Abstract

Mentoring continues to be a popular intervention for promoting positive youth development. However, the underlying mechanisms associated with sustainable and successful relationships remain largely unknown. Our study aimed to expand on previous literature by examining characteristics that have previously been linked to mentoring outcomes (e.g., authenticity, empathy), from a process-focused lens. We utilized post program satisfaction scores and interviews to examine the presence of each characteristic in a large sample of dyads (n = 144) as well as dyads’ levels of agreement or disagreement about aspects of the relationships. We found that high satisfaction dyads demonstrated greater congruity and detail in their descriptions of their relationships, whereas low satisfaction dyads were highly divergent and inconsistent in their descriptions. In addition, misattunement, a negative relational aspect, was the most powerful distinguisher between high and low satisfaction dyads, which provides support for mentors receiving attunement training in order to reduce instances of misattunement. Findings from this study highlight the importance of examining and assessing mentoring relationships from both the mentor and protégé perspectives, as a single perspective may not present a full picture of the relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nearly seven million youth will have a structured mentoring relationship by the age of 18 (MENTOR, 2014). Longer relationships are associated with increases in self-esteem, socio-emotional development, and academic performance for youth (Rhodes & DuBois, 2008). However, less than 38 % of mentoring relationships reach a year in duration (MENTOR, 2006). This is concerning as early termination of mentoring relationships can have detrimental effects for youth, such as decreased self-worth.

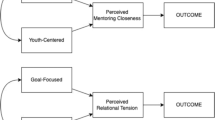

Deutsch and Spencer (2009) suggest that in order to fully assess and improve youth mentoring relationships, researchers must consider that mentoring programs operate at two levels, that of the program and that of the dyad. Researchers have identified a number of relationship level factors that are important for mentoring relationships to be effective. For example, Rhodes, Spencer, Keller, Liang, and Noam (2008) posits a close relationship between a mentor and protégé promotes positive outcomes. Further, Pryce (2012) holds that successful mentorships are associated with high quality relational experiences for the mentor and protégé, including the attunement and responsiveness of the mentor to the needs of the protégé. Whereas relational characteristics, such as the duration or quality of a relationship, have been extensively researched, relational processes, which refer to factors related to the active engagement of the mentor and the protégé with each other in ways that may foster or impede relational development, have been less empirically documented (Deutsch & Spencer, 2009). Identifying in more detail what relational processes, which are related to but not synonymous with relational characteristics, look like within mentoring dyads, could inform effective practices for mentors and protégés to promote sustainability and help us better understand why early termination occurs (Deutsch & Spencer, 2009).

Background

Much research at the dyadic level has focused on relational quality in order to understand what relational processes and characteristics contribute to successful mentoring relationships. For example, Spencer (2006) interviewed 12 female and 12 male mentor-protégé dyads, which had all been in relationships for at least 1 year, to develop a deeper understanding of the characteristics that are associated with successful mentorships. Four major themes emerged from the data which appeared to be associated with the success of these dyads mentorships: authenticity, or the extent to which each person felt the other was being real with them; empathy, or the mentors’ understanding problems from the protégés’ perspective; collaboration, or their descriptions of working together on skills; and companionship, or enjoying being with one another (Spencer, 2006). This study gave important insight into the relational processes that may be associated with successful mentorships. Indeed these four themes, authenticity, empathy, collaboration, and companionship, are noted throughout the literature as contributing to successful mentoring relationships (Rhodes et al., 2008).

More recently, Pryce (2012), examined how the therapeutic concept of attunement, how aware of and responsive a therapist is to a client’s needs, was related to relational experiences in mentoring. Highly attuned mentors in her study described relationships as give and take and tried to be flexible and creative when responding to nonverbal and verbal cues about their protégés’ preferences, concerns, and feelings. Moderately attuned mentors were typically inconsistent in their responses to their protégé’s needs and their flexibility varied. Minimally attuned mentors were very fixed and limited in their responsiveness to youth. Pryce found that attunement was “a consistently central element important to the success of and satisfaction within” (p. 300) the relationships she studied, suggesting its importance to relationship sustainability.

These studies have contributed greatly to the understanding of successful mentoring relationships. Yet researchers have highlighted that the effects of mentoring can still vary greatly depending on what actually occurs in relationships over time, i.e., that relationships are not static but develop through ongoing interactions between the mentor and protégé (Keller, 2007). As a result, in the last decade, many researchers have examined the development of mentoring relationships in order to understand the underlying relational processes that contribute to the building of successful mentoring relationships (Pryce & Keller, 2011). Karcher, Herrera, and Hansen (2010) examined the difference between relational (e.g., conversations about family) and goal-oriented (e.g., conversations about school) interactions in relationships and found that while both contributed to the overall relationship quality, relational conversations contributed more to the relational quality. The researchers conducted further analyses with the same data examining who in the relationship decided what the pair would do together (e.g., unilateral or collaborative). They found that mentors rated the relationship quality higher when decisions were made collaboratively with their protégés (Karcher, Herrera, & Hansen, 2010). These findings highlight the importance of understanding interactions in mentoring relationships.

Working from a life-course perspective, Pryce and Keller (2012) found that despite the individualized nature of mentoring relationships, the relationships in their study still grouped into four distinct patterns over time: progressive (characterized by smooth improvement in strength and quality), plateaued (characterized by promising starts, but ultimately quality and depth of interactions tapered off), stagnant (characterized by challenging starts and failure to deepen over time), and breakthrough (characterized by challenging starts but ultimately a turning point shifted the relationships towards higher quality interactions). Their findings demonstrate the importance of supporting mentoring pairs throughout their relationships as well as providing insight into factors that might indicate which path the relationship might be on. Other factors that might impact the trajectory of relationships are: the qualities of verbal and nonverbal communication, nature and degree of conflict, and the protégés’ level of satisfaction (Hinde, 1997).

Importantly, some researchers have suggested that girls and boys may differ in terms of their experiences of mentoring relationships. For example, whereas girls’ mentoring relationships have been found to last longer than boys, girls report being less satisfied than boys in shorter-term mentoring relationships (Rhodes, Lowe, Litchfield, & Walsh-Samp, 2008). Some have noted that because mothers often refer girls to mentoring because of issues in the mother–daughter relationship, girls may have more difficulty forming a close relationship with a mentor (Bogat & Liang, 2005), suggesting that girls may benefit from more relationally-based approaches to mentoring (Liang & Grossman, 2007).

This study aims to expand on previous literature by examining characteristics that have previously been linked to mentoring outcomes (e.g., authenticity, empathy), from a process-focused lens. We do so with a larger sample than is typical for process-oriented studies and with a focus on girls, whose relational development with mentors may reflect particular issues, as noted above. Further, we seek to specifically compare the relational perspectives of mentors and protégés to help us better understand these processes from both perspectives. Thus, we aim to examine the presence of each characteristic in a large sample of dyads as well as the dyads’ levels of agreement or disagreement about aspects of the relationships.

Present Study

This study uses 2 years of data from the Young Women Leaders Program (YWLP), a combined one-on-one and group mentoring program, to assess dyadic-level factors that are associated with mentoring relationships’ success or failure. The YWLP utilizes one on one mentoring, between college women and seventh grade girls, with targeted group activities that address issues such as identity, scholastic achievement, social aggression, and health decision-making. A previous study that used the YWLP survey data reported that mentors and protégés conveyed high levels of satisfaction with their mentoring experiences and that the program had a higher than average rate of retention, with 75 % of the dyads maintaining relationships beyond the end of the school year (Deutsch, Wiggins, Henneberger, & Lawrence, 2012). Yet, the factors that underlie the program’s high retention rate and participants’ satisfaction with relationships are unknown. This study uses the post-program surveys and interviews to assess the content of and consistency in mentors’ and protégés’ descriptions of their relationships (i.e., the beginning, development, quality, and content) and the relationship of those factors to relational satisfaction. We examine dyads’ interviews in relation to each other to assess what factors mentors and protégés identify as being important to their relationships and the extent to which mentors’ and protégés’ descriptions of their relationships, and what was important to their development, aligns. The following questions guide the study: What relational processes are evident in mentors’ and protégés’ descriptions of their relationships? In what ways do mentors’ and protégés’ descriptions of their relationships overlap or diverge? How, if at all, is that overlap or divergence associated with protégés’ satisfaction with their mentoring relationships?

Method

The Young Women Leaders Program (YWLP)

The YWLP utilizes one-on-one mentoring with targeted group activities to build the competencies of middle school girls (Lawrence, Levy, Martin, & Strother-Taylor, 2008). The program is aimed at females because the literature has suggested that girls are at more risk than boys for negative experiences such as sexual victimization and disordered eating during adolescence (Littleton & Ollendick, 2003; Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001). Seventh grade girls identified by their schools as being at risk for poor social, academic, and/or emotional outcomes are paired with college women for one academic school year. Each mentoring pair meets individually at least 4 h per month and attends weekly, 2-h group meetings at the protégé’s school; the meetings include group and one-on-one activities that address issues such as academics, body image, relational aggression, and problem-solving (Lawrence, Sovik-Johnston, Roberts, & Thorndike, 2009). This study focuses on the flagship YWLP site, which includes four middle schools.

Participants

In the spring of each of the two program years, the research team invited all participants who consented to be part of YWLP research to be interviewed about their experiences in the program. Of the 148 protégés who were invited, 113 completed the interview. There were no significant differences on demographic characteristics of those who chose to be interviewed versus those who did not. Of the 142 mentors who were invited, 130 completed the interview. For this study, we selected only those interviews for which both members of the dyad had completed an interview. Thus, participants include 144 YWLP participants (n = 72 mentors; n = 72 protégés). The protégés identified as 43 % African American, 31 % Caucasian, 5 % Hispanic, 11 % Other, 9 % Multiracial. The mentors identified as 21 % African American, 70 % Caucasian, and 9 % Asian American. The average ages of mentors and protégés were 20.5 and 13, respectively, and all were female. Of the 72 mentors, 23 % reported having previous YWLP experience.

Measures

Rhodes’ (2002) Youth-Mentor Relationship Questionnaire was used to assess protégé satisfaction with their relationships. The 15-item scale includes four subscales: helping cope, not dissatisfied, not unhappy, and trust not broken, with reliabilities that range from α.74 to α.85 (Rhodes, 2002). Each subscale was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not true at all” to “very true.” Sample items include “I wish my Big Sister were different” and “My Big Sister had lots of good ideas about how to solve a problem.” The negative items were reverse coded so that a higher score indicated greater relationship quality.

A team of researchers developed the interview protocol in consultation with YWLP program staff.Footnote 1 The interviews aimed at gaining deeper insight to mentor/protégé experiences with the YWLP and their mentoring relationships. The interview protocol included questions about the interviewee’s general experiences in the YWLP, her one-on-one relationship, her experiences in the group, her mentor’s/protégé’s experiences with the group, and changes that she (and her protégé for mentors) made over the course of the year.

Procedure and Data Collection

After participating in YWLP for 1 year, protégés completed the Youth-Mentor Relationship Questionnaire (2005) as part of a year-end survey taken at their schools either on computers or with pen and paper. Trained faculty, postdoctoral, and doctoral level researchers, all female and from a range of ethnic and racial backgrounds, conducted interviews with protégés at their schools during lunch or after-school and with mentors at their university in a private office. Interviews generally ranged from 20 to 50 min. The interview team conducted fidelity checks and addressed any problems that arose during weekly research team meetings. Interviewers digitally recorded the interviews, which were transcribed by a professional transcription company.

Analyses

The research team used NVivo software to code all mentor and protégé interviews. The team originally coded data into large themes based on the research questions guiding the over-arching study (e.g., connection, one-on-one relationship, etc.). Researchers developed those initial codes through an iterative process of literature reviews, reviewing the data, and research team discussions. Researchers then finalized a set of codes and went through a process of developing inter-coder reliability. Once reliability was reached, researchers individually coded interview data. For this study, the first author, who was not part of the initial research team, reviewed all the data from the paired dyads (n = 72 mentors and 72 protégés) that had been coded at the theme “one-on-one relationship.” The first author coded the data based on initial themes (e.g., authenticity, empathy) developed from Rhodes’ (2002) mentoring model and Spencer’s (2006) relational processes codes. The first and second authors reviewed the data together and identified additional, emergent themes, including attunement, a concept identified by Pryce (2012), and misattunement, a concept theoretically linked to but also distinct from Pryce’s construct of attunement (and which will be described in results, below; See Table 1 for a complete description of codes). Of note is that whereas misattunement was the only negative code that we examined in the data, this was not a purposeful strategy. Rather, misattunement was the only negative code to emerge from the data and, therefore, because of its singular presence in the interview data, became the sole negative code in the analysis. In addition, the first author engaged in peer debriefing of the codes with peers who were not involved in the study to enhance trustworthiness of analyses and reduce bias of the researchers.

After coding of the interview data was complete, we conducted descriptive analyses of the Youth-Mentor Relationship Questionnaire scores in SPSS to identify three groups of protégés: those who were less satisfied with their relationships (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), those who were highly satisfied with their relationships (i.e., 1 SD above the mean), and those who were satisfied (i.e., within 1 SD of the mean). Of the 72 dyads, 15 dyads (20.8 %) were identified as having high protégé relational satisfaction, 45 dyads (62.5 %) were identified as having average protégé relational satisfaction, and 12 dyads (16.7 %) were identified as having low protégé relational satisfaction. Relational satisfaction grouping (low, medium or high) was then uploaded into NVivo as a descriptor for each protégé’s, and her mentor’s, interviews. We then conducted comparative analyses of theme frequency and content (i.e., description and nature of the relationship) in high and low satisfaction dyads. We began by examining in what percentage of interviews each theme was present in low versus high satisfaction dyads (e.g., attunement was reported in 69 % of interviews from high satisfaction dyads and in 50 % of interviews from low satisfaction dyads). We then compared what percentage of coded interview excerpts for each code, termed references, were provided by mentors and protégés (e.g., of the excerpts coded at attunement in high satisfaction dyads, 54 % were excerpts from mentor interviews and 46 % were excerpts from protégé interviews; see Table 2).

Findings

Overall, positive characteristics of relationships (i.e., attunement, authenticity, collaboration, companionship, empathy, and identification) were reported about equally across high and low satisfaction dyads. These processes appear across the majority of the interviews in both categories (see left side of Table 2 which reports on the percentages of the interviews in which these processes were mentioned at least once). Of these, attunement and authenticity were the most prevalent. Companionship, identification and collaboration were the next most prevalent, appearing in half or just over half of interviews. Empathy appeared in around a quarter of interviews, slightly more for the low satisfaction relationships (see Table 1 for definitions of all codes).

Although positive aspects of relationships were present across both high and low satisfaction dyads, there were differences between high and low satisfaction relationships in terms of how closely mentors’ and protégés’ descriptions of their relationships were aligned. This is apparent when comparing the prevalence of the positive codes in mentor versus protégé interviews for high and low satisfaction dyads (see right side of Table 2, which reports what percentage of the excerpts coded at a particular theme were from mentors versus protégés in high and low satisfaction dyads). In high satisfaction dyads, mentors and protégés both reported positive processes in relationships. In low satisfaction relationships, on the other hand, positive characteristics in relationships were mentioned by mentors far more frequently than by protégés (see Table 2). For example, whereas half of the excerpts coded for empathy in high satisfaction dyads came from mentor interviews and half came from protégé interviews, 100 % of excerpts coded at empathy in low satisfaction dyads came from mentor interviews. This pattern was present across all the positive codes in the low satisfaction relationships. Thus, there appeared to be a mismatch in the low quality relationships between how the mentors and protégés viewed the relationships, with the mentors viewing more positive characteristics in the relationships than the protégés. We found more support for this finding by examining interviews of dyads together, directly comparing how the mentors and protégés each talked about their relationships.

Overlap

High satisfaction dyads had greater instances of mentors and protégés who both reported positive relational characteristics, alignment in their descriptions of events, and descriptions of their relationships. The following examples are all from high satisfaction dyads. When asked for a general description of their relationship, one mentor replied, “We have a good relationship. We hang out whenever we can. We like to do the same things…she’s really into cooking and I enjoy cooking so most of the time we like bake stuff or just go to the grocery store and like cook a meal…” Her protégé echoed, “She likes a lot of the same things I do…and she’s really fun to hang out with. We like cooking and playing sports and stuff like that.” In this example, from a dyad where both parties were satisfied with the relationship, both the mentor and protégé spontaneously expressed feeling companionship and identification with one another as well as provided the same, specific example of how they often spent their time.

In addition to overlaps in their descriptions of the relationship itself, there were many instances of mentors and protégés describing similar social, emotional, and behavioral development throughout their relationship. For example, one mentor described what she hoped her protégé learned from her: “I just kind of hope she knows that…by all the attention I gave her…I’m still interested in you, you’re so great, kind of by having an older girl think that it might boost her self-esteem.” Indeed her protégé felt she gained in that area because of her mentor, “She’s made me like feel better and more confident about myself…. she is like showing me, oh that outfit looks nice and you have a really great personality, and that sort of stuff.” In another example, a mentor describes the social and behavioral growth she saw in her protégé stemming from her own interactions with her:

But she’s kind of got that when she says something and she can be hurtful but not realize she’s being hurtful and sometimes I mean I can handle it so it’s not that big of a deal to me and I finally told her at the last group she said something and I was like you know when you say comments like that like I understand what you’re saying but you don’t realize how hurtful you’re being.

Her protégé also discussed this when describing how and why she changed over the course of their relationship:

Oh, because [mentor] was always telling me like how what I say does like hurt people’s feelings…and so I – it made me realize like it’s not just like certain people that feel that way. It’s just like a lot of people. And that it’s not them feeling mean, being mean to me. It’s something I have to work on.

In both of these examples, mentors and protégés independently report similar ways in which specific interactions in their relationship positively impacted the protégé’s development. Sometimes, dyads descriptions where not as concrete as the previous examples but instead provided different views which, when examined together, complemented one another and provided a fuller picture of what contributed to the high satisfaction in the relationship. For example, one mentor generally described how she handled her concern for her protégé, “…she never had anyone she could go to… I always wanted her to feel that you know she can come talk to me, that I care about her… I just wanted to make sure that she knew that I was always there for her.” Her protégé said of their relationship, “I noticed whenever I called, she always answered, and it was just a lot, like…there’s just something about it. It’s like having somebody at home versus having nobody at home. It’s just a good thing to have because it’s just beautiful. It just makes me happy….” In this case, the mentor provides a more general description of how she was attuned to her protégé’s needs and attempted to respond to those needs in the relationship. The protégé provided a concrete detail of how her mentor made her feel that she was always there for her (i.e., she always answered when I called), indicating alignment between the mentor’s goals and views and the protégé’s experience of the relationship. In another example, a mentor described the event that made her feel closer to her protégé:

…with [protégé] the turning point that I can remember was actually when we were in class and I think we had a discussion about …sexual assault I feel like a lot earlier than most of the other groups had….we were walking around the school and she told me about her past and being you know I guess assaulted.

The protégé on the other hand did not disclose that information to the interviewer. Instead, she described what her mentor had done that allowed her to trust her enough to share such personal information in their relationship:

Because we’d talk about what’s been going on with like what happened in her life that’s happening with me right now. And it just you know felt as though I could trust her because she was sharing these details with me about. She feels as though she can trust me with these details in her life, so I can trust her with some of my details.

Here, mutual sharing of information helped build trust in the relationship over time. While the mentor recalled a specific incidence of the protégé sharing a significant personal fact, she may not have been aware how her own sharing of personal stories may have laid the foundation for that exchange, as suggested by the protégé. Examining the codes in both mentor and protégé interviews provided more insight into how high satisfaction dyads in this study describe their relationships. Conversely, low satisfaction dyads’ descriptions of their relationships were often full of contradictions of relational characteristics or events.

Divergence

Further analysis of the low satisfaction dyads revealed that often only one person described the relationship positively and the other often directly contradicted that description. All of the following examples are from low satisfaction dyads. Frequently, the mentor was the one reporting positive relational characteristics. For example, one mentor said, “And I think that that was the best part of our relationship that neither of us…had to feel like we had to act a certain way around each other. We were more just comfortable and honest to a certain degree you know. I think that aspect was what I appreciated the most too.” However, her protégé suggested that there should be less one-on-one time in the program, “That we have like less time really because like I mean I didn’t really like my big sister that much.” Where the mentor’s description would have indicated a more positive and potentially deeper relationship, the protégé’s description calls into question the validity of the mentor’s statement.

Dyads also differed in their perceptions of interactions. One mentor said, “Yeah it was the first time I drove her because I went to pick her up on the city bus before and we came to campus and studied and that was the first time we did something fun.” But her protégé’s description of relationship differed, “I mean we just go places that she likes. We just went to go wash her car 1 day. Like if she’s in school studying and I want to do something, there’s no way—I couldn’t.” It is clear that this dyad lacked understanding of each other’s interests.

Divergence also revealed communication issues. One mentor described her protégé as challenging because “…she would sometimes do things on purpose that she did know would make me upset because she didn’t know how else to tell me she didn’t feel happy…. With my [protégé] she’ll like purposefully run away and hide and attempt to not talk to me.” However, the interview with the protégé revealed the she felt ignored, “If I had told her about something that I got that was fun that happened at school today she would just like totally blow it off and just like start talking about something completely random…Yeah, she didn’t listen to me like whatsoever.” In another example, a mentor expressed challenges in her relationship with her protégé:

…it was frustrating to find things to do with her and to spend time with her because she just wasn’t very open to join different activities and it was all you know she would always say yes to going out to eat you know that sort of thing… So and then it was hard yeah I guess it was just hard for me to talk to her about my life or like what difficulties I was having or what was going really well in my life because you know she never directly asked and I think I’m just the type of person that kind of needs that.

However, her protégé felt they spoke a lot of personal issues:

Like we share and we talk a lot. So like I used to tell her a lot of stuff about myself like what happened at school and my family. So the fact that we shared stuff…. Because she told me like one of her secrets. So I told her like – she told me stuff about herself first and then I told her about me. And then she was like, nobody else knew it. So.

Another area that reflected this divergence between mentor and protégé experiences or perspectives was the prevalence of attunement in low satisfied dyads and the emergent theme of misattunement in both high and low satisfaction dyads. Whereas empathy reflects an understanding of the other person’s perspective, attunement reflects a more active embodiment of that, translating that understanding into an active response. Attunement encompasses, but then enacts, empathy. Likewise, misattunement is not just the absence of positive processes, but reflects more active misunderstanding or rigidity in how the mentor and protégé deal with one another. Misattunement was characterized by inflexibility in responding to relational difficulties, and a lack of self-reflection on the part of the mentor or protégé in terms of why a conflict or challenge existed. It reflects not only a lack of empathy, although it often includes that, but also a more active lack of willingness to change one’s behavior or adjust to the needs of the other person in the relationship. Rather than a recognition and response to an issue, misattunement often presented itself as one person trying to “make” the other person see things their way. There were distinct differences between mentors and protégés in their reports of both constructs that differentiated high from low satisfaction dyads.

With regards to attunement, mentors and protégés in high satisfaction dyads reported experiences of attunement in their relationships about equally. However there was divergence in reports of attunement between mentors and mentees in low satisfaction dyads, in which 75 % of mentors but only 25 % of protégés described their relationships as reflecting attunement. It is not surprising that protégés in relationships characterized by low protégé satisfaction reported low levels of attunement in their relationships. But the fact that some mentors in those relationships were experiencing the relationships as more attuned than the protégés, suggests that it is not just the absence of positive processes, but a mismatch in actual views of the relationship that may influence relational quality and success.

Misattunement was seen in 93 % of the interviews from low satisfaction dyads, and in only 18 % of those from high satisfaction dyads. Yet in addition to this divergence between low and high satisfaction dyads, misattunement also revealed an interesting divergence between mentors and protégés. In low satisfaction dyads, both mentors and protégés reported experiences of misattunement in their relationships, and the prevalence of references coded for misattunement across mentor versus protégé interviews was close to equally split. Yet in high satisfaction dyads 100 % of the instances of misattunement came from the mentor interviews, suggesting that in those relationships the protégé’s overall satisfaction with the relationship overrode the potential negative impacts of misattunement.

Agree to Disagree

Finally, our analysis revealed that agreement in descriptions of relationships does not necessarily mean the relationship is on track to be successful. Several low satisfaction dyads agreed about negative characteristics or events in their relationships, but differed in what they viewed as the root of the problem. For example, this dyad both expressed problems with not being able to spend time with one another:

Mentor: I think that it like went through phases because when we didn’t get to spend time together I think she felt like that was a sleight to her from me, like I didn’t want to spend time with her. But at the same time I was like I’m worn out of leaving you answering machine messages and trying to get a hold of you. So I think there was like some phases of like both of us being kind of like disgruntled with each other…

Protégé: …we never had time to hang out really because uh she would like call but we’d try to set up something and then she never like showed up really or came late or said she was doing something. So she never really came. And then like um I really didn’t think of many plans to do and I don’t know like every time I’d wanted to do something, one day she was always busy that day.

Despite their high agreement on a main source of contention in their relationship, both felt the other was at fault for failing to see one another. Another pair had similar issues:

Mentor: Probably keeping up like a constant stream of communication with my little sister. Because some weeks she’ll just want to talk to me all the time and other weeks she won’t answer the phone at all. And or email, she won’t like text me back or anything. So trying to be there for her but not being able to talk to her all the time was difficult.

Protégé: …We only texted like maybe once a week. We never talked on the phone unless I was trying to help plan stuff, ‘cause my friend and her big sister, like that’s the only time we ever talked on the phone and like she lied on that paper and said we talked on the phone like three, four times a week, no we never texted three or four times a week, and like I only got to spend time with her, like on the weekends, like three times the whole year.

In this example, both sides agreed that communication was difficult but disagreed about the effort put forth from each other.

Discussion

Mentoring continues to be a popular intervention for promoting positive youth development. However, the underlying mechanisms associated with sustainable and successful relationships remain largely unknown. This study aimed to understand relational processes associated with the development of a close mentor-protégé relationship from the perspectives of both parties.

Our findings lend support to Rhodes (2002) mentoring model and Spencer’s (2006) relational processes. Authenticity, companionship, collaboration, and identification were found to be associated with the development of meaningful mentorships in our study as well. Though initial analyses suggested that these themes were comparably present in both high and low satisfaction dyads, further comparative analyses revealed several insights into examining and supporting mentoring relationships.

Our analysis of overlap in descriptions found that high satisfaction dyads were able to demonstrate greater congruity in their general descriptions of their relationships, descriptions of specific events, and more equal contributions of positive characteristics. Conversely, low satisfaction dyads had high levels of divergence in their descriptions of their relationships, often directly contradicting one another. In these cases, one person in the dyad, often the mentor, reported more positive aspects of the relationship than the other person. This resulted in overall counts of positive themes across and high and low relationships that looked similar on the surface, but which masked discrepancy between mentors and protégés. This distinction highlights the importance of examining both the mentor and protégé perspectives in a mentoring relationship, as one perspective can tell an incomplete story. Relationships are not a characteristic or product of any one person, and cannot be fully assessed as such. Rather, dyadic approaches to analysis, which have been suggested within the family and marriage literature (e.g., Maguire, 1999), are important to consider. Considering both the congruity and content of each perspective is also key. As demonstrated in our final category, dyads can agree on problems but their descriptions of the problems might differ. Furthermore, our results lend support for utilizing multiple methods (quantitative post program satisfaction scores as well as qualitative interviews) as a source of triangulation for reliability of analyses as well as a means for deeper understanding of the different aspects of relationships.

The mismatch between mentor and protégé reports, especially of positive processes in low satisfaction dyads, suggests that mentoring programs should be carefully attuned to the potentially differential experiences of mentors and protégés. Replying on the report of only the mentor, for example, as an indicator of the status of a relationship may lead programs to miss relationships that may be in danger of failing. Spencer’s (2007) research on mentoring relationships that failed revealed a number of warning signs of unsuccessful relationships. Our work expands on that by highlighting the divergent perspectives of mentors and protégés concerning the relationships themselves as a potential red flag for programs of dyads that may benefit from additional support.

The power of negative processes was also highlighted by our findings. Rhodes, Reddy, Roffman, and Grossman (2005) found that protégé reports of negative aspects of their mentoring relationships were more powerful predictors of relationship termination than the positive aspects of relationships. The sharp contrast in the prevalence of misattunement between low and high satisfaction dyads in our sample provides further support for the power of negative relational aspects to drive relational experiences. This suggests that mentoring programs should be particularly alert for reports of negative experiences from mentors or protégés and should consider offering additional support to such pairs.

It is clear from our findings that mentors and protégés are able to recall specific events and general interactions that contribute to their satisfaction, or dissatisfaction with their relationship. Future research should consider assessing both mentors’ and protégés’ relational perspectives throughout their relationship (i.e., from beginning to end; as example can be seen in Pryce & Keller, 2012) in order to examine if the perspectives reflected in our study are evident throughout the relationship and, if so, how whether patterns exist that may help predict which relationships will be more or less successful over time. In addition, our findings suggest that mentoring programs may want to attend to both mentor and protégé reports of their experiences at various points during the relationship and that program staff may want to provide extra support to pairs in which mentor and protégé reports of positive aspects of the relationship diverge.

Limitations

This study is limited in its generalizability in that it only included mentors and protégés from a single mentoring program. In addition, although the overall study had a high response rate for interviews, for this study we only included data where we had interviews from both the mentor and protégé, limiting the sample’s generalizability to the larger program population. Furthermore, the program was all-female. Thus, we do not know whether these relational processes would appear in the same way, or at all, in male mentoring pairs. In addition, the program relied on self-report by mentors and protégés at the end of the mentoring program. As noted above, it is not therefore surprising that dyads in which protégés reported less satisfaction were higher in negative aspects and that protégés in such relationships reported fewer positive aspects. Assessing these processes over time would be an important next step for researchers. Triangulation based on either observations of the pairs or on a third party observer of the pairs (such as their group facilitator) would have provided additional support for or potentially nuances to, the findings.

Conclusion

Ultimately, findings from this study highlight the importance of examining mentoring relationships from both the mentor and protégé perspectives, as a single perspective may not present a full picture of the relationship. As others have pointed out (e.g., Deutsch & Spencer, 2009), relationships are more than the sum of two different people’s perspectives. They are a separate entity that requires a different level of measurement and a different lens for analysis. If we are to truly help mentors and protégés build strong mentoring relationships, we must conduct research that helps identify the uniquely relational factors that contribute to relationship sustainability and success. Understanding how mentors’ and protégés’ views together influence relational success lends important implications for both research and practice.

Notes

Interview protocol is available upon request from the authors.

References

Bogat, G. A., & Liang, B. (2005). Gender in mentoring relationships. In D. L. DuBois & M. J. Karcher (Eds.), Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Deutsch, N. L., & Spencer, R. (2009). Capturing the magic: Assessing the quality of youth mentoring relationships. New Directions for Youth Development, 2009(121), 47–70. doi:10.1002/yd.296.

Deutsch, N. L., Wiggins, A. Y., Henneberger, A. K., & Lawrence, E. C. (2012). Combining mentoring with structured group activities: A potential after-school contect for fostering relationships between girls and mentors. Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(1), 44–76. doi:10.1177/0272431612458037.

Hinde, R. A. (1997). Relationships: A dialectical perspective. Hove: Psychology Press.

Karcher, M. J., Herrera, C., & Hansen, K. (2010). “I dunno, what do you want to do?”: Testing a framework to guide mentor training and activity selection. In M. J. Karcher & M. J. Nakkula (Eds.), Play, talk, learn: Promising practices in youth mentoring (pp. 51–69). New Directions for Youth Development, No. 26.

Keller, T. E. (2007). Theoretical approaches and methodological issues involving youth mentoring relationships. In T. D. Allen & L. T. Eby (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach (pp. 23–47). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Lawrence, E. C., Levy, M., Martin, N., & Strother-Taylor, J. (2008). One-on-one and group mentoring: An integrated approach (pp. 1–5). Folsom, CA: Mentoring Resource Center. Retrieved from http://www.edmentoring.org/pubs/ywlp_study.pdf.

Lawrence, E. C., Sovik-Johnston, A., Roberts, K., & Thorndike, A. (2009). The young women leaders program mentor handbook (6th ed.). Charlottesville, VA: Young Women Leaders Program.

Liang, B., & Grossman, J. M. (2007). Diversity and youth mentoring relationships. In T. D. Allen & L. T. Eby (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach (pp. 239–258). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Littleton, H. L., & Ollendick, T. (2003). Negative body image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(1), 51–66. doi:10.1023/A:1022266017046.

Maguire, M. C. (1999). Treating the dyad as the unit of analysis: A primer on three analytic approaches. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 213–223. doi:10.2307/353895.

MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership. (2006). Mentoring in America 2005: A snapshot of the current state of mentoring. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Pryce, J. (2012). Mentor attunement: An approach to successful school-based mentoring relationships. Child Adolescent Social Work, 29, 285–305. doi:10.1007/s10560-012-0260-6.

Pryce, J., & Keller, T. (2011). An investigation of interpersonal tone within school-based mentoring relationships. Youth and Society, 45(1), 98–116. doi:10.1177/0044118X11409068.

Pryce, J., & Keller, T. (2012). An investigation of volunteer-student relationship trajectories within school-based youth mentoring programs. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(2), 228–248. doi:10.1002/jcop.20487.

Rhodes, J. E. (2002). Stand by me: The risks and rewards of mentoring today’s youth. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Rhodes, J. E., & DuBois, D. L. (2008). Mentoring relationships and programs for youth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 254–258. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00585.x.

Rhodes, J. E., Lowe, S. R., Litchfield, L., & Walsh-Samp, K. (2008). The role of gender in youth mentoring relationship formation and duration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(2), 183–192. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.09.005.

Rhodes, J., Reddy, R., Roffman, J., & Grossman, J. B. (2005). Promoting successful youth mentoring relationships: A preliminary screening questionnaire. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(2), 147–167. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-1849-8.

Rhodes, J. E., Spencer, R., Keller, T. E., Liang, B., & Noam, G. (2008). A model for influencing of mentoring relationships on youth development. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(6), 691–707. doi:10.1002/jcop.20124.

Silverman, J., Raj, A., Mucci, L., & Hathaway, J. (2001). Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(5), 572–579. doi:10.1001/jama.286.5.572.

Spencer, R. (2006). Understanding the mentoring process between adolescents and adults. Youth & Society, 37(3), 287–315. doi:10.1177/0743558405278263.

Spencer, R. (2007). “It’s Not What I Expected” A qualitative study of youth mentoring relationship failures. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(4), 331–354. doi:10.1177/0743558407301915.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant #R305B090002 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0450-7.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Varga, S.M., Deutsch, N.L. Revealing Both Sides of the Story: A Comparative Analysis of Mentors and Protégés Relational Perspectives. J Primary Prevent 37, 449–465 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0443-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0443-6