Abstract

Geography remains a critical factor that shapes the development of aspirations, attainment, and choice in young people. We focus on the role of geography on university entry and aspirations due to the increasing requirement in society for a higher education qualification for access to prestigious positions in society. Using a large representative longitudinal database (N = 11,999; 50 % male; 27 % provincial or rural; 2 % Indigenous) of Australia youth we explore the association between distance to a university campus and the critical attainment outcomes of university entry and enrolment in an elite university as well as critical predictors of these outcomes in access to information resources (i.e., university outreach programs) and university aspirations. In doing so, we provide new insight into distance effects, and the extent that these are due to selection, cost, and community influence. Our findings suggest that distance is significantly associated with both university expectations and entrance, with an especially large impact upon young people from low socioeconomic backgrounds. However, we also find little evidence that distance is related to attending a university led information session. Our conclusion is that distance effects cannot be fully explained by selection in terms of academic achievement and socioeconomic status, and that anticipatory decisions and costs are the most likely drivers of the distance effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A critical developmental task of adolescence is to formulate and pursue post high-school educational and career plans (Dietrich et al. 2012; Parker et al. 2015; Fouad and Bynner 2008; Hall 2004; Savickas and Porfeli 2011). It has increasingly become the case that young people must formulate their plans in a context of qualification expansion that means they require a university level of education for access to many prestigious positions in society (Fouad and Bynner 2008). However, many young people who could attend university do not do so resulting in wastage of talent and lower status attainment (Dietrich et al. 2012; Côté 2006). Addressing this issue requires a multidisciplinary perspective that combines insights from developmental sciences with knowledge of the contextual influences that impact young peoples’ post high-school pathways.

From a developmental perspective, the issue of attainment begins with the formation of career self-concepts, investigation of the requirements to enact these self-concepts, and the marshaling of resources to meet associated goals (Savickas 2005). Development theory has long noted the need to take into account differences in situational affordances and resources available to young people from different sociocultural contexts (e.g., Bronfenbrenner and Evans 2000; Elder 1996; Magnusson and Cairns 1996; Sameroff 2010). For example, research has noted that both aspirations and access to information and availability of career models from which those aspirations develop differ by sociocultural context (Elder and Conger 2000; Schneider and Stevenson 1999). Likewise, noting that post high-school pathways are joint projects between young people and important others requires a consideration of (sub)cultural differences in the way education is perceived (James 2001; Young et al. 2001, 2008). Even when young people develop firm aspirations to attend university, those from particular contexts may face barriers to fulfilling these aspirations. In the current research, we explore the impact of geography, namely distance to higher education institutions, on access to university information during schooling, the development of aspirations to attend university, and attainment of these goals.

Distance to University

Access to higher education for children growing up in rural or remote communities is a critical issue of concern for those interested in the development educational inequality. Despite advances in technology, a recent report suggested educational outcomes among rural and remote youth had worsened in recent years, underlining this issue of inequity in life-chances (Bradley et al. 2008). In the current research, we develop the work of Denzler and Wolter (2011, p. 3), Turley (2009) and Crockett et al. (2000) to build a theoretical model of distance effects and test four central hypotheses. The selection hypothesis suggests that distance effects are not merely socioeconomic selection effects with distance representing a unique influence on the development of university aspirations and attainment (Elder and Conger 2000; Petrin et al. 2011). The anticipatory decision hypothesis suggests that the effects of distance are developmental and occur before issues related to costs become a barrier. The cost hypothesis suggests that distance may still influence entry to university, even after the formation of university aspirations. Finally, the context resources hypothesis suggests that part of the effect of distance may be due to different access to information resources on which young people build their post high-school aspirations. Figure 1 presents these hypotheses in the form of a graphical model. Thus the aim of this research is not merely to note the relationship between distance and educational attainment but to begin to evaluate the relative importance of various pathways or mechanisms by which distance may have their effect. In addition, we also consider whether these hypotheses apply not only to university entry, but also institutional choice.

Research dating back to the 1970s has considered the effect of distance from amenities and services on educational attainment (e.g., Tinto 1973). Utilizing a large longitudinal database and unique aspects of the Australian context, our research builds on this past research in several important ways. Research in this area has almost exclusively been conducted in the United Kingdom or United States (as such most of the cited research below is from these countries). Despite being a geographically large country, with a rather different higher education system, there is surprisingly little research on how distance affects university outcomes in Australia. Yet, given its low population density and clustering of universities within a few particular areas, Australia provides an ideal context in which the effect of distance on educational outcomes can be explored. In addition, the Australian system implicitly “controls” for several possible factors that may explain the role of distance present in previous research (conducted within the United States). For example, at the time of writing, university position assignment and fee structure were centrally regulated, consistent across universities and were largely covered by government low interest loans with conditional repayments determined by wage (Jerrim et al. 2015). As such direct costs associated with degrees likely play a smaller role in Australia, particularly when it comes to institution choice. This is clearly a rather different situation than the US.

Selection Hypothesis

While there is a long history of research on the effects of distance on university entry, there are concerns that this may actually represent “selection effects”. Put simply, there may be a tendency for low-income families to select themselves into areas with limited access to university campuses because, for example, housing may be more affordable. It is now well established that socioeconomic background is a key driving force in post-secondary outcomes. Boudon (1974) suggested that social class is the primary driver of educational inequality and effects educational and occupational outcomes via achievement differentials and systematic differences in rational choice behaviors and cultural influences (see below; Jackson et al. 2007; Parker et al. 2013). The Wisconsin model of status attainment likewise viewed educational attainment ultimately as a cause of innate ability and socioeconomic status, which has its effect on attainment via academic performance, influence of significant others, and individuals’ own aspirations (Sewell et al. 1970). More recently, comparative research from countries including Australia, the UK, and the US research has noted that social class is a strong and cross-culturally consistent predictor of university aspirations, entry, and enrolment into elite universities (Jerrim et al. 2015; Parker et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2015a, b). Indeed, the Bradley report (Bradley et al. 2008) notes that socioeconomic status remains the primary driver of educational inequality for young people. Thus it is important to ensure that the effect of distance contributes above and beyond socioeconomic status.

Importantly, rural poverty and its association with less ambitious educational aspirations and attainment is a very real concern in the developmental literature (Irvin et al. 2011). Thus, the association between distance and educational outcomes may actually be capturing socioeconomic factors, rather than the effects of place per se. This dilemma is present in research on rural poverty primarily aimed at identifying whether the effect of rural and remote living is purely or largely selection (see Weber et al. 2005). Despite raising a number of concerns, the review by Weber et al. does nevertheless suggest that, controlling for a range of individual characteristics, place of residence exerts a unique effect on critical outcomes.

Cost

Outside of research that questions whether place effects exist at all is research that considers place effects to be largely or solely related to costs. Such a view is quite strong in the economic analyses, where distance to a university campus is often used as an instrumental variable to explore the effect of higher education qualifications on labor market outcomes (Denzler and Wolter 2011). From this perspective, young people from all regions equally desire to attend university (i.e., have similar aspirations), but differ in the costs associated with university entry. Leaving aside the cost of a university degree, which, as we noted above, is less of a concern in Australia than it is in either the UK or the US (Jerrim et al. 2015), the issue of relocation and/or commuting expenses becomes paramount. Put simply, university may be a more appealing option for young people living close to a campus, as they will not have to move out of the family home.

Importantly, “costs” may not merely be financial, but also logistical and emotional (Turley 2009). The emotional and logistical costs for rural youth in particular may be exacerbated by more interdependent relationship structures in the family home where parents are more reliant on their children (Crockett et al. 2000; Elder and Conger 2000). Likewise, young people’s strong connection to their community may also create a migration constraint that impacts university entry when relocation is a requirement (Byun et al. 2012; Elder et al. 1996). Indeed, children from rural backgrounds often develop much stronger connections to the community (Elder and Conger 2000). In contrast to stereotype, some research suggests that connection to community may be strongest among those who are most likely to qualify for university entry (Petrin et al. 2011).

The degree to which the effect of costs reflects financial costs or social and emotional costs may be identified by exploring the degree to which the effect of distance on university entry varies as a function of socioeconomic status. Several authors have suggested that the effect of distance is particularly pronounced for low socioeconomic groups (e.g., Elder et al. 1996; Gibbons and Vignoles 2009; James 2001). Thus, the degree to which distance is primarily an issue for poorer children would lend support to primary costs being financial and logistic rather than emotional. Importantly, there is growing recognition that costs alone are insufficient to explain the effect of distance. Crockett et al. (2000) note that rural youth generally have lower educational and occupational aspirations than their urban peers suggesting factors present earlier in adolescents’ educational careers.

Anticipatory Decision Hypothesis

Turley (2009) and Denzler and Wolter (2011) highlight the need to not only consider costs at or near the point of transition to university, but also the way in which young people’s aspirations develop. Indeed, educational aspirations typically develop well before the end of high school (Gambetta 1987; Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb 2010). Jackson et al. (2007) referred to such an effect as “anticipatory decisions”, whereby young people make their post-school choices early in their educational careers, and subsequently act upon them. Put simply, many young people make decisions to not attend university well before costs as a barrier to entry become apparent. Importantly Gambetta (1987) suggested that such decisions vary by geography (e.g., North vs. South Italy). Indeed, it is now well established that adolescents in rural areas develop less ambitious educational and career aspirations than their urban peers (Crockett et al. 2000).

The potential impact of anticipatory decisions suggests the important role that career development theories may play in predicting university entry (see Dietrich et al. 2012 for a review). Savickas (2005); see also Gati and Asher 2001) suggests that a critical developmental task of adolescence is to develop a career self-concept by in-breadth exploration of available options and in-depth exploration of the requirements of the preferred options (e.g., is university required to enact a given career self-concept). Vondracek and Porfeli (2008) note that students pursue these career related behaviors within a given developmental context, while Young and colleagues (Young et al. 2001, 2008) noted the role that social capital plays where a young person’s career and educational development can be conceptualized as a joint project between the adolescent and those around them.

These career development issues can vary as a function of geography. Rural and remote economies are far less diverse than urban economies (where the vast bulk of university campuses are located) and thus there are fewer exemplar occupations modeled to young people (Crockett et al. 2000; Elder and Conger 2000; Elder et al. 1996). Leveraging of Bronfenbrenner and Morris’ (1998) concept of social capital as “engines of development”, Elder and Conger (2000) note that strong family and community relationships, many of which center around work, create influential models from which occupational plans and aspirations develop. Further, the models that are available and ones that are less likely to require a university level of education. In addition, family models are also likely to have a direct impact on aspirations. Consistent with Young and colleagues, research has found that parents, peers, and important others play an important shaping role in the development of aspirations and post-school plans in rural youth (Byun et al. 2012; Chenoweth and Galliher 2004). Likewise, Elder and Conger (2000) note the stronger social capital in combination with a distinct set of values in rural communities as a strong influence on post high-school pathways. James (2001, p. 470) similarly notes that much of the negative effect of geography on university aspirations “reflect, in the main part differences in family and community attitudes to the relevance of education”.

Importantly, the degree to which the distance effect is conveyed via university aspirations rather than cost has profound practical implications. Specifically, it would mean that interventions need to happen earlier rather than latter and that a focus should be on influencing young people career development processes rather than offering scholarships and bursaries.

Community Resources

Having a campus close by may provide young people with additional resources that encourage a university-going predisposition (Griffith and Rothstein 2009). Turley (2009) suggests universities typically have a number of outreach programs that may facilitate a preference for university entry in young people and their peers within the surrounding area. Such programs provide information on how to access university and experience of what going to university may be like. Similarly, such programs may promote university preferences among a young person’s peers, thereby also encouraging their own university entry. It is thus possible that adolescents in rural and remote regions may have lower educational expectations because they do not have access to the same outreach programs (Mangan et al. 2010). There remains limited empirical evidence, however, as to whether young people who live further away from a university campus actually do receive less university outreach programs. Such a hypothesis needs testing in modern contexts where the advent of the Internet allows universities greater access to remote communities.

Elite University Entry

Up to now, we have focused our attention on university entry. Increasingly, however, the issue of institutional choice is a critical factor in explaining long-term status attainment (Jerrim et al. 2015; Bowen et al. 2009). Graduates from such universities earn more (Black and Smith 2006; Hoekstra 2009; Long 2007), with a “quality” signal to employers that have implications for long term status attainment (Rivera 2011). A critical concern then is the degree to which the theoretical model outlined in Fig. 1 holds not just for entry into university globally, but for those who enroll in an elite university (the gray box in Fig. 1). Here we turn our focus to institution choice and thus our focus moves from distance to any university to distance to an elite university.

A notable conclusion from the work of Gibbons and Vignoles (2009) in the UK is that distance may also have a critical role in whether young people enroll in elite universities. Indeed, their findings suggest that distance is the single most important factor in institutional choice. Mangan et al. (2010) likewise suggest that there exists a “postcode lottery” in the same country (the UK) when it comes to accessing elite universities. In the United States, Bowen et al. (2009) note similar concerns, with those from rural and remote areas being less likely to attend elite universities and more likely to attend community colleges. Much of this effect, in the US, is likely explained by geography, with almost half of all elite universities located in the north east of the country (Griffith and Rothstein 2009). In Australia the idea that geography may have an influence on access to elite universities is particularly concerning, given that all Group of Eight (Go8) institutions are in major cities, and all but two are in the southeast (see Fig. 2).

Plot of participant locations, in gray, and campus locations, in black circles for elite universities and black diamonds for other universities. Large circles or diamonds represent large campuses offering over 100 accredited courses. Smaller circles or diamonds represent smaller campuses. Note that we focus here only on the Australian mainland

Current Research

In the current research we identify and test a series of hypotheses about the mechanisms by which distance may affect university entry and subsequently enrolment in an elite university. We specify four broad hypotheses.

Selection Hypothesis

We predict that distance has an effect on university outcomes, over and above prominent covariates and in particular socioeconomic status. Support for this hypothesis would lend credence to a “true” distance effect. In other words, there is an effect of distance per se, and that an association with university outcomes is not simply being observed due to social selection.

Anticipatory Decision Hypothesis

We hypothesize that distance has an effect on university expectations at age 15 and that these expectations will be a strong predictor of university entry. Support for this hypothesis would suggest that the effect of distance is not merely due to costs.

Cost Hypothesis

We hypothesize that distance has an effect on university entry controlling for educational expectations. Support for this hypothesis would indicate that the effect of distance is unlikely to only reflect anticipatory decisions of young people. Rather it will provide indicative evidence of an important role of costs, highlighting the potential value of scholarship or bursary packages. Further, if distance has differential effects for advantaged and disadvantaged youth, costs relating to relocation and living expenses are likely to be a major contributing factor (Gibbons and Vignoles 2009; Griffith and Rothstein 2009). Given unique issues of the Australian context, we also consider the interaction between distance and Indigenous status (Parker et al. 2013).

University Outreach Influence Hypothesis

Consistent with Turley (2009), we hypothesize that distance is associated with poorer access to university-led outreach programs.

Elite University Enrolment

Increasingly, there is interest not only in the role that distance plays in predicting university entry but also in institutional choice. Much of this research has focused on enrolment in elite universities. We hypothesize that distance from an elite university campus will predict this enrolment and we consider whether hypotheses one through four operate similarly when elite university enrolment is the focus of research.

Methodology

Participants

Two cohorts of the LSAY database were used: LSAY2003 and LSAY2006. Using two cohorts provided greater coverage of the population centers on the Australia mainland (N = 11,999). These cohorts represent longitudinal extensions of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA2003 and PISA2006), a representative sample of 15 years old. Population weighted distance quantiles can be found in Table 1 and basic descriptive statistics in Table 2. Both cohorts used a two-stage sampling procedure, with the primary sampling unit being schools selected proportional to size, and then a random sample of students from that school. As with any large-scale longitudinal survey, particularly those covering major developmental transitions, attrition was present. Weights are provided that aim to account for the multi-stage sample design and attrition (Marks and Long 2000). A map of participant coverage and the locations of all university campuses based in Australia is presented in Fig. 1.

For university expectations and university entry we used the full sample. When we considered elite university enrolment however, we restricted our sample only to those who entered university so as to focus on institution choice (see Table 2 for sample size). This is consistent with similar research including research focused on attainment as a sequence of transitions (Lucas 2001) and research focused on performance versus choice influences on educational attainment (see Jerrim et al. 2015; Jackson et al. 2007 for examples).

Measures

University Expectations, Entry, and Information Sessions

Three variables were derived relating to expectations of a university education, university entry, and entry into an elite higher education institution. Children were asked at age 15 what level of education they expected to achieve. We coded those selecting bachelor’s degree or equivalent, or postgraduate study, as expecting a university level of education. Individuals were considered to have entered university if at any time during the waves covering ages 17–19 they indicated they had entered, were currently studying, had stopped studying, or had completed a university degree. Elite university entry was defined as attending a member of the Group of Eight (Go8; see Jerrim et al. 2015 for further details). The Go8 is a self-selected alliance of research-intensive universities that represent the oldest, most prestigious, and internationally recognized universities in Australia. Indeed, in the most recent Times World University Ranking, the Go8 were the highest ranked universities in the Oceania region. They are also the only Australian universities in the top 200 universities worldwide (https://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2014-15/world-ranking/region/oceania). Again, data concerning entry into a Go8 university was taken from the waves covering ages 17–19.

Finally, we considered the influence of university outreach programs via a single item from the second wave (age 16) of the LSAY2006Footnote 1 cohort. Here participants were asked whether they had “attended an information session at a university or by someone from a university?” In total, 47 % of participants had attended such a session by age 16.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status was measured using the PISA index of economic, social, and cultural capital (ESCS) (OECD 2004; see http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=5401). This index is taken from a principal component of parental employment, education, job prestige, and household possessions (see Geske and Grinfelds 2012). The index has an international mean of zero and standard deviation of one. In Table 2 we report this index in the original scale, but re-standardized it within our models so that the mean in Australia is zero and standard deviation one.

Distance Measures

Distance measures were based on a three-stage procedure. First, the Australian Government registry of educational providers (http://cricos.education.gov.au/) was accessed to get the physical street address of all university campuses in Australia. We then removed any campus that was a preparation college for international students or offered less than 10 government registered courses on site (i.e., campuses that were both very small and highly specialized). As a result we developed a database of 176 campuses, covering the 39 universities, on mainland Australia. The Google Maps API was then used to get the latitude and longitude of the street addresses of each. Due to privacy restrictions, the LSAY database provides postcodes of residence rather than physical street address. We used the population-weighted centroids of postcodes as a proxy for residential location of each participant in the absence of any finer-grained data. The use of population-weighted centroids adjusts the longitude and latitude coordinates for the distribution of the population within each postcode. The coordinates of where participants lived and the university campuses were then used to calculate road network-based travel distances within a Geographic Information System. This network-based approach is more likely to represent the actual distance that a participant would be required to factor into their decision-making process, rather than a simpler Euclidean-based distance metric that would not take into account major variations in topography within Australia (likely resulting in an under-estimate). Distances for each participant were calculated for their nearest university campus and the number of university campuses in proximity for predicting expectations of a university level of education and university entry. For predicting enrolment in an elite university we calculated distance to the nearest elite university campus and number of elite university campuses in proximity. All GIS-calculations were produced using ArcGIS v.10.

Proximity was defined based on the average commute distance of Australians [over 60 % of Australians have a commute distance of 20 km or less; Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2014 Catalog no. 4102]. Research has tended to use distance to the nearest campus to define distance effects. Turley (2009), however, notes that there may be qualitative advantages in terms of increased options and resources for those that have more than one university campus in proximity. For this reason we also focus on number of universities in proximity, rather than the more typical distance to nearest university campus. Results based on these distance measures are presented in supplementary material. As noted below results are generally similar regardless of the distance measure used.

Covariates

Several covariates were included in the analysis including state of residence, gender, Indigenous status, birth cohort, and science, reading, and mathematics standardized achievement scores from the PISA database (see OECD 2004 for details). The ABS index of educational and occupational level (IEO) of the participants post-code was also included

(http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100072011).

Analysis

All models were analyzed using logistic regression. The basic model (M1) was constructed as follows:

where \( U_{i} \) is individual i’s probability of a “success” on a given educational outcome (i.e., expect to attend university, attended university, attended an elite university). \( {\mathbf{X}}_{{\mathbf{i}}} \) is a vector of demographic covariates such as gender, distance is a distance measure (proximity in the main article and log distance in supplementary material), and ses is an estimate of the influence of children’s socioeconomic status. A second set of models (M2) were similar but included the interaction between distance and ses, and between distance and Indigenous status. Full results can be found at the paper website: http://blindedforreview.com/distancePaper/.

Sensitivity Analysis

There are certain limitations with the data available. First, the method used to generate the ESCS index (our primary measure of socio-economic status) changed slightly between 2003 and 2006. However, these minor adjustments appear to have had relatively limited impact upon the final scale (Geske and Grinfelds 2012). Nevertheless, to check the robustness of our results, all models have been re-estimated using an alternative measure of ses (the international socio-economic index of occupational status—see Ganzeboom et al. 1992). In all cases, results are similar regardless of which measure is used (see paper website).

The second limitation was a change in postcode collection between the 2003 and 2006 cycles of the LSAY. In LSAY2003 age 15 postcodes represented the neighborhood in which the participant lived. In the matching wave in LSAY2006 postcodes represented the neighborhood in which children went to school. Later waves reverted back to listing the postcode of the neighborhood in which participants lived. To ensure this made little difference to the results we ran sensitivity analysis using home postcodes for the LSAY2003 and LSAY2006 from wave 2 (age 16). This made almost no difference to the results, which is unsurprising as participants typically lived in the same or neighboring postcode to which they went to school. All sensitivity analysis can be found on the paper website.

Missing Data and Survey Design

The LSAY population and attrition weights were applied throughout our analysis to ensure estimates were representative of the Australian population in the context of participant attrition (47 % attrition was noted from wave 1 (age 15) to wave 5 (age 19) of the study).

In addition to attrition a small amount of missing data at the individual item level was apparent (see Table 2). To account for this we ran multiple imputations using a bootstrapped expectation maximization approach (Honaker et al. 2011). Given the small amount of missing data five imputations was considered sufficient. In addition, five plausible values were generated for each pupil, estimating their true proficiency in each subject. These scores were scaled by the survey organizers (across all OECD countries) to have a mean of 500 points and standard deviation of 100. Given that the estimation of a participant’s true score is uncertain, the survey providers provide five plausible values drawn from the participant’s posterior ability distribution. One set of plausible values was assigned to each of the multiple imputations and likewise integrated using the survey package in R. This provided a means of incorporating uncertainty in estimation that results from the use of multiple imputed datasets and the use of multiple plausible values for achievement. The data also had a nested structure with individuals nested within schools. Balanced Repeated Replication (BRR) weights, provided by the survey organizers, were used to account for the two-stage survey design.

Results

As noted above, we focus here on the effect of number of university campuses (for university aspirations and university entry), and the number of elite university campuses (for elite university enrolment), in proximity as predictors of higher education outcomes. Results based on the distance in kilometers tend to provide consistent results (see supplementary material—Paper Website: https://pdparker.github.io/distancePaper/). We first consider the main effects of distance, conditional upon all covariates, on (a) expectations of a university education, (b) university entry and (c) entry into an elite university.

Models are presented in the following order: (a) the influence of having at least one campus or elite campus in proximity, (b) the influence of each additional campus in proximity, and (c) adding an additional term for the number of campuses squared [under the assumption that there is likely a saturation point (turning point of quadratic effect) beyond which any additional university is of little consequence]. The average saturation point was estimated using the equation:

where x is the number of campuses at which any additional campus provides no added benefit (i.e., the saturation point). \( \beta_{1} \) is the log-odds effect of an additional campus and \( \beta_{2} \) is the log-odds effect of an additional campus squared.

Models in which the response variable is university entry or entry into an elite university also control for university expectations at age 15. Finally it is important to note that models in which the response variable is entry into an elite university are conducted only on the subsample of those who entered any university. This is because it is only for this group that institution choice is relevant. In addition, we focus on distance as measured in relation to the number of elite university campuses in proximity. Results relating to number of any university campus in proximity were much smaller and occasionally not statistically significant (see Paper Website: https://pdparker.github.io/distancePaper/ for results).

University Aspirations

Table 3 presents the findings in log-odds of distance measures predicting expectations of a university education. Supporting the anticipatory decision hypothesis, results suggested that the probability (evaluated at mean or mode of all covariates) of expecting a university level of education for young people with at least one campus in proximity was 0.63. This compared to a probability of 0.51 for those individuals without a campus in proximity. A difference of this magnitude (12 % points) is large, and statistically significant at conventional thresholds. Our analysis also suggested that the relationship between the number of universities in proximity and the chances of expecting to enter university were non-linear. In particular, the quadratic term was sizeable and statistically significant, suggesting that beyond 24 campuses in proximity there was no additional benefit of an additional campus in proximity (estimated turning point for the quadratic effect).

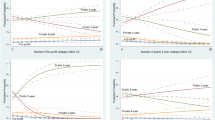

In addition, Table 3 shows that there was a significant interaction between socioeconomic status and distance. Here we use one standard deviation above (hereafter richer) and one standard deviation below (hereafter poorer) the Australian mean of the ESCS index as reference points.Footnote 2 The probability of expecting a university level of education, when at least one university campus was in proximity, was 0.62 for poorer children. This compared to a probability of 0.48 when there was no university campus nearby—a difference of 14 % points. In contrast, the advantage of having a university campus close by for children from affluent backgrounds is significantly smaller. Specifically, they have a 68-percent chance of entering university if at least one campus is close by and 63-percent if not (a difference of just 5 % points). Interestingly, the saturation point was also reached much quicker for the richer kids (20 campuses) than for the poorer kids (26 campuses). The implication of these results are demonstrated in Fig. 3, highlighting the particular benefit of living near to a university for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. No interaction was found for Indigenous status by distance.

University Entry

We next considered the effect of distance on university entry, controlling for university aspirations and socioeconomic status. Supporting the selection hypothesis living within commuting distance of at least one campus significantly improved the chance of attendance. Specifically, young people with no university campus nearby had only a 42-percent chance of entering university, compared to 50-percent for those with at least one institution within 20 km proximity. There was again also evidence of a non-linear relationship. This suggested that as each additional campus within proximity led to a lower marginal increase in the chances of entering university until a saturation point was reached at 29 campuses (the turning point of the quadratic effect). However, some caution is needed when interpreting this non-linearity, as it is being driven by the upper tail of the distribution (i.e., by individuals with an unusually large number of campuses nearby—see Fig. 4).

It is important to recall that along with the large number of demographic and academic covariates included in these models, expectations of a university level of education at age 15 has also been controlled. The effect on aspirations was indeed extremely strong. However, supporting the cost hypothesis, distance still exerted a unique, independent effect on university entry.

Again we explored the interaction effect of socioeconomic status and distance. This interaction was not significant when considering if at least one university campus was in proximity. There was a significant interaction when considering, how many universities were in proximity but this effect disappeared when the significant quadratic effect of number of campuses in proximity was entered (Table 4).

University Information Session Attendance

We next considered whether distance was associated with whether an individual attended an information session to test the university outreach hypothesis. As we note in the method section this was only explored with one of the LSAY cohorts given that this was the only cohort to ask this specific question. As can be seen from Table 5, controlling for covariates there was no association between distance and attendance at a university information session. The results indicate that attendance was largely predicted by state of residence, gender (favoring females), and socioeconomic status. Overall, we therefore find little evidence that distance matters per se for attending a university information session.

Institution Choice

Up to this point, our models have considered the full sample and considered distance to any university campus to construct proximity measures. We now turn our attention to the issue of institution choice and in particular enrolment in one of Australia’s elite universities. Consistent with Lucas (2001) we consider this only for individuals who have entered university and we construct proximity measures in relation to distance to elite university campuses (however, see supplementary material—Paper Website: https://pdparker.github.io/distancePaper/ for results based on distance to any university campus).

Results in Table 6 show, having at least one elite university campus in proximity led to a significant advantage in gaining entry into such an institution. In particular, young people with at least one Go8 campus nearby had a 34-percent chance of attending an elite university, compared to just a 21-percent for those who did not. There was again some evidence of a non-linear relationship between number of campuses nearby and chances of entering a high status university, though this was again being driven by a small number of individuals with a large number of campuses within close proximity (see Fig. 5). Indeed, the turning point was at 10 campuses, which is the maximum number that was possible for a participant to have in proximity. No significant interaction effects were observed for the interaction between distance and socioeconomic status or distance and Indigenous status.

Consistent with the selection hypothesis and the cost hypothesis distance had a clear significant effect on elite university enrolment controlling for socioeconomic status and university aspirations. However, university aspirations were not significant predictors of institution choice. This suggested anticipatory decisions, at least in relation to university aspirations, had little role in institution choice.

Discussion

Geography is a critical factor that shapes the development of aspirations, attainment, and choice in young people (Elder and Conger 2000). Geography not only shapes resources and affordances that impact young people’s attempts to implement their post high-school plans but also can influence the development of aspirations. Indeed, research has highlighted how occupational and higher educational models and resources as well as social capital and attachment to community differ by geography (Crockett et al. 2000). A university level of education is increasingly important for access to prestigious positions in society (Côté 2006). Despite its importance, there remains ongoing inequality in access to higher education for those living outside of major urban centers (Bradley et al. 2008). Thus, it is of critical importance to identify the presence and impact of the various mechanism by which geography shapes higher education aspirations and attainment. We considered the effect that distance had on expectations of a university level of education (age 15), attendance at a university outreach information session (age 16), university entry (between ages 16 and 19), and enrolment into an elite institution (between ages 17 and 19). The consistent result was that distance did indeed have an effect on all outcomes of interest, with the exception of attendance at a university information session. The current research aimed not only to indicate whether distance was related to university outcomes, but also to tease apart the relative contribution of various mechanisms that have been suggested elsewhere in the literature by way of the four central hypotheses outlined in Fig. 1. We discuss the implications of our results for each of these hypotheses in turn.

Selection Hypothesis

The effects of distance were statistically significant, even after conditioning on a range of covariates. The most important of these were individual-level socioeconomic status and postcode average educational and occupational levels. This suggested that the significant influence of distance was more than merely due to poorer families being disproportionately located at greater distances from a university campus. Put simply, distance appears to represent an additional disadvantage for young people in relation to the development of university aspirations, attainment of those aspirations, and entry to an elite university. In addition, the results of distance were significant over and above standardized tests of math, reading, and science ability. There is an emerging literature that suggests that children in geographically disadvantaged locations are less likely to have highly qualified teachers and are often less well resourced (Kannapel and DeYoung 1999; see also Byun et al. 2012), which may account for their lower levels of academic achievement (Pegg and Panizzon 2007). Yet, the results here suggest that the influence of distance could not be accounted for by differences in academic ability or socioeconomic status alone.

Distance was also a significant predictor of educational aspirations controlling for both family socioeconomic status and postcode average educational and occupational status. This is consistent with finding from the US (see Byun et al. 2012 for a review). Importantly, this directs attention toward how various social and community processes lead to different developmental influences in different geographic areas (Byun et al. 2012).

Anticipatory Decision Hypothesis

Large effects were found for the effect of distance on expectations of a university level of education at age 15. The effects were considerable, with the presence of at least one campus in proximity being associated with over a 10-percent point increase in the likelihood of expecting a university level of education. Such a finding suggests that the effect of distance is related to more than just cost related factors, which suggest strong developmental effects. Importantly, consistent with the Wisconsin model of status attainment (Sewell et al. 1970), these aspirations went on to be strong predictors of actual university entry. Taken together, these findings suggest that at least part of the effect of distance on higher education educational outcomes occurs at least as early as age 15 and, based on research on the formation of aspirations Gambetta (1987) and Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb (2010), may occur even sooner than that.

Such a finding is important as it suggests that programs designed to increase attendance of regionally disadvantaged youth cannot merely focus on scholarships, stipends, or bursaries. Instead, intervention needs to occur much earlier in adolescents’ educational careers. To effectively do so, however, further research is needed to identify the particular developmental mechanisms that are at play. For example, Crockett et al. (2000) (see also Elder and Conger 2000; Elder et al. 1996) suggested that rural and remote communities are less economically diverse and generally consist of jobs that do not require a university degree thus providing students with fewer options to consider when developing a career self-concept or set of goals (see Dietrich et al. 2012 for a review). This would suggest the need to provide youth with greater access to career models and information.

Interestingly, socioeconomic status moderated the effect of distance on expectations of a university level of education. Again, given the current data, it is unclear what set of competing mechanisms may explain this. It may be that richer adolescents have access to more diverse occupational models that can supplement a lack of such model in regional areas (Elder et al. 1996). Alternatively, consistent with the findings of Gambetta (1987) and Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb (2010), it is also likely be true that children from more affluent and highly educated families inherit a university going habitus at a very early age regardless of location.

It is important to note that anticipatory decisions, as we operationalized them, cannot explain the effect of distance on enrolment in elite universities given that aspirations had a non-significant effect on elite university enrolment. This may mean that the decision to go to university is strongly impacted by developmental mechanisms but that institution choice is largely related to costs. However, developmental effects may be masked by our narrow operationalization of anticipatory decisions. Factors related more specifically to institution choice like parents’ alma mater may have indicated bigger effects for anticipatory decisions for elite university enrolment (Jerrim et al. 2015). Such results are consistent with findings that young people tend to have a preference for attending universities that are near them (Gibbons and Vignoles 2009). Similar conclusions have been found in the US, where most elite university campuses are located in the north east of the country (Griffith and Rothstein 2009). Our findings from Australia also highlight such concerns. Like the US, Australian elite universities are also not randomly distributed, with all but two universities located in major cities in the southeast. As we note above, research tends to suggest that young people who attend an elite university accrue a number of potential advantages (Black and Smith 2006; Hoekstra 2009; Long 2007; Rivera 2011). Thus, our findings are likely to be of particular concern to those living in smaller cities, rural and remote regions, and those located outside of the east-coast of Australia.

Cost Hypothesis

It is also important to note that even for university entry, anticipatory decisions could not explain the whole effect of distance. Our results suggest a more complicated picture. It was true that distance was significantly and strongly related to expectations of a university level of education, and that these expectations were very strong predictors of actual university entry. However, even after controlling for these expectations, we found significant effects of distance upon both university entry and institutional choice controlling for aspirations. As such, the influence of distance is unlikely to be due to anticipatory decisions alone. This suggests consideration of costs, whether they be economic, logistic, social, or emotional, is likely to be important (Turley 2009).

The finding of significant distance effects controlling for aspirations directs attention toward issues of cost, and suggests scholarship programs and stipends remain viable interventions (Gibbons and Vignoles 2009; Griffith and Rothstein 2009). However, it should be noted that there was relatively little evidence that these distance effects differed by socioeconomic or Indigenous status. As such, it could be that young people, regardless of their social origin, find the prospect of moving from the family home to attend university a central barrier to entry (Denzler and Wolter 2011). In other words, it may be logistic, social and emotional costs, rather than economic, that drives the cost proportion of the distance effect in Australia. Such costs may be higher in rural and remote settings due to stronger social capital and community attachment (Crockett et al. 2000; Elder and Conger 2000). This suggests that interventions may need to focus on providing resources that mean young people do not have to sacrifice their connection to their community in order to attend university (see Petrin et al. 2011 for example interventions).

University Outreach Influence Hypothesis

Turley (2009) suggests that proximity to university may influence attendance via outreach programs. In the current research, we found no evidence that distance uniquely impacted the likelihood of a young person attending a university outreach session. Rather, state of residence, gender, and socioeconomic status were significant predictors. The strong effects of state of residence may indicate differences in state board of education policies relating to the timing of when university outreach programs occur. In particular, we had data on attendance on university programs when most participants were in year 11 but not from when participants were in their final year of schooling (year 12). The other major predictors were being female and having higher socioeconomic status. It remains a question for future research to determine whether the effects of gender and socioeconomic status reflect inequalities in access to such programs or individual level choices. However, these results do suggest that university outreach programs may not be the leading mechanism explaining why there is an association between distance and expectations of entering higher education (in Australia at least).

Strengths and Limitations

Unlike many studies in this area, we have used longitudinal data, and thus temporal precedence was established for outcomes like university entry. Bias attributable to reverse causation is an important limitation of a field of enquiry replete with studies of cross-sectional data and, as such, our ability to align exposure prior to outcomes constitutes an important methodological advance.

While temporal alignment is an important pre-requisite for the identification of causal effects, our research is still based upon an assumption of key characteristics of individuals being observable (Morgan and Winship 2014). Omitted variables bias is a common limitation of observational studies in this field and some potential candidates include data on choice behaviors and barriers associated with university entry. In particular, variables related to access to information and the social capital needed to interpret that information would be of interest (Bowen et al. 2009). Likewise, information on parents alma mater, presence of strong and weak ties that can help reduce the logistic, emotional, and social costs of relocation for university on the one hand, and measures of relative risk aversion, differences in expectations of success or future orientations on the other (Breen and Goldthorpe 1997) are all important variables that could contribute to research in this area.

To take the quality of evidence yet further ahead, a quasi-experimental study would be interesting but not necessarily a panacea. For instance, a “natural experiment” may consist of assessing how university related outcomes change amongst young people in a region before and after the introduction of a new university campus in the local area that previously did not have one. Or, as was the case with the “Moving To Opportunity” (MTO) program in the US, a design may involving random assignment of household relocation vouchers so that families can move nearer to university campuses (Sampson 2008). However, most university expansion in Australia (and probably in many other countries too) relates to the opening of new campuses in areas where other universities are already located, perhaps to take advantage of existing local infrastructure. Even were a rare case to become available for research purposes, however, the development of university campuses is not random and therefore the opportunity to mimic a cluster randomized controlled trial would appear to be limited. Likewise, it is unlikely that an MTO-type program will be repeated due to financial, ethical and methodological implications, not least to do with the degree of freedom participants may be afforded to choose where there live and how long they choose or feel able to remain in the new neighborhood (Ludwig et al. 2008). As such, the results of carefully controlled observational studies of longitudinal data like the one that we have presented in this article are likely to remain the backbone for informed public policy debate on this important societal issue.

A related issue is the potential for some variables to be misclassified. In the case of our study, the LSAY databases only provide postcode locations and, for ethical reasons, not street addresses of participants. Although population-weighted centroids eliminate some of the bias that would have been incurred were geometric centroids of postcodes used as surrogates for home address, there inevitably remains some degree of variation in the accuracy of the distance estimates that could not be avoided and should be considered as the best ethically available proxy.

Conclusion

Our study provides novel findings from a country where long distances to resources and institutions are widely conceptualized as disadvantageous, but hitherto scant research has been conducted from the point of view of educational aspirations and attainment. Previous research has considered aspirations, university entry, or institution choice but rarely all three in a single context. Furthermore, most evidence in this area is from cross-sectional samples. As such, it has been hard to distinguish between, and evaluate, the various mechanisms involved and the degree to which developmental mechanisms versus barriers to entry are at play. We have enriched an evidence base that is predominantly focused upon studies set within the US and UK contexts. Moreover, our study enhances the credibility of the evidence available for decision makers through the analysis of a large source of longitudinal data. Results suggest that distance exerts a unique influence on aspirations and attainment over-and-above socioeconomic status and academic ability. Our results suggest that the effect of distance includes developmental influences, which may include the relationship between distance and the availability of a diverse set of career models (Elder et al. 1996). Controlling for aspirations, distance continues to exert a unique effect. This suggests ongoing influences of costs many of which may be emotional and social due to young people from rural communities’ strong connection to community (Crockett et al. 2000; Elder and Conger 2000; Petrin et al. 2011). Furthermore, on the available evidence, cost appears to explain most of the influence of distance on university choice.

Notes

The LSAY2003 had a similar question but that conflated university and technical/vocational colleges.

For all marginal effects covariates were set to the mean for all continuous variables, and mode for all nominal variables.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2014). Australian social trends. Catlog no. 4102.

Black, D., & Smith, J. (2006). Estimating the return to college quality with multiple proxies for quality. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 701–728.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in western society. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bowen, W., Chingos, M., & McPherson, M. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and society, 9, 275–305.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development, 9, 115–125.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In P. W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 993–1028). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Byun, S., Meece, J. L., Irvin, M. J., & Hutchins, B. C. (2012). The role of social capital in educational aspirations of rural youth. Rural Sociology, 77, 355–379. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00086.x.

Chenoweth, E., & Galliher, R. V. (2004). Factors influencing college aspirations of rural West Virginia high school students. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 19, 1–14.

Côté, J. E. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 85–116). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Crockett, L. J., Shanahan, M. J., & Jackson-Newsom, J. (2000). Rural youth: Ecological and life course perspectives. Adolescent Diversity in Ethnic, Economic, and Cultural Contexts, 10, 43–74.

Denzler, S. & Wolter, S. (2011), Too far to go? Does distance determine study choices?, IZA Discussion Papers 5712.

Dietrich, J., Parker, P. D., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2012). Phase-adequate engagement at the post-school transition. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1575–1593.

Elder, G. H. (1996). Human lives in changing societies: Life course and developmental insights. In R. B. Cairns, G. H. Elder, & E. J. Costello (Eds.), Developmental science (pp. 31–62). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Elder, G. H., & Conger, R. D. (2000). Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Elder, G. H., King, V., & Conger, R. D. (1996). Attachment to place and migration prospects: A developmental perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 397–425.

Fouad, N. A., & Bynner, J. (2008). Work transitions. American Psychologist, 63, 241–251. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.4.241.

Gambetta, D. (1987). Were they pushed or did they jump?: Individual decision mechanisms in education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B.

Gati, I., & Asher, I. (2001). Prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice: From decision theory to career counseling practice. Career Development Quarterly, 50, 140–157.

Geske, A., & Grinfelds, A. (2012). Family background and effects on learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 1267–1270). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6.

Gibbons, S., & Vignoles, A. (2009). Access, choice and participation in higher education (January). Retrieved from http://cee.lse.ac.uk/pubs/default.asp

Griffith, A. L., & Rothstein, D. S. (2009). Can’t get there from here: The decision to apply to a selective college. Economics of Education Review, 28, 620–628. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.01.004.

Grodsky, E., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2010). Those who choose and those who don’t: Social background and college orientation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627, 14–35.

Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., Morin, A. J. S., & Yeung, A. S. (2015a). Expectancy-value in mathematics, gender and socioeconomic background as predictors of achievement and aspirations: A multi-cohort study. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 161–168.

Guo, J., Parker, P. D., Marsh, H. W., & Morin, A. J. S. (2015b). Achievement, motivation, and educational choices: A longitudinal study of expectancy and value using a multiplicative perspective. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1163–1176.

Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 65, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006.

Hoekstra, M. (2009). The effect of attending the flagship state university on earnings: A discontinuity-based approach. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 717–724.

Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–47. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v45/i07/

Irvin, M. J., Meece, J. L., Byun, S. Y., Farmer, T. W., & Hutchins, B. C. (2011). Relationship of school context to rural youth’s educational achievement and aspirations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1225–1242. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9628-8.

Jackson, M., Erikson, R., Goldthorpe, J. H., & Yaish, M. (2007). Primary and secondary effects in class differentials in educational attainment the transition to A-level courses in England and Wales. Acta Sociologica, 50, 211–229.

James, R. (2001). Participation disadvantage in Australian higher education: An analysis of some effects of geographical location and socioeconomic status. Higher Education, 42, 455–472. doi:10.1023/a:1012264010667.

Jerrim, J., Chmielewski, A. K., & Parker, P. D. (2015). Socioeconomic inequality in access to high-status colleges: A cross-country comparison. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 42, 20–32. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027656241500044X.

Kannapel, P. J., & DeYoung, A. J. (1999). The rural school problem in 1999: A review and critique of the literature. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 15, 67–79.

Long, M. (2007). College quality and early adult outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 27, 588–602.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects 1. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 1642–1690.

Ludwig, J., Liebman, J. B., Kling, J. R., et al. (2008). What can we learn about neighborhood effects from the moving to opportunity experiment? American Journal of Sociology, 114, 144–188.

Magnusson, D., & Cairns, R. B. (1996). Developmental science: Toward a unified framework. In R. B. Cairns, G. H. Elder, & E. J. Costello (Eds.), Developmental science (pp. 7–30). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mangan, J., Hughes, A., Davies, P., & Slack, K. (2010). Fair access, achievement and geography: explaining the association between social class and students’ choice of university. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 335–350. doi:10.1080/03075070903131610.

Marks, G., & Long, M. (2000). Weighting the 1995 year 9 cohort sample for differential response rates and sample attrition: Technical paper No. 15. LSAY Technical Reports. Melbourne. Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=lsay_technical

Morgan, S. L., & Winship, C. (2014). Counterfactuals and causal inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2004). PISA 2003 technical report. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Parker, P. D., Bodkin-Andrew, G., Marsh, H. W., Jerrim, J., & Schoon, I. (2013). Will closing the achievement gap solve the problem? An analysis of primary and secondary effects for Indigenous university entry. Journal of Sociology. doi:10.1177/1440783313498946.

Parker, P. D., Schoon, I., Tsai, Y., Nagy, G., Trautwein, U., & Eccles, J. (2012). Achievement, agency, gender, and socioeconomic background as predictors of postschool choices: A multi-context study. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1629–1642.

Parker, P. D., Thoemmes, F., Duinveld, J., & Salmela-aro, K. (2015). I wish I had (not) taken a gap-year? The psychological and attainment outcomes of different post-school pathways. Developmental Psychology, 51, 323–333.

Pegg, J., & Panizzon, D. (2007). Schooling in rural and regional areas: Inequities in student achievement for literacy. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30, 177–190.

Petrin, R. A., Farmer, T. W., Meece, J. L., & Byun, S. Y. (2011). Interpersonal competence configurations, attachment to community, and residential aspirations of rural adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1091–1105.

Rivera, L. (2011). Ivies, extracurriculars, and exclusion: Elite employers’ use of educational credentials. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29, 71–90.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81, 6–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x.

Sampson, R. (2008). Moving to inequality: Neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 189–231.

Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In R. W. Lent & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2011). Revision of the career maturity inventory: The adaptability form. Journal of Career Assessment, 19, 355–374. doi:10.1177/1069072711409342.

Schneider, B. L., & Stevenson, D. (1999). The ambitious generation: America’s teenagers, motivated but directionless. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Ohlendorf, G. W. (1970). The educational and early occupational status attainment process: Replication and revision. American Sociological Review, 35, 1014–1027. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2093379?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Tinto, V. (1973). College proximity and rates of college attendance. American Educational Research Journal, 10, 277–293. doi:10.3102/00028312010004277.

Turley, R. N. L. (2009). College proximity: Mapping access to opportunity. Sociology of Education, 82, 126–146. doi:10.1177/003804070908200202.

Vondracek, F. W., & Porfeli, E. J. (2008). Social contexts for career guidance throughout the world: Developmental-contextual perspectives on career cross the lifespan. In J. A. Athanasou & R. van Esbroeck (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 209–225). New York: Springer.

Weber, B., Jensen, L., Miller, K., Mosley, J., & Fisher, M. (2005). A critical review of rural poverty literature: Is there truly a rural effect? International Regional Science Review, 28, 381–414. doi:10.1177/0160017605278996.

Young, R. A., Marshall, S. K., Domene, J. F., Graham, M., Logan, C., Zaidman-Zait, A., et al. (2008). Transition to adulthood as a parent–youth project: Governance transfer, career promotion, and relational processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 297–307. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.297.

Young, R. A., Valach, L., Ball, J., Paseluikho, M. A., Wong, Y. S., DeVries, R. J., et al. (2001). Career development in adolescence as a family project. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 190–202. doi:10.1037//0022-0167.48.2.190.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by the Australian Research Council (DE140100080), the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Jacobs Foundation.

Author’s Contribution

PP conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; JJ participated in the design and interpretation of the data and helped draft the manuscript; JA participated in the design and helped draft the manuscript; TAB constructed the distance measures, contributed to the design and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Paper Website: https://pdparker.github.io/distancePaper/.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parker, P.D., Jerrim, J., Anders, J. et al. Does Living Closer to a University Increase Educational Attainment? A Longitudinal Study of Aspirations, University Entry, and Elite University Enrolment of Australian Youth. J Youth Adolescence 45, 1156–1175 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0386-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0386-x