Abstract

Recent theories and studies have provided evidence that parental autonomy granting is linked to adolescents’ life satisfaction, but very few studies have investigated this relationship in Chinese cultural contexts. Additionally, the potential mechanisms underlying this relationship are not comprehensively understood. This study examined whether autonomy granting parenting practice promoted adolescents’ life satisfaction and whether this link was mediated by emotional self-efficacy and future orientation among 795 Chinese junior high school, senior high school, and college students (59.87% girls). Based on a longitudinal design, autonomy granting parenting practice and emotional self-efficacy were assessed at Time 1, and future orientation and life satisfaction were assessed at Time 2. Structural equation modeling revealed that autonomy granting parenting practice was directly related to adolescents’ life satisfaction and indirectly through both emotional self-efficacy and future orientation. Furthermore, the effects of these mediators differed across the various stages of adolescence. Specially, for college students, self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions independently mediated the relationship between parental autonomy granting and life satisfaction. For senior high school and college students, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions and future orientation sequentially mediated this relationship. In addition, future orientation also mediated the relationship between autonomy granting and life satisfaction; however, the mediating effect of future orientation differed in direction for the junior and senior high school samples. These findings highlight the importance of providing adolescents with autonomy and targeting specific mediating factors to enhance life satisfaction of individuals at different stages of adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, interest in studying life satisfaction has grown tremendously due to the increasing recognition of life satisfaction as an important factor associated with individuals’ adjustment in multiple domains (e.g.,Chughtai, 2021; Heffner & Antaramian, 2016; Siahpush et al., 2008). Because of the beneficial role of life satisfaction in successful adjustment, it is critical to investigate factors influencing life satisfaction. Understanding the precursors of life satisfaction would promote applied efforts for optimal development. The present study aimed to examine the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on life satisfaction. Furthermore, it investigated the underlying mechanisms of these effects and explored the potential mediating roles of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation. In the present study, we focused on the adolescent period. During this period, the development of abstract thinking enables adolescents to more accurately appraise current statuses and their desires and needs; therefore, adolescence can be a vital time for constructing life satisfaction (Cikrikci & Odaci, 2016). In addition, adolescence is a critical stage for negotiating parent-adolescent relationships (Fuligni, 1998), developing self-efficacy (Bandura et al., 2003), and thinking and planning for the future (Nurmi, 1991). In this study, we aimed to examine the relationships between autonomy granting parenting practice and adolescents’ life satisfaction and the mediating effects of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation.

1.1 Autonomy Granting Parenting Practice and Life Satisfaction

As a key component of subjective well-being, life satisfaction is defined as a cognitive judgment of one’s perceived quality of life as a whole or in specific domains, such as family relations, friends, and school (Huebner et al., 2013). In general, a higher level of life satisfaction is important for individuals of different ages to adapt in multiple life domains (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Previous research has shown that life satisfaction is positively associated with children’s successful school outcomes (Forrest et al., 2013) and negatively associated with children’s problem behaviors (e.g., depression; Chai et al., 2018). And for adults, life satisfaction can promote their health conditions (Siahpush et al., 2008) and job performance (e.g., in-role performance, innovative work behavior, and organizational citizenship behavior; Chughtai, 2021). Additionally, life satisfaction also affects adolescents’ adjustment. For instance, adolescents with positive evaluations of life satisfaction are likely to attain high levels of academic achievement (Heffner & Antaramian, 2016), whereas those with negative evaluations of life satisfaction are at higher risk of internalizing and externalizing problems (Suldo & Huebner, 2004; Sun & Shek, 2010). Because of the crucial role of life satisfaction, it is particularly important to identify manipulable contextual factors to promote life satisfaction.

Among these contextual factors, autonomy granting parenting practice is vital for individuals’ life satisfaction. Autonomy granting parenting practice is primarily characterized as parents’ acknowledgment of their children’s opinions, provision of opportunities for their children to make choices independently, and usage of more democratic methods to discipline their children instead of controlling them (Steinberg et al., 1992). According to self-determination theory, autonomy is one of the three basic psychological needs of individuals (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2002). Receiving adequate autonomy from one’s parents facilitates the satisfaction of the individual’s psychological need for autonomy, which promotes personal growth, vitality, and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2002). The fulfilment of the need for autonomy may be particularly critical in the period of adolescence, when individuals increasingly desire more autonomy and tend to renegotiate the boundaries of jurisdiction with parents (Coffey et al., 2020; Fuligni, 1998). Empirical evidence has also supported self-determination theory and consistently suggested that autonomy granting parenting practice is beneficial for life satisfaction among American (Reed et al., 2016; Suldo & Huebner, 2004), Danish, Korean (Ferguson et al., 2011), and European adolescents (Filus et al., 2019).

However, previous research on the relationships between autonomy granting parenting practice and adolescents’ life satisfaction has mainly focused on Western adolescents. Notably, Chinese cultural values may provide a unique milieu that is different from that of Western cultural contexts for examining this relationship. Chinese cultural values are the result of the mutual collision, exchanging and fusion between traditional Confucian values and individualistic values. Traditional Chinese culture is characterized as collectivism, with emphasis on values such as conformity to social norms, submission to authority, and discouragement of autonomy (Peterson et al., 2005). With social change, Chinese cultural values are shifting towards individualism which emphasizes autonomy and the self (Xu & Hamamura, 2014; Zeng & Greenfield, 2015). Since the degree of compatibility between parental autonomy granting and the broad cultural context influences the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice (Bi et al., 2020), it is valuable to investigate the effect of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction in contemporary Chinese cultural contexts.

1.2 The Mediating Effect of Emotional Self-efficacy

Since the relationship between parenting practices and life satisfaction has been established, researchers have begun to investigate the underlying mechanisms of this relationship. Several recent studies have identified proxy mechanisms through which parenting practices could influence adolescents’ life satisfaction, including adolescents’ self-esteem (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019) and psychological connectedness (Filus et al., 2019). However, the underlying mechanisms are still far from being fully understood. Identifying these mechanisms is critical for both understanding the connection between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction and developing effective intervention strategies for enhancing adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Social cognitive theory proposes self-efficacy as an important mediational factor deserving scholarly attention (Bandura, 2001; Lent et al., 2005). Self-efficacy is defined as the beliefs that individuals hold about their capacity to exert control over the events that affect their lives, and it plays a crucial role in self-regulation processes (Bandura, 2001). Researchers have extended analysis of self-efficacy belief systems to self-beliefs linked to the domain of emotion (Caprara et al., 2008). Emotional self-efficacy refers to an individual’s perceived ability to regulate his/her emotions and is divided into two constructs: self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions (POS) and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions (NEG). POS is defined as the perceived “capability to experience and to allow oneself to express positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm and pride in response to success or pleasant events” (Caprara et al., 2008, p. 229). NEG refers to the perceived “capability to ameliorate negative emotional states once they are aroused in response to adversity or frustrating events and to avoid being overcome by emotions such as anger, irritation, despondency, and discouragement” (Caprara et al., 2008, p. 229).

According to social cognitive theory, environmental support and resources (e.g., positive parenting practices and support from friends) enhance one’s self-efficacy, which in turn is expected to contribute to life satisfaction (Lent et al., 2005). Empirical evidence has indicated that adolescents’ self-efficacy is positively associated with parental support (Kerpelman et al., 2008) and parental involvement (Yap & Baharudin, 2016) but negatively associated with maternal rejection (Niditch & Varela, 2012). Researchers have also investigated the role of parental autonomy granting on adolescents’ emotional self-efficacy (Roth et al., 2009). For instance, Roth et al. (2009) found that parental autonomy support promoted Israeli middle adolescents’ development of feelings of choice, which facilitated their integrative regulation of anger and fear. When adolescents perceive that their perspectives are considered and their emotions are legitimized, they feel more secure in expressing themselves and regulating their emotions. In contrast, when adolescents perceive that they are overly controlled, their volitional functioning is impeded (Barber & Xia, 2013; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010), which results in difficulty of regulating emotions (Cui et al., 2014). These experiences of regulating emotions influence adolescents’ emotional self-efficacy (Bandura, 1993).

In addition, adolescents’ beliefs about their capability to manage emotions are crucial to achieving life satisfaction. Previous research on the relationship between emotional self-efficacy and life satisfaction has generally shown that middle or late adolescents’ emotional self-efficacy is positively associated with life satisfaction. This result has been confirmed in Western cultural contexts, such as Italy (Caprara et al., 2006), Germany (Gunzenhauser et al., 2013), and the US (Lightsey et al., 2011, 2013), and in a few collectivistic cultural contexts, such as Malaysia (Yap & Baharudin, 2016). Self-efficacy in regulating emotions may serve as an important psychological resource to help adolescents experience life satisfaction (Luthans et al., 2007).

Based on social cognitive theory and empirical evidence, we hypothesized that emotional self-efficacy would be a mediator between parental autonomy support and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Parents’ support of autonomy may promote adolescents’ development of emotion management skills, leading to a high level of emotional self-efficacy, thereby leading to increased life satisfaction. In addition, we separately examined the mediating effects of self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions. Previous research has shown that the frequency of positive emotion, but not the frequency of negative emotion, directly predicts life satisfaction (Coffey & Warren, 2020; Coffey et al., 2015). Self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions may be more related to promoting adjustment outcomes, whereas self-efficacy in managing negative emotions may be more related to eliminating maladjustment outcomes (Bandura et al., 2003; Caprara et al., 2008). Since achieving life satisfaction is a positive developmental outcome, it is more likely that adolescents’ self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions directly elevates the level of life satisfaction. However, the promotion of self-efficacy in managing negative emotions on satisfaction with life may be achieved through other factors.

1.3 The Mediating Effect of Future Orientation

A potential additional factor mediating the link between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction is future orientation. Future orientation, defined as the way in which adolescents anticipate and construct their futures, is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon that can be described in terms of motivation, planning and evaluation (Nurmi, 1991). In the present study, we focused on future-oriented planning which refers to how people plan to achieve their aims, interests and goals, including setting subgoals, constructing plans, and executing their plans and strategies (Nurmi, 1991).

The development of adolescents’ future orientation is a process of construction that occurs in a broad interpersonal context (Collins & Steinberg, 2006). As the main source of support and advice for adolescents, parents are fundamentally influential in youths’ various aspects of development (Seginer, 2009). Empirical evidence indicates that adolescents’ future orientation is fostered by autonomy granting parenting practice (Nyhus & Webley, 2013; Seginer et al., 2004). The development of future orientation requires the opportunity to explore and the freedom to make choices. Parental autonomy granting creates a democratic atmosphere and provides sufficient psychological resources, which may facilitate middle adolescents to orient themselves to the future (Seginer et al., 2004). In contrast, parental psychological control impairs early and middle adolescents’ mental health, which may hinder the development of future orientation (Diaconu-Gherasim et al., 2017; Nyhus & Webley, 2013).

In turn, future orientation can increase adolescents’ level of life satisfaction (e.g., Azizli et al., 2015; Su et al., 2017; Zhang, & Howell, 2011). For instance, researchers conducted a longitudinal study and found that future expectations at Time 1 positively predicted Chinese early and middle adolescents’ life satisfaction at Time 2 (Su et al., 2017). Future-oriented adolescents are less likely to be tempted by immediate benefits or constantly ruminate about past negative experiences (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Instead, they employ long-term strategies, engage themselves in the pursuit of their goals, and achieve more gratification from performing goal-oriented tasks, which could result in a high level of life satisfaction (Boniwell et al., 2010; Zhang & Howell, 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). Based on previous findings, we expected that future orientation would play a mediating role in the relationship between parental autonomy granting and adolescents’ life satisfaction.

1.4 Emotional Self-Efficacy and Future Orientation

Although both emotional self-efficacy and future orientation have been associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction following parental autonomy granting, the nature of the relationship between these two variables has not been adequately studied. The majority of previous research has used a cross-sectional design and found a positive link between self-efficacy and future orientation (Azizli et al., 2015; Kerpelman et al., 2008; Zambianchi & Bitti, 2014). However, little is known about the predictive relationship between these variables. Evidence supporting their predictive relationship would be important for understanding the underlying mechanisms of the effects of parental autonomy granting on adolescents’ life satisfaction and developing targeted strategies to promote adolescents’ life satisfaction. Therefore, the present study aimed to use a longitudinal design to investigate the predictive relationship between emotional self-efficacy and future orientation.

Based on social cognitive theory, the goals that people set for themselves and the progress they make in achieving their goals are partly determined by their self-efficacy (Lent et al., 2005). Adolescents high in self-efficacy are more likely to set high and concrete goals, form logical plans, and commit to these goals (Bandura et al., 1996). Since individuals’ concerns about the future require a fair amount of positive self-evaluation of their ability to regulate emotions, emotional self-efficacy may also have implications for adolescents’ future orientation. As a kind of psychological capital, perceived self-efficacy in regulating emotions may encourage adolescents to adopt long-term strategies and future orientation (Kerpelman et al., 2008; Luthans et al., 2007; Zambianchi & Bitti, 2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that emotional self-efficacy would promote the development of adolescents’ future orientation. Considering the associations between emotional self-efficacy and life satisfaction mentioned above, we expected that self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions would directly promote adolescents’ life satisfaction, whereas self-efficacy in managing negative emotions would promote adolescents’ life satisfaction through future orientation. Because self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions contains positive experiences which may be directly and closely associated with life satisfaction (Coffey & Warren, 2020; Coffey et al., 2015). As for self-efficacy in managing negative emotions, it is linked to reevaluating negative events and regulating negative emotions. It is less likely to directly promote life satisfaction but may be indirectly associated with life satisfaction through future orientation, such as envisioning the future, planning for the future, and taking actions to achieve future goals (Azizli et al., 2015; Coffey et al., 2015). Considering the relationships between these variables, we hypothesized that self-efficacy in managing negative emotions and future orientation would sequentially mediate the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction.

1.5 Age Differences

The present study also aimed to examine whether the relationships between parental autonomy granting, life satisfaction, emotional self-efficacy and future orientation differed among various age groups. There are reasons to expect age differences, particularly in the relationships between parental autonomy granting and emotional self-efficacy and future orientation. The interaction between parents and adolescents differs across the stages of adolescence (Morris et al., 2007). For instance, parents tend to adopt different practices and strategies to facilitate emotional regulation based on the ages of their children (Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007), which may result in different associations between parental autonomy granting and emotional self-efficacy. Concerning future orientation, previous research has found that adolescents’ plans for and commit to the future are closely related to age-graded developmental tasks and contexts (Steinberg et al., 2009). Parents may also change their parenting practices or styles targeting adolescents in different developmental periods (Zhang et al., 2017). Thus, the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on future orientation may differ across the various stages of adolescence. Since little research has directly investigated age differences in the relationships among parental autonomy granting, life satisfaction, emotional self-efficacy, and future orientation, separately exploring these relationships for adolescents in different developmental stages would enrich the literature and deepen our understanding of this research domain.

1.6 The Present Study

Considering self-determination theory and the Chinese cultural context, the first aim of this study was to examine the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction. Furthermore, we focused on the underlying mechanism of this relationship. Given the theoretical expectations (Lent et al., 2005) and the empirical evidence on the possible association between emotional self-efficacy and future orientation and their respective relationships with both autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction (e.g., Azizli et al., 2015; Caprara et al., 2006; Roth et al., 2009; Seginer et al., 2004), the second aim of the present study was to investigate both emotional self-efficacy and future orientation as mediators between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction in the same model. On the one hand, this study aimed at investigating whether emotional self-efficacy and future orientation independently mediated the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction; on the other hand, because of the association between emotional self-efficacy and future orientation, it was crucial to investigate their sequential mediating effect on this relationship. The present study also examined whether the relationships between these variables varied across the three age groups. This procedure enabled a more complete understanding of the psychological mechanisms involved in psychological well-being resulting from autonomy granting parenting practice.

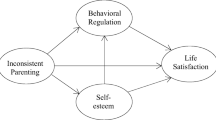

Based on previous research, we proposed four specific hypotheses: (1) parental autonomy granting would positively predict life satisfaction; (2) self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and future orientation would separately mediate the link between parental autonomy granting and life satisfaction; (3) self-efficacy in regulating negative emotions and future orientation would sequentially mediate the relationships between parental autonomy support and life satisfaction; and (4) the mediating effects of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation would differ across the three age groups. The detailed hypothesized model is presented in Fig. 1.

The assumed mediation model about the mediating effects of Mediation analysis of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation on the relationships of autonomy granting parenting practice with life satisfaction. ESE(POS) emotional self-efficacy (self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions), ESE(NEG) emotional self-efficacy (self-efficacy in managing negative emotions)

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

As a longitudinal study, the data for the current study were collected at two assessments 1 year apart (Time 1 and Time 2). We used the cluster sampling method to recruit participants from 4 secondary schools and 2 colleges in the urban areas of Jinan, the capital city of Shandong Province in eastern China. At Time 1 (T1), the sample consisted of 220 junior high school students (47.27% girls; Grade 7: Mage = 12.25 ± 0.39 years), 228 senior high school students (48.25% girls; Grade 10: Mage = 15.39 ± 0.49 years), and 550 college students (65.09% girls; freshmen: Mage = 18.38 ± 0.74 years, sophomore: Mage = 19.49 ± 0.67 years). At Time 2 (T2), 203 students withdrew from the study, and their data were excluded from the final data set, which resulted in a final sample of 203 junior high school students, 150 senior high school students, and 442 college students. They were categorized as early (age range 10–13 years), middle (age range 14–17 years), and late (age range 18–21 years) adolescents (Steinberg, 2014). The response rate for this wave was 79.66%. Attrition was modest and not selective. Furthermore, except for late adolescents’ self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions, there were no statistically significant differences between the retained and missing individuals for any of the study variables at Time 1. The results of the missing data analysis are presented in the supplemental material (see Appendix S1). The attrition rates across the three developmental stages were different. Compared with the junior high school sample, the attrition rates of senior high school and college samples were relatively higher. Sample characteristics for each age group are presented in Table 1.

2.2 Procedures

Before the data collection, all participants gave written informed consent, indicating their understanding of the study processes and their agreement to participate. The secondary school students’ parents were notified about the research and were allowed to withdraw their children from participation at any time. At each time point, the participants were administrated self-reported surveys in classrooms during school. At T1, the participants rated their perception of autonomy granting parenting practice and emotional self-efficacy. At T2, they rated future orientation and life satisfaction. It took approximately 20 min to complete all the questionnaires in each study session. No compensation was provided for the participants. Ethical approval was sought from the local institutional review board.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Autonomy Granting Parenting Practice (T1)

Autonomy granting parenting practice was assessed by the Chinese version of Parenting Style Inventory-II (Darling & Toyokawa, 1997). The autonomy granting subscale (5 items; e.g., “My mother/father believes I have a right to my own point of view”) assessed the degree to which parents use non-coercive and democratic discipline that allows for adolescents’ expression of their individuality. Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Items of this subscale were averaged to compute a subscale score. The correlation between maternal and paternal autonomy granting practice is positive and high in magnitude (r = 0.84, p < 0.001). Thus, we choose to average the scores of maternal and paternal autonomy granting practice to simplify our analysis. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) indicated that the measurement of autonomy granting parenting practice had acceptable construct validity (RMSEA = 0.051, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98).

2.3.2 Emotional Self-Efficacy (T1)

Emotional self-efficacy was assessed by the Scale of Regulatory Emotional Self-efficacy (SRESE; Caprara et al., 2008). The Chinese version of SRESE was developed by Chinese researchers and eventually a 17-item version was produced (Wang et al., 2013). The measure reflected perceived self-efficacy in managing negative emotions (NEG) and perceived self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions (POS). NEG was represented by three negative emotions: anger-irritation (4 items; e.g., “Get over irritation quickly from wrongs you have experienced”), despondency-distress (4 items; e.g., “Keep from getting discouraged by strong criticism”), and guilt-shame (3 items; e.g., “When I feel guilty, I can keep myself unaffected”). POS was represented by two positive emotions: happy (3 items; e.g., “Express enjoyment freely at parties”) and pride (3 items; e.g., “Feel gratified over achieving what you set out to do”). Participants reported their own beliefs about capabilities to regulating emotions on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with higher scores reflecting stronger endorsement of the item. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.82 and 0.88 for POS and NEG, respectively. As indicated by CFA, the present data fitted the structure well (RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94).

2.3.3 Future Orientation (T2)

Future orientation was assessed by the Chinese version of Questionnaire for Teenagers’ Future Orientation which was partly derived from the future temporal perspective subscale of Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (Liu et al., 2011; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Participants completed a measure that assessed their planning for the future (12 items; e.g., “I believe that a person’s day should be planned ahead each morning”) and taking action to achieve future goals (5 items; e.g., “I am able to resist temptations when I know that there is work to be done”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.85 and 0.70 for planning and execution in the current study, respectively. In CFA, the items fitted well to the two-factor model (RMSEA = 0.057, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94).

2.3.4 Life Satisfaction (T2)

Life satisfaction was assessed by Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS; Huebner, 1994). The Chinese version of this scale was developed and eventually a 36-item version was produced (Zhang et al., 2004). Participants assessed their satisfaction with family, friends, study, freedom, school, and living environment on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 7 (completely true). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.94 in the current study. CFA indicated that the measurement of life satisfaction had acceptable construct validity (RMSEA = 0.056, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90).

2.4 Analysis Plan

The relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and adolescents’ life satisfaction and the mediating roles of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation were analyzed by using structural equation modeling. Considering that latent structures can be used to extract information from different dimensions and synthesize more information, emotional self-efficacy, future orientation, and life satisfaction were modeled as latent variables (see Fig. 2). For emotional self-efficacy, the scores of items assessing each emotion were averaged to compute the dimensional scores, which in turn were loaded onto the two factors of emotional self-efficacy. The dimensions of happy and pride were loaded onto self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions, and the dimensions of anger-irritation, despondency-distress, and guilt-shame were loaded onto self-efficacy in managing negative emotions. Similarly, the latent constructs of future orientation and life satisfaction were also based on the subscales or measures. The total effect model analyzed the relation between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction, and emotional self-efficacy and future orientation were added as mediators in the mediation model (see Fig. 2). The total effect model and mediation model were separately analyzed with the samples of early, middle, and late adolescents. Participant gender was included as a covariant variable in all of the above models.

Models were estimated using Mplus 7.4 and the maximum likelihood estimator (ML) was used as the estimation method (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Models are deemed to have an adequate fit when the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) are higher than 0.90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is lower than 0.08 (Little, 2013).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Correlations among autonomy granting parenting practice and the latent variables (i.e., life satisfaction, emotional self-efficacy and future orientation) are presented in Table 2. Autonomy granting parenting practice was positively correlated with self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions, future orientation and life satisfaction (r = 0.21, 0.17, 0.14, and 0.23, respectively, ps < 0.01). Self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions were positively associated with future orientation (r = 0.18 and 0.39, respectively, ps < 0.01) and they were also positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.31 and 0.38, respectively, ps < 0.001). Future orientation was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.70, p < 0.001).

3.2 Mediation Analyses

The total effect model showed an acceptable fit to the data in the early and late adolescent samples (early adolescents: RMSEA = 0.077, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96; late adolescents: RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94), and the fit indexes were nearly acceptable in the middle adolescent sample (RMSEA = 0.084, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.91). For the early and late adolescents, the total effect of autonomy granting parenting practice on life satisfaction was significant (early adolescents: β = 0.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.24, 0.50]; late adolescents: β = 0.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.23, 0.44]); however, it was insignificant for middle adolescents (β = 0.09, p = 0.38, 95% CI: [−0.10, 0.28]).

We further analyzed the data to examine the indirect effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction through the mediation of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation by using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples (see Table 3). The mediation model showed an acceptable fit to the data (early adolescents: RMSEA = 0.073, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92; middle adolescents: RMSEA = 0.065, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92; late adolescents: RMSEA = 0.072, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.90). Specifically, for the early and middle adolescents, future orientation mediated the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction (early adolescents: 95% CI [0.08, 0.36]; middle adolescents: 95% CI [−0.37, −0.05]). For late adolescents, self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions significantly mediated this relationship (95% CI [0.01, 0.10]). However, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions did not independently mediate this relationship in all stages of adolescence. In addition, the middle and late adolescents’ self-efficacy in managing negative emotions and future orientation sequentially mediated the impact of autonomy granting parenting practice on life satisfaction (middle adolescents: 95% CI [0.01, 0.16]; late adolescents: 95% CI [0.03, 0.09]). But self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and future orientation did not sequentially mediate this relationship.

As shown in Fig. 2, autonomy granting parenting practice was positively associated with early adolescents’ future orientation (β = 0.29, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.12, 0.46]) but negatively associated with middle adolescents’ future orientation (β = -0.26, p < 0.01, 95% CI [-0.45, -0.07]). In turn, future orientation was positively associated with early and middle adolescents’ life satisfaction (early adolescents: β = 0.71, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.51, 0.91]; middle adolescents: β = 0.71, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.48, 0.91]). For the late adolescents, autonomy granting parenting practice positively predicted self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions (β = 0.28, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.40]), which in turn positively predicted life satisfaction (β = 0.15, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.29]). In addition, autonomy granting parenting practice positively predicted the middle and late adolescents’ self-efficacy in managing negative emotions (middle adolescents: β = 0.29, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.07, 0.48]; late adolescents: β = 0.24, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.34]), and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions positively predicted future orientation (middle adolescents: β = 0.31, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.08, 0.50]; late adolescents: β = 0.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.25, 0.50]). In turn, future orientation was positively associated with middle and late adolescents’ life satisfaction (middle adolescents: β = 0.71, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.48, 0.91]; late adolescents: β = 0.55, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.38, 0.69]).

Mediation analysis of autonomy granting parenting practice on life satisfaction via emotional self-efficacy and future orientation. ESE(POS) emotional self-efficacy (self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions), ESE(NEG) emotional self-efficacy (self-efficacy in managing negative emotions). Standardized coefficients for early adolescents are ahead of slashes, for middle adolescents are between the slashes, and for late adolescents are behind slashes. The path coefficients in bold are significant at least at the .05 level. Early adolescents: RMSEA = .073, CFI = .94, TLI = .92; middle adolescents: RMSEA = .065, CFI = .94, TLI = .92; late adolescents: RMSEA = .072, CFI = .93, TLI = .90

3.3 Age Differences

Multi-group analysis was performed to identify whether the path coefficients of the mediation model differed significantly between adolescents in the three age groups. The results showed that the association between autonomy granting parenting practice and self-efficacy in expressing positive emotion was stronger for late adolescents than for early adolescents (Δχ2 (1) = 5.44, p < 0.05). The relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and self-efficacy in managing negative emotion was stronger for middle and late adolescents than for early adolescents (Δχ2 (1) = 4.45, p < 0.05; Δχ2 (1) = 6.56, p < 0.05). In addition, parental autonomy granting was positively associated with early adolescents’ future orientation, was negatively associated with middle adolescents’ future orientation, and had a nonsignificant association with late adolescents’ future orientation (difference between early and late adolescents: Δχ2 (1) = 3.88, p < 0.05; difference between middle and late adolescents: Δχ2 (1) = 4.45, p < 0.05).

As a supplemental analysis, we also examined whether the path coefficients of the mediation model differed among adolescents with different socioeconomic statuses. The results indicated no statistically significant differences by socioeconomic status (see Appendix S2).

4 Discussion

The current study addressed an important issue: namely whether parental autonomy granting promotes adolescents’ life satisfaction in contemporary Chinese cultural contexts and what are the underlying mechanisms. We used a longitudinal design to investigate the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction and to examine the mediating roles of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation.

4.1 Autonomy Granting Parenting Practice and Life Satisfaction

Consistent with prior findings (Chai et al., 2018; Ferguson et al., 2011; Filus et al., 2019; Reed et al., 2016), the present study provides support for a model in which autonomy granting parenting practice positively predicts early and late adolescents’ life satisfaction. Parental autonomy granting may enable adolescents to have a sense of choice in their lives and engage in behaviors that are personally interesting and valuable to them. When parents provide adequate autonomy, adolescents’ basic psychological needs are more likely to be fulfilled (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2002); therefore, they can be expected to experience more satisfaction with life (e.g., Ferguson et al., 2011). However, parental autonomy granting does not significantly promote middle adolescents’ life satisfaction. Middle adolescents are in senior high school, which is a special educational period. In this period, they need more advice and guidance to cope with so many severe challenges (e.g., adapting to the fast pace of learning, studying more difficult courses, and dealing with the pressure of college entrance examination) (Moreira et al., 2018). Therefore, providing autonomy for middle adolescents may not be compatible with their needs, and it may not increase their life satisfaction.

This study expands knowledge about the role of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction beyond Western cultural contexts. Although traditional Chinese culture is characterized as collectivism (Peterson et al., 2005), it is shifting towards individualism with social change (Xu & Hamamura, 2014; Zeng & Greenfield, 2015). Individualistic cultural values such as emphasizing the self and acquiring autonomy have become widely endorsed. In this process, autonomy granting parenting practice has become more compatible with contemporary Chinese cultural contexts (Bi et al., 2020). Therefore, Chinese adolescents also tend to interpret parental autonomy granting with positive meanings and obtain benefits from this parenting practice. Notably, when interpreting the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice in the broad cultural context, the influence of the characteristics of different educational stages should also be considered.

4.2 The Mediating Effects of Emotional Self-efficacy and Future Orientation

Based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001; Lent et al., 2005), we explored the indirect effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction through the mediating roles of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation. Our findings indicated that when granted autonomy, the early adolescents tended to orient towards the future. In turn, future orientation promoted the adolescents’ life satisfaction. These results are consistent with previous research which have found that autonomy granting parenting practice was positively associated with future orientation and future orientation also was positively linked to life satisfaction (Diaconu-Gherasim et al., 2017; Su et al., 2017; Zhang & Howell, 2011). Early adolescence is a period of increasing desire for autonomy (Daddis, 2011). When granted autonomy, early adolescents have more opportunities to envision the future, make plans, and take actions to achieve future goals. They tend to feel satisfied in the process of planning for their futures and pursuing future goals. Furthermore, future orientation mediated the relationship between parental autonomy granting and the middle adolescents’ life satisfaction. However, the mediating effect of future orientation in the middle adolescent sample was different from that in the early adolescent sample. Middle adolescents who were granted more autonomy tended to have lower levels of future orientation. This finding may be explained by the fact that middle adolescents face greater challenges in senior high school (e.g., adaptation to educational transition and more academic pressure) (Moreira et al., 2018). In particular, under the stress of the college entrance examination, Chinese middle adolescents must devote a large amount of time and energy to studying and concentrating on the present tasks. In this situation, a lower level of autonomy and more guidance and advice from parents may be conducive to middle adolescents’ planning for the future (Liu & Helwig, 2020). For late adolescents, future orientation did not mediate the relationship between parental autonomy granting and life satisfaction. The possible explanation may be that late adolescents have achieved a higher level of autonomy which may enable them to be self-reliant when orienting towards the future (e.g., make plans and commit to achieving future goals). To some extent, the findings of this study were consistent with previous research which found that the effects of parenting practices on future orientation were age-dependent (Nurmi & Pulliainen, 1991). And compared with younger adolescents, parenting practice concerning controlling and autonomy had less influence on older adolescents’ future orientation (Nurmi & Pulliainen, 1991).

Concerning the relationships between parental autonomy granting and emotional self-efficacy, as expected and consistent with other research (e.g., Caprara et al., 2006), parental autonomy granting facilitated the late adolescents’ perception of their capability of expressing positive emotions, which in turn promoted their satisfaction with life. This may be due to that autonomy granting parenting practice acknowledges adolescents’ perspectives and provides opportunities for adolescents to make decisions independently (Steinberg et al., 1992). Therefore, adolescents have adequate opportunities to express individual perspectives and positive emotions, namely, to openly express joy and enthusiasm when good things happen and to manifest satisfaction with success, which is beneficial for establishing self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions. Adolescents’ self-efficacy beliefs about expressing positive emotions may facilitate their experience of positive emotions and accumulation of psychological resources, which in turn help achieve life satisfaction (e.g., Caprara & Steca, 2005; Fredrickson, 2001; Gunzenhauser et al., 2013).

In addition, the middle and late adolescents who perceived parental autonomy support also felt efficacious about managing negative emotions. This may be due to that these adolescents raised with autonomy support parenting practice have sufficient experiences of controlling their own lives and regulating negative emotions (Kagitcibasi, 2013; Roth et al., 2009). However, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions was not directly beneficial for life satisfaction but rather facilitated the adolescents’ future orientation, which in turn promoted their satisfaction with life. Consistent with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001; Lent et al., 2005), the adolescents who perceived their capability to manage negative emotions (e.g., recover from sadness, be unaffected by guilt, and control anger in irritating conditions) were more likely to make plans for the future and make progress towards their goals. As an important form of psychological capital, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions may help adolescents deal with stressful situations and orient towards the future (Kerpelman et al., 2008; Luthans et al., 2007; Zambianchi & Bitti, 2014). Furthermore, future-oriented adolescents tended to achieve more gratification from pursuing their goals rather than being tempted by immediate pleasure or dwelling on negative experiences in the past, which may lead them to experience more life satisfaction (Azizli et al., 2015; Su et al., 2017; Zhang & Howell, 2011).

In sum, concerning the mediating effects of emotional self-efficacy, self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions mediated the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and the late adolescents’ life satisfaction, whereas self-efficacy in regulating negative emotions and future orientation sequentially mediated the link between parental autonomy granting and the middle and late adolescents’ life satisfaction. Previous research also found that self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions were differently associated with developmental outcomes. The former was more related to promoting adjustment outcomes, whereas the latter was more related to eliminating maladjustment outcomes (e.g., Bandura et al., 2003; Caprara et al., 2008). The expression of positive emotions is likely to incur direct emotional benefits, fulfil adolescents’ psychological needs, and promote adaptive behaviors (Gentzler et al., 2013; Raes et al., 2012; Vanderlind et al., 2021). Therefore, the perceived self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions may directly lead to life satisfaction (Coffey & Warren, 2020; Coffey et al., 2015). However, negative emotions are associated with negative experiences or stressful situations, and managing negative emotions requires more effort. Therefore, self-efficacy in managing negative emotions might not be directly linked with life satisfaction. Instead, the positive evaluation of the capacity to deal with negative emotions helps adolescents focus on their future and achieve life satisfaction in the process of thinking and planning for the future. The current findings provide initial insights into the relationships between autonomy granting parenting practice, emotional self-efficacy, future orientation, and life satisfaction. More research is needed to differentiate the effects of self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions to better understand the relationships between these variables.

4.3 Age Differences

With regard to age differences, when their parents provided autonomy support, the adolescents in the early stage of adolescence reported lower levels of emotional self-efficacy and higher levels of future orientation than those in middle or late adolescence. Additionally, when granted autonomy by their parents, the middle adolescents were less likely to orient towards the future. The following reasons may account for these findings. First, as the critical neural region of regulating emotions, the prefrontal cortex does not reach full maturity until late adolescence (Spear, 2000). Because of the immaturity of the neural region, early adolescents may have less successful experience of regulating emotion, which may lead to lower levels of emotional self-efficacy for early adolescence. Even when provided autonomy, early adolescents are still less likely to perceive self-efficacy for emotion management. Second, early adolescents may increasingly rely on peers rather than parents as agents in the process of regulating emotions (Morris et al., 2007). Therefore, the impacts of parenting practices on emotion regulation may be weaker in early adolescence than in late adolescence, which may also result in fewer associations between parental autonomy granting and emotional self-efficacy for early adolescence. Third, some educational characteristics of senior high schools in China may lead to negative associations between parental autonomy granting and middle adolescents’ future orientation. In senior high school, middle adolescents are usually under high pressure due to academic tasks and the educational transition, and they must devote themselves to addressing present challenges (Liu & Helwig, 2020; Moreira et al., 2018). When provided more guidance and advice rather than autonomy, middle adolescents can better cope with the present situation and envision the future. In contrast, when provided more autonomy and less guidance, adolescents may struggle to cope with the present challenges rather than orient towards the future. Additionally, the present study found that the mediation model did not differ by adolescent socioeconomic status, indicating that there are similar underlying mechanisms of the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction for adolescents with different socioeconomic statuses.

4.4 Contributions, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study provides important contributions to the literature. First, by using a longitudinal design, this study enriches the literature on the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction in non-Western cultures. Second, the findings extend the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of this relationship by demonstrating that, in addition to previously discussed adolescents’ self-esteem (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2019) and psychological connectedness (Filus et al., 2019), adolescents’ emotional self-efficacy and future orientation can act as important mediators between autonomy granting parenting practice and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Furthermore, by including both mediators in the model, the present study examined the mediating roles of both emotional self-efficacy and future orientation, the relationship of each variable with the dependent variable with all other variables controlled, and the relationship between the mediators. The results indicated the importance of examining the effects of self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and self-efficacy in managing negative emotions separately instead of regarding them as a whole. Third, by separately examining the mediating effects of emotional self-efficacy and future orientation in different stages of adolescence, the findings deepen our understanding of how parental autonomy granting is linked with life satisfaction in various age groups. Fourth, the current findings have important practical implications. For example, parents should provide adequate autonomy for adolescents to facilitate their adjustment. In addition, parents should improve their childrearing practices to cultivate adolescents’ psychological capitals, which may contribute to adolescents’ positive development, including but not limited to life satisfaction. For early adolescents, parents need to focus on promoting children’s development of future orientation, whereas for middle and late adolescents, parents’ attention should be paid to nurturing both emotional self-efficacy and future orientation.

Despite the contributions, several limitations should be noted. First, this study found that the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and Chinese late adolescents’ life satisfaction was only partially mediated, suggesting that a further understanding of this relationship requires information on other mediators. Second, we relied on adolescents’ self-reports in this study. Although self-reporting is appropriate for measuring personal beliefs (e.g., emotional self-efficacy, future orientation, and life satisfaction), for autonomy granting parenting practice, utilizing information from multiple sources would be sensible in future research. Third, as this study was conducted among Chinese secondary school and college students in urban areas, cautious should be taken in the generalization of the findings to other age groups or cultural contexts. Fourth, in the research design, autonomy granting parenting practice and emotional self-efficacy were measured concurrently, as were future orientation and life satisfaction. Hence, the predictive relationship of each concurrent association was not clear. Future orientation and life satisfaction were not assessed at Time 1, which resulted in an inability to control their effects. Finally, although the attrition rate was acceptable, attrition bias is still a potential limitation. The attrition rates were different for the samples at three developmental stages. The relatively high attrition rates for senior high school and college samples may be due to the pressure of college entrance examination for the middle adolescents and the adjustment to college for the late adolescents. Additionally, the retained and the missing college samples differed significantly in self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions which was the mediator between parental autonomy granting and late adolescents’ life satisfaction. Therefore, it should be cautious when interpreting the mediating effect of self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions.

Considering these limitations, future research should explore other factors that may mediate the relationship between autonomy granting parenting practice and life satisfaction (e.g., time perspective; Kruger et al., 2008). In addition, examining the relationships between autonomy granting parenting practice, life satisfaction, and the mediating factors in various age groups and cultural contexts would help us better understand the generalizability of the findings and individual differences in the relationships between these variables. As for research design, more effort should be exerted in improving the research design. For example, future research could collect data in 3 to 4 waves to examine the temporal associations between variables in a mediation or sequential mediation model. And assessing parenting practice from multiple informants would provide more thorough understanding of this variable in different contexts. Besides, future research should take measures to minimize the attrition rates.

4.5 Conclusions

In this study, we extended previous examinations of the mechanisms underlying the effects of autonomy granting parenting practice on adolescents’ life satisfaction and provided support for the social cognitive model. Autonomy granting parenting practice is beneficial for adolescents’ life satisfaction in contemporary Chinese cultural contexts. Additionally, autonomy granting parenting practice facilitates late adolescents’ self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions and middle and late adolescents’ self-efficacy in managing negative emotions. In turn, self-efficacy in expressing positive emotions promotes life satisfaction, while the promoting effect of self-efficacy in managing negative emotions on life satisfaction is achieved through future orientation. Future orientation also mediated the relationships between autonomy granting parenting practice and early and middle adolescents’ life satisfaction. However, the mediating effect of future orientation differed in direction in the early and middle adolescent samples. This study highlights the importance of considering different developmental stages and targeting autonomy granting parental practice and these mediating factors to enhance adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the figshare repository, https://figshare.com/account/articles/12518501

Code Availability

Software application or custom code is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., & Giammarco, E. A. (2015). Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 58–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.006

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67(3), 1206–1222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01791.x

Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 74(3), 769–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00567

Barber, B. K., & Xia, M. (2013). The centrality of control to parenting and its effects. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 61–87). American Psychological Association.

Bi, X. W., Zhang, L., Yang, Y. Y., & Zhang, W. X. (2020). Parenting practices, family obligation, and adolescents’ academic adjustment: Cohort differences with social change in China. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(3), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12555

Boniwell, I., Osin, E., Linley, P. A., & Ivanchenko, G. V. (2010). A question of balance: Time perspective and well-being in British and Russian samples. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271181

Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.20.3.227

Caprara, G. V., & Steca, P. (2005). Self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.24.2.191.62271

Caprara, G. V., Steca, P., Gerbino, M., Paciello, M., & Vecchio, G. M. (2006). Looking for adolescents’ well-being: Self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of positive thinking and happiness. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 15(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00002013

Chai, W. Y., Kwok, S. Y., & Gu, M. (2018). Autonomy-granting parenting and child depression: The moderating roles of hope and life satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2596–2607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1102-8

Chughtai, A. A. (2021). A closer look at the relationship between life satisfaction and job performance. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09793-2

Cikrikci, Ö., & Odaci, H. (2016). The determinants of life satisfaction among adolescents: The role of metacognitive awareness and self-efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0861-5

Coffey, J. K., & Warren, M. T. (2020). Comparing adolescent positive affect and self-esteem as precursors to adult self-esteem and life satisfaction. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09825-7

Coffey, J. K., Warren, M. T., & Gottfried, A. W. (2015). Does infant happiness forecast adult life satisfaction? Examining subjective well-being in the first quarter century of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(6), 1401–1421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9556-x

Coffey, J. K., Xia, M., & Fosco, G. M. (2020). When do adolescents feel loved? A daily within-person study of parent-adolescent relations. Emotion. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000767

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon & N. Eisneberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1003–1067). Wiley.

Cui, L., Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Houltberg, B. J., & Silk, J. S. (2014). Parental psychological control and adolescent adjustment: The role of adolescent emotion regulation. Parenting: Science and Practice, 14(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2014.880018

Daddis, C. (2011). Desire for increased autonomy and adolescents’ perceptions of peer autonomy: “Everyone else can; Why can’t I?” Child Development, 82(4), 1310–1326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01587.x

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Diaconu-Gherasim, L. R., Bucci, C. M., Giuseppone, K. R., & Brumariu, L. E. (2017). Parenting and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: The mediating role of future time perspective. The Journal of Psychology, 151(7), 685–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1372349

Ferguson, Y. L., Kasser, T., & Jahng, S. (2011). Differences in life satisfaction and school satisfaction among adolescents from three nations: The role of perceived autonomy support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(3), 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00698.x

Filus, A., Schwarz, B., Mylonas, K., Sam, D. L., & Boski, P. (2019). Parenting and late adolescents’ well-being in Greece, Norway, Poland and Switzerland: Associations with individuation from parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 560–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1283-1

Forrest, C. B., Bevans, K. B., Riley, A. W., Crespo, R., & Louis, T. A. (2013). Health and school outcomes during children’s transition into adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.019

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fuligni, A. J. (1998). Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 34(4), 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.782

Gentzler, A. L., Morey, J. N., Palmer, C. A., & Yi, C. Y. (2013). Young adolescents’ responses to positive events: Associations with positive affect and adjustment. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(5), 663–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431612462629

Gunzenhauser, C., Heikamp, T., Gerbino, M., Alessandri, G., Von Suchodoletz, A., Di Giunta, L., & Trommsdorff, G. (2013). Self-efficacy in regulating positive and negative emotions. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 29(3), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000151

Heffner, A. L., & Antaramian, S. P. (2016). The role of life satisfaction in predicting student engagement and achievement. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1681–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9665-1

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Conjoint analyses of the students’ life satisfaction scale and the Piers-Harris self-concept scale. Psychology in the Schools, 31(4), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199410)31:4%3c273::AID-PITS2310310404%3e3.0.CO;2-A

Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Jiang, X. (2013). Assessment and promotion of life satisfaction in youth. In C. Proctor & P. Linley (Eds.), Research, applications, and interventions for children and adolescents (pp. 23–42). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6398-2_3

Kagitcibasi, C. (2013). Adolescent autonomy-relatedness and the family in cultural context: What is optimal? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12041

Kerpelman, J. L., Eryigit, S., & Stephens, C. J. (2008). African American adolescents’ future education orientation: Associations with self-efficacy, ethnic identity, and perceived parental support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(8), 997–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9201-7

Klimes-Dougan, B., Brand, A. E., Zahn-Waxler, C., Usher, B., Hastings, P. D., Kendziora, K., & Garside, R. B. (2007). Parental emotion socialization in adolescence: Differences in sex, age and problem status. Social Development, 16(2), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00387.x

Kruger, D. J., Reischl, T., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2008). Time perspective as a mechanism for functional developmental adaptation. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099336

Lent, R. W., Singley, D., Sheu, H. B., Gainor, K. A., Brenner, B. R., Treistman, D., & Ades, L. (2005). Social cognitive predictors of domain and life satisfaction: Exploring the theoretical precursors of subjective well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.429

Lightsey, O. R., Jr., Maxwell, D. A., Nash, T. M., Rarey, E. B., & McKinney, V. A. (2011). Self-control and self-efficacy for affect regulation as moderators of the negative affect–life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.25.2.142

Lightsey, O. R., Jr., McGhee, R., Ervin, A., Gharghani, G. G., Rarey, E. B., Daigle, R. P., & Powell, K. (2013). Self-efficacy for affect regulation as a predictor of future life satisfaction and moderator of the negative affect–Life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9312-4

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Liu, G. X. Y., & Helwig, C. C. (2020). Autonomy, social inequality, and support in Chinese urban and rural adolescents’ reasoning about the Chinese college entrance examination (Gaokao). Journal of Adolescent Research. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558420914082

Liu, X., Huang, X. T., & Bi, C. H. (2011). Development of the questionnaire for teenagers’ future orientation. Journal of Southwest University (social Science Edition), 37(6), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2011.06.021

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). Is mindful parenting associated with adolescents’ well-being in early and middle/late adolescence? The mediating role of adolescents’ attachment representations, self-compassion and mindfulness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1771–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0808-7

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: CA.

Niditch, L. A., & Varela, R. E. (2012). Perceptions of parenting, emotional self-efficacy, and anxiety in youth: Test of a mediational model. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-011-9150-x

Nurmi, J. E. (1991). How do adolescents see their future? A review of the development of future orientation and planning. Developmental Review, 11(1), 1–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(91)90002-6

Nurmi, J. E., & Pulliainen, H. (1991). The changing parent-child relationship, self-esteem, and intelligence as determinants of orientation to the future during early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 14(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-1971(91)90044-R

Nyhus, E. K., & Webley, P. (2013). The relationship between parenting and the economic orientation and behavior of Norwegian adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(6), 620–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2012.754398

Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Molero Jurado, M. D. M., Gázquez Linares, J. J., Oropesa Ruiz, N. F., Simón Márquez, M. D. M., & Saracostti, M. (2019). Parenting practices, life satisfaction, and the role of self-esteem in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204045

Peterson, G. W., Steinmetz, S. K., & Wilson, S. M. (2005). Parent-youth relations: Cultural and cross-cultural perspectives. Hawthorn Press.

Raes, F., Smets, J., Nelis, S., & Schoofs, H. (2012). Dampening of positive affect prospectively predicts depressive symptoms in non-clinical samples. Cognition and Emotion, 26(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.555474

Reed, K., Duncan, J. M., Lucier-Greer, M., Fixelle, C., & Ferraro, A. J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3136–3149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0466-x

Roth, G., Assor, A., Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). The emotional and academic consequences of parental conditional regard: Comparing conditional positive regard, conditional negative regard, and autonomy support as parenting practices. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015272

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). University of Rochester Press.

Seginer, R. (2009). Future orientation: Developmental and ecological perspectives. Springer.

Seginer, R., Vermulst, A., & Shoyer, S. (2004). The indirect link between perceived parenting and adolescent future orientation: A multiple-step model. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000081

Siahpush, M., Spittal, M., & Singh, G. K. (2008). Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. American Journal of Health Promotion, 23(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.061023137

Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2010). A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review, 30(1), 74–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.11.001

Spear, L. P. (2000). Neurobehavioral changes in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(4), 111–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00072

Steinberg, L. (2014). Adolescence (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Steinberg, L., Graham, S., O’brien, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., & Banich, M. (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244.x

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63(5), 1266–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x

Su, S., Li, X., Lin, D., & Zhu, M. (2017). Future orientation, social support, and psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01309

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2004). The role of life satisfaction in the relationship between authoritative parenting dimensions and adolescent problem behavior. Social Indicators Research, 66(1–2), 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000007498.62080.1e

Sun, R. C., & Shek, D. T. (2010). Life satisfaction, positive youth development, and problem behaviour among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 95(3), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9531-9

Vanderlind, W. M., Everaert, J., & Joormann, J. (2021). Positive emotion in daily life: Emotion regulation and depression. Emotion. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000944

Wang, Y. J., Dou, K., & Liu, Y. (2013). Revision of the scale of Regulatory Emotional Self-efficacy. Journal of Guangzhou University (social Science Edition), 12(1), 45–50.

Xu, Y., & Hamamura, T. (2014). Folk beliefs of cultural changes in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01066

Yap, S. T., & Baharudin, R. (2016). The relationship between adolescents’ perceived parental involvement, self-efficacy beliefs, and subjective well-being: A multiple mediator model. Social Indicators Research, 126(1), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0882-0

Zambianchi, M., & Bitti, P. E. R. (2014). The role of proactive coping strategies, time perspective, perceived efficacy on affect regulation, divergent thinking and family communication in promoting social well-being in emerging adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0307-x

Zeng, R., & Greenfield, P. M. (2015). Cultural evolution over the last 40 years in China: Using the Google Ngram Viewer to study implications of social and political change for cultural values. International Journal of Psychology, 50, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12125

Zhang, J. W., & Howell, R. T. (2011). Do time perspectives predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond personality traits? Personality and Individual Differences, 50(8), 1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.021

Zhang, J. W., Howell, R. T., & Stolarski, M. (2013). Comparing three methods to measure a balanced time perspective: The relationship between a balanced time perspective and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9322-x

Zhang, W., Wei, X., Ji, L., Chen, L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2017). Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 1117–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0664-x

Zhang, X. G., He, L. G., & Zheng, X. (2004). Adolescent students’ life satisfaction: Its construct and scale development. Psychological Science, 27(5), 1257–1260. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2004.05.068

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable, individual differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271–1288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund for High-level Talents in Shandong Women’s University (Grant number: 2019RCYJ05).

Funding

This study was funded by the Scientific Research Fund for High-level Talents in Shandong Women’s University (Grant number: 2019RCYJ05). The Scientific Research Fund for High-level Talents in Shandong Women’s University, 2019RCYJ05, Xinwen Bi

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Xinwen Bi conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript; Shuqiong Wang conceived and coordinated the study and helped to draft the manuscript; Yanhong Ji helped to draft the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and the byline order of authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee on human experimentation of Shandong Women’s University. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

The work described was original that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. Its publication has been approved by all co-authors and the responsible authorities at the institutions where the work has been carried out. No other manuscripts have been published, accepted, or submitted for publication using the same dataset.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bi, X., Wang, S. & Ji, Y. Parental Autonomy Granting and Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Roles of Emotional Self-Efficacy and Future Orientation. J Happiness Stud 23, 2113–2135 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00486-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00486-y