Abstract

Peer victimization has been identified as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. The current study investigated the longitudinal interplay among social support, peer victimization and depressive symptoms in early adolescence. We specifically investigated the promotive and protective role of parental and friendship support on the longitudinal relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms. A total of 960 Swiss adolescents (49% female, Mage 13.2 years) completed an electronic questionnaire four times, with 6-month intervals. Trivariate cross-lagged models with latent longitudinal moderations were computed. The analyses confirmed that peer victimization was positively associated with changes in depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms were positively associated with changes in victimization. Furthermore, bidirectional longitudinal associations between both parental and friendship support and depressive symptoms were found, while neither parental nor friendship support was found to be longitudinally associated with peer victimization. Further, neither parental nor friendship support moderated the longitudinal relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms. Thus, the present results suggested that parental and friendship support were promotive factors for adolescents’ well-being, while neither parental, nor friendship support buffered the effect of victimization on depressive symptoms, thereby yielding no evidence for their longitudinal protective effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to The World Health Organization (2012), an estimated 32% of children across 38 countries experience some form of peer victimization at least once in their lifetime. This estimation is highly concerning, considering that peer victimization has been identified as a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Reijntjes et al. 2010). In order to identify factors that might promote well-being and/or protect from the negative consequences of peer victimization, the current study investigated the longitudinal interplay among social support, peer victimization, and depressive symptoms. Herein, we specifically examined whether social support could be considered as a protective factor that buffers the effect of risk factors such as peer victimization, or as a promotive factor that fosters well-being independently of the extent of risk factors (Masten and Gewirtz 2008).

Peer Victimization and Depressive Symptoms

Bullying has been defined as a repeated and intentional act of aggression that is directed at a defenseless victim (Olweus 1993). This act may be relational or emotional (e.g., gossiping), verbal (e.g., name-calling) or physical nature (e.g., hitting; Nansel et al. 2001). While the term bullying is usually used to refer to the aggressive act that is carried out by the bully (i.e., the perspective of the perpetrator), the term peer victimization is usually used to refer to suffering such an aggressive act (i.e., the perspective of the victim). An increased likelihood of peer victimization has been observed in contexts in which individuals have no opportunity to choose their peers and are not free to leave the contexts as they wish (Alsaker 2003). Thus, peer victimization can be found in many environments such as schools (including preschool), family, military service, and prisons (Alsaker 2012; Monks and Coyne 2011). For adolescents, peer victimization is most likely to occur at school, as they spend a significant proportion of the day at school, cannot choose their class and schoolmates, and cannot leave school without risking negative consequences.

One of the debilitating and pervasive consequences of victimization is increased depressive symptoms (Desjardins and Leadbeater 2011; Hawker and Boulton 2000; Reijnties et al. 2010; Schwartz et al. 2015; Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater 2013). This issue was found in different cultural contexts, including Europe (e.g. Menesini et al. 2009; Perren and Alsaker 2009; Strohmeier et al. 2011; Williams et al. 1996), Australia (e.g., Slee 1995), New Zealand (e.g., Denny et al. 2004), the United States (e.g., Bogart et al. 2014), Canada (e.g., Yeung and Leadbeater 2010; Craig 1998); Africa (e.g., Townsend et al. 2008), and Asia (Huang et al. 2013; Schwartz et al. 2002). Additionally, findings from studies using cross-lagged designs also showed that victimization not only increased the risk for depressive symptoms, but also that depressive symptoms increased the risk of later victimization (Reijntjes et al. 2010). These reciprocal influences suggest a vicious cycle and thus a high stability of peer victimization and depressive symptoms. Given the detrimental effects of peer victimization and the vicious cycle that might arise over time, it is crucial to examine the longitudinal interplay between peer victimization and depressive symptoms, and to examine potential promotive and protective factors that might help in maintaining a desirable level of well-being among adolescents.

Social Support as Protective or Promotive Factor

Although many adolescents experience peer victimization, not all adolescents suffer from its detrimental effects in the same way. One explanation for these interindividual differences is positive environmental factors such as social support. Social support has been defined as “an individual’s perception of general support or specific supportive behavior (available or acted on) from the people in their social network, which enhances their functioning or may buffer them from adverse outcomes” (Malecki and Demaray 2003, p. 232), and can be further differentiated into emotional, informational, and instrumental support (Cohen and Pressman 2004; Malecki and Demaray 2003). In adolescence, both parents and friends represent central potential sources of social support. A recent overview of the impact of the family context on children’s mental health indicated that parental warmth/support is an important broad dimension of the parent-child dyad. More specifically, parental warmth/support has been conceptualized as parental behaviors that “convey positive affect and emotional availability, are sensitively responsive to the emotional needs of the child and suggest a supportive presence on the part of the caregiver” (Davies and Sturge-Apple 2014, p. 144). In the following we refer to this dimension with the term parental support. Similarly, we will refer to friendship support as the same construct with respect to the relationship with peers.

The concurrent investigation of parental and friendship support is critical because these forms of relationships are the most important ones during the adolescent period. Empirical research has demonstrated that during adolescence there is a shift towards greater autonomy and importance of friendships, and a reduction in physical affection, intimacy and the time spent with parents (Brown and Larson 2009). These changes may suggest a decrease in the influence of parental support. However, evidence suggests that parents continue to be influential in their children’s lives, and their support is a coping strategy against adverse events (Collins and Laursen 2004; Rueger et al. 2016). Moreover, the increased significance of friendships implies that friendship support may be stronger at buffering the effect of victimization and depressive symptoms, although there is evidence to suggests that this may not always be the case. For example, Mezulis and colleagues (2004) found that friendship support was more important as a protective factor in middle childhood than in adolescence due to the increase in complexity of friendships associated with developmental shifts. By concurrently investigating parental and friendship support, this study will provide a deeper understanding of whether either or both source of support uniquely act as promotive or protective factors for well-being in the context of peer victimization during adolescence.

Positive environmental factors such as social support can be understood as measurable attributes of relationships. From a developmental psychopathology perspective, these attributes can exert a promotive or a protective effect on health outcomes (Masten and Gewirtz 2008). The conceptual distinction between promotive and protective factors lies in the nature of their effect on health outcomes. While the effect of promotive factors is independent of potential risk factors, the effect of protective factors depends on the extent of a given risk factor (Masten and Gewirtz 2008). In the context of peer victimization as a well-established risk factor, a negative association would be expected between social support and depressive symptoms both in the case of a promotive and a protective effect. Further, social support would be considered as protective if it would moderate and, more specifically, reduce (i.e., buffer) the impact of peer victimization on depressive symptoms. In contrast, if the effect of peer victimization on depressive symptoms would not be moderated by social support, then social support would be considered as promotive.

The Stress-Buffering Hypothesis (Cohen and McKay 1984) suggests that social support is a protective factor. Specifically, it is assumed that successful coping with life stressors is possible if the individual perceives that the support network can and will provide the necessary support. Moreover, social support has been shown to be promotive and mitigate the impact of stressful life events by reducing stressful reactions and adverse physiological responses (Cohen and Pressman 2004). For instance, talking to trusted others about stressful experiences has been shown to reduce the occurrence of negative thoughts and maladaptive behaviors, to help redefine the problem, to bolster coping self-efficacy, and psychological well-being (Ge et al. 2009). Accordingly, social support might have a protective as well as a promotive effect on mental health problems.

Social Support and Victimization

As for parental support (e.g., parental involvement, warmth, and affection), research has demonstrated that it acts as a protective factor on the relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Davidson and Demaray’s (2007) study on 355 children’s perception on social support from multiple sources found that children who were victims reported more internalizing distress when they had less support from their parents. This buffer effect was evident for girls, but not for boys. Similarly, other longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have confirmed that parental support has a strong influence on the reduction of the association between victimization and depressive symptoms (Desjardins and Leadbeater 2011; Tanigawa et al. 2011). Likewise, studies that have investigated the relationship between victimization and other risk factors such as general internalizing problems (Stadler et al. 2010; Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater 2013) and parent-adolescent conflict (Sheeber et al. 2007) consistently showed the effects of parental support on reducing or eliminating the strength of the association.

Besides these studies showing protective effects, evidence suggests that parental support is also a promotive factor for adolescents’ well-being. For instance, adolescents with greater maternal support were found to experience less psychological distress (Holt and Espelage 2005) and greater family togetherness (Field et al. 2002). Parental support was found to also be associated with the reduction of depressive symptoms (Auerbach et al. 2011; Colarossi and Eccles 2003; Heaven et al. 2004; Lereya et al. 2013). Further, the parent-adolescent relationship reduces the chance of adolescent depression when parents themselves are not depressed, which shows the importance of family processes in influencing adolescent well-being (Sarigiani et al. 2003). In relations to victimization, adolescents with limited support from parents or lack relationship balance are more likely to become victims or bullies (Albayrak et al. 2014; Perren and Hornung 2005; Nikiforou et al. 2013; Sapouna and Wolke 2013).

Regarding friendship support, it has been found to be a protective factor that buffered the effect of victimization on depressive symptoms. Previous research consistently showed children who were victims reported lower levels of depressive symptoms when they received support from their friends (Desjardins and Leadbeater 2011; Tanigawa et al. 2011). Moreover, investigations into gender differences have also confirmed the protective nature of friendship support. Schmidt and Bagwell’s (2007) study on secured friendship found that friendship buffered the effect of victimization on depressive symptoms for girls, but not for boys. On the contrary, Davidson and Demaray’s study (2007) demonstrated that boys who were victims reported less internalizing problems when they had strong support from friends, but a similar result was not found for girls. The effects of friendship support also extend to externalizing problems. Investigations have confirmed that among children with externalizing problems strong friendship support, particularly from best friends, attenuated victimization (e.g., Bollmer et al. 2005).

Studies have also frequently demonstrated that friendship support is a promotive factor for adolescents’ well-being. It has been found to reduce the likelihood of depressive symptoms (e.g., Klima and Repetti 2008; Rueger et al. 2010). In comparing non-depressive and depressive children, Herman-Stahl and Petersen (1996) found that non-depressive children had more positive friendships compared to depressive children. These results support the notion of friendship support as a promotive factor in preventing the emergence of depressive symptoms.

Friendship support was also found to be negatively linked to the occurrence of victimization episodes (e.g., Kendrick et al. 2012). Other studies confirmed that children were at an increased risk for depression and victimization when they had fewer friends, lacked a close relationship with a best friend, and were excluded from social contexts. Moreover, other cross-sectional studies found that these children may have had characteristics that made it difficult for them to build meaningful relationships with others (e.g. Du et al. 2015; Fox and Boulton 2005). For victims who had friends, it was found that they lack the ability to recruit help from their friends to reduce victimization episodes. Some of the friendship support that were received also came from victims who were unable to offer protection (Champion et al. 2003; Hodges et al. 1999). In other instances, victims had general friendship support, but their friends did not perceive the victim’s experiences as severe or shared empathetic concerns (Slonje and Smith 2008). The central role of parental support and friendship support as a protective factor and promotive factor for psychological well-being of adolescents is important and warrants further longitudinal investigation.

An important limitation in the literature is that parental support and friendship support have not been extensively investigated as a moderator in the specific longitudinal relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms. Studies that have examined the longitudinal effects of parental support focused on the general family and personal life stressors (Ge et al. 2009; Zimmerman et al. 2000), peer stressors other than victimization (e.g. fighting with friends, feeling pressure from friends, criticism from friends), and non-peer pressures (e.g. poor academic performance, financial challenges) (Hazel et al. 2014). Mixed findings have been found in studies that assess the longitudinal effects of parental support. For instance, in the study by Yeung and Leadbeater (2010), both mother and father support moderated the association between physical victimization and emotional and behavioral problems. A follow-up longitudinal study also found that mother support acted as a protective factor by reducing episodes of physical victimization on internalizing problems for girls, but not boys. At the same time, father support did not moderate the relationship. Conversely, father support increased the effects of the association between relational victimization and internalizing symptoms for boys, but mothers’ support did not act as a protective factor on the association for both genders (Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater 2013).

As it relates to friendship support, Desjardins and Leadbeater (2011) concurrently investigated and found a protective effect of parent and friendship support on the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms. Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater (2013) found that friendship support longitudinally increased the association between physical victimization and internalizing problems for girls, but acted as a protective factor for boys by reducing the association. The protective factor of friendship support was also found for boys when the relationship between relational victimization and internalizing problems was tested, but was not found for girls.

Aims and Hypotheses

Although the studies described above have expanded our knowledge of the promotive and protective effect of support on adverse life events, it is still unclear if parental support and friendship support play a promotive or a protective role in the association between peer victimization and depressive symptoms. In particular, our understanding of the role of parental and friendship support in the longitudinal association between victimization and depressive symptoms is still quite limited, as only very few studies examined the longitudinal interplay among social support, peer victimization, and depressive symptoms. Accordingly, longitudinal investigations using state of the art statistical methods are needed to enhance our understanding of this complex longitudinal interplay. In the present study, we addressed these limitations by using a longitudinal design with four measurement occasions with time intervals of six months. Further, the following peculiarities of the present study were implemented to address previous limitations. First, we used state of the art structural equation modeling techniques, namely a trivariate cross-lagged model, that allows for testing of possible directions of effects and control for both temporal and cross-sectional effects. Further, latent variable and latent interaction modeling was used to obtain measurement-free estimates of the longitudinal associations of interest as well as information on the fit of the proposed model. Second, we compared the role of both friendship and parental support. Using a cross-lagged design, we investigated whether parental and/or friendship support was associated with changes in victimization and depressive symptoms using several assessment waves. The literature on adolescent emotional health and well-being will benefit from studying the effects of social support because it will aid a better understanding of whether a particular source of support is more effective at decreasing victimization and depressive symptoms. Third, we investigated whether social support is a promotive factor or a protective factor. Also, we investigated whether parental and friendship support directly reduced the level of depressive symptoms over a 6-month period.

Thus, we hypothesized the following: (a) similar to previous studies peer victimization has a positive and reciprocal longitudinal relationship with depressive symptoms (Schwartz et al. 2015; Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater 2013); (b) longitudinally there is a negative relationship between social support and depressive symptoms (Auerbach et al. 2011; Klima and Repetti 2008). Furthermore, we hypothesized that (c) social support (by parents or friends) moderates the longitudinal relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms, that is, social support is a protective factor; and (d) there is a longitudinal negative relationship between social support and peer victimization (Perren and Hornung 2005; Kendrick et al. 2012).

Method

Procedure

The data that was used in this study was taken from netTEEN, which is a longitudinal study that was conducted among adolescents in Switzerland. Four waves of data assessment were conducted from November 2010 to May 2012 with six-month time intervals. As required by Swiss legislation, permission to carry out the study was obtained from the respective school councils. School directors and teachers from the selected schools volunteered, and parents were informed about the study and were asked to inform the teachers if they did not want their children to participate (passive consent). The parents of four adolescents refused to participate in each assessment. The participants were informed about the survey’s procedure and goal, and were given the opportunity to refrain from participation with no negative consequences (informed oral consent). Students who did not want to participate were offered another activity during the relevant school period. However, no students refused to participate.

The study was conducted through an electronic questionnaire that was administered on netbooks during class sections. All students were given a personal password and login to access the questionnaire on the netbooks. A personal password and login were created for students who were not present during the survey session to enable that they complete the survey online. Data from the four waves was matched using the login information.

Sample

The sample consisted of seventh-grade students from three of the 26 Swiss cantons (i.e. member states of the Swiss Confederation)—Ticino, Valais, and Thurgau. Students were selected through a process whereby four schools from each of the cantons with at least three classrooms were randomly selected. This resulted in each school being represented in the study by three to four classrooms, resulting in a total of 43 classrooms. The first assessment was conducted at the beginning of grade seven. A total of 960 adolescents participated in the study. The numbers of participants were 834, 837, 882, and 859 at Time 1 (T1), T2, T3, and T4, respectively. At T3, two more classes were added to the study because the classes were reorganized in one school and previous participants were organized into classes that were not previously included in the assessments. Seven hundred and twenty five (75.5%) students participated in all four waves of assessment, while 72 (7.5%) participated in three, 136 (14.2%) in two, and 27 (2.8%) in one assessment. Attrition between the points of assessment was thus very low and was mainly due to participants relocating to another school. Accordingly, it was assumed that data were missing at random, and the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method was used to address missing data. To evaluate the extent to which the FIML procedure was appropriate for the longitudinal analyses at hand, we compared (a) the mean scores of depressive symptoms, victimization, friendship support, and parental support of participants with the complete data; (b) the same means scores that were obtained from the entire sample using the FIML method for the imputation of missing values. Results showed that means scores were almost identical for all pairs of means scores, suggesting that the FIML procedure was indeed well suited. Girls made up 49% of the sample in each stage of assessment. At the first assessment, the mean age of the participants was 13.2 years (SD = 0.59 years, min. = 11.1 years, max. = 15.3 years).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using a depressive mood scale (Alsaker 1992). The scale consisted of eight items and the three most representative items (i.e., those three with the highest loadings over time) were selected for the analyses. A rationale for the selection of these items is outlined in the analysis strategy section below. These were “Sometimes I think everything is so hopeless that I do not feel like doing anything,” “I think my life is kind of sad,” and “I think my life is not worth living.” Items were rated with respect to the last two weeks on a Likert scale from 1 (not true) to 4 (true). Alsaker (1992) reported Cronbach’s alpha as 0.87 for the complete scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the selected three items was (αT1/T2/T3/T4 = .80/.80/.80/.82).

Peer victimization

Peer victimization was assessed using a six-item bullying scale encompassing various aggressive behaviors (Alsaker 2003). As the original scale was developed to assess peer victimization among children, the wording of the items was slightly adapted to be more appropriate for adolescents. Again, the three most representative items were selected for the analyses, namely “Has anybody threatened you or forced you to do something?”, “Has anybody hit you, tripped you up, or hurt you in any way?”, and “Has anybody said bad things about you (e.g. spreading rumors)”. Items were rated with respect to the last four months on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). In this longitudinal study, the Cronbach’s Alpha was αT1/T2/T3/T4 = .80/.80/.83/.74.

Perceived parental and friendship support

To assess social support, we used selected items from the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA: Armsden and Greenberg 1987, 1989). The IPPA was developed to assess adolescents’ perceptions of relationships with their parents and close friends, particularly how well these figures serve as sources of psychological security (Armsden and Greenberg 1987). Due to limited time resources for our assessment, two items from the communication and three items from the trust subscale were included in the questionnaire. Studies have shown that trust and communication are highly correlated and that this measure is strongly associated with social support measures (Guarnieri et al. 2010). These items measure adolescents’ perception of parental and friendship support and were selected because they fitted best with our conceptual framework (Davies and Sturge-Apple 2014).

Again, for the final analyses, three items were selected for parental support: “My parents understand me,” “I trust my parents,” and “My parents can tell when I’m upset about something.” Likewise, three items were selected for friendship support: “My friends accept me as I am,” “I trust my friends,” “My friends understand me.” Participants rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (not true) to 4 (true). The reliability of the three selected items for parental support across four-time period was αT1/T2/T3/T4 = .80/.80/.87/.87. Cronbach’s Alpha for friendship support was αT1/T2/T3/T4 = .82/.84/.88/.90.

Analysis Strategy

Due to complexity of the longitudinal model and to our analysis strategy a reduction in the number of items per construct was necessary. Thus, every latent variable was modeled using as measurement model with three indicators (i.e., a just-identified measurement model). To this end, the three most representative items were selected for each scale using the following procedure: All univariate latent state models were ran with all items first and then with the three items with the best factor loadings over time, as the factor loading indicates their representativeness of the latent construct. This strategy ensured that no overestimation of model fit would occur (Little 2013), and at the same time allowed for a feasible modeling of latent interactions, which were consequently modeled with nine indicators (i.e., 3*3) instead of 30 indicators (i.e., 6*5).

The analyses of the current study were divided into two blocks. In the first block, four separate univariate latent state models were used to model the longitudinal development of victimization, parental support, friendship support, and depression, including tests towards measurement invariance. In the second block, the reciprocal associations between the constructs of interest were examined. In the first set of analyses, the associations between victimization, parental support, and depressive symptoms were examined, while in the second set, the associations between victimization, friendship support, and depressive symptoms were examined.

Nested data structure

The data that was collected in the present study had a nested data structure with four levels, namely Canton on level 4 (N = 3), schools on level 3 (N = 12), classrooms on level 2 (N = 45), and individuals on level 1 (N = 960). In order to take the nesting of individuals in classrooms into account, the sandwich estimator was used in Mplus. The Canton and the school levels were not accounted for, as the number of units of each one of these levels was insufficient.

Model identification and scaling

In line with guidelines provided by Little (2013), every latent variable was modeled using as measurement model with exactly three indicators (i.e., a just-identified measurement model)Footnote 1. The effect coding method was used to estimate the mean and the variance of the latent variables without over-representing an arbitrarily chosen indicator (Little 2013). The following model fit indices were used: The ratio between the chi-square (χ 2 ) and degrees of freedom (df), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

A latent state model (LSM) was constructed for each one of the four constructs separately. For each construct, the four measurement occasions were included in the LSM. Further, the unique variances of the indicators were correlated with the unique variances of the same indicator of different measurement occasions. No other unique variances were correlated. This model was labeled unconstrained model and was used a basis from which measurement invariance was tested (see Table 1).Footnote 2 Full Information Maximum Likelihood was used to address missing data issues under the assumption of missing at random.

Stationarity of effects

In a model with unstandardized latent variables, it is not possible to compare the stability of effects over time because variances might differ and, thus, covariances are rendered incomparable. To address this issue, so-called phantom variablesFootnote 3 can be used to standardize the latent variables (Little 2013). This standardization makes it possible to compare effects over time.Footnote 4

Trivariate cross-lagged model (TCLM)

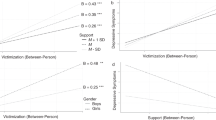

The univariate LSMs for victimization, parental support, and depressive symptoms were combined to a trivariate cross-lagged model (TCLM). It is important to highlight that there were differences in the time frame to which the questions about victimization (i.e., last four months), social support (i.e., unspecific), and depressive symptoms (i.e., past two weeks) referred. Thus, depressive symptoms were measured “after” victimization within each measurement occasion. To account for this lag, we adapted the TCLM in the following way: Depressive symptoms at each measurement occasion were predicted by victimization and social support (and their interaction; see below) of the same measurement occasion (see Fig. 1). The reciprocal associations between victimization and social support were modeled as usual in the cross-lagged model (see Fig. 1). Gender was included in all models as a time invariant covariate.

Structure of the trivariate cross-lagged model with latent interaction. Note that the variables depicted here represent latent phantom variables. Indicators, residual correlations, and correlations among interaction terms, and between interaction terms and other variables are not displayed. Vic.*Sup. interaction term between victimization and social support

The interactions of the effects of victimization and social support on depressive symptoms were modeled using Little et al. (2006) orthogonalizing approach, which consists in the creation of a latent interaction variable that can be used as a predictor to obtain results about the interaction effect.Footnote 5 Next, the depressive symptoms of all measurement occasions were additionally regressed on the interaction between victimization and parental support assessed at the same measurement occasion. Figure 1 displays the complete TCLM for victimization, social support, and depressive symptoms.

Results

Univariate Latent State Models for Victimization, Parental Support, Friendship Support, and Depressive Symptoms

The model fit indices for all univariate models for victimization including the various steps of the assessment of measurement invariance can be found in Table 1. The results suggested that all four constructs exhibited scalar measurement invariance. Thus, further longitudinal analyses were warranted (Table 2).

TCLM for Victimization, Parental Support, and Depressive Symptoms

The TCLM for victimization, parental support, and depressive symptoms was found to acceptably fit the data (χ 2 = 3680.710; df = 2375; CFI = .934; RMSEA = .025; SRMR = .050). Results are reported in Table 3. An examination of the stationarity (i.e., stability) of the effects over time was carried out next. In a first step, all autoregressive paths of victimization, parental support, and depressive symptoms were constrained to be equal over time. These constraints did not lead to deterioration in model fit (∆CFI = .000). In the following step, all cross-lagged effects and synchronous effects were constrained to be equal over time. Exceptions to these constraints were the synchronous effects at T1. These constraints also did not lead to a deterioration in model fit (∆CFI = .000). The resulting model was therefore accepted as final TCLM with latent interactions (χ 2 = 3700.564; df = 2395; CFI = .934; RMSEA = .025; SRMR = .051). The results from the TCLM (see Table 3) suggested that victimization and depressive symptoms had moderate relative stability, while parental support had a high relative stability. As for the cross-lagged effects, victimization and parental support were not found to be longitudinally associated. However, victimization was positively, and parental support was negatively predicted by depressive symptoms: The higher the depressive symptoms at a given time point, the more positive the change in victimization and the more negative the change in parental support six months later. Regarding the prediction of change in depressive symptoms, victimization was found to be positively, while parental support was found to be negatively associated with changes in depressive symptoms, with comparable effect sizes. Again, no significant interaction between victimization and parental support on changes in depressive symptoms was found. Thus, victimization was confirmed as a risk factor, and parental support was confirmed as a promotive factor for depressive symptoms. However, victimization and parental support were not found to interact with each other’s effect on depressive symptoms and change thereof.

TCLM for Victimization, Friendship Support, and Depressive Symptoms

The TCLM for victimization, friendship support, and depressive symptoms was found to fit the data very well (χ 2 = 2944.361; df = 2375; CFI = .972; RMSEA = .016; SRMR = .045). Results are reported in Table 4. In line with the model for parental support, an examination of the stationarity was carried out, and results showed that there was no relevant reduction in model fit (∆CFI = −.001). The resulting model was therefore accepted as final TCLM with latent interactions (χ 2 = 2980.799; df = 2395; CFI = .971; RMSEA = .016; SRMR = .046). The results from the final TCLM (see Table 4) were very similar to those obtained in the model with victimization, parental support, and depressive symptoms: Victimization, friendship support, and depressive symptoms were found to have a moderate relative stability. As for the cross-lagged effects, victimization and friendship support were not found to be longitudinally associated. However, victimization was positively and friendship support was negatively predicted by depressive symptoms. Regarding the prediction of change in depressive symptoms, victimization was found to be positively, while friendship support was found to be negatively associated with changes in depressive symptoms, with comparable effect sizes. Again, no significant interaction between victimization and friendship support on changes in depressive symptoms was found. Thus, victimization was confirmed as a risk factor, and friendship support was confirmed as a promotive factor for depressive symptoms. However, victimization and friendship support was not found to interact with each other’s effect on depressive symptoms and change thereof.

Discussion

Research on adolescents’ developmental outcomes has demonstrated that social support is a protective and promotive factor against life stressors. For instance, as a promotive factor social support is independently linked to the attenuation of depressive symptoms (Auerbach et al. 2011; Colarossi and Eccles 2003), and reduces the occurrence of victimization (Albayrak et al. 2014; Sapouna and Wolke 2013). Concerning the protective role of social support, it has been found to reduce the negative effect of the association between victimization and depressive symptoms (Desjardins and Leadbeater 2011; Tanigawa et al. 2011). Despite the strong evidence of the positive influence of social support, there has not been sufficient longitudinal studies on the protective and promotive effects of concurrent sources of social support on depressive symptoms and victimization. This study bridges the gap by examining effects of parental and friendship support on the longitudinal relationship between victimization and depressive symptoms.

Consistent with our hypotheses, the longitudinal association between victimization and depressive symptoms was found to be bidirectional and positive (Bogart et al. 2014; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2010; Kendrick et al. 2012; Reijntjes et al. 2010). This result suggests that the two constructs are associated with a higher likelihood of increases in the occurrence of the respective other. Therefore, adolescents experiencing either life stressor are susceptible to the other (Klomek et al. 2008; Sweeting et al. 2006). Further, we were able to show that this reciprocal association was stable over time during the observed time period of 18 months in early adolescence. These results indicate that a vicious circle might arise over time. This finding contributes to our understanding to peer victimization as a self-reinforcing dynamic that is hard to stop without help from others.

Parental Support and Depressive Symptoms

There was a negative and bidirectional longitudinal relationship between parental support and depressive symptoms such that high levels of perceived parental support resulted in more negative changes in depressive symptoms and vice versa. The findings provide support for previous research on parents’ responses to the emergence of adolescence (Auerbach et al. 2011; Chirkov and Ryan 2001; Collins and Laursen 2004). This study contributes to the existing literature by confirming the importance of parental emotional support in fostering healthy development in adolescents. Although parents may have given their children more autonomy and independence as they transitioned into adolescence, parents may have maintained a strong emotional connection with their children, which promotes their psychological well-being. Moreover, parents’ effort to keep an emotional connection with adolescents may result in adolescents feeling comfortable to share the experiences that made them susceptible to depressive symptoms compared to adolescents who do not have a strong emotional connection with their parents (Field et al. 2002). Future studies must, therefore, consider investigating the type and level of self-disclosure adolescents have with their parents to better determine whether that plays a role in reducing depressive symptoms.

Although we found that parental support is promotive for adolescents’ well-being, our analyses indicated that parental support did not moderate the effect of victimization on the changes in depressive symptoms. There are several potential explanations for these results. Previous research on the longitudinal effect of parental support found mixed results such that fathers’ emotional support was only effective at reducing depressive symptoms, while mothers’ emotional support moderates the relationship between physical victimization and depressive symptoms (Yeung and Leadbeater 2010). Elsewhere, however, fathers’ emotional support was found to be associated with increasing effects of victimization on internalizing problems (not necessarily depressive symptoms) in early adolescent males, but the support acted as a buffer in late adolescence (Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater 2013). Father support has also been found to be ineffective when fathers were psychologically controlling (Bean et al. 2006). The difference between our findings and Yeung-Thompson and Leadbeater’ results (2010, 2013) may be related to the fact that their studies focused on general emotional and behavioral outcomes instead of depressive symptoms and they controlled for parent gender.

In another study, parental support was a longitudinally effective moderator between peer stressors and depressive symptoms. The stressors, however, were general peer stressors such as peer conflict, feeling pressured, or experiencing criticism (Hazel et al. 2014). These stressors can be a normal part of adolescent development and may not have the same debilitating effects of repeated victimization. Our study contributes to the literature by highlighting that parental support does not moderate cases of chronic life experiences. One possible explanation is that some parents may be over-supportive of their children, which may be sufficient for general stressors but hinders the development of necessary skills needed by victims to reduce victimized experiences and depressive symptoms (Accordino and Accordino 2011). Furthermore, our results and the mixed findings in other studies suggest that more investigation needs to be done to understand the complexity of the effect of parental support on life stressors such as victimization. Additionally, future research may want to consider the influence of social support from other family members such as siblings who may be closer in age to the victim and are better able to understand the experiences of the victims. For example, research has shown that sibling support longitudinally acts as a protective factor against stressful life events and also acts as a moderator between those life events and internalization problems (Gass et al. 2007). The same may be true for prolonged episodes of victimization and depressive symptoms.

Friendship Support and Depressive Symptoms

In the present study, friendship support and depressive symptoms were found to be negatively and reciprocally associated with changes in each other. This suggests that adolescents who received emotional support from their peers were less prone to develop depressive symptoms, which supports findings of earlier studies (Du et al. 2015; Heaven et al. 2004; Sheeber et al. 2007). Moreover, our results also suggested that adolescents who suffer from depressive symptoms reported a decrease of friendship support over time. There are several reasons why friendship support may have had an influence in reducing depressive symptoms. The adolescent developmental period is a time in which peer relations become increasingly important. When there is strong friendship support adolescents’ self-esteem, and relationship satisfaction are positively impacted (Bukowski et al. 1998; Vitaro et al. 2009). These, in turn, protects against depressive symptoms (Litwack et al. 2010). Furthermore, the companionship that is found in friendships and exposure to peers who think positively of themselves may reduce depressive symptoms (Kiuru et al. 2012).

We found that friendship support is a promotive factor for adolescents’ well-being, but it does not seem to protect victims from negative outcomes of peer victimization. There are several potential explanations for these results. For instance, there is a possibility that victimization and depressive symptoms were already in a chronic stage, rendering friendship support an ineffective resource. As for friendship support as a moderator, future studies might want to focus on shorter time frames to shed light on micro processes within individuals. Also, the friends from whom adolescents received emotional support may have played a role in their ability to overcome victimization and depressive symptoms. Previous longitudinal and cross-sectional research on friendships have been mixed. Some researchers have found that best friend relationships attenuated victimization experiences (Bollmer et al. 2005; Hodges et al. 1999), which suggests that friendship support is an important resource, but best friend support is most effective. Other researchers have found that friendship support from general friends had a stronger inverse effect on depressive symptoms than support from close friends, as they provided greater predictability of the general environment and stability over time (Durlak et al. 2011; Rueger et al. 2016). The mixed findings suggest that friendship support from general friends and close friends may have different benefits and implications when investigating victimization and depressive symptoms, which future research needs to consider and differentiate.

Another explanation for the lack of moderation effect is the differences between how boys and girls experience and perceive support and victimization. When gender is considered regarding support, the literature demonstrates that girls reported more incidences of perceived support (Colarossi and Eccles 2003). Also, empirical research has found that girls’ interpersonal behaviors make them more open to emotional support. These behaviors include greater self-disclosure, more commitment to maintaining relationships and stronger interpersonal engagements (Rueger et al. 2016). The differences in the ways girls and boys experienced support may have influenced the findings. Regarding victimization, the literature highlights that girls and boys experience different forms of victimization that may influence the moderating effect of support. Boys are more likely to experience physical victimization compared to girls who are more susceptible to relational victimization, and experience more episodes of victimization in general. When comparisons are made between physical and relational victimization, relational victimization was found to be more salient during the adolescent period (Brown and Larson 2009; Crick et al. 1996). The effects on the type of victimization may have resulted in the need for different forms of support instead of solely emotional support.

Social Support and Victimization

Finally, we investigated whether social support can reduce adolescents’ victimization experiences. The findings indicated that parental support did not reduce, nor increase the occurrence of victimization and vice versa. This finding is contrary to Machmutow and colleagues’ (2012) findings that indicated that seeking support from family showed a significant buffering effect against victimization. One possible explanation for the differences may be related to adolescents’ perception of the effectiveness of parents’ intervention. Adolescents may perceive parents’ help or advice on how to stop victimization as ineffective or detrimental, because parents may not be able to fully understand the victimizing circumstances/culture (Dehue et al. 2008). Moreover, parental involvement may exacerbate the situation by leading to retaliation or other forms of repercussion from bullies (Accordino and Accordino 2011). Further, the increase in parent-child conflicts and misunderstandings that occur during adolescence (McGue et al. 2005) may have rendered parental support less effective at reducing victimization.

Likewise, friendship support did not have a longitudinal effect on victimization and vice versa. This finding did not confirm our hypotheses and is not in line with earlier research that found that adolescence period is one in which children build strong supportive friendships that should attenuate the negative effects of victimization (e.g., Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2010). The lack of effect of friendship support on victimization may be due to the fact that although adolescents may confide in and have good relations with their peers, the support may not be effective because peers are not skilled in assisting in the reduction of victimizing experiences (Hodges et al. 1999). The results may also be related to group similarity such that even though adolescents receive social support from peers, the support may be coming from friends who also experience similar forms of victimization, which limits the helpfulness of the relationship in combating victimization (Champion et al. 2003; Kiuru et al. 2012). It is also possible that friendship support did not influence victimization because of the possibility that the peers who were the bullies were also siblings of the victims. Tucker and colleagues (2013) study on sibling aggression found that sibling victimization is just as prevalent as other types of peer victimization. Therefore, if victims are being bullied by siblings it becomes even more difficult for friendship support to effectively reduce the incidences of victimization. Future research on peer victimization may want to more explicitly consider the role of aggressive behaviors by siblings on adolescents’ mental well-being.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study had several strengths. This study is one of the few to have investigated the longitudinal interplay among social support, depressive symptoms and victimization. Another strength was the large sample size. An important strength of the study was the low attrition rate for each assessment points. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this was one of the few studies to capitalize on the benefits of using trivariate cross-legged model (TCLM) to investigate the moderating effect of emotional support on the association between victimization and depressive symptoms. The benefit of TCLM model was that it allowed us to examine possible directions of effects and control for both temporal and cross-sectional effects.

Although there were strengths, the study also encountered several limitations. First, a methodological limitation was the reliance on solely student self-reports that may have resulted in an underreporting of victimization and depressive symptoms, to avoid stigmatization associated with being a victim. Moreover, victims with depressive symptoms are more susceptible to perceiving support from parents and friends as poor compared to non-victims (Branje et al. 2010), which may have adversely affected the association between the constructs. More confidence could have been established from the findings if there was a multi-informant approach. Second, the present study was limited in the use of the support scales for family and peers. The selected items only focused on the general concept of social support instead of specific forms of support (i.e. informational support), thus limiting our understanding of the effects of other forms of support. Third, the use of only a limited number of the original items on the support, victimization and depressive scales may have also adversely influenced the findings of the study. Finally, the lack of control of parents’ gender meant that it was not possible to determine the individual effects of maternal and paternal support.

Implications for Research and Practice

The findings from this study have important implications on intervention programs for adolescents experiencing victimization and depressive symptoms. The results indicate that parental and friendship support have an inverse association with depressive symptoms over time. Therefore, efforts should be made to ensure that prevention and intervention programs continue to work with families to improve parental support to combat depressive symptoms and victimization. These could include teaching parents how to be more responsive and connected to their children when they are experiencing difficulties. Additionally, it is recommended that parents are taught how to better understand adolescents’ perspective and the challenges they encounter with peers, which may be novel to parents because of the generational differences. In school, intervention programs should focus on skills to build and maintain strong relationships. Moreover, these programs may need to highlight to adolescents the signs of when their friends need emotional support and strategies they can use to support victims.

The current study suggests that the effects of parental and friendship support on victimization is complex. Future research is needed to clarify the longitudinal effects of parental support by gender on victimization and depressive symptoms. This will determine whether maternal or paternal support is most effective. Future research on friendship support also needs to focus on the type of friendship that is most effective at attenuating long-term victimization and depressive symptoms. The lack of moderation effect of social support confirms Malecki and Demaray’s (2003) argument that informational or instrumental support need to be considered when testing and providing intervention for adolescents who experience victimization. From a methodological point of view, studies using shorter time lags between the stressor and its outcome might be helpful to gain a picture of the associations at hand with a higher temporal resolution.

Conclusion

The present study expands our understanding of adolescence in several ways. First, the results suggested that peer victimization and depressive symptoms were positively and reciprocally associated over time, thereby indicating the potential for a vicious circle. In this regard, the results indicated that perceived parental and friendship support acted as promotive factors that longitudinally reduced the level of adolescents’ depressive symptoms. However, neither friendship nor parental support were found to be protective factors that buffered the longitudinal effect of peer victimization on depressive symptoms. Further, neither parental nor friendship support were found to reduce the occurrence of peer victimization. These findings indicated that although parental and friendship support promoted adolescents’ overall well-being (i.e., reduced depressive symptoms), both perceived parental and friendship support seemed to be ineffective in breaking the vicious cycle between peer victimization and depressive symptoms. One possible explanation for this pattern of results is that, if victimization is already in a chronic stage, perceived social support might be ineffective and other means might be needed to help victimized adolescents. In sum, the present results suggest that fostering perceived social support might be beneficial to all adolescents, while more specific intervention efforts are needed to break the vicious cycle between peer victimization and depressive symptoms.

Notes

This strategy avoids artificially inflated model fit indices that arise from the use of more than three indicators per latent variable.

In this regard, it is important to note that chi-square difference tests are very sensitive to sample size and make limited sense if used with a large sample such as the one of the present study (Cheung and Rensvold 2002; Little, 2013). Cheung and Rensvold (2002) concluded from their simulation study that deteriorations in CFI of up to 0.01 could be regarded as acceptable, and the more restrictive model should be preferred.

To facilitate the understanding and the interpretation of the results, these phantom variables were referenced as if they were the original latent variables in the following.

This procedure involves fixing the variances of the phantom variable at 1. While this works for exogenous variables (i.e., independent), fixing the residual variance of an endogenous variable (i.e., dependent) to 1 will cause estimation problems. This issue can be addressed by fixing the unstandardized residual variances at 1 and estimating the standardized residual variance in a first step. In a second step, these standardized residual variances can be used to replace the respective constraint on the unstandardized residual variances.

Latent interaction variables were allowed to correlate with all other phantom variables in the model except those that were assessed at the same measurement occasion.

References

Accordino, D. B., & Accordino, M. P. (2011). An exploratory study of face-to-face and cyberbullying in sixth grade students. American Secondary Education, 40(1), 14–30.

Albayrak, S., Biçer, S., & Aşık, E. (2014). The impact of the adolescent-parent relationship on peer victimization. The Journal of MacroTrends in Health and Medicine, 2(1), 1–9.

Alsaker, F. D. (1992). Pubertal timing, overweight, and psychological adjustment. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 12(4), 396–419. doi:10.1177/0272431692012004004.

Alsaker, F. D. (2003). Quälgeister und ihre Opfer: Mobbing unter Kindern–und wie man damit umgeht [Bullies and their victims: Bullying among children– and how to handle it]. Bern: Huber.

Alsaker, F. D. (2012). Mutig gegen Mobbing. Bern: Huber.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. doi:10.1007/BF02202939.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1989). Inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA). University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Auerbach, R. P., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Eberhart, N. K., Webb, C. A., & Ho, M. H. R. (2011). Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(4), 475–487. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x.

Bean, R. A., Barber, B. K., & Crane, D. R. (2006). Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: The relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. Journal of Family Issues, 27(10), 1335–1355. doi:10.1177/0192513X06289649.

Bogart, L. M., Elliott, M. N., Klein, D. J., Tortolero, S. R., Mrug, S., Peskin, M. F., Davies, S. L., Schink, E. T., & Schuster, M. A. (2014). Peer victimization in fifth grade and health in tenth grade. Pediatrics, 133(3), 440–447. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3510.

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need the role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(6), 701–712. doi:10.1177/0886260504272897.

Branje, S. J., Hale, W. W., Frijns, T., & Meeus, W. H. (2010). Longitudinal associations between perceived parent-child relationship quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 751–763. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9401-6.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3rd edn (pp. 74–103). New York: Wiley. Vol. 2 doi:10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002004.

Bukowski, W. M., Newcomb, A. F., & Hartup, W. W. (1998). The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Champion, K., Vernberg, E., & Shipman, K. (2003). Non-bullying victims of bullies: Aggression, social skills, and friendship characteristics. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(5), 535–551. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2003.08.003.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Chirkov, V. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russian and US adolescents’ common effects on well-being and academic motivation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 618–635. doi:10.1177/00220221010320050006.

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, S. E. Taylor & J. E. Springer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (pp. 253–267). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Pressman, S. (2004). Stress-buffering hypothesis. In N. B. Anderson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of health and behavior (pp. 780–782). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Vol. 2.

Colarossi, L. G., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research, 27(1), 19–30. doi:10.1093/swr/27.1.19.

Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2004). Parent-adolescent relationships and influences. In R. M. Lerner & L. D. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2nd edn (pp. 331–361). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Craig, W. M. (1998). The relationship among bullying, victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school children. Personality and Individual Differences, 24(1), 123–130. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00145-1.

Crick, N. R., Bigbee, M. A., & Howes, C. (1996). Gender differences in children’s normative beliefs about aggression: How do I hurt thee? Let me count the ways. Child Development, 67(3), 1003–1014. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01779.x.

Davidson, L. M., & Demaray, M. K. (2007). Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 383.

Davies, P. T., & Sturge-Apple, M. L. (2014). Family context in the development of psychopathology. In M. Lewis & K. D. Rudolph (Eds.), Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology (pp. 143–161). Boston, MA: Springer US. http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/10.1007/978-1-4614-9608-3_8 Retrieved from.

Dehue, F., Bolman, C., & Vollink, T. (2008). Cyberbullying: Youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(2), 217–223. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0008.

Denny, S., Fleming, T., Clark, T. C., & Wall, M. (2004). Emotional resilience: Risk and protective factors for depression among alternative education students in New Zealand. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(2), 137–149. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.137.

Desjardins, T. L., & Leadbeater, B. J. (2011). Relational victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Moderating effects of mother, father, and peer emotional support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 531–544. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9562-1.

Du, H., King, R. B., & Chu, S. K. (2015). Hope, social support, and depression among Hong Kong youth: Personal and relational self-esteem as mediators. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 2(8), 926–936. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1127397.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Field, T., Miguel, D., & Sanders, C. (2002). Adolescents’ parent and peer relationship. Adolescence, 37(145), 121–130.

Fox, C., & Boulton, M. (2005). The social skills problems of victims of bullying: Self, peer and teacher perceptions. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(2), 313–328. doi:10.1034/00070990525517.

Gass, K., Jenkins, J., & Dunn, J. (2007). Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(2), 167–175. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x.

Ge, X., Natsuaki, M. N., Neiderhiser, J. M., & Reiss, D. (2009). The longitudinal effects of stressful life events on adolescent depression are buffered by parent–child closeness. Development and Psychopathology, 21(02), 621–635. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000339.

Guarnieri, S., Ponti, L., & Tani, F. (2010). The inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA): A study on the validity of styles of adolescent attachment to parents and peers in an Italian sample. TPM-Testing. Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 17(3), 103–130.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta‐analytic review of cross‐sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00629.

Hazel, N. A., Oppenheimer, C. W., Technow, J. R., Young, J. F., & Hankin, B. L. (2014). Parent relationship quality buffers against the effect of peer stressors on depressive symptoms from middle childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 50(8), 2115–2013. doi:10.1037/a0037192.

Heaven, P. C. L., Newbury, K., & Mak, A. (2004). The impact of adolescent and parental characteristics on adolescents’ levels of delinquency and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 173–185. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00077-1.

Herman-Stahl, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1996). The protective role of coping and social resources for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(6), 733–753. doi:10.1007/BF01537451.

Hodges, E. V., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 94 doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94.

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2005). Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review, 34(3), 309–328.

Huang, H., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2013). Understanding factors associated with bullying and peer victimization in Chinese schools within ecological contexts. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(7), 881–892. doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9647-4.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Fröjd, S., & Marttunen, M. (2010). Involvement in bullying and depression in a 2-year follow-up in middle adolescence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(1), 45–55. doi:10.1007/s00787-009-0039-2.

Kendrick, K., Jutengren, G., & Stattin, H. (2012). The protective role of supportive friends against bullying perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 1069–1080. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.014.

Kiuru, N., Burk, W. J., Laursen, B., Nurmi, J. E., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2012). Is depression contagious? A test of alternative peer socialization mechanisms of depressive symptoms in adolescent peer networks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(3), 250–255. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.06.013.

Klima, T., & Repetti, R. L. (2008). Children’s peer relations and their psychological adjustment: Differences between close friendships and the larger peer group. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(2), 151–178.

Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., Kumpulainen, K., Piha, J., Tamminen, T., Moilanen, I., et al. (2008). Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. Journal of Affective Disorders, 109(1), 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226.

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1091–1108. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Little, T. D., Bovaird, J. A., & Widaman, K. F. (2006). On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling, 13(4), 497–519. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1304_1.

Litwack, S. D., Aikins, J. W., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2010). The distinct roles of sociometric and perceived popularity in friendship: Implications for adolescent depressive affect and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(2), 226–251. doi:10.1177/0272431610387142.

Machmutow, K., Perren, S., Sticca, F., & Alsaker, F. D. (2012). Peer victimisation and depressive symptoms: Can specific coping strategies buffer the negative impact of cybervictimisation? Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties, 17(3–4), 403–420.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576.

Masten, A. S., & Gewirtz, A. H. (2008). Vulnerability and resilience in early child development. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of early childhood development (pp. 22–43). Oxford: Blackwell.

McGue, M., Elkins, I., Walden, B., & Iacono, W. G. (2005). Perceptions of the parent-adolescent relationship: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 971–984. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.971.

Menesini, E., Modena, M., & Tani, F. (2009). Bullying and victimization in adolescence: Concurrent and stable roles and psychological health symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 170(2), 115–134. doi:10.3200/GNTP.170.2.115-134.

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B. L. (2004). Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta- analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 711–747. doi: http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711.

Monks, C. P., & Coyne, I. (2011). Bullying in different contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of American Medical Association, 285(16), 2094–2100.

Nikiforou, M., Georgiou, S. N., & Stavrinides, P. (2013). Attachment to parents and peers as a parameter of bullying and victimization. Journal of Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/484871

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Perren, S., & Alsaker, F. D. (2009). Depressive symptoms from kindergarten to early school age: Longitudinal associations with social skills deficits and peer victimization. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), 28 https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-28.

Perren, S., & Hornung, R. (2005). Bullying and delinquency in adolescence: Victims’ and perpetrators’ family and peer relations. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 64(1), 51–64. doi:10.1024/1421-0185.64.1.51.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(4), 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 47 doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. doi:10.1037/bul0000058.

Sapouna, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Resilience to bullying victimization: The role of individual, family and peer characteristics. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 997–1006. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.009.

Sarigiani, P. A., Heath, P. A., & Camarena, P. M. (2003). The significance of parental depressed mood for young adolescents’ emotional and family experiences. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 23(3), 241–267. doi:10.1177/0272431603254292.

Schmidt, M. E., & Bagwell, C. L. (2007). The protective role of friendships in overtly and relationally victimized boys and girls. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53(3), 439–460. doi:10.1353/mpq.2007.0021.

Schwartz, D., Farver, J. M., Chang, L., & Lee-Shin, Y. (2002). Victimization in South Korean children’s peer groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(2), 113–125. doi:10.1023/A:1014749131245.

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2015). Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 393–404. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.881293.

Sheeber, L. B., Davis, B., Leve, C., Hops, H., & Tildesley, E. (2007). Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: Associations with depressive disorder and sub-diagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 144–154. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144.

Slee, P. T. (1995). Peer victimization and its relationship to depression among Australian primary school students. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(1), 57–62. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)00114-8.

Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 147–154. doi: 0.1080/13632752.2012.704310.

Stadler, C., Feifel, J., Rohrmann, S., Vermeiren, R., & Poustka, F. (2010). Peer-victimization and mental health problems in adolescents: Are parental and school support protective? Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41(4), 371–386. doi:10.1007/s10578-010-0174-5.

Strohmeier, D., Kärnä, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). Intrapersonal and interpersonal risk factors for peer victimization in immigrant youth in Finland. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 248 doi:10.1037/a0020785.

Sweeting, H., Young, R., West, P., & Der, G. (2006). Peer victimization and depression in early-mid adolescence: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 577–594. doi:10.1348/000709905X49890.

Tanigawa, D., Furlong, M. J., Felix, E. D., & Sharkey, J. D. (2011). The protective role of perceived social support against the manifestation of depressive symptoms in peer victims. Journal of School Violence, 10(4), 393–412. doi:10.1080/15388220.2011.602614.

Townsend, L., Flisher, A. J., Chikobvu, P., Lombard, C., & King, G. (2008). The relationship between bullying behaviors and high school dropout in Cape Town, South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(1), 21–32.

Tucker, C. J., Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A. M., & Turner, H. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of sibling victimization types. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(4), 213–223. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.006.

Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., & Bukowski, W. M. (2009). The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 268–588). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

Williams, K., Chambers, M., Logan, S., & Robinson, D. (1996). Association of common health symptoms with bullying in primary school children. British Medical Journal, 313(7048), 17–19. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7048.17.

World Health Organization (2012). Risk behaviors: Being bullied and bullying others. In C. Currie, et al. (Eds.), Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health behavior to school-aged children (HSGC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/163857/Social-determinants-of-health-and-well-being-among-young-people.pdf?ua=1.

Yeung, R., & Leadbeater, B. (2010). Adults make a difference: The protective effects of parent and teacher emotional support on emotional and behavioral problems of peer‐victimized adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(1), 80–98. doi:10.1002/jcop.20353.

Yeung-Thompson, R. S., & Leadbeater, B. J. (2013). Peer victimization and internalizing symptoms from adolescence into young adulthood: Building strength through emotional support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 290–303. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00827.x.

Zimmerman, M. A., Ramirez-Valles, J., Zapert, K. M., & Maton, K. I. (2000). A longitudinal study of stress-buffering effects for urban African-American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 17–33. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200001)28:1<17::AID-JCOP4>3.0.CO;2-I.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF 100014_130193/1: Perren and Alsaker) and an international research exchange fellow stipend from the University of Konstanz to the first author. The authors wish to acknowledge the netTEEN staff involved in the survey, as well as the teachers and students who participated in the study.

Author Contributions

T.B. and F.B. shared in the conceptualization of the paper. T.B. composed the introduction and discussion sections and revised the draft versions of the manuscript. F.S. wrote the methods and results section, conducted the statistical analyses, interpreted the findings, and revised draft versions of the manuscript. S.P. conceptualized, planned and coordinated the research project, and revised draft versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the Swiss legislature’s ethical standards for research with human participants, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or ethical comparable standards. No ethical approval was required.

Informed Consent

Parents of participants were informed about the study. They were asked to inform the respective teachers in case they did not want their children to participate (passive-consent procedures). Participants were offered the opportunity to refrain from participation with no negative consequences (informed oral consent).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, T., Sticca, F. & Perren, S. Everything’s Gonna be Alright! The Longitudinal Interplay among Social Support, Peer Victimization, and Depressive Symptoms. J Youth Adolescence 46, 1999–2014 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0653-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0653-0