Abstract

Online communities, created and sustained by people sharing and discussing texts on the internet, play an increasingly important role in social health movements. In this essay, we explore a collective mobilization in miniature through an in-depth analysis of two satiric texts from an online community for people with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). By blending a sociological analysis with a rhetorical exploration of these texts, our aim is to grasp the discursive generation of a social movement online community set up by sufferers themselves to negotiate and contest the dominating biomedical perception of their condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The denotation of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) is a medically unexplained long-term exhaustion and energy failure. The connotations of ME are many and complex; they range across the history of medicine, the shifting ground of doctor-patient power relations, the evolving communities of patients with shared interests, and the sociology of diagnosis. After decades of controversy, ME remains a key point of intersection for discourses of medicine, politics, identity, and activism.

The key symptom of ME is a lasting post-exertional fatigue, often accompanied by bowel problems, sleep disturbances, concentration difficulties and problems with the regulation of body temperature (Carruthers et al. 2011). Diagnosis is primarily based on assessing symptom descriptions against diagnostic criteria (Brurberg et al. 2014). The diagnosis is currently given primarily to women with a female to male ratio of about six to one (Brenu et al. 2013).

Long-term exhaustion has been a medically contested condition ever since it became medicalised in the 19th century under the label neurasthenia (Aronowitz 1998). Whether the exhaustion is psychogenic, somatic, or a mixture of these is a controversial question heavily debated in medical journals (Lian and Bondevik 2015) as well as in virtual communities on the internet (Grue 2014, Lian and Nettleton 2015), in public media (de Wolfe 2009), and in consultation rooms (Banks and Prior 2001).

The debate is partly a matter of collective patient resistance against psychogenic aetiologies of ME. As with other examples of resistance against medical understandings of contested conditions, the battle increasingly takes place online (Ziebland and Wyke 2012). People create, sustain and change social movement online communities (Caren et al. 2012) as a way to combat what they see as errant or destructive medical power. Joining such an online community is a matter of writing in a particular way, for particular people, by joining the same Facebook groups, commenting on the same blogs, discussing mutually agreed sets of topics, and addressing their texts to a similar implied readership (Iser 1974). In this way, patients seek to challenge the worldview of others, perhaps particularly doctors.

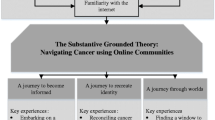

In this essay, we explore how people with ME in Norway discursively generate collective mobilization through the production and dissemination of texts in a social movement online community. The community consists of individual actors who seek recognition for a medically contested chronic condition by writing on different websites. Through their social practice, writers and readers of these texts constitute and reinforce a social structure that qualifies as a community. To explore the ways in which ME-sufferers use online space to discursively negotiate with – and exercise counter-power towards – medical expertise and authority, we have conducted a close reading of two emblematic texts. We particularly wanted to explore how people make use of humour and irony to contest how their ailment is medically named and explained by applying an interdisciplinary discourse analysis of two complete texts which exemplify these tropes. After analysing each text separately, we reflect on how they contribute to the discursive generation of a social movement online community that is embedded within an international social health movement. Our study builds on previous results from a larger study aiming to explore the discursive generation of a virtual symbolic community created by and for ME sufferers in Norway (Lian and Nettleton 2015).

To understand how people collectively organize themselves to form social health movements, and how these movements produce distinctive understandings of biomedicine and health, we need to know more about the discursive processes in which this engagement is enacted. These processes are historically and cultural contingent, and so the cultural perspective becomes vital in understand their underlying dynamics. This goes for all discussions about both lay and medical constructions of health and illness: it is impossible to understand how these constructions are created and maintained or challenged and changed without discussing when, where and who. The interdisciplinary approach of our study therefore involves conducting a rhetorical analysis within a sociological framework. Framing rhetorical analyses within a socio-cultural understanding of health, illness, disease, diagnosis and medical knowledge enables us to destabilize the discrete borders of a rhetorical site or situation (socio-cultural dimensions do not reside in fixed sites) and situate the actors we study in a broader context of interaction (Edbauer 2005). A recent special issue of the Journal of Medical Humanities on ‘Medicine, Health and Publics’ (Keränen 2014; Scott 2014) “demonstrate the benefits of blending humanistic textual analysis with social science methods in order to access public opinions in the places they are formed” (Keränen 2014, 104). Through such approach, we also reinforce “the health and medical humanities’ concern for the humane – and distinctly human – dimensions of health and medicine” (105).

Online communities: a new arena for social movements

The debate about public engagement in health-related matters is a topical issue in Western societies for several reasons: the increasing emphasis on user involvement in health care services, the increasing personal responsibility for handling our health, and the increasing societal scepticism towards the continuous medicalization of human life. In addition to these cultural changes, new information and communication technology give us better opportunities to engage in public debates. In recent decades, the internet has become an important site for such discussions. The internet is a virtual worldwide “free” space where people can connect with each other through faceless communication in a way never seen before. Assisted by this new technology, more and more people join in open and public dialogues about health and medical matters that affect them--either individually or collectively--in social health movements. Under certain conditions, this activity creates online communities that can become a part of a wider social movement.

Social movement online communities

A social movement online community has been defined as “a sustained network of individuals who work to maintain an overlapping set of goals and identities tied to a social movement linked through quasi-public online discussions” (Caren et al. 2012, 163). These communities are constituted, expressed and mediated via a chain of textual and visual utterances from individual participants, posted on the internet. As an online community, it is a symbolic entity located in a virtual space (the internet). Virtual refers to a non-localized space with symbolic demarcations, which exists as a shared mind-set that organizes the activities and perceptions of the actors. Community refers to the cultural dimensions of this space (a shared culture of norms and values) and to the social interaction it contains. All communities, whether physically located or not, are suffused with symbols that function as a medium for cultural meaning and help us discover, rediscover, generate and sustain meaning, both individually and collectively. This is the primary function of a community. The symbolic function of a virtual symbolic community lies in the personal, cultural and symbolic meaning that we – the interpreters – attribute to it. When these communities become part of a social movement, they become part of a distinct social process where actors 1) engage in collective action, 2) are involved in conflict relations with clearly identified opponents, 3) are linked together by dense informal networks, and 4) share a distinct collective identity (della Porta and Diani 2006, 20). A central issue in the study of communities is how their members infuse them with meaning, belonging, fellowship and identity as contrasted with other groups (Cohen 1985).

Textual representations of online communities

Utterances, including texts, derive their meaning partly from prior knowledge and experiences, from other people’s utterances, from the situational context, and from the overarching cultural and historical context. An utterance is therefore a social phenomenon in its “entire range and in each and every of its factors, from the sound image to the furthest reaches of abstract meaning” (Bakhtin 1981, 259). Because utterances are interpreted according to both past texts and events and expectations of future texts or events, their meaning is also shaped by intertextual links (Lenski 1998).

Discourses are embedded in, positioned within, and inseparable from a social context, and therefore historically and culturally contingent. Communication, including in an online community, takes place against a background of shared knowledge and normative expectations. On a textual level, participating in a community means demonstrating familiarity with its culture (Bourdieu 1977), including its conventional modes of communication. The cultural frame, or collective action frame, is a cultural belief system expressing the cultural norms, values and viewpoints that delineate purposes and boundaries of a community (Benford and Snow 2000). The frame is a mode of interpretation that provides the cultural viewpoint from which the community members act. A chain of utterances in a discourse must therefore be understood in relation to this frame: it is derived from it, and it serves to reinforce it. The frame defines the limit of what Butler (1997) refers to as “acceptable speech” and demarcates “the line between the domains of the speakable and the unspeakable” (356). Knowing the discursive frame means knowing how to communicate (how to speak, and how to interpret an utterance).

Previous research

In research on social health movements, the importance of online forums on the internet is widely recognized (Barker 2008; Brown and Zavestoski 2004; Radin 2006). A core issue relates to the functions of these forums, and their empowering potential: are they as useful and empowering as we often assume them to be? Although different studies point to various answers, they usually confirm that online forums create spaces for negotiating and challenging the ways in which medically defined conditions are perceived and treated by health professionals, but their empowering potentiality remains unclear.

A recent example is a conversation analysis of an online forum related to bipolar disorder that revealed an “apparent mismatch between what the new user wanted and what the forum gave” (Vayreda and Antaki 2009, 940). Particularly relevant here is also Dumit’s (2006) research into an online forum run by and for people living with chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple chemical sensitivity. He found that the forum helped patients acknowledge that psychological blame is structurally produced and can be resisted. Crucially, it supplied them with strategies for surviving in medical and bureaucratic systems. Similarly relevant is Fair’s (2010) study of Morgellons, a dermatological condition which only recently gained medical legitimacy. His research showed how an online community ultimately gave rise to a ‘diagnostic compromise’ between patients and practitioners, which resulted in a formal medical acknowledgement of the condition. Barker’s (2008) study of fibromyalgia presents another example. The group she studied ardently denied the possibility that fibromyalgia might have a psychosocial origin. They also expressed their frustrations at doctors who refused to recognize their problems as signs of a “real” disease, and they dismissed any advice from doctors who framed the condition as anything other than an organic entity. Other studies have pointed to the ways in which online communities can provide spaces for participants to share non-medicalized definitions of bodily conditions. Gavin and colleagues (2008) for example found that online communities for anorectics can serve a validating function in which their thoughts, behaviour and identities are confirmed as normal and acceptable. This finding is echoed in Crossley’s (2004) study of British anti-psychiatry mental health movements. Finally, based on a thematic analysis of fourteen Norwegian internet forums sustained by and for people living with ME (monitored over a period of three years), Lian and Nettleton (2015) found four main types of postings: experiential, informative, motivating and political. Across all types of postings, the core messages remained the same: ME is a somatic condition that needs to be treated accordingly. The authors further argued that these sites constituted a virtual symbolic community demarcated by a discursive frame, or norms, values and goals, which defined and reinforced the boundaries of the community. It is this monitoring and thematic analysis which served as the basis for selecting the texts explored in detail in this essay.

Based on a literature review and a service user panel, Ziebland and Wyke (2012) summarize possible positive and negative implications of sharing and reading experiences in peer-to-peer online fora: they provide information that influences people’s own interpretations and experiences of their illness and the ways in which they adjust their lives to it. Whether this is constructive or not varies from case to case: these fora can create a sense of community and support, allay fears and boost confidence, but they can also create anxiety, confusion, shake people’s confidence and increase a “real-world isolation” (234) by reinforcing the notion that only those who suffer the same ailment can understand each other.

Previous research indicates that the use of humour in internet communication have many functions beyond its most obvious “purpose,” which is to amuse: humour can bring people closer to each other, embarrass, ridicule, relieve tension, cause people to reflect on an issue, and put serious affairs into perspective (Kuipers 2015). Internet humour has much of the same functions as in communication in general: it can function as motivation, identification/differentiation, encouragement, resistance, control, persuasion, and tension relief (Lynch 2002). As such, humour can serve as a key to understand social and cultural processes (Shifman 2007).

Methodology

Our study is an interpretive qualitative case-study (QCS) of a Norwegian social movement online community, investigated by a discourse analysis of two texts from publicly accessible internet sites: one website designed as an online newspaper and one public Facebook page. The texts are self-elected expressions, or authentic texts, unguided by questions from researchers. By a close textual reading of these two texts, we explore the discursive process in which a community emerges.

Data selection

The selection of the two texts was made from a total of fourteen Norwegian language websites, observed over a period of three years (2011-2013). Together, these sites constitute an extensive discourse about the ME-diagnosis, situated on the internet and available to anyone who reads Norwegian. Because these sites are accessible primarily through search engines and links from other web sites, they will chiefly be read by people who actively follow ME blogs, forums, etc. or actively look for information using keywords like “ME” and “myalgic encephalomyelitis.”

While following these pages, we read postings related to experiences and perceptions of the health services as a system (including its knowledge base), and professional health care workers encountered in this system. Our main interest was negotiations related to naming and explaining discussants’ illness. We also explored how they presented their understanding of the situation and their views of their illness. While looking for similarities and differences in both topic and style and identifying the main themes, we found that texts expressing critical views towards the medical system (doctors in particular) dominated the debate. Four main types of postings were identified: experiential, informative, motivating and political (Lian and Nettleton 2015).

To expand the study with more in-depth data, we conducted a rhetorical analysis of two motivating texts written in a comic genre. First, we selected ten such texts for a closer look. After gradually discarding the most repetitive ones, we then selected two texts that encapsulate in the clearest possible way the community’s tendency to programmatic, confrontational, ironical and satirical utterances and that display considerable sophistication with regard to communicative strategies. As programmatic statements, they distil and convey the collective understanding in this community with regard to a situation in need of change (problem), who is to blame (guilt), and what is to be done (solution). More balanced and muted texts can easily be found, but our aim is to present the rhetorically salient features of the texts by analysing their linguistic devices and tropes, particularly the use of irony and humour. Although our two texts differ from a lot of the other texts in terms of how, they do not differ in terms of what: both of them effectively illustrate the shared norms, values, assumptions and agreements of the community, the symbolic creativity of its individual members, and the multiple inter-textual connections to other ME texts. We translated the texts from Norwegian to English, and they are quoted in extenso.

Using Norwegian data has several advantages. First, 97 % of Norwegian households have internet access (Norwegian Statistics 2015). Second, online forums for ME and/or chronic fatigue syndrome have the highest numbers of registered users (relative to estimated cases) and more than ten times the relative activity of other disorder-related forums (Knudsen et al. 2012). The unknown aetiology and the social stigma attached to these diagnoses might explain this high level of activity.

Data analysis

Both authors of this essay interpreted the two texts in order to pin down their key themes and identify their structural and linguistic properties. While doing so, we employed a discursive and narrative approach (Fairclough 2013; Frank 2010; Sarangi 2010) meaning that we looked for what is said (what messages does the texts convey?) and how it is said (what kind of rhetorical techniques do they use to convey them?). The latter question relates to linguistic forms and functional properties of language, including the use of rhetorical devices (with a special focus on comic and parodic means). Structural, linguistic and literary devices are important because they aid as well as shape the reader’s interpretation. We also reflected on implied readers, and how different readers would respond to the texts. To explore the cultural assumptions and presuppositions that underlie what they say (and what they do not say), we also interpreted the propositional content of the texts. In order to avoid misinterpretation, we analysed each text as a whole and emphasized the context in which they arise. Without reference to context, the authors’ heavy use of implicit specialist knowledge, acronyms and inside jokes becomes difficult to decode.

Our two texts are textually constituted attempts to deal with and reframe a particular set of social circumstances. To understand the content of the two texts, we therefore related them to their synchronic and diachronic connections: the social circumstances they are responding to (medical texts with a psychogenic approach to ME, stigma related to a contested condition, and so on) and community-internal texts. By viewing the texts as constitutive of a cultural frame means that we focus on who writes them, to whom they are addressed, and to what purpose they are written (Miller 1984). This includes asking what kind of social action the texts constitute. Content analysis is a vital part of this process (where theme, composition and style are important), but so are questions about what is accomplished when people communicate with each other in particular ways, and what norms, values and symbols are produced and re-produced.

Ethics

Ethical requirements of confidentiality and informed consent are difficult to fulfil in research on online activities. There is also an inconclusive debate about whether to perceive this kind of data as private or public (Vayreda and Antaki 2009). According to Eysenbach and Till (2001), informed consent is required if the posting is not intended for public communication but occurs “in a private context where an individual can reasonably expect that no observation or reporting is taking place” (1104). Our data consists of texts made available to the general public after editorial intervention. On Facebook, anonymization of contributions was carried out by the moderator/editor for the purpose of sharing stories with a wider audience. We do not know the identity of the original contributor and have approached the text as indicative of its virtual community. The website for the online newspaper is an edited forum that does not require a user account and presents itself as a general source of information about ME. The texts thus constitute published documents; we have not made use of comments made by individuals in a private capacity. Our use of the data is in accordance with national legislation, which allows for quoting excerpts of copyrighted works (Ministry of Justice and Public Security 2013).

Negotiations of ME in an online community

Ever since long-term exhaustion became defined as a medical condition in the late 19th century, the debate about this condition has been heated (Aronowitz 1998; de Wolfe 2009; Hossenbaccus and White 2013). Aetiological explanations and treatment options are the two most contested themes. Its history sheds light on some of the current controversies. In Norway, the public debate circles around four main themes: diagnosis, treatment, research and experience (Grue 2014).

When ME was coined as a medical diagnosis in the 1950s, it was assumed to be an infectious disease (Anonymous 1956). In ICD-10, the WHO classifies it as a somatic neurological condition of the brain (code G93.3). Many doctors (researchers as well as practitioners) refuse to accept this definition. For instance, English psychiatrists have argued that this is not an infectious disease but a case of mass hysteria (McEvedy and Beard 1970). One theory (often referred to in our data) is that ME is caused by a lack of coping with stress, which in turn makes the involuntary nervous system (with sympathicus as the main component) permanently turned on. A leading medical promoter of this theory in Norway, Professor Vegard Wyller, has used this example as illustration: when you meet a lion, your stress-level rises. When the lion goes away, it sinks. For ME-sufferers, however, the stress-level remains high, resulting in a state of sustained alert. The condition is assumed to be associated with personality traits such as ambition and perfectionism. Patients are often recommended cognitive behavioural therapy such as Lightening Process (LP).

ME is a medical diagnosis interesting in itself, but it is also interesting as a topical case of a medically unexplained low-status contested chronic condition. These conditions often have a lot in common: the disease cannot be confirmed by technological tests, the border between somatic and psychiatric disorders is in dispute, and/or problem is systemic and cannot be localized in a particular body part. Such conditions have low prestige among doctors (Album and Westin 2008). Bodily problems that are neither identified by biomarkers nor explained theoretically are often constructed as psychogenic in origin. In our society, where less physical means less real (Jutel 2011, 13), these conditions usually become contested, both within and between medical and lay entities. This contest reflects an important underlying issue: patients seek acceptance for having an actually existing disease and thus having permission to be ill (Aronowitz 1998; Nettleton 2006). As a chronic contested condition, ME belongs to a group of “conditions that escape the reality principle by apparently existing only in terms of subjective experience” (Cohn 1999, 195). A recent review of thirty-four qualitative studies about the experiences of patients and doctors in relation to ME/CFS shows that patients often feel that doctors call their moral character into question, while doubting the reality of their symptoms. Sometimes, they describe the lack of acknowledgement and understanding as even worse than the illness itself (Anderson et al. 2012).

Text number one (T1)

Text number one (T1) was posted anonymously on a privately moderated but publicly accessible Facebook-page in 2012. This page has many regular readers (about 400 followers at that time), but anyone with a Facebook account can read and write on it:

DROP YOUR DOCTOR – GET A BIOENGINEER!

ME-patient (M) at blood sampling at one of the country’s largest hospitals meets an interested bioengineer (B):

B: This was really a lot of samples …

M: Yes, it’s been almost ten years; my doctor thought it was time for a broad screening.

B: Have you considered that it might be something to do with the psyche?

M: I have a psyche, sure, don’t you?

B: Yes, it affects … um … the whole system, everything’s connected, right?

M: Sure, life wouldn’t life be boring if we didn’t have a psyche.

B: Heh heh, sure. Do you have a lot of pain? (Sniffles)

M: I particularly have a lot of headaches.

B: Headaches? Is it migraine? (Sniffles)

M: No.

B: Is it like in half your head? (Points and sniffles.)

M: No, or, yes, but it’s something I’ve had for a long time, thirty years at least. Comes and goes. But could we get those tests done soon, I’d like to get out of here, I haven’t eaten lunch.

B: Are you good at getting out for walks? (Sniffles and snorts.)

M: You know, I don’t think that question is very relevant for these tests.

B: No, sure. But because we’re talking here…

M: Well like I said, I’d like to be done here so I can get on with what it takes so I don’t get worse. I have a bit of a cold and haven’t slept well lately, so I haven’t taken as many walks as I would like. But it seems like you have a cold too?

B: Yes, I have a cold.

M: Then there’s even less of a reason for me to sit on top of you here, because I can be knocked out by a small cold.

B: Well, let’s get started then. (Sniff sniff snort. Inserts the needle and fills the first few glasses.)

M: Turns face to the side, trying to avoid cold-breath.

B: I have a friend who had pain in the whole of her body (points across the chest and both shoulders). She went to one of those lightning processes and was all better. Have you heard about that?

M: Yes, I’ve heard about that. But not everyone with pain has ME. They might think so because they’ve heard about ME symptoms.

B: Yes, yes, sure. Not everyone has ME.

M: A lot of people describe ME using symptoms that other people recognize. Then they go to the doctor and get an ME diagnosis.

B: But that headache…

M: I think I’ll discuss that with my doctor.

B: But doctors, they don’t think about the whole picture, do they?

M: The problem is that doctors don’t know much about what they can do for ME patients, but most of us get along pretty well because we learn how to impose limits on ourselves and avoid getting worse. My doctor always prefers that I talk about the psyche, because then he has something to say.

B: (straightens up, hacks and barks right into my face so that I have to turn away again). Yes, it’s not easy to get any services, is it?

M: But I like to take walks and a lot of other things, so to the extent that I can stay away from the things that make me worse, I do that. That helps both the psyche and sleep and most other things.

B: Brightens (I’d finally understood something).

B: (Straightens up): Have you thought about who’s going to pay for all these tests?

M: The national insurance scheme.

B: (nods tellingly) Yes then it’s best to take a lot of tests while we’re at it. (We finally agree on something.)

M: Sorry if I seem irritated, but the thing is that most ME patients do quite well once they’ve had some experience with the disease – even though it’s mostly about pulling yourself by your own hair. What you need is a few helping hands, to be stroked with the grain and help to get over a few bad spells, then it’s easier to use what normalcy you have.

B: (Brightens up again.) Yes, everybody has their problems, right?

M: Sure, but there’s something particular about a disease where you constantly feel like you’re going to die.

B: Oh, that must be very exhausting. (think, think).

M: Yes, it becomes a habit to start again each day, and pull yourself by the hair. Then it’s a little annoying with people who’ve read some newspaper or seen something on TV – we are actually quite interested in becoming well, so we do pay a lot of attention to what’s available. What we don’t need is suggestions like: Couldn’t you pull yourself even harder by the hair, and then you’ll surely get out of that quagmire.

B: Oh sure, sure, I understand that. (The glasses are full and I’m told to press on the cotton ball until she can tape it.)

M: (On the way out, an hour and a half on overtime – pets her on the arm.) I understand the good intentions, but you know nothing about ME.

B: No, no, I guess I don’t. Good luck then! Big, moist hug.

Good thing I already have a cold. It was nice to get out into the fresh air with coffee from a thermos and carrot cake (no filling) on a bench outside with a view of the lake.

An older couple with white hair on the next bench looks like they have a lot to think about. They don’t talk, but nod a greeting. It’s hard to grow old, I think. We all have our problems.

[Norway is a lovely country, but the health services are completely messed up.]

This text is a dramatic dialogue between a bio-engineer (B) and a patient who is identified with the narrator – thereby constructing a patient-narrator (PN). The events consist of PN coming in to a hospital to have tests taken by B, the two characters discussing PN’s health situation, and PN leaving the hospital to reflect on the encounter. The scene is presented directly and with realistic dialogue but contains elements of comedy and satire. The style of the dialogues provides a sense of precise replication of experience. Unless the exchange was recorded, however, it is unlikely that each line is recalled precisely; thus the text takes on the air of a dramatic reconstruction. (One woman posted a comment to the story, saying that she doubted it had actually happened and asked from which hospital it was, but the moderator did not respond.) The use of dialogue is best described as a rhetorical device for achieving realism. Its title, “DROP YOUR DOCTOR – GET A BIOENGINEER!” borrows from tabloid headlines and motivational slogans and might be fictional, construed as a parody of the quick-fix approach advocated in the text.

On this interpretation, the text is a didactic dialogue which uses humour both for expressive and educational purposes. The character B is well-intentioned but overbearing and comes across as slightly buffoonish. The perspective is anchored with PN who also invites the greater degree of identification. B asks naïve questions. Within the narrative frame, PN answers them straightforwardly, while commenting satirically on them outside the frame. This suggests an intended readership with some familiarity with the kind of questions posed by B. To paraphrase: these are the kinds of inane questions health professionals might ask, and this is how they might be answered.

The education of B is also an education of the reader; as such the text resembles a Socratic dialogue. The reader is allowed to scoff at the ignorance of B, while simultaneously receiving answers to B’s questions. These are conventional questions about ME, likely to have been posed by many healthcare workers, family members, friends, acquaintances, and so on, of members of the Facebook group where it was originally posted. The claims made and questions posed might be paraphrased like this (quotes from T1 in brackets):

-

ME is related to some form of vague systemic imbalance (“the whole system, everything’s connected, right?”)

-

ME is primarily psychogenic in its origin (“I have a psyche, sure, don’t you?”)

-

ME is unlike other somatic illnesses in that it is not purely physical (“But doctors, they don’t think about the whole picture, do they?”)

-

ME can be cured by lifestyle changes (“Are you good at getting out for walks?”)

-

ME can be cured by quick-fix treatment programs, as demonstrated by anecdotal evidence (“She went to one of those lightning processes and was all better.”)

-

ME is not a distinct disease, because fatigue and pain are common symptoms for different conditions (“But not everyone with pain has ME”)

-

ME sufferers are whiners (“it’s been almost ten years; my doctor thought it was time for a broad screening”)

These are all familiar arguments in the psychogenic framework, which also positions ME as an instance of MUPS (Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms) – and they are disposed of in a reasonable manner by PN. At the end, B (and by implication the psychogenic explanations of ME) has been symbolically vanquished. The narrative provides a script for dealing with the impositions of others, while maintaining a sense of distance/integrity. This is potentially instructive both to patients and to health professionals – the first group learns how to deal with impositions, the second group is informed about the correct frame in which to interpret ME.

The final sentence of the text is a bald statement: “Norway is a lovely country, but the health services are completely messed up.” In rhetorical terms it might be construed as the claim for which the preceding narrative provides grounds. That the health services are “messed up” has to do with the ignorance of health professionals such as B, who ignore politeness conventions and personal boundaries, display irritating behaviour in the form of sniffles, and theorize about ME while demonstrably knowing very little about it. PN knows medical discourse better than her medical interlocutor; she eventually succeeds in convincing B that B does not know much about this particular diagnosis.

The core messages of T1 are similar to those found in several other texts in the online community. Although they vary in style and form, the second text strongly resembles the first in its content.

Text number two (T2)

Text number two (T2) was posted on an open and public website in 2011 by a woman who describes herself as “the editor” (the website contain several texts written by others):

-

MUPS: a pandemic network infection?

There is now reason to fear that a majority of participants in both the Norwegian and the international Chronic Fatigue network are suffering from the post-viral disorder MUPS.

MUPS stands for Medically Unexplained Psychosocial Stupidity, a diagnosis that is widespread in the health service throughout the western world. The condition leads to delusions, lack of empathy and selective loss of hearing and vision, affecting in particular the ability to read and take in bio-medical research literature.

Almost 1500 international studies point towards a clear causal link between an aggressive intellectual infection mechanism and this chronic and progressive complaint, which has spread from medical professors to health-service bureaucrats and health-care staff.

For the time being, it has naturally enough not been possible to isolate contagious micro-organisms in active professorial brain tissue. On the other hand, no randomized studies have been published that can disprove that known or unknown pathogens invade and infect academic brain matter. In recent years, Norwegian research interest has focused particularly around the lion virus Panthera leo kverulantis as a likely cause of the manic MUPS condition.

Because no-one has yet succeeded in discovering a unifying, objective marker of the disease, some isolated groups of researchers still claim that MUPS is a functional disease. Others suggest that MUPS is caused by mass hysteria and that people with unrealistic ambitions and authoritarian personality features are particularly susceptible.

An increasing number of MUPS researchers, however, base their studies on irrefutable, academically-formulated theories that one or more pathogens trigger a genuine and serious illness in the brain of particularly susceptible individuals, particularly within the health sector. In Norway it is thought that the contagion attacks the area of the hypothalamus, to which it apparently attaches itself in autonomous, bow-shaped drapes which presumably maintain the condition even once the lion virus has been defeated.

Those infected with MUPS are supporters of Erasmus Montanus and believe in “sustained arousal.” Recent British research holds out the hope of partial recovery or, at any rate, an improved ability to cope with the help of cognitive therapy (pure thoughts) and graduated self-training (cold showers). Lightning Process or other illumination is also recommended.

This text was shared on several internet fora the same day, for instance by a woman who described the text as “a really witty thing, that as at least those who follow all the noise surrounding ME, and what kind of illness this really is, would understand at once.” Amongst the comments to this posting was a woman who wrote: “ha-ha, splendid humour.”

The text is a chronicle posted on the internet by a woman with ME. In the text, however, she writes in an indirect style, using passive verb forms, language and clauses without subjects. The text approximates medical discourse by its authoritative, distanced and objective writing style and by the use of medico-scientific vocabulary, syntax and voice to re-contextualize the abbreviation MUPS from conventional medical discourse into a comic parody. To understand the text, you need to know that the term Medically Unexplained Physical Symptom is used to describe physical conditions where no disease (no biological markers) can be identified in the body by the use of technological (assumed objective) diagnostic tests and where causes are uncertain. Reader familiarity with the term MUPS is sufficient knowledge to establish the parodic register and to convey that the key proposition is meant ironically. However, most of the story remains untold, thus excluding readers who are unfamiliar with the topic. This indicates a specialized and highly informed intended readership, e.g. mainly people suffering from ME and healthcare workers. The intended reader will pick up on multiple inter-textual links.

The text proposes that a majority of participants in a hypothetical network of medical professionals and health bureaucrats suffer from a post-viral disorder named MUPS. This network might be read as equivalent to what ME-sufferers in the UK calls a psychiatric lobby that is “fighting the biomedical view of ME” (Invest in ME 2008). MUPS is here defined as Medically Unexplained Psychosocial Stupidity – the four letters and the first two words of the original abbreviation are preserved, thus establishing a strong connection to the medical discourse. The symptoms of the proposed disorder are described as “delusion, lack of empathy and selective loss of hearing and vision” which coincides with the view of health professionals presented in T1. The proposed cause of the disorder is a “lion virus,” “Panthera leo kverulantis” which combines the name of the animal used to explain the psychogenic theory of sustained arousal with a pig Latin word for querulous or quarrelsome, playing on medical stereotypes about “difficult” ME patients.

By the use of analogic arguments and reductio ad absurdum, the author posits that the chronic fatigue network suffers from a medically unexplained condition with psychosocial stupidity as the main symptom, accompanied by delusions, lack of empathy, selective loss of hearing and vision, cognitive problems and learning difficulties. This demonstrates the futility and stupidity of medical explanations that are neither empirically nor theoretically founded in scientific knowledge. The claim that the network suffers from a spurious post-viral disorder named MUPS is absurd, which implies that the original MUPS-concept should be thought about in the same way. As in T1, medical discourse itself is being interrogated though the formal features and content structure of this text is even more elaborated than in T1.

In the last paragraph of the text, the author describes those infected (again, a medical concept) by MUPS as supporters of Erasmus Montanus, the eponymous character of the 1722 Ludvig Holberg play, a well-know text in the Norwegian canon. Erasmus is a university-trained philosopher who “proves” a number of absurdities through the faulty application of logic, thus antagonizing his uneducated but commonsensical friends. The play is about academic conceit with Erasmus bearing a passing resemblance to some of the characters from Lewis Carroll’s Alice novels, including the Caterpillar, the Hatter and Humpty Dumpty. To characterize MUPS-supporters as followers of Erasmus is not only to call them misguided but also to criticize their way of applying academic knowledge to the world.

The text is illustrated by a collage (not presented here) featuring a smiling professor Wyller in his white coat, flanked by two lions. The lions literalize his example of the workings of sustained arousal theory – thus turning it slightly absurd because ME is hardly triggered by actual lions. Both text and illustration function as a way of mocking the medical community for their arrogant, simplistic and speculative way of describing and explaining the physical problems of people with ME. They give voice to critical attitudes toward psychogenic understandings of their disease; at the same time as they support and motivate ME-sufferers who feel stigmatized by these explanations. Through the ironic and satiric tone of the text and its illustration, the author presents herself and the community she represents not as whiners but as people with humour, wit, and superior understanding of their condition.

In terms of argumentation, the text works through presupposition and implication. The figure of the ‘infected network’ of doctors is an allegory for the patient community. If what is posited about the network of doctors is clearly unreasonable and there exists a presupposition that the network of doctors is actually the network of patients, then by analogy similar suppositions about patients must also be unreasonable. The author thus manages to tell a story without explicitly telling it. This implicit meaning is neither hidden nor secret, but it depends on already existing familiarity with the topic at hand. The text tells its real story only to readers who are already convinced and in the know; it does not aim to win new converts. The arguments solidify the virtual symbolic community without necessarily extending it.

The discursive generation of a social movement online community

By writing and posting text and images on websites open to public debate, people suffering from ME in Norway create and sustain a social movement online community. The textual representations of this community, of which we have given two examples, exhibit considerable symbolic complexity regarding both form (style, tropes, and devices) and explicit content. However, they convey the same main messages. Through their explicit and implicit arguments, they reveal adherence to a shared definition of the situation: health professionals who explain ME as triggered by psychogenic factors are out of touch with “reality” by failing to see the “true” somatic origin of this disease. The psychogenic way of understanding ME is not only wrong but also stupid. Health professionals who think otherwise are mistaken or as hinted to in T2, suffering from “delusions, lack of empathy and selective loss of hearing and vision, affecting in particular the ability to read and take in bio-medical research literature.” They present counter-arguments to the psychogenic explanatory model, while countering normative expectations to how they ought to manage their illness.

Both texts function as a way of exercising counter-power (Foucault 1980) – to contest (as with T1) or to appropriate and subvert (as with T2) the language of medical power. By positing a lack of knowledge among healthcare workers, the authors fight for their right to define their condition themselves. This is a common feature of online communities for people suffering from medically contested conditions. Some of them promote a medicalized understanding of their condition (Dumit 2006; Fair 2010; Barker 2008; Ziebland and Wyke 2012). Others promote a de-medicalised understanding (Crossley 2004; Gavin 2008). Still, their main purpose is the same: to contest current medical definitions and present alternative views.

In both our texts, the core messages are presented in a subtle and humorous way-- through naïve and ironic statements. The authors deploy humour, parody, pastiche, irony and satire either to identify or construct contradictions in hegemonic narratives (T2) or, as in the straightforward narrative (T1), to establish the patient-narrator as the heroic subject of a self-authored story – as opposed to the passive subject of medical control.

Regardless of motives, about which we know nothing, the use of humour in communication has various social functions, depending on the context in which it is created and interpreted: humour might function as motivation, identification/differentiation, encouragement, resistance, control, persuasion, tension relief, and – of course – amusement (Lynch 2002). Its functionality relates to its consequences and must not be confused with the actor’s motives. As a functional element, humour can contribute to create, maintain or change any social system. In our case, the humour seems to have three functions that are closely entwined: identification, motivation and resistance. These functions are related to a salient rhetorical device used in both texts: the use of the we-and-they schism. Within this schism, both authors write from a confident authoritative position while using superiority humour containing mockery, disdain and making fun of others’ inadequacies. Through their satiric writing, they mock health professionals who support a psychogenic view of ME. Their message reads: as community members, we are strong people who ought to stand up, as a group, to fight against powerful doctors and others who present this view. This we-and-they schism is connected to the basic structure of the plot in their story, which is a classical hero-and-villain structure. The authors clearly identify the main actors in this plot: patients are heroes; doctors are villains (because they do not accommodate the views of their patients). By doing so, the authors create an in-group cohesiveness and boundaries that serve to demarcate their community against health professionals, whom they construct as their counterpart and enemy number one (‘we’ stand in opposition to ‘they’).

Another interesting observation is the ways in which the texts (especially T2) display familiarity with the idiom of medical science, while at the same time criticizing its arguments and positions. While writing from a confident authoritative position, the author of T2 defines MUPS as a post-viral disorder, and by referring to previous research, she explains its symptoms, cause, epidemiology and treatment. By approximating a medical discourse in order to subvert it, the texts (re)appropriate the authority of medical science.

Both our texts seem to be addressed primarily to people who are already acquainted with the ME-debate, which would be mainly community members, members of the larger social movement, and health professionals. If this is their intended readership, the texts serve both internal and external functions. An external function could be to influence the ways in which health professionals describe, explain and treat ME-sufferers who seek their help. The most significant internal functions could be to generate and consolidate a normatively integrated social movement online community and to contribute to an international social health movement.

The view on ME presented in our two texts is in accordance with the views of formal patients’ organizations, nationally and internationally, including The European ME Alliance (EMEA). All member organizations in this alliance have agreed to “promote the fact that ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis) is a neurological illness” and endorse the principles of the 2003 Canadian consensus criteria for diagnosis and treatment for ME, which represents a somatic understanding of ME (European ME Alliance 2014). The two texts can therefore be seen as embedded within a wider international social health movement that seeks recognition for a medically unexplained condition by constructing it as a distinct somatic disease.

While the normative foundation of the Norwegian ME-community coincides with that of the international organisation, the online debate is more confrontational. The confrontational aspect is also seen among members of “offline” support groups. Clark and James (2003) for instance have described how support groups for people with CFS/ME forged ‘radicalized selves’ as a result of their experiences of being disbelieved and discredited by the medical profession.

The satiric attacks on the medical profession seen in our two texts must be understood in relation to the stigma, disbelief and powerlessness associated with the lack of a clear and undisputed medical diagnosis.

A study of social mobilization in miniature

In this essay, we have combined rhetorical and social science concepts, theories, perspectives and methods to explore the social construction of a social movement online community through two emblematic texts. The texts illustrate how members of this community infuse it with meaning, belonging, fellowship and identity, and how they draw symbolic borders to demarcate their community against other groups. By blending humanistic and social science approaches and incorporating the overarching social, cultural and historical context in a rhetorical analysis of individual texts, we have been able to illuminate how these texts are positioned within, and inseparable from, the cultural frame of the community in which they are created and shared. This frame consists of norms, values and viewpoints that delineate the purposes and boundaries of their community. The texts derive from this frame; at the same time as they serve to reinforce and renew it. Researchers working in the medical humanities are well aware that patients draw on a rich repertoire of experiences and narrative techniques when expressing themselves; we have sought to show the social function of such rhetorically complex texts.

Together with other texts with similar views and messages, our examples contribute to the institutionalization of a social structure with shared norms and values that foster cooperation, solidarity, loyalty, support, collective identity and a feeling of belonging. In short, it leads to the creation of a social structure that qualifies as a community that enables them to stand shoulder by shoulder for a common cause: to transform doctor’s perceptions of ME from psychogenic to somatic explanatory models. This seems to be the raison d’etre of their community.

Through our narrow empirical approach we have sacrificed width and variation for depth and details. By doing so, we lose information about the variety of textual utterances within the online community. What we gain in return is a detailed textual and contextual account of two characteristic yet unique cases that illuminates the discursive generation of collective mobilization in an online community. Our two texts amount to a tiny piece of a large community, which again is only a small part of an international social health movement. Yet, they contain all the main elements a social movement contains: informal networking, collective action, collective identity and a conflict with identified opponents. Our study is therefore a study of a social mobilization in miniature.

References

Album, Dag and Steinar Westin. 2008. “Do Diseases have a Prestige Hierarchy? A Survey among Physicians 718 and Medical Students.” Social Science & Medicine 66:182-188.

Anderson, Valerie R., Leonard A. Jason, Laura E. Hlavaty, Nicole Porter, and Jacqueline Cudia. 2012. “A 720 Review and Meta-synthesis of Qualitative Studies on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue 721 Syndrome.” Patient Education & Counseling 86:147-155.

Anonymous. 1956. “A New Clinical Entity?” Lancet 267:789–790.

Aronowitz, Robert A. 1998. Making Sense of Illness: Science, Society and Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Banks, Jonathan and Lindsey Prior. 2001. “Doing Things with Illness. The Micro Politics of the CFS Clinic.” Social Science & Medicine 52:11-23.

Barker, Kristin K. 2008. “Electronic Support Groups, Patient-consumers, and Medicalization: The Case of Contested Illness.” Journal of Health & Social Behavior 49:20-36.

Benford, Robert D. and David A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26:611-639.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brenu, Ekua W., Lotti Tajouri, Kevin J. Ashton, Donald R. Staines and Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik. 2013. “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Parallels with Autoimmune Disorders.” In Genes and Autoimmunity, edited by Spaska Angelova Stanilova, 205–35. InTech. doi: 10.5772/53440.

Brown, Phil and Stephen Zavestoski. 2004. “Social Movements in Health: An Introduction.” Sociology of Health & Illness 26:679-694.

Brurberg, Kjetil G., Marita S. Fønhus, Lillebeth Larun, Signe Flottorp, and Kirsti Malterud. 2014. “Case Definitions for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): Asystematic Review.” BMJ Open 4. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003973.

Butler, Judith. 1997. “Sovereign Performatives in the Contemporary Scene of Utterance.” Critical Inquiry 23:350-377.

Caren, Neal, Kay Jowers, and Sarah Gaby. 2012. “A Social Movement Online Community: Stormfront and the White Nationalist Movement.” Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change 33:163-193.

Carruthers, Bruce M., Marjorie I. van de Sande, Kenny L. De Meirleir, et al. 2011. “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria.” Journal of Internal Medicine 270: 327–338.

Clarke, Juanne N. and Susan James. 2003. “The Radicalized Self: The Impact on the Self of the Contested Nature of the Diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.” Social Science & Medicine 57:1387-1395.

Cohen, Anthony P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. London: Routledge.

Cohn, Simon. 1999. “Taking Time to Smell the Roses: Accounts of People with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Their Struggle for Legitimisation.” Anthropology & Medicine 6:195-215.

Crossley, Nick. 2004. “Not Being Mentally Ill. Social Movements, System Survivors and the Oppositional Habitus.” Antropology & Medicine 11:161-180.

de Wolfe, Patricia. 2009. “ME: The Rise and Fall of Media Sensation.” Medical Sociology Online 4:2-13.

della Porta, Donatella and Mario Diani. 2006. Social Movements: An Introduction. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Dumit, Joseph. 2006. “Illnesses You have to Fight to Get: Facts as Forces in Uncertain, Emergent Illnesses.” Social Science & Medicine 62:577-590.

Edbauer, Jenny. 2005. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 35:5-24.

European ME Alliance. 2014. “About Us.” http://www.euro-me.org/about.htm.

Eysenbach, Gunther and James E. Till. 2001. “Ethical Issues in Qualitative Research on Internet Communities.” British Medical Journal 323:1103-1105.

Fair, Brian. 2010. “Morgellons: Contested Illness, Diagnostic Compromise and Medicalisation.” Sociology of Health & Illness 32:597-612.

Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Routledge.

Foucault, Michael. 1980. Power/Knowledge. New York: Pantheon.

Frank, Arthur. 2010. Letting Stories Breathe. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gavin, Jeff, Karen Rodham, and Helen Poyer. 2008. “The Presentation of “pro-anorexia” in Online Group Interactions.” Qualitative Health Research 18:325-333.

Grue, Jan. 2014. “A Garden of Forking Paths: A Discourse Perspective on ’Myalgic Encephalomyelitis’ and ’Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’.” Critical Discourse Studies 11: 35-48.

Holberg, Ludvig. 1722/2012. Comedies by Holberg; Jeppe of the Hill, The Political Thinker, Erasmus Montanus. General Books LLC: www.general-ebooks.com.

Hossenbaccus, Zahra and Peter D. White. 2013. “Views on the Nature of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Content Analysis.” JRSM Short Reports 4:1-6.

Invest in ME. 2008. “Norway Establishes ME Centre.” Accessed March 15, 2016. http://www.investinme.org/IIME%20Newsletter%20Dec%2008.htm.

Iser, Wolfgang. 1974. The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jutel, Annemarie D. 2011. Putting a Name to it. Diagnosises in Contemporary Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Keränen, Lisa. 2014. “Public Engagements with Health and Medicine.” Journal of Medical Humanities 35: 103-109.

Knudsen, Ann Kristin, Linn V. Lervik, Samuel B. Harvey, Camilla S. Løvvik, Anne N. Omenås, and Arnstein Mykletun. 2012. “Comparison of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalopathy with other Disorders: An Observational Study.” JRSM Short Reports 3: 1-7.

Kuipers, G. 2015. Good Humour, Bad Taste: A Sociology of the Joke. Berlin:Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Lenski, Susan D. 1998. “Intertextual Intentions:Making Connections across Texts.” The Clearing House 72:74-80.

Lian, Olaug S. and Bondevik, Hilde. 2015. “Medical Constructions of long-term Exhaustion—Past and Present.” Sociology of Health & Illness 37:920-935.

Lian, Olaug S. and Nettleton, Sarah. 2015. “’United We Stand’: Framing Myalgic Encephalomyelitis in a Virtual Symbolic Community.” Qualitative Health Research 25: 1383-1394.

Lynch, Owen H. 2002. “Humorous Communication: Finding a Place for Humor in Communication Research.” Communication Theory 12:423-445.

McEvedy, Colin P. and A. W. Beard. 1970. “Royal Free Epidemic of 1955: A Reconsideration.” British Medical Journal 1 (5687): 7-11.

Miller, Carolyn R. 1984. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70:151-167.

Ministry of Justice and Public Security 2013. “Lov om opphavsrett til åndsverk (åndsverkloven)” [The Copyright Act]. Accessed March 15, 2016. http://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1961-05-12-2.

Nettleton, Sarah. 2006. “‘I just want permission to be ill’: Towards a Sociology of Medically Unexplained Symptoms.” Social Science & Medicine 62:1167-1178.

Norwegian Statistics. 2015. Bruk av IKT i husholdningene, 2015, 2. kvartal [Use of IKT in households, 2015, 2. quarter]. Accessed March 15, 2016. http://ssb.no/ikthus. https://www.ssb.no/teknologi-og-innovasjon/statistikker/ikthus/aar/2015-10-01.

Radin, Patricia. 2006. “‘To me, it's my life’: Medical Communication, Trust, and Activism in Cyberspace.” Social Science & Medicine 62:591-601.

Sarangi, Srikant. 2010. “Practising Discourse Analysis in Healthcare Settings.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research, edited by Ivy Bourgeualt, Robert Dingwall, and Raymond de Vries, 397-416. London: Sage.

Scott, J. Blake. 2014. “Afterword: Elaborating Health and Medicine’s Publics.” Journal of Medical Humanities 35 (2): 229-235.

Shifman, L. 2007. “Humor in the Age of Digital Reproduction: Continuity and Change in Internet-based Comic Texts.” International Journal of Communication 23:187-209.

Vayreda, Agnes and Charles Antaki. 2009. “Social Support and Unsolicited Advice in a Bipolar Disorder Online Forum.” Qualitative Health Research 19:931-942.

Ziebland, Sue and Sally Wyke. 2012. “Health and Illness in a Connected World: How might Sharing Experiences on the Internet affect People's Health?” The Milbank Quarterly 90:219-249.

Acknowledgements

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: The Norweigan Research Council, Research Program of Health and Care Sciences (grant no. 212978 and 204324).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lian, O.S., Grue, J. Generating a Social Movement Online Community through an Online Discourse: The Case of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. J Med Humanit 38, 173–189 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-016-9390-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-016-9390-8