Abstract

Purpose To determine the prevalence and predictors of psychological distress among injured and ill workers and their mental health service use. Methods Cross-sectional national survey of adults with work-related musculoskeletal or mental health conditions, accepted workers’ compensation claims and at least 1 day off work. Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler-6 scale. Mental health service use was measured using self-report. Results A total of 3755 workers were included in the study (Musculoskeletal disorder = 3160; Mental health condition = 595). Of these, 1034 (27.5%) and 525 (14.0%) recorded moderate and severe psychological distress, respectively. Multivariate ordinal logistic regression revealed that being off work, poor general health, low work ability, financial stress, stressful interactions with healthcare providers and having diagnosed mental health conditions had the strongest associations with presence of psychological distress. Of the subgroup with musculoskeletal disorders and psychological distress (N = 1197), 325 (27.2%) reported accessing mental health services in the past four weeks. Severe psychological distress, being off work, worse general health and requiring support during claim were most strongly associated with greater odds of service use. Conclusions The prevalence of psychological distress among workers’ compensation claimants is high. Most workers with musculoskeletal disorders and psychological distress do not access mental health services. Screening, early intervention and referral programs may reduce the prevalence and impact of psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Workers’ compensation is the primary means via which governments in many industrialised nations provide treatment, rehabilitation and financial support to people with work-related injury or disease. In 2016 more than 136 million jobs in the United States were covered by state or federal workers’ compensation schemes, and these schemes paid combined estimated benefits of $61.9 billion. Of this an estimated $31.1 billion was for medical benefits, and a further $30.8 billion was paid in wage replacement direct to injured workers [1]. In Australia in 2014/15 the nine major workers’ compensation schemes funded $1.9 billion in healthcare and treatment to 242,000 injured workers through public and private healthcare systems [2]. In the same year the Australian schemes paid a further $4.5 billion in wage replacement.

Physical injury can have substantial psychological impacts [3]. Internationally, studies have shown that depressive symptoms are common following workplace musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) [4, 5], and more likely in people with occupational injury [6]. One study of injured Canadian workers reported a 12 month cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms of 50% [7]. Depressive symptoms have also been shown to delay return to work and complicate recovery in people with MSD [5]. Conversely, interventions that address the psychological consequences of MSD can speed up return to work [8].

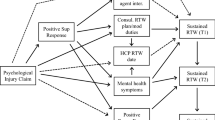

A range of personal, social and administrative factors may contribute to the onset and course of mental health conditions (MHC) in injured workers. Stressful interactions with workers’ compensation insurers can have negative psychological consequences [9] and have been associated with elevated levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms and lower reported quality of life 6 years after physical injury [10]. Early contact with an injured worker and workplace supervisor reactions to injury predict workers’ perception of fairness, which in turn is associated with worker attitude to return to work and mental health [11]. Understanding the predictors of psychological distress, and their relative impact, is important for service planning and treatment response.

Workers’ compensation funding for medical treatment is typically limited to the condition for which an insurer has accepted liability. Treatment for comorbid conditions that can complicate recovery, or those occurring subsequent to the compensable condition, may not be funded [12]. In the only study to date focusing on this topic, as few as a third of Canadian workers’ compensation claimants with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms over the first year following MSD onset receive mental health treatment [7]. Combined, MSD and MHC account for 47% of the Australian national non-fatal burden of disease, and occur predominantly in people of working age [13]. They are also the most common (MSD) condition leading to workers’ compensation claims and the most costly per accepted claim (MHC) [14]. Australia’s workers’ compensation schemes have near universal and national coverage of the working population, and thus workers’ compensation settings provide an opportunity for population-level intervention in common and burdensome health conditions.

This study aimed to determine the prevalence and predictors of psychological distress in workers’ compensation claimants with MSD and MHC. A second aim was to determine the prevalence of mental health service use among workers with MSD and psychological distress, and examine the personal, social and claim factors associated with service use.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Australia has a labour force of 12.3 million [15], of which approximately 94% are covered by one of the nation’s eleven workers’ compensation schemes [16]. These schemes provide wage replacement and healthcare benefits for workers with a temporary or permanent incapacity to work due to injury acquired in the course of employment [2]. The National Return to Work Survey (NRTWS) is a biennial computer assisted telephone interview of workers with an accepted workers’ compensation claim [17]. The survey is commissioned by Safe Work Australia and enrols participants whose workers’ compensation claim was submitted within the past 24 months. The 2018 iteration of the survey included participants from all of the nation’s workers’ compensation authorities, with the exception of the Defence and Veterans compensation scheme and South Australia, which combined account for less than 10% of covered workers. A randomly selected sample was taken from the eligible population of workers who had submitted a claim between 1 February 2016 and 31 January 2018, who had taken at least one day off work, were aged 18 or older, and had either open or closed workers’ compensation claims.

Procedures

Workers meeting inclusion criteria were identified from administrative claims data by state, territory and Commonwealth workers’ compensation authorities. Contact details were provided to an independent survey company, which sent a letter to the potential participant describing the survey and providing options to opt-out of participating. Workers who did not opt-out were contacted via telephone and informed consent was sought. If consent was obtained the survey was administered. The survey participation rate in those workers contacted via telephone was 67.7% [18]. Data on the opt-out rate in response to the initial postal letter was not available. Survey administration required approximately 25 min. Survey content is designed to address the four domains of work disability as described in the Sherbrooke model of work disability [19], which include items relating to the worker such as demographic information and validated measures of physical and mental health, the workplace, the workers’ compensation scheme and healthcare [20]. Survey responses are linked at a case level to workers’ compensation claim processing data including nature of compensable condition, key event dates, state/territory of claim and self-insured status.

This study received ethics approval from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee on 27 September 2017 (–Project 11329).

Outcomes

Two outcomes were defined for this study. First, psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler 6 questionnaire [21]. Responses on the six item Kessler questionnaire were summed and participants were categorised as having low (score of 6 to 10), moderate (11 to 18) or severe (19 to 30) psychological distress as per established scoring algorithms [22, 23]. Second, participants who had accessed specialist mental health services were identified through responses to the following question “Which of the following healthcare providers have you seen for treatment of your work-related injury or illness?” Participants selecting a psychologist or psychiatrist were categorised having received specialist mental health treatment.

Co-variates

A range of variables were included as co-variates on the basis that they assessed factors related to the worker, the workplace, the workers’ compensation scheme and healthcare, have been shown previously to be significant predictors of recovery from work-related injury and disease [24, 25] and met statistical criterion for inclusion in multivariable models described in the data analysis section. Age was categorised into three groups: 18 to 35, 36 to 50 and 51 to 80 years. Nature of compensable injury or disease was categorised using the Type of Occurrence Classification Scheme (TOOCS) version 3.1 as MSD (Categories B, F and H) or MHC (Category I) [26]. Industry was based on a modification of the Australian New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification categories (Online Resource 1) [27]. General health at time of interview was collected on a 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) scale and dichotomised into poor/fair/good and very good/excellent categories. Level of financial stress at time of interview was given on a scale from 1 (not at all stressed) to 10 (as stressed as can be) and dichotomised into high (≥ 7) and low (< 7) financial stress [28]. Concerns about submitting a claim and distributive justice measures were each derived from a series of four questions (Online Resource 1). For each case, the average response across the four questions was calculated and then individuals were categorised into high, moderate and low. Working status was dichotomised as yes (currently working in paid employment) and no (not currently working), as were responses to questions on the presence of pain in the past week and whether the worker required support to navigate the compensation scheme. Workers reporting diagnoses of anxiety or depression were categorised as having one condition, or both. Workers were asked if their job was psychologically demanding with responses categorised into high (strongly agree), moderate (agree) and low (neutral/disagree/strongly disagree). Workers rated their ability to work today on a scale from 1 (completely unable to work) to 10 (work ability at its best) and the response was dichotomised into high (≥ 8) and low (< 8), based on the median response. Workers also nominated their main source of income, rated whether their contact with the workplace return to work coordinator was stressful and how much contact they had with their claim organisation.

Data Analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the sample given that outcomes were categorical. Associations between predictors and psychological distress were assessed using ordinal regression. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) represents the odds of an individual worker having a greater amount of psychological distress compared to the reference category for each predictor, which was defined as the category with the greatest proportion of the sample. Logistic regression was used to assess associations between predictors and mental health service usage. Given the near ubiquity of mental health service use among workers with MHC claims, this was restricted to workers with moderate or severe psychological distress and who had a compensation claim for a MSD. In this model the AOR represents the odds of a worker having seen a mental health professional compared to the reference category. Multivariable models were constructed to identify factors associated with outcomes. Each potential predictor was assessed for a univariate association with each outcome using a p value of 0.20 as a threshold. Covariates that reached this threshold were then combined in a multivariable model and retained if significant at p < 0.05. Interactions between variables and injury type (MSD or MHC) were tested and retained if significant.

There was a small percentage of missing data (< 10%) on multiple variables. Multiple imputation was performed on these variables in twenty iterations of sequential imputation using chained equations. In the psychological distress model 532 cases (14.17%) had at least one of 13 variables imputed and in the mental health service use model 197 cases (16.46%) had at least one of seven variables imputed (Online Resource 2). All analyses were carried out using Stata 15.1 [29].

Results

Psychological Distress

A total of 4602 workers completed the 2018 iteration of the National RTW survey. Of these, 4100 (89.1%) workers had accepted claims for MSD or MHC, and of these 3755 (81.6% of the total sample) also completed the Kessler 6 questionnaire and were included in the study. In 1559 (41.6%) included cases Kessler-6 scores indicated psychological distress including 1034 (27.5%) cases of moderate distress and a further 525 (14.0%) cases of severe distress.

There were notable differences in psychological distress category by demographic, injury/condition, health service, compensation scheme and workplace variables. Psychological distress was significantly higher among workers with low work ability and MHC (AOR 7.04, 95% CI 3.67–13.51), in those with MHCs and poor general health (AOR 6.72, 95% CI 4.23–10.67) a diagnosis of both depression and anxiety in workers with MSD (AOR 3.94, 95% CI 3.07–5.05) and low work ability in workers with MSD (AOR 3.12, 95% CI 2.56–3.79). Other significant associations with psychological distress were with financial stress (AOR 2.63, 95% CI 2.23–3.11), poor general health in workers with MSD (AOR 2.41, 95% CI 1.92–3.02), workers reporting a high level of concern about their workplace response to their claim (AOR 2.31, 95% CI 1.88–2.83), and those who reported stressful interactions with healthcare providers (AOR 2.16, 95% CI 1.74–2.69). Smaller but statistically significant effects were observed for other variables including age, current working status, pain, job stress, requiring support to navigate the claims process, stressful workplace interactions, and main source of income (Table 1).

Mental Health Service Use

Of included workers with MHC claims, 91.1% (n = 541) reported accessing specialist mental health services, including 94.5% (n = 342) of those with moderate or severe psychological distress. In contrast, of workers with MSD and either moderate or severe psychological distress (N = 1197), only 20.5% (n = 170) of workers moderate distress and 42.3% (n = 155) of workers with severe psychological distress reported accessing mental health services (Fig. 1).

Variables with the strongest association with having accessed mental health services among workers with MSD included working in the education and training industry (AOR 2.12, 95% CI 1.12–4.01), having severe psychological distress (AOR 2.06, 95% CI: 1.53–2.78), and being off work (AOR 2.00, 95% CI 1.48–2.69). Smaller but statistically significant associations were observed for workers from the public administration and safety industry, with poor general health, requiring support to navigate the claims process, being in conflict with and having a lot of contact with the claims organisation, and experiencing stressful healthcare provider interactions (Table 2).

Discussion

This national study of 3755 workers with accepted MSD or MHC compensation claims identified a high rate of mental health complaints, with two in every five survey respondents reporting moderate or severe psychological distress as assessed by the Kessler 6 scale. The proportion of respondents with severe psychological distress (14.0%) is more than three times the national average of 4.0% for people of working age [30]. More concerning is the proportion of respondents with severe psychological distress among those who were not working (37.3%), nine times the national average for people of working age, and among those with claims for mental illness (26.7%) at approximately six times the national average. Musculoskeletal disorders are the most common condition leading to workers’ compensation claims in Australia and in similar international workers’ compensation schemes such as those in the United States and Canada [31]. This study demonstrates that 37.9% of workers with MSD surveyed within 2 years of their workers’ compensation claim report moderate or severe psychological distress.

Several of the factors associated with the presence of psychological distress are modifiable. For example both the workplace response to the injury and the insurance claims process can be modified [10, 32]. These represent opportunities for policy and practice changes to enhance the response to work-related injury and disease, and to reduce the prevalence and impact of psychological distress among injured workers. Other non-modifiable factors may provide valuable flags indicating increased risk of psychological distress, and represent opportunities for practitioners, employers and insurance providers to develop risk screening approaches.

One clear opportunity for reducing psychological distress is provision of appropriate mental health care. In this study nearly all workers with a workers’ compensation claim for a MHC reported receiving treatment from a mental health professional. In contrast, only a quarter (27.2%) of injured workers with MSD, who also had moderate and severe psychological distress reported a mental health professional among their healthcare team. Factors associated with mental health service use overlapped with those for the presence of psychological distress, but additionally included being in conflict with, and having more contact with, the workers’ compensation insurer. Prior qualitative studies suggest both that insurance claims processes can exacerbate mental health concerns, and that workers with MHCs have greater exposure to insurance claims processes [9].

This study presents data suggesting the need for screening and early intervention programs to identify and support injured workers with mental health problems. Delivery of such programs in workers’ compensation is challenging. Prior studies have reported multiple barriers to effective healthcare provision in workers’ compensation schemes including administrative barriers [33], unique clinical challenges in injured worker cohorts [34], and knowledge barriers such as lack of understanding of insurance processes among healthcare providers [12]. Psychological service provision has been reported as being particularly problematic due to the impact of complex insurance claim administration and adversarial dispute processes on the mental health of claimants [35]. Decisions to fund healthcare are made by workers’ compensation insurers on the basis that they are ‘reasonable and necessary’ to support the return to work of an injured worker. Programs that provide specialist mental health care to larger proportions of MSD claims may be perceived by insurers as impacting the affordability of workers compensation insurance. Despite these challenges, the rates of mental health service use reported in the current study appear higher than that observed in Australians with diagnosed mental illness of 12 months or longer duration, in whom approximately 9% access psychiatry and 14% psychology services [36].

To our knowledge, this is the first substantive study reporting the prevalence of psychological distress among an Australian workers’ compensation cohort, and supplements a single smaller Canadian study. Study limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the survey which limits causal inference, and self-reported estimates of service use. Strengths include the large sample size encompassing multiple workers’ compensation schemes providing coverage for > 90% of the labor force, the use of validated measurement instruments across a range of domains of relevance to worker health. Further examination of psychological complaints and mental health service use amongst workers’ compensation claimants is required. The study was conducted in a nation with workers’ compensation arrangements that are similar to those in Canada and the United States, but quite different to those in other jurisdictions. This both limits the generalisability to settings with similar compensation arrangements, and provides impetus to explore insurance claims management experience in settings with different arrangements. We have previously observed significant differences in return to work outcomes by state or territory of workers’ compensation claim [25]. Our analysis did not observe statistically significant relationships between jurisdiction and either psychological distress or mental health service use, and thus this potential predictor was not included in our multivariable models.

Findings demonstrate that psychological distress is common among workers’ compensation claimants, including those with MSD claims. Further it appears that the provision of mental health service delivery is inadequate for those with MSD claims and psychological distress, with the majority of such workers not reporting specialist mental health care. Programs for the early identification of workers experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, psychological distress should be routine in workers’ compensation given the high prevalence and adverse impacts. Provision of effective healthcare and other support for those with psychological distress is also recommended, and may require changes to current policy and practice. Effective early identification programs and service delivery both represent important unmet needs in this population.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Safe Work Australia but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Safe Work Australia and the Australian state, territory and Commonwealth workers compensation regulatory authorities.

References

McLaren CF, Baldwin ML, Boden LI. Workers’ compensation: benefits, costs and coverage (2016 data). Washington, DC: National Academy of Social Insurance; 2018. p. 100.

Safe Work Australia. Comparison of workers’ compensation arrangements in Australia and New Zealand, 2016. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2017.

Craig A, Tran Y, Guest R, Gopinath B, Jagnoor J, Bryant RA, et al. Psychological impact of injuries sustained in motor vehicle crashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011993.

Dersh J, Gatchel RJ, Mayer T, Polatin R, Temple OR. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(10):1156–1162.

Franche RL, Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin C, Bultmann U, et al. Course, diagnosis and treatment of depressive symptomatology in workers following a workplace injury: a prospective cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(8):534–546.

Kim J. Depression as a psychosocial consequence of occupational injury in the US working population: findings from the medical expenditure panel survey. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:303.

Carnide N, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin C, Severin CN, et al. Course of depressive symptoms followinng a workplace injury: a 12 month follow up update. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26:204–215.

Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings PA, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related and mental health conditions: an update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:1–15.

Kilgour E, Kosny A, McKenzie D, Collie A. Interactions between injured workers and insurers in workers’ compensation systems: a systematic review of qualitative research literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):160–181.

Grant GM, O’Donnell ML, Spittal MJ, Creamer M, Studdert DM. Relationship between stressfulness of claiming for injury compensation and long-term recovery: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):446–453.

Hepburn CG, Kelloway EK, Franche RL. Early employer response to workplace injury: what injured workers perceive as fair and why these perceptions matter. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):409–420.

Kilgour E, Kosny A, McKenzie D, Collie A. Healing or harming? Healthcare provider interactions with injured workers and insurers in workers’ compensation systems. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):220–239.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study. Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2011.

Safe Work Australia. Australian workers’ compensation statistics 2015–16. Australia: Canberra; 2018.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6202.0—Labour Force, Australia, May 2018.

Lane TJ, Collie A, Hassani-Mahmooei B. Work-related injury and illness in Australia, 2004 to 2014. What is the incidence of work-related conditions and their impact on time lost from work by state and territory, age, gender and injury type? Melbourne, Australia: Institute for Safety Compensation and Recovery Research; 2016. Contract No.: 118-0616-R02.

Social Research Centre. Return to Work Survey: 2016 Summary Research Report (Australia and New Zealand). Australia: Safe Work Australia, Melbourne; 2017. p. 59.

Social Research Centre. Return to Work Survey, 2017/18: Headline Measures Report. Melbourne: Safe Work Australia; 2018.

Costa-Black K. Work disability models: past and present. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, editors. Handbook of work disability: prevention and management. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2014. p. 71–93.

Social Research Centre. National Return to Work Survey 2018 Questionnaire. Melbourne: Safe Work Australia; 2018.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189.

Prochaska JJ, Sung HY, Max W, Shi Y, Ong M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(2):88–97.

Smith PM, Black O, Keegel T, Collie A. Are the predictors of work absence following a work-related injury similar for musculoskeletal and mental health claims? J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(1):79–88.

Collie A, Lane TJ, Hassani-Mahmooei B, Thompson J, McLeod C. Does time off work after injury vary by jurisdiction? A comparative study of eight Australian workers’ compensation systems. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010910.

Safety Australian, Council Compensation. Type of occurrence classification system, 3rd edition (revision 1). Canberra: Australian Government; 2008.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian and New Zealand standard industrial classification (ANZSIC), 2006 (Revision 2.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2016.

Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Jinhee K, Drentea P. In Charge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation. J Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17(1):34–50.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical software: release 15.1. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey 2014–15. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2015.

Macpherson RA, Lane TJ, Collie A, McLeod CB. Age, sex, and the changing disability burden of compensated work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Canada and Australia. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):758.

Elbers NA, Collie A, Hogg-Johnson S, Lippel K, Lockwood K, Cameron ID. Differences in perceived fairness and health outcomes in two injury compensation systems: a comparative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:658.

Mazza D, Brijnath B, Singh N, Kosny A, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. General practitioners and sickness certification for injury in Australia. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:100.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Singh N, Kosny A, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. Mental health claims management and return to work: qualitative insights from Melbourne, Australia. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):766–776.

Kilgour E, Kosny A, Akkermans AJ, Collie A. Procedural justice and the use of independent medical evaluations in workers’ compensation. Psychol Injury Law. 2015;8(2):153–168.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2007. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2007.

Funding

This project was funded by Safe Work Australia and Worksafe Victoria through a grant to the first named author (AC). This publication uses data supplied by Safe Work Australia and has been compiled in collaboration with Australian state, territory and Commonwealth workers’ compensation regulators. The views expressed are the authors and are not necessarily the views of Safe Work Australia or the state, territory and Commonwealth workers’ compensation regulators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. LS conducted the analysis. All authors reviewed the data analysis, contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee approval Project Number 11329) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collie, A., Sheehan, L., Lane, T.J. et al. Psychological Distress in Workers’ Compensation Claimants: Prevalence, Predictors and Mental Health Service Use. J Occup Rehabil 30, 194–202 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09862-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09862-1