Abstract

This study aimed at examining the impact of phonemes and lexical status on phonological manipulation among pre-school children. Specifically, we tested the impact of phonemic positions (initial vs. final) and lexical status (shared, spoken, standard and pseudo-words) on phonemic isolation performance. Participants were 1012 children from the second year (K2) and third year (K2) in kindergarten. The results of the ANOVAs revealed significant effect of the phonemes’ position on the phonemic isolation performance whereas the performance was easier with the initial rather than the final phonemes. Also, the repeated measure analysis showed that the lexical status also impacts the phonemic isolation performance. The performance in pseudo-words was lower than all the others. However, the other clusters of real words did not differ. The results are discussed in the light of previous findings in the literature and of differences in the syllabic structures of the words that may influence phonological awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

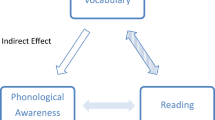

The role of early literacy skills in children’s acquisition of reading and writing has attracted many researchers in various languages, who aimed to investigate the role of different early linguistic and cognitive skills in predicting later reading acquisition (Dickinson et al. 2003). The identification of the specific predictors and the understanding of their relationship to reading process in the different phases of reading acquisition may contribute to improve screening, assessment and intervention strategies. One of the most studied underlying component skills of reading is related to phonological processing (Torgesen et al. 2001; Wagner and Torgesen 1987). Phonological processing is used for a wide range of skills including representation, manipulation, storage and retrieval of speech sounds. Phonological processing includes three basic components: lexical access and verbal short-term memory and phonological awareness-PA (Wagner and Torgesen 1987). PA refers to the explicit awareness of the speech sound structure of language units (Stanovich 1988) or, in other words, the ability to think about the sound of a word rather than just the meaning. PA is a developmental skill that, according to the psycholinguistics grain-size theory (Goswami 2006; Ziegler and Goswami 2005), follows a language-universal sequence in which large grain sizes (i.e., syllables and rimes) develop before smaller grain sizes (i.e., individual phonemes).

There is an almost common agreement that PA is the most important and reliable predictor of beginning reading in different languages and orthographies (Asadi and Khateb 2017; Asadi et al 2017; Elbeheri and Everatt 2007; Stanovich 1988; Taibah and Haynes 2010). The importance of PA to reading, especially in the early stages, derives from the fact that PA is a necessary requirement for the acquisition of the alphabetic principle and a key skill for mastering decoding skills (National Reading Panel 2000). Indeed, processes of grapho-phonemic-conversion (GPC), on which the child depends at the start of reading acquisition, are possibly due to a good ability and awareness of the existing sounds in the language.

According to a view in psycholinguistics, PA involves accessing phonological representation of words, which are memorized and organized in the long-term memory according to their phonological features and therefore, the PA is affected generally by the short-term memory capability (Snowling 2000; Treiman et al. 1993), but also by the specific phonological features and profiles of phonemes and words (Goswami 2000). In this context, the phonological manipulations were found to be affected by the length of the target word and by their syllable structure. Regarding the former, it was reported that short words are easily manipulated as compared to long words (Ibrahim 2011; Treiman and Weatherston 1992). Similarly, manipulating words with a CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) syllable structure was found to be easier than more complex syllabic structures such as CCVC (Treiman 1991). These results were explained by the degree of cognitive skills required for the tasks such as the involvement of the short-term memory when the tasks are more complex or demanding (Treiman et al. 1993). Moreover, the positions of the target phonemes (initial vs. final) which children are required to manipulate are thought to influence the PA performance. Mixed results, however, are reported regarding the position of target phonemes whereas some researchers argued that manipulating final phonemes in kindergarten is more difficult than initial ones (Content et al. 1986; Treiman et al. 1993), and other researchers have reported contrastive results (De Graaff et al. 2008; McBride-Chang 1995; Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004; Saiegh-Haddad et al. 2010).

In addition to the above-mentioned phonological features, the availability of these speech sound structures and the efficiency of their representation in the long-term memory were found to affect PA. Evidence supporting this claim comes from research testing the impact of the lexical status (familiar vs. unfamiliar) on PA whereas manipulations of familiar words, as the case of real words, were found to be easier than the unfamiliar words, as in the case of pseudo-words (Asadi and Ibrahim 2014; Metsala 1999; Saiegh-Haddad 2004). These differences between words and pseudo-words are explained, according to the lexical restructuring model (Metsala 1999; Metsala and Walley 1998; Walley et al. 2003), which claims that PA develops as a result of increases in vocabulary and the spoken language. This model argued that words are initially represented in the lexicon as one unit (holistically) and when children acquire an increasing number of words, phonological information becomes more fine-grained and allows them to differentiate between these words in the lexicon. This differentiation necessitates shifting from holistic to more analytical and segmented forms that allow better access to the smaller units of the words, such as phonemes. Yet this conceptualization of familiarity may be also reflected when children use two (or more) dialects of the same language, which may also influence the quantity and the quality of the phonological and lexical representation in their long-term memory (Saiegh-Haddad et al. 2011). As a result, PA, and its relation to future reading acquisition, may vary between languages depending on the quality of the phonological representation of phonemes and words. This quality may differ between languages depending on the unique characteristics of the language at hand.

The Arabic language is characterized by the phenomenon of diglossia that refers to the existence of two forms of the same language which are used in different situations (Ferguson 1959): There are spoken Arabic dialects (SA) which are used for everyday oral communication purposes, and the literary Arabic (LA, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi 2014) which is used for reading and writing and for formal communication purposes (Saiegh-Haddad and Henkin-Roitfarb 2014). The child uses the spoken language for communication with his surroundings until the pre-school period, around the age of 5–6. Then a deliberate exposure to the standard language starts. It should be noted however, that nowadays, Arabic-speaking children are more exposed to literary Arabic as they watch television and also their parents are more aware of the importance of exposing their children to the literary language at home. The two forms of Arabic are at different linguistic levels including the phonological and semantic ones (see Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004, 2007). At the phonological level, spoken and literary Arabic are characterized through a phonemic range which overlaps, though they are not identical. For example in literary Arabic language, there are some phonemes (

) which do not exist in the spoken language in various dialects but which are replaced by other phonemes that exist in the spoken language. Also, spoken and literary Arabic differ in phonological structure of the syllables which compose the word. For example, while some syllabic structures (e.g., CVC) are shared both in the spoken and the literary languages, there are syllabic structures (e.g., CCVC) that exist in the spoken but not in the literary language; and there are others (e.g., CVCC) that exist in the literary but not in the spoken language. Similarly regarding the lexicon, while there are a number of lexical items which are shared in both versions of the languages such as the word “فيل” /fi:l/, which means ‘elephant’, there are items that exist in the spoken but not in the literary language such as the word “سيد” /si:d/, which means ‘grandfather’; and there are others that exist in the literary but not in the spoken language such as the word “كوب” /ku:b/, which means ‘cup’.

) which do not exist in the spoken language in various dialects but which are replaced by other phonemes that exist in the spoken language. Also, spoken and literary Arabic differ in phonological structure of the syllables which compose the word. For example, while some syllabic structures (e.g., CVC) are shared both in the spoken and the literary languages, there are syllabic structures (e.g., CCVC) that exist in the spoken but not in the literary language; and there are others (e.g., CVCC) that exist in the literary but not in the spoken language. Similarly regarding the lexicon, while there are a number of lexical items which are shared in both versions of the languages such as the word “فيل” /fi:l/, which means ‘elephant’, there are items that exist in the spoken but not in the literary language such as the word “سيد” /si:d/, which means ‘grandfather’; and there are others that exist in the literary but not in the spoken language such as the word “كوب” /ku:b/, which means ‘cup’.

In a series of studies, Saiegh-Haddad (2003, 2004) assessed the impact of phonological and lexical distance between the spoken and the literary language in some phonological analyses in kindergarten and first-grade children. It was found that the phonological and lexical distances reduce the performances of children in phonological manipulations. Specifically, children had more difficulty in manipulating phonemes that exist only in the literary language than with the phonemes that exist also in the spoken variety. Also, manipulating words in LA, which include a formal syllabic structure (e.g., CVCC), is more difficult when compared with words in SA which includes a familiar syllabic structure (i.e., CVCVC, Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004). As for the lexical status, the unexpected results showed that when the target phoneme was not diglossic i.e., existing only in the literary language, the lexical status of the monosyllabic CVCC and disyllabic CVCVC words (literary and spoken, respectively) and pseudo-words did not affect the phonemic isolation of children from kindergarten and first grades (Saiegh-Haddad 2004). Other mixed findings were reported among 1st–12th grade children which aimed to test the impact of the lexical status, using words from different syllabic structures on PA while the performance on phonemic segmentation of spoken words was significantly higher than literary words in all grades, except for the 2nd grade, where an opposite pattern was obtained in the phonemic deletion task (Asadi and Ibrahim 2014).

In sum, the existing findings concerns the impacts of diglossia on phonological manipulations are inconsistent. While phonological manipulations of the standard phonemes were found to be difficult than those exist in the spoken language (Saiegh-Haddad 2003), the lexical status of the items (spoken and standard) did not impact the performance of the children, when the items were composed of phonemes that exist in the spoken version (Saiegh-Haddad 2004). As for the position of target phonemes, whiles some researchers reported that manipulating final phonemes is more difficult than initial ones (Content et al. 1986; Treiman et al. 1993), other researchers have reported contrastive results (Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004).

Given the above mentioned inconsistency in the previous studies’ findings, and given the fact that PA may be influenced by different characteristics of the language at hand, the current study aimed to assess the impact of phonemes and lexical properties on phonemic isolation tasks among pre-school children. Specifically, we aimed to test (a) the impact of the position of the phoneme (initial vs. final) on the phonemic isolation performance and whether this impact changes with age. Also, we aimed to test (b) the impact of the lexical status (shared, spoken, standard, and pseudo-words) on phonemic isolation tasks and whether this impact changes with age. Given that the performance in these tasks is affected by the working memory (Treiman et al. 1993) which is a limited resource, we tested especially kindergartners from the second year (K2) and the third year (K3), and in line with previous findings from Arabic (Saiegh-Haddad 2003), we predict that isolating the initial phonemes will be more difficult than the final ones to which children will listen without any interferences from the following sounds. Also, given the fact that the task will be less demanding with age, we expect that the gap between the initial and the final positions will decrease with age. Regarding the lexical distance and its influence on phonological representation in the lexicon, we predict that manipulation of better represented items, such as shared and spoken words will be easier than literary items and thus manipulation of pseudo-words will be more difficult than all others.

Method

Participants

The details of the participating groups are presented in Table 1. A total of 1012 Arabic-speaking kindergartners (605 girls) participated in this study including 487 (48%) from K2 (Mage in year = 4.74; SD = .51) and 600 (52%) from K3 (Mage in year = 5.71; SD = .49). The participants were recruited from 56 Arabic-speaking preschools from the north, the center and the south of Israel. All participants were from regular kindergartens and none was in special education or had visual or hearing difficulties.

Measures

The phonemic awareness task was developed for the purpose of this study, with the participation of kindergarten teachers. This because there is no Arabic dictionary frequencies. The task consisted of 32 items that aimed to test initial (16) and final (16) phoneme isolation. The items targeted four different clusters that differed in the lexical status of these items: The first cluster comprised shared words, which are similar phonologically and semantically in both the spoken and the literary languages (e.g., /fi:l/ which means ‘elephant’). The second cluster comprised spoken words, which exist only in the spoken language (e.g., /si:χ/ which means ‘knife’). The third cluster comprised standard words, which exist only in the literary language (e.g.,

which means ‘dry’). The fourth cluster comprised pseudo-words derived from both spoken (n = 4) and literary (n = 4) words in which one sound was replaced so that the word became meaningless (e.g., /ri:ħ/ which means ‘wind’, after replacing the final sound /ħ/ with /ʢ/, the new pseudo-word become /ri:ʢ/). All items were nouns and were monosyllabic (CVC) and hence their length was identical in all clusters (three sounds). The items were randomly organized based on their lexical status. The sounds that children were required to isolate represent all the sounds in Arabic but not the standard phonemes (/θ/, /ð/, /ðʕ/, /q/) and long vowels (/a:/, /u:/, /i:/). Also, each phoneme was presented twice: both in the initial and the final positions. During the test, each word was read to the participant who had to repeat it after the examiner and then to isolate the targeted phonemes. One point was assigned for successfully isolating the final or initial phonemes. The reliability of the test (Cronbach’s α) ranged from .92 to .94 in the different grade levels.

which means ‘dry’). The fourth cluster comprised pseudo-words derived from both spoken (n = 4) and literary (n = 4) words in which one sound was replaced so that the word became meaningless (e.g., /ri:ħ/ which means ‘wind’, after replacing the final sound /ħ/ with /ʢ/, the new pseudo-word become /ri:ʢ/). All items were nouns and were monosyllabic (CVC) and hence their length was identical in all clusters (three sounds). The items were randomly organized based on their lexical status. The sounds that children were required to isolate represent all the sounds in Arabic but not the standard phonemes (/θ/, /ð/, /ðʕ/, /q/) and long vowels (/a:/, /u:/, /i:/). Also, each phoneme was presented twice: both in the initial and the final positions. During the test, each word was read to the participant who had to repeat it after the examiner and then to isolate the targeted phonemes. One point was assigned for successfully isolating the final or initial phonemes. The reliability of the test (Cronbach’s α) ranged from .92 to .94 in the different grade levels.

Procedure

Children were individually tested by an experimenter in a quiet room in one of the preschools participating in the study. The meeting lasted for an hour on average including two brakes of a maximum of 10 min long. In order to avoid order effects, half of the children started with the list of words with final isolations, and then they passed to the list with the initial isolations, while the other half started with other list that had an opposite order. As for the lexical status, the items from the four clusters (shared, spoken, standard, and pseudo-words) were randomly ordered in both lists. To carry out this study, experimenters had received training in conducting and coding the tasks. All the examiners were students in the field of education and had all received a specific and detailed training for the administration of the task.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the participants’ scores on the phonemic isolation task for both phoneme positions (initial vs. final) and lexical status (shared, spoken, standard and pseudo-words) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The means reflect the children’s raw score of success. The participants’ average performance on the different measures did not show floor or ceiling effects. In addition, the developmental changes between K2 and K3 for both phonemic position and lexical status were highly significant for all variables (p < .001), a finding that strengthens the validity of the measures used in this study.

To answer our research question, regarding the impact of the phoneme position and grade level on the phoneme isolation task, we used a two-way ANOVA with phoneme position as a ‘within subject’ factor and grade level as a ‘between subjects’ factor. The results revealed a significant effect of phoneme position F(1,1010) = 155.18, p < .001, η2= .133 and grade level F(1,1010) = 260.76, p < .001, η2= .205. The effect of the position was due to higher accuracy in the initial (M = 11.2) than in the final phoneme isolation (M = 9.5), and the grade effect was due to higher performance in K3 (M = 12.3) than in K2 (M = 8.1). In addition, a significant interaction was found between the two factors F(1,1010) = 28.02, p < .001, η2= .027. This interaction was due to the change in the gap (mean differences) between the initial and the final phoneme which seem to be smaller in K3 than in K2 (see Fig. 1). In addition, to ensure that the advantage of the initial phonemes among the final ones was not influenced by the lexical status of the items, the interaction between the two factors was tested and was found to be significant F(5,1009) = 21.02, p < .001, η2= .059. Follow-up pair-wise comparisons revealed significant differences between initial and final phonemes among the shared, spoken, standard and pseudo-words clusters (p < .001). The interaction obtained here was due to the restriction in the gap between initial and final positions in the pseudo-words (see Fig. 2).

As for the impact of the lexical status on the phoneme isolation task, the two-way ANOVAs with repeated measures analyses revealed a significant effect of lexical status F(3,1010) = 13.68, p < .001, η2= .039 and grade level F(3,1010) = 260.75, p < .001, η2= .205. Also, the interaction of lexical status by grade level was found to be significant F(3,1010) = 7.43, p < .01, η2= .007. Follow-up pair-wise comparisons revealed no significant differences between the shared, spoken and standard clusters that, as illustrated in Fig. 3, were all significantly higher (p < .001) than pseudo-words (i.e., shared = spoken = standard > pseudo-words).

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the impact of the position of the target phonemes (initial vs. final) on the phonemic isolation performance and whether the lexical status of the words (shared, spoken, standard and pseudo-words) may impact the phonemic isolation task among 1012 Arabic-speaking kindergartners from K2 and K3. The results we obtained from the analysis of the ANOVA regarding the phonemic position revealed that the performance in initial phonemes was found to be higher than in final phonemes both in K2 and K3 (with larger gaps between the two positions in K2). As for the second research question, and although the main effect obtained in the ANOVA repeated measure analysis, no differences were found between shared, spoken and standard words, which means that the main effect was due only to differences between pseudo-words and the others, whereas the performance in pseudo-words was significantly lower than all the others.

The advantage in initial phonemic isolation on the final phonemic isolation was not in line with our prediction, and was also in contrast with previous findings on the Arabic language (Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004). However, the advantage in manipulating initial phonemes on final phonemes was reported in previous studies (Content et al. 1986; Treiman et al. 1993). The differences from Saiegh-Haddad’s studies may be related mainly to differences in the nature, length and complexity of the syllabic structures (CVCC and CVCVC) used in these studies. Indeed, the author argued that “It is possible that language-specific prosodic constraints may affect the ease with which intra-syllabic units are orally produced as the outcome of phonological analysis” (Saiegh-Haddad 2004, p. 507), especially as PA is also affected by the number of mental operations and working memory load needed to complete the specific manipulation (De Graaff et al. 2008). In the current studies we used a simple CVC syllabic structure that includes fewer sounds and as a result, it is easier to manipulate than more complex syllabic structures. In this same context, and according to the hierarchical onset-rime structure of the syllables, it is more difficult to attend and access final phonemes than initial ones due to the fact that final phonemes constitute, together with the preceding vowel, phonological unit (rime-VC) that is more difficult to access than the initial ones (onset-C) which acts like phonological units on its own (Treiman et al. 1993). Accordingly, our results from Arabic, when using only simple CVC syllables, provide support to onset and rime (C-VC) as preferred sub-syllabic division units, rather than body and coda (CV-C). This is contrary to previous findings from Hebrew that is written in an abjad, whereas children showed preferences for CV as a unit of segmentation and they tend to split CVC items into CV-C i.e., into body-coda (Share and Blum 2005). Hence, more systematic studies with different syllabic structures are needed to confirm these preferences.

The impact of the lexical status on phonemic isolation ability, which was reflected by a modest effect size (η2= .039), was in line with our predictions and was also in line with earlier studies (Asadi and Ibrahim 2014; Metsala 1999). These findings, on the one hand, provide support to the lexical restructuring model (Metsala 1999) which claimed that phonological manipulations of real words, that are already stored and differentiated in the lexicon with more fine-grained phonological information (Walley et al. 2003), should be easier than pseudo-words. Indeed, the main effect obtained here seems to be related mainly to the weaker performance in phonemic isolation of pseudo-words with respect to the other clusters (shared, spoken and standard words). On the other hand, the results showed that, contrary to expectations, the lexical distances between shared, spoken and standard words failed to impact the performance in phonemic isolation tasks. Similar findings however, were reported in previous studies on Arabic (Saiegh-Haddad 2004).

Unlike the support provided for the lexical restructuring model (Metsala 1999) when comparing real words and pseudo-words, the absence of the impact of the lexical distance between the three clusters of real words, despite the differences in their familiarity (especially between standard and the others), is not in total accordance with this model. However, we should keep in mind the differences in the syllabic structures in Arabic that are thought to be simpler than English, especially those used in the current study (CVC). Again, the performance in phonological manipulations is influenced by the length and complexity of the syllabic structure of the words (Treiman 1991; Treiman and Weatherston 1992). Using simple CVC items in this study may explain the effect of the absence of familiarity between shared, spoken and standard words (Saiegh-Haddad 2004). It is worth noting that in addition to the simple syllabic structure of the words, these words included phonemes that are not diglossic, which also make this task less demanding. Hence, the effect of familiarity could be expressed more with challenging and demanding items.

To conclude, this study provides evidence for the impact of the phonemic position on phonemic isolation ability in which isolating initial phonemes was easier than final ones. In addition, the impact of the lexical status on phonemic isolation was also tested; the results showed that the lexical status of the items impacts the performance in phonemic isolation, in particular when the distance between word clusters is more notable, as between pseudo-words and the others. However, when the distance between these clusters is less critical, as between the clusters of real words whereas the task is less demanding, this impact evaporates. Implications arising from this research are related to theoretical, methodological and pedagogical aspects: the advantage of the initial phonemic position rather than the final one in phonemic isolation tasks supports the onset rime (C-VC) structure, rather body coda (CV-C) as preferred sub-syllabic division units. Also, the advantage of the real words rather than pseudo-words provided a partial support to the lexical restructuring model. As for the methodological implication, the variety in the findings from different studies seems to be partly related to differences in the properties of the items that may obscure the interpretation of these findings. Future research should take into consideration the differences in the nature, complexity and length of the syllabic structures used in the different studies. Pedagogically, understanding the influence of specific properties of word and sound features on PA may be particularly important in intervention programs, especially for Arabic-speaking children in light of the diglossic reality they face in developing both oral language and future academic skills. In general, kindergarten teachers should expose kindergarten children to more phonological manipulations activities in the different versions, spoken as well as literary Arabic. However, they should be aware of the differences between initial and final phonemes when they manipulate simple items (CVC). Our result indicates that initial phonemes are easier to manipulate than final ones, and hence, assessments and intervention programs have to start, with less challenging items and may gradually move to more challenging ones. Hence, we recommended that phonological manipulation starts with initial phonemes and then move gradually to final phonemes. One limitation of this study is related to the fact that nearly all the spoken words used in this study may be appropriate for the vast majority of participants, but not all of them, especially as our study included a large sample of children from various parts of Israel.

References

Asadi, I. A., & Ibrahim, R. (2014). The influence of diglossia on different types of phonological abilities in Arabic. Journal of Education and Learning. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v3n3p45.

Asadi, I. A., & Khateb, A. (2017). Predicting reading in vowelized and unvowelized Arabic script: An investigation of reading in first and second grades. Journal of Reading Psychology, 38(5), 486–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1299821.

Asadi, I. A., Khateb, A., Ibrahim, R., & Taha, H. (2017). How do the different cognitive and linguistic factors contribute to reading in Arabic? A large scale developmental. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(9), 1835–1867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9755-z.

Content, A., Kolinsky, R., Morais, J., & Bertelson, P. (1986). Phonetic segmentation in prereaders: Effect of corrective information. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 42(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0965(86)90015-9.

De Graaff, S., Hasselman, F., Bosman, A. M., & Verhoeven, L. (2008). Cognitive and linguistic constraints on phoneme isolation in Dutch kindergartners. Learning and Instruction, 18(4), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.08.001.

Dickinson, D. K., McCabe, A., Anastasopoulos, L., Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., & Poe, M. D. (2003). The comprehensive language approach to early literacy: The interrelationships among vocabulary, phonological sensitivity, and print knowledge among preschool-aged children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.3.465.

Elbeheri, G., & Everatt, J. (2007). Literacy ability and phonological processing skills amongst dyslexic and non-dyslexic speakers of Arabic. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-006-9031-0.

Ferguson, C. A. (1959). Diglossia. Word, 15(2), 325–340.

Goswami, U. (2000). Phonological representation, reading development and dyslexia: Toward a cross-linguistic theoretical framework. Dyslexia, 6(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:2%3c133:AID-DYS160%3e3.0.CO;2-A.

Goswami, U. (2006). Orthography, phonology, and reading development: A cross-linguistic perspective. In R. M. Joshi & P. G. Aaron (Eds.), Handbook of orthography and literacy (pp. 463–480). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ibrahim, R. (2011). Literacy problems in Arabic: Sensitivity to diglossia in tasks involving working memory. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 24(5), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2010.10.003.

McBride-Chang, C. (1995). What is phonological awareness? Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.2.179.

Metsala, J. L. (1999). Young children’s phonological awareness and nonword repetition as a function of vocabulary development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.3.

Metsala, J. L., & Walley, A. C. (1998). Spoken vocabulary growth and the segmental restructuring of lexical representations: Precursors to phonemic awareness and early reading ability. In J. L. Metsala & L. C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp. 89–120). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2003). Linguistic distance and initial reading acquisition: The case of Arabic diglossia. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24(3), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716403000225.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2004). The impact of phonemic and lexical distance on the phonological analysis of words and pseudowords in a diglossic context. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25(4), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716404001249.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2007). Linguistic constraints children’s ability to isolate phonemes in diglossic Arabic. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(4), 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716407070336.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., & Henkin-Roitfarb, R. (2014). The structure of Arabic language and orthography. In E. Saiegh-Haddad & M. Joshi (Eds.), handbook of Arabic literacy: Insights and perspectives (pp. 3–28). Dordrecht: Springer.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., & Joshi, M. (2014). Handbook of Arabic literacy: Insights and perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., Kogan, N., & Walters, J. (2010). Universal and language-specific constraints on phonemic awareness: evidence from Russian-Hebrew bilingual children. Reading and Writing, 23(3–4), 359–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-009-9204-8.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., Levin, I., Hende, N., & Ziv, M. (2011). The linguistic affiliation constraint and phoneme recognition in diglossic Arabic. Journal of Child Language, 38(2), 279–315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000909990365.

Share, D. L., & Blum, P. (2005). Syllable splitting in literate and pre-literate Hebrew speakers: Onsets and rimes or bodies and codas. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 182–202.

Snowling, M. J. (2000). Dyslexia (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Stanovich, K. E. (1988). The right and wrong places to look for the cognitive locus of reading disability. Annals of Dyslexia, 38(1), 154–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02648254.

Taibah, N. J., & Haynes, C. W. (2010). Contributions of phonological processing skills to reading skills in Arabic speaking children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 24(9), 1019–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9273-8.

Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: mmediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940103400104.

Treiman, R. (1991). Children’s spelling errors on syllable-initial consonant clusters. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 346–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.3.346.

Treiman, R., Berch, D., & Weatherston, S. (1993). Children’s use of phoneme-grapheme correspondences in spelling: Roles of position and stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.85.3.466.

Treiman, R., & Weatherston, S. (1992). Effects of linguistic structure on children’s ability to isolate initial consonants. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(2), 174–181.

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.192.

Walley, A. C., Metsala, J. L., & Garlock, V. M. (2003). Spoken vocabulary growth: Its role in the development of phoneme awareness and early reading ability. Reading and Writing: An InterdisciplinaryJournal, 16(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021789804977.

Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: A psycholinguistic grain size theory. Psychological Bulletin, 13(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asadi, I.A., Abu-Rabia, S. The Impact of the Position of Phonemes and Lexical Status on Phonological Awareness in the Diglossic Arabic Language. J Psycholinguist Res 48, 1051–1062 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-019-09646-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-019-09646-x