Abstract

Very few studies of peer victimization have been conducted in low-resource countries, where cultural and contextual differences are likely to influence the dynamics of these experiences in ways that may reduce the generalizability of findings of the larger body of literature. Most studies in these settings are also subject to multiple design limitations that restrict our ability to understand the dynamics of peer victimization experiences. Person-centered approaches such as latent class analysis are an improvement on more traditional modeling approaches as they allow exploration of patterns of victimization experiences. The goal of the current study was to examine associations between patterns of peer victimization in adolescence and both concurrent and longitudinal psychosocial adjustment. Data were included for 3536 youth (49.6% female) in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam to examine associations between adolescent peer victimization and indicators of poor psychosocial adjustment. Previously derived latent classes of peer victimization based on youth self-report of past-year exposure to nine forms of peer victimization at age 15 were used to predict self-reported emotional difficulties, self-rated health, and subjective wellbeing at ages 15 and 19 while controlling for sex. The findings show that at age 15, victimization was associated with higher emotional difficulties in all settings, lower subjective wellbeing in all except Peru, and lower self-rated health in Vietnam. At follow-up, all associations had attenuated and were largely non-significant. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these results. These findings illustrate the multifinality of outcomes of peer victimization, suggesting social and developmental influences for potential pathways of resilience that hold promise for informing interventions and supports in both low and high resource settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peer victimization, including bullying, is among the most common forms of aggression experienced by school-aged children (Masiello 2014). Most research examining this phenomenon has been concentrated in high income countries in Europe and North America, where peer victimization has been associated with negative psychosocial adjustment outcomes (e.g., emotional, health, school, and social problems, somatic complaints and suicidal ideation) both concurrently (Hawker and Boulton 2000) and over time (Wolke and Lereya 2015). However, a closer review of this literature suggests that these associations—particularly the longitudinal findings— are not universal; in fact, there is much more to be understood about variation in these effects, including the dynamic nature of peer victimization and the likelihood of poor psychosocial adjustment in emerging adulthood. Examining multifinality in outcomes of youth peer victimization, McDougall and Vaillancourt (2015) highlighted literature suggesting that concurrent mental health problems, aggressive tendencies, and less social support all present risk for more negative outcomes, but that more research is needed to understand the impact of other victimization factors such as personal characteristics, developmental timing, forms of victimization, and reciprocal relationships between poor psychosocial adjustment and victimization exposure. Research also suggests that factors such as the gender dynamics (Carbone-Lopez et al. 2010) and social context in which the victimization occurs (Bellmore et al. 2004) all influence the potential deleterious effects of peer victimization, highlighting the importance of understanding these various features when examining the potential impact of peer victimization.

Peer Victimization in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries

The bulk of research on peer victimization has been carried out in the U.S., Europe, and other Western countries, leaving a particular dearth of knowledge about the nature and potential impact of peer victimization experiences in other culturally and contextually diverse regions of the world. Although evidence suggests that roughly one in three youth is a victim of peer aggression worldwide (Due and Holstein 2008), much of the research from low-income and middle-income countries has been based on data from a single question about recent bullying victimization on the Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS; https://www.cdc.gov/GSHS/). These data have shown concurrent associations between bullying victimization and multiple indicators of poor psychosocial adjustment in countries where the GSHS has been conducted. For example, a study of 19 low-resource countries across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas showed remarkably consistent cross-sectional associations between bullying exposure and sadness, loneliness, insomnia, and suicidal ideation (Fleming and Jacobsen 2010). Likewise, GSHS data from eight countries in Africa showed similarly consistent and graded associations between exposure to bullying and poor mental health, suicidal ideation, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Brown et al. 2008). These findings suggest similar negative impacts of peer victimization in these settings as that have been observed in high resource settings (Hawker and Boulton 2000). However, because the results are based on a single question regarding bullying in a cross-sectional survey rather than multiple types of bullying and peer victimization experiences, researchers are unable to examine differences in the dynamics of these experiences across contexts, as well as the potential that different forms or patterns of peer victimization may have different impacts on psychosocial adjustment.

There is reason to think that the relative impact of forms of victimization may vary by social context; for example, previous research in Peru showed that whereas relational and physical victimization were associated with health risk behaviors, the same association did not hold for property victimization (Crookston et al. 2014). Similarly, across multiple Latin American countries, those countries with a higher prevalence of bullying showed lower impact of bullying victimization on academic achievement (Roman and Murillo 2011). As peer victimization occurs within a social context, how these acts are viewed and the relative harm associated appears to vary by culture and context (Smith et al. 2002). Moreover, the design of the GSHS precludes examination of these associations longitudinally. As a result, additional research is needed, particularly in regions where peer victimization research has been historically understudied, as the extent to which these experiences impact longitudinal psychosocial adjustment is unclear.

The current study used data from Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Similar to other low-income and middle-income countries, research examining peer victimization in these settings is scarce, largely cross-sectional, and limited in its generalizability, but does suggest that peer victimization is concurrently associated with poor psychosocial adjustment. For example, in Ethiopia, students have reported feeling sick due to being bullied (Aberra 2013). In India, bullying has also been associated with both emotional problems and physical complaints in separate studies (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011). Certain types of peer victimization have been associated with concurrent health risk behaviors (Crookston et al. 2014) and mental health problems (Lister et al. 2015a) in Peru. Bullying has also been identified as a risk factor for suicidal ideation among boys in Vietnam (Phuong et al. 2013). However, with a few exceptions (e.g., Crookston et al. 2014), this research has not typically looked beyond a general indicator of peer victimization exposure to understand how the exposure dynamics may differently contribute to psychosocial outcomes, and the limited longitudinal research highlights variation in when and how peer victimization has a lasting impact (Lister et al. 2015a). Furthermore, these studies typically focused on early adolescence with no follow-up in late adolescence. Using the same datasets as those used in the present study, Pells and colleagues (Pells et al. 2016) did explore the association between particular forms of peer victimization and longitudinal outcomes, and found general trends of slightly negative, yet largely non-significant associations between each of nine forms of peer victimization and later self-efficacy, self-esteem, parent relations, and peer relations. Although that approach was informative, by looking at each exposure independently the analysis did not account for the high correlations between multiple forms of exposure, which may have attenuated their ability to detect this association.

Person-Centered Research Approaches

Regarding form of victimization, researchers often use behavior-based assessment approaches that gather more information about the types of victimization experienced, which allows for exploration of unique impacts associated with different forms or subtypes of victimization (Sawyer et al. 2008). This approach, however, has limitations in terms of utility for meaningful classification of groups of youth, particularly given the inability to account for high correlations between different forms of victimization (Nylund et al. 2007). To address this limitation, person-centered approaches such as latent class analysis (LCA) are increasingly being used to examine meaningful heterogeneity within populations for developmental research (Lanza and Cooper 2016; Lanza and Rhoades 2013; Rosato and Baer 2012). This approach is consistent with a call by McDougall and Vaillancourt (2015) to move beyond traditional variable-oriented approaches to explore factors and pathways leading to different outcomes. Based on the assumption that an underlying latent variable accounts for responses to a set of observed, discrete indicators, LCA examines patterns of responses and classifies individuals into subgroups (latent classes) of individuals (Lanza and Cooper 2016). This allows for the use of LCA to examine groups of youth with similar patterns of victimization experiences that are explained by latent class membership (McCutcheon 1987).

Researchers using LCA to study peer victimization have highlighted its flexibility in allowing class membership to be determined by a combination of severity and form characteristics, therefore accounting for experiencing multiple types of victimizing behavior and addressing challenges inherent in using either typical scale scores or researcher-driven sub-type classifications (Bradshaw et al. 2013; Nylund et al. 2007). Findings using an LCA approach also suggest that latent classes have value added over typical scale scores in predicting subsequent psychosocial problems and identifying unique associations between certain patterns of victimization and psychosocial problems (Bradshaw et al. 2013; Nylund et al. 2007). Together, these studies demonstrate the heterogeneity in experiences of peer victimization and illustrate the value of studying how these behaviors are experienced within groups of individuals for improving identification and subsequent interventions.

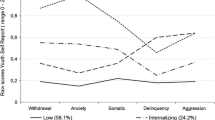

Leveraging an LCA approach, the current authors previously empirically derived classes of victimization among samples of 15-year old youth in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam and explored correlates of class membership (Nguyen et al. 2016). That prior study found that across all four country samples, victimized youth were likely to experience multiple forms of victimizing behavior rather than one particular form of victimization, but that there were potentially meaningful differences across settings regarding what these patterns of victimization looked like and which young people were at highest risk of exposure (Nguyen et al. 2016). Specifically, class enumeration resulted in a 3-class model in Ethiopia and Vietnam, a 4-class model in India, and a 2-class model in Peru. Although the classes were generally characterized by severity and were so named (not victimized, sometimes victimized, highly victimized), there were also unique form characteristics in some cases. In India, rather than a single sometimes victimized class, two classes with distinct forms of victimization were identified: a direct class characterized by physical and verbal victimization, and an indirect class characterized by relational and property victimization. In Vietnam, the sometimes victimized class represented a blend of relational victimization and also intimidation, with very little physical victimization. Additionally, in Peru only sometimes and highly victimized classes were identified; in this case it is likely that with higher prevalence of victimization exposure paired with a smaller sample in Peru, the absence of a not victimized class reflects an issue of statistical power rather than a fundamental true lack of non-victimized Peruvian youth. While also reporting important differences in demographic predictors of class membership, this prior study illustrates how culture and context are likely to result in meaningful differences in peer victimization experiences (Nguyen et al. 2016).

The Current Study

Since publication of the previous study, follow-up data using these same study samples has been publicly archived, presenting the opportunity to extend this earlier cross-sectional research by longitudinally examining associations between these victimization classes and poor psychosocial adjustment outcomes in the four study settings. Using the previously developed latent classes, the current study aimed to expand on these findings by examining how different patterns of victimization experienced by youth may be differentially associated with psychosocial adjustment, and by exploring these associations both concurrently and over time. It was hypothesized that groups of youth in classes with higher victimization exposure at age 15 would have significantly worse concurrent emotional difficulties, self-rated health, and subjective wellbeing, and that victimization exposure would continue to predict poorer outcomes three years later after adjusting for scores at age 15.

Method

Sample

This study is a secondary analysis of publicly archived data originally collected in 2009 and 2013 as part of the Young Lives Study (www.younglives.co.uk), a longitudinal cohort study conducted in Ethiopia, two states in India, Peru, and Vietnam. These countries were selected for inclusion in Young Lives to reflect a diversity of culture and context while sharing challenges common to low-resource countries. According to the World Bank country classification, Ethiopia is considered low-income, India and Vietnam are considered lower-middle income, and Peru is an upper-middle income country (World Bank 2018). Participants were originally recruited in 2002 at age eight. Detailed information on the sampling methods used by the Young Lives team has been published elsewhere (Young Lives 2017); briefly, in each country the research team purposively identified 20 “sentinel sites” to represent the range of living experience in the country, with over-selection of relatively poorer sites (striving for a 3:1 ratio of “poor” to “non-poor” as operationalized within each country). Within each site, approximately 50 children in the target age range were then randomly sampled for study recruitment; participating children and their caregivers were subsequently interviewed every 3-4 years. In each country, the study sample has been compared with other nationally representative samples; in all countries the sample was shown to represent the diversity of the children in each country to an extent suitable for exploring causal relations and longitudinal dynamics (Young Lives 2017). With regard to examining peer victimization, this study is unique in that the samples are not school-based.

By 2009, loss to follow up across the four cohorts remained minimal (<5%) and relatively unbiased in terms of demographic characteristics (Barnett et al. 2013). At that time, youth were interviewed and also completed a self-administered questionnaire that assessed psychosocial adjustment, risk issues, and exposure to peer victimization. Excluding 65 youth who were interviewed at age 15 but were missing responses to the questions on peer victimization, cross-sectional data was available for 971 youth in Ethiopia, 967 in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, 638 in Peru, and 960 in Vietnam; this comprised the samples for the baseline models.

In 2013 at age 19, the Young Lives cohorts were again interviewed about psychosocial adjustment and risk issues, but were not reassessed for the same peer victimization exposures. Youth who were included in the baseline models were included in the longitudinal models if they provided follow-up data on at least one of the three psychosocial outcomes. This resulted in longitudinal samples of 904 (93.1%) in Ethiopia, 942 (97.4%) in India, 582 (91.2%) in Peru, and 865 (90.1%) in Vietnam. In Ethiopia, loss to follow-up was higher among girls than boys (11.3 vs. 2.6%), X2 (1, N = 971) = 28.5, p< .001. In Vietnam, loss to follow-up was higher among boys than girls (13.5 vs. 6.0%), X2 (1, N = 960) = 15.6, p< .001, and those lost to follow up had marginally higher mean peer victimization scores (M = 1.4 vs. M = 1.3), t(958) = 2.31, p= .020. Otherwise, loss to follow-up appeared to be generally independent of baseline demographics, psychosocial adjustment scores, or level of peer victimization (all p > .05).

Measures

The Young Lives study team has published their approach to survey development and data collection for cross-cultural research (Young Lives 2017). Instrument development included selection of previously tested instruments with good psychometric properties, translating and back-translating the survey instruments into multiple languages, and pilot-testing the survey in both urban and rural areas to ensure that not only the words but the underlying concepts were accurately translated across contexts. Data collectors received extensive training and were actively involved in piloting and refining the instruments.

Peer victimization

At age 15, youth reported past year exposure to peer victimization using the 9-item self-administered Social and Health Assessment Peer Victimization Scale (Mynard and Joseph 2000; Ruchkin et al. 2004), which has been used as a measure of bullying exposure in multiple studies internationally (Boyes et al. 2014; Cluver and Orkin 2009; Crookston et al. 2014; Karlsson et al. 2013; Stadler et al. 2010; Stickley et al. 2013). The instrument assesses physical, verbal, relational, and property victimization, as well as intimidation/space invasion, using a four-point response scale of “never”, “once”, “2-3 times”, or “4 or more times”. As described earlier, these nine items, dichotomized as “no” vs. “any” exposure, were previously used to empirically derive latent classes of victimization separately by country (Nguyen et al. 2016), resulting in a 2-class model in Peru, 3-class models in Ethiopia and Vietnam, and a 4-class model in India (Fig. 1). These latent classes were used as the peer victimization variable in the present analysis.

Emotional difficulties

At age 15, participants completed the five-item Emotional Difficulties subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman and Scott 1999), in which youth reported how true it is in the past six months that they: (1) worry a lot; (2) get a lot of headaches, stomach aches, or sickness; (3) are often unhappy, downhearted, or tearful; (4) are nervous in new situations, and (5) have many fears or are easily scared. The SDQ has been used extensively in international research, including previous research in all four country settings (Manrique Millones et al. 2013; Weiss et al. 2014; Whetten et al. 2011). Responses of “not true”, “a little true”, or “certainly true” produce a total emotional difficulties score of 0–10, with higher scores indicating more mental distress. At follow-up, these five questions were again administered. In Peru, the response options remained the same; in the other three samples, the response options were changed to “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, or “strongly agree”, producing a total emotional difficulties score of 0–15. Internal consistency ranged from α= .63−.71 across the samples at baseline and α= .66−.73 at follow-up.

Self-rated health

At both time points, participants responded to one global question asking youth to rate their health in general as very poor, poor, average, good, or very good, producing a score from 1–5 with higher scores indicating better perceptions of health. Self-ratings of health are considered a valid measure of overall health and are predictive of morbidity and mortality across socioeconomic groups in high and low-resource settings (Frankenberg and Jones 2004; McFadden et al. 2009; Subramanian et al. 2010; Subramanian et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2013), and this specific question is commonly used to assess positive health in cross-national research (Currie et al. 2012).

Subjective wellbeing

Youth were shown a picture of a ladder and presented with the question, “There are nine steps on this ladder. Suppose we say that the ninth step, at the very top, represents the best possible life for you and the bottom represents the worst possible life for you. Where on the ladder do you feel you personally stand at the present time?” Responses range from 1–9, with higher scores indicating greater subjective wellbeing. Although subjective wellbeing is a multi-faceted construct for which single-item measures have limitations, research suggests adequate validity and reliability of this approach (Diener 1984), this question has been used in more than 150 countries (Gallup, n.d.) and is included in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Wellbeing (OECD 2013).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive and exploratory analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp 2015). All subsequent analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). The same country-specific latent class models that were previously derived from these samples were re-fit for this analysis, treating the nine binary victimization items as latent class indicators and including sex and urban/rural status using a 1-step approach (Bandeen-Roche et al. 1997). Pairwise correlations between all key variables were examined; associations between class membership and each psychosocial adjustment outcome were then modeled separately using the Bolck, Croon, and Hagenaars (BCH) method (Asparouhov and Muthen 2014) in Mplus. In LCA, respondents can be assigned to their most likely class using posterior probabilities; however, because the classes are latent and an individual’s true class is unknown, measurement error must be accounted for when making these assignments. The BCH method treats the latent classes as multiple groups that are weighted according to the level of measurement error, allowing for comparison of distal outcomes across classes while accounting for measurement error and without influencing the latent class structure (Asparouhov and Muthen 2014). Because the automated BCH approach only compares unadjusted class means, the manual BCH approach was used to adjust all models for sex. Using the manual BCH approach, the LCA model is initially fit and class weights are exported for use in a second run in which the distal outcomes are regressed on both the latent classes and any adjustment variables (Asparouhov and Muthen 2014). When adjusting for covariates, the class-specific intercepts are interpreted as the independent influence of the latent class variable on the outcome and are compared across classes using chi-square tests of statistical significance (Asparouhov and Muthen 2014). For outcomes in which the global chi square test was significant at p< .05, pairwise comparisons were conducted with the significance level set at a more conservative p< .01 to account for repeat testing.

Missing data

Latent class models were estimated using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) to account for missing data in indicators, which peaked at 0.1% in Ethiopia, 0.2% in India, 3.0% in Peru, and 0.6% in Vietnam. Analysis of distal outcomes was conducted using listwise deletion. Missingness on outcomes peaked at less than 1% in the baseline samples and less than 2% in the follow-up samples, with the exception of the emotional difficulties score in Peru, which was missing for 2.4% of youth at baseline and 4.5% at follow-up.

Additional and sensitivity analyses

To further explain and confirm our longitudinal results, the data were examined in two additional ways. First, because of the potential bidirectional relationship between poor psychosocial adjustment and peer victimization (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015), an additional set of longitudinal LCA models were also run in which the corresponding baseline psychosocial adjustment score was controlled for. This was to understand whether there was a significant additional decline in longitudinal psychosocial adjustment specifically attributed to peer victimization rather than the potential carry-over effect of those with poorer psychosocial adjustment at baseline being more likely to be targets of peer victimization. Second, to confirm the robustness of the analytic approach, a similar set of analyses using multiple linear regression models with robust standard errors were used to regress psychosocial adjustment outcomes on a continuous peer victimization score, again adjusting for sex.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Baseline sample demographics are reported in Table 1 and comprise the same samples used in the original LCA. Age and sex distribution were similar across the four samples, whereas community context ranged from largely urban (Peru) to predominantly rural (Vietnam). The majority of youth were still enrolled in school at baseline, although whereas the other three samples reported an average of an 8th grade education, the Ethiopian sample reported an average of 5.5 years of completed schooling. Most of the youth across all countries lived with a biological parent, and a minority of youth (ranging from 11.1% in India to 26.8% in Ethiopia) lived in female-headed households. According to caregiver reports, half or more youth in each sample lived in households of average wealth (relative to other households in the area), with roughly a quarter of youth (nearly 2 in 5 in the India sample) living in poorer than average households. A majority of respondents in all samples reported at least one instance of past-year victimization at baseline. At follow-up, only half the total sample was still regularly attending full-time education (ranging from 45.5% in Vietnam to 57.3% in Ethiopia), and a small proportion of youth were married (5.2% in Ethiopia, 19.0% in India, 1.2% in Peru, and 11.7% in Vietnam).

Psychosocial Adjustment Outcomes

Table 2 reports mean emotional difficulties, self-rated health, and subjective wellbeing scores by country and time point. At baseline, country means on the outcomes suggested the study youth represented, on average, a relatively healthy population with low to moderate reporting of emotional difficulties (means ranging from 2.84 to 4.31), average to good self-reported health (3.50 to 4.04), and moderate subjective wellbeing (4.76 to 6.13). Country mean scores were fairly consistent at follow-up. Emotional difficulties scores were higher at follow up for those settings that changed the response options, but consistent with baseline in Peru. This suggests that perhaps the higher scores at follow-up are attributable to the change in response options rather than a true increase in emotional difficulties.

Pairwise correlations between all variables of interest, combined across the four samples, are reported in Table 3. The low correlations between each of the outcomes highlights their unique contribution to measuring overall psychosocial adjustment. Class-specific intercepts of the three outcome variables are reported in Table 4 (cross-sectional) and Table 5 (longitudinal). In all four countries, strong and significant differences in concurrent emotional difficulties scores across classes were observed. In Ethiopia, Peru, and Vietnam, these differences followed a dose-response pattern in which emotional difficulty scores steadily and significantly increased from the lowest to highest victimization classes (2.16 to 5.51 in Ethiopia, 4.05 to 5.75 in Peru, 3.34 to 5.79 in Vietnam, all p< .001; recall that the scale is 0–10, with higher scores indicating greater emotional difficulties). In India, all three of the victimized classes had similar emotional difficulty scores (5.01–5.40) that were higher than the score of the not victimized class (3.63; p< .001); the difference between the lowest and highest victimization score followed the same trends as the others but was not statistically significant (p= .1175), likely due to decreased power because of the smaller class size. At follow-up, class membership only significantly predicted emotional difficulties scores in India (p = .0007), where pairwise comparison showed mean scores were significantly higher among youth in the direct victimization class than those in the not victimized class (8.37 vs. 6.94, p = .0014).

Significant baseline trends of higher victimization associated with lower subjective wellbeing were also observed in Ethiopia (mean scores ranged from 4.90 to 4.11 across classes, p= .0118), India (5.16 to 3.62, p< .001), and Vietnam (5.70 to 4.61, p= .0174). The same baseline trend in Peru was not statistically significant (6.52 to 6.12, p= .1260). At follow-up, baseline class membership was no longer predictive of subjective wellbeing score in any country (p-values ranged from .2297 in Vietnam to .8937 in Ethiopia).

Baseline trends in self-rated health were similar in direction, however, non-significant in India (3.94 to 3.47, p= .1027) and Peru (3.82 to 3.67, p= .0538), and there were no notable differences in score across classes in Ethiopia (3.97 to 4.12, p= .5344). In Vietnam, the global chi-square test did suggest a significant trend (3.54 to 3.11, p= .0114), but pairwise comparisons showed no significant differences at p< .01. Longitudinally, although a trend of slightly lower self-rated health among those with higher victimization remained, these differences were not statistically significant in any setting (p-values ranged from .1036 in India to .3486 in Ethiopia).

Sensitivity Analyses

After controlling for baseline score in the longitudinal LCA models, no significant associations remained in any country between victimization class and either emotional difficulties (p-values range from .0547 in Peru to .5478 in India) or subjective wellbeing (p-values range from .1471 in India to .9276 in Vietnam). In Ethiopia, after controlling for baseline self-rated health a trend of higher longitudinal self-rated health among classes with higher victimization emerged (means ranged from 3.11 to 4.24), but was only marginally significant (p = .0345) and not robust to analysis approach. No similar trends were observed in the other countries (p-values ranged from .1170 in Peru to .8970 in Vietnam).

The linear regression approach largely affirmed findings of the LCA models. Adjusting for sex, a 1-point increase in peer victimization score was associated with significant increases in concurrent emotional difficulties score in all countries (β = .16 in Peru, .19 in India, and .20 in Ethiopia and Vietnam, all p < .001), small but significant decreases in concurrent self-rated health in India (β = −.01, p = .010), Peru (β = −.02, p = .002), and Vietnam (β = −.02, p < .001), and small but significant decreases in concurrent subjective wellbeing in Ethiopia (β = −,04 p = .007), India (β = −,06 p < .001), and Peru (β = −,04 p = .003). Longitudinally, a 1-point increase in peer victimization score was only associated with small increases in emotional difficulties scores in India (β = .06, p< .001), Peru (β = .09, p< .001), and Vietnam (β = .06, p= .002) and a small decrease in self-rated health in Peru (β = −.02, p= .006). Controlling for baseline score attenuated these associations further, with only marginally significant changes in longitudinal scores for emotional difficulties in India (β = .04, p= .029) and self-rated health in Peru (β= −.01, p= .046) remaining. Full results of these additional analyses are available on request.

Discussion

There is a lack of research examining peer victimization in low-resource countries, where differences in culture and context may limit the generalizability of findings from elsewhere. Studies in these settings have typically been cross-sectional and based on a single question (Due and Holstein 2008), precluding understanding of what is actually being experienced and how this may impact youth psychosocial adjustment over time. These limitations are of particular concern given that the experiences and perceptions of peer victimization are likely to vary by culture (Smith et al. 2002), and longitudinal outcomes of peer victimization are highly influenced by these dynamics (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015). The purpose of this study was to fill the gaps in the extant research regarding the longitudinal effects of peer victimization on psychosocial adjustment in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Using data from multiple sites across these four countries, we examined longitudinal outcomes, and leveraged a person-centered approach to understand the impact of patterns of peer victimization as experienced by youth in each country. Findings suggest consistent concurrent associations between peer victimization and poor psychosocial adjustment, but little lasting impact of these adverse experiences in emerging adulthood. Below these results are discussed in greater depth.

Concurrent Associations

As expected, a strong and consistent association was observed between the experience of peer victimization and higher risk of concurrent emotional difficulties in all four countries. Trends in associations between peer victimization and both lower subjective wellbeing and self-rated health were also in the expected direction, but smaller and concentrated primarily in the highest risk groups. In Ethiopia, previous research has postulated potentially negative effects of bullying but provided limited statistical support for these assertions (Aberra 2013; Save the Children Denmark 2008). Likewise, in Vietnam emotional distress associated with bullying has rarely been rigorously studied (Phuong et al. 2013). The current findings provide a substantial contribution to the literature on bullying and mental health in these settings. While the link between victimization and concurrent psychosocial adjustment is more clearly documented in India (e.g., Ramya and Kulkarni 2011) and Peru (e.g., Lister et al. 2015a), these new findings advance prior work by providing empirical evidence of significant associations between patterns of victimization experienced by youth in these settings and concurrent emotional distress.

Unlike the dose-response relationships between victimization and emotional difficulties observed in the other three countries, risk of concurrent emotional difficulties in India was elevated across all victimization classes relative to the non-victimized class. But this same trend did not hold for subjective wellbeing in India; rather, there was significantly lower subjective wellbeing in the direct vs. indirect victimization classes, which differed primarily by form of victimization experienced. In Vietnam, where the classes could also be distinguished by the consolidation of physical victimization in only the highly victimized class, there was the same trend of increased emotional difficulties associated with even some victimization, whereas the decrease in subjective wellbeing was associated only with the highly victimized class. Findings of similar associations with emotional difficulties across classes highlight the comparable needs of youth experiencing different forms of victimization and demonstrates the importance of recognizing and supporting youth experiencing non-physical forms of victimization, which may be less visible but associated with similarly poor adjustment (Baldry 2004; van der Wal et al. 2003). Regarding the less robust subjective wellbeing findings, it is possible that youth who are repeatedly physically victimized—a form of victimization that should be more visible to available supports—may have fewer other supportive resources to buffer the impact of victimization; an important protective factor highlighted in the literature (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015). It is possible that the observed differences in subjective wellbeing reflect the influence of more forms of adversity than peer victimization alone. Although these analyses did not control for other peer and familial factors, these findings highlight the need to explore these relationships further. In summary, cross-sectional findings do suggest that victimized youth in these settings are experience more emotional difficulties and are also likely to report lower concurrent health and wellbeing. This pattern of results is consistent with other studies showing similar consistent cross-sectional associations in low-resource countries (Brown et al. 2008; Fleming and Jacobsen 2010).

Longitudinal Associations

In contrast to the cross-sectional findings that were largely as expected, longitudinal analyses showed nearly no remaining association between adolescent victimization and the same indicators of psychosocial adjustment four years later, after controlling for sex. Further, even those few lingering longitudinal associations (e.g., emotional difficulties in India) were attenuated when controlling for baseline scores; given the likely reciprocal relationship between peer victimization and poor mental health (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015), it is unclear to what extent the few significant unadjusted longitudinal associations can be causally attributed to peer victimization exposure. Alternative analysis approaches confirmed that this lack of longitudinal impact was not due to the analytic approach, as even the few significant associations observed by simply regressing outcomes on a continuous peer victimization score were of very low magnitude (e.g.,: increasing emotional difficulty scores by only tenths of a point on a scale ranging from 0–10).The previous study by Pells and colleagues (2016) using the same dataset, but a different analytic approach, found similar trends of slightly negative, but mostly non-significant associations between adolescent victimization and later self-efficacy, self-esteem, parent relations, and peer relations. While this may have suggested null longitudinal findings should have been expected in the present study for the additional psychosocial outcomes evaluated, the study hypothesis had assumed that their independent examination of each form of victimization attenuated the findings, and that by accounting for the highly co-occurring experiences of multiple forms of victimization youth reported, the latent class approach would show more robust lasting impacts on psychosocial adjustment. In the Pells et al. (2016) study, stepwise models included a greater number of demographic control variables, but inclusion of these variables had little impact on the regression coefficients, suggesting current findings are unlikely to be largely affected by under-adjustment.

The present analysis and the analysis by Pells and colleagues (2016) provide robust support for the overall findings suggesting only modest lasting associations between adolescent peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adulthood in these study settings. Although there is literature suggesting that peer victimization does predict later psychosocial adjustment, the important caveat is that this is likely only the case for some victimized youth, and there is a great need to improve our understanding of the pathways leading to various adjustment outcomes (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015). For example, a meta-analysis of studies examining the link between peer victimization and depression showed that effect sizes were larger when the peer victimization occurred at a younger age (Ttofi et al. 2011). Past-year peer victimization in the present study was measured among 15-year old youth who were arguably past the period of early adolescence in which peer victimization is thought to peak (Espelage and De La Rue 2012); it is possible that exposure in this later developmental period has less long-term impact. Emerging adulthood reflects a developmental period in which changing daily tasks and activities represent a marked shift in peer relations; for example, at follow-up, nearly half of the youth in these samples were no longer attending school full-time, and a minority had married, resulting in markedly different peer interactions. Moreover, rapid economic and social change in these settings has likely positively impacted multiple facets of life in emerging adulthood for the young people in these samples (Woldehanna et al. 2011; Young Lives 2015). Understanding how these life changes may contribute to pathways of resilience even in the face of adolescent adversities such as peer victimization may provide valuable lessons for how to promote pathways to wellbeing in low and high resource settings alike.

Additionally, research suggests that youth with poorer mental health, who are at elevated risk of adverse psychosocial adjustment in adulthood, are also more likely to be targeted for bullying victimization (Lister et al. 2015b; Vaillancourt et al. 2013). Most studies, this one included, are unable to fully distinguish between causal associations and person-environment correlations in which individual vulnerabilities for later mental health problems are associated with risk of victimization, thereby potentially confounding measured associations. A recent study of over 11,000 twins that sought to control for genetic and environmental confounds demonstrated that bullying exposure did causally contribute to concurrent mental health problems, but these contributions dissipated over time and most associations were no longer significant after two years (Singham et al. 2017). Such findings, which are similar to those of the present work, further indicate potential pathways of resiliency that have, to date, been underexplored in peer victimization research—particularly in low-income and middle-income countries where so much of the work is cross-sectional.

The longitudinal findings in this paper should not undermine the large body of evidence (Hawker and Boulton 2000) overwhelmingly showing strong and consistent associations between victimization and concurrent associations on youth mental health, which clearly illustrates the serious need to identify and provide support to youth who are affected by peer victimization. By continuing to explore pathways to resilience in future work, research will be better able to highlight ways in which matching services to young people’s distinct needs can optimize their potential to thrive following exposure to peer victimization (McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015).

Strengths and Limitations

The current findings provide a meaningful contribution to the bullying victimization literature in low-resource settings, where most existing research is cross-sectional and subject to serious methodologic limitations. This study also illustrates the utility of a person-centered approach to better understand patterns of victimization and their impact, as the latent classes showed greater distinction in outcomes than did the regression approach, in which even significant associations were of very small magnitude. Findings of concurrent emotional difficulties even in moderately victimized classes and those with little physical victimization further demonstrates the need to improve ability to recognize and intervene on less-visible forms of peer victimization.

These analyses have certainly not accounted for all possible factors potentially impacting the explored associations. In fact, the models were minimally adjusted, due in part to the availability of comparable variables across all four samples and statistical modeling constraints. In particular, by taking a cross-national approach the study did not delve deeply into the social and environmental contexts in which peer victimization was occurring and youth were developing in each of these settings. Use of a standard scale also precluded assessment of culturally unique forms of victimization, instead assuming that the victimizing experiences assessed would be perceived negatively in all settings. Perhaps most importantly, this study was not able to account for changing peer victimization dynamics over time as the nine items assessed at age 15 were not included in the follow-up interviews. Finally, although country names are used in this paper, this data represents samples that were initially selected to over-represent high poverty areas and are therefore not nationally representative of the countries they are drawn from.

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of peer victimization worldwide (Craig et al. 2009; Due and Holstein 2008) and the lack of information about the nature and impact of these experiences in low-resource countries, expanding the evidence-base is critical to inform culturally and contextually relevant intervention approaches. The purpose of the current analysis was to examine how patterns of peer victimization experienced by adolescents in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam were associated with a range of psychosocial adjustment indicators. Using previously developed latent class models conditioned on sex and community context, findings show victimization to be strongly and consistently associated with poor concurrent psychosocial adjustment, but that these associations had largely attenuated at follow-up in emerging adulthood. These results are well situated within a large body of evidence from high-income countries and a growing number of findings from low-resource countries that suggest that regardless of location in the world, bullying and other aggressive acts by peers are a strong and consistent indicator of risk for cross-sectional poor psychosocial adjustment. These findings are particularly relevant for prevention efforts to sensitize parents, teachers, and other protective resources to recognize these behaviors and to understand that they are not just a harmless rite of passage. At the same time, the current pattern of results suggested a decreased association between peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment over time, which highlights the potential to learn powerful lessons from low-resource and culturally diverse settings about factors contributing to positive outcomes after exposure to adversity. Such work holds promise for strategies that could be applied in low and high resource settings alike.

References

Aberra, M. (2013). The Case of Selected Schools in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa University. http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/7492.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthen, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary second model. Mplus Web Notes: No. 21.

Baldry, A. C. (2004). The impact of direct and indirect bullying on the mental and physical health of Italian youngsters. Aggressive Behavior, 30(5), 343–355.

Bandeen-Roche, K., Miglioretti, D. L., Zeger, S. L., & Rathouz, P. J. (1997). Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(440), 1375–1386.

Barnett, I., Ariana, P., Petrou, S., Penny, M. E., Duc, L. T., Galab, S., & Boyden, J. (2013). Cohort profile: the young lives study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(3), 701–8.

Bellmore, A. D., Witkow, M. R., Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2004). Beyond the individual: the impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims’ adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1159–1172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159.

Boyes, M. E., Bowes, L., Cluver, L. D., Ward, C. L., & Badcock, N. A. (2014). Bullying victimisation, internalising symptoms, and conduct problems in south african children and adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1313–24.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2013). A latent class approach to examining forms of peer victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 839–849.

Brown, D. W., Riley, L., Butchart, A., & Kann, L. (2008). Bullying among youth from eight African countries and associations with adverse health behaviors. Pediatric Health, 2(3), 289–299.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F.-A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204010362954.

Cluver, L., & Orkin, M. (2009). Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 69(8), 1186–93.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., & Pickett, W. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(Suppl 2), 216–24.

Crookston, B. T., Merrill, R. M., Hedges, S., Lister, C., West, J. H., & Hall, P. C. (2014). Victimization of Peruvian adolescents and health risk behaviors: young lives cohort. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 85.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O. R., Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Health Policy for children and adolescents, No 6. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin., 95(3), 542–575.

Due, P., & Holstein, B. E. (2008). Bullying victimization among 13 to 15 year old school children: Results from two comparative studies in 66 countries and regions. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 209–222.

Espelage, D. L., & De La Rue, L. (2012). School bullying: its nature and ecology. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 24(1), 3–10.

Fleming, L. C., & Jacobsen, K. H. (2010). Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promotion International, 25(1), 73–84.

Frankenberg, E., & Jones, N. R. (2004). Self-rated health and mortality: does the relationship extend to a low income setting? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45(4), 441–452.

Gallup. (n.d.). Understanding How Gallup Uses the Cantril Scale. http://www.gallup.com/poll/122453/understanding-gallup-uses-cantril-scale.aspx Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(1), 17–24.

Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455.

Karlsson, E., Stickley, A., Lindblad, F., Schwab-Stone, M., & Ruchkin, V. (2013). Risk and protective factors for peer victimization: a 1-year follow-up study of urban American students. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0507-6.

Kshirsagar, V. Y., Agarwal, R., & Bavdekar, S. B. (2007). Bullying in schools: prevalence and short-term impact. Indian Pediatrics, 44(1), 25–28.

Lanza, S. T., & Cooper, B. R. (2016). Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Development Perspectives, 10(1), 59–64.

Lanza, S. T., & Rhoades, B. L. (2013). Latent class analysis: an alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science, 14(2), 157–68.

Lister, C., Merrill, R. M., Vance, D. L., West, J. H., Hall, P. C., & Crookston, B. T. (2015a). Victimization among peruvian adolescents: insights into mental/emotional health from the young lives study. Journal of School Health, 85(7), 433–440.

Lister, C., Merrill, R. M., Vance, D., West, J. H., Hall, P. C., & Crookston, B. T. (2015b). Predictors of peer victimization among Peruvian adolescents in the young lives cohort. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 27(1), 85–91.

Manrique Millones, D. L., Ghesquière, P., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2013). Evaluation of a parental behavior scale in a peruvian context. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 885–894.

Masiello, M. G. (2014). Public health and bullying prevention. In M. G. Masiello & D. Schroeder(Eds.), A public health approach to bullying prevention. 1st edn. (pp. 1–22). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

McCutcheon, A. L. (1987). Latent class analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70(4), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039174.

McFadden, E., Luben, R., Bingham, S., Wareham, N., Kinmonth, A. L., & Khaw, K. T. (2009). Does the association between self-rated health and mortality vary by social class? Social Science and Medicine, 68(2), 275–280.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus User’ s Guide (Seventh Ed). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 169–178.

Nguyen, A. J., Bradshaw, C., Townsend, L., Gross, A. L., & Bass, J. (2016). A latent class approach to understanding patterns of peer victimization in four low-resource settings. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0086.

Nylund, K., Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: what does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78(6), 1706–22.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pells, K., Portela, M. J. O., & Revollo, P. E. (2016). Experiences of peer bullying among adolescents and associated effects on young adult outcomes: longitudinal evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Viet Nam. Discussion Paper UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 03 (61).

Phuong, T. B., Huong, N. T., Tien, T. Q., Chi, H. K., & Dunne, M. P. (2013). Factors associated with health risk behavior among school children in urban Vietnam. Global Health Action, 6, 1–9.

Ramya, S. G., & Kulkarni, M. L. (2011). Bullying among school children: prevalence and association with common symptoms in childhood. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 78(3), 307–310.

Roman, M., & Murillo, J. (2011). Latin America: school bullying and academic achievement. CEPAL Review, 104, 37–53.

Rosato, N. S., & Baer, J. C. (2012). Latent class analysis: a method for capturing heterogeneity. Social Work Research, 36(1), 61–69.

Ruchkin, V., Schwab-Stone, M., & Vermeiren, R. (2004). Social and health assessment (SAHA): Psychometric development summary. New Haven: Yale University.

Save the Children Denmark. (2008). A study on violence against girls in primary schools and its impacts on girls’ education in Ethiopia. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.

Sawyer, A. L., Bradshaw, C. P., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2008). Examining ethnic, gender, and developmental differences in the way children report being a victim of “bullying” on self-report measures. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(2), 106–114.

Singham, T., Viding, E., Schoeler, T., Arseneault, L., Ronald, A., Cecil, C. M., & Pingault, J. B. (2017). Concurrent and longitudinal contribution of exposure to bullying in childhood to mental health: the role of vulnerability and resilience. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(11), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2678.

Smith, P. K., Cowie, H., Olafsson, R. F., & Liefooghe, A. P. D. (2002). Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Development, 73(4), 1119–1133.

Stadler, C., Feifel, J., Rohrmann, S., Vermeiren, R., & Poustka, F. (2010). Peer-victimization and mental health problems in adolescents: are parental and school support protective? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(4), 371–86.

StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Stickley, A., Koyanagi, A., Koposov, R., McKee, M., Roberts, B., & Ruchkin, V. (2013). Peer victimisation and its association with psychological and somatic health problems among adolescents in northern Russia. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7(1), 15.

Subramanian, S. V., Huijts, T., & Avendano, M. (2010). Self-reported health assessments in the 2002 World Health Survey: How do they correlate with education? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(2), 131–138.

Subramanian, S. V., Subramanyam, M. A., Selvaraj, S., & Kawachi, I. (2009). Are self-reports of health and morbidities in developing countries misleading? Evidence from India. Social Science and Medicine, 68(2), 260–265.

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(2), 63–73.

Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H. L., McDougall, P., & Duku, E. (2013). Longitudinal links between childhood peer victimization, internalizing and externalizing problems, and academic functioning: developmental cascades. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1203–15.

van der Wal, M. F., de Wit, C. A. M., & Hirasing, R. A. (2003). Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics, 111(6), 1312–1317.

Weiss, B., Dang, M., Trung, L., Nguyen, M. C., Thuy, N. T. H., & Pollack, A. (2014). A nationally representative epidemiological and risk factor assessment of child mental health in vietnam. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 3(3), 139–153.

Whetten, K., Ostermann, J., Whetten, R., O’Donnell, K., & Thielman, N. (2011). More than the loss of a parent: potentially traumatic events among orphaned and abandoned children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(2), 174–82.

Woldehanna, T., Gudisa, R., Tafere, Y., & Pankhurst, A. (2011). Understanding changes in the lives of poorchildren: initial findings from Ethiopia. Oxford: Young Lives.

Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–85. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667.

World Bank. (2018). Country and Lending Groups. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups Accessed 23 July 2018.

Wu, S., Wang, R., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., Wu, M., Yan, X., & He, J. (2013). The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: a population-based study. BMC Public Health, 13, 320.

Young, L. (2015). Young Lives Theory of Change. Oxford, UK: Young Lives. Available online at https://www.younglives.org.uk/content/young-lives-theory-change.

Young, L. (2017). A guide to Young Lives Research. Oxford, UK: Young Lives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ji Hoon Ryoo at the University of Virginia for consulting on the analytic approach.

Authors’ Contributions

A.J.N. conceived of the study design, performed the statistical analysis, and led the data interpretation and manuscript development. C.B.P., L.T., A.G., and J.B. participated in the study design, interpretation, and manuscript development. A.G. also assisted with the analytic approach. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding support for AJN was provided by the NIMH Child Mental Health Services and Service Systems Research Training Grant (5T32MH019545-23).

Data Sharing and Declaration

The data used in this publication come from Young Lives, a 15-year study of the changing nature of childhood poverty in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam (www.younglives.org.uk). Young Lives is funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID), with co-funding from Irish Aid. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). They are not necessarily those of Young Lives, the University of Oxford, DFID or other funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, A.J., Bradshaw, C.P., Townsend, L. et al. It Gets Better: Attenuated Associations Between Latent Classes of Peer Victimization and Longitudinal Psychosocial Outcomes in Four Low-Resource Countries. J Youth Adolescence 48, 372–385 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0935-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0935-1