Abstract

The goal of this study is to examine the trends of Electronic Health Record (EHR) adoption among hospitals in Japan compared to those in the United States. Japan’s nationwide survey of hospitals was utilized to extract the EHR adoption rates among Japanese hospitals. Comparable datasets from the Healthcare Information and Management System Society (HIMSS) and the American Hospital Association (AHA) were utilized to extract EHR adoption rates among U.S. hospitals. The trends of EHR adoption were stratified and analyzed by hospital size and hospital ownership status. As of 2014, the U.S. hospitals had a wider adoption of ‘basic with clinical notes’ EHRs compared to Japan (45.6% vs. 27.3%), but large hospitals (400+ beds) in Japan have shown a similar adoption rate of EHR systems than those of U.S. (65.6% vs. 68.5%). Governmental hospitals tend to be more advanced in EHR adoption than non-profit hospitals in Japan (53.0% vs. 21.5%). Non-profit hospitals show the highest adoption rate of ‘basic’ EHR systems in the U.S. as of 2014 (63.3%). Using the ‘certified’ definition of EHRs, the EHR adoption rate was close to 96% among U.S. hospitals as of 2016; however, updated EHR adoption data from Japanese hospitals has yet to be collected and published. U.S. and Japan have considerably increased EHR adoption among hospitals; however, this analysis indicates different trends of EHR adoption among hospitals by size and ownership status in both countries. Learnings from government programs supporting EHR adoption in the U.S. and Japan can be helpful in planning useful strategies for future hospital-oriented health IT policies in other developed nations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

EHR systems are getting prevalent in hospitals worldwide [1,2,3]. Regardless of the local definitions of EHRs and hospital denominators, which are often non-comparable, the adoption of EHRs has reached historical levels among developed countries. For example, based on the U.S. definition and certification of EHRs, the adoption of ‘basic’ EHRs among non-federal acute-care U.S. hospitals has reached 83.8% in 2015 [4, 5]. Japan’s rate of EHR adoption among hospitals has reached 34.2% in 2014 [6], and South Korea has achieved 58.1% adoption in 2015 [7]. Among physicians, EHR adoption has been close to 99% in Norway, Sweden, U.K., Netherlands and New Zealand since 2015 [8,9,10].

A national EHR adoption rate refers to the percentage of hospitals (or physicians) using EHR in a country; however, most of these national rates are not comparable due to the differences and ambiguities in the definition of what constitutes an EHR (e.g., minimum functionalities), the selection of the hospitals (e.g., hospital categories; denominator representation), and different time lags for reporting (e.g., annual rates versus biennial and triennial rates). For example, in Japan, EHR adoption among hospitals is measured every three years by a mandatory survey assuming an extensive definition for EHR functionalities, while the U.S. uses various mechanisms (federal, associations, and commercial) to track EHR adoption among hospitals on an annual basis using different definitions of EHR functionalities (e.g., certified vs. basic) [5, 11, 12].

EHR adoption in Japan

The EHR adoption rates in Japan are surveyed every three years by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) [13,14,15]. Responding to the MHLW survey is considered mandatory for all medical institutions (including hospitals and clinics). According to the latest MHLW survey in 2014, the average rate of EHR adoption, either totally or partially, among general hospitals in Japan has been 34.2% [6, 13]. In the earlier surveys dating back to 1999, MHLW has utilized the Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) concept instead of the term EHR due to past regulations defining an official medical record [16]. In 2001, MHLW published the “Grand Design” for the development of health IT in Japan, which since has promoted the growth of EHRs in Japan [15,16,17].

The rate of EHR adoption among Japan’s hospitals has gradually increased over the last decade; however, the rate significantly varied, depending on the size of hospitals. The average rate of EHR adoption has transitioned from 10.8% (2008), to 17.3% (2011) and to 27.3% (2014) [6]. In 2014, more than 65.6% of hospitals with 400+ beds had EHRs whereas only 14.2% of hospitals with fewer than 100 beds had EHRs at the point of care (excludes hospitals that partially adopted EHR systems) [13].

EHR adoption in the U.S.

The U.S. nationwide policies and programs were implemented through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009 [18, 19] and the Federal Health IT Strategic Plan [20, 21], resulting in the rapid adoption of EHRs that satisfied the Meaningful Use (MU) requirement in the U.S. [22] The EHR Incentive Program, managed and administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), provided hospitals and office-based physicians with the financial incentives to facilitate the adoption of ‘certified’ EHRs [23, 24]. The MU program was released in multiple stages requiring various objective and optional measures for the ‘meaningful use’ of EHRs by U.S. non-federal hospitals [19]. MU stage-1 focused on data capture and sharing (2011-2012), and subsequent regulation for stage-2 focused on advanced clinical processes (2014) [22]. MU stage-3 was proposed in 2015, but as a result of the 2015 Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) and implementation of its provisions for the 2017 program year, the MU program has been replaced by the Accessing Care Information component of the Medicare Quality Payment Program [25].

In 2008, only 9.4% of non-federal acute care hospitals adopted a ‘basic’ EHR with electronic clinical record, medication, and some result management functions. In 2015, over 80% of non-federal acute care hospitals adopted at least a ‘basic EHR with clinician notes’, and around 96% of them had a certified EHR [5].

In this manuscript, we present the status of EHR adoption in Japan from 2008 to 2014, and compare this trend with that of the U.S. by hospital size and ownership. The manuscript concludes with a policy discussion on the implication of the precedents in the U.S. for the further advances of EHR adoption in Japan.

Methods

Hospital definition reconciliation

Comparing the trends of EHR adoption in the U.S. with that of Japan required defining groups of hospitals representing the same underlying concepts. We investigated the difference of hospitals’ characteristics in both countries from 2008 to 2014. In general, features of the hospitals have not changed substantially from 2008 to 2014 in either U.S. or Japan (see Table 1).

More than half of hospitals in the U.S. are small size (0-99 beds), whereas more than half of hospitals in Japan are medium size (100-399 beds). Over 65% of hospitals in the U.S. are located in urban areas whereas only 40% of hospitals in Japan are considered urban. Notably, one-quarter of hospitals in the U.S. are for-profit even though the majority are non-profit (see Table 1). Over 80% of hospitals in Japan are non-profit and none are for-profit due to the Medical Care Act mandating non-profitability of medical institutions (article 7 section 5 and article 54) [26].

There is also a relatively remarkable difference in teaching status. In the U.S., around 30% of hospitals are considered teaching-related hospitals (major or minor), with the proportion of teaching hospitals gradually increasing since 2008. On the other hand, slightly over 10% hospitals in Japan are considered teaching hospitals (either university hospitals or clinical training hospitals) [27, 28].

Matching criteria was used to group hospitals by size and ownership when making comparison between the U.S. and Japan [29,30,31]. See Appendix A (Tables 2, 3, 4 to 5) for additional details about the U.S. and Japanese hospital comparisons.

EHR definition reconciliation

Before comparing the EHR adoption rate in Japan and the U.S., we reconciled the definitions of EHRs between the different data sources and recalculated adoption rates if necessary to reflect the closest comparable rates. In the U.S., a ‘certified’ EHR is defined as an EHR technology that has been certified to meet federal requirements of the CMS’ EHR incentive program [22]. A number of U.S. data sources have collected additional EHR functionalities, going beyond MU requirements, thus generating additional definitions for EHRs such as ‘basic’ EHRs (perhaps a misnomer as it refers to a more comprehensive EHR compared to the ‘certified’ EHR) [11, 32, 33]. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) defines the electronic functions required for hospital adoption of an EHR system through a consensus expert panel [11, 19]. A ‘comprehensive’ EHR has also been defined in the literature [11]. The literature also splits the ‘basic’ EHR definition into ‘basic without clinical notes’ and ‘basic with clinical notes’ [34]. Basic EHR adoption requires that each function be implemented in at least one unit of the hospital [32, 34]. An EHR system that included all required functions in all clinical units was classified as comprehensive [7, 34]. See Appendix B (Table 6) for additional details about the comparison of basic [without clinical notes], basic with clinical notes, and comprehensive EHRs.

In Japan, the MHLW survey of hospitals focuses on adoption of EHR and CPOEs [14]; however, there is no consensus on what functionalities constitute the essential elements necessary to define an EHR in the hospital setting in Japan. Based on a prior survey [34], the commonly used EHR in Japan is closest to functionalities of the ‘basic EHR with clinical notes’. Consequently, we compared the adoption rate of basic EHRs with clinical notes in the U.S. with that of Japan. The following EHR functions are required for the “basic EHR with clinical notes”: capturing patient demographics, physician notes, nursing assessments, problem lists, medication lists and discharge summaries as well as an order entry system for medications and the ability to view lab, radiology, and diagnostic test reports.

Data sources

Japan

The statutory inquiry called “Static Surveys of Medical Institutions” (the survey) conducted by the MHLW every three years (i.e., 2008, 2011, and 2014) was the primary source for examining the status and trend over time of EHR adoption at medical institutions in Japan [13]. Results for the 2017 survey will not be released until 2019.

United States

Data were extracted from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey and AHA’s Information Technology (IT) Supplement [31]. HIMSS’ Analytic database (a.k.a. EMRAM) was also utilized [35]. CMS’ MU adoption rate data were not used in this study due to major differences between the definitions of ‘certified’ EHRs and ‘basic’ EHRs thus making it incomparable to Japan’s EHR adoption rate.

Scope

The scope included all types of comparable hospitals in the U.S. and Japan as of 2008, 2011, and 2014. The analysis excluded outpatient settings and non-hospital clinics.

Japan

Hospitals are often defined as healthcare organizations with 20+ beds [16]. The latest MHLW report shows that there are 8414 hospitals in Japan as of October 2017 [14].

United States

HIMSS dataset covers more than 60% of hospitals in the U.S. [35] The AHA Annual Survey covers all hospitals identified by the AHA as open and operating as a hospital [31]. The AHA report shows that there are 5564 hospitals in the U.S. as of 2017 [36].

Analysis

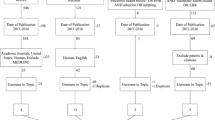

We utilized the survey of all hospitals that are members of the AHA and that are comparable to MHLW in Japan for the presence of specific EHR functionalities. Using a comparable definition of EHRs, we determined the proportion of hospitals that have ‘basic with clinical notes’ EHR systems, and then compared the trend of EHR system adoption in the U.S. with that of Japan. We also examined the relationship of adoption of EHRs to specific hospital characteristics such as size or ownership. The trends of EHR adoption were analyzed by size (number of beds) and ownership status in each country (government, non-profit, and for-profit). We used Microsoft Excel and Access for managing HIMSS EMRAM and MHLW datasets, SQL to extract hospital information from AHA, and R (v3.4.1) to generate the statistics.

Results

EHR adoption by hospital size

Japan

Large hospitals significantly boosted the EHR adoption rates since 2008 with over 65.6% of large hospitals utilizing ‘basic EHRs with clinical notes’ as of 2014 (Fig. 1). In contrast to large hospitals, medium and small hospitals remain low in EHR adoption even though their rates tripled from 2008 to 2014 (11.3% to 29.3%; and, 4.8% to 14.2%). Notably, in 2014, the rate of EHR adoption among large-size hospitals was more than twice as high as that of medium-size hospitals (65.6% vs. 29.3%) and more than four times as small-sized hospitals (65.6% vs. 14.2%; Fig. 1).

United States

Large hospitals significantly boosted the EHR adoption rates since 2008 and over 68.5% of large hospitals and 56.2% of medium hospitals utilize ‘basic EHR with clinical notes’ as of 2014. In contrast to large hospitals, small hospitals remain low EHR adopters, but its growth rate is significant (almost tripling from 10.6% in 2011 to 32.5% in 2014). Note that the adoption rates in the U.S. are calculated using the ‘basic EHR with clinical notes’ definition – which includes a more comprehensive criteria than the EHR definition used for the meaningful use program – hence showing lower rates compared to the adoption rates published by the ONC for the aforementioned years [4, 5].

EHR adoption by hospital ownership type

Japan

In Japan, the rate of EHR adoption has continuously increased since 2008 regardless of ownership; however, the trend of the EHR adoption significantly differs depending on ownership status. Government hospitals have increased their EHR adoption from 21.0% in 2008 to 53.0% in 2014 while non-profit hospitals have improved their adoption rates from 8.5% to 21.5% in the same period.

United States

In the U.S., the rate of EHR adoption has drastically increased since 2008 regardless of ownership, and unlike Japan, the governmental and non-profit hospitals show similar trends except for the for-profit hospitals (Fig. 2). Even though the governmental hospitals show much higher rates of EHR adoption than that of non-profit hospitals in Japan, the U.S. governmental hospitals show a lower rate of EHR adoption compared to non-profit hospitals (46.5% vs. 63.3% in 2014; Fig. 2).

Overall EHR adoption by hospitals

The average rate of “basic EHR with clinical notes” adoption in Japan has gradually increased from 10.8% in 2008 to 27.3% in 2014 (Fig. 3). In comparison, the average adoption rate of a similarly defined EHR in the U.S. has sharply increased from 3.3% in 2008 to 45.6% in 2014, overtaking the rate in Japan after 2011. Note that the HITECH Act was implemented in 2009 and promoted the adoption of EHR systems in the U.S. See Appendix C (Fig. 4) for an overall summary of EHR adoption rate between U.S. and Japan hospitals.

Discussion

To compare the adoption of EHRs among hospitals of Japan and the U.S., a comparable definition of EHR was established and two different data sources (i.e., HIMSS EMRAM for the U.S. and MHLW for Japan) were used to calculate adoption rates. Overall, similar trends in EHR adoption were seen in both countries. Large hospitals tend to have higher EHR adoption rates whereas small hospitals have lower EHR adoption rates. The average adoption rate of ‘basic with clinical notes’ EHR among hospitals in the U.S. outstrips that of Japan after 2011, growing to 45.6% in 2014 compared to 27.3% in Japan. Despite these similarities, a few differences were notable about the trends of EHR adoption.

Notable differences in EHR adoption

The lower rate of EHR adoption among medium to small size hospitals of Japan compared to the U.S. can be explained by the fact that the Japanese government has prioritized the hospital subsidies (almost 61% of the incentives from 2000 to 2008) for EHR adoption to 200+ bed hospitals, which made 60% + of the medium-size hospitals ineligible for the subsidies [16]. In contrast, the U.S. government has offered the EHR financial incentives regardless of the hospital size as long as they achieved the MU requirements [5, 21].

Governmental hospitals are apt to be larger than non-profit hospitals in Japan, which possibly has been a factor in the higher EHR adoption rate among them. In the U.S., however, governmental hospitals are generally smaller than non-profit hospitals. The median size of governmental hospitals in Japan is roughly 300 beds whereas that of governmental hospitals in the U.S. is around 60 beds [31, 37, 38]. This difference in size, along with the fact that most federal U.S. hospitals were not eligible to receive MU incentives for EHR adoption, might have affected the trend of EHR adoption in U.S. and Japan based on hospital ownership type.

The U.S. healthcare system’s move toward value-based care has incentivized hospitals to strive for desired population health outcomes within fixed budgets [39,40,41,42,43]. These value-based policies can also be considered a driver to adopt and use EHRs as a potential data source to improve the management of patient populations (e.g., using EHRs for risk stratification and care coordination) [44,45,46,47,48,49]. In the Japanese health system, however, such added incentives to adopt EHRs for population health management do not apply due to the already existing universal health care system [26].

Major barriers to EHR adoption in Japan

The common barriers to EHR adoption are similar in both the U.S. and Japan: inadequate capital needed to purchase and implement EHRs, the potential adverse effects on workflow, and the concern about the cost of maintenance and support after EHR implementation [23, 24,34]. In the U.S., the financial support by the federal government totaled up to an unprecedented $27 billion over 10 years; however, there was limited financial support available (i.e., $622.4 million from 2000 to 2008) for EHR implementation in Japan [16, 17].

National standards for EHR systems are critical for developing interoperable EHR systems. There were no pragmatic national standards for EHRs in Japan under past incentives, and each vendor established their own de-facto standard [37]. New policies under the experimental approach called “SS-MIX2” have recently started to gain traction for the implementation of interoperable EHRs in Japan [50, 51]. The U.S. has also faced challenges in developing standards and implementing interoperable EHRs, however, the federal government and the EHR vendor community have actively discussed policies, incentives, and development of infrastructure to increase interoperability over the past several years [52,53,54,55,56].

Recommendations for future EHR adoption policies in Japan

Future financial incentives for EHR adoption by the Japanese government might consider “Meaningful Use” of EHRs as a condition for the subsidies. Similar to the MU program in U.S., the MU criteria in Japan should set specific objectives for hospitals to achieve in order to receive the incentives. Due to the lower adoption of EHRs among small to medium size hospitals, the Japanese government can prioritize the incentives and perhaps tailor the MU criteria with more achievable options for those hospitals [57, 58]. And, perhaps by learning from the lack of clear interoperability mandates in the U.S. MU’s program [52], the proposed Japanese MU program may include pragmatic interoperability objectives in the next round of subsidies.

In the broader context of the Japanese universal healthcare coverage (UHC), EHRs should play a key role for improving healthcare delivery, as UHC has encountered financial difficulty to maintain the status quo partly due to the aging population [59]. Aligning the new UHC goals with potential future EHR objectives for new subsidies must be an important function to improve the efficiency of healthcare in Japan [60]. For example, Japan has a high ratio of hospital beds relative to its population [13]. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED) reports that the Japanese average length of stay (LOS) in a hospital is remarkably longer than those of other countries (16.9 days in 2014) [61]. Thus, MHLW encourages shortening the LOS by reducing unnecessary long stays, increasing the utilization of hospital beds, and streamlining hospitals in the near future. In such a context, EHRs will play a key role to preserve and exchange patients’ information in an interoperable format while hospitals are being consolidated.

Limitations

Fundamental differences in underlying factors affecting the health delivery systems

While we have compared the adoption of EHRs, we did not control for underlying fundamental differences of healthcare delivery systems in Japan and U.S. The central government plays a substantial role in funding and managing the Japanese healthcare system, which is structurally different from the U.S. healthcare delivery system. The Japanese government regulates most aspects of the universal public health system, and MHLW sets the nationwide policy and regulations [26]; however, in the U.S., the federal government only sets the major outlines of health care delivery and most details are set by states, health systems, and hospitals [3]. Consequently, U.S. hospitals often have direct oversight on their finances and can decide on purchasing the most fit EHR for their organization [19, 32], but in Japan, the MHLW-directed standardized pricing system, often limits such options [34].

Lack of comparable terminologies and contextual factors defining hospitals or EHRs

We tried to make the classification of hospitals as similar as we could, but there are several categories that do not have comparable equivalents. For example, there is the “church operated” ownership in the U.S. that does not have an equivalent category in Japan’s MHLW survey. In addition, there are differences in social, cultural, or other factors making it difficult to perfectly compare hospitals in the U.S. with those in Japan. For a similar reason, comparing the EHR adoption rates between teaching vs. non-teaching and rural vs. urban hospitals was determined to be infeasible and hence not covered in this manuscript.

Matching EHR functions and definitions was not ideal. Although ONC has clear definitions for ‘basic’ and ‘comprehensive’ EHRs in the U.S., Japan has not formed that kind of consensus yet. Based on the literature review, we estimated that the most prevalent EHR in Japan was a ‘basic with clinical notes’ EHR; however, there are some differences that were not addressed in this manuscript.

Limitations of data sources to calculate comparable EHR adoption rates

Although the detailed individual hospital data was utilized in the analyses of the U.S. EHR adoption, only summarized data was utilized in the analyses of Japanese EHR adoption. Also, due to the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the MHLW excluded the hospitals in some severely damaged area from its statistics in 2011, although this exclusion only accounted for less than 2% of all hospitals in Japan [13, 62, 63].

The AHA Annual Survey has an overall 80% response rate, and an estimation method is applied to impute missing statistical values. Response rate, respondents and non-respondents may differ by unobserved selection effects [31].

Limitations of the scope of the manuscript

This study only compared the adoption of EHRs among hospitals and did not evaluate the adoption of EHRs in outpatient settings (e.g., primary care clinics); hence, recommendations offered for future EHR incentive programs in Japan should be interpreted considering these limitations (e.g., lack of outpatient context to develop a population-level health IT agenda [64, 65]). Furthermore, at the time this manuscript was authored, MHLW 2017 data was not publicly released thus limiting the comparison to 2008-2014 despite having access to 2017 U.S. data.

Conclusion

The U.S. and Japan indicate different trends of EHR adoption. The prevalence of EHR is significantly affected by characteristics of hospitals (e.g., size and ownership type), as well as governmental policies and incentives for EHR adoption. Further growth of EHR adoption in Japan will be dependent on the type of policies targeting hospitals in various sizes and ownerships.

References

The Commonwealth Fund. What is the status of electronic health records?. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Aug 10]. Available from: http://international.commonwealthfund.org/features/ehrs/.

Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS). Electronic health records: A global perspective. [internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Jul 9]. Available from: http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-himss/files/production/public/HIMSSorg/Content/files/Globalpt1-edited%20final.pdf.

Stone, C.P., A glimpse at EHR implementation around the world: The lessons the US can learn. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 8]. Available from: http://www.e-healthpolicy.org/docs/A_Glimpse_at_EHR_Implementation_Around_the_World1_ChrisStone.pdf.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Non-federal acute care hospital health IT adoption. [internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jun 2]. Available from: http://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Hospital-EHR-Adoption.php.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Adoption of electronic health record systems among U.S. non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2008-2015. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jun 2]. Available from: https://dashboard.healthit.gov/evaluations/data-briefs/non-federal-acute-care-hospital-ehr-adoption-2008-2015.php.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Facilitation in informatization in healthcare field. [internet]. [cited 2016 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/johoka/.

Kim, Y. G., Jung, K., Park, Y. T., Shin, D., Cho, S. Y., Yoon, D., and Park, R. W., Rate of electronic health record adoption in South Korea: A nation-wide survey. Int. J. Med. Inform. 101:100–107, 2017.

The Commonwealth Fund. A survey of primary care doctors in ten countries shows progress in use of health information technology, less in other areas. [internet]. 2012 [cited 2017 Jun 8]. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/in-the-literature/2012/nov/1644_schoen_survey_primary_care_doctors_10_countries_ha_11_15_2012_itl_v2.pdf.

The Commonwealth Fund. 2015 Commonwealth Fund international survey of primary care physicians in 10 nations. [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives-and-data/surveys/international-health-policy-surveys/2015/2015-international-survey.

The Commonwealth Fund. 2015 International Survey of Physicians. [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jun 19]. Available from: http://international.commonwealthfund.org/data/2015/.

Jha, A., Burke, M., DesRoches, C., Joshi, M., Kralovec, B., Campbell, E., and Buntin, M., Progress toward meaningful use: Hospitals’ adoption of electronic health records. The American Journal of Managed Care., 17(Special Issue), 2011.

Adler-Milstein, J., DesRoches, C.M., Kralovec, P., Foster, G., Worzala, C., Charles, D., Searcy, T., and Jha, A.K. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: Progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Affairs. ;34(12), 2015.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of medical institutions: Feb 2017 report. [internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/NewList.do?tid=000001030908.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of medical institutions: Oct 2017 report. [internet]. [cited 2018 Feb 3]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/m17/dl/is1701_01.pdf.

Tanaka, H., Current status of electronic health record dissemination in Japan. Jap. Med. Assoc. J. 50(5):399–404, 2007.

Yoshida, Y., Imai, T., and Ohe, K., The trends in EMR and CPOE adoption in Japan under the national strategy. Int. J. Med. Inform. 82(10):1004–1011, 2013.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and welfare. Grand design for development of information systems in the healthcare and medical fields. [internet]. 2001 [cited 2017 May 30]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/0112/s1226-1b.html.

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) act, title XIII of division a and title IV of division B of the American recovery and reinvestment act of 2009 (ARRA). Feb 17 2009. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/hitechact.pdf.

Blumenthal, D., and Tavenner, M., The meaningful use regulation for electronic health records. New England Journal of Medicine. 363(6):501–504, 2010.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT strategic planning. [internet]. [cited 2017 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/health-it-strategic-planning.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2016 Report to congress on health IT Progress: Examining the HITECH era and the future of health IT. [internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 2]. Available from: https://dashboard.healthit.gov/report-to-congress/2016-report-congress-examining-hitech-era-future-health-information-technology.php.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Meaningful use definition & objectives. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 3]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives.

Jamoom, E. W., Patel, V., Furukawa, M. F., and King, J., EHR adopters vs. non-adopters: Impacts of, barriers to, and federal initiatives for EHR adoption. Healthcare (Amst). 2(1):33–39, 2014.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Electronic health records (EHR) incentive programs. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/ehrincentiveprograms/.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Stage 3 program requirements for providers attesting to their state’s Medicaid EHR incentive program. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Stage3Medicaid_Require.html.

International Labor Organization. Medical Care Act [Japan]. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Sep 10]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/95119/111872/F302712024/JPN95119.pdf.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of residency program. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/seisaku/2009/08/04.html.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Residency program. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10800000-Iseikyoku/0000058438.pdf.

Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Category of local government. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/jichi_gyousei/bunken/chihou-koukyoudantai_kubun.html.

United States Census Bureau. Metropolitan and Micropolitan glossary. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro/about/glossary.html

American Hospital Association. AHA Data and Directories. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Sep 2]. Available from: http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/data-and-directories.shtml.

Jha, A. K., DesRoches, M., Campbell, E. G., Donelan, K., Rao, S. R., Ferris, T. G., Shields, A., Rosenbaum, S., and Blumenthal, D., Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. New England J. Med. 360(16):1628–1638, 2009.

Blumenthal, D., DesRoches, C., Donelan, K., Ferris, T., Jha, A., Kaushal, R., Rao, S., and Rosenbaum, S., Health information Technology in the United States: The Information Base for Progress. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2006.

Inokuchi, R., Sato, H., Nakamura, K., Aoki, Y., Shinohara, K., Gunshin, M., Matsubara, T., Kitsuta, Y., Yahagi, N., and Nakajima, S., Motivations and barriers to implementing electronic health records and ED information systems in Japan. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 32:725–730, 2014.

Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS). Electronic medical record adoption model (EMRAM). [internet]. [cited 2017 Feb]. Available from: https://app.himssanalytics.org/emram/emram.aspx.

American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals 2017. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals-2017

National Hospital Organization [Japan]. Project to establish IT infrastructure for standardizing EHR. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.hosp.go.jp/files/000042855.pdf.

Japan Hospital Association. List of membership. [internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.hospital.or.jp/shibu_kaiin/.

Hatef, E., Lasser, E. C., Kharrazi, H. H., Perman, C., Montgomery, R., and Weiner, J. P., A population health measurement framework: Evidence-based metrics for assessing community-level population health in the global budget context. Popul. Health Manag. 21(4):261–270, 2018.

Hatef, E., Kharrazi, H., VanBaak, E., Falcone, M., Ferris, L., Mertz, K., Perman, C., Bauman, A., Lasser, E. C., and Weiner, J. P., A state-wide health IT infrastructure for population health: Building a community-wide electronic platform for Maryland's all-payer global budget. Online J. Publ. Health Inform. 9(3):e195, 2017.

Dixon, B. E., Kharrazi, H., and Lehmann, H. P., Public health and epidemiology informatics: Recent research and trends in the United States. Yearb Med. Inform. 10(1):199–206, 2015.

Dixon, B. E., Pina, J., Kharrazi, H., Gharghabi, F., and Richards, J., What's past is prologue: A scoping review of recent public health and Global Health informatics literature. Online J. Publ. Health Inform. 7(2):e216, 2015.

Gamache, R., Kharrazi, H., and Weiner, J. P., Public and population health informatics: The bridging of big data to benefit communities. Yearb Med. Inform. 27(1):199–206, 2018.

Kharrazi, H., Chi, W., Chang, H. Y., Richards, T. M., Gallagher, J. M., Knudson, S. M., and Weiner, J. P., Comparing population-based risk-stratification model performance using demographic, diagnosis and medication data extracted from outpatient electronic. Med. Care. 55(8):789–796, 2017.

Chang, H. Y., Richards, T. M., Shermock, K. M., Elder Dalpoas, D. S., J Kan, K. H., Alexander, G. C., Weiner, J. P., and Kharrazi, H., Evaluating the impact of prescription fill rates on risk stratification model performance. Med. Care. 55(12):1052–1060, 2017.

Lemke, K. W., Gudzune, K. A., Kharrazi, H., and Weiner, J. P., Assessing markers from ambulatory laboratory tests for predicting high-risk patients. Am. J. Manag. Care. 24(6):e190–e195, 2018.

Kharrazi, H., Chang, H. Y., Heins, S. E., Weiner, J. P., and Gudzune, K. A., Assessing the impact of body mass index information on the performance of risk adjustment models in predicting health care costs and utilization. Med. Care. 56(12):1042–1050, 2018.

Kharrazi, H., and Weiner, J. P., A practical comparison between the predictive power of population-based risk stratification models using data from electronic health records versus. Med. Care. 56(2):202–203, 2018.

Hatef, E., Weiner, J. P., and Kharrazi, H., A public health perspective on using electronic health records to address social determinants of health: The potential for a national system of local community. Int. J. Med. Inform. 124:86–89, 2019.

Kimura, M., Nakayasu, K., Ohshima, Y., Fujita, N., Nakashima, N., Jozaki, H., Numano, T., Shimizu, T., Shimomura, M., Sasaki, F. et al., SS-MIX: A ministry project to promote standardized healthcare information exchange. Methods Inform. Med. 50(2):131–139, 2011.

The Consortium for SS-MIX Dissemination and Promotion. SS-MIX2. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.ss-mix.org/consE/.

Adler-Milstein, J., Embi, P., Middleton, B., Sarkar, I., and Smith, J., Crossing the health IT chasm: Considerations and policy recommendations to overcome current challenges and enable value-based care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24(5):1036–1043, 2017.

Samarath, A., Sorace, J., Patel, V., Boone, E., Kemper, N., Rafiqi, F., Yencha, R., and Kharrazi, H., Measurement of interoperable electronic health care records utilization. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2016, HHSP233201500099I_HHSP23337001T. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255526/EHRUtilizationReport.pdf.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Connecting health and care for the nation: A shared nationwide interoperability roadmap. [internet]. [cited 2017 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hie-interoperability/nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-final-version-1.0.pdf.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Proposed interoperability standards measurement framework. [internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 22]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/ONCProposedIOStandardsMeasFrameworkREV.pdf.

The Sequoia Project. About the Sequia Project. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Dec 10]. Available from: http://sequoiaproject.org/about-us/.

Chan, K., Kharrazi, H., Parikh, M., and Ford, E., Assessing electronic health record implementation challenges using item response theory. Am. J. Manag. Care. 22(12):e409–e415, 2016.

Kharrazi, H., Gonzalez, C. P., Lowe, K. B., Huerta, T. R., and Ford, E. W., Forecasting the maturation of electronic health record functions among US hospitals: Retrospective analysis and predictive model. J. Med. Internet Res. 20(8):e10458, 2018.

Ikegami, N., Yoo, B. K., Hashimoto, H., Matsumoto, M., Ogata, H., Babazono, A., Watanabe, R., Shibuya, K., Yang, B. M., Reich, M. R. et al., Japanese universal health coverage: Evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet. 378(9796):1106–1115, 2011.

Shimada H, Kondo J. Japan HIT Case Study. [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2017 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.pacifichealthsummit.org/downloads/HITCaseStudies/Economy/JapanHIT.pdf.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Length of hospital stay. [internet]. [cited 2017 May 19]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/length-of-hospital-stay.htm.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and welfare. Survey of medical institutions (annual). [internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003078776.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of medical institutions: May 2011. [internet]. [cited 2018 Feb 10]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/m11/is1102.html.

Kharrazi, H., Lasser, E. C., Yasnoff, W. A., Loonsk, J., Advani, A., Lehmann, H. P., Chin, D. C., and Weiner, J. P., A proposed national research and development agenda for population health informatics: Summary recommendations from a national expert workshop. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24(1):2–12, 2016.

Kharrazi, H., and Weiner, J. P., IT-enabled community health interventions: Challenges, opportunities, and future directions. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2(3):1117, 2014.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Okada Chiharu, MD PhD, from the National Hospital Organization (Tokyo, Japan), for his support and feedback about the MHLW data as well as the overall interpretation of our results within the Japanese healthcare context. We also acknowledge Dr. Eric Ford at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (Baltimore, U.S.) for his insightful input and HIMSS (Chicago, U.S.) for providing us with the EMRAM datasets.

Availability of Data

MHLW data are publicly available [13, 14]. EMRAM data are proprietary and can be acquired for a fee from HIMSS [35].

Funding

N/A

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were actively involved in the development of the study’s aim. All authors reviewed, commented, and revised the manuscript as needed. HK and TK led the study. HK and TK co-led the analysis and interpretation of the results, as well as drafting the manuscript. HK prepared the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Authors do not have any conflict of interest to report.

Ethics Approval

N/A

Consent for Publication

N/A

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Systems-Level Quality Improvement

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanakubo, T., Kharrazi, H. Comparing the Trends of Electronic Health Record Adoption Among Hospitals of the United States and Japan. J Med Syst 43, 224 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-019-1361-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-019-1361-y