Abstract

The development of peer relationships and of one’s identity are key developmental proficiencies during adolescence. Understanding how immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents are developing a sense of their national identity and the role that this plays in how they select their friends and are influenced by their friends is essential for developing a more comprehensive understanding of adolescent development in context. The current study used longitudinal social network analysis to examine the interplay of national identity development and friendship network dynamics among immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents in Greece (N = 1252; 46% female). All youth with higher national identity resolution (i.e., youth’s sense of clarity regarding their identity as a member of Greek society) in Grade 8 were more often nominated as a friend in Grade 9. During the transition from 8th to 9th grade, all youth became more similar to their nominated friends in terms of their Greek national identity exploration (i.e., degree to which they had engaged in activities to learn more about Greek society). During the transition from 7th to 8th grade, there was significant variability in peer selection on national identity exploration and resolution between immigrant and non-immigrant youth. Specifically, immigrant youth demonstrated selection effects consistent with notions of homophily, such that they were more likely to nominate peers in 8th grade whose levels of national identity exploration and resolution were similar to their own when in 7th grade. In contrast, non-immigrant youth preferred peers in 8th grade with low levels of national identity exploration (regardless of their own levels of exploration in 7th grade) and peers whose levels of national identity resolution in 8th grade were different from their own in 7th grade (e.g., non-immigrant youth who reported high national identity resolution in 7th grade were more likely to nominate peers who had low national identity resolution in 8th grade). There were no differences by immigrant status in peer influence, suggesting that the significant peer influence effects that emerged during the transition from 8th to 9th grade in which youth became more similar to their friends in national identity exploration may reflect a universal process. These results chart new directions in understanding contemporary youth development in context by showing that adolescents develop their national identity and friendships in tandem and that certain aspects of this process may vary by immigrant status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Identity formation is a key developmental task of the lifespan and is particularly salient during the developmental period of adolescence (Erikson 1968). Individuals’ identities are multifaceted and include many dimensions that coalesce to define the self. The dimensions of one’s identity that stem from one’s membership in particular social groups are referred to as social identities (Tajfel 1978). Social identities can include race, ethnicity, political affiliation, and gender among others. One social identity that is relevant to all youth, but relatively less studied is national identity. National identity captures individuals’ “subjective or internalized sense of belonging to the nation” (p. 65; Huddy and Khatib 2007). This sense of subjective or internalized belonging to a nation (i.e., national identity) is important for immigrant youth (i.e., at least one parent born outside of the host nation) because it signals their degree of connection to the host society (Fuligni and Tsai 2015). Furthermore, youth’s degree of connection to the nation is significant for all youth in terms of civic engagement, given positive associations with youth’s increased knowledge of political events (e.g., presidential election; conflicts abroad; Huddy and Khatib 2007) and greater voter turnout (Huddy and Khatib 2007; Schildkraut 2005). Indeed, some suggest that promoting a strong national identity among both immigrant and non-immigrant youth may be critical for fostering better intergroup relationships among young people by emphasizing a common ingroup identity among individuals who are members of groups that otherwise perceive themselves as distinct (Gaertner and Dovidio 2005).

Despite its relevance for positive youth development, there is limited research focused on understanding how adolescents develop their national identity and the role it plays in their formation of peer relationships; and even less is known about how this process varies by immigrant status. Similar to identity formation, the formation of peer relationships is a key developmental task of adolescence that has significant consequences for youth adjustment (Brown and Larson 2009). For immigrant youth, peer relations are both a developmental and an acculturative task, and positive peer relations with both intra- and interethnic peers have significant consequences for their adaptation (Motti-Stefanidi et al. 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018). Given the salience of peer relationships during this developmental period, peers may play a critical role in adolescents’ national identity development. Indeed, youth may look to their peers as role models as they consider their attachment to the nation and the extent to which they feel a sense of pride or belonging regarding this aspect of their identity. On the other hand, it is possible that adolescents’ feelings about their national identity guide their selection of friends, given the empirically robust finding in prior work demonstrating that individuals prefer friends who share the same sociodemographic, behavioral, and intrapersonal characteristics (i.e., principle of homophily; McPherson et al. 2001). Indeed, youth may seek to befriend peers with similar attitudes about national identity simply because it is easier to communicate and associate with those who share similar beliefs and experiences (McPherson et al. 2001). The current study was designed to explore these very questions: Does adolescents’ national identity development evolve as a function of their friends’ national identity development? Do adolescents simply choose to befriend those who are in a similar place with respect to their national identity development? Or do both processes operate? Additionally, this study explored whether the strength and direction of friendship selection and influence effects differed between immigrant and non-immigrant early adolescent youth, and during two grade transitions in middle school.

National Identity Development and Friendship Networks

Identity develops throughout the lifespan and is significantly shaped by the multiple contexts in which adolescents’ lives are embedded. One of the most proximal and salient contexts during this developmental period is school. Schools are a key developmental context for all youth, and the main context where immigrant youth are exposed to the host culture (Schachner et al. 2018). The current study focuses on one unique and highly important dimension of the school context: peers. During the school day, adolescents regularly interact with peers and are constantly receiving and providing feedback regarding their identities. It is within this context that adolescents continue to form their ideas about who they are and who they can become. Scholars have noted that schools and peers may be important influences in the development of one’s national identity (Schwartz et al. 2012); however, few studies have examined such potential mechanisms of influence.

Although not focused specifically on identity development, many prior studies have examined how youth form their friendships (friendship selection) and how their friendships influence them in return (peer socialization) in the context of national identification (e.g., Leszczensky 2013; Munniksma et al. 2015; Rutland et al. 2012). It is important to distinguish here between national identification and national identity developmental processes. Despite the extensive use of the term “national identity,” prior work has focused largely on national identification, that is, the extent to which individuals view themselves as members of the host nation. For example, national identification has been assessed with single-item questions such as “Do you feel Dutch?”—rated on a 5-point Likert scale (Leszczensky et al. 2016), or with multiple items that assess degree of attachment to the host society such as “Germany is dear to me; I feel like I am part of Germany”—rated on a 5-point Likert scale (Jugert et al. 2019; Leszczensky 2018), and private regard about the host society such as “I am content to belong to Germany” (Jugert et al. 2019). This operationalization provides information about content aspects of identity (Umaña‐Taylor et al. 2014), but tells little about an individual’s engagement in the process of coming to a particular identity (i.e., exploration). What it does capture, however, is the extent to which individuals consider their affiliation with the host country as part of their self-identification, and their degree of identification with (or connection to), the host society.

To the authors’ knowledge, all prior work examining friendship selection or influence effects has used these identity content-related operationalizations. Considering friendship selection, findings indicated that immigrant youth in Germany who had a stronger host country identification demonstrated a greater tendency to befriend native German youth (Leszczensky 2018). Similarly, with immigrant youth in the Netherlands, strength of host country identification was associated with immigrant youth befriending native youth and not befriending other immigrants (Leszczensky et al. 2016). A more complex pattern of friendship selection emerged once students’ host-country, dual-country, or heritage-country identification were considered such that ethnic majority youth from Germany preferred to befriend the following categories of friends in descending order: host country identifying, followed by dual-country, and finally heritage-country identifiers (Jugert et al. 2017). Similar patterns have emerged among ethnic majority youth in Greece (Asendorpf and Motti-Stefanidi 2017). Furthermore, recent research showed significant preference to befriend those who had similar levels of positive feelings toward their national identity in networks of middle school students in Germany (Jugert et al. 2019).

Regarding peer socialization processes (hereafter referred to as peer influence), Leszczensky et al. 2016 documented significant and positive peer influence on host country (the Netherlands) identification such that all youth became similar in their host country identification to the levels reported by their friends, and that this peer influence effect was significantly stronger for native youth relative to their immigrant counterparts. Moreover, Jugert et al. 2019 tested a proposition from social identity theory that peer influence on aspects of social identity would only operate in same-group relationships. Indeed, they found support that only same-ethnic—and not cross-ethnic friends—exerted peer influence on national identity attachment and private regard in friendship networks of young adolescents from Germany.

In contrast, the current study focuses on the process of national identity development. Specifically, the study is guided by an Eriksonian framework of identity formation (Erikson 1968; Marcia 1980, 1994), and considers the development of one’s national identity to include both an exploration of this identity domain (i.e., national identity exploration) and individuals’ sense of clarity regarding the meaning of this identity for their general sense of self (i.e., national identity resolution). This developmental and multifaceted conceptualization of national identity draws heavily from the literature on ethnic-racial identity development (Phinney 1993; Umaña‐Taylor et al. 2014), and has been applied in prior work with French adolescents (Sabatier 2008), South Asian immigrant youth in New Zealand (Stuart and Ward 2011), and U.S. American adolescents (Schwartz et al. 2012). With this more nuanced examination of national identity development, the current exploratory study examined friendship network dynamics to better understand how national identity development may shape adolescents’ friendship networks and vice versa. Consistent with prior work on national identification, the current study tested whether the patterns of associations among these constructs were more consistent with peer influence or friendship selection effects. A detailed conceptualization of the primary national identity development constructs of interest follows.

National Identity Exploration

National identity exploration captures adolescents’ activities focused on learning more about the country in which they reside, this can include attending activities that celebrate the nation or that deepen adolescents’ understanding of the history of the nation, as examples. From a developmental perspective, exploration of any identity domain is necessary for optimal identity formation, as it provides adolescents with an informed understanding of this aspect of their identity. Immigrant youth, in particular, need to explore feelings and attitudes regarding who they are in relation to the diverse and often conflicting values, attitudes and practices of their ethnic and national contexts (Motti-Stefanidi et al. 2012). By talking with others, participating in events, and engaging in activities that help them learn about who they are with respect to this identity domain, adolescents gather information that helps to shape the roots of adolescents’ identification with this particular social identity.

National Identity Resolution

In contrast to exploration, resolution captures the sense of clarity and confidence that one feels with respect to understanding the role that this particular identity domain plays in one’s life. Erikson’s (1968) theoretical notions regarding the importance of resolving one’s feelings regarding any given identity domain (e.g., religion, occupation) were operationalized by Marcia (1980) as identity commitment. With this operationalization, individuals who had made a strong commitment regarding a particular identity domain were believed to have resolved any questions or doubts they might have regarding that identity. Erikson’s (1968) theory of psychosocial development emphasized that the ideal progression of the identity formation process was one in which individuals engaged in a period of earnest exploration about any given identity domain, which then culminated in a strong sense of resolve regarding their commitment to that particular identity. Furthermore, individuals with a strong sense of clarity and resolve regarding their identity were expected to be better psychologically adjusted (Erikson 1968). Scholars suggest that the sense of self-assuredness and confidence that characterizes high identity resolution provides youth with psychological benefits (Phinney and Kohatsu 1997; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004) and specifically enables them to have more positive relationships with others (Erikson 1968; Kroger and Marcia 2011). Extending these ideas to the peer context, it is possible that individuals with a greater sense of confidence and self-assuredness are likely to be more attractive to peers as a potential friend.

The Current Study

The current study focused on adolescents’ national identity development and friendship network dynamics in Greece. European nations have experienced dramatic increases in their immigrant population, and Greece has been among the top receiving countries, especially because it is viewed by migrants as a geographic gateway to more affluent northern European countries (Motti-Stefanidi and Salmela-Aro 2018). Thus, the study of national identity development and potential variability by immigrant status is particularly salient in this cultural context. In addition to a focus on the cultural context of Greece, the current study focused on the developmental context of early to middle adolescence. Within the Greek educational system, the three middle school years of 7th, 8th, and 9th grade coincide with adolescents’ transition from early to middle adolescence, as youth tend to be 12 to 15 years of age in these grades. This transition from early to middle adolescence captures a significant period of development when peer influences are heightened (Laursen 2018). Furthermore, increases in social and cognitive maturity from early to middle adolescence play an important role in adolescents’ increased meaning-making regarding social identities (Umaña‐Taylor 2016). As such, the current study examined the associations of interest across the transition from 7th to 8th grade and from 8th to 9th grade.

Four specific goals guided the current study. Our first goal was to examine how two components of national identity development were associated with friendship selection processes over time, while statistically controlling for friendship selection based on immigrant status, gender, and network structural processes. Given that peer selection processes may take several forms (Snijders et al. 2010), a comprehensive array of processes through which national identity development might be related to peer selection were examined. Specifically, the current study investigated (a) whether youth were more likely to befriend peers who were more, versus less, similar to them in their Greek national identity, (b) whether levels of national identity development were associated with how many friends a focal adolescent nominated over time, and (c) whether levels of national identity development were associated with how many friendship nominations a focal adolescent received over time from his/her classmates. Findings in support of these three selection effects would indicate that adolescents who had engaged in more exploration regarding their national identity, and who had a clearer sense of what being Greek meant to them, would be (a) more likely to befriend peers who had similarly high levels of national identity exploration and resolution, (b) more gregarious and active in making friends, and (c) more popular as a potential friend. In the absence of past research documenting peer selection on the process components of national identity development (e.g., exploration and resolution) and an emerging body of evidence on the content dimensions of national identity development (e.g., national identity attachment; Jugert et al. 2019; Leszczensky et al. 2016; Leszczensky 2018), a comprehensive array of associations between national identity development and peer selection was explored. Importantly, these associations were examined while statistically controlling for how adolescent immigrant status contributed as an alternative predictor to the peer selection effects.

The second goal was to examine whether friends’ levels of each of the two national identity development components at Time 1 were associated with the respective dimensions of national identity development of the focal adolescent at Time 2, suggesting that peer influence on national identity development operates in friendship networks over time, again controlling for immigrant status. Given the focus on early adolescents transitioning into middle adolescence, and that peer influence is strong from early to middle adolescence (Steinberg and Monahan 2007), we expected that adolescents would become more similar to their nominated peers over the course of the study in terms of national identity development exploration and resolution—thus supporting peer influence effects. This is consistent with prior work demonstrating significant peer influence effects on ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution during early to middle adolescence with youth in the U.S. (Rivas‐Drake et al. 2017).

Our third and fourth goals were to explore whether the magnitude and direction of effects for both peer selection and influence varied as a function of adolescents’ immigrant status (i.e., immigrant vs. non-immigrant). Thus, Goal 3 focused on testing whether peer selection varied as a function of immigrant status, and Goal 4 focused on examining whether peer influence varied as a function of immigrant status. A large majority of immigrants have come to Greece from Albania and the former states of the Soviet Union, the latter particularly from the Greek diaspora. These are the two largest immigrant groups in the country. The immigrants of the diaspora are called Pontian-Greeks. They retained their Greek culture for many centuries, but never lived in Greece before migrating. Their language, which is a dialect rooted in Ancient Greek, is incomprehensible to speakers of modern Greek. Although the Greek government accorded them full citizenship status, native Greeks refer to Pontian-Greeks as the “Russians” and do not view them as “real Greeks”. In contrast, immigrants from Albania who at first entered the country as undocumented economic immigrants were considered guest workers. The remaining immigrants came mostly from other Eastern European countries such as Bulgaria, Romania, or former states of the Soviet Union such as Russia or Moldavia. Even though Pontian-Greek immigrants and immigrants from Albania and other countries differ in numerous ways, they also share a number of commonalities (Pavlopoulos and Motti-Stefanidi 2017). First, in all cases either they or their parents were not born in Greece; that is, all are immigrant groups facing the challenges of acculturation and the need to learn how to navigate between at least two cultures. Second, they all came from countries with unstable and poor economic situations, to a country that is relatively more affluent. As a result, their new situation is perceived as a vast improvement. Third, they all face similar economic and social difficulties in their adaptation to the same host country. Thus, Pontians, Albanians, and immigrants from other countries were pooled into one group and referred to as immigrants.

Longitudinal social network analysis (SNA) modeling (Snijders et al. 2010) was used for all analyses. An important advantage of using longitudinal SNA methods to study the dynamics linking national identity development to peer networks is that it enables estimation of the pathways of interest, while statistically controlling for important confounding processes such as preference to affiliate with peers who have the same immigrant status and are the same gender (McPherson et al. 2001) as well as network structural effects (Rivera et al. 2010). For instance, this approach enabled us to test the role of immigrant status (i.e., non-immigrant versus immigrant) on friendship selection, which helped us to understand whether non-immigrants were more likely to befriend other non-immigrants than immigrants and, similarly, whether immigrants were more likely to befriend other immigrant peers over non-immigrants. Failure to control for these confounding processes that also shape patterns of peer connections can result in an overestimation of the role of peer influence and selection on national identity development dynamics. Finally, given the focus on integrated school settings, where immigrant and non-immigrant youth go to school together and form same- and cross-group friendships, SNA methods enable a more holistic examination of how these relationships are selected, how they contribute to peer influence, and what role national identity development exploration and resolution and immigrant status play in these dynamics.

Method

Participants

Participants included 1252 adolescents (54% boys, Mage at Time 1 = 12.67, SD = 0.68) who were recruited from 14 middle schools in Athens, Greece. The ethnic and immigrant composition of the sample was as follows: 14.2% were first generation immigrants, 49.6% were second generation immigrants, and 36.2% were non-immigrant Greeks; 36.2% were Greek, 30.6% Albanian, 10.9% Pontian, 13.5% other, and 8.9% mixed ethnic background. Across the 14 schools, proportion of immigrants ranged between 39 and 85%. Students were assessed annually for 3 years beginning with their transition into middle school (i.e., Grade 7). From Time 1 (T1) to Time 2 (T2), 91% of the sample was retained; from T2 to Time 3 (T3) an additional 9% of the sample was lost, resulting in an overall attrition of 17%.

Procedure

This study is based on data from the Athena Studies of Resilient Adaptation project, conducted in Greece (Motti-Stefanidi and Asendorpf 2017). Adolescents, who were in the first year of middle school (12 years old) at T1, were assessed between 2013–2015 during the Greek economic crisis. Students were assessed annually after the first trimester of the school year for three school years in their classrooms during school time. Permission to study the students in these schools was granted by the Greek Ministry of Education; active parental consent and youth assent were also obtained.

Measures

Friendship nominations

Students were asked to nominate 3 best friends from their classroom. These nominations were used to construct friendship networks using directed binary tie definitions (i.e., a tie existed and was coded as 1 when student A nominated student B, and a tie did not exist and was coded as 0 when student A did not nominate student B).

National identity development

Students also completed an adapted version of Phinney and Ong’s (2007) revised Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM). The items in the current study were revised from Phinney and Ong’s 6-item MEIM to be in reference to the nation (i.e., Greece), rather than to an ethnic group. This adapted measure was used to assess both an individual’s exploration of their Greek national identity and their sense of clarity or resolution regarding the meaning that this identity domain has for their sense of self. Prior work has demonstrated that this measure has adequate test-retest reliability and internal validity with immigrant adolescents from Russia and Ukraine to Israel (Tartakovsky 2009). In the current study, exploration was assessed with three items (“I have spent time trying to find out more about Greece’s history, traditions, and customs,” “I have often done things that will help me understand my Greek identity better,” “I have spent time in conversations with others about being a member of Greek society”), and a mean score was computed (T1 α = 0.66, T2 α = 0.72, T3 α = 0.72). Resolution was assessed with one item (i.e., “I understand pretty well what it means to me to be a member of Greek society”). All items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from (1) totally disagree to (4) totally agree. Higher scores indicated higher levels of national identity exploration and resolution, respectively.

Demographics

Students’ immigrant status (1 = immigrant, 0 = non-immigrant) was assessed by asking students to report on the nativity of their mother and father. Youth were defined as immigrant if they had at least one foreign-born parent. Adolescent-reported gender was coded as 1 = female, 0 = male.

Analytical Approach

The goals of this study were to investigate the associations between two components of national identity development (i.e., exploration and resolution) and friendship network dynamics. Controlling for network selection on sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., gender, immigrant status) and network structural processes, analyses examined whether youth were more likely to select peers who are more versus less similar to them in the psychological dimensions of Greek national identity development (Goal 1). Next, analyses examined whether adolescents became more similar to their peers in terms of Greek national identity development (Goal 2). Finally, analyses examined whether immigrant status moderated the strength and magnitude of peer selection (Goal 3) and peer influence (Goal 4) on national identity development.

Model overview

The Stochastic Actor-Oriented Model (SAOM) consists of two submodels that are jointly estimated (for a detailed overview, see Snijders et al. 2010 and Veenstra et al. 2013). The network submodel tests the likelihood of friendship ties between adolescents based on various network selection processes. The behavior submodel captures effects related to changes in behavior over time.

Model effects

For the network specification, three types of effects on network selection for national identity development dimensions were considered. For illustration purposes the process for national identity development exploration is discussed, but note that the same effects were included for national identity development resolution. The national identity development exploration ego effect estimates the association between national identity development exploration levels and the number of friendship nominations that an adolescent tends to send out to his or her peers over time (i.e., network activity). A positive effect would indicate that adolescents with greater levels of national identity development exploration sent a higher number of friendship nominations over time. The national identity development exploration alter effect estimates the association between national identity development exploration levels and the number of friendship nominations that an adolescent tends to receive from his or her peers over time (i.e., network popularity). A positive effect would indicate that adolescents with greater levels of national identity development exploration received a higher number of friendship nominations over time suggesting that they were more popular as a friend. The national identity development exploration similarity estimates the tendency of adolescents to nominate friends who have similar levels of national identity development exploration. A positive national identity development exploration similarity means that adolescents were more likely to select peers with similar levels of national identity development exploration. Finally, to investigate whether the patterns of peer selection processes varied between immigrants and non-immigrants, a series of interactions were included: (a) between ego’s immigrant status and national identity development ego to examine when, with respect to national identity exploration and resolution, do immigrant youth nominate more friends compared to non-immigrant youth?; (b) between ego’s immigrant status and national identity development alter to examine when, with respect to national identity exploration and resolution, are immigrant youth nominated more often as a friends compared to non-immigrant youth?; and (c) between ego’s immigrant status and national identity development similarity to examine when, with respect to national identity exploration and resolution, are immigrant youth likely to choose friends similar to oneself compared to non-immigrant youth? The effect of similarity on gender and immigrant status on the likelihood of peer affiliation was also estimated. Finally, parameters for several network structural processes were included. Transitive triplets were used to model triadic closure processes by assessing whether having multiple friends in common increased the likelihood of tie formation. The indegree popularity squared effect estimated whether students who previously had more affiliations were more likely to develop additional affiliations over time. The network function also included effects for outdegree, which controlled for the number of ties.

For the behavior submodel, the peer influence effect on national identity development exploration and resolution was estimated using the average similarity effect. This effect predicts changes in national identity development exploration, for example, based upon how similar an adolescent’s national identity development exploration is to the average levels of national identity development exploration across all of his or her friends. A positive effect indicates that changes in national identity development exploration bring an adolescent closer to his or her friends’ average level of national identity development exploration. To examine whether immigrant youth differed from their non-immigrant counterparts in the main levels of the national identity development dimensions an effect to test for that (effect from immigranton national identity development exploration) was included; a positive valence of this effect indicates that immigrant youth had higher levels of national identity development exploration compared to non-immigrant youth. Finally, to examine whether the magnitude of peer influence differed by immigrant status, an interaction between average similarity on the national identity development dimension (i.e., exploration, resolution) and ego’s immigrant status was included. A positive valence of this effect indicates that immigrant youth were more likely to become similar to their friends’ average levels of the given national identity development dimension over time, compared to non-immigrant youth.

Modeling approach

SABM analyses were conducted using RSiena 4.0 (version 1.1-290; Ripley et al. 2018). Because of the interest in examining developmental differences across early adolescence, the three wave panel data enabled an examination of unique changes in networks and behaviors that occurred during the first transition from 7th to 8th grade and the second transition from 8th to 9th grade. Because SABM requires ordered categorical behavioral outcome variables (Ripley et al. 2018), national identity development values were rounded to the nearest integer, creating a measure that ranged from 1 to 4 (Rivas‐Drake et al. 2017). Furthermore, a structural zeros approach was used to combine the data from multiple classrooms from the same school given that a small number of students switched classrooms within their school throughout the study (i.e., structural zeros precluded cross-classroom ties within a school because students provided friendship nominations within classroom; Ripley et al. 2018). To gain sufficient power to detect peer influence on national identity development dimensions, a multi-group option (Ripley et al. 2018) was used to assemble one multi-group object across the 14 schools. Whereas the multi-group option has the advantage of boosting the power to detect peer influence effects, it assumes that all parameter estimates are the same across all schools. Thus, analyses tested whether this assumption was justified by examining school-related heterogeneity by including dummies into the models (i.e., Dummy 1 compared an effect for School 2 to that of School 1, Dummy 2 compared an effect for School 3 to that of School 2, etc.). Joint score-type tests for school-related heterogeneity of the final models were conducted to show that parameter estimates were homogeneous and discuss the school differences in parameters in the supplementary analyses (see Appendix).

In the current analyses, model convergence was determined as achieved when t statistics representing deviations between the observed and model-implied networks were less than 0.1 for individual model parameters and less than 0.25 across all of the model parameters (Ripley et al. 2018). Additionally, students nominated three best friends, so a maximum outdegree was specified to be equal to four because algorithm convergence cannot be achieved in a model where the maximum outdegree equals the actual value of all observed outdegrees (Ripley et al. 2018).

Due to poor model convergence, 2 out of 14 schools were dropped from the analysis of transition from 7th to 8th grades, whereas all 14 schools were included in the analysis of transition from 8th to 9th grades. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to compare the youth from the two schools that were dropped to the rest of the sample and documented that these youth did not differ from the analytical sample, with one exception. Independent sample t-tests revealed no difference between excluded and analytical sample students at T1 with regard to national identity development resolution (T1: t(1009) = −0.76, p = 0.45; T3: t(959) = −0.83, p = 0.41) and national identity development exploration (T1: t(1026) = −0.44, p = 0.66; T2: t(1012) = −1.20, p = 0.23; T3: t(961) = −1.38, p = 0.17). In addition, participants who were excluded from the analyses did not differ from those who were retained with regards to their immigrant status (χ2(1,1252) = 1.68, p = 0.20) and gender (χ2(1,1252) = 0.87, p = 0.35). There was a significant difference, however, in the scores for national identity development resolution at T2 for youth excluded from analyses (M = 3.37, SD = 0.79) compared to those who comprised the analytical sample (M = 3.07, SD = 0.97); T1: t(1005) = −3.55, p = 0.00).

Results

Descriptive Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 1 (see Appendix Supplement Table 1 for mean level comparisons among immigrant groups and non-immigrants). As expected, indices of national identity exploration were correlated with one another across waves, and indices of national identity resolution were correlated with one another across waves—suggesting stability across waves for each construct.

Network Selection: Do Adolescents Select Their Friends Based on National Identity Development Processes? (Goal 1)

The first goal was to examine how components of national identity development were associated with friendship selection processes over time, while statistically controlling for friend selection based on immigrant status and network structural effects. The results indicated that national identity development exploration and resolution were not significantly associated with the number of friends that adolescents nominated during their 7th to 8th grade and 8th to 9th grade transitions (see Table 2; Model 1, ego effects). However, the results revealed that immigrant youth nominated fewer friends over time during the transition from 7th to 8th grades (est. = −0.21, p < 0.05). Furthermore, findings indicated that adolescents with higher levels of national identity development resolution in the 8th grade were more often nominated by their classmates as a friend in 9th grade suggesting that they were more popular as a friend among their classmates (see Table 2, Model 1; alter effects; est. = 0.15, p < 0.05). National identity development exploration and immigrant status were not significantly associated with a tendency to receive more friendship nominations from peers. Finally, being similar to one’s friends on levels of national identity development exploration, resolution, and immigrant status was not significantly associated with an increased likelihood of friendship selection over time during either one of the transitions (see Table 2, Model 1; similarity effects).

Peer Influence: Do Friends Influence One Another’s National Identity Development? (Goal 2)

The second goal was to examine whether friends’ levels of national identity development at T1 were associated with the respective dimensions of national identity development of the focal adolescent at T2, suggesting that peer influence on national identity development operates among friends over time (see Table 2, Model 1; peer influence effects). The results revealed that during the transition from 8th to 9th grade, adolescents’ levels of national identity development exploration became similar to the average level of their friends’ levels of national identity development exploration (est. = 1.49, p < 0.05). A significant friend influence did not emerge during either developmental period for national identity development resolution.

Immigrant Status Differences in Network Selection: Does the Magnitude and Direction of Network Selection Based on National Identity Development Processes Differ Between Immigrant and Non-Immigrant Adolescents? (Goal 3)

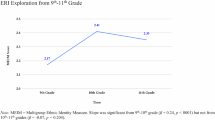

To better understand the role of immigrant status in the friend selection process (i.e., Goal 3), analyses tested whether the magnitude and direction of associations between national identity development components and friend selection processes were moderated by youth immigrant status. Thus, a separate Model 2 was conducted, where a series of interactions between ego’s immigrant status and friendship selection effects were tested, including ego, alter, and similarity effects for national identity development components. Results revealed a significant interaction between immigrant status ego effect and national identity development exploration alter effect (est. = 0.36, p < 0.05) during the transition from 7th to 8th grade suggesting that there were significant differences in these processes (see Table 2, Model 2; Alter NID Exploration × Ego Immigrant effect). To get a closer look at the differences by immigrant status, separate estimates were calculated for the alter effect of national identity development exploration for immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents. To follow up on this significant interaction, ego-alter selection tables (Ripley et al. 2018) that were constructed separately for immigrant and non-immigrant youth were used. This information is presented using simple slope graphs that depict the likelihood of befriending others as function of their national identity exploration (Fig. 1) and resolution (Fig. 2).

First, immigrant youth with high levels of national identity exploration in Grade 7 were more likely to nominate as friends those who had similarly high levels of national identity exploration in Grade 8; likewise, immigrant youth with low levels of national identity exploration in Grade 7 were more likely to nominate as friends those who had similarly low levels of national identity exploration in Grade 8 (Fig. 1a). In contrast, non-immigrant adolescents with both low and high levels of national identity exploration in Grade 7 preferred to befriend peers with low levels of national identity exploration in Grade 8 (Fig. 1b). Thus, immigrant youth preferred befriending others who had similar levels of national identity exploration development to them, whereas for non-immigrants, peers with low levels of national identity exploration development emerged as more popular as potential friends.

With respect to resolution, a significant interaction between immigrant status ego effect and similarity on national identity development resolution was detected during the 7th to 8th grade transition (est. = 2.09, p < 0.05), which suggested that there were significant differences in these processes by immigrant status (see Table 2, Model 2; Similarity NID Resolution x Ego Immigrant effect). Similar to findings for exploration, the follow-up analyses revealed that immigrant youth with high levels of national identity resolution in Grade 7 were more likely to nominate as friends those who had similarly high levels of national identity resolution in Grade 8, whereas immigrant youth with low levels of national identity resolution in Grade 7 were more likely to nominate as friends those who had similarly low levels of national identity resolution in Grade 8 (Fig. 2a). In contrast, non-immigrant youth preferred to nominate as friends those who had dissimilar levels of national identity resolution (Fig. 2b). Specifically, non-immigrant adolescents with low levels of national identity resolution in Grade 7 preferred to befriend others with high levels of national identity resolution in Grade 8 and non-immigrant adolescents with high levels of national identity resolution over time preferred to befriend others with low levels of national identity resolution. Thus, immigrant youth preferred homophily on national identity development resolution among their friends, whereas non-immigrant youth preferred heterophily, or dissimilarity, on national identity development resolution levels in their friends.

Immigrant Status Differences in Network Influence: Does the Magnitude and Direction of Peer Social Influence on National Identity Development Processes Differ Between Immigrant and Non-Immigrant Adolescents? (Goal 4)

Similar to above, the fourth goal was to examine whether the magnitude and direction of peer influence on national identity development varied between immigrant and non-immigrant youth. Model 2 tested this by including two interaction effects between ego’s immigrant status and average similarity effects used to model how friends’ levels of national identity development at Time 1 were associated with the ego’s national identity development levels of Time 2. These analyses revealed no significant differences in the strength and direction of friend influence effects on national identity development exploration and resolution between immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents (see Table 2, Model 2; Similarity NID Exploration × Ego Immigrant).

Finally, the above estimates were obtained in models that also accounted for confounding peer network selection processes that were documented across the two models for both transitions including (a) a significant and positive reciprocity parameter suggesting that friendship nominations were more likely to be reciprocated over time, (b) a significant positive transitive triplets parameter suggesting that a friend of a friend was more likely to become one’s friend over time, and (c) a significant and positive female similarity effect suggesting that students preferred to befriend others who were of a similar gender to them. These findings underscore that the friendship network selection was driven by universally documented processes of adolescent network formation.

Sensitivity Analyses to Examine Homogeneity Across Schools

To examine whether friendship network selection and friend influence effects operate equally across the different school contexts, Model 2 included dummy effects to compare them. Friendship network selection varied during the transition from 7th to 8th grade such that (a) gender homophily was significantly higher among friends in School 2 vs. School 4 (est. = 0.43, p < 0.05), suggesting that friendships in School 2 were more segregated by gender, and (b) immigrant homophily was significantly higher among friends in School 2 vs. School 4 (est. = 0.54, p < 0.05), suggesting that friendships in School 2 were more segregated by immigrant status. Findings also indicated that during the transition from 7th to 8th grade, there was a significantly lower magnitude of friend influence on national identity development resolution in students from School 9 vs. School 11 (est. = −2.44, p < 0.05).

Considering the transition from 8th to 9th grade, there was significantly lower gender homophily among friends in School 2 vs. School 4 (est. = −0.13, p < 0.05) suggesting that friendships in School 2 were less segregated by gender. In addition, during the transition from 8th to 9th grade, students from School 6 reported significantly lower levels of national identity development resolution than students from School 7 (est. = −0.79, p < 0.01) and students from School 12 reported significantly lower levels of national identity development resolution than students from School 13 (est. = −1.06, p < 0.01). Importantly, no significant school-related heterogeneity was observed in the significant friendship network selection and peer influence effects on national identity development exploration and resolution. Joint score-type tests for school heterogeneity revealed that, adjusted for the noted dummies, the joint significance tests for school heterogeneity at each site were not significant; this indicated that the parameter estimates were homogeneous across schools (from 7th to 8th grade: χ2(102) = 104.78, p = 0.41; from 8th to 9th grade: χ2(216) = 152.99, p = 0.99). Thus, having controlled for the above noted school differences, the remainder of the documented peer selection and influence effects were similar across schools.

Discussion

Identity development and the formation of peer relationships are each recognized as fundamental tasks of adolescence (Brown and Larson 2009; Kroger and Marcia 2011). One identity domain that is increasingly salient in the current sociohistorical context of increased migration (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018) and that has been linked with positive youth development is national identity (Huddy and Khatib 2007). Despite its links with adjustment, there is a limited understanding of how national identity develops, whether peers play a role in its development, and whether the formation of peer networks are informed by adolescents’ national identity. Increased understanding in these areas is vital to inform the development of youth programming and educational policy that can promote positive youth development. Accordingly, the current study used longitudinal social network analysis to examine the interplay of national identity development and friendship network dynamics among immigrant and non-immigrant youth across a 3-year period from early to middle adolescence. Evidence emerged for both selection and influence on national identity exploration and resolution, and findings for friend selection during the earlier developmental transition were qualified by adolescents’ immigrant status, whereas peer influence on national identity exploration during the later transition emerged for both immigrant and non-immigrant youth. For instance, during the transition from 8th to 9th grade, all youth (immigrant and non-immigrant alike) were more likely to nominate peers who had higher levels of national identity resolution (i.e., selection effects) and became more similar to their nominated peers (i.e., influence effects) in terms of their Greek national identity exploration. Furthermore, findings regarding friend selection effects during the 7th to 8th grade transition varied based on immigrant status. Specifically, immigrant youth selected friends who were more similar to them in the dimensions of national identity exploration and resolution. In contrast, non-immigrant youth preferred to befriend others with low levels of national identity exploration and those who had levels of national identity resolution that differed from their own. As discussed below, the results suggest important implications for understanding the interface of friendship and national identity developmental processes during early to middle adolescence among immigrant and non-immigrant youth in Greece.

Does Adolescents’ National Identity Development Inform Friendship Selection?

The findings revealed evidence of national identity resolution informing who received more incoming friendship nominations over time, describing friendship network popularity among youth. Across the transition from 8th to 9th grade, higher levels of national identity resolution drew more friendship nominations among all youth—immigrant and non-immigrant alike. Thus, as youth reported a greater sense of clarity regarding this aspect of their identity, they were more likely to be selected as friends by their peers. Drawing on Erikson’s (1968) theory of psychosocial development and subsequent empirical examination of these notions (Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke 2010; and see Kroger and Marcia 2011, for a review), individuals who are more resolved in their sense of self and have lower identity confusion are better prepared to engage in positive relationships with others given their greater sense of confidence and lack of uncertainty. Perhaps this greater sense of confidence in the self, in and of itself, is an important feature that attracts peers and results in more friendship nominations.

There was also evidence for a significant preference to befriend others with similar levels of national identity development, but these findings were qualified by adolescents’ immigrant status and only evident during the transition from 7th to 8th grade. Specifically, during the transition from 7th to 8th grade, immigrant adolescents were more frequently choosing to befriend youth with similar levels of national identity exploration and resolution. The opposite pattern emerged for non-immigrant youth, who preferred to befriend friends with (1) low levels of national identity exploration development, regardless of their own levels of national identity exploration, and (2) levels of national identity resolution that differed from their own levels of national identity resolution. Thus, whereas immigrant youth with high exploration preferred friends with similarly high exploration, non-immigrant youth with high national identity exploration preferred friends with low national identity exploration.

The findings for immigrant youth are consistent with expectations for peer homophily—youth who are engaging in high levels of exploration regarding this identity domain likely find comfort and ease in befriending and sustaining friendships with others who are engaged in similar activities. Similarly, national identity resolution captures the extent to which adolescents have a sense of clarity regarding their connection to Greek society—and the findings suggest that immigrant youth who are clear on this dimension of their identity are seeking friends with similar sentiments on this matter. In the same vein, immigrant youth who are unclear about the meaning of their identity with respect to the host society may seek friendships with those who are similarly unsure. Perhaps this was a salient dimension for friendship formation among immigrant youth because of their greater potential to be considered outsiders due to their immigrant status. To avoid rejection, immigrant youth may be more likely to seek friendships with peers who have similar perspectives on the role that Greek society plays in their lives.

Non-immigrant youth, in contrast, were not more likely to nominate friends with similar levels of national identity resolution. Perhaps national identity development is a less prominent factor in friendship formation when youth are not considered immigrants in the host society. These findings seemingly contrast with findings from European samples, where Leszczensky et al. (2016) found that native Dutch adolescents preferred to befriend immigrants with stronger rather than weaker national identification levels and that immigrants did not prefer to befriend others with stronger levels of national identification. Furthermore, Jugert et al. (2017) found that native German youth preferred to befriend immigrant peers with strong host-country identification, followed by dual-country and heritage-country identification. It is noteworthy that the Leszcezensky et al. and Jugert et al. studies aimed to examine contributions of intergroup friendships to selection on national identification, whereas the goal here was to examine differences by immigrant status in terms of how strongly national identity developmental processes shaped their selection of friends. Supplemental analyses (see Appendix Table 2) revealed that comparable three-way interactions to explore how national identity development contributed to intergroup friendship selection were not statistically significant, potentially due to the present analyses being underpowered to detect these effects. Whereas more research is needed to illuminate the role of intergroup friendships, it is possible that the differences in these studies are related to conceptual differences in identification rather than identity developmental processes. Put differently, whereas the Leszczensky et al. study highlights the content of that identification (i.e., degree to which adolescents feel Dutch), the current investigation focuses on the developmental processes that inform this identification. In this way, the current investigation adds an important developmental dimension to the study of how national identity contributes to friendship selection.

In terms of the developmental timing, it is possible that this selection effect only emerged from 7th to 8th grade because by the transition from 8th to 9th grade, immigrant youth had become more acquainted with their classmates and did not seek the safety of homophily with peers on this dimension that could potentially label them as an outsider. Perhaps national identity development is particularly important for the friendship formation of immigrant youth when they enter a new setting (which is the case in Greek middle schools in which 7th grade is the first year the students come together) because there is more uncertainty regarding whether they will be accepted by peers due to their immigrant status. By the time they have settled into their schools a year later (i.e., 8th grade in the Greek school system), this may be less relevant to friendship selection. In fact, Motti-Stefanidi et al. (2012) found that peer acceptance of immigrant students increased over time in classrooms in which there were few immigrants; thus, immigrant youth may become more aware of being more accepted by their peer group and in the process also modify how they are selecting their friends.

Do Friends Influence One Another’s National Identity Development?

Given the focus on early adolescents transitioning to middle adolescence, a developmental period in which youth are more likely to be influenced by peers and make choices regarding their identities based on others’ perspectives, it was hypothesized that adolescents would influence one another’s national identity development over time. Specifically, over time, friends were expected to become more similar to one another in terms of how much they were exploring their Greek national identity and the extent to which they had a sense of clarity regarding the meaning of their Greek national identity for their general sense of self. Partial support for this hypothesis emerged. For instance, adolescents became more similar to their nominated peers from Grade 8 to Grade 9 in terms of how much they were exploring their Greek national identity. Findings did not, however, suggest peer influence effects for national identity exploration from 7th to 8th grade, nor for national identity resolution across the 3 years of the study.

It is possible that changes in exploration from 8th to 9th grade are relatively more variable and, therefore, it is easier to detect influence. In Greek schools, Grade 7 reflects an important transition year in which youth are together in new classrooms for the first time; the new context may prompt greater national identity exploration among all youth as they are attempting to understand who they are and how they fit in to this new environment. This may make it difficult to detect any influence effects on national identity exploration by limiting variability because all youth are increasingly exploring. Yet, by the time students are transitioning from 8th to 9th grade, there may be a greater comfort zone and less national identity exploration among some youth relative to others—making it easier to detect peer influence effects.

Interestingly, there was no support for peer influence on national identity resolution. One possibility might be that peer influence on national identity resolution is not evidenced during middle school because students have not yet known each other for an extended period. Perhaps youth need to get to know one another on a more personal level and develop greater intimacy, perhaps even getting to know one another’s families, before they start emulating one another’s levels of clarity about psychological sense of identity. These ideas are speculative, however, and future research would benefit from a more comprehensive examination of adolescents’ awareness of their peers’ levels of identity resolution in this domain.

Taken together, findings from the current study suggest two important implications for youth development. First, identity formation and peer relationships are key developmental competencies during adolescence and these findings suggest that these competencies not only interrelate as adolescents progress from 7th through 9th grade but that this interrelation develops over time. Whereas earlier in adolescence (i.e., the transition from 7th to 8th grade) immigration status moderated adolescents’ friendship selection (with immigrant youth selecting friends similar to themselves and non-immigrant youth befriending those with low levels of national identity exploration and who differed from them in terms of national identity resolution), during the transition from 8th to 9th grade, adolescents both selected friends who were more resolved in their national identity and influenced each other in terms of their Greek national identity exploration. Second, the fact that the friend influence in national identity exploration from 8th to 9th grades was evident among all students—immigrants and non-immigrants—suggests that this may be a universal aspect of the developmental progression of national identity exploration. Although replication is necessary, these findings suggest that friends become increasingly similar to one another over time with respect to their exploration of Greek culture. These results underscore the socializing role of friends and peers whereby joint participation in interactions, conversations, and activities with friends promotes both individual-level identity exploration and peer influences among friends on the degree to which one is exploring what it means to have a particular national identity. Developmental and social identity theories have long theorized that identity development occurs through a constellation of such processes (Erikson 1968; Tajfel and Turner 1979), contemporary scholars have echoed these notions (e.g., Crocetti et al. 2018), and findings from the current study provide initial evidence for these processes with respect to national identity exploration dynamics.

Finally, the results indicated that there was no difference in the strength of peer influence on national identity exploration and resolution components between immigrant and non-immigrant youth. Although replication is necessary, the preliminary findings that emerged in the current study suggest that the peer influence effect that was identified for national identity exploration during the 8th to 9th grade transition could potentially reflect a universal pattern for this developmental process.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Despite this study’s strengths, there are important limitations to consider, which also provide opportunities for future research. First, given the limited number of friendship nominations (i.e., students were asked to name only three best friends), the friendship network data may have underrepresented the structure of in-school social relationships because adolescents did not have an option to list all their friends, including more distant acquaintances, from their schools. Nevertheless, because best friendships represent a relational context that is intimate and high-quality (Bagwell and Bukowski 2018), best friendships are likely to be a particularly fertile context for both friends’ exploration and resolution of their social identities, including national identity. Additionally, because this study focused on friends from the school context, the results are only generalizable to in-school best friends and future studies should examine the role of friends from a neighborhood and other out-of-school settings for national identity development. Furthermore, given the recent advances in conceptualizing how social settings may shape ethnic-racial identity development processes (Syed et al. 2018), future studies also should examine how variability in school-level factors (e.g., immigrant and ethnic-racial composition or diversity) may shape friendship network and identity developmental processes (e.g., Smith et al. 2016).

Another methodological limitation pertains to the use of a single-item measure of resolution. In an effort to isolate the resolution dimension of the identity development process, assessment of this construct was limited to a single item derived from an existing measure. Given that measures comprised of multiple items demonstrate relatively stronger psychometric properties, it will be ideal for future studies with more extensive assessments to examine the associations of interest. In addition, the study design was limited to yearly assessments during a 3-year period and did not enable an examination of the transition from middle to late adolescence. It is possible that the role of friendships on national identity formation (and vice versa) varies as a function of developmental period. As youth transition into late adolescence, there may be a clearer pattern toward friendship selection whereby adolescents are not being socialized by peers but rather are choosing to be friends with those whose views with which they agree. This may be particularly the case for a construct such as a national identity, which can be closely tied to political affiliations as youth consider their civic role in the broader society, and is more likely to emerge during late adolescence rather than earlier in development. Thus, future work would benefit from examining a broader developmental swath, which would clarify the developmental progression of national identity formation and the role of friendships across early to late adolescence. Moreover, future research may include idiographic approaches that focus on within-person fluctuations (Zeiders et al. 2015) in national identity exploration and resolution, and draw on more frequent assessments to better understand how time-varying changes in national identity formation shape adolescents’ friendship networks both within and across academic years.

Conclusion

Immigration is a global phenomenon that is affecting more and more countries each year. The current study focused on the Greek context, but findings may apply broadly to other nations with a non-negligible population of immigrant youth. In fact, the significant changes that have taken place in the European Union in the past two decades with respect to the upsurge of immigrants have made issues of immigrant youth adaptation a key concern, particularly because the adaptation of immigrant youth is a key indicator of how well immigrants are being integrated into a society (Motti-Stefanidi and Masten 2017). Given that peer relationships (Brown and Larson 2009) and identity formation (Erikson 1968; Kroger 2007) are key developmental competencies during adolescence, understanding how adolescents are developing their Greek national identity and their friendships in tandem is essential for developing a more comprehensive understanding of adolescent development in context. The findings contribute to this important body of research by highlighting that features of the national identity development process inform adolescents’ selection into friendships. Adolescents who are more engaged in the developmental process of national identity resolution in 8th grade are more popular as potential friends in 9th grade than those who are less engaged in this process—a finding that underscores the universally promotive nature of adolescents’ engagement in the identity development process. To be clear, the aspect of national identity development that was examined in the current study and that is posited to represent a developmental competency for immigrant and non-immigrant youth alike is the process by which adolescents explore, self-reflect, and develop a sense of clarity regarding the meaning that this identity domain has for their general sense of self. Gaining a sense of clarity regarding this identity domain is theorized to contribute positively to adolescents’ global identity development and, in turn, their adjustment (Umaña‐Taylor 2018). The current study did not examine the strength (i.e., content) of adolescents’ national identities and an important direction for future research will be to simultaneously examine the process and content dimensions of national identity and explore the potentially different implications each has for adolescents’ friendships, paying particular attention to how this may vary according to youth’s immigrant status.

References

Asendorpf, J. B., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2017). A longitudinal study of immigrants’ peer acceptance and rejection: immigrant status, immigrant composition of the classroom, and acculturation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000155.

Bagwell, C. L., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Friendship in childhood and adolescence: features, effects, and processes. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. 3rd ed. (pp. 371–390). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beyers, W., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2010). Does identity precede intimacy? Testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558410361370.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescents. In R. M. L. Steinberg (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, contextual influences on adolescent development (Vol. 2, 3rd ed., pp. 74–103). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Crocetti, E., Prati, F., & Rubini, M. (2018). The interplay of personal and social identity. European Psychologist, 23, 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000336.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton.

Fuligni, A. J., & Tsai, K. M. (2015). Developmental flexibility in the age of globalization: autonomy and identity development among immigrant adolescents. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015111.

Gaertner, S.L., & Dovidio, J.F. (2005). Understanding and addressing contemporary racism: from aversive racism to the common ingroup identity model. Journal of Social Issues, 61(3), 615–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00424.x.

Huddy, L., & Khatib, N. (2007). American patriotism, national identity, and political involvement. American Journal of Political Science, 51, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00237.x.

Jugert, P., Leszczensky, L., & Pink, S. (2017). The effects of ethnic minority adolescents’ ethnic self‐identification on friendship selection. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28, 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12337.

Jugert, P., Leszczensky, L., & Pink, S. (2019). Differential influence of same‐and cross‐ethnic friends on ethnic‐racial identity development in early adolescence. Child Development. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13240.

Kroger, J. (2007). Identity development: adolescence through adulthood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J.E. (2011). The identity statuses: origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, V. Vignoles (Eds), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31–53). New York, NY: Springer.

Laursen, B. (2018). Peer influence. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen & K. H. Rubin (Eds), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 447–469). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Leszczensky, L. (2013). Do national identification and interethnic friendships affect one another? A longitudinal test with adolescents of Turkish origin in Germany. Social Science Research, 42(3), 775–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.019.

Leszczensky, L. (2018). Young immigrants’ host country identification and their friendships with natives: does relative group size matter? Social Science Research, 70, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.10.012.

Leszczensky, L., Stark, T. H., Flache, A., & Munniksma, A. (2016). Disentangling the relation between young immigrants’ host country identification and their friendships with natives. Social Networks, 44, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.08.001.

Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). New York, NY: Wiley.

Marcia, J. E. (1994). The empirical study of ego identity. In H. A. Bosma, T. L. G. Graafsma, H. D. Grotevant & D. J. de Levita (Eds), Identity and development: an interdisciplinary approach (pp. 67–80). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2017). Adaptation during a great economic recession: a cohort study of Greek and immigrant youth. Child Development, 88, 1139–1155. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12878.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Asendorpf, J. B., & Masten, A. S. (2012). The adaptation and well-being of adolescent immigrants in Greek schools: a multilevel, longitudinal study of risks and resources. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000090.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Berry, J., Chryssochoou, X., Sam, D. L., & Phinney, J. (2012). Positive immigrant youth adaptation in context: developmental, acculturation, and social-psychological perspectives. In A. S. Masten, K. Liebkind & D. J. Hernandez (Eds), The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence. Realizing the potential of immigrant youth (pp. 117–158). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., & Masten, A. S. (2017). A resilience perspective on immigrant youth adaptation and development. In N. J. Cabrera & B. Leyendecker (Eds), Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (pp. 19–34). New York, NY, US: Springer Science + Business Media.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Challenges and resources for immigrant youth positive adaptation: what does scientific evidence show us? European Psychologist, 23, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000315.

Munniksma, A., Verkuyten, M., Flache, A., Stark, T. H., & Veenstra, R. (2015). Friendships and outgroup attitudes among ethnic minority youth: the mediating role of ethnic and host society identification. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 44, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.12.002.

Pavlopoulos, V., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2017). Intercultural relations in Greece. In J. W. Berry (Ed.), Mutual intercultural relations (pp. 187–209). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Phinney, J. S., & Kohatsu, E. L. (1997). Ethnic and racial identity development and mental health. In J. Schulenberg, J. L. Maggs & K. Hurrelmann (Eds), Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence (pp. 420–443). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271.

Phinney, J. S. (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In M. B. Bernal & G. P. Knight (Eds), Ethnic identity: formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities (pp. 61–79). New York, NY: State University of New York.

Ripley, R. M, Snijders, T. A. B, Boda, Z, Voros, A., & Preciado, P. 2018). Manual for RSiena. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford, Department of Statistics; Nuffield College. http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/∼snijders/siena/RSiena_Manual.pdf.

Rivas‐Drake, D., Umaña‐Taylor, A. J., Schaefer, D. R., & Medina, M. (2017). Ethnic‐racial identity and friendships in early adolescence. Child Development, 88(3), 710–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12790.

Rivera, M. T., Soderstrom, S. B., & Uzzi, B. (2010). Dynamics of dyads in social networks: assortative, relational, and proximity mechanisms. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134743.

Rutland, A., Cameron, L., Jugert, P., Nigbur, D., Brown, R., Watters, C., & Le Touze, D. (2012). Group identity and peer relations: a longitudinal study of group identity, perceived peer acceptance, and friendships amongst ethnic minority English children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 30(2), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02040.x.

Sabatier, C. (2008). Ethnic and national identity among second-generation immigrant adolescents in France: the role of social context and family. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.001.

Schachner, M. K., Juang, L., Moffitt, U., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2018). Schools as acculturative and developmental contexts for youth of immigrant and refugee background. European Psychologist, 23, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000312.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). Press one for English: language policy, public opinion, and American identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schwartz, S. J., Park, I. J., Huynh, Q. L., Zamboanga, B. L., Umana-Taylor, A. J., Lee, R. M., & Weisskirch, R. S. (2012). The American identity measure: development and validation across ethnic group and immigrant generation. Identity, 12(2), 93–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2012.668730.

Smith, S., Van Tubergen, F., Maas, I., & McFarland, D. A. (2016). Ethnic composition and friendship segregation: differential effects for adolescent natives and immigrants. American Journal of Sociology, 121, 1223–1272. https://doi.org/10.1086/684032.

Snijders, T. A., Van de Bunt, G. G., & Steglich, C. E. (2010). Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Social Networks, 32, 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2009.02.004.

Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531.

Stuart, J., & Ward, C. (2011). A question of balance: exploring the acculturation, integration and adaptation of Muslim immigrant youth. Psychosocial Intervention, 20(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2011v20n3a3.

Suárez-Orozco, C., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Marks, A., & Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant origin children and youth. The American Psychologist, 73(6), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000265.

Syed, M., Juang, L. P., & Svensson, Y. (2018). Toward a new understanding of ethnic‐racial settings for ethnic‐racial identity development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28, 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12387.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 61–76). London: Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds), The social psychology of intergroup relations, (pp. 33–48). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.