Abstract

This study examined whether authoritarian parenting, school experiences, depression, legal involvement and social norms predicted recent alcohol use and binge drinking among a national sample of Hispanic youth. A secondary data analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health was performed (N = 3457). Unadjusted odds ratios were computed via univariate logistic regression analyses and significant variables were retained and included in the multivariable logistic regression analyses. Results indicated that in the past 30 days, 13.8 % of Hispanic youth drank alcohol and 8.0 % binge drank. Hispanic youth at highest risk for alcohol use were 16–17 years of age, experienced authoritarian parenting, lacked positive school experiences, had legal problems, and felt that most students at their school drank alcohol. Results should be considered when developing and implementing alcohol prevention efforts for Hispanic youth. Multiple approaches integrating family, school, and peers are needed to reduce use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Alcohol use is a significant health problem among youth in the US [1]. Overall, Hispanic youth alcohol use continues to be higher in comparison to their non-Hispanic counterparts [2]. The most recent Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey revealed that more Hispanic youth (73.2 %) have ever drank alcohol than white or black youth (71.7 and 63.5 %, respectively). Also, more Hispanic youth (42.3 %) have used alcohol in the past 30 days than white or black youth (40.3 and 30.5 %, respectively). Even more disconcerting is that Hispanic youth have the highest prevalence of binge drinking (24.2 %) as compared to white or black youth (24.0 and 12.4 %, respectively) [2].

Risk factors for adolescent alcohol use can be found across individual, family, community and school levels [3]. Individually, youth with low decision making skills and low communication skills increased their likelihood to use alcohol [4]. Additionally, those who begin drinking earlier in adolescence are more likely to develop alcohol dependence or alcohol abuse later in life [5]. Previous studies show that early onset of alcohol use has been linked to injuries, drinking and driving, truancy, traffic crashes, risky sexual behavior, and other drug use in later adolescent years and into adulthood [6].

Parenting styles may affect a child’s behavior, psychosocial, and emotional functioning, both positively and negatively [7, 8]. Baumrind [7] established three specific parenting styles as a result of distinct interactions between parent and child. Based on varying levels of demandingness and responsiveness, these styles include authoritative as high demandingness and high responsiveness, authoritarian as high demandingness and low responsiveness and permissive with low demandingness and high responsiveness. Concerning parenting styles and alcohol use, adolescents from authoritative homes have been found to be significantly less likely to drink heavily or have friends that drink [9], whereas adolescents from authoritarian styled homes tend to participate more frequently in risky behaviors including alcohol use and smoking [10]. Limited research has been conducted specifically on the impact parenting styles may have on Hispanic youth substance use.

School connectedness, including adult support, peer connections, commitment to education, and overall school environment, plays a significant role in youth alcohol use [11]. Conversely, poor student–teacher relationships and disengagement from school place youth at a higher risk for substance use and other risky health behaviors [12]. Students with low school efficacy, which includes negative feelings about the school, teachers, and classes, are more susceptible to alcohol use [13]. Students who report that their teachers and schools never talk about alcohol and other drugs were most likely to use these substances [14]. Youth who have poor grades in school are at a higher risk to use alcohol [15]. Fletcher and colleagues [12] reveal that schools can influence students’ drug use based on levels of inclusivity. Although there are many prevention programs available for schools, predominantly Hispanic schools receive significantly fewer substance abuse programs than students in predominately white schools [16].

Non-adherence to laws is a common characteristic of youth who report substance abuse, and a strong relationship has been found between early onset of crime activity and early onset of substance use among youth [17]. To demonstrate the relationship between crime and alcohol use, the latest Bureau of Justice Statistics Prison and Jail Inmate Survey [18] reveals that nearly one-third of prisoners reported using alcohol at the time of their offense. Youth who report legal problems and also substance abuse tend to suffer from more serious health, psychological, and social consequences including severe substance abuse, family maladjustment, and peer connection problems than their counterparts [19]. A previous research study on Hispanic male adolescents found that this population is at higher risk of being rearrested for drug charges or any charge compared to other ethnic groups [20]. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research regarding legal problems and alcohol use.

Hispanic youth tend to report high levels of depressive symptoms compared to non-Hispanic youth [21]. Unfortunately, alcohol abuse and dependence occur more frequently among individuals who are diagnosed with depression compared to those who are not diagnosed with depression [22]. A previous study conducted among youth indicated that alcohol-related problems were associated with increased rates of depression [23]. Regarding Hispanic youth, the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [2] found that Hispanic youth were more likely than their white and black counterparts to report higher rates of alcohol use and depressive symptoms. These findings highlight the need to examine this potential association among Hispanic youth.

Interpersonal risk factors for alcohol use include youth who perceive that their peers approve of alcohol use and drink frequently [24]. Additionally, youth with friends who frequently engage in alcohol use are at higher risk of use compared to youth with friends who do not use alcohol [14, 25, 26]. Youth are also more likely to drink if they associate with peers who participate in other risky behaviors [27]. Conversely, youth with peers who highly disapprove of alcohol decreases the likelihood of use [24]. An examination of the effect peer social norms may have on drinking among Hispanic youth is needed. Although Hispanic youth report higher rates of alcohol use compared to other ethnic groups [2], many drug prevention programs lack cultural sensitivity and relevance to engage Hispanic youth [28].

The present study was conducted to address gaps in the research concerning alcohol use among Hispanic youth and to assist professionals in developing effective prevention efforts. This study sought to determine factors associated with recent alcohol use and recent binge drinking (past 30 days) among Hispanic youth. More specifically, the following research questions were investigated: (1) What percent of Hispanic youth engage in recent alcohol use and recent binge drinking? (2) What impact do sex, age, authoritarian parenting, school experiences, lifetime depression, legal problems, and perceived social norm regarding youth alcohol use have on Hispanic youth involvement in recent alcohol use and binge drinking?

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

A secondary data analysis of data from the NSDUH was performed in the present study. The NSDUH is conducted by the US Federal Government to determine the prevalence of substance use among US individuals aged 12 or older. This survey collects data through face-to-face interviews with a representative sample at individuals’ residences. For a complete description of the sampling method and data collection procedures, please see the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [29].

Measures

Demographics

Participants in this study were individuals who self-identified as Hispanic youth aged 12–17 years. A total of 3457 Hispanic youth completed the NSDUH survey. Age was trichotomized into the following categories: 12–13 years old, 14–15 years old, and 16–17 years old.

Authoritarian Parenting

An authoritarian parenting score was developed based off of Baumrind’s [7] characteristics of authoritarian parenting including a high level of demandingness and low level of responsiveness. Youth were asked how often their parents performed the seven behaviors (e.g., checked their homework; helped with homework; do chores around the house; limited amount of time spent watching TV; limited amount of time spent with friends on school nights; told them they did a good job; and told them they were proud of something they had done) within the past 12 months. Youth responded to these items using a four-point scale and the NSDUH recoded these items into two response options (1 = always/sometimes; 2 = seldom/never) and encourages researchers to use recoded items. For the current study, scores were computed to determine an overall authoritarian parenting subscale score. The overall score was in turn dichotomized into two levels (authoritarian parenting, non-authoritarian parenting) based on NSDUH recoded items and the median split.

School Experiences

A school experiences score was computed from six items that asked youth how they felt about going to school (1 = you liked going to school a lot, 4 = you hated going to school); how often they felt school work was meaningful and important (1 = always, 4 = never); how important things they learned in school will be later in life (1 = very important, 4 = very unimportant); (4) how interesting they think their courses have been (1 = very interesting, 4 = very boring); how often teachers told them they were doing a good job with school work (1 = always, 2 = sometimes, 3 = seldom, 4 = never), and (6) their grades for the last semester or grading period they completed (1 = An ‘A+’, ‘A’, or ‘A-minus’ average, 2 = A ‘B+’, ‘B’, or ‘B-minus’ average, 3 = A ‘C+’, ‘C’, or ‘C-minus’ average, 4 = A ‘D’ or less than a ‘D’ average, 5 = my school does not give these grades).” For the current study, scores were computed to determine an overall score. The overall score was in turn dichotomized into two levels (no, yes) based on NSDUH recoding and the median split.

Depression

Depression was measured by one item which asked youth to report whether they had ever received treatment for depression (no, yes).

Legal Involvement

Legal involvement was measured via three items: Ever having been arrested and booked for breaking the law (no, yes); on probation at any time during the past 12 months (no, yes), and on parole or supervised release in the past 12 months (no, yes). If youth answered yes to any of these three items they were operationally defined as having been involved with the law (no, yes).

Perceived Student Use of Alcohol

Perceived student use of alcohol was measured by one item which asked youth to report how many students they know in their grade who drink alcohol (1 = none, 2 = a few of them, 3 = most of them, 4 = all of them). This variable was subsequently dichotomized into two levels (1 = none/a few of them; 2 = most/all of them) by the NSDUH and based on the median split.

Alcohol Use

Recent alcohol use was measured by one item which asked youth if they had used alcohol in the past month (no, yes). Similarly, recent binge drinking was measured by one item which asked youth whether they had binge drank (drank 5 or more alcoholic beverages on the same occasion) in the past 30 days (no, yes).

Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 21.0). Descriptive results were calculated with frequencies (means, standard deviations, percentages, etc.). Unadjusted odds ratios were computed via univariate logistic regression analyses (n = 3477) to determine whether recent alcohol use and recent binge drinking differed based on sex, age, authoritarian parenting, school experiences, lifetime depression, legal involvement, and perceived social norms regarding youth alcohol use. Variables that were significant in these analyses were retained and included in the final multivariable logistic regression analyses. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the percent of variance accounted for by the models.

Ethics Approval

The university-based Institutional Review Board determined this study as “not human subjects” and was exempt from review.

Results

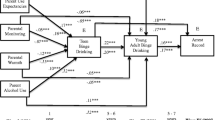

Sex was evenly distributed between female youth (n = 1732, 50.1 %) and male youth (n = 1725, 49.9 %). Results indicated that in the past 30 days 13.8 % of Hispanic youth drank alcohol and 8.0 % binge drank. Unadjusted odds ratios revealed that age, authoritarian parenting, school experiences, lifetime depression, legal involvement, and perceived social norm regarding youth alcohol use were significant predictors of both recent alcohol use and recent binge drinking (Table 1). These variables were retained and included in the final multvariable regression models that significantly predicted recent alcohol use (omnibus χ2 = 351.67, df = 7, p < .001) and accounted for 11.1 to 19.5 % of the variance in recent alcohol use. Statistically significant predictors were age, authoritarian parenting, school experiences, legal involvement, and perceived social norm regarding youth alcohol use (Table 2). Hispanic youth at highest risk for recent alcohol use were 16–17 years of age (OR = 5.345, p < .001), experienced authoritarian parenting (OR = 1.456, p < .001), lacked positive school experiences (OR = 1.281, p < .05), had legal problems (OR = 2.379, p < .001), and felt that most students at their school drank alcohol (OR = 2.642, p < .001). Regarding recent binge drinking, the final multivariable regression model significantly predicted recent binge drinking (omnibus χ2 = 237.357, df = 7, p < .001) and accounted for 7.6 to 17.2 % of the variance in recent binge drinking. Statistically significant predictors were age, authoritarian parenting, school experiences, legal involvement, and perceived social norms regarding youth alcohol use (Table 2). Hispanic youth at highest risk for recent binge drinking were 16–17 years of age (OR = 6.183, p < .001), experienced authoritarian parenting (OR = 1.429, p < .05), lacked positive school experiences (OR = 1.494, p < .01), had legal problems (OR = 2.246, p < .001), had ever had depression and felt that most students at their school drank alcohol (OR = 2.731, p < .001).

Discussion

The present study examined recent alcohol use and binge drinking among a national sample of Hispanic youth. Specifically, the impact of authoritarian parenting, school experiences, depression, legal involvement, and perceived social norms on youth alcohol use was investigated. Regarding parenting style, Hispanic youth were at reduced risk if their parents did not use an authoritarian parenting style. Specific to the Hispanic culture, Hispanic parents value strictness in their parenting practice to protect their children from harmful social influences [30]. Previous research has indicated that as parental warmth and control increases in Hispanic homes, youth alcohol use decreases [31]. On the other hand, Shi, Steen, and Weiss [32] revealed that low parental support increased the risk for substance use among Hispanic youth. Youth are more likely to recently use alcohol if their parents seldom or never talked to them about alcohol use or set strict rules about alcohol use [14]. Such findings should be considered when tailoring substance use prevention programs for Hispanic youth. Including parents in initiatives may help to decrease substance use by encouraging parents to play a significant role in drug prevention efforts. Educating parents and their youth on authoritative parenting practices and increasing parent–child communication about substance use are important components to include in prevention programs. It is important to consider that culturally grounded prevention programs for Hispanic youth has strong influence on their overall interest and retention [28].

A lack of positive school experiences was a significant predictor of recent alcohol use and binge drinking in Hispanic youth. Voelkl and Frone [33] found that adolescents were more likely to use substances if perceived risk of being caught at school was low, suggesting that low monitoring by school personnel may be a risk factor for adolescent substance use. Additionally, inadequate relationships and activities in school were found to be a significant indicator of alcohol use [34]. Several studies indicate that school wide bonding or attachment and having peers with positive attitudes towards school decreases the likelihood of personal substance use [35]. Furthermore, overall school culture and ability to engage students influenced substance use rates [36]. School environment plays a vital role in youth alcohol use, and should be taken into consideration when developing prevention programs for students. School personnel should be educated on increasing positive school experiences, offering effective prevention programs including development of resistance skills, and building personal efficacy and social skills among youth [16].

Regarding legal problems, having ever been arrested and booked for breaking the law, on probation and parole or supervised released in the past year significantly increased the odds for alcohol use. Early intervention may be needed to alleviating both legal problems and alcohol use. Previous research suggests that delinquent involvement in late childhood projected involvement in crime during the adolescent and early adulthood years [37]. Unfortunately, the earlier delinquent behaviors begin, the more challenging it becomes to resume a positive developmental course. One recent study found Hispanic youth were significantly more likely to be rearrested in the year after being released from jail compared to non-Hispanic youth [20]. In addition, Tarter and colleagues [19] revealed that even though male youth are more likely to report higher substance use and criminal activity, female youth with legal problems tend to report more serious health and psychosocial disturbances than male youth. Regardless of sex, youth with simultaneous legal problems and substance abuse report more serious health and psychosocial consequences than their counterparts who did not report legal involvement. These findings can be used when creating and adapting prevention programs, especially for youth with legal problems.

The present study found that Hispanic youth who reported that most or all of their same-grade peers drink alcohol were at elevated risk of reporting alcohol use. In fact, these youth were at nearly three times greater risk for reporting alcohol use than their counterparts. This particular finding is unique as it highlights the potential impact perceived drinking norms may have on alcohol use among Hispanic youth. Previous research indicates that having friends who use alcohol and other drugs is a strong predictor for alcohol use among youth [25, 26]. Therefore, programs may target social norms and peer substance use as a prevention strategy to reduce drinking [38].

Interestingly, having ever received treatment for depression did not significantly predict recent alcohol use and binge drinking. This finding is surprising as it is contrary to previous research. Studies of youth found alcohol use is associated with depression with alcohol abusers at highest risk [39]. However, to date, the majority of studies examining alcohol use and depression among youth focus predominantly on Caucasian youth and lack diversity in population samples [40]. Future research should examine potential relationships between depression and substance use among minority populations.

Limitations

Limitations should be noted. The data are self-reported and thus depend on respondents’ honesty and accurate memory recall. Second, the self-report nature of the survey may have resulted in some students responding in a socially desirable manner. Third, the study is cross-sectional as opposed to longitudinal and therefore causal relationships cannot be determined. Finally, study participants were delimited to Hispanic youth who were 12 to 17 years of age. Thus, caution should be used when attempting to generalize these findings to individuals of other ages and ethnicities.

New Contribution to the Literature

The present study was conducted to address gaps in the research concerning alcohol use among Hispanic youth and found high rates of alcohol use in a national sample of Hispanic youth, especially among the 16–17 age group. Targeting prevention programs to Hispanic youth at early ages may reduce underage drinking. Based on study findings, incorporating parents into educational programs and building positive parenting skills may be an effective strategy to reduce alcohol use among Hispanic youth. At the school level, employing techniques to positively connect students to school and peers may decrease the likelihood of use. Multiple approaches integrating family, school, and peers are needed to reduce recent use and binge drinking.

References

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking, 2013. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/UnderageDrinking/Underage_Fact.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance system: Selected 2011 national health risk behaviors and health outcomes by race/ethnicity. Centers Dis Control Prev. 2011.

Brookmeyer K, Fanti K, Henrich C. Schools, parents, and youth violence: a multilevel, ecological analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(4):504–14.

Stephens P, Sloboda Z, Stephens R, et al. Universal school-based substance abuse prevention programs: modeling targeted mediators and outcomes for adolescent cigarette, alcohol and marijuana use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102(1–3):19–29.

Corte C, Szalacha L. Self-cognitions, risk factors for alcohol problems, and drinking in preadolescent urban youths. J Child Adolesc Subs Abuse. 2010;19(5):406–23.

Bradshaw C, Waasdorp T, Goldweber A, Johnson S. Bullies, gangs, drugs, and school: understanding the overlap and the role of ethnicity and urbanicity. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(2):220–34.

Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4(1, pt 2):1–103.

Brand S, Hatzinger M, Beck J, et al. Perceived parenting styles, personality traits and sleep patterns in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2009;32(5):1189–207.

Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP. Parenting style, religiosity, peers, and adolescent heavy drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(4):539–43.

Sartaj B, Aslam N. Role of authoritative and authoritarian parenting in home, health and emotional adjustment. J Behav Sci. 2010;20(1):47–66.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School connectedness: Strategies for increasing protective factors among youth, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/pdf/connectedness.pdf.

Fletcher A, Bonell C, Hargreaves J. School effects on young people’s drug use: a systematic review of intervention and observation studies. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:209–20.

Browning S. Neighborhood, school, and family effects on the frequency of alcohol use among Toronto youth. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(1):31–43.

King K, Vidourek R. Psychosocial factors associated with recent alcohol use among Hispanic youth. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32(3):470–85.

Vaughan E, Kratz L, d’Argent J. Academics and substance use among Latino adolescents: results from a national study. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2011;10(2):147–61.

Kumar R, O’Malley P, Johnston L, Laetz V. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use prevention programs in U.S. schools: a descriptive summary. Prev Sci. 2013;14:581–92.

Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Battjes RJ. Correlates of early substance use and crime among adolescents entering outpatient substance abuse treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):39–59.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. Alcohol and crime: Data from 2002 to 2008. Office of Justice Programs, 2010. http://www.bjs.gov/content/acf/29_prisoners_and_alcoholuse.cfm.

Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, et al. Multivariate comparison of male and female adolescent substance abusers with accompanying legal problems. J Crim Justice. 2011;39:207–11.

Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, et al. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1725–36.

Polo AJ, Lopez SR. Culture, context, and the internalizing distress of Mexican American youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(2):273–85.

Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2005;118(4):330–41.

Wu P, Hoven CW, Okezie N, et al. Alcohol abuse and depression in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2007;17(2):51–69.

D’Amico E, McCarthy D. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescent’s substance use: the impact of perceived peer use. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:481–7.

Belendiuk K, Molina BSG, Donovan JE. Concordance of adolescent reports of friend alcohol use, smoking, and deviant behavior as predicted by quality of relationship and demographic variables. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(2):253–7.

Institute Search. Tapping the power of community: building assets to strengthen substance abuse prevention. Insights Evid. 2004;2:1–14.

Clark T, Nguyen A, Belgrave F. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and marijuana use among African-American rural and urban adolescents. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2011;20(3):205–20.

Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, et al. Culturally grounded substance use prevention: an evaluation of the keepin’ it R.E.A.L. curriculum. Prev Sci. 2003;4(4):233–48.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013.

Wagner K, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, et al. The role of acculturation, parenting, and family in Hispanic/Latino adolescent substance use: findings from a qualitative analysis. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2008;7(3):304–27.

Mogro-Wilson C. The influence of parental warmth and control on Latino adolescent alcohol use. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2008;30(1):89–105.

Shi Q, Steen S, Weiss BA. The impact of parental support and perception of school on hispanic youth’s substance use. Family J. 2013;21(4):425–34.

Voelkl KE, Frone MR. Predictors of substance use at school among high school students. J Educ Psychol. 2000;92(3):583.

Case S. Indicators of adolescent alcohol use: a composite risk factor approach. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(1):89–111.

Henry KL, Slater MD. The contextual effect of school attachment on young adolescents’ alcohol use. J School Health. 2007;77(2):67–74.

Bisset S, Markham WA, Aveyard P. School culture as an influencing factor on youth substance use. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(6):485–90.

Mason WA, Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, et al. Alcohol use disorders and depression: protective factors in the development of unique versus comorbid outcomes. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2010;19:309–23.

Nation M, Hefflinger CA. Risk factors for serious alcohol and drug use: the role of psychosocial variables in predicting the frequency of substance use among adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:415–33.

McCarty C, Wymbs B, King K, et al. Developmental consistency in associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol use in early adolescence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:444–53.

Galaif E, Sussman S, Newcomb M, et al. Suicidality, depression, and alcohol use among adolescents: a review of empirical findings. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;19:27–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, K.A., Vidourek, R.A., Merianos, A.L. et al. Psychosocial Factors Associated with Alcohol Use Among Hispanic Youth. J Immigrant Minority Health 19, 1035–1041 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0485-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0485-0