Abstract

Understanding how feedback is employed in various forms, positions, and contexts can provide valuable insights into improving communication and the design of human–machine dialogue systems. This paper aims to deepen the understanding of feedback in daily conversation and investigate how feedback is employed in various linguistic forms, position, preceding and following contexts, using a large corpus of telephone conversations. The study identifies three subclasses of feedback, including understandings, agreements, and answers, which account for almost one-third of the total utterances in the corpus. Acknowledge (backchannel) is the most frequently used subtype of feedback, accounting for almost 60% of the feedback, and is primarily used for conversational management and maintenance. Assessment/appreciation, on the other hand, is used less frequently, accounting for less than 10% of feedback, and is mainly realized by more creative, unpredictable, longer forms. The analysis also reveals that speakers are intentional in distinguishing the three subclasses of feedback based on various variables, such as position and the proximal discourse environment. Furthermore, the three subclasses of feedback are restricted by the function of preceding contexts, which shape the length of the remaining turn. The study suggests that future research should focus on exploring the individual differences and investigating the possible variations across different cultures and languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Generally speaking, daily communication minimally involves speakers and listeners (Xu, 2014). While most of previous research has primarily concentrated on the role of speakers (Gardner, 2001; Goodwin, 1986; McCarthy, 2003), it has been widely accepted that listeners play an equally important role in interaction to keep the smooth progress of conversation. Linguistic production of listeners has received increasing research interest with different terms, such as acknowledgement tokens (Jefferson, 1984), backchannel behavior (Yngve, 1970), feedback (Allwood, 1992) listener responses (Dittmann & Llewellyn, 1968), non-minimal response (McCarthy, 2003), reactive tokens (Clancy et al., 1996), etc., which sights a limited methodological outlook to the occurrence learned (Heinz, 2003). In this study, the term feedback is used to label various kinds of linguistic production of listeners in a broad sense, encompassing all reactive phenomena.

However, actually there is little agreement in the literature as to what constitutes these terms and what is included varies from study to study (Kjellmer, 2009; Wong & Peter, 2007). “[I]t is therefore hardly possible to give a finite list” (Kjellmer, 2009: 83). Comprehensive inventory is proposed by fewer authors, or they debate with marginal members of the category (Wong & Peter, 2007). Quite a large number of previous studies make qualitative analysis and report the findings of prototypical forms, to show their distinctive but complex meaning they provided under specific circumstances (Gardner, 1997, 2001). A description of the inventory can be informally classified into three groups based on the language forms described in the literature: minimal (e.g. uhuh, mhm and oh), lexical (e.g. really and right) and grammatical construction (e.g. I see, that’s true, utterance completions and repetitions). A few corpus-based studies use operational criteria to capture one category of cases, often those minimal ones, to reveal one particular respect of feedback in communication, including the specific insertion point of “backchannel” (Kjellmer, 2009), the characteristics of linguistic expressions ranging from single, duplicate to the compound (Wong & Peter, 2007) used in different English varieties. These studies indicate that there is a lack of a full picture of how feedback is used in daily conversation by native speakers, even though there is a considerable large number of previous studies in the literature. The researcher takes a more holistic overview of the area, which does not just focus on a small group of cases. As Wong and Peter state (2007), the return to real things were needed for the basics of identity and details if role listeners had a hand in the conversations and their contribution needed to be developed specifically.

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, a human–machine dialogue system needs to be able to understand and produce feedback as human beings in order to achieve better interactive experience (Axelsson et al., 2022). Previous studies in computer science tend to draw on various models and features for automatic detection and recognition of particular communicative functions. However, these models and features are unexplainable in that they cannot explain the reason for the improvement and how much contribution each feature makes. Although a wide range of deep learning methods including RNN, reinforcement learning and GAN have been introduced to strengthen language style and capture context information, the lack of linguistic knowledge is an unavoidable bottleneck restricting the current human–machine interactive experience. Mining linguistic characteristics of feedback from the corpus and transforming that into dialogue knowledge is the key to further improve man–machine interactive experience.

Therefore, this paper aims to depict a full picture of feedback in daily life and to show how feedback is commonly employed by native speakers. A systematic account of feedback in everyday communication would be of practical significance in that it has crucial applications in Natural Language Processing, in particular for informing machines how to perform feedback when communicating with humans. This investigation uses data from the Switchboard Dialogue Act (SwDA) Corpus, a native English spoken corpus of telephone conversations, to explore formal properties of feedback including linguistic forms, position and the proximal environment of feedback. This study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1

What kinds of linguistic forms are used to realize feedback?

RQ2

Where does feedback occur in a turn?

RQ3

What is the proximal discourse environment of feedback; that is, what immediately precedes and follows feedback in daily life?

The most significant part that must be considered while analyzing formal characteristics of response is on the details on which experimentation is based upon. Telephone conversation is an ideal option in the study of feedback in that it provides a potentially rich source of data for the study of feedback due to participants’ lack of access to nonverbal cues (Heinz, 2003). Considering normal forms of response like interacting face to face, non verbal forms include gaze, signal and touch serving the same functionality, but interfere with the use of verbal forms, particularly in feedback (Wong & Peters, 2007). Thus, telephone conversations are more appropriate for feedback research.

Contribution of Research

This study identifies three subclasses of feedback and their subtypes in conversational interactions, analyzes their positioning and discourse environment, and explores their use in conversational management and maintenance. The findings highlight the importance of individual differences and the potential benefit to Natural Language Processing, while emphasizing the need for further empirical research.

-

Identification of the three subclasses of feedback (i.e., understandings, agreements, and answers), which include 26 subtypes that account for almost one third of the total utterances in the corpus.

-

Analysis of the positioning and proximal discourse environment of feedback utterances, which revealed that understandings are more likely to stand alone and elicit the interlocutor's utterances, while agreements and answers prefer turn-initial position and provide more information.

-

Exploration of the use of subtypes associated with conversational management and maintenance, such as acknowledge (backchennel), which accounted for almost 60% of feedback, by means of simple, repetitive, short forms, and the limited use of assessment/appreciation, which accounted for less than 10% in daily conversations, and was mainly realized by more creative, unpredictable, longer forms.

This article is organized as follows: section “Corpus Resources” outlines corpus resources and basic statistical information of feedback in this study, while Sections “Linguistic Forms”–“Contexts” respectively reports the features of feedback in linguistic forms, position and specific contexts. Section “Conclusion” summarizes the main points and sketches out avenues for future research.

Corpus Resources

Switchboard Dialogue Act Corpus (SwDA)

The current study uses a corpus to human-to-human telephonic discussion as Switchboard Dialogue Act (SwDA) Corpus. It contains 1155 conversations comprising 223,606 utterances (Fang et al., 2011). The transcription of the above dialogue is being used in an extensive manner to depict the accuracy and distinctive quality of speaking language. About one aspect, a movement is divided into a series of words known as the “slash-unit”. (Meteer & Taylor, 1995); The notation of words is as non-sentence components such as discourse marker ({D…}), coordinating conjunction ({C…}), and filler ({F…}). Additionally, all utterances have been individually labeled with dialogue acts using the SWBD-DAMSL coding system (Jurafsky et al., 1997). Refer Table 1.

The “b”, “+” and “sd” at the commencement of each speech indicate the communicative function the utterance performs; “sd” and “b” refer to statement-non-opinion and acknowledge (backchannel) respectively. The tag “+” in Line 3 is a special DA label; it signals that the current utterance is a continuation of the previous utterance by the same speaker and has the same function statement-non-opinion in Line 1. The two separate speakers are denoted by the two alphabets “A” and “B”. While “utt#” denotes the utterance's ordinal number inside each turn and the number immediately following A and B (“13”, “14”, “15”) denotes the turn's ordinal number. The character slash “/” at the conclusion of the speech signifies that the utterance is complete. In real-time speaking, “[+]” indicates restarts and fixes.

Backwards-Communicative-Function Versus Feedback

SWBD-DAMSL’s backwards-communicative-function is developed in tandem with backward looking functions in DAMSL scheme indicating “how the current utterance relates to the previous discourse” (Allen & Core, 1997: 17). It breaks it roughly down into Understandings, Agreements and Answers, involving various types of relations to previous contexts, all of which are encompassed into the term feedback for simplicity in the current study. For one thing, feedback essentially refers to various backwards-communicative-function including all reactive phenomena in communication; for another, feedback is more transparent in terms of terminology.

Distribution of Feedback in SwDA Corpus

The corpus data showed that 69,402 of 223,606 utterances, or 31.04% of the utterances, served feedback. In other words, almost one third of utterances in daily communication were used to provide feedback for the interlocutor. Moreover, feedback in the corpus data was perceived to be realized by a wide range of subtypes. Table 2 below exhibits that feedback incorporated three main categories: understandings, agreements and answers, indicating different aspects of feedback in daily communication; understandings, the largest category, account for 70% of feedback, followed by agreements (18%) and answers (12%) respectively. According to the definition in the coding scheme, understandings include markers of understanding at various level “including what Yngve (1970) called ‘backchannels’”, as well as “markers of misunderstanding like requests for repeat and corrections of misspeaking (‘next-turn-repair-initiators’), and others” (Jurafsky et al., 1997: 41). The agreement category marks a different degree to which “speaker accepts some previous proposal, plan, opinion, or statement” (Jurafsky et al., 1997: 37) and answer refers to various types of answers to the preceding question. The three categories were further divided into 26 subtypes, which were not evenly distributed. The most frequent subtype was acknowledge (backchannel), comprising 55.45% of feedback utterances, which is followed by accept (16.24%) and assessment/appreciation (6.86%). Refer Table 2.

It should be noted that in the following subtypes occurring less than 100 times are not taken into account due to a low frequency, including sympathy, correct-misspeaking, accept-part, maybe, reject-part, no-plus-expansion and yes-plus-expansion (italics in Table 2). This investigation concentrated on those subtypes with more than 100 occurrences, a total of 19 subtypes.

Linguistic Forms

Linguistic expressions are a kind of forms, considered as strong cues to the identity (Jurafsky et al., 1998). Li (2022) makes corpus-based analysis of three types of feedback in terms of linguistic expressions (i.e. acknowledge (backchannel), accept and assessment/appreciation). Results show that the speakers in daily life tend to produce simple forms of acknowledgement (backchannel) but more complex forms of assessment/appreciation. Accept is located between the two. This continuum among the three subtypes can be further confirmed by the data shown in Table 3, where additional information about the distribution of the three subtypes by the length of utterances is provided. Refer Table 3.

The corpus' three subgroups were all rather small in length. As shown in Table 3, the average number of words is fewer than four, 3.06 in assessment/appreciation, 1.90 in accept and 1.07 in backchannel/acknowledgement, consisting of standard deviation of 0.31 wordings in acknowledge (backchannel), 1.85 in accept and 1.72 in assessment/appreciation. Thus, they can be placed on a continuum in terms of length where acknowledge (backchannel) is the shortest, followed by accept, and assessment/appreciation is the longest of the three.

Wong & Peter (2007) posited that the complexity of structures was believed to be “correlated with their interactional function”. To help the principal performer continue the turn, the basic forms with no grammatical or lexical contents appeared. The increase in syntactic complexity suggested to talk about the content itself and shift the support away from the speaker (Wong & Peter, 2007). The corpus evidence confirmed this assumption by the fact that acknowledgement (backchannel) primarily severed conversational management and maintenance of conversational discourse by a limited number of short, simple and repeated forms, while assessment/appreciation was associated with information content by a large number of longer, complicated and unpredictable forms. The prevalence of acknowledgement (backchannel) indicates the importance of conversational management and maintenance to the success of conversation.

Positional Analysis

Position refers to where an utterance is located within a turn. The position of feedback utterances was analyzed based on their occurrence in four positions: standing alone, turn-initial, turn-medial, and turn-final. The frequencies and percentages of feedback utterances in each position were calculated, and differences between subtypes were also examined. The data analysis for this study involved identifying and categorizing different types of understandings, agreements, and answers used by the participants during the conversation. Then, the positions of these different types of utterances were analyzed to determine any patterns or tendencies. The researcher identified feedback utterances in the corpus and noted their position in the turn. Finally, the frequencies and percentages of each subtype in different positions were calculated, and the results were analyzed to identify patterns and tendencies.

The analysis revealed that various understandings were mainly used to acknowledge the other’s words and were often located in a free-standing position. Agreements and answers, on the other hand, were used to provide more information for the interlocutor and were typically located at the beginning of a turn. Repeat-phrase was one type of understanding but more likely to hold a turn-initial position. Hold-before-answer/agreement (^h) had a greater chance to occur in the middle and was often used to hold before an answer or agreement by expressions such as let me think. Statement-expanding-y/n-answer (s^e) was more likely located in the middle and at the end of a turn. Other-answers tended to stand as a turn alone and were used when it was difficult to categorize the response.

The current study made a division of position into standing alone, turn-initial, turn-medial and turn-final positions. Take the following case as an example, where the assessment/appreciation (ba, ba^r) occurred in “utt1” and “utt2” within the same turn (“53”), recorded as turn-initial and turn-final positions, respectively. Refer Table 4.

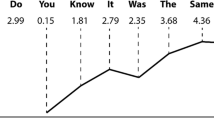

In the corpus data, feedback could be used in free-standing, initial, medial and final positions but was unevenly distributed: 37,067 feedback utterances were captured to stand alone as an independent turn, comprising 54.1% (37,067/68,500) of the total amount of feedback, while 29.9% (20,494/68,500) occurred at the very beginning of a turn, 7.5% (5,144/68,500) in the middle, and 8.5% (5,795/68,500) at the end. These indicate that, overall, feedback utterances had a greater tendency to stand alone as an independent turn; in contrast they were less likely to occur in the middle or final position. Figure 1 depicts position information for each subtype. Figure 1 is displayed below along with the percentages and subtypes.

Clearly, different subtypes showed their own preference to different positions: understandings overwhelmingly occurred in free-standing positions while agreements and answers appeared to be more complicated. Understandings were a subclass which were primarily used to indicate speakers’ understanding at various levels, after which producers immediately released the turn and handed the floor to the partner. By contrast, most agreements and answers were more likely to occur at the beginning of a turn with other utterances following; to keep the conversation continuing, producers typically kept the floor and added more information to agreements and answers. Refer Table 5.

In this excerpt, the bolded lines performed yes-answer (ny), acknowledge (backchannel) (b) and backchannel-in-question-form (bh), respectively. In Line 2, B briefly answered the previous question by a yes-answer uh yeah and supplied additional information about the community in Lines 3–5 to extend the talk. Differently, A immediately released the turn after the two utterances uh-huh (Line 7) and oh really (Line 9) and returned the floor to the partner B. Therefore, it can be observed that understandings, agreements and answers showed variation in position, which was probably associated with different functions they served. Various understandings were mainly used to elect the other’s words since they showed the tendency to free-standing position and put obligation to the interlocutor. By contrast, agreements and answers were used to provide more information for the interlocutor, since in most cases producers kept the turn and supplied additional information.

In addition, exceptions could be perceived at repeat-phrase (b^m), hold-before-answer/agreement (^h), statement-expanding-y/n-answer (s^e) and other-answers (no). Repeat-phrase was one type of understanding but more likely to hold turn-initial position; after repetition, the speaker tended to propose a further question or provide more information; in this vein, it was easier for the interlocutor to continue the talk and keep the smooth progress of conversation. Hold-before-answer/agreement (^h) indicated one level of agreement but had a greater chance to occur in the middle; it was often used to hold before an answer or agreement by expressions such as let me think; it was inserted into the middle of a turn to indicate the producer’s uncertainty. It is not surprising that statement-expanding-y/n-answer (s^e) was more likely located in the middle and at the end of a turn since it is defined as a type of answer to expand or explain a simple yes or no answer. Other-answers showed distinction in that it tended to stand as a turn alone; it was something of a junk and answers were placed in this category because they were not easy to fall into any other types of answers above.

Contexts

Preceding Contexts

Feedback is characterized as responses to what has been expressed in the preceding; so, it is strongly constrained by the preceding context. An examination of preceding contexts thus is crucial to fully reflect its characteristics and the environment where it occurs. Here, the preceding context refers to the immediate previous turn produced by the partner, including two respects of information, i.e. length and the communicative functions performed. Refer Table 6.

The feedback acknowledged (backchannel) lies in Line 4, and the preceding context refers to the immediate previous turn that spans from Line 1 to 3. Accordingly, the length is recorded as “PL3”; the functions performed by them are statement-non-opinion (“sd”), continuously occurring three times. In total, 31,210 feedback utterances were captured to have one utterance in the immediately preceding turn (PL1), accounting for 45.6% (31,210/68,500) of the total amount of feedback. In the following, the length of preceding turns will be specified for each subtype.

Length of Preceding Contexts

Figure 2 below shows the distribution of the prior turn with varied lengths across different subtypes: the vertical axis shows the proportion that the prior turn of distinctive lengths account for, whereas the horizontal axis refers to different subtypes.

Overall, different subtypes of feedback showed similarities in length of preceding turns; all subtypes gave priority to PL1 (40–65% across different subtypes); as the length increased there was a great decrease in the rate (20–30% in PL2, 5–15% in PL3). This suggests that preceding contexts were simple in terms of length; usually the participant provided a feedback utterance at once when the partner uttered one or two utterances. It was not very common to see that a large number of utterances preceded various feedback utterances.

Communicative Functions of Preceding Contexts

It is a point of interest to specify to which different types of feedback were oriented in the preceding turn. The corpus data showed that different subtypes of feedback shared 14 functions in the preceding turn, which constituted over 60% of preceding contexts in each. Figure 3 below presents the distribution of the 14 shared functions that preceded different subtypes. The horizontal axis shows different subtypes of feedback, whereas the vertical axis shows the proportion that the shared functions accounted for when preceding different subtypes.

It shows that the shared functions made different contributions when preceding different subclasses. In particular, statement-non-opinion (sd), yes–no-question (qy) and statement-opinion (sv) showed dramatic distinction when preceding different subtypes of feedback, which made their curve lines go up and down in the figure above. First, statement-non-opinion was the most significant function preceding understandings, ranging from 30 to 70% of their preceding contexts, while it was not that significant when preceding agreements and answers. Second, yes–no-question was the most frequent function that preceded various answers, comprising 25–41% of their preceding contexts, while this percentage decreased to 10% when preceding understandings and agreements. Third, statement-opinion was extremely prominent when preceding agreements, especially accept (aa) and reject (ar).Footnote 1 This kind of preference has been widely referred to as adjacency pairs in the literature, which is believed to play a crucial role in organization of conversational turn sequence (Schegloff, 2007). The large-scale dialogue corpus adopted in the current study showed that participants in daily conversations collaboratively constructed turn sequences by producing types of adjacency pairs: statement-non-opinion and understandings, statement-opinion and agreements (except for ^h), yes–no-question and answers on the one hand, and on the other hand, it presented the statistical proportion that indicated the extent to which preceding contexts were required. The pair of statement-non-opinion and understandings appeared closer since statement-non-opinion made a dominant contribution when preceding understandings.

Thus, in general, preceding contexts of feedback showed more similarities in length but varied in the communicative functions they performed. It was the communicative functions in the preceding turn that restricted the choice of feedback, which led to the build-up of adjacency pairs of turn sequence. Below the researchers move on to the following contexts of feedback, to see how different subtypes of feedback differ from each other.

Following Contexts

Following context refers to utterances that immediately follow feedback. As Gardner (2004) points out, feedback provides information “to other participants in the talk not only about how some prior talk has been received, but also some information on how it is projecting further activities in the talk.” It is, therefore, crucial to see who or what is expressed after feedback. This following subsection explores whether the producer of feedback continues the talk and what is expressed after feedback by two respects, i.e., length and the communicative functions performed by them. Refer Table 7.

In the former example, the feedback in Line 2 was realized by affirmative-non-yes-answer (“na”), and no utterance was perceived to follow it in the same turn; the length of following contexts was recorded as FL0. Differently, yes-answer (“ny”) in Line 2 of the latter example was followed by one utterance (Line 3) in the same turn, the length of which thence was recorded as FL1; it served statement-expanding-y/n-answer (“sd^e”). In total, 62.6% (42,862/68,500) of feedback utterances were used to terminate the current turn, and the length of following contexts was recorded as “FL0”. In the following, before moving on to the communicative functions performed by following contexts, at the first we can look into the length of the reminder turn after feedback.

Length of Following Contexts

Figure 4 below presents the proportions that distinctive lengths of the reminder turn contributed to each subtype. The horizontal axis shows the different subtypes of feedback while the vertical axis denotes the proportions they account for. The figure below represents the percentage of understandings, agreements and answers.

It is obvious that understandings, agreements and answers varied in length in the following contexts. As the figures show, FL0 was dramatically prominent across various understandings, accounting for more than 50% in each subtype, but this percentage declined to 20–50% in agreements and answers where FL1 made the largest contribution. This is consistent with the finding in position (section “Positional Analysis”) and demonstrates a tendency that speakers in daily life more likely hand the floor back to the partner immediately after understanding, whereas they usually add one more utterance after agreements and answers.

Note that no-answer (“nn”) is more likely followed by one utterance than other types of answers. For illustration, consider Table 8 below: in Line 2, A answers B’s question by a simple no-answer (“nn”) and subsequently adds additional information to tell that they do not have snow before Christmas (Lines 3–4).

It seems that a simple no-answer does not satisfy participants’ demand and more information is expected for explanation, illustration and expansion, for the sake of the step-by-step build-up of joint understanding and common ground (Clark, 1996). This is the same as to reject (“ar”), which is more likely followed by an utterance than accept (“aa”). A simple no-answer or rejection is somewhat face-threatening and the additional information provided is to gain partners’ sympathy and understanding, to “avoid or minimize disagreements, disconfirmations and rejections if possible” (Pomerantz & Heritage, 2013: 215) for face consideration. This seems to be where preference comes into play. A response that is aligned with the bias of the prior turn is preferred whereas a response that misaligns with the prior turn is not preferred. A no-answer or reject is one type of dispreferred as “there are departures from some of these understandings, expectations and projections” (Heritage, 2015: 89); and this is usually produced with more delays and repair initiators (Pomerantz, 1984). The present study showed that dispreferred also could be marked by the way of the length of the turn, where extensive information was more likely provided for explanation and expansion. This invites future work to compare and contrast more types of preferred and dispreferred responses.

Communicative Functions of Following Contexts

It has been found that a few utterances may occur after feedback in the same turn, to perform certain communicative functions in interaction. Data showed that subtypes of feedback exhibited great similarities in following contexts; they shared four functions which, however, accounted for 55–95% across different subtypes. Figure 5 below shows the proportions that the four shared functions contribute in each subtype.

It can be seen that the four shared functions almost have the same distribution when following different subtypes of feedback. Statement-non-opinion (“sd”) is the most significant one in following contexts for most subtypes; in particular, it is more likely to follow agreements and answers with a relatively high proportion. By contrast, yes–no-question (“qy”) makes the least contribution, indicating that it is a commonly observed function after feedback but is not very frequent. Statement-opinion (“sv”) and uninterpretable (“%”) are the other two shared functions in following contexts which make almost the same contribution across different subtypes.

It is noted that uninterpretable (“%”) is the most significant function following completion (^2), not statement-non-opinion (“sd”). The symbol “%”is used to mark abandoned, indeterminate, interrupted utterances or turn exit (Jurafsky et al., 1997). It seemed to pattern one way in which the producer of completion would like to continue the talk but he was not ready for what to say; he employed the uninterpretable utterance as a transition to release the turn. Refer Table 9.

A and B were talking about family reunions in this excerpt. In Line 3, A completed B’s preceding utterance by “relatives”, and then produced a “right”, noted as uninterpretable (%). Here, the symbol “%” is used to mark short “turn-exits” facilitating the transition to the next turn; A put the obligation to the interlocutor to take the turn.

Another case that needs to be noted occurred to yes-answer (“ny”) and no-answer (“nn”) where the shared four functions added up to 55%, lower than that of others. Returning to the data, they found that statement-expanding-y/n-answer was an important function following yes-answer (“ny”) and no-answer (“nn”), accounting for 36.5% and 42.3% of the following contexts, respectively. In particular, no-answer was more likely followed by various kinds of statements (“sd” “sv” “s^e”) for explanation and illustration. As illustrated in the preceding, more additional information after no-answer was used to minimize discrepancies from understandings and expectations.

The observers could see that understandings, agreements and answers varied in length but showed similarities in communicative functions in following contexts. In most instances, after understanding, producers directly handed the turn back and put an obligation to the interlocutor to take the turn, while they tended to produce extensive information after agreements and answers to extend the talk. In particular, as one type of dispreferred responses, a simple no-answer and reject are more likely followed by various types of statement in the following than the counterpart.

Sections “Linguistic Forms”–“Contexts” had investigated formal properties of feedback (i.e., linguistic forms, position, preceding and following contexts) in daily conversation based on a large-scale telephone corpus. The author found that the three subclasses (i.e., understandings, agreements and answers) showed their own preference to the position: understandings tended to occur independently as a turn while agreements and answers tended to occur in turn-initial position with more utterances following. This seemed to lead to their different functions as feedback: understandings were primarily used to elicit the partner’s words while agreements and answers were mainly used to provide information. Understandings tended to stand alone and speakers declined the floor and put the obligation of speaking on their partners after them. Differently, agreements and answers tended to occur at the very beginning of the turn, with more utterances in sequence. Furthermore, the analysis showed that the simple no-answer and reject were more likely followed by utterances within the turn in progress. More information was supplied to further illustrate and explain, to build up more joint understanding and minimize face-threatening. Alternatively, more utterances following could be interpreted as another type of device denoting dispreferred responses.

The current study also shows that the ways in which successive utterances cohere into strongly patterned sequences of interaction can be realized by different respects. It is obvious that the three subclasses are primarily restricted by the communicative functions in the preceding turn, which leads to construction of adjacent pairs; in the meantime, they shape the following context but by the length of the remaining turn, which has not been reported yet in previous studies. More importantly, the proportion statistically specifies the degree of confinement by the environment where they occur. It is expected that such kind of formal features and statistical information on feedback in daily conversation could be applied to the human–machine system to improve the interactive experience.

Conclusion

This paper attempted to deepen the understanding of feedback in daily conversation and to depict a full picture of how feedback is employed by an investigation of all the linguistic forms, position, preceding and following contexts, based on a large corpus of telephone conversations. In this process, “language corpora are very useful, not to say indispensable” (Kjellmer, 2009: 82). Based on the corpus evidence, the researchers could see some general trends in feedback use as well as a few special cases, which are of great significance in the human–machine dialogue system.

The results showed that speakers in daily interaction drew on three subclasses of feedback (i.e., understandings, agreements and answers), which included 26 subtypes accounting for almost one third of the total utterances in the corpus. Moreover, to keep the smooth progress of the ongoing conversation, they frequently relied on subtypes associated with conversational management and maintenance, such as acknowledge (backchannel), which accounted for almost 60% of feedback, by means of simple, repetitive, short forms. By contrast, assessment/appreciation, primarily for conveying the information content, accounted for less than 10% in daily conversations, which were mainly realized by more creative, unpredictable, longer forms.

The analysis also found that speakers were intentional in distinguishing the three sub-classes: understandings, agreements and answers by using a set of variables, including position and the proximal discourse environment. Standing alone, understandings were more likely used to elicit the interlocutor’s utterances as speakers immediately shifted the turn and put the obligation of speaking on the interlocutor whereas agreements and answers, preferring to turn-initial position, were more likely to provide more information. This was even more so for reject and no-answer, which is believed to result from face consideration, to minimize or void disagreements. Moreover, the three subclasses—understandings, agreements and answers—were restricted by preceding contexts; they all were likely preceded by one-utterance turn which, however, served different functions; that is, statement-non-opinion, statement-opinion and yes–no-question respectively. At the same time, they shaped the length of the remaining turn.

One should bear in mind that it is not possible to decide from the data discussed whether the differences among various subtypes were representative of all cases. When it broke down the data for specific cases, the researchers found larger differences. For instance, uh-huh was more likely to be freestanding than yeah when both worked as acknowledge (backchannel). Thus, individual differences should be taken into account in the future work because it is believed to lead to more in-depth empirical research and potential benefit to Natural Language Processing. Many more insights can be expected from the corpus evidence.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Hold-before-answer/agreement (^h), as one level of agreement, is conflicting with this tendency in preceding contexts. Both statement-opinion and statement-non-opinion have a low point when preceding hold-before-answer/agreement (^h).

References

Allen, J. & Core, M. (1997). DAMSL: Dialogue act markup in several layers (Draft 2.1). Technical Report, Multiparty Discourse Group, Discourse Resource Initiative, September/October 1997.

Allwood, J., Nivre, J., & Ahlsén, E. (1992). On the semantics and pragmatics of linguistic feedback. Journal of Semantics, 1, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/9.1.1

Axelsson, A., Buschmeier, H., & Skantze, G. (2022). Modeling feedback in interaction with conversational agents—a review. Frontiers in Computer Science, 4, 744574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2022.744574

Clancy, P. M., Thompson, S. A., Suzuki, R., & Tao, H. (1996). The conversational use of reactive tokens in English, Japanese, and Mandarin. Journal of Pragmatics, 26(3), 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(95)00036-4

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.2277/0521561582

Dittmann, A. T., & Llewellyn, L. G. (1968). Relationship between vocalizations and head nods as listener responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2022.744574

Fang, A., Bunt, H., Cao, J., & Liu X. (2011). Relating the semantics of dialogue acts to linguistic properties: A machine learning perspective through lexical cues. In Proceedings 5th IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing, (pp. 490–497). Stanford University, Palo Alto. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSC.2011.32

Gardner, R. (2004). Acknowledging strong ties between utterances in talk: Connections through right as a response token. In Proceedings of the 2004 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society, pp. 1–12.

Gardner, R. (1997). The conversation object “Mm”: A weak and variable acknowledging token. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 30, 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3002_2

Gardner, R. (2001). When listeners talk: Response tokens and listener stance. John Benjamins Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.92

Gardner, R. (2007). The right connections: Acknowledging epistemic progression in talk. Language in Society, 36(03), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404507070169

Goodwin, C. (1986). Between and within: Alternative sequential treatments of continuers and assessments. Human Studies, 9, 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148127

Heinz, B. M. (2003). Backchannel responses as strategic responses in bilingual speakers’ conversations. Journal of Pragmatics, 35(7), 1113–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00190-X

Heritage, J. (2015). Well-prefaced turns in English conversation: A conversation analytic perspective. Journal of Pragmatics, 88, 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.08.008

Jefferson, G. (1973). A case of precision timing in ordinary conversation: Overlapped tag-positioned address terms in closing sequences. Semiotica, 9(1), 47–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1973.9.1.47

Jefferson, G. (1984). Notes on a systematic deployment of the acknowledgement tokens “yeah”and “mm hm.” Research on Language and Social Interaction, 17(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351818409389201

Jurafsky, D., Shriberg, E., & Biasca, D. (1997). Switchboard SWBD-DAMSL shallow-discourse-function annotation coders manual, Draft 13, University of Colorado, Boulder Institute of Cognitive Science Technical Report, pp. 97–02.

Jurafsky, D., Shriberg, E., Fox, B. & Curl, T., (1998). Lexical, Prosodic, and Syntactic Cues for Dialog Acts. In ACL/COLING-98 Workshop, pp. 114–120.

Kjellmer, G. (2009). Where do we backchannel? International Journal of Corpus Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.14.1.05kje

LI, Y. (2022). Three types of feedback and pedagogical implications [J]. Australian Chinese Magazine, 4, 152–159.

McCarthy, M. (2003). Talking back: “Small” interactional response tokens in everyday conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 36(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3601_3

Meteer, M. and Taylor, A. (1995). Dysfluency Annotation Stylebook for the Switchboard Corpus. Available at ftp://ftp.cis.upenn.edu/pub/treebank/swbd/doc/DFL-book.ps.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

Pomerantz, A., & Heritage, J. (2013). Preference. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 210–228). Wiley Blackwell.

Schegloff, E. A. (1982). Discourse as an interactional achievement: some use of “uh-huh” and other things that come between sentences. In D. Tannen (Ed.), Analyzing discourse: Text and talk (pp. 71–93). Georgetown University Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511791208

Wong, D., & Peters, P. (2007). A study of backchannels in regional varieties of English, using corpus mark-up as the means of identification. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 12(4), 479–509. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.12.4.03won

Xu, J. (2014). Displaying status of recipiency through reactive tokens in mandarin task-oriented interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 74, 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.08.008

Yngve, V. H. (1970). On getting a word in edgewise. In Papers from the sixth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society. Chicago Linguistics Society, Meeting.

Funding

This paper has been sponsored by National Social Science Fund of China “A Study of Chinese Dialogue Act Annotation and Automatic Detection” (20CYY021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y. A Corpus-Based Study on Feedback in Daily Conversation: Forms, Position and Contexts. J Psycholinguist Res 52, 2075–2092 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-023-09976-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-023-09976-x