Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993; Harley and Noyer 1999; Embick 2010), in particular the late insertion hypothesis: functional heads contain no phonological matrix until after spell-out, when vocabulary insertion takes place.

I argue that unagreement arises from type II APCs whose Pers head receives null spell-out and discuss some predictions of this analysis. The restrictions against unagreement in languages with type I APCs are related to the interaction of their structure and spell-out restrictions of the D head. On this basis, I finish by sketching a null-spell-out account of so-called pro in NSLs of both types. As a consequence, pro is analysed as internally complex just like overt pronouns.

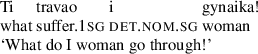

6.1 Deriving unagreement from type II APCs

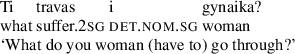

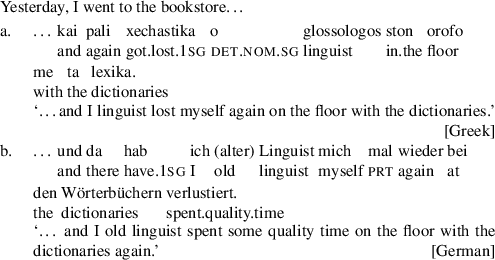

The essence of a hidden feature analysis of unagreement is that the apparently unagreeing subject DP actually carries the φ-features reflected by the verbal agreement morphology, thereby resembling the analyses of APCs proposed in Sect. 5. For further support of this parallel consider (1). In an afterthought or self-correction context, an appositive first plural pronoun may clarify that the author of the utterance is a member of the group denoted by the subject.

-

(59)

In contrast, in both the APC in (1) and the unagreement construction in (2) such an apposition is infelicitous. This is easily explained if the subject DP already encodes the author’s membership in its denotation in both cases, making the apposition redundant.

-

(60)

-

(61)

Moreover, in accordance with the number asymmetry cross-linguistically observed for APCs, unagreement seems to be most readily available in the plural. Spanish, for instance, rules out singular unagreement altogether, with regular nouns (1) as well as epithets (2).

-

(62)

-

(63)

Greek also shows a general preference for plural unagreement, although it also seems to have some cases of singular unagreement. These and potential parallels to German singular APCs are discussed in the Appendix.

In Sect. 2 I have identified pro-drop as a necessary condition for unagreement. It seems a reasonable hypothesis, then, that unagreement relates to APCs like a “dropped” pronoun relates to an overt one. In the present analysis that means that the functional head encoding person features in APCs is not spelled out in unagreement. But what determines this difference between APCs and unagreement? I will suggest here that demonstrativity—or deicticity—plays a central role.

In null subject languages, the use of overt pronouns is typically associated with emphasis. The same appears to hold for the use of APC constructions over unagreement. Consider, for example, a comment by de Bruyne (1995, 145) on cases of unagreement in Spanish noting that “the use of the subject pronouns [i.e., an APC; author] would have an emphatic effect.” Demonstratives present one way of indicating emphasis.

In this context it is worth pointing out an observation by Sommerstein (1972, 204) regarding example (1) from Postal (1969, 219), probably with stress on you. Arguably, this can only be reported using a demonstrative as in (2), but not with a plain definite article as in (66).

-

(64)

You troops will embark but the other troops will remain.

-

(65)

He said that those troops would embark but the other troops would remain.

-

(66)

*He said that the troops would embark but the other troops would remain.

This suggests that English “pronominal determiners” can actually correspond to demonstratives and not only definite articles. On this basis, Rauh (2003, 415–418) proposes that stressed pronominal determiners in German and English carry a [demonstrative] feature, while unstressed ones, which pattern with definite articles, lack this property.

Now consider the Greek example in (1) where some out of a larger group of pupils are sent on a tour, while the complement set are told that they can leave. In this context, the use of the adnominal pronoun is obligatory in order to establish a complement set of pupils. Notice that the second occurrence of mathites ‘pupils’ is preferably elided, but is included here to stress that the relevant interpretation is one where the group of ‘others’ consists of other pupils (rather than of non-pupils, in which case the adnominal pronoun would be optional). In parallel to the English example above, reporting this utterance also requires the use of a demonstrative, see (2).

-

(67)

-

(68)

Against this background, I propose that unagreement corresponds to the version with an unstressed pronoun in lacking a demonstrativity feature, and the type II APC to the stressed counterpart by virtue of being demonstrative.

There are two further principal pieces of evidence in favour of the view that adnominal pronouns and demonstratives form a class. First, demonstratives are in complementary distribution with adnominal pronouns. This holds for type I APCs like English *these we/us linguists as well as for Greek or Spanish type II APCs:

-

(69)

-

(70)

Second, APCs and DPs containing a demonstrative each enforce a different, specific verbal agreement corresponding to their feature specification, i.e. they both block unagreement as illustrated for Greek in (1).

-

(71)

These observations suggest that deictic demonstratives are simply the third person variant of adnominal pronouns, and therefore realise the same head Pers,Footnote 16 as illustrated in (1). For concreteness, I assume here that demonstrativity is represented by a binary feature [±dem] on Pers and will make crucial use of both feature values. It remains for future work to determine whether treating the feature as privative would be preferrable. The notation [uF=Val] is used for convenience in order to indicate the initially unvalued, i.e. probing, features modeling xnP internal agreement. It is not intended as a commitment to a distinction between interpretable and uninterpretable unvalued features.

-

(72)

The Pers and D heads agree for number and gender with the relevant interpretable features inside the xnP. The vocabulary item (VI) corresponding to a [−dem] Pers head is null in NSLsFootnote 17 and underspecified for any φ-features, while a [+dem] specification leads to insertion of the specified forms as sketched in (1). Notice that the null spell-out of Pers is an independent point of variation, so there can be non-NSLs with the structure in (0), French maybe being a case in point (nous les etudiants ‘we students’; cf. also the brief discussion in Sect. 2).

-

(73)

Pers[−dem] ↔ ∅

Pers[+auth,+part,pl,+dem] ↔ emeis

Pers[−auth,−part,pl,masc,+dem] ↔ aftoi

This accounts for the lack of unagreement with APCs and demonstratives insofar as they are the [+dem] counterparts to otherwise syntactically identical unagreeing noun phrases.

Furthermore, the proposal predicts that unagreement is not a feature of a language per se, but results from the spell-out possibilities facilitated by the structural configuration of type II APCs. If a null subject language expresses definiteness and person separately in some cases only, those cases should allow unagreement. This is borne out as discussed in Sect. 4.1 for European Portuguese, which exceptionally shows unagreement effects with numerals. In the current account, this is expected since numerals give rise to a type II pattern in APCs.

Before I go on to discuss the absence of unagreement in languages like Italian, the following two subsections will deal with two further predictions of the proposed account. The first one concerns quantificational unagreement and the second one the fact that if unagreement is traced to properties of the nominal domain, it should be detectable in other instances of verbal agreement such as object agreement or clitic doubling.

6.2 Quantificational unagreement and [−dem]

The fact that quantificational unagreement configurations (Sect. 3.2) do not have counterparts with overt pronouns seems to undermine the correlation between APCs and unagreement. Ackema and Neeleman (2013) identify this as a problem for appositional and hidden feature accounts of unagreement, which are built on this correlation. The present account, however, actually predicts this pattern.

The quantificational unagreement configuration in (1) is ungrammatical with an overt pronoun, but well-formed in its absence. The verbal inflexion is for first person plural in accordance with the interpretation of the sentence. Under present assumptions this indicates that the subject actually contains the relevant person features.

-

(74)

Let us assume that [±dem] is indeed connected to demonstrativity as suggested in Sect. 6.1 with reference to Rauh’s (2003) [demonstrative] feature. It seems plausible that definite reference is a precondition for demonstrativity/deicticity and that quantified phrases as in (0) do not involve definite reference.Footnote 18 Consequently, they cannot sustain a [+dem] feature either, cf. (1). Since only [+dem] Pers receives overt spell-out, overt pronouns are consequently ruled out in this configuration.Footnote 19

-

(75)

Numerals of the type emeis oi dyo foitites ‘we the two students’, where Pers can receive an overt spell-out, do not constitute an exception, but rather underline the role definiteness plays in this context. They obviously involve a “real” definite DP, denoting a specific set of people. The numeral simply indicates its cardinality. This contrasts with properly quantifying numerals, which do not involve an article and cannot sustain overt Pers: *emeis dyo foitites ‘we two students’. The difference in the semantics of these phrases is illustrated by the contrast between (76-a) and (76-b).

-

(76)

Both sentences are fine with third person agreement in the second clause, but their status differs when there is first person unagreement in the second clause. Most of my consultants accept the first sentence with first plural agreement on both verbs as a felicitous utterance in a situation where 5 out of a group of pupils will go to the theatre and the rest, including the speaker, will go to the movies.Footnote 20 The corresponding sentence in (76-b), with the numeral in the scope of the article, is incoherent for all speakers.

This is explained if the articled version refers to a specific group of pupils including the speaker. Naturally, the speaker cannot simultaneously be a member of the “others” group going to the cinema, as presupposed by the use of first person unagreement in the second clause. For the first example, this problem does not arise: the speaker is only presupposed to be a student by quantificational unagreement, but not necessarily a member of the group going to the theatre.Footnote 21

Notice further that floating quantifiers are more permissive than the remaining quantifiers with respect to the realisation of Pers. The Greek and Spanish sentences in (77) both allow an overt person marker.

-

(77)

As far as unagreement is concerned, the analysis from Sect. 6 directly extends to the floating quantifier cases. The restrictor of the quantifier is a regular PersP subject to the presupposition introduced by Pers. The crucial point is that the overt realisation of Pers is supported by a definite article in these expressions, in contrast to the quantifiers discussed above.

6.3 Object unagreement

The object unagreement data in Sect. 3.3 have shown that, in addition to subject unagreement, Greek also allows (apparent) person mismatches between objects and object clitics. Similar facts hold for Spanish, as exemplified in (1) by the relation between the first person plural clitic nos and the indirect object a los familiares ‘to the relatives’, and in the Bulgarian example in (2), where the direct object studentite ‘the students’ is doubled by a second person plural clitic.

-

(78)

-

(79)

Note that usually only certain southern American varieties of Spanish (Rio-Platense) allow clitic doubling of non-pronominal direct objects, while all varieties require doubling of pronominal objects. In that context, the observation in (80) that even Peninsular Spanish allows object unagreement with direct objects suggests that the object xnP shares some relevant property with pronouns. This is highly compatible with the current proposal, where the xnP carries person features.

-

(80)

It is worth noting that, independently of clitic doubling, object unagreement can also be found in cases that more clearly involve object agreement, cf. the Georgian example in (1) due to George Hewitt (personal communication).

-

(81)

These instances of object unagreement do not come as a surprise under the present analysis. As far as languages with object agreement are concerned, a probe with unvalued φ-features agrees with the features encoded within the object xnP, just as in subject unagreement and the same considerations as above apply. Under an analysis of clitic doubling as a form of object agreement (e.g. Sportiche 1996; Franco 2000), nothing more needs to be said.

An alternative line of research (e.g. Uriagereka 1995; Papangeli 2000) relates clitics to determiners, suggesting that they head an argument DP. These D heads receive a theta-role from the verb and eventually head-adjoin to the verb, accounting for their clitic properties. Clitic doubling is explained in terms of a “big DP”, where the doubled DP is located either in the specifier of the clitic determiner (Uriagereka 1995) or in its complement (Papangeli 2000).

The big DP hypothesis raises some questions as to whether first and second person clitics in unagreement languages start out in Pers instead of D, in which case we would actually be dealing with a big PersP, or whether they are special D heads with unvalued φ-features that agree with those in the doubled object. The common argument for the big DP hypothesis from the parallels in form between articles and third person clitics seems to favour the latter view, as does the fact that in the present discussion Pers has so far only been taken to spell out full rather than clitic pronouns.Footnote 22 In this case, the clitic D head simply agrees with the φ-features of the xnP in its specifier or complement, while the Pers features in that xnP can remain silent as discussed.

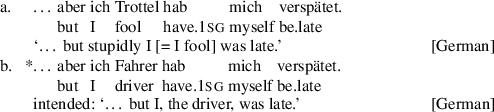

6.4 Type I APCs and the lack of unagreement

Let us now turn to the absence of unagreement in languages like Italian with type I APCs. Adopting the [±dem] feature yields the structure in (1) for the xnP of type I APCs. This is independent of whether a given language shows pro-drop, as it is also found in APCs in German and English. However, for the purpose of investigating unagreement I will focus on null subject languages with this configuration, in particular on the example of Italian.Footnote 23

-

(82)

As discussed in Sects. 2 and 5.1, this language lacks the typical unagreement configuration. Given (0), there appear to be two potential ways of getting to an unagreement-like configuration in principle. Either D could be realised by the definite article, which would give the string-equivalent of the basic unagreement construction with a definite plural noun phrase and non-third person verbal agreement. This is ungrammatical as shown earlier, and a pronominal determiner would be required instead as in (1). Alternatively, one might consider the option of zero spell-out of the head bearing person features which is central to the analysis of unagreement in Sect. 6.1. On the basis of (0) this would result in a bare noun, which is also ungrammatical as shown in (2). I will discuss the absence of both options of deriving unagreement in turn.

-

(83)

-

(84)

I propose that the fact that definiteness and person are encoded on the same head in the structure in (82) is crucial for understanding the data in (-1). In this configuration, the definite article and pronominal determiners are competing for insertion into the same node, deriving the facts in (-1) as follows.

As pointed out in the discussion surrounding the English example (66) in Sect. 6.1, pronominal determiners can correspond not only to the definite article, but also to a demonstrative. The same holds for Italian as shown in (1). In order to report an utterance contrasting two groups of students, one of which contains the speaker like in (85-a), a demonstrative needs to be used in place of the pronominal determiner, cf. (85-b).Footnote 24

-

(85)

While in many contexts where the definite article can be used to report a pronominal determiner, it is in principle possible to use a demonstrative as well, generic contexts block the demonstrative. This is the case in (1) in a situation where an Italian student mentions (86-a). In order to report this utterance, someone who is not a student would use the definite article rather than a demonstrative in place of the pronominal as shown in (86-b).

-

(86)

From these observations I conclude that pronominal determiners can correspond to both definite articles and demonstratives in Italian as well. Correspondingly, I assume that the VI noi is underspecified for [±dem]. Following Postal’s (1969) insights, the definite article is treated as third person, i.e. [−auth,−part]. Abstracting away from the phonological conditions governing the use of gli vs. i for the definite article, we can then assume the VIs in (1).

-

(87)

D[+auth,+part,+def,pl] ↔ noi

D[−auth,−part,+def,pl,masc] ↔ i/gli

In an APC like (82) D is syntactically specified as [+auth,+part]. Consequently, the VI of the definite article i/gli cannot be inserted as it is specified as [−auth,−part].Footnote 25 Instead, the properly specified noi wins, yielding the grammatical version of (83).

The second ungrammatical option of deriving unagreement, in (84), would have a definite bare plural as unagreeing subject. However, in Italian and other Romance languages bare plurals cannot be definite even where they arise, and are generally ruled out in subject position (Longobardi 1994; Chierchia 1998). So whatever rules out bare definites in Italian in general, rules them out in unagreement contexts. In the next section I will additionally discuss a way in which this issue links up to an approach to (full) null subject in both Italian- and Greek-type languages.

It has been pointed out to me that this view seems to retain the possibility of unagreement with bare nouns in languages with a freer distribution of bare nouns. That is not a bad result however, considering that languages like Swahili and Georgian appear to indeed allow unagreement, cf. Sect. 2. As discussed there, I leave open the question as to why some other languages that allow definite interpretations of bare nouns (Turkish, Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian) do not allow unagreement.

6.5 The null spell-out of pro

In this section I am going to situate unagreement and its absence in a typology of the overtness of parts of the extended nominal projection, based on an analysis of so-called pro subjects in Greek- and Italian-type languages in terms of radical zero spell-out of all heads in the xnP.

While this type of analysis seems initially problematic due to the lack a silent definite article in those languages (Panagiotidis 2002, 126f.), I argue that there is a phonologically conditioned silent allomorph of the definite article which applies in the relevant contexts.

The Greek definite article is a phonological clitic, more specifically a proclitic. Hence it needs to be hosted by a prosodic word to its right. Under the hypothesis that pronouns and demonstratives involve Panagiotidis’ (2002) empty noun eN, cf. Sect. 5, we can observe a locality requirement that the host be—at least—a member of the same xnP as the article. Consequently, the article cannot be final in the xnP as illustrated in (1).Footnote 26

-

(88)

The same requirement of phonological material to the right of the definite article holds in Spanish and Portuguese, as observed in discussions of noun ellipsis (Raposo 2002; Kornfeld and Saab 2004; Ticio 2010, 184–186). Since it relies on the phonological properties of the members of DP, this is arguably not a syntactic, but a morpho-phonological restriction, which applies after spell-out.

For concreteness, I propose to model this in terms of contextually conditioned allomorphy, specifically Embick’s (2010) \(\mathbb {C}_{1}\)-LIN theory. Since the pronoun in Greek-type APCs forms a separate prosodic word, it seems a reasonable assumption that the DP defines a separate PF cycle in Embick’s terms. We can then say that the null VI in (1) is inserted iff no overt material (more specifically, no prosodic word) is contained in the same PF domain. This holds irrespective of the cliticisation direction of the article in the specific language, and therefore extends to Bulgarian and Aromanian.Footnote 27

-

(89)

D[+def] ↔ ∅ / _ ]PF cycle

D[+def,pl,masc] ↔ oi

This proposal follows the intuition of the ‘Stranded Affix’ filter of Lasnik (1981, 1995) as well as Embick and Noyer’s (2001) suggestion of a morphophonological requirement that “D[def] must have a host” (p. 581) in their account of Scandinavian definiteness marking. Interestingly, the cases discussed here seem to make use of a different strategy to avoid a violation of this constraint, namely non-spell out of D rather than insertion of a supporting morpheme as in do-support or Embick and Noyer’s (2001) analysis of Swedish and Danish.

Now remember the structure suggested for type II APCs, repeated in (90). According to the present analysis, the overtness of Pers and NumP is determined independently of their context but only by their inherent properties—namely by the specification of [±dem] for Pers and the lexical choice of the constituents of NumP respectively. As before, I will not be concerned with Num and assume that it is either null by default or gets realised by movement of N to Num. The overtness of definite D, on the other hand, is dependent on the phonological properties of its complement and hence contextually determined. This also accounts for the fact that there are no stranded definite articles in plain pronouns (e.g. Spanish nosotras (*las) ‘we. f (*the. f. pl)’).

-

(90)

[PersP Pers [DP D [NumP Num [nP N/eN ] ] ] ]

The interaction between the two remaining independent variables of overtness maps onto attested constructions as in (91), illustrating the relation between APCs, pronouns, null subjects and unagreement in the current analysis.

-

(91)

Possible realisations of xnP (90)

overt Pers

silent Pers

overt NumP

APC

unagreement (regular DPs)

silent NumP (eN)

pronoun

pro

Let us now consider the case of languages with type I APCs, where person features are encoded on D, yielding a classical pronominal determiner structure like (1).

-

(92)

[DP D [NumP [nP N/eN ] ] ]

I suggest that just like the languages discussed above, Italian has a null allomorph of the definite article which is triggered in contexts without other overt material in its spell-out domain, presumably also because of its procliticising nature. Due to the pronominal determiner structure of type I APC, this VI is also directly involved in the derivation of null subjects. By hypothesis, it is therefore sensitive to a [−dem] feature as indicated in the VI entry in (1). For ease of reference, the VIs for the first person plural pronominal determiner and the definite article are also repeated in (2).

-

(93)

D[+def,−dem] ↔ ∅ / _ ]PF cycle

-

(94)

D[+auth,+part,+def,pl] ↔ noi

D[−auth,−part,+def,pl,masc] ↔ i/gli

This also rules out definite bare plurals as a possible source of unagreement as in (84) above: once there is an overt noun (or adjective) in the xnP, the contextual condition for the null allomorph is not met and an overt VI, e.g. out of (0), is inserted.

It also facilitates a radical zero spell-out analysis of pro. In parallel to the above discussion of type II APCs, the overtness of NumP is intrinsically determined by the phonological properties of its constituents. The contextual restriction governing the silence of definite D is also essentially the same as the one discussed for type II APCs above. However, in type I APC structures this restriction simultaneously affects the spell-out of person features, which are encoded on the same head. Unlike in type II APCs, then, a [−dem] specification is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for their silence. Only if the contextual condition is fulfilled, i.e. if NumP is silent, can a definite D with [−dem] specification be silent too, yielding the phenomenon known as pro by not spelling out any head in xnP. Alternatively, a [+dem] specification leads to spell-out of D and hence an overt pronoun.