Abstract

An extensive literature shows that parental childcare time has increased considerably over the past decades in Western countries and that children benefit from spending time with their parents. In contrast, less is known about whether and to what extent parents benefit from spending time with their children. This article fills this gap by asking whether parents enjoy childcare, and whether an association exists between time spent doing childcare and life satisfaction. Moreover, it tests whether the association varies among parents with different working statuses, specifically by comparing full-time employed fathers with full-time employed, part-time employed, and non-employed mothers. Multivariate analyses based on nationally representative time use data for Italy (2013–2014) show that parents find childcare—especially interactive childcare activities—much more pleasant than other daily activities such as employment or housework. Furthermore, the results reveal a positive association between childcare time and life satisfaction among full-time employed parents, but not among part-time employed or non-employed mothers, pointing to important between and within gender inequalities in the costs and benefits of investments in family time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A growing body of evidence shows that parents in Western countries are spending increasing amounts of time with their children (among others: Bianchi, 2000; Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016; Gauthier et al., 2004). This finding has been positively welcomed by both the scholarly community and the wider public, because a large corpus of literature shows that children benefit from spending time with their parents, in terms of both cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes (Cano et al., 2019; Hsin & Felfe, 2014; Kalil & Mayer, 2016; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008). From this perspective, the growing amount of time that parents spend with their children is inevitably seen under a positive light and is the object of thorough investigation. But what about the parents? Is spending an increasing amount of time with their children beneficial to them? And, if so, do all parents experience positive returns from childcare time? Specifically, do full-time employed parents, known to spend less time with their children (Shelton & John, 1996), enjoy childcare more than parents who work part-time or are not employed?

While the value of childcare in terms of benefits for children has been extensively proven, and its monetary value in terms of childcare costs is beyond doubt, the question of the intrinsic, non-monetary value of spending time with one’s children is somewhat less clear (Eggebeen & Knoester, 2001; Musick et al., 2016). Using high-quality, nationally representative time-diary data for Italy, this article provides a unique contribution to the literature by investigating three issues: (1) the extent to which parents enjoy time with their children; (2) whether there exists an association between childcare time and life satisfaction; (3) whether this association varies between fathers and mothers with different levels of involvement in the labor market. It is especially interesting to study this relationship in Italy due to the country’s unique combination of extremely low fertility levels (Dalla Zuanna, 2001; OECD, 2019c), low female and maternal employment (OECD, 2019a), and underdeveloped family welfare (Esping-Andersen, 1999; Saraceno, 1994). Moreover, because of the stark differences in labor market participation not just between women and men but also among women (OECD, 2019a), the Italian case provides an excellent context in which to investigate the association between childcare time and life satisfaction among parents working full-time, part-time, or not working at all.

A great deal of previous research has focused on the relationship between parenthood and various forms of subjective well-being, such as life satisfaction and happiness (for detailed reviews see: Umberson et al., 2010; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). All these studies have in common the fact that they address the relationship between subjective well-being and parenthood as a status (i.e., being a parent) or as an event (i.e., becoming a parent), thus reflecting parents’ sense of well-being while they are away from their children. In contrast, less empirical work has addressed the relationship between subjective well-being and parenthood as an act (i.e., parenting), and few studies have asked whether parents positively evaluate the time they spend with their children (Gershuny, 2013). Furthermore, to the best of my knowledge, no recent studies have asked whether an association exists between childcare time and life satisfaction (for an early exception see Eggebeen & Knoester, 2001).

Achieving a more clear-cut answer on whether being a parent relates to happiness, life satisfaction, and subjective well-being is relevant for the scholarly community from at least two perspectives. In the first place, the pursuit of happiness is considered a central life goal in contemporary societies and even an inalienable right (for example in the United States). Considering that the great majority of adults eventually become parents even in contexts with sub-replacement fertility rates (Huijts et al., 2011; Kreyenfeld & Konietzka, 2017), the parenthood-happiness dilemma involves millions of people. In second place, considering the persistently low fertility rates in many Western countries, not only demographers but also psychologists have asked whether well-being is an important pre-condition for reproductive behavior. From a demographic perspective, this is especially relevant in countries that have sub-replacement fertility rates. Indeed, recent research suggests that happier people might be more likely to have (additional) children (Luppi, 2016; Mencarini et al., 2018).

Given that cross-national research has found large differences among countries in the relationship between parenthood and overall levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and well-being (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020), comparative research has asked whether country characteristics can act as buffers between the impact of having children and parents’ emotional well-being. In particular, studies have found a negative association between parenthood and happiness in countries that have less generous and underdeveloped policy provisions for families with children, whereas the association is positive in generous welfare states (Aassve et al., 2015; Glass et al., 2016; Pollmann-Schult, 2018). From this perspective, Italy is an interesting case study for analysis of the association between parental time with children and well-being, as the country is severely underdeveloped in terms of family welfare (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1996; Saraceno, 1994) and therefore parents cannot rely on state-level help and support to cope with the economic, time-related, and emotionally problematic aspects of parenthood like in other countries (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020).

1.1 The Relationship Between Parenthood and Well-being: A Short Review

The question of whether having children contributes to happiness, well-being, and life satisfaction has been extensively addressed in previous research. Many studies have shown that relationships and social roles play a key role in mental health (Durkheim, 1897; Glass et al., 2016; House et al., 1988). Moreover, a commonly accepted idea in society is that children are a “blessing” and that parenthood, and motherhood in particular, is the most fulfilling experience a human being can have (Hansen, 2012). Indeed, parenthood is often identified as a source of meaning and purpose in life (Fave et al., 2013; Meier et al., 2018; Musick et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2014; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). However, studies also point out that being a parent, especially when children are very young, involves multiple challenges including sleep deprivation, feelings of inadequateness, physical strain, and social isolation (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003). The birth of a child (especially a first child) can lead to profound insecurities in parents as they find themselves unprepared when faced with this major change in their lives (Luhmann et al., 2012). This can also have negative repercussions on the couple in terms of satisfaction with one’s romantic partner (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003; Twenge et al., 2003). The costs of raising children, the financial insecurity of many contemporary couples, and the inability to successfully combine work and family responsibilities can further exacerbate these difficulties (Busetta et al., 2019; Matysiak et al., 2016; Nomaguchi & Johnson, 2009).

Therefore, from a theoretical point of view, parenthood can be both negative and positive for subjective well-being and, indeed, empirical evidence on the topic is mixed. Research in the United States, for example, has found that parents are happier than non-parents (Herbst & Ifcher, 2016; Nelson et al., 2013), and in Europe, Aassve et al. (2012) and Pollmann-Schult (2014) have also found a positive relationship between parenthood and happiness and life satisfaction. Longitudinal studies have also indicated that the birth of a child has a positive effect on subjective well-being in Austria (Baranowska & Matysiak, 2011), the UK, Germany (Angeles, 2010; Balbo & Arpino, 2016; Myrskylä & Margolis, 2014), and Sweden (Switek & Easterlin, 2018). In contrast, there are several studies showing no positive association whatsoever between parenthood and well-being, while others actually found parents to be worse off than childless women and men (Alesina et al., 2004; Glass et al., 2016; Mikucka & Rizzi, 2019; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003; Stanca, 2012). These contrasting empirical findings are likely to result, at least partially, from the great variety of research designs adopted (Kohler & Mencarini, 2016; Nelson et al., 2014), which sometimes obscure various factors such as parental age, children’s age, whether childlessness is voluntary or not, and also the possible temporality of the positive returns of parenthood on life satisfaction and well-being (Aassve et al., 2015; Cetre et al., 2016; Glass et al., 2016; Hansen, 2012; Meier et al., 2018; Myrskylä & Margolis, 2014; Stanca, 2012).

1.2 Parenting, Well-being, and Life Satisfaction

While much empirical research has addressed the association between the state of parenthood and well-being, albeit with mixed results, much less is known about the relationship between the act of parenting and well-being. This is an important aspect to investigate given the increased popularity of parenting cultures that place great value on parental childcare time and considering the increasing time parents spend with their children (Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016). Yet, very little empirical evidence on the topic is available. One early example is the US study by Eggebeen and Knoester (2001), who showed that fathers who were engaged in activities with their children were more satisfied with their lives than those who did not. But what is the theoretical mechanism linking childcare time and life satisfaction? If we think about life satisfaction as “the extent to which a person finds life rich, meaningful, full, or of high quality,”Footnote 1 it is reasonable to assume that people who engage consistently in activities that they find enriching and meaningful should have higher levels of life satisfaction than those who do not. Therefore, in order to theorize on how parenting might impact parental life satisfaction, it is critical to understand how parents feel while they are with their children. If parenting entails positive emotions and a sense of meaning and satisfaction, then parents who spend a lot a time with their children might also report higher levels of life satisfaction. In contrast, if childcare time is poorly valued and considered more of a pain than a gain, then we could anticipate a negative association between childcare time and life satisfaction.

A previous research method used to find out if childcare is considered an enjoyable activity or not is the Day Reconstruction Method (DRM). The DRM employs affect ratings, mostly captured through diaries, to test which activities—childcare among others—are more enjoyable (Kahneman et al., 2004) and thus gauge parents’ (lack of) well-being while they are with their children.

Several studies have applied the DRM to investigate which activities provide greater instantaneous enjoyment, also defined as instant utility, that is, “the strength of the disposition to continue or to interrupt the current experience” (Kahneman, 1999, p. 4). The pioneering study by Kahneman et al. (2004) found that, in a sample of US women, childcare was among the least enjoyed activities, connotated by negative rather than positive feelings, much like paid work or housework. However, results from all later studies suggest the opposite. For example, the study by Gershuny (2013) that used data from 1985 to 1986 relating to the US and the UK respectively found that childcare was rated positively by both women and men, and while it did not reach the high scores of leisure and personal care, it scored well above other activities such as unpaid work. The study by Musick et al. (2016) showed that parents in the US reported higher levels of well-being in activities with their children than activities without them. Connelly and Kimmel (2015) showed that parents reported higher levels of happiness while they were engaged in some form of childcare rather than other activities. Meier et al. (2018) used time use data gathered in the US and found that while parents enjoyed time spent with their children, they reported lower levels of happiness with adolescents than with younger children. Overall, these results suggest that childcare and spending time with children is something that parents enjoy and that they are happy while doing it. Therefore, from a theoretical point of view, it is plausible that parents who spend time with their children will report greater life satisfaction than those who do not.

A further aspect to consider is whether all parents enjoy childcare to the same extent. Indeed, some studies have pointed out that fathers enjoy childcare and time spent with children more than mothers (Gershuny, 2013), while time with children is associated with feelings of stress and fatigue (Musick et al., 2016) as well as tiredness (Connelly & Kimmel, 2015; Wang, 2013) more among mothers than fathers. One possible explanation for this gender gap was proposed by Sullivan (2013), who suggested that fathers derive greater instant utility from childcare because they are involved in the better part of it, such as interactive care or fun activities. If fathers enjoy childcare time more than mothers, they might also derive greater life satisfaction from it.

While studies using the DRM have shown gender differences in the instant utility derived from childcare, less is known about how other individual characteristics might matter in this respect. One characteristic that might play a major role is employment status. Given the marginal utility argument (Connelly & Kimmel, 2015), parents who work full time and therefore spend less time with their children (Shelton & John, 1996) might value and enjoy childcare time more (Mittone & Savadori, 2009) and consequently derive greater life satisfaction from spending time in this activity than parents who are employed part-time or not employed and thus have more available time. In fact, non-employed parents might enjoy childcare less because they spend too much time doing it (Kaplan, 2009).

It is especially relevant to investigate the association between life satisfaction and childcare time among parents in different working conditions in the Italian setting due to the large differences in employment both between women and men, and among women in different stages of the life course. These and other characteristics of the Italian context are detailed in the next section.

2 The Italian Case

Italy provides an exceptional case study to elucidate the relationship between childcare time and parental well-being. There are at least three reasons for this: first, the large gender inequalities that characterize the country in terms of paid and unpaid work (Anxo et al., 2011; Dotti Sani, 2018); second, the comparatively low level of state support for families with children (Esping-Andersen, 1999; Saraceno, 1994); third, the ongoing decline in fertility rates (Dalla Zuanna, 2001; OECD, 2019c).

As for the first point, a lot of research has shown that the gender gap in domestic work, documented across the Western world, is especially acute in Italy (OECD, 2020). Moreover, studies have shown that the gender gap in housework varies over the life course and is especially wide among Italian parents of young children (Anxo et al., 2011; Dotti Sani, 2018). In terms of paid work, official statistics show that Italian women are considerably less likely to be employed than their European counterparts (OECD, 2019b). Furthermore, family life appears to have a detrimental effect on Italian women’s employment status. As can be seen from Fig. 1, which shows the employment rates of women (left panel) and men (right panel) by age group and family status (ISTAT, 2020), the employment rates among childless single women and men are very similar, namely close to 80%, across the age groups. In contrast, partnered childless women have a lower employment rate compared to their male counterparts, especially among the older age group. The gender gap in employment is widest among parents: while about 85% of partnered fathers in the 25–34 age group are employed, the figure is halved among partnered mothers (41%), reflecting the greater difficulty that young Italian women experience in the labor market. Employment is higher among older mothers (close to 60% in the 35–44 and 45–54 age groups) but still considerably lower than fathers in the same age groups (which is close to 90%). These data fit well with the notion that the male breadwinner work-family arrangement is very common among Italian couples, especially those with children (Dotti Sani & Scherer, 2018; Hook, 2015).

Employment rates by gender, age group, and family status (ISTAT, 2020)

Italy is also characterized by low welfare support for families with children. While maternity leave for employed mothers is comparatively generous, paternity leave is scant. Parental leave, whose duration varies according to which parent takes it, has a 30% replacement rate and is taken in most cases by mothers. Public childcare for children under the age of three is underdeveloped compared to other European countries (OECD, 2019d) and its availability varies greatly across regions and municipalities. The long working day of a full-time employee (9 am to 6 pm) and the relatively low (albeit growing) availability of part-time contracts (Eurostat, 2019) make work-family reconciliation a problem for Italian couples. Hence, in many cases they resort to the male breadwinner model.

The difficulty in reconciling work and family is often called upon to explain the country’s very low fertility rates (Brilli et al., 2016; Del Boca et al., 2004). Fertility rates in Western countries have dropped over past decades (Lesthaeghe, 2020), but the decline has been especially dramatic in Italy, where the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) went from 2.4 children per woman in 1970 to 1.30 in 2018, making Italy one of the countries with the lowest TFR in the OECD area (OECD, 2019c). While Italian parents have fewer and fewer children, the time invested in their offspring has nevertheless been increasing across all social strata over the past few decades (Dotti Sani, 2020), much in line with the international literature on the topic (Gauthier et al., 2004; Gimenez Nadal & Sevilla, 2012). This points toward the diffusion of new parenting styles that emphasize the importance of spending time with children for their emotional and cognitive development and well-being (Cano et al., 2019; Hsin & Felfe, 2014; Kalil & Mayer, 2016; Lareau, 2003). As is the case in other countries, the historical increase in childcare time has been larger among mothers—who are normatively expected to devote more time to their children (England & Srivastava, 2013; Hays, 1996) than fathers (Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016).

3 Hypotheses

Several hypotheses can be drawn concerning the relationship between childcare time, well-being, and life satisfaction in Italy. My first set of hypotheses regards the enjoyability of childcare. Following previous literature, I anticipate that all Italian parents will enjoy childcare more than other activities. However, given the time constraints imposed on employed parents discussed above, I expect there will be differences not just between mothers and fathers, but also between employed (full-time vs. part-time) and non-employed parents. Since employed mothers and fathers typically spend less time with their children compared to non-working parents (Shelton & John, 1996), they might consider childcare time scarce, and hence value and enjoy it more (Mittone & Savadori, 2009). Accordingly, non-employed mothers might enjoy childcare less because they are “overdoing it” (Kaplan, 2009). Hence, my first hypothesis is that full-time employed mothers and fathers will enjoy childcare more than part-time employed or non-employed mothers (H1a). Moreover, as noted above, some types of childcare are arguably more enjoyable or less taxing than others (Sullivan, 2013). In particular, parents might associate greater meaning with activities that involve active child-parent interaction such as playing with or reading to children, versus feeding or putting them to bed. Thus, I expect that all parents will enjoy interactive childcare more than physical childcare, regardless of their working status (H1b).

My second group of hypotheses regards the association between childcare time and life satisfaction. Following the same line of reasoning as above, if full-time employed fathers and mothers enjoy childcare time more, then they should also derive more life satisfaction from it than part-time employed and non-employed mothers (H2a). Moreover, if interactive childcare is more enjoyable than physical care, then I would expect all parents to derive greater satisfaction from the former than from the latter, regardless of their working status (H2b). However, because full-time employed fathers spend the least amount of time with their children in general, they might derive greater satisfaction from both interactive and physical childcare than employed (both full-time and part-time) and non-employed mothers (H2c).

4 Data, Sample, Variables, and Method

4.1 Data and Sample

The analyses were carried out on the data from the most recent Italian Time Use Survey (ITUS), collected in 2013 and 2014 (ISTAT, 2013), which provides a nationally representative sample of over 44,000 individuals living in approximatively 20,000 households. All household members aged threeFootnote 2 and above filled in a daily time use diary covering a 24-h period. During that period, the respondents reported all activities that lasted at least 10 minutes and how pleasant each activity was. As a result, the DRM could be applied. An individual questionnaire provided background information on the members of the household that participated in the survey.

The sample for the analysis consisted of a total of 4611 parents aged 25–54 living with at least one child between zero and ten years of age. I restricted the sample to parents of relatively young children because childcare needs tend to diminish as children grow up, become more autonomous, and spend more time in school and in the company of people other than their parents. The sample comprised parents living in couples as well as single parents. In line with the hypotheses, the models were run separately for full-time employed fathers (N 2115), full-time (N 984) and part-time (N 658) employed mothers, and non-employed mothers (N 734) and separate summary statistics were given. Due to limitations in the sample sizes, part-time employed and non-employed fathers were excluded from the analysis, along with unemployed parents of both genders.

4.2 Dependent Variables

To test H1a and H1b on the enjoyability of childcare time, I used the affect ratings of the various time use episodes measured in the survey. For each activity episode in the daily diary, subjects were asked to report how pleasant they found that specific time interval. The score ranged from − 3 (not at all pleasant) to + 3 (very pleasant). Respondents were instructed to evaluate the context as well as the activity and to account for other factors that influenced their emotions (such as where the activity took place and with whom). These episode-specific scores were averaged by activity to generate a single score for each activity the respondent engaged in on the diary day, with the aim of building measures of average pleasantness attributed to the various activities. Thus, the dependent variable in the first part of the study was the pleasantness (or the affect rating) of childcare. First, I used a very general variable that gauged all types of direct childcare, including (1) physical care (such as feeding, giving baths, rocking to sleep, and changing diapers), (2) interactive care (reading, talking, and playing with children), and (3) educational activities (e.g., helping with homework). Because interactive childcare (2) is arguably more meaningful and enjoyable than physical care (1), the overall variable was then broken down into these two main components to assess possible differences in the way parents feel about the different types of activities. Educational childcare activities (3) were not explored as a separate variable because too few parents engaged in this activity and the resulting estimates were extremely uncertain. The average enjoyment scores for childcare activities among the four groups of parents were compared with the enjoyment of nine other main activities: paid work (main and secondary), housework (including cooking, cleaning, and repairs), self-care (eating/drinking, showering, and other personal care), social and religious participation (volunteering, religious participation), hobbies and pastimes (including gaming, Internet, and social media), media consumption (reading newspapers and books, watching TV, listening to music), relaxation and entertainment (including activities such as going to the cinema or concerts but also relaxing and doing nothing), sports, and open-air leisure (all types of sports plus activities like fishing or hiking). Some subjects reported spending no time on certain activities: in such cases, it was not possible to estimate the average pleasantness. Therefore, the first part of the analysis was based on the subset of parents who spent at least ten minutes on the various activities during the diary day, as seen in other studies on the topic (Connelly & Kimmel, 2015).

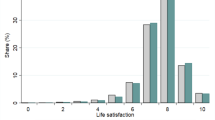

To test H2a, H2b, and H2c on the association between childcare time and life satisfaction, I relied on a different dependent variable that measures overall life satisfaction. Collected on a scale from 0 to 10, this measure is often used in the literature on subjective and cognitive well-being (CWB) (Luhmann et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2014). It differs from affective well-being (AWB), which captures emotions and moods and is considered to be more enduring (Diener et al., 2013). An especially valuable characteristic of the survey was that the question about life satisfaction was asked at the end of the diary day. It is therefore plausible to assume that the feelings developed by the respondent in reaction to the (more or less enjoyable) activities carried out during the day would have some kind of impact on the life satisfaction assessment.

4.3 Independent Variables and Controls

To test whether there was an association between childcare time and life satisfaction, the main independent variables captured hours per day spent doing overall childcare, physical childcare, and interactive childcare, as described in the previous section. Specifically, the overall childcare variable tested H2a, while hours of physical childcare and interactive childcare tested H2b and H2c. Table 1 below summarizes the hypotheses with the corresponding dependent variables.

In line with the principle of minimal marginal utility, previous studies have suggested that the more parents engage with their children, the less they gain from it (Connelly & Kimmel, 2015). Therefore, the models also included a quadratic term of the different components of childcare time to account for a possible U-shaped relationship.

To select the control variables to include in the model I adopted the approach described by Bartram (2021), who argued that control variables should be selected based on a) whether they relate to the outcome, but also b) their relationship with the key independent variables of the model. From this perspective, “good” controls are confounders, that is, associated with both the dependent variable and the main independent variable. Based on the literature discussed above, as potential confounders I included the number of children in the household (one as the reference, two, three, four, and above) and a dummy indicating whether there was a child aged two or below in the household, as both were likely to affect the time spent in childcare and life satisfaction. Another variable that met the criteria was the parents’ level of education, as it is known to be positively associated with both childcare time (Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016) and happiness and well-being (Easterlin, 2001; Yang, 2008). It was included in the models as a categorical variable with ISCED 0-1 as the reference vs. ISCED 2-3 and ISCED 4/6. I also controlled for household type (two-parent vs. single-parent) as single parents spend more time on childcare (being the main childcare provider) and because partnership predicts well-being (Yang, 2008). Finally, the models controlled for age of the parent (25–34 as the reference, 35–39, 40–44, 45–54) and geographic area of residence (north as the reference, center, south), which were expected to be associated with the dependent variable only and could therefore be considered “safe” controls (Lieberson, 1985) as they do not modify the coefficient of the main independent variable. A weighting procure was applied so that the estimates referred to an average day (Carriero & Todesco, 2018). The weighted summary statistics for all variables are presented in Table 2.

4.4 Models

To test H1a and H1b, linear regression models were used to estimate the level of enjoyment experienced by full-time employed fathers, and by full-time, part-time employed, and non-employed mothers in each type of activity, including the different types of childcare. To test hypotheses H2a, H2b, and H2c, I ran linear regression models for each group of parents where the dependent variable was life satisfaction and the main predictors were hours of overall childcare (H2a), and physical care and interactive care (H2b and H2c). Both sets of models controlled for the potentially confounding variables discussed above.

5 Results

Before moving onto the results of the multivariate analyses, it is useful to consider the baseline differences in life satisfaction, childcare time, and childcare enjoyment among the four groups of parents considered (see Table 2). First, employed parents were more satisfied with life than non-employed mothers, a result that resonates well with previous studies especially for fathers (Schrӧder, 2020), although the differences were quite small. Interestingly, part-time employed mothers were the most satisfied with their lives. Second, employed fathers spent less time in childcare compared to both employed and non-employed mothers, as found in previous research (Dotti Sani, 2020). The childcare gap between employed parents and non-employed mothers is easily explained by invoking time availability and bargaining theories (Hiller, 1984; Lyonette & Crompton, 2015). In contrast, the fact that both full-time and part-time employed mothers spent more time on childcare compared to their male counterparts could be due to different ways of complying with gender-specific expectations and normative standards of parenting behavior, much as gender theory would predict (West & Zimmerman, 1987). Interestingly, the childcare gap was concentrated in the group of less rewarding activities related to physical childcare. In fact, the average time spent on interactive childcare was roughly the same for all four groups of parents (about 30 min). This finding resonates well with the argument made by Bianchi (2000) about working mothers, who appear to protect time with their children by curtailing the time spent on other activities. In the Italian case, it appears that employed parents react to the time restrictions imposed by their working status by limiting the time spent on physical childcare, while making sure that a certain amount of time is logged into interactive care. Finally, the summary statistics suggested that fathers enjoy childcare on average more than both employed and non-employed mothers.

To test H1a and H1b, Fig. 2 shows the predicted affect ratings calculated for the main activities coded in the ITUS for employed mothers and fathers, and non-employed mothers. The average affect ratings were predicted from multivariate models that included all the controls discussed in the previous section. Owing to space limitations, only the predicted values are presented in Fig. 2.Footnote 3 As can be seen, there are remarkable similarities among groups: employed mothers and fathers, and non-employed mothers gave similar ratings to activities such as self-care, social and religious participation, entertainment, and sports. In contrast, employed mothers enjoyed housework somewhat less than employed fathers and non-employed mothers, while the latter showed a much greater appreciation of time spent in hobbies and pastimes. It was not possible to estimate affect ratings for paid work among non-employed mothers, therefore the values were only calculated for employed mothers and fathers, who evaluated paid work in roughly the same way.

Predicted affect ratings with 95% confidence intervals for main activities among employed mothers and fathers and non-employed mothers. Source: own calculation on ITUS data (2013/14). Weighted. The predictions are derived from multivariate models (not shown owing to space limitations) that control for: number of children in the household; presence of a child below the age of two; parental level of education; household type (two-parent vs. single-parent); age of the parent; geographic area of residence

Several interesting findings emerged regarding the enjoyment of childcare time. First, it appears that Italian parents do not dislike childcare at all, as the average affect ratings for this activity were higher compared to most of the other activities. However, employed fathers enjoyed doing childcare considerably more than their employed or non-employed partners, suggesting that fathers are possibly more “time hungry” than mothers and enjoy spending time with their children more. Furthermore, it is worth noting that interactive childcare ranked the highest in terms of enjoyment for employed fathers (nearly 2.5) and was also among the most appreciated activities for mothers, close to sports and entertainment. In contrast, the ratings for physical childcare were considerably lower, especially for mothers, although they did not reach the lowest levels of (non)enjoyment deriving from paid and unpaid work. Therefore, it appears that my first hypothesis (H1a) is only partially confirmed: employed fathers enjoyed childcare more than non-employed mothers but employed mothers did not appear to have the same advantage as employed fathers. In other words, the “scarcity hypothesis” applies more to working fathers than to working mothers. In contrast, H1b is fully confirmed: all parents enjoyed interactive childcare more than physical childcare.

Moving to the second set of hypotheses, I turned to the results of the multivariate models presented in Table 3 to test whether there was an association between parents’ time spent in childcare and life satisfaction. Owing to space limitations, only the null model and the model with controls are presented. The full models with stepwise introduction of the confounders are available in the Online Appendix. The results for employed fathers supported the initial expectations, as the coefficient for overall childcare time was positive and significant (β = 0.18, p ≤ 0.01). However, when I broke down the childcare variable in its two main components, the result appeared to be driven by time in physical care (β = 0.28, p ≤ 0.01), while the coefficient for interactive childcare time was positive but smaller and not statistically significant (β = 0.11, p > 0.10). Thus, it appears that the employed fathers who spent more time with their children did have higher life satisfaction, but that the returns derived from physical rather than interactive care. The results for full-time employed mothers were quite different. First, the coefficient in the null model was considerably larger than the one in the model with controls (β = 0.28, p ≤ 0.001 vs β = 0.15, p ≤ 0.05), indicating that one of the control variables was indeed a confounder. As shown in the Online Appendix, it was the presence of a child between 0 and 2 years old that increased both (physical) childcare time and life satisfaction. Beyond this important difference, in both the null model and the one with controls, the coefficient for overall childcare time was positive and statistically significant. However, what seemed to matter the most for mothers’ life satisfaction was time spent in interactive childcare (β = 0.44, p ≤ 0.001), as the coefficient for physical childcare was positive but not significant (β = 0.07, p > 0.10) once the controls were included. The coefficients for part-time employed mothers, in contrast, were all statistically insignificant in the model with controls, possibly due to the smaller sample size. Similarly, the coefficients for non-employed mothers indicated no association between childcare time and life satisfaction: the coefficients for general and physical care were close to zero and non-significant, while the coefficient for interactive care was negative and non-significant.

How do these findings map against the hypotheses? The results provide some evidence in support of the “scarcity” argument, in that we find a positive association between childcare time and life satisfaction among full-time employed but not among part-time employed and non-employed mothers. Hence, H2a appears to be confirmed. In contrast, hypotheses H2b stated that the positive relationship between childcare time and life satisfaction would be stronger for interactive rather than physical childcare activities, since the former is more meaningful (Sullivan, 2013). However, the coefficients from the models suggested that this is not the case. To provide a clearer picture of the magnitude of the effects, Fig. 3 plots the predicted values of life satisfaction by time spent on interactive childcare (top panels) and physical care (bottom panels) for the four groups of parents, estimated from the models with controls in Table 3. Starting from the top panel, we can see that the positive association between interactive care and life satisfaction was strongest among full-time employed mothers compared to other parents. A modest positive association also emerged among full-time employed fathers and, to a lesser extent, part-time employed mothers, while the slope was substantially flat for non-employed mothers. Instead, the lower panel shows that the association between physical childcare and life satisfaction was greatest among full-time employed fathers. Life satisfaction was also somewhat higher for higher levels of physical childcare among full-time employed mothers, but not significantly so. In contrast, I found no association between life satisfaction and physical childcare among part-time employed and non-employed mothers alike. Thus, contrary to H2b, it appears that interactive childcare only matters more than physical childcare for life satisfaction for employed mothers. The results also provide some support for H2c, as among fathers I observed a positive association between both types of childcare and life satisfaction, although the slope was flatter for interactive care compared to mothers.

Source: own calculation on ITUS data. Weighted. Predictions were obtained from the models presented in Table 3 that control for: number of children in the household; presence of a child below the age of two; parental level of education; household type (two-parent vs. single-parent); age of the parent; geographic area of residence

Predicted values of life satisfaction with 95% confidence intervals by time spent in interactive childcare and physical care among employed mothers and fathers and non-employed mothers.

6 Conclusions

Much previous research has addressed the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction, both from a cross-national and longitudinal perspective (Aassve et al., 2012; Balbo & Arpino, 2016; Baranowska & Matysiak, 2011; Herbst & Ifcher, 2016; Nelson et al., 2013; Pollmann-Schult, 2014; Radó, 2020; Ugur, 2020). Given its intrinsic importance, it is not surprising that the puzzle has garnered the interest of researchers from multiple disciplines. However, beyond differences in country context and methodology, most previous studies have addressed the issue by framing parenthood as a status (i.e., being a parent), or an event (i.e., becoming a parent), rather than considering the actual act of parenting and its relationship with life satisfaction.

This article provides a unique contribution to the literature by assessing the association between parental childcare time, well-being, and life satisfaction among parents with different levels of labor market involvement in Italy. Specifically, it makes three contributions to the literature. First, the article pushes the field forward by asking a) whether Italian parents enjoy childcare and b) whether there is an association between time spent in childcare (i.e., parenting) and subjective and cognitive parental well-being: life satisfaction. Due to the large inequalities in parental childcare time between genders (Chesley & Flood, 2017; Sullivan et al., 2014) and across social strata (Guryan et al., 2008; Sayer et al., 2004), assessing whether and to what extent childcare time is associated with different levels of enjoyment and life satisfaction is a critical step in uncovering inequalities in subjective well-being among parents. The advantage of looking at the relationship between life satisfaction and parenting time, rather than parenthood as a status or an event, is that childcare can be modified (both in quantity and quality) in order to maximize its benefits. In other words, while parents can decide (at least to some extent) to step up or downsize their childcare time based on how this activity makes them feel, they cannot stop being a parent and completely forego the incumbencies of parental life; at the same time, there are numerous constraints (financial, time- and health-related constraints, among others) that make having additional children a less feasible option compared to increasing childcare. Hence, by pinpointing the association between parenting and well-being, the research results enable parents to be proactive in the management of their well-being. Second, the article focuses on a country, Italy, that is known for its low levels of gender equality at the societal level, where women are overrepresented in the private, domestic field and underrepresented in the public sphere, in particular the labor market. Owing to a welfare state that relies heavily on women to shoulder domestic work and care responsibilities (Saraceno, 1994), Italian mothers are at the forefront in taking responsibility for their children and spend considerably more time on childcare compared to Italian fathers. Hence, the question of whether childcare time is enjoyable and relates to life satisfaction is especially relevant in a context such as the Italian one. Finally, the article contributes to the debate on inequalities in subjective well-being by arguing that the value of childcare time for life satisfaction is contingent on the amount of time parents can devote to this activity. Indeed, the results indicated that among four groups of parents (full-time employed fathers, full-time employed mothers, part-time employed mothers, and non-employed mothers) full-time employed parents gained the most from childcare time, providing support for the scarcity hypothesis (Mittone & Savadori, 2009).

There are some limitations to the study that must be acknowledged. The first, and most relevant, is that given the cross-sectional nature of the ITUS data, it is not possible to assess causality in the association between childcare time and life satisfaction. Indeed, it could be argued that reverse causation is at play and that parents who are more life-satisfied prefer spending time with their children compared to those who are less satisfied. It is also possible that some underlying, unobserved variable might account for both life satisfaction and childcare time. It is impossible to test whether this is the case with the current data. However, additional analyses (see Fig. A1 in the Online Appendix) suggest that the way subjects spend their time has some relationship with the way they feel about their lives. For example, additional models showed that working overtime or spending a lot of time on housework is associated with lower life satisfaction: in both cases, reverse causation seems implausible. Similarly, while unobserved characteristics might account for the positive association between life satisfaction and childcare time, it is harder to think of any unobservable characteristics that would increase the propensity to do housework and lower life satisfaction. Moreover, parents who spend more time in pleasant activities (such as leisure) report higher levels of life satisfaction. Overall, the results suggest the existence of positive and negative relationships between the way people spend their time and life satisfaction.

An additional question is whether the results account for day-to-day variations in childcare time and life satisfaction (i.e., spending more childcare on a given day provides an instantaneous effect on life satisfaction) or if they point to a more stable association between the two (i.e., spending time on childcare regularly is positively associated with overall life satisfaction). The two options are not mutually exclusive, and the data do not allow us to provide a definite answer. If life satisfaction is relatively stable from one day to the next, as suggested in the literature (Diener et al., 2013), it seems more plausible that at least for full-time employed parents having regular-to-large doses of childcare in their daily routine is positive for their life satisfaction. However, studies have also shown the importance of positive and negative daily events for satisfaction with life (Bourke et al., 2021; Maher et al., 2015). Therefore, further research is needed to assess the time-variant vs. time-invariant effect of childcare on life satisfaction.

Two further limitations could also be addressed in future research. First, non-employed fathers are not considered in the analysis due to the small sample size, reflecting the fact that this group represents a minority in the Italian population. Nonetheless, it would be worth investigating the patterns of life satisfaction and childcare in this minority too. Second, while the focus on the Italian case has the merit of providing information on an understudied topic in a context with limited family welfare and low gender equality, the results cannot be generalized beyond the Italian population. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the association between parenting and life satisfaction in other Western and non-Western countries.

In conclusion, do Italian parents benefit from spending time with their children? The answer is yes, but not all of them. Indeed, the findings show that Italian mothers and fathers do enjoy childcare, especially its interactive component, regardless of their employment status. Hence, in line with previous studies from other countries, childcare is found to be among the most enjoyed activities. However, despite its pleasantness, only full-time employed parents experience positive returns in life satisfaction for each additional hour of childcare. In contrast, among part-time employed and non-employed mothers there is virtually no association between childcare time and life satisfaction.

This inequality in life satisfaction that emerges among parents at the intersection of gender and employment status is troubling from at least two perspectives. On the one hand, finding that part-time employed and non-employed mothers do not reap much benefit from childcare when their lives are, by definition, more centered on the domestic sphere and lack the stimuli and gratifications that can come from paid employment, suggests that these mothers might be significantly hindered in their pursuit of happiness, self-fulfillment, and well-being. On the other hand, while it is clear from previous research that children benefit from parental time, it is legitimate to ask whether parents also benefit from spending time with their children. The fact that part-time employed and non-employed mothers do not benefit from childcare time should raise questions about the long-term sustainability of an ever-increasing childcare load, dictated by the culture of “concerted cultivation” (Lareau, 2003) and “intensive motherhood” (Hays, 1996), at least for these categories of mothers.

Data Availability

The Italian Time Use Survey data is made available for free from the Italian National Institute of Statistics. Any researcher can apply for the data (https://www.istat.it/it/dati-analisi-e-prodotti/microdati#MFR) but only ISTAT can distribute the data. Therefore, the author is not authorized to distribute the data used in the article.

Code Availability

All analyses were run in Stata 16 using standard syntax.

Notes

APA Dictionary of Psychology: https://dictionary.apa.org/life-satisfaction (last accessed July 2021).

Parents and guardians filled in the daily diary for children who could not read and write.

The full models are available upon request.

References

Aassve, A., Goisis, A., & Sironi, M. (2012). Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 65–86.

Aassve, A., Mencarini, L., & Sironi, M. (2015). Institutional change, happiness, and fertility. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 749–765.

Alesina, A., Tella, R. D., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 2009–2042.

Angeles, L. (2010). Children and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 523–538.

Anxo, D., Mencarini, L., Pailhé, A., Solaz, A., Tanturri, M. L., & Flood, L. (2011). Gender differences in time use over the life course in France, Italy, Sweden, and the US. Feminist Economics, 17(3), 159–195.

Balbo, N., & Arpino, B. (2016). The role of family orientations in shaping the effect of fertility on subjective well-being: A propensity score matching approach. Demography, 53(4), 955–978.

Baranowska, A., & Matysiak, A. (2011). Does parenthood increase happiness? Evidence for Poland. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 307–325.

Bartram, D. (2021). Cross-sectional model-building for research on subjective well-being: Gaining clarity on control variables. Social Indicators Research, 115, 725–743.

Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography, 37(4), 401–414.

Bourke, M., Hilland, T.A. & Craike, M. (2021). Daily physical activity and satisfaction with life in adolescents: An ecological momentary assessment study exploring direct associations and the mediating role of core affect. Journal of Happiness Studies. Online first.

Brilli, Y., Del Boca, D., & Pronzato, C. D. (2016). Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and children’s development? Evidence from Italy. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(1), 27–51.

Busetta, A., Mendola, D., & Vignoli, D. (2019). Persistent joblessness and fertility intentions. Demographic Research, 40, 185–218.

Cano, T., Perales, F., & Baxter, J. (2019). A matter of time: Father involvement and child cognitive outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(1), 164–184.

Carriero, R., & Todesco, L. (2018). Housework division and gender ideology: When do attitudes really matter? Demographic Research, 39, 1039–1064.

Cetre, S., Clark, A. E., & Senik, C. (2016). Happy people have children: Choice and self-selection into parenthood. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 445–473.

Chesley, N., & Flood, S. (2017). Signs of change? At-Home and breadwinner parents’ housework and child-care time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(2), 511–534.

Connelly, R., & Kimmel, J. (2015). If you’re happy and you know it: How do mothers and fathers in the US really feel about caring for their children? Feminist Economics, 21(1), 1–34.

Dalla Zuanna, G. (2001). The banquet of Aeolus: A familistic interpretation of Italy’s lowest low fertility. Demographic Research, 4(5), 133–162.

Del Boca, D., Pasqua, S. & Pronzato, C. (2004). Why are fertility and women’s employment rates so low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. IZA Discussion Paper Series, 1274.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Dotti Sani, G. M. (2020). Is it “Good” to have a stay-at-home mom? Parental childcare time and work-family arrangements in italy, 1988–2014. International Studies in Gender, State & Society.

Dotti Sani, G. M. (2018). Time use in domestic settings throughout the life course: The Italian Case. Springer.

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Scherer, S. (2018). Maternal employment: Enabling factors in context. Work, Employment and Society, 32(1), 75–92.

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Treas, J. (2016). Educational gradients in parents’ child-care time across countries, 1965–2012. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(4), 1083–1096.

Durkheim, É. (1897). Suicide: A study in sociology, Translated by J. Spaulding and G. Simpson, ed., New York: Free Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Life cycle welfare: Trends and differences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 1–12.

Eggebeen, D. J., & Knoester, C. (2001). Does fatherhood matter for men? Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 381–393.

England, P., & Srivastava, A. (2013). Educational differences in US parents’ time spent in child care: The role of culture and cross-spouse influence. Social Science Research, 42(4), 971–988.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Eurostat. (2019). Part-time employment and temporary contracts - annual data. Retrieved 13 Oct, 2020 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

Fave, A. D., Brdar, I., Wissing, M. P., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). Sources and motives for personal meaning in adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 517–529.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The “Southern Model” of Welfare in Social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37.

Gauthier, A. H., Smeeding, T. M., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2004). Are parents investing less time in children? Trends in selected industrialized countries. Population and Development Review, 30(4), 647–672.

Gershuny, J. (2013). National utility: Measuring the enjoyment of activities. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 996–1009.

Gimenez Nadal, J. I., & Sevilla, A. (2012). Trends in time allocation: A cross-country analysis. European Economic Review, 56(6), 1338–1359.

Glass, J., Simon, R. W., & Andersson, M. A. (2016). Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology, 122(3), 886–929.

Guryan, J., Hurst, E., & Kearney, M. (2008). Parental education and parental time with children. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23–46.

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and Happiness: A Review of Folk Theories Versus Empirical Evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 29–64.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press.

Herbst, C. M., & Ifcher, J. (2016). The increasing happiness of US parents. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(3), 529–551.

Hiller, D. V. (1984). Power dependence and division of family work. Sex Roles, 10(11–12), 1003–1019.

Hook, J. L. (2015). Incorporating “class” into work-family arrangements: Insights from and for Three Worlds. Journal of European Social Policy, 25(1), 14–31.

House, J. S., Landis, K., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social Relationships and Health. Science, 241, 540–545.

Hsin, A., & Felfe, C. (2014). When does time matter? Maternal employment, children’s time with parents, and child development. Demography, 51, 1867–1894.

Huijts, T., Kraaykamp, G., & Subramanian, S. V. (2011). Childlessness and psychological well-being in context: A multilevel study on 24 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(1), 32–47.

ISTAT. (2013). Indagine Multiscopo sulle Famiglie. Uso del Tempo Anno 2013–2014.

ISTAT. (2020). Indagine sulle Forze Lavoro. Individui per ruolo in famiglia: condizione occupazionale. Retrieved 16 June 2021 from https://www.istat.it/it/lavoro-e-retribuzioni?dati

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–1780.

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). Russel Sage Foundation.

Kalil, A., & Mayer, S. E. (2016). Understanding the importance of parental time with children: Comment on Milkie, Nomaguchi, and Denny (2015). Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 262.

Kaplan, B. (2009). Good news and bad news on parenting. Retrieved 16 Sep, 2020 from https://www.chronicle.com/article/good-news-and-bad-news-on-parenting/.

Kohler, H.-P., Behrman, J. R., & Skytthe, A. (2005). Partner + Children = Happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 407–445.

Kohler, H.-P., & Mencarini, L. (2016). The parenthood happiness puzzle: An introduction to special issue. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 327–338.

Kreyenfeld, M. & Konietzka, D. (2017). Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, causes, and consequences Kreyenfeld, Michaela and Konietzka, Dirk, ed., Rostock, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2020). The second demographic transition, 1986–2020: Sub-replacement fertility and rising cohabitation—a global update. Genus, 76(1), 1–38.

Lieberson, S. (1985). Making it count: The improvement of social research and theory. University of California Press.

Lugo-Gil, J., & Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2008). Family resources and parenting quality: Links to children’s cognitive development across the first 3 years. Child Development, 79(4), 1065–1085.

Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: a meta-analysis. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(3), 592.

Luhmann, M., Lucas, R. E., Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2013). The prospective effect of life satisfaction on life events. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 39–45.

Luppi, F. (2016). When is the second one coming? The effect of couple’s subjective well-being following the onset of parenthood. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 421–444.

Luppi, F., & Mencarini, L. (2018). Parents’ subjective well-being after their first child and declining fertility expectations. Demographic Research, 39, 285–314.

Lyonette, C., & Crompton, R. (2015). Sharing the load? Partners’ relative earnings and the division of domestic labour. Work, Employment and Society, 29(1), 23–40.

Maher, J. P., Pincus, A. L., Ram, N., & Conroy, D. E. (2015). Daily physical activity and life satisfaction across adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 51(10), 1407–1419.

Matysiak, A., Mencarini, L., & Vignoli, D. (2016). Work-family conflict moderates the relationship between childbearing and subjective well-being. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 355–379.

Meier, A., Musick, K., Fischer, J., & Flood, S. (2018). Mothers’ and fathers’ well-being in parenting across the arch of child development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(4), 992–1004.

Mencarini, L., Vignoli, D., Zeydanli, T., & Kim, J. (2018). Life satisfaction favors reproduction: The universal positive effect of life satisfaction on childbearing in contemporary low fertility countries. PloS one, 13(12), e0206202.

Mikucka, M., & Rizzi, E. (2019). The parenthood and happiness link: Testing predictions from five theories. European Journal of Population. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09532-1

Mittone, L., & Savadori, L. (2009). The scarcity bias. Applied Psychology, 58(3), 453–468.

Musick, K., Meier, A., & Flood, S. (2016). How parents fare: Mothers’ and fathers’ subjective well-being in time with children. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 1069–1095.

Myrskylä, M., & Margolis, R. (2014). Happiness: Before and after the kids. Demography, 51(5), 1843–1866.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). In defense of parenthood: Children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychological Science, 24(1), 3–10.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846.

Nomaguchi, K., & Johnson, D. (2009). Change in work-family conflict among employed parents between 1977 and 1997. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 15–32.

Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. (2003). Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 356–374.

Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 198–223.

OECD. (2019a). LMF1.6: Gender differences in employment. Retrieved 14 Sep, 2020 from http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm.

OECD. (2019b). LMF1.6: Gender differences in employment outcomes. Retrieved 25 Nov, 2020 from http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm.

OECD. (2019c). OECD Family Database. Chart SF2.1.A. Total fertility rate, 1970, 1995 and 2017. Retrieved 15 Sep, 2020 from http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm.

OECD. (2020). OECD Family Database. LMF2.5 Time used for work, care and daily household chores. Retrieved 14 Sep, 2020 from http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm.

OECD. (2019d). PF3.2: Enrolment in childcare and pre-school. Retrieved 15 Sep, 2020 from http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2018). Parenthood and life satisfaction in Europe: The role of family policies and working time flexibility. European Journal of Population, 34(3), 387–411.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 319–336.

Radó, M. K. (2020). Tracking the effects of parenthood on subjective well-being: Evidence from Hungary. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 2069–2094.

Saraceno, C. (1994). The ambivalent familism of the Italian welfare state. Social Politics, 1(1), 60–82.

Sayer, L. C., Gauthier, A. H., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2004). Educational differences in parents’ time with children: Cross-national variations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1152–1169.

Schrӧder, M. (2020). Men Lose Life Satisfaction with Fewer Hours in Employment: Mothers Do Not Profit from Longer Employment—Evidence from Eight Panels. Social Indicators Research, 152, 317–334.

Shelton, B. A., & John, D. (1996). The division of household labor. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(1), 299–322.

Stanca, L. (2012). Suffer the little children: Measuring the effects of parenthood on well-being worldwide. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(3), 742–750.

Sullivan, O. (2013). What do we learn about gender by analyzing housework separately from child care? Some considerations from time-use evidence. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(2), 72–84.

Sullivan, O., Billari, F. C., & Altintas, E. (2014). Fathers’ changing contributions to child care and domestic work in very low-fertility countries the effect of education. Journal of Family Issues, 35(8), 1048–1065.

Switek, M., & Easterlin, R. A. (2018). Life transitions and life satisfaction during young adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 297–314.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574–583.

Ugur, Z. B. (2020). Does having children bring life satisfaction in Europe? Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(4), 1385–1406.

Umberson, D., Pudrovska, T., & Reczek, C. (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 612–629.

Vanassche, S., Swicegood, G., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effects of marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 501–524.

Wang, W. (2013). Parents’ time with kids more rewarding than paid work-And more exhausting. Pew Research Center.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151.

Yang, Y. (2008). Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: An age-period-cohort analysis. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 204–226.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The authors confirm that the research reported in this manuscript complies with the Springer editorial policy regarding ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The authors confirm that the research reported in this manuscript complies with the Springer editorial policy regarding consent by human participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dotti Sani, G.M. The Intrinsic Value of Childcare: Positive Returns of Childcare Time on Parents’ Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Italy. J Happiness Stud 23, 1901–1921 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00477-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00477-z