Abstract

Spiritual self-care is defined as a set of patient-centered or family-centered spiritual activities aimed at promoting health and well-being. In chronic diseases such as cancer, the responsibility for care typically falls on the patient or their family, necessitating an accurate assessment of the patient’s self-care practices to achieve this goal. The objective of this study was to translate, culturally adapt, and examine the psychometrics of the Persian version of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS) in cancer patients. This scale is designed to be administered directly to patients to assess their spiritual self-care practices. This cross-sectional study was conducted at the oncology ward in Afzalipoor Hospital, Javad Al-Aemeh Clinic, and Physicians Clinics affiliated with Kerman University of Medical Sciences in Kerman, southeast Iran. The study included qualitative and quantitative assessments of face validity, content validity, item analysis, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (construct validity), and reliability. Data collection took place between March 20, 2023, and December 30, 2023. The scale’s content validity index was calculated to be 0.948, with mostly minor revision comments for most items. The item-content validity indices ranged from 0.7 to 1. Exploratory factor analysis revealed a five-factor solution with 23 items, explaining 61.251% of the total variance. The identified factors were labeled as ‘personal and interpersonal spiritual practices,’ ‘shaping and strengthening relationship practices,’ ‘religious practices,’ ‘physical spiritual practices,’ and ‘reshaping relationship practices.’ Most of the confirmatory factor analysis indices were satisfactory (χ2/df = 1.665, CFI = 0.934, IFI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.058). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale was 0.89, while it ranged from 0.596 to 0.882 for the subscales. The Persian version of SSCPS with 23 items demonstrates reliability and effectiveness in assessing the spiritual practice performance of Iranian cancer patients. Compared to the original version, the Persian adaptation of SSCPS is concise, making it a suitable instrument for future research and practice on spiritual self-care among Iranian cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In chronic diseases, patients and their families primarily administer self-care. Understanding their self-care needs requires a comprehensive perspective from the patient and/or family (Valizadeh et al., 2020). Recognizing the efficacy of spirituality in self-care assists in managing and adapting to new conditions (Salimi et al., 2017). Spirituality profoundly impacts human health and contributes to its enhancement (Haidar et al., 2023). White defines spirituality as an individual's mental beliefs, encompassing reflections on relationships, affirmation of a higher power, and recognition of one’s place in the world, leading to engagement in spiritual activities (White, 2016). Spiritual practices positively influence health and quality of life (Asadi et al., 2019; White, 2016). Spiritual self-care involves patient- or family-centered activities aimed at promoting health and well-being, including listening to music, meditation, participating in religious ceremonies, reading religious texts, walking, and enjoying nature (Hekmati Pour et al., 2020).

In palliative care, spiritual self-care complements conventional approaches, addressing physical, mental, and emotional dimensions (Gijsberts et al., 2019; Salimi et al., 2017). The interconnection between mind, spirit, and body, alongside upbringing, beliefs, and life experiences, forms the foundation of spiritual self-care (Ramazani & Bakhtiari, 2019). It aids in finding meaning in life, connecting with a higher power, adapting to stress, and personal growth (Hojjati et al., 2015). Spiritual care fosters positive emotions and optimal nervous system functioning, aiding recovery in illness and enhancing well-being (Rahnama et al., 2021).

Self-care practices in patients with cancer improve quality of life, symptom management, and life satisfaction (Goudarzian et al., 2019). Cancer triggers fear, anxiety, disruptions in quality of life, and emotional disturbances affecting patients and families (Taets & Fernandes, 2020). Globally, cancer poses a significant health challenge, with Iran experiencing an increasing burden of the disease (Farahani et al., 2018). Iran ranks cancer as the third leading cause of death, with an estimated annual incidence of 98–110 cases per 100,000 people (Danaei et al., 2019).

Due to spirituality's significance in chronic illness, there is a need for a comprehensive tool to evaluate spiritual self-care efficacy. Existing assessment tools often blend religious and spiritual beliefs with practices and may not isolate spiritual self-care evaluation from beliefs. Some instruments primarily focus on religious aspects, limiting their applicability (White & Schim, 2013). Additionally, several tools have predominantly focused on the religious facets of spirituality. For instance, the spiritual well-being scale (SWBS), a widely used tool for assessing spirituality, predominantly reflects the metaphysical and religious dimensions of this construct. Furthermore, a key limitation of other instruments in this domain, such as the spirituality scale (SS) and the spiritual experience index (SEI), is their exclusive emphasis on religious beliefs and experiences (Delaney, 2005; Kass et al., 1991).

Recognizing the distinction between beliefs and practices, White and colleagues developed the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS) to measure specific spiritual practices independently from beliefs (White & Schim, 2013). The SSCPS assesses participants' performance across four domains: personal self-care, spiritual practices, physical spiritual practices, and interpersonal spiritual practices. Given the importance of spirituality in cancer care and the availability of a reliable tool, this study aims to investigate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of SSCPS (P-SSCPS) among cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study employed a cross-sectional design with two phases, encompassing translation and cultural adaptation, as well as the evaluation of the validity and reliability of the P-SSCPS. The research was carried out at the oncology ward in Afzalipoor Hospital, Javad Al-Aemeh Clinic, and Physicians Clinics affiliated with Kerman University of Medical Sciences in Kerman, a city situated in southeast Iran.

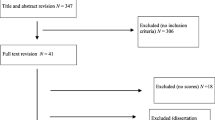

Participants, Sampling, and Sample Size

The study targeted all cancer patients receiving care at medical facilities associated with Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Inclusion criteria included individuals who were at least 18 years old, demonstrated a clear understanding of the questionnaire, had a confirmed cancer diagnosis, and did not exhibit physical and/or mental illnesses or active suicidal thoughts. Exclusion criteria involved incomplete responses to more than 10% of the questions on each tool. The sampling strategy encompassed cancer patients across various disease stages. If a patient was deemed unfit to complete the tool independently, they were either asked to do so at a more suitable time or assisted through an interview with the researcher. Convenience sampling was utilized for the construct and convergent validity phases, while a combination of convenience and purposive sampling methods was employed for other phases. The sample sizes for each section were as follows: (1) qualitative and quantitative face validity: 10 and 20 samples of cancer patients, respectively; (2) qualitative and quantitative content validity: 10 samples of experts for each; (3) pilot study (to assess internal consistency before conducting exploratory factor analysis): 50 cancer patient samples; (4) exploratory factor analysis (EFA): 320 samples; (5) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA): 200 samples. The sampling period spanned from March 20, 2023, to December 30, 2023.

Measurements

Demographic Characteristics Form

This form comprises fields for collecting information on age, sex, marital status, occupation, income, educational level, and clinical features such as cancer type, disease duration, diagnosis duration, illness severity, treatment type, past medical conditions, and hospitalization history.

The Spiritual Self-Care Practice Scale (SSCPS)

Developed by Mary L. White in 2013, this scale aims to explore the role of spiritual self-care as a mediator between quality of life and depression. The SSCPS consists of 35 items that evaluate participants' engagement in spiritual self-care across four domains: personal care methods, spiritual practices, physical spiritual practices, and interpersonal spiritual practices. Respondents are required to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher total scores indicating a greater level of spiritual self-care. White’s study reported that the scale demonstrated appropriate content and structural validity, with a reliability estimate of Cronbach's alpha coefficient at 0.92, signifying good internal consistency (White & Schim, 2013).

Procedure, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

Translation and Cultural Adaptation of SSCPS

Initially, two proficient Farsi-language translators, one with expertise in psychological concepts, independently translated the original SSCPS into two Persian versions. Subsequently, a third Farsi-language translator synthesized the initial two Persian translations to create a more coherent Persian version. To ensure semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence with the original scale—a critical criterion for cross-cultural adaptation—two skilled English-language translators conducted the back-translation of the Persian version into English. Throughout this process, the research team collaborated closely with the translators and obtained explicit permission from Dr. Mary L. White to review and finalize the Persian version, making necessary adjustments to ensure precise alignment with the intended meaning of the original scale. Additionally, we followed the scale translation and validation procedure outlined by Koenig and Al Zaben for religious and spiritual measures (Koenig & Al Zaben, 2021).

Face Validity

The face validity of the scale was evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative face validity assessment involved conducting face-to-face interviews with ten participants to assess the difficulty, relativity, and ambiguity of the preliminary Persian version of the SSCPS. For quantitative face validity assessment, the Item Impact Method was employed to determine the importance of each item and subsequently reduce items deemed less significant. This method involved calculating the product of the proportion of participants who rated an item as important on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 for not at all important to 5 for completely important) and the mean score representing the item's importance. The Item Impact Score was computed using the formula:

Frequency (%) represents the percentage of participants who rated the item with a score of 4 or 5. Items with an impact score of ≥ 1.5 were deemed appropriate for further analysis. Following this, the scale was assessed by a minimum of 20 participants to evaluate fluency, simplicity, and comprehensibility, ensuring the tool’s efficacy for a diverse range of users (Heravi-Karimooi et al., 2010; Tinsley & Brown, 2000).

Content Validity

The scale's content validity was assessed through a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. Experts, including nursing faculty members, psychologists, and methodologists, played a vital role in evaluating the qualitative content validity of the scale. Their expertise guided the assessment process, offering valuable feedback on various aspects such as content coverage, grammar adherence, use of appropriate language, and item placement. Quantitatively, the content validity index (CVI) was employed. Experts rated each item on a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = requires major revision, 3 = relevant but needs minor revision, 4 = completely relevant). The item-content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated by determining the proportion of experts who rated an item as 3 or 4. An I-CVI value of 0.8 indicated agreement. The scale-content validity index (S-CVI) was computed as the mean score of I-CVI for all items. An S-CVI of 0.9 or higher indicated satisfactory content validity. This dual qualitative and quantitative approach ensured a thorough evaluation of content validity (Heravi-Karimooi et al., 2010).

Item Analysis

The scale items underwent analysis and refinement to create the final test version using correlation coefficients and Cronbach's α coefficient. Pearson's correlation coefficient was utilized to examine the relationship between each item and the total score of the scale. Items with correlation coefficients ≥ 0.2 with the total score were retained. Cronbach's α coefficient was employed to evaluate the internal reliability of the scale. If removing an item from the total scale results in an increase in Cronbach's α coefficient, it suggests that the item may impact the scale's internal reliability and should be removed from the scale.

Construct Validity

The scale’s structural validity was evaluated through both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. In the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), principal component analysis (PCA), principal axis factoring (PAF), and maximum likelihood (ML) methods were employed, along with varimax and promax rotation techniques. Criteria for determining the number of factors included eigenvalues greater than 1, scree plots, and item loadings of 0.4 or higher. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted to assess the derived structure using indices such as χ2/df, GFI, CFI, IFI, and RMSEA. Acceptable fit criteria consisted of χ2/df less than 3.0 and RMSEA less than 0.08, with GFI, CFI, and IFI values considered acceptable if they were greater than or equal to 0.9. These analyses ensured a comprehensive evaluation of the scale's structural validity (Harrington, 2009).

Reliability

The reliability of the scale was assessed twice. Initially, internal consistency was examined using a sample of 50 individuals from the target population. Subsequently, after factor analysis, the obtained coefficients were interpreted, with values exceeding 0.7 deemed indicative of acceptable reliability (Chehrei et al., 2016).

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS 18.0 and AMOS package. Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations were utilized for continuous variables following a normal distribution, while frequencies and percentages were used for dichotomous variables. Face and content validities were assessed based on expert ratings of the items. Item analysis involved correlation coefficients and Cronbach’s α coefficient to screen items for inclusion in the final test version. Construct validity was evaluated through exploratory factor analysis for item screening and confirmatory factor analysis to validate the factorial structure of the scale. The reliability of the scale was determined using Cronbach's α coefficient.

Ethical Considerations

The project obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Furthermore, permission was sought from Professor Mary L. White for the translation of SSCPS into Persian. Subsequent to ethical approval, participants were presented with a consent form. The researcher elucidated the research objectives, guaranteed confidentiality, reassured participants that their involvement would not impact their treatment process, and then distributed tools to patients. The consent form outlined the study’s purpose, objectives, data confidentiality, participant anonymity, and the option to withdraw at any point. Participants formally signed informed consent forms.

Results

Face and Content Validity

Initially, face validity testing was conducted with ten cancer patients, revealing that only items 8, 10, 15, 16, 18, 26, 28, 32, and 35 had an item impact score of < 1.5. Although these items were considered for removal during this preliminary phase, they were ultimately retained in the scale. Subsequently, content validity was assessed with a panel of experts consisting of ten faculty members: two with a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, five with a Ph.D. in nursing and experience in spiritual care, one social medicine specialist and methodologist, and two psychiatrists. The scale-content validity index (S-CVI) was calculated to be 0.948, with mostly minor revision comments provided for most items. The item-content validity index (I-CVI) ranged from 0.7 to 1 (refer to Table 1).

Item Analysis

In a pilot study for item analysis, the scale was administered to 50 cancer patients. The item-total correlations were found to be greater than 0.2 for all items except for items 12, 16, and 35 (as indicated in Table 1). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale was determined to be 0.892, with values of 0.792, 0.743, 0.767, and 0.691 for personal spiritual practices, spiritual practices, physical spiritual practices, and interpersonal spiritual practices, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficient did not significantly change after deleting each item (refer to Table 1).

Construct Validity

Structural validity was evaluated in a sample of 550 participants, with a mean age of 34.37 ± 10.80 years. The majority of participants were female, married, employed, and had academic education (refer to Table 2).

In our sample, there were no missing data, and the mean scores of the items ranged between 1.82 and 4.35, as detailed in Table 3. To evaluate the factorial structure of the scale, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was initially conducted to determine if the sample size was suitable for factor analysis. The test yielded statistical significance (χ2 = 6127.345, df = 595, P < 0.001), indicating that the data exhibited spherical distribution. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy produced a coefficient of 0.865, indicating the factorability of the correlation matrix of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS). Principal component analysis (PCA), parallel analysis factor (PAF), and maximum likelihood (ML) with varimax and promax rotation methods were utilized, with the results from PCA with varimax rotation being ultimately presented. A five-factor solution with an eigenvalue > 1 was derived (refer to Table 3). This five-factor solution accounted for 61.251% of the total variance, leading to the exclusion of 12 items at this stage. Scree plots supported a five-factor solution as appropriate. Based on item categorization within each factor, we designated the first factor as ‘Personal and Interpersonal Spiritual Practices,’ the second factor as ‘Shaping and Strengthening Relationship Practices,’ the third factor as ‘Religious Practices,’ the fourth factor as ‘Physical Spiritual Practices,’ and the fifth factor as ‘Reshaping Relationship Practices.’

Following the identification of a five-factor structure through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the factor structure derived from EFA. A first-order CFA model was utilized, and all factor loadings were found to be statistically significant. Although the goodness of fit index (GFI) slightly fell below the criterion (GFI = 0.867), other fit indices demonstrated satisfactory results (χ2/df = 1.665, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.934, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.935, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.058 [95% confidence interval 0.047–0.068]). Consequently, we were able to confirm the factor structure identified through EFA using the CFA model.

Reliability

The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale was 0.89, with individual coefficients of 0.882 for ‘Personal and Interpersonal Spiritual Practices,’ 0.596 for ‘Shaping and Strengthening Relationship Practices,’ 0.802 for ‘Religious Practices,’ 0.763 for ‘Physical Spiritual Practices,’ and 0.788 for ‘Reshaping Relationship Practices’ (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we meticulously conducted translation and cultural adaptation following a double translation strategy and expert opinions to develop the Persian version of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS). The findings indicate that the Persian SSCPS exhibits strong reliability and validity, rendering it suitable for assessing the spiritual self-care practices of Iranian cancer patients.

The qualitative assessment of face validity confirmed the fluency, simplicity, and comprehensibility of the Persian SSCPS, leading us to retain all items despite some having item impact scores below 1.5. Moreover, the item-content validity index (I-CVI) for the Persian SSCPS ranged from 0.70 to 1.00, with a scale-content validity index (S-CVI) of 0.948, surpassing or closely aligning with standard reference values for content validity (Rodrigues et al., 2021). This indicates that the items in the Persian SSCPS effectively capture the intended domain for Iranian cancer patients. Furthermore, while most items exhibited significant correlations with the overall scale, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.2, removing individual items did not notably alter the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale. Consequently, no items were eliminated based on item-total scale correlation results. Collectively, these outcomes support the inclusion of all items in factor analysis and underscore the robustness of the Persian SSCPS for evaluating spiritual self-care practices among Iranian cancer patients.

In the present study, all items from the original scale were retained, prompting the utilization of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to elucidate the factor structure of the Persian version of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS). Prior research suggests that EFA is appropriate when the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value exceeds 0.60 and Bartlett's sphericity test yields statistical significance (DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021; Johnson & Christensen, 2019). In our study, the KMO value was 0.865, and the Bartlett’s sphericity test was statistically significant, justifying the conduct of factor analysis on the dataset. To determine the number of factors in EFA, eigenvalues equal to or greater than 1 are typically considered. Additionally, a minimum factor loading above 0.30 is recommended for item placement within factors (Hu et al., 2019). In our analysis, EFA identified five factors with factor loadings for all items exceeding 0.30 and a minimum loading of 0.42, leading to no item deletions at this stage. These five factors collectively explained 61.251% of the total variance, surpassing the variance explained by the original scale (47%), indicating a robust factor structure for the Persian SSCPS. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to assess the construct validity of the five-factor structure. The results demonstrated that the model fit met statistical significance criteria with χ2/df < 3, comparative fit index (CFI) and incremental fit index (IFI) values exceeding 0.9, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08 (Gefen et al., 2000). These findings underscored sufficient structural validity for the Persian version of SSCPS.

Internal reliability of a scale is considered quite reliable if the Cronbach’s α coefficient falls between 0.60 and 0.80 and highly reliable if it ranges from 0.80 to 1.00 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; Rattray & Jones, 2007). The Persian version of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS) exhibited a Cronbach’s α coefficient exceeding 0.80 for the overall scale, consistent with the original scale (0.91), indicating good reliability of the translated and culturally adapted version (Waltz et al., 2010). While factor 2 had a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.596, the other three factors achieved coefficients above 0.75. These findings suggest that the Persian SSCPS is relatively stable, with most indicators meeting satisfactory or acceptable levels, rendering it a reliable and valid instrument for assessing spiritual self-care practices among Iranian cancer patients.

Limitations

However, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, although the sample size met the criteria for conducting factor analyses, all participants were recruited through convenience sampling, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to all Iranian cancer patients. Therefore, future research should involve multi-center studies with larger and more diverse samples to further assess the applicability of the Persian SSCPS. Secondly, as the scale was self-administered, response bias may have influenced results. Despite acceptable fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), future studies should explore discriminative and convergent validity between information structures to enhance understanding of scale performance. Lastly, while internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient in this study, other reliability measures such as criterion reliability and test–retest reliability were not assessed. Thus, future research should include these metrics to comprehensively evaluate the reliability of the Persian SSCPS.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed a Persian version of the spiritual self-care practice scale (SSCPS) with a five-factor structure tailored for Iranian cancer patients, demonstrating acceptable construct validity and internal reliability. In conclusion, the Persian SSCPS emerges as a reliable and effective tool for assessing spiritual self-care practices among Iranian individuals battling cancer. Notably, the Persian version of SSCPS is concise, comprising 23 items, allowing for quick completion of the scale and rendering it a convenient instrument for future research and clinical applications focused on spiritual self-care practices in Iranian cancer patients.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Asadi, P., Ahmadi, S., Abdi, A., Shareef, O. H., Mohamadyari, T., & Miri, J. (2019). Relationship between self-care behaviors and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Heliyon, 5(9), e02493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02493

Chehrei, A., Haghdoost, A., Fereshtehnejad, S., & Bayat, A. (2016). Statistical methods in medical science researches using SPSS software. Elm Arya Publications.

Danaei, M., Haghdoost, A., & Momeni, M. (2019). An epidemiological review of common cancers in Iran: A review article. Iranian Journal of Blood and Cancer, 11(3), 77–84. https://ijbc.ir/browse.php?a_id=865&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Delaney, C. (2005). The spirituality scale: Development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010105276180

DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications.

Farahani, A. S., Rassouli, M., Mojen, L. K., Ansari, M., Ebadinejad, Z., Tabatabaee, A., Azin, P., Pakseresht, M., & Nazari, O. (2018). The feasibility of home palliative care for cancer patients: The perspective of Iranian nurses. International Journal of Cancer Management. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijcm.80114

Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

Gijsberts, M.-J.H., Liefbroer, A. I., Otten, R., & Olsman, E. (2019). Spiritual care in palliative care: A systematic review of the recent European literature. Medical Sciences, 7(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7020025

Goudarzian, A. H., Boyle, C., Beik, S., Jafari, A., Bagheri Nesami, M., Taebi, M., & Zamani, F. (2019). Self-care in Iranian cancer patients: The role of religious coping. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(1), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0647-6

Haidar, A., Nwosisi, E., & Burnett-Zeigler, I. (2023). The role of religion and spirituality in adapting mindfulness-based interventions for Black American communities: A scoping review. Mindfulness, 14(8), 1852–1867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02194-5

Harrington, D. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195339888.001.0001

Hekmati Pour, N., Mahmoodi-Shan, G. R., Ebadi, A., & Behnampour, N. (2020). Spiritual self-care in adolescents: A qualitative study. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 34(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2019-0248

Heravi-Karimooi, M., Anoosheh, M., Foroughan, M., Sheykhi, M. T., & Hajizadeh, E. (2010). Designing and determining psychometric properties of the domestic elder abuse questionnaire. Iranian Journal of Ageing, 5(1), 1–15. in Persian.

Hojjati, H., Pour, N. H., Khandousti, S., Mirzaali, J., Akhondzadeh, G., Kolangi, F., & Nia, N. M. (2015). An investigation into the dimensions of prayer in cancer patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 3(1), 65–72. in Persian.

Hu, Y., Tiew, L. H., & Li, F. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the spiritual care-giving scale (C-SCGS) in nursing practice. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0662-7

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2019). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Sage Publications.

Kass, J. D., Friedman, R., Leserman, J., Zuttermeister, P. C., & Benson, H. (1991). Health outcomes and a new index of spiritual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/1387214

Koenig, H. G., & Al Zaben, F. (2021). Psychometric validation and translation of religious and spiritual measures. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3467–3483.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated.

Rahnama, M., Rahdar, M., Taheri, B., Saberi, N., & Afshari, M. (2021). The effect of group spiritual care on hope in patients with multiple sclerosis referred to the MS Society of Zahedan, Iran. Neuropsychiatria i Neuropsychologia/neuropsychiatry and Neuropsychology, 16(3), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.5114/nan.2021.113317

Ramazani, B., & Bakhtiari, F. (2019). Effectiveness of spiritual therapy on cognitive avoidance, psychological distress and loneliness feeling in the seniors present at nursing homes. Journal of Gerontology, 3(4), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.29252/joge.3.3.32

Rattray, J., & Jones, M. C. (2007). Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(2), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01573.x

Rodrigues, W. S., Badagnan, H. F., Nobokuni, A. C., Fendrich, L., Zanetti, A. C. G., Giacon, B. C. C., & Galera, S. A. F. (2021). Family nursing practice scale: Portuguese language translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation. Journal of Family Nursing, 27(3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/10748407211002152

Salimi, T., Tavangar, H., Shokripour, S., & Ashrafi, H. (2017). The effect of spiritual self-care group therapy on life expectancy in patients with coronary artery disease: An educational trial. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, 15(10), 917–928. in Persian.

Taets, G. G. D. C. C., & Fernandes, C. (2020). Biological effects of music in cancer patients: Contributing to an evidence-based practice. International Journal of Sciences, 9(04), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.18483/ijSci.2302

Tinsley, H. E., & Brown, S. D. (2000). Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. Academic Press.

Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., Ghahremanian, A., Musavi, S., Akbarbegloo, M., & Chou, F.-Y. (2020). Experience of adolescent survivors of childhood cancer about self-care needs: A content analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 7(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_47_19

Waltz, C. F., Strickland, O., & Lenz, E. R. (2010). Measurement in nursing and health research. Springer.

White, M. L. (2016). Spirituality self-care practices as a mediator between quality of life and depression. Religions, 7(5), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7050054

White, M. L., & Schim, S. M. (2013). Development of a spiritual self-care practice scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 21(3), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.21.3.450

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all participants who contributed to this study, as well as the invaluable support and collaboration from Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (Project No: 401000414). In addition, this work was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R76), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The funding body did not play a role in the study's design or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD designed the study. AN, AM, XT, MAF, and BB conducted the search and data collection. MD analyzed data collection. MD, AN, AM and XT drafted the manuscript. MD, MAF, and BB revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Najmadini, A., Malakoutikhah, A., Tian, X. et al. Psychometric Evaluation of the Persian Version of Spiritual Self-Care Practice Scale in Iranian Patients with Cancer. J Relig Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-024-02066-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-024-02066-9