Abstract

Although it is well-established that an objectively deserved misfortune promotes schadenfreude about the misfortune, there is a small body of research suggesting that an undeserved misfortune can also enhance schadenfreude. The aim of the present study was to investigate the processes that underlie schadenfreude about an undeserved misfortune. Participants (N = 61) were asked to respond to a scenario in which a person was responsible or not responsible for a negative action. In the responsible condition, two independent routes to schadenfreude were observed: deservingness of the misfortune (traditional route) and resentment towards the target. More importantly, results showed that when the target of the misfortune was not responsible for the negative action, the relationship between schadenfreude and resentment towards the target was mediated by the re-construal of an objectively undeserved misfortune as a ‘deserved’ misfortune. The study further found that expressing schadenfreude about another’s misfortune makes one feel better about oneself without affecting moral emotions. The findings expand our understanding of schadenfreude about undeserved negative outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The purpose of the present research is to investigate psychological processes that underlie schadenfreude about an undeserved negative outcome or misfortune. Schadenfreude is an emotion that involves expressing pleasure about another person’s misfortune. There is ample research showing that an objectively deserved misfortune can boost schadenfreude about the misfortune (e.g., Feather 2014; van Dijk and Ouwerkerk 2014). More surprising, there is also a small body of research suggesting that an undeserved misfortune can lead to schadenfreude (Brigham et al. 1997; van de Ven et al. 2015; van Dijk et al. 2015). The present study examines the pathways for both deserved and undeserved misfortunes to schadenfreude. In particular, we propose that when a misfortune is objectively undeserved, a person may re-construe it as deserved due to feelings of resentment. It is this re-construed deservingness that then promotes schadenfreude about the misfortune.

Responsibility, deservingness, and schadenfreude

According to Feather (1999), perceived deservingness of a positive or negative outcome occurs when a person is fully or partly responsible for a positive or negative (respectively) action (see also Portmann 2000). In other words, the action and the outcome are contingent (Heider 1958). For example, when a person is perceived to be responsible for a negative action, the negative outcome is appraised as deserved. The appraisal of deservingness evokes schadenfreude about the negative outcome or misfortune (e.g., Feather 2014; van Dijk and Ouwerkerk 2014). For example, when a student has not studied for an exam and subsequently failed, the failure is perceived as deserved and may elicit schadenfreude in fellow students. Such schadenfreude can be understood as a ‘morally’ right emotion because it involves an element of justice or fairness.

In addition, Brigham et al. (1997), van de Ven et al. (2015), and van Dijk et al. (2015) demonstrated that an individual’s feelings towards the target can amplify schadenfreude due to malicious envy (aiming to pull down the superior person). These results are in line with an earlier suggestion by Lupfer and Gingrich (1999) who showed that schadenfreude can be evoked by perceived characteristics of the person (e.g., superiority). Recently, Brambilla and Riva (2017) showed that a person who lacked morality fostered more schadenfreude following a misfortune than a non-sociable person. Thus, in addition to schadenfreude that is based on responsibility for negative action (e.g., Feather 2014), schadenfreude can also be based on attributes of an individual.

Regarding schadenfreude about an undeserved negative outcome, imagine the following situation. Your neighbour is a friendly person. He is very rich and donates large amounts of money to charity organisations such as disability and health services. Recently, he has bought a brand new hybrid car which is exactly the one you would like to have but cannot afford. Yesterday, a drunken driver smashed up your neighbour’s car and you felt schadenfreude about it. How might people deal with such joy about an undeserved negative outcome without perceiving themselves as a malicious person?

One possibility is that people may reason that the other person ‘deserves’ the misfortune in some way, even though the person is not responsible for the negative action that leads to the misfortune. We argue here that an objectively undeserved misfortune can be re-construed as a deserved misfortune based on subjective feelings. Accordingly, this perceived deservingness serves as a justification or alibi for the occurrence of the misfortune that makes it easier to express schadenfreude. Such re-construed deservingness differs from objective deservingness because it is not based on perceptions of responsibility for a negative action (see Feather 2014). However, both types of deservingness can lead to schadenfreude.

Resentment

The current study focuses on resentment as a source for evoking schadenfreude. Resentment is an emotion that is characterized by bitter indignation about another person’s behavior that is perceived as harmful for oneself (e.g., Ben Ze’ev 2000; La Caza 2001). Feather and Sherman (2002) found that when a student did not study for an exam but was successful, this induced resentment in other students which, in turn, elicited schadenfreude when the student subsequently failed at an exam. Unlike Feather and Sherman (2002), we manipulate responsibility in the current study. When the target is responsible for a negative action, we expect that, in addition to the perceived deservingness of a misfortune that will evoke schadenfreude (Feather 2014), resentment towards the target will also evoke schadenfreude about a subsequent misfortune (Feather and Sherman 2002).

Importantly, when the target is not responsible for the negative action, we propose a different pathway to schadenfreude. In this case, resentment can lead a person to re-construe an objectively undeserved negative outcome as deserved which then amplifies schadenfreude. That is, greater resentment will be associated with more re-construed deservingness of the misfortune that, in turn, will be associated with more schadenfreude. Thus, we expect an indirect path from resentment to schadenfreude through re-construed deservingness of the misfortune. This re-construed deservingness of the misfortune then serves as justification for expressing schadenfreude.

Thus we propose different routes to schadenfreude as a function of responsibility for a negative action (see Fig. 1). When the target is responsible for the negative action, the misfortune will be perceived as deserved which will be positively associated with schadenfreude. In this situation, resentment towards the target will also be directly and positively associated with schadenfreude when the target receives a subsequent misfortune. These two routes represent independent pathways to schadenfreude (see Fig. 1a). However, when the target is not responsible for the negative action, resentment towards the target will be associated with schadenfreude about the target’s subsequent misfortune through re-construed deservingness of the misfortune (see Fig. 1b). Thus the present research fills a gap in the literature on schadenfreude by examining different potential pathways to schadenfreude as a function of perceived responsibility for negative actions.

How does expressing schadenfreude make you feel?

The historian Peter Gray reported that he had felt schadenfreude when, as a Jewish child, he saw that the Germans had to provide other countries with gold medals in the Olympic Games in 1936. He said that schadenfreude “can be one of the great joys of life” (Rothstein 2000). The felt schadenfreude obviously made him feel better.

While low self-esteem has been found to be a predictor of schadenfreude (e.g., van Dijk et al. 2011), the more general question as to whether people express schadenfreude because it makes them feel good about themselves is hardly addressed in the present literature on schadenfreude. Notable exceptions are found in the work of Leach and Spears (2009) and Brambilla and Riva (in press). Based on Heider’s (1958) argument that expressing schadenfreude can affirm the self, Leach and Spears (2009) found that schadenfreude about another team’s loss was linked with a positive evaluation of the in-group who had previously been defeated by that team. Brambilla and Riva (2017) showed that expressing schadenfreude boosts satisfaction of basic psychological needs in terms of self-esteem, control, belongingness, and meaningful existence. These effects occurred particularly in competitive contexts, such as job interviews (Brambilla and Riva 2017) and sports matches (Leach and Spears 2009). A different kind of evidence that expressing schadenfreude enhances self-evaluation is found in fMRI studies showing that schadenfreude is related to stronger ventral striatum activity that represents rewarding reactions (Cikara et al. 2011; Singer et al. 2006; Takahashi et al. 2009). It is therefore hypothesized that schadenfreude promotes a positive self-evaluation. In contrast to previous research (Brambilla and Riva in press; Leach and Spears 2009), the present study uses direct questions about the effect of schadenfreude on self-evaluations, such as “expressing pleasure about the other’s misfortune makes me feel better”.

On the other hand, it is also possible that expressing schadenfreude may make people feel bad. For example, Berndsen and Feather (2016) found that participants felt negative moral emotions (guilt, shame, regret) about their expressed schadenfreude when they were informed about the serious consequences of the misfortune (see also Hoogland et al. 2015). However, Kristjánsson (2006) asserts that schadenfreude for an undeserved misfortune occurs without moral concern. It is therefore investigated whether respondents will experience such moral emotions about their expressed schadenfreude.

The present study

The aim of the present study is three-fold. First, in line with the findings of Brigham et al. (1997) and van de Ven et al. (2015), we investigated whether an objectively undeserved misfortune can elicit schadenfreude. We predicted that in our situation where the target of schadenfreude is not responsible for a negative action, but receives a negative outcome, schadenfreude would be invoked in the observer.

Second, we examined the processes underlying schadenfreude. In particular, we focus on deservingness and resentment as a function of perceived responsibility for a negative action. We developed the following moderated mediation hypothesis. When the target is responsible for the negative outcome and receives a misfortune, we predicted that perceived deservingness of the misfortune would promote schadenfreude. We also predicted that evoked resentment would be positively associated with schadenfreude about the subsequent misfortune in this situation. Thus in the responsibility condition, we expected two pathways to schadenfreude: one from deservingness and the other from resentment. We also propose another route to schadenfreude. When the target is not responsible for the negative action but receives an undeserved misfortune, we predicted that resentment towards the target would lead to re-construal of the undeserved misfortune as a deserved misfortune that then would lead to schadenfreude about a subsequent misfortune. In other words, the relationship between resentment and schadenfreude would be mediated by re-construed deservingness of the misfortune.

The third aim was to examine how people feel about their expression of schadenfreude. Specifically, we predicted that schadenfreude would be positively associated with self-evaluation. Moreover, following Kristjánsson (2006), when the target is not responsible for the negative action but gets an undeserved misfortune, we expected that the expression of schadenfreude would not be associated with moral emotions.

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 61 first year psychology students (88% female; M age = 22.85, SD age = 8.00) from an Australian University. The study used a 2-group (responsibility: no, yes) between-subjects design. Participants accessed the questionnaire online by clicking on a link in the study advertisement and were randomly allocated to one of the two experimental conditions.

Stimulus materials and procedure

The scenario concerned two siblings. Participants were instructed to imagine being the younger sibling. They read that the older sibling (who could be either a sister or brother) was watching television and yelled at the younger one who tried to have a conversation, a scene intended to develop resentment in the younger sibling towards the older one. Next, the manipulation of responsibility followed whereby either the older sibling or the younger sibling accidently knocked over a glass with juice. The mother assumed that the older sibling had made the mess and, as punishment, sent him/her to the bedroom.

Thus the situation in which the older sibling knocks over the glass and is subsequently punished by the mother represents a deserved misfortune. The situation in which the younger sibling knocks over the glass and the older one is punished by the mother represents an undeserved misfortune. The punishment (being sent to the bedroom) was deliberately chosen to be not a very severe punishment, as previous research has shown that severe negative outcomes attenuate schadenfreude (e.g., Combs et al. 2009; Hareli and Weiner 2002).

Dependent measures Footnote 1

All responses below were measured on 7-point Likert scales anchored 1 (not at all) and 7 (very much).

Manipulation check

The manipulation check for responsibility was assessed with: “How responsible was your sister/brother for getting the punishment”. This item was placed at the end of the questionnaire in order to avoid suspicion.

Deservingness

Three items, adapted from Feather and McKee (2014) measured (construed) deservingness of the outcome: “How much did your sister/brother deserve your mother’s punishment?” “How fair [justifiable] did you find the punishment?” (α = 0.90).

Resentment

Two items, adapted from Feather, McKee and Bekker (2011) were used to measure resentment. “How resentful [indignant] did you feel towards your sister/brother?” (r =. 81, p < .001).

Schadenfreude

Three items, adapted from Feather and Sherman (2002), measured schadenfreude: “How pleased did you feel about your sister/brother’s punishment””, “How amused did you feel [How much did you enjoy it] when your sister/brother was punished?” (α = 0.91).

Schadenfreude-related self-evaluation

Four items assessed participants’ self-evaluation in relation to the schadenfreude expressed: “Expressing pleasure about the punishment of my sister/brother makes me feel better [stronger, pleased with myself, confident about myself]”, α = 0.96.

Schadenfreude-related moral emotions

Three items measured moral emotions in relation to the schadenfreude expressed, “How much guilt [shame, regret] do you now feel about your pleasure in the punishment of your sister/brother?”, α = 0.96.

Results

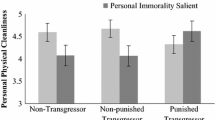

Scale inter-correlations and descriptive statistics for all dependent variables are shown in Table 1. As expected, both resentment and perceived deservingness were significantly and positively correlated with schadenfreude. The means and standard deviations for each variable as a function of responsibility condition are presented in Table 2.

Manipulation check

A t-test (responsibility of older sibling: yes, no) was used to test the responsibility manipulation check. Perceived responsibility was significantly higher in the responsible condition than in the non-responsible condition (see Table 2). Thus the manipulation of responsibility was successful.

Comparison between conditions

A series of t-tests (responsibility of older sibling: yes, no) was performed. Table 2 shows that perceived deservingness of the punishment was significantly higher when the older sibling was responsible for knocking over the juice than when he/she was not responsible. Conversely, resentment towards the older sibling was significantly higher in the non-responsible condition than in the responsible condition.

For schadenfreude, importantly, there was no significant difference between the responsibility conditions (see Table 2). The absence of a significant main effect of responsibility indicates that responsibility for a negative action is not a necessary requirement for the occurrence of schadenfreude.

Moderated mediation analysis

We used AMOS 22 to test our moderated mediation hypothesis that responsibility condition would moderate the effects on schadenfreude through resentment and deservingness. Consistent with Fig. 1a, we expected that the path between resentment and schadenfreude would be stronger in the responsible condition than in the non-responsible condition. Conversely, consistent with Fig. 1b, we expected that the path between resentment and deservingness would be stronger in the non-responsible condition than in the responsible condition. To test these moderation effects, we conducted multi-group structural equation modelling (SEM) with responsibility condition as the grouping variable (i.e., as the moderator). Multi-group SEM allows us to compare parameters in different groups. In Model 1, all structural relations between the responsibility conditions were constrained to be equal. In Model 2, the two paths: (i) from resentment to deservingness and (ii) from resentment to schadenfreude were left unconstrained. The difference between the models (Model 1 χ 2(3) = 6.78, p = .79; Model 2 χ 2(1) = 0.42, p = .519) was statistically significant, ∆χ 2(2) = 6.36, p = .042, indicating that the less constrained model (where the parameters were free to vary) provided a better overall model fit. This demonstrates moderation by responsibility condition on the different pathways to schadenfreude.

The overall model fit for the less constrained model was excellent (see Kline 1998): χ 2(1) = 0.42, p = .519, χ 2/df ratio = .42, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .00. Figure 2 displays the resulting standardized regression weights; values to the left of the backslash refer to the responsible condition and values to the right of the backslash refer to the non-responsible condition. Support for the specified moderated mediation hypothesis was found. As can be seen in Fig. 2, in the responsible condition the paths between deservingness and schadenfreude, as well as between resentment and schadenfreude, were positive and significant, indicating independent effects. In contrast, the path from resentment to deservingness was not significant. Formal testing showed no significant indirect effect from resentment to schadenfreude through deservingness, B = 0.09, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [− 0.01, 0.23].

In the non-responsibility condition, the paths from resentment to deservingness and from deservingness to schadenfreude were positive and significant, whereas the path from resentment to schadenfreude was not significant (see Fig. 2). Formal testing showed that the indirect effect from resentment to schadenfreude through deservingness was significant, B = 0.12, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.23], providing excellent support for the model.

Consequences of expressing schadenfreude

Table 1 shows that schadenfreude correlated significantly and positively with self-evaluation, as predicted. This was the case in both the responsible condition, r = .38, p = .039, and the non-responsible condition, r = .47, p = .007. Further, the conditions did not significantly differ in the ratings of self-evaluation (see Table 2).

Although moral emotions about the expressed schadenfreude were significantly higher in the non-responsible condition than in the responsible condition (Table 2), we predicted that schadenfreude would not be associated with moral emotions when the target was not responsible for the misfortune. Overall schadenfreude did not correlate significantly with the expression of moral emotions (see Table 1). This was particularly the case in the non-responsible condition, r = − .09, p = .646, consistent with our prediction. In the responsible condition, there was a marginally significant negative correlation between schadenfreude and moral emotions, r = − .34, p = .070, although the difference between the two responsibility conditions was not significant, Fisher’s z = 0.98, p = .327.

Discussion and conclusion

The main purpose of the current study was to investigate psychological processes that underlie schadenfreude about an undeserved misfortune. We found that such schadenfreude is predicted by resentment towards the target of the misfortune and the subsequent re-construal that the target deserves the misfortune. Support for the more traditional route to schadenfreude was also found: target responsibility for the negative action predicted schadenfreude through perceived deservingness of the misfortune. In this situation, schadenfreude about the misfortune was also predicted by resentment towards the target. Finally, the current study found support for the proposition that expressing schadenfreude about another’s misfortune makes one feel better about oneself without affecting moral emotions about expressing schadenfreude, especially when the target was not responsible for the negative action.

Our study contributes to the small body of research showing that an undeserved misfortune can lead to schadenfreude (Brigham et al. 1997; van de Ven et al. 2015; van Dijk et al. 2015). Our findings extend previous research in two ways. First, we manipulated responsibility for the negative action. Second, we examined the underlying mechanisms of how an objectively undeserved misfortune can give rise to schadenfreude. In so doing, we showed that when the target was not responsible for the negative action, resentment towards the target operated indirectly by facilitating the perception of an objectively undeserved misfortune as a deserved misfortune. Specifically, greater resentment was associated with more re-construed deservingness of the misfortune that, in turn, was associated with more schadenfreude. This set of findings is intriguing as it seems to indicate that an undeserved misfortune requires cognitive effort to justify schadenfreude about the misfortune.

When the target of the misfortune was responsible for the negative action there were two independent pathways to schadenfreude about the target’s misfortune: from perceived deservingness of the subsequent misfortune and from resentment towards the target. The observed effect of resentment on schadenfreude is consistent with some previous research (Feather and Sherman 2002). More generally, it is consistent with research showing that schadenfreude can be amplified due to particular feelings, including dislike (Hareli and Weiner 2002; Hoogland et al. 2015), felt inferiority (Leach and Spears 2008), and envy (van de Ven 2014).

Re-construing an undeserved misfortune as a deserved misfortune is a novel finding with important theoretical implications. Just as responsibility for a negative action is not a necessary element for the expression of schadenfreude (Brigham et al. 1997; van de Ven et al. 2015; current study), responsibility is also not a necessary requirement for the attribution of deservingness; an undeserved negative outcome for which an individual is clearly not responsible can be re-construed as deserved. Thus, although perceived deservingness can be based on justice motives (e.g., Feather 2014; van Dijk and Ouwerkerk 2014), perceived deservingness can also be based on feelings towards the target of the misfortune, and such re-construed deservingness may subsequently serve as justification for expressing schadenfreude.

A further contribution of the current study is the finding that expressing schadenfreude leads to feeling better about oneself. This was the case in both responsibility conditions. The finding is consistent with the argument that expressing schadenfreude can affirm the self (Heider 1958), restore a sense of equality with the target of schadenfreude (Kristjánsson 2006), or restore subjective justice (Smith et al. 2009). Specifically, in our study the younger sibling may have felt “put down” due to the older sibling’s yelling. By expressing schadenfreude about the older sibling’s punishment, the younger sibling’s feeling of equality and subjective justice would have been restored. Moreover, our finding that expressing schadenfreude leads to feeling better about oneself is consistent with those of Brambilla and Riva (2017) and Leach and Spears (2009). Our study extends their research by demonstrating that positive feelings about expressing schadenfreude also occur in a non-competitive context. In addition, we asked participants directly how they felt about their expressed schadenfreude. Notwithstanding that different results might be found with a more severe misfortune, the observed positive self-evaluations challenge a commonly held assumption that people want to hide their schadenfreude as it is typically perceived as a socially undesirable emotion (e.g., Portmann 2000; Spurgin 2015; Takahashi et al. 2009; van de Ven 2014).

We also found that expressing schadenfreude did not affect the moral emotions of guilt, shame, and regret about expressing such schadenfreude in the non-responsible condition. This finding is of particular note because it supports Kristjánsson’s (2006) claim that an undeserved misfortune evokes schadenfreude without any moral concerns about the expression of schadenfreude. Hence the study extends our knowledge about the affective consequences (positive self-evaluation and lack of moral concern) of expressing schadenfreude. In our study we deliberately chose a minor punishment (sending the older sibling to the bedroom). However, it is possible that a more severe undeserved misfortune might elicit moral concerns about the expressed schadenfreude and/or attenuate positive self-evaluations about such expression, a possibility that future research might address.

Our findings need to be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, we used a hypothetical scenario. Hypothetical scenarios are often used in research on schadenfreude (e.g., Brambilla and Riva 2017; Feather and Sherman 2002; Powell and Smith 2013; van Dijk et al. 2015) because it is easier to control for extraneous factors and because scenarios are less intrusive and ethically problematic than real life situations. Moreover, Robinson and Clore (2001) have demonstrated that vignette methods of emotion elicitation generate results that are similar to ‘in vivo’ methods. We nevertheless recognize the possibility that real life events might induce a more powerful sense of experienced schadenfreude. Second, in our study the younger sibling knocked over the glass containing juice. Further research might usefully investigate the situation in which a third party is responsible for the negative action.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, the present study contributes to our understanding of the psychological processes underlying schadenfreude about undeserved negative outcomes. Specifically, we showed that resentment acts indirectly by shifting the meaning of a clearly undeserved misfortune into a deserved one that subsequently evokes schadenfreude.

Notes

There were more variables included in the study than reported here, in particular, inferiority and compassion. We have not included these variables as they are peripheral to our major research question.

References

Ben-Ze’ev, A. (2000). The subtlety of emotions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Berndsen, M., & Feather, N. T. (2016). Reflecting on schadenfreude: serious consequences of a misfortune for which one is not responsible diminish previously expressed schadenfreude; the role of immorality appraisals and moral emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 40, 895–913.

Brambilla, M., & Riva, P. (2017). Predicting pleasure at others’ misfortune: Morality trumps sociability and competence in driving deservingness and schadenfreude. Motivation and Emotion, 41, 243–253.

Brambilla, M., & Riva, P. (2017). Self-image and schadenfreude: Pleasure at others’ misfortune enhances satisfaction of basic human needs. European Journal of Social Psychology. Retrieved 16 August, 2017 from onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejsp.2229/PDF.

Brigham, N. L., Kelso, K. A., Jackson, M. A., & Smith, R. H. (1997). The roles of invidious comparisons and deservingness in sympathy and schadenfreude. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19, 363–380.

Cikara, M., Botvinick, M. M., & Fiske, S. T. (2011). Us versus them: social identity shapes neural responses to intergroup competition and harm. Psychological Science, 22, 306–313.

Combs, D. J. Y., Powell, C. A. J., Schurtz, D. R., & Smith, R. H. (2009). Politics, schadenfreude, and ingroup identification: the sometimes happy thing about a poor economy and death. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 45, 635–646.

Feather, N. T. (1999). Values, achievement, and justice. In Studies in the psychology of deservingness. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Feather, N. T., (2014). Deservingness and schadenfreude. In van Dijk, W.W., & J. W. Ouwerkerk (Eds.), Schadenfreude: Understanding pleasure at the misfortune of others (pp. 29–57).

Feather, N. T., & McKee, I. R. (2014). Deservingness, liking relations, schadenfreude and discrete emotions in the context of the outcomes of plagiarism. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 18–27.

Feather, N. T., McKee, I. R., & Bekker, N. (2011). Deservingness and emotions: Testing a structural model that relates discrete emotions to the perceived deservingness of positive or negative outcomes. Motivation and Emotion, 35, 1–13.

Feather, N. T., & Sherman, R. (2002). Envy, resentment, schadenfreude, and sympathy: Reactions to deserved and undeserved achievement and subsequent failure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 953–961.

Hareli, S., & Weiner, B. (2002). Dislike and envy as antecedents of pleasure at another’s misfortune. Motivation and Emotion, 257–277.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: J. Wiley.

Hoogland, C., Shurtz, D. R., Cooper, C. M., Combs, D. J. Y., Brown, E. G., & Smith, R. H. (2015). The joy of pain and the pain of joy: In-group identification predicts schadenfreude and gluckschmerz following rival groups’ fortunes. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 260–281.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kristjánsson, K. (2006). Justice and desert-based emotions. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

La Caza, M. (2001). Envy and resentment. Philosophical Explorations, 4, 31–45.

Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2008). ‘A vengefulness of the impotent’: The pain of in-group inferiority and schadenfreude toward successful out-groups’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1383–1396.

Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2009). Dejection at in-group defeat and schadenfreude toward second- and third-party out-groups. Emotion, 9, 659–665.

Lupfer, M. B., & Gingrich, B. E. (1999). When bad (good) things happen to good (bad) people: The impact of character appraisal and perceived controllability on judgments of deservingness. Social Justice Research, 12, 165–188.

Portmann, J. (2000). When bad things happen to other people. New York: Routledge.

Powell, C. A., & Smith, R. H. (2013). Schadenfreude caused by the exposure of hypocrisy in others. Self and Identity, 12, 413–431.

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: Testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1520–1532.

Rothstein, E. (2000). Shelf-life; missing the fun of a minor sin. Retrieved 4 December, 2016 from http://www.nytimes.com/2000/02/05/books/shelf-life-missing-the-fun-of-a-minor-sin.html.

Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J. P., Stephan, K. E., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2006). Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature, 439, 466–469.

Smith, R. H., Powell, C. A., Combs, D. J. Y., & Schurtz, D. R. (2009). Exploring the when and why of schadenfreude. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3, 530–546.

Spurgin, E. (2015). An emotional-freedom defense of schadenfreude. Ethical Theory and Modern Practice, 18, 767–784.

Takahashi, H., Matsuura, Kato. M., Mobbs, M., Suhara, D. T., & Okubo, Y. (2009). When your gain is my pain and your pain is my gain: neural correlates of envy and Schadenfreude. Science, 323, 937–939.

van de Ven, N. (2014). Malicious envy and schadenfreude. In W. W. van Dijk & J. W. Ouwerkerk (Eds.), Schadenfreude: Understanding pleasure at the misfortune of others. (pp. 110–118). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van de Ven, N., Hoogland, C. E., Smith, R. H., van Dijk, W. W., Breugelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2015). When envy leads to schadenfreude. Cognition and Emotion, 29, 1007–1025.

van Dijk, W. W., & Ouwerkerk, J. W. (2014). Striving for positive self-evaluation as a motive for schadenfreude. In W. W. van Dijk & J. W. Ouwerkerk (Eds.), Schadenfreude: Understanding pleasure at the misfortune of others. (pp. 131–148). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Dijk, W. W., Ouwerkerk, J. W., Smith, R. H., & Cikara, M. (2015). The role of self-evaluation and envy in schadenfreude. European Review of Social Psychology, 26, 247–282.

van Dijk, W. W., Ouwerkerk, J. W., Wesseling, Y. M., & van Koningsbruggen, G. M. (2011). Towards understanding pleasure at the misfortunes of others: The impact of self-evaluation threat on schadenfreude. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 360–368.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berndsen, M., Tiggemann, M. & Chapman, S. “It wasn’t your fault, but …...”: Schadenfreude about an undeserved misfortune. Motiv Emot 41, 741–748 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9639-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9639-1