Abstract

Introduction

Breastfeeding has significant health benefits for infants and birthing persons, including reduced risk of chronic disease. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for 6 months and recently extended its recommendation for continuing to breastfeed with supplementation of solid foods from one to two years. Studies consistently identify lower breastfeeding rates among US infants, with regional and demographic variability. We examined breastfeeding in birthing person-infant pairs among healthy, term pregnancies enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study between 2010 and 2017 (n = 1176).

Methods

Birthing persons 18–45 years old were enrolled during prenatal care visits at ~ 24–28 weeks gestation and have been followed since enrollment. Breastfeeding status was obtained from postpartum questionnaires. Birthing person and infant health and sociodemographic information was abstracted from medical records and prenatal and postpartum questionnaires. We evaluated the effects of birthing person age, education, relationship status, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain (GWG), smoking and parity, and infant sex, ponderal index, gestational age and delivery mode on breastfeeding initiation and duration using modified Poisson and multivariable linear regression.

Results

Among healthy, term pregnancies, 96% of infants were breastfed at least once. Only 29% and 28% were exclusively breastfed at 6-months or received any breastmilk at 12-months, respectively. Higher birthing person age, education, and parity, being married, excessive GWG, and older gestational age at delivery were associated with better breastfeeding outcomes. Smoking, obesity, and cesarean delivery were negatively associated with breastfeeding outcomes.

Conclusions

Given the public health importance of breastfeeding for infants and birthing persons, interventions are needed to support birthing persons to extend their breastfeeding duration.

Significance

What is already known? The benefits of breastfeeding to child and birthing person health are well-documented, however, rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration continue to fall short of health-based guidelines. Regional differences exist and certain rural New England states tend to have amongst the highest breastfeeding rates in the US.

What this study adds? This study of n = 1176 birthing persons-infant pairs enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study, a rural, general population pregnancy cohort, suggests that factors influencing breastfeeding outcomes align closely with studies conducted in urban settings and using nationally-representative surveys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is recognized by leading pediatric (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, AAP) and public health (e.g., World Health Organization, WHO; US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC) organizations as important to optimize short- and long-term child and birthing persons health (AAP, 2020; CDC, 2020b; UNICEF, 2015; WHO, 2020). Benefits of breastfeeding occur irrespective of socioeconomic status, improving infant and birthing persons health in low-, middle-, and high-income countries, alike (Victora et al., 2016) and have been reviewed previously (Eidelman & Schanler, 2012; Gartner et al., 2005; Salone et al., 2013; Victora et al., 2016). At the time of this study, the AAP and WHO recommended exclusive breastfeeding until infants are six months old, and continued breastfeeding with solid food supplementation until at least 12 months old (“heath-based guidelines”) (AAP, 2020; Eidelman & Schanler, 2012; Gartner et al., 2005; WHO, 2020). Current health-based guidelines extend recommendations for supplemental breastfeeding until children are two years old (Meek & Noble, 2022). Breastfeeding rates in many parts of the world, including high-income countries, fall short of these guidelines (CDC, 2020b, 2022). Since breastfeeding guidelines are health-based, low initiation and shorter duration of breastfeeding can pose risks to child and birthing person wellbeing, which may not be replaceable by infant formula and access to high-quality medical care.

Understanding risk factors that predict early cessation is important for developing interventions that promote breastfeeding. Prior studies have identified complex, multifactorial patterns associated with reduced breastfeeding duration in high-income countries (e.g., Cohen et al., 2018; Henninger et al., 2017; Kehler et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2006; Wallwiener et al., 2016). For example, factors such as younger birthing person age, belonging to certain racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Black), lower educational attainment, smoking, higher pre-pregnancy body mass index (ppBMI), cesarean delivery, pregnancy complications, (e.g., pre-term delivery, time in the neonatal intensive care unit), and postpartum work are associated with reduced rates of breastfeeding initiation and/or early cessation (e.g., Amiel Castro et al., 2017; Beauregard et al., 2019; Cohen et al., 2018; Kehler et al., 2009; Lutsiv et al., 2013; Maastrup et al., 2014; Scott et al., 2006; Steurer, 2017). However, this information is compiled from studies conducted in numerous countries and public policy and cultural differences may influence national breastfeeding patterns (Galtry, 2003; Lubold, 2019). Furthermore, regional and local breastfeeding rates vary and studies based on nationally-representative surveys and/or urban populations may not be generalizable to rural settings (e.g., CDC, 2022; Scott et al., 2006; Stough et al., 2019; Wallwiener et al., 2016).

We evaluated predictors of breastfeeding among 1176 birthing person-infant pairs enrolled in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS), a rural, general population pregnancy cohort, between 2010 and 2017.

Methods

New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS)

The NHBCS is a prospective, rural pregnancy cohort, based in New Hampshire (NH), designed to examine associations of arsenic and other exposures via private drinking water wells with perinatal health and childhood development. An estimated 46% of NH residents receive their drinking water from private water supplies (NHDES, 2018). Birthing persons ages 18–45 years were recruited for enrollment into the NHBCS at prenatal care visits at approximately 24–28 weeks gestation. Eligible birthing persons were receiving prenatal care for a singleton pregnancy at one of the study clinics in either Lebanon or Concord, NH and lived in a household served by a private water system, defined according to state and federal Safe Drinking Water Acts (SDWAs) as systems serving fewer than 15 connections or less than 25 people. Birthing persons needed to plan to live in the same place from their last menstrual period through delivery. NHBCS research was approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board and all birthing persons provided written, informed consent prior to enrollment.

Predictors

We selected predictors a priori based on previous research demonstrating their influence on breastfeeding outcomes. Predictor information was obtained through birthing person self-report questionnaires, measurements made by trained study personnel, and abstraction from birthing person and infant medical records. Detailed medical and personal histories were provided by birthing persons at enrollment, including age, race and ethnicity, education, relationship status, smoking history, ppBMI, and parity. Gestational weight gain (GWG), cardiometabolic complications of pregnancy (hypertension/preeclampsia, gestational diabetes), delivery mode, and gestational age at delivery were obtained from birthing person medical records. Pre-pregnancy BMI was categorized as normal, overweight or obese (CDC, 2020a), and GWG was categorized as limited, adequate or excessive (IOM, 2009). Infant sex and birth weight and length were obtained from infant medical records. Infant weight and length were used to calculate ponderal index, a measure of leanness in newborns: [birthweight (kg)/[birth length (m)]3 (Landmann et al., 2006).

Breastfeeding Outcomes

Birthing persons completed questionnaires every four months in the first year postpartum, then every six months up to five years. Birthing persons were asked about the age at which they last breastfed their infant and introduced any non-breastmilk supplementation (infant formula, solid food, juice, water) into their infant’s diet. We derived variables of breastfeeding initiation, and “exclusive” and “any” breastfeeding duration based on this information (AAP, 2020; WHO, 2020). Breastfeeding initiation was defined as a birthing person putting their infant to their breast at least one time. “Exclusive” breastfeeding duration was defined as the age (months) when an infant received their first supplementation of non-breastmilk foods or liquids, including water (WHO, 2019). The WHO regards only medically recommended supplementation (oral rehydration solutions, vitamins, minerals, and medicines) as compliant with the definition of exclusive breastfeeding. “Any” breastfeeding duration was defined as the age (months) when an infant last received breastmilk.

Statistical Analyses

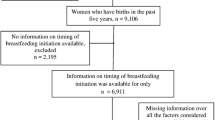

To date, more than 3000 birthing person-infant pairs have been enrolled into the NHBCS. To evaluate predictors of breastfeeding outcomes among this cohort, we restricted to birthing persons enrolled between 2010 and 2017 for whom breastfeeding data were available (n = 1337). We excluded birthing persons who had pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), preeclampsia, and preterm delivery (≤ 37 weeks gestation) since cardiometabolic pregnancy complications and preterm delivery are strong predictors of adverse breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., Åkerström et al., 2007; Cordero et al., 2012; Demirci et al., 2018; Guelinckx et al., 2012). In total, we evaluated breastfeeding among 1176 birthing person-infant pairs.

We calculated descriptive statistics for all predictors and breastfeeding outcomes. Predictors were selected a priori based on factors previously observed to influence breastfeeding initiation and duration. All models included birthing person age at enrollment (continuous), highest level of education (ordinal categorical), parity (ordinal categorical), marital status (binary), smoking status (categorical), ppBMI (continuous or categorical), GWG (categorical), delivery method (binary), gestational age at delivery (continuous), infant sex (binary), and infant ponderal index (continuous). To assess predictors of breastfeeding initiation, we used modified Poisson regression with robust standard error (Zou, 2004) to estimate the relative risk (RR) of never breastfeeding associated with each predictor, adjusted for other predictors, including ppBMI as a continuous variable, in the multivariable models. When evaluating predictors of breastfeeding duration, we further restricted our analyses to birthing persons who had ever breastfed (96%; n = 1124). Using modified Poisson regression, we evaluated predictors of exclusive breastfeeding duration at six months and any breastfeeding at 12 months, adjusted for other predictors. We evaluated exclusive and any breastfeeding duration as continuous outcomes using multivariable linear regression. All regression models for exclusive and any breastfeeding outcomes included ppBMI as a categorical variable. We did not evaluate race/ethnicity as a predictor of breastfeeding outcomes because > 97% of birthing persons participating in the NHBCS identify as non-Hispanic white. Statistical significance was evaluated using 95% confidence intervals (CI) for RR estimates from modified Poisson and beta coefficients from multivariable linear regression models, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1.

Results

The 1176 birthing persons in the analytic population were predominantly non-Hispanic White (97.1%), educated (70.1% had a Bachelor’s degree or higher), and older (mean ± SD: 31.4 ± 4.8 years) (Table 1). Most birthing persons were married (85.9%), parous (58.2%), and tended to have good pre-pregnancy health indicators, including no current or prior smoking (87.2%) and relatively healthy ppBMI (25.6 ± 5.6) (Table 1). However, roughly half of birthing persons had excessive GWG (55.9%) (Table 1). Most birthing persons delivered vaginally (71.1%) at full term (39.4 ± 1.1 weeks gestation) and infants were evenly divided by sex (Table 1). Measures of infant anthropometry also reflected healthy, term pregnancies, weighing 3.4 ± 0.6 kg and measuring 50.6 ± 2.9 cm in length (Table 1).

Breastfeeding Initiation

Almost all birthing persons (95.6%; n = 1124) breastfed their infant at least once (Table 2). Birthing persons with a Bachelor’s degree were 1% more likely to breastfeed than those who had attended some college but had not earned a Bachelor’s degree (RR; 95% CI: 1.01; 1.01, 1.02) (Table 3). Married birthing persons were 3% more likely to initiate breastfeeding compared to those who were unmarried (1.03; 1.00, 1.06) and for each additional week of gestation, likelihood of breastfeeding initiation increased by 1% (1.01; 1.00, 1.01) (Table 3). Breastfeeding initiation was similar among people delivering by cesarean section and vaginally (0.99; 0.96, 1.01) (Table 3).

Breastfeeding at Health-Based Guidelines

Among birthing persons who initiated breastfeeding in our study, 28.9% (n = 239) exclusively breastfed until their infant was six months old and 28.1% (n = 312) were still breastfeeding at least sometimes at 12 months, the health-based guidelines at this time (Table 2). Positive predictors of breastfeeding at health-based guidelines include education, parity, being married, and excessive GWG, whereas smoking, obesity, and cesarean delivery were negatively associated with breastfeeding. Specifically, for each additional prior child, a birthing person was 4% (1.04; 1.01, 1.07) more likely to exclusively breastfeed their infant enrolled in the current study at six months, and 3% (1.03; 1.00, 1.05) more likely to continue any breastfeeding to 12 months (Table 3). Married birthing persons were 10% (1.10; 1.02, 1.19) more likely to breastfeed exclusively at six months than those who were unmarried (Table 3). Birthing persons with a Bachelor’s degree were 5% (1.05; 1.02, 1.08) more likely to breastfeed at 12 months than those who had some college education but whom had not earned a Bachelor’s degree and individuals with excessive GWG were 6% (1.06; 1.01, 1.12) more likely to breastfeed at 12 months than those with adequate GWG (Table 3). By contrast, birthing persons who were obese prior to pregnancy (ppBMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) were 12% (0.88; 0.82, 0.94) and 10% (0.90; 0.84, 0.96) less likely to continue exclusive and any breastfeeding until six and 12 months, respectively, than people with normal ppBMI (< 25 kg/m2) (Table 3). Birthing persons who currently smoked were 17% (0.83; 0.76, 0.90) less likely to exclusively breastfeed at six months versus never smokers, and birthing persons who delivered via cesarean section were 5% (0.95; 0.90, 1.00) less likely to continue breastfeeding until 12 months than those who delivered vaginally (Table 3). Infant characteristics did not predict breastfeeding in accordance with health-based guidelines at six or 12 months.

Breastfeeding Duration

Birthing persons who exclusively breastfed did so for an average of 3.9 months (SD ± 2.4) (Table 2). Birthing persons continued any breastfeeding for an average of 9.2 ± 7.5 months (Table 2). Several factors were associated with longer exclusive and any breastfeeding duration. For each prior child, parous individuals exclusively and any breastfed for 0.44 (95% CI: 0.27, 0.62; Fig. 1) and 1.15 (0.64, 1.66; Fig. 2) months longer, respectively. Higher education was associated with longer exclusive (Beta: 0.26 months; 95% CI: 0.06, 0.46; Fig. 1) and any (0.83 months; 0.25, 1.42; Fig. 2) breastfeeding. Being married was also associated with longer exclusive breastfeeding (0.57 months; 0.02, 1.13) relative to birthing persons who were unmarried (Fig. 1). For each additional year of age at enrollment, birthing persons continued any breastfeeding for an extra 0.17 (0.05, 0.28) months (Fig. 2). Similarly, a number of factors were associated with shorter exclusive and any breastfeeding duration. Current and former smokers exclusively breastfed for 1.44 (−2.30, −0.58) and 0.76 (−1.48, −0.05) fewer months, respectively, compared to those who never smoked (Fig. 1). People who were overweight (−0.53 months; −0.92, −0.14) and obese (−1.29 months, 95% CI:−1.74, −0.84) prior to pregnancy exclusively breastfed for less time than those with normal ppBMI (Fig. 1). Similarly, overweight and obese birthing persons continued any breastfeeding for 1.35 (−2.49, −0.21) and 2.37 (−3.70, −1.04) fewer months, respectively, than those with a normal ppBMI (Fig. 2). Birthing persons who delivered via cesarean section breastfed for 1.14 (−2.21, −0.06) fewer months than those who delivered vaginally (Fig. 2). Infant characteristics did not predict duration of exclusive or any breastfeeding in our study.

Adjusted multivariable linear regression estimates (beta ± 95% CI) of predictors of exclusive breastfeeding duration. Betas (•) and 95% confidence intervals for birthing person and infant characteristics. The vertical line represents the null and points located on this line denote the reference level for categorical variables (e.g., never smoker vs. current smoker). Predictors with betas located to the left of the null are negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding duration, whereas predictors with betas located to the right of the null are positively associated. Green asterisks (*) and bold, italicized betas and 95% CIs reflect those predictors which are significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding duration among birthing persons in our study. BMI – pre-pregnancy body mass index; GWG – gestational weight gain

Adjusted multivariable linear regression estimates (beta ± 95% CI) of predictors of any breastfeeding duration. Betas (•) and 95% confidence intervals for birthing person and infant characteristics. The vertical line represents the null and points located on this line denote the reference level for categorical variables (e.g., never smoker vs. current smoker). Predictors with betas located to the left of the null are negatively associated with any breastfeeding duration, whereas predictors with betas located to the right of the null are positively associated. Green asterisks (*) and bold, italicized betas and 95% CIs reflect those predictors which are significantly associated with any breastfeeding duration among birthing persons in our study. BMI – pre-pregnancy body mass index; GWG – gestational weight gain

Discussion

Because breastfeeding is critical to optimal child and birthing persons health, health-based guidelines recommended exclusively breastfeeding infants until six months of age, followed by continued breastfeeding supplemented with solid foods until 12 months at the time of this study (AAP, 2020; Eidelman & Schanler, 2012; Gartner et al., 2005; WHO, 2020). Breastfeeding rates are generally high in NH compared to other parts of the US, with 37% of birthing persons exclusively breastfeeding at six months and 40% any breastfeeding at 12 months (CDC, 2022). By contrast, only 25% of infants born in the US in 2019 were exclusively breastfed at six months and only 36% received at least some breastmilk at 12 months (CDC, 2022). Breastfeeding outcomes among birthing persons enrolled in our study tracked closely with national trends and our results corroborate findings from prior studies among US birthing person-infant pairs (CDC, 2020b, 2022; Stough et al., 2019). Notably, among birthing persons enrolled in our study, age, education, parity, being married, excessive GWG, and gestational age at delivery were positively associated with improved breastfeeding outcomes (initiation and longer duration). Conversely, smoking, being overweight or obese, and cesarean delivery were negatively associated with breastfeeding outcomes. These findings provide insight into strategies for improving breastfeeding outcomes in rural settings.

Measures of higher socioeconomic status and a stable family structure, such as higher education and being married, were positive predictors of breastfeeding initiation and duration among NHBCS birthing persons as has been demonstrated in previous research (Ekstrom et al., 2003; Hackman et al., 2015; Heck, 2006; Kehler et al., 2009; Victora et al., 2016). Although birthing person age tended to be inversely associated with breastfeeding duration in other studies (e.g., Colombo et al., 2018; Kitano et al., 2016), we did not observe this relationship in our study.

We evaluated the role of ppBMI, GWG, and smoking status on breastfeeding initiation and duration to represent measures of overall birthing person health prior to and during pregnancy. Pre-pregnancy obesity was inversely associated with breastfeeding duration in all regression models for exclusive and any breastfeeding. Excessive GWG was associated with longer breastfeeding, whereas inadequate GWG tended to be associated with shorter breastfeeding. Collectively, these findings agree with prior literature suggesting that pre-pregnancy obesity, which is an important metric of overall birthing person health, adversely influences breastfeeding (Huang et al., 2019; Kehler et al., 2009), yet birthing persons who gain excessive weight during pregnancy may be motivated to breastfeed because of the perception that breastfeeding improves postpartum weight loss (Schalla et al., 2017). A history of smoking was also a risk factor for early breastfeeding cessation in all regression models for exclusive or any breastfeeding among birthing persons enrolled in our study, as has been previously reported (e.g., Mennella et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2006; Wallenborn & Masho, 2016).

Gestational age at delivery and delivery mode predicted breastfeeding initiation and duration in our study as has been reported previously (e.g., Hobbs et al., 2016; Lutsiv et al., 2013). While our analyses were restricted to term pregnancies (> 37 weeks gestation) and did not explore physiological mechanisms underlying breastfeeding initiation, pregnancy and lactation hormones offer possible insights into our findings. Levels of oxytocin and prolactin change in coordinated ways during the perinatal period to support childbirth and breastfeeding, yet may be adversely altered by natural early term delivery (37–39 weeks gestation) or delivery interventions (Buckley, 2015; Hill et al., 2009; Nissen et al., 1996; Parker et al., 1989; UvnäsMoberg et al., 2020). Consistent with literature documenting the benefits of vaginal delivery on breastfeeding outcomes (Hobbs et al., 2016; Moore et al., 2016; Prior et al., 2012), cesarean delivery was negatively associated with breastfeeding initiation and duration in all regression models in our study.

Though not all risk factors for adverse breastfeeding outcomes are modifiable, some identified in this and prior studies offer opportunities for interventions to improve breastfeeding among birthing persons at higher risk of not initiating or maintaining breastfeeding in accordance with health-based guidelines. Characteristics such as obesity, GWG, and smoking adversely impact breastfeeding duration and are already targets for clinical intervention to improve birthing person and child health; related initiatives will benefit breastfeeding outcomes. Hospital practices to connect birthing persons with their newborns as quickly as possible after cesarean delivery may also improve breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., Moore et al., 2016; Rowe-Murray & Fisher, 2002). The WHO and United Nations Children’s Fund Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative outlines best practices to support breastfeeding globally (WHO and UNICEF, 2018) and the Healthy People Initiative includes recommendations to promote higher breastfeeding in the US (Barraza et al., 2020; CDC, 2021). Support programs which focus on compensating for impacts of lower socioeconomic status, such as targeted educational programs, can help address predictors of breastfeeding outcomes that fall further beyond the control of these birthing persons and their health care providers. Our research supports continued need for such support programs, as the clinical and sociodemographic factors they seek to intervene on are risk factors for poorer breastfeeding outcomes in our study.

Strengths of our study include its large size, prospective design, and extensive breastfeeding outcome data for birthing person-infant pairs living in rural New England, since rural populations are often underrepresented in research settings. This region is well-suited to investigate breastfeeding initiation and duration because breastfeeding rates are relatively high compared to average rates in the US (CDC, 2022). The consistency we observed between important predictors of breastfeeding initiation and duration in our rural cohort compared with previous studies in the general US population (Stough et al., 2019) and a rural Australian cohort (Cox et al., 2015) suggest that factors influencing breastfeeding outcomes are not specific to rural regions, though we did not explicitly test this hypothesis in our study. Our cohort included individuals with private water systems so it tended to over-represent those living in individual homes or small communities and approximately 30% of birthing persons in our study had not earned a college degree. Our findings are potentially limited in their generalizability since our cohort is predominantly comprised of birthing persons identifying as non-Hispanic White, though this is true for the majority of rural America. Further research is needed to expand knowledge of breastfeeding outcomes among birthing persons living in poor, non-White, rural areas of the US. When characterizing exclusive breastfeeding, we used the WHO definition in which supplementation of non-breastmilk foods or liquids, including water, was classified as the end exclusive breastfeeding (WHO, 2019). While this is a strength of our study because it most closely reflects health-based guidelines, our findings may not be directly comparable to other studies which apply a more lenient definition of exclusive breastfeeding. Misclassification of breastfeeding outcomes may have occurred if a birthing person in our study exclusively fed their infant manually-expressed breastmilk and did not consider this to be a form of breastfeeding when providing information about infant feeding via the first postpartum study questionnaire. Because breastfeeding initiation is high (96%) in our cohort and follow-up postpartum questionnaires specifically ask about breastfeeding defined as either direct feeding or using expressed milk, we believe that such misclassification is rare in our study.

Conclusions

In a rural pregnancy cohort from northern New England, like in many regions of the US, we found breastfeeding initiation was high, but the percentages of birthing persons meeting health-based guidelines for exclusive and any breastfeeding duration were low. Metrics of higher socioeconomic status and good birthing person health were positively associated with breastfeeding initiation and duration, whereas measures of poor health and cesarean delivery negatively predicted breastfeeding outcomes. Collectively, this and prior research inform interventions such as support programs targeted at individuals at risk of poorer breastfeeding outcomes, to improve breastfeeding and, thus, birthing person and child health across the life course.

Data Availability

Investigators interested in additional information about this study are referred to the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study website. For other questions, investigators should contact Margaret Karagas, PhD (margaret.r.karagas@dartmouth.edu).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

AAP, (2020). Breastfeeding. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Breastfeeding/Pages/default.aspx

Åkerström, S., Asplund, I., & Norman, M. (2007). Successful breastfeeding after discharge of preterm and sick newborn infants. Acta Paediatrica, 96(10), 1450–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00502.x

Amiel Castro, R. T., Glover, V., Ehlert, U., & O’Connor, T. G. (2017). Antenatal psychological and socioeconomic predictors of breastfeeding in a large community sample. Early Human Development, 110, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.04.010

Barraza, L., Lebedevitch, C., & Stuebe, A. (2020). The Role of Law and Policy in Assisting Families to Reach Healthy People’s Maternal, Infant, and Child Health Breastfeeding Goals in the United States.

Beauregard, J. L., Hamner, H. C., Chen, J., Avila-Rodriguez, W., Elam-Evans, L. D., & Perrine, C. G. (2019). Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among US infants born in 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(34), 745–748. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a3

Buckley, S. J. (2015). Executive summary of hormonal physiology of childbearing: evidence and implications for women, babies, and maternity care. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 24(3), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.24.3.145

CDC. (2020b). Results: Breastfeeding Rates. Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 2010–2017: National Immunization Survey.

CDC. (2020a). Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity | Overweight & Obesity | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html

CDC. (2021). Healthy People 2030.

CDC. (2022). 2022 Breastfeeding Report Card. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm

Cohen, S. S., Alexander, D. D., Krebs, N. F., Young, B. E., Cabana, M. D., Erdmann, P., Hays, N. P., Bezold, C. P., Levin-Sparenberg, E., Turini, M., & Saavedra, J. M. (2018). Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatrics, 203, 190-196.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.008

Colombo, L., Crippa, B. L., Consonni, D., Bettinelli, M. E., Agosti, V., Mangino, G., Bezze, E. N., Mauri, P. A., Zanotta, L., Roggero, P., Plevani, L., Bertoli, D., Giannì, M. L., & Mosca, F. (2018). Breastfeeding determinants in healthy term newborns. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010048

Cordero, L., Valentine, C. J., Samuels, P., Giannone, P. J., & Nankervis, C. A. (2012). Breastfeeding in women with severe preeclampsia. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7(6), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0019

Cox, K., Binns, C. W., & Giglia, R. (2015). Predictors of breastfeeding duration for rural women in a high-income country: Evidence from a cohort study. Acta Paediatrica, 104(8), e350–e359. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12999

Demirci, J., Schmella, M., Glasser, M., Bodnar, L., & Himes, K. P. (2018). Delayed lactogenesis II and potential utility of antenatal milk expression in women developing late-onset preeclampsia: A case series. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1693-5

Eidelman, A. I., & Schanler, R. J. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3552

Ekstrom, A., Widstrom, A.-M., & Nissen, E. (2003). Breastfeeding support from partners and grandmothers: Perceptions of Swedish women. Birth, 30(4), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00256.x

Galtry, J. (2003). The impact on breastfeeding of labour market policy and practice in Ireland, Sweden, and the USA. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00372-6

Gartner, L. M., Morton, J., Lawrence, R. A., Naylor, A. J., O’Hare, D., Schanler, R. J., Eidelman, A. I., American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. (2005). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 115(2), 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2491

Guelinckx, I., Devlieger, R., Bogaerts, A., Pauwels, S., & Vansant, G. (2012). The effect of pre-pregnancy BMI on intention, initiation and duration of breast-feeding. Public Health Nutrition, 15(5), 840–848. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002667

Hackman, N. M., Schaefer, E. W., Beiler, J. S., Rose, C. M., & Paul, I. M. (2015). Breastfeeding outcome comparison by parity. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(3), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0119

Heck, K. E. (2006). Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Reports, 121, 51–59.

Henninger, M. L., Irving, S. A., Kauffman, T. L., Kurosky, S. K., Rompala, K., Thompson, M. G., Sokolow, L. Z., Avalos, L. A., Ball, S. W., Shifflett, P., Naleway, A. L., Pregnancy and Influenza Project Workgroup. (2017). Predictors of breastfeeding initiation and maintenance in an integrated healthcare setting. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 33(2), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334417695202

Hill, P. D., Aldag, J. C., Demirtas, H., Naeem, V., Parker, N. P., Zinaman, M. J., & Chatterton, R. T. (2009). Association of serum prolactin and oxytocin with milk production in mothers of preterm and term infants. Biological Research for Nursing, 10(4), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800409331394

Hobbs, A. J., Mannion, C. A., McDonald, S. W., Brockway, M., & Tough, S. C. (2016). The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0876-1

Huang, Y., Ouyang, Y. Q., & Redding, S. R. (2019). Maternal prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and cessation of breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breastfeeding Medicine, 14(6), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0138

IOM. (2009). Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines.

Kehler, H. L., Chaput, K. H., & Tough, S. C. (2009). Risk factors for cessation of breastfeeding prior to six months postpartum among a community sample of women in Calgary Alberta. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 100(5), 376–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03405274

Kitano, N., Nomura, K., Kido, M., Murakami, K., Ohkubo, T., Ueno, M., & Sugimoto, M. (2016). Combined effects of maternal age and parity on successful initiation of exclusive breastfeeding. Preventive Medicine Reports, 3, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.12.010

Landmann, E., Reiss, I., Misselwitz, B., & Gortner, L. (2006). Ponderal index for discrimination between symmetric and asymmetric growth restriction: Percentiles for neonates from 30 weeks to 43 weeks of gestation. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 19(3), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050600624786

Lubold, A. M. (2019). Historical-qualitative analysis of breastfeeding trends in three OECD countries. International Breastfeeding Journal, 14(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-019-0230-0

Lutsiv, O., Giglia, L., Pullenayegum, E., Foster, G., Vera, C., Chapman, B., Fusch, C., & McDonald, S. D. (2013). A population-based cohort study of breastfeeding according to gestational age at term delivery. Journal of Pediatrics, 163(5), 1283–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.056

Maastrup, R., Hansen, B. M., Kronborg, H., Bojesen, S. N., Hallum, K., Frandsen, A., Kyhnaeb, A., Svarer, I., & Hallström, I. (2014). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding of preterm infants. Results from a prospective national cohort study. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089077

Meek, J. Y., & Noble, L. (2022). Technical report: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2022057989. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057989

Mennella, J. A., Yourshaw, L. M., & Morgan, L. K. (2008). Bresatfeeding and smoking: Short-term effects on infant feeding and sleep. Chemical Senses, 120(3), 497–502.

Moore, E. R., Bergman, N., Anderson, G. C., & Medley, N. (2016). Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4

NHDES. (2018). Review of the Drinking Water Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standard (AGQS) for Arsenic.

Nissen, E., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Svensson, K., Stock, S., Widström, A. M., & Winberg, J. (1996). Different patterns of oxytocin, prolactin but not cortisol release during breastfeeding in women delivered by Caesarean section or by the vaginal route. Early Human Development, 45(1–2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-3782(96)01725-2

Parker, C. R., MacDonald, P. C., Guzick, D. S., Porter, J. C., Rosenfeld, C. R., & Hauth, J. C. (1989). Prolactin levels in umbilical cord blood of human infants: Relation to gestational age, maternal complications, and neonatal lung function. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 161(3), 795–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(89)90404-3

Prior, E., Santhakumaran, S., Gale, C., Philipps, L. H., Modi, N., & Hyde, M. J. (2012). Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95(5), 1113–1135. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.030254

Rowe-Murray, H. J., & Fisher, J. R. W. (2002). Baby Friendly Hospital practices: Cesarean section is a persistent barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding. Birth, 29(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00172.x

Salone, L. R., Vann, W. F., & Dee, D. L. (2013). Breastfeeding: An overview of oral and general health benefits. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 144(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.14219/JADA.ARCHIVE.2013.0093

Schalla, S. C., Witcomb, G. L., & Haycraft, E. (2017). Body shape and weight loss as motivators for breastfeeding initiation and continuation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070754

Scott, J. A., Binns, C. W., Oddy, W. H., & Graham, K. I. (2006). Predictors of breastfeeding duration: Evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1991

Steurer, L. M. (2017). Maternity leave length and workplace policies’ impact on the sustainment of breastfeeding: global perspectives. Public Health Nursing, 34(3), 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12321

Stough, C. O., Khalsa, A. S., Nabors, L. A., Merianos, A. L., Peugh, J., Odar Stough, C., Khalsa, A. S., Nabors, L. A., Merianos, A. L., & Peugh, J. (2019). Predictors of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months in a national sample of US children. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118774208

UNICEF, (2015). Breastfeeding | Nutrition | UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_24824.html

Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Ekström-Bergström, A., Buckley, S., Massarotti, C., Pajalic, Z., Luegmair, K., Kotlowska, A., Lengler, L., Olza, I., Grylka-Baeschlin, S., Hadjigeorgiu, E., Villarmea, S., & Dencker, A. (2020). Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during breastfeeding—A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0235806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235806

Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J. D., França, G. V. A., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., Murch, S., Sankar, M. J., Walker, N., & Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

Wallenborn, J. T., & Masho, S. W. (2016). The interrelationship between repeat cesarean section, smoking status, and breastfeeding duration. Breastfeeding Medicine, 11(9), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0165

Wallwiener, S., Müller, M., Doster, A., Plewniok, K., Wallwiener, C. W., Fluhr, H., Feller, S., Brucker, S. Y., Wallwiener, M., & Reck, C. (2016). Predictors of impaired breastfeeding initiation and maintenance in a diverse sample: What is important? Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 294(3), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3994-5

WHO and UNICEF (Ed.). (2018). Implementation Guidance 2018: Protecting, promoting and supporting Breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: The revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative.

WHO. (2019). Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants. E-Library of Evidence for Nutrition Actions (ELENA).

WHO. (2020). Breastfeeding. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1

Zou, G. (2004). Modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(7), 702–706.

Funding

Support for this work was provided by NIGMS P20 GM104416, NIEHS P01-ES022832 and P42 ES007373, and EPA RD-83544201.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors provided critical review and feedback of the manuscript. KAC conducted all analyses and drafted the manuscript. LGG assisted with data management and provided technical expertise to inform the statistical analyses. ERB provided technical review on pregnancy and breastfeeding concepts. MRK developed and oversees the NHBCS, contributed to study design and provided technical review of the analysis and manuscript. MER was responsible for study design, provided technical review of all analyses, and contributed to manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

Approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Dartmouth College. Participants provided written, informed consent via IRB-approved consent protocols.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Crawford, K.A., Gallagher, L.G., Baker, E.R. et al. Predictors of Breastfeeding Duration in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study. Matern Child Health J 27, 1434–1443 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03714-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03714-4