Abstract

Morality, competence, and sociability have been conceptualized as fundamental dimensions on which individuals ground their evaluation of themselves and of other people and groups. In this study, we examined the interplay between self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability and relationship quality within the core social contexts with which adolescents have extensive daily interactions (family, friends, and school). Participants were 916 (51.4% girls; Mage = 15.64 years) adolescents involved in a three-wave longitudinal study with annual assessments. The results of cross-lagged analyses indicated that (a) self-perceived morality was more important than self-perceived competence and sociability in strengthening family, friend, and school relationships; and (b) high-quality friendships led to increasing levels of self-perceived morality over time. Overall, this evidence advances our theoretical understanding of the primacy of morality from a self-perspective approach and highlights the developmental importance of friends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When individuals interact with other people, they evaluate others’ characteristics and traits and express behavioral intentions based on this assessment. In the social psychology literature, morality, competence, and sociability have been conceptualized as core dimensions on which individuals ground their evaluation of other persons and groups (Brambilla and Leach 2014; Leach et al. 2007). The purpose of this longitudinal study was to adopt a developmental self-perspective by considering how adolescents’ self-perception in terms of morality, competence, and sociability is related to the perception of meaningful relationships within the most important contexts of this life period, namely family, friends, and school (cf. Lerner and Steinberg 2009).

Morality, Competence, and Sociability as Fundamental Dimensions of Social Judgment

When individuals interact with other people, they are motivated to gather information pertaining to others’ competence (also referred to as agency), indicating the ability to pursue intents and goals, as well as warmth (also referred to as communion), which denotes traits related to friendliness, benevolence, and morality (e.g., Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014; Fiske et al. 2007). The dimension of warmth is particularly important since individuals are fundamentally interested in understanding whether other people are friendly and kind, and whether they can be approached safely (Cuddy et al. 2008). Although this two-dimensional model of social judgment is widely used, recently it has been highlighted that warmth comprises two distinct evaluative components (Leach et al. 2007): morality, which provides information about others’ intentions, and is conceived as perceived correctness of social behavior, honesty, and trustworthiness; and sociability, which indicates the ability to have good relationships with others (Brambilla and Leach 2014; Leach et al. 2015). Empirical research has shown that this more refined three-dimensional model comprising morality, sociability, and competence provides a better fit to the data than the bi-dimensional model consisting of warmth (in which morality and sociability are grouped together) and competence (Leach et al. 2007). This shows the heuristic value of considering the three dimensions as distinct.

Consistent with the three-dimensional model of social judgment (Leach et al. 2007), morality, competence, and sociability make unique contributions to other-perception (Brambilla and Leach 2014). Notably, traits related to morality are far more important than other characteristics in shaping person as well as group perceptions (e.g., Goodwin et al. 2014; Moscatelli et al. (2018)). In fact, people make spontaneous inferences about other’s trustworthiness on the basis of very little information, and evaluations of morality which are made as soon as 100 ms after presentation of a face, tend to be more stable in time than evaluations along other dimensions (Willis and Todorov 2006). Trustworthiness is also considered as the most desirable characteristic for an ideal person to possess (Cottrell et al. 2007) and predicts the global impression of individuals and groups better than information pertaining to competence and sociability (e.g., Goodwin et al. 2014). Recently, it has been shown that competent and sociable people are evaluated positively only when they are also moral (Landy et al. 2016). Furthermore, people also show an enhanced capacity to temporally synchronize their actions with unknown others who are high versus low in morality, whereas behavioral synchrony is not affected by others’ perceived sociability (Brambilla et al. 2016). Taken together, this evidence points to the primacy of morality in others’ perception.

As much as morality, competence, and sociability are used for assessing and judging others’ traits and behaviors, they are likely to play also a key role in self-perception. More specifically, self-perception refers to “attributes or characteristics of the self that are consciously acknowledged by the individual through language—that is, how one describes oneself” (Harter 1999; p. 3). In this vein, individuals can evaluate themselves assessing the extent to which they possess the traits of morality, competence, and sociability.

So far, most research assuming a self-perspective approach has been conducted by adopting a bi-dimensional model of social judgment, addressing how individuals evaluate themselves in terms of morality and competence (Abele and Wojciszke 2007; Wojciszke 2005). This literature has indicated that usually individuals perceive themselves as more moral, but not more competent, than others (i.e., the Muhammad Ali effect; Allison et al. 1989; Van Lange and Sedikides 1998). Thus, a self-serving bias in self-perception, such that the self is generally perceived as “holier than thou” (Epley and Dunning 2000), has been documented.

However, less is known on the relational and social implications of self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability. This study sought to address this gap in the literature in a twofold way, by examining how these dimensions have an impact on the ways in which individuals perceive relationships across different contexts and, at the same time, are shaped by such relationships. Such contribution is in line with Harter’s (1999) developmental perspective, according to which self-perception matters since they it has significant implications for understanding how individuals adapt to their social reality and, simultaneously, this self-perception is strongly rooted in relationships unfolding in main developmental contexts. In this vein, a cross-fertilization approach was adopted by combining the three-dimensional model of social judgment comprising morality, competence, and sociability (Leach et al. 2007) and a developmental perspective according to which these dimensions can form resources that individuals put into play within the most important contexts of their lives, namely family, friends, and school.

The Role of Morality, Competence, and Sociability in Structuring Social Relationships in Adolescent Contexts

In adolescence, family (e.g., Laursen and Collins 2009), friends (e.g., Brown and Larson 2009), and school (e.g., Elmore 2009) contexts represent the main pillars for the development of young people. On the one hand, parent-child relationships tend to become more conflictual in adolescence (e.g., De Goede et al. 2009). On the other hand, adolescents and their parents report that their relationships are appraised positively (Arnett 1999) and, although they may disagree on issues related to personal appearance (e.g., clothing style) and daily organization (e.g., curfews), they share core values (such as the importance of honesty and education). Moreover, adolescents and their parents retain a strong sense of connectedness and mutual affection (Smetana et al. 2006). Changes in parent-child relationships can be understood considering the adolescents’ normative pursuit of autonomous goals and search for their own identity (e.g., Crocetti et al. 2017, 2011) that go together with an increment of friendships (Tsai et al. 2013).

In fact, adolescents spend increasingly less time with family and more time with their friends (Brown and Larson 2009), which become important and salient sources of support (Tarrant 2002). Identification with friends has strong implications for adolescents’ development of personal identity (Albarello et al. 2018), because in the context of friendships adolescents can experiment themselves, considering alternatives and trying out different behaviors, and can observe the consequences of their and others’ action. Such experiences are of utmost importance for their self-perception.

At the same time, adolescents have continuous and consistent interactions in the school context, with both teachers and classmates. Such relationships are influential for adolescents’ self-understanding and for developing a personal orientation towards institutions (Rubini and Palmonari 2006). Thus, in family, peer, and school contexts, adolescents have meaningful experiences with their parents, friends, teachers, and classmates that are important for developing their own identity and personality (e.g., Crocetti et al. 2017; Erentaitė et al. 2018).

In addition, transactional models of development (e.g., Sameroff 2009) suggest that as adolescents develop and achieve a secure sense of identity, together with personal and social skills, they improve their relationships with significant others (for a review, see Meeus 2016). Consistent with this reasoning, self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability can work as resources that individuals use to implement or strengthen relationships within different social contexts. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the combined effect of one’s own perceived morality, competence, and sociability on relationship quality, referring to the extent to which adolescents have warm and supportive relationships with parents, friends, teachers, and classmates (e.g., Lerner and Steinberg 2009).

Building upon the social psychology literature on social judgment (e.g., Brambilla and Leach 2014), a primacy of morality can also be hypothesized within a developmental perspective. More specifically, since it has been consistently proved that individuals rely more on morality (rather than on competence and sociability) in the process of evaluating other people and groups (Landy et al. 2016; Leach et al. 2007), when shifting to a self-perspective approach it can be expected that morality would emerge as the resource that is most important to strengthen interpersonal relationships in multiple social contexts.

The Other Side of the Story: How Family, Friend, and School Relationships Can Enhance Adolescents’ Self-Morality, Competence, and Sociability

In their family, friend, and school contexts, adolescents can play different roles (Sherif and Sherif 1964), identify with meaningful others (Bandura 1977), learn social skills, achieve new competences, and increase their knowledge of formal and informal norms and rules (Emler and Reicher 1995; Rubini and Palmonari 2006; Menegatti and Rubini, 2012). Although these contexts are important for adolescent growth, until now most research has examined the separate influence of each context on adolescent developmental outcomes (e.g., family influences on adolescents’ empathy and prosocial behavior; Yoo et al. 2013), or it included up to two contexts (e.g., family and friend influences on adolescent identity; Meeus et al. 2002). Only a minority of studies has comprehensively investigated the combined effects of family, friend, and school contexts on adolescent adjustment and problem behaviors (e.g., family, friend, and school influences on adolescent alcohol use; Shortt et al. 2007). More specifically, parental relationships were the most consistent protective factor for decreasing suicidal attempts and, but only for boys with prior suicidal attempts, school relationships amplified the positive effects of parental relationships when peer relationships were poor (Kidd et al. 2006). However, this centrality of family relationships was not confirmed by Way and Robinson (2003), who found that, among ethnic minority low-SES adolescents, school relationships were more impactful on self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Thus, more research on the combined effects of these three main contexts is needed. The current study sought to advance this line of study by examining the combined effects of relationships in family, friend, and school contexts on adolescent development of symbolic resources.

All the experiences that adolescents have across different contexts might influence their self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability (Harter 1988, 1999). This reasoning is rooted in theories on self-perception (Cooley 1902; Leary 2005), according to which self-views are grounded on social interactions with significant others. For instance, when individuals consolidate their interpersonal relationships and receive positive feedbacks about their behavior, they perceive this as a social validation of themselves (Christy et al. 2016; Crocetti et al. 2016).

Thus, on the one hand, adolescents put their morality, competence, and sociability into play in their life contexts; on the other hand, their social interlocutors can provide feedbacks and enact reciprocal behaviors, which in turn may further reinforce adolescents’ conceptions of their morality, competence, and sociability. Thus, drawing from theories on self-perception (Cooley 1902; Harter 1999; Leary 2005), it is possible to further hypothesize that high-quality family, friend, and school relationships could influence adolescents’ self-perception over time, especially in terms of morality. Since morality is the dimension that we expected to have the strongest effects in consolidating relationships in multiple contexts, it should also be the one that would be most strengthened by these positive interactions.

Current Study

In the light of the aforementioned contentions, in this longitudinal study a self-perspective approach was adopted to disentangle associations between perceived morality, competence, sociability and quality of relationships within adolescent social contexts (family, friend, and school contexts). Building upon the knowledge achieved with the three-dimensional model of social judgment (Leach et al. 2007) and seeking to advance it with a developmental framework, it was expected that morality would play a primary role compared to the other dimensions. In other words, self-perceived morality over time would have stronger effects than competence and sociability on improving family, friend, and school relationships (Hypothesis 1). In addition to this primacy of morality, bidirectional effects are also expected, such that high-quality relationships could over time positively augment adolescents’ self-morality (Hypothesis 2).

Methods

Participants

Data for this study were drawn from the longitudinal research project “Mechanisms of promoting positive youth development in the context of socio-economical transformations (POSIDEV)”. Participants for the current study were 916 (51.4% girls) adolescents attending grades 9 and 10 from high schools located in Northeastern Lithuania. At baseline, the age of participants ranged from 14 to 17 (Mage = 15.64, SDage = 0.70). The sample was diverse in terms of family and socio-economic backgrounds. Most participants lived with two parents (68.5%); the remaining participants had a range of other family situations owing to parental divorce (18.4%), loss (4.7%), and migration (4.1%). Regarding the socio-economic status, 26% received state economic support (free nutrition at school), and in 20.8% of cases at least one of the parents was jobless. The sample was homogeneous in terms of ethnic background (i.e., absolute majority of the participants were Lithuanian and 0.76% were of different ethnic background).

Participants provided information for three waves, with one-year intervals between each wave. Of the original sample (N = 916), 871 (response rate 95.09%) and 784 (response rate 85.59%) adolescents participated at T2 and T3 data collections, respectively. The results of Little’s (1988) Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test yielded a χ2/df value of 1.70 Therefore, all 916 participants could be included in the analyses conducted by means of the Full Information Maximum Likelihood procedure available in MplusFootnote 1.

Procedure

All high schools in Utena district municipality (Northeastern Lithuania) were selected for participation in the POSIDEV project. This municipality is representative of a typical Lithuanian small city. The study protocols were approved by the ethical committee of the Department of Psychology of the Mykolas Romeris University. During the introductory meeting adolescents were informed about the purpose of the study and that their participation would be completely voluntary. The parents were informed about the study through a written letter (distributed via e-diary and, additionally, a paper copy was given to the adolescent) and asked to contact the school or the investigators if they did not want their children to participate; thus, the parents had opportunity to withdraw their child from the study at any time.

T1, T2, and T3 assessments took place in February–May 2013, 2014, and 2015 respectively. Before each wave, school administration and prospective participants were informed about the date and time of the assessment. The researchers and several trained research assistants administered the questionnaires at the schools during regular class hours. The students who were absent on the day of data collection were contacted the following week by the research assistants to arrange for the completion of the questionnaires. The adolescents were not paid for participation, but all students who completed the questionnaires were eligible for a lottery reward (i.e., they could receive one of these alternative prizes: USB flash drive, issue of popular “Psychology” journal, paper notebook, etc.).

Measures

All study measures were translated from English into Lithuanian language following international gold standard recommendations. Translation was carried out in four steps. (1) Four Lithuanian versions, translated from English by four independent translators (three researchers of the project and a professional translator) were produced and (2) they were compared by an expert panel, consisting of the original translators and bilingual experts in the field. The panel members discussed the inadequate expressions/concepts of the translation until a satisfactory version was reached. (3) The accuracy of the translated instruments was controlled by comparing blind back-translations to English with the measure original versions. No inconsistencies were revealed at this step. (4) A pilot study showed sufficient internal consistency and adequate face validity of the instrument. The complete list of items (both in English and in Lithuanian) is available in the supplementary material.

Morality, competence, and sociability

Adolescents rated the extent to which they perceive themselves to be moral, competent, and sociable at each wave by filling 15 items (five for each dimension) of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescence (SPPA; Harter 1988). Example of items are (see the supplementary material for the full list): “I usually do the right thing” (morality); “I feel that I am pretty intelligent” (competence); and “I know how to become popular” (sociability). All items were scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (not true for me at all) to 4 (very true for me). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas at T1, T2, and T3 were .65, .61, and .67 for morality; .72, .71, and .73 for competence; and .76, .73, and .73 for sociability, respectively.

Family, friend, and school relationships

Adolescents rated the perceived quality of relationships within family and school contexts at each wave by filling 11 items (five for family and six for school) of the Profiles of Student Life-Attitudes and Behaviors Survey (PSL-AB; Benson et al. 1998). Furthermore, they reported about their friendships by filling four items of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden and Greenberg 1987; Nada Raja, McGee, & Stanton, 1992). Example of items include (see the supplementary material for the full list): “In my family, I feel useful and important” (family); “My teachers really care about me” (school); and “I trust my friends” (friends). All items were scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas at T1, T2, and T3 were .85, .89, and .89 for family; .79, .83, and .85 for school; and .87, .91, and .93 for friend relationships, respectively.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Bivariate correlations among study variables were computed. The results are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability were significantly and positively related to quality of relationships in family, friend, and school contexts. In terms of magnitude, these correlations were generally small-to-moderate or moderate-to-large according to Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks.

Cross-Lagged Analyses

The purpose of this study was to examine directions of associations between self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability and family, friend, and school relationships. In order to reach this aim cross-lagged analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 2012), by means of the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator (Satorra and Bentler 2001)Footnote 2It was tested a model in which cross-lagged effects and within-time correlations among all study variables were estimated controlling for one-year and two-year stability paths. The model fit was tested relying on multiple indices (Byrne 2012): the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), with values higher than .90 indicative of an acceptable fit and values higher than .95 suggesting an excellent fit; and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with values below .08 indicative of an acceptable fit and values less than .05 representing a good fit.

To model the longitudinal associations as parsimoniously as possible, time-invariance of cross-lagged effects and T2–T3 within-time correlations (correlated changes) was tested. Thus, three models were compared (M): the baseline unconstrained model (M1), the model assuming time-invariance of cross-lagged associations (M2), and the model assuming invariance of both cross-lagged paths and T2-T3 within-time correlations (M3). To determine significant differences between these nested models at least two out of these three criteria had to be matched: ΔχSB2 significant at p < .05 (Satorra and Bentler 2001), ΔCFI ≥ −.010, and ΔRMSEA ≥ .015 (Chen 2007). The findings clearly supported the assumption of time-invariance (see Table 2). Thus, the most parsimonious model (M3) with time-invariant cross-lagged paths and T2–T3 within-time correlations could be retained as the final one.

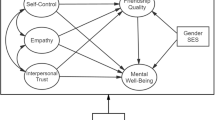

This model provided an excellent fit to the data (see Table 2). Significant cross-lagged effects are reported in Fig. 1. As can be seen, self-perceived morality was significantly and positively associated over time to quality of relationships within all social contexts (family, friends, and school). In addition, sociability was significantly linked to an improvement in friendships. Looking at cross-lagged paths from contexts to self-perceived morality, sociability, and competence, there was only one significant and positive effect, from friendships to morality. Taken together, these findings highlighted the expected primacy of morality.

Results of the cross-lagged model: Standardized cross-lagged effects between morality, competence, and sociability, and adolescent contexts. For sake of clarity, only significant cross-lagged paths from morality, competence, and sociability to quality of relationships and from quality of relationships to morality, competence, and sociability are reported. At T2 and T3, values reported above each variable indicate portions of explained variance. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

These results were controlled for stability paths (see Table 3), which were largely comparable across variables. Finally, within-time correlations (see Table 4) were all statistically significant and positive both at T1 and at T2–T3 (correlated changes). Portions of explained variance were high for all factors, with values between 29% and 48% (see Fig. 1).

Sensitivity Analyses

Ancillary multi-group analyses indicated that the results were not moderated by adolescents’ gender. In fact, the constrained model (χ2 = 200.966, df = 180, TLI = .993, CFI = .995, RMSEA = .016 [.000, .027]), in which cross-lagged paths were fixed to be equal across gender groups, did not differ significantly (ΔχSB2 = 28.795, Δdf = 30, p = .528; ΔCFI = .000, ΔRMSEA = -.002) from the unconstrained model (χ2 = 172.489, df = 150, TLI = .991, CFI = .995, RMSEA = .018 [.000, .030]), in which these paths could vary across gender groups. Similarly, the results were not moderated by adolescents’ socioeconomic status (SES). Indeed, the constrained model (χ2 = 217.304, df = 180, TLI = .988, CFI = .992, RMSEA = .022 [.007, .031]), in which cross-lagged paths were fixed to be equal across SES groups (participants receiving state economic support were compared with those who did not receive it), did not differ significantly (ΔχSB2 = 25.595, Δdf = 30, p = .696; ΔCFI = .001, ΔRMSEA = −.003) from the unconstrained model (χ2 = 192.426, df = 150, TLI = .984, CFI = .991, RMSEA = .025 [.013, .035]), in which these paths could vary across the two SES groups. Overall, these sensitivity analyses point to the generalizability of the study findings across gender and SES groups.

Discussion

Morality, competence, and sociability have been conceptualized as core dimensions of social judgment (Leach et al. 2007). If on the one hand, a wide social psychological literature has highlighted their importance in the process of evaluating other people and groups (e.g., Brambilla and Leach 2014 for a review), on the other hand, less was known about the developmental implications of self-perception along these dimensions. In this longitudinal study, a cross-fertilization approach was adopted by examining how self-perceived morality, competence, and sociability are intertwined with the major contexts in which adolescents establish meaningful relationships and achieve important goals.

In this way, the theoretical understanding of the importance of these dimensions was advanced in three main directions. First, evidence showed that morality turned out to play a primary role even in a self-perspective approach. In this vein, morality appears as a core dimension of self-perception that can produce longitudinally major social benefits, such as improving over time relationships in meaningful life settings. Second, the primacy of morality was consistently documented across multiple contexts that are important for adolescents, comprehensively analyzing family, friend, and school contexts. Self-perceived morality improved relationship quality in all the three social contexts examined. Sociability also contributed to consolidating relationships, but this effect was limited to the friend context. Competence did not have any longitudinal effect on adolescent relationships. Third, in addition to these effects, some evidence of bidirectionality was also found: high-quality friendships led to increasing levels of self-morality over time.

The Primacy of Self-Perceived Morality in Strengthening Relationships in Family, Friend, and School Contexts

In line with the first hypothesis, the results consistently highlighted the primacy of self-perceived morality (over competence and sociability) in predicting longitudinal variations in the quality of adolescents’ relationships across different contexts. Higher levels of adolescent’s perceived morality consolidated family, friend, and school relationships. Thus, by adopting a dynamic approach it was found that the primacy of morality is not only contingent on a specific time point but also unfolds over time, pointing to the role of morality as a source of improvement for the quality of relationships. Notably, “morality helps us live together in interdependent groups” (Carnes et al. 2015; p. 359) and its importance is found across different types of groups. Very likely this is because enacting moral behaviors strengthens reciprocal trust within groups as a fundamental component of social life. Indeed, this study highlighted consistent evidence of this across the three core contexts of adolescents’ daily life, namely family, friends, and school.

These results point to the implications of morality in self-perception. Jordan and Monin (2008) showed that, when individuals feel threatened they increase their perceived morality (but not their competence) as a strategy to restore a positive view of themselves. In more general terms, the evidence collected in this study shows the primacy of self-perceived morality (but not competence) as an effective resource to strengthen relationships within multiple social contexts with a longitudinal perspective. In turn, in a positive loop, positive relationships within the contexts of development increase individuals’ perceived morality.

Besides the longitudinal effects of morality on family, friend, and school relationships, the results also highlighted a positive effect of sociability that strengthened relationships over time but only in the friend context. In adolescence, individuals strive to being accepted by their friends, building and maintaining good relationships with them (e.g., Brown and Larson 2009). High self-perceived sociability indicates adolescents’ confidence in their capacity of establishing such positive relationships. Thus, sociability, in addition to morality, appears as an important resource to structure relationships and achieve popularity within the context of friendships.

In contrast, no significant effects of competence were detected. These findings suggest that although competence is a main dimension of social judgment, it is not as impactful as morality is (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014). Thus, it is undoubtedly more critical to infer individuals’ (good or bad) intentions (i.e., information conveyed by their morality) than their ability to implement such intentions (i.e., information that can inferred by individuals’ competence).

The Importance of Friends for Promoting Adolescents’ Self-Perceived Morality

This study also examined whether the quality of relationships influences over time adolescents’ self-perception in terms of morality, competence, and sociability and some evidence of bidirectionality was found. The results indicated that high-quality friendships fostered self-morality over time. Interestingly, this was the only significant effect of contexts on dimensions of self-perception, since family and school contexts had no significant effects. This result is worth some further discussion. As noted in the introduction, most extant studies on adolescent development considered only one (with most of the literature looking at the role of family relationships) or two contexts (e.g., family and friends), with a dearth of studies considering the combined effects of the three contexts (e.g., Kidd et al. 2006; Way and Robinson 2003). Thus, the current study provided novel evidence highlighting that, when all contexts are taken into consideration, friends play a main role, at least for the development of self-morality. Future studies are needed to examine if this applies also to other adolescent outcomes.

The specific association between friendship and adolescent morality documented in this study can be interpreted in light of the changes in the social network that occur in adolescence (Brown and Larson 2009). In this period, friends become increasingly important, being one of the main sources of social support and social identification (e.g., Albarello et al. 2018; De Goede et al. 2009). Friendships become crucial as a privileged setting of self-experimentation whereby individuals redefine their normative system and observe the social consequences of personal and others’ actions (e.g., Caravita et al. 2014; Rubini and Palmonari 2006). Thus, adolescents’ self-perceived morality becomes strongly influenced by friends given the higher possibilities of freely experimenting moral behaviors within this context (Hart and Carlo 2005).

Practical Implications

Overall, this study has important practical implications. The findings underscored that fostering adolescents’ self-perceived morality can be a valuable strategy to improve the quality of their relationships with meaningful others in their daily social contexts. Such knowledge can be used to design and implement interventions aimed at promoting positive youth development. Thus, the effectiveness of targeted interventions, focused on practices aimed at enhancing self-perceived adolescents’ morality, could be tested in future Randomized control trials (RCT), including multiple indicators of relationship quality (e.g., support, mutual affection, open communication) as outcome measures.

Strengths, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Research

This study should be considered in light of both its strengths and limitations, with the latter pointing to future directions of research. First, a major strength was the novelty of the theoretical approach, which stressed the importance of morality, competence, and sociability from the perspective of the self. The present results converge with other lines of inquiry that also point to the primacy of morality. For instance, current findings are consistent with the sociofunctional perspective (Cottrell et al. 2007), indicating that trustworthiness is considered the most desirable characteristic for an ideal person to possess across different social contexts. Additionally, the results are in line with cross-cultural research, emphasizing that individuals consider moral values among the most important guiding principles in their lives (Schwartz 1992). Therefore, different perspectives converge in recognizing morality as a core symbolic dimension. However, if on the one hand the findings show the primacy of morality as a core dimension of self-perception, on the other hand it should be acknowledged that in this study morality was examined considering the perceived correctness of one’s own behavior, honesty, and trustworthiness. Other components of morality (Graham et al. 2011; Lapsley and Carlo 2014), such as issues regarding justice and rights (Killen and Smetana 2008; Richardson et al. 2012), could be addressed in further research.

Second, the effects of dimensions of self-perception across multiple significant life contexts were uncovered. Importantly, in addition to the consistent direct effects documented in this study, future studies are needed to discover potential mechanisms through which self-morality can, over time, affect family, friend, and school relationships. In this respect, the actual behavior implemented by adolescents can be an important mediator. In fact, individuals’ morality can be recognized in honest and reliable behaviors that are positively experienced by significant others, leading to the formation of closer relationships. Thus, future studies can highlight mediational mechanisms through which morality exerts this primary positive influence on several developmental contexts.

Third, from a methodological perspective, the interplay between self-perceived morality, competence, sociability and relationships within multiple contexts was examined for the first time longitudinally, in a large sample of young people. Thus, in addition to within-time associations, it was possible to highlight the effects of self-morality throughout the course of adolescence. The current findings provide an important addition to prior experimental and cross-sectional studies (for a review see Brambilla and Leach 2014), which indicated consistently the primacy of information about morality when perceiving other people and groups. In fact, the study adds to this literature by providing convergent evidence on the primacy of morality adopting a self-perspective approach with a longitudinal design.

Fourth, this study provided robust evidence supporting the importance of differentiating morality and sociability, consistent with the three-dimensional model proposed by Leach and collaborators (Leach et al. 2007; Leach et al. 2017). It was found that morality has a stronger impact than sociability on multiple adolescent contexts. In future studies, it would be worth digging deeper into developmental trajectories of morality and sociability in order to discover whether these dimensions develop differently in adolescence.

In addition to these important strengths, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, in this study self-report measures of morality, competence, and sociability were used. Although this choice is consistent with the adoption of a developmental self-perspective, it would be useful in future studies to deepen this aspect further by considering also other people’s perceptions of these dimensions (i.e., others’ reports). For instance, what does happen when personal and others’ ratings of an adolescent’s morality, competence, and sociability are highly divergent (e.g., an individual’s perception of his/her own high level of morality is not confirmed by another person)? This is an important future direction of research, as divergence in perceptions may be due to various factors, such as differences in empathy (Van Lissa et al. 2014) and can have important psychosocial consequences (e.g., decreasing adjustment; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2007). Thus, it is worth investigating how divergence in rating these dimensions influences interpersonal and intergroup interactions.

In line with these considerations, a second limitation of this study is the fact that the quality of family, friend, and school relationships was also assessed with self-reports. Future studies could test whether current findings are replicated considering evaluations of relationships as reported also by parents, friends, classmates, and teachers.

Conclusion

In this three-wave longitudinal study, a self-perspective approach was adopted, suggesting that in addition to being core dimensions of social judgment (Brambilla and Leach 2014; Leach et al. 2007), morality, competence, and sociability can be conceived as pivotal dimensions of self-evaluation. As such, they represent adaptive resources through which adolescents can structure and shape their social interactions across different contexts. These dimensions were found to have a stronger impact on relationship quality than the other way around. Indeed, the more adolescents perceived themselves as highly moral the more they strengthened their family, friend, and school relationships over time. In addition, sociability also had positive effects, but limited to the friend context, whereas competence did not lead to significant changes in relationships in any social context. Bidirectional effects indicated that high-quality friendships positively influenced adolescents’ morality, demonstrating the importance of friends for adolescent development. Overall, current evidence provides new insights, indicating the primacy of self-perceived morality for enhancing development of adolescents’ nurturing relationships across meaningful contexts. On the other hand, the preeminence role played by friends for augmenting adolescents’ self-perceived morality has been clearly highlighted.

Notes

The datafile and all Mplus input files can be obtained by the first author upon request.

As a preliminary step, longitudinal measurement invariance (Little, 2013; Van de Schoot, Lugtig, and Hox, 2012) for all study variables separately as well as for the total model including all latent variables (with six latent variables— morality, competence, sociability, and family, friend, and school relationships—for each wave; for a total of 18 latent variables) was tested. Thus, the configural (baseline) models were compared with the metric models, in which factor loadings were constrained to be equal across time. Significant differences between the configural and the metric models required that at least two out of these three criteria had to be matched: ΔχSB2 significant at p < .05, ΔCFI ≥ −.010, and ΔRMSEA ≥ .015 (Chen, 2007). The findings indicated the two models did not differ substantially (this was confirmed for each variable separately, as well as for the total model including all variables). Therefore, metric invariance, which is the level of invariance required for examining reliably over time associations between variables (Little, 2013), could be clearly established. The fit of the total metric model was found to be good (χ2 = 6764.740, df = 3720, TLI = .893, CFI = .901, RMSEA = .030 [.029, .032]).

References

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751.

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition: A dual perspective model. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology 50, (195–255). Burlington: Academic Press.

Albarello, F., Crocetti, E., & Rubini, M. (2018). I and us: A longitudinal study on the interplay of personal and social identity in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 689–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0791-4.

Allison, S. T., Messick, D. M., & Goethals, G. R. (1989). On being better but not smarter than others: The Muhammad Ali effect. Social Cognition, 7, 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1989.7.3.275.

Armsden, G., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relation to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939.

Arnett, J. J. (1999). Adolescent storm and stress, Reconsidered. American Psychologist, 54, 317–326.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Benson, P. L., Leffert, N., Scales, P. C., & Blyth, D. A. (1998). Beyond the “village” rhetoric: Creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 2, 138–159. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0203_3.

Brambilla, M., & Leach, C. W. (2014). On the importance of being moral: The distinctive role of morality in social judgment. Social Cognition, 32, 397–408.

Brambilla, M., Sacchi, S., Menegatti, M., & Moscatelli, S. (2016). Honesty and dishonesty don’t move together: Trait content information influences behavioral synchrony. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 40, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-016-0229-9.

Brown, B.B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R.M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.). Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd edn., Vol. 2, pp. 74–103). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2nd edn. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Caravita, S. C., Sijtsema, J. J., Rambaran, J. A., & Gini, G. (2014). Peer influences on moral disengagement in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9953-1.

Carnes, N. C., Lickel, B., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (2015). Shared perceptions: Morality is embedded in social contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214566187.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504.

Christy, A. G., Seto, E., Schlegel, R. J., Vess, M., & Hicks, J. A. (2016). Straying from the righteous path and from ourselves: The interplay between perceptions of morality and self-knowledge. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 1538–1550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216665095.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner.

Cottrell, C. A., Neuberg, S. L., & Li, N. P. (2007). What do people desire in others? A sociofunctional perspective on the importance of different valued characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 208–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.208.

Crocetti, E., Branje, S., Rubini, M., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2017). Identity processes and parent–child and sibling relationships in adolescence: A five-wave multi-informant longitudinal study. Child Development, 88, 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12547.

Crocetti, E., Fermani, A., Pojaghi, B., & Meeus, W. (2011). Identity formation in adolescents from italian, mixed, and migrant families. Child and Youth Care Forum, 40, 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9112-8.

Crocetti, E., Moscatelli, S., Van der Graaff, J., Rubini, M., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2016). The interplay of self-certainty and prosocial development in the transition from late adolescence to emerging adulthood. European Journal of Personality, 30, 594–607. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2084.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0.

De Goede, I., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2009). Developmental changes and gender differences in adolescents’ perceptions of friendships. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1105–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.002.

Elmore, R.F. (2009). Schooling adolescents. In R.M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd edn., Vol. 2, pp. 193–227). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Emler, N., & Reicher, S. (1995). Adolescence and delinquency. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Epley, N., & Dunning, D. (2000). Feeling “holier than thou”: Are self-serving assessments produced by errors in self- or social prediction? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 861–875. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.861.

Erentaitė, R., Vosylis, R., Gabrialavičiūtė, I., & Raižienė, S. (2018). How does school experience relate to adolescent identity formation over time? Cross-lagged associations between school engagement, school burnout and identity processing styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0806-1.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005.

Goodwin, G. P., Piazza, J., & Rozin, P. (2014). Moral character predominates in person perception and evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 148–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034726.

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847.

Hart, D., & Carlo, G. (2005). Moral development in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00094.x.

Harter, S. (1988). The Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self. A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Jordan, A. H., & Monin, B. (2008). From sucker to saint: Moralization in response to self-threat. Psychological Science, 19(8), 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02161.x.

Kidd, S., Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., Davidson, L., King, R. A., & Shahar, G. (2006). The social context of adolescent suicide attempts: Interactive effects of parent, peer, and school social relations. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.386.

Killen, M., & Smetana, J. G. (2008). Moral judgment and moral neuroscience: Intersections, definitions, and issues. Child Development Perspectives, 2, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00033.x.

Landy, J. F., Piazza, J., & Goodwin, G. P. (2016). When It’s bad to be friendly and smart: The desirability of sociability and competence depends on morality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 1272–1290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216655984.

Lapsley, D., & Carlo, G. (2014). Moral development at the crossroads: New trends and possible futures. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035225.

Laursen, B., & Collins, W.A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In R.M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd edn., Vol. 2, pp. 3–42). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Leach, C. W., Bilali, R., & Pagliaro, S. (2015). Groups and morality. In J. Simpson & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA Handbook of personality and social psychology. Interpersonal relationships and group processes 2, (123–149). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Leach, C. W., Carraro, L., Garcia, R. L., & Kang, J. J. (2017). Morality stereotyping as a basis of women’s in-group favoritism: An implicit approach. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20, 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215603462.

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234.

Leary, M. (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 75–111.

Lerner, R.M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.) (2009). Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd edn.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Meeus, W. (2016). Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1969–1993. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000243.

Meeus, W., Oosterwegel, A., & Vollebergh, W. (2002). Parental and peer attachment and identity development in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 25, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0451.

Menegatti, M., & Rubini, M. (2012). From the individual to the group: The enhancement of linguistic bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.856.

Moscatelli, S., Menegatti, M., Albarello, F., Pratto, F., & Rubini, M. (2018). Can we identify with a nation low in morality? The heavy weight of (im)morality in international comparison. Political Psychology. (in press)

Muthén, L. K., Muthén, B. O., (2012). Mplus User’s Guide. 7th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nada-Raja, S., McGee, R., & Stanton, W. (1992). Perceived attachment to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537898.

Richardson, C. B., Mulvey, K. L., & Killen, M. (2012). Extending social domain theory with a process-based account of moral judgments. Human Development, 55, 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335362.

Rubini, M., & Palmonari, A. (2006). Adolescents’ relationships to institutional order. In S. Jackson & L. Goossens (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent development (pp. 264–283). Hove, NY: Psychology Press.

Sameroff, A. J. (Ed.) (2009). The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology 25, (1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Sherif, M., & Sherif, C. (1964). Reference groups exploration into conformity and deviation of adolescents. New York: Harper & Row.

Shortt, A. L., Hutchinson, D. M., Chapman, R., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2007). Family, school, peer and individual influences on early adolescent alcohol use: First-year impact of the resilient families programme. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26, 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230701613817.

Smetana, J. G., Campione-Barr, N., & Metzger, A. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124.

Tarrant, M. (2002). Adolescent peer groups and social identity. Social Development, 11, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00189.

Tsai, K. M., Telzer, E. H., & Fuligni, A. J. (2013). Continuity and discontinuity in perceptions of family relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. Child Development, 84, 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01858.x.

Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740.

Van Lange, P. A. M., & Sedikides, C. (1998). Being more honest but not necessarily more intelligent than others: Generality and explanations for the muhammad ali effect. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 675–680.

Van Lissa, C. J., Hawk, S. T., Branje, S. J. T., Koot, H. M., Van Lier, P. A. C., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2014). Divergence between adolescent and parental perceptions of conflict in relationship to adolescent empathy development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0152-5.

Way, N., & Robinson, M. G. (2003). A longitudinal study of the effects of family, friends, and school experiences on the psychological adjustment of ethnic minority, low-SES adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18, 324–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558403018004001.

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17, 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x.

Wojciszke, B. (2005). Morality and competence in person- and self-perception. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 155–188.

Yoo, H., Feng, X., & Day, R. D. (2013). Adolescents’ empathy and prosocial behavior in the family context: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1858–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9900-6.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Hunter, T. A., & Pronk, R. (2007). A model of behaviors, peer relations and depression: Perceived social acceptance as a mediator and the divergence of perceptions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.3.273.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ Contributions

E.C., S.M., and M.R. conceived of the current study; E.C. performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript; all authors (E.C., S.M., G.K., S.B., R.Z., M.R.) participated in the interpretation of the results and in the drafting of the article; R.Z. is the principal investigator of the POSIDEV project and is responsible for the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Data of the POSIDEV study were used for this study. POSIDEV was funded by the European Social Fund under the Global Grant measure, VP1-3.1-SMM-07-02-008 assigned to Rita Žukauskienė. Silvia Moscatelli and Monica Rubini received support for working on this article by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Research and Education, University and Research FIRB2012 (Protocollo RBFR128CR6_004) assigned to Silvia Moscatelli.

Data Sharing Declaration

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the Mykolas Romeris University (Lithuania) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants (and from their parents, if minors) included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crocetti, E., Moscatelli, S., Kaniušonytė, G. et al. Adolescents’ Self-Perception of Morality, Competence, and Sociability and their Interplay with Quality of Family, Friend, and School Relationships: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. J Youth Adolescence 47, 1743–1754 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0864-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0864-z