Abstract

Little is known about the associations between various types of childhood maltreatment and multiple forms of intimate partner violence victimization in early adulthood. This study examines the extent to which childhood experiences of maltreatment increase the risk for intimate partner violence victimization in early adulthood. Data for the present study are from 3322 young adults (55 % female) of the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy with the mean age of 20.6 years. The Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy is a prospective Australian pre-birth cohort study of mothers consecutively recruited during their first antenatal clinic visit at Brisbane’s Mater Hospital from 1981 through to 1983. Participants completed the Composite Abuse Scale at 21-year follow-up and linked this dataset to agency recorded substantiated cases of childhood maltreatment. In adjusted models, the odds of reporting emotional intimate partner violence victimization were 1.84, 2.64 and 3.19 times higher in physically abused, neglected and emotionally abused children, respectively. Similarly, the odds of physical intimate partner violence victimization were 1.76, 2.31, 2.74 and 2.76 times higher in those children who had experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect and emotional abuse, respectively. Harassment was 1.63 times higher in emotionally abused children. The odds of severe combined abuse were 3.97 and 4.62 times greater for emotionally abused and neglected children, respectively. The strongest associations involved reports of child emotional abuse and neglect and multiple forms of intimate partner violence victimization in young adulthood. Childhood maltreatment is a chronic adversity that is associated with specific and multiple forms of intimate partner violence victimization in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is a global public health problem (Mian 2004) associated with a number of adverse health consequences. Childhood maltreatment including sexual, physical and psychological abuse, and neglect (Leeb 2008) may be chronic (Widom et al. 2014) and lead to victimization (Messman-Moore and Long 2000) to multiple forms of intimate partner violence (Widom et al. 2008). These consequences include sexual (Noll et al. 2003), physical (Messman-Moore and Long 2003) and psychological (Messman-Moore and Long 2000) violence, and neglect (Widom et al. 2008) into adulthood. Despite these consequences, little is known about the effects of different forms of childhood maltreatment, particularly emotional abuse and neglect, on intimate partner violence victimization especially in early adulthood.

A number of life time exposures including witnessing domestic violence have been associated with intimate partner violence victimization (Swartout et al. 2012). One area in which there has been less information is the link between an early life course history of childhood maltreatment and subsequent intimate partner violence victimization, although a handful of cross-sectional studies suggest there may be an association (Desai et al. 2002). Experiencing child sexual abuse, for instance, is associated with a twofold greater likelihood of subsequent lifetime intimate partner violence overall, while childhood physical and sexual abuse together have been associated with a sevenfold increased risk of lifetime physical and sexual intimate partner violence (Barrios et al. 2015). Similarly, another study reported a greater tendency for lifetime physical and sexual violence (Desai et al. 2002) and later intimate partner violence victimization (Krug et al. 2002) in males and females who had experienced childhood maltreatment.

These cross-sectional findings are confirmed by longitudinal studies (Widom et al. 2014; Widom et al. 2008). Those exposed to early experiences of physical and sexual assault or abuse, kidnaping or stalking, and having a family or friend murdered or who committed suicide are likely to report later intimate partner violence victimization. Physical abuse (Fry et al. 2012), sexual abuse, neglect (Widom et al. 2008) and overall childhood maltreatment (Widom et al. 2014) are associated with high risk of later sexual violence (Fang and Corso 2007) and lifetime intimate partner violence victimization (Ehrensaft et al. 2003). In one study, the impact of child physical abuse on intimate partner violence victimization in females (Herrenkohl et al. 2004) was mediated by the quality of the relationship, as measured by the strength of attachment to one’s partner. Further, findings from the literature (Rumstein-McKean and Hunsley 2001) and systematic (Fry et al. 2012) reviews have suggested that female sexual abuse survivors may experience more relationship problems and sexual dysfunction that may possibly lead to subsequent intimate partner violence victimization.

Children who have been maltreated experience a range of mental health problems (Mills et al. 2013) which, in turn, may lead to being a victim or perpetrator (or both) of intimate partner violence. For instance, findings from high school and child protective services samples (Lang et al. 2004) show that posttraumatic stress disorder may increase withdrawal from normal interactions possibly leading to hypervigilance (Wekerle et al. 2001) that might increase the tendency for the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Moreover, exposure to childhood maltreatment may lead to mental illnesses (González et al. 2016) including depression (Afifi et al., 2014), anxiety and dissociation (Lang et al. 2004), and being a subsequent victim of intimate partner violence (Lang et al. 2004) particularly for those poly-victimized in childhood (Finkelhor et al. 2007) and admitted for drug treatment (El-Bassel et al. 2005). Early onset aggressive behavior (Herrenkohl et al. 2004) and alcohol (Widom et al. 2006) may also be associated with both exposure to childhood maltreatment and later involvement in intimate partner violence experiences. There is, however, a possibility that parental social disadvantage including family violence and instability (Sabri et al. 2013) chronic maternal stress and negative life events (Messman-Moore and Long 2003) may confound early adversity and later intimate partner violence experiences and other adverse outcomes.

Though the mechanisms remain a matter of debate, intimate partner violence victimization in adults tends to be greater among those who have been maltreated during their childhood (Banyard et al. 2000). A number of potential mechanisms may account for this association. Socioeconomic disadvantage including poverty, family instability and conflict, maternal poor mental health, early problem behaviors in children and neighborhood poverty may be associated with both childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization (Gewirtz and Edleson 2007). For example, some studies suggest that both exposure to childhood maltreatment and experiencing intimate partner violence share multiple risk factors including poverty, marital conflict, neighborhood violence (Herrenkohl et al. 2008) and family mental illness (Dong et al. 2004), particularly maternal stress (Margolin et al. 2003). Maternal relationship instability (Ackerman et al. 2002) and poor mental health (M. R. Holmes 2013) are also associated with child externalizing problems (Ackerman et al. 2002) including aggression (M. R. Holmes 2013), which, in turn, are associated with childhood maltreatment (Eckenrode et al. 2001) and intimate partner violence (Whitfield et al. 2003). This suggests that externalizing problems (Arata et al. 2007) resulting from childhood maltreatment may operate through violent behavior at early ages (Deborah 2013) leading to an increased risk of perpetration of and/or victimization to intimate partner violence. Moreover, the experience of posttraumatic stress disorder or disrupted relationships among those who have experienced childhood maltreatment may also affect self-image (Campbell et al. 2008) resulting in an inability to develop skills to regulate emotions and form lasting relationships with other people. This perhaps might result from poor behavioral control in those who were the victims of childhood maltreatment involving patterns of vulnerability and a general mistrust of others (Kim and Cicchetti 2010). Finally, neighborhood factors may operate via social disorganization and collective efficacy (Coulton et al. 2007) that may increase the likelihood of victimization to childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence.

From the perspectives of social learning (Bandura and Walters 1977) and learned helplessness (Stith et al. 2004), maltreated children may learn either to be perpetrators or victims (Stith et al. 2004) of violence in later stages of their lives. For example, childhood maltreatment and family violence may coexist (Herrenkohl et al. 2008) leading to poor psychosocial outcomes for children (Kitzmann et al. 2003) including intimate partner violence. Those young adults who were maltreated during their childhood may also accept violence as an expected aspect or component of their adult relationships (Wyatt et al. 2000). Being a perpetrator and/or victim of intimate partner violence may also be considered a “learned” coercive conflict resolution mechanism and generalized from the parent–or caregiver-child relationship to the intimate partner relationship (Ehrensaft et al. 2003). Indeed, the ecological/transactional model (Cicchetti and Valentino 2006) suggests that aforementioned factors at individual, family and environment levels may affect victimization to both childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence. Notwithstanding, only a few studies adjust for the aforementioned factors (Korbin and Krugman 2014).

There are some important limitations associated with prior studies of the association between both victimization to childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence. These include the use of unstandardized self-report measures (Wekerle et al. 2001) of childhood maltreatment experiences that overlook multiple forms of maltreatment (Widom et al. 2014) from socially disadvantaged minorities (Messman-Moore and Long 2000). Reporting and recall bias (Stevens et al. 2005) may therefore affect previous findings (Herrera and McCloskey 2003), as well as limiting generalizability (Barrios et al. 2015). For instance, a recent systematic review (Capaldi et al. 2012) reported inconsistent associations between early childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence victimization. Some studies focus on sexually (Davis and Petretic-Jackson 2000) and physically (Herrenkohl et al. 2004) abused children and measure later intimate partner violence victimization using non-validated tools in adolescent (Gómez 2010) or late adult (Davis and Petretic-Jackson 2000) populations who have mental health disorders including posttraumatic stress disorder (Widom et al. 2004). The findings of these latter studies may be confounded by other developmental or lifetime events. Few, if any of these studies have investigated the impact of a range of possible types of substantiated childhood maltreatment on later intimate partner violence victimization (Finkelhor et al. 2007) adjusting for both individual and familial (Widom et al. 2014). Finally, none of these studies have examined the association between distinct types of substantiated childhood maltreatment and victimization to different forms of intimate partner violence in young adults.

The Current Study

Little is known about the extent to which experiencing multiple forms of substantiated childhood maltreatment increases the risk for intimate partner poly-victimization in early adulthood controlling for potential confounders. In view of these limitations, several researchers have recommended the need for studies that use representative samples, standardized and psychometrically strong measures (Rumstein-McKean and Hunsley 2001) with sufficient control for potential confounders and attention to possible gender differences in outcomes (Desai et al. 2002). Data for childhood maltreatment were substantiated for the childhood period. This study examines whether distinct types of childhood maltreatment differentially predict different forms of intimate partner violence victimization controlling for sex at birth and adolescence, early adulthood and familial confounders. Data on childhood maltreatment, maternal social and mental health from pregnancy to the age of 14 years and concurrent socio-demographic characteristics of the youth at 21 years enables us to explore more systematically the association between victimization to childhood maltreatment and adulthood intimate partner violence victimization.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

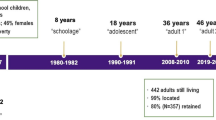

The study takes data from the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, a prospective Australian pre-birth cohort of mothers and their children, recruited consecutively during their first antenatal clinic visit from 1981 through to 1983 at Brisbane’s Mater Hospital. Since then, the study has followed mother-child pairs until when the children reached 21 years of age. Details on the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy are found elsewhere (Najman et al. 2015). The Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study has previously linked this dataset to substantiated cases of child maltreatment reported to the appropriate government agency up to the age of 14 years. For this study, we have extended the linkage of this dataset to the 21-year follow-up which includes details of intimate partner violence victimization. The sample was restricted to those young adults who had had partners and reported details of possible intimate partner violence victimization at the 21-year follow-up (n = 3322). Females comprised 55 % of respondents and the mean age of participants was 20.6 ranging from 19–22 years.

Measures

Substantiated childhood maltreatment

Suspected cases of child maltreatment were identified from state-wide child protection records. Notifications of maltreatment include mandatory reports from medical practitioners and referrals received from the general public. In this birth cohort (n = 7223), there have been 789 (11 %) notifications for any maltreatment, of which 663 and 500 are for abuse and neglect, respectively, after excluding 9 participants for which child protection data were not available. Reports are screened by the Department of Families, Youth and Community Care, Queensland. Substantiated cases of maltreatment include those cases confirmed by the Department of Families, Youth and Community Care, Queensland with evidence of “reasonable cause to believe that the child had been, was being, or was likely to be abused or neglected.” The definition of sexual abuse includes exposing a child to or involving a child in inappropriate sexual activities Physical abuse is defined as any non-accidental physical injury inflicted by a person who had to take care of the child. Emotional abuse includes any act resulting in a child suffering any kind of emotional deprivation or trauma. Finally, childhood neglect is defined as a “failure to provide conditions that were essential for the healthy physical and emotional development of a child.” Childhood experiences of “neglect” were intended to incorporate both physical and emotional neglect by those who were taking care of a child [Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision (SCRCSSP 2000)]. Queensland government child protection agency workers determined substantiations of child maltreatment. Data were confidentially and anonymously linked to the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy longitudinal database in September 2000. Details are presented elsewhere (Strathearn et al. 2009). In this study, substantiated cases of child maltreatment were restricted to 0–14 years of age, of which 55.8 % females had experienced any substantiated maltreatment. Specific categories of child maltreatment were any substantiated maltreatment, substantiated sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect. This classification appears to have greater predictive validity (Lau et al. 2005).

Intimate partner violence victimization

Intimate partner violence victimization was assessed using 30 items (α = .95) from the revised composite abuse scale (Hegarty et al. 2005). Participants were asked how often they had experienced violence in their relationship with a partner (in either current or previous relationships) followed by types of intimate partner violence. Each item has 7 response options for describing their abuse experience including no partner/never/only once/several times/once per month/once per week/daily. For this study we used 22 items (α = .95) that matched the validated version (Hegarty and Valpied 2013) (Appendix). Regardless of the number of items included, inter-item correlations remained similar. These included 11 items (α = .91) for emotional intimate partner violence (total score: 0–55), 5 items (α = .93) for physical intimate partner violence (total score: 0–25), 4 items (α = .83) for harassment (total score: 0–20) and 2 items (α = .62) for severe combined abuse (total score: 0–10) based on the validated version of the Composite Abuse Scale and recoded these as never = 0/only once = 1/several times = 2/once per month = 3/once per week = 4/daily = 5. The composite abuse scale reliably measures types and severity of intimate partner violence victimization and has been validated for concurrent validity using a community-based sample (Deborah 2013). Frequencies of each form of intimate partner violence victimization were summed to yield the total score. Finally, four composite indices of intimate partner violence victimization (i.e., emotional intimate partner violence, physical intimate partner violence, harassment and severe combined abuse) were then generated based on recommended cut-off scores for each subscale (i.e., ≥3 emotional intimate partner violence victimization, ≥1 physical intimate partner violence victimization, ≥2 harassment and ≥1 severe combined abuse) to examine individual effects of childhood maltreatment on each intimate partner violence victimization form. Frequencies were recoded to create a composite variable with three categories: never, only once and more than once to describe the frequency of intimate partner violence victimization.

Socio-demographic characteristics of young adults

The dataset included information about the following socio-demographic characteristics: sex at birth, receipt of social security benefits, educational level, marital status and residential problem area at 21-year.

Social deprivation of young adults

The study also assessed social deprivation by asking if any of the following were problems in the area where they lived: vandalism/graffiti, house burglaries, car stealing, violence in the streets, unemployment, noisy and/or reckless driving, alcohol and drug abuse and school truancy. These were assessed using 9 items (α = .81) rated on five point Likert scales and a 10 % cut-off was considered to be a “high” problem area.

Aggressive behavior at 14-year

The frequency of aggressive behavior for the last one year was assessed using mothers’ reports on 10 items (α = .85) from child behavior checklist aggression short form (Achenbach 1991) at 14-year. Mothers were asked how often their child had had a problem in the last year. Responses were rated and recoded as never = 1/sometimes = 2/often = 3/. Responses to each item were summed and the top 10 % cut-off was used as a “case” based on the relevant scale (Achenbach and Edelbrock 1983). There is some evidence to support the validity of the child behavior checklist in school aged children of different settings (Bordin et al. 2013). This variable was dichotomised as normal and aggressive and included in the analyses to test the possibility that for whether early aggressive behavior is associated with child maltreatment and later involvement in intimate partner violence victimization (White and Widom 2003).

Maternal socio-demographic characteristics

The analyses included five maternal socio-demographic characteristics as reported by mothers from pregnancy through to when the child was 14 years old. Firstly, their income was measured from pregnancy through to 5 years (4 follow-ups). The mean income of each phase was taken and those mothers whose income was consistently below the poverty line over the first 5 years were coded as consistent poverty, otherwise mid-to-high income. These thresholds were based on estimates of the poverty level from 1981–1983 (Najman et al. 2004). Then, marital stability was assessed by whether mothers had the same partner at 14-year as they had at the birth of the child.

Maternal stress

Maternal perceived stress (Reeder et al. 1973) from pregnancy through to 6 months was assessed using 4 items (α = .79, .83 and .84 for prenatal, postnatal and 6-month follow-up, respectively) that assessed nervousness, stressful activities and mental and physical exhaustion and found to have good constructive validity (Metcalfe et al. 2003). Items were rated as never = 0; rarely = 1; some of the time = 2; most of the time = 3; and all the time = 4. Prenatal, postnatal and 6-month stress scores were added to provide a score of 0–16. A composite variable for chronic stress was dichotomised as nil (0–6 symptoms score) and stress (7–16 symptoms score).

Maternal negative life events

Mothers’ negative life events from birth of the child until when he/she became 5 years of age, were assessed using 9 items of the life events scale (Holmes and Rahe 1967) that ranged from 0 (no events) to 5 (life events for the last 5 years) at the 5-year follow-up. Negative life events included physical illness and various socio-economic troubles. These items were summed to give a total score ranging from 0 to 45. Those mothers who reported 0 to 3 and 4+ life events were recoded having had ‘nil’ and ‘many’ negative life events, respectively.

Family violence

Violence in the home was assessed at 14-year follow-up using the modified conflict tactics scale (Straus 1979). This has 7 items (α = .69) asking whether disagreements at home were resolved with violent actions, items being recoded as never = 1; sometimes = 2; and often = 3. Scores were summed to provide a composite variable where higher scores represented increased violence (low = 1–15.9 vs. high = 16–21). The test re-test reliability of this scale has been found to be consistent (Vega and O’Leary 2007).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including percentage distributions and Pearson’s χ2 statistics were used to describe sociodemographic characteristics that were associated with each type of child maltreatment. Four separate sets of bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models, in which all relevant variables entered at one stage, were then used to obtain the maximum likelihood estimates of the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals (ORs; 95 % CIs). The maximum likelihood ratio was used to test for model fit and significance. Firstly, bivariate analyses for each predictor and confounder variable against each outcome measure were derived. Secondly, multivariable logistic regression models were calculated adjusting for 11 confounders to determine the independent effect of each predictor and confounder variable across four forms of intimate partner violence victimization. Further, sensitivity analyses of associations between any child maltreatment notifications and multiple forms of intimate partner violence victimization were examined adjusting for all selected confounders by repeating the same models to determine the independent effects of each child maltreatment type on intimate partner violence victimization.

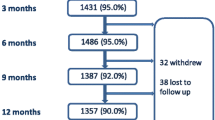

Attrition

To account for attrition, the investigators carried out weighted analyses using inverse probability weighting (Hogan et al. 2004) in three steps. Firstly, unadjusted logistic regression analyses of selected confounders against attrition as an outcome (non-missing vs. missing) were undertaken to identify those variables associated with higher rates of attrition. Secondly, multivariable logistic regression analysis was undertaken to determine independent predictors of attrition and to generate weights for each variable involved in the study. Thirdly, the final fully adjusted model including the weighted variable was repeated to determine whether attrition has affected the findings. Statistical analyses were done using STATA version 13 (StataCorp LP: College Station, Texas, 2015) and SPSS (IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, 2013) for windows setting the level of significance at p-value of .05.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the variables included in the study are provided in Table 1. The present study included 3322 participants who had complete data at 21-year follow-up. The number of participants differed slightly across variables because of missing values. In bivariate analyses of attrition, receiving benefits, residential problem area, aggressive behavior at 14-year, mother’s income, chronic stress, more negative life events and violence in the home at 14-year were all associated with attrition. Only gender maintained statistically significant association with attrition in the adjusted analysis (data not shown).

Of the 3322 participants included in the study, 156 (5 %) individuals had experienced substantiated childhood maltreatment. Substantiation of maltreatment appeared to be disproportionately reported by those who were receiving social benefits. Those individuals who had incomplete secondary school and who were divorced appeared to report higher rates of substantiated maltreatment. Moreover, those who were reported to exihibit aggressive behavior at 14-year more often experienced maltreatment. Those young adults whose mothers met the criteria for chronic poverty, reported marital instability, and who had experienced stress and negative life events, were more likely to experience maltreatment (Table 2).

The overall prevalence of physical intimate partner violence victimization, emotional intimate partner violence victimization, harassment and severe combined abuse was 39.4, 32.9, 24.5 and 5.9 %, respectively. Of these, 52.1 % of the respondents reported experiencing intimate partner violence more than once (Table 1) and 4 % had experienced overlapping victimization to all types of violence. Female participants, those who were on social benefits, were divorced, reported living in residential problem areas or experienced aggressive behavior at 14-year were more likely to have experienced intimate partner violence. Those young adults with mothers who had experienced maternal marital instability up to the 14-year follow-up and who had reported more negative life events also reported a higher risk of experiencing later intimate partner violence. However, those living in families with more consistent poverty and stress over the first five years of life and who had experienced violence in the home at 14-year follow-up did not show any significant associations with intimate partner violence victimization (data not shown).

Table 3 presents the bivariate associations between various forms of child maltreatment and experiences of intimate partner violence victimization at the 21-year follow-up. All forms of child maltreatment were consistently associated with subsequent intimate partner violence victimization. For the “any substantiated maltreatment” category percentages of subsequent intimate partner violence victimization are about twice those of children not experiencing maltreatment (Table 3).

Table 4 presents the unadjusted and adjusted associations between substantiated reports of child maltreatment and subsequent experience of intimate partner violence. Respondents who experienced any form of maltreatment were more likely to report that emotional and/or physical intimate partner violence was a characteristic of their current relationship. This remained the case after adjustment for a wide range of potential confounders, with the exception of sexual abuse where the associations were no longer significant. Some forms of child maltreatment were more strongly related to intimate partner violence victimization. In particular, substantiated child emotional abuse and neglect were very strong predictors of nearly all forms of intimate partner violence victimization in young adulthood. In further analyses, any substantiated child maltreatment notifications were significantly and consistently associated with subsequent intimate partner violence victimization except for harassment where associations were slightly modified in adjusted models (Table 4). Sensitivity analyses using only notified reports of child maltreatment across all forms of intimate partner violence victimization revealed consistent findings as that of substantiated cases (data not shown). The findings remained robust and consistent after adjustment for the weighted data.

Discussion

Childhood maltreatment has been found to lead to later problem behaviors including aggression (Auslander et al. 2016) and intimate partner violence victimization (Widom et al. 2014). Notwithstanding, the health consequences of victimization to multiple forms of childhood maltreatment (Finkelhor et al. 2007) especially for early adulthood occurring and overlapping forms of intimate partner violence victimization have been neglected. Furthermore, prior literature has been largely based on retrospective reports of exposure to childhood maltreatment (Stevens et al. 2005) from preselected samples of socially disadvantaged minorities (Messman-Moore and Long 2000) with posttraumatic stress disorder (Widom et al. 2004) and failed to control for potential individual, familial and environmental level confounders (Widom et al. 2014) limiting reliability and validity (Barrios et al. 2015). The current study investigated the association between substantiated child maltreatment and multiple forms of intimate partner violence in young adults, using a linked dataset from a child protection agency.

The analyses point to four major findings. Firstly, child physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect are associated with experiencing later emotional intimate partner violence. Secondly, child sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect predict later risk for physical intimate partner violence. Thirdly, emotionally abused and neglected children have higher subsequent rates of combined intimate partner violence. Finally, emotional abuse predicts harassment. The findings may point to both specific and cumulative effects of child maltreatment on intimate partner violence victimization because multiple types of child maltreatment consistently predict intimate partner violence victimization. Moreover, the findings suggest the sustained effects of maltreatment on intimate partner violence in later life. These results confirm prior findings of the associations between child physical abuse (Widom et al. 2014), emotional abuse (Arata et al. 2007) and neglect (Widom et al. 2008), and later intimate partner violence experiences.

The current study has a number of strengths. Firstly, it uses a prospective large dataset of mother-child dyads from pregnancy to the age of 21 years old. This enabled us to control for potential confounders at individual, family and environment levels. Secondly, unlike most prior studies, our analyses only used linked child protection agency records of substantiated child maltreatment cases, providing an objective measurement of child maltreatment and reducing the chance of recall bias (McGee et al. 1995). The substantiated cases were then hierarchically grouped to represent each form of child maltreatment (Lau et al. 2005). Thirdly, we used a well validated tool to measure subsequent occurring intimate partner violence victimizations that may enhance the reliability and validity of our findings. Fourthly, we undertook simultaneous examinations of mutually non-exclusive and overlapping categories of child maltreatment against subscales of intimate partner violence victimizations. Finally and to our knowledge, this is the first study that addresses specific forms of substantiated child maltreatment and their effect on four different forms of intimate partner violence victimization experienced during early adulthood using a validated tool.

Despite the above strengths, the study has a number of limitations. Our reliance on substantiated measures of maltreatment may underestimate the actual levels of maltreatment (Gilbert et al. 2009) and involve biases inherent in official reporting and recording procedures (Widom et al. 2004). This may have led to unrecorded cases and an over representation of the severest forms of child maltreatment. On the other hand, there is evidence that later health outcomes are similar irrespective of whether cases are unsubstantiated self-reports or substantiated (Mills et al. 2016). Overlap across different forms of child maltreatment may also overlook the independent effects of each type of maltreatment. It is also acknowledged that there is significant overlap across both child maltreatment and intimate partner violence perpetration/victimization events that made it difficult to conduct more refined subgroup analyses. For instance, our analyses did not differentiate on whether intimate partner violence was male on female or vice versa. This may bias the findings as to the rates and patterns of being a victim and/or perpetrator of intimate partner violence and whether these may differ across gender. However, a focus on perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence may be misleading as it may occur from male on female (Fulu and Miedema 2015) or vice versa (Dobash and Dobash 2004). Moreover, it is likely that victims and perpetrators are in a relationship and intimate partner violence may be a characteristic of some intimate relationships (Anderson 2002), and the boundaries between being a perpetrator and victim are blurred with similar risk factors for both. Answering these questions in maltreated individuals requires further study. Finally, given the prospective recording of maltreatment throughout the childhood period and its overlap with subsequent early life adversities (Deborah 2013), the study could not determine the possible developmental pathways through which child maltreatment leads to intimate partner violence experiences.

There may be a number of explanations for these findings. For instance, the consistent and strong effect of child emotional abuse and neglect may be due to the deleterious effect these types of maltreatment have on emotional development (Arata et al. 2007) that, in turn, induce intimate partner violence (Meadow 1997). This may reflect the cumulative emotional impact of any form of maltreatment (Meadow 1997) increasing the risk of experiencing or committing intimate partner violence. The concern, however, is emotional abuse and neglect do not attract the same level of concern unless accompanied with other forms of child maltreatment (Meadow 1997). In contrast to previous findings (Daigneault et al. 2009), the association between sexual abuse and later emotional intimate partner violence victimization was not significant in our study. This is not to say the two are unrelated. Possible reasons for this non-significant finding include the underreporting of sexual abuse to child protection authorities (Widom et al., 2004) as a consequence of the secretive nature of sexual abuse as compared to other types of maltreatment (Polonko 2006). Victims’ feelings of guilt and shame to the known perpetrators who mostly are intimate family members may further hinder disclosure of sexual abuse cases to child protection authorities (Mills et al. 2016). Finally, children who are sexually abused tend to be abused in other ways as well.

Individual, family and environmental characteristics might have either a confounding or mediating effect or both in the associations between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimizations. Consistent with other studies (Daigneault et al. 2009), exposure to early childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence victimization are consistently skewed to socially disadvantaged young adults who were reared by mothers from more disadvantaged backgrounds. Social and/or psychological disorders and negative life events in the family (Linder and Collins 2005) predict both child maltreatment and intimate partner violence (Thornberry and Henry 2013). However, after adjusting for all selected confounders including residential problem area and aggressive behavior, child maltreatment remains strongly and independently associated with intimate partner violence victimization. Therefore, disadvantaged backgrounds, aggressive behavior during adolescence and currently living in a residential problem area do not explain the observed associations and do not seem to mediate the relationships between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization.

Moreover, although this study could not test for possible pathways that link childhood maltreatment to later intimate partner violence experiences, some emerging developmental-oriented studies have suggested a number of mechanisms that may lead to later intimate partner violence experiences for those maltreated as children (Cascardi 2016). Literature has suggested that exposure to severe child maltreatment such as poly-victimization may lead to later intimate partner violence experiences (Davis et al. 2015). This may be coupled with overlapping vulnerability (Zolotor et al. 2007) to poor social and mental health outcomes (Davis et al. 2015), and adolescent dating violence (Gómez 2010). For example, child maltreatment may be associated with poor mental health (Faulkner et al. 2014) and behavioral problems including distress (Cascardi 2016), distorted belief about violence and affiliation with deviant peers (Morris et al. 2015) all contributing to intimate partner violence experiences. This has been observed in child physical abuse survivors (Morris et al., 2015). Moreover, child maltreatment and physical and psychological intimate partner violence experiences have both been associated with some forms of disabilities including deafness and difficulty hearing (Williams and Porter 2014). This may be due to an inability to seek help (Powers et al. 2009) and a lack of access to preventative measures of violence including health education (Anderson and Pezzarossi 2011). This may further be explained from the perspective of “target vulnerability” (Finkelhor and Asdigian 1996), where escaping from the “harm” becomes less for those handicapped due to their underlying disabilities, which in turn may increase the propensity for later intimate partner violence experiences. Genetic factors (Fergusson et al. 2011) may also interact with child maltreatment and lead to later violence perpetration and/or victimization.

Collectively, the evidence suggests a detrimental effect of child maltreatment on multiple forms of later intimate partner violence. Appropriate interventions for child maltreatment may mutually mitigate later involvement in intimate partner violence in adulthood. In recognition of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends screening for prior exposure to maltreatment in individuals who have experienced intimate partner violence (Feder et al. 2013). There is also a need to understand more about the particular characteristics of those who have experienced child maltreatment but who did not engage in later intimate partner violence.

Conclusion

Childhood physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect are chronic adversities that appear to lead to physical intimate partner violence, emotional intimate partner violence, harassment and multiple forms of intimate partner violence victimization in adulthood. The ability to examine the associations between specific forms of child maltreatment and four different forms of intimate partner violence experiences, especially severe intimate violence, advances the current state of knowledge in this area. The associations between child maltreatment and subsequent intimate partner violence are consistent and strong but also complex and multiple. Further research may examine possible pathways that link exposure to childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence experiences, which could also address the peculiar characteristics of those who have experienced child maltreatment but who did not engage in later intimate partner violence.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile: department of psychiatry. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Bosinski, HAG: Geschlechtsidentitätsstörung/Geschlechtsdysphorie im Kindesalter.

Ackerman, B. P., Brown, E. D., D’Eramo, K. S., & Izard, C. E. (2002). Maternal relationship instability and the school behavior of children from disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 694. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.694.

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Taillieu, T., Cheung, K., & Sareen, J. (2014). Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(9), E324–E332. doi:10.1503/cmaj.131792.

Anderson, K. L. (2002). Perpetrator or victim? Relationships between intimate partner violence and well‐being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 851–863. doi:10.1111/j.17413737.2002.00851.

Anderson, M. L., & Pezzarossi, C. M. K. (2011). Is it abuse? Deaf female undergraduates’ labeling of partner violence. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, enr048. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enr048.

Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Brien, N. (2007). Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(4), 393–415. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.006.

Auslander, W., Sterzing, P., Threlfall, J., Gerke, D., & Edmond, T. (2016). Childhood abuse and aggression in adolescent girls involved in child welfare: the role of depression and posttraumatic stress. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1–10. doi:10.1007/s40653-016-0090-3.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory. http://www.esludwig.com/uploads/2/6/1/0/26105457/bandura_sociallearningtheory.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2016.

Banyard, V. L., Arnold, S., & Smith, J. (2000). Childhood sexual abuse and dating experiences of undergraduate women. Child Maltreatment, 5(1), 39–48. doi:10.1177/1077559500005001005.

Barrios, Y. V., Gelaye, B., Zhong, Q., Nicolaidis, C., Rondon, M. B., & Garcia, P.J., et al. (2015). Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLoS one, 10(1), e0116609. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116609.

Bordin, I. A., Rocha, M. M., Paula, C. S., Teixeira, M. C. T., Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., & Silvares, E. F. (2013). Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher’s Report Form (TRF): an overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29(1), 13–28. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2013000500004.

Campbell, R., Greeson, M. R., Bybee, D., & Raja, S. (2008). The co-occurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: a mediational model of posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 194. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.194.

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.e4.

Cascardi, M. (2016). From violence in the home to physical dating violence victimization: the mediating role of psychological distress in a prospective study of female adolescents. Journal of Youth And Adolescence, 45(4), 777–792. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0434-1.

Cicchetti, D., & Valentino, K. (2006). An ecological‐transactional perspective on child maltreatment: Failure of the average expectable environment and its influence on child development. Developmental Psychopathology, Second Edition, 129–201. doi:10.1002/9780470939406.ch4.

Coulton, C. J., Crampton, D. S., Irwin, M., Spilsbury, J. C., & Korbin, J. E. (2007). How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(11), 1117–1142. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.023.

Daigneault, I., Hébert, M., & McDuff, P. (2009). Men’s and women’s childhood sexual abuse and victimization in adult partner relationships: A study of risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(9), 638–647. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.003.

Davis, J. L., & Petretic-Jackson, P. A. (2000). The impact of child sexual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and synthesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 291–328. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00010-5.

Davis, K. C., Masters, N. T., Casey, E., Kajumulo, K. F., Norris, J., & George, W. H. (2015). How childhood maltreatment profiles of male victims predict adult perpetration and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260515613345.

Deborah, L. (2013). The community composite abuse scale: Reliability and validity of a measure of intimate partner violence in a community survey from the ALSWH. Journal of Women’s Health, Issues & Care. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000115.

Desai, S., Arias, I., Thompson, M. P., & Basile, K. C. (2002). Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence and victims, 17(6), 639–653. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725.

Dobash, R. P., & Dobash, R. E. (2004). Women’s violence to men in intimate relationships working on a puzzle. British Journal of Criminology, 44(3), 324–349. doi:10.1093/bjc/azh026.

Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S.R., Williamson, D. F., & Thompson, T.J., et al. (2004). The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 771–784. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008.

Eckenrode, J., Zielinski, D., Smith, E., Marcynyszyn, L. A., Henderson, Jr, C. R., & Kitzman, H., et al. (2001). Child maltreatment and the early onset of problem behaviors: can a program of nurse home visitation break the link? Development and Psychopathology, 13(04), 873–890.

Ehrensaft, M. K., Cohen, P., Brown, J., Smailes, E., Chen, H., & Johnson, J. G. (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 741. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.741.

El-Bassel, N., Gilbert, L., Wu, E., Go, H., & Hill, J. (2005). Relationship between drug abuse and intimate partner violence: a longitudinal study among women receiving methadone. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 465–470. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2003.023200.

Fang, X., & Corso, P. S. (2007). Child maltreatment, youth violence, and intimate partner violence: developmental relationships. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine, 33(4), 281–290. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.06.003.

Faulkner, B., Goldstein, A. L., & Wekerle, C. (2014). Pathways from childhood maltreatment to emerging adulthood investigating trauma-mediated substance use and dating violence outcomes among child protective services–involved youth. Child Maltreatment, 1077559514551944. doi:10.1177/1077559514551944.

Feder, G., Wathen, C. N., & MacMillan, H. L. (2013). An evidence-based response to intimate partner violence: WHO guidelines. JAMA, 310(5), 479–480. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.167453.

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., Horwood, L. J., Miller, A. L., & Kennedy, M. A. (2011). MAOA, abuse exposure and antisocial behavior: 30-year longitudinal study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(6), 457–463. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086991.

Finkelhor, D., & Asdigian, N. L. (1996). Risk factors for youth victimization: Beyond a lifestyles/routine activities theory approach. Violence and Victims, 11(1), 3–19.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(1), 7–26. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008.

Fry, D., McCoy, A., & Swales, D. (2012). The consequences of maltreatment on children’s lives: a systematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838012455873. doi:10.1177/1524838012455873.

Fulu, E., & Miedema, S. (2015). Violence Against Women: Globalizing the Integrated Ecological Model. Violence Against Women, 21(12), 1431–1455. doi:10.1177/1077801215596244.

Gewirtz, A. H., & Edleson, J. L. (2007). Young children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Towards a developmental risk and resilience framework for research and intervention. Journal of Family Violence, 22(3), 151–163. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9065-3.

Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373(9657), 68–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7.

González, R. A., Kallis, C., Ullrich, S., Barnicot, K., Keers, R., & Coid, J. W. (2016). Childhood maltreatment and violence: Mediation through psychiatric morbidity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 70–84. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.01.002.

Gómez, A. M. (2010). Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth & Society. doi:10.1177/004C4118X09358313.

Hegarty, K., Bush, R., & Sheehan, M. (2005). The composite abuse scale: further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence and Victims, 20(5), 529–547. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.2005.20.5.529.

Hegarty, K., & Valpied, J. (2013). Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) Manual. Melbourne: Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Mason, W. A., Kosterman, R., Lengua, L. J., Hawkins, J. D., & Abbott, R. D. (2004). Pathways from physical childhood abuse to partner violence in young adulthood. Violence and Victims, 19(2), 123–136. doi:10.1891/vivi.19.2.123.64099.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Moylan, C. A. (2008). Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. doi:10.1177/1524838008314797.

Herrera, V. M., & McCloskey, L. A. (2003). Sexual abuse, family violence, and female delinquency: Findings from a longitudinal study. Violence and victims, 18(3), 319–334. doi:10.1891/vivi.2003.18.3.319.

Hogan, J. W., Roy, J., & Korkontzelou, C. (2004). Handling drop‐out in longitudinal studies. Statistics in Medicine, 23(9), 1455–1497. doi:10.1002/sim.1728.

Holmes, M. R. (2013). Aggressive behavior of children exposed to intimate partner violence: An examination of maternal mental health, maternal warmth and child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(8), 520–530. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.12.006.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218.

Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(6), 706–716. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x.

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339 doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339.

Korbin, J. E., & Krugman, R. D. (2014). Handbook of Child Maltreatment. New York: Springer.

Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0.

Lang, A. J., Stein, M. B., Kennedy, C. M., & Foy, D. W. (2004). Adult psychopathology and intimate partner violence among survivors of childhood maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(10), 1102–1118. doi:10.1177/0886260504269090.

Lau, A. S., Leeb, R. T., English, D., Graham, J. C., Briggs, E. C., Brody, K. E., & Marshall, J. M. (2005). What’s in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 533–551. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.005.

Leeb, R. T. (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. Atlanta,GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Linder, J. R., & Collins, W. A. (2005). Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 252. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252.

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., Medina, A. M., & Oliver, P. H. (2003). The co-occurrence of husband-to-wife aggression, family-of-origin aggression, and child abuse potential in a community sample implications for parenting. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(4), 413–440. doi:10.1177/0886260502250835.

McGee, R. A., Wolfe, D. A., Yuen, S. A., Wilson, S. K., & Carnochan, J. (1995). The measurement of maltreatment: A comparison of approaches. Child Abuse and Neglect, 19, 233–249. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(94)00119-F.

Meadow, R. (1997). ABC of Child Abuse. 3rd Revised edn. London, United Kingdom: Bmj Publishing Group.

Messman-Moore, T. L., & Long, P. J. (2000). Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(5), 489–502. doi:10.1177/088626000015005003.

Messman-Moore, T. L., & Long, P. J. (2003). The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(4), 537–571. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9.

Metcalfe, C., Smith, G. D., Wadsworth, E., Sterne, J. A., Heslop, P., Macleod, J., & Smith, A. (2003). A contemporary validation of the Reeder Stress Inventory. British Journal of Health Psychology, 8(1), 83–94. doi:10.1348/135910703762879228.

Mian, M. (2004). World Report on Violence and Health: what it means for children and pediatricians. The Journal of Pediatrics, 145(1), 14–19.

Mills, R., Kisely, S., Alati, R., Strathearn, L., & Najman, J. (2016). Self-reported and agency-notified child sexual abuse in a population-based birth cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 74, 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.12.021.

Mills, R., Scott, J., Alati, R., O’Callaghan, M., Najman, J.M., & Strathearn, L. (2013). Child maltreatment and adolescent mental health problems in a large birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(5), 292–302. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.008.

Morris, A. M., Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2015). From family violence to dating violence: Testing a dual pathway model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(9), 1819–1835. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0328-7.

Najman, J. M., Aird, R., Bor, W., O’Callaghan, M., Williams, G. M., & Shuttlewood, G.J. (2004). The generational transmission of socioeconomic inequalities in child cognitive development and emotional health. Social Science & Medicine, 58(6), 1147–1158. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00286-7.

Najman, J. M., Alati, R., Bor, W., Clavarino, A., Mamun, A., & McGrath, J. J., et. al. (2015). Cohort profile update: The Mater-University of queensland study of pregnancy (MUSP). International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(1), 78–78f. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu234.

Noll, J. G., Horowitz, L. A., Bonanno, G. A., Trickett, P. K., & Putnam, F. W. (2003). Revictimization and self-harm in females who experienced childhood sexual abuse results from a prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(12), 1452–1471. doi:10.1177/0886260503258035.

Polonko, K. A. (2006). Exploring assumptions about child neglect in relation to the broader field of child maltreatment. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 260–284. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25790694.

Powers, L. E., Renker, P., Robinson-Whelen, S., Oschwald, M., Hughes, R., Swank, P., & Curry, M. A. (2009). Interpersonal Violence and Women With Disabilities Analysis of Safety Promoting Behaviors. Violence Against Women, 15(9), 1040–1069. doi:10.1177/1077801209340309.

Reeder, L., Schrama, P., & Dirken, J. (1973). Stress and cardiovascular health: an international cooperative study—I. Social Science & Medicine (1967), 7(8), 573–584.

Rumstein-McKean, O., & Hunsley, J. (2001). Interpersonal and family functioning of female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(3), 471–490. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00069-0.

Sabri, B., Hong, J. S., Campbell, J. C., & Cho, H. (2013). Understanding children and adolescents’ victimizations at multiple levels: An ecological review of the literature. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(3), 322–334. doi:10.1080/01488376.2013.769835.

Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision (SCRCSSP). (2000). Report on Government Services. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: AusInfo.

Stevens, T. N., Ruggiero, K. J., Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., & Saunders, B.E. (2005). Variables differentiating singly and multiply victimized youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents and implications for secondary prevention. Child Maltreatment, 10(3), 211–223. doi:10.1177/1077559505274675.

Stith, S.M., Smith, D. B., Penn, C. E., Ward, D. B., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(1), 65–98. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001.

Strathearn, L., Mamun, A. A., Najman, J. M., & O’Callaghan, M. J. (2009). Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics, 123(2), 483–493. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3546.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88.

Swartout, K. M., Cook, S. L., & White, J. W. (2012). Trajectories of intimate partner violence victimization. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(3), 272–277. doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11788.

Thornberry, T. P., & Henry, K. L. (2013). Intergenerational continuity in maltreatment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(4), 555–569. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9697-5.

Vega, E. M., & O’Leary, K. D. (2007). Test–retest reliability of the revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). Journal of Family Violence, 22(8), 703–708. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9118-7.

Wekerle, C., Wolfe, D. A., Hawkins, D., Pittman, A.-L., Glickman, A., & Lovald, B. E. (2001). Childhood maltreatment, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and adolescent dating violence: Considering the value of adolescent perceptions of abuse and a trauma mediational model. Development and Psychopathology, 13(04), 847–871.

White, H. R., & Widom, C. S. (2003). Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility and alcohol problems. Aggressive Behavior, 29(4), 332–345. doi:10.1002/ab.10074.

Whitfield, C. L., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166–185. doi:10.1177/0886260502238733.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S., & Dutton, M. A. (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(4), 650–663. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., & Dutton, M. A. (2008). Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8), 785–796. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006.

Widom, C. S., Raphael, K. G., & DuMont, K. A. (2004). The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004). Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 715–722. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009.

Widom, C. S., Schuck, A. M., & White, H. R. (2006). An examination of pathways from childhood victimization to violence: The role of early aggression and problematic alcohol use. Violence and Victims, 21(6), 675–690. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.039.

Williams, L. M., & Porter, J. L. (2014). The relationship between child maltreatment and partner violence victimization and perpetration among college students focus on auditory status and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260514552443. doi:10.1177/0886260514552443.

Wyatt, G. E., Axelrod, J., Chin, D., Carmona, J. V., & Loeb, T. B. (2000). Examining patterns of vulnerability to domestic violence among African American women. Violence Against Women, 6(5), 495–514. doi:10.1177/1077801200006005003.

Zolotor, A. J., Theodore, A. D., Coyne-Beasley, T., & Runyan, D. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Overlapping risk. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 7(4), 305 doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhm021.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our acknowledgments to the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy mother-child pairs, the research team, National Health and Medical Research Council and Australian Research Council for subsequent funding of the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy. We are also grateful to the International Postgraduate Scholarships of the Australian government and The University of Queensland for sponsoring the principal author of the study. AAA conceived of the study, designed analyses strategies, performed initial statistical analyses, interpreted data and drafted the manuscript; SK carried out final statistical analyses and provided comments to the manuscript; GW and AC provided comments to the manuscript; JMN has been a principal investigator of the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, provided comments and supervised the overall progress of the current manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council and Australian Research Council (NHMRC grant #1009460) and the principal investigator is in receipt of an International Postgraduate Research and The University of Queensland Centennial Scholarships. The funding sources had no roles in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

The Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy has been approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of the University of Queensland. Further ethical approval has also been obtained from the Human Ethics Review Committee of the University of Queensland to link substantiated child maltreatment data to the 21-year follow-up of the Mater Hospital-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study.

Appendix

Appendix

The 22 items taken from the Composite Abuse Scale and used in this study with respect to each form of intimate partner violence

Physical intimate partner violence victimization |

Slapped me |

Threatened to hit me or throw something at me |

Pushed, grabbed or shoved me |

Hit or tried to hit me with something |

Kicked me, bit me or hit with a fist |

Emotional intimate partner violence victimization |

Told me that I wasn’t good enough |

Tried to turn my family, friends and/or children against me |

Blamed me for causing his/her violent behavior |

Tried to keep me from seeing or talking to my family |

Became upset if dinner/housework wasn’t done when they thought it should be |

Tried to turn my family, friends and children against me |

Told me that I was stupid |

Told me that no one else would ever want me |

Told me that I was ugly |

Tried to keep me from seeing or talking to my family |

Tried to convince my family, friends and children that I was crazy |

Harassment |

Harassed me over the telephone |

Followed me |

Hung around outside my house |

Harassed me at work |

Severe Combined Abuse |

Used a knife or gun or other weapon |

Raped me |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abajobir, A.A., Kisely, S., Williams, G.M. et al. Substantiated Childhood Maltreatment and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization in Young Adulthood: A Birth Cohort Study. J Youth Adolescence 46, 165–179 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0558-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0558-3