Abstract

This paper addresses the interaction between morphology and syntax in cases where the morphological realization of a structure appears to determine its grammaticality. The empirical focus of the discussion is the go get construction (Zwicky 1969; et seq.), a construction which in English is subject to a strict morphological restriction, only being possible with “bare” morphology. It is proposed that this kind of surface-oriented restriction can be accounted for within the morphological component on the assumption that the syntax can place multiple sets of features on a verb: these multiple feature sets will be interpretable within the morphology only when all sets of features converge on a single realization. The analysis developed for English is then generalized to analogues of the go get construction in languages that show morphological restrictions different from the one seen in English: Marsalese (Cardinaletti and Giusti 2001), Modern Greek, and Modern Hebrew, and an outline is given for its extension to other phenomena in which morphological syncretism is able to resolve cases of syntactic feature conflicts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper discusses the go get construction, an analysis-neutral label adopted from Pullum (1990).Footnote 1 In this construction, exemplified in (1), the motion verb go or come is immediately followed by a second verb.

-

(1)

-

a.

Go get me a coffee!

-

b.

I expected him to come visit again soon.

-

c.

Every morning I go buy a coffee.

-

d.

*Every morning he goes buys a coffee.

-

a.

The go get construction was first discussed in the generative literature by Zwicky (1969), who observed that it is subject to a morphological restriction: it is only possible in environments that call for an uninflected or bare verb (1-a)–(1-b), or for a form of the verb that is syncretic (homophonous) to the bare verb (1-c). Overtly inflected verbs are ungrammatical here, as seen in (1-d).

This morphological restriction is perhaps the most striking feature of the go get construction, and has been the focus of much previous work, including largely descriptive papers by Zwicky (1969), Shopen (1971), Carden and Pesetsky (1977), Pullum (1990), and Wulff (2006), and more theoretically-focused papers by Jaeggli and Hyams (1993), Pollock (1994), and Cardinaletti and Giusti (2001). These previous analyses all focus on the bareness of inflection in examples like (1-a)–(1-c), and all propose purely syntactic explanations of the configurations in which inflectional features can be licensed in the construction.

In contrast to these previous approaches, I argue in this paper that the go get construction’s distribution can only be described with reference to the surface morphological properties of individual verb paradigms. The morphological restriction cannot be explained in purely syntactic terms: its analysis must instead be distributed between syntactic and morphological components of the grammar.

I propose that the morphological restriction in (1)—to be described in greater detail in Sect. 2—arises from the syntax imposing two (potentially) incompatible inflectional features on a single element. I argue that such structures are syntactically licit, but can only be realized morphologically if there is a single form that is syncretic for the conflicting inflectional features. This type of approach, where underspecified morphology is able to resolve syntactic feature conflicts, has been widely pursued within the lexicalist frameworks of LFG and HPSG (Zaenen and Karttunen 1984; Pullum and Zwicky 1986; Sadler and Spencer 2000; Dalrymple and Kaplan 2000; Dalrymple et al. 2009, among many others), but has received comparatively little attention within Minimalist syntactic frameworks, or within the post-syntactic morphological theory of Distributed Morphology (DM: Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994, et seq.). The theoretical goal of this paper, pursued in Sect. 3, is to show that syntactic feature conflicts can be created in a syntax driven by the operation Agree (Chomsky 1995), and resolved by a post-syntactic morphology.

Beyond giving a better account of the English data, I demonstrate that this approach has a further advantage over previous analyses in being able to extend to analogues of the go get construction in other languages. In Sect. 4 I discuss similar constructions in the Marsalese dialect of Italian (Cardinaletti and Giusti 2001), Modern Greek, and Modern Hebrew, all of which exhibit a similar morphological restriction, but one that cannot be described in terms of inflectional bareness. I argue the go get construction receives a unified analysis across all these languages if the verbs in this construction are required to resemble the imperative verb form in the language—a requirement that gives rise to different surface results due to independent properties of the language’s inflectional systems. Previous accounts, discussed in further detail in Sect. 5, do not permit the same unification.

2 Morphological properties of the go get construction

This section describes the go get construction and its morphological restriction, drawing on the observations in Zwicky (1969), Shopen (1971) and Carden and Pesetsky (1977).

When looking at this construction, two properties present themselves immediately: the first is that the go get construction is very lexically restricted, being possible only with the verbs come and go;Footnote 2 the second is its morphological restriction, illustrated already in (1).

The morphological restriction can be divided into two parts, a separation proposed by Pullum (1990). The first is that the construction is limited (in English) to bare inflectional contexts, what Pullum calls the inflection condition. The second part of the restriction is that both verbs in the construction show the same inflection, Pullum’s identity condition.

The inflection condition, seen already in (1), is further illustrated in (2). The bare inflection allowed in the go get construction includes imperatives (2-a); to-infinitives (2-b); modal complements (2-c); and subjunctives (2-d). It also includes non-3rd-singular present tense verbs, as in (2-e):

-

(2)

-

a.

Come visit us next week.

-

b.

I want to go take a nap.

-

c.

Birds will come play in your birdbath.

-

d.

Her supervisor demanded that she go buy a replacement.

-

e.

I/you/we/they go get the paper every morning.

-

a.

All overtly inflected verb forms, including the present tense with third-person singular agreement (3-a), are excluded (Zwicky 1969):Footnote 3

-

(3)

-

a.

*She goes gets / go gets / goes get the paper every morning.

-

b.

*Our neighbour came left / come left / came leave a note on our door.

-

c.

*Clare has gone bought / go bought / gone buy the newspaper already.

-

d.

*Susan is coming having / come having / coming have lunch with us.

-

a.

The contrast between (2-e) and (3-a) is particularly striking, because it illustrates that it is the surface phonological properties of the verb forms involved, rather than their formal features, that determines grammaticality. The data in (4)further confirm that the contrast between these examples is really morphological, rather than being (for example) an incompatibility between the go get construction and specifically third-singular subjects, or between the construction and past tense semantics. In (4), Do-support is triggered by negation or by Subject-Aux inversion, resulting in a bare form of the main verbs. This ‘rescues’ the ungrammatical examples from (3-a-b), though the third-singular subjects and past tense semantics remain:Footnote 4

-

(4)

-

a.

Does she go get the paper every morning?

-

b.

Did our neighbour come leave a note on our door?

-

c.

She doesn’t go get the paper every morning.

-

d.

Our neighbour didn’t come leave a note on our door.

-

a.

Previous accounts of the inflection condition have focused on the bareness of the morphological environments involved, proposing that the go get construction is licensed in these environments because null affixes (or the syntactic features that license them) are literally absent from syntactic derivations (Jaeggli and Hyams 1993; Pollock 1994; Cardinaletti and Giusti 2001). Such proposals are consistent with what we have seen so far, as would be the possibility that the inflection condition applies only to the first verb in the construction (go or come), while the second is simply a selected-for bare infinitive.

These previous approaches cannot be entirely correct, however. If the bareness restriction arose from the abstract formal representation of verbal inflection, we would not predict any effect of inflectional irregularity, contrary to fact. The go get construction has a different distribution with irregular verbs, whose bare forms occur in a different set of environments. The data that show this also illustrate Pullum’s identity condition, the requirement that both verbs in the go get construction surface with the same morphology.

As noted by Zwicky (1969), the behaviour of be as the second verb in the construction shows that the second verb is not simply a bare infinitive, as well as illustrating the effect of morphological irregularity on the go get construction. Be is the one verb in English that has morphological alternations where other verbs have a consistently bare form. Zwicky observed that be is possible in the go get construction only when the wider syntactic environment would independently allow it to surface in its non-finite form (as in (5)). Whenever the wider environment would have independently required be to surface in one of its suppletive inflected forms it is barred from the construction, unable to surface either as be or as am, are, is, etc. (shown in (6)).

-

(5)

-

a.

The coach told the lacrosse player to go be examined by a doctor.

( …to be examined …)

-

b.

Helen asked Jacob to come be in the audience at her next play.

( …to be in the audience …)

-

a.

-

(6)

-

a.

*Lacrosse players go be/are examined by a doctor after every head injury.

-

b.

*I come be/am supportive whenever a friend asks me to.

-

a.

Were the second verb merely required to be a bare infinitive, we would expect invariant be to be grammatical in all these examples.Footnote 5 The fact that be is not grammatical in this environment suggests that both verbs in the go get construction are required to reflect the morphological requirements of the wider syntactic environment: that is, they are required to express the same inflectional features.

The facts involving be also illustrate the surface-oriented nature of the inflection condition. If the requirement for inflectional bareness arose from the licensing possibilities for formal features, irregularities in individual verbs’ paradigms should be irrelevant. We would expect that particular syntactic environments would always result in either grammaticality or ungrammaticality for the go get construction, regardless of the actual morphological paradigms of the verbs involved. If this were the case, the inflected forms are and am would be grammatical in (6), just as regular present tense forms are grammatical in (2-e).

Parallel conclusions can be drawn from observing the go get construction under perfect have (Pullum 1990). As we saw already in (3), sequences like *have gone bought / buy are ungrammatical because the participle gone always contravenes the inflection condition. The participial form of come, by contrast, is homophonous to its bare form. This syncretism is insufficient by itself to license the go get construction in the perfect, however: despite its bare perfect participle, come cannot be followed by either a bare infinitive or by a verb with an overtly-marked participle:

-

(7)

-

a.

*Alex has come knock/knocked on my door three times.

-

b.

*Jacob has come buy/bought a paper every day this week.

-

c.

*Helen has come visit/visited her grandmother only twice.

-

a.

Pullum (1990) observes, however, that if the second verb is also a verb with an irregularly bare perfect participle, the judgments improve for many (though not all) speakers:Footnote 6

-

(8)

-

a.

Alex has come hit the piñata three times.

-

b.

Jacob has come shut the door.

-

c.

Helen has come put the vase on the stand.

-

a.

The fact that the go get construction is possible under perfect have only when both verbs have bare perfect participles illustrates two things. First, it confirms the existence of the identity condition: the second verb is not required simply to be non-finite, but is instead required to express the same inflection as the motion verb. Second, it provides further evidence that the inflection condition is evaluated not within the narrow syntax, in terms of abstract features, but instead with reference to surface morphological realization. Though we might imagine that there is a systematic syntactic difference between regular bare and non-bare verbal inflections (i.e. between the third-person singular and all other person-number combinations in the English present tense), it is not particularly credible to imagine a similar difference between the syntactic representations of regular participles and the approximately twenty-five idiosyntactically bare participles like come.

2.1 Comparison with purpose infinitives and asymmetric coordinations

Taken together, the inflection and identity conditions distinguish the go get construction from two superficially similar constructions: motion verbs followed by a to-infinitive (go to get), and asymmetric VP coordination (go and get).

Motion verbs followed by to-infinitives display neither the inflection condition nor the identity condition (They have gone to buy groceries). Furthermore, Shopen (1971) observes that the two constructions have different truth conditions: while (9-a), containing a purpose infinitive, can be a truthful description of some situation, (9-b), containing the go get construction, is a contradiction:

-

(9)

-

a.

They go to buy vegetables every day, but there never are any vegetables.

-

b.

# They go buy vegetables every day, but there never are any vegetables.

(Shopen 1971:258, ex. 12)

-

a.

Asymmetric VP coordination (called asymmetric because the conjoined verbs are not reversible and the second conjunct is not an island for extraction) is slightly more difficult to distinguish from the go get construction, though it has generally been claimed to not be constrained by the inflection condition (Zwicky 1969; Shopen 1971; Pullum 1990).Footnote 7

-

(10)

-

a.

Yesterday I went and bought vegetables.

-

b.

Helen is coming and visiting us this summer.

-

c.

What has Charlie gone and done now?

-

a.

Shopen (1971) observes two other differences between asymmetric coordination and the go get construction, though these differences have been occasionally overlooked in subsequent discussions. The first is iterability; Shopen reports (attributing the observation to Charles Bird) that the go get construction can be iterated, as in (11-a), while asymmetric coordination cannot be.

-

(11)

-

a.

Come go eat lunch with us!

-

b.

What meal did you ask him to come go eat with us?

-

c.

??Come and go and eat lunch with us!

-

d.

*What meal did you ask him to come and go and eat with us?

-

a.

The second relevant property is that the go get construction requires its subject to be agentive, while asymmetric coordination does not.

-

(12)

-

a.

#The driftwood will come wash up on the shore.

-

b.

#The smoke will go fill up the neighbours’ apartment.

-

a.

-

(13)

-

a.

The driftwood will come and wash up on the shore.

-

b.

The smoke will go and fill up the neighbours’ apartment.

-

a.

This agentivity requirement is particularly interesting for the light it casts on a possible source for the inflection condition, as we will see in the next section.

A further contrast between the go get construction and asymmetric coordination involves the material that can intervene between the two verbs. Asymmetric coordination allows not only adverbs but also locative modifiers and appositive clauses to occur between the two verbs (in addition to the coordinator and itself), while the go get construction allows only low adverbs, as seen in (15).

-

(14)

-

a.

Kate plans to go and write a letter.

-

b.

Kate plans to go and carefully write a letter.

-

c.

Kate plans to go home and write a letter.

-

d.

Kate plans to go and, I believe, write a letter.

-

a.

-

(15)

-

a.

Kate plans to go write a letter.

-

b.

Kate plans to go carefully write a letter.

-

c.

*Kate plans to go home write a letter.

-

d.

*Kate plans to go, I believe, write a letter.

-

a.

These facts suggest that the go get construction involves a very close structural relationship between the motion verb and the second verb, closer even than the one seen in asymmetric coordination.

2.2 Stating the generalization

We have seen so far that the morphological restrictions on the go get construction cannot be stated in terms of abstract formal properties (i.e. syntactic structure or formal features), but instead require reference to the surface form of a verb: whether its morphological form is appropriately ‘bare’. At the same time, the morphological form of both verbs must be appropriate for the wider syntactic environment, as shown by the impossibility of be as the second verb in the present tense.

In other words, it appears that the syntax imposes two distinct inflectional requirements on the verbs in the go get construction. Stated in terms of inflectional features, the two verbs bear not only the features required by the wider syntactic environment (the features that in the ordinary course of events would accrue on a main verb), but also some additional construction-specific feature ([F]), a feature consistent only with bare morphology.

The core of the analysis to be proposed in the next section is that this multiple-feature configuration is always syntactically licit. It is the morphological component that rules out the go get construction whenever there is no single output form that can express both [F] and the verbs’ other features.

What could this construction-specific feature [F] be? Ideally it should be a feature plausibly associated with the structure or the interpretation of the go get construction. For example, it could be a non-finite or subjunctive feature: both these features are canonically associated with verbal complements in English. [F] could also be an imperative inflectional feature, as imperatives in English are also systematically bare.

Though identifying [F] with imperativity might at first seem the least plausible of these options, there are a number of ways in which the go get construction does seem to resemble the imperative. First, we saw above that the go get construction requires an agentive subject, a property shared with the (often implicit) subjects of imperatives, which must be capable of volitionally carrying out the commanded action. This accounts for the marginal status of imperatives like (16-a). Non-agentive predicates that are odd in imperatives are also pragmatically odd in the go get construction: (16-b) cannot be said even by a tall person who is moving to stand in an indicated position (except perhaps as a joke).

-

(16)

-

a.

# Be tall!

-

b.

# I will go be tall over there.

-

a.

While an imperative inflectional feature is neither necessary nor sufficient to explain the agentivity requirement on the go get construction—an inflectional feature does not necessarily imply the syntax or the semantics of imperatives—it is a point in favour of a connection.

Second, there is some evidence that the go get construction is associated with imperative or directive force, both historically and synchronically. The earliest examples of the go get construction provided in the Oxford English Dictionary occur either in imperative clauses or under directive modals (“go v.”, 2010, III.32a), and Zwicky (2003), reporting on an unpublished study of a corpus of film scripts, claims that the go get construction is most frequently found in imperative clauses.

Finally, we will see in Sect. 4 that imperativity descriptively unifies morphological restrictions on the go get construction in a number of different languages: in Modern Greek and Modern Hebrew the go get construction is possible only in the morphological imperative, while in the Italian dialect Marsalese the construction is possible only in inflections that call for a default stem—the stem that is identical to the canonical morphological imperative, but not the stem form used in either the infinitive or the subjunctive.

For these reasons, I argue that [F] should be identified as whatever inflectional feature results in imperative morphology (bare in English, overt in other languages). Appealing to a semantic link between imperativity and a motion-verb construction, the idea of internally caused or directed motion, I abbreviate this feature as [infl:dir], where dir is one possible value for a general verbal inflectional feature. The abbreviation dir in intended to recollect directed action, with the ambiguity of directed between imperative and directional senses being intentional.Footnote 8

The go get construction in English, however, is neither semantically nor syntactically imperative, and so the relevant feature cannot be directly responsible for either semantic imperative force or the characteristic syntax of imperative clauses. The analysis developed below, particularly in Sect. 3.2, encodes this by proposing that the feature [infl:dir] is never formally interpretable in the go get construction. Its presence can be analogized to certain accounts of deponent verbs in languages like Latin. Deponent verbs are those that appear with passive inflection despite having apparently active syntax and interpretation. This is often formalized by assigning an arbitrary passive inflectional feature to deponent roots (Embick 2000; Sadler and Spencer 2000; Kiparsky 2004). Embick (2000) in particular argues that this arbitrary feature is visible in the syntax and the morphology, but inert with respect to argument structure and semantic interpretation.

Whether this is ultimately the correct account of deponency,Footnote 9 it provides a framework for understanding the role of [infl:dir] in the go get construction. This feature, being associated with agentively directed action, is a component of imperative syntax, but can occur independently of imperative interpretation in other contexts. In particular, it can occur in a low position within the clause—proposed below to be agentive \(v^{0}\)—where it provides a syntactic link between the requirement for bare morphology and the imperative-like properties of the go get construction outlined above.

3 Analysis

The previous section demonstrated that the go get construction is subject to two morphological restrictions: the identity condition, requiring that both verbs surface with the same inflection, and the inflection condition, requiring that the verbs appear in a bare form. I have argued that the inflection condition arises because the syntax assigns multiple (potentially conflicting) features to the two verbs: the inflectional feature(s) required by the wider syntactic environment, as well as a feature ([infl:dir]) that is elsewhere associated with imperative inflection. More concretely, the verbs in (17)bear not only [infl:past] but also [infl:dir], as schematically represented in (18). The sentence is proposed to be ungrammatical because the morphological component is unable to simultaneously realize both these features on a single verb.

-

(17)

*Alice came visited her aunt.

-

(18)

come {[infl:dir],[infl:past]}

visit {[infl:dir],[infl:past]}

This line of analysis—the idea that morphological syncretism can resolve syntactic feature conflicts—has been widely pursued within the lexicalist syntactic models of LFG and HPSG (Zaenen and Karttunen 1984; Pullum and Zwicky 1986; Sadler and Spencer 2000; Dalrymple and Kaplan 2000; Dalrymple et al. 2009, among many others). These approaches have in common the idea that syncretic morphological forms always bring multiple (or at least less specified) feature values into the syntactic representation. Consider for example case syncretism in the English pronominal system. The masculine pronouns his and him could be unambiguously specified for [genitive] and [accusative] features, respectively, but the syncretic feminine pronoun her, by contrast, might be syntactically represented as having the case value [genitive, accusative].Footnote 10

Indeterminate feature representations of this kind are broadly incompatible, however, with the Minimalist view of syntax adopted here. Lexicalist approaches within Minimalism require that words and morphemes enter the derivation already inflected, and bearing appropriate syntactic features, but also that every such feature be checked or licensed in the course of a derivation. In this type of lexicalist system, syncretism (and underspecified morphology more generally) is invisible to the syntactic computation: a surface form like her can enter the syntactic derivation either with accusative or genitive features, but not with both. If it did enter with two different sets of features, then one or the other would remain unlicensed at the end of the syntactic derivation, causing a crash at LF.

The insight that some morphology is featurally indeterminate, or underspecified with respect to syntactic features, has instead been pursued within Minimalism and related approaches by the development of post-syntactic realizational theories of morphology, as in Distributed Morphology DM (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994; Harley and Noyer 1999, et seq.). Such theories allow a different approach to resolution-via-syncretism, if we allow that syntactic feature conflicts can render some representations unrealizable, much as some have argued that some syntactic structures are unlinearizable (Citko 2011; Fox and Pesetsky 2005; Richards 2011, a.o.). While classic DM holds that morphology is a purely interpretive system, unable to filter representations in this way, introducing the idea that some structures are morphologically unrealizable due to feature conflicts allows for the possibility that syncretism can resolve those conflicts.

This kind of morphological analysis depends, however, on a syntactic component that is able to create structures with potential feature conflicts. In the case of the go get construction we must account both for the fact that the same inflectional features occur on more than one verb, and for the fact that each verb is assigned multiple (potentially conflicting) inflectional features.

The next two subsections argue that the mechanism of Reverse Agree (Wurmbrand 2011; Zeijlstra 2010, a.o.) naturally accommodates these requirements within the narrow syntax. Reverse Agree, to be introduced further in Sect. 3.1, departs from Chomsky’s (1998) original formulation of Agree by allowing for the downward valuation of features. It has been used to account for the valuation of verbal inflectional features by higher inflectional heads (Adger 2003; Wiklund 2007; Wurmbrand 2011; Bjorkman 2011), including cases where the same inflectional features occur on more than one verb in a clause (Wiklund 2007; Wurmbrand 2012a).Footnote 11 These accounts naturally extend to account for the identity condition in the go get construction, fulfilling the first requirement listed above.

Turning to the question of how the two verbs can be assigned multiple—and potentially conflicting—inflectional feature values, Sect. 3.2 suggests that this should be attributed to the status of the feature [infl:dir] in the go get construction, as a semantically uninterpreted inflectional feature. I argue that if Reverse Agree targets not only unvalued but also uninterpretable features, then verbs bearing uninterpretable-though-valued features remain accessible for Agree, and, as a result, can be assigned multiple values for a single feature type (e.g. infl).

Section 3.3 then discusses the mechanisms whereby certain feature combinations are identified as unrealizable, in the morphological component of the grammar. More concretely, I argue that the presence of more than one feature of a single type on a head, as in (18), requires that that head be subject to multiple parallel applications of vocabulary insertion. This parallel realization is possible only when it converges on a single vocabulary item for the relevant position of exponence—in other words, when the conflicting features are systematically syncretic.

3.1 Accounting for shared inflection

This section develops an account of the identity condition on the go get construction, the requirement that both verbs surface with the same inflection, in terms of Reverse Agree. Several authors have noted that Reverse Agree is naturally suited to account for cases of Multiple Agree (in the sense of Hiraiwa 2001, et seq.). This point is made generally by Zeijlstra (2012), and specifically for verbal inflection by Wurmbrand (2012a).

Before turning to the mechanism of Reverse Agree, though, note that the identity condition is broadly incompatible with the idea that inflectional affixes are the direct realization of functional heads to which a verb moves (Chomsky 1957; Pollock 1989, a.o), rather than of abstract features assigned to verbs. If inflectional affixes realized heads such as T0 or Asp0, it would be impossible for the same affix to appear on more than one verb, unless more than one of the relevant functional head occurs in the structure.Footnote 12

The appearance of identical inflection on more than one verb therefore provides an immediate argument in favour of a more abstract view of inflectional licensing, where inflection is manipulated not as heads but as features. In principle this makes it possible for a single head to license or value inflectional features on more than one verb. In practice, though, approaches to inflection in terms of feature licensing or valuation (e.g. Agree-based approaches) have tended to maintain a one-to-one correspondence between the sources and the targets (i.e. Probes and Goals) of inflectional information.

There is considerable evidence for one-to-many inflectional relationships, however, even limiting our attention to verbal inflection (setting aside cases of multiple \(\upvarphi \)-agreement, for example). One case comes from serial verb constructions: Aikhenvald and Dixon (2007) note that though serialization is often associated with languages that lack verbal inflection altogether, serializing languages with overt inflection often require that inflection to be repeated on each verb in a series:

-

(19)

A more striking case of shared inflection is discussed for the Australian language Lardil in Richards (2009). In this language the future inflectional affix can appear on every element in the verb phrase, including the elements of an object relative clause.

-

(20)

Cases of shared inflection can also be found across the Germanic family, with somewhat different profiles in different languages and constructions. Wiklund (2005, 2007), for example, discusses several such constructions in Swedish, cases where a verb and its complement both occur with the same morphology.

-

(21)

Wurmbrand (2012a) broadens Wiklund’s analysis of the Swedish data to account for a wider range of shared inflection constructions across Germanic languages. Of particular interest here are parasitic participle constructions in Frisian, described by den Dikken and Hoekstra (1997). Analogously to (21-b), in this construction the complement of a participial modal verb can optionally surface also in a participial form.Footnote 13

-

(22)

Wurmbrand (2012a) proposes a Reverse Agree analysis of these facts, as does Wiklund (2007) though she does not discuss at any length the departures from standard Agree. Wurmbrand defines Reverse Agree as in (23):Footnote 14

-

(23)

Reverse Agree (Wurmbrand 2012a, ex. 6)

A feature [F:_] on \(\alpha\) is valued by a feature [F:val] on \(\beta\) iff:

-

a.

\(\beta\) asymmetrically c-commands \(\alpha\) AND

-

b.

There is no \(\gamma\), distinct from \(\beta\), with a valued and interpretable feature of the same type ([iF:val]) such that \(\gamma\) c-commands \(\alpha\) and is c-commanded by \(\beta\).

-

a.

The most significant departure from standard Agree is the direction of c-command in (23-a). While standard Agree transfers feature values upwards, from c-commanded Goals to c-commanding Probes (Chomsky 1998), Reverse Agree allows downwards feature valuation, for example allowing valued interpretable features on T0 to value corresponding uninterpretable features on a main verb.Footnote 15

Which positions are related by Reverse Agree depends on the size of the structure embedded under the higher of the two verbs. Wiklund’s account assumes a fully articulated, but semantically vacuous, non-finite embedded clause. For her, shared inflection involves relationships between matrix and embedded functional heads of the same label: the heads in the embedded clause (C0, T0, Asp0, etc.) Agree with and are valued by their valued (and interpreted) equivalents in the matrix clause. This account avoids having a single functional head value features on more than one lower verb.

This analysis, however, is incompatible with the facts of the go get construction. If the complement of the motion verb were a full clause, we would predict that it could include some overt inflectional material, such as a perfect or progressive auxiliary. (24)shows, however, that progressive be and perfect have cannot occur as the second verb in the construction.

-

(24)

-

a.

*The tour guide said she would go be waiting in the next room.

-

b.

*This director always has the lead actor come be singing during the first scene.

-

c.

*The assistant was told to go have printed the report by the next day.

-

d.

*The doctor recommended that patients come have gotten a blood test.

-

a.

The only auxiliary possible is passive be, as shown in (26).

-

(25)

-

a.

The coach recommended that the players go be examined by a doctor.

-

b.

The detective asked the witness to come be questioned at the station.

-

a.

This distribution of auxiliaries in the go get construction argues that the motion verb occurs in a fixed clausal position, below perfect and progressive projections but higher than passive be. In such a structure, identical inflection on both the motion verb and its complement requires that both establish a relationship with a single higher inflectional head.

Wurmbrand’s (2012a) account of shared inflection, building on proposals in Wurmbrand (2012b, et seq.), has this property, allowing an interpretable and valued inflectional feature ([iinfl:val]) to Agree with and thus value uninterpretable unvalued inflectional features ([uinfl:_]) on more than one lower verb, as in (26-a). Such multiple valuation is blocked, however, if another head with a valued inflectional feature occurs between the two potential targets for Agree, as in (26-b).

-

(26)

-

a.

-

b.

-

a.

Zeijlstra (2012, 2013) argues more generally that one-to-many Agree relationships constitute an argument in favour of Reverse Agree, though they have been discussed in the context of standard Agree by authors such as Hiraiwa (2001) and Henderson (2006), among others.

Wurmbrand’s account of shared verbal inflection is a natural fit for the identity condition in the go get construction. The presence of any interpretable inflectional feature between the two positions would prevent inflectional doubling, by the second sub-clause of (23). This same clause accounts for why there is no inflection doubling in ordinary auxiliary verb constructions: the interpretable inflectional features associated with the progressive or the perfect in English will block Agree relations across them (Wurmbrand 2012b; Bjorkman 2011).

As we saw in (15), moreover, appositives and adverbs such as “carefully” are unable to intervene between the two verbs. This is accounted for if these elements attach no lower than the phrase headed by the motion verb: if the motion verb occupies \(v^{0}\), for example, and these elements adjoin to vP or higher, then they will not be able to surface between the two verbs.Footnote 16 V0 and \(v^{0}\) are moreover in exactly the kind of local relationship required for shared inflection, according to Wurmbrand, because no other inflectional functional head intervenes between them.

This raises the question, though, of why the go get construction would be unique in English in exhibiting an identity condition, if shared inflection simply reflects a local relationship between two verbs. We might expect that light verbs like do or make, for example, would always share inflection with their complement. The fact that such light verbs systematically require bare inflection on their complement requires, on this account, either that the light verb itself values a non-finite inflectional feature on its complement verb, or that the light verb selects a complement that includes a non-finite inflectional head. Whatever the source of non-finite inflection in other light verb constructions, that source must be idiosyncratically absent from the go get construction.

The fact that being assigned a non-finite feature inoculates the complement of light verbs from sharing their inflection raises a further question for the account proposed in Sect. 2 for the inflection condition: if verbs in English typically cannot be assigned more than one inflectional feature, how are they assigned two in the go get construction? The next section turns to this issue.

3.2 Accounting for feature conflicts

Section 2.2 proposed that the inflection condition arises because the two verbs in the go get construction bear not only the inflectional features required by the wider syntactic environment, but also an inflectional feature that requires bare inflection (i.e. [infl:dir]). The contexts where the construction is grammatical are those where these different features would result in the same morphological realization.

This proposal descriptively accounts for the morphological distribution of the go get construction, but it also raises a serious question within an Agree-based system. Regardless of its directionality, Agree is, at its core, a relationship between deficient (uninterpretable/unvalued) and non-deficient instances of a single feature type. A verb is a target for Agree because its inflectional feature is unvalued or uninterpretable ([uinfl:_]). Once that feature is valued (i.e. as [uinfl:dir]), it should no longer be a target for subsequent Agree operations—indeed, even if a further Agree relation could be established, we might ask how the verb could be given a second value for the same feature.

The idea that Agree can assign only one inflectional value to a given verb generally maps very well onto the facts of inflectional morphology in English. Consider a sentence such as (27), with two instances of auxiliary be. A number of authors have argued that the auxiliary verb be occurs as a syntactic or morphological repair, precisely because the main verb cannot realize more than one inflectional suffix (Dechaine 1995; Schütze 2003; Cowper 2010; Bjorkman 2011). Otherwise we would expect sentences like (28)[-a] or (28)[-b] to be possible, with past, progressive, and passive inflection all being realized on the main verb eat (with or without higher auxiliaries as well).

-

(27)

The cake was being eaten.

-

(28)

-

a.

The cake eaten-ing-ed.

-

b.

The cake was being-ed eaten-ing-ed.

-

a.

A straightforward way to exclude (28), while maintaining both the repair view of be and the idea that Agree can value multiple targets, is to limit verbs to a single inflectional feature. The question, then, is not only how multiple valuation is possible in the go get construction, but also how multiple valuation can be allowed here while still being excluded from typical auxiliary verb contexts.

To answer this question, let us consider the status of the feature [infl:dir], a feature associated with imperative inflection but with neither imperative syntax nor imperative interpretation. Section 2.2 suggested that [infl:dir] is not associated with its canonical imperative-related interpretation in the go get construction (excluding cases when the construction occurs in an imperative clause), though it is presumably interpretable elsewhere in English.

If [infl:dir] is radically uninterpretable in the go get construction—if it is a feature value without any associated position of semantic interpretation—this provides a way to understand the fact that the verbs in the construction can be assigned more than one inflectional feature value. Let us assume that every feature in a derivation must be formally associated, via Agree, with an interpretable instance, but that it is not necessary that every individual feature value be directly interpreted at LF. In other words, let us assume that the goal of Agree is not only to value unvalued features, but to “check” features by associating them with interpretable counterparts. In this case, a head bearing only uninterpretable (though valued) features will be a potential target for further Agree operations.Footnote 17 On this view, the verbs in the go get construction remain targets for Agree even after being valued with the arbitrary construction-specific feature [uinfl:dir].

This requires a slight modification to the definition of Reverse Agree adopted in Wurmbrand (2012a), which appeared above in (23). The revised definition appears in (29): the crucial change is the definition of potential targets of Agree as features that are either uninterpretable or unvalued (whereas for Wurmbrand only unvalued features are potential targets for Agree).

-

(29)

Reverse Agree (revised)

An uninterpretable or unvalued feature on \(\alpha\) is valued by a feature [F:val] on \(\beta\) iff:

-

a.

\(\beta\) asymmetrically c-commands \(\alpha\) and

-

b.

There is no \(\gamma\), distinct from \(\beta\), with a valued and interpretable feature of the same type ([iF:val]) such that \(\gamma\) c-commands \(\alpha\) and is c-commanded by \(\beta\).

-

a.

The idea that some feature values, including dir in the go get construction, are syntactically visible but never semantically interpreted, is clearly incompatible with strong versions of Full Interpretation (Chomsky 1995), but this avenue of explanation has frequently been explored for various kinds of morphological quirks. The case of deponent verbs was discussed above: the fact that deponents in Latin require an auxiliary verb in the perfect demonstrates that whatever feature marks them as deponent must be visible within the syntactic component (Embick 2000). Radically uninterpreted features have also been proposed to account for certain cases of pluralia tantum and singularia tantum nouns, nouns that occur only in plural or singular forms regardless of the number of their referents, and perhaps more generally assumed of gender features in languages with arbitrary grammatical gender.

In sum, then, I propose that the reason that the verbs in the go get construction are able to be assigned multiple inflectional feature values is that the first value they are assigned is not associated with any interpretable position. Reverse Agree applies first to the structure in (30-a), yielding the representation in (30-b). I assume that the feature [uinfl:dir] originates on the same head that will be realized by the motion verb, and that this head is \(v^{0}\). The agentivity restriction found in English can be encoded by limiting [uinfl:dir] to agentive instances of \(v^{0}\).

-

(30)

-

a.

-

b.

-

a.

At this point both verbs bear an uninterpretable (though valued) inflectional feature, and so both remain potential targets for further iterations of Reverse Agree. As discussed above in Sect. 3.1, the fact that there is no head with interpretable inflectional features intervening between them means that both verbs can Agree simultaneously with a higher head. When the next head with valued interpretable features is merged, that feature will be able to Agree with the [uinfl ] features on both verbs. This is illustrated for the sentence in (31)by the tree in (32).Footnote 18

-

(31)

Every morning I go buy a coffee.

-

(32)

There are at least three plausible outcomes for an Agree relationship between differently-valued features, as in (32): the original value of the lower feature might be overridden by a new value; the original value of the lower feature might remain unchanged; or both values might co-exist for the lower feature.

The proposed account of the inflection condition, understood as a case of feature conflict resolved by syncretism, requires that third of these options apply. There is some evidence that the other two outcomes are possible in other circumstances, however: Bejar and Massam (1999) survey a number of languages where a DP is able to move between Case positions, and demonstrate that such “multiple Case checking” configurations can be resolved differently on a language-by-language basis, including overwriting the Case value (pronouncing the last-assigned Case), retaining the original Case value (pronouncing the first-assigned Case), and keeping both Case values (pronounceable only when they are syncretic).Footnote 19 Bejar and Massam do not propose a formal account of how DPs can be assigned multiple Case values, but the data they discuss are compatible with the proposal here that Agree can assign new values to already-valued features in some syntactic configurations.

As a concrete implementation of this third option, I suggest that when Agree relates two valued features, the option exists to duplicate the lower uninterpretable feature (the one to be valued, in a Reverse Agree framework), keeping one copy of that feature with its original value and one with the new value. The output of the Agree relation in (32)would therefore be as in (33).

-

(33)

Agree thus results in the assignment of multiple (potentially conflicting) features to both verbs in this structure. The next section addresses the further question of why the morphological component would be required to simultaneously realize both these features.

As a final remark, though, note that in the account proposed here, the presence of two features on each of the verbs in the go get construction (i.e. the inflection condition) is logically independent of the presence of the same features on two different verbs (i.e. the identity condition). This is a positive quality of the analysis: Pullum (1990), based on a survey conducted together with Arnold Zwicky, reports some variation among speakers of English in the form required for the second verb in the construction. Some speakers reported judgments in which only the first verb in the go get construction is subject to the inflection condition (these speakers accept sentences like He has come visited me); this can be accounted for if [infl:dir] is merged in the position of the motion verb but not spread via Agree (it is a purely morphological feature). Others show no evidence of overt inflection on the second verb (they accept sentences like He has come visit me), which suggests the go get construction is behaving like more typical light verb constructions by blocking inflectional spreading onto the second verb. The morphosyntactic oddity of the feature [uinfl:dir] makes this exactly the kind of domain in which we should expect to find variation among speakers, resulting from different strategies for accommodating the exceptional status of this feature.

3.3 Morphological resolution of feature conflicts

The previous two sections have dealt with the syntax of inflection and feature valuation. A crucial assumption has been that structures in which more than one inflectional feature occurs on a verb are always syntactically and semantically licit. It is only in the post-syntactic morphological component that some feature combinations are determined to be unrealizable, and thus ungrammatical.

The idea that morphology can act as a grammatical filter is in conflict with strictly realizational views of morphology, including many approaches within Distributed Morphology. Central to DM is the idea that the ordered Vocabulary Insertion (VI) rules responsible for morphological realization are underspecified. For any single head, VI rules compete to apply, the winning rule being the one whose environment is most specific (or extrinsically earliest-ordered) while still being a subset of the features on the head undergoing realization. On the simplest implementation of this type of system, it will always be possible to give some morphological realization to any position, because, if all else fails, an elsewhere rule can apply to insert a default form.

This guarantee of morphological realizability, however, appears to be too strong. We have already seen that the patterns of ungrammaticality in the go get construction are sensitive not to the abstract features involved but to their surface realizations on particular verbs, as evidenced by the exceptional behaviour of be and irregular participles. Pullum and Zwicky (1986) discuss a number of other cases where the grammaticality of a construction depends on syncretism of the features and lexical items involved. One example, also from the domain of English verbal inflection, involves agreement with disjoined subjects. Pullum and Zwicky observe that though this is in principle possible in English, as illustrated by (34-a), it becomes ungrammatical when the disjoined DPs would require different inflection on the main verb, as is the case with the first and third person pronouns in (34-b).

-

(34)

-

a.

Either they or I sing better than he does.

-

b.

Either she or you *sing/*sings better than I do.

-

a.

As with the go get construction, grammaticality is yet more restricted with present-tense forms of the verb be, as shown in (35).Footnote 20

-

(35)

Either they or I *are / *am / *is going to have to go.

A better known case where feature conflicts can be resolved via syncretism involves Case-matching effects in German free relatives. Groos and van Riemsdijk (1981) observed that, though free relatives in German require the gap and the free relative itself to occur in a position calling for the same Case (36-a-b), this requirement is lifted when the relative pronoun is syncretic for multiple Case values, as the neuter was is for nominative and accusative (36-c):

-

(36)

I follow Groos and van Riemsdijk (1981) in taking the general Case-matching effects to show that the relative pronoun originates in the position associated with the gap in the relative clause. On that view, these data illustrate the fact that the relative pronoun in this construction bears multiple Case features. Sauerland (1996) and Trommer (2002), both working in post-syntactic morphological frameworks, attribute the grammaticality of examples such as (36)to properties of the morphological component itself, rather than to syntax-internal resolution strategies, in line with the approach to the go get construction developed in this paper.

These constructions all share the property of allowing syntactic feature conflicts exactly when those features are morphologically syncretic. If the narrow syntax does not have access to information about the morphophonological forms of individual verbs (the principle of Phonology Free Syntax: Pullum and Zwicky 1986; Zwicky 1969), this requires that we modify a theory such as DM enough to allow morphological ineffability for non-syncretic feature conflicts.

Asarina (2011), looking at cases in which syncretism can resolve Case conflicts in Russian, proposes that, in coordinate structures a head may receive two “sets” of features in the course of a derivation. The empirical focus of her argument is on Right-Node-Raising (RNR) constructions in Russian, in cases where there is a mismatch in the Case features that would be assigned to the right-dislocated argument.

Asarina assumes a multidominant representation for RNR constructions (McCawley 1982; Wilder 1999), and proposes that the right-dislocated argument bears separate Case features for each of the structures of which it is a part. When it reaches the point of spell-out, the argument is subjected to the set of VI rules twice: for each separate tree in which a head occurs, it undergoes VI with the features that are licensed in that tree. A well-formedness condition on the output of the VI rules is that a single head receives the same morpho-phonological realization in all applications of the VI rules. Specifically, Asarina proposes that they must be realized by the same VI rule.

The details of this proposal do not apply to the go get construction, which does not involve coordinate or otherwise multidominant structures. The core insight, however, can be extended: that certain structures force the application of multiple competitions among VI rules, and that the result is grammatical only if the parallel competitions all result in the application of the same rule.

A fully general unification is possible if multiple VI application occurs whenever a single head (a position of exponence) has two features of the same type: two number features ([num:val]), for example, or two Case features ([case:val]), or two inflectional features ([infl:val]). This would apply equally to a multiply-dominated element as to verbs that have Agreed with more than one inflectional head.Footnote 21

The fact that both applications of VI are required to yield the same result has a potentially straightforward explanation. In DM, syntactic heads are the units of morphological exponence (subject to processes of Fusion and Fission): only one VI rule can win the competition to realize any given position, and so only one vocabulary item can be inserted in each head position. If VI rules can apply more than once, however, then this no longer holds: more than one rule could simultaneously win a competition. But if there is still only one position, and thus only one slot for a vocabulary item, it makes sense that parallel applications of VI would be successful only if they converge on the same result.

To illustrate more concretely how multiple application of VI rules would work, consider the example in (37):

-

(37)

*She came visited her grandfather last week.

An abbreviated list of the VI rules that will apply to these structures appears in the leftmost column in (38). According to the analysis advanced above, the verbs in (37)will each trigger two applications of these rules, because they each have two features of the same type (infl) with different values (dir and past). The two applications of VI are illustrated in (38)for visit:Footnote 22

-

(38)

The verbs will both be realized once with the feature [infl:past] (resulting in the surface forms came and visited) and once with the feature [infl:dir] (resulting in come and visit). For both verbs this results in a single position being associated with two different vocabulary items. What I suggest is that this is an impossible morphological representation precisely because it associates two different vocabulary items with a single position of exponence (just as structures are unlinearizable if they require a single element to be linearized in more than one position). The non-identity of the two outputs will result in morphological uninterpretability, and thus crash.

In contrast, if the parallel VI competitions had each converged on the same rule (as would have been the case in She wanted to come visit, for example), the result would be the association of a single vocabulary item with a single position of exponence, even though that association is arrived at for two different reasons.Footnote 23 It is not the application of VI rules itself that renders a representation unrealizable, but instead whether a single position is associated with more than one vocabulary item.

Now imagine that instead of (37), we had a sentence such as (39).

-

(39)

She has come shut the door.

Again, both come and the following verb shut are assigned multiple inflectional feature values in the syntax: here these are [infl:perfect] and [infl:dir]. Both these verbs, however, have idiosyncratically bare perfect participles. This could be the result of a lexically-specified rule of VI that inserts a bare form in the presence of [infl:perfect], but multiplication of VI rules can be avoided by instead proposing a lexically restricted Impoverishment operation that deletes the participial feature on the relevant class of verbs.Footnote 24

-

(40)

Output of Syntax:

shut

come

[infl:perfect]

[infl:perfect]

[infl:dir]

[infl:dir]

Impoverishment:

[infl:perfect] ⟶ ∅ / come, shut, put, hit, …

Input to VI:

shut

come

[infl:dir]

[infl:dir]

Because Impoverishment removes one of the two inflectional features, there is no need for multiple applications of VI rules, and thus no potential for divergent realizations.Footnote 25

The account proposed here for the inflection condition is thus distributed between the syntactic and morphological components. The syntax is responsible for the fact that the verbs bear two distinct features of a single type, but it is the morphological component that requires that both those sets of features result in the same output. Because one of the features assigned in the syntax is [infl:dir], whose spell-out requires a bare imperative verb form, the only licit realization of the verbs will be with bare morphology.Footnote 26

4 The go get construction in other languages

This paper has so far concentrated on the go get construction in English. This section brings in evidence of similar constructions in other languages, showing that these languages support the view that the inflection condition results primarily from morphological rather than syntactic considerations. They also support the view that the inflection condition in English—the restriction to morphologically bare forms—is best described with reference to imperativity.

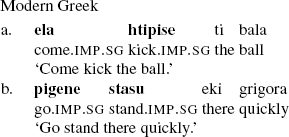

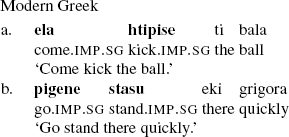

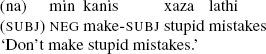

The languages to be discussed in this section are Modern Greek, Modern Hebew, and Marsalese (a southern Italian dialect). Examples of the go get construction in these languages appear in (41)through (43):

-

(41)

-

(42)

-

(43)

What these constructions have in common is that they involve a verb of motion or position followed by another inflected verb. Because these languages all have richer morphology than English, it is evident on the surface that their equivalents of the go get construction obey the identity condition: both verbs occur overtly with the same inflectional morphology.Footnote 27

The relevant constructions in these languages also all exhibit inflectional restrictions similar to English’s inflection condition: both the Greek and Hebrew constructions are restricted to morphologically imperative clauses, while the Marsalese construction is restricted to inflections that call for the default or unmarked verb stem.

The next three sections describe these inflectional restrictions in some detail, illustrating that they can all be understood, like the English inflection condition, as expressions of a requirement that the go get construction appear with imperative-compatible morphology.

4.1 Greek

The data in (44)illustrate the restriction in Greek; note that the construction is possible with the basic verbs of motion pigeno ‘go’, erchome ‘come’, trecho ‘run’, and steko ‘stand’ (and perhaps with some others). For at least some speakers the sequence of two inflected verbs is possible only in the morphological imperative as in (44-a).Footnote 28 Some speakers are more permissive, allowing the construction also in perfective and some imperfective contexts, as in (44-b). No speakers I consulted allowed the construction in verb-particle constructions, such as the future construction in (44-c) with the particle tha.Footnote 29

-

(44)

Because imperative clauses lack subjects in Greek, it is not trivial to conclude that this construction is monoclausal (though this is the intuition reported by native speakers) rather than a sequence of two separate imperatives. In sentences like (45)the sentence-final adverb might grigora ‘quickly’ might appear to necessarily modify the initial motion verb pigene ‘go.imp’, being incompatible with a stative verb like stasu ‘stand.imp’—but, in fact, an imperative like stasu eki grigora is possible as an independent imperative for Greek speakers (with a change-of-state reading for stasu),Footnote 30 and indeed speakers do prefer the adverb in (45)to occur between the two verbs rather than sentence-finally.

-

(45)

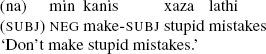

A restriction to imperative verb forms should not be confused with a restriction to command-expressing clauses. The go get construction in Greek is limited specifically to morphologically imperative clauses; it is impossible in clauses expressing negative commands, which in Greek (as in many languages) require a different form of the verb, in this case the subjunctive:

-

(46)

Negative commands expressed in this way do not allow the go get construction, as illustrated by the ungrammaticality of (47-a). While (47-b) is rendered grammatical by the addition of a second licensing subjunctive particle (na), it does not express the negation of an imperative with the go get construction; instead the second subjunctive is interpreted as a purpose adjunct, with this sentence expressing the negation of the (pragmatically odd) imperative clause in (48):

-

(47)

-

(48)

I therefore conclude that the go get construction is limited to truly imperative contexts in Greek.

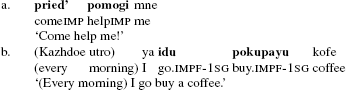

4.2 Hebrew

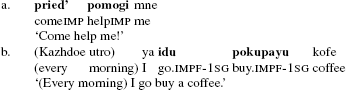

Essentially the same restriction applies in Hebrew as in Greek, though its expression is slightly complicated by developments in the modern language with regards to the morphological form used in imperative contexts. Modern Hebrew has a dedicated morphological imperative formed by truncating the future form of a verb, removing the initial person-number agreement affix.

Motion verbs in this truncated morphological imperative form can be immediately followed by a second morphologically imperative verb, as in (49); both verbs show the same number and gender inflection:Footnote 31

-

(49)

For contemporary speakers of Modern Hebrew, however, the truncated morphological imperative is no longer colloquially used to express commands. For these speakers, the non-truncated second-person future form is used in “imperative” contexts, to issue commands, give permission, etc.: so the prescriptively mandated kra sefer ‘read a book!’ would instead be replaced by tikra sefer, with a second-person future form of the verb ‘read’.

Interestingly, the truncated morphological imperative forms of motion verbs remain in colloquial use; second-person future forms of motion verbs are grammatical in imperative contexts, but appear to be strongly disfavoured.

Even more interesting is the interaction of this second-person future form with the go get construction: for speakers who prefer the non-truncated verb in the imperative, the first verb, the motion verb, is nonetheless required to appear in the prescriptively-mandated truncated imperative, while the second verb appears in the more colloquial second-person future form, as shown in (50-a). It is impossible for both verbs to surface in the second-person future form, as in (50-b). While the string in (50-b) is grammatical, it is only possible as a sequence of imperative clauses.Footnote 32

-

(50)

The go get construction is also impossible in contexts that uniformly require the future form of the verb—contexts that are incompatible with the truncated morphological imperative, including negative commands and ordinary future clauses. This is illustrated for future clauses in (51-a); (51-b) illustrates that the construction remains impossible even if the motion verb itself remains in its imperative form:

-

(51)

Taken together, these facts seem to indicate that while the morphology of Hebrew has collapsed the imperative and future forms of most verbs, it has maintained the distinction for motion verbs. The go get construction, then, does not consist of an imperative verb followed by a second-person future form of a verb, but instead of two imperative verbs, of which the first has an irregularly truncated morphological form.

Tellingly, when both verbs in the go get construction are verbs of motion or position, they both surface as truncated imperatives even in colloquial speech:

-

(52)

The go get construction in Hebrew therefore casts light on the morphological status of the development of the imperative use of future form verbs in Hebrew, as well as reinforcing the conclusion drawn from Greek, that there is some special connection between the go get construction and imperative morphosyntax.

4.3 Marsalese

The inflectional restriction in Marsalese is described in Cardinaletti and Giusti (2001) (also discussed in Cardinaletti and Giusti 2003), and bears more resemblance to the English inflection condition. In Marsalese the go get construction is restricted to contexts where verbs with stem alternations would appear in their default (or ‘unmarked’) form.

According to Cardinaletti and Giusti, the first verb of the Marsalese construction must be one of iri ‘go’, viniri ‘come’, passari ‘come by’, and mannari ‘send’. Of these verbs, iri and veniri show irregular stem alternations: iri, for example, has a default stem va- and a ‘marked’ stem i-/e-, with each stem being selected in particular inflectional contexts. In the present tense the stem va- occurs for all singular subjects, and for third-person plural subjects, while the stem e- occurs in the first-person plural and the stem i- in the second-person plural. As (53)shows, the go get construction is only possible in the singular and with third-person plural subjects, i.e. those cases in which the stem is va-:

-

(53)

The same generalization holds outside the present tense. For example, the past tense, the present imperfective and the subjunctive all take the irregular stem i-, and all are impossible in the go get construction:

-

(54)

Looking at imperative verb forms, the canonical (i.e. singular) imperative, shown in (55-a), consists of a bare default stem, and is possible in the go get construction, while the plural imperative, shown in (55-b), is identical to the second-person plural present tense form; it thus takes the marked stem and does not allow the go get construction:Footnote 33

-

(55)

As in English, then, the Marsalese go get restriction involves restriction to a default verb form, but whereas in English the default inflectional form for any verb is one that is totally bare of inflection, in Marsalese the defaultness requirement is restricted to the stem, which can then be overtly inflected.

Interestingly, Cardinaletti and Giusti report that the go get construction shows the same distributional restrictions when the motion verb lacks a stem alternation. Thus, though a verb such as passari ‘come by’ has only one stem form, it cannot occur in the go get construction in the past, the first- or second-person plural present tense, or the other environments in which iri and veniri surface with a non-default stem. Cardinaletti and Giusti (2001:381) remark that this may indicate that the paradigm for passari does actually have a stem alternation, simply between two homophonous forms.

As in English, it is not a simple matter to describe this inflectional restriction in featural terms. For any individual feature, its ability to occur in the Marsalese go get construction depends on the features with which it co-occurs. In other words, it is not the case that first-person features are themselves excluded, but that they are not possible when they co-occur with singular and present features.

As in other languages, the restriction can nonetheless be described by saying that the Marsalese construction requires a verb form that is compatible not only with some feature [F] (a feature that requires the default form of the stem), but also with the features required by the wider syntactic environment. Marsalese gives clear evidence, moreover, that this feature is not a subjunctive or non-finite feature, because both the infinitive and the subjunctive in this language require non-default stem forms. The canonical (i.e. singular) imperative in Marsalese, however, is a verb form that consists only of the bare unmarked verb stem. The restriction can thus be accounted for if the verbs in the go get construction are required to resemble the canonical morphological imperative, via the presence of an imperative inflectional feature, i.e. [infl:dir].

What this does not entirely explain is the fact that Marsalese, unlike English, does allow additional inflectional material not found in the imperative: the inflectional affixes of the present tense. This issue is taken up in Sect. 4.4, which extends the morphological analysis provided for English to Greek, Hebrew, and Marsalese.

4.4 Extending the morphological analysis

The last three sections have shown that imperativity links the go get construction across several languages other than English. In Greek and Hebrew the restriction is straightforward, the go get construction being possible only in morphologically imperative clauses. The inflection condition in Marsalese is more complex: it requires that the stem appear in its unmarked form (the form that is used in morphologically imperative verbs), but allows further inflectional affixes to occur on both verbs.

The restriction to morphological imperatives in Greek and Hebrew can be easily understood in terms of the presence of a feature [infl:dir]. These languages have unique morphological imperatives, and so the morphological component is unable to resolve any conflict between [infl:dir] and another feature: any features on a verb other than those assigned in a morphologically imperative clause will require a different output form, leading to a crash at the point of morphological realization.

Marsalese, by contrast, more closely resembles English, in the sense that the morphological imperative is identical to the default verb stem, so that the realization of [infl:dir] is in principle compatible with the realization of other inflectional features.

Marsalese differs significantly from English, however, in the scope of [infl:dir]’s effect. If the inflection condition arises from a conflict between two features being realized in a single position, then somehow that conflict must be restricted in Marsalese to the stem, while it affects the entire word in English. The question is how to apparently restrict the scope of this feature in Marsalese without compromising the analysis already proposed for English.

With this question in mind, consider the nature of the overt suffixes that are possible in the Marsalese go get construction. The relevant examples are repeated in (56)from (53). What is significant is that these are all suffixes that mark person and number (\(\upvarphi \)-agreement) only: their analogues in Standard Italian also appear in other tense forms (e.g. the past imperfective).Footnote 34

-

(56)

Assuming that \(\upvarphi \)-features are of a different type than inflectional features for tense, mood, or aspect, there should be no conflict between their realization and the realization of [infl:dir]. For a concrete illustration, consider the verb vaju from (56-a). It occurs in the syntax with both [infl:dir] and [infl:pres] features, as well as first person and singular \(\upvarphi \)-features. The presence of two features of the same type requires two separate applications of VI: I assume that the \(\upvarphi \)-features are visible on both applications, but that [infl:dir] is relevant only for insertion of the stem.Footnote 35 The application of relevant VI rules is illustrated in (57), abstracting away from irrelevant competition among agreement suffixes.Footnote 36

-

(57)

Because the head V0 can only have a single realization, the outputs of the two applications of VI are required to converge, as in this case they do.

In contrast to (57), where [infl:dir] and the other inflectional features trigger VI rules that converge on a single stem form, a sentence with first-person plural agreement, as in (58), will instead trigger conflicting stem insertion as schematized in (59):

-

(58)

-

(59)

Once again, there would be no conflict produced by the VI rules governing affix-insertion, because in all the forms in which the go get construction is grammatical, those rules make reference only to \(\upvarphi \)-features. The conflict in the realization of the stem, however, is irresolvable.Footnote 37

This differs significantly from the situation in English, where suffixes that occur with the default stem do make reference to inflectional features, not only to \(\upvarphi \)-features. Only the third singular suffix -s in English plausibly realizes only agreement, and even on that analysis its insertion must be restricted to contexts that also contain a present-tense feature. There will therefore always be a realizational conflict between [infl:dir] and any overt suffix, regardless of whether they occur after identical (default) stem forms.

5 Previous analyses of the go get construction

The analysis of the go get construction developed in this paper is quite different from analyses proposed previously by Jaeggli and Hyams (1993), Pollock (1994), and Cardinaletti and Giusti (2001). All three of these analyses attempt to account for the inflection condition in terms of the formal syntactic properties of the features or affixes involved; as we will see below, this severely limits their ability to account for the apparently surface-dependent properties of the morphological restriction.

The analyses of both Jaeggli and Hyams (1993) and Pollock (1994) focus on the fact that only ‘bare’ morphology is licit in the go get construction in English. Though differing slightly in detail, they both propose that the syntax of the go get construction is such that it is unable to license Lowered affixes, and that ‘bare’ morphology is nonetheless possible because null affixes are not syntactically represented, at least in English. Because null affixes do not occur in the syntax, there is no question of their Lowering onto the main verb being licensed or not.

Lowering is impossible, for these authors, because the motion verb (the structurally higher of the two verbs) is unable to raise at LF. For Jaeggli and Hyams, this inability to raise results from \(\theta\)-assigning properties of the motion verb: they propose that this verb assigns a secondary agentive \(\theta\)-role to the subject (accounting for the agentivity requirement), but that secondary \(\theta\)-assigners are required to be in their base positions at LF in order to successfully discharge their \(\theta\)-roles. For Pollock, by contrast, the inability of go and come to raise is the result of the second verb incorporating into the motion verb. He proposes that the motion verb cannot covertly raise out of the compound/incorporated verb at LF, and so is prevented from licensing previously-Lowered overt tense affixes.Footnote 38

Both these papers implicitly assume that the second verb in the go get construction is simply a bare infinitive, like the complement of modal auxiliaries, and have no way to account for the fact that a bare infinitival complement is not always grammatical.Footnote 39 If in order to explain the grammaticality of (60-a), we propose that first person singular present-tense features (or affixes) are generally absent from the tree, or do not need to be licensed when they do occur, then it stands to reason that they should also be absent in sentences such as (60-b)—but then we are left without any explanation of the latter sentence’s ungrammaticality.

-

(60)

-

a.

Every morning I go get a coffee.

-

b.

*I go be/am supportive whenever my friend needs me.

-

a.

Similarly, if [infl:perfect] features (or affixes) are usually syntactically represented, thus explaining the impossibility of (61-a), we cannot explain the grammaticality of (61-b) by suddenly suggesting this feature or affix is syntactically absent exactly when it coincidentally has a null realization.

-

(61)

-

a.

*Clare has gone bought a newspaper.

-

b.

Clare has come shut the door.

-

a.