Abstract

Brief contact intervention (BCI) is a low-cost intervention to prevent re-attempt suicide. This meta-analysis and meta-regression study aimed to evaluate the effect of BCI on re-attempt prevention following suicide attempts (SAs). We systematically searched using defined keywords in MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus up to April, 2023. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion after quality assessment. Random-effects model and subgroup analysis were used to estimate pooled risk difference (RD) and risk ratio (RR) between BCI and re-attempt prevention with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Meta-regression analysis was carried out to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity. The pooled estimates were (RD = 4%; 95% CI 2–6%); and (RR = 0.62; 95% CI 0.48–0.77). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that more than 12 months intervention (RR = 0.46; 95% CI 0.10–0.82) versus 12 months or less (RR = 0.67; 95% CI 0.54–0.80) increased the effectiveness of BCI on re-attempt suicide reduction. Meta-regression analysis explored that BCI time (more than 12 months), BCI type, age, and female sex were the potential sources of the heterogeneity. The meta-analysis indicated that BCI could be a valuable strategy to prevent suicide re-attempts. BCI could be utilized within suicide prevention strategies as a surveillance component of mental health since BCI requires low-cost and low-educated healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is recognized as a critical public health issue by the World Health Organization in its Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (Fakhari et al., 2022a; Saab et al., 2021). Annually, almost one million people have died from suicide around the world (Azizi et al., 2021). The global age-adjusted rate for suicide was 10.5 per 100,000 persons in 2016 (Fakhari et al., 2021a). Suicide was the leading cause of age-standardized years of life lost in the Global Burden of Disease region of high-income Asia Pacific countries. Suicide is also the top ten causes of mortality in regions of Eastern Europe, Central Europe, Western Europe, Central Asia, Australasia, southern Latin America, and high-income North America Global suicide deaths and proportions increased by 817,000 (from 762,000 to 884,000) and 6.7% (95% confidence interval from 0.4 to 15.6%) in 2016, respectively (Naghavi, 1990; Tait & Michail, 2014).

Findings indicated that most re-attempt suicides took place within the first-6 months of follow-up after suicide attempted (SA). It is estimated that 19% of previously attempted suicide survivors have re-attempted suicide within two years (Irigoyen et al., 2019). Mendez-Bustos et al., in a systematic review of 86 studies found re-attempt suicide was associated with the history of suicidal behavior, suicide ideation, unemployment, single status, psychiatric disorders, and stressful life events (Mendez-Bustos et al., 2013). Evidence showed that alcohol abuse, anxiety disorder, and individuals with a history of more than 2 SAs in the past 3 years were found to be significantly associated with the risk of a further SA (Appleby et al., 1997; Demesmaeker et al., 2021). Likewise, a prospective study in Iran revealed that 81.3% of suicide re-attempters have occurred within the first-18 months of followed-up (Esmaeili et al., 2021).

Suicide prevention is a global priority (WHO 2013–2030) and one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 3.4.2) (Organization, 2018). Numerous studies have been conducted on preventive measures and strategies to prevent suicide re-attempts (Beautrais et al., 2010; Bongiorno et al., 2020; Fleischmann et al., 2008; López-Goñi & Goñi-Sarriés, 2021; Luxton & June, 2013). For example, one study compared communication patterns immediately before attempting suicide with low-risk periods, by analyzing private text messages (SMS), and identified patterns such as the idea of suicide or depression in them (Glenn et al., 2020). Other studies evaluated the role of psycho-social (Silva et al., 2021), and psychopharmacological (Michel et al., 2021) interventions with insignificant associations following SA, and a study assessed telephone calls (Vaiva et al., 2011) at 4 and 8 months after a SA and no significant association was found between the intervention and control group in the number of subsequent attempters in one year.

Brief Contact Interventions (BCIs) are low-cost, non-intrusive interventions that seek to maintain long-term contact with patients after SA, without the provision of additional therapies (Milner et al., 2016). Findings showed that BCI was associated with a lower risk of suicide after SA through using measures that seek to maintain long-term contact with patients after SA or suicidal behaviors. After any suicidal behaviors, BCI could have an important element of prevention against suicide and SA (Riblet et al., 2017). Prevention of suicide re-attempt is a high priority in mental health systems; however, the summary and pooled effect of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention across sex, age and the lifespan is poorly understood. A cohort study of people who survived suicide during two years of follow-up periods indicated that psychotherapy was not significant to prevent a re-attempt in the high-risk population (Irigoyen et al., 2019).

There is increasing interest in the mental health profession in the use of the most effective suicide prevention interventions and programs, where the majority of suicides and SA have occurred among cases who have the history of SA (Pinikahana et al., 2003; Procter, 2005). The BCI could be used for improving mental health practice at a huge level in both low and high resource settings, given the BCI needs low-cost and low-educated healthcare providers. Low-cost and brief interventions are suggested to prevent suicide (Ammerman et al., 2020; Irigoyen et al., 2019). Follow-up contacting of attempters is an effective and low-cost strategy for re-attempt suicide prevention. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive meta-analysis and meta-regression were conducted on the effect of BCI such as telephone, text message, and postcard follow-up to prevent re-attempt suicide.

The present systematic review, meta-analysis, and met-regression aimed to provide and synthesize the role of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention among attempters by pooled estimating of measure of associations including risk difference (RD) and risk ratio (RR) and also to explain the potential sources of the heterogeneity between studies, and how BCI would work better for some groups of populations regarding demographic characteristics.

Methods

Search Strategy

We have conducted a Literature search systematically in all databases including Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE/PubMed (via Ovid) and Embase from database inception up to April 2023. Besides, we have also included the critical information from the reports and website of World Health Organization (WHO). The reference lists of all identified records were screened to find out more relevant studies. We searched records reporting any interventions against re-attempt suicide among the first-time attempters. The initial search terms were “re-attempt” OR “suicide” in the title and/or abstract. The final search used the relevant MeSH terms and text words related to re-attempt in conjunction with “recurrent” OR “again” AND “suicide” OR “attempt” OR “attempted” OR “suicidal behavior” OR “suicidal behavior” AND “prevention” OR “control” OR “intervention” OR “telephone” OR “postcard” OR “message” OR “phone” OR “call.” There were no language restrictions.

Brief Contact Intervention (BCI)

BCI can be defined as a method of regular brief caring or follow-up of the SA after discharge through telephone calls, messages, letter reminders, SMS, or postcard to reduce or against re-attempt suicide irrespective of their age and gender. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) articles evaluated the effect of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention were eligible for the study.

Eligibility

The study included only RCTs. Therefore, the inclusion criteria were all RCTs assessed the impact/effectiveness of BCI in the prevention of recurrent/reattempt suicide and/or attempt after a SA (previous).

The exclusion criteria were:

-

(1)

Reviews, letters, conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries, study protocol, cross-sectional and observational studies, and qualitative articles,

-

(2)

Studies assessed the prevention of suicidal behaviors among patients/people who had no history of suicidal behavior in the past,

-

(3)

Studies compared the effect of two brief interventions and/or smartphone applications in preventing suicide reattempt,

-

(4)

Drug treatments in prevention of repeat/reattempt suicidal behaviors

Comparison

The impact of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention was compared between groups (intervention and control) among the included RCT articles. The control group was Treatment as Usual (TAU), and the intervention group was TAU + BCI. No brief intervention contacts were done for controls (they received routine care). For TAU group, there was reported no follow-up care in the original studies.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was risk difference (RD) (Mansournia et al., 2021, 2021b) of re-attempt between intervention and control groups among first-time suicide attempters. The secondary outcome measure was risk ratio (RR).

Data Selection and Extraction

Two reviewers (HA, EDE) screened and selected independently, in a blinded and standardized way, the relevant full-text records via the title and abstract screening. Data extracted comprised the name of the first author, publication year, country, type of intervention, intervention time (12 months or less vs. more than 12 months), number of samples and study groups, demographic characteristics of participants, and effect measures including RR and RD.

Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

The quality of included articles was assessed using the modified Downs and Black checklist. The checklist was designed to model judgments according to the grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluations (GRADE) criteria and comprising the following domains: (a) Reporting (b) External validity (c) Internal validity (bias) (d) Internal validity (confounding- selection bias) (Mansournia et al., 2017, 2018), and “(e) Power (Greenland 2015). Following the original guidance by Downs and Black, (though with a slight variation), we derived an overall summary risk of bias judgment (excellent; good; fair; poor) for each specific outcome, whereby the overall risk of bias for each study was determined by the highest risk of bias level in any of the domains that were assessed (Table 1). All of instrument items were evaluated in a blinded, standardized way by two authors (HA and EDE) how were Epidemiologist. The final included studies were decided through the consensus of the two authors (HA, EDE). If disagreements, the third author (AF) would make the final decision.

Statistical Approach

Random-effects model (Grindem et al., 2019) was used to estimate the pooled risks ratio (RR); the ratio of the probability of suicide re-attempt in the intervention group (BCI) to the probability of in the control group; and risk difference (RD); the difference in risk of suicide re-attempt between the intervention group and control group; to the association between the impact of BCI and suicide re-attempt prevention (reduction) with 95% confidence intervals (Mansournia et al., 2022, Greenland, 2022) . Subgroup analyses were done by intervention time (12 months or less, and more than 12 months). I2 was used to assess between studies heterogeneity. Then, we carried out a meta-regression analysis to explain the effect of age, sex, BCI duration (more than 12 months vs. less than 12), on the heterogeneity, when I2 was above 50% (Fathizadeh et al., 2020).The age and BCI duration were considered as quantitative variables, and for sex, we included the proportion of female sex ratio for each study in the meta-regression analysis. All analysis were performed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Characteristics of Studies

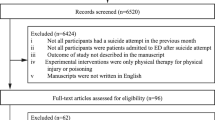

Through electronic searching, we identified 67,582 articles from which titles and abstracts were reviewed according to the inclusion criteria so that 236 studies were selected for full-text screening.. Finally, 19 RCTs, shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), were included in the meta-analysis. Out of those, 19 and 17 RCTs were assessed in the meta-regression analysis for exploring the potential sources of the heterogeneity of pooled RD and RR, respectively. Two article not reported values for RR and/or absolute numbers.

Table 2 shows characteristics of the studies, published between 2002 and 2022 , including 13,715first-time SA participants. The mean (range) age of the participants was 32 (26–45) years and 60% (range: 55–74%) of them were female. Also 12 studies (70%) have continued the BCI for 12 months or less (Table 2).

Meta-analysis

Among the studies included the highest (28%) and lowest (− 0.02%) RD were reported in Gysin-Maillart et al. (2016) and Evans et al. (2005) studies, respectively. Likewise, the highest (0.10) and lowest (1.26) RR were reported by Amadéo et al. (2015), and Fleischmann et al. (2008).

A random effects meta-analysis using 19 RCTs yielded the pooled RD estimate of 4% (95% CI–6%); I2 = 68.9%, suggesting that the risk of re-attempt suicide among attempters who received BCI intervention was 54 lower than control (TAU) attempters. Moreover, the random effects analysis of RR over 19 studies showed a protective effect for BCI with RR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.48–0.77); I2 = 34.2%; indicating that in the BCI group, suicide re-attempt risk was 0.64 times that of the control group (risk of re-attempt suicide was 0.64 times lower in the BCI group).

Subgroup Analysis by BCI Follow-up Time

The pooled RD was 13% (95% CI 3–23%); I2 = 80.3% for “more than 12 months”, and 23 (95% CI 1–4%) I2 = 32.6% for “12 months or less” (Fig. 2).

The pooled RR was 0.46 (95% CI 0.10–0.82); I2 = 60.8%; for “more than 12 months”, and 0.67 (95% CI 0.54–0.80); I2 = 0.0%; for “12 months or less” (Fig. 3). The interaction p-value was 0.002 and indicated that the impact of BCI was significant among groups of attempters who followed-up more than 12 months.

Meta-regression

Table 3 indicates the potential sources of the heterogeneity (between studies variations) for estimating pooled RD using a multivariable meta-regression. BCI follow-up time (more than 12 months vs. 12 months or less), BCI type (single brief intervention vs. multi interventions), age (quantitative), and female sex (the proportion (%) of female participants in each study) all together explained 100% of the total variance between studies. These four variables together explained the main differences between studies regarding the measure of association (RD) in the association between BCI role and prevention of suicide re-attempt. According to the meta-regression analysis results, the effect of BCI was better in the following groups of attempters: more than 12 months BCI, BCI type (multi interventions), female sex, and young ages. In the other words, the impact of BCI was different regarding BCI time, sex, and age.

No meta-regression analysis was carried out for summary RR since the value of I-squared was 34% (less than 50%).

Discussion

This study is one of the limited meta-analysis and meta-regression of RCT studies, indicating the pooled estimates of risk difference (RD) and risk ratio (RR) measures for evaluating the impact of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention. The study findings identified a statistically significant association between BCI and re-attempt, showing a significant decrease in re-attempt suicide. The pooled RR estimate indicated that first-time suicide attempters who received BCI intervention had a lower risk (0.62 times) of re-attempt than the control group after discharge of SA. Likewise, pooled RD measure was 4% (95% CI 2–7%), and the risk of re-attempt in the BCI group was 4% lower than in the control group. This study pooled data from 19 RCTs, showing a significant protective role of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention after discharge of SA.

Furthermore, our met-regression analysis revealed that the impact of BCI is different based on BCI time (more than 12 months follow-up vs. 12 months or less), female sex, and age. These variables explained the between studies variations. Moreover, in subgroup analysis by BCI time, we explored that “more than 12 months” more decreased the risk of re-attempt than “12 months or less”. Therefore, the findings of this study emphasize the effectiveness of more than 12 months of BCI time on re-attempt suicide prevention. This finding in addition to being effective in the effective application of BCI in the field, can also be a departure point for conducting future studies. Therefore, this review recommends BCI is more effective when follow-up time is more than 12 months, amongst female sex, and not advanced age.

Regarding sex differences in suicide, commonly known as the gender paradox in suicide. While men are more likely to suicide, SA is more frequent in female sex. Although there are exceptions, this paradox occurs in most countries over the world, and it is partially explained by the preference of men for more lethal methods. (Azizi et al., 2021; Barrigon & Cegla-Schvartzman, 2020; Hawton, 2000). Given that BCI is implemented after SA it could be more effective among the female sex to prevent reattempt.

In the current study, as in most of the original studies, BCI has reduced suicide re-attempt. In some original studies, BCI also reduced suicide re-attempts while there was no significant association. However, this meta-analysis increased statistical power by increasing the sample size, and determined small but clinically significant effects by combining data from numerous studies. So the results of this meta-analyses can provide better estimates of the relation in the population than single studies. The precision and validity of estimates can be improved as more data are used in a meta-analysis, and the increased amount of data increases the statistical power to detect an effect and finally achieve significant results in pooled estimation.

Suicide mortality was different in different places, between sexes, and among different age groups (Farahbakhsh et al., 2020; Ferrari et al., 2014; Rezaeian, 2000). Suicide prevention measures that are informed by variances in death rates might be directed towards vulnerable populations (Naghavi, 1990). It is estimated that there were 5 hospitalizations and 22 emergency ward admissions, for every suicide (Pearson et al., 2001). Previous findings reported that 16–34% of the individuals re-attempted within the first 1–2 years after a SA (Mendez-Bustos et al., 2013). The economic and social implications of suicide and re-attempt suicide have led to progress of investigation on this type of social issue.

Suicide is a serious and emergency phenomenon and often occurs due to social and cultural issues and stressful life events (Fakhari et al., 2021b, 2022a). Therefore, BCI with regular follow-up of those taking action and providing support and counseling services, and referring them in needed situations provides a very decisive role in preventing re-attempt suicide. In line with the results of this review, community-based suicide prevention interventions and programs have shown that the management and follow-up of suicide attempters is one of the effective interventions in suicide prevention (Azizi et al., 2021; Fakhari et al., 2022b).

In this study, telephone calls were the common BCI intervention among included studies. Telephone calls and reminder letters or crisis or postcards are easy, low-cost, and relatively safe interventions to implement re-attempt risk reduction(Messiah et al., 2019). Contacting suicide attempters by phone and letter or card 6–18 months after attempted suicide can help reduce the proportion of people who re-attempted. Mobile contact and follow-up also enable identifying high-risk persons of further suicidal behaviors and timely referral for emergency care (Vaiva et al., 2006).

Considering the diversity and generally limited community-based resources for suicide attempters, BCI may have a significant role on re-attempt suicide prevention and health care costs, and can be easily applied in the various contexts (Gysin-Maillart et al., 2016). Therefore, the present study had high internal and external validity by including RCT studies and real-world settings.

Furthermore, BCI could be kept within a multimodal strategy as a surveillance component, results of which could trigger more significant actions, including referring to health care, psychiatric and psychological contacts and therapeutic efforts.

Limitations

The study had some limitations. The study included RCTs conducted with different BCI types and from different settings adding a range of incidence rates for suicide and SA. To solve this problem, we measured the quality and risk of bias in these studies. Besides, to explore the impact of BCI type and the potential sources of the heterogeneity, a multivariable meta-regression analysis was performed.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that BCI could be a useful strategy to prevent re-attempt rates among first-time suicide attempters. Meta-analysis using random-effects model demonstrated pooled RD and RR estimates of BCI on re-attempt suicide prevention (RD = 4% 95% CI 2–6%; and RR = 0.62 95% CI 0.48–0.77). Subgroup analysis revealed that more than 12 months BCI time was effective than 12 months or less in re-attempt prevention. Moreover, meta-regression analysis explored that BCI time (more than 12 months), the sample size of studies included, age, and sex (female) of the participants were the main sources of the heterogeneity.

Therefore, to address this ongoing public health problem, research must continue to provide the evidence basis for effective interventions that are responsive to local and national settings. Furthermore, BCI as evidence that recommended in this study could be utilized within suicide prevention programs as a surveillance component, since BCI require low-cost and unspecialized healthcare providers.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCI:

-

Brief contact intervention

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CHWs:

-

Community health workers

- PHC:

-

Primary health care

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- RD:

-

Risk difference

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SAs:

-

Suicide attempters

- SBs:

-

Suicidal behaviors

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

References

Amadéo, S., Rereao, M., Malogne, A., Favro, P., Nguyen, N. L., Jehel, L., Milner, A., Kolves, K., & De Leo, D. (2015). Testing brief intervention and phone contact among subjects with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial in French Polynesia in the frames of the World health organization/suicide trends in at-risk territories study. Mental Illness, 7(2), 48–53.

Ammerman, B. A., Gebhardt, H. M., Lee, J. M., Tucker, R. P., Matarazzo, B. B., & Reger, M. A. (2020). Differential preferences for the caring contacts suicide prevention intervention based on patient characteristics. Archives of Suicide Research, 24(3), 301–312.

Appleby, L., Shaw, J., & Amos, T. (1997). National confidential inquiry into suicide and homicide by people with mental illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 101–102.

Azizi, H., Fakhari, A., Farahbakhsh, M., Esmaeili, E. D., & Mirzapour, M. (2021). Outcomes of community-based suicide prevention program in primary health care of Iran. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 1–11.

Barrigon, M. L., & Cegla-Schvartzman, F. (2020). Sex, gender, and suicidal behavior. Behavioral Neurobiology of Suicide and Self Harm, 46, 89–115.

Beautrais, A. L., Gibb, S. J., Faulkner, A., Fergusson, D. M., & Mulder, R. T. (2010). Postcard intervention for repeat self-harm: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(1), 55–60.

Bertolote, J., Fleischmann, A., De Leo, D., Phillips, M., Botega, N., Vijayakumar, L., De Silva, D., Schlebusch, L., Van Tuong, N., & Sisask, M. (2010). Repetition of suicide attempts: Data from five culturally different low-and middle-income country emergency care settings participating in the WHO SUPRE-MISS study. Crisis, 31(4), 194–201.

Bongiorno, D. M., Kramer, E. N., Booty, M. D., & Crifasi, C. K. (2020). Development of an online map of safe gun storage sites in Maryland for suicide prevention. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(7), 626–630.

Carter, G. L., Clover, K., Whyte, I. M., Dawson, A. H., & D’Este, C. (2007). Postcards from the EDge: 24-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 548–553.

Cedereke, M., Monti, K., & Öjehagen, A. (2002). Telephone contact with patients in the year after a suicide attempt: Does it affect treatment attendance and outcome? A Randomised Controlled Study. European Psychiatry, 17(2), 82–91.

Chen, W.-J., Ho, C.-K., Shyu, S.-S., Chen, C.-C., Lin, G.-G., Chou, L.-S., Fang, Y.-J., Yeh, P.-Y., & Chung, T.-C. (2013). Chou FH-C: Employing crisis postcards with case management in Kaohsiung, Taiwan: 6-month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–7.

Comtois, K. A., Kerbrat, A. H., DeCou, C. R., Atkins, D. C., Majeres, J. J., Baker, J. C., & Ries, R. K. (2019). Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 474–483.

da Silva, A. P. C., Henriques, M. R., Rothes, I. A., Zortea, T., Santos, J. C., & Cuijpers, P. (2021). Effects of psychosocial interventions among people cared for in emergency departments after a suicide attempt: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1–10.

Demesmaeker, A., Chazard, E., Vaiva, G., & Amad, A. (2021). Risk factors for reattempt and suicide within 6 months after an attempt in the French ALGOS Cohort: A survival tree analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(1), 25951.

Esmaeili, E. D., Farahbakhsh, M., Sarbazi, E., Khodamoradi, F., & Azizi, H. (2021). Predictors and incidence rate of suicide re-attempt among suicide attempters: A prospective study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 69, 102999.

Evans, J., Evans, M., Morgan, H. G., Hayward, A., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Crisis card following self-harm: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(2), 186–187.

Fakhari, A., Allahverdipour, H., Esmaeili, E. D., Chattu, V. K., Salehiniya, H., & Azizi, H. (2022a). Early marriage, stressful life events and risk of suicide and suicide attempt: A case–control study in Iran. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–11.

Fakhari, A., Azizi, H., Farahbakhsh, M., & Esmaeili, E. D. (2022b). Effective programs on suicide prevention: Combination of review of systematic reviews with expert opinions. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 13, 39.

Fakhari, A., Farahbakhsh, M., Esmaeili, E. D., & Azizi, H. (2021a). A longitudinal study of suicide and suicide attempt in northwest of Iran: Incidence, predictors, and socioeconomic status and the role of sociocultural status. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1486.

Fakhari, A., Farahbakhsh, M., Esmaeili, E. D., & Azizi, H. (2021b). A longitudinal study of suicide and suicide attempt in northwest of Iran: Incidence, predictors, and socioeconomic status and the role of sociocultural status. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–11.

Farahbakhsh, M., Fakhari, A., Davtalab Esmaeili, E., Azizi, H., Mizapour, M., Asl Rahimi, V., & Hashemi, L. (2020). The role and comparison of stressful life events in suicide and suicide attempt: A descriptive-analytical study. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), e96051.

Fathizadeh, H., Milajerdi, A., Reiner, Ž, Amirani, E., Asemi, Z., Mansournia, M. A., & Hallajzadeh, J. (2020). The effects of L-carnitine supplementation on indicators of inflammation and oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 19, 1879–1894.

Ferrari, A. J., Norman, R. E., Freedman, G., Baxter, A. J., Pirkis, J. E., Harris, M. G., Page, A., Carnahan, E., Degenhardt, L., & Vos, T. (2014). The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e91936.

Fleischmann, A., Bertolote, J. M., Wasserman, D., De Leo, D., Bolhari, J., Botega, N. J., De Silva, D., Phillips, M., Vijayakumar, L., & Värnik, A. (2008). Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: A randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86, 703–709.

Glenn, J. J., Nobles, A. L., Barnes, L. E., & Teachman, B. A. (2020). Can text messages identify suicide risk in real time? A within-subjects pilot examination of temporally sensitive markers of suicide risk. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(4), 704–722.

Goñi-Sarriés, A., Yárnoz-Goñi, N., & López-Goñi, J. J. (2022). Psychiatric hospitalization for attempted suicide and reattempt at the one-year follow-up. Psicothema, 34(3), 375–382.

Greenland S, Mansournia MA. (2015). Limitations of individual causal models, causal graphs, and ignorability assumptions, as illustrated by random confounding and design unfaithfulness. European Journal of Epidemiology, 359, 1101-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-9995-7

Greenland S. (2022). To curb research misreporting replace significance and confidence by compatibility Preventive Medicine. 164, 107127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107127

Grindem, H., Mansournia, M. A., Øiestad, B. E., & Ardern, C. L. (2019). Was it a good idea to combine the studies? Why clinicians should care about heterogeneity when making decisions based on systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(7), 399–401.

Gysin-Maillart, A., Schwab, S., Soravia, L., Megert, M., & Michel, K. (2016). A novel brief therapy for patients who attempt suicide: A 24-months follow-up randomized controlled study of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP). PLoS Medicine, 13(3), e1001968.

Hassanian-Moghaddam, H., Sarjami, S., Kolahi, A.-A., & Carter, G. L. (2011). Postcards in Persia: Randomised controlled trial to reduce suicidal behaviours 12 months after hospital-treated self-poisoning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(4), 309–316.

Hawton, K. (2000). Sex and suicide: Gender differences in suicidal behaviour. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 484–485.

Irigoyen, M., Porras-Segovia, A., Galván, L., Puigdevall, M., Giner, L., De Leon, S., & Baca-García, E. (2019). Predictors of re-attempt in a cohort of suicide attempters: A survival analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 247, 20–28.

López-Goñi, J. J., & Goñi-Sarriés, A. (2021). Effectiveness of a telephone prevention programme on the recurrence of suicidal behaviour. One-Year Follow-up. Psychiatry Research, 302, 114029.

Luxton, D. D., June, J. D., & Comtois, K. A. (2013). Can postdischarge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? Crisis

Malakouti, S. K., Nojomi, M., Ghanbari, B., Rasouli, N., Khaleghparast, S., & Farahani, I. G. (2021). Aftercare and suicide reattempt prevention in Tehran, Iran: Outcome of 12-month randomized controlled study. Crisis the Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 43(1), 18–27.

Mansournia, M. A., Altman, D. G. (2018). Invited commentary: methodological issues in the design and analysis of randomised trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(9) 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098245

Mansournia, M. A., Collins, G. S., Nielsen, R. O., Nazemipour, M., Jewell, N. P., Altman, D. G., & Campbell, M. J. (2021). CHecklist for statistical Assessment of Medical Papers: the CHAMP statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(18), 1009–1017.

Mansournia M. A. (2022). P-value compatibility and S-value. Global Epidemiology. 4, 100085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloepi.2022.100085

Mansournia, M. A., Altman, D. G. (2022). Population attributable fraction. British Medical Journal, 360, k757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k757

Mansournia, M. A., Higgins, J. P., Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A. (2022). Biases in Randomized Trials: A Conversation Between Trialists and Epidemiologists. Epidemiology, 28(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000564

Mendez-Bustos, P., de Leon-Martinez, V., Miret, M., Baca-Garcia, E., & Lopez-Castroman, J. (2013). Suicide reattempters: A systematic review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21(6), 281–295.

Messiah, A., Notredame, C.-E., Demarty, A.-L., Duhem, S., & Vaiva, G. (2019). Investigators A: Combining green cards, telephone calls and postcards into an intervention algorithm to reduce suicide reattempt (AlgoS): P-hoc analyses of an inconclusive randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0210778.

Michel, K., Gysin-Maillart, A., Breit, S., Walther, S., & Pavlidou, A. (2021). Psychopharmacological treatment is not associated with reduced suicide ideation and reattempts in an observational follow-up study of suicide attempters. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 140, 180–186.

Milner, A., Spittal, M. J., Kapur, N., Witt, K., Pirkis, J., & Carter, G. (2016). Mechanisms of brief contact interventions in clinical populations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1–10.

Mousavi, S. G., Zohreh, R., Maracy, M. R., Ebrahimi, A., & Sharbafchi, M. R. (2014). The efficacy of telephonic follow up in prevention of suicidal reattempt in patients with suicide attempt history. Advanced Biomedical Research, 3, 198.

Naghavi, M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ, 364, 94.

O’Connor, R. C., Ferguson, E., Scott, F., Smyth, R., McDaid, D., Park, A.-L., Beautrais, A., & Armitage, C. J. (2017). A brief psychological intervention to reduce repetition of self-harm in patients admitted to hospital following a suicide attempt: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(6), 451–460.

Organization WH (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: Progress, examples and indicators.

Pearson, J. L., Stanley, B., King, C. A., & Fisher, C. B. (2001). Intervention research with persons at high risk for suicidality: Safety and ethical considerations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 17–26.

Pinikahana, J., Happell, B., & Keks, N. A. (2003). Suicide and schizophrenia: A review of literature for the decade (1990–1999) and implications for mental health nursing. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24(1), 27–43.

Procter, N. G. (2005). Parasuicide, self-harm and suicide in Aboriginal people in rural Australia: A review of the literature with implications for mental health nursing practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 11(5), 237–241.

Rezaeian, M. (2007). Age and sex suicide rates in the Eastern Mediterranean Region based on global burden of disease estimates for 2000. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 13(4), 953–960.

Riblet, N. B., Shiner, B., Young-Xu, Y., & Watts, B. V. (2017). Strategies to prevent death by suicide: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 396–402.

Robinson, J., Yuen, H. P., Gook, S., Hughes, A., Cosgrave, E., Killackey, E., Baker, K., Jorm, A., McGorry, P., & Yung, A. (2012). Can receipt of a regular postcard reduce suicide-related behaviour in young help seekers? A randomized controlled trial. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 6(2), 145–152.

Saab, M. M., Murphy, M., Meehan, E., Dillon, C. B., O’Connell, S., Hegarty, J., Heffernan, S., Greaney, S., Kilty, C., & Goodwin, J. (2021). Suicide and self-harm risk assessment: a systematic review of prospective research. Archives of Suicide Research, 26(4), 1645–1665.

Tait, L., & Michail, M. (2014). Educational interventions for general practitioners to identify and manage depression as a suicide risk factor in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Systematic Reviews, 3(1), 1–7.

Vaiva, G., Berrouiguet, S., Walter, M., Courtet, P., Ducrocq, F., Jardon, V., Larsen, M. E., Cailhol, L., Godesense, C., & Couturier, C. (2018). Combining postcards, crisis cards, and telephone contact into a decision-making algorithm to reduce suicide reattempt: a randomized clinical trial of a personalized brief contact intervention. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(6), 2132.

Vaiva, G., Ducrocq, F., Meyer, P., Mathieu, D., Philippe, A., Libersa, C., & Goudemand, M. (2006). Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: Randomised controlled study. BMJ, 332(7552), 1241–1245.

Vaiva, G., Walter, M., Al Arab, A. S., Courtet, P., Bellivier, F., Demarty, A. L., Duhem, S., Ducrocq, F., Goldstein, P., & Libersa, C. (2011). ALGOS: The development of a randomized controlled trial testing a case management algorithm designed to reduce suicide risk among suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the “Center for Clinical Research Development, Al-Zahra Hospital,” Tabriz University of Medical sciences.

Funding

This study was funded, supervised, and reviewed by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences to number 68260.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by HA. All authors conceived, searched, extracted the relevant records, and synthesized the data that led to the manuscript or played an important role in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data or both. All authors contributed to the manuscript development and/or made substantive suggestions for revision. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by ethic committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences to number IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.1244.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Azizi, H., Fakhari, A., Farahbakhsh, M. et al. Prevention of Re-attempt Suicide Through Brief Contact Interventions: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of Randomized Controlled Trials. J of Prevention 44, 777–794 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-023-00747-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-023-00747-x