Abstract

Cancer screening rates among immigrant and refugee populations in high income countries is significantly lower than native born populations. The objective of this study is to systematically review the effectiveness of interventions to improve screening adherence for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer among Somali immigrants. A literature search was conducted for the years 2000–2021 and eight studies met eligibility criteria. The following intervention components were found to increase adherence to cervical cancer screening: home HPV test, educational workshop for women and education for general practitioners. A patient navigator intervention was found to increase screening for breast cancer. Educational workshops motivated or increased knowledge regarding cancer screening for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer. However, most of the studies had limitations due to methodology with potential for introduction of bias. Therefore, future studies comparing effectiveness of specific intervention components to reduce disparities in cancer screening among Somali immigrants and refugees are encouraged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast, cervical and colorectal cancer account for 24.6% of cancer diagnoses and 19.5% of cancer mortality worldwide and they are distinguished by the fact that there are cost-effective screening tests that detect cancers at earlier stages and reduce cancer-associated mortality at the population level [1, 2]. However, implementation of screening programs is distributed unequally at a global scale as well as within countries and regions [3,4,5]. In high income countries, cancer screening rates among immigrant and refugee populations is significantly lower than native born populations [6].

Somali immigrants and refugees represent one of the largest groups of African immigrants to high income nations. Refugees from Somalia began arriving in North America and Europe in the 1990’s due to a civil war in their homeland. Cancer screening disparities remain significant among Somali populations. In a clinic-based sample from Minnesota, screening rates for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer among Somali immigrants in the United States is significantly lower than for non-Somalis [5]. A study in Portland, Maine comparing Somali women with Cambodian and Vietnamese women showed Somali women were less likely to undergo recommended screenings for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer [7]. Similarly, a study on cervical cancer screening among immigrant women at an international medical clinic in Seattle, Washington showed that Somali women were significantly less likely to get screening [8]. Among Somali immigrants in Minnesota, the colorectal cancer screening rate is the lowest of any examined demographic at 35.5% as compared with 73.5% statewide [9].

Somali women in European countries also have lower screening rates as compared to the general population. In Finland, Somali women (N = 113) had an age-adjusted cervical cancer screening rate of 41% (95%CI 31.4–50.1) as compared with 94% (95%CI 91.4–95.9) among Finns [10]. In a more recent study by Idehen et al. screening participation was even lower among Somali women who were 84% less likely to undergo screening as compared to Finns [11]. Similar disparities have been noted in studies conducted in Denmark and Norway [12, 13].

Barriers to screening have been well-studied, especially among Somali women as compared to Somali men. Barriers to screening have included lack of education on screening, lack of familiarity and distrust toward the health care system, religious beliefs and fatalism, fear and embarrassment [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, the effectiveness of interventions to address known barriers and reduce cancer screening disparities among Somali immigrants and refugees have not been well-studied. To characterize the literature to date and identify evidence gaps, we conducted a systematic review to evaluate interventions aiming to improve adherence to screening for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer among Somali immigrants or refugees in the United States and Europe.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to a protocol established a priori and is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement (PRISMA) [25]. The PRISMA checklist is provided in the Appendix A [26].

Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of several databases from January 1, 2000 to January 28th, 2021, in English language, was conducted. This time period is when a large Somali immigrant population resettled in Minnesota. This search was updated on January 17, 2022. The databases included Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by a medical reference librarian with input from the study investigators. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for screening interventions for colon, breast, and cervical cancer for adult Somali immigrants. The actual strategy listing all search terms used and how they are combined is available in the Appendix B.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria included studies that evaluated interventions for breast, cervical and/or colorectal cancer screening in Somali immigrant population. Eligible study designs were randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies with comparator arms that were available in full text in English. Study population was adult ages 21 years and above since cervical cancer screening starts after age 20 in many countries [27, 28].

Data Extraction

Two reviewers [AM and VS] independently screened studies for inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies retrieved through the search strategy. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by the reviewers, but an independent arbitrator was available for further review, if necessary.

A data abstraction table was developed to extract the characteristics of the eligible studies and information about the effectiveness the interventions. The data collected included: author(s) and year of publication; study design; intervention component(s); malignancy targeted; population; sample size of Somali participants; age and sex; screening adherence rate for controls, and screening adherence rate for intervention group. This table was created and reviewed by the reviewers prior to abstraction. Two reviewers [AM and VS] abstracted all data and all authors independently reviewed all data. If clarification of data was needed, the primary author of the included study was contacted by e-mail. No assumptions were made about any missing or unclear information.

The effect size quantified the magnitude of difference between two groups or a single group pre/post-intervention. The effect size was also presented as the percentage point difference between two groups, or the percent change from baseline of a single group. Effect measurements presented in terms of statistical significance (p-values) were also reported.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias assessment was conducted using the RoB 2: A revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials and risk of bias in non-randomized studies-of interventions (ROBINS-I) for the observational studies [29, 30].

Data Synthesis

We pursued a complex intervention synthesis in which the goal was to identify the components of intervention that are likely effective so that they can be incorporated in future interventions [31]. Data were insufficient for meta-analysis and were reported narratively. High level of heterogeneity was assumed due to differences in study design and the limited number of studies included. Synthesis was stratified by interventions (comparative vs. non-comparative).

Certainty in the Evidence

We used the grading of recommendation, assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) approach to rate certainty in the evidence following a framework tailored for scenarios in which a meta-analysis is not feasible [32].

Patient and Public Engagement

One investigator (AM) represented the population addressed in this systematic review and provided the population perspective when developing the protocol and synthesis of the systematic review [33].

Results

Search Results and Included Studies

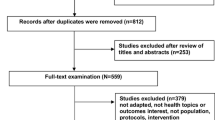

Out of 42 studies screened from five databases and registers, eight studies met eligibility criteria and were included (Fig. 1). Studies without an intervention component (n = 31) were excluded. Publications including preliminary data from studies included in the review (n = 2) were also excluded. Included studies were published between 2013 and 2021.

Study Characteristics

Five studies were conducted in the United States and three studies were conducted in Norway. Two were randomized controlled trials and six were non-randomized studies. Four studies addressed only cervical cancer screening interventions, two studies evaluated interventions for cervical and breast cancer, one study was only on breast cancer screening, and one study evaluated a colorectal cancer screening intervention. A total of 31 Somali men and at least 3,689 Somali women were included. One study had a mixed immigrant population grouping women from Somalia, Pakistan and Poland [34]. Study characteristics and outcomes are presented in Table 1. The results of the risk of bias assessment are shown in Table 1 and details of the assessment results are shown in Appendix C.

Interventions

All studies showed an improvement in at least one measure related to adherence to cancer screening in the intervention group. Four studies showed that the interventions were effective in increasing cancer screening uptake (breast and cervical cancer), three studies showed that study participants were motivated to get screening (breast and cervical) and one study showed increased understanding of the benefits of screening (colorectal cancer).

-

1.

Comparative studies

-

•

A RCT conducted by Sewali et al. in the United States showed that women who received an at-home HPV primary test for cervical cancer screening were more likely to complete cervical cancer screening than those who received a Pap smear in the clinic [OR 14.18 (95%CI 2.73–73.51)] [35].

-

•

A cluster RCT conducted by Møen et al. in Norway showed that an educational intervention for primary care providers resulted in an increased odds of patients being screened for cervical cancer among patients in the intervention region [OR 1.24 (95%CI, 1.11–1.38)] compared to standard of care, adjusting for baseline screening rates [34]. For women from Somalia, Pakistan and Poland, the odds of screening was higher post-intervention among previously unscreened participants, OR 1.74 (1.17–2.61). Participants from these countries were combined in the analysis due to the low number of women from Somalia and Pakistan. Also, for that immigrant population, when further adjusted for patient and GP characteristics, the model still showed an effect but lost statistical significance (OR 1.54 (0.99–2.40).

-

2.

Non-comparative studies

-

•

Nakajima et al. evaluated an educational intervention with a video on colorectal cancer screening presented to 31 Somali men with baseline screening status 26% screened [36]. This study had a one-group pretest–posttest design. Post-intervention survey showed a positive change in understanding cancer risk (80%) and benefits of CRC screening (90%), (50%; P = 0.012, P < 0.001, respectively). Also, 93% of participants agreed that the video contained useful information.

-

•

A retrospective cohort study conducted by Percac-Lima et al. evaluated a patient navigator intervention in the United States. The study showed that unadjusted mammography screening rates increased to 87.5%, from a baseline of 46.4% among Somali women [37]. Prior to implementation of the patient navigator intervention, adjusted mammography rates were lower among refugees including Somali, Serbo-Croatian, and Arabic-speaking women, (64.1%, 95%CI 49–77%) compared to English-speaking (76.5%, 95%CI 69–83%) and Spanish-speaking (85.2%, 95%CI 79–90%) women. Post-intervention adjusted screening rates in refugee women (81.2%, 95%CI 72–88%) were similar to the rates in English-speaking (80.0%, 95%CI 73–86%) and Spanish-speaking (87.6%, 95%CI 82–91%) women.

-

•

Pratt et al. conducted a qualitative study with a pre/post-intervention survey on a three-hour-long religiously tailored workshop on breast and cervical cancer [38]. The workshop included videos and discussion with 30 Somali women and 11 imams (Muslim religious leaders). Post-intervention, 30/30 (100%) of women reported that they were more likely to get mammogram or Pap smear (baseline 16/30 overdue for mammogram and 11/30 overdue for Pap smear). However, 28/30 planned to get screening vs. 24/30 pre-intervention (p-value 0.13).

-

•

Qureshi et al. studied an educational presentation with multiple components (oral, video, demo of equipment, appointment scheduling, etc.) presented to Somali women in Norway [39]. The study was initially designed as a cluster RCT but converted to pre-post intervention survey design due to concerns about contamination. Authors noted that the Somali immigrant population would meet each other relatively frequently, more so than the majority population. Additionally, immigrant households were finely dispersed across the study area, adding to the challenge of cluster randomization. Following the intervention, 116/128 (90.6%) Somali women said that they would contact their health care provider to get screening.

-

•

Qureshi et al. was a follow up prospective cohort study on the same educational intervention from Qureshi et al. [39]. However, this study was examining the screening status of women in the four geographical areas where the intervention was held versus the control area, which was the city of Oslo, Norway. The proportion of Somali women screened in the intervention areas increased by 0.06 (95% CI; 0.02–0.10) in the 3 years post intervention [40].

-

•

Watanabe-Galloway et al. was a qualitative study on a 2 day educational workshop on breast and cervical cancer screening. Post-intervention, 43/43 (100%) of women were motivated to talk to their health care provider about cancer screenings [41].

Risk of Bias and Certainty in Evidence

Due to variations in outcome measures, the results could not be combined to perform a meta-analysis. The risk of bias was low in the two randomized controlled trials but moderate or high in the non-randomized studies. The certainty in the evidence derived from the two RCTs supporting an effect of the intervention on measures related to cancer screening adherence was judged to be moderate. The intervention components applied in these trials were educational intervention targeting physicians and home test kit for HPV.

Patient and Public Engagement

Of the eight studies, six studies engaged patients in the research process.

-

1.

In Moen et al. immigrant women were not engaged during the study [34].

-

2.

Sewali et al. collaborated with Somali community partners to develop culturally appropriate study materials [35].

-

3.

In Nakajima et al. investigators shared ideas on colorectal cancer screening from the literature and community partners shared cultural perspectives [36]. Footage for the video intervention was produced at a “Somali TV” studio.

-

4.

Percac-Lima et al. engaged Somali patients and Somali speaking patient navigators in adapting study materials [37].

-

5.

Pratt et al. partnered with a local mosque to develop faith-based messaging [38].

-

6.

In Qureshi et al. a Somali female research assistant recruited participants and a male Somali nurse led the intervention [39].

-

7.

Qureshi et al. [40] was a follow-up study on the intervention in Qureshi et al. [39]. Patient and public engagement was referred to in the context of the 2019 study.

-

8.

Watanabe-Gallow et al. engaged Somali women and individuals who worked with Somali women through community organizations [41].

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of interventions to improve screening adherence for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer among Somali immigrants. All seven interventions in the included studies were found to be effective. Most interventions addressed cervical cancer screening followed by breast cancer screening and only one study focused on colorectal cancer screening. This may be due to the scant literature on perceptions of any cancer screening among Somali men and colorectal cancer screening among Somali women (Ali et al. 2021) [23, 24, 42]. Interventions targeting education on cancer screening were the most common, appearing in five of the eight included studies. The other three studies addressed health-care system navigation, religious misconceptions regarding screening tests, and one study evaluated an innovative screening method.

Educational Interventions/Workshops

Educational interventions in the included studies showed varying levels of impact on increasing cancer screening among Somalis, but all were found to be effective. In qualitative studies exploring barriers and facilitators to cancer screening among Somali women, educational interventions were the most recommended facilitators to what the study participants perceived to be a lack of knowledge of or prior experience with cancer screening [15, 17,18,19, 21, 22, 43, 44]. Education at health care centers and community centers delivered through workshops and seminars were among the recommended interventions for increasing cervical cancer screening [19]. Indeed, workshops were the most common form of education delivery among the included studies. Four of the five studies that included workshops used videos as part of the intervention. Prior qualitative studies showed that videos/visual presentations and stories from members of the Somali community were thought to be more effective than written format to address knowledge gaps [14]. A focus group participant in one study recommended, ‘[We need] videos …survivors’ stories, individuals who had colorectal cancer, and [more discussion] about how important it is to get screened … [23].’ All educational interventions had more than one component such as verbal presentations, videos, and screening equipment demonstration. This is consistent with qualitative studies where a combination of interventions addressing the multilevel barriers were thought to be more effective in increasing cancer screening among Somali women [17,18,19, 23, 45].

Religiously Tailored Messaging

One study included in this review used an intervention with religiously tailored messaging [38]. This was follow up to a focus group study with Somali women and men that showed a positive reception to faith-based messaging for breast and cervical cancer screening [44]. Another qualitative study had also recommended involving Somali community and faith leaders to address concerns about modesty and fatalistic beliefs, which have been barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening adherence [42]. Religion plays an important role in the lives of Somalis with the majority identifying as Muslim. Involving religious leaders such as imams in educational interventions can help to present screening recommendations in the context of the Islamic faith and clarify misconceptions. Religion was also seen as a coping mechanism in one study where a combination of faith and Western medicine seen as important for treatment of disease [18]. Therefore, interventions to increase cancer screening adherence would benefit from involvement directly or indirectly of religious leaders.

Healthcare System Navigator

One study included in the review evaluated healthcare system navigators to improve breast cancer screening among Somali women. Immigrant women including Somalis have reported that one of the barriers to screening is the lack of preventive care and fewer medical resources in their home countries, especially in the context of war and migration [15, 16, 46]. Navigating the health care system can be challenging for immigrants, and Somalis have noted this as a barrier to cancer screening in prior studies. One potential solution is a health care system navigator or patient navigator. In Percac-Lima et al. appointment reminders were recommended by Somali women as facilitators for mammography [37]. While concerns have been raised about the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of patient navigators [47], a recent review on the perceptions, beliefs, and barriers to cancer screening among Somalis showed that existing literature focuses on individual and community-level barriers to screening with few studies on systemic challenges such as navigating the health care system [24]. Assistance with navigating the testing process could overcome systemic barriers.

Home Testing Kits for Cancer Screening

One study included in the review showed improvement in cervical cancer screening with mailed HPV at-home test kits [48]. Howard et al. showed that immigrant women with low socio-economic status perceived self-sampling for HPV to be beneficial but were hesitant about self-sampling due to concerns such as uncertainty about correctly performing the sampling and fear of hurting themselves [43]. However, multiple studies have shown that acculturation is associated with increased knowledge and uptake of recommended screenings [7, 16]. Future studies should assess the role of home-based kits for colorectal cancer screening among Somali patients.

Patient and Public Engagement

Somali immigrants were involved at different stages of the research process in six of the eight included studies. Most of the engagement occurred during the execution phase of the research process (e.g., study design and procedures, recruitment and participation, and data collection) [33]. While this ensures completion of the studies, including patients and service users in the preparatory and translational phases of research could potentially result in sustainable interventions that address health priorities for the affected communities [33, 49].

Limitations

This review is limited by the number of published studies evaluating cancer screening interventions among Somali immigrants. Furthermore, the risk of bias was high for the non-randomized studies, which made up the majority of the included studies. Finally, we did not calculate inter-rater reliability between the two reviewers, though authors held meetings to compare findings and develop consensus.

Conclusion

The scant literature focused on interventions to increase cancer screening among Somali immigrants and refugees, points to a great need for further research to develop, implement and evaluate interventions aimed at increasing cancer screening and reducing screening disparities. Our systematic review provides a ready foundation to facilitate development of future studies to rigorously test intervention components alone or in combination. These studies are urgently needed to reduce cancer screening disparities among Somali immigrants and refugees.

References

Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Ferlay, J., et al.: Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International agency for research on cancer 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today. Accessed 25 May 2022.

Sankaranarayanan R, Budukh AM, Rajkumar R. Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(10):954–62.

Swan J, et al. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 national health interview survey. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1528–40.

Morrison TB, et al. Disparities in preventive health services among Somali immigrants and refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):968–74.

Goel MS, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–35.

Samuel PS, et al. Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening rates amongst female Cambodian, Somali and Vietnamese immigrants in the USA. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:30.

Menon M, et al. Predictors of cervical cancer screening among patients at an international medicine clinic-Seattle, WA. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15):e17632.

Measurement, M.N.C.: Minnesota health care disparities by race, hispanic ethnicity, language and country of origin. 2021. 2020 report year (2019 dates of service). https://mncmsecure.org/website/Reports/Community%20Reports/Disparities%20by%20RELC/2020%20RELC%20Appendix%20Tables%20-%20COO.pdf.

Idehen EE, et al. Disparities in cervical screening participation: a comparison of Russian, Somali and Kurdish immigrants with the general Finnish population. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):56.

Idehen EE, et al. Cervical cancer screening participation among women of Russian, Somali and Kurdish origin compared with the general Finnish population: a register-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):1–16.

Kristiansen M, et al. Migration from low- to high-risk countries: a qualitative study of perceived risk of breast cancer and the influence on participation in mammography screening among migrant women in Denmark. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23(2):206–13.

Møen KA, et al. Differences in cervical cancer screening between immigrants and nonimmigrants in Norway: a primary healthcare register-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017;26(6):521–7.

Redwood-Campbell L, et al. “Before you teach me, I cannot know”: immigrant women’s barriers and enablers with regard to cervical cancer screening among different ethnolinguistic groups in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(3):230–4.

Raymond NC, et al. Culturally informed views on cancer screening: a qualitative research study of the differences between older and younger Somali immigrant women. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1188.

Saadi A, Bond BE, Percac-Lima S. Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somali refugee women speak: a comparative qualitative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):501–8.

Ghebre RG, et al. Cervical cancer: barriers to screening in the Somali community in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):722–8.

Al-Amoudi S, et al. Breaking the silence: breast cancer knowledge and beliefs among Somali Muslim women in Seattle, Washington. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(5):608–16.

Gele AA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among Pakistani and Somali immigrant women in Oslo: a qualitative study. Int J Women Health. 2017;9:487–96.

Rogers CR, et al. A qualitative study of barriers and enablers associated with colorectal cancer screening among Somali men in Minnesota. Ethn Health. 2018;26:1–18.

Allen EM, et al. Facilitators and barriers of cervical cancer screening and human Papilloma virus vaccination among Somali refugee women in the United States: a qualitative analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(1):55–63.

Huhmann K. Barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screening in Somali immigrant women: an integrative review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47(2):177–86.

Rogers CR, et al. A qualitative study of barriers and enablers associated with colorectal cancer screening among Somali men in Minnesota. Ethn Health. 2021;26(2):168–85.

Ali MA, Ahmad F, Morrow M. Somali’s perceptions, beliefs and barriers toward breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening: a socioecological scoping review. Int J Migr Health Soc Care. 2021;17(2):224–38.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Chrysostomou AC, et al. Cervical cancer screening programs in Europe: the transition towards HPV vaccination and population-based HPV testing. Viruses. 2018;10(12):101813.

Wang W, et al. Cervical cancer screening guidelines and screening practices in 11 countries: a systematic literature review. Prev Med Rep. 2022;28:101813.

Sterne JA, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:i4898.

Sterne JA, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Viswanathan M, et al. AHRQ series on complex intervention systematic reviews-paper 4: selecting analytic approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;90:28–36.

Murad MH, et al. Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. Evid Based Med. 2017;22(3):85–7.

Shippee ND, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151–66.

Moen KA, et al. Effect of an intervention in general practice to increase the participation of immigrants in cervical cancer screening: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e201903.

Sewali BP, et al. Clinic-based pap test versus HPV home test among somali immigrant women in Minnesota: a randomized controlled trail. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(10):10.

Nakajima M, et al. A culturally adapted colorectal cancer education video for the Somali community in Minnesota: a pilot investigation. Am J Health Promot. 2021;36:514.

Percac-Lima S, et al. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1463–8.

Pratt R, et al. Testing a religiously tailored intervention with Somali American Muslim women and Somali American imams to increase participation in breast and cervical cancer screening. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(1):87–95.

Qureshi SA, et al. A community-based intervention to increase participation in cervical cancer screening among immigrants in Norway. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):147.

Qureshi SA, et al. Effect of a community-based intervention to increase participation in cervical cancer screening among Pakistani and Somali women in Norway. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1271.

Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Cancer community education in Somali refugees in Nebraska. J Commun Health. 2018;43(5):929–36.

Misra S, et al. Early challenges to engaging refugee populations in community based cancer prevention measures. Annal Surg Oncol. 2017;24(1):S90.

Howard M, et al. Barriers to acceptance of self-sampling for human papillomavirus across ethnolinguistic groups of women. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(5):365–9.

Pratt R, et al. Views of Somali women and men on the use of faith-based messages promoting breast and cervical cancer screening for Somali women: a focus-group study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):270.

Lue Kessing L, et al. Contextualising migrant’s health behaviour—a qualitative study of transnational ties and their implications for participation in mammography screening. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:431.

Percac-Lima S, Bond B, Saadi A. Bosnian, Iraqi and somali refugee women speak: a comparative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:S35.

Whitley EM. Capsule commentary on Percac-Lima et al., decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally-tailored patient navigation. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1495.

Sewali B, et al. Cervical cancer screening with clinic-based Pap test versus home HPV test among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2015;4(4):620–31.

Israel BA, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–40.

Funding

This study was funded by Primary Care in Southeast Minnesota and Mayo Clinic Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, A.A., Shah, V., Njeru, J.W. et al. Interventions to Increase Cancer Screening Adherence Among Somali Immigrants in the US and Europe: A Systematic Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 26, 385–394 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01532-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01532-y