Abstract

Growing older often brings hardship, adversity, and even trauma. Resilience is a broad term used to describe flourishing despite adversity. To date, resilience and the connections to religion have not been well studied, despite compelling evidence that religious practice can promote psychological health. This research examines the role that religion plays in promoting resilience among older adults. Research questions include: (a) What is the relationship between religion and trait resilience? and (b) Does religion promote resilient reintegration following traumatic life events? Results indicate that religious service attendance is tied to higher levels of trait resilience and that both service attendance and trait resilience directly predict lower levels of depression and higher rates of resilient reintegration following traumatic life events. Findings suggest that religious service attendance has protective properties that are worthy of consideration when investigating resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Traversing a life course means encountering a myriad of life events, some of which will inevitably afford opportunities for growth and advancement, while others will be sources of hardship, adversity, and even trauma. Some individuals leave these challenges marked with emotional scars, while others recover and even thrive in the face of difficulty. Those who recover well are often called “resilient,” though scholarly work on the topic has shown this to be a multidimensional term with varying definitions. In broad brushstrokes, however, resilience can be described as the capacity to navigate adversity in a manner that protects health, well-being, and life satisfaction (xxx—blinded). Understanding resilience generates new insights into human potential and offers new and deeper understandings of how individuals recover from adversity and sustain healthy growth and functioning (Reich et al. 2010; Zraly and Nyirazinyoye 2010). Given the promise of resilience, we might ask: what factors determine whether people flourish or languish when encountering these events? What circumstances increase the likelihood of individuals having, cultivating, and sustaining resilience?

Introduction

In the last decade, scholars have identified several pathways to resilience, including social support (Helgeson and Lopez 2010), volunteering and philanthropy (Hughes 2010), and maintaining positive affect (Moskowitz 2010). Until recently, however, less effort has been made to determine whether and how religion might contribute to resilience (Faigin and Pargament 2011); Pargament and Cummings 2010). This is surprising, given that religion researchers have amassed substantial evidence that religion can benefit both physical and mental health (Ferraro and Albrecht-Jensen 1991; George et al. 2002; Idler 1997; Koenig 2002; Seery 2011). It therefore seems likely that religion might play an important role in promoting resilience, but to date this connection has yet to be adequately established.

Using two waves of nationally representative data on older adults, the present research examines the relationship between religion and resilience. Older adults are a useful population for studying resilience, as advancing age often brings with it physical, social, and emotional hardships. Older adults also tend to be more religious than the young, making them a particularly appropriate group for addressing the present question. We begin by presenting theoretical reasons for positing that religion is likely to bolster resilience and then present analyses that test our claims. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our work.

Key Concepts and Definitions of Resilience

Before exploring the religion/resilience connection, it is important to advance a workable definition of resilience. This is not a simple task, as work on resilience over the last decade reflects considerable variation and complexity in definitions and conceptualizations, both in popular and academic discourse (Reich et al. 2010). Early work on resilience rested largely on conceptualizations from developmental psychology (Luthar 2006), but recently the study of resilience has gained popularity in the biological, sociological, anthropological, and gerontological arenas as well. Each of these areas has offered new understandings of resilience, but the influx of insights has spurred debates regarding definition and measurement (Arrington and Wilson 2000; Lavretsky 2014). For instance, resilience has been conceptualized as a set of traits (e.g., hardiness, tough-mindedness), an outcome (e.g., better than expected happiness or satisfaction in the face of challenges), and a process (e.g., effective coping in the face of difficulty) (Lavretsky and Irwin 2007).

Scholars have attempted to reconcile these perspectives. One approach has been to downplay the problem. Mancini and Bonanno (2010) argued that as a conceptual matter, these distinctions (trait, outcome, or process) make little difference in the operational understanding of resilience. Furthermore, they argue these different usages reflect the different questions being asked, populations being studied, and the duration of adversities and traumas under investigation. Another tactic—arguably the most dominant—has been to view resilience as multifaceted construct (Clark et al. 2010), which at one level is a “fluid [and] dynamic” process, albeit “not fully understood” (Greene 2002, p. 41), that involves the ability to adapt or “bounce back” (that is, obtain positive outcomes) following adversity or challenge (see also Luthar et al. 2000; Reich et al. 2010). This bouncing back connotes several traits including inner strength, competence, optimism, flexibility, and the ability to effectively cope when faced with adversity (Wagnild and Collins 2009).

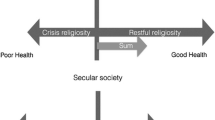

Richardson’s Model of Resilience is one attempt to theorize the interconnections between the process and outcome aspects of resilience (see Fig. 1). According to Richardson (2002), a person begins movement across the life course at a state of physical, mental, and spiritual homeostasis. Life events—such as life transitions, major loss, or trauma—disrupt this homeostasis, though the extent of disruption is moderated by protective factors, such as coping abilities and social support. Those who have experienced disruption are then faced with the challenge of reintegrating their lives; Richardson posits that this can occur in one of four ways. Dysfunctional reintegration occurs when disruptions leave a lasting mark on a people’s ability to function, such as when individuals lose their will to live after the death of a spouse. Alternately, people recover to a degree, but never fully recapture the former richness their lives—this is reintegration with loss. They might, for instance, shun social contacts that had previously given them great enjoyment. A third possibility is that people regain the level of functionality and happiness that they had prior to their loss—this is reintegration back to homeostasis. Finally, people can emerge stronger than before, suggesting resilient reintegration.

Richardson’s resilience model (Richardson 2002)

Note that this model explicitly represents resilience as process and an outcome, consistent with the multifaceted nature of resilience outline above. The process component is evident in that disruption and reintegration unfold in time, while resilience as an outcome is represented by homeostatic and resilient reintegration. Trait approaches to resilient do not appear in the model explicitly, but can be added with little difficulty. Resilience traits, for example, might act as protective factors that diminish the impact of negative life events, or serve as resources to facilitate resilient reintegration after disruption.

Findings from several studies are consistent with this understanding of Richardson’s Resiliency Model, though few have examined the model explicitly. For example, some researchers have shown that traits including ability to forgive, high morale, purpose in life, sense of coherence, self-transcendence, and self-efficacy are associated with resilient outcomes (Broyles 2005; Wagnild and Young 1993; Nygren et al. 2005; Zeng and Shen 2010). Similarly, trait resilience is inversely associated with depression, perceived stress, and anxiety, possibly because resilience is acting as a protective factor (Wagnild 2009; Wagnild and Young 1993; Humphreys 2003). Other work has more directly addressed the reintegration phase, identifying resources that promote resilient reintegration. Bachay and Cingel, for instance, (1999) found that past experiences with hardship and meaningful relationships led women to consciously adopt strategies for overcoming present adversities that ultimately led to positive growth and development.

Resilience and Religion in Later Life

To date, resilience has largely been studied at earlier stages of the life course. There are compelling reasons, however, to examine resilience in later life. First, older adults are increasing in number and living longer, but they vary considerably in how well they cope with the challenges associated with aging. Studying resilience can help us better understand why some older adults flourish when faced with adversity and hardship and others do not. Second, older adults inevitably experience decline and loss over the life course; practically, this means that adversity is a defining feature of this demographic group, making resilience a central concern (Resnick et al. 2011). Finally, encountering multiple adversities means that older adults repeatedly face the task of reintegration. This makes them an ideal group for testing the theoretical mechanisms described in Richardson’s model. Currently, we know very little about how reintegration occurs, and what factors facilitate the process.

There are reasons to believe religion can help us understand resilience among older adults. In part, this is because religion often plays an important role in their lives. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2009) reports that religion is “very important” for 69% of adults 65 and older, compared to 45% of those age 30 and younger. There is also a substantial body of research showing that religious participation is (typically) positively related to mental and physical health in mid-to-late-life (Ellison and Levin 1998; Hill 2010). For example, research has shown that religious involvement is tied to reduced mortality (e.g., Hummer et al. 1999), buffers the risk for illness (e.g., Koenig et al. 1999; George et al. 2002), and reduces the likelihood of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and substance abuse (Koenig et al. 1994, 1997; Rote et al. 2013). The benefits of religious involvement combined with the prevalence of religion in the lives of older adults suggest that work on resilience can benefit from more fully considering the role religion might play. A few studies have directly examined religion and resilience (Faigin and Pargament 2011; Pargament and Cummings 2010), but we still know little about how the two interact.

We argue that religion enters the resilience process in at least two ways. First, religion can provide resources for developing an adaptive approach to life, or in other words, the “hardy” mindset that defines trait resilience. Religious outlooks can provide a sense of meaning and purpose that render life events more interpretable. For example, religion can facilitate discovery of the positive from the negative by helping individuals to reframe events in positive ways, such as seeing negative events as lessons from a loving God that will ultimately benefit the individual, or as opportunities for personal growth (Ardelt et al. 2008; Carrico et al. 2006; Pargament and Park 1995; Park and Cohen 1993). Religion has also been linked to other beneficial coping strategies, such as active problem-solving, though admittedly some individuals use religion to cope passively as well (Pargament and Park 1995; van Uden et al. 2009). Additionally, religious participation predicts higher levels of psychosocial resources such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, and possibly mastery, all of which buffer the effects of negative life events (George et al. 2002; Schieman 2008). These resilient traits in turn should help individuals to cope with and recover from challenging life events, allowing them to experience resilient outcomes such as—in Richardson’s terms—a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration.

Second, religion can provide social support and material resources that empower people to effectively manage negative events, leading to a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration. It is plausible that religion could also serve as a protective factor that mitigates exposure to certain challenges and traumas, such as having a family member addicted to drugs, combat, marital infidelity. Religious involvement encompasses not only specific worldviews and subscription to sets of principles, beliefs, and values, but also entails socially shared, collectively maintained, communally practiced experiences (Berger 1967). Brewer-Smyth and Koenig (2014) suggested that religion is a powerful mechanism in buffering resilience through both these intrinsic and extrinsic types of social supports. For example, intrinsic social support could come from perceived comfort and reassurance with one’s relationship with divine, whereas external support could be derived from the relationships with others in the shared faith community in form of giving to and receiving from others. While the role of religion in fostering social support is plausible, relatively few studies have directly examined this claim, though those that have support it. Ellison and George (1994), for example, examined the extent to which religion participation enhanced the social resources for individuals and found that those who frequently attended religious services had more contact with network members, more types of social supports, and reported better quality of and satisfaction with those relationships than those who attended less frequently. More recently, Hovey et al. (2014) showed that intrinsic religiosity predicts religious-based emotional support, which in turn reduces hopelessness, depression, and suicide behaviors.

The research presented here investigates the way that religion can promote resilient outcomes in later life, where resilient outcomes are defined as flourishing despite adversity (Hildon et al. 2008, 2010). Specifically, we operationalize adversity as recent traumatic experiences, and “flourishing” as levels of depression lower than pre-trauma levels. Social and material aspects of religion are measured using frequency of attendance at religious services, while the psychosocial resources religion provides are measured as endorsement of religious beliefs that might aid coping. Guiding research questions are: What role does religion play in moderating the negative impacts of late-life trauma on depression? To what extent does religion increase opportunities for resilient reintegration? Given the discussion above, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1a

Religious psychosocial resources (beliefs) will be negatively related to depression.

Hypothesis 1b

Religious service attendance will be negatively related to depression.

Hypothesis 1c

Trait resilience will be negatively related to depression.

Hypothesis 2a

The relationship between religious psychosocial resources and depression will be mediated by trait resilience.

Hypothesis 2b

The relationship between religious service attendance and depression will be mediated by social support.

Hypothesis 3a

Religious psychosocial resources will decrease the negative relationship between trauma and depression.

Hypothesis 3b

Religious service attendance will decrease the negative relationship between trauma and depression.

Hypothesis 3c

Trait resilience will decrease the negative relationship between trauma and depression.

Hypothesis 4a

Religious psychosocial resources will be positively related to a return to homeostasis and resilient reintegration among older adults who have experienced at least one trauma.

Hypothesis 4b

Religious service attendance will be positively related to a return to homeostasis and resilient reintegration among older adults who have experienced at least one trauma.

Hypothesis 4c

Trait resilience will be positively related to a return to homeostasis and resilient reintegration among older adults who have experienced at least one trauma.

Hypothesis 5a

The relationship between religious psychosocial resources and a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration will be mediated by trait resilience.

Hypothesis 5b

The relationship between religious service attendance and a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration will be mediated by social support.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

The data for this study come from the 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative panel survey of non-institutionalized adults that began in 1992, and have been supplemented over the years by new samples of different age cohorts. The data used for this project are a representative sample of non-institutionalized adults who were born before 1954 and their spouses. The survey collects detailed information on respondents’ demographic, housing, household and family, economic, and health status characteristics, cognitive status, employment, and wealth. Detailed explanations of the data, including sampling methods, weights, and lists of variables, can be found in the codebooks and manuals produced by the Institute of Social Research at the University of Michigan (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/).

The sample for the present analyses consists of adults who completed the leave-behind questionnaires (LBQs) administered as part of the HRS data collection in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012. We used the leave-behind questionnaires as the inclusion criteria because they contain data on lifetime traumas and religious service attendance. Respondents were randomly assigned to receive the LBQ in either 2006 and 2010, or 2008 and 2012. This creates two “waves” of responses, with the first wave pooling respondents from 2006 and 2008, and the second wave capturing the same respondents in either 2010 or 2012. The sample was restricted to respondents who completed the LBQ at both waves, had nonzero sampling weights and—to maintain a focus on older adults—who were at least 65 years of age in the first wave, leaving a final sample of 7532. Missing data were accounted for using full information maximum likelihood (FIML), which returns unbiased parameter estimates under weaker assumptions than listwise deletion, and is likewise more efficient than listwise deletion (Enders 2010). For one analysis, FIML was not possible (noted in a footnote below), and multiple imputation was used instead (with 20 imputed data sets). Multiple imputation has the same properties of unbiasedness and efficiency as FIML (Enders 2010).

Measures

Dependent Variables: Depression

Depression was measured using the abbreviated version of the CESD used in the HRS (see documentation at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf). For analyses testing hypotheses 1–3b, CESD scores from each wave were standardized, and then, wave 1 scores were subtracted from wave 2 scores to capture changes in depression in the four-year period between waves.

For analyses testing hypotheses 4a–4c about reintegration, wave 2 scores were compared to wave 1 scores among those who had experienced at least one trauma between waves. Those whose wave 2 scores were higher than their wave 1 scores were coded as experiencing either dysfunctional reintegration or reintegration with loss (the two were coded into the same category), while those with equal scores were coded as having experienced a return to homeostasis. Finally, those whose wave 2 CESD scores were lower than their wave 1 scores were coded as having experienced resilient reintegration.

Primary Independent Variables: Trauma, Religious Involvement, and Trait Resilience

Trauma

The trauma measure is a count of the number of traumas respondents experienced between waves one and two, with counts of 5–7 recoded as four to avoid lending undue influence to individuals who experienced extreme amounts of trauma. Traumas include experiencing the death of a child, being the victim of a physical attack, experiencing a life-threatening illness, having a spouse or child experience a life-threatening illness, being in a fire or major disaster, firing a weapon in combat, and having a spouse or partner addicted to drugs.

Religious Involvement: Religious involvement is measured as attendance at religious services, with 0 = not at all and 4 = more than once a week. Attendance is measured at both wave 1 and wave 2, as well as in 2004 (prior to wave 1), with the exact measure used depending on the analysis. It should be noted that while it is plausible that experiencing traumatic events would cause people to increase their attendance at religious services, supplemental analyses (not shown) indicate that this is not the case in the present sample.

Religious Psychosocial Resources

Religious psychosocial resources are measured at wave 1 as agreement with the following statements: “I believe in a God who watches over me,” “The events in my life unfold according to a divine or greater plan,” “I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my other dealings in life,” and “I find strength and comfort in my religion.” Each statements was rated from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree, and then the four items were averaged to form a single scale (α = 0.92).Footnote 1

Trait Resilience

The HRS does not incorporate a detailed psychological investigation of resilience. Thus, we used a simplified resilience score (SRS) designed to capture adjustment and management of adversity. This simplified resilience score (SRS) is broadly guided by the Wagnild and Young Resilience Scale (RS) (1993) and has been used previously to examine resilience using HRS data (see—xxxx—blinded for a complete discussion of the development of the SRS). Five primary psychosocial domains informed development of the measure, paralleling the Wagnild and Young Scale: (1) perseverance, or the ability to keep going despite major setbacks; (2) equanimity, which describes being able to adjust to change, often with humor; (3) meaningfulness or the realization that life has a purpose; (4) self-reliance or recognition of one’s one inner strengths; and (5) existential aloneness or the realization that some experiences must be faced alone (Wagnild and Young 1993; Zeng and Shen 2010). Sample items include levels of agreement or disagreement with statements such as “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to do,” “When I really want to do something, I usually find a way to succeed at it,” and “There is really no way I can solve the problems that I have.” See Manning et al. (2016) for details on the construction of the scale. The SRS was measured at wave 1.

Social Support

The social support measure is a scale constructed from 5 items that tap feeling of emotional support from and contact with friends. Respondents rated how well understood they felt by their friends, how much they could rely on their friends, and how much they could open up to their friends on a scale of 0 = not at all to 3 = a lot, and how often they meet up with and speak on the phone with friends on a scale of 0 = less than once a year or never to 5 = three or more times a week. All variables were standardized and then averaged to form the final scale (α wave1 = 0.78, α wave2 = 0.78).Footnote 2

Control variables were chosen based on past research and to guard against selection effects. All control variables were measured at wave 1. These included dichotomous variables for being black, Hispanic, a non-white “other” race, married, female, and having one or more health insurance plans. Education was measured as years of education completed, and total wealth in dollars. Because health can influence religious service attendance, we also controlled for self-rated health in each year (1 = poor to 5 = excellent), the number of instrumental activities of daily living that respondents reported any difficulty with (e.g., using the phone, range of 0–5), and baseline depression (measured using wave 1 CESD scores). Including baseline depression also allowed us to control for any portion of our measure of trait resilience that also tapped depressive affect, and to adjust for effects at wave 1 of stressful conditions that might have preceded traumatic events experienced between waves (e.g., months of illness prior to the death of a child might have generated stress that affected wave 1 measures).Footnote 3 Finally, we controlled for selection into the sample separately for each age cohort by calculating inverse Mills ratios and including them in the analysis models.

Analytic Strategy

Analyses proceed in two phases. In the first, we use linear path models to test the relationships among religious psychosocial resources, religious service attendance, social support, and trait resilience at wave 1, and the relationships of all four with changes in depression between waves 1 and 2 (hypotheses 1a–1c, 2a–2b). We also examine whether trait resilience, psychosocial resources, and service attendance at wave 1 moderate the effects of traumas that occur between waves on changes in depression (hypotheses 3a–3c). The second phase uses a multinomial logit model to examine whether religious psychosocial resources and religious service attendance predict a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration (compared to dysfunctional reintegration or reintegration with loss) among those who experienced at least one trauma between waves (hypotheses 4a–4c), and whether these relationships are mediated by trait resilience and social support, respectively (hypotheses 5a–5b). Missing data were multiply imputed for this analysis.

All variables except dichotomous or nominal variables and the count of traumas experienced were standardized prior to analyses, and all models use the wave 1 person-level weights provided by HRS (i.e., for years 2006 and 2008, depending on the respondent) and cluster robust standard errors, with clusters defined by households.

Results

Figure 2 presents key results from a linear path model testing hypotheses 1a–1c and 2a–2b. As expected, traumas experienced after baseline predict increased depression by wave 2, with each additional trauma predicted to increase depression by 0.09 standard deviations (SD). Consistent with hypotheses 1b and 1c, both attendance at religious services and trait resilience are negatively related to depression, though religious psychosocial resources have no effect (hypothesis 1a). The effect of religious service attendance is small, with a 1 SD increase in service attendance predicting only a 0.03 decline in depression, but the estimate for trait resilience is much larger, with a 1 SD increase in trait resilience predicting a 0.16 SD decrease in depression. Religion also has indirect effects. A 1 SD increase in religious service attendance in 2004 predicts a 0.36 increase in religious psychosocial resources at wave 1, which in turn predicts increased trait resilience (β = 0.11). Thus, religious psychosocial resources predict lower depression through their relationship with trait resilience, consistent with hypothesis 2a. Religious service attendance at wave 1 is positively related to social support (β = 0.10) as are psychosocial resources to a small degree (β = 0.04), but social support is not significantly linked to changes in depression, lending no support to the idea that the effect of service attendance is mediated by social support (hypothesis 2b).

Table 1 tests for moderating effects by adding interactions between traumas with religious service attendance (model 1) and trait resilience (model 2) to the change in depression model depicted in Fig. 2 to determine whether these variables diminish the effects of traumatic experiences on depression (hypotheses 2b and 2c). Note that we do not test the interaction between religious psychosocial resources and traumas (hypothesis 2a) as the previous analyses indicate that any effect of these resources likely flows through trait resilience (see Fig. 2). Results in Table 1 lend no support to either hypothesis 2b or 2c. While both interactions are in the anticipated direction—with more attendance and trait resilience decreasing the negative effects of trauma—neither interaction is statistically significant, suggesting that if attendance and trait resilience play a role in moderating the effects of trauma, their influence is too inconsistent to form a detectable pattern.

Table 2 presents results from multinomial logit analyses designed to examine the role played by religious service attendance, religious psychosocial resources, and trait resilience in the reintegration process for older adults who have experienced at least one trauma between waves (N = 1710). We use religious service attendance at wave 2 to better capture the level of religious participation post-trauma, when any material and social supports offered by religious communities are most likely to be in operation. It is possible that traumatic events encourage older adults to become more religiously active, potentially creating a positive relationship between service attendance at wave 2 and distress. However, sensitivity analyses predicting attendance at wave 2 (not shown) provide no support for this idea in the present sample.

Contrary to expectations, Table 2 shows that religious psychosocial resources are negatively related to both a return to homeostasis (β = −0.25) and resilient reintegration (β = −0.13), though the latter estimate is not significant. However, this is the estimate controlling for trait resilience, which has a strong positive effect on both outcomes (β = 0.34 for return to homeostasis, β = 0.45 for resilient reintegration), consistent with hypothesis 4c. This suggests that the negative estimate for psychosocial resources might indicate that these beliefs can have undesirable effects for those low in trait resilience, possibly because traumatic experiences challenge their religious worldviews, such as the belief that God is watching out for them. However, on average religious psychological resources are positively related to trait resilience (β = 0.11, model not shown), indicating that they have an indirect positive effect on reintegration through trait resilience (hypothesis 5a). Thus, we have mixed support for hypothesis 4a, as religious psychosocial resources seem to have both positive and negative relationships with the positive outcomes of the reintegration process. In contrast, hypothesis 4b is strongly supported, with religious service attendance positively associated with both a return to homeostasis (β = 0.19) and resilient reintegration (β = 0.27), though this effect does not appear to be mediated by social support, which does not significantly predict either form of reintegration (hypothesis 5b).

To give a more meaningful interpretation of these findings, we present results using averages of predicted probabilities calculated at 1 SD above and below the mean level of religious service attendance and trait resilience, but that otherwise hold all variables at their sample values. Figure 3 shows that among older adults who experienced at least one trauma between survey waves, religious service attendance at wave 2 reduces the predicted probability of dysfunctional reintegration/reintegration with loss by 0.09 and increases the probability of a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration (vs. dysfunctional reintegration/reintegration with loss by about 0.04). Figure 4 reveals that results for trait resilience are similar but more pronounced. Here moving from 1 SD below to 1 SD above the mean level of trait resilience predicts a 0.16 decrease in the probability of experiencing dysfunctional reintegration/reintegration with loss. This benefit is about evenly split between a return to homeostasis and resilient reintegration, with those 1 SD above the mean having predicted probabilities that are 0.09 and 0.07 than those 1 SD below the mean, respectively. These predictions suggest that religious service attendance and trait resilience are valuable resources for promoting recovery after trauma.

Predicted probabilities of dysfunctional reintegration or reintegration with loss, return to homeostasis, and resilient reintegration by level of religious service attendance. Note Error bars calculated using the method outlined by Goldstein and Healy (1995) such that non-overlap indicates a statistically significant difference at the 0.05 level

Predicted probabilities of dysfunctional reintegration or reintegration with loss, return to homeostasis, and resilient reintegration by level of trait resilience. Note Error bars calculated using the method outlined by Goldstein and Healy (1995) such that non-overlap indicates a statistically significant difference at the 0.05 level

Discussion

In the current study, we used two waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to examine impact of religious psychosocial resources and religious service attendance on changes in depression between survey waves and reintegration following trauma. We found that both had beneficial outcomes, but they operated in different ways. Religious psychosocial resources had no direct effect on changes in depression and a negative directed effect on adaptive forms of reintegration, but in both cases exhibited beneficial indirect effects through trait resilience, which strongly predicted reductions in depression between survey wave and a higher probability of a return to homeostasis or resilient reintegration following trauma. Religious service attendance effects were mainly direct, with attendance predicting a small reduction in depression and an increased probability of both forms of adaptive reintegration. Service attendance also strongly predicted psychosocial resources, suggesting that one way that attendance facilitates positive mental health is by helping individuals to develop religious beliefs that support the adaptive ways of thinking that lead to trait resilience. Neither psychosocial resources (via trait resilience) nor attendance moderated the negative effect of traumas on changes in depression. Taken together, these results indicate that neither religious psychosocial resources nor service attendance diminishes the negative impact of traumatic events, but both can aid in recovering from them.

Our results are consistent with Richardson’s resiliency model, suggesting that religion can serve as a resource in the reintegration process (Richardson 2002), both directly and indirectly by promoting trait resilience. The indirect effects of religious psychosocial resources via trait resilience are consistent with past research showing that religion promotes adaptive worldviews and coping strategies that can improve mental health (Carrico et al. 2006, Pargament and Park 1995, Faigin and Pargament 2011). It is not clear exactly how to interpret the direct effects of religious service attendance, in large part because it is not clear which aspects of religion our measure of attendance captures—service attendance could be a marker for religious devotion, but might also measure exposure to the social and material support structures afforded by participation in a religious congregation. Past work suggests that religious devotion promotes positive coping (Horning et al. 2011; Pargament 2003), which is a component of the “hardy” mindset that characterizes trait resilience. However, our models controlled for both trait resilience and religious psychosocial resources, suggesting that the attendance effect is not likely due to devotion. Analyses support the claim that the attendance measure captures social support (from friends), but social support did not mediate the attendance effects. Given this, we cannot say for certain why religious service attendance has a positive relationship to mental health and adaptive reintegration, but we hypothesize that it may be due to forms of social and material support not accounted for by the social support measure we used. This is consistent with several studies that suggest that support received from congregations and family/friends is distinct (Chatters et al. 2014; George et al. 2002), but further research to confirm this supposition is warranted.

Our results also provide a crucial test of Richardson’s model in a population of older adults whose position in the life course puts them at high risk of experiencing traumatic events. Given the nature of aging and potential for decline, it is easy to imagine that older adults may not be able to fully or resiliently reintegrate as outlined in Richardson’s model, thereby limiting its applicability. In other words, older adults may have lower levels of reserve capacity (Staudinger et al. 1993), which would not impede them from returning to a state of resilient homeostasis but may prevent from resiliently integrating. However, our analyses provide no evidence for this idea. Instead, they indicate that older adults can (and do) fully recover from traumatic events and that some even emerge with less depression than before.

Our research is not without limitations. First, although we were able to establish that religious psychosocial resources and religious service attendance impacted depression between survey waves and resilient reintegration following trauma, we were unable to distinguish between the varying nature of traumas that occurred closer to wave 1 compared to those occurring closer to wave 2. It is plausible that the impacts of religious support and trait resilience have differing effects depending on the timing of the trauma. Future work should explore how older adults utilize religious psychosocial resources and religious service attendance to manage varying types and degrees of trauma, the amount of time that is spent managing implications of the trauma, and the impact this has on resilience and the process of resilient integration. Second, the current study is unable to determine exactly how trait resilience mitigates depression and response to trauma in terms of resilient homeostasis or integration. Determining a casual relationship is difficult due to the nature of our analysis. Despite these limitations, this study has important theoretical and practical implications and suggests a number of intriguing avenues for future research.

First, although our analyses found no support for the idea that religion moderates the effects of recent trauma, it is possible that religious involvement in particular religious traditions reduces the probability of experiencing some types of trauma, both over the life course and in later years. Following the teachings of a pacifist religion, for instance, would reduce the probability of exposure to war when young, and adherence to religious health codes could protect against drug addictions and serious illness throughout life. Second, we only examined the resilience process as it relates to depression—future work should explore how religion might influence reintegration with regard to other constructs such as sense of peace, hope, and/or mental functioning. Third, more attention could profitably be directed to unearthing how religion shapes trait resilience. What types of activities do religious groups engage in that promote beneficial worldviews and coping strategies? Does reaping these benefits require participating in religious congregations, or can personal religious devotion (or even non-religious spiritual practices) confer the same benefits? Fourth, researchers might ask how the effects of religious service attendance vary across individuals and religious groups. For instance, we might expect that the ability of religion to foster psychosocial resources will weaken as religious doubt increases, but the social and material benefits of participation in a religious congregation will not. Religious groups might also vary in their ability to provide emotional and material social support, and some groups might provide negative support that diminishes well-being (e.g., Dew et al. 2008). Finally, given the evidence here and in prior research that religion can benefit older adults, we might ask how we can support religious and spiritual connections in the lives of older adults? The linkages between religion and resilience and the roles they play in the lives of older adults are ripe for exploration and further investigation.

This study examined the role religion plays in resilience outcomes for older adults who have dealt with recent hardship, adversity, and trauma. We conclude that religion can help older adults to recover from trauma by fostering adaptive approaches to life’s challenges and possibly by providing congregationally based forms of social and material. Religion therefore enhances our understanding of resilience regardless of whether it is conceptualized as a trait, an outcome, or a process.

Notes

The alpha value is 0.92 for respondents who received the LBQ in 2006 and 2008, giving an overall wave one alphas value of 0.92. For simplicity, this alpha is calculated using listwise deletion (use about 91% of respondents).

Alpha values were 0.78 for responses in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012, giving overall alphas of 0.78 for measures at both wave 1 and wave 2.

The SRS and depression measures are related, but distinct.

References

Ardelt, M., Ai, A. L., & Eichenberger, S. E. (2008). In search for meaning: The differential role of religion for the middle-aged and older persons diagnosed with a life threatening illness. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20(4), 288–312.

Arrington, E. G., & Wilson, M. N. (2000). A re-examination of risk and resilience during adolescence: Incorporating culture and diversity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9(2), 221–230.

Bachay, J. B., & Cingel, P. A. (1999). Restructuring resilience: Emerging voices. Affilia, 14(2), 162–175.

Berger, P. L. (1967). The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory of religion. New York: Anchor Books.

Brewer-Smyth, K., & Koenig, H. G. (2014). Could spirituality and religion promote stress resilience in survivors of childhood trauma? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(4), 251–256.

Broyles, L.C. (2005). Resilience: Its relation-ships to forgiveness in older adults. Un-published doctoral dissertation, Uni-versity of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Carrico, A. W., Ironson, G., Antoni, M. H., Lechner, S. C., Durán, R. E., Kumar, M., et al. (2006). A path model of the effects of spirituality on depressive symptoms and 24-h urinary-free cortisol in HIV-positive persons. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61, 51–58.

Chatters, L., Taylor, R., Woodward, A., & Nicklett, E. (2014). Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(6), 559–567.

Clark, P., Burbank, P., Greene, G., Owens, N., & Riebe, D. (2010). What do we know about resilience in older adults? An exploration of some facts, factors, and facets (51–66). In B. Resnick, L. Gwyther, & K. Roberto (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research. New York: Springer.

Dew, R., Daniel, S., Goldstone, D., & Koenig, H. (2008). Religion, spirituality, and depression in adolescent psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(3), 247–251.

Ellison, C. G., & George, L. K. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 46–61.

Ellison, C., & Levin, J. (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 25(6), 700–720. doi:10.1177/109019819802500603.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Faigin, C., & Pargament, K. (2011). Strengthened by Spirit: Religion, spirituality, and resilience through adulthood and aging (163–180). In B. Resnick, L. Gwyther, & K. Roberto (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research. New York: Springer.

Ferraro, K. F., & Albrecht-Jensen, C. M. (1991). Does religion influence adult health? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30(2), 193–202.

George, L. K., Ellison, C. G., & Larson, D. B. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 190–200.

Global Restrictions on Religion. (2009). Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, December 2009. http://pewforum.org/Government/Global-Restrictions-on-Religion.aspx.

Goldstein, H., & Healy, M. J. R. (1995). The graphical presentation of a collection of means. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A, 158, 175–177.

Greene, R. R. (Ed.). (2002). Resiliency: An integrated approach to practice, policy, and research. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers Press.

Helgeson, V., & Lopez, L. (2010). Social support and growth following adversity (309–332). In J. W. Reich, A. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Hildon, Z., Montgomery, S. M., Blane, D., Wiggins, R. D., Netuveli, G., & Hälsoakademin & Örebro universitet. (2010). Examining resilience of quality of life in the face of health- related and psychosocial adversity at older ages: What is “right” about the way we age? The Gerontologist, 50(1), 36–47. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp067.

Hildon, Z., Smith, G., Netuveli, G., & Blane, D. (2008). Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30, 1–15.

Hill, T. (2010). A biopsychosocial model of religious involvement. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 30, 179.

Horning, S. M., Davis, H. P., Stirrat, M., & Cornwell, R. E. (2011). Atheistic, agnostic, and religious older adults on well-being and coping behaviors. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(2), 177–188. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2010.08.022.

Hovey, J., Hurtado, G., Morales, L., & Seligman, L. (2014). Religion-based emotional social support mediates the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and mental health”. Archives of suicide research, 18(4), 376–391.

Hughes, J. (2010). Health in a new key: Fostering resilience through philanthropy (496–515). In J. W. Reich, A. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Hummer, R. A., Rogers, R. G., Nam, C. B., & Ellison, C. G. (1999). Religious involvement and US adult mortality. Demography, 36(2), 273–285.

Humphreys, J. (2003). Research in shel-tered battered women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24, 137–152.

Idler, E. (1995). Religion, health, and nonphysical senses of self. Social Forces, 74(2), 683–704.

Koenig, H. G. (2002). An 83 year-old woman with chronic illness and strong religion beliefs. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(4), 487–493. doi:10.1001/jama.288.20.2541.

Koenig, H. G., George, L. K., Meador, K. G., Blazer, D. G., & Ford, S. M. (1994). Religious practices and alcoholism in a southern adult population. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 45, 225–231.

Koenig, H., Hays, J., George, L., Blazer, D., & Larson, D. (1997). Modeling the cross-sectional relationships between religion, physical health, social support, and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5, 131–144.

Koenig, H., Hays, J., Larson, D., George, L., Cohen, H., McCullough, M., et al. (1999). Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3968 older adults. Journals of Gerontology: A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 54, M370–M376.

Lavretsky, H. (2014). Resilience and aging research and practice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lavretsky, H., & Irwin, M. (2007). Resilience and aging. Aging and Health, 3(3), 309–323. doi:10.2217/1745509X.3.3.309.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 739–795). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562.

Mancini, A., & Bonanno, G. (2010). Resilience to potential trauma: Toward a lifespan approach (258–282). In J. W. Reich, A. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Manning, L. K., Carr, D. C., & Kail, B. L. (2016). Do higher levels of resilience buffer the deleterious impact of chronic illness on disability in later life? The Gerontologist, 56(3), 514–524.

Moskowitz, J. (2010). Positive affect at the onset of chronic illness (465–483). In J. W. Reich, A. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Nygren, B., Aléx, L., Jonsén, E., Gus-tafson, Y., Norberg, A., & Lundman, B. (2005). Resilience, sense of coher-ence, purpose in life and self-transcen-dence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging & Mental Health, 9, 354–362.

Pargament, K. I. (2003). God help me: Advances in the psychology of religion and coping. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 24(1), 48–63. doi:10.1163/157361203X00219.

Pargament, K. T., & Cummings, J. (2010). Anchored by faith: Religion as a resilience factor. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 193–210). New York: Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I., & Park, C. L. (1995). Merely a defense? The variety of religious means and ends. Journal of Social Issues, 512, 13–32.

Park, C., & Cohen, L. H. (1993). Religious and nonreligious coping with the death of a friend. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17, 561–577.

Reich, J. W., Zautra, A., & Hall, J. S. (2010). Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Resnick, B., Gwyther, L., & Roberto, K. (Eds.). (2011). Resilience in Aging: Concepts, research. New York: Springer.

Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321.

Rote, S., Hill, T. D., & Ellison, C. G. (2013). Religious attendance and loneliness in later life. The Gerontologist, 53(1), 39–50.

Schieman, S. (2008). The education-contingent association between religiosity and health: the differential effects of self-esteem and the sense of mastery. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47, 710–724. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00436.x.

Seery, M. D. (2011). Resilience: A silver lining to experiencing adverse life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(6), 390–394. doi:10.1177/0963721411424740.

Staudinger, U. M., Marsiske, M., & Baltes, P. B. (1993). Resilience and levels of reserve capacity in later adulthood: Perspectives from life-span theory. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 541–566. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006155.

Wagnild, G. (2009). A review of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 17(2), 105–113.

Wagnild, G. M., & Collins, J. A. (2009). Assessing resilience. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 47(12), 28–33. doi:10.3928/02793695-20091103-01.

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evalu-ation of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165–178.

Zeng, Y., & Shen, K. (2010). Resilience significantly contributes to exceptional longevity. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2010, 525693–525699. doi:10.1155/2010/525693.

Zraly, M., & Nyirazinyoye, L. (2010). Don’t let the suffering make you fade away: An ethnographic study of resilience among survivors of genocide-rape in southern Rwanda. Social Science and Medicine, 70(10), 1656–1664.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Linda George for her thoughtful feedback on a previous draft of this article.

Funding

The author, Dr. Lydia Manning, disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article by NIH Grant 5T32 AG00029-35 (LM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manning, L.K., Miles, A. Examining the Effects of Religious Attendance on Resilience for Older Adults. J Relig Health 57, 191–208 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0438-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0438-5