Abstract

Objectives To determine whether affluent-born White mother’s descending neighborhood income is associated with infant mortality rates (< 365 day, IMR). Methods Stratified and multilevel logistic regression analyses were completed on the Illinois transgenerational dataset of singleton births (1989–1991) to non-Latina White mothers (1956–1976) with an early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods (defined as the fourth quartile of income distribution). The breadth of descending neighborhood income was defined by mother’s neighborhood income at the time of delivery. Results Infants of White mothers (n = 4890) who did not suffer descending neighborhood income by the time of delivery had a first-year mortality rate of 5.1/1,000. Infants of White mothers who experienced minor (n = 5112), modest (n = 2158), or extreme (n = 339) descending neighborhood income had IMR of 6.5/1,000, 14.4/1,000, and 11.8/1,000, respectively; RR [95% CI] = 1.3 [0.8, 2.1], 2.8 [1.7, 4.8], and 2.3 [0.8, 6.6], respectively. The incidence of young maternal age, inadequate prenatal care utilization, and cigarette smoking rose as descending neighborhood income increased, p < 0.01. In multilevel logistic regression models, the adjusted (controlling for selected individual-level co-variates) OR [95% CI] of infant mortality for White women with an early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who subsequently experienced minor or modest to extreme (versus absent) descending neighborhood income equaled 1.0 [0.6, 1.8] and 2.1 [1.1, 3.8] respectively. Conclusions White mother’s modest to extreme descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods is associated with a twofold greater risk of infant mortality independent of selected biologic, medical, and behavioral characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

What is known about this subject? The infant mortality rate of non-Latino Whites in the United States exceeds that of twenty-seven developed nations. The limited available literature suggests a need for greater research attention to the role of social inequity based on neighborhood class across the life-course in explaining the elevated IMR among US-born Whites.

What this study adds? White mother’s modest to extreme descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent urban neighborhoods is a novel risk factor for infant mortality (including its neonatal and post-neonatal components). This finding is salient to the racial disparity in IMR.

Introduction

Despite leading the developed world in advances in neonatal intensive care, the United States consistently ranks near the bottom in infant mortality rates (Osterman et al. 2015). The twofold greater infant mortality rate (< 365 day, IMR) of African-Americans (compared to non-Latino Whites) is a leading explanation of this public health embarrassment. However, the IMR of non-Latino Whites in the United States has two perplexing features. First, it exceeds that of twenty-seven developed nations, with White infants born in the US twice as likely to die in their first year of life as infants born in Finland (Hamilton et al. 2013; David and Collins 2014). Second, although preterm birth (< 37 weeks, PTB) is a major risk factor for first year mortality, US-born non-Latina White women actually have a twofold greater term (37–42 weeks) IMR than those of foreign-born White women (Collins et al. 2013). Both findings are supportive of life-course conceptual models of reproductive health and provide evidence that unidentified contextual factors directly linked to early-life, childhood, and adulthood residence in the US are harmful to infant outcome in the majority population (Geronimus 2013; Gluckman et al. 2008; Misra et al. 2003; Lu and Halfon 2003).

The available literature strongly supports the need for greater research attention on the relationship between social inequity across the life-course of White women and infant mortality (David and Collins 2014; Rodwin and Neuburg 2005; Kawachi et al. 2005; Isaacs and Schroeder 2004; David and Messer 2011). Given the high the prevalence of downward economic mobility among a large percentage of American families (University of Michigan 2013), the impact of White women’s descending neighborhood income between early-life and child-bearing age may be particularly important in helping us understand and lower their high IMR. An earlier exploratory study revealed that White women who experienced any level of downward economic mobility had a 2.4-fold greater risk of PTB than their counterparts with a lifelong residence in affluent communities independent of known biologic, medical, and behavioral characteristics (Collins et al. 2015). An incidental finding showed that those who experienced moderate to extreme downward mobility also had a greater IMR; however, the study did not explore whether this association was independent of individual-level variables risk factors. To our knowledge, no study has ascertained the relationship between White women’s descending neighborhood income, individual risk status, and infant mortality.

There are two components to infant mortality: neonatal (< 28 day) and post-neonatal (28–365 day). The majority of deaths to preterm infants occur in the neonatal period. As such, the lumping of both components into a single category may mask potentially disparate etiologic processes. For example, deaths due to congenital anomalies are leading cause of first-year mortality; whereas short gestation (< 37 weeks) is the leading cause of neonatal mortality, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the leading cause of death in the post-neonatal period (MMWR 2005). Most pertinent, neighborhood poverty during infancy is an established risk factor for overall and SIDS-specific post-neonatal mortality among White infants (Malloy and Eschbach 2007; Papacek et al. 2002,). The extent to which affluent-born White women’s descending neighborhood income is associated with neonatal and particularly post-neonatal outcome is unknown.

We, therefore, analyzed the Illinois vital records and US census income data to ascertain.

the relationship between non-Latina White women’s descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent Chicago neighborhoods and infant mortality (including its neonatal and post-neonatal components), independent of individual-level characteristics at the time of delivery. We hypothesized that affluent-born White women’s descending neighborhood income is a contextual risk factor for infant mortality and that this phenomenon would be strongest in the post-neonatal period.

Methods

Illinois Transgenerational Birth-File (TGBF)

We created the Illinois TGBF with appended US census income information as previously reported (David et al. 2010). It includes 267,303 infant (born 1989–1991) birth records to linked to their mother’s (born 1956–1976) birth records. For mothers born in Chicago 1956–1961, the 1960 median family income of community area of residence was appended to the maternal records as census tract information was not coded. For mothers born in Chicago 1961–1976, the 1960 and 1970 median family income of census tract residence was appended to the maternal birth records. For infants born in Cook County, the 1990 median family income of census tract residence for those born in Chicago and the city of residence for those born in the surrounding suburbs were appended to the infant birth records. In Chicago, the 873 census tracts are discrete areas that approximate real neighborhoods; the 77 community areas contain roughly 10 census tracts.

Study Sample

The race and origin variables listed on the vital records were used to identify non-Latina White women. Neighborhood class status was empirically defined using quartiles of census tract or community area median family income. The study was restricted to singleton births of non-Latina White women (n = 12,499) who were themselves born in affluent (as defined by the fourth quartile of neighborhood income) Chicago neighborhoods and gave birth while residing in Chicago or the surrounding Cook County suburbs.

Descending Neighborhood Income

Women’s descending neighborhood income was defined as: none (habitation in the fourth quartile of neighborhood income at the time of birth and delivery), minor (habitation in the fourth quartile of neighborhood income at the time of birth and the third quartile of neighborhood income at the time delivery), modest (habitation in the fourth quartile of neighborhood income at the time of birth and the second quartile of neighborhood income at the time delivery), and extreme (habitation in the fourth quartile of neighborhood income at the time of birth and the first quartile of neighborhood income at the time delivery).

Statistical Analyses

Rates of infant (< 365 day), neonatal (< 28 day), and post-neonatal (28–365 day) mortality were calculated according to maternal descending neighborhood income. Because of their well-documented association with adverse birth outcome, we empirically selected maternal birth weight, age, parity, adequacy of prenatal care (Kotelchuk 1994), and cigarette smoking as co-variates. Within each stratum of maternal descending neighborhood income, the incidence of the selected individual-level characteristics was determined. We then computed infant mortality (IM), neonatal (NM), post-neonatal mortality (PNM) rates according to descending neighborhood income and level of measured confounders. Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, using women who did not suffer descending neighborhood income between birth and the time of delivery as the comparison cohort (SAS 2000).

To more fully examine the independent association between descending neighborhood income and infant outcome, we performed multivariable logistic analyses. Multilevel multivariable logistic regression models were crafted to account for the nesting of individual births (level 1) within adulthood neighborhood (level 2) (Snijders 1999). The selected confounders were entered as discrete (i.e. categorical) co-variates. The adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI were derived from the final models by calculating the antilogarithm of the Beta-coefficients for each independent variable and the CI for those coefficients. All analyses were completed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS, 2000).

Results

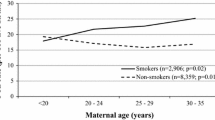

White women’s descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods was associated with infant mortality rates (Fig. 1). Since a small number of White women (n = 339) experienced extreme descending neighborhood income, we lumped them with the modest subgroup for subsequent analyses. The first-year mortality rate of births to White women (n = 2497) with early-life habitation in affluent areas who experienced modest to extreme descending neighborhood income by the time of delivery was nearly three times that of those (n = 4890) who do not experience descending neighborhood affluence by the time of their infant’s birth: 14/1000 vs 5.1/1000, respectively; RR = 2.7 [1.6, 4.6]. This disparity existed in both the neonatal (7.6/1000 vs 3.3/1000, RR = 2.3 [1.2, 4.5]) and post-neonatal (6.4/1000 vs 1.8/1000, RR = 3.5 [1.5, 7.9]) periods, respectively.

The incidence of the measured co-variates (i.e. young maternal age, inadequate prenatal care utilization, and cigarette smoking) rose as neighborhood affluence increased (Table 1). Approximately 20% of White women with early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who experienced modest to extreme descending neighborhood income were < 20 years of age compared to only 3% of those who did not experience descending neighborhood income. Similarly, the former had a nearly a 2.5-fold greater incidence of cigarette smoking (Table 1).

Table 2 shows rates of IM according to affluent-born White women’s descending neighborhood income and selected characteristics. Across the measured individual-level variables, White women with early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who experienced minor descending neighborhood income had rates of IM similar to that of those who had a lifelong residence in affluent neighborhoods. In contrast, the rates of IM for White women with low risk individual characteristics who experienced modest to extreme descending neighborhood income tended to exceed that of those who did not experience descending neighborhood income. Among women who received intermediate or adequate prenatal care and experienced descending neighborhood income had nearly a fourfold greater IMR than their counterparts who had a lifelong residence in affluent areas. A similar wide disparity occurred non-smokers.

Table 3 shows rates of NM according to White women’s descending neighborhood income and level of measured maternal biologic, medical, and behavioral characteristics. Those who experienced modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood income tended to have greater rates of NM across the measured characteristics. Among non-cigarette smokers with an early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who experienced modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood income had a threefold greater NM.

Table 4 shows rates of PNM according to White women’s descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods and level of measured biologic (birth weight, age, parity), medical (adequacy of prenatal care utilization), and behavioral (cigarette smoking) characteristics. No singular risk factor accounted for the association of descending neighborhood income and rates of PNM; disparities in the rates of PNM tended to persist among the lowest risk subgroups with those who experienced modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood affluence having the greatest rates.

In multilevel logistic models, the adjusted (controlling for measured maternal birth weight, age, parity, prenatal care usage, cigarette smoking) OR of IM for White women with early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who subsequently suffer slight or modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood income equaled 1.0 [0.6, 1.8] and 2.1 [1.1, 3.6], respectively. The adjusted OR of NM for White women with early-life residence in affluent neighborhoods who subsequently experience minor or modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood income were 0.9 [0.4, 1.9] and 2.0 [0.9, 4.2], respectively. The adjusted OR of PNM for White women with early-life residence in higher income areas who experienced minor or moderate to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood affluence equaled 1.2 [0.5, 3.2] and 2.2 [0.8, 6.1], respectively.

Discussion

The present study provides novel data highlighting a relationship between non-Latina White women’s descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent urban neighborhoods and infant (including its neonatal and post-neonatal components) mortality. In Chicago, the majority of affluent-born White mothers experience descending neighborhood income between birth and their childbearing years. Most striking, we found that White women with early-life residence in affluent or upper-class communities who subsequently experience modest to extreme (compared to no) descending neighborhood income have nearly a threefold IMR. This appears to be largely a contextual phenomenon independent of selected biologic (i.e. maternal birth weight, age, parity), medical (i.e. prenatal care usage), and behavioral (i.e. cigarette smoking) characteristics. Interestingly, White woman’s descending neighborhood income is similarly associated with rates of neonatal and post-neonatal mortality.

To understand the U.S. dismal international ranking in rates of IM we must look upstream from the biomedical level (David and Collins 2014; Schroeder 2007). This includes looking beyond the heterogeneous racial/ethnic make-up of the U.S. population as the sole explanation for this long standing public health problem. Nearly 11 million Americans reside in approximately three thousand extremely poor neighborhoods in and around America’s largest cities (CityLab.com 2014). For each gentrified neighborhood, twelve once-stable neighborhoods have slipped into concentrated disadvantage (CityLab.com 2014).

Our data provide empiric evidence of the first-year mortality consequences of White women’s descending urban neighborhood income. Although maternal descending neighborhood income is associated with an increased prevalence of individual risk factors (LBW, young age, high parity, inadequate prenatal care utilization, and cigarette smoking), the point estimates of association of White women’s modest to severe descending neighborhood income and rates of IM approximates two when these characteristics are mathematically controlled. A contextual process related to inequity based on class seems most plausible. Affluent-born White women’s descending neighborhood income may result in exposure to chronic stressors (i.e. gun violence, limited access to fresh foods, and poor walkability) which results in poor population health in general and high infant mortality in particular. However, unmeasured individual-level characteristics closely linked to neighborhood class merits consideration. Croteau et al. (2007) reported that women in Quebec who experienced job strain had a twofold greater risk of PTB (15). As such, job strain may explain the association of socioeconomic status and birth outcome (Bravemen et al. 2010). Descending neighborhood income may also identify White women who are chronically disappointed with their lower social and financial standing. This could contribute to their cumulative allostatic stress load and subsequently trigger PTB. Additionally, the unidentified factors that cause affluent-born White women to reside in lower income neighborhoods by the time of delivery, not descending neighborhood income per se, may be causally associated with infant mortality.

Notwithstanding the different leading etiologies of neonatal (i.e. PTB) and post-neonatal (i.e. SIDS), our data show that the relationship between White women’s modest to extreme descending neighborhood income and mortality is actually similar in both the neonatal and post-neonatal periods. These findings suggest that affluent-born White women’s exposure to descending neighborhood incomes is a proxy measure of unsafe infant sleep practices which are risk factors for SIDS and consequent post-neonatal mortality. More detailed population-based studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to determine the relationship between affluent-born White women’s deterioration in neighborhood income across their life-course and cause-specific rates of infant, neonatal, and post-neonatal mortality.

The sub-group of affluent-born White women who experience minor (compared to no) descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent urban neighborhoods do not have an elevated IMR (including its neonatal and post-neonatal components). This finding suggests that a possible threshold level of neighborhood income deterioration is needed before negatively impacting infant survival. We encourage researchers to take White women’s degree of descending neighborhood income into account when examining neighborhood class disparities in infant mortality rates.

The present study is salient to the long standing African-American infant’s survival disadvantage. The first-year mortality risk of births to affluent-born White women who experience moderate to extreme descending neighborhood income actually approximates that of the general African-American population (Osterman et al. 2015). In contrast, the first-year mortality risk of births to affluent born White women who do not experience descending neighborhood income is approximately one-third that of African-Americans. These observations provide compelling evidence that lower class status (as measured by neighborhood income) is an important, but not the only, major component of the racial disparity in infant mortality rates. We speculate that descending neighborhood income is more detrimental to the IMR of affluent-born African-American (compared to White) urban women because of their concurrent exposure to decreasing class status and racial discrimination (David and Collins 2014; Kawachi et al. 2005; David and Messer 2011).

The present study benefits from two generations of vital records with appended neighborhood income data; however, it has four major limitations. First, we were unable to disentangle the impact of affluent-born White women’s geographic movement to lower income urban neighborhoods vs residence in urban neighborhoods that economically deteriorated. Second, although we assessed women’s neighborhood income at the time of birth and at the time of their infant’s birth, we had no information on the intervening time interval. Third, the sample of White women who experienced extreme descending neighborhood income was small and did not allow for in depth analyses. Lastly, our infant outcome data are approximately 25 years old and may not be generalizable to current birth outcome. However, the disparity in the first-year mortality rates between White infants in the US and those in other developed countries has actually widened. We support the creation of a more contemporary transgenerational birth-files with appended infant death records and objective measures of neighborhood income to confirm and extend our findings.

In summary, non-Latina White women’s modest to extreme descending neighborhood income from early-life residence in affluent urban neighborhoods is associated with increased infant mortality rates (including its neonatal and post-neonatal components) independent of selected biologic, medical, and behavioral risk factors. More comprehensive epidemiologic investigations and public health attention are warranted.

References

Braveman, P. A., Cubbin, C., Egerter, S., Williams, D. R., & Pamuk, E. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S186–S196.

Collins, J., Rankin, K., & David, R. (2015). Downward economic mobility and preterm birth: An exploratory study of Chicago-born upper class white mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 1601–1607.

Collins, J. W., Soskolne, G., Bennett, A., & Rankin, K. (2013). Differing mortality rates among term infants of US-born and foreign-born White, African-American, and Mexican-American mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 1776–1783.

Croteau, A., & Marcoux, S., Brisson, C. (2007). Work activity, preventive measured, and the risk of preterm delivery. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166, 951–965.

David, R., & Messer, L. (2011). Reducing disparities: race, class, and the social determinants of health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, S1–S3.

David, R. J., & Collins, J. W. (2014). Layers of inequality: power, policy, and health. American Journal of Public Health, 104, S8-S10.

David, R. J., Rankin, K. M., Lee, K., Prachand, N. G., Love, C., & Collins, J. W. (2010). The Illinois transgenerational birth file: life course analysis of birth outcomes using vital records and census data over decades. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14, 121–132.

Geronimus, A. T. (2013). Deep integration: Letting the epigenome out of the bottle without losing sight of the structural origins of population health. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S1), S56–S63.

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Cooper, C., & Thornburg, K. L. (2008). Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. NEJM, 359, 61–73.

Hamilton, B. E., Hoyert, D. L., Martin, J. A., Strobino, D. M., & Guyer, B. (2013). Annual review of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics., 131, 548–558.

Isaacs, S. L., & Schroeder, S. A. (2004). Class-the ignored determinant of the nation’s health. The New England Journal of Medicine, 35, 1137–1142.

Kawachi, I., Daniels, N., & Robinson, D. (2005). Health disparities by race and class: Why both matter. Health Affairs (Millwood), 24, 343–352.

Kotelchuk, M. (1994). The adequacy of prenatal care utilization index: Its US distribution and association with low birth weight. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 1486–1489.

Lu, M., & Halfon, N. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7, 13–30.

Malloy, M., & Eschbach, K. (2007). Association of poverty with sudden infant death syndrome in metropolitan counties of the United States in the years 1990 and 2000. Southern Medical Journal, 100, 1107–1113.

Misra, D., Guyer, B., & Aliston, A. (2003). Integrated perinatal health framework: A multiple determinants model with a life span approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 65–75.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (2002). Quick Stats: Leading Causes of Neonatal and Postneonatal Deaths—United States. Retrieved May 19, 2018 from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5438a8.htm.

Osterman, M. K., Kochanek, K. D., MacDorman, M. F., Strobino, D. M., & Guyer, B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2012–2013. Pediatrics. 2015;135, 1115–1125.

Papacek, E. M., Collins, J. W., Schulte, W. F., Goergun, C., & Drolet, A. (2002). Differing postneonatal mortality rates of African-American and white infants in Chicago: An ecologic study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 6, 99–115.

Rodwin, V. G., & Neuburg, L. G. Infant mortality in four world cities: New York, London, and Toyko. American Journal of Public Health, 2005;95:86–90.

SAS Institute Inc., SAS 9.1.3 SAS/STAT. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2000–2004.2.

Schroeder, S. A. (2007). We can do better improving the health of the American people. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 171–179.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

University of Michigan National Poverty Center. Poverty in the United States. Retrieved May 18, 2018 from http://www.npc.umich.edu/poverty/#2.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by March of Dimes Foundation (Grant Nos. 12-FY09-159 and 21-FY16-111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, J.W., Colgan, J., Rankin, K.M. et al. Affluent-Born White Mother’s Descending Neighborhood Income and Infant Mortality: A Population-Based Study. Matern Child Health J 22, 1484–1491 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2544-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2544-8