Abstract

Cryptococcus gattii is an endemic fungus predominantly isolated in the tropical and subtropical regions, causing predominantly pulmonary disease with a predilection for the central nervous system. Herein, we report a case of rapidly progressing C. gattii pneumonia in an immune-deficient but virologically suppressed host with underlying human immunodeficiency viral (HIV) infection, exhibiting various fungal morphologies from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytological specimens. A 51-year-old Chinese male with known HIV disease was admitted to the Singapore General Hospital for evaluation of functional decline, febrile episodes, and a left hilar mass on chest radiograph. Computed tomography (CT) showed consolidation in the apical segment of the left lower lobe. He underwent bronchoscopy and BAL. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography done 10 days after the initial CT showed approximate doubling of the pulmonary lesion. Cytological examination of the fluid revealed yeasts of varying sizes. Subsequent fungal culture from BAL fluid grew C. gattii 10 days later.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cryptococcosis is an invasive mycosis, most commonly due to Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii. These fungi are encapsulated basidiomycetous yeasts, and C. neoformans in particular is known for its propensity to cause infection in immunocompromised adults. There are increasing reports of C. gattii causing disease in immunocompromised hosts, and the literature suggests that these infections tend to behave aggressively with poor prognosis [1,2,3]. We report an interesting case of cryptococcosis presenting as an aggressive pulmonary mass in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Case Report

A 51-year-old Chinese man with known human immunodeficiency viral (HIV) disease and stage 3 chronic kidney disease presented with functional decline and non-specific symptoms of generalized paresthesia, lethargy, poor appetite, and fever of 1-week duration. He has known AIDS, diagnosed 6 years ago, and a history of treatment for miliary tuberculosis and cerebral toxoplasmosis. He reported compliance to medications and was HIV virologically suppressed on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), comprising of emtricitabine, tenofovir, and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir. He remained free of opportunistic infections despite low CD4 cell counts (< 150 cells/UL) for the previous three years. His CD4 cell count was 81 cells/UL, and his HIV viral load was 59 copies/ml at this presentation.

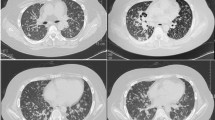

In view of his non-specific symptoms, we evaluated him for underlying malignancies and opportunistic infections. A contrasted computed tomography (CT) scan of his brain showed a stable left thalamic lesion compared with his scan from 6 months ago. Routine investigations revealed that he had iron deficiency anemia, and a chest radiograph (CXR) demonstrated a left hilar mass (Fig. 1a). A contrasted CT scan of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed a well-defined and lobulated consolidative mass in the apical segment of the left lower lobe of his lung, as well as a small left pleural effusion (Fig. 1b). He underwent bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Transbronchial lung biopsy was not attempted as there was no endobronchial lesion seen, and the area of consolidation was not visualized on the fluoroscopy performed during the procedure. His BAL fluid bacterial gram stain and culture, acid-fast bacilli stain, and fungal smears were non-yielding. In view of the proximity of the consolidative mass to his esophagus, a transoesophageal endoscopic biopsy of the lung mass was attempted. Unfortunately, we were unable to visualize the lung mass on endoscopic ultrasound and, hence, no biopsy was done. After endoscopy, the patient developed epigastric pain and bilious vomiting. His repeat CXR did not show evidence of pneumoperitoneum, but there was an increase in the size of the lung mass (Fig. 1c). His positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) F-18 body scan revealed an interval doubling in the size of a lobulated low-density mass with some areas demonstrating non-specific mild metabolic activity (Fig. 1d, e).

Serial radiological progress. a Initial chest radiograph at presentation showing a left hilar mass (arrow); b Initial CT scan of the left lower lobe mass showing approximate maximum diameter of 65 mm (arrowhead); c Repeat chest radiograph after OGD showing interval increase in size of the mass (arrow) (14 days from initial chest radiograph shown in a); d PET-CT image of mass showing interval size increases with approximate maximum diameter 97 mm (arrowhead) (10 days after the first CT in B); e PET-CT image taken from the same day as d showing mild FDG avidity within some areas of the mass (arrowhead); f Interval CT about 3 weeks after PET-CT showing regression in size with maximum diameter 82 mm (arrowhead); g Interval CT after 4 months of treatment showing regression in size with maximum diameter 72 mm (arrowhead); h Interval chest radiograph after 7 months of treatment

BAL fluid cytological examination revealed yeasts varying from 2 to 8 microns in diameter with narrow budding neck and germ-tubes (Fig. 2). The mucicarmine stain highlighted numerous spheres with crinkled and refractive walls consistent with pollen grains, fern spores as well as other yeast-like structures. Yeast cells with thick capsules were visualized on India ink staining. Fungal culture from BAL fluid grew Candida albicans after 5 days. A second yeast was identified as Cryptococcus gattii via subculture on L-canavanine glycine bromothymol blue (CGB) agar 10 days later. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) found the C. gattii strain to be of molecular type VGII. His serum cryptococcal antigen was positive with a titer of 1:256. He had negative fungal blood cultures and an unremarkable cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, including CSF biochemistry, negative CSF cryptococcal antigen, CSF Indian ink microscopy, and CSF fungal cultures.

Microscopic images of BAL fluid showing multiple fungal elements comprising Cryptococcus and Candida, as well as interesting incidental finding of multiple pollen grains and fungal spores. a Thick capsule surrounding the yeast cell visualized in suspension of India ink; b–d mucicarmine stain at various magnifications (Cryptococcus: blue arrow, pollen grain: black arrow, suspected fungal spore: gray arrow); e Cryptococci (blue arrow) seen on Ziehl–Neelsen stain at ×40 magnification; f budding yeast form of Cryptococcus (blue arrow) seen on periodic acid–Schiff staining at ×40 magnification; g multiple yeasts and hyphae; H pollen grains also seen in this patient’s BAL fluid

The patient was treated for pulmonary cryptococcosis with a high dosage of oral fluconazole, 800 mg daily, in view of underlying renal impairment and isolated pulmonary involvement. His repeat CT thorax scan after 3 weeks of antifungal therapy showed a reduction in size of the lung mass, from a maximal diameter of 97–82 mm (Fig. 1f). There were no other concomitant antibiotics prescribed. He reported gradual improvement in his appetite and resolution of fever. He had received 8 weeks of high-dose oral fluconazole and was switched to a maintenance dosage of fluconazole 400 mg daily thereafter. He was 22 months into treatment at the time of this report.

Discussion

Historically, environmental distribution of C. gattii is thought to be limited to the tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Australia, and Africa, with the Eucalyptus camaldulensis genus of flowering vegetation most commonly implicated as an ecological association [4]. We found incidental pollen grains and fern spores in the BAL cytological specimens of our patient and postulated that the origins of the C. gattii infection may be related to environmental exposure. In Singapore, also known as “The Garden City,” Eucalyptus flowering vegetation has been recorded in our gardens from as far back as the year 1910, with sixteen species including Eucalyptus alba, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, and Eucalyptus deglupta [5].

The first reports of human C. gattii infections locally were made in the year 2002 by two separate groups. Taylor et al. [6] reported a case of C. gattii serotype B causing concomitant brain abscess and pneumonia in a healthy adult who had visited Thailand and Malaysia several months before his presentation. Koh et al. reported two cases of C. gattii serotype B meningitis. Their first patient had prior travel to Thailand and also commuted regularly between Singapore and Malaysia, while the second patient visited Indonesia a month prior to his illness [7]. All three cases were described in adults who were immunocompetent. Skin inoculation with the fungus resulting in soft tissue infections was also previously described locally [8, 9]. Considering our local biodiversity in greenery, we explored possible activities and exposures that might put our patient in frequent contact with plants but these concerns proved unfounded in his history.

In a case series of 62 patients with cryptococcosis diagnosed in a local teaching hospital, C. gattii was uncommon and affected only three patients (4.8%). These three patients were immunocompetent and had disseminated cryptococcosis involving both the central nervous and pulmonary systems. Interestingly, all isolates of C. gattii were found to be molecular type VGII, serotype B [10]. From published data on local cases of cryptococcosis, C. gattii infections were exclusive to immunocompetent individuals and were infrequent causative species compared to the C. neoformans. Based on our institution’s laboratory records, there were 93 patients with culture-proven cryptococcosis from January 2005 to June 2017 and only eight patients (8.6%) had infections due to C. gattii. However, the predominant molecular genotype was unknown as typing of Cryptococcus strains was not routinely performed. We recognize that there have been increasing reports of C. gattii infections afflicting up to 30% of the AIDS patients in Africa, predominantly by the VGIV subtype [11, 12]. Our patient adds to the knowledge that C. gattii can occur in an AIDS patient.

Although VGII C. gattii strains predominate in the global veterinary and environmental literature, a recent review of Asian strains of C. gattii suggested that VGI strains (73%) were more frequent compared to VGII strains (19%) [13]. All our locally reported C. gattii infections were of genotypes VGII. Our neighboring country, Malaysia, reported a predominance of VGI isolates (50.0–76.5%) in their C. gattii clinical cases [14, 15], which is a stark contrast to our local epidemiology. Of note, however, there were no C. gattii cases found in the Southern states closer to Singapore. More studies will be required to understand the relationship between environmental sources, exposure, and acquisition of clinical human infections locally.

Our patient presented with an isolated pulmonary mass, and this was congruent with an Australian study, which observed that the radiological presentation of pulmonary C. gatti infections was associated with well-defined pulmonary cryptococcomas. However, this study reported that pulmonary C. neoformans infections were more associated with diffuse interstitial alveolar infiltrates on chest radiographs [16]. Several case reports have featured patients with large pulmonary cryptococcosis masquerading as malignant masses, although no clinical features were reported to differentiate between C. neoformans and C. gattii infections [17,18,19,20,21,22]. We were initially concerned about malignancy in our evaluation of this patient and utilized a PET-CT scan, known for its diagnostic utility for lymphoproliferative disease. The size of our patient’s lung mass doubled within a span of two weeks, and despite such rapid progression, there was only a mild fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the PET-CT scan. Two case series demonstrated a wide range of FDG uptake in the PET-CT scans of patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis, implying that this imaging modality is non-specific in the diagnosis of cryptococcosis [23, 24].

Rat and mouse models suggest a propensity of VGII strains to cause severe pulmonary disease [25, 26]. Clinical human outbreaks reported in the British Columbia, Canada, and the US Pacific Northwest states of Washington and Oregon propose that there may be a genotype-specific virulence pertaining to VGII strains with increased risk of disease in immunocompromised hosts [27, 28]. We postulate that the presentation of a large isolated pulmonary cryptococcoma with a modest regression in mass size after 4 months of antifungal treatment may be associated with the reported VGII molecular type-specific virulence. There remain many uncertainties in the host–environment and host–pathogen interactions, including the role of genotype-specific virulence factors. These will be interesting areas for further study.

References

Mitchell DH, Sorrell TC, Allworth AM, Heath CH, McGregor AR, Papanaoum K, Richards MJ, Gottlieb T. Cryptococcal disease of the CNS in immunocompetent hosts: influence of cryptococcal variety on clinical manifestations and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(3):611–6.

Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28–34.

Chen SC-A, Slavin MA, Health CH, Playford EG, Byth K, Marriott D, Kidd SE, Bak N, Currie B, Hajkowicz K, Korman TM, McBride WJ, Meyer W, Murray R, Sorrell TC. Clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infection: determinants of neurological sequelae and death. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:789–98.

Ellis DH, Pfeiffer TJ. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28(7):1642–4.

Chong KY, Tan HTW, Corlett RT. A checklist of the total vascular plant flora of Singapore. Native, naturalized and cultivated species. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore 2009.

Taylor MB, Chadwick D, Barkham T. First reported isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from a patient in Singapore. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(8):3098–9.

Koh TH, Tan AL, Lo YL, Oh H. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii meningitis in Singapore. Med Mycol. 2002;40:221–3.

Lingegowda BP, Koh TH, Ong HS, Tan TT. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(7):e160–2.

Ho SW, Ang CL, Ding CS, Barkham T, Teoh LC. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Cryptococcus gattii. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44(12):E517–22.

Chan M, Lye D, Win MK, Chow A, Barkham T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of cryptococcosis in Singapore: predominance of Cryptococcus neoformans compared with Cryptococcus gattii. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:110–5.

Litvintseva AP, Thakur R, Reller LB, Mitchell TG. Prevalence of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus gattii serotype C among patients with AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:888–92.

Steele KT, Thakur R, Nthobatsang R, Steenhoff AP, Bisson GP. In-hospital mortality of HIV-infected cryptococcal meningitis patients with C. gattii and C. neoformans infection in Gaborone, Botswana. Med Mycol. 2010;48(8):1112–5.

Chen SC-A, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(4):980–1024.

Tay ST, Lim HC, Tajuddin TH, Rohani MY, Hamimah H, Thong KL. Determination of molecular types and genetic heterogeneity of Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii in Malaysia. Med Mycol. 2006;44(7):617–22.

Tay ST, Rohani MY, Soo Hoo TS, Hamimah H. Epidemiology of cryptococcosis in Malaysia. Mycosis. 2010;53(6):509–14.

Chen S, Sorrell T, Nimmo G, Speed B, Currie B, Ellis D, Marriott D, Pfeiffer T, Parr D, Byth K. Epidemiology and host- and variety-dependent characteristics of infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans in Australia and New Zealand. Australasian Cryptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):499–508.

Tseng HK, Liu CP, Ho MW, Lu PL, Ho HJ, Lin YH, Cho WL, Chen YV. Taiwanese Infectious Diseases Study Network for Cryptococcosis. Microbiological, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cryptococcosis in Taiwan, 1997–2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61921.

Flickinger FW, Sathyanarayana, White JE, Stincer EJ, Fincher RM. Cryptococcal pneumonia occurring as an infiltrative mass simulating carcinoma in an immunocompetent host: plain film, CT, and MRI findings. South Med J. 1993;86(4):450–2.

Purushotham MK, Chinaiah C, Lingaiha HM. Primary pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Cancer Investig J. 2015;4:365–7.

Zhang Y, Li N, Zhang Y, Li H, Chen X, Wang S, Zhang X, Zhang R, Xu J, Shi J, Yung RC. Clinical analysis of 76 patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(5):1191–200.

Piyavisetpat N, Chaowanapanja P. Radiographic manifestations of pulmonary cryptococcosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(11):1674–9.

Naik-Mathuria B, Roman-Pavajeau J, Leleux TM, Wall MJ. A 29-year-old immunocompetent man with meningitis and a large pulmonary mass. Chest. 2008;133:1030–3.

Igai H, Gotoh M, Yokomise H. Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography with [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG-PET) images of pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(6):837–9.

Huang CJ, You DL, Lee PI, Hsu LH, Liu CC, Shih CS, Shih CC, Tseng HC. Characteristics of integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT in pulmonary cryptococcosis. Acta Radiol. 2009;50(4):374–8.

Krockenberger MB, Malik R, Ngamskulrungroj P, Trilles L, Escandon P, Dowd S, Allen C, Himmelreich U, Canfield PJ, Sorrell TC, Meyer W. Pathogenesis of pulmonary Cryptococcus gattii infection: a rat model. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:315–30.

Ngamskulrungroj P, Chang Y, Sionov E, Kwon-Chung KJ. The primary target organ of Cryptococcus gattii is different from that of Cryptococcus neoformans in a murine model. MBio. 2012;3(3):e00103–12.

Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Debess E, Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Wohrle R, Lee S, Smelser C, Park B, Chiller T. Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: clinical aspects of infection with an emerging pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1185–95.

Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Sondermeyer G, Vugia DJ, Crist MB, D’Angelo MT, Sellers B, Franco-Paredes C, Makvandi M, Smelser C, Greene J, Stanek D, Signs K, Nett RJ, Chiller T, Park BJ. Cryptococcus gattii infections in multiple states outside the US Pacific Northwest. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(10):1620–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Ong Tan Ching from the Research Office of Nanyang Technological University for helping us with the identification of pollen grains and fungal spores. We would also like to thank Dr. Tan Ai Ling, Ms. Tan Mei Gie, and Ms. Delphine Cao from the Department of Microbiology, Singapore General Hospital, for assisting us in the MLST analysis of the C. gattii isolate. Last but not least, we are grateful to the Medical Publication Support Unit, National University Health System, for their publication support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, S., Tan, T.T. & Chien, J.M.F. Cryptococcus gattii Infection Presenting as an Aggressive Lung Mass. Mycopathologia 183, 597–602 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-017-0233-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-017-0233-6