Abstract

Objectives

The preterm birth rate for Black women in the U.S. is consistently higher than other racial groups. The crisis of preterm birth and adverse birth outcomes among Black people is a historical, systematic confluence of racism, stressors, and an unsupportive and hostile healthcare system. To inform the development of preterm birth risk reduction interventions, this study aimed to collect and synthesize the experiences of Black women who gave birth preterm along with clinicians and community-based organizations who serve them.

Methods

A qualitative study design was employed whereby nine focus groups and 17 key informant interviews that included Black women, clinicians, and representatives from community-based organizations were facilitated in Los Angeles County from March 2019 to March 2020. Participants were recruited through the organizations and the focus groups took place virtually and in person. The process of thematic analysis was employed to analyze the focus group and interview transcripts.

Results

Five overarching themes emerged from the data. Black women experience chronic and pregnancy-related stress, and have lasting trauma from adverse maternal health experiences. These issues are exacerbated by racism and cultural incongruence within healthcare and social services systems. Black women have relied on self-education and self-advocacy to endure the barriers related to racism, mistreatment, and their experiences with preterm birth.

Conclusions for Practice

Healthcare and social service providers must offer more holistic care that prioritizes, rather than ignores, the racial components of health, placing increased importance on implementing inclusive and culturally-appropriate patient education, attentiveness to patient needs, respectful care, and support for Black women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

There is vast research establishing that Black women disproportionately experience adverse maternal health outcomes, with far fewer studies on the patient experiences of Black women and factors contributing to adverse outcomes.

This study is a community-designed project that assesses the perspectives of various stakeholders involved in perinatal healthcare for Black women and is inclusive of the voices of Black women. The results of this study support the collaborative development of a community-focused model to reduce the Black preterm birth rate in Los Angeles County, with broader implications in addressing the factors that contribute to racial health disparities in the United States.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is a leading contributor to infant mortality and morbidity in the U.S. (Ely & Driscoll, 2020). Furthermore, racial disparities persist in PTB rates with Black women disproportionately impacted by adverse birth outcomes (Giurgescu et al., 2011). While the PTB rate in the U.S. declined in 2020 for the first time in several years, the rate for Black women did not change significantly (Hamilton et al., 2021).The same 2020 data found Black women experience a PTB rate that is 50% higher than women of other races.

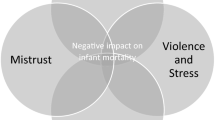

Racial disparities in PTB are complex and multifactorial (Manuck, 2017). Researchers have identified racism (Braveman, et al., 2021), disrespectful health care (McLemore et al., 2018), and chronic toxic stress (Burris et al., 2019; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2011) rather than genetic differences, as more plausible explanations for the racial disparities in preterm births. To mitigate PTB and other adverse perinatal outcomes, we must address personal and systemic barriers Black women face during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period (Davis, 2019; Giscombe & Lobel, 2005; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2008; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020).

In 2016, the March of Dimes Prematurity Collaborative released a consensus statement calling for multi-disciplinary approaches that address social drivers of health and promote birth equity to reduce racial disparities in birth outcomes (Jackson et al., 2020). Success in developing and implementing PTB prevention programs for Black women requires a deep understanding of the perinatal experiences faced by Black women and their interactions with community-based organizations (CBOs), and clinical providers.

The purpose of this study was to collect and synthesize the experiences of Black women who have experienced PTB, along with insights from clinicians and CBOs who serve Black women, to inform the development of evidence-based, culturally appropriated PTB prevention programs, policies, and system changes as part of the Community Birth Plan Task Force. The Community Birth Plan is a multi-sector collaborative led by the California Department of Public Health that seeks to galvanize select birthing hospitals and community partners in Los Angeles County around evidence-based health improvement activities to improve Black birth outcomes and decrease racial disparities in preterm birth.

Methods

Design

A qualitative study design was employed whereby nine focus groups and 17 key informant interviews were facilitated, in-person and virtually, between March 2019 and March 2020 in Los Angeles County. Los Angeles County is the pilot site of the Community Birth Plan because it is the most populous county in California and has the largest number of Black births along persistent racial disparities in birth outcomes (California Department of Public Health, 2021). This approach was selected as most appropriate to achieve the purpose of the study, since qualitative approaches provide a critical avenue for contextualizing complex health inequities and identifying potential pathways toward health equity (Griffith et al., 2017). This study design promoted a deeper understanding of the unique lived experience of each participant within the three groups of interest—Black women with prior PTB experience, perinatal health clinicians, and CBOs serving Black families. The development of focus group and interview guides were done collaboratively among the authors of this paper, who represent diverse expertise in perinatal research, public health, maternal and child health social services, advocacy, and community-engaged research. Additionally, the focus group and key informant interview protocols were shared with members of the Community Birth Plan Task Force for feedback.

Focus groups were facilitated by a Black female qualitative researcher. The key informant interviews were facilitated after the focus groups to provide in-depth information from individuals with direct experience with the subject matter. The study [00001522] was approved by the Research Integrity and Oversight Office, Institutional Review Board at the University of Houston.

Eligibility and Recruitment

Four (4) focus groups included women who met the following criteria: (1) self-identify as Black, (2) at least 18 years of age, (3) living in LA County, and (4) have given birth preterm (≤ 37 weeks’ gestation) within the last 3 years. Two focus groups were facilitated in-person, and childcare and dinner was provided for the duration of the session. Two focus groups were facilitated online through the videoconferencing platform Zoom to accommodate interested participants who could not attend an in-person session. Recruitment for the focus groups was supported through the distribution of focus group flyers to individuals and CBOs who provide various services to Black women and their networks. Participating women received $35 cash.

Three (3) focus groups included CBO representatives who provide services to Black women in a variety of settings. Services ranged from public health, home visiting, and clinical support to health education and empowerment. Participants all had experience working with Black pregnant and parenting women. Two focus groups were facilitated in-person and the third was conducted online through the videoconferencing platform Zoom. Recruitment for the focus groups was supported through the distribution of flyers and e-mail invitations to leaders of community-based organizations to share with employees. Representatives received a $20 gift card for their participation.

Two (2) focus groups included clinical providers from hospitals, community clinics and birth centers who had experience caring for Black pregnant women. This group was facilitated virtually using the videoconferencing platform Zoom. Recruitment for the focus group was supported through the distribution of flyers and e-mail invitations to clinicians within the March of Dimes California network. Clinicians received a $10 gift card for their participation. Incentive amounts were set based on recommendations of the Community Birth Plan Task Force and others connected to the project.

In addition to the nine focus groups, 17 key informant interviews took place that included Black women, members of CBOs that serve Black women, and clinicians who serve Black women, including obstetricians, lactation consultants, and doulas. The interviews focused on key informants’ perspectives on the challenges Black women experience and their own experiences working with Black women. Key informants were recruited from the study team network and subsequently a technique of snowball sampling was employed to include additional key informants. Focus group participants provided written consent to participate in this study while virtual focus group participants and key informants were given the informed consent via e-mail and provided verbal consent during the recorded session. Characteristics of focus group and key informant interview participants are provided in Table 1.

Procedures and Analysis

Prior to the focus group beginning, participants were presented information about the study. Those who provided informed consent engaged in a 90-minute discussion on their experiences related to preterm birth. The women focus groups delved into three discussion topics: (1) pregnancy and birthing experience, (2) management of health complications before, during, and after pregnancy, and (3) perspectives on the care received. The CBO focus groups covered the following discussion topics: (1) issues facing Black women, (2) observed clinical challenges, and (3) strategies for improvement. The clinician focus groups explored three discussion topics: (1) provider-level factors related to their own experience caring for Black women, (2) institutional barriers and challenges, and (3) health system factors that impact care for Black women experiencing high-risk pregnancies. The key informants were asked to provide their perspective on the statements made by participants from the focus groups.

All focus group sessions and key informant interviews were recorded and transcribed. Following a thematic analysis approach, transcripts were read by an analysis team of four coders trained in qualitative data analysis; the focus group facilitator was a member of the analysis team (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). The analysis team independently reviewed the transcripts line-by-line and identified emerging themes for each question. After independent coding concluded, the analysis team compared coding schemes to identify agreements and resolve disagreements. A second review was completed where the analysis refined themes, along with anecdotes and quotes that would serve as illustrative examples of the themes.

Results

Table 1 describes participant demographics. Among participants in the women focus groups, 82% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, 62% were multiparous when they experienced preterm birth, and 77% had private insurance. These sociodemographic data were obtained prior to the commencement of the focus groups when the women enrolled in the study.

Five overarching themes emerged from findings across the focus groups and interviews. These themes revealed the challenges associated with preventing PTB among Black women: chronic and pregnancy-related stress among Black women; lasting trauma from adverse maternal experiences; racism in healthcare; cultural incongruence in patient care; and self-education and self-advocacy.

Chronic and Pregnancy-Related Stress Among Black Women

Most participating women reported experiencing significant stress and anxiety prior to and during pregnancy. Stressors were related to relationships, finances, work, health, commuting, family, and general society (e.g., politics, discrimination, feeling unsafe). Many women reported stressors related to their pregnancy, including symptoms (e.g., high blood pressure, diagnoses (e.g., fetal growth restriction), and management (e.g., activity restriction). Most women reported facing compounding stresses related to childcare for their other children.

CBO representatives discussed the cumulative effects of racism that manifest as chronic stress and exacerbate health risks for Black women. In the present, racism shows up in how Black women are treated in a variety of settings. A representative stated:

Racism manifests itself in everyday activities. It is felt by Black women daily, whether at work, in a clinical setting, or on the news and in their community through the perpetual violence against people of color.

CBO representatives differentiated between microstressors and macrostressors; whereas microstressors are continuous low levels of stress and anxiety that persist on a daily basis, macrostressors are the larger events that happen in one’s life. The concept of weathering was presented several times, meaning the health of Black women may begin to deteriorate as a result of biological changes occurring from daily cumulative stress (Geronimus et al., 2006). As one representative put it:

There are a number of stressors that affect the Black mother today. We have microstressors and macrostressors. The microstressors are far more dangerous than macrostressors. The continuous stress that many Black mothers feel never truly calms, thus creating a hypervigilant body that maintains anxiety.

Participants reported many Black pregnant women accept high stress as the status quo and manage to the best of their ability. While acknowledging they had support systems, many women expressed that their networks were not helpful in the way they needed. One woman explained:

That stress played a big part in my pregnancy and I just had to deal. I had to function through this pregnancy even though I was going through so much and, at times, suffering.

In some instances, women sought to cope with stress through activities such as dance classes, prayer, crying, and yoga. In general, they proceeded with daily life and coped with the stress privately. The women rarely described routine methods of specifically managing stress; instead, they mentioned performing these activities when their stress level was exceptionally high.

Undergirding much of the conversation around stress was the notion that each woman recognized the stress was happening but could not eradicate it, nor did they report their stress to their prenatal provider. The women mentioned prioritization when confronting their stress. Several described how they were, “trying to do the best [they] can,” and only dealt with the most pressing issues in their lives. Desensitized to their chronic stress, most women were more likely to address their pregnancy-related stressors.

Clinicians reported that they understood Black women are dealing with stressors during their pregnancy and experience it through their patient interactions. All participants—women, CBO representatives, and clinicians—agreed Black women need more social support throughout pregnancy and after giving birth. Clinicians remarked on the significance of women having social support for a successful pregnancy. One physician stated:

Moms need an entire system throughout their pregnancy and after they have their baby. They need doulas, social services like transportation, food access support, family support, and mental healthcare; however, Black moms don’t get a fraction of these supports.

Among the 26 women, two had a doula and none had heard of group prenatal care. However, all women participants acknowledged wanting a safe space to talk about their experiences. Several remarked even participating in a focus group with women who have had similar pregnancies was cathartic. While most women acknowledged there are formal supports (such as counselors) available to them, they felt distrustful and feared being judged for experiencing transition stress or postpartum depression. One woman explained:

I know I had, maybe still have, postpartum depression but I wouldn’t dare tell my doctor because I don’t know what she would do with that information or how she would judge me for not being a good mom.

Lasting Trauma from Adverse Maternal Experiences

Many of the participants reported feeling varying levels of traumatization after giving birth. Persistent emotional challenges for the women included processing a fast series of traumatic events, especially for those who gave birth without knowing they were high risk. Many women recalled there were few opportunities to process their adverse birth outcomes. One woman conveyed she was operating in “survival mode”, struggling to stay afloat day-by-day and “keep it together” for her baby and family.

Transitioning out of this phase was an adjustment for most women, with many on constant alert for the possibility of another complication with their baby. According to the women, this instinctive vigilance was due to their experience of being hospitalized and giving birth without enough time to emotionally accept their circumstances. Even relatively small tasks, such as naming the baby sooner than the parents expected or explaining to family what was happening, felt overwhelming.

After giving birth, the women had varying experiences with the NICU clinicians that ranged from supportive to pushy and disrespectful. Several women felt as though they were not provided enough information about the condition and care of their child and were forced to make hasty decisions that would impact their children for the rest of their lives. One woman recalled, “the NICU was distressing.” She remembers feeling her male doctor shaming her for requesting to discuss another treatment option when her baby was regressing after 65 days in the NICU. This was an indication to the woman that the current regimen was not working, and an alternative should be considered. The doctor on duty accused her of not wanting her baby to get better. At that moment, the woman recalls being at the bottom of her faith, losing hope her daughter would survive. The following day, a female doctor came on duty and immediately suggested an alternative pathway for her daughter. Within days, her infant’s health improved, and she began to thrive.

In several instances, the women carried stress and memories from previous traumatic pregnancies to subsequent pregnancies. One woman shared: her first child was stillborn, and her second pregnancy ended traumatically. While in the hospital on bedrest, she repeatedly told the nurses that she felt like she was going into labor and for hours, no one believed her. She gained the attention of the nursing staff after she had progressed so significantly, as she recalled, “[the baby was] coming out of my vagina.” After the birth of her second child, she was in extreme pain and experienced disassociation when she awakened. Although told she had just given birth, the preceding trauma made it difficult for her to reconcile what had happened to her. It took her almost a day to visit her baby. Once she was released, she experienced more stress because she had to go home without her child. Without a car or funds to get to and from the hospital across town, she felt guilty.

After leaving the hospital with their babies, the women recalled the stress of adjusting to life with a newborn at home. As one woman put it, “I had pent-up stress that really didn’t affect me until my baby was better.” Words used to describe these feelings included: “nerve-wrecking,” “tired,” “hella hard,” “sleepless,” and “stressful.” Going back to “business as usual” for the women was difficult. After giving birth earlier than anticipated, the women had no choice but to adjust their timelines to accommodate other personal and professional responsibilities. One woman recalls having such a traumatic birth experience that she developed post-traumatic stress disorder. She gave birth to her daughter at 25 weeks. She said, “I thought it was my fault that my body couldn’t carry my baby.” She admits to feeling out of control and even cutting herself.

Most of the women admit that the trauma from their pregnancy and birthing experience lingers, and even impacts their plans for childbearing. One woman shared, her first pregnancy experience of giving birth at 31 weeks scared her so much that she likely will not have another child. The experience that frightened her most was being so close to death while her clinical care team, friends, and family constantly ignored her symptoms and pleas for help. She recalls, “I felt ignored and invisible. I thought I was going to die and would die alone. I was sure of it.”

Racism and Broken Healthcare Systems

Most focus group participants from all the three groups—women, CBO representatives, and clinicians—conveyed there is lack of trust between Black women and the healthcare system. Most women reported having experienced or knowing of instances when the healthcare system clearly discriminated against them or a loved one.

CBO representatives pointed to the historical, enduring legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and the inability to trust the healthcare system as part of ‘the load’ Black women bear in life and through pregnancy. One CBO representative stated:

There is so much anecdotal and empirical evidence that support Black women’s claims that, no matter how smart, nice, rich we are, we are just not listened to.

The impact of this racism was exhibited in the women’s perspective that clinicians see Black women as incompetent. Both the women and CBO representatives reported Black women are not listened to in clinical settings. The women identified several occasions during their birthing experiences when they were ignored or were not communicated with respectfully. Despite the rationalization by the women and CBO representatives as to why clinicians fail to listen to patients, the recurring question among participants from all groups, including clinicians, was how clinicians can be held accountable for antagonistic and discriminatory medical practices. One woman inquired:

Who should I have spoken to when I was so sick, swollen, and delirious that I could barely walk, that my doctor won’t take me seriously?

Similarly, CBO representatives identified a lack of clinician accountability. One representative shared she witnessed a physician treating her client inappropriately and brought it up to the physician. When she took the additional step to document the incident in a formal complaint, she was given complex instructions on how to file the complaint and had difficulty following up on the complaint after she was able to file it. From her perspective, the experience of simply filing a complaint and failing to receive a response was a clear indicator of the practically nonexistent provider accountability.

Participants in the clinician groups identified they don’t have enough time to spend with patients and, therefore, are unable to build rapport. The clinicians further noted that the healthcare system is broken in a way that makes it difficult for Black women to trust them. As one nurse remarked:

Patients don’t trust us. The healthcare industry has their own cross to bear. Patients believe that they will have another poor experience, which makes it difficult for them to accept advice and interventions.

Additionally, there is not an emphasis on prevention. The lack of prevention within healthcare was mentioned frequently by all participants and lamented as a missed opportunity. These missed opportunities allow for racial inequities in birth outcomes to persist. One clinician noted that they believe prevention is the key to reducing PTB and high-risk pregnancies, with the most salient form of prevention consisting of education and social support.

Clinicians further mentioned continuing education is also needed for medical professions. New treatments, preventions, and interventions are not always known by clinicians. In addition to requiring up-to-date information about prevention and treatments, clinicians mentioned needing better training on how to build trust with the patients and facilitate adherence to medical care recommendations. As one physician commented:

We sometimes don’t listen because after we make a plan, mothers don’t adhere. We are not trained well to manage and cope with that.

Another physician remarked:

It is not unique to African American women that they are not heard. This is a widespread complaint in the healthcare profession and points to the need to learn to work better with individuals. Back when I was in medical school, we didn’t spend a lot of time on listening. Coupled with the financial need to see a lot of patients in a day makes this a really challenging issue to manage.

Despite claims of widespread noncompliance made by clinicians, CBO representatives recognized their clients have experienced poor communication in clinical settings, leaving lingering questions about patient attitudes toward doctors and the necessity for care coordination. Several CBO representatives acknowledged phenomenal work being done by many health professionals who make a difference. However, they also noted that those who do not respect Black women can damage their trust in the healthcare system. One CBO representative noted:

I regularly talk Black mothers into visiting the doctor and personally vouch that the doctor will take care of them.

Cultural Incongruence

Culture provides the context for health and social services, establishing the foundation for expectations, actions, interactions, and meanings of care between individuals, their clinicians, and their community. Cultural congruence is a process of effective interaction between care providers and their clients, which is maximized when the two parties share aspects of their culture and thus a deeper understanding of one another’s values, behaviors, and perspectives (Schim & Doorenbos, 2010). Alternatively, cultural differences between care providers and clients—known as cultural incongruence—may lead to wrong assumptions, disparate priorities, a lack of shared goals, and conflict (Derrington et al., 2018). Past research has shown differences in cultural practices and preferences between maternity care services and the communities they serve can affect the decisions of women on their engagement with care providers (Jones et al., 2017).

Although the issue of PTB is significant for Black women, they rarely lead health and social service organizations. According to CBO representatives, Black women mostly hold entry- to middle-level roles within organizations but are rarely in leadership positions. Moreover, groups that hire Black women can, consciously or unconsciously, create conditions where Black women lack power and are paid inadequately. One CBO representative noted:

One of the ways white women can ‘show up’ is to be the best ally they can be and actively work to increase diversity in the organizational staff and board.

CBO representatives from all backgrounds identified culturally incongruent CBO leadership as a problem contributing to PTB among Black women. Black women who work in this space often assist Black community members at the ground level by providing care and support, but rarely have a ‘seat at the table’ to inform or make policy and organizational decisions. Black women are excluded from positions of power that would allow them to create new policies that improve the access and ability to wield resources in ways that are needed. One CBO representative shared:

Power and money are issues that we have not come to grips with. We have been around this circle because people don’t want to share power and resources.

Along with the inclusion of Black women in CBO leadership, organizations value the involvement of doulas and health navigators as part of their support for Black pregnant women, their family’s transition in preparing for a new baby, and healthier child delivery. One CBO representative discussed the added value of Black doulas, stating:

Every Black mom should have Black doula supporting her and walking with her during this life changing experience.

All participants agreed that culturally congruent care—in both social service and clinical settings—yields better outcomes.

Self-education and Self-advocacy

Black women reported that self-education and self-advocacy were critical for their children’s health and their own health. Despite most of the women having a college level education, they recalled being “talked at” or “talked down to” when it came to their healthcare and the healthcare of their baby. They often felt as though doctors were providing limited information to pressure the women into the most convenient course of action. One woman remarked:

You have to advocate and educate yourself for your baby because they will try to bully you.

Lapses in clinician-patient communication were made clear when most of the women shared that they did not know they were experiencing a high-risk pregnancy until they were admitted to the hospital. As a possible result, few women knew of clinical interventions such as low-dose aspirin or progesterone. In most cases, the women had a serious pregnancy complication that spurred the preterm birth, such as preeclampsia, prior to hospital admission. Only one woman recalled the provision of an intervention during pregnancy, which was administration of progesterone injections. Several women shared feelings of guilt associated with not being able to carry their child full term, particularly when their cervixes are called “incompetent” or “weak”. This illuminates the need for clinicians to improve the sensitivity of their communication with patients.

In several instances, the women reported taking ownership over their health by educating and advocating for themselves. They recalled conducting online research, reading message boards, and speaking to family members in the health field. One woman, who had given birth at 31 weeks, shared she and her mother had to fight for her to be taken seriously. Her prenatal physician repeatedly dismissed her symptoms of swelling in her hands and feet. She looked up her symptoms on her own and self-diagnosed with preeclampsia. Her mother forced her to go to the emergency department, where it was determined that she also had pericardial effusion or fluid around the heart. The doctor informed her that she was at risk for seizures and death. After she had an emergency C-section, she learned preeclampsia can oftentimes be managed and was grateful that she addressed the issue by going to the emergency department.

A mom of twins felt doctors were providing her with limited options. She recalls it was as if they were saying, “Do this or your baby won’t get better.” She began to learn terminology and actively participated in conversations about her baby’s care.

A common thread across both the women and CBO participants was that, because Black women face bias, racism, and disrespect in the clinical environment, medical professionals need to be held accountable for providing quality, respectful, and responsive health care. Several CBO representatives acknowledged phenomenal advocacy work being done by many health professionals. However, they also noted the importance of regular mortality reviews to hold institutions and clinicians accountable for systematic discriminatory practices.

All clinicians identified themselves as actively working to improve Black maternal health through speeches, research, and hosting group prenatal care, but also noted that they want to do more. There are significant challenges in place that prevent clinicians from doing so. Chief among them is a lack of institutional support, scarcity of time, and absence of funds. One clinician remarked about their employer:

To be candid, people are not concerned. Now that there has been notable incidences—and in some cases deaths—related to the Black maternal health crisis, there is some movement on the issue but definitely not enough to make a difference

Many health professionals felt a sense of complacency or confusion in identifying a course of action. A physician who speaks regularly across the country on the topic of racism cited meeting countless health professionals who discuss their concern with Black maternal health and their associated guilt of not doing more:

I go to a lot of places discussing this issue and after my talks, I get a lot of people who come up to me to discuss this issue and always express guilt about not doing enough in their work setting. I get the sense that they are looking for the one answer of what to do and the answer is: there isn’t one answer. This problem requires a big, coordinated approach and honesty and attention from decision-makers to make this a priority.

Discussion

This study assessed the perspectives of Black women, clinicians, and CBOs on the management and prevention of preterm birth in Black women. The major themes identified in this study provide a multidisciplinary explanation for disproportionate Black PTB rates and barriers to maternal care. Furthermore, these themes are informative for efforts to improve birth outcomes among Black women, including the Community Birth Plan in Los Angeles County and similar multi-sector collaboratives elsewhere in the U.S. Additional research must assess whether this study’s findings are consistent among a more expansive, representative group of Black women, clinicians, and organizations across the country.

Black women, clinicians, and CBO representatives all agreed Black women experience high levels of stress and are regularly discriminated against in clinical settings throughout their pregnancy. Major sources of stress causing the disparities in Black maternal and infant health are attributable, in part, to racism and discrimination (Dominguez et al., 2008; Rosenberg et al., 2002). Researchers have found racial and community stress levels contribute to inflammation and the release of hormones that trigger adverse pregnancy outcomes (Miller et al., 2009). Yet by the time Black women reach high-risk status or are admitted for delivery sooner than expected, it is often too late to address past stressors since there are new stressors related to the current situation. Even if new stressors have not developed, the cumulative stress experienced by Black women over their life course cannot be fully addressed in the acute clinical setting.

The impact of Black women not being listened to can compound an already traumatic experience during pregnancy and birth that has lasting effects on women and families (Declercq et al., 2014; Slaughter-Acey et al., 2013). The women and their families must navigate the stress of life after an unanticipated, life-threatening ordeal. Local health officials must consider collaborative efforts between health institutions and CBOs to address stress that Black women face during pregnancy, following delivery, and throughout the life course.

Most participants from all groups conveyed a lack of trust and poor communication between the healthcare system and Black women. Factors that built distrust include racism, disrespect, and previous poor experiences with the healthcare system. Widespread importance was placed on educating women about their own health condition along with that of their child. In most instances, the women participants felt they were not given enough information, did not understand the provided information, or were only given information on a course of action that was convenient for the doctor. Clinicians rely on heuristics from their training and past clinical experiences to address patient needs, but implicit biases and limited time keep clinicians from closely addressing the needs of Black women. These factors, however, do not excuse the dismissal of Black women’s needs in the clinical setting. The clinicians offered some ideas around addressing the poor birth outcomes Black women experience, which include continuing education as part of certification and improving hospital system standards and accountability. CBOs are working to fill this gap in culturally sensitive maternal care; however, existing CBO leadership does not typically include Black women’s voices in its organizational decision-making and thus fails to maximize its impact among Black women.

Most women spoke about suffering emotionally after their pregnancy and birthing experience; they struggled to assume their new or expanded role as a mother and, in some cases, to parent a baby who needed much more attention than usual. All the women spoke about the various ways stress “hit” them following delivery. For some, it was not until their baby was home and getting better. For others, it was months after they gave birth and returned to work. The experiences varied widely, but most acknowledged that there were few opportunities to share their stress with others or feel comfortable seeking help. Environmental factors may play a role in the severity of psychological distress Black women experience following preterm birth. In one study, Black mothers of preterm infants showed higher levels of stress related to the sights and sounds of the hospital environment, while high levels of stress related to their infant’s appearance and their altered parental role were comparable to mothers of other racial backgrounds (Miles et al., 2002).

Overall, there is a lack of safety felt by Black women in the healthcare system. Black women’s stress is exacerbated by having to navigate a system that is unfamiliar, frightening, and at times hostile to them. Clinicians and CBOs play significant roles in mitigating or increasing the stress of women through the behaviors they adopt. The Black maternal health crisis is likely to remain stagnant without accountability for clinicians, cultural congruency in CBOs, and increased social support for women.

Limitations of this study included gaining perspectives largely from Black women. The clinicians and CBO participants mostly consisted of Black women. Although this study is focused on Black women, there are individuals of varying identities who serve this population, and their perspectives were needed. Notably, advertisements for the CBO focus groups were open to all individuals working in this space. During the first CBO focus group, only Black women representatives were referred by their employers to participate. This is not a criticism of the organizations they represent but is possibly symptomatic of the recurring challenge of Black women contributing more or being expected to contribute differently.

There was also difficulty recruiting clinicians for sessions. As a result, insights from clinicians were limited. Finally, this study describes the experience of Black birthing women, CBOs, and clinicians in Los Angeles County, which likely differs in other parts of the country. However, our findings substantiate similar findings from studies with Black birthing women in other regions (Altman et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2001; Mehra et al., 2020).

Conclusions for Practice

The disparity in Black maternal healthcare must be addressed to improve Black maternal and infant health outcomes. Overwhelmingly, Black women expressed deep-seated disempowerment, distrust in the medical system, and high stress environments as consistent factors contributing to racially inequitable maternal health outcomes. Identifying these gaps based on the patient experience allows healthcare and social service providers to offer more holistic care that prioritizes, rather than ignores, racial components of health. Additionally, this study calls attention to systemic faults when treating Black women, regardless of social factors such as socioeconomic status. Going forward, it is crucial that policymakers, clinicians, community partners, and patients confront the causes of these racial health disparities and work collaboratively to reduce the rate of Black preterm births.

Data Availability

The data are fully accessible by the lead author.

Code availability

The codes are fully accessible by the lead author.

References

Altman, M. R., Oseguera, T., McLemore, M. R., Kantrowitz-Gordon, I., Franck, L. S., & Lyndon, A. (2019). Information and power: Women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112491.

Braveman, P., Dominguez, T. P., Burke, W., Dolan, S. M., Stevenson, D. K., Jackson, F. M., & Waddell, L. (2021). Explaining the Black-White disparity in preterm birth: A consensus statement from a multi-disciplinary scientific work Group convened by the march of Dimes. Frontiers in Reproductive Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.684207

Burris, H. H., Lorch, S. A., Kirpalani, H., Pursley, D. M., Elovitz, M. A., & Clougherty, J. E. (2019). Racial disparities in preterm birth in USA: A biosensor of physical and social environmental exposures. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 104(10), 931–935. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-316486

California Department of Public Health. (2021). Live Birth Profiles by County. California Health and Human Services Agency. Retrieved from https://data.chhs.ca.gov/dataset/live-birth-profiles-by-county

Chambers, B. D., Arega, H. A., Arabia, S. E., Taylor, B., Barron, R. G., Gates, B., Scruggs-Leach, L., Scott, K. A., & McLemore, M. R. (2021). Black women’s perspectives on structural racism across the reproductive lifespan: A conceptual framework for measurement development. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(3), 402–413.

Davis, D. A. (2019). Obstetric racism: The racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing. Medical Anthropology, 38(7), 560–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2018.1549389

Declercq, E. R., Sakala, C., Corry, M. P., Applebaum, S., & Herrlich, A. (2014). Major survey findings of listening to Mothers SM III: Pregnancy and birth. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 23(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.23.1.9

Derrington, S. F., Paquette, E., & Johnson, K. A. (2018). Cross-cultural interactions and shared decision-making. Pediatrics, 142(Supplement 3), S187. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0516j

Dominguez, T. P., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Glynn, L. M., Hobel, C., & Sandman, C. A. (2008). Racial differences in birth outcomes: The role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychology, 27(2), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194

Ely, D. M., & Driscoll, A. K. (2020). Infant mortality in the United States, 2018: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 69(7), 1–18.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749

Giscombe, C. L., & Lobel, M. (2005). Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychological Bulletin, 131(5), 662–683.

Giurgescu, C., McFarlin, B. L., Lomax, J., Craddock, C., & Albrecht, A. (2011). Racial discrimination and the Black-White gap in adverse birth outcomes: A review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 56, 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00034.x

Griffith, D. M., Shelton, R. C., & Kegler, M. (2017). Advancing the science of qualitative research to promote health equity. Health Education & Behavior, 44(5), 673–676.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Osterman, M. J. K. (2021). Births: Provisional data for 2020 (Vital Statistics Rapid Release No 12). National Center for Health Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198117728549

Jackson, F. M., Phillips, M. T., Hogue, C. J. R., & Curry-Owens, T. Y. (2001). Examining the burdens of gendered racism: Implications for pregnancy outcomes among college-educated African American women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 5(2), 95–107.

Jackson, F. M., Rashied-Henry, K., Braveman, P., Dominguez, T. P., Ramos, D., Maseru, N., & James, A. (2020). A prematurity collaborative birth equity consensus statement for mothers and babies. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(10), 1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02960-0

Jones, E., Lattof, S. R., & Coast, E. (2017). Interventions to provide culturally-appropriate maternity care services: Factors affecting implementation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1449-7

Manuck, T. A. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. In Seminars in perinatology, 41(8), 511–518.

McLemore, M. R., Altman, M. R., Cooper, N., Williams, S., Rand, L., & Franck, L. (2018). Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(201), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.013

Mehra, R., Boyd, L. M., Magriples, U., Kershaw, T. S., Ickovics, J. R., & Keene, D. E. (2020). Black pregnant women “Get the Most Judgment”: A qualitative study of the experiences of Black women at the intersection of race, gender, and pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues, 30(6), 484–492.

Miles, M. S., Burchinal, P., Holditch-Davis, D., Brunssen, S., & Wilson, S. M. (2002). Perceptions of stress, worry, and support in Black and White mothers of hospitalized, medically fragile infants. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 17(2), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpdn.2002.124125

Miller, G. E., Chen, E., Fok, A. K., Walker, H., Lim, A., Nicholls, E. F., Cole, S., & Kobor, M. S. (2009). Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(34), 14716–14721.

Nuru-Jeter, A., Dominguez, T. P., Hammond, W. P., Leu, J., Skaff, M., Egerter, S., & Braveman, P. (2008). “It’s the skin you’re in”: African-American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800301

Rosenberg, L., Palmer, J. R., Wise, L. A., Horton, N. J., & Corwin, M. J. (2002). Perceptions of racial discrimination and the risk of preterm birth. Epidemiology, 13(6), 646–652.

Rosenthal, L., & Lobel, M. (2011). Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: Unique sources of stress for Black American women. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.013

Rosenthal, L., & Lobel, M. (2020). Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina women. Ethnicity & Health, 25(3), 367–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896

Schim, S. M., & Doorenbos, A. Z. (2010). A three-dimensional model of cultural congruence: Framework for intervention. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 6(3–4), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2010.529023

Slaughter-Acey, J. C., Caldwell, C. H., & Misra, D. P. (2013). The influence of personal and group racism on entry into prenatal care among African American women. Women’s Health Issues, 23(6), e387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2013.08.001

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Cedar Sinai Community Benefit Giving Office. The authors also appreciate Maura Georges for providing advice and feedback on this manuscript.

Funding

Cedar Sinai Community Benefit Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KLS: study design, recruitment, data collection, analysis, manuscript development. FS: recruitment, analysis, manuscript development. MK: study design, recruitment, analysis, manuscript development. SDB: study design, analysis, manuscript development. SAL: study design, recruitment, data collection, analysis, manuscript development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study [00001522] was approved by the Research Integrity and Oversight Office, Institutional Review Board at the University of Houston.

Consent to Participate

Focus group participants provided written consent to participate in this study while virtual focus group participants and key informants were given the informed consent via e-mail and provided verbal consent, documented on the audio recording.

Consent for Publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, K.L., Shipchandler, F., Kudumu, M. et al. “Ignored and Invisible”: Perspectives from Black Women, Clinicians, and Community-Based Organizations for Reducing Preterm Birth. Matern Child Health J 26, 726–735 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03367-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03367-1