Abstract

This paper examines the role of the board of directors in influencing the value of Italian listed firms from 2003 to 2013. In particular, employing agency, stewardship and resource dependence theories, the study aims to compare board characteristics in family and non-family firms and define the theory that best applies to family firms. Empirical results show that the presence of CEO duality and busy directors has a positive effect on the value of family firms, while gender diversity has a negative impact on the value when a member of the family leads a family firm. Conversely, the size of the board positively affects the value of non-family firms. Our main findings suggest the prevalence, in family firms, of the benefits of the board structure argued by stewardship and resource dependence theories rather than the disadvantages expected from agency theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An aspect that is gaining increasing attention from scholars of corporate governance concerns the study of the characteristics that the board of directors should possess to ensure efficient management control and valuable support in the decision-making process (Stiles and Taylor 2001; Zattoni 2006). The appropriate achievement of these major tasks can affect corporate governance, creating ideal conditions so that it is possible to operate in balance, protecting the rights of all shareholders.

A strong corporate governance can be a valuable tool for shareholders to reduce agency problems (Jensen 1993) and encourage managers to maintain shareholders’ satisfaction while operating. An effective board of directors must be capable of preventing opportunistic behaviour of the controlling shareholder and/or firm management, thus reducing agency costs resulting from inefficient management of the firm.

However, in the firms, various conflicts of interest may exist, which may depend both on the type of company and the ownership structure of the firms. In this context, a key aspect is the different role that the different characteristics of corporate governance between family and non-family firms (Bartholomeusz and Tanewski 2006) must play to reduce agency conflicts existing in the company.

In fact, the controlling shareholders of family businesses tend not only to assume the firm’s managerial control (Corbetta and Tomaselli 1996) through the appointment of a familiar member in the role of CEO but at the same time appoint many family members to the board. In such situations, characterised by a complete convergence between ownership and management, there are lower agency costs of type I, those that arise between shareholders and managers. Similarly, when families are not also involved in top executive roles in the boards, high family ownership concentration allows for the problems arising from the separation of ownership and management to be overcome through effective monitoring of management actions, resulting in the contraction of opportunistic initiatives from managers. Therefore, families seem to be able to mitigate the owner-manager agency problem described by Jensen and Meckling (1976). At the same time, however, family control exposes the company to potential agency problems of type II, namely conflict of interest between majority and minority shareholders (Anderson and Reeb 2004). In this case, the controlling shareholders can use their privileged position to expropriate value at the cost of minority shareholders (Morck et al. 1988). The coexistence of ownership and control in a family can generate an excessive role by the owner, which can lead to problems of management entrenchment. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) provide evidence that controlling shareholders try to extract benefits from the firms. The family shareholders, who often hold the control of the firm, might use their concentrated blockholding to expropriate the wealth from other minority shareholders (Anderson et al. 2002; Anderson and Reeb 2003; Fama and Jensen 1983). Instead of maximising firm value, families can also use business resources to obtain private benefits (Fama and Jensen 1983; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). Therefore, the consequence of family control is that the agency problem between managers and controlling shareholders (type I) is smaller, but there are other higher agency problems (type II) between controlling and minority shareholders (La Porta et al. 1997).

With regard to non-family businesses, considering that the main shareholders usually are not actively involved in the company’s management as in family firms, they decide to opt for an external professional CEO. As a result, the large shareholder’s incentives for expropriating minority shareholders are small. On the contrary, in this type of companies, there could be relevant conflicts between shareholders and managers, which could have opportunistic behaviour directed towards obtaining personal benefits, implicating higher agency costs of type I in the firms.

Because the firm directors have direct access to a series of information related to strategic management, strengthening the board is a way to improve the management of the firm’s resources and allows for the monitoring of the CEO’s actions. In fact, the board of directors plays the role of a monitor and provides advice to senior management regarding major business decisions. Its effectiveness is evaluated by the ability to align the interests of both managers and shareholders, reducing the potential loss of value of the firm (Jensen and Meckling 1976).

As stated previously, in recent years, the studies on corporate governance have focused their attention on the analysis of the structure of the board (Daily et al. 2003; Di Pietra et al. 2008; Zattoni 2006). Nevertheless, the empirical evidence on the relationship between board structure and corporate financial performance is still uncertain (Dalton et al. 1998, 1999; Minichilli et al. 2009). Numerous studies have been conducted on the effect of corporate governance on firm value, arriving at very different conclusions. Some of these studies concluded that there is a positive relationship between board characteristics and firm value (Anderson and Reeb 2004; Kowalewski et al. 2010; Maury 2006; Villalonga and Amit 2006; San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada 2012), while other studies found a negative relationship between some corporate governance variables and firm value (Guest 2009; De Andres et al. 2005; Jackling and Johl 2009; Adams and Ferreira 2009). Dissimilar results are found, especially within family firm studies, depending on the variable used to study corporate governance, sampling techniques, econometric methodologies, study periods, and institutional settings that different scholars consider (Sacristán-Navarro et al. 2011). These conflicting empirical findings are also confirmed for family firms. As demonstrated by O’Boyle et al. (2012) in their meta-analysis, the comparison between performance in family and non-family firms depends on many aspects.

In this study, we adopt the agency perspective, the stewardship theory and the resource dependence theory to investigate the impact of the composition of the board of directors on the value of Italian family and non-family listed firms for the period of 2003–2013. We focus in particular on five characteristics of the board of directors: Chief Executive Officer duality (the CEO is also the chairman of the board), the presence of independent and busy directors, and the size of the board and its gender diversity (the presence of female directors on the board).

Different theories predict dissimilar effects of board characteristics on firm performance; in our sample of firms, 75% of listed firms are classified as family firms; the effects of board characteristics may be affected by the type of firms (family vs. non-family). Hence, the objective of the study is the comparison of results in family and non-family firms in view of the various theories of corporate governance and to test which theory applies best to family firms.

The Italian context provides an interesting institutional setting to address these questions. Apart from being characterised by weak legal protection of minority investors, inefficient law enforcement and high ownership concentration (Volpin 2002), the Italian stock market includes a large percentage of family-controlled companies of all sizes (Minichilli et al. 2015), characterised by some variability of family members in management and board positions. The existence of strong family ownership, either involved or not in the management, could have important implications for management behaviour in defining the correct strategies that determine firm value. In addition, the choice to have a medium-long period of analysis is dictated by the consideration that, usually, the boards of directors of companies remain in office for three years, but rarely is it radically renewed every three years. Therefore, a sample period of eleven years allows us to take into account a real change in the composition of the board in time that would not have been possible if the sample period was shorter.

Based on a sample of 1613 observations and 193 Italian listed firms, empirical results show that board characteristics may differently affect the value of family and non-family firms.

CEO duality, busy directors and gender diversity appear to be able to affect family firm value. Differently for the sub-sample of non-family firms, CEO duality and busy director variables are positive and statistically significant both in family firms (according to a general definition) and in family firms with members involved in management. Instead, female directors have a negative influence only on the value of the sub-sample of family firms with families actively in management. Diversely, board size positively impacts the value of non-family firms. Finally, contrary to our expectations, the presence of independent directors does not appear to affect the value either of the family or of the non-family firms.

The results of the empirical analysis, despite showing the presence of a number of board variables that can affect family firm value, are not consistent with the formulations indicated by the agency theory but are in line with the predictions of the stewardship and resource dependence theories.

The business culture in the Italian context has developed over recent years, leaving little room for agency problems among the various actors involved either directly or indirectly in the firms. The development of the financial system and the superior supervision by market authorities (i.e., CONSOB) have implied greater disclosure and transparency in companies. Therefore, the features of the board that, following previous literature, were linked to a negative impact on business performance, now contribute to the growth of corporate value. The potential negative effects arising from agency problems are overwhelmed by the benefits that certain peculiarities of the board bring to the company.

The work is divided into four main sections. The first part describes the literature, focusing on the relationship between the board of directors and firm value and identifies the research hypotheses. The second section describes the sample selection process and data used. The third section discusses the main results, and the last section presents the conclusions.

2 Board of directors and firm value: research hypotheses

The board of directors plays a primary role in the organisation of the company. It is responsible for monitoring and advising management activities (Raheja 2005; Adams and Ferreira 2007). However, these are not the only roles that it must play. Among its other tasks are various important activities, such as support for strategic decision making, representation and protection of minority shareholders, and the responsibility of defining strategic and organisational actions (Hillman and Dalziel 2003; Gabrielsson and Huse 2002; Van den Berghe and Levrau 2004; Adams et al. 2010).

The structure of the board is closely connected to the quality of corporate governance. From an analysis of the literature, it emerges that firms with weak governance structures and poor protection of shareholder rights are implicated in more agency problems and that the presence of an effective board of directors can help avoid the opportunistic behaviour of managers, determining the alignment of their objectives with those of the corporate shareholders. To analyse the corporate governance mechanisms, many studies refer not only to the ownership concentration or governance indices appropriately created but also consider the main characteristics of the members of the board of directors. In fact, the different composition of the board of directors may determine the creation of a strong corporate governance that operates in the interests of all shareholders and that is aimed at creating business value or a weak corporate governance that is unable to maximise the total value of the firm due to problems of managerial opportunism or agency conflicts between controlling shareholders and minority shareholders.

However, the characteristics of the boards of directors are not the same for all types of companies. Bartholomeusz and Tanewski (2006) show that family firms utilise different corporate governance structures from non-family firms and that these differences lead to performance differentials. On the one hand, some researchers confirm that family companies generally have weaker governance practices than non-family firms (Anderson and Reeb 2004), which could indicate high agency costs and the will by the family to extract private benefits. Morck and Yeung (2003) note the expropriation of wealth from non-family shareholders to family companies. Instead, Pérez-González (2006) observes the lack of professional capability by the families involved in the management of the firms, which could cause a less efficient board in the company. However, various academics state that family firms are positively distinguished from other companies because their main shareholders pursue both financial interests and non-economic goals that create socio-emotional wealth (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Under this perspective, where the members of the family are viewed as a resource for the firm, Minichilli et al. (2015) find that family firms produce better performance when they are managed by a family CEO. Similarly, Anderson and Reeb (2003) reveal that when family members serve as CEO, performance is better than with outside CEOs. Family businesses are characterised, among other things, by ownership concentration and particular features that set them apart from other large shareholders. Like different types of blockholders (state, institutional investors and other firms), concentrated shareholders have strong economic incentives to decrease agency costs and increase firm value (Demsetz and Lehn 1985). However, family shareholders are the only investors that usually have invested most of their private wealth in the company and who have strong incentives to monitor management closely to avoid opportunistic behaviour and allow firm survival.

As a result, the findings of the empirical evidence are mixed and inconclusive. Whether family firms have a better or worse performance may depend on many aspects, including the institutional context of each country, the ownership structure of the family and the involvement of family members in management.

The discussion on the advantages and disadvantages related to family ownership has led researchers to dedicate increasing attention to the relationships between family characteristics and firm financial performance (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Villalonga and Amit 2006). Nevertheless, most studies analyse the relationship between the characteristics of the board and corporate performance by referring principally to the agency theory (Minichilli et al. 2009).

As stated from Corbetta and Salvato (2004a), integrating more than one theory helps to better understand the important functions of the board of directors. Therefore, we formulate the hypothesis on the effects of the board of directors on firm financial performance through several theories: agency, resource dependence and stewardship theories.

From an agency theory perspective, the main mission of the board is the monitoring of management. Board structure assumes the role of principal and, on behalf of shareholders, supervises managers’ decisions. Because shareholders invest considerable financial resources in the firms, a principal-agent problem may arise because the managers may invest these funds to purse their self-interest at the expense of profit maximisation. Thus, having an efficient board of directors can be an effective method to improve firm performance by reducing agency costs (Fama and Jensen 1983; Jensen and Meckling 1976).

Referring to the resource dependence theory perspective (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), boards of directors lead to the provision of resources to the firm. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) suggest that directors bring four different types of benefits to the firms: advice and counsel, special channels for information, preferential access to resources and legitimacy. Similarly, Hillman and Dalziel (2003) identify board capital, which consists of both human and relational capital, as a valuable resource for the firm. The first includes expertise, skills, knowledge and reputation of the directors, while the second concerns resources available through a network of relationships. Selecting directors with valuable capabilities helps the board of directors to provide active support to management, advising strategic alternatives aiming to improve the quality of strategic decision making (Stiles and Taylor 2001) with beneficial effects for the firm.

However, according to the stewardship theory, the key role of the board of directors is to support firm management rather than to monitor and supervise (Corbetta and Salvato 2004a). Under this vision, managers and directors are not interested in personal aims, but they operate to improve the decision-making processes of the firms through their experiences and competencies (Minichilli et al. 2009). Therefore, they represent a precious resource for corporate boards (Donaldson and Davis 1991) in being able to positively affect the market valuations of the firms (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2009).

Academic researchers agree that managers of widely held firms may decide to use the resources of the business to expropriate private benefits to the detriment of the minority shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny 1997; La Porta et al. 1999). At the same time, current research highlights that the magnitude of agency costs is different between family and non-family firms (Corbetta and Salvato 2004b). In fact, because firms controlled by families do not have agency costs that result from divergent interests between management and shareholders, agency costs are lower in family firms than in non-family firms (Chrisman et al. 2004). Agency problems seem to be less important in the context of family firms with a high concentration of ownership because the controlling shareholders already have sufficient incentives, power and information to control the top managers (Jensen and Meckling 1976).

Given these observations, the development of our hypotheses is based on the idea that agency theory can be used to explore the characteristics of the board in non-family firms, while stewardship theory and resource dependence theory, considered by scholars to be more evident in family firms than in non-family firms (Corbetta and Salvato 2004a; Lubatkin et al. 2007; Pieper et al. 2008), are used to examine board features in family firms.

In this regard, to define which of these opposing theories better explains the role of boards of directors in family firms, we analysed the role of CEO duality, the presence of independent and busy directors, the size of the board and gender diversity in the board. The presence and extent of these characteristics, which are the subject of the study, may either cause an increase in the agency costs in the firm with the natural consequences of poor business performance or determine business skills and specialist expertise to improve the efficiency of the board and their ability to support managers and mitigate conflicts of interest between shareholders, with consequent benefits for the entire firm. Assuming that non-family firms need supervision by their boards more than family firms, we develop a model to empirically test each of the five board characteristics under analysis.

For each variable of the board, we propose two hypotheses. The first refers to the expected effect of the board variable on firm value for the entire sample of firms (without a distinction between family and non-family), while the second refers to the comparison between family and non-family businesses.

2.1 Hypothesis on CEO duality and firm value

Establishing whether dual leadership structure is better or not for companies is one of the most debated issues in corporate finance. At least two alternative views can explain the relationship between CEO duality and firm value.

On the one side, agency theory suggests that CEO duality is bad for performance because it compromises the monitoring and control of the CEO (Peng et al. 2007). Chairman-CEOs can take advantage of their dominant position with respect to relevant shareholders and/or minority shareholders, causing the expropriation of corporate assets. The condition of CEO duality, according to Fama and Jensen (1983), hinders the ability of the board to monitor management and therefore implies an increase in agency problems. This feature of governance, by concentrating the decision-making powers and operating in the hands of the CEO, creates conditions for potential disagreements with shareholders, which exacerbate conflicts of interest between principal and agents (Jensen and Meckling 1976). According to agency theory, CEOs are self-interested, risk averse and have objectives that differ from those of the shareholders. Therefore, when the opportunity arises, they will engage in self-serving actions at the expense of shareholders (Jensen and Meckling 1976).

On the other side, stewardship theory suggests a different perspective on the role that CEO duality plays in the firms. It argues that CEO duality permits strong leadership and a faster decision-making process and, consequently, may be good for performance (Donaldson and Davis 1991). The alignment between managers and shareholders creates an essential and fundamental unity of command and clear leadership at the top of the firm (Finkelstein and D’Aveni 1994). CEO duality, therefore, helps to avoid ambiguous leadership and confusion in the board’s operating procedures. Otherwise, conflicts between agents and principals can reduce speed and effectiveness in decision making and, finally, result in poor performance (Brickley et al. 1997; Donaldson and Davis 1991). According to the stewardship perspective, a firm characterised by duality is likely to be strongly managed to produce good results for all owners, including both majority and minority.

Referring to CEO duality in family firms, the main shareholders can opt for the total involvement of family members in management, or they can devolve the dual role to an external manager. The consequences of that choice of managerial administration originate, also in these types of firms, from two opposing perspectives. On the one hand, the supporters of the agency theory argue that family CEO duality will lead to private benefits within the family, while on the other hand, the defenders of the stewardship theory (Miller et al. 2008) posit that a family CEO creates the ideal conditions to have a greater competitive advantage in the firms.

Under the perspective of agency theory, according to whether the top manager is a family member or not, the role played by the family can amplify rather than reduce the effects of CEO duality on performance.

In the presence of members of the family involved in the management of the firms, where CEO duality therefore converges into a single family member, substantial agency problems (type II) could arise between the majority shareholders who also play the role of manager and the minority shareholders. Family managers may prefer to achieve personal goals that are not strictly strategic but are suited to the manager-shareholder. Consequently, some opportunistic and personal behaviour could lead to the extraction of private benefits at the expense of other non-family shareholders (Morck and Yeung 2004). At the same time, many authors note how the alignment between management and ownership mitigates the high costs resulting from agency problems (type I), leading to an improvement in performance (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Villalonga and Amit 2006). The coincidence of roles in one family member prevents the emergence of conflicts, which are able to cause a reduction in business value, between those who manage the company and those who control the managers.

Alternatively, when the family is involved only in the ownership of the firms and the dual role of CEO and chairman of the board is covered by an external manager, family majority shareholders are limited to supervising management operations without directly intervening in the management of the firm. The high concentration of ownership in the hands of the family can be a useful corporate governance mechanism because large shareholders have a greater incentive to monitor managers than minority shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny 1986). Consequently, the possibility of a manager adopting fraudulent behaviour is much lower, causing a drastic reduction in type I agency conflicts between managers and reference shareholders, leading to higher value in the company (Maury 2006; San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada 2012).

Following the stewardship theory perspective, the connection of the top managers with the family creates a strong sense of duty, especially in relation to other family members and minority shareholders, creating the right conditions to contribute actively to a prudent management of resources that allows firm continuity (Arregle et al. 2007). Miller et al. (2008) compared the potential benefits and negative aspects that family managers can generate in enterprises and concluded that family management has numerous benefits in firms. First, family leaders wish for company longevity, continuing to invest adequately to increase turnover, so as to retain benefits for all family members (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Habbershon and Williams 1999). Another distinguishing feature that can provide advantages for firms is the ability to forge strong links with their employees and partners, who will be loyal to the company and will operate for the benefit of all (Arregle et al. 2007; Ward 2004).

According to agency and stewardship theory approaches and considering that family firms have lower agency costs than non-family firms, our first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H1a

CEO duality affects firm value.

H1b

CEO duality affects family firms more positively than non-family firms.

2.2 Hypothesis on independent directors and firm value

Anderson and Reeb (2004) highlight that both agency and stewardship theories indicate a positive effect of independent directors on firm value in two different ways. In agency theory, independent directors monitor and control the management, decreasing the agency costs of type I. However, under the stewardship theory, independent directors provide valuable counsel to the CEO, improving the board’s decision making.

Referring to agency theory, Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007) review the role of corporate governance in mitigating agency costs and in affecting firm results and find that companies with weak corporate governance dissipate resources very quickly compared to those that are well governed, causing lower performance.

Ample empirical evidence argues that the presence of independent directors safeguards shareholders when agency problems exist (Brickley and James 1987; Hermalin and Weisbach 1988; Byrd and Hickman 1992). The presence of a larger number of independent directors who are in a better position to monitor the manager allows for their work to be carefully observed, leading to a better understanding of business strategies. They are particularly interested in safeguarding their professional reputation (Fama and Jensen 1983) and therefore carry out their duties with total transparency and diligence by providing monitoring of a superior quality. Boards of directors comprising a considerable percentage of independent members reduce the managerial domain and information asymmetry, increase the quality of monitoring of possible opportunistic behaviour of management and improve the effectiveness of boards in advising business operations (Chahine and Filatotchev 2008).

From a stewardship perspective, the board of directors is described as a group of highly qualified people who aim to assist the management of the firm in the performance of their duties (Daily et al. 2003; Hillman and Dalziel 2003; Corbetta and Salvato 2004a). The independent directors represent a human asset of immense value in the company (Donaldson and Davis 1991). Thanks to their experiences and different points of view, they are able to advise and support the top management (Minichilli et al. 2009). As a result, the company’s controlling shareholders may decide to identify future independent directors on the basis of their competence with respect to the sector in which the company operates to maintain an efficient and professional board of directors that is able to actively support the CEO in the management of the company.

However, family dynamics undermine the effectiveness of outside directors (San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada 2012). Despite the clarity of advantages of outside directors in the firms, family firms are less likely to use outside directors (Schulze et al. 2001). These data are also confirmed in our sample of firms. In fact, the percentage of independent directors in family firms is 36.3%, while in non-family firms, they represent, on average, 46.5% of all directors.

In addition, they have little influence on decisions involving family members (Nelsen and Frishkoff 1991). As a result, the lack of consideration by family shareholders does not allow them to actively participate in the company and to make available their full abilities in terms of valuable advice in support of the manager. Finally, despite the theoretical point of view, this category of directors has no connection with the management and/or major shareholders, and in reality it is very difficult to identify them as truly independent (García-Ramos and García-Olalla 2011). In fact, as stated by Di Pietra et al. (2008), some members of the board who currently hold the role of independent directors could have in the past had roles at other companies belonging to the same corporate group or could have personal relationships with managers and/or the controlling shareholders. As a result, their status as impartial advisors fails, compromising the independence of the board (García-Ramos and García-Olalla 2011).

According to agency theory and stewardship theory approaches and considering that family firms may tend to choose independent directors not for their professional skills but for their own personal relationships, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2a

Independent directors positively affect firm value.

H2b

The positive effect of independent directors on firm value is weaker in family firms than in non-family firms.

2.3 Hypothesis on busy directors and firm value

The question of directors who sit on several boards can be analysed from two alternative perspectives. Agency theory states that directors with more than one directorship can become so busy that they cannot monitor management sufficiently, compromising their responsibilities and neglecting their duties, especially in terms of managerial monitoring (Core et al. 1999). The second, known as the reputation effect (Jiraporn et al. 2009b), which originates from the resource dependence theory literature, posits that busy directors provide benefits for firms and bases its considerations on the thesis that recognises a status of excellent administrators for members who sit simultaneously on more than one board and who, thanks to their experience, provide useful networks and business contacts that can improve board decision making and consequently firm value.

The existing literature provides mixed evidence on the relationship between busy directors and firm value. On the one hand, overworked directors have been criticised as being ineffective because they tend to spend less time with each individual firm and might shirk their responsibility as monitors. Jiraporn et al. (2009a) show that directors with multiple board seats are more likely to be absent from meetings, with the risk of not being able to take part in strategic decisions. Shivdasani and Yermack (1999) argue that the directors involved may cause, due to only mildly monitoring the actions of managers, an increase in agency costs that, in turn, results in the destruction of corporate value. Fich and Shivdasani (2006) confirm that companies with a majority of busy outside directors display significantly lower market-to-book ratios and are associated with weak corporate governance.

However, there is empirical and theoretical literature that also highlights potential benefits of busy board members. Consistent with Fama and Jensen (1983), who support that outside directors have incentives to develop their reputation, Ferris et al. (2003) find no evidence that multiple directors shirk their responsibilities to serve on board committees. Differently, Perry and Peyer (2005) report that when executives have strong incentives to enhance shareholder value, i.e., when executives have high equity ownership, the accumulation of board seats has a positive impact on firm value. Similarly, Harris and Shimizu (2004) argue that busy directors can recognise problems faster and are important sources of knowledge that can counsel the CEO in important decisions. Other empirical evidence (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) recognises that individuals with several advisory appointments, characterised by a good reputation in the financial markets, may use their professional contacts to ensure competitive advantages for the company they represent. Masulis and Mobbs (2011) argue that members with several advisory appointments, thanks to their experience and knowledge, can improve firm performance.

With regard to family firms, excluding the recent paper by Pandey et al. (2015) that analyses the link between busy CEOs and the performance of family firms in India and shows that the level of CEO busyness has a negative effect on firm performance, to our knowledge, there is no literature to specifically examine how busy directors affect the value of family firms. However, we know that the main family shareholder is broadly interested in the survival of the firm (Zahra and Pearce 1989). Thus, in choosing a team and governance structure, the members of the board could specifically opt to choose busy directors as their special advisors who are able to enhance the efficiency of the board rather than for their monitoring capabilities. Because interlocking directors have significant experience and expertise, multiple directorships held by boards of directors should be positively related to firm value. The role of busy directors in family firms may be explained better by resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) rather than agency theory. Thus, in choosing a team and governance structure, the members of the board could specifically opt to choose busy directors as their special advisors who are able to enhance the efficiency of the board rather than for their monitoring capabilities. Because interlocking directors have significant experience and expertise, multiple directorships held by board members should be positively related to firm value.

Agency and resource dependence theories lend different perspectives on the effect of busy directors on firm value. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3a

Busy directors affect firm value.

H3b

Busy directors affect family firms more positively than non-family firms.

2.4 Hypothesis on board size and firm value

Empirical evidence (Lipton and Lorsch 1992) identifies the size of the board as an important feature that can determine the effectiveness of corporate governance. Findings on the impact of board size on firm value are conflicting. The literature suggests that a large board size can have positive and negative effects: greater monitoring versus more rigid decision making (Harford et al. 2008).

From the perspective of agency theory, it can be argued that a larger board of directors can be more vigilant of the manager simply because more people are monitoring operations and managerial behaviour. According to Lehn et al. (2009, p. 749), “the major advantage of large boards is the greater collective information that the board possesses about factors affecting the value of firms”, which is also valuable for monitoring (Haleblian and Finkelstein 1993). The model of Harris and Raviv (2008) suggests that a larger board will provide optimal monitoring in the presence of managers who operate in a firm where there are real opportunities to consume private benefits. Additionally, Boone et al. (2007) confirm the hypothesis that large boards of directors are fully efficient in firms where managers can adopt fraudulent behaviour, where the aim is to satisfy personal desires at the expense of shareholders. Coles et al. (2008) find that the relationship between the market value of the firm and board size is U-shaped. They challenge the assertion that boards with more than seven to eight members are ineffective. On the contrary, they suggest that either very small or very large boards are optimal.

Conversely, a larger board size may be more difficult to coordinate, and it is likely to develop factions and coalitions among members, leading to the creation of communication and organisational problems. Consequently, these issues may prevent the perfect functioning of the board, resulting in the postponement of important decisions and thereby removing effective management control (Eisenberg et al. 1998; Forbes and Milliken 1999). Informational asymmetries, communication issues and decision making generate lower performance. Yermack (1996), in a sample of US firms, and Eisenberg et al. (1998), in a sample of small non-listed Finnish firms, find a negative relationship between board size and firm value. Conyon and Peck (1998) examine the effects of board size on performance across a number of European countries and demonstrate that board size is inversely related to firm value. Guest (2009) finds that board size has a strong negative impact on profitability, Tobin’s Q and share returns. He also cites problems of poor communication and decision-making among the main reasons that determine the ineffectiveness of large boards. In line with these results, Mak and Kusnadi (2005) also find an inverse relationship between board size and firm value in a sample of listed firms in Singapore and Malaysia.

Within the context of family firms, the corporate governance literature is divided regarding the adequate size of the board. Neubauer and Lank (1998) state that smaller boards are more desirable for family businesses. Additionally, Lane et al. (2006) suggest that small boards are beneficial for family firms because larger boards may inhibit full family member participation. Larger boards in family businesses may be associated with less cohesion among the directors. Conversely, Zattoni et al. (2015) capture the positive use of knowledge and skills on the boards of family firms. Their theoretical model highlights that family involvement in business has a significant influence on board internal processes and tasks, and through these, on a firm’s financial performance.

Usually in family companies, ownership and control are in the hands of one or a few individuals who are members of the same family (Fama and Jensen 1983; Van den Heuvel et al. 2006), and thanks to their dominant position, having a significant influence over the appointment of board members, they favour the selection of people who can actively contribute to the growth and success of the company. The main shareholder can decide to increase the size of the board to combine multiple abilities and perspectives to reinforce the management team (Westphal 1999). Therefore, the family can add non-family directors in the board, not only for their reciprocal social ties but also for the relevance of their peculiar competencies and skills (Johannisson and Huse 2000) that can mitigate the lack of managerial abilities of entrepreneurs (Van den Heuvel et al. 2006). These indications fit perfectly with a resource-dependence point of view. From this perspective, a larger board of directors is likely to function effectively, as directors may provide advice to and counsel the management on numerous issues (Westphal 1999).

Considering that in our sample of firms the average number of directors in family firms is lower than in non-family firms (the average board size in family firms is 9.27, while in non-family firms, it is 10.45) and that previous studies have assumed that family firms have weaker agency problems than non-family firms, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4a

Board size affects firm value.

H4b

Board size affects family firms more positively than non-family firms.

2.5 Hypothesis on female directors and firm value

Given the many legislative initiatives that aim to increase the number of women on the boards of public and private companies, the issue concerning the gender diversity of the board has become an area of study by scholars around the world. Consequently, in recent years, researchers have begun to study the impact of the presence of women in the board on the efficiency of business decisions and their ability to influence corporate performance (Mohan and Chen 2004; Levi et al. 2014; Huang and Kisgen 2013). The empirical findings show mixed evidence. Some authors find a positive relationship (Dezsö and Ross 2012; Lückerath-Rovers 2013; Liu et al. 2014; Terjesen et al. 2015), while other researchers observe the presence of a negative link between diversity and firm value (Adams and Ferreira 2009; Ahern and Dittmar 2012). The importance of gender diversity on boards can be described both by the vision of agency theory and in the resource dependence framework.

From an agency theory perspective, the presence of female directors in the board should increase a company’s profits, primarily by reducing agency problems in the firms and improving monitoring abilities. Many studies (Adams and Funk 2012; Adams and Ferreira 2009; Rhode and Packel 2014; Carter et al. 2003) see a better ability to monitor managers’ behaviour in a heterogeneous board. A board with different cultural backgrounds is a carrier of multiple and different points of view that contributes, among other things, to a more thorough supervision of the management (Anderson et al. 2011). In this respect, the presence of women directors seems to have an effect that is very similar to that of independent directors (Adams and Ferreira 2009). Consequently, their presence on boards of directors can improve monitoring functions (Rhode and Packel 2014). In addition, gender diversity pays serious attention to conflict of interest issues and, at same time, female involvement on corporate boards raises a company’s attention to the interest of all stakeholders (Adams et al. 2011). Levi et al. (2014) show that the presence of women helps to create shareholder value because they seem to be less devoted to building economic empires, which in most cases are realised with the wasteful overconsumption of corporate resources, and thus allow companies to save resources that could be used in profitable investment projects.

However, some scholars believe that excessive monitoring of management may result in a reduction of shareholder value (Almazan and Suarez 2003). Consistent with this perspective, Adams and Ferreira (2009), despite empirically verifying that gender diversity is positively related to the effectiveness of the board, find a negative relationship between the diversity of the board and corporate performance due to the over-monitoring carried out by women. They explain that the impact of gender diversity may depend on shareholder rights. In fact, in further econometric analyses, they show that female directors have a positive effect only in firms characterised by weak shareholder rights, where the monitoring role could be a useful resource in improving firm value. Moreover, Adams and Ferreira (2007) observe that the greater interference of the directors in the decision-making process could give rise to communication difficulties among administrators. In this case, gender diversity, which is a new element within the board, may create disagreements among the directors, which could affect performance. Ahern and Dittmar (2012) find that the imposition of a mandatory quota of women on the board of Norwegian companies results in a lower value of the company. They attribute these results to the fact that companies are forced to designate women who, in some cases, have no experience as an administrator, so they do not possess special skills that could generate benefits for the firms. On the contrary, their operational limits create slow and unproductive decision making that has a negative impact on business performance.

A second perspective that may be used to explain the role of female directors on boards is resource dependency theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). In this view, female directors bring unique skills, valuable resources and useful networks to the board, contributing to enhancing the decision-making capabilities of the firm. Hillman et al. (2007) study the features of female directors with respect to resource dependence theory and find that gender diversity improves the quality of board decisions. In line with resource dependence theory, Torchia et al. (2011) suggest the importance of increasing the number of women on boards of directors to benefit from diversity in value, backgrounds and abilities. A recent study of Terjesen et al. (2015) based on a multi-theoretical explanation states that female directors enhance boards of directors’ effectiveness, especially due to their creativity and innovation with respect to problem solving. Additionally, Huse and Grethe Solberg (2006) highlight the beneficial effects on business performance that may originate from different female perspectives and experiences. Women can make positive contributions on corporate boards, as they can add value by providing new ideas and different perceptions compared to all-male boards.

Resource dependence theory draws attention to the beneficial effects of gender-diverse boards. The provision for female representatives on the board provides better human capital resources to support top managers with valuable advice and counsel (Anderson et al. 2011; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Terjesen et al. 2009).

Concerning the role of women in family businesses, a recent study by Bianco et al. (2015), involving a sample of Italian firms, shows that 55% of female directors who sit on the boards of family businesses are members of the family that controls the company. The criteria used to choose women as board members in family firms are likely to be different from those in other firms, so that management skills and experience may not be the main decision criteria. Therefore, they are less likely to introduce new ideas or new networks in the company’s board and can thus not improve firm value. In contrast, if the women are not family members and are chosen on merit and professional expertise, they may represent new human capital and could bring new perspectives to the family business, helping to increase the efficiency of the board.

Therefore, on the basis of these considerations, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H5a

Female directors affect firm value.

H5b

Female directors affect non-family firms more positively than family firms.

Table 1 provides a summary of the relationship between board characteristics and firm value predicted by three theories cited in the research hypotheses. Although the theories prescribe a different role for each governance characteristic, there is a common vision for the capability of board characteristics to affect firm value.

3 Sample and data

3.1 Sample

For our study, we use a sample of industrial firms listed on the Italian stock exchange in Milan and included in Datastream for the period 2003–2013 (11 years). We exclude banks and other financial institutions because government regulations potentially affect firm performance (Anderson and Reeb 2003). The process of selection of the sample starts, in order to avoid bias in the estimates, by eliminating outliers. Through a process of winsorizing, the extreme values of all the variables were replaced by the data present at the 1 and 99% percentiles. In addition, firms for which the data of corporate governance is not available were excluded. Therefore, the final sample consists of 1613 observations and 193 firms. The data on the structure of corporate boards were collected manually by referring to the annual reports on corporate governance of the individual firms, available on the official websites and on the website of the Italian Stock Exchange.

3.2 Definition of family firm

The literature on family business is wide-ranging and it is difficult to find consensus on the exact definition of a family firm (Miller et al. 2007). However, almost all the researchers agree with the opinion that family business is characterized as an organization controlled and usually managed by multiple family members. Therefore, according to Andres (2008) we define a company as family firm when it meets at least one of the following two criteria: (a) the founder and/or family members hold more than 25% of the shares, or (b) if the founding family owns less than 25% of the shares, the family is represented on either the executive or the supervisory board.

Nevertheless, this definition of family firm does not permit to capture empirically the differences between family involvement in top managerial positions and family without board representation. To analyse both aspects, following Chen and Nowland (2010) we break down family-owned firms into two sub-categories concerning the involvement or not of the family in the management: family less involved, when the family does not hold both the Chairman and CEO positions, and family more involved, when the same family member hold both the CEO and Chairman positions.

3.3 Dependent variable

The financial variables are defined as follows. Referring to some previous studies (Chen and Nowland 2010; Ahern and Dittmar 2012), the variable used to measure firm value is Tobin’s Q scaled by total assets. It is measured by the ratio of the book value of total assets minus the book value of equity plus the market value of equity to the book value of assets.

3.4 Corporate governance variables

In order to test the research hypotheses, the study uses five variables on the board of directors: CEO duality, dummy variable that takes a value equal to 1 if the CEO is also the chair of the board, otherwise, it is equal to 0; the presence of independentFootnote 1 and busy directors, identified by the ratio of independent directors and number of directors on the board with more than three positions in other firms on the total number of directors respectively; board size, which is the total number of members who sit on the board of directors; gender diversity, the ratio between female directors and the board size.

3.5 Control variables

In addition to the above-mentioned variables, to check the firm-specific effects, we introduce into our analysis some control variables to evaluate clearly the effect of governance variables. Based on previous papers (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Villalonga and Amit 2006; Andres 2008), we have included the following variables: cash holdings, size, leverage, sales growth, cash flow and dividend. Cash holdings is the amount of liquidity in the firm. It is calculated as the availability of cash and cash equivalents to total assets. Size is measured as the logarithm of total assets. Leverage is calculated as the total debt divided by the total assets of the firm. Sales growth takes into account the firm’s growth opportunities and is measured by the rate of sales growth. The cash flow is derived from the ratio of cash flow from operations to total assets. The dividend is the amount of profits distributed to shareholders in the year and is measured by total dividend to total assets. According to Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007), firms with more cash are expected to have higher value, while leveraged firms, as illustrated in many studies (Villalonga and Amit 2006; Andres 2008), are likely to have lower value. Sales growth are estimated to cause higher long-term profit (Lee 2009). About dividend, following Pinkowitz et al. (2006), we predict high current levels of dividends are related to lower consumption of private benefits, hence higher firm value. High cash flow allows positive NPV projects to be financed and growth opportunity seized without requiring external funding, therefore we expect a positive relationship between cash flow and firm value. Finally, since the various theories and several empirical studies show conflicting results about the of the size on firm value, we avoid from predicting the direction of its effect on the value of the firm.

3.6 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents two panels of descriptive information for our sample of firms. Panel A provides means, medians, standard deviations, and first and third quartiles for all the variables in our sample. Panel B shows the results of difference of means tests between family and non-family firms.

Panel A of Table 2 presents the main statistics for the sample of firms analysed. With reference to board characteristics, the results show that, on average, the CEO is also the Chairman of the board in 24% of cases. The average percentage of independent directors on the boards is 39%. The directors with more than three assignments in other boards of directors are, on average, 34% of all directors. The average board is comprised of 9–10 members, indicating that Italian companies tend to adopt relatively small boards. Finally, the presence of the female gender represents approximately 9% of the total directors. This percentage, which is very low, especially in comparison with Northern European countries, has increased considerably following the approval of Law 120/2011 on female quotas which required the presence of women within the boards of Italian listed firms. Family firms represent, on average, 75% of the total companies. Of these, 15% do not have family members in the role of CEO and Chairman. Family CEO duality is, on average, in 34% of family businesses.

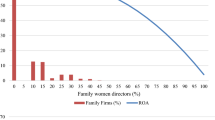

Panel B shows difference of means for variables between family and non-family firms. Family firms represent 75% of our sample. Board of directors characteristics are the key variables of the study and are shown in rows 8–12. With respect to CEO duality, we find little difference in the univariate analysis between family (25%) and non-family firms (23%). Diversely, independent directors significantly differ between family (36%) and non-family firms (46%). Family firms do not appear to involve busy directors differently than non-family firms. In fact, both types of firms have the same percentage of busy directors in the boards (34%). Board size of family firms are, on average, smaller than non-family firms. The average number of members in family firms is 9.28 compare with 10.45 of non-family firms. Finally, we note that female directors are more prevalent in family firms (9%) than in non-family firms (6%).

Table 3 shows the level of correlation among the variables used in the econometric analysis. The findings show tolerable levels of correlation between all the variables of the empirical models. In addition, we computed VIF values among all the independent variables employed in our models. The results of this analysis indicate that VIF values present a maximum value of 1.75. This evidence shows that problems of correlations due to multicollinearity are negligible.

4 Empirical analysis

To test the role of the board in determining firm value, the following empirical model is applied.

In previous studies, the relationship between corporate governance variables and firm performance has been examined through the model of ordinary least squares (OLS). However, the use of OLS models can be problematic in the case of panel data because they consider data to be cross-sectional, thus ignoring the specific structure of panel data (Gujarati and Porter 2009; Kohler and Kreuter 2009; Roodman 2009). The estimates based on the least squares (OLS) may be distorted, and to avoid problems of heterogeneity, a fixed effects panel model is applied.Footnote 2 In addition, considering that governance and firm value are endogenously determined (Himmelberg et al. 1999; Hermalin and Weisbach 2003; Adams and Ferreira 2009), the system of generalized method of moments (GMM) is applied to test how robust the results are to any problems of endogeneity.

The most common empirical technique to check for endogeneity is two-stage least squares. Unfortunately, finding a good exogenous instrument for governance variables is difficult (Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith 2007; Adams and Ferreira 2009). Therefore, the best is considered to be the System GMM of Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998). GMM allows us to solve the problem of the endogeneity of the variables related to the board of directors by using as instruments lagged differences and lagged levels of dependent and independent variables (Roodman 2009).Footnote 3

Table 4 reports the results of the analysis that examines the effectiveness of board composition in determining firm value in the total sample of companies. Specifically, column (1) shows the results obtained from the fixed effects panel model, whereas column (2) presents the findings originated from generalised method of moments.

In general, the estimated coefficients of the control variables are in line with those previously hypothesised. We find that firm value is positively related to cash holdings, cash flow and dividend. Meanwhile, we find a negative relationship between firm value and both leverage and size. There is no relationship between sales growth and firm value.

The results reported in column (1) of Table 4 do not confirm hypothesis H1a because the coefficient of the dummy variable CEO duality is not statistically significant (β = 0.0267, s.e. = 0.0296). The empirical results show that the concomitant role of the CEO and chairman of the board has no significant effect on firm value. Similarly, the coefficient of independent directors is not statistically significant (β = −0.0965, s.e. = 0.0778). Therefore, the presence of independent members on the board does not seem to influence the market value of the company. The results on the effect of the presence of busy directors on firm value show a positive and statistically significant sign (β = 0.138, s.e. = 0.0536) of the busy directors variable at a confidence level of 1%. The findings indicate that firm value is higher in companies where there is a greater presence of members with appointments in other companies. The results supports the dominance of the benefits of reputational effect (Jiraporn et al. 2009) compared to the disadvantages provided by the view that directors who sit on many boards of directors tend to spend less time in each firm, neglecting their supervisory duties and creating agency problems. Fama and Jensen (1983) and Carpenter and Westphal (2001) argue that directors who sit on multiple boards simultaneously contribute to the development of skills and experiences. Based on this view, their presence can be positively associated with firm value. Administrators with considerable cultural and business backgrounds can initiate strong actions in support of the interests of all shareholders, minimising opportunistic behaviour of the CEO and avoiding the misuse of resources. In considering hypothesis H4a, with regard to the implications of the size of the board of directors on corporate value, the estimated coefficient of the variable board size has a positive and statistically significant value (β = 0.0170, s.e. = 0.00604). The results confirm full support of the perspective that perceives directors who sit on numerous boards of directors as more efficient and able to better supervise managers and discourage their fraudulent behaviour. Likewise, unlike what was expected, the variable for female directors was not found to be statistically significant (β = −0.122, s.e. = 0.140), and thus, the presence of women in top management does not seem to affect firm value.

The previous results, also applying GMM system, are confirmed in column (2) of Table 4. However, the consistency of the GMM estimations depends critically on the absence of second-order serial autocorrelation. To test whether the system GMM approach is valid, we calculate first and second order correlation tests (AR1 and AR2). The Arellano-Bond test developed by Arellano and Bond (1991) shows the lack of problems of serial correlation of the second order. Consequently, the GMM estimation is valid.Footnote 4

5 The role of board of directors in family and non-family firms

Despite the results showing a clear effect of the structure of the board of directors on firm value, it is possible that the relationship could be affected by family control. The different performance between family and non-family firms shown in the literature can be derived from diverse corporate governance structures adopted by family firms compared to non-family firms (Bartholomeusz and Tanewski 2006). Moreover, Corbetta and Salvato (2004b) note dissimilar agency costs between family and non-family firms, and Minichilli et al. (2015) explain how family shareholders bring knowledge and a variety of opinions to the firms and are therefore a valuable resource to help the CEO manage the firm.

To estimate the influence of board structure on the value of both family and non-family firms, we split the sample between family and non-family firms based on the above definition of a family firm.

Table 5 shows the results related to the effectiveness of the board in determining business value in family and non-family firms.

The results in column (1) regard the sub-sample of non-family firms, whereas the empirical findings present in column (2) refer to the sample of family firms. The comparison of the coefficients of the variables allows us both to show the different role of board in family and non-family firms and to clarify the theory that best applies to family firms. These analyses are estimated by using a fixed effects model.

The coefficient of CEO duality is not statistically significant in non-family firms (β = −0.0998, s.e. = 0.0644), but it is positive and statistically significant in family firms (β = 0.0652, s.e. = 0.0339). The results suggest that the condition of CEO duality results in improved value in family businesses. It seems that the family, as a controlling shareholder, safeguards the efficiency of management and supports the company rather than using its dominant position for opportunistic purposes at the expense of firm value. The different evidence, compared to non-family firms, can be due to the alignment of interests between management and ownership, given that in most cases, family members hold positions in the company or the family who owns the company has superior control of the external management and are particularly interested in protecting their interests. The family has a strong incentive to control and monitor managers’ activities to avoid opportunistic behaviours (Audretsch et al. 2013). Thus, family firms have an advantage in monitoring and disciplining agents’ decisions. When the CEO is also chairman of the firm, there will be no expropriation of shareholder wealth through the consumption and misallocation of resources, and agency costs are minimal (Fama and Jensen 1983), with benefits in terms of better business value for all shareholders. According to these results, we can accept hypothesis H1b, which predicts that CEO duality affects family firms more positively than non-family firms.

Referring to the proportion of independents on the board, we do not find a significant relationship between independent directors and firm value. The coefficient of the variable independent directors is not statistically significant in either non-family (β = −0.107, s.e. = 0.133) or family firms (β = −0.0428, s.e. = 0.0994). Thus, hypothesis 2b is not supported. Contrary to the predictions of agency theory, these results do not support the assumption that independent directors have an important monitoring role of CEOs, so they can improve firm value. At the same time, the stewardship theory perspective, which describes the independent directors as valuable members of the board to support the management of the firm, is not confirmed.

The variable for the presence of busy directors is not statistically significant in non-family firms (β = 0.464, s.e. = 0.106), but it is positive and statistically significant in family firms (β = 0.175, s.e. = 0.0637). The effect of busy directors is different in family firms compared to non-family firms. Busy administrators appear to be able to increase the value of family firms. They improve decision-making processes of the board through in-depth knowledge arising from the multiple experiences that characterise their curriculum. Furthermore, the family company may benefit from their substantial contacts, arising from membership in various contexts, to start or be integrated into advantageous investment transactions that increase the value of the firm. These findings support hypothesis H3b, which established that busy directors affect family firms more positively than non-family firms.

With respect to the size of the board, the effect on firm value is also different for the two types of firms. Differently from previous variables, the coefficient of board size is positive and statistically significant in non-family firms (β = 0.0258, s.e. = 0.0118), while it is not statistically significant in family firms (β = 0.0116, s.e. = 0.00754). These empirical results permit us to state that increasing the size of the board leads to superior value only in non-family firms. Consequently, we cannot support the hypothesis H4b, which specified that board size affects family firms more positively than non-family firms. Although the results in the literature show a predominantly negative relationship between large boards and performance, our findings show that board size positively affects the value of non-family firms. Considering that agency costs are more important in non-family firms than in family firms (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Chrisman et al. 2004), according to the predictions of agency theory, the members of the boards of non-family firms are particularly vigilant regarding management operations. Under this view, the ability of the board to monitor can increase as more directors are added, and it is more difficult for them to be dominated by CEOs (Jensen 1993). In addition, board members provide advice and support to the top managers, representing a valuable resource for corporate boards (Donaldson and Davis 1991).

However, our definition of family firms does not distinguish between family firms with members involved in management and family firms without managerial participation. Previous studies suggest that firms with family management may have different impacts on firm value (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Maury 2006; Miller et al. 2007; Villalonga and Amit 2006). Therefore, as mentioned above in defining family firms, the sample of family firms was split into two sub-samples, respectively called family less involved, when family members do not hold both the chairman and CEO positions, and family more involved, when the same family member holds both the CEO and chairman positions. We tested independently the specified model for each of the two sub-samples. The results of the panel data estimation are displayed in columns (3) and (4).

In column (3), considering family firms with members just involved in ownership, contrary to expectations, the coefficients of the variables of the board are not statistically significant. Therefore, in family businesses that do not have a direct presence in the bodies of corporate governance, improvements in business value were not found. The effect of board characteristics on value is very similar between non-family firms and family firms where the family is not involved in management. This result is particularly interesting. Family shareholders, even if relevant, that externalise the management of the company to managers who are not family decided not to “live” the business every day. Therefore, their involvement may be limited to supervising the management. The members of the board of directors, which include some family members, simply verify the execution of the tasks assigned to management by the relevant family shareholders. It seems that the functions of the board in this type of family firm are situated not at the board but at family gatherings and family councils (Siebels and zu Knyphausen-Aufseß 2012).

Diversely, in the sub-sample of family firm in which the family is involved in management, the coefficients of the variables CEO duality (β = 0.102, s.e. = 0.0482) and busy directors (β = 0.209, s.e. = 0.104) are confirmed to be positive and statistically significant, both at the significance level of 5%. Moreover, the coefficient of the variable for female directors that in both non-family and family firms (considering the general definition) was not statistically significant now has statistical significance.

The presence of women on the board of the company is negatively related to firm value. The coefficient of the female directors is negative and statistically significant (β = −0.441, s.e. = 0.248). This result may be explained in two different ways. On the one hand, the negative effect may be ascribed to the different magnitude of business experiences (Hillman et al. 2002). Terjesen et al. (2009), in their study based on the human capital of women, suggest that female directors are similar to men in terms of several important abilities but are less likely to have experience as business experts. In line with this study, Ahern and Dittmar (2012), who in their study on a sample of Norwegian companies find a negative relationship between gender diversity and performance, attribute these negative results to the lack of experience and special managerial skills (features that could create value for companies) of female directors. On the other hand, another interesting perspective indicates that too much board monitoring can decrease shareholder value (Almazan and Suarez 2003; Adams and Ferreira 2007). This point of view is confirmed by Adams and Ferreira (2009). In fact, although they find that boards with more female directors are characterised by better attendance compared to those with male directors, strong monitoring of the CEO and alignment with the interests of shareholders, their empirical findings show that female directors could decrease firm performance due to over-monitoring.

6 Conclusion

The present paper analyses the impact of boards of directors’ characteristics on the value of family and non-family firms. With this study, we try to expand the current knowledge about corporate governance and to shed further light on differences between boards of directors in family and non-family firms.

The main results of this study, concerning the comparison between the characteristics of the board of family and non-family businesses, allow the deduction of interesting conclusions and identify the theories that best illustrate the role of the board in family businesses. In fact, although the literature on boards of directors in family firms has primarily focused on agency problems, our study confirms the point of view of previous studies (Chrisman et al. 2003; Corbetta and Salvato 2004a) that highlight the need to apply a multi-theoretical approach.

Indeed, contrary to the predictions of agency theory, we find that both CEO duality and busy directors positively affect family firm value, while independent directors do not seem to be useful for solving agency problems in family firms. The only empirical result congruent with the agency perspective concerns the effect of board size on the value of non-family firms. Additionally, the impact of gender diversity on firm value seems in part to conflict with the vision of agency theory.

Our empirical evidence shows that the condition of CEO duality in family-controlled firms can increase their value. In contrast to the sub-sample of non-family firms, CEO duality positively affects the value of family firms. Family shareholders seem to use their power not for opportunistic purposes but rather to safeguard the efficiency of management and support the growth of business value.

Comparing the two sub-samples of family firms, that is, less and more involved family firms, the positive effect is found only in family firms where the double role of CEO and chairman is held by the same family member. On the contrary, in family businesses that do not have direct involvement in management, the positive effect is non-existent. This dissimilar result between the two different sub-samples of family firms allows us to conclude that family CEO duality represents an added value for the company. The convergence of the dual role of CEO and chairman in the hands of a family member not only diminishes conflicts between managers and controlling shareholders that generate relevant agency costs but actively contributes to the growth and development of the company. The positive influence of family managers is in line with the stewardship perspective and the findings of Miller et al. (2008), who conclude that they aim to assure corporate longevity and to create strong relationships with clients to sustain the firm.

Additionally, the effect of busy directors on firm value is different between non-family and family firms. Specifically, busy directors positively influence the value of family firms. They are good stewards and valuable assets for companies due to their expertise, reputation and business contacts. For these features, finance researchers state that busy directors are preferred due to their exceptional advisory and managerial ability that allows them to enhance the board’s role in quality.

Diversely, board size influences the value of non-family firms. It seems that there is a prevalence of the benefits of the effective control of managers on the costs arising from a slow decision-making process typical of a large board of directors. The result is consistent with the model of Harris and Raviv (2008), which suggests that a larger board will provide optimal monitoring in the presence of managers who operate in firms where there are real opportunities to consume private benefits at the expense of shareholders. Compared to family firms, non-family firms are likely managed by external professional CEOs. Therefore, increasing the size of the board may help to better control their managerial operations and avoid satisfying personal desires.

Lastly, contrary to our expectations, gender diversity on boards negatively affects the value of family firms with families involved in management. Because it is mandatory for firms to hire female directors, there is a risk of selecting administrators with managerial limits, leading to slow and unproductive decision making that has a negative impact on business value (Ahern and Dittmar 2012). An alternative explanation can be derived from the study of Adams and Ferreira (2009), who find that female directors improve board effectiveness but have a positive impact, employing a strong monitoring of management, only on the value of firms with weak governance.

The major findings of the study are not consistent with the interpretation that the board of directors reduces the value of the firms through agency problems. On the contrary, the results may be explained using stewardship theory and resource dependence theory, which consider the members of the board as economic agents who are not just interested in business aspects but often act with altruism for the benefit of the whole organisation and its stakeholders (Davis et al. 1997; Donaldson and Davis 1991), able to bring human and relational resources to the firm (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). The administrators totally identify with the family (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006). Therefore, according to this point of view, the main role of the board of directors is to advise and support management rather than monitor them as agency theory recommends (Daily et al. 2003; Corbetta and Salvato 2004a).