Abstract

Pain of cancer had various significant side effects that based on the literature it can reduced by religious coping methods. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between religious coping and pain perception in Iranian cancer patients. In this cross-sectional study (October–December, 2015), 380 hospitalized cancer patients were entered to the study using accessible sampling. Data were collected by socio-demographic, Religious Coping and McGill pain questionnaires. Males (48.39 ± 13 ± 39; CI95: 46.41–50.38) are older than females (45.33 ± 18.44; CI95: 42.79–47.87). According to results, there was a significant relationship between pain perception and positive religious coping in cancer patients. Also there was a significant relationship between pain perception and family history of cancer (P < 0.05). It seems that improving the level and quality of positive religious affiliation can be effective on the amount of stimulation and pain of cancer patients. Of course, more comprehensive studies are needed to be achieved more reliable results about the effects of religious coping on pain perception in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer as one of the most chronic diseases is often associated with the experience of severe pain (Rose et al. 2012). Cancer pain can have many different causes, including tumor growth and spread, side effects of therapies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery, and the underlying diseases (Falk and Dickenson 2014; Goudarzian et al. 2017b). The prevalence of pain varies from 5% in patients with leukemia to 85% in patients with primary bone tumors (Berger et al. 2015). There are several ways to treat and relieve pain in these people, but these methods do not seem to be sufficient to manage pain in these people (Gauthier et al. 2014). On the one hand, today more attention has been paid to the control and management of chronic pain; therefore, it seems that different strategies should be considered (Rosenberg et al. 2008).

In the meantime, religious coping is of greatest interest (Glover-Graf et al. 2007). Religious coping is one of the methods coping behavior which includes concepts such as praying and trusting God (Feder et al. 2013). Positive religious coping is the style of people in dealing with negative life events by which a person with the help of God will deal with those events. But in negative coping, avoidance and uncertain relationship of the individual with God is measured (Bagheri-Nesami et al. 2010; Heydari-Fard et al. 2012; Pargament and Hahn 1986). According to the existing theories, the researchers concluded that religious coping behavior makes it easier on patients to cope with illness and control it and also these behaviors significantly prevent mental disorders such as depression and pain (Bagheri-Nesami et al. 2010; Goudarzian et al. 2017a; Ramirez et al. 2012).

Background

Gate control theory of pain and neuromatrix theory of pain stated that there is an association between biological and psychological factors of patients. It is believed that pain is something more than transfers between the brain and spinal cord and psychological factors such as emotion and behavior can be effective in relieving pain (Melzack 1999). Another study also stated that praying (61%) after medication (89%) is the most common way to control chronic pain (Glover-Graf et al. 2007). The relationship between religious coping and pain is not only an increasingly important research prerogative, but it is also clinically relevant, particularly in light of the mandate by The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations to assess pain levels in all medical encounters. A recent review of the literature on religious coping in chronic pain populations revealed that in three different survey studies, prayer was either the primary or second most frequently used coping strategy used to deal with physical pain (Koenig 2001; Rippentrop 2005). In Koenig (2001) review of the literature, it was noted that four of the six cross-sectional studies reviewed reported a positive association between prayer and pain. It was postulated that this relationship reflects an increase in praying in response to pain. Also Rippentrop (2005) discussed the six cross-sectional studies that have examined religious coping as a means of coping with pain. Five of the six studies used the same Praying or Hoping subscale on the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (Rosenstiel and Keefe 1983) to measure religious coping. Interestingly, in some studies high scores on this subscale were related to more functional impairment, self-reported disability, and higher pain levels (Rapp et al. 2000; Rosenstiel and Keefe 1983), whereas in other studies high scores were associated with reduced pain and greater psychological well-being and positive affect (Abraído-Lanza et al. 2004; Bush et al. 1999).

Based on the literature review that was considered in background, there were inconsistent results about this issue in various studies. Also based on the available databases, there were no similar studies that were done in Iranian cancer patient. So, this study was carried out to investigate the relationship between religious coping behaviors and pain perception in cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Design

In this cross-sectional study (October to December, 2015), 380 cancer patients that were admitted to special unit of cancer in Imam Khomeini hospital (Sari, Iran) were entered to the study using accessible sampling. In this interval of 4 months, about 600 patients were admitted to the oncology ward of these hospitals. Inclusion criteria included age (18 years or older), cancer treatment with radiation, chemotherapy or surgery. Patients who were excluded from the study included those: taking antidepressants in the last 6 months, the transfer of patients to other hospitals, and occurrence of acute medical conditions (such as loss of consciousness). No participants were excluded from study. Of the remaining 600 eligible participants, 380 ones were accepted for participation. The rate of patient participation was 63.3%.

After explaining the purpose of the study and how to complete the questionnaire, informed consent form was signed by qualified patients. Then, the necessary explanation regarding the objectives of the study was given to patients and the questionnaires were distributed. Explanation was given to the patients if a question was vague. It should be noted this explanation was only in order to avoid ambiguity and without any kind of bias.

Instruments

Data were collected by socio-demographic questionnaire, McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), and Religious Coping Questionnaire (RCOPE). Socio-demographic questionnaire includes age, sex, education level, economic status, history of opioid drug use, family history of cancer, and stage of the cancer.

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

MPQ includes 78 descriptive sentences out of 20 collections (Gauthier et al. 2014). The patients were asked to select the best description of their pain with just one word from each group. If all options of a group do not provide an appropriate description of pain, the patient would not choose an option from this group. When patients chose more than one option in each group, the highest rating (maximum pain) was chosen for the final analysis (Berger et al. 2015). The score of each group was collected separately to calculate the final score. MPQ total score is described as “pain rating index based on the scores of the words”; the result is the sum of the scores of each group (Melzack 1975). Scores range varies from 0 (when no word is selected) to 78 (maximum pain when selected in each group) (Berger et al. 2015). Based on cut point, scores were categorized (0–19.5 [low pain], 19.5–39 [average pain], 39–58.5 [high pain], and 58.5–78 [severe pain]). Dworkin et al. (2015) calculated the reliability of this tool to be 0.77 using Cronbach’s alpha. In the present study, the reliability of this tool was calculated to be 0.94 using Cronbach’s alpha.

Religious Coping Questionnaire (RCOPE)

Religious coping methods were investigated using RCOPE. This standard questionnaire had 14 items to measure positive and negative religious coping, and it was made by Kenneth Pargament (Stefan et al. 1996). Each positive and negative scale included 7 option of religious coping test. Scoring method is in the form of Likert from “not at all” to “many times.” Positive religious coping is a style of dealing with negative life events in which a person using the evaluation and positive changes associated with God deals with those events. A person believes that God will not abandon them when confronting sad events. But the other form of coping which is called negative coping, a person establishes an avoidant and insecure relationship with God. For example, one believes that God will leave them alone in difficult moments (Ramirez et al. 2012). In the study of Bagheri Nesami et al. (2015) on university students, an acceptable reliability for this tool was reported (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (Ethics code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.95.S.109). Patients were informed about study aims and procedures, that participation was voluntary, and would not affect medical care before signing an informed consent document. Patient confidentiality was assured by completing all study procedures in a quiet treatment area. To ensure that a broad cross-section of patients were allowed to participate in the study, a trained research assistant who was part of the study team provided support as needed. All personal data were de-identified by assigning codes to the participants.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical package for social sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was utilized for data analysis. First descriptive statistics for continuous variables were shown as means with standard deviation (SD) and n (%) for the categorical variables. Spearman’s correlations were used to probe the relationship between religious coping and pain perception. Finally, the predictors associating with pain perception were determined using generalized linear models (GLM). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Participants’ Profile

Demographic characteristics of 380 cancer patients are summarized in Table 1. Males (48.39 ± 13 ± 39; CI95: 46.41–50.38) are older than females (45.33 ± 18.44; CI95: 42.79–47.87). The mean total score of pain perception, negative and positive religious coping were (21.61 ± 13.55; CI 95% 20.36–22.17), (18.22 ± 3.25; CI95: 18.12–18.74) and (18.43 ± 3.11; CI95: 17.89–18.55), respectively. In total, 69.9% of patients under treatment had depression in early stages of disease.

Relationship Between Religious Coping and Pain

The results of spearman correlation analysis suggested that there was a negative and significant correlation between positive religious coping and pain (r = −0.424, P = 0.009). Also positive relationship was found between negative religious coping and pain perception (r = 0.25, P = 0.009). According to the results of generalized linear regression models in Table 2, there is a significant relationship between pain perception and positive religious coping in cancer patients (B = −2.092; P = 0.001). In addition, there is a significant relationship between pain perception and economic status (P < 0.05), sex (B = −6.389; P < 0.001), opioid drug use history (B = 8.907; P = 0.001), and family history of cancer (B = −9.230; P = 0.001) in cancer patients.

Discussion

Based on the results of the study, the average score of pain in cancer patients has been moderate to low which was consistent with the findings of several studies (Bradley et al. 2005; Breivik et al. 2009; Gupta et al. 2015; Stromgren et al. 2004; van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al. 2007). It should be noted that the difference in the perception of pain in various studies can also vary according to the type of cancer and its stage (Bennett et al. 2012). It may be stated that in most cases, factors such as lack of knowledge or fear of strong opioids and side effects induced by them cause pain not to be treated effectively in these patients and even be further felt (Jain et al. 2015). Based on the findings, the level of religious coping in cancer patients was moderate. Also the level of positive religious coping compared with negative religious coping among patients in this study had higher rates that the results of Ursaru et al. (2014) and Khodaveirdyzadeh et al. (2016) were also in line with the results of this study. On the one hand, Nelson et al. (2002), McCoubrie and Davies (2006), and Khezri et al. (2015) also stated that the level of negative religious coping during the study in cancer patients compared to the positive coping had higher rates. The possible causes of the differences in the studies mentioned can be cultural and religious differences of cases under study (Rezaei et al. 2009), type and stage of cancer, and the study environment.

One of the most important results of the present study is a significant negative correlation between pain perception and positive religious coping in cancer patients. This finding is consistent with studies of Abernethy et al. (2002), Fenix et al. (2006), Zwingmann et al. (2006), Wachholtz et al. (2007), Delgado-Guay et al. (2013), and Haghighi (2013). Also, Rowe and Allen (2004) in a study stated that strong religious beliefs are associated with lower levels of pain. Probably the religious and spiritual ideas help cancer patients to adapt with various effects of diagnosis and treatment, especially chemotherapy (Tatsumura et al. 2003). Among the possible mechanisms associated with the existence of these connections, one can refer to gate control theory of pain and neuromatrix theory of pain (Ramirez et al. 2012) that based on the aforementioned theories there is an association between psychological and biological factors of patients. It is also believed that the use of religious coping to deal with life’s problems and crisis increases tolerance and acceptance of unchangeable situations (Taheri-Kharameh et al. 2013). Therefore, we can mention the inevitable role of religious and spiritual coping in better dealing and compatibility with unbearable consequences of chronic diseases such as perception of pain.

In the present study, there was a significant relationship between pain perception, economic status, gender, family history of cancer, history of drug use that the results are consistent with the findings of Sherman et al. (2011). The results of the study of Ham et al. (2016) showed a significant and positive relationship between economic status and perception of pain, but in another study no relationship was found between the variable of gender and the amount of pain perception. Possible causes of this paradox can be cultural differences, sample size, and environment of the study.

Limitations

The most important limitation of this study was had no access to patients in other hospitals in the Mazandaran province and the country, so because of the small sample size, it is difficult to generalize the results correctly. The other one is cultural differences of the patients which were not controllable in this study. Impatience and imprecision of some of the patients at the completion of questionnaire due to disease-related treatments can affect the results. Because of the importance of this issue, it is suggested that this study be conducted in the future more frequently and with greater span on cancer patients.

Implication of Results

This research provides information about Iranian cancer patients that may help to inform the development of strategies to promote better disease adaptation. It also fills a gap in the cancer literature by reporting quantitative data on coping styles relative to pain perception. Since cancer patients are affected with a variety of complications during their life which undermine their quality of life and given that coping behaviors (specially positive religious coping) improve the level of health and decrease the grades of pain perception in these patients, it is necessary to improve all caution and measures to improve the level of positive religious coping in these people. According the present results, it seems that relying on religious issues and religious coping methods (especially the positive religious coping) and having a sense of satisfaction and pleasure about the happened events can significantly help in decreasing the level of pain perception in patients. Therefore, it is required that pay attention given to the issues of religious coping along with other helping care at health centers.

Conclusion

According to the findings of the present study, the average score of pain in cancer patients was moderate and also the level of positive religious coping compared with negative religious coping among these patients had higher rates in this study. In addition, the findings indicate significant negative relationship between pain perception and positive religious coping in cancer patients. It seems that raising the level and quality of religious affiliation can positively affect the amount of stimulation and pain. However, more comprehensive research is needed to ensure more reliable results.

References

Abernethy, A. D., Chang, H. T., Seidlitz, L., Evinger, J. S., & Duberstein, P. R. (2002). Religious coping and depression among spouses of people with lung cancer. Psychosomatics, 43(6), 456–463.

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Vásquez, E., & Echeverría, S. E. (2004). En las manos de Dios [in God’s hands]: Religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 91.

Bagheri Nesami, M., Goudarzian, A. H., Zarei, H., Esameili, P., Dehghan Pour, M., & Mirani, H. (2015). The relationship between emotional intelligence with religious coping and general health of students. Materia Socio Medica, 27(6), 412–416.

Bagheri-Nesami, M., Rafii, F., Oskouie, H., & Fatemeh, S. (2010). Coping strategies of Iranian elderly women: A qualitative study. Educational Gerontology, 36(7), 573–591.

Bennett, M. I., Rayment, C., Hjermstad, M., Aass, N., Caraceni, A., & Kaasa, S. (2012). Prevalence and aetiology of neuropathic pain in cancer patients: A systematic review. Pain, 153(2), 359–365.

Berger, M. B., Damico, N. J., & Haefner, H. K. (2015). Responses to the McGill Pain Questionnaire predict neuropathic pain medication use in women in with vulvar lichen sclerosus. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 19(2), 135–139.

Bradley, N., Davis, L., & Chow, E. (2005). Symptom distress in patients attending an outpatient palliative radiotherapy clinic. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 30(2), 123–131.

Breivik, H., Cherny, N., Collett, B., de Conno, F., Filbet, M., Foubert, A. J., et al. (2009). Cancer-related pain: A pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Annals of Oncology, 20(8), 1420–1433.

Bush, E. G., Rye, M. S., Brant, C. R., Emery, E., Pargament, K. I., & Riessinger, C. A. (1999). Religious coping with chronic pain. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 24(4), 249–260.

Delgado-Guay, M. O., Parsons, H. A., Hui, D., Cruz, M. G. D. L., Thorney, S., & Bruera, E. (2013). Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 30(5), 455–461.

Dworkin, R. H., Turk, D. C., Trudeau, J. J., Benson, C., Biondi, D. M., Katz, N. P., et al. (2015). Validation of the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 (SF-MPQ-2) in acute low back pain. Journal of Pain, 16(4), 357–366.

Falk, S., & Dickenson, A. H. (2014). Pain and nociception: Mechanisms of cancer-induced bone pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(16), 1647–1654.

Feder, A., Ahmad, S., Lee, E. J., Morgan, J. E., Singh, R., Smith, B. W., et al. (2013). Coping and PTSD symptoms in Pakistani earthquake survivors: Purpose in life, religious coping and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1), 156–163.

Fenix, J. B., Cherlin, E. J., Prigerson, H. G., Johnson-Hurzeler, R., Kasl, S. V., & Bradley, E. H. (2006). Religiousness and major depression among bereaved family caregivers: A 13-month follow-up study. Journal of Palliative Care, 22(4), 286–292.

Gauthier, L. R., Young, A., Dworkin, R. H., Rodin, G., Zimmermann, C., Warr, D., et al. (2014). Validation of the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 in younger and older people with cancer pain. The Journal of Pain, 15(7), 756–770.

Glover-Graf, N. M., Marini, I., Baker, J., & Buck, T. (2007). Religious and spiritual beliefs and practices of persons with chronic pain. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 51(1), 21–33.

Goudarzian, A. H., Bagheri Nesami, M., Zamani, F., Nasiri, A., & Beik, S. (2017a). Relationship between depression and self-care in Iranian patients with cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 18(1), 101–106.

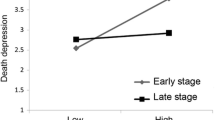

Goudarzian, A. H., Jafari, A., Bagheri Nesami, M., & Zamani, F. (2017b). Understanding the link between depression and pain perception in Iranian cancer patients. World Cancer Research Journal, 4(2), e880.

Gupta, M., Sahi, M. S., Bhargava, A. K., & Talwar, V. (2015). The prevalence and characteristics of pain in critically ill cancer patients: A prospective nonrandomized observational study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 21(3), 262–267.

Haghighi, F. (2013). Correlation between religious coping and depression in cancer patients. Psychiatria Danubina, 25(3), 0–240.

Ham, O.-K., Chee, W., & Im, E.-O. (2016). The influence of social structure on cancer pain and quality of life. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 0193945916672663.

Heydari-Fard, J., Bagheri-Nesami, M., & Mohammadpour, R. A. (2012). Association between quality of life and spiritual well-being in community dwelling elderly. Life Science Journal, 9(4), 3198–3204.

Jain, P. N., Pai, K., & Chatterjee, A. S. (2015). The prevalence of severe pain, its etiopathological characteristics and treatment profile of patients referred to a tertiary cancer care pain clinic. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 21(2), 148–151.

Khezri, L., Bahreyni, M., Ravanipour, M., & Mirzaee, K. (2015). The relationship between spiritual wellbeing and depression or death anxiety in cancer patients in Bushehr 2015. Nursing of the Vulnerables, 2(2), 15–28.

Khodaveirdyzadeh, R., Rahimi, R., Rahmani, A., Ghahramanian, A., Kodayari, N., & Eivazi, J. (2016). Spiritual/religious coping strategies and their relationship with illness adjustment among iranian breast cancer patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 17(8), 4095–4099.

Koenig, H. G. (2001). Religion and medicine IV: Religion, physical health, and clinical implications. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 31(3), 321–336.

McCoubrie, R. C., & Davies, A. N. (2006). Is there a correlation between spirituality and anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer? Supportive Care in Cancer, 14(4), 379.

Melzack, R. (1975). The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain, 1(3), 277–299.

Melzack, R. (1999). From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain, 82, 121–126.

Nelson, C. J., Rosenfeld, B., Breitbart, W., & Galietta, M. (2002). Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics, 43(3), 213–220.

Pargament, K. I., & Hahn, J. (1986). God and just world: Causal and coping attribution to god in health situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 25, 193–207.

Ramirez, S. P., Macêdo, D. S., Sales, P. M. G., Figueiredo, S. M., Daher, E. F., Araújo, S. M., et al. (2012). The relationship between religious coping, psychological distress and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(2), 129–135.

Rapp, S. R., Rejeski, W. J., & Miller, M. E. (2000). Physical function among older adults with knee pain: The role of pain coping skills. Arthritis Care and Research, 13(5), 270–279.

Rezaei, M., Seyedfatemi, N., & Hosseini, F. (2009). Spiritual well-being in cancer patients who undergo chemotherapy. Hayat, 14(4), 33–39.

Rippentrop, A. E. (2005). A review of the role of religion and spirituality in chronic pain populations. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(3), 278.

Rose, L., Smith, O., Gélinas, C., Haslam, L., Dale, C., Luk, E., et al. (2012). Critical care nurses’ pain assessment and management practices: A survey in Canada. American Journal of Critical Care, 21(4), 251–259.

Rosenberg, E. I., Genao, I., Chen, I., Mechaber, A. J., Wood, J. A., Faselis, C. J., et al. (2008). Complementary and alternative medicine use by primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 9(8), 1065–1072.

Rosenstiel, A. K., & Keefe, F. J. (1983). The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: Relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain, 17(1), 33–44.

Rowe, M. M., & Allen, R. G. (2004). Spirituality as a means of coping with chronic illness. American Journal of Health Studies, 19(1), 62.

Sherman, K. J., Cherkin, D. C., Wellman, R. D., Cook, A. J., Hawkes, R. J., Delaney, K., et al. (2011). A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(22), 2019–2026.

Stefan, G., Detlev, Z., Christoph, D., Lukas, R., & Klaus, Azan. (1996). Assessment of cancer pain: A prospective evaluation in 2266 cancer patients referred to a pain service. Pain, 64(1), 107–114.

Stromgren, A. S., Groenvold, M., Petersen, M. A., Goldschmidt, D., Pedersen, L., Spile, M., et al. (2004). Pain characteristics and treatment outcome for advanced cancer patients during the first week of specialized palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 27(2), 104–113.

Taheri-Kharameh, Z., Saeid, Y., & Ebadi, A. (2013). The relationship between religious coping styles and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Iranian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2(1), 24–32.

Tatsumura, Y., Maskarinec, G., Shumay, D. M., & Kakai, H. (2003). Relegious and spiritual resources, CAM, and conventional treatment in the lives of cancer patients. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 9(3), 64.

Ursaru, M., Crumpei, I., & Crumpei, G. (2014). Quality of life and religious coping in women with breast cancer. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 322–326.

van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M. H., de Rijke, J. M., Kessels, A. G., Schouten, H. C., van Kleef, M., & Patijn, J. (2007). High prevalence of pain in patients with cancer in a large population-based study in The Netherlands. Pain, 132(3), 312–320.

Wachholtz, A. B., Pearce, M. J., & Koenig, H. (2007). Exploring the relationship between spirituality, coping, and pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(4), 311–318.

Zwingmann, C., Wirtz, M., Müller, C., Körber, J., & Murken, S. (2006). Positive and negative religious coping in German breast cancer patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(6), 533–547.

Acknowledgements

Nurses, doctors, patients, and all those who helped in carrying out this study are sincerely appreciated. The project was approved by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences’ ethics committee, Sari, Iran.

Funding

Student research committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences financially supported this study (Grant No: 236 approved in 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goudarzian, A.H., Jafari, A., Beik, S. et al. Are Religious Coping and Pain Perception Related Together? Assessment in Iranian Cancer Patients. J Relig Health 57, 2108–2117 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0471-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0471-4