Abstract

This paper argues that enthusiasm for empathy has grown to the point at which empathy has taken on the status of an “ideal” in modern medicine. We need to pause and scrutinize this ideal before moving forward with empathy training programs for medical students. Taking empathy as an ideal obscures the distinction between the multiple aims that calls for empathy seek to achieve. While these aims may work together, they also come apart and yield different recommendations about the sort of behavior physicians should cultivate in a given situation. I begin by demonstrating how enthusiasm for empathy has increased dramatically. I then specify precisely what I mean in calling empathy an “ideal.” I then describe some dangers associated with taking empathy to be an ideal unreflectively. I discuss the merits of works that provide conceptualizations of empathy that are specifically tailored for the medical domain and conclude that although these works move discussions about empathy in medical care forward, they could do more to foreground the goals and aims underlying calls for increased empathy. I provide specific suggestions as to how exactly we might foreground these goals and aims to further avoid conceptual confusion about empathy in medical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Empathy is widely considered to be important in modern medicine. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), in its report on learning objectives for medical schools, states: “Physicians must be compassionate and empathetic in caring for their patients” (1998, p. 4). In the UK, the General Medical Council (GMC) points to the importance of empathy in several of its advanced training skills modules (e.g., “Menopause,” 2007a; “Sexual Health,” 2007b).Footnote 1 The Cambridge-Calgary guide to the medical interview, which is used widely in UK medical training, likewise lists empathy as an objective. The objective reads as follows: “Uses empathy to communicate understanding and appreciation of the patient’s feelings or predicament; overtly acknowledges patient’s views and feelings” (Kurtz et al. 1998; Silverman et al. 2013, p. 23). Superlative statements about the value of empathy can also be found at the start of many articles on medical education and medical ethics. Accompanying these statements about the importance of empathy, there exists a large body of literature that debates whether empathy can be taught and how best to do so. This body of literature often draws on findings from neuroscience and various areas of empirical psychology to develop empathy training techniques. Despite this enthusiasm for empathy, few people ask the following important questions: What exactly do physicians mean by empathy? What precisely does empathy do and should it be so central to medicine? These are the questions that I intend to address in this paper.

The largely unreflective trend toward empathy enthusiasm is not unique to medicine. It is widespread across the helping professions—including clinical psychology, counseling, social work, and teaching—as well as in Western society more generally. Superlative statements about the importance of empathy are ubiquitous in large swathes of academic and popular writing today. For example, in the literature on social work, Gerdes et al. (2011), write: “Lack of empathy underlies the worst things human beings can do to one another; high empathy underlies the best. Social work can almost be seen as an organized manifestation of empathy—to such an extent that social work educators and practitioners sometimes take it for granted” (p. 109). Outside of medicine, former president Barack Obama has made numerous calls for increased empathy. For example, in a 2006 speech to graduating university students, he said that America is suffering from an “empathy deficit” and that we need to “broaden, and not contract, our ambit of concern.” Enthusiasm for medical empathy, and the calls for empathy training programs, can be seen as part of a larger trend.

There has recently been a backlash against this trend, especially from philosophers and psychologists, such as Prinz (2011a, b) and Bloom (2014, 2016, 2017a, b), who bill themselves as “against empathy.” These anti-empathy theorists mainly focus on the issue of empathy and morality, and tend to argue that empathy is not necessary, or even important, for moral development, conduct, or behavior. While these the writers are mainly interested in empathy and moral cognition, they have begun to make forays into the context of medicine. Bloom (2016) uses recent evidence from neuroscience to draw a distinction between empathy and compassion, and then goes on to argue that it is compassion and not empathy that medical practitioners need (see also Jordan et al. 2016). My argument is consistent with what Bloom says in his book, although my approach is somewhat different; I focus on foregrounding the specific aims that empathy plays in medicine.

I begin by providing evidence of the widespread and often unreflective enthusiasm for empathy present in medicine. This evidence shows that regardless of whether empathy should be taken as a central attribute of a good doctor, it is often touted as one. I then use the seminal work of Linda and Ezekiel Emanuel to situate discussions of medical empathy within larger debates about medical ethics, autonomy, and the doctor–patient relationship, and show that empathy has taken on the features of an “ideal.” I point out that medicine has not always embraced the empathic ideal; the norms of medicine, and more specifically norms surrounding the role of the emotions in medical communication, have shifted greatly, even over the course of the twentieth century. I then make the case that unreflectively taking empathy to be an ideal, as often happens in current medical practice, carries dangers that must be addressed. Most importantly, I argue that taking empathy to be an ideal obscures the multiplicity of aims it might have in medical practice. Among these multiple aims, I draw an important distinction between two overarching categories: (1) the “Epistemic” aims of empathy—which include facilitating communication, increasing patient understanding, and aiding in decision making; and (2) the “Customer Service” aims of empathy—which include creating a courteous and pleasant environment. While these two kinds of aim may support each other in some cases, they are importantly different and often come apart. Furthermore, these aims stand in contrast to a third category of empathy concepts, which I will call “purely emotional.” These “purely emotional” forms of empathy are often studied in discussions of empathy outside of medicine—in social psychological studies where the aim is to increase prosocial behavior in particular. This discontinuity means that measures of empathy and training techniques from social psychology and other fields cannot always be easily adapted for the medical context. Crucially, I argue that it is the “epistemic” aims—and associated epistemic forms or concepts of empathy—that should occupy a central place in medicine. Other forms of empathy may even have a detrimental impact within medical practice. In summary, I argue that attending to the different aims that empathy seeks to achieve in medicine—instead of making blanket calls for empathy—will allow us to make more specific claims about the appropriate physician behavior for a given situation and in turn help physicians to better tailor their responses to individual contexts. Pragmatically, I suggest splitting the “epistemic” concepts, which are most effective within medicine, off from other concepts of empathy. This has important consequences both for medical training and for discussions of the doctor–patient relationship, autonomy, and decision-making in medical ethics.

Within this paper, I limit myself to consideration of medicine at the exclusion of other “helping professions.” Although the clinical psychological, social work, and counseling domains might have much in common with medicine, they are sufficiently culturally different, with different historical relations to concepts of empathy, that they are worth treating independently. Finally, I focus here on the US and UK medical contexts, although empathy enthusiasm has arguably spread to other areas of the world.

Empathy enthusiasm and the formation of the empathic “ideal”

There is no doubt that enthusiasm for empathy has grown within the last several years. I began this paper by citing formal recommendations from medical associations in the US and in the UK. But enthusiasm for empathy goes beyond these formal recommendations and is especially widespread within the literature on medical education. For example, Ronda Henry-Tillman and colleagues (2002) write: “An understanding of empathy is important to the development of medical students. Empathy enables the physician to understand a patient’s beliefs and emotions and thereby provide compassionate care” (p. 559). Shapiro et al. (2004) write: “Empathy is critical to the development of professionalism in medical students” (p. 73). We can see from these quotations that authors often credit empathy with both the ability to act professionally and to gain understanding of their patients.

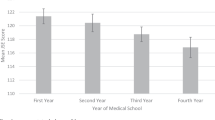

Concern over medical student empathy skyrocketed in the wake of a highly publicized finding that empathy declines over the course of medical education (Hojat et al. 2009; Neumann et al. 2011; Newton et al. 2000, 2008). Bruce Newton and his colleagues found that empathy is lower in the fourth year of medical school than in the third year for men, but interestingly, not for women; empathy scores remain fairly constant for women across the years of medical education. They also found that empathy is lower for students choosing “non-core” specialties, regardless of gender. “Core” specialties correspond roughly to what have, in more recent investigations, been called “person-centered specialties” and include family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry (Chen et al. 2007). “Non-core” specialties correspond roughly to what have been called “technology-oriented” specialties in more recent literature and include radiology, surgery, and anesthesiology. This latter finding—that empathy scores are lower among those choosing non-core specialties—has been fairly stable. The demonstration of decline, however, was alarming to senior medical practitioners.

Since this initial finding, much work has been done to untangle the claim that empathy declines over the course of medical education. Some authors argue that the decline in empathy has been greatly over-exaggerated (e.g., Colliver et al. 2010). Others argue that the decline is largely an artifact of the way that empathy has been measured and defined—more specifically, of the use of measurements that are not “content-specific to patient care” (Hojat et al. 2009). In other words, researchers find an empathy decline when they use certain measures but not others. As I will explain later in this paper, these different ways of defining and measuring empathy may track substantively different psychological capacities or phenomena. Empathy decline, as found in the initial studies, is therefore not as detrimental or alarming as it initially appears to be. Nonetheless, this finding generated substantial investment in efforts to teach empathy to medical students and fueled “empathy enthusiasm.” In current medical education systems, there are several techniques for teaching empathy, including workshops on interpersonal communication skills, lectures, spirituality and wellness courses, sessions with standardized patients, student hospitalization experiences, experiences shadowing or accompanying a patient during a clinic visit, reflective writing seminars, role play, literature or theatre courses, and attendance at literary or theatrical events, among other things (for helpful reviews, see Batt-Rawden et al. 2013; Stepien and Baernstein 2006). Empathy is, therefore, often taken to be a central feature of medical practice, which is also reflected in medical education.

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for empathy, there continues to be some skepticism about its centrality within medical practice. This skepticism is more difficult to find in the published literature on medical education. It appears more frequently in candid conversations amongst clinicians. Where it does appear in the published literature, it is often couched in terms of concerns about time constraints or about the tradeoffs between the technical and interpersonal elements of medicine—or the “art” and “science” of medicine. For example, in a review of Halpern’s book, which makes an impassioned appeal for empathy, Philip Berry expresses skepticism about the feasibility of this: “Is this really feasible, for the younger, developing doctors at whom this book is aimed?…This model of empathy depends on time, and on a limitless store of altruism…” (2001, p. 1373). This reveals that some clinicians view calls for empathy as more of a burden than anything else.

There is also some evidence that empathy training is not taken very seriously by medical students. In a recent paper, Michalec (2011) conducted interviews with students at a medical school in the United States to evaluate the impact of the preclinical curriculum on their humanitarian attributes, especially empathy. Overall, he found that there are significant voids in the formal curriculum surrounding the practice and discussion of empathy, which signals to the students that such social skills are less highly valued in medicine than technical skills. The interviews with students are especially revealing when it comes to understanding how the empathy and social care curriculum was received. The bulk of this curriculum took place in the first few weeks of medical school, in lectures and group discussions. When asked about this first week, one of the students, “Jake,” said, “Small groups started off at the start of the year as a super drag. Early on it was a lot of common sense, you know, be nice to people, be courteous. Really? Great! Thanks! Can I go home now?” (Michalec 2011, p. 124). Other students found this curriculum “pointless” and not very memorable. These reactions reveal that despite the widespread enthusiasm for empathy expressed publicly by clinicians, there are some real problems in motivating the teaching of it.

In summary, while we find that enthusiasm for empathy is dominant within the literature on medical practice and education, some have significant doubts about its centrality and importance. This paper demonstrates that this situation largely stems from lack of clarity about the meaning of the concept of empathy within medicine. I also provide some suggestions for better navigating this situation by clarifying the role of empathy in medicine. In the next sub-section, I situate enthusiasm for empathy within wider debate about the doctor–patient relationship, in particular by drawing on a highly influential paper in the medical humanities by Ezekiel and Linda Emanuel (1992).

Emanuel and Emanuel’s four models of the physician–patient relationship

Ezekiel and Linda Emanuel’s paper, “Four Models of the Physician–Patient Relationship” (1992), continues to frame debate about the doctor–patient relationship in the context of medical decision making and addresses important issues about autonomy in medical ethics. Emanuel and Emanuel (1992) characterize four ways of conceptualizing the doctor–patient relationship. The first is the paternalistic model, which sees the doctor in the role of authoritative decision-maker with little patient input. This model can be summed up as “doctor knows best.” The second is the informative model, in which the doctor is viewed as a provider of information and the patient is viewed as a decision-maker. This model is sometimes also called the consumer model because it envisions the doctor’s role as presenting the patient with a number of different options to choose from, much as a salesperson might; the patient is then responsible for selecting among them. The third is the interpretive model, in which the doctor helps the patient to elucidate her aims or values and then provides information to help the patient make an informed choice about which treatments might best fulfill those aims. This model sees the doctor’s role as akin to that of a counselor. The fourth is the deliberative model, which sees the doctor’s role as not only helping the patient to figure out what her values are, but also seeking to guide the patient in determining which health-related values are most worthy. This fourth model envisions the doctor’s role as that of a teacher or friend. As we can see, each of the four models envisions a different degree of patient autonomy as appropriate in the doctor–patient relationship, as well as a different take on the relationship between facts and values.

Emanuel and Emanuel weigh the four options and come out in favor of the deliberative model as the preferred one for most clinical situations. They argue that although the other models might be favorable under certain circumstances—for example, the paternalistic model is widely agreed to be the best in an emergency situation—the deliberative model best fits our society’s norms about autonomy and the balance between the information-giving and care-giving roles of the physician in general.

Emanuel and Emanuel importantly see the four models as “Weberian ideal types.” As they define these ideal types, “They may not describe any particular physician–patient interactions but highlight, free from complicating details, different visions of the essential characteristics of the physician–patient interaction. Consequently, they do not embody minimum ethical or legal standards, but rather constitute regulative ideals that are ‘higher than the law’ but not ‘above the law’” (2221). This definition encapsulates the main elements of what it means to be an “ideal”—the elements that I would like to highlight in arguing that empathy has taken on the status of such an ideal. Ideals, on this view, are values to be strived for; they are regulative or normative. They are also importantly removed from the details of specific cases and in this way have a quality of abstraction.

In the next sub-section, I will argue that empathy has these two qualities—(1) high valuation or normative status, and (2) distance from the specific details of concrete situations. This “empathic ideal,” as I have already noted, does not fit neatly within any of the four models of the doctor–patient relationship characterized by Emanuel and Emanuel. As an alternative model, it raises new questions about how to best conceptualize the doctor–patient relationship, especially regarding autonomy and epistemology. Recognizing that empathy is taken to be an ideal helps us to see how it functions within and structures the contemporary doctor–patient relationship. Importantly, however, my recognition that empathy is often taken to be an ideal does not constitute endorsement of it.

Establishing the ideal: high valuation and distance from situational detail

I have already gone some of the way in establishing that empathy is currently taken to be an ideal, by demonstrating that it is highly valued in medicine today. It is viewed as something that we should strive to cultivate or achieve. This high valuation can be seen in the objectives of medical education as stated by the professional bodies that I quoted in the first paragraph of the introduction as well as in the numerous papers that have come out on techniques for teaching empathy to medical students.

The second feature of an “ideal” is distance from situational detail, which we can also establish in the case of medical empathy. First, we can see this distance in the definitions of medical empathy themselves, of which there are many. These definitions are often stated in abstract or philosophical terms. For example, Shapiro and colleagues define empathy as “the capacity to participate deeply in another’s experience” (2004, p. 74). Mercer and Reynolds (2002) define clinical empathy as “an ability to: (a) understand the patient’s situation, perspective, and feelings (and their attached meanings); (b) to communicate that understanding and check its accuracy; and (c) to act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful (therapeutic) way (S9). I will discuss later the issues that surround discrepancies in the definitions—that they often target different capacities and may be incompatible with one another. For the moment, notice how abstract they are. It is difficult to figure out, from the definition alone, just how one might apply the ideas encapsulated in it to individual clinical situations. In short, it is hard to answer questions about how in practice to implement such empathic behavior. Another sign that empathy is detached from specific detail is that it is often bundled in with other fairly abstract and non-specific concepts such as professionalism, compassion, sympathy, and narrative medicine.

Distance from specific cases can sometimes be a good thing—especially insofar as it allows one to capture essential qualities of the doctor–patient relationship, as is the case for the Emanuel and Emanuel models. As we will see later, though, the lack of specificity has gone too far in the case of empathy and has led to vagueness both in the description and the application of the ideal.

Thus, on the basis of the criteria established above, it is clear that empathy can be considered a contemporary ideal of medicine. We can see both from the statements of professional societies, and from the recent efforts to train empathy, that it is highly valued in the field and taken as an objective to cultivate or strive for. We can also see that discussions of empathy are often abstract and removed from the details of specific cases. Should empathy hold such a central place in medical practice and education? As I will argue throughout the rest of the paper, there are several questions that have been masked by the tendency to take empathy as an ideal, but that must be addressed if we are to situate empathy—or empathy-related phenomena—properly within medical practice. Prior to this, however, I will note that empathy was not always taken as an “ideal” or as in any way central to medical practice. The norms of medical practice have shifted greatly over time and appreciating this allows us to see how our default position—the assumption that empathy is central—is a fairly recent one.

Shifting norms in the doctor–patient relationship

Empathy was not always taken to be central within medical practice. Although it is outside the scope of this paper to fully trace the origins of the concept of medical empathy, having some sense of the shifts in the norms of medicine that have occurred provides helpful background and context. It also allows us to situate discussions of empathy within the wider literature on the doctor–patient relationship and medical ethics. Throughout this section, I rely heavily on recent work by the medical ethicist Halpern (2001/2011) and the medical historian David Rothman (1991).

In the first edition of her book, From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice (2001), Jodi Halpern notes that at the time of writing, detached concern was still the norm of medical practice. “Detached concern” expresses the idea that physicians should avoid emotional involvement with their patients while at the same time retaining interest in patients and care for their well-being. It was meant to avoid the pitfalls of emotional identification and to promote scientific objectivity in medicine. By the time the second edition of her book came out, in 2011, this had changed: “During the decade since this book first came out, patients have increasingly asserted their need to be treated empathically. Many medical educators and professional groups want to respond” (Halpern 2001/2011, xi). Halpern’s statements illustrate that significant shifts in how we think about the doctor–patient relationship have occurred, even very recently—within the last 20 years or so.

According to Halpern (2001/2011), detached concern provided the dominant mode of interaction between physician and patient throughout much of the twentieth century. She associates the tradition of detached concern with William Osler, whose work on equanimity is canonical in the American medical tradition. There are several reasons why physicians defended an attitude of detached concern within medical practice, according to Halpern. They thought that detachment was necessary to allow physicians to perform painful procedures on their patients: How could the surgeon possibly get through a painful procedure while feeling his patient’s pain? Physicians also thought that detachment could protect them from burn-out. They could tune out the patient’s feelings to prevent themselves from becoming emotionally overwhelmed. Furthermore, physicians argued that they needed to remain detached to care for patients in a fair and impartial manner, not favoring one patient over another. This became increasingly important as physicians saw more patients and time became increasingly scarce within the medical encounter (Halpern 2001/2011). Halpern also notes that detached concern was once the central feature of medical training—citing Fox and Lief’s influential work, “Training for Detached Concern” (1963). Halpern even calls detached concern a “professional ideal.” Thus, at one point, emotional involvement was thought to be detrimental to the doctor–patient interaction. This stands in stark contrast to contemporary preoccupations with empathy insofar as empathy is typically taken to be largely about being emotionally engaged. While different authors who focus on empathy have different perspectives on the extent to which doctors should be emotionally involved with their patients, in all of these perspectives, emotions occupy an important role. In models centered around detached concern, emotional involvement is generally frowned upon.

David Rothman’s book, Strangers at the Bedside (1991), does not deal specifically with empathy but nonetheless allows us to see how these debates about empathy versus detached concern occurred alongside wider shifts in the relationship between doctor and patient and the restructuring of medical ethics. Rothman traces the processes through which doctors became increasingly distant from the communities that they served and locates World War II as a major turning point. Part of the story is about the shift from “family medicine” to institutionalized and specialized medicine. According to Rothman (1991), doctors in the early twentieth century and before were often well-known and well-respected members of a given community, often familiar to their patients both within the context of treatment and outside of it. Medical care often took place in the home and doctors frequently cared for multiple generations of a given family. The doctor therefore had intimate knowledge of a family’s history and living situation, which they brought to their practice. Furthermore, when patients did go to hospitals, these were often deeply rooted in the community; Catholic patients went to Catholic hospitals, Jewish people went to Jewish hospitals, and so on. This meant that even within an institutional context, people still felt understood. As doctors became increasingly specialized and hospitals served increasingly general populations, this began to create distance between the doctor and the patient. Perhaps increased calls for empathy emerged in part as a reaction to this increased distance.

Another part of the story that Rothman (1991) tells is technological and based in concerns about the ethics of human research. Prior to World War II there were no regulatory bodies such as internal review boards who evaluated the merits and ethics of a given research study. Researchers did not see informed consent as necessary. They viewed themselves as having their own informal code of ethics, one which turned out to be rather malleable in the face of wartime needs. As certain egregious human experiments—especially on the poor or mentally disabled—were exposed during and after the war, the wider public began to lose their trust in researchers. This lack of trust expanded to doctors as well; the distinctions between the two were often not clear cut, as human experimentation often occurred within hospital settings in which patients were under the impression they were receiving standard treatments. This loss of trust was compounded by the increased distance between doctors and patients as medicine became increasingly institutionalized. Ultimately, these multiple factors triggered a massive shift in the way that medical ethics was practiced. Responsibility for making ethical judgments was increasingly taken out of the hands of doctors and given to “outsiders”—patients, families, philosophers, and lawyers. Alongside this shift, informed consent became a crucial part of the process of conducting research on humans. Patients and their families were given more decision-making power—more autonomy. This in turn shifted the way in which doctors and patients communicated. Calls for empathy, as I will illustrate later in this paper, are closely tied in with these discussions of communication in the medical setting.

Both Rothman and Halpern provide more detail about how the shifts in the norms of the doctor–patient relationship may have occurred. While it is outside the scope of this paper to fully explicate these details, my main goal in this sub-section has been to show that empathy has not always been the default mode of interaction in medical practice.

Dangers of the empathic ideal

Although empathy may have some place in medicine, and may serve important functions, we face dangers when we take it to be an ideal unreflectively. In this section, I focus on three problems that arise or are exacerbated by taking empathy to be an ideal: (1) lack of conceptual clarity; (2) communication difficulties; and (3) detrimental looping effects.

Lack of conceptual clarity

There are many different concepts of empathy that exist in the literature. These concepts come from various fields and are often radically discontinuous with one another. While there is sometimes a degree of standardization within a given research group’s work, there is usually a high level of conceptual diversity across a given research area. Often, different empathy concepts track different psychological capacities.

This situation of conceptual diversity, and associated confusion, is widely acknowledged and is not new. Many researchers begin their articles with a statement about the number of different empathy concepts that exist in the literature before going on to specify what exactly they mean by empathy. Researchers also differ in their views about how to handle the conceptual diversity. I will not be able to provide a review of these various empathy concepts in this paper but for an extensive discussion, see Cuff et al. (2014). To make matters even more complicated, there are a number of other concepts that overlap with “empathy,” including sympathy and compassion. In medicine, there may be tension about the definitions of these concepts and how they relate to empathy. Writers on medicine furthermore worry about whether empathic engagement will lead to a kind of merging, over-identification, or projection.

The mere fact of the conceptual diversity is not in itself a danger for the use of empathy in medicine. The danger arises when people try to use the wrong concept for the job—when diversity becomes confusion. Taking empathy to be an ideal exacerbates the confusion, and facilities the slip from diversity to confusion, by lumping together a number of concepts and creating the impression that they are all the same, sufficiently similar, or interchangeable, which they are not. Such lumping also all too easily leads to the assumption that if one concept is good so too must be the others. It discourages reflectivity about what we really mean by empathy and what exactly it might be good for.

Reidar Pedersen, in a review of various measures of medical empathy (2009), does an excellent job of illustrating how conceptual diversity can lead to confusion and explicating the consequences of this. Pedersen (2009) identifies 38 different quantitative measures of empathy that have been used in the medical domain and points out various problems with them. One problem is that the scales tend to use items that are far removed from the patient-physician encounter and reflect, instead, general personal inclinations. This is in part due to the conditions surrounding development of the scales; many of the scales that are used in the medical domain were initially developed for use in social psychological investigations of, for example, prosocial behavior. Pedersen (2009) argues that these items may, in fact, be counterproductive to the medical interaction. He gives an example from Mehrabian and Epstein’s (1972) measure of emotional empathy (EETS):

For example, if you agree to the following statement—‘I am able to remain calm even though those around me worry’—this will reduce your empathy score. The same will happen if you disagree with ‘I tend to lose control when I am bringing bad news to people’ (both items are from ‘A measure of emotional empathy’). However, do we want the physician to lose control in such situations? (Pedersen 2009, p. 315).

According to the conceptualization of empathy embraced by this particular measure, losing control when bringing bad news to people is indicative of empathy while remaining calm is not. The Mehrabian and Epstein (1972) EETS scale also codes negatively for, “I am able to make decisions without being influenced by people’s feelings.” However, all of these things seem to go against our intuitions about what it means to be a good clinician; we want our clinicians to be able to remain calm in the face of worry even when bringing bad news. We do not want their decision-making to be overwhelmed by the influence of other people’s feelings. It would seem that we do not in fact want our clinicians to be empathic—at least not empathic in the way that Mehrabian defines and measures empathy.

Either we do not want our clinicians to be empathic or we need to abandon some conceptualizations of empathy—such as Mehrabian’s—as inappropriate for the clinical setting. This critique is important. It demonstrates that researchers who want to investigate medical empathy do not always stop to reflect on what traits or skills are specifically desirable in medicine. They too quickly jump to use scales that may be ill-suited to the purposes to which they are being put, even though scales designed specifically for the medical context, such as the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE), do exist.

These points highlight some of the difficulties inherent in taking empathy to be an ideal. The empathic ideal, as I noted earlier, involves both the sense that empathy is a good thing and a form of detachment from detail. But Pedersen’s analysis demonstrates that some level of detail is important here if we want to avoid collapsing all of the different empathy concepts together and as a consequence using the wrong one. Taking empathy to be an ideal is dangerous here because it may obscure the multiplicity of meanings of empathy and lead people to believe that any one will do—that they are all good. Empathy concepts need to be placed into context and have their aims and functions better articulated.

A second problem related to conceptual confusion is that it makes it very difficult to assess empirical evidence purporting to show the importance of empathy in medicine. Although there is a huge body of literature that suggests that empathy has a positive impact on medical outcomes, patient satisfaction (for a review, see Neumann et al. 2011) and more recently, even doctors’ mental health (Ekman and Halpern 2015), these studies importantly use different concepts and measures of empathy. Because of this, they cannot be taken to support overarching claims about empathy but instead, need to be treated with more care; when read closely, they allow us to see the benefits, or detriments, of specific kinds of empathy in specific contexts. The idealization of empathy obscures the specificity of the claims supported by individual research papers and thereby stands in the way of effectively incorporating the evidence they provide into medical education practices. Conceptual difficulties surrounding what it means to be empathic cannot be easily dismissed.

Finally, recent neuroscientific data supports the idea that there are multiple different processes or phenomena that have all been called “empathy.” Neuroscientists found a distinction between “emotional” and “cognitive” forms of empathy that rely on largely dissociable neural pathways (e.g., Singer 2006). More recent work also advocates a distinction between “empathy” and “compassion” (e.g., Singer and Klimecki 2014). In real-world contexts, these multiple separable pathways and phenomena may interact intimately with one another. The ways in which they interact, as well as they ways in which their operation may be modulated by context and other factors, are not yet well understood (for a helpful discussion, see Zaki and Ochsner 2012). Nonetheless, this research supports the idea that these different processes may, at very least, be implicated to different extents across different contexts. This neuroscience data also suggests that the different empathy measures and concepts may be tracking different phenomena and that we should be sensitive to those distinctions.

Communication difficulties

The second difficulty that I will discuss here is closely related to the first. Taking empathy to be an ideal unreflectively can lead to communication difficulties, between researchers rooted in different traditions, between researchers and medical practitioners, and between doctors and patients.

In the previous section, we saw how the communication difficulties play out between researchers rooted in different traditions. Researchers from one tradition—for example, in medical education studies—may unwittingly coopt measures or tools from a different tradition—for example studies of prosociality in social psychology—without realizing that they seek to measure a different phenomenon attached to a different concept. The use of the Mehrabian and Epstein scale in medical education research exemplifies this kind of communication difficulty. Just because a scale is labeled as an empathy scale, this does not mean it measures the kind of empathy being sought.

The same kinds of communication difficulties occur between researcher and participant, which in the case of medical education research, often means between researcher and practitioner. Pedersen (2009) nicely articulates how this occurs. Many scales rely on self-report techniques and involve stimuli that may use the word “empathy.” These stimuli depend on the participants having an understanding of empathy that is the same as—or at least close enough to—the definition being adopted by the researchers. This is a problem for some of the wider psychological literature on empathy as well, as Lauren Wispé (1986) points out in reference to studies that try to induce empathy: “If they [researchers] instruct subjects to empathize, the subjects do not know what empathy means…so they do not know what to do” (317). When the participants are medical practitioners, it also means there is a lack of correspondence between practitioners’ and researchers’ use of “empathy.”

Finally, communication difficulties arise within the doctor–patient relationship. What the patient means by empathy is not always the same as what the doctor means. Halpern, whose work I mentioned earlier, highlighted the increase in patient demand for empathy. The problem is that doctors’ conceptualizations of what it means to be empathic—and the conceptualizations embedded in the checklists on which they are evaluated—might differ drastically from what patients mean when they say that they want their doctors to be empathic.

Leslie Jamison, an essayist, nicely illustrates this discrepancy between patient conceptualizations of empathy and physician expressions of it. Jamison worked at one point as a medical actor. Medical actors are paid to pretend to have a certain set of symptoms so that medical students can practice clinical interaction and diagnosis. Jamison describes being given a script with a case summary including details about the character she is supposed to play, such as the character’s age, name, symptoms, and medical history. The cases that Jamison acted out as a standardized patient in her 15-min “encounters” with medical students ranged from the psychiatric to the orthopedic. After these “encounters” she evaluated the medical students on a checklist, the first part of which asked about the information that the medical student managed to elicit—did he or she manage to find out about the relevant symptoms?—the second part of which asked about the medical student’s affect:

Checklist item 31 is generally acknowledged as the most important category: Voiced empathy for my situation/problem’. We are instructed about the importance of this first word, voiced. It’s not enough for someone to have a sympathetic manner or use a caring tone. The students have to say the right words to get credit for compassion (Jamison 2014, p. 3).

Jamison’s insightful literary reflection on what it means to be empathic in a clinical context illustrates how much emphasis is put on voiced empathy in the training of medical students. It is not enough for the students to express empathy through gestures, facial expressions, or body language. Voiced empathy, however, can become formulaic. Jamison writes about how tired she got of hearing the same expressions of empathy—that must be really hard—over and over again. She also writes that this voiced empathy is usually insufficient.

In short, Jamison highlights the disconnect between the way in which empathy is conceived in medical education materials, the ways in which medical students—perhaps as a result of these training materials—enact empathy, and what she, as a patient, considers empathy to be. These communication difficulties are deeply problematic and suggest that the widespread assumption that empathy is important needs to be given more scrutiny.

Looping and social construction

A third danger in taking empathy to be an ideal is that it might lead us to create the wrong kinds of doctors. This danger follows on from my points about medical education but also draws on important work on social construction in philosophy.

Ian Hacking, an influential philosopher of psychology, has written extensively on what he calls “looping effects.” The crux of the argument is summed up in the following statement:

To create new ways of classifying is also to change our sense of self-worth, even how we remember our own past. This in turn generates a looping effect, because the people of the kind behave differently and are different. That is to say the kind changes, and so there is new causal knowledge to be gained and perhaps, old causal knowledge to be jettisoned (Hacking 1995, p. 369).

The essential idea is that when we create a human kind—when we classify humans—that kind is subject to change in part because people are self-reflective and also because there is usually value (positive or negative) attached to being a member of that kind.

Looping effects have received attention from philosophers of science because they seem to undermine the possibility of obtaining stable causal knowledge in the social and human sciences; looping effects are “moving targets” in Hacking’s terms (1995). They are also important, however, because they may be put to work in pragmatic and political contexts, insofar as they may lead to reconstitutions of the kind, or contribute to “ameliorative” projects, as Haslanger (2000, 2005) discusses in relation to race and gender. In this section, it is these pragmatic and political consequences that I am mostly concerned about.

Could there be such looping effects in the case of medical empathy? Broadly, the idea is that the social valuation of empathy has led to the creation of a kind of person—the empathic individual, or in medicine, the empathic doctor. Being classified as a member of this kind carries weight because empathy is a value-laden concept; it matters to one’s self-perception, one’s evaluation of oneself, and—in the case of medicine at least—even one’s career and professional standing, whether one is thought to be empathic or not. Because of the positive glow surrounding empathy, people will want to be classified as empathic and may change their behavior in order to do so. In medicine today, doctors want to be considered to be empathic. The problem is that the extent to which they are viewed as empathic largely depends on how they score on various measures that are used within medicine. These scales, through their connection with teaching techniques, promote a certain kind of empathy. Because so much seems to depend on being counted as empathic, doctors will try to manifest the kind of empathy that is being established through the scales, regardless of whether that particular behavior is necessarily most appropriate to the clinical domain. But as we saw earlier, following Pedersen (2009), sometimes those scales encapsulate precisely the wrong kind of empathy for medicine. The worry, then, is that the wrong kind of empathy will become entrenched in medical practice.

If these looping effects are at work, they could have important consequences, either positive or negative. As I just mentioned, looping effects may be dangerous if they are put into motion by measures and teaching techniques that track the wrong kind of behavior for effective clinical interaction—such as those described by Pedersen (2009). But there is also potential for more positive or “ameliorative” effects, as Sally Haslanger (2005) calls them, to be put into motion. The possibility of initiating such ameliorative effects underscores the importance of clarifying what it means to be empathic in medicine—what concept of empathy is best suited for the medical context, and what kind of behavior underlies calls for increased empathy in physicians.

Hacking’s work on looping effects fits into wider discussions about social construction, or the idea that certain concepts are created within particular social environments. In a recent paper, Hirshfield and Underman (2017) argue for more attention to social constructionist theory in medical education research, especially in relation to the concept of empathy. I heartily agree with them—especially their conclusion that social constructivist frameworks can be used to help explore contextual and group differences in empathy. More research on how social constructivist theory might be used to understand empathy interventions and their effects would provide a welcome addition here as well.

Steps in the right direction

Most of the dangers that I identified in the sections above stem from taking empathy to be an ideal unreflectively. There are ways around this lack of reflectivity. Although I have focused thus far on the wrong concepts of empathy for medicine—or the ways in which inserting empathy training into medical education can go wrong—there has been some very good work done to try to articulate a concept of empathy tailor-made for the medical context. Some of these attempts, as I noted earlier, involve the development of scales designed specifically for medicine. I will briefly say a few words about these scales, in particular the JSPE, but ultimately, I argue that despite their merits these scale-based measures and training techniques do not offer enough flexibility to be truly effective in medical education. Another body of work that has been effective is based in narrative, description, and firsthand clinical experience. This work helps to untangle the multiple aims of empathy in medicine. In the concluding section, I will argue that more explicit focus on these aims and goals, rather than on empathy per se, will yield more effective training interventions and research procedures.

One way in which the medical field has responded to the aforementioned measurement difficulties is by proposing alternative measures that have been developed with medicine in mind. One such measure is the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE), which relies heavily on a distinction between “sympathy” and “empathy,” where “sympathy” is defined as affective or emotional and “empathy” is defined as cognitive. Making such a distinction, between empathy and sympathy or between cognitive and affective empathy is a common move, and is supported by neuroscientific findings, but more recently, several authors have argued that too much has been made of this distinction, and that future research should focus on elucidating the interaction between cognitive and affective pathways (e.g., Halpern 2014; Zaki and Ochsner 2012). These critiques rightly point out that cognitive and affective elements may not be as easily separable in practice, and in real-world environments, as they are in the psychology or neuroscience lab. In any case, the distinction as made thus far has had a significant impact on the field, in medicine in particular.

The authors of the JSPE define empathy as follows:

To clarify the conceptual ambiguity associated with empathy, based on an extensive review of relevant literature, we defined empathy in the context of medical education and patient care as a predominantly cognitive (as opposed to affective or emotional) attribute that involves an understanding (as opposed to feeling) of patients’ experiences, concerns, and perspectives combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding. An intention to help by preventing and alleviating pain and suffering is an additional feature of empathy in the context of patient care (Hojat et al. 2009, p. 1183).

Empathy, on this view, is cognitive, concerned, and communicative. It involves understanding what the patient is going through without necessarily feeling what she feels. It also involves an intention to help. This kind of empathy, as we can see, is rather different from the “vicarious” or “emotional” forms of empathy that other scales, like the Mehrabian and Epstein scale critiqued by Pedersen, seek to measure.

While these scales tailored for medicine are a good move toward clarity and succeed in avoiding the kinds of issues that Pedersen points out, I am skeptical about the benefits of these kinds of measurement scales, and their use in medical training, more generally. These scales tend to promote a standardized form of behavior, while medicine requires behavioral flexibility. I am also concerned about the way in which these scales feature in the socialization of medical students. Because medical students are rated on the basis of these scales, this may lead them to focus too much attention on trying to emulate the standards embedded in the scales rather than developing the skills necessary to respond flexibly to a diverse set of circumstances and patient needs. For these reasons, I contend that although medicine-specific scales like the JSPE do better than other scales, especially in avoiding conceptual confusion, reflective narrative-based work does more to move debate about medical education forward.

Leslie Jamison’s work, which I discussed in some detail earlier in this paper, suggests that empathy in a clinical encounter looks rather different from what empathy checklists measure. For one thing, empathy need not be voiced. She illustrates her view of medical empathy through detailed literary vignettes. In one such vignette, she describes undergoing a heart operation involving the insertion of a pacemaker. The two features of the doctor that she highlights as most salient are his calmness and his ability to anticipate her worries and questions:

I remember being struck by how the doctor had anticipated a question about the pacemaker I hadn’t yet discovered in myself: How easily would I be able to forget it was there? I remember feeling grateful for the calmness in his voice and not offended by it. It didn’t register as callousness. Why?…His calmness didn’t make me feel abandoned, it made me feel secure. It offered assurance rather than empathy, or maybe assurance was evidence of empathy, insofar as he understood that assurance, not identification, was what I needed most (Jamison 2014, p. 17).

Jamison explains how the doctor was able to anticipate what she needed as an individual. He was able to provide her with information that she did not even know she needed—that on a thin frame like her own, the pacemaker would be visible in her chest. This in turn helped her to make a decision about which treatment option to pursue. With a different patient, the doctor might have responded differently, and provided different information. We can see how this doctor’s skill in anticipating a patient’s needs ties closely in with concerns about autonomy and decision-making. Jamison calls this skill “empathy.” She goes on to explain how this skill requires both anticipation and inquiry: “Empathy requires inquiry as much as imagination. Empathy requires you know nothing. Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see.. . .” (Jamison 2014, p. 5). Empathy, conceived as encompassing these qualities, is fundamentally epistemic in that it allows the physician to gain a better understanding of the patient’s situation and aid in the decision-making process.

Jodi Halpern relies on her own experience as a clinician to construct a model of empathy that is very much in line with Leslie Jamison’s. Within Halpern’s model, clinical empathy is defined as “engaged curiosity, in which the clinician’s cognitive aim of understanding the patient’s individualized perspective is supported by affectively engaged communication” (Halpern 2014, p. 302). In other words, clinical empathy can be viewed as a kind of emotional reasoning, an “attuned, curious listening” (Halpern 2001/2011, xii). It is a form of emotional engagement that facilitates understanding as well as cognitive reasoning and decision-making.

One achieves this kind of empathy by imagining how it feels to experience something. Imagining how involves imagining what something might feel like from the perspective of an agent whereas imagining that involves imagining a state of affairs from the perspective of an external observer. It is easiest to see this kind of empathy at work by considering an example. Halpern describes a case in which she treated a man who had been a successful business executive but was paralyzed from the neck down due to a sudden neurological disorder. When she first approached him, she treated him gently and even sorrowfully. He shut down. She left the room and imagined what it would be like to be a powerful older man in his enfeebled situation and the rage, frustration, and even shame he might feel. She approached her next encounter with him with a very different, much more businesslike tone rather than the comforting tone that she had used as standard with patients. The man opened up to her. This example illustrates how by shifting from imagining that to imagining how, she was able to better engage with her patient. It allowed her to approach the situation in a more individualized manner rather than with a standardized sympathetic tone.

Halpern argues that this kind of empathy contributes to diagnosis, patient autonomy, and therapeutic influence and thereby leads to “more effective, not just more pleasing, medical care” (Halpern 2001/2011, p. 94). It focuses physicians’ attention, facilitates decision-making, and supports patients in regaining a sense of autonomy. Halpern argues that this particular form of clinical empathy may even improve physicians’ quality of life, diminish feelings of personal distress, and facilitate feelings of satisfaction and meaning (Ekman and Halpern 2015; Halpern 2001/2011).

These more reflective approaches to empathy are admirably nuanced and add considerable clarity to the conversation about empathy in medicine. They offer approaches in which empathy is highly flexible and individualized, constituted within the specific dyadic relationship between patient and physician. This stands in contrast to other standardized conceptualizations, which largely see empathy as something experienced by the physician for the patient. These views are consistent with other recent trends in the empathy literature. For example, Grosseman et al. (2014) echo these ideas, suggesting that “empathy is located in physician–patient communication rather than within the physician” (p. 26). They go on to write that empathy is “in reality subtle, nuanced, context-driven, idiosyncratic, and deeply personal” (Grosseman et al. 2014). Stepien and Baerstein (2006) likewise express the idea that “clinical empathy requires flexibility to suit varying patients and circumstances” (p. 524). There is no one-size-fits-all approach to empathy in the medical encounter, on these views. Although empathy is widely valued, therefore, what it means to be empathy may look different in different contexts with different people.

Beyond offering highly flexible, individualized, and nuanced accounts of empathy, however, the reflective work also begins to reveal the aims underlying calls for empathy. Jamison’s work demonstrates that calls for empathy are often about a desire for increased or enhanced communication. Halpern’s account likewise foregrounds the communicative aims of empathy. She specifies how physicians are to achieve these communicative aims, through a delicate balance of emotional engagement and reasoned deliberation. But ultimately, the aim is to facilitate understanding of the patient and effective decision-making. These communicative aims of empathy stand in stark contrast to the aims embedded in the checklists. “Voiced” empathy is more about paying lip service to the patient’s desire for understanding. It calls to mind ideas about customer service or about creating a courteous, pleasant surface environment. Furthermore, the communicative aims of empathy stand in contrast to forms of empathy that have been studied outside medicine—the “emotional” empathy that is largely measured in social psychological research on prosocial behavior. This emotional empathy is the kind that the Mehrabian and Epstein scales, which are so inappropriate to medicine, measure. While Halpern’s form of communicative clinical empathy does involve emotional engagement, the emotional element is highly controlled whereas in many of the social psychological accounts, it takes over.

Through this, we can see the separable aims located behind calls for empathy. The first, I will call “epistemic” aims. Halpern and Jamison’s communicative accounts of empathy fall under this banner. They foreground the importance of understanding the patient and aiding in decision-making. While these communicative accounts may involve some emotional engagement, the emotions do not take over and remain in the service of gaining understanding of the patient. The second set of aims are “customer service” based. They are more about creating a courteous and pleasant environment within the clinical setting than about understanding or communicating with the patient. They may involve simple rote voiced expressions of understanding but may also be largely empty. These aims are not to be completely dismissed within the medical encounter. Some patients may appreciate this kind of general pleasantry and find that it helps them to open up. In this way, the customer service aims may sometimes be congruent with the epistemic ones. On the other hand, we can see how the customer service aims come apart from the epistemic ones in other cases; take Halpern’s business man as an example here. Thus, the aims are clearly separable. We can also see how it may be easier to motivate the epistemic form of empathy than the customer service form. The quote from Michalec’s (2011) interview with the medical student “Jake” is relevant here. “Jake” saw empathy as being all about niceness and dismissed it. Appreciating that the empathy training he received had more to it, and aimed to support patient-physician communication, may have allowed him to better see the importance of it. The third set of aims are what I will call “pure emotional engagement.” This may have some uses outside of medicine, although skepticism about this has been steadily growing. I think that we can agree that they are clearly inappropriate within medicine, however, and that scales that measure purely emotional forms of empathy need to be excluded from medical education research.

In the concluding section of this paper, I provide some more practical suggestions for how to avoid getting these aims confused. Should we call all of these things empathy?

Conclusion: the aims and goals of empathy

Thus far, I have argued that empathy currently constitutes an ideal of medical practice, meaning that it is highly valued and removed from the details of particular situations. I have also argued that there are several dangers to taking empathy to be an ideal unreflectively—many of which stem from conceptual confusions that obscure the multiple aims of empathy. I identified some steps in the right direction, which help to overcome some of the dangers. In particular, I praised the highly reflective work of Leslie Jamison and Jodi Halpern. This work succeeds in highlighting the goals that underlie calls for empathy. In this final section, I will argue that while this work has many merits—and I agree with many of the moves it makes—it does not fully succeed in circumventing the dangers of the empathic ideal. Moving away from “empathy” discourse and focusing more explicitly on the underlying aims and goals it so nicely illuminates would be a better strategy.

While authors such as Halpern succeed in providing a concept of empathy that is highly specialized, flexible, and well-suited to medicine, these more specialized forms may nonetheless get lost among all of the unreflective uses of the term “empathy” in the literature. Confusion surrounding the use of the term may impede the uptake of even these more nuanced forms of empathy. Halpern tries to identify her specialized conceptualization of empathy by calling it “clinical empathy” but even this term has been defined in multiple ways and may not make the concept easily distinguishable. While this is a largely linguistic matter, it is important when it comes to the pragmatics of medical training. Halpern hopes that her work “has shown the clinical importance of empathic curiosity and motivates us to value it” (Halpern 2014, p. 308). And she does indeed provide a convincing case for valuing such epistemic empathy. The problem is that the impression that empathy is about “niceness” or “friendliness” persists and the persistence of these more superficial concepts may make it difficult to motivate empathy in medical training and overcome medical students’ impressions that empathy is unimportant. In short, even the more nuanced conceptualizations of “empathy,” which truly move the debate forward, run the risk of getting absorbed in the idealization of empathy and the overhype surrounding it.

One option is to move away from the term “empathy” altogether and for medical practice, I argue that this is the right move. In the case of Halpern’s concept, doing away with the term “empathy” completely would be fairly easy. Clinical empathy, on her definition is simply “engaged curiosity” or “affectively engaged curiosity.” This is certainly a worthwhile skill for medical practitioners to cultivate and is very easily identified simply as such. Simply calling it “affectively engaged curiosity” demarcates it from less effective conceptualizations of empathy and detaches it from the baggage associated with them. It also foregrounds the aims that this concept seeks to achieve—better understanding of the patient. When it comes to the pragmatics of the medical context, where time is already scarce and physicians cannot be expected to sift through the immense number of empathy concepts and measures, this may be the most effective way to motivate the right kind of training without confusion. It would make the objectives as stated in the recommendations of professional bodies, for example, much clearer.

Another strategy is to keep the term “empathy”and adopt a pluralistic approach to it. For certain areas of academic work, this strategy may be the right one. Retaining the term “empathy” may be helpful because it will allow us, at least initially, to see the connections between the objects being studied in different fields. Here, embracing a kind of pluralism about empathy may be productive (Halpern 2014; Fagiano 2016).Footnote 2 Philosophers of science have pointed out that there are multiple ways to be a pluralist—a pluralism of pluralisms, if you will, and more research will need to be done to establish exactly what kind of pluralism we should embrace. Nonetheless, although the right kind of pluralism may help to clear up conceptual confusion in the case of academic research on empathy and prove a productive route forward, in pragmatic domains such as medical practice, there remain good reasons for splitting certain concepts, such as “engaged curiosity” off from “empathy.”

Important consequences stem from this recommendation to split rather than lump concepts that refer to forms of doctor–patient interaction. First, it will require a shift in the ways in which we write training materials for medical students and recommendations from professional bodies. It will also change the way that we think about measuring effectiveness in medical communication. It will re-situate discussions of the doctor–patient relationship within the context of medical ethics, autonomy, and decision-making, rather than within the wider societal hype about “empathy.” Most importantly, it will force us to think more clearly about what kinds of behavior we want our doctors to exhibit, how those behaviors might differ under different conditions, and how to train future physicians to cultivate those behaviors in a flexible, sensitive way. It will foreground the needs of medicine rather than the debate about a concept that is already experiencing tension from multiple sides.

Notes

Curiously, empathy appears only in some, but not all, of these training modules. It is unclear why this is the case.

Halpern (2014) suggests a move toward thinking about “empathies” rather than “empathy” in the clinical context as well: “Perhaps even more importantly, it is time to shift our focus from describing the fullest model of clinical empathy under ideal circumstances to studying the range of empathic processes or ‘empathies’—cognitive, affective and communicative subcomponents of empathy—that are practical in different clinical contexts. Finally, while experiencing full-blown affective-cognitive empathy is not under our direct control, clinicians can consciously cultivate empathic processes” (304). For the reasons discussed in the paper, I think it makes more sense to split certain concepts of medical communication away from empathy.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. 1998. Report 1: Learning Objectives for Medical Student Education, Guidelines for Medical Schools. Medical Schools Objectives Project. Washington, D.C., Association of American Medical Colleges.

Batt-Rawden, S. A., M. S. Chisolm, B. Anton, and T. E. Flickinger. 2013. Teaching Empathy to Medical Students: An Updated, Systematic Review. Academic Medicine 88 (8): 1171–1177.

Bloom, P. (2014). Against Empathy. Boston Review. Retrieved from http://www.bostonreview.net/forum/paul-bloom-against-empathy.

Bloom, P. 2016. Against Empathy. London: The Bodley Head.

Bloom, P. 2017a. Empathy and its Discontents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (1): 24–31.

Bloom, P. 2017b. Empathy, Schmempathy: Response to Zaki. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (2): 60–61.

Chen, D., R. Lew, W. Hershman, and J. Orlander. 2007. A Cross-sectional Measurement of Medical Student Empathy. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 (10): 1434–1438.

Colliver, J. A., M. J. Conlee, S. J. Verhulst, and J. K. Dorsey. 2010. Reports of Decline of Empathy During Medical Education are Greatly Exaggerated: A Reexamination of the Research. Academic Medicine 84 (4): 588–593.

Cuff, B. M. P., S. J. Brown, L. Taylor, and D. J. Howat. 2014. Empathy: A Review of the Concept. Emotion Review 0 (0): 1–10.

Ekman, E., and J. Halpern. 2015. Professional Distress and Meaning in Health Care: Why Professional Empathy Can Help. Social Work in Health Care 54 (7): 633–650.

Emanuel, E. J., and L. L. Emanuel. 1992. Four Models of the Physician-Patient Relationship. JAMA 267 (16): 2221–2226.

Fagiano, M. 2016. Pluralistic Conceptualizations of Empathy. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 30 (1): 27–44.

Fox, R. C., and H. Lief. 1963. Training for “Detached Concern”. In The Psychological Basis of Medical Practice, 12–35. New York: Harper & Row.

General Medical Council. (2007a). Advanced Training Skills Module: Menopause. Retrieved from http://www.gmc-uk.org/ATSM_Menopause_01.pdf_30452702.pdf.

General Medical Council. (2007b). Advanced Training Skills Module: Sexual Health. Retrieved from http://www.gmc-uk.org/ATSM_Sexual_Health_01.pdf_30450233.pdf.

Gerdes, K. E., E. A. Segal, K. F. Jackson, and J. L. Mullins. 2011. Teaching Empathy: A Framework Rooted in Social Cognitive Neuroscience and Social Justice. Journal of Social Work Education 47 (1): 109–131.

Grosseman, S., D. H. Novack, P. Duke, S. Mennin, S. Rosenzweig, T. J. Davis, and M. Hojat. 2014. Residents’ and Standardized Patients’ Perspectives on Empathy: Issues of Agreement. Patient Education and Counseling 96: 22–28.

Hacking, I. 1995. The Looping Effects of Human Kinds. In Causal Cognition: A Multi-Disciplinary Debate, eds. D. Sperber, D. Premack, and A. J. Premack, 351–383. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Halpern, J. 2001/2011. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Halpern, J. 2014. From Idealized clinical empathy to empathic communication in medical care. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 17: 301–311.

Haslanger, S. 2000. Gender and Race: (What) Are They? (What) Do We Want Them to Be? Noûs 34 (1): 31–55.

Haslanger, S. 2005. What Are We Talking About? The Semantics and Politics of Social Kinds. Hypatia 20 (4): 10–26.

Henry-Tillman, R., L. A. Deloney, M. Savidge, C. J. Graham, and V. S. Klimberg. 2002. The Medical student as patient navigator as an approach to teaching empathy. The American Journal of Surgery 183: 659–662.

Hirshfield, L. E., and K. Underman. 2017. Empathy in Medical Education: A case for social construction. Patient Education and Counseling 100 (4): 785–787.

Hojat, M., S. Mangione, T. J. Nasca, M. J. M. Cohen, J. S. Gonnella, J. B. Erdmann, J. Veloski, and M. Magee. 2001. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement 61 (2): 349–365.

Hojat, M., M. J. Vergare, K. Maxwell, G. Brainard, S. K. Herrine, G. A. Isenberg, J. Veloski, and J. S. Gonnella. 2009. The Devil is in the Third Year: A Longitudinal Study of Erosion of Empathy in Medical School. Academic Medicine 84 (9): 1182–1191.

Jamison, L. 2014. The Empathy Exams. London: Granta Publications.

Jordan, M. R., D. Amir, and P. Bloom. 2016. Are Empathy and Concern Psychologically Distinct? Emotion 16 (8): 1107–1116.

Kurtz, S., J. Silverman, and J. Draper. 1998. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Mehrabian, A., and N. Epstein. 1972. A Measure of Emotional Empathy. Journal of Personality 40 (4): 525–543.

Mercer, S. W., and S. W. Reynolds. 2002. Empathy and Quality of Care. British Journal of General Practice 52: S9–S13.

Michalec, B. 2011. Learning to cure, But Learning to Care? Advances in Health Sciences Education 16: 109–130.

Neumann, M., F. Edelhäuser, D. Tauschel, M. R. Fischer, M. Wirtz, C. Woopen, A. Haramati, and C. Scheffer. 2011. Empathy Decline and Its Reasons: A Systematic Review of Studies with Medical Students and Residents. Academic Medicine 86 (8): 996–1009.

Newton, B. W., M. A. Savidge, L. Barber, E. Cleveland, J. Clardy, G. Beeman, and T. Hart. 2000. Differences in Medical Students’ Empathy. Academic Medicine 75 (12): 1215.

Newton, B. W., L. Barber, J. Clardy, E. Cleveland, and P. O’Sullivan. 2008. Is There a Hardening of the Heart During Medical School? Academic Medicine 83 (3): 244–249.

Obama to Graduates: Cultivate Empathy. (2006). Northwestern University News. Retrieved from http://northwestern.edu/newscenter/stories/2006/06/barack.html.

Pedersen, R. 2009. Empirical Research on Empathy in Medicine—A critical review. Patient Education and Counseling 76: 307–322.

Prinz, J. 2011a. Is Empathy Necessary for Morality? In Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives, eds. A. Coplan, and P. Goldie, 211–229. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prinz, J. 2011b. Against Empathy. The Southern Journal of Philosophy 49 (1): 214–233.

Rothman, D. J. 1991. Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics Transformed Medical Decision Making. New York: Basic Books.

Shapiro, J., E. H. Morrison, and J. R. Boker. 2004. Teaching Empathy to First Year Medical Students: Evaluation of an Elective Literature and Medicine Course. Education for Health 17 (1): 73–84.

Silverman, J., S. Kurtz, and J. Draper. 2013. Skills for Communicating with Patients. 3rd Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis.

Singer, T. 2006. The Neuronal Basis and Ontogeny of Empathy and Mind Reading: Review of Literature and Implications for Future Research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 30 (6): 855–863.

Singer, T., and O. M. Klimecki. 2014. Empathy and Compassion. Current Biology 24 (18): R875-878.

Stepien, K. A., and A. Baernstein. 2006. Educating for Empathy: A Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21: 524–530.

Wispé, L. 1986. The Distinction between Sympathy and Empathy: To Call Forth a Concept, A Word is Needed. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50 (2): 314–321.

Zaki, J., and K. N. Ochsner. 2012. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy: Progress, Pitfalls and Promise. Nature Neuroscience 15: 675–680.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Tim Lewens, Jonathan Roberts, and my colleagues at the University of Cambridge, who provided helpful discussions as I began to think through the issues in this paper as part of my PhD research. I would also like to thank the Konrad Lorenz Institute for providing a wonderful, collegial environment within which to finish this paper. Finally, I would like to thank the audiences at the “Doctor, Doctor” conference in Oxford and the “Empathies 2017” conference in Basel for their attentiveness and helpful feedback. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers, whose feedback greatly improved the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research as well as a PhD fellowship funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC Grant Agreement no 284123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Betzler, R.J. How to clarify the aims of empathy in medicine. Med Health Care and Philos 21, 569–582 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9833-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9833-2