Abstract

Despite the well-established relationship between early experiences of victimization and later re-victimization, little is known about the exact mechanism of this cycle of victimization. The present study examined whether the route from rejection sensitivity to aggression mediates the associations between different forms of childhood abuse and later peer victimization longitudinally. A total of 3525 adolescents (56.6% male; Mage = 13.21 ± 0.85) participated in this three-wave study, with a 6-month lag and a 9-month lag respectively. The results indicated that the association between childhood emotional abuse and peer victimization were independently mediated by aggression, and sequentially mediated by rejection sensitivity and aggression in both sexes. Sex differences existed regarding the association between childhood physical abuse and aggression, such that only in adolescent boys did physical abuse show significant effect on aggression, resulting in later peer victimization. In general, these findings suggest that maladaptive social-cognitive processes and behavioral patterns are crucial for understanding the mechanism of the vicious cycle of victimization, and sex differences must be considered when examining different types of childhood abuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peer victimization refers to the harm caused by other peers acting outside of the norms of appropriate conduct, including both direct and indirect forms (Finkelhor et al., 2012). Peer victimization has become a major social problem for children and adolescents across the world (Arseneault et al., 2010), hampering their mental health (Ybrandt & Armelius, 2010), and resulting in serious long-term maladaptation (Olweus, 2013). In China, researchers found that a total of 42.9% of Chinese adolescents had suffered from victimization by peers (Chen et al., 2018), which is higher than the international prevalence, and also leads to mental problems (Koyanagi et al., 2019). Understanding the risk antecedents and mechanisms leading to peer victimization is important for developing related interventions and policies. Early childhood victimization, such as childhood abuse are associated with later victimization. This study aimed to examine the effects of childhood emotional and physical abuse on later peer victimization with a large-sample, longitudinal dataset and investigated the mediating role of rejection sensitivity and aggression in the relationships between childhood abuse and later peer victimization.

Cycle of Victimization: Childhood Abuse and Adolescent Peer Victimization

Childhood abuse is a major public health issue that has severe social and individual consequences (Tolan et al., 2006). The organizational perspective of development posits that mental structures shaped by previous experiences are incorporated into subsequently emerging ones (Cicchetti, 2016). This suggests that maltreated children internalize their relationships with their caregivers (McDowell & Parke, 2009), further disrupting their interactions with peers (Banny et al., 2013). In line with this perspective, the ecological-transactional model of child abuse hypothesizes that childhood abuse could lead to subsequent peer problems, especially peer victimization (Cicchetti et al., 2000), resulting in a cycle of victimization (Widom, 2014). Previous researches demonstrate relationship between childhood abuse and peer victimization (Lereya et al., 2013), that childhood maltreatment (e.g., childhood abuse) increased exposure to other types of victimization in adolescence (Radford et al., 2013).

Although numerous works establish the associations between childhood abuse and peer victimization, most of these works focus on childhood maltreatment and peer victimization as a whole (Yoon et al., 2021), or the specific associations between childhood sexual abuse and sexual re-victimization in adulthood (Fereidooni et al., 2023). According to the interconnection theory of interpersonal violence (Hamby & Grych, 2013), examination of a certain type of childhood abuse in isolation could result in insufficient understanding of its impacts since that different childhood abuse could confound the effects of each other. Among categories of childhood abuse, emotional and physical abuse are more prevalent compared to sexual abuse and could cause severe developmental consequences (Stoltenborgh et al., 2015). More importantly, emotional and physical abuse have a high rate of co-occurrence but traverse varying mechanisms to result in different consequences including peer victimization (e.g., Gardner et al., 2019). Therefore, inclusion of both emotional and physical abuse would help unveil and clear out the mechanisms between them. Additionally, peer victimization has also been proposed to be consisted of direct (e.g., physical, verbal) and indirect (e.g., relational) forms, which are distinct (Finkelhor et al., 2012), and associated with varying maladaptation (Casper & Card, 2017). However, existing work on the link between childhood emotional and physical abuse and different forms of victimization is limited. Moreover, most work conducted in Chinese context utilized cross-sectional designs (e.g., Xiao et al., 2021), leaving the longitudinal effects of childhood abuse on peer victimization unexplored. To better examine the associations between both childhood emotional and physical abuse and peer direct and indirect victimization in Chinese adolescents, longitudinal studies that include baseline levels of peer victimization are needed (Goemans et al., 2023).

Aggression as a Potential Mediator

Although cumulative work has shown that childhood abuse can lead to re-victimization at some point during the lifespan, the mechanisms through which childhood abuse exerts its influence remain unclear (Benedini et al., 2016). The ecological-transactional model of child abuse posits that childhood abuse could lead to a range of regulatory deficits, such as heightened aggression, which in turn impede the achievement of future developmental tasks (e.g., formation of peer relations; Cicchetti & Toth, 2009). This ultimately indicates that aggression might be a crucial factor linking childhood abuse and peer victimization. Aggression refers to behaviors directed toward another individual with the proximate intent to cause harm (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Previous study found relationships between childhood abuse and aggression (Card et al., 2008), such that childhood abuse could result in heightened aggression (Rogosch et al., 2009). Also, numerous researches showed that aggressive behaviors are associated with higher levels of peer victimization (e.g., Cooley et al., 2017). Moreover, several studies examined the potential role of aggression in the relationship between childhood abuse and peer problems and found significant mediated effects of aggression. For example, aggressive behaviors significantly mediated the relationships between childhood maltreatment and peer problems, such as peer conflict (Handley et al., 2019), and peer rejection (Bolger & Patterson, 2001). However, existing work examining the role of aggression has mainly focused on the effects of childhood maltreatment as a whole on peer relationships (e.g., Allen et al., 2021), overlooking the effects of specific types of childhood abuse on peer victimization. Thus, the potential role of aggression in the relationship between childhood emotional and physical abuse and peer direct and indirect victimization remains unclear. To fill this gap, the first aim of the current study was to examine the potential mediating role of aggression on both childhood emotional and physical abuse and peer direct and indirect victimization in adolescence.

Rejection Sensitivity as Potential Mediator: Proceed toward Aggression

Rejection sensitivity refers to an individual’s tendency to anxiously or angrily expect and readily perceive rejection, even if the rejection does not actually exist (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2016). Rejection sensitivity is proposed to be a crucial factor in the pathway from early victimization to later peer victimization. According to the rejection sensitivity model (Downey, Freitas et al., 1998), poor social affiliation and attachment caused by early childhood rejecting environments (e.g., abuse) lead to biases in social cue processing, frequently manifesting as heightened sensitivity to rejection. This in turn results in misinterpretation of peers’ social behaviors and further increases the possibility of being victimized (London et al., 2007). Previous research showed potential relationships between childhood abuse, rejection sensitivity, and peer victimization (Berenson & Andersen, 2006), indicating that rejection sensitivity is associated with childhood abuse (Xu et al., 2022) and experiences of victimization (Gao et al., 2021). Only few studies have examined the potential role of rejection sensitivity in the relationship between childhood abuse and later victimization, with one study conducted in adult interpersonal context with only female sample (Kahya, 2021) and the other conducted using a cross-sectional design (Li et al., 2023). Thus, the role of rejection sensitivity in the longitudinal relationship between childhood abuse and victimization in an adolescent peer context is still unclear especially with a focus on different subtypes of childhood abuse. Therefore, the second aim of the current study was to investigate the mediating effect of rejection sensitivity on the association between both emotional and physical abuse and peer direct and indirect victimization.

When considering the potential mechanisms regarding how childhood abuse leads to peer victimization, a sequential route seems to be neglected in previous research. The model of cascading consequences of childhood abuse explicitly posits that the consequences of childhood abuse are multifaceted among which a cascade of developmental consequences, such as the interplay between cognitive and behavioral consequences on peer problems, can be spotted (Widom, 2014). In other words, the mechanisms of how childhood abuse leads to peer victimization are complex and can be better captured by developmental sequences. Researchers have begun to unveil the sequential mechanism of the cycle of victimization (e.g., Miller et al., 2022). For instance, prior research found that the interplay between externalizing problems and peer status linked early victimization with later one (Yoon et al., 2018). However, rejection sensitivity, being a crucial factor for carrying over consequences of interpersonal victimization from one setting to another through a heightened sense of aggression (Levy et al., 2006), has been overlooked. To better capture how the cycle of victimization occurs, it is necessary to consider the potential developmental pathway from rejection sensitivity to aggression.

Implied by the defensive motivational system hypothesis, rejection sensitivity does not lead to peer victimization directly, but via induced misbehaviors toward peers, such as aggression, which results in a pathway from rejection sensitivity to further aggression (Romero-Canyas et al., 2010). Furthermore, based on the convergent model of interpersonal difficulties, rejection sensitivity is one key factor resulting from early victimization and followed by a series of maladaptive outcomes (e.g., aggressive behaviors), which ultimately induce the emergence of future interpersonal difficulties, such as peer victimization (Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Empirical work has evidenced associations between rejection sensitivity and heightened aggression. For instance, previous research found that participants high in rejection sensitivity allocated significantly more hot sauce (loathed by the participant’s match and typically cause painful feelings) to cause unpleasant feelings to others, indicating higher levels of aggression (Ayduk et al., 2008). Additionally, a meta-analysis found that the association between rejection sensitivity and aggression was robust and significantly related to later victimization (Gao et al., 2021), further indicating that the association between rejection sensitivity and elevated aggression could be an important mechanism for explaining the cycle of victimization.

However, to date, no study has examined the potential developmental mechanism from rejection sensitivity to aggression in the cycle of victimization, or considered the distinction of different types of childhood abuse. As a result, the complex question of how exactly the cycle of victimization occurs remains unanswered. Therefore, the third aim of the current study was to examine the potential sequential route from rejection sensitivity to aggression in the relationship between different forms of childhood abuse and peer victimization.

Sex Differences

Sex has also been considered an important factor accounting for variation in the manifestation of the cycle of victimization. Sex differences in childhood abuse, peer victimization, rejection sensitivity, and aggression have separately been identified. For instance, among Chinese adolescents, girls experienced relatively lower levels of both emotional and physical abuse and significantly higher levels of consequent maladaptation compared to boys (Xiao et al., 2020). Further, girls experience significantly higher levels of peer victimization (Arseneault et al., 2010) and manifest heightened rejection sensitivity when compared to boys (Maiolatesi et al., 2022). As for aggression, males typically perpetrate more aggressive behaviors than females (Zeichner et al., 2003). Although sex differences in each variable of interest were found in previous work, whether sex impacts the associations between these variables is unclear. Based on the convergent model of interpersonal difficulties, childhood abuse could result in differential developmental routes across sexes, especially those associated with rejection sensitivity due to the varying processes of sex socialization for males and females (Lesnick & Mendle, 2021). Few studies have examined sex differences in the cycle of victimization, and results have been mixed. For instance, prior work found that relationships between childhood abuse and peer victimization were similar across sexes (Benedini et al., 2016), whereas another study found that although childhood abuse increased the odds of being victimized in both sexes, the mechanisms leading to this re-victimization were different across sexes (Miller et al., 2022). This indicates that sex differences might be expressed through the mechanisms of the victimization cycle instead of through a direct relationship between childhood abuse and victimization. Furthermore, previous work concerning sex differences primarily focused on the direct associations between childhood abuse and victimization. The potential effects of sex on the mechanisms of childhood abuse leading to later victimization in an adolescent peer context is still unclear. Therefore, the last aim of the current study was to investigate the moderating effects of sex on the mechanisms of the cycle of victimization.

Current Study

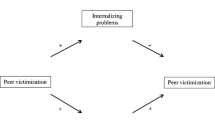

Prior studies have examined the associations between childhood victimization and later re-victimization in adolescence, while little is known about the mechanisms of this vicious cycle. This study fills this gap by investigating pathways from different forms of childhood abuse to peer victimization in Chinese adolescents. Specifically, the current study sought to examine whether different forms of childhood abuse initiate a developmental pathway that results in peer victimization via rejection sensitivity and aggression, which were considered separately and sequentially, while also accounting for sex effects. To exploratorily probe whether different forms of peer victimization matter, peer victimization was also split into direct and indirect forms. The current study hypothesized that both types of childhood abuse would be associated with increased later direct and indirect peer victimization (Hypothesis 1), and rejection sensitivity and aggression would independently mediate the relationships between both forms of childhood abuse and peer victimization (Hypothesis 2 & 3). Additionally, rejection sensitivity would impact direct and indirect peer victimization through a developmental sequence of heightened aggression, explaining the relationship between childhood abuse and peer victimization (Hypothesis 4). Moreover, considering the potential sex differences in the relationships and mechanisms between childhood abuse and peer victimization, an exploratory multigroup analysis was conducted to probe the potential differences of the aforementioned mechanisms across sexes. The current study hypothesized that significant sex differences in the mechanisms between childhood abuse and peer victimization can be found (Hypothesis 5). The hypothesized model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The data were collected from a three-wave longitudinal survey conducted in three middle schools located in Northern China. A total of 3924 healthy adolescents (58% male; Mage = 13.22 ± 0.86) in grades 7 and 8 were recruited in winter 2021 (T1). In summer 2022 (T2), 97.58% (N = 3829) adolescents from the original sample participated in the second survey. The data collection in wave 3 were conducted in the spring semester of 2023 (T3). In wave 3, 22.38% participants of the original sample (N = 878) dropped out and a majority of them (N = 717) were due to the known reason of participation of senior high school entrance examination at grade 9. The Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test (Little, 1988) was applied to examined the pattern of missing data across the measurements and yielded a value of χ2/df=4 = 2.219, p = 0.696 for missingness at T2 and a value of χ2/df=4 = 299.443, p < 0.05 for missingness at T3. These results indicated that the missingness at T3 may not completely at random (MCAR). While, significant value of the MCAR test did not rule out the possibility of missing at random (MAR). Further independent-variance t tests were conducted and yielded significant t values for the outcome variables at T3 regarding participants’ age and household income. Values of t/df=1595.5 = − 17.6, p < 0.01 and t/df=1575.4 = 4.2, p < 0.01 were yielded, indicating missing value of peer victimization at T3 largely depended on participants’ age and household income respectively, which is partially in line with the majority of missing participants at grade 9. Participants took part in at least one survey around the three timepoints were retained for subsequent analysis. Imputation with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used for missing data, which is suitable for both MCAR and MAR (Shin et al., 2017). Additionally, five instructed response items (e.g., “Please choose ‘strongly agree’ for this item.”) were included in the surveys to detect careless responses (Ward & Meade, 2023). A total of 399 participants were excluded from the final sample for reasons including responding to the questionnaires carelessly, completing the surveys with unusually short periods of time, etc. Therefore, the final sample included 3525 adolescents (56.6% male; Mage = 13.21 ± 0.85). The majority of the parents of participating adolescents had an educational level of middle school (nfather = 1662, nmother = 1708). Most of the parents stayed married during data collection (n = 3246). The median household income of the participating families was 4000–6000 CNY (approximately US $ 550.81–826.22) per month.

Childhood abuse, rejection sensitivity, and all the covariates were measured at T1. Aggression was measured at T2. Peer victimization was measured at both T1 and T3. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and their parent(s)/caregivers prior to the study. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, that all the collected data would be kept confidential, and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time during data collection. The questionnaires took approximately 30 min to complete. Trained researchers administered the self-report questionnaires to the students in class during regular school hours. After the survey, each participant received a gift of pens and notebooks. This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Human Participant Protection, Faculty of Psychology at Beijing Normal University.

Measures

Childhood abuse (T1)

Childhood abuse was measured using the translated version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003), which has been widely used in Chinese adolescents, demonstrating adequate reliability and validity (Zhang, 2011). The original CTQ-SF consisted of 28 items asking participants to recall their upbringing up until their age of 12 at most. Questions related to different domains of childhood maltreatment, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, etc. The emotional and physical abuse subscales were used in the present study. In total, 10 items (e.g., “Family members have hit me hard enough to leave bruises or marks.”) were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The average score of the items was calculated as the final score for childhood emotional and physical abuse, with higher scores reflecting more severe experiences of childhood abuse. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.81, 0.60, and 0.61 for the total scale, emotional abuse subscale, and physical abuse subscale, respectively.

Rejection sensitivity (T1)

Rejection sensitivity was measured using the translated version of the Tendency to Expect Rejection Scale (Jobe, 2003), which has been shown to be valid and reliable in Chinese adolescents (Li, 2004). Eighteen items (e.g., “I am sensitive to rejection.”) asking the participants’ sensitivity to rejection in daily life were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The average score of the items was calculated as the final score for rejection sensitivity, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of rejection sensitivity. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.78.

Aggression (T2)

Aggression was measured using the Chinese revised version of the Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006), which has been shown to be valid and reliable in Chinese adolescents (Fu et al., 2009). The questionnaire consisted of two subscales, proactive aggression and reactive aggression. A total of 23 items (e.g., “Used physical force to get others to do what you want”) were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), asking participants about the frequency of their own aggressive behavior in the past six months. The average score of the items was calculated as the final score for aggression, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of aggression. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.90.

Peer victimization (T1 & T3)

Peer victimization was measured using the translated version of the Multidimensional Peer-victimization Scale (Mynard & Jose, 2000), which has been shown to be valid and reliable in Chinese adolescents (Guo et al., 2017). Eighteen items (e.g., “Hurt me physically in some way”) were measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often). The questionnaire asked participants about their experiences of being bullied in the past semester, which can be divided into direct and indirect forms of victimization (Attar-Schwartz & Khoury-Kassabri, 2015), with direct form indicating being direct targets of bullying (e.g., being physical assaulted, being cursed), and indirect form being targets of manipulation of interpersonal relationships (e.g., rumors being spread, being social isolated). The average score of the items in each form was calculated as the final score for direct and indirect peer victimization, with higher scores reflecting more experiences of being bullied in certain ways. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.90 and 0.94 at T1 and T3, respectively.

Covariates (T1)

The present study included peer victimization and several demographic variables collected at T1 as covariates. Demographic covariates include sex (0 = male, 1 = female) and age of the adolescents, as well as parental educational level, marital status, and household income. To account for potential confounding effects of experiences of actual ostracism on related variables, such as aggression (e.g., Ladd, 2006), experience of ostracism was also included as covariate. Experiences of ostracism was measured by the Ostracism Experience Scale for Adolescents (OES-A) (Gilman et al., 2013). Eleven items (e.g., “Others treat me as if I am invisible”) were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The average score of the items was calculated, with higher scores representing higher frequency of being excluded by others. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.86.

Statistical Analysis

First, the descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations for all the variables of interest were calculated. Second, after controlling the baseline levels of direct and indirect peer victimization and all other covariates, the sequential mediation model of the effect of childhood abuse on T3 peer victimization through T1 rejection sensitivity and T2 aggression was examined in Mplus 8.3. Maximum likelihood with robust standard errors was used for more precise parameter estimation. Suggested by Hayes (2009), bootstrapping (N = 5000) was used to estimate the total and indirect effects and their confidence intervals (CIs). The 95% CIs generated from bootstrapping were reported for the mediated effects. CIs that did not include zero indicate a statistically significant mediated effect. Fourth, tests of multigroup comparison of the mediation models by sex were conducted in Mplus 8.3. Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square were calculated to compare differences between the freely estimated and constrained models (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). When statistically significant differences between sexes existed, group comparison probing specific differences in regression pathways was conducted. Root means square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were reported to indicate goodness of model fit. According to prior research (Hu & Bentler, 1999), RMSEA less than 0.08, CFI close to or above 0.90, and SRMR less than 0.08 were considered as adequate model fits.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive information and bivariate correlations for each variable from wave 1 (T1) to wave 3 (T3) are presented in Table 1. Childhood emotional abuse was positively correlated with physical abuse. Both forms of childhood abuse were positively correlated with T1 rejection sensitivity, T2 aggression, and all forms of peer victimization at T3. T1 Rejection sensitivity was positively correlated with T2 aggression and all forms of peer victimization at T3. T2 aggression was positively correlated with all forms of peer victimization at T3. Different forms of peer victimization at T1 and T3 were positively inter-correlated with each other. As for the covariates, sex was positively correlated with childhood emotional abuse, T1 rejection sensitivity, T1 ostracism, and indirect peer victimization, indicating that adolescent girls might have more experiences of childhood emotional abuse, ostracism, and peer victimization in indirect forms, as well as heightened rejection sensitivity. Age was positively correlated with childhood emotional abuse and different forms of peer victimization at both T1 and T3. Parental marital status was positively correlated with all variables of interest, indicating that adolescents whose parents stayed married might experience less childhood abuse and peer victimization, as well as showing less rejection sensitivity and aggressive behaviors.

Test of the Proposed Sequential Mediation Model

The proposed sequential mediation model adequately fit the data, χ2/df=24 = 401.188, p < 0.05, RMSEA = 0.067, CFI = 0.931, SRMR = 0.060. The total effects of childhood emotional abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization were b = 0.107, CI = [0.067, 0.146], and b = 0.072, CI = [0.031, 0.113], respectively. The total effects of childhood physical abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization were b = 0.100, CI = [0.055, 0.145], and b = 0.108, CI = [0.059, 0.158], respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, when adding the mediating variables into the model, the direct effect of childhood emotional abuse on T3 indirect peer victimization was rendered insignificant (b = 0.014, CI = [−0.026, 0.055]), while the direct effects from childhood physical abuse to both forms of peer victimization at T3, as well as childhood emotional abuse to T3 direct peer victimization remained significant.

The sequential mediation model of the effects of childhood abuse on peer victimization through rejection sensitivity and aggression. Note. Significant standardized coefficients are reported. Baseline peer victimization, ostracism experiences, sex, age, parental educational level, parental marital status, and household income were included as covariates for the examination but not shown in the figure. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, the effect of childhood emotional abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization were mediated by T1 rejection sensitivity and T2 aggression. Specifically, childhood emotional abuse influenced T3 direct and indirect peer victimization through the sole mediating role of T2 aggression, explaining 42.06% and 48.61% of the total effects respectively. Furthermore, although childhood emotional abuse was significantly associated with T1 rejection sensitivity, T1 rejection sensitivity failed to predict T3 direct and indirect peer victimization directly. Instead, a sequential mediation chain from T1 rejection sensitivity to T2 aggression was significant in the model to both forms of peer victimization, explaining another 17.76% and 20.83% of the total effects of childhood emotional abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization respectively.

However, the same mediation pattern of childhood emotional abuse was not found for childhood physical abuse. Childhood physical abuse only significantly predicted T2 aggression (b = 0.104, p < 0.01). The association between childhood physical abuse and T1 rejection sensitivity was not significant (b = 0.004, p = 0.837). Therefore, the effect of childhood physical abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization was only mediated by T2 aggression, explaining 32% and 23.15% of the total effects respectively.

Multigroup Analysis

To further explore sex differences of the effects of childhood abuse on peer victimization, a multigroup analysis was conducted. The results showed that the fit of the mediation model in which parameters were freely estimated for each sex (Model 0) was superior to the model with constrained parameters across all covariates (Model 1; Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 = 30.747, Δdf = 18, p < 0.05). This indicated significant differences between the effects of the covariates for each sex. Further, Model 1 showed a better fit than the mediation model with constrained parameters across coefficients of both covariates and variables of interest (Model 2, Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 = 28.621, Δdf = 13, p < 0.01), indicating significant differences between the whole models for each sex. Taken together, pathways linking childhood abuse and peer victimization showed significant differences across sexes. To probe the differences between specific regression pathways, the sequential mediation model was then tested separately in male and female adolescent groups.

The models adequately fit the data in both groups (Model male: χ2/df=23 = 223.803, p < 0.05, RMSEA = 0.066, CFI = 0.936, SRMR = 0.064; Model female: χ2/df=23 = 189.505, p < 0.05, RMSEA = 0.069, CFI = 0.930, SRMR = 0.062). As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the effect of childhood emotional abuse on T3 direct and indirect peer victimization through T1 rejection sensitivity and T2 aggression across sexes showed the same pattern. However, the effects of childhood physical abuse on T3 peer victimization concerning the pathway of aggression showed significant differences between adolescent boys and girls. Specifically, for both sexes, childhood physical abuse had direct impacts on both forms of peer victimization. While compared to adolescent boys, the mediation effects of T2 aggression between childhood physical abuse and peer victimization in adolescent girls were rendered insignificant, leaving only the direct pathways significant. These results indicated different mechanisms between childhood physical abuse and later peer victimization across sexes.

The sequential mediation model of the effects of childhood abuse on peer victimization through rejection sensitivity and aggression in adolescent boys. Note. Significant standardized coefficients are reported. Baseline peer victimization, ostracism experiences, age, parental educational level, parental marital status, and household income were included as covariates for the examination but not shown in the figure. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The sequential mediation model of the effects of childhood abuse on peer victimization through rejection sensitivity and aggression in adolescent girls. Note. Significant standardized coefficients are reported. Baseline peer victimization, ostracism experiences, age, parental educational level, parental marital status, and household income were included as covariates for the examination but not shown in the figure. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Peer victimization is a major social problem for adolescents worldwide, often with severe consequences (Koyanagi et al., 2019). Investigating the causes of peer victimization in adolescence is of utmost importance for intervention. The current study aimed to determine whether different types of childhood abuse initiate a developmental pathway resulting in peer re-victimization in adolescence. Specifically, the current work investigated rejection sensitivity and aggression as potential individual and sequential mediators of the relationship between both childhood emotional and physical abuse and both direct and indirect peer victimization. The results showed partial support for the expected associations and these effects also varied across sexes.

Regarding the effect of childhood emotional abuse on peer victimization, the current work found evidence for direct effect from emotional abuse to direct peer victimization in the total sample, which is consistent with previous researches (e.g., Li et al., 2021). Moreover, an aggressive pathway from emotional abuse to both direct and indirect peer victimization were spotted in Chinese adolescents, in both the total sample and across sexes. Consistent with previous work, experiences of emotional abuse can increase aggression (Schwarzer et al., 2021), which may in turn disrupt peer relationships and result in intensified peer victimization (Kellij et al., 2023). According to the dual-pathway hypothesis, childhood abuse disrupts the child’s capability to form later peer relationships through either heightened exhibition of aggressive behaviors or withdrawn behaviors, which ultimately induce victimization (Cicchetti & Toth, 2015). Additionally, the current findings added to previous work that showed childhood maltreatment results in problematic peer interactions via increased relational aggression (Handley et al., 2019). The current work extended these findings by employing a sample of adolescents in Chinese culture and focusing specifically on the cycle of peer victimization in school that started with different childhood abuse.

Additionally, the current work found a significant developmental pathway from rejection sensitivity to aggression in the cycle of victimization that begins with childhood emotional abuse. This pattern was present both in the total sample and across sexes. Consistent with previous research, individuals with heightened levels of rejection sensitivity expressed more aggressive behaviors and encountered more interpersonal difficulties (Downey, Lebolt et al., 1998). Crick and Dodge (1994) proposed the social information-processing (SIP) theory to explain how perception and interpretation of social cues lead to peer response. According to SIP theory, interpersonal experiences in early stages shape the pattern of social information processing of an individual. Differential encoding and interpretation of social cues in a given social situation lead to different response enactments, such as aggressive behavior, which ultimately induce peer victimization. Therefore, experiencing emotional rejection by caregivers at an early age might result in the development of a rejection-sensitive information-processing style in adolescence (Feldman & Downey, 1994), making an individual prone to perceiving rejection in an ambiguous social situation. This misinterpretation could further lead to aggressive reactions and ultimately provoke peer victimization. In addition, contrary to prior research (Kahya, 2021), the current results showed that rejection sensitivity did not independently mediate the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and peer victimization. This finding is in line with a recent longitudinal work (Kellij et al., 2023). The current findings may indicate that, from a developmental perspective, rejection sensitivity resulting from emotional abuse may indirectly lead to later peer victimization through improper behavioral enactment. This also extends previous work (Kellij et al., 2023), suggesting that SIP theory is applicative to a certain cycle of victimization.

Regarding physical abuse, the current work found that physical abuse had relatively stable direct effects on direct and indirect peer victimization in the total sample and across sexes, which was consistent with previous study (Benedini et al., 2016). Moreover, contrary to emotional abuse, the current results did not demonstrate significant relationship between physical abuse and adolescent rejection sensitivity. This is in line with previous research (Gao et al., 2023), indicating childhood emotional abuse might have a significantly more powerful effects than physical abuse on the development of rejection sensitivity.

Finally, contrary to previous findings of insignificant sex differences in cycles of victimization (e.g., Shields & Cicchetti, 2001), the current study also found significant differences across sexes with regard to physical abuse. Specifically, the current results uncovered significant sex difference regarding the mediating pathway of aggression starting from physical abuse, which was only significant in adolescent boys. This may be due to that many previous studies investigating sex differences focused on direct associations between childhood abuse and peer victimization, but failed to take potential mechanisms into account. In other words, sex differences in the cycle of victimization may be reflected in the mechanisms that link certain childhood abuse and peer victimization, rather than the direct associations.

With regard to differences of the role that aggression played between sexes, the reason may be the fact that boys tend to experience significantly more physically violent episodes in family compared to girls in Chinese culture. As the old Chinese saying goes, “spare the rod, spoil the son”, physically-violent punishment is needed to rear a boy but not a girl in Chinese culture, which could provide more chances for the boys to learn from their caregivers an aggressive pattern of behaviors. Prior work has shown that the rate of physical abuse is higher in adolescent boys compared to girls in a Chinese context (Wan et al., 2021). While higher rates of physically violent episodes for boys could lead to interruptions in school functioning and induce more peer victimization (Koposov et al., 2021). Moreover, the social-learning theory of aggression posits that the experience of being physically abused by caregivers may result in the internalization of an aggressive behavioral pattern through the process of social learning, which could then be triggered in adolescent peer relationships, thus inducing victimization (Bandura, 1973). Alternatively, there is the possibility that boys traverse an externalizing pathway while adolescent girls may traverse an internalizing pathway. Previous research has highlighted that compared to girls, boys with a history of physical abuse are more likely to develop aggressive behaviors (Ford et al., 2010). While girls with a history of maltreatment are more likely to develop internalizing symptoms, such as self-injury (Serafini et al., 2017), and internalizing symptoms are more pronounced in girls when linking physical abuse with consequent maladaptation (Benedini & Fagan, 2018). Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of considering both specific mechanisms and types of childhood abuse targeted at certain sex when investigating how early victimization leads to later re-victimization.

The current findings have important implications for the conceptualization of and intervention for the cycle of victimization in adolescence. The current study provides additional evidence for how early experiences of victimization lead to the formation of a vicious cycle of re-victimization. Specifically, a pathway from rejection sensitivity to aggression might be crucial for the occurrence of re-victimization starting from childhood emotional abuse. And a pathway of aggression is crucial for both emotional and physical abuse. Additionally, these findings suggest that sex differences must be considered when examining the cycle of re-victimization. For example, adolescent boys may be particularly susceptible to physical abuse through an externalizing pathway such as aggression, with the consequences requiring additional attention. Moreover, the current findings also call for timely intervention targeted at the cycle of victimization. Given that both childhood abuse and peer victimization are major global health issue (Tolan et al., 2006), breaking the vicious cycle between them seems to be of significance for child and adolescent welfare. The current study provides important implications for future interventions targeted at breaking the connecting points such as maladaptive social-cognitive process and misbehaviors. For instance, adults like teacher or non-abusive caregivers should devote more attention and affection for children and adolescents suffered from childhood abuse to establish healthy attachment and reduce their hyper-sensitivity to rejection. Also, school-based behavioral adjustment programs targeted at problematic behaviors such as aggression might also be of help.

Despite these strengths, there are limitations worth considering for future investigations. First, the current study relied completely on self-report measures, which may be affected by false memory and misperception of the participants. Also, some of the measurements in the current study, particularly the abuse subscales of CTQ-SF, did not perform well in their reliability. Future research utilizing multi-informant and observational paradigms with more powerful ecological validity and stable reliability to assess levels of childhood abuse and peer victimization, as well as consideration of experimental and neurocognitive measurement of rejection sensitivity and aggression will provide further insights. Second, the current study utilized a three-wave dataset to investigate a developmental pathway, which may still have some confounds that were not addressed in the current study. For instance, the current study was unable to include aggression measured at T1 as covariate due to the research design in the very first place. Also, the time spans between each data collection were relatively short. Future research including at least four or more timepoints with longer time span to cover the developmental span from childhood to adolescence would help clear out many of the confounds. Third, the current study utilized data collected only from three middle schools in northern China, which could result in a generalizability issue. Future study utilizing a representative national sample will help obtain more general conclusion. Last, the current study only considered peer victimization, while experiencing childhood abuse could also result in elevated bullying behaviors, forming another cycle of violence (Yoon et al., 2021). Future studies should include both bullying and victimization as outcomes to identify how changes in social-cognitive processing influence subsequent behavioral enactments that ultimately result in the separation of perpetrator from the victim of peer violence. Also, future studies should include more maltreatment types, such as sexual abuse to probe for their specific associations in the cycle of victimization across sexes.

Conclusion

Despite prior evidence for the relationship between childhood victimization and later re-victimization in adolescence, little is known about the mechanisms of this vicious cycle. The current study addressed this issue by examining longitudinal associations between both childhood emotional and physical abuse and peer victimization in a school setting through the developmental pathway from rejection sensitivity to aggression. The results of the present study suggested that heightened rejection sensitivity and aggression are important mechanisms for perpetuating the cycle of victimization. Moreover, both adolescent boys and girls are susceptible to emotional abuse leading to peer victimization, and the effects of aggression from physical abuse were found only in adolescent boys. The present results provided important information for the conceptualization of the vicious cycle of victimization. Specifically, social-cognitive and behavioral consequences that result from early victimization must be taken into account when considering future re-victimization. Also, the present results can provide useful information for interventions for peer victimization, as interventions should consider social-cognitive and behavioral outcomes, as well as sex differences.

References

Allen, E. K., Desir, M. P., & Shenk, C. E. (2021). Child maltreatment and adolescent externalizing behavior: examining the indirect and cross-lagged pathways of prosocial peer activities. Child Abuse & Neglect, 111, 104796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104796.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231.

Arseneault, L., Bowes, L., & Shakoor, S. (2010). Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: 'much ado about nothing'? Psychological Medicine, 40(5), 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383.

Attar-Schwartz, S., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2015). Indirect and verbal victimization by peers among at-risk youth in residential care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.007.

Ayduk, O., Gyurak, A., & Luerssen, A. (2008). Individual differences in the rejection-aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: the case of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(3), 775–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.07.004.

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: a social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Banny, A. M., Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., Oshri, A., & Crick, N. R. (2013). Vulnerability to depression: a moderated mediation model of the roles of child maltreatment, peer victimization, and serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region genetic variation among children from low socioeconomic status backgrounds. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000047.

Benedini, K. M., & Fagan, A. A. (2018). From child maltreatment to adolescent substance use: different pathways for males and females. Feminist Criminology, 15(2), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085118810426.

Benedini, K. M., Fagan, A. A., & Gibson, C. L. (2016). The cycle of victimization: the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.003.

Berenson, K. R., & Andersen, S. M. (2006). Childhood physical and emotional abuse by a parent: transference effects in adult interpersonal relations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(11), 1509–1522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206291671.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0.

Bolger, K. E., & Patterson, C. J. (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72(2), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00296.

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79(5), 1185–1229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x.

Casper, D. M., & Card, N. A. (2017). Overt and relational victimization: a meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 88(2), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12621.

Chen, Q. Q., Chen, M. T., Zhu, Y. H., Chan, K. L., & Ip, P. (2018). Health correlates, addictive behaviors, and peer victimization among adolescents in China. World Journal of Pediatrics, 14(5), 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-018-0158-2.

Cicchetti, D. (2016). Socioemotional, personality, and biological development: Illustrations from a multilevel developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033259.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2009). The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: the coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(1–2), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01979.x.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2015). Child maltreatment. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, Vol. 3: Socioemotional Processes (pp. 515–563). New York: Wiley.

Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. L., & Maughan, A. (2000). An ecological-transactional model of child maltreatment. In A. J. Sameroff, M. Lewis, & S. M. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology, (2nd ed., pp. 689–722). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Cooley, J. L., Frazer, A. L., Fite, P. J., Brown, S., & DiPierro, M. (2017). Anxiety symptoms as a moderator of the reciprocal links between forms of aggression and peer victimization in middle childhood. Aggressive Behavior, 43(5), 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21703.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

Downey, G., Freitas, A. L., Michaelis, B., & Khouri, H. (1998). The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.545.

Downey, G., Lebolt, A., Rincón, C., & Freitas, A. L. (1998). Rejection sensitivity and children’s interpersonal difficulties. Child Development, 69(4), 1074–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06161.x.

Feldman, S., & Downey, G. (1994). Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 6(1), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400005976.

Fereidooni, F., Daniels, J. K., & Lommen, M. J. J. (2023). Childhood maltreatment and revictimization: a systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 15248380221150475. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221150475.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., & Hamby, S. (2012). Let’s prevent peer victimization, not just bullying. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(4), 271–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.12.001.

Ford, J. D., Fraleigh, L. A., & Connor, D. F. (2010). Child abuse and aggression among seriously emotionally disturbed children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903401104.

Fu, J., Luo, Z., & Yang, S. (2009). Revision of the reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire for middle school students. Journal of Capital Normal University(Social Sciences Edition), S4, 199–202.

Gao, S., Assink, M., Bi, C., & Chan, K. L. (2023). Child maltreatment as a risk factor for rejection sensitivity: a three-level meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 15248380231162979. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231162979.

Gao, S., Assink, M., Liu, T., Chan, K. L., & Ip, P. (2021). Associations between rejection sensitivity, aggression, and victimization: a meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(1), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019833005.

Gardner, M. J., Thomas, H. J., & Erskine, H. E. (2019). The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104082.

Gilman, R., Carter-Sowell, A., Dewall, C. N., Adams, R. E., & Carboni, I. (2013). Validation of the ostracism experience scale for adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030913.

Goemans, A., Viding, E., & McCrory, E. (2023). Child maltreatment, peer victimization, and mental health: neurocognitive perspectives on the cycle of victimization. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(2), 530–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211036393.

Guo, H., Chen, L., Ye, Z., Pan, J., & Lin, D. (2017). Characteristics of peer victimization and the bidirectional relationship between peer victimization and internalizing problems among rural-to-urban migrant children in China: a longitudinal study. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(3), 336–348. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00336.

Hamby, S., & Grych, J. (2013). The web of violence: exploring connections among different forms of interpersonal violence and abuse. Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5596-3.

Handley, E. D., Russotti, J., Rogosch, F. A., & Cicchetti, D. (2019). Developmental cascades from child maltreatment to negative friend and romantic interactions in emerging adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 31(5), 1649–1659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941900124X.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jobe, R. L. (2003). Emotional and physiological reactions to social rejection: the development and validation of the tendency to expect rejection scale and the relationship between rejection expectancy and responses to exclusion (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Kahya, Y. (2021). Intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration in a Turkish female sample: rejection sensitivity and hostility. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP4389–NP4412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518786499.

Kellij, S., Lodder, G. M. A., Giletta, M., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Guroglu, B., & Veenstra, R. (2023). Are there negative cycles of peer victimization and rejection sensitivity? Testing ri-CLPMs in two longitudinal samples of young adolescents. Developmental and Psychopathology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000123.

Koposov, R., Isaksson, J., Vermeiren, R., Schwab-Stone, M., Stickley, A., & Ruchkin, V. (2021). Community violence exposure and school functioning in youth: cross-country and gender perspectives. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 692402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.692402.

Koyanagi, A., Oh, H., Carvalho, A. F., Smith, L., Haro, J. M., Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., & DeVylder, J. E. (2019). Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 48 countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(9), 907–918.e904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.018.

Ladd, G. W. (2006). Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: an examination of four predictive models. Child Development, 77(4), 822–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x.

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: a meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1091–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001.

Lesnick, J., & Mendle, J. (2021). Rejection sensitivity and negative urgency: a proposed framework of intersecting risk for peer stress. Developmental Review, 62, 100998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100998.

Levy, S. R., Ayduk, O., & Downey, G. (2006). The role of rejection sensitivity in people’s relationships with significant others and valued social groups. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 250–289). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195130157.003.0010.

Li, T., Huang, Y., Jiang, M., Ma, S., & Ma, Y. (2023). Childhood psychological abuse and relational aggression among adolescents: a moderated chain mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1082516–1082516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1082516.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Li, X. (2004). A ralative study on rejection sensitivity (Unpublished master dissertation). Jiangxi Normal University, Jiangxi, China.

Li, X., Huebner, E. S., & Tian, L. (2021). Vicious cycle of emotional maltreatment and bullying perpetration/victimization among early adolescents: Depressive symptoms as a mediator. Social Science & Medicine, 291, 114483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114483.

London, B., Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Paltin, I. (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(3), 481–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x.

Maiolatesi, A. J., Clark, K. A., & Pachankis, J. E. (2022). Rejection sensitivity across sex, sexual orientation, and age: measurement invariance and latent mean differences. Psychological Assessment, 34(5), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001109.

McDowell, D. J., & Parke, R. D. (2009). Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: an empirical test of a tripartite model. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014305.

Miller, P., Baldwin, R., Coomber, K., Nixon, B., Taylor, N., Hayley, A., & de Andrade, D. (2022). The association of childhood physical abuse, masculinity, intoxication, trait aggression with victimization in nightlife districts. Child Abuse & Neglect, 123, 105396 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105396.

Mynard, H., & Jose, S. (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:2<169::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-A.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516.

Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., & Fisher, H. L. (2013). The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(10), 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.004.

Raine, A., Dodge, K., Loeber, R., Gatzke-Kopp, L., Reynolds, D. L. C., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Liu, J. (2006). The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: different correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior, 32(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20115.

Rogosch, F. A., Cicchetti, D., & Aber, J. L. (2009). The role of child maltreatment in early deviations in cognitive and affective processing abilities and later peer relationship problems. Development and Psychopathology, 7(4), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400006738.

Romero-Canyas, R., Downey, G., Berenson, K., Ayduk, O., & Kang, N. J. (2010). Rejection sensitivity and the rejection-hostility link in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 119–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00611.x.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192.

Schwarzer, N. H., Nolte, T., Fonagy, P., & Gingelmaier, S. (2021). Mentalizing mediates the association between emotional abuse in childhood and potential for aggression in non-clinical adults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 115, 105018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105018.

Serafini, G., Canepa, G., Adavastro, G., Nebbia, J., Belvederi Murri, M., Erbuto, D., Pocai, B., Fiorillo, A., Pompili, M., Flouri, E., & Amore, M. (2017). The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00149.

Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (2001). Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 30(3), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7.

Shin, T., Davison, M. L., & Long, J. D. (2017). Maximum likelihood versus multiple imputation for missing data in small longitudinal samples with nonnormality. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 426–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000094.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R. A., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2353.

Tolan, P., Gorman-Smith, D., & Henry, D. (2006). Family violence. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 557–583. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190110.

Wan, G., Li, L., & Gu, Y. (2021). A national study on child abuse and neglect in rural China: does gender matter. Journal of Family Violence, 36(8), 1069–1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00230-9.

Ward, M. K., & Meade, A. W. (2023). Dealing with careless responding in survey data: prevention, identication, and recommended best practices. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-040422-045007.

Widom, C. S. (2014). Longterm consequences of child maltreatment. In J. E. Korbin & R. D. Krugman (Eds.), Handbook of child maltreatment (pp. 225–247). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7208-3.

Xiao, D., Wang, T., Huang, Y., Wang, W., Zhao, M., Zhang, W. H., Guo, L., & Lu, C. (2020). Gender differences in the associations between types of childhood maltreatment and sleep disturbance among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.099.

Xiao, Y., Jiang, L., Yang, R., Ran, H., Wang, T., He, X., Xu, X., & Lu, J. (2021). Childhood maltreatment with school bullying behaviors in Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 941–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.022.

Xu, W., Wu, S., & Tang, W. (2022). Childhood emotional abuse, rejection sensitivity, and depression symptoms in young Chinese gay and bisexual men: testing a moderated mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.007.

Ybrandt, H., & Armelius, K. (2010). Peer aggression and mental health problems. School Psychology International, 31(2), 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034309352267.

Yoon, D., Shipe, S. L., Park, J., & Yoon, M. (2021). Bullying patterns and their associations with child maltreatment and adolescent psychosocial problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 129, 106178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106178.

Yoon, D., Yoon, S., Park, J., & Yoon, M. (2018). A pernicious cycle: finding the pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.024.

Zeichner, A., Parrott, D. J., & Frey, F. C. (2003). Gender differences in laboratory aggression under response choice conditions. Aggressive Behavior, 29(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10030.

Zhang, M. (2011). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of CTQ-SF. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 27(05), 669–670.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Nesdale, D., Webb, H. J., Khatibi, M., & Downey, G. (2016). A longitudinal rejection sensitivity model of depression and aggression: unique roles of anxiety, anger, blame, withdrawal and retribution. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(7), 1291–1307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0127-y.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the adolescents who participated in this research and the schools and research assistants who facilitated the data collection.

Authors’ Contributions

C.L. conceived of the study, performed the statistical analysis, participated in the research design, data curation, and interpretation of the data results, and drafted the manuscript; J.L. participated in the research design, data curation, and the interpretation of the data results, and commented on the manuscript; Y.G. participated in the research design, data curation, and commented on the manuscript; X.L. acquired the research funding, administrated and supervised the project, participated in the interpretation of the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900772).

Data Sharing Declaration

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for Publish

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Consent to Participate

Participants and their primary caregivers gave written informed consent for the assessment.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Human Participant Protection, Faculty of Psychology at Beijing Normal University. The procedures used in this study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Participants and their primary caregivers gave written informed consent for the assessment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, C., Liu, J., Gao, Y. et al. Developmental Pathway from Childhood Abuse to Adolescent Peer Victimization: The Role of Rejection Sensitivity and Aggression. J. Youth Adolescence 52, 2370–2383 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01833-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01833-3