Abstract

Failure to comply with therapeutic treatments implies negative repercussions for the patient's quality of life, their social environment, and health system. The use of information and communication technologies, especially mobile applications, has favored the increase in global therapeutic adherence figures. The objective of this study is to characterize the use of mobile applications as a strategy to increase therapeutic adherence in adults. A systematic literature review in Web of Science and Scopus was performed following the Preferred Information elements for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis. Information such as: the year of publication, the study population, the medical conditions of the participants, the main characteristics or functionalities of the mobile applications, and the methods or tools used to measure treatment adherence were extracted from each included article. The risk of bias was assessed. Twelve randomized controlled trials (RCTs), published in English from 1996 to May 2021, were included. Chronic diseases have been mostly addressed through interventions with mobile applications. The most reported functions of mobile applications were reminders, educational modules, two-way communication, and games. Tools such as: "Morisky Medication Adherence Scale of eight items"; "Medication adherence questionnaire"; "Self-reported adherence"; among others, were used to evaluate and report the treatment adherence. In conclusion, including treatment interventions using mobile applications in clinical practice has proven to be beneficial to improve therapeutic adherence. However, it is necessary to develop high-quality clinical trials (size and duration) to generalize results and justify their use in conventional health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines therapeutic adherence as the rate at which an individual’s behavior in relation to medicine use, consuming a healthy diet and changing their lifestyle corresponds to the instructions agreed by a health professional and a patient [1]. Adherence differs from compliance in the active role played by the patient and the professionals throughout the entire process [2]. Nonadherence to treatment has become an issue in clinical care, which transcends disease; a study estimates that 20–50% of patients do not follow the treatment plan appropriately [3]; a meta-analysis reported the rate of therapeutic nonadherence, on average, was 24.8%, yet it depended on the seriousness of the pathology [4]. The WHO estimates that in developed countries therapeutic adherence to long-term therapies or therapies for chronic conditions, on average, is 50% [1]. Furthermore, it has been discovered that nonadherence concerns not only patients but also the healthcare system in terms of high costs, clinical complications, hospital readmissions and loss of human talent [5]. Poor adherence is responsible for 5 and 10% of hospital admissions, 2.5 million medical emergencies and 125,000 deaths in the United States every year [6].

At present, digital health and the information and communication technologies (ITCs) for health care are used to promote equal and universal access to health services [7]. The WHO acknowledges in its recently published Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025, that ICTs are innovation elements and facilitators for ensuring health intervention all over the world [8]. ICTs, in particular mobile health (mHealth), are widely used for remote care, treatment of chronic conditions, communication between health professionals and patients and monitoring of intervention plans [9,10,11,12]. Considering this, some systematic reviews discovered that the use of applications for smartphones (APPs) has the advantages of accessibility, lower costs and a variety of functions to treat conditions in the short-term and the long-term. Additionally, other mHealth interventions such as the short message service (SMS) and electronic pill boxes can also have a positive effect on pharmacological adherence [13, 14]. However, there is scant evidence of the use of APPs effectively improving therapeutic adherence under different health conditions.

The main purpose of this systematic review is to describe the APP functions that proved a positive effect on therapeutic adherence, as well as to describe the tools used for assessing adherence and the results thereof. Secondarily, it is to figure out chronicity of APP interventions and to sort them into pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

Methods

Literature review

A systematic literature review was conducted from various databases following the items in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [15]. The electronic databases included were the following: Web of Science and Scopus, for studies published between 1996 and May 2021. Moreover, a manual search was carried out among the lists of references of the articles included. The search strategy included combinations of terms related to the use of technologies in health -Telemedicine OR Telehealth OR eHealth OR mHealth-, mobile devices -Mobile Applications OR Smartphone-, adherence to treatment -Adherence OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance”- and adult population -Adult OR Aged OR Elder. MeSH terms, key words and thesaurus were used for reducing the possibility to miss any relevant studies. The search was restricted to publications in English and Spanish.

Study selection

Following the first search, the selection of studies was made in three phases. First, duplicates of publications were removed by Zotero® software Version 5.0.89 (Center for History and New Media at George Mason University). Second, the titles and summaries were examined according to the following inclusion criteria: studies reporting on relations between the factors of interest –adherence to treatment and mobile applications-, publications written in English and Spanish, articles published in magazines cataloged and reviewed in pairs. Third, the full texts of potentially relevant studies were thoroughly reviewed considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria for final analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria in the review were: adult participants (≥ 18 years), a treatment developed with mobile applications, control groups had to undergo conventional treatment -not using any APP. The experimental and control groups were both provided with data on adherence to treatment, the study design was randomized controlled trial (RCT), the articles were published in English or Spanish and, finally, the results were classified into: types of treatments, major features of the mobile application or tools used for measuring adherence to treatment.

Studies were excluded for they included participants aged under 18, conventional treatments developed for health professionals or results limited to cost utility and cost effectiveness. Also, because they reported adherence to interventions in health promotion and prevention not considered as treatment plans. Articles issued as summaries, posters and billboard posters for lectures were dismissed as well.

Data collection

Data were collected by means of a customized matrix which included the features of the studies –year and country of the study, study design, sample size, health condition of the population, participants’ features, name of the mobile application, APP features; scales or tools used for measuring adherence to treatment.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias helped to assess validity of the results of the study and analyze whether they show reliable evidence for interpretation [16]. Two proofreaders assessed each article here individually. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion between the authors until they reached an agreement. It is considered that the studies’ risk of bias is not noticeably clear for an item, as far as the main article did not provide with enough information for proofreaders to be categorical about a high or low risk of bias.

Results

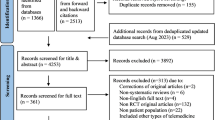

The first search returned 3,025 potentially eligible studies. After removing duplicate, 1,202 studies were examined by their titles and summaries. 63 were considered eligible and their whole contents were read for evaluation purposes. Out of these, 12 studies reported eligible data for inclusion of the analysis [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The selection process and the reasons for exclusion are stated in flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Study features

Most of the studies were conducted in the last four years (2018–2021) over diverse areas: Asia (41.66%), Europe (33.3%) and North America (25%). RCT sample size varied from 36 to 480, with a median of 117.5. The main health conditions of the patients who received APP-based treatment were: coronary heart disease (25%), cancer (17%), hypertension (17%) and diabetes (17%), among others. Monitoring intervals of APP interventions varied from 12 months (17%) to 0.75 months –3 weeks- (8%) (Table 1).

Characteristics of the Mobile Applications

The studies defined the features of the APP used for intervention to increase therapeutic adherence. 67% of the studies (n = 8) reported on the reminder system, which allows to set a calendar [18, 28] and send alarms to patients at scheduled times to remind them to take their medication and of upcoming appointments, among others [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. 58% (n = 7) referred to automated education, which is based on providing the user with information about the condition, symptoms, medicine use, importance of following the treatment, side effects of medication, psycho-social and confrontation strategies [17, 18, 20,21,22,23, 26]. Almost 17% (n = 2) of the studies mentioned the frequent asked questions [18, 22]. The function related to uploading evidence was reported by 8% of the studies –this is about sending a picture of the medicine in the patient’s hand through the APP [19]. Furthermore, a study combined intervention and bidirectional communication functions, by means of emails, text messages or video calls [17]. To conclude, one study used an APP for intervention through a game. The game included training options, recommendations to promote physical activity, tracking and treatment monitoring [24]. Information about “Patients use of the mobile applications” in Supplementary Table.

Tools for Measuring Adherence to Treatment

Two out of the twelve studies measured adherence according to the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale [20, 22]. The rest of the studies used other tools: Medication adherence questionnaire [23]; Self-reported adherence [17]; Oral Chemotherapy Adherence Scale [18]; Adherence starts with knowledge-12 [25]; Medication adherence rating scale [26]; Voil’s Medication Nonadherence Rating Scale [27]. Some of the remaining studies reported on adherence based on the number of medicines taken [19, 28], whereas others took into consideration the APP usage data [21, 24] (Table 2).

Risk of Bias

The quality of twelve RCTs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] was summarized in a table of risk of bias (Table 3). Ten studies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, 26, 27] reported on the generation of random sequences. A study mentioned that participants where blinded [17]. Additionally, four studies remarked that a perfect blinding was not possible [18, 21, 22, 25]. A study did not refer to whether the results were influenced by the blindness [26] and six studies introduced partial data thereof [17,18,19,20,21, 27, 28].

Discussion

This review served for identification of a series of APP functions which showed a positive effect on therapeutic adherence. Automated educational functions were the most used in all applications resulting in favorable changes towards therapeutic adherence. This has been supported by several studies proving that those educational interventions help behavioral change by improving communication between patients and health professionals, which increases therapeutic adherence as well [29, 30]. The second APP function in rank was the medication reminder. A number of studies have considered this strategy with the aim of ensuring compliance of pharmacological treatment [31, 32]. However, there are some limitations regarding the use of reminders: people may become dependent on them for taking their medicines, which could lead to failure because of error in the APP, Internet access issues, low battery or inattention. In light of this, APP intervention shall include behavioral strategies to encourage patient autonomy and self-management of treatments, causing the APP to be simply a support tool.

There was also evidence on why an APP designed to improve therapeutic adherence should consider including other functions such as a calendar [to remember start and end dates of treatments, appointments, tests and therapies], bidirectional communication with health professionals and games offering feedback about the knowledge acquired. Finally, it is worth highlighting that a dynamic, interactive and creative presentation of the information guarantees better comprehension among people with low literacy levels and bridges the access gap in basic communication.

As for the tools for measuring adherence to treatment, they were of diverse types and most of them were validated psychometric tools, which enabled the identification of patterns of adherence after detecting the profiles of those patients likely to adhere. Nevertheless, it is important to always remember that the outcomes rely on the patient’s subjectivity and honesty. Therefore, they should be matched according to the results from medical tests to say whether the findings are trustworthy. Furthermore, four studies made use of other indirect methods such as the percentage of medicines taken over a period, the total amount of medicines yet to be taken or data usage indicators. The method based on the percentage has been validated and it is considered as an objective and reliable method [33, 34]. Nonetheless, this method does not allow to identify possible reasons for treatment incompliance or withdrawal. Last, choosing the right measurement method in essential to ensure trustworthy results, since the decision shall be made based on the health condition, the type of intervention and the behavior subject to assessment. Besides, the method shall avoid the overestimation and underestimation of the results.

The analysis of the measurement instruments showed that therapeutic adherence improves in direct proportion to factors like intervals between monitoring and the type of intervention. These two factors are matched to statistically significant changes regarding the increase in adherence among the experimental groups. The first one applies to intervals between monitoring: the more patients use the APP, the better adherence to therapy. This is in relation to a study about the consolidation of new habits and the automation of new conducts, which reports that the average time necessary to reach 95% of automaticity is 66 days, ranging from 18 to 254 days [35]. This suggests that APP intervention shall be consistent for people to achieve their automaticity limit with respect to the expected behavior. The second factor concerns pharmacological interventions, as they proved to have greater significance in comparison with the non-pharmacological ones. It is easier to improve medication adherence than achieving a health-related behavioral change. Marilyn Rice acknowledges that providing people with information on the positive or negative effects of a particular behavior is not enough to cause a change; motivation plays a vital role in enabling that change, which is crucial for the success of the intervention [36]. Hence, APPs shall include attractive, significant contents –based on the context- that motivate patients to use them in a conscious consistent way.

To conclude, at the time of defining the diverse health conditions subject to APP intervention, the vast majority turned out to be chronic diseases. It is acknowledged that patients suffering from chronic disease need a treatment based on highly accurate information, education, management and communication proceedings and therefore APPs are considered as a suitable strategy for favoring communication channels, allowing information to be exchanged in an easy, quick, accessible and comprehensible manner. Two types of intervention were considered: pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention. This implies that APPs have distinctive features for improving therapeutic adherence. Regarding the pharmacological interventions, 100% of them featured the medication reminder function, 62.5% included educational contents and 25% offered bidirectional communication. Clinical care guidebooks recommend using APPs with reminders to reduce involuntary nonadherence [31, 32]. As for the non-pharmacological interventions, 100% of the APPs included educational contents and cognitive, physical and emotional training. According to Becker et al. [37], non-pharmacological treatments require strategies to change habits and conducts connected to patients’ self-care processes. The abovementioned APP functions may be beneficial for caregivers, relatives and health professionals, since the entire social environment improves when patients act in a health-conscious, aware and consistent manner.

Limitations

The use of APPs is an innovation strategy for many patients; however, a limitation may exist with regards to usage. The number of elders using smartphones may be small due to low digital literacy levels, which prevents them from using this kind of mobile tools appropriately. This could also retard the development of new digital strategies, as old adults are the users in need of most of these interventions.

Conclusion

Most of the studies reviewed reported that, in comparison to conventional interventions to increase therapeutical adherence, the strategy involving the use of mobile applications showed a noticeable, and in some cases statistically significant, improvement. The results suggest that the use of mobile applications may be a choice in the professional practice in the future for monitoring treatment, increasing therapeutical adherence, broadening knowledge of the specific condition and improving patient-health professional communication. The mobile application functions that contributed to achieve these goals were: medication reminders, educational items, bidirectional communication, calendars and games. The application of APP interventions to clinical care has proved to be beneficial to improve therapeutic adherence. Nevertheless, it is necessary to develop high-quality clinical trials to generalize about the results and justify its introduction to the conventional health services.

References

World Health Organization (2004) Adherence to the long-term treatments: tests for the action. Institutional Repository for Information Sharing - Pan American Health Organization. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/41182

Ramos Morales LE (2015) Adherence to treatment in chronic diseases. Rev Cubana Angiol Cir Vasc 16(2):175-189.

Ventura Carmona MJ, Ruiz-Muelle A, López Rodríguez MM (2020) Adherence to treatment in chronic patients: hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Therapeía: estudios y propuestas en Ciencias de la Salud 11:17–43.

DiMatteo MR (2004) Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Medical care 42(3):200–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9

Ortega Cerda JJ, Sánchez Herrera D, Rodríguez Miranda OA, Ortega Legaspi JM (2018) Therapeutic adherence: a health care problem. Acta médica Grupo Ángeles 16(3):226-232.

Bosworth HB, Granger BB, Mendys P, Brindis R, Burkholder R, Czajkowski SM, Daniel JG, Ekman I, Ho M, Johnson M, Kimmel SE, Liu LZ, Musaus J, Shrank WH, Whalley Buono E, Weiss K, Granger CB (2011) Medication adherence: a call for action. American heart journal 162(3):412–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.007

World Health Organization (2016) mHealth: use of mobile wireless technologies for public health Executive Board EB139/8 139th session. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB139/B139_8-en.pdf

World Health Organization (2021) Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025 https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf?sfvrsn=f112ede5_75

Brown EL, Ruggiano N, Li J, Clarke PJ, Kay ES, Hristidis V (2019) Smartphone-Based Health Technologies for Dementia Care: Opportunities, Challenges, and Current Practices. Journal of applied gerontology: the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society 38(1):73–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817723088

Pham L, Harris T, Varosanec M, Morgan V, Kosa P, Bielekova B (2021) Smartphone-based symbol-digit modalities test reliably captures brain damage in multiple sclerosis. NPJ digital medicine 4(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00401-y

Qi S, Sun Y, Yin P, Zhang H, Wang, Z (2021) Mobile Phone Use and Cognitive Impairment among Elderly Chinese: A National Cross-Sectional Survey Study. International journal of environmental research and public health 18(11):5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115695

Désormeaux-Moreau M, Michel CM, Vallières M, Racine M, Poulin-Paquet M, Lacasse D, Gionet P, Genereux M, Lachiheb W, Provencher V (2021) Mobile Apps to Support Family Caregivers of People With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias in Managing Disruptive Behaviors: Qualitative Study With Users Embedded in a Scoping Review. JMIR aging 4(2):e21808. https://doi.org/10.2196/21808

Nglazi MD, Bekker LG, Wood R, Hussey GD, Wiysonge CS (2013) Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review. BMC infectious diseases 13:566. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-566

Peng Y, Wang H, Fang Q, Xie L, Shu L, Sun W, Liu Q (2020) Effectiveness of Mobile Applications on Medication Adherence in Adults with Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 26(4):550–561. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.4.550

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Alarcón Palacios M, Ojeda Gómez RC, Ticse Huaricancha IL, Lucy I, Cajachagua Hilario K. Critical analysis of randomized clinical trials: The risk of bias. Rev Estomatológica Hered 25(4):304–8.

Puig J, Echeverría P, Lluch T, Herms J, Estany C, Bonjoch A, Ornelas A, París D, Loste C, Sarquella M, Clotet B, Negredo E (2021) A Specific Mobile Health Application for Older HIV-Infected Patients: Usability and Patient's Satisfaction. Telemedicine journal and e-health: the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 27(4):432–440. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0098

Karaaslan-Eşer A, Ayaz-Alkaya, S (2021) The effect of a mobile application on treatment adherence and symptom management in patients using oral anticancer agents: A randomized controlled trial. European journal of oncology nursing: the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society 52:101969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101969

Riegel B, Stephens-Shields A, Jaskowiak-Barr A, Daus M, Kimmel SE (2020) A behavioral economics-based telehealth intervention to improve aspirin adherence following hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 29(5):513–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4988

Gong K, Yan YL, Li Y, Du J, Wang J, Han Y, Zou Y, Zou XY, Huang H, She Q, APP Study Group (2020) Mobile health applications for the management of primary hypertension: A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Medicine 99(16):e19715. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019715

Hauser-Ulrich S, Künzli H, Meier-Peterhans D, Kowatsch T (2020) A Smartphone-Based Health Care Chatbot to Promote Self-Management of Chronic Pain (SELMA): Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8(4):e15806. https://doi.org/10.2196/15806

Boyd AD, Ndukwe CI, Dileep A, Everin OF, Yao Y, Welland B, Field J, Baumann M, Flores JD Jr, Shroff A, Groo V, Dickens C, Doukky R, Francis R, Peacock G, Wilkie DJ (2020) Elderly Medication Adherence Intervention Using the My Interventional Drug-Eluting Stent Educational App: Multisite Randomized Feasibility Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8(6):e15900. https://doi.org/10.2196/15900

Zhu X, Li M, Liu P, Chang R, Wang Q, Liu, J (2020) A mobile health application-based strategy for enhancing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. Archives of psychiatric nursing 34(6):472–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2020.08.001

Höchsmann C, Infanger D, Klenk C, Königstein K, Walz SP, Schmidt-Trucksäss A (2019) Effectiveness of a Behavior Change Technique-Based Smartphone Game to Improve Intrinsic Motivation and Physical Activity Adherence in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR serious games 7(1):e11444. https://doi.org/10.2196/11444

Huang Z, Tan E, Lum E, Sloot P, Boehm BO, Car J (2020) Correction: A Smartphone App to Improve Medication Adherence in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes in Asia: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8(4):e18411. https://doi.org/10.2196/18411

Kim HJ, Kim SM, Shin H, Jang JS, Kim YI, Han DH (2018) A Mobile Game for Patients With Breast Cancer for Chemotherapy Self-Management and Quality-of-Life Improvement: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of medical Internet research 20(10):e273. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9559

Ni Z, Liu C, Wu B, Yang Q, Douglas C, Shaw RJ (2018) An mHealth intervention to improve medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease in China: Development of an intervention. International journal of nursing sciences 5(4):322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.09.003

Márquez Contreras E, Márquez Rivero S, Rodríguez García E, López-García-Ramos L, Carlos Pastoriza Vilas J, Baldonedo Suárez A, Gracia Diez C, Gil Guillén V, Martell Claros N, Compliance Group of Spanish Society of Hypertension (SEH-LELHA) (2019) Specific hypertension smartphone application to improve medication adherence in hypertension: a cluster-randomized trial. Current medical research and opinion 35(1):167–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1549026

Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW, Grant M, Sikorskii A, You M, Decker V (2013) An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents: an exploratory study. Cancer nursing 36(1):18–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182551587

Tokdemir G, Kav S (2017) The Effect of Structured Education to Patients Receiving Oral Agents for Cancer Treatment on Medication Adherence and Self-efficacy. Asia-Pacific journal of oncology nursing 4(4):290–298. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_35_17

Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA (2009) Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemedicine journal and e-health: the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 15(3):231–240. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2008.0099

Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS (2015) Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research 17(2):e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3951

Pagès-Puigdemont N, Valverde-Merino MI (2018) Methods to assess medication adherence. Ars Pharm Internet 59(3):163–72. https://doi.org/10.30827/ars.v59i3.7387

López LJR, Mahecha JSS, Sanabria YPC (2017) Experimental validation model of Activ and Smca app’s for health-care. Cienc Poder Aéreo 12(1):192–201. https://doi.org/10.18667/cienciaypoderaereo.571

Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, Wardle J (2010) How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur J Soc Psychol 40(6):998-1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Rice M (1985) Health education, behavior changes, communication technologies and educational materials. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam 98(1):65-79,

Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L (2017) Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC family practice 18(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0608-2

Funding

The results presented in this systematic literature review are part of the research project "Mobile application to strengthen adherence to tuberculosis treatment in the city of Bogotá" funded by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation within the framework of the “Call for the strengthening of CTEI projects in medical and health sciences with young talent and regional impact”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The evaluation presented here was carried out in collaboration with all authors. BPL developed a study design and supervised the study. EAJC and BP drafted the manuscript. EAJC and BP conducted data collection and analysis. FMR, JLMC, CDF and AMM interpreted results from a medical point of view. EAJC and BP conducted a comprehensive content review. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Considerations

This work does not involve the use of human subjects.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. Sponsor’s role: none.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Mobile & Wireless Health

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez-Chala, E.A., Durantez-Fernández, C., Martín-Conty, J.L. et al. Use of Mobile Applications to Increase Therapeutic Adherence in Adults: A Systematic Review. J Med Syst 46, 87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01876-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01876-2