Abstract

Parental and peer support seems to be a favourable determining factor in the acculturation process among young immigrants. We aimed to assess the level of perceived support among first- and second-generation adolescent immigrants and compare it to that perceived by the adolescents from the host population. Using Italian HBSC survey data collected in 2013–2014, first- and second-generation immigrants aged 11, 13 and 15 years were classified according to their ethnic background as being from Western countries, Eastern European countries, or from non-Western/non-European countries. The domains of teacher, classmate, family, and peer support was measured through multidimensional, standardised, validated scales. Analyses were run on a 47,399 valid responses (2195 from Western countries, 2424 from Eastern European countries, and 2556 from non-Western/non-European countries). Adolescent immigrants from Eastern European countries and non-Western/non-European countries reported significantly lower support than their peers from the host population in all explored domains. Girls perceived a lower level of classmate and family support compared to boys across all ethnic backgrounds. We observed two different immigration patterns: the Western pattern, from more affluent countries, and the Eastern pattern. Among the latter, second-generation immigrants showed the lowest level of support in all domains. Increasing family connections and developing peer networks should favour the acculturation process among adolescent immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, Italy has been a hub for large waves of immigration. As a result, public debate on immigration has mainly focused on the perceived consequences of these waves: increases in crime, the financial burden placed on hosting communities, and the extreme health and social problems immigrants face upon arrival in Italy. However, other important aspects of immigration are not being addressed. As in other European countries, in recent years an increasing proportion of adolescents have either immigrated themselves, or were born to immigrant families. Indeed, first- and second-generation immigrants represent 9.2% of the school population in Italy [24], a number that will likely stabilize in the next years [22]. Just like native-born adolescents, immigrant youth have to cope with a set of developmental tasks, such as academic achievement at school; social relationships with teachers, family, and peers; and their own psychological well-being [29]. However, adolescent immigrants are also faced with the challenge of their ‘acculturation process’, which is defined as the intersection of two cultures and can induce different outcomes: integration, assimilation, separation, or marginalization [3,4,5]. Immigrants who maintain an interest in the aspects of their culture of origin but still participate in the culture of the host country experience less psychological stress and have a greater possibility of integration. On the other hand, those who show only modest involvement in their culture of origin and have little interest in sharing the values of the host country experience greater mental health problems [23] and are at greater risk of individual and social marginalization [6, 20].

One of the biggest challenges host countries face with respect to young immigrants is reducing their risk of marginalization, which can occur for any combination of economic, social, and cultural reasons. Social support has been recognized as a factor that better predicts future success in the acculturation process [8, 9]. Social support is defined as a range of interpersonal relationships or connections that have an impact on an individual’s functioning [2]. Adolescents usually identify members of their family, school teachers, classmates, and other peers as the foundations of their social support system [1, 18, 40, 41].

Two hypotheses have been raised to explain the link between perceived social support and individual well-being. The ‘main effect hypothesis’ suggests that social support has a direct impact on well-being, independent of exposure to stressors. In contrast, the ‘indirect (buffer) hypothesis’ suggests that the effect of social support increases with increasing exposure to stressful events. Both mechanisms seem to be of importance for adolescents belonging to ethnic minorities [13, 41]. Social support in everyday activities has also been reported to be crucial for the development of prosocial behaviours, such as sociability, shyness-inhibition, cooperation–compliance, and aggression–defiance, as well as for the quality and functioning of social relationships [11]. Prosocial behaviours have been described as essential in the social adaptation process, which develops when there is congruence between the demands of the ‘ecological niche’ one belongs to and the nature of perceived social support. When this congruence does not exist, the risk of individual vulnerability and social marginalization increases [35, 36]. Thus it is clear that social support is important in an adolescent’s life, but there is a lack of information on perceived level of social support, i.e., how much support adolescents believe they have in their network.

In this age, schools represent an ideal setting to investigate, describe, and understand differences between native-born and immigrant populations, such as differences in health conditions and outcomes in order to decrease inequalities, and differences in protective factors like the quality of relationships with peers and ‘significant’ adults, whose perceived lack of support may drive immigrants to the margins of society, hampering their possibility of integration [26]. Therefore, we aimed to assess the level of perceived support among first- and second-generation adolescent immigrants and compare it to that perceived by the adolescent host population.

Methods

Study Population

This investigation is based on data from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study, a World Health Organization Collaborative Cross-National Survey which runs every 4 years. In 2014, it included 43 different countries across and outside Europe [17]. Within the framework of the HBSC, data are collected through standardized, self-administered questionnaires that include questions on social background, health behaviours, and outcomes. Anonymity and confidentiality of all participant is ensured [15]. The present analysis includes data from the Italian HBSC survey carried out in 2013–2014.

A representative sample of 47,799 students aged 11, 13, and 15 years was recruited from 3681 school classes throughout Italy (overall response rate: 90.1%). School was the primary sampling unit, drawn by systematic cluster sampling from a list of all public and private schools, which was obtained from the Ministry of Education. Participation was voluntary, and parental opt-out consent was obtained. A recognised Ethics Committee approved the national research protocol. A detailed description of the aims, theoretical framework, and protocol of the international HBSC study and its Italian component can be found elsewhere [10, 15].

Measurement

Categorization of First- and Second-Generation Immigrants and Ethnic Background

Within the framework of the HBSC, adolescents were asked where they, their mothers, and their fathers, were born. Previous research has indicated that adolescents in our target age group provide valid responses to these questions, with an agreement between the answers of adolescents and their parents of more than 99% [25]. Adolescents were classified as being from the “host population” if both parents were born in Italy; as “first-generation immigrants” if they were born abroad and at least one of their parents was born abroad; and as “second-generation immigrants” if they were born in Italy and at least one of their parents was born abroad [10].

Ethnic background was defined as the mother’s country of birth. However, if mother’s country of birth was missing or she was born in Italy, father’s country of birth was used. Based on this information, adolescent immigrants were categorized into the following ethnic backgrounds:

-

Western Countries (n = 2195) when coming from EU-15 countries (EU member states prior to May 2004), plus Switzerland, Norway and Iceland. It further includes United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zeeland, all classified by the International Monetary Fund as advanced economies countries;

-

Eastern European countries (n = 2424) when coming from the EU-13 countries (new member states joining the EU after May 2004), plus Albania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Moldavia, Serbia and Ukraine;

-

Non-Western and non-European countries, when coming from Africa, South or Central America and Asia.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured according to the Family Affluence Scale (FAS), a reliable indicator of family wealth. The FAS was developed for the HBSC study, given the known difficulties when asking young people to accurately detail their parents’ occupation or family income [16]. The scale consists of six items, including family car ownership, whether adolescents have their own bedroom, number of holidays trips taken in the last year, number of computers owned by the family, dishwasher ownership, and number of bathrooms in the home [37]. The obtained score (0–13) was recorded in a 3-point ordinal scale and categorized as low (0–6), medium (7–9), and high (≥ 10) family affluence [15].

Teacher and Classmate Support

The domain of teacher support was measured by three items in the questionnaire: (1) “I feel that my teachers accept me as I am”, (2) “I feel that my teachers care about me as a person”, and (3) “I feel a lot of trust in my teachers”. The domain of classmate support was measured by the items: (1) “The students in my class enjoy being together”, (2) “Most of the students in my class are kind and helpful”, and (3) “Other students accept me as I am”. Response categories for all the above items ranged from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Original codes were reversed (strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4) and a sum-score was generated for each domain (range 0–12) and then divided by three. The resulting average score was categorized as low (< 2.5) or high (≥ 2.5) teacher/classmate support [39]. Missing data for one or more items was coded as missing for that domain.

Family and Peer Support

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support was used to measure family and peer support [42, 43]. Family support was measured by four items in the questionnaire: (1) students were asked whether they felt that their family really tries to help them, (2) whether they could get emotional support from them when they needed it, (3) whether they can talk to their family about problems, and (4) whether their family is prepared to help them make decisions. Peer support was also measured by four items: (1) adolescents were asked if they perceived that their friends really try to help them, (2) whether they could count on them when things go wrong, (3) if they have friends with whom they can share their sorrows and joys, and (4) whether they can talk to them about their problems. Response options for both these domains ranged from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7). A sum-score was calculated for each domain (range 4–28) and divided by four. Missing data for one or more items were coded as missing for that domain [38].

Findings presented here are categorized as low/high perceived family support; those who scored less than 5.5, as in the International HBSC Report [21] according to [7, 43], were categorized as low.

Statistical Analyses

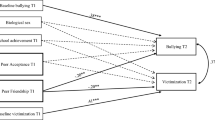

Descriptive analyses and comparisons of adolescent immigrant sub-groups by gender, age, FAS category, and social support were performed by the corrected weighted Pearson Chi square statistic. A multivariable logistic regression model for the whole sample was used to fit the association between each type of support (teacher, classmate, family, and peer), dichotomized into low vs. high (reference category) as a dependent variable, and ethnic background (reference category is the host population) as an independent variable, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, and FAS category). Logistic regression was then carried out within each category of gender and age to examine the pattern of different types of support across ethnic backgrounds, controlling for all other independent variables (gender, age, SES, and being a first- or second-generation immigrant).

The influence of being a first- or second-generation immigrant was evaluated by performing several multivariable logistic regression models combining Eastern European countries and non-Western/non-European countries, which showed similar results. All analyses were conducted taking into consideration the effect of the survey design (including stratification, clustering, and weighting) and using STATA v14.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP); a statistical significance level of 5% was used.

Results

In total, 47,799 students completed the questionnaires. An absolute number of 400 students had missing data on ethnic background (1%), therefore the final available sample consisted of 47,399 students, 86.6% from the host population and 13.4% first- or second-generation immigrants (4.0% from Western countries, 4.1% from Eastern European countries, and 5.3% from non-Western/non-European countries).

We observed a similar gender distribution in the host population and other ethnic backgrounds (p = 0.68), but significant differences for age (p < 0.0001) and FAS category (p < 0.0001) were observed. Compared to the host population, adolescent immigrants from Eastern Europe and from non-Western/non-European countries were younger (more 11-year-olds) and more likely to have a lower FAS category, whereas students from Western countries showed higher FAS scores (Table 1).

Significant differences between first- and second-generation immigrants were found by age and FAS category within each ethnic background. Second-generation immigrants of non-Western ethnic backgrounds were younger (p < 0.0001) than their first-generation counterparts and their FAS category was higher. As for students from Western countries, their FAS category was higher among first-generation immigrants, but the proportion among first- and second-generation was differently distributed across generations, as the second generation consisted of more youths, over 2000, when compared to the first generation (Table 2).

Overall, adolescent immigrants from Eastern European countries and non-Western/non-European countries reported significantly lower social support than their counterparts from the host population in all explored domains; for adolescents from Western countries, results were all nonsignificant, with the exception of overall teacher support [odds ratio, OR 1.22 (95% confidence interval, CI 1.04–1.45)] (Table 3).

Levels of teacher support did not differ by gender, or by ethnic group, although girls reported more support than boys. Among boys, those from non-Western/non-European countries showed the lowest teacher support [OR 1.41 (1.15–1.73)], followed by those from Eastern Europe [OR 1.25 (1.00–1.57)]. Adolescents from Western countries did not show any significant difference in this domain.

Adolescent immigrants from Eastern European countries showed the lowest levels of classmate and peer support [OR 1.62 (95% CI 1.38–1.91) and OR 1.52 (95% CI 1.29–1.80), respectively], while those from non-Western/non-European countries were likely to report lower family support [OR 2.05 (95% CI 1.73–2.42)]. The figures observed for teacher support were somewhat different, as both non-Western adolescent immigrant groups presented the same risk of reporting low support [OR 1.34 (1.16–1.56)], see Table 3. Girls reported a low level of classmate and family support more frequently and across all ethnic backgrounds. Girls from both Eastern European countries and non-Western/non-European countries showed significant, higher risks of poor classmate support [OR 1.70 (95% CI 1.36–2.12) and OR 1.38 (95% CI 1.13–1.69), respectively] and family support [OR 1.90 (95% CI 1.52–2.38) and OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.69–2.60), respectively] compared to girls from the host population. Boys from non-Western countries also reported lower levels of classmate and family support compared to their counterparts from the host population; differences were also significant in non-Western ethnic groups for family support [OR 1.60 (95% CI 1.26–2.04) for adolescent immigrants from Eastern European countries and 2.00 (95% CI 1.57–2.55) for those from non-Western/non-European countries], but estimates for classmate support were only significant for boys from Eastern Europe [OR 1.53 (95% CI 1.21–1.94)]. Neither girls nor boys from Western countries were different from the host population in any of these domains.

The likelihood of having low peer support compared to the host population was higher among adolescent immigrants from Eastern Europe [OR 1.55 (95% CI 1.27–1.90)] and among boys from non-Western/non-European countries [OR 1.35 (95% CI 1.09–1.67)]. Girls from these same ethnic groups were more likely to report lower peer support compared with their female counterparts in the host population [OR: 1.41 (95% CI 1.14–1.75) for girls from Eastern Europe and OR 1.30 (95% CI 1.05–1.60) for girls from non-Western/non-European countries]. As for adolescent immigrants from Western countries, our findings showed no significant differences with respect to the host population.

As for age groups, our findings did not show any significant difference between adolescents from Western countries and Italian adolescents for any of the investigated domains. However, when the host population was compared with 11, 13, and 15 year-old adolescent immigrants from Eastern Europe, the latter reported lower levels of classmate support [OR 1.82 (95% CI 1.40–2.37), OR 1.38 (95% CI 1.06–1.79), and OR 1.71 (95% CI 1.24–2.34), respectively]. These same groups presented the lowest level of peer support [11 years: OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.18–1.95); 13 years: OR 1.53 (95% CI 1.14–2.05); and 15 years: OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.08–2.11)], significantly lower teacher support among 13-year-olds [OR 1.47 (95% CI 1.15–1.88)], and lower family support for 13- [OR 1.70 (95% CI 1.33–2.17)] and 15-year-olds [OR: 2.85 (95% CI 2.08–3.90)]. Significantly different results by age between the host population and adolescent immigrants from non-Western/non-European countries were revealed only the domain of family support [OR 2.06 (95% Ci 1.54–2.75) for 11 years, OR: 2.06 (95% CI 1.55–2.74) for 13 years, and OR: 2.0 (95% CI 1.47–2.71) for 15 years].

Adolescent immigrants from Western countries did not show any significant differences with the host population, except for a higher probability of low perceived teacher support [OR 1.22 (95% CI 1.09–1.36)], whereas both generations of adolescents from Eastern European countries and non-Western/non-European countries showed significantly lower support than their counterparts from the host population in all explored domains (Table 4).

Discussion

Social support has frequently been considered as a potential moderator of the effects of environmental and social stress on individual well-being among both host and immigrant populations, particularly in adolescence [26]. Therefore, the broader scope of this work was to assess the level of support perceived by adolescent immigrants as compared with that perceived by the adolescent host population, and to highlight any differences that could be addressed through interventions.

Our results show that there is an increasingly diverse population in Italy; 13.4% of students aged 11–15 years attending compulsory school are first- or second generation immigrants. This percentage is nearly 4% higher than that observed by the Ministry of Education in 2014, the same period as our study [24]. The reason for this gap lies in the classification procedures adopted. Following the principles of the “iure sanguinis” law, the Ministry classifies children born in Italy as Italian citizens if they have at least one Italian parent. While, according to the HBSC international protocol, and as suggested by other epidemiological studies, we classified children born in Italy with one immigrant parent as second-generation immigrants [14, 34].

According to the FAS categories and age distribution of our first- and the second-generation immigrants, our results identified two immigration patterns. A Western pattern, encompassing immigrants from the Unites States, Australia, and Western European countries; and an Eastern pattern, encompassing people from Eastern European countries and other countries outside Europe (Africa, Asia and South America). According to the FAS categories, compared with the host population there were more first-generation adolescents from Western Europe and North America in the highest social classes, but this was not true for second-generation adolescents, for whom FAS categories of Western European and North American adolescents overlapped with those of the host population. This picture reflects a migration profile that can be attributed to familial business needs, and short-term residence. Instead, the profile for adolescents from Eastern European countries, Africa, Asia, and South America showed a prevalent distribution in the lower social classes, which improved in the second generation. These two patterns likely indicate a different migration impulse and a different desire to remain in the host country.

There were more second-generation immigrants from Eastern Europe in the youngest age groups, representing the stabilization of a more long-standing immigration flux. This image is coherent with the one presented by the Ministry of Education, in which an increased immigrant presence in first- and second-level primary schools [24] was described in the last 10 years. We argue that it is important to study and discuss all the effects of immigration, and to take into account the presence of these different migration profiles.

It is worth noting that, although there was consistent similarity in all areas of perceived support in the comparison between the Italian adolescents and those from Western countries (with the exception of teacher support), when compared with adolescents from Eastern European countries, much greater differences appeared. Adolescent immigrants from East Europe and from non-Western/non-European countries showed the highest risk of feeling a low level of support in all the domains we investigated, in particular in the level of perceived family support; and these differences became more marked with increasing age. These profiles are coherent with those reported in other studies [9, 26], and can be explained by the discrepancy in the acculturation processes of parents and their children. Immigrant youths tend to acquire the host country’s culture much faster than their parents do, resulting in discrepancies in values between young boys/girls and their families [12].

This so-called “acculturation gap”, together with other immigration-related stressors (e.g., financial, occupational, or social stressors), can set the stage for generational conflict, lowering the likelihood of perceiving one’s family as supportive [12, 28, 33]. However, in contrast to previous studies, our results depicted two profiles of immigration, in which the acculturation gap seems to have a different impact.

For first- and second-generation adolescents from Western countries, perceived support from peers, classmates, and family members was similar to that reported by adolescents from the host population, though it was lower in second-generations adolescents. On the other hand, among first- and second-generation adolescents from Eastern Europe and non-Western/non-European countries the differences with the host population remained appreciable. Even if the level of perceived support appeared to slightly improve, these results highlight the difficulties that these groups of adolescents have to deal with. In particular, and independent of ethnic background, is perceived teacher support, which seemed to worsen among the second-generation immigrants. This suggests that teachers tend to pay less attention to the process of integration among second-generation adolescent immigrants.

Indeed, recent studies have underlined the fact that teachers represent an adult figure with whom adolescents, in particular those with low perceived family support and belonging to lower social classes, experience meaningful relationships that have an impact on their cultural values, well-being, and self-esteem [19, 31]. According to these studies, the school environment may represent the centre where adolescents receive the support needed to develop their acculturation process. The public school should be a privileged arena for socio-cultural integration, where teachers and classmates may find an additional, bridging role between the culture of the host country and that of other ethnic communities [26].

The real challenge lies in the enhancement of teachers’ and other school staffs’ ability to properly responding to problems that adolescent immigrants may have in their acculturation problems. As the processes that lead to discriminatory behaviour are often unconscious, increasing teachers’ awareness of these problems will allow them to consider their assumptions about students more carefully and to engage in a more thorough, thoughtful, less biased evaluation of their students [30]. Indeed, professionals need the awareness, knowledge, and skills to intervene in a responsive and appropriate manner with culturally diverse clients, since cultural responsiveness requires more than simply being “sensitive” to cultural diversity [27, 32].

Schools should create programmes that support positive ethnic identity development, enhance bicultural self-efficacy (the ability to function effectively in multiple cultural contexts), and allow adolescents to be engaged [27]. This can be achieved by increasing school connection with families, or helping adolescents develop social networks through school groups or clubs. Indeed, research has shown that network-building interventions are more likely to be beneficial if immigrant youths are supported in building social connections that reflect the family’s culture of origin, not just the adopted culture [27, 30].

This study also has limitations that should be taken into account: our study has a cross-sectional design and therefore does not allow us to infer any cause-effect relationship between the investigated factors; no information was available on the length of stay in the host country of first-generation adolescent immigrants, making it impossible to determine whether the observed differences are dependent on ethnic background itself or could be attributed to a shorter acculturation process. This study is one of the first to investigate how immigrant status modifies adolescents’ perception of support, taking into account gender, age, ethnic background, and being a first or second generation immigrant. Additionally, the study is based on a robust survey, the HBSC study, which has the largest sample size available in these developmental ages. As such, it contributes to the expanding research in this field.

In support of our results, previous research has demonstrated that the child rearing practices of immigrant parents are generally dominated by the values of their culture of origin, allowing for a strong ethnic effect on the children [27]. According to these studies we have also been able to describe two different pattern of immigration, in which adolescents coming from less affluent countries perceived lower family and peer support compared to their Italian classmates and to those from Western countries, resulting in a possible culture clash, which needs to be explored in more depth.

References

Aro H, Hänninen V, Paronen O. Social support, life events and psychosomatic symptoms among 14–16-year-old adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29(9):1051–6.

Barker G. Adolescents, social support and help-seeking behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. pp. 10–1.

Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol. 1997;46(1):05–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth: acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Appl Psychol. 2006;55(3):303–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x.

Berry JW, Sabatier C. Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: their relationships with psychological wellbeing. Int J Intercult Relat. 2011;35(5):658–69.

Bynner J. Childhood risks and protective factors in social exclusion. Child Soc. 2001;15(5):285–301.

Canty-Mitchell J, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in urban adolescents. Am J Commun Psychol. 2000;28(3):391–400.

Cauce AM. Social networks and social competence: exploring the effects of early adolescent friendships. Am J Commu Psychol. 1986;14(6):607–28.

Cauce AM, Felner RD, Primavera J. Social support in high-risk adolescents: structural components and adaptive impact. Am J Commun Psychol. 1982;10(4):417–28.

Cavallo F, Lemma P, Dalmasso P, Vieno A, Lazzeri G, Galeone D. (2016) Report Nazionale dati HBSC Italia 2014: 4° Rapporto sui dati HBSC Italia 2014. Stampatre s.r.l., Torino.

Chen X, French DC. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:591–616.

Chung RH. Gender, ethnicity, and acculturation in intergenerational conflict of Asian American college students. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7(4):376.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310.

Coleman D. (2013) Immigration, population and ethnicity: the UK in International Perspective. Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, UK. http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/ Accessed 19 sep 2017.

Currie C, Inchley J, Molcho M, Lenzi M, Veselska Z, Wild F, editors. Health Behaviour in school-aged children (Hbsc) study protocol: background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2013/14 survey. St Andrews: CAHRU; 2014.

Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, Holstein B, Torsheim T, Richter M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1429–36.

Currie C, Nic Gabhainn S, Godeau E. The health behaviour in school-aged children: WHO collaborative cross-national (HBSC) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982–2008. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:131–9.

DuBois DL, Felner RD, Brand S, Adan AM, Evans EG. A prospective study of life stress, social support, and adaptation in early adolescence. Child Dev. 1992;63(3):542–57.

Gecková A, Van Dijk JP, Stewart R, Groothoff JW, Post D. Influence of social support on health among gender and socio-economic groups of adolescents. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13(1):44–50.

Goossens FX, Onrust SA, Monshouwer K, de Castro BO. Effectiveness of an empowerment program for adolescent second generation migrants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;64:128–35.

Inchley J, et al. editors. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. Copenaghen: World Health Organization; 2016.

ISTAT Migrazioni internazionali e interne della popolazione residente 2015. In: Statistiche ISTAT, Report, (ed). Roma; 2016.

Koneru VK, de Mamani AGW, Flynn PM, Betancourt H. Acculturation and mental health: current findings and recommendations for future research. Appl Prev Psychol. 2007;12(2):76–96.

MIUR Gli alunni stranieri nel sistema scolastico italiano: A.S. 2014/2015. Roma: MIUR - Ufficio di Statistica; 2015

Nordahl H, Krølner R, Páll G, Currie C, Andersen A. Measurement of ethnic background in cross-national school surveys: agreement between students’ and parents’ responses. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(3):272–7.

Oppedal B, Røysamb E, Sam DL. The effect of acculturation and social support on change in mental health among young immigrants. Int J Behav Dev. 2004;28(6):481–94.

Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: an interactional perspective. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(3):493–510.

Phinney JS, Ong A, Madden T. Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Dev. 2000;71(2):528–39.

Resnick MD, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–32.

Rogers-Sirin L, Ryce P, Sirin SR. Acculturation, acculturative stress, and cultural mismatch and their influences on immigrant children and adolescents’ well-being Global perspectives on well-being in immigrant families. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 11–30.

Sarkova M, Bacikova-Sleskova M, Madarasova Geckova A, Katreniakova Z, van den Heuvel W, van Dijk JP. Adolescents’ psychological well-being and self-esteem in the context of relationships at school. Educ Res. 2014;56(4):367–78.

Shin R, Daly B, Vera E. The relationships of peer norms, ethnic identity, and peer support to school engagement in urban youth. Prof School Couns. 2007;10(4):379–88.

Stevens GW, et al. An internationally comparative study of immigration and adolescent emotional and behavioral problems: effects of generation and gender. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(6):587–94.

Stronks K, Kulu-Glasgow I, Agyemang C. The utility of ‘country of birth’for the classification of ethnic groups in health research: the Dutch experience. Ethn Health. 2009;14(3):255–69.

Tietjen AM (1989) The ecology of children’s social support networks. In: Belle D (ed) Children’s social networks and social supports. Wiley, Toronto, CA, pp 37–69

Tietjen AM (2006) Cultural influences on peer relations: an ecological perspective. In: Chen X, French D, Schneider B (eds) Peer relationships in cultural context. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 52–74

Torsheim T, et al. Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: a latent variable approach. Child Indic Res. 2016;9(3):771–84.

Torsheim T, Wold B. School-related stress, support, and subjective health complaints among early adolescents: a multilevel approach. J Adolesc. 2001;24(6):701–13.

Torsheim T, Wold B, Samdal O. The teacher and classmate support scale factor structure, test-retest reliability and validity in samples of 13-and 15-year-old adolescents. Sch Psychol Int. 2000;21(2):195–212.

Walker LS, Greene JW. Negative life events, psychosocial resources, and psychophysiological symptoms in adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 1987;16(1):29–36.

Ystgaard M, Tambs K, Dalgard OS. Life stress, social support and psychological distress in late adolescence: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(1):12–9.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7.

Funding

Funding was provided by Italian Ministry of Health (Grant No. cap.4393/2005-CCM )

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PD conducted the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; AB, PL edited the draft and completed the manuscript, both made the greatest contribution to the paper; GL, LC and PB contributed to the paper revision and to the final manuscript editing. PD, AB, PL, FC, LC, PB and GL participated in designing the study and data collection as members of the HBSC Italian team. All authors have critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dalmasso, P., Borraccino, A., Lazzeri, G. et al. Being a Young Migrant in Italy: The Effect of Perceived Social Support in Adolescence. J Immigrant Minority Health 20, 1044–1052 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0671-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0671-8