Abstract

Youth development programs represent key tools in the work of youth-serving practitioners and researchers who strive to promote character development and other attributes of youth thriving, particularly among youth who may confront structural and social challenges related to their racial, ethnic, and/or economic backgrounds. This article conducts secondary analyses of two previously reported studies of a relatively recent innovation in Boy Scouts of America (BSA) developed for youth from low-income communities, Scoutreach. Our goal is to provide descriptive and admittedly preliminary exploratory information about whether these data sets—one involving a sample of 266 youth of color from socioeconomically impoverished communities in Philadelphia (M age = 10.54 years, SD = 1.58 years) and the other involving a pilot investigation of 32 youth of color from similar socioeconomic backgrounds in Boston (M age = 9.97 years, SD = 2.46 years)—provide evidence for a link between program participation and a key indicator of positive development; that is, character development. Across the two data sets, quantitative and qualitative evidence suggested the presence of character development among Scoutreach participants. Limitations of both studies are discussed and implications for future longitudinal research are presented. We suggest that future longitudinal research should test the hypothesis that emotional engagement is key to creating the conditions wherein Scoutreach participation is linked to character development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth development programs represent key ecological contexts for the development of youth and adolescents (Vandell et al. 2015). However, youth with structural and social barriers to accessing youth development programs are both underrepresented in program participation and are understudied about their development in general (Spencer and Spencer 2014). Whether youth from disadvantaged backgrounds can benefit from participating in youth development programs and, if so, through which processes, constitute a focal question of youth-serving practitioners and researchers. This article conducts secondary analyses of two previously reported studies. Our goal is to provide descriptive and preliminary exploratory data in a “hypothesis seeking” mode (Cattell 1966); that is, we assess whether a relatively recent innovation in youth programming of a major youth-serving organization—Boy Scouts of America (BSA)—is linked to character development among socioeconomically, racially, and ethnically diverse youth. We explore if data from two initial investigations of this BSA initiative, Scoutreach, are associated with this key indicator of positive development among boys of color from low-income communities in two instances of BSA programs, one in Philadelphia and the other in Boston. Although admittedly preliminary, and an endeavor aimed at generating hypotheses for testing in future, larger-scale research, we believe it is timely and useful to explore these existing data sets for even suggestive evidence of character development among youth participating in the program.

In the U.S. and, as well, throughout the world, disparities in opportunities for lives marked by adaptive, healthy, or positive development vary in relation to the interrelated variables of race, poverty or socioeconomic status (SES), and ethnicity (e.g., Duncan et al. 2015; Guerra and Olenik 2013; McLoyd et al. 2015; Sampson 2016; Sampson and Winter 2016). Economically disadvantaged youth and youth of color suffer from pernicious implications of these variables. Simply, this constellation of variables combines to lessen the probability of thriving or positive youth development (PYD), in general, and of specific instances of such development. For instance, Lerner et al. (2015) defined PYD as involving five attributes: competence, confidence, connection, caring, and character. In writing about one of these “Five Cs,” character—or attributes associated with having a moral or ethical compass, or the proclivity to “do the right thing” at the right time and in the right place (i.e., to manifest the Aristotelian virtue of phronesis; Lerner and Callina 2014; Nucci 2017)—Sampson (2016) notes:

Consider, too, the children who were exposed to severe concentrated disadvantage, racial segregation, and lead poisoning during critical early years of development, in turn shaping cognition, self-control, and expectations for longevity. Or consider the children growing up today who, while experiencing lower violence and thereby improved conditions for learning and character development, are still aging into a regime of strict criminal-justice control and increasing income inequality. It is not just the ability to control oneself but the desire: we may not like to admit it, but in some contexts the incentives for choosing today are sometimes more rational than choosing a tomorrow that may never come, or will do so in highly inequitable ways. Character is therefore more than a skill, and in the strong sense, not an individual characteristic—it is deeply rooted in the structural conditions of existence. (p. 509).

Although all the Cs of PYD suggested by Lerner et al. (2015) continue to be studied, character has become a construct of increasing scientific and societal interest across the last decade (e.g., Ettekal et al. 2015; Lerner et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2016), perhaps because of the issues of social inequality noted by Sampson (2016). For instance, in 2016, there was the first-ever meeting of the United States National Academies of Science on the topic of character development. This meeting was specifically organized to facilitate discussion among researchers, who were studying the role of community-based, youth development programs in promoting character development, and practitioners, who were implementing such programs (Lerner et al., in preparation).

It was important to include both researchers of character development and practitioners who implement youth development programs because these programs are increasingly being used as tools for eliminating (or, at least, reducing) the negative and socially unjust disparities in instances of PYD that are often associated with the constellation of race, poverty or SES, and ethnicity variables noted earlier. These researchers and practitioners, thus, have key insights about how such programs could work to eliminate these disparities. One key insight, for example, is that these programs afford opportunities for individual-context relations that align youth strengths (e.g., hopeful future expectations) with contextual resources (e.g., mentoring; Rhodes and Lowe 2009), and, in doing so, enhance the probability of positive developmental changes.

The PYD literature suggests that the highest quality and most effective out-of-school-time programs share at least three key program features (termed the “Big Three;” Lerner 2004) that, when aligned with youth strengths, promote individual-context relations linked to PYD. That is, in safe and supervised spaces, effective youth development programs (1) provide youth with opportunities to develop and sustain positive relationships with adults; (2) promote the development of life skills through program activities; and (3) provide opportunities for youth to develop leadership skills and to apply these skills in their families, schools, and communities. BSA constitutes an exemplar character-focused youth development program (Hilliard et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015a, b). As well, BSA programs exemplify the enactment of the Big Three to imbue youth with the life skills needed to thrive personally and to develop into adults of character who are responsible citizens (e.g., societal leaders) who contribute positively to American democracy (Champine 2016; Ferris et al. 2015; Hershberg et al. 2015).

Scouting currently serves approximately 2.5 million youth and, across its 100+ year history, has served more than 100 million youth (Townley 2007). Empirical evidence from a large-scale longitudinal study, using propensity score matching to enact a counterfactual comparative design, suggested that traditional Scouting programs do promote positive character development among participating youth (Hilliard et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015b). In traditional Scouting programs, participants pay fees for their memberships, uniforms, and activities (e.g., camping trips). Meetings are usually held in organized out-of-school time settings and are led or facilitated by parent volunteers. However, in recent history, Scouting programs have not typically enrolled youth from low-income communities, primarily because of issues related to (1) a lack of funds possessed by the families of these youth to pay for program participation (e.g., for Scout uniforms and/or for camping trips); (2) a lack of access to Scouting programs in lower-resource communities (e.g., limited transportation); (3) environmental challenges associated with implementing Scouting activities (e.g., safety concerns, lack of outdoor space); and (4) challenges associated with engaging boys and their guardians in the program (e.g., in light of cultural misperceptions of the program; parental/guardian availability to jointly participate with youth; Champine 2016; Ferris et al. 2015; Hershberg et al. 2015).

BSA initiated Scoutreach to provide youth, who were experiencing these barriers to participation, free access to the Scouting curricula and programs. The Boy Scout Handbook (Boy Scouts of America 2016), which has content pertinent to character education, is given for free to youth participants. Scoutreach participants do not need to pay for memberships, uniforms, or transportations to take part in interactive activities at weekly meetings, field trips, service projects, or camping. In addition, Scoutreach is normally delivered to youth by trained and paid professionals. To date, there are few studies that have assessed whether Scoutreach is operating as intended or if it is associated with character development. Similarly, little research has examined the effects of different dimensions of program participation, including the breadth, duration, and intensity of participation or the role of youth engagement with the program, through different cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes. Although research thoroughly addressing this issue of program effectiveness and outcomes would entail launching large-scale evaluation designs, we seek in the present study to explore, within two relatively small BSA data sets that have participants in Scoutreach, if any evidence can be discerned linking program participation (in the form of reported experiences with Scoutreach activities and youth engagement with Scoutreach) with character development.

Neither of these data sets were designed to assess the links between Scoutreach participation and character development and, as such, the data sets do not afford statements that go beyond potentially identifying patterns of covariation between participation and character (i.e., there were no controls for endogeneity among Scoutreach youth and therefore no causal inferences can be made). However, we nevertheless sought to capitalize on these previously reported data sets because of the paucity of extant information about Scoutreach. We reasoned that, if any evidence of links could be identified, they could be a basis for generating hypotheses to be tested in future research explicitly designed to test for causal links between character development and Scoutreach participation, links that have been identified among mostly White and middle-class youth participating in traditional Scouting programs (Hilliard et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015b).

The Current Study

Despite the limitations of each of the two data sets we explore, we address the following question in the current study: Is there any quantitative or qualitative evidence for character development among Scoutreach participants? If so, we would then be able to suggest the features of future research that might both cross-validate any preliminary evidence of linkage that we found and, as well, ascertain the possible basis of the descriptions we provide. Scouting programs are organized across the U.S. into geographic areas, termed “councils.” We discuss two previously-conducted studies using data sets from two different councils.

Study 1: The Cradle of Liberty Council Study

The first of the two studies we present involved a longitudinal, mixed-methods investigation of character among youth participating in the BSA Cub Scouts program and among non-BSA participants. Both groups of participants were elementary school-aged youth in the greater Philadelphia area. The study took place between 2012 and 2014 (e.g., Hilliard et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015a, b). We present only the method and results relevant to our present cross-sectional assessment of the 266 youth participating in Scoutreach units in the overall Cradle of Liberty Study (which involved 1803 Scouts and 863 comparison youth).

Method

Participants

The Scoutreach participants were 266 boys recruited from Cub Scout packs in greater Philadelphia (M age = 10.54 years, SD = 1.58, range = 6.27 to 14.13 years). Scoutreach units recruit Scouts using methods that are similar to more traditional units. Youth are given a presentation about Scouting in their schools (either in their classrooms or in assemblies) and they are invited to join. A flier is then sent home providing more information about Scoutreach. Youth who wish to join are given an application and are then registered as Scouts with the local council. In the Cradle of Liberty study, these youth were predominantly Black or African American (72.9%), whereas, among the non-Scoutreach-supported Cub Scouts, 82% were European American/White; 9.2% were Black or African American; 2.9% were Hispanic or Latino; 2.6% were Asian/Pacific Islander; 2.2% were Other; and 1.1% identified as Multiethnic or Multiracial. Parents of 129 of the Scoutreach participants also reported on annual household income and the number of people residing in the household. Among these families, the annual family income levels were under $15,000 (44.19%), between $15,000 and $35,000 (34.88%), between $35,000 and $55,000 (15.50%), between $55,000 and $75,000 (3.10%), between $75,000 and $100,000 (1.55%), and between $100,000 and $150,000 (.78%). With the number of people in the same household considered, 126 of the 129 families (97.67%) met criteria for low-income status according to the Fiscal Year 2014 Income Limits for the Philadelphia area published by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Measures

Quantitative survey measures

Youth completed the Assessment of Character in Children and Early Adolescents (ACCEA; Wang et al. 2015a), which measures character virtues that are emphasized in the BSA curriculum (Boy Scouts of America 2016). The eight character virtues measured by the ACCEA include: obedience, religious reverence, cheerfulness, kindness, thriftiness, hopeful future expectations, trustworthiness (honesty and responsibility), and helpfulness. All character virtues measured by the ACCEA were scored using a five-point Likert-type scale, with values ranging from 1 (Not at all like me) to 5 (Exactly like me); higher scores indicated greater presence of the virtues measured by the scales. In prior research (Wang et al. 2015a), the ACCEA was found to have good reliability and validity for each of the attributes it indexes. In the current sample, the ACCEA attributes and their associated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were: obedience, .68; religious reverence, .67; cheerfulness, .74; kindness, .77; thriftiness, .64; hopeful future expectations, .59; trustworthiness, .74; and helpfulness, .79.

Qualitative interview protocols

A semi-structured interview protocol was used to examine youth experiences in Scouting, from the perspectives of Scouts and leaders, and to generate more in-depth information about character-related experiences that corresponded with the character virtues assessed with the ACCEA (Ferris et al. 2015). However, we also asked questions about other character-related attributes, such as tolerance (e.g., by asking about whether girls or boys that were different from Scouts should be included in Scoutreach) and about generosity (e.g., by asking about Scouts’ desires to enact positive changes in their communities).

Procedure

Data were collected by trained Scout leaders or by members of the research team (see Hilliard et al. 2014). For all youth data, parental consent and youth assent were obtained, and participants were incentivized with a $20 gift card. Parents/guardians also completed a brief questionnaire, which asked them to provide family demographic information and information about their children’s program participation. For qualitative interviews, youth were recruited from summer camps and were asked questions about their experiences in Scouting. Interviews were, on average, 15 min in length and were conducted and audio-recorded by members of the research team.

Results

A mixed-methods design with simultaneous quantitative-qualitative methods was used to examine the structure and content of character virtues among youth participating in Scouting programs through the Scoutreach initiative. The qualitative interview responses were examined to identify potential interindividual differences in the content of Scouting experiences and, as well, experiences in Scouting transferring to additional contexts in the lives of youth participating in this branch of BSA programming.

Quantitative Findings on the Use of a Previously-developed Character Measure

The results of a series of confirmatory factor analyses conducted using MPlus Version 7 indicated that an eight-factor character model comprised of each character attribute, separately, provided the best fit to the data (χ 2(467) = 677.17, p < .001, CFI = .90, TLI = .88, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .06). Similar to the results of Wang et al. (2015a), this model indicated that, although the character virtues were moderately to strongly correlated (rs = .25–.92), character virtues aligning with tenants of the Scout OathFootnote 1 and Scout LawFootnote 2 assess distinct aspects of character and require separate examination. All the factor loadings and estimates are included in a previously published paper (Ferris et al. 2015). These findings suggest that obedience, religious reverence, cheerfulness, trustworthiness, thriftiness, kindness, helpfulness and hopeful future expectations were distinct but associated dimensions of character. Such a perception of character attributes is shared among diverse samples, for example, predominantly European American/White youth enrolled in traditional Scouting programs, youth not involved in Scouting, and youth of color from low-SES communities participating in Scouting through Scoutreach. Moreover, these results support the idea that similar features of character can be assessed in the same way in youth participating in Scoutreach and in boys participating in traditional Cub Scout packs. However, the use of a measure to index character in Scoutreach youth is not commensurate with identifying an association between Scoutreach participation and character. To explore if there was any evidence for this link, we turned to the qualitative data.

Qualitative Findings on Character Development among Scoutreach Youth

Using directed content analysis (focused on character development in out-of-school-time programs; Hershberg et al. 2015), information across two coders (Cohen’s kappa = .74) indicated that the interview responses of youth consistently referenced character attributes of kindness, helpfulness, and hopeful future expectations. Youth described these attributes in providing examples of how they enacted such behaviors inside and outside of Scouting activities. Youth also indicated what enacting character virtues meant to them. For example, one Scout described learning about being kind from “the code right here… Scout’s law….there was some things that…we’re supposed to say, like, ten or 12 of them.” Another Scout explained how he enacted kindness outside of the Scouting context:

There’s not really much to tell about how I’m kind or anything, but I treat friends right. I don’t stand for bullying, like I don’t like when people get bullied. Usually at school if somebody is getting bullied, I ask them to leave them alone and they just do it…I help them a lot to teach them that bullying is wrong and it’s not cool to bully somebody.

Participants also described their commitments to enacting positive changes in their communities, often urban communities characterized by poverty and high rates of violence, and how Scoutreach leaders served as important role models in their lives. One boy explained that one of his goals for the future was “to make the world a better place… [so] White people could live with Black people and no matter what they could still be friends.” When asked if he learned anything in Scouting that “made him think this way,” he said that it was his leader who said: “no matter what, you can always be friends with White people or Black people.”

The youth also spoke about the need to be tolerant of others who were different from oneself and inclusive of others holding different opinions or viewpoints. For example, several youth said that all boys should be allowed to join Scouts and that girls should also be allowed to join Scouts.

These findings represent major differences in response content compared to interview data collected from youth enrolled in traditional Scouting units (Hershberg et al. 2015; Hilliard et al. 2014). Youth enrolled in traditional Scouting units were more likely to endorse established gender norms for participating in out-of-school time programs, particularly Scouting (i.e., Boy Scouts is for boys, whereas Girl Scouts is for girls).

Preliminary Discussion

These results provided evidence for potential connections between experiences in Scouting programs and character virtue development, more broadly. In addition, the responses provided by Scouts indicated that they enacted character attributes learned in Scouting in their daily lives, often in multiple contexts (e.g., at school or home, in peer groups), and that such attributes are multidimensional and may hold different, or multifaceted, meanings depending on who is applying them or how or when they are applied.

The usefulness of the quantitative examination was to assess how the character attributes that are of focal concern to BSA are best measured among Scoutreach youth of color from low-income backgrounds. The preliminary evidence we obtained suggested that, in a sample of Scoutreach youth, the eight BSA-emphasized character virtues were best measured as distinct but associated dimensions. This finding is equivalent to findings regarding character found among youth in traditional Scouting programs (e.g., see Wang et al. 2015a), and therefore provides a basis for an assessment of measurement invariance in larger samples wherein there is an interest in using a tool (the ACCEA) developed to index key principles of Scouting curricula (obedience, trustworthiness, etc.). This finding suggests also that character attributes can be measured in the same way across diverse samples and may facilitate between-group comparisons once measurement invariance is established (e.g., Scoutreach youth, traditional Scouts, and youth from comparison schools who are not participating in the Scouting program). Thus, future research could explore if Scoutreach youth experience ecological assets in this instance of BSA programming that correspond to those assets found in traditional Scout contexts (Hilliard et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015a, b).

In turn, the qualitative findings with the Scoutreach youth do support the idea that there is a link between participation in Scoutreach and character-related attributes such as kindness, helpfulness, hope, tolerance, and community contribution (generosity). Although the statements made by the youth do not prove a causal connection between participants’ Scoutreach experiences and character development, especially because the design of this portion of the Cradle of Liberty study did not include controls for endogeneity, the findings are nevertheless useful. They allow us to answer in the affirmative the key question our exploratory research addressed: There is some preliminary evidence suggesting that the link between Scouting and character development found among participants in traditional BSA programs (e.g., Wang et al. 2015b) may also be identified among Scoutreach participants. As such, investment in longitudinal research using counterfactual causal modeling designs that control for endogeneity (Sampson 2016) is warranted.

Study 2: The Spirit of Adventure Council Study

The Spirit of Adventure Study was a pilot, cross-sectional, mixed-methods investigation (Champine 2016). The study involved assessment of the relations among different dimensions of youth engagement (e.g., cognitive, emotional, and behavioral) in Scoutreach and different positive youth development outcomes, including character, among a small sample of Scoutreach participants in the Spirit of Adventure Council in the greater Boston area (Champine 2016). The study took place between 2015 and 2016.

Method

Participants

Scoutreach participants included 32 boys recruited from two Spirit of Adventure Council units (M age = 9.97 years, SD = 2.46, range = 6–14 years). Most Scouts (62.5%) did not identify as Hispanic or Latino. Youth were also from diverse racial backgrounds: 37.5% identified as Multiethnic/Multiracial; 15.6% as Black or African American; 9.4% as American Indian/Native American; 9.4% as Asian/Pacific Islander; 9.4% as European American/White; and 6.3% as Other. Data on race were missing for four (12.5%) Scouts. The largest proportion of parents/guardians (21.9%) reported an average total household income of $45,000 to less than $55,000; 40.7% of remaining parents/guardians reported incomes below this level and 34.4% reported incomes above this level. Income data were missing for one (3.0%) parent/guardian. Parents/guardians also reported the total number of adults (including themselves) and children residing in their household. According to the Fiscal Year 2015 Income Limits for the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy area published by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 68.8% of parents/guardians in the current study met criteria for low-income status.

Measures

Youth (n = 32) completed measures pertinent to the character development focus of the present article. They responded to the items in the ACCEA (Wang et al. 2015a) and to several interview questions pertinent to character development. Cronbach’s alphas for the ACCEA were: obedience (α = .73); religious reverence (α = .66); cheerfulness (α = .74); kindness (α = .83); thriftiness (α = .52); hopeful future expectations (α = .71); trustworthiness (α = .89); and helpfulness (α = .72). In addition, a measure of youth cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement with the Scoutreach activities was used. This measure was adapted from the school engagement measure used by Li and Lerner (2013). Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement were each measured by five items (αs = .95, .79, and .67, respectively). Items assessing cognitive engagement included “I want to learn as much as I can in Scouts” and “Scouts is very important for future success.” Items assessing emotional engagement included “I think Scouts is fun and exciting” and “I care about Scouts.” Items assessing behavioral engagement included “I come to Scout meetings and activities on time” and “I work hard to do well in Scouting.”

In turn, Scouts (n = 10) completed interviews that asked them about their Scouting- and community-related experiences, and whether they believed that Scouting prevented risk behaviors and promoted healthy development. On average, the interviews took 20–25 min to complete.

Procedure

Survey and interview data were collected by two trained members of the research team (Champine 2016). For all data, parental consent, parental assent, and youth assent were obtained. Scouts each received a small toy (e.g., finger light) for completing a survey, and parents/guardians each received a $10 gift card to a national retail outlet for completing a survey. Scouts received a $15 gift card for completing an interview.

Results

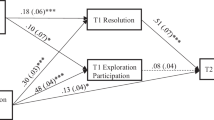

Quantitative Findings on Levels of Youth Character and Program Engagement

The quantitative portion of the study aimed to assess if there was evidence that youth cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement in Scoutreach was linked to character attributes. As shown in Table 1, Scouts’ mean scores were moderate to high for the character attributes measured by ACCEA and for all the engagement dimensions. In addition, Table 2 shows that, despite the small sample size involved in this pilot study, Pearson product-moment correlations between Scouts’ cognitive engagement and youth hopeful future expectation, trustworthiness, and helpfulness were significant and positive. Scouts’ emotional engagement was positively associated with all eight of the character attributes measured by ACCEA. In addition, Scouts’ behavioral engagement in Scoutreach was positively associated with youth trustworthiness.

In sum, quantitative evidence from this pilot investigation of the small sample involved in the Spirt of Adventure Council study (Champine 2016) suggested that, at least insofar as internal consistency reliability and descriptive scores are concerned, the ACCEA behaved in a manner fairly consistent with evidence derived from an assessment involving a larger sample of Scouts; that is, youth involved in the traditional BSA programs studied by Hilliard et al. (2014) and Wang et al. (2015a, b). In addition, youth program engagement in Scoutreach was associated with Scouts’ character attributes. Emotional engagement, or having positive feelings toward Scoutreach (e.g., feeling happy, excited, a sense of belonging) seemed to be a particularly important dimension of engagement that was related to attributes of character indexed by the ACCEA measure.

Qualitative Findings on Youth Character-Relevant Experiences in Scoutreach

Using an exploratory approach consistent with the pilot nature of the investigation, interpretative phenomenological analysis (e.g., Smith 2011) was used to provide a dynamic and idiographic approach to qualitative data analysis; this approach aims to facilitate in-depth analysis of individuals’ lived experiences and how they make meaning of their experiences. The interview protocol questions were guided by prior qualitative research with Scoutreach (e.g., Hershberg et al. 2015). Interviews conducted with Scouts revealed positive views of, and experiences in, Scoutreach and challenges that Scouts faced in their communities (e.g., related to drugs and gangs). The interviews also shed light on differences in individuals’ views of important aspects of Scoutreach linked to Scout engagement.

Scouts described various attributes, skills, and behaviors that they learned in Scoutreach. For instance, Scouts described learning attributes consistent with the Scout Law, including kindness and helpfulness (e.g., “[Scouts teaches] you how to help other people in different ways”). In addition, Scouts described learning values and skills, such as teamwork and respect, and provided examples of how they applied this learning in other contexts. For example, as one Scout said: “I’ve learned to be more courteous…just today, somebody dropped their stuff and I helped them to pick it up.”

All of the Scouts described their favorite Scoutreach experiences as involving activities (e.g., “We play fun games…[go on] trips, outings, camp-outs…”). For example, Scouts often described the importance of camping and other outdoor activities in getting and keeping them interested in the initiative. For example, all Scouts described their active participation in camping and other outdoor activities (e.g., “we…make a fire and sleep in tents that we pitched”). In comparison, parents/guardians more strongly related Scouts’ engagement in Scoutreach to their relationships with other Scouts. For instance over half of parents/guardians linked their sons’ emotional engagement in Scoutreach to their sons’ peer relationships (e.g., “He’s excited to come [to Scouts]. He knows he’s going to…[interact] with other boys

Preliminary Discussion

Together, the survey and interview data suggested Scoutreach participants had moderate to high self-reported levels of character and that these attributes were related to their engagement in Scoutreach activities. The ACCEA scores of the small sample of Scoutreach participants in this study are comparable to those scores for Scoutreach youth in the Cradle of Liberty study, and to scores from a larger sample of youth from traditional Scouting programs (e.g., Wang et al. 2015a, b). We may conclude, then, that the results from this small, pilot sample underscore the likelihood of covariation between Scoutreach participation and character attributes.

Of course, a key limitation of the Spirit of Adventure Council study is that there was no comparison group in this pilot investigation. Boys who were enrolled in Scoutreach may have differed in important ways from their peers who were not involved in the initiative and/or who dropped out of the initiative. Thus, future research should include demographically similar comparison samples within a study involving a larger sample and, as already noted, a counterfactual causal modeling design that involves controls for endogeneity.

General Discussion

Despite the noted benefits of youth development programs on positive youth development (Vandell et al. 2015), economically disadvantaged youth and youth of color are typically underrepresented in such programs and often face barriers to being viewed as individuals of character who will contribute positively to the society (Spencer and Spencer 2014). How personal strengths and contextual assets can be aligned to promote positive development among underrepresented youth and to promote youth contribution to the society has become an increasingly timely and important line of work among youth-serving researchers and practitioners (Spencer and Spencer 2014). As such, we conducted secondary analyses of two previously reported studies in order to provide exploratory data about whether a relatively recent innovation in youth programming within Boy Scouts of America, Scoutreach, was linked to attributes of character development among youth not traditionally involved in these programs; that is, youth of color living in impoverished socioeconomic circumstances.

The first study conducted with the Scoutreach youth in the Cradle of Liberty council examined whether the organizational structure of character attributes found among youth in traditional Scouting programs, applied to Scoutreach youth. The study also assessed if participation in Scoutreach was linked to character development. The data suggested that the eight BSA-emphasized character attributes were perceived by Scoutreach youth in a manner similar to what was seen among youth in traditional Scouting programs (Wang et al. 2015a). The focus groups and interviews with Scoutreach youth provided examples of key character attributes that youth learned in Scoutreach and of the ways in which youth applied these attributes in various settings (e.g., home, school, community). In comparison, the second study conducted with the Scoutreach youth from the Spirit of Adventure council investigated in greater depth whether Scoutreach youth were cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally engaged in the initiative. The study also assessed if these dimensions of engagement relate to character.

Across the studies, we found that the presence of sustained relationships with leaders of Scoutreach units, and Scouts’ exposure to the Scoutreach initiative over time, were linked to character virtues. In particular, the caring relationships that Scouts formed with their leaders and other Scouts and the experiential activities in which Scouts were involved (e.g., camping) seemed to be important facets of Scouting. These findings resonate well with the related literature on youth mentoring and the supportive role of engaging adult leaders on positive development (e.g., DuBois and Karcher 2014; Griffith and Larson 2016). Accordingly, relationships developed through Scoutreach activities might contribute to Scouts’ emotional engagement with the program, and, perhaps as well, to character attributes associated with engagement. In particular, across the studies, participants described how Scouting emphasized the development of attributes reflected in the Scout Law, such as helpfulness, and, as well, emphasized the application of this learning in different contexts. Preliminary evidence was found from the two data sets to support the presence of character development among Scoutreach participants and the link between program engagement and character development.

The two studies we capitalized on to undertake this exploration had several important limitations. They were not designed to elucidate questions about program effectiveness of Scoutreach; thus, they offered at best only descriptive information about patterns of covariation between youth participation in Scoutreach and character development. In other words, the design limitations of the studies preclude causal inferences about program effects. Both studies involved relatively small samples, and—insofar as the qualitative data were concerned—relatively little information was available for triangulation with the quantitative measure of character used in the study, the ACCEA (Wang et al. 2015a), which indexed eight attributes associated with the BSA conception of character.

Nevertheless, even in the face of the limitations of these two data sets, there was sufficient quantitative and qualitative evidence in the two studies to suggest that the key question addressed in the present article—whether there is any quantitative or qualitative evidence in the data sets for the presence of character development among Scoutreach participants—was answered affirmatively. Indeed, especially when youth are emotionally engaged in Scoutreach activities, the links between character attributes and participation seem most evident. Of course, future longitudinal research having the design attributes we have discussed should test the hypothesis that emotional engagement is key to creating the conditions wherein Scoutreach participation contributes to character development.

However, if such causal linages are found, then youth program professionals would have an important target to focus on in developing activities that would bring the resources of youth development programs to currently underserved or unserved youth populations (Vandell et al. 2015). Additional questions, for instance, about how the intensity and duration of program participation moderated any relation between participation and character development, would also have to be addressed in such research (Vandell et al. 2015). Nonetheless, based on the suggestions about participation-character covariation found in the present research, research with youth of color from impoverished backgrounds could proceed on the assumption that programs such as Scoutreach provided resources that would enhance the positive development of these youth.

The hopes of millions of underserved and unserved youth—most often in the U.S. youth of color living in poor communities (Sampson 2016)—for better lives characterized by personal value, meaning, and social contribution should be able to be fulfilled by opportunities to avail themselves of the resources of youth development programs (e.g., Lerner et al. 2017; Vandell et al. 2015). Our admittedly preliminary and exploratory analyses of two extant data sets suggested that the Scoutreach initiative may be an effective means to promote positive development and, specifically, character, among youth previously underserved by the programs of Boy Scouts of America. As such, Boy Scouts of America has an historical opportunity to conduct rigorous evaluations of Scoutreach and, through such work, generate the evidence for delivering programs for which young people in underserved communities are waiting. We look forward to this contribution.

Conclusion

Economically disadvantaged youth and youth of color often experience barriers to life opportunities for thriving and positive development. High-quality youth development programs have the potential to provide meaningful opportunities and experiences for ethnically, racially, and economically diverse youth. By capitalizing on two previously reported data sets which had information on character development and program participation from youth of color from low-income communities, we found some preliminary quantitative and qualitative evidence about the presence of character development among youth who participated in Scoutreach activities and about the potential linkage between program engagement (emotional engagement in particular) and character development. Future research in collaboration with youth development programs that serve demographically similar youth may draw upon the preliminary evidence of the linkage that we found to cross-validate our findings and to reveal greater insights into the developmental processes involved in youth program engagement.

Notes

Scout Oath: “On my honor I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law; to help other people at all times; to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.”

Scout Law: “A Scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.”

References

Boy Scouts of America. (2016). Boy Scout Handbook (13th ed.). Irving, TX: Boy Scouts of America.

Cattell, R. B. (1966). Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Champine, R. B. (2016). Towards the promotion of positive development among youth in challenging contexts: A mixed-methods study of engagement in the Scoutreach program. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Tufts University, Medford, MA

DuBois, D. L., & Karcher, M. J. (2014). Youth mentoring in contemporary perspective. Handbook of youth mentoring (2nd ed.). (pp. 3–13). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2015). Children and socioeconomic status. In M. H. Bornstein, & T. Leventhal (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. Vol. 4: Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems (7th ed.). (Editor-in-chief: R. M. Lerner). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy414.

Ettekal, A. V., Callina, K. S., & Lerner, R. M. (2015). The promotion of character through youth development programs: A view of the issues. Journal of Youth Development, 10(3), 6–13.

Ferris, K. A., Hershberg, R. M., Su, S., Wang, J., & Lerner, R. M. (2015). Character development among youth of color from low-SES backgrounds: An examination of Boy Scouts of America’s ScoutReach program. Journal of Youth Development, 10(3), 14–30.

Griffith, A. N., & Larson, R. W. (2016). Why trust matters: How confidence in leaders transforms what adolescents gain from youth programs. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 790–804. doi:10.1111/jora.12230.

Guerra, N., & Olenik, C. (2013). State of the field report: Holistic, cross-sectoral youth development. Report prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/USAID%20state%20of%20the%20field%20holistic%20cross%20sectoral%20youth%20development%20final%202_26.pdf.

Hershberg, R. M., Chase, P. A., Champine, R. B., Hilliard, L. J., Wang, J., & Lerner, R. M. (2015). “You can quit me but I’m not going to quit you:” A focus group study of leaders’ perceptions of their positive influences on youth in Boy Scouts of America. Journal of Youth Development, 10(2), 5–30.

Hilliard, L. J., Hershberg, R. M., Wang, J., Bowers, E. P., Chase, P. A., Champine, R. B., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Program innovations and character in Cub Scouts: Findings from year 1 of a mixed-methods, longitudinal study. Journal of Youth Development, 9(4), 4–30.

Lerner, R. M. (2004). Liberty: Thriving and civic engagement among America’s youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Lerner, R. M., & Callina, K. S. (2014). The study of character development: Towards tests of a relational developmental systems model. Human Development, 57(6), 322–346. doi:10.1159/000368784.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Bowers, E. P., & Geldhof, G. J. (2015). Positive youth development: A relational developmental systems model. In W. F. Overton & P. C. Molenaar (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. Vol. 1: Theory and method. (7th ed., pp. 607–651). (Editor-in-chief: R. M. Lerner). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy116.

Lerner, R. M., Vandell, D. L., & Tirrell, J. (Eds.), (in preparation). Approaches to the development of character. Journal of Character Education.

Lerner, R. M., Wang, J., Hershberg, R. M., Buckingham, M. H., Harris, E. M., Tirrell, J., …Lerner, J. V. (2017). Positive youth development among minority youth: A relational developmental systems model. In N. J. Cabrera & B. Leyendecker (Eds.), Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (pp. 5–18). Springer: Netherlands.

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2013). Interrelations of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive school engagement in high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(1), 20–32. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9857-5.

McLoyd, V. C., Purtell, K. M., & Hardaway, C. R. (2015). Race, class, and ethnicity in young adulthood. In R. M. Lerner (Editor-in-chief) & M. E. Lamb (Vol Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. Vol. 3: Socioemotional processes. (7th edn., pp. 366-418). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy310.

Nucci, L. (2017). Character: A multi-faceted developmental system. Journal of Character Education. (In press).

Rhodes, J. E., & Lowe, S. R. (2009). Mentoring in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. Vol. 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development. 3rd edn. (pp. 152–190). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002006.

Sampson, R. J. (2016). The characterological imperative: On Heckman, Humphries, and Kautz’s the myth of achievement tests: The GED and the role of character in American life. Journal of Economic Literature, 54(2), 493–513. doi:10.1257/jel.54.2.493.

Sampson, R. J., & Winter, A. S. (2016). The racial ecology of lead poisoning: Toxic inequality in Chicago neighborhoods, 1995-2013. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 13(2), 1–23. doi:10.1017/S1742058X16000151.

Seider, S., Jayawickreme, E., & Lerner, R. M. (2017). Theoretical and empirical bases of character development in adolescence: A view of the issues. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1149–1152. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0650-3.

Smith, J. A. (2011). Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5(1), 9–27. doi:10.1080/17437199.2010.510659.

Spencer, M. B., & Spencer, T. R. (2014). Exploring the promises, intricacies, and challenges to positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1027–1035.

Townley, A. (2007). Legacy of honor: The values and influence of America’s Eagle Scouts. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Vandell, D. L., Larson, R. W., Mahoney, J. L., & Watts, T. W. (2015). Children’s organized activities. In M. H. Bornstein & T. Leventhal (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. Vol. 4: Ecological settings and processes (7th ed., pp. 305–344). Editor-in-chief: R. M. Lerner. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy408.

Wang, J., Batanova, M., Ferris, K. A., & Lerner, R. M. (2016). Character development within the relational developmental systems metatheory: A view of the issues. Research in Human Development, 13(2), 91–96. doi:10.1080/15427609.2016.1165932.

Wang, J., Ferris, K. A., Hershberg, R. M., & Lerner, R. M. (2015a). Developmental trajectories of youth character: A five-wave longitudinal study of Cub Scouts and non-Scout boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(12), 2359–2373. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0340-y.

Wang, J., Hilliard, L. J., Hershberg, R. M., Bowers, E. P., Chase, P. A., Champine, R. B., & Lerner, R. M. (2015b). Character in childhood and early adolescence: Models and measurement. Journal of Moral Education, 44(2), 165–197. doi:10.1080/03057240.2015.1040381.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of project directors and research assistants (including graduate and undergraduate students) to conduct the studies used in the present research. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the participation of youth and program leaders across the two studies, which made the present research possible.

Funding

The preparation of this article was supported in part by a grant to Richard M. Lerner by the John Templeton Foundation and by an award to Robey B. Champine from the Society for Research in Child Development.

Author Contributions

J.W. participated in the study’s design and coordination, performed the secondary analyses, and drafted the manuscript; R.B.C. participated in the study’s design, performed the analyses, and drafted the manuscript; K.A.F. participated in the data analyses and writing of the manuscript; R.M.H participated in the study’s design, data analyses, and editing of the manuscript; D.J.W. participated in the study’s design, data collection, and editing of the manuscript; B.M.B. participated in data collection and editing of the manuscript; S.S. participated in data collection, data analyses, and editing of the manuscript; R.M.L. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This research used secondary data based on studies conducted at the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development, all of which received approval from the Internal Review Board at Tufts University.

Informed Consent

All eligible participants for the studies used in the current research were fully informed about their voluntary participation. If youth wished to refrain from participation, or if their parents disagreed with their children’s participation, they were free to do so. Only youth who provided permission or assent to participate, and who had parental permission to participate, were involved in the studies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Champine, R.B., Ferris, K.A. et al. Is the Scoutreach Initiative of Boy Scouts of America Linked to Character Development among Socioeconomically, Racially, and Ethnically Diverse Youth?: Initial Explorations. J Youth Adolescence 46, 2230–2240 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0710-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0710-8