Abstract

Although research has examined the bivariate effects of teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement, it remains unclear how these key classroom experiences evolve together, especially in late childhood. This study aims to provide a detailed picture of their transactional relations in late childhood. A sample of 586 children (M age = 9.26 years, 47.1% boys) was followed from fourth to sixth grade. Teacher support and engagement were student-reported and peer acceptance was peer-reported. Autoregressive cross-lagged models revealed unique longitudinal effects of both peer acceptance and teacher support on engagement, and of peer acceptance on teacher support. No reverse effects of engagement on peer acceptance or teacher support were found. The study underscores the importance of examining the relative contribution of several social actors in the classroom. Regarding interventions, improving both peer acceptance and teacher support can increase children’s engagement, and augmenting peer acceptance can help to increase teacher support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bio-ecological models state that development can be conceptualized as a function of bi-directional interactions over time between the child and the multiple settings that surround him or her, and of the relations between these settings (e.g., Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006). Capturing how children influence their environment, how the environment influences children and how different actors in this environment influence one another is therefore key. Engagement, the intensity and emotional quality of children’s involvement in initiating and carrying out learning activities, is an important developmental outcome and predictor for children, with effects on school dropout (Archambault et al. 2009), academic performance (Lam et al. 2012), and psychosocial adjustment (Connell and Wellborn 1991). Teacher support and peer acceptance, two environmental factors fostering positive child development at school, have been shown to predict engagement (e.g., Roorda et al. 2011; Rubin et al. 2015). Vice versa, engagement has also been shown to predict teacher support (Hughes et al. 2008) and peer acceptance (Hughes and Kwok 2006). However, while research has examined the bivariate relations, the transactional relations among the three variables taken together remain unclear. For example, do teacher support and peer acceptance uniquely predict engagement when they are both taken into account? The current study aims to address this gap by examining the transactional, longitudinal relations among engagement, teacher support, and peer acceptance in late childhood (i.e., in 4th, 5th, and 6th Grade), an important transitional period in child development.

Late Childhood as a Transition Period

Late childhood forms an important developmental period in children’s lives. These children are on the verge of adolescence, but still in elementary school. Peers become increasingly important, yet adults can still form influential referents. Research has shown that children’s relationship with teachers becomes less close as they age (Bierman 2011; Jerome et al. 2009), and the importance of peers increases over time (Buhrmester and Furman 1987; Rubin et al. 2015). Adolescence is a period in which peer relationships become increasingly important, and this can come at the cost of students’ engagement in the school context (e.g., LaFontana and Cillessen 2010). However, it remains unclear whether processes that take place in late elementary school are similar to those in early elementary school or start to mimic processes found in adolescence. By examining these processes in late childhood, we can learn more about when certain developmental processes start to change. How large is the relative impact of teachers and peers on child development in this period? Are teacher support and peer acceptance bi-directionally related in late childhood? Answering these questions is crucial for designing interventions aimed at improving children’s engagement in the classroom and can help us understand which classroom social relationships should be targeted at which developmental phase.

Teacher Support and Engagement

According to attachment theory, a supportive context is key for children’s emotional safety and exploration of the environment (Bowlby 1973). More specifically, experiencing a supportive relationship with the teacher can promote students’ emotional security and confidence, and permit them to explore the learning environment and cope better with academic and social demands (Howes et al. 1994; Hughes et al. 2008). Teacher support, i.e., showing appreciation of the child, being attuned to his or her needs, spending time and energy on the child and being available (Leflot et al. 2011), indeed predicts beneficial outcomes for children, such as better academic and socioemotional functioning (Meehan et al. 2003; Wellborn et al. 1992). Research has shown that teacher support is also related to more engagement. A meta-analysis of Roorda and colleagues (2011) showed that in 61 cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (with positive teacher-child interactions as the independent and engagement as the dependent variable) the association between positive teacher-child interactions and engagement was medium to large.

However, the reverse path can also hold. As argued by Hughes and colleagues (2008), it may be easier for teachers to support students who engage in classroom tasks than students who do not follow instructions or do not show interest in class activities. For instance, in a sample of first- to third grade students, Hughes and colleagues (2008) showed that engagement had a positive effect on teacher-student interactions over time. However, research examining this reverse path is limited and especially in late childhood it is unclear whether this link holds. Based on transactional models, it is also likely that teacher support and engagement bi-directionally affect each other, e.g., receiving more teacher support leads to being more engaged, and being engaged in turn elicits more teacher support, etc. (e.g., Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006). However, no study in late childhood has examined the possibility of such a reinforcing loop in the classroom so far.

Peer Acceptance and Engagement

Peer acceptance refers to how much a child is collectively liked by his or hers peers (Rubin et al. 2015) and it is associated with a variety of positive outcomes, such as social competence (Troop-Gordon and Asher 2005) and academic success (Wentzel and Caldwell 1997). When children age, being accepted by peers becomes more important and has an increasing impact on their development (Buhrmester and Furman 1987; Rubin et al. 2015). This raises the question how peer acceptance can impact engagement in late childhood. Scholars have argued that children who are accepted by their peers have higher quality interactions with the class group and better access to peer activities (Ladd et al. 1997). This, in turn, can foster their sense of belonging at school (Connell and Wellborn 1991). Also, being accepted by peers can enable children to engage in joint learning tasks, such as conversations and collaborations (Ladd et al. 1997), thus enhancing their engagement. Research shows, for example, that fifth graders who were accepted by peers in the fall were more engaged in the following spring (Buhs 2005).

Vice versa, one can assume that children who are actively engaged in the classroom, and therefore comply to the age-specific norms for classroom interactions, will be accepted and appreciated more by peers than children who are more passive or who are withdrawn from their learning environment (Rubin et al. 2015). Indeed, a study by Hughes and Kwok (2006) showed that engagement in first grade was positively related to peer acceptance 1 year later. However, longitudinal research, especially in late childhood, examining the effect of engagement on peer acceptance is very scarce. Also, there is a lack of research examining how peer acceptance and engagement bi-directly impact each other over time, e.g., being less accepted by peers results in becoming less engaged and being less engaged, in turn, elicits less acceptance of peers, etc. In addition, studies usually do not examine the effect of peer acceptance on engagement in combination with the effect of teacher support on engagement. However, the reality of daily classroom practice is that both relationships are present at the same time and both can play a role.

Teacher Support, Peer Acceptance and Engagement

Not only can teacher support and peer acceptance impact child engagement, they can also impact one another. Research in early elementary school has shown that when children receive more support from their teacher, they tend to be better accepted by their peers (Hughes et al. 2006). However, there is increasing evidence that in middle and late childhood, peer effects on teachers become even more pronounced than teacher effects on peers (e.g., Leflot et al. 2011). This may indicate that, as students grow older and the role of the peer group increases, they turn less to their teachers a source of social information. As an explanation for these positive effects of peer acceptance on teacher support (and vice versa) researchers have pointed to the potential mediating role of engagement (De Laet et al. 2014; Hughes and Kwok 2006; Leflot et al. 2011). That is, when children feel appreciated and accepted by their classroom peers, this will enable them to engage more fully in classroom learning tasks, which will elicit positive reactions and support from their teachers. Reversely, it has also been argued that the positive effect of teacher support on peer acceptance can be explained by the fact that teacher support enhances children’s engagement. However, no study in late childhood has examined these explanatory models yet. To fill this gap, the current research uses one comprehensive, longitudinal model, which allows to examine the intervening role of engagement in the relation between peer acceptance and teacher support. Also, it allows to address questions such as: does the effect of teacher support on engagement hold, when student acceptance is taken into account, i.e., do they both have unique effects on engagement or is there a more general effect of classroom social relationships?

Overall, there is a gap in literature regarding the longitudinal effects that these three variables may have on each other. Three notable exceptions are studies of Hughes and Kwok (2006), Wang and Eccles (2012), and Engels and colleagues (2016). First, the two-wave longitudinal study by Hughes and Kwok (2006) among at-risk children in first and second grade examined whether engagement mediates the effect of teacher support on peer acceptance. They found that engagement fully mediated this effect in early elementary school. However, only the path from teacher support to peer acceptance through engagement was examined, and not the reverse path. Also, mediator and outcome were measured at the same time. Second, Wang and Eccles (2012) studied the effect of perceived teacher and peer support on engagement in adolescence in a three-wave longitudinal study. They found that both types of support had an effect on engagement of adolescents over time. However, the potential reverse effect of engagement on perceived teacher and peer support was not examined. Finally, in a three-wave longitudinal study in secondary school, Engels and colleagues (2016) examined the transactional effects of engagement, peer likability, and positive teacher-student relationships in adolescence. They found that peer likability and positive teacher-student relationships both had a unique effect on engagement, but that these classroom-based relationships were not interrelated over time. No effects of engagement on peer likeability and teacher-student relationships were found. The authors concluded that, at least in adolescence, peers and teachers seem to constitute difference sources of influence, and play independent role in adolescents’ engagement. It also appears that the ‘peer world’ and the ‘teacher’ world are less interconnected in adolescence. It is unclear, however, whether this conclusion holds only for adolescents, in secondary school.

Overall, the three studies used samples from developmentally different periods, making it unclear whether the effects can be transferred to different age periods, such as late childhood. Given the developmental changes that occur during childhood and adolescence, it is important to examine the generalizability of findings from different developmental periods to a late childhood sample.

Gender Differences

The socio-emotional development of boys and girls, in general, differs on important aspects. Studies have shown that the level of engagement can be different between boys and girls, with boys generally showing lower engagement levels than girls (e.g., Lam et al. 2012). Further, girls generally encounter more acceptance (Crockett et al. 1984), closeness, and security in their relationships with peers (Bukowski et al. 1994). Also, there is evidence that boys and girls have different relationships with their teachers, for example, boys have lower average levels of teacher support (e.g., Hamre and Pianta 2001). It is suggested that this could be due to girls seeking more nurturing relationships with teachers and peers (Spilt et al. 2012) and boys presenting themselves as more autonomous and assertive, leading to more teacher and peer support for girls than for boys (Ewing and Taylor 2009).

Not only do girls and boys have different social relationships, the effect of these relationships on their engagement may also differ. On the one hand, the gender role socialization perspective proposes that close relationships may be more beneficial for girls, because closeness is consistent with the greater intimacy and affiliation in social relationships that are expected from girls (Maccoby 1998). On the other hand, the academic risk perspective expects that classroom social relationships are more influential for boys’ engagement because boys have a greater risk of school failure (Hamre and Pianta 2001).

Current Study

Despite the growing literature regarding teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement, few studies have examined how these key classroom experiences evolve together, especially in late childhood. This study extends prior research by investigating how these three variables mutually impact one another over time, using a three-wave longitudinal design during the understudied period of late childhood. Five research questions were addressed. First, we examined whether teacher support and peer acceptance had additive, unique effects on engagement. Based on previous research in adolescence (Engels et al. 2016; Wang and Eccles 2012), we expected that both classroom social relationships would contribute independently to engagement. Second, we tested whether engagement would also have a reverse effect on teacher support and peer acceptance. Although the possibility of bi-directional associations between engagement and classroom social relationships has been proposed by several authors, few studies have examined this possibility in a cross-lagged longitudinal design. Third, we aimed to examine whether teacher support and peer acceptance predict each other in late childhood when engagement is controlled for. In early childhood, teachers and peers can have an effect on each other (e.g., Hughes and Kwok 2006; Leflot et al. 2011), whereas in adolescence the links among these social actors seem to diminish (e.g. Engels et al. 2016). We hypothesized that in late childhood teacher support and peer acceptance would still have an impact on each other. Fourth, we aimed at clarifying the mechanisms through which both classroom social relationships would affect each other over time, specifically by testing the mediating role of engagement. Finally, we examined the possibility of gender differences in in the longitudinal relations between teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement. Based on the gender role socialization perspective, we would expect the effects of social relationships to be larger for girls than for boys (Maccoby 1998). However, the alternative hypothesis of the academic risk perspective could also hold to be true (Hamre and Pianta 2001). Because we measured all three variables at all thee waves, we were also able to control for previous, concurrent, and subsequent levels of the variables. This allowed us to provide a transactional and comprehensive picture of the interactions that take place inside the classroom.

Methods

Participants

The data were collected in a sample of 736 children from 32 classrooms in 24 schools, that was followed annually from fourth to sixth grade. On average, 79% of the children per classroom participated. All schools were located in the Flemish community of Belgium. In Flanders, elementary school is compulsory and has six grades, with students aged between six and 12 years (i.e., Grade 1–6). Afterwards, children go to secondary school, which also comprises six grades (i.e., Grade 7–12). In elementary school children follow all classes with the same classroom peers and they have, in general, one teacher every school year. Active parental permission was requested each year. The Institutional Review Board of KU Leuven approved the procedures for this study. Questionnaire data on two out of three waves were missing for 150 children, mainly because of missing parental permission and changing schools. These children (further called ‘dropout group’) were excluded from the study, resulting in a random three-wave longitudinal sample of 586 children who participated in two or three waves. The dropout group did not differ significantly from our study sample regarding gender or teacher support. However, the children in the dropout group were older, t(435) = 2.69, p < .01, d = .26, had lower levels of peer acceptance, t(425) = −4.00, p < .001, d = 0.39, and lower engagement, t(431) = −2.82, p < .01, d = .27. These effect sizes can be considered small to medium (Cohen 1988).

The 586 children in our study had a mean age of 9.26 years (SD = 0.52 years) and 47.1% were boys. Most parents (64%) provided background information. The majority of the children (87%) had at least one parent with the Belgian nationality. Of the participating children, 85% lived in intact families, 10% in single-parent families, and 4% in stepfamilies. Most parents completed higher education (67% of the mothers and 56% of the fathers). The other parents either finished (some years of) high school (30% of the mothers and 31% of the fathers) or completed elementary school (7 mothers or 0.02% and 8 fathers or 0.02%). As is usual in the Flemish educational system, the children had a different teacher in each grade. Most teachers were female (85%, M age = 38.24).

Design of the Data Collection

Data collections occurred at three points in time: in Spring of fourth, fifth, and sixth grade. Children reported on the support they received from their teacher and their own engagement at each wave. A sociometric rating procedure for peer acceptance was also conducted annually. All data were gathered in the classroom during regular school hours under supervision of graduate students in psychology.

Measures

Teacher support

Teacher support was assessed with the global Support Scale of the Child Relationship Questionnaire-Revised (Hughes 2011; Hughes and Villarreal 2008). The items of the questionnaire were selected from Furman and Buhrmester’s (1985) Network of Relationships Inventory. Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity has been reported (e.g., Li et al. 2012). Children were asked to respond to the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely does not apply) to 5 (definitively applies). The global Social Support Scale consists of 16 items measuring six forms of social support (i.e., affection, admiration, intimacy, satisfaction, nurturance, and reliable alliance). One item was dropped because of its low item-total correlation (De Laet et al. 2014; Field 2005). So, the final Social Support Scale consisted of 15 items (e.g., “How much does your teacher really care about you?”, “How much does your teacher treat you like you are good at many things?”) and Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .90 to .92.

Peer acceptance

Peer acceptance was measured using peer ratings (Putallaz 1983). Each child rated how much he or she liked to play with each classmate on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (dislike very much) to 5 (like very much). Hereby we used a Round-robin design: every participant was both a nominee and a nominator. The ratings received from classmates were then summed up and averaged within the classroom to obtain an individual child’s level of peer acceptance within the class group. Acceptance scores in our sample ranged from 1.00 to 5.00. Rubin et al. (2006) report that this rating procedure provides a detailed and valid measure of peer acceptance. It allows children to evaluate each member of their peer group and allows them to report their degree of liking and disliking.

Engagement

Engagement was assessed with the Dutch School Questionnaire (SchoolVragenLijst; Smits and Vorst 1990), which has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability (Evers et al. 2013). In addition, Flemish norms available for this scale, which is useful for providing feedback to participating schools. For this study, we used the motivation scale that comprises three dimensions of engagement, i.e., on-task behavior, homework attitude, and attention in the classroom. Second-order confirmatory factor analysis in each wave showed that the model in which all items loaded on the three subscales/first-order factors (on-task behavior, homework attitude, and attention in the classroom), and the subscales loaded on the second-order factor “Engagement”, fit the data adequately (CFI = .89 to .92; SRMR = .06 to .05; RMSEA = .05 to .05), which justified the use of the Engagement scale in our analyses (see also De Laet et al. 2015). This scale consists of 19 items (e.g., “I want to learn many things at school”) and Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .77 to. 81.

Data-analysis

The bi-directional longitudinal links among teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement were tested in autoregressive cross-lagged models with three waves (Jöreskog 1970). Autoregressive, within-time, and cross-lagged paths were modelled to provide a detailed picture of the links among the three variables, while taking previous and concurrent levels of all variables into account. The autoregressive paths represent the regression of the variables on their previous value and model the cross-year continuity within the variables. The within-time paths display concurrent associations between the variables at each wave. Moreover, the cross-lagged paths show the bi-directional paths between teacher support and engagement, between engagement and peer acceptance, and between teacher support and peer acceptance, respectively. The potential mediating effect of engagement was also tested in this model. To examine gender differences, we estimated a constrained model in which the paths were set to be equal across gender and an unconstrained model in which the paths were allowed to vary across gender. Then we conducted an omnibus multigroup analysis to compare these two models.

We controlled for the clustering of students in classrooms, using the ‘complex analysis’ feature in Mplus, which adjusts the standard errors of the estimated path coefficients (Williams 2000). Further, missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) algorithm recommended by Jelicic et al. (2009). The fit of each model was evaluated with the robust Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square statistic (S–Bχ²; Satorra and Bentler 2001), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger 1990), and the average comparative fit index (CFI; Hu and Bentler 1999). Generally, S–Bχ² values as small as possible are considered indicative of good fit (Kline2005). CFI values ≥ .90 are considered indicative of acceptable fit and CFI values ≥ .95 of good fit. SRMR values ≤.08 are indicative of good model fit. RMSEA values ≤.06 are considered indicative of good fit, ≤.08 of fair fit, and between .08 and .10 of mediocre fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). To compare nested models, we used change in model fit with the ∆S–Bχ² test (Satorra and Bentler 2001). When p < .05, the model fit of the constrained model is considered significantly worse. When p > .05, there is no significant difference in model fit between the two nested models, and therefore the constrained, i.e., the more parsimonious model, is preferable. Fit comparisons for the multigroup analysis were also made by means of the ∆S–Bχ² test (Satorra and Bentler 2001). The descriptive statistics were calculated in SPSS 23 and Mplus version 7.4 was used for the main analyses (Muthén and Muthén 2015).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations of teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement at the three waves are reported in Table 1, for the overall sample and for boys and girls separately. Girls reported significantly higher teacher support and engagement in Grade 4 than boys, t(417) = −2.26, p < .05, d = .22 and t(413) = −2.50, p < .05, d = .25, respectively. These levels did not differ significantly in the other grades. Girls were also significantly more accepted by their peers in Grade 5 and 6 than boys, t(514.08) = −4.59, p < .001., d = .39 and t(489.69) = −2.40, p < .05., d = .21, respectively. There were no significant gender differences in the level of peer acceptance in Grade 4. The effect sizes can be considered small (Cohen 1988). The Pearson correlation matrix for the three variables at the three waves is reported in Table 2. All three variables have significant cross-year correlations with their subsequent value, i.e., they remain stable over time. Regarding within-time correlations, the three variables were all significantly intercorrelated in Grade 4 and 6. In Grade 5 engagement and teacher support were significantly correlated. Concerning cross-year correlations between variables, teacher support was significantly correlated with subsequent engagement, but not with subsequent peer acceptance. Peer acceptance was significantly correlated with subsequent teacher support and engagement. Engagement was significantly correlated with subsequent teacher support, but not with subsequent peer acceptance.

General Cross-lagged Model

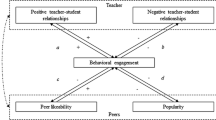

We estimated a model with autoregressive, within-time, and cross-lagged paths for our study variables (i.e., teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement) across the three waves. This model had adequate fit, S–Bχ² = 32.027, p < .001; RMSEA = .081; CFI = .971, and SRMR = .030. Then, we restricted the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths to be equal across time, i.e., the paths from Wave 1 to Wave 2 had to be equal to the paths from Wave 2 to Wave 3. This more parsimonious model had a good fit, S–Bχ² = 45.690, p < .001; RMSEA = .058; CFI = .965, and SRMR = .046. The ∆S–Bχ² test showed that the parsimonious model was not significantly worse (∆S–Bχ² (9) = 14.35, p = 0.110) than the unrestricted model and therefore we continued with the parsimonious model. Figure 1 shows all the significant paths in this model. Teacher support, engagement, and peer acceptance were all stable across time. Regarding within-time associations, teacher support and engagement were significantly associated at each wave and engagement and peer acceptance were significantly associated in Grade 4 and 6. Also, teacher support and peer acceptance were significantly associated in Grade 4. Concerning cross-lagged paths, the model showed several significant paths, beyond stability paths and within-time associations. First, peer acceptance significantly predicted engagement as well as teacher support in the next grade. Second, teacher support also significantly predicted engagement in the next grade, but not peer acceptance. Engagement did not significantly predict teacher support or peer acceptance.

No mediation effects of engagement were found. The indirect path of support through engagement on acceptance was <0.001, ns, and the indirect path of acceptance through engagement on support 0.004, ns.

Finally, multigroup analyses indicated that the more parsimonious model, where the paths were set equal for boys and girls, was not significantly worse that the unrestricted model, where they could vary; ∆S–Bχ² (21) = −39.81, p = ns. So, the analyses suggest that there were no significant gender differences.

To conclude, both peer acceptance and teacher support contributed positively and independently to subsequent levels of engagement. No reverse effects were found from child engagement to subsequent levels of peer acceptance or teacher support. We only found a robust effect of peer acceptance on teacher support over time and no reverse effect. Engagement did not mediate this effect. Finally, we found no evidence that there are significant gender differences in the links among these variables.

Discussion

This study examined the transactional relations among teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement in late childhood. Although previous research has shown the importance of teacher support (Roorda et al. 2011) and peer acceptance (Rubin et al. 2015) for the development of engagement and how child engagement can impact teacher support (Hughes et al. 2008) and peer acceptance (Hughes and Kwok 2006), it remained unclear how these classroom experiences evolve together. More specifically, there was a lack of research examining the transactional relationships among teachers, peers and engagement, the relative importance of the variables, and possible gender differences. Especially in late childhood, an important developmental period when children are on the verge of adolescence and social relationships in the school context begin to shift, it is unclear how these variables bi-directionally affect each other. To address these questions, we conducted a three-wave longitudinal study in fourth, fifth, and sixth grade. Based on our cross-lagged analyses, we can conclude that in late childhood both peer acceptance and teacher support have unique longitudinal effects on the development of engagement and that peer acceptance also has an effect on the support children perceive from their teacher. The specific results regarding our main research questions will be discussed below.

First, teacher support and peer acceptance uniquely predict engagement when they are both taken into account. This effect is robust over time and is found while controlling for all previous and concurrent levels of the variables. Previous research has found evidence for the effects of teacher support (Roorda et al. 2011) and peer acceptance separately (Buhs 2005). However, in real classrooms these processes take place together and our study shows that both social relationships contribute independently to how engaged a child is in the classroom. This is also in accordance to the scarce research that examined the effects of both social relationships in adolescent samples and confirms their independent effects in late childhood when children are still in elementary school (Engels et al. 2016; Wang and Eccles 2012). Our findings underscore the importance of forming a supportive teacher-child relationship for fostering children’s emotional security and confidence and to permit children to engage actively with their environment (Howes et al. 1994; Hughes et al. 2008). In addition to teacher support, being accepted by peers can foster children’s sense of belonging at school and, in turn, their engagement (Connell and Wellborn 1991).

Second, we found no longitudinal effects of engagement on teacher support or peer acceptance when previous and concurrent levels of all variables were controlled for. Despite the fact that longitudinal research is limited, the scarce existing research in early childhood examining the effect of engagement on teacher support (Hughes et al. 2008) or peer acceptance (Hughes and Kwok 2006) did find an effect. Nonetheless, our study differed on several aspects from this research. First, our analyses were more strict and took both previous and concurrent levels of all three variables into account, providing a more detailed picture of classroom processes. Second, our sample was older: perhaps for younger children active engagement is more predictive of teacher support and peer acceptance, whereas for older children different processes play a role. For example, for younger children it could be more important to make a good and engaged ‘impression’, whereas for older children, relationships with peers, which are already more established, have a greater influence on subsequent peer and teacher relationships. These explanations for the different findings are in accordance with findings from a study in adolescence (Engels et al. 2016) which also found no effect of engagement on teacher or peer relationships. The fact that similar findings are found despite the use of different methods supports the notion that, at least from late childhood on, social relationships mainly influence engagement and not the other way around.

Although researchers often assume that the effects between social relations and engagement are bi-directional (e.g., Leflot et al. 2011), the evidence for this assumption is limited and previous study designs often did not allow to test this. The present study did permit us to examine possible transactional links, and showed only evidence for uni-directional links from social relationships to engagement. This underscores the importance of the social context for development in school, even across school years.

Third, our analyses showed that peer acceptance predicts teacher support when engagement levels are controlled for in late childhood. This effect has been found in younger samples (e.g., Leflot et al. 2011), but not in adolescent samples (e.g., Engels et al. 2016). It seems that in late childhood the ‘peer world’ and the ‘teacher world’ are still interconnected, whereas these worlds are more separated when children enter adolescence. Moreover, this effect was found while controlling for engagement. In our study the reverse path, teacher support predicting peer acceptance, was not found. This is in contrast with findings from early childhood samples (e.g., Hughes and Kwok 2006; Hughes et al. 2006), which may suggest that, as students grow older, they turn less to their teachers a source of social information about peers.

Thus, it appears that in elementary school relationships with teachers and peers are interconnected, with an increased importance of the effect of peers on teachers when children age (e.g., Bierman 2011; Buhrmester and Furman 1987). In adolescence, there seem to be less connections between these two ‘social worlds’ (e.g., Engels et al. 2016). Perhaps teachers in secondary school are less knowledgeable of peer interactions because these happen more outside of the classroom. Another possible explanation is that teachers spend less time with their students, because students have different teachers for different subjects, and are therefore less informed.

Fourth, we tested the hypothesis that engagement mediates between peer acceptance and teacher support, which was suggested previously by several researchers (e.g., Hughes and Chen 2011; Leflot et al. 2011). For example, they reasoned that children who are accepted by peers may evoke more teacher support because they are more likely to be engaged in the classroom. Our findings, however, do not support this explanatory model, as no mediating effect of engagement was found in the relation between peer acceptance and teacher support. It seems that this engagement is not the ‘missing link’ between peers and teachers, as is often hypothesized. As such, our findings call for more research on the explanatory mechanisms. A possible explanation is that teachers form a cognitive schema of a child’s peer status (‘this is a well-liked child’) and act consistently with this belief (Mercer and DeRosier 2008), further research could examine this possibility. More research is also needed to examine whether our findings are specific to late childhood or that they are more broadly applicable.

Fifth, our analyses suggests that there are no significant gender differences in the longitudinal relations between teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement. We formulated two alternative hypotheses: either that social relationships and engagement would be more strongly related for girls, based on the gender role socialization perspective (Maccoby 1998), or that they would be more strongly linked for boys, given the academic risk perspective (Hamre and Pianta 2001). However, our analyses supported neither of these hypotheses. It seems that there are no meaningful gender differences in the relations between teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement. So, social classroom relationships are equally important for both sexes. This underscores the importance for teachers and peers to also form close, supportive relationships with boys in the higher grades of elementary school.

Our study has several strengths, such as its longitudinal design, the large sample, and the inclusion of three key variables at all three waves. However, there are also some limitations to take into account. First, even though we used two informants, peers and child, we did not included teacher-reports. Further research could aim to include both child and teacher reports. Second, most children in the sample had parents with the Belgian nationality who were highly educated. Given that processes may differ in more heterogeneous samples, it would be useful to replicate our findings in a more diverse sample (e.g., Gallagher et al. 2013).

Finally, the present study has implications for both research and practice. It expands the existing literature regarding social relationships and engagement in the classroom, by examining the transactional relations among the three variables in late childhood. Previous research has often overlooked this important developmental period. Our study shows that relations between these variables are already different from those in early elementary school, but not yet completely similar to findings in adolescence either. Further research should examine this important transitional period to a deeper extend, to better understand when and how processes between social actors in the school context start to change. Our results underscore the importance of looking beyond the bivariate effects of two variables and examining how several variables mutually affect each other over time. This also allows to examine the relative importance of different actors in the classroom for child development and enables us to examine the processes that go on in the classroom in a more detailed way. This can be valuable for designing interventions. When aiming to improve child engagement, it is valuable to improve both teacher support and peer acceptance, given that they have additive effects. By focusing on more than one social interaction partner, the effectiveness of engagement interventions will probably improve. Also, this provides more options for helping disengaged children. For example, if the support of the teacher is already optimal and a child is still disengaged, practitioners can work on peer acceptance in the classroom to achieve an additional positive influence on engagement levels. Further, the effects of social relationships on engagement hold both for boys and girls. In addition, if teacher support needs to be increased, our findings suggest that, at least in late childhood, interventions can also focus on peer acceptance in the class group, as a way to improve teacher support.

Conclusion

Our three-wave longitudinal study in fourth, fifth, and sixth grade enabled us to investigate important transactional links in the classroom context. We can conclude that child engagement in late childhood is affected both by peer acceptance and teacher support, which is in accordance with the scarce research in adolescence (Wang and Eccles 2012). Contrary to expectations, reverse effects from child engagement to peer acceptance and teacher support were not found, thus underlining the key antecedent role of classroom social relationships in shaping how engaged children are. In addition, being more accepted by peers had a positive effect on subsequent teacher support, whereas teacher support did not affect subsequent peer acceptance. Thus, it seems that in late childhood relationships with peers have an effect on relationships with teachers, but not the other way around. Research in early elementary school found evidence for interconnections in both directions between peers (Leflot et al. 2011) and teachers (e.g., Hughes and Kwok 2006), whereas studies in adolescence show no interconnections (e.g., Engels et al. 2016). The results of our study can be considered to be in between: the “peer world” and the “teacher world” are less intertwined than in early elementary school, however, they are not yet “separate social worlds”. Researchers have hypothesized that child engagement could be a potential mediation mechanism between peer acceptance and teacher support (e.g., Leflot et al. 2011), however, we found no supporting evidence. Further research can examine other possible exploratory mechanisms, to deepen our understanding of how social relationships in the classroom can form each other. Finally, our study showed that the relations between these three key variables were equal for both and girls, so boys as well as girls need supportive social relationships in late childhood.

Overall, our study examined five main research questions with regard to the importance of teacher support, peer acceptance and engagement in late childhood. It revealed how some processes in late childhood mimic those in early elementary school years, whereas others are already similar to processes found in adolescence. In addition, our study has important implications for interventions aimed at increasing engagement, showing that relationships with both social interactions partners in the classroom, peers and teacher, have additive effects.

References

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J.-S., & Pagani, L. (2009). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 651–670.

Bierman, K. L. (2011). The promise and potential of studying the “invisible hand” of teacher influence on peer relations and student outcomes: A commentary. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.004.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation, anxiety and anger (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). New York, NY: Wiley.

Buhs, E. S. (2005). Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.09.001.

Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471–484.

Camarena, P. M., Sarigiani, P. A., & Peterson, A. C. (1990). Genderspecific pathways to intimacy in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 19, 19–32.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558 https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In M. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Development: Vol. 23. Self-processes in development (pp. 43–77). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Crockett, L., Losoff, M., & Peterson, A. (1984). Perceptions of the peer group and friendship in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 4, 155–181.

De Laet, S., Colpin, H., Vervoort, E., Doumen, S., Van Leeuwen, K., Goossens, L., & Verschueren, K. (2015). Developmental trajectories of children’s behavioral engagement in late elementary school: Both teachers and peers matter. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1292–1306. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039478.

De Laet, S., Doumen, S., Vervoort, E., Colpin, H., Van Leeuwen, K., Goossens, L., & Verschueren, K. (2014). Transactional links between teacher–child relationship quality and perceived versus sociometric popularity: A three‐wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 85, 1647–1662.

Engels, M. C., Colpin, H., Van Leeuwen, K., Bijttebier, P., Van Den Noortgate, W., Claes, S. et al. (2016). Behavioral engagement, peer status, and teacher–student relationships in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0414-5.

Evers, A., Egberink, I. J. L., Braak, M. S. L., Frima, R. M., Vermeulen, C. S. M., & van Vliet-Mulder, J. C. (2013). COTAN Documentatie [COTAN Documentation]. Amsterdam: Boom test uitgevers.

Ewing, A. R., & Taylor, A. R. (2009). The role of child gender and ethnicity in teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behavioral adjustment in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 92–105.

Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016.

Gallagher, K. C., Kainz, K., Vernon-Feagans, L., & White, K. M. (2013). Development of student–teacher relationships in rural early elementary classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.03.002.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher– child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72, 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301.

Howes, C., Hamilton, C. E., & Matheson, C. C. (1994). Children’s relationships with peers: Differential associations with aspects of the teacher-child relationship. Child Development, 65, 253–263.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, J. N. (2011). Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perceptions of teacher–student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. The Elementary School Journal, 112, 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/660686.

Hughes, J. N., & Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student–teacher and student-peer relatedness: Effects on academic self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.03.005.

Hughes, J. N., & Kwok, O. M. (2006). Classroom engagement mediates the effect of teacher–student support on elementary students’ peer acceptance: A prospective analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 465–480.

Hughes, J. N., Luo, W., Kwok, O. M., & Loyd, L. K. (2008). Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 1–14.

Hughes, J. N., & Villarreal, V. (2008). Teacher, student, and peer reports of teacher-student relationship support: Joint and unique contributions to academic and social adjustment. Paper presented at the 30th ISPA International Conference, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Hughes, J. N., Zhang, D., & Hill, C. R. (2006). Peer assessments of normative and individual teacher–student support predict social acceptance and engagement among low-achieving children. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.10.002.

Jelicic, H., Phelps, E., & Lerner, R. A. (2009). Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies: The persistence of bad practices in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1195–1199. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015665.

Jerome, E., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Teacher–child relationships from kindergarten to sixth grade: Early childhood predictors of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness. Social Development, 18, 915–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00508.x.

Jöreskog, K. G. (1970). A general method for analysis of covariance structures. Biometrika, 57, 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/57.2.239.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1997). Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Destinct relation systems that contribute uniquely to children's school adjustment? Child Development, 68, 1181–1197.

LaFontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2010). Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Social Development, 19, 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x.

Lam, S.-F., Jimerson, S., Kikas, E., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Nelson, B., et al. (2012). Do girls and boys perceive themselves as equally engaged in school? The results of an international study from 12 countries. Journal of School Psychology, 50, 77–94.

Leflot, G., Van Lier, P. A. C., Verschueren, K., Onghena, P., & Colpin, H. (2011). Transactional associations among teacher support, peer social preference, and child externalizing behavior: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.533409.

Li, Y., Hughes, J. N., Kwok, O., & Hsu, H. (2012). Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity of child, teacher, and peer reports of teacher-student support. Psychological Assessment, 24, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024481.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Meehan, B. T., Hughes, J. N., & Cavell, T. A. (2003). Teacher–student relationships as compensatory resources for aggressive children. Child Development, 74, 1145–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00598.

Mercer, S. H., & DeRosier, M. E. (2008). Teacher preference, peer rejection, and student aggression: A prospective study of transactional influence and independent contributions to emotional adjustment and grades. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 661–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2008.06.006.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Putallaz, M. (1983). Predicting children’s sociometric status from their behavior. Child Development, 54, 1417–1426. 10.2307/1129804.

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement a meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81, 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Children in Peer Groups. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 4 (pp. 1–48). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy405.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, (Ed.), W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 571–645). New York, NY: Wiley.

Sabol, T. J., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher–child relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 14, 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672262.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192.

Smits, J. A. E., & Vorst, H. C. M. (1990). Schoolvragenlijst voor basisonderwijs en voortgezet onderwijs: SVL. Handleiding voor gebruikers. Nijmegen: Berkhout. [School questionnaire for elementary and secondary school. User’s manual].

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M., & Jak, S. (2012). Are boys better off with male and girls with female teachers? A multilevel investigation of measurement invariance and gender match in teacher–student relationship quality. Journal of School Psychology, 50, 363–378.

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4.

Troop-Gordon, W., & Asher, S. R. (2005). Modifications in children’s goals when encountering obstacles to conflict resolution. Child Development, 76, 568–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00864.x.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83, 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x.

Wellborn, J., Connell, J., Skinner, E., & Pierson, L. (1992). Teacher as social context (TASC). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester.

Wentzel, K. R., & Caldwell, K. (1997). Friendships, peer acceptance, and group membership: Relations to academic achievement in middle school. Child Development, 68, 1198–1209.

Williams, R. L. (2000). A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics, 56, 645–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00645.x.

Authors’ Contributions

T.W. conceived the study, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; H.C. conceived the study and helped to draft the manuscript; S.D.L. assisted with the interpretation of the data and gave feedback on the manuscript; M.E. assisted with the critical reading and gave feedback on the manuscript; K.V. conceived the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by two grants from the Research Foundation—Flanders (1S13917N, G.0728.14N).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study is in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards and was approved by the ethical review board of the faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium.

Informed Consent

Active parental informed consent was obtained annually for all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weyns, T., Colpin, H., De Laet, S. et al. Teacher Support, Peer Acceptance, and Engagement in the Classroom: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study in Late Childhood. J Youth Adolescence 47, 1139–1150 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0774-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0774-5