Abstract

In the United States (US), acceptance of adolescent vaccines, as measured by vaccine uptake in adolescents, is high amongst caregivers. However, this does not routinely extend to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. In the US state of Georgia, HPV vaccine coverage rates remain suboptimal, especially when compared to other adolescent vaccines. Our study aims to identify and examine caregivers’ motivators and barriers towards vaccinating their adolescents against HPV. We conducted nine focus groups with caregivers (n = 75) throughout the state. Using MAXQDA for thematic analysis, we identified common motivators and barriers related to adolescent HPV vaccine uptake amongst caregivers. Barriers reported include caregivers’ inability to develop a trusting patient-provider relationship and HPV vaccine message framing issues. Motivators reported include caregivers’ intrinsic need to protect their adolescents and trust their healthcare provider. Trust in healthcare providers was a key theme identified towards mitigating barriers and reinforcing motivators related to HPV vaccine acceptance and uptake. By improving patient-provider relationships throughout Georgia and streamlining digestible, representative vaccine information sharing across reputable sources, caregivers may become more receptive to vaccinating their adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the US state of Georgia, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine coverage remains subpar (73.1% initiate series of vaccines; 54.9% complete the series) and much lower than other adolescent vaccines’ coverage (90.8% Tdap; 95.2% MenACWY) (Pingali et al., 2021). While HPV vaccine coverage in this US state is higher than the global estimate of 12.2% (Spayne & Hesketh, 2021), it still trails the US national averages of 75.1% for series initiation and 58.6% for series completion (Pingali et al., 2021). National and geographically-specific studies have identified common barriers towards uptake, including caregiver perceptions of risk, cost, and a general distrust in the healthcare system, perpetuated by a lack of public knowledge and understanding of HPV vaccination, none of which were Georgia-specific (Dennison et al., 2019; Newman et al., 2018). Similarly, findings on HPV vaccine hesitance in the US can help support global efforts to utilize this vaccine to prevent cervical and other HPV-related cancers. Georgia’s growing diversity (i.e., 33% African-American; 10% foreign-born; 66.7% rural) requires state-specific research to improve contextual understanding and identify effective motivators and barriers to vaccination (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). The aim of this study was to assess barriers and motivators to HPV vaccination in the US state of Georgia, to document these factors in a more granular fashion than is typically done at the national level. Conducting this type of geographically localized assessment can help identify local barriers and motivators, and should be considered in the global context, to ensure that locally and culturally appropriate vaccine outreach efforts can be developed and implemented.

Methods

Our study is part of a larger project examining influences on HPV vaccination uptake in the state of Georgia. We used a subset of data from the parent study to examine motivators and barriers to HPV vaccination among caregivers of adolescents across the state. We conducted nine focus groups (FGs) with 75 caregivers in Georgia between April and July 2018.

The study obtained Emory Institutional Review Board approval. We provided participants with printed informed consent forms to review, sign, and return before participation. We collected demographic information regarding age, rural or urban home location, race, and sex. All research documents were uploaded to and kept on a password-protected, HIPAA-compliant server that restricted access to our research team. Participants received a $30 gift card.

Data Collection

We collaborated with immunization and regional cancer coalitions throughout Georgia to recruit our respondents, supported by a staff member from each coalition. We provided a recruitment flyer template, eligibility criteria, and potential FG dates to each assisting coalition. Recruiters from each coalition informed potential participants of the study and assessed participants’ eligibility before inviting them to a FG. Eligible participants included caregivers of at least one adolescent (9–17 years old) who lived in Georgia and were at least 18 years old. For this study, we defined a caregiver as anyone responsible for the decision-making for one or more adolescents’ health. Study participation required English fluency.

A moderator and a notetaker from our research team conducted all FGs in a private space convenient to participants. We used a moderator’s guide containing open-ended questions to elicit participant perceptions on HPV and the HPV vaccine (see Appendix A). Our research investigators collected demographic information during the FGs, through the guide (i.e., age and residency) and observation (i.e., race, ethnicity, and sex). FGs took 1.5 h on average to complete and included between six and twelve caregivers.

Data Analysis

Our research team transcribed FG audio recordings verbatim and de-identified them (Lahijani et al., 2021). All transcripts were uploaded into MAXQDA 2018 (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany) software and analyzed using thematic analysis. Our thematic analysis included code development, coder consistency, coding data, description of issues, and structured comparisons (Hennink et al., 2020).

Results

Participants

Demographics collected showed more African American and female participants, averaging 40 years old (see Table 1).

Introduction

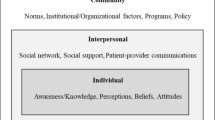

Our study found motivators and barriers centralized around three key themes; healthcare provider-patient trust, inconsistent messaging, and an intrinsic need to protect adolescents. This section presents a summary of these themes and representative quotes.

Barriers

Inconsistent Messaging

Participants reported using social media, WebMD, and Google when seeking HPV and HPV vaccine information regarding their adolescents. A common issue they presented was difficulty deciphering which sources presented factual information, as different sites provided different information: “That’s the problem though, you can keep on looking until you find the answer that you want, so how do you know what [is] real and what you want.”

Caregivers perceived the HPV vaccine as a relatively new vaccine which caused uptake hesitancy. Caregivers were wary of potential adverse reactions, particularly for adolescents with pre-existing or underlying health conditions: “…the vaccine is not for everybody. Everybody can’t tolerate it in their system, cause there has been problems with it (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020).”

All FGs referenced the MERCK© “Did You Know?” commercial when asked where they got information about HPV and the HPV vaccine. Some caregivers highlighted the inclusion of males as building an understanding of who is at risk and that these commercials remain an opportunity to expand media representation of other races and ethnicity: “The commercials are convincing though… I feel they don’t resonate with my culture.”

Most caregivers reported that they were unsure of the risks associated with HPV infection among male adolescents. The lack of messaging male adolescents received from their providers exacerbated this uncertainty: “…from what I saw on TV, it makes it seems so serious, and it is serious. Taking them to the doctor, they don’t put an emphasis on it [HPV vaccination] for boys.”

Inability to Develop a Trusting Provider-Patient Relationship

Many caregivers reported a distrust of healthcare providers and the medical system. Some speculated that a for-profit healthcare system might drive provider vaccine promotion rather than a patient-centric system: “Normally, [doctors] come down here to pay off their debts. I mean, they’re good while they’re here, but- you can’t blame them for doing that.”

Motivators

Protection for Adolescents

Some participants reported being motivated by concerns of unvaccinated adolescents infecting their adolescents. Some caregivers connected this to building herd immunity and social responsibility to vaccinate: “Like a lot of kids out there, a couple of kids who died because they were exposed to a child who didn’t have it. I like to think [it’s a] community concern.”

Caregivers reported that they could not rely on abstinence for adolescents as a protective method and that HPV vaccination could help mitigate transmission. A few further elaborated that future marital sexual relations and nonconsensual sexual activities (e.g., rape) can bypass abstinence practices and transmit HPV.

Trust in Healthcare Provider

For many caregivers, trust in provider recommendations depended on the longevity of their patient-provider relationship and provider-community reputation: “All my daughters have had the same pediatrician for the last 24 years… So that way they know everything, the history, that they’re familiar with my babies…”.

Discussion

As reviewed, we found barriers and motivators to HPV vaccination in adolescents. Participants reported a lack of clear, uniform, and ethnicity-representative messaging, which challenged full HPV and HPV vaccine understanding. Caregivers found that an abundance of indecipherable and contradictory HPV vaccine information was accessible, amplifying the importance of a health proxy or trusted provider to help them navigate past misinformation and biased sources.

Though the Food and Drug Administration approved and monitored the HPV vaccine, another barrier we found was that participants believed not enough post-market research had been conducted to understand how the vaccine interacts with different sub-populations (i.e., race, ethnicity, sex, and immunocompromised) (2018). Considering Georgia’s growing population and diversity, health promotion tactics will need to improve the inclusion of sub-populations in research, marketing, and information presentation to match demographics and empower caregivers to make informed decisions (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). The high provider turnover rates in rural areas where continuity of care remains limited may have exacerbated caregiver distrust in the healthcare system (Spleen et al., 2014).

The inconsistent messaging targeting male adolescents was a barrier. While the inclusion of male adolescents in HPV commercials promoted awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination in males, it was not heavily communicated by providers, leaving the urgency of HPV vaccination for male adolescents in question. Although HPV is untestable in males, Georgia’s high STI rates (Gonorrhea in 202 and Chlamydia in 644 per 100,000 tested) raised concern that these high transmission rates may infer high HPV prevalence (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2019). Males are more commonly at risk for oropharyngeal cancer, making up 82% of HPV-related male cancer cases nationally (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). The FDA recently approved HPV vaccination to prevent oropharyngeal cancers, presenting a considerable need for further development of marketing and communications to this population (Versaci, 2020).

Protecting their adolescent was seen as a motivator of getting the HPV vaccination. This intrinsic parental need seemed to underly all decision-making. For some, this meant vaccinating, although they may not have had all the information desired, preferring to be safe rather than sorry. Although a motivator, Gust et al. (2005) stressed that caregivers vaccinating without complete information might be prone to vacillating on this decision as vaccine safety concerns arise.

Despite Georgia’s conservative religio-political climate, caregivers acknowledged that faith in abstinence would not protect their adolescents and had limited control as HPV transmission is not exclusive to specific groups of people or forms of relationships. HPV vaccine campaigns may utilize this dialogue to provide relatable perceptions that de-stigmatize HPV vaccination.

Generational trust was a recurring marker for overall trust, influencing current beliefs about providers and the healthcare system. Considering Georgia’s highly rural nature, developing programs or policies to improve recruitment and retention of providers practicing in rural communities would be beneficial to building community-provider trust. Trust in healthcare providers persisted as a critical factor in HPV-vaccine acceptance and general vaccine confidence, permitting caregivers to believe their adolescent’s holistic well-being in mind while recommending the HPV vaccine. Jones et al. (2012) reported that the rural-background effect was successful in international contexts, providing grounds to support research or programs supporting Georgia’s rural provider retention efforts.

Limitations

Participants were primarily female and African American. For future research, increased diversity in sex and ethnicity in study participants may increase the generalizability of results within Georgia. Conducting future research in other relevant languages (e.g., Spanish and Korean) may improve representation of Georgia’s growing ethnic diversity. Due to the nature of qualitative research, our findings are not generalizable; however, they do provide sound footing for future research projects.

Public Health Implications

These findings suggest that building a trusting and communicative patient-provider relationship is likely to mitigate many of the barriers identified, allowing caregivers to place more value in provider recommendations, thus improving uptake of HPV vaccination. However, clear, uniform, and relatable information must be available to ensure caregivers’ buy-in to make a well-informed decision for their adolescents. The growing diversity in Georgia will require additional outreach and adaptation of health promotion campaigns to resonate with sub-populations, increase HPV vaccination message inclusivity, and improve perceived risk–benefit.

Data Availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the study are available by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). 2015-2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). How Many Cancers Are Linked with HPV Each Year? Retrieved July 20, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). 2019 STD Surveillance Report: State Ranking Tables. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2019/tables/2019-STD-Surveillance-State-Ranking-Tables.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Vaccine Safety: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine. Retrieved January 11, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/hpv-vaccine.html

Dennison, C., King, A. R., Rutledge, H., & Bednarczyk, R. A. (2019). HPV vaccine-related research, promotion and coordination in the State of Georgia: A systematic review. Journal of Community Health, 44(2), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0589-7

Gust, D., Brown, C., Sheedy, K., Hibbs, B., Weaver, D., & Nowak, G. (2005). Immunization attitudes and beliefs among parents: Beyond a dichotomous perspective. American Journal of Health Behavior, 29(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.29.1.7

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications.

Jones, M., Humphreys, J. S., & McGrail, M. R. (2012). Why does a rural background make medical students more likely to intend to work in rural areas and how consistent is the effect? A study of the rural background effect. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01242.x

Lahijani, A., King, A. R., Gullatte, M. M., Hennink, M., & Bednarczyk, R. A. (2021). HPV vaccine promotion: The church as an agent of change. Social Science & Medicine, 268, 113375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113375

Newman, P. A., Logie, C. H., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Baiden, P., Tepjan, S., Rubincam, C., Doukas, N., & Asey, F. (2018). Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. British Medical Journal Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206

Pingali, C., Yankey, D., Elam-Evans, L. D., Markowitz, L. E., Williams, C. L., Fredua, B., McNamara, L. A., Stokley, S., & Singleton, J. A. (2021). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(35), 1183–1190. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7035a1

Spayne, J., & Hesketh, T. (2021). Estimate of global human papillomavirus vaccination coverage: Analysis of countrylevel indicators. BMJ Open, e052016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052016

Spleen, A. M., Lengerich, E. J., Camacho, F. T., & Vanderpool, R. C. (2014). Health care avoidance among rural populations: Results from a nationally representative survey. The Journal of Rural Health, 30(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12032

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2018). FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old. Retrieved January 11, 2018, from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old

Versaci, M. B. (2020). FDA adds oropharyngeal cancer prevention as indication for HPV vaccine. American Dental Association. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://www.ada.org/publications/ada-news/2020/june/fda-adds-oropharyngeal-cancer-prevention-as-indication-for-hpv-vaccine

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere gratitude to focus group discussion participants involved in the research project and to the regional cancer coalitions and stakeholders who assisted in the organization for and planning of focus group discussions throughout the state. The Winship Cancer Institute’s Intervention Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Shared Resource (IDDI) supported revisions of the study tools used in data collection which we are immensely grateful for. Research reported in this ublication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute’s P30 Administrative Supplement to Designated Cancer Centers through Award Number P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) P30 Supplement funding program under Award Number P30CA138292. The National Cancer Institute had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, and decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RAB: Conceptualization, ARK: Administration, ARK: Methodology, WB: Formal analysis, ARK: Investigation, WB: Writing—original draft preparation, WB, ARK, RAB: Writing—review and editing, RAB: Funding acquisition, ARK, RAB: Resources, ARK, RAB: Validation, RAB: Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study obtained approval from the Emory Institutional Review Board (eIRB).

Informed Consent

Participants were provided informed consent forms (ICF) to review, which included permissions for audio recording. Written informed consent was required from all participants prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A: Moderator’s Guide

Appendix A: Moderator’s Guide

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bairu, W., King, A.R. & Bednarczyk, R.A. Caregivers of Adolescents’ Motivators and Barriers to Vaccinating Children Against Human Papillomavirus. J Primary Prevent 43, 407–420 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-022-00674-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-022-00674-3