Abstract

The current debate on demographic change often revolves around seniors (over 65 years old), their housing preferences, and their spatial mobility. Our study asked future retirees between age 50 and 60 whether they intend to keep their current residence or whether they are considering moving to some other place upon retirement. The study applied a mixed-method approach, combining qualitative and quantitative methods. It was conducted in nine German cities with different spatial structural characteristics. This research contributes to current research as the prospective perspective of potential movers, movers, and non-movers pays close attention as well as the reasons for planning and not planning to move. The analysis of the vast amount of data (140 qualitative interviews and 5500 questionnaires) shows extraordinarily high satisfaction with residents’ current housing situation. The results reflect a high attachment with the place of residence and the surrounding neighborhood. The partly high rates of home ownership give reason to expect continuously high levels of remaining in place among future senior citizens. The few potentially mobile ones intend to either move within the region or use their second residences more frequently so that they are likely to live in multiple locations in the future “Aging in place” therefore proves to be the main preference among future seniors in Germany.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

So far, little is known about the lifestyles of the future older adult generation in Germany and what expectations they might have regarding housing, living arrangements, and places of residence. Current academic debate on residential mobility and housing preferences of senior citizens mostly addresses two opposing processes: While some assume that in terms of lifestyles and choice of residence those approaching retirement age will follow the same behavioral patterns as current senior citizens and leave the cities for the suburbs upon retirement (e.g., Hirschle and Schürt 2008, p. 217), others expect them to be moving back to the cities, following a transgenerational trend of reurbanization and urban “renaissance” (e.g., Brühl et al. 2005; this will be further discussed in Sect. 3). In our study, we focus on the earlier baby boomers, i.e., the cohorts born between 1945 and 1958,Footnote 1 currently approaching retirement age. In contrast to today’s senior citizens, i.e., those currently 65 and older, we expect that the earlier baby boomers will show markedly different behavioral patterns once they are senior citizens (Kramer and Pfaffenbach 2007). This is based on the assumption that their expectations and abilities differ due to having experienced greater opportunities in education, emancipation, and participation in public processes. As young adults, this first post-war generation was involved in and exposed to numerous changes, i.e., the period of social transition and general value change in the late 1960s. Its members belong to the group who were the first to have been affected by individualization and to have benefitted from the early stages of the expansion of education opportunities (see inter alia, Beck 1986, p. 127; Inglehart 1998, p. 85 ff.; Schäfers 1995, p. 305), impacting women of this age group in particular. The women currently approaching retirement age were not only exposed to considerably better educated compared to their mothers, but they will have greater financial resources at their disposal than today’s female retirees since many of them were or have been gainfully employed. For the most part, the current generation of retirees possesses some degree of wealth, which will likely not be true to the same extent for the future generation of retirees. The latter generation has been subject to temporary employment, unemployment, and increasingly to (false) self-employment to a much greater extent than the previous one. These discontinuous work histories will affect the level and security of expected retirement benefits and thus lead to tomorrow’s retirees being in a different position than today’s retirees. Based on these developments, we expect that they will develop different lifestyles, which will likely lead them to prefer different (residential) locations.

In this article, we therefore explore the following questions: Will the next generation of retirees stay where they currently live or will they move to a place that is better suited to realize their conceptions of life?Footnote 2 When we speak of conceptions of life, we refer to plans the cohort approaching retirement age has, namely plans concerning the future places of residence, forms of living, and future lifestyles, but also views on aging and provisions for old age. Answers to these questions are relevant from an urban and social geography perspective, particularly because future senior citizens’ choices of residential location can be expected to have a strong impact on the development of spatial structures, e.g., the housing market and infrastructure.

We will outline our conceptual framework and our methodological approach in Sect. 2. The central chapters of this paper are Sects. 3 and 4: We will first delineate the current state of research on preferred living arrangements and migration intentions and then proceed to discuss the findings of our research study. Demographic changes show very particular characteristics in unified Germany, and the topic is of rather large interest to the general public and stakeholders, which is why the main body of literature is in German.Footnote 3 We would like to take this opportunity and give an international audience an overview on the German debate.

2 Methodology

In social science research on aging, social status and other factors that define the circumstances of a person’s life, e.g., retirement benefits and the level of education, provide the framework of action for senior citizens. However, these external influences affect action only via subjective perception and interpretation (Amrhein 2004, p. 68). Apart from the financial situation (economic capital) and level of education (cultural capital), the network of family and friendship relationships (social capital) as well as physical and mental well-being (body capital) is crucial as well. The increasing differentiation among the older adults by age and other socio-demographic characteristics is of major significance as it can result in a variety of different motives for choice of residence and therefore housing preferences.Footnote 4

In addition to considering respondents’ micro-perspective, the macro-perspective will also be taken into account through distinguishing places of residence by location and characteristics relating to spatial structure. Structural parameters constructing the larger framework are, first and foremost, the residence’s physical features, i.e., size or accessibility, as well as availability and accessibility of transportation and other infrastructure. The economic conditions in the region, such as the housing and job market as well as purchasing power, must also be considered.

We conducted our data collection in nine German cities and chose them to represent different spatial structural characteristics. Munich and Berlin were chosen as two metropolises with very different job and housing markets.Footnote 5 Mannheim, Bochum, and Leipzig represent major cities in prospering, shrinking, and growing regions, respectively. Aachen and Karlsruhe stand for large cities that do not belong to a greater metropolitan area. Schwerin and Kaiserslautern, both mid-sized cities, are exemplary for medium-scale urban environments in East and West Germany (see Table 1). In each of these cities, we conducted our survey in at least three (in most cases in five) different districts. In eight of the nine cities, we also surveyed and interviewed tomorrow’s retirees in one or two suburban communities connected to our targeted cities. The city of Bochum was excluded hereof due to the settlement structure it is located in. We included the suburban communities to be able to compare life in the city with life in the suburbs and to be able to trace (potential) moves back to the cities.

Our empirical methodology relied on a mixed-methods approach that used both quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. For this purpose, a random sample of residential addresses in the respective age group was obtained from local residents’ registries. In all of the large cities, next to the standardized interviews we conducted between 13 and 35 qualitative interviews, a total of 140 qualitative interviews. The standardized survey sought to portray current living arrangements, the assessments thereof, and plans for the near future as well as the respondents’ employment, financial and health situation. The qualitative interviews addressed issues such as actual lifestyles, age-related stereotypes, conceptions of life, and residential preferences.

The rather elaborate questionnaire comprised 54 questions on twelve pages and was sent out by regular mail. After completing the questionnaire, they were returned by mail by the respondents (self-completed). In total, 5500 questionnaires were returned, amounting to a response rate of 29 % across all communities (ranging from 24 to 35 %; in some suburban communities the rate exceeded 50 %), which can be rated as an exceptionally high return rate for this kind of procedure. However, owed to the written form of the survey, respondents with little command of the German language, originating from countries other than Germany, with little formal education and who are functional illiterates are underrepresented in this study.

The analysis in this contribution revolves around questions concerning the approaching transition to retirement. In the following, we will discuss trends of residential preferences among the generation 50+ in two steps: First, we will discuss whether the respondents plan on moving and where they intend to be moving to. We will also investigate whether these plans reflect patterns of suburbanization, reurbanization, or moving to Europe’s “sunny south” and we will also analyze the corresponding underlying motives. In our second step, we will explore if places of residence can be distinguished according to whether their residents would like to continue living there and, if so, what motivates them to stay at their current residence and location. Since international comparisons have shown what is called “aging in place” to be the main preference among senior citizens, this paper will also address in detail the main reasons for wanting to stay in one’s current home. The aging in place trend is particularly evident in Germany. The reasons for plans on staying put have rarely been investigated in detail, which is why this article will devote equal attention to both the reasons for staying and the reasons for moving.

3 Should I go …

Although the well-known song asks “Should I stay or should I go?”, we will start our analysis with the moving part as it has been given more attention in the literature than the staying part. Previous studies on mobility of senior citizens have mostly concluded that migration rates generally decline with age and that a slight increase in residential mobility can be observed only at a very old age due to the need for care (Wagner 1989; Bucher and Heins 2001; Friedrich 2009; Friedrich and Warnes 2000). More recent studies, however, expect a rise in mobility among the young–old (Eichener 2001; Heinze et al. 1997).

When taking a closer look at migration among the young–old, we notice that previous research distinguishes three types of retirement migration: amenity migration, assistance migration, and return migration (Wiseman 1980, p. 149; Rogers and Watkins 1987), which can be further differentiated by distance. International retirement migration is usually explained in terms of previous vacation experiences of the current retirees. These retirement migrants frequently have cultivated a transnational lifestyle (Breuer 2005; Williams et al. 1997) or live in multi-local arrangements (Kaiser 2011). Biographical retirement migration studies have furthermore shown that a change of residence is more closely connected to changes in family history than to changes in employment history (Flöthmann 1997, p. 45). In regard to the generation approaching retirement age, this could mean that children leaving home, separating from or death of one’s partner or spouse, entering a new relationship, or other changes in a person’s private life are more likely to lead to a change of residence than retirement (Hansen and Gottschalk 2006). Migration patterns and motives of the young–old show that retirement migration frequently occurs along the lines of family networks or a family’s previous places of residence even if it does not involve directly moving in with family members (Lundholm 2010). This also holds true for countries with high standards in the provision of institutional care, such as Sweden (Pettersson and Malmberg 2009, p. 354). Most studies emphasize individual characteristics such as age, income, education, family status, and state of health in the sense that they are perceived as individual resources. However, migration experiences, attachments to place, and social networks must also be taken into consideration (Wiseman 1980, p. 145).

When analyzing migration processes, we must adopt not only a social structurally but also a regionally differentiated perspective for a number of reasons. For example, the options available in a situation where children have left home or the spouse has deceased are different in a relaxed housing market compared to a tight, high-priced housing market such as Munich. For this reason, the following analysis is centered on a detailed differentiation of both individual factors and contextual circumstances.

3.1 Housing preferences upon retirement in Germany: suburbanization, reurbanization, or a place in the sun?

Although young families on a good income are generally perceived as the main agents of suburbanization, in Germany households of all ages and sizes have taken to move to the suburbs. A detailed look at the age structure of migration processes reveals that the central cities in Germany show an overall negative migration balance for the age group of 65 and older, whereas the suburban communities continue to remain the winners in this age segment (see also Bucher and Heins 2001, p. 123 f.; Hirschle and Schürt 2008, p. 217).Footnote 6 This pattern can be found in a number of dynamic metropolitan areas, particularly for Frankfurt/Main, Hamburg, Stuttgart, and Munich with tight housing markets.

In 2010, the domestic migration balances of the 50- to 65-year-olds in Germany in comparison with the same-aged population for West German urban regions were −1.1, in West German rural regions, they were +1.8, and in East German regions, they were +0.5 with scenic rural regions being preferred in both East and West Germany. The domestic migration balances for those 65 and older show in the same direction albeit on a slightly lower level. In both cases, the balance for urban regions is negative, whereas the balance for rural regions is positive. These balances are contrary to those of the younger population, whose migration moves are decidedly from rural to urban regions (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) 2012).

In recent years in Germany, there has been an intensive debate on the “renaissance of the cities” or in other words, on reurbanization (e.g., Herfert 2002; Brühl et al. 2005; Kuhn 2007; Rauterberg 2005; Glatter and Siedhoff 2008; Haase 2008) although current data do not provide any evidence for a significant influx of senior citizens (Sturm and Meyer 2008, p. 243; Adam and Sturm 2012; Hesse 2012, p. 101).Footnote 7 It is rather the young population, who primarily dominate the migration flows and are therefore responsible for reurbanization (Gans et al. 2010, p. 56; Wörmer 2010; Bucher and Schlömer 2012). Hesse (2008, p. 416) on the other hand, perceives this process to be more of an expression and consequence of discursive constructions and less the product of actual population movements and labor market developments in the cities.

Another mobility trend that plays an increasing role among the current and future German senior generations is moving to the sunny south of Europe (e.g., Friedrich and Kaiser 2001; Breuer 2004, 2005; Buck 2005).Footnote 8 Here quantification remains difficult even though these processes have a considerable impact on the target regions. In addition, migration to the European south is often a seasonal phenomenon and often implies living in a second residence. The phenomenon of multi-locality is motivated by the desire to take advantage of the benefits of both worlds without having to give up keeping in touch with family and friends, yet is difficult to measure (Breuer 2004, p. 129; Friedrich 2009; Wahl 2001; Kordel 2013).

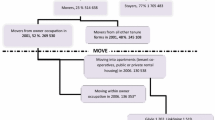

This investigation collected data on future plans of residence in a two-step procedure: First, we asked the participants whether they could imagine moving their residence once they or their partner retires and, if so, where would they move to. In a second step, we asked participants whether they already have specific plans of moving to any of the imagined future locations upon retirement. The results for the responses to the two questions are compiled in Table 2. Nearly half of the respondents (47 %) stated that they could imagine moving their residence. With the exception of Berlin, all the cities and regions where the respondents plan on moving to feature flourishing economies, fairly low unemployment rates, and above average purchasing power.Footnote 9

Unlike that plans of moving can be viewed as signs of individual prosperity (e.g., in the case of amenity migration), the qualitative interviews revealed where relocation plans were motivated by fears of no longer being able to afford the current residence once retired (e.g., in Munich; see Kramer and Pfaffenbach 2009). Conversely, the regions where only few respondents had plans to move are often the ones that have only recently been targets of migration (suburban communities in the Eastern German states), which becomes evident when looking at the individual residential biographies. The decision to move recently made is apparently not questioned again.

Only about 7 % of the respondents in the survey agreed to the question “Are you planning to move upon retirement?”, with roughly half of those “imagining” moving their residence. Those willing to move frequently live directly in large cities (e.g., Munich, Berlin) and less often in the surrounding suburban areas. The most frequent destinations of the few planned moves are, in this order, the same city/community, other cities in Germany, followed by destinations abroad, and suburban communities, findings which are consistent with formerly observed regional patterns. We could not discern a trend toward reurbanization in any of the targeted cities. Due to the lack of intended moves, we refrained from further analyzing possible reurbanization processes.

3.2 Housing and migration preferences upon retirement in Germany: differences by individual characteristics

Next to the above-discussed contextual influencing factors when deciding on where to take up residency, individual criteria such as gender, age, or owning property are of importance and will be analyzed more closely in the following. The survey analysis showed that there is no apparent gender difference while considering the willingness to move, the targeted destinations, and the housing situations envisioned in the plans among individuals and household characteristics. The younger respondents (51–55 years of age) mention more frequently (9 %) that they have specific plans of moving upon retirement than the older ones (56–61 years of age), of whom only 7 % state having specific plans although they are much closer to retirement.

Although home ownershipFootnote 10 serves as an indicator of ties to the place of residence, there are major differences between East and West Germany and between urban and the suburban areas in this respect (Fig. 1). Whereas only 10–12 % of the respondents in eastern districts of Berlin and Leipzig (both former German Democratic Republic) live in their own homes, home ownership reaches about 60 % in mid-sized West German cities such as Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Aachen, and Kaiserslautern. In the city of Munich, the percentage of homeowners (i.e., owner occupants) is also quite low, which is a consequence of the very high-priced housing market there.Footnote 11

When looking at the differences between the living situation of couples and singles, we see that half of the couples live in homes they own, whereas this is only true for roughly one-third of singles (a weakly positive correlation of 0.17 at a level of significance of 0.01). That means that there are differences in the strength of ties to one’s residence in respect to both family status and home ownership. This is reflected in the fact that while 9 % of the tenants are planning to move upon retirement, less than 6 % of the homeowners intend to do so (the correlation is weakly positive at 0.13 at a level of significance of 0.01). Our results thus confirm the well-known “ties to place,” which seems to have a strong influence on the older generation, whereas renters are more likely to consider to relocating.

Studies concerned with “place identity” (Wiles et al. 2009) mostly assume that place attachment increases with the length of residence (Weichhart et al. 2006, p. 58 f.; Kappler 2013). That could result in the expectation that plans of changing residence are less likely the longer people have lived at the same residence. This holds true only for those respondents of the survey who were born in their current locality, of whom only about 6 % plan to move. However, there is no linear relationship between how long the respondents have been living at their current location and plans for relocating. Most of those who are considering to move are among the group of respondents who have been living in their current home for 5–10 years. The parabolic relationship between plans of moving and length of residence can be explained along the following lines: Long-time residents have strong ties to the location, which keep them from moving. Residents who have moved to a new location recently do not plan to move again. This is especially true for respondents from East German suburban locations. One could assume that the rather recent decision has already led to achieving the best situation currently possible. However, we did notice an influence of social relationships: Those who are in touch with their children on a daily basis (and probably live in close proximity) less often have plans of moving upon retirement compared to those who are not in touch with their children as frequently.

The findings of the quantitative survey were additionally tested in a logistic regression model, which was incrementally optimized and which reached an explained variation of 25 % (Kappler 2013, p. 233, using the same data). The highest values in respect to moving intentions can be found for respondents with a high income, with mainly West German residential biographies, those living in rented residences, and those unmarried (regression coefficient B = 0.4*** to B = 0.8***). A strong influence is also exerted by various residence characteristics (size, costs, location, age appropriateness), especially if they are negatively appraised (regression coefficient B = 0.5*** to B = 0.8***) (Kappler 2013, p. 234, using the same data).

4 … or should I stay?

According to numerous studies, 80 % of the current senior citizens wish to stay on living where they are now (Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen 1996; Friedrich 2002; Schneider-Sliwa 2004; Zaugg et al. 2004). That this trend will increase can be derived when looking at the continuously declining domestic migration rates of those 65 and older (cp. Friedrich 2009). Based on a statistical evaluation of interregional migration flows, Hirschle and Schürt (2008, p. 218) reach the conclusion that the generation 50+ is less mobile than could be excepted when looking at the results of other studies addressing relocating upon retirement (cp. Sect. 3.1).

The persistency trend divides into two spatially distinct dimensions: One is intra- and interregional migration happening on a smaller scale (e.g., sub- and reurbanization, see Sect. 3) and the other dimension being “aging in place,” a much discussed phenomenon. Aging in place is not limited to staying in the same municipality or part of town, but means not moving at all. How strong the attachment to the place or bonding to the immediate physical and social environment is obviously dependent on how long someone has lived at a given location and how familiar they are with the surroundings. This attachment is further increased when people own the property they live in. Especially in Germany, where the rate of owned property is low in international comparison, owning property often creates strong emotional ties. Selling property therefore is often not only not wanted but also it might imply financial losses. If the sales price of the property one lives in is low, it can lead to refraining from moving altogether even if a move generally speaking would be an option (Glasze and Graze 2007, p. 472). In situations like those, people might even feel forced to age in place.

In the face of an increase in life expectancy, gerontology utilizes the aging in place concept mainly when it comes to old–old individuals or when comparing young–old and old–old individuals (Oswald et al. 2007, 2010), and in the latter case, it is tied to stationary care at home. Instead of moving to an age-appropriate apartment or a care facility, often considerable investments are made to altering, renovating, or installing new amenities into the existing home at a younger age so that one can stay in place when one’s mobility begins to be limited (Oswald et al. 2003, p. 60p.). In the context of our study, aging in place refers to potential moving plans upon retirement since our respondents belong to the cohort of the 50–60 year old and the plans they make predominantly are made for when being young–old. So far, this age group has received little attention in gerontological studies, and to our knowledge, for Germany there are no studies that focus on the prospective perspective of the living situation of the older generation. The question which decisions will be made when very old and the need for caregiving arises can not, however, be answered based on our results.

In the following discussion, we distinguish between where the residence is located (suburban community or city district) and the home as such. We base our analysis on the hypothesis that the future senior citizens will show a preference for staying in their current residence if they are very happy with were they live and if their residential biography shows only few moves (i.e., few moves, having lived in the current residence for a long time). We further hypothesis that the preference to remain at the current residence is especially pronounced among those respondents that are (very) satisfied with their financial situation, that expect to be able to afford their residence once retired, and that own their current residence. In the following, we will first describe our findings differentiated spatially (Sect. 4.1) and we will then proceed to explain our findings based on our statistical analyses and the results of the qualitative interviews we conducted (Sect. 4.2).

4.1 Preferences for persistence upon retirement in Germany

The survey results reveal that a slim majority (51 %) would prefer no changes at all upon retirement in regard to their current living arrangements. However, regional comparison reveals considerable differences: Intentions of staying in the current place of residence are highest in East German regions, which have witnessed high levels of migration in the past two decades. At first sight, this seems surprising since the respondents have not lived where they do now for a long time and they thus cannot have been able to establish strong ties to their place of living yet. However, most of these moves where inner-regional moves (from cities proper to the vicinities), and although this type of migration does not suggest strong ties to the place of residence, it does indicate that there are strong ties to the region. In light of this finding, it seems plausible that recently migrated households have chosen new homes with better living conditions in their favorite place of residence and hence express no intentions of moving at a later date.

By comparison, the lowest values are observed in West German cities, the lowest rates of persistence being in Munich. Although being a very attractive city that offers a high quality of life, Munich, as Bavaria’s capital, is also affected by affordability issues. Especially, the costs of housing have increased sharply in recent years. On the one hand, that gives many respondents reason to fear that they may no longer be able to afford their current home in the light of shrinking retirement benefits (Kramer and Pfaffenbach 2009). In the qualitative interviews, they expressed the following: “Actually, I’m not really interested in moving. But as far as my job situation is concerned, I am not doing too well. It is indeed conceivable that my apartment might become too expensive and that life in Munich in general might become too expensive. Munich is one of the most expensive cities, maybe even the most expensive city, not just in terms of housing. I don’t want to move to Augsburg, but it may well turn out that I might move to the Canary Islands, for instance” (55-year-old freelancer, in Munich-Schwabing). Since moving in Munich would typically require respondents to pay significantly higher prices per square meter than they are paying for their current residence (71 % are tenants), higher rents on the other hand can lead to situations in which moving is not an option since less expensive alternatives are not available and they end up staying out due to financial constraints.

As the qualitative interviews reveal, downtown residents rarely consider moving to the outskirts of town or the surrounding suburban communities. The residents of outskirt districts and suburban communities wish to remain in their current residence as well since they either own a home or live in a quiet and a scenic environment that perfectly suits their preferences and in which they have strong social and family networks. Most respondents stated that they would like to stay in the same city as well as in the respective city district and, preferably, in their current residence.

4.2 Reasons for residential persistence upon retirement in Germany

-

(a)

Reasons for staying in the current location

Both in the quantitative survey and the qualitative interviews, the respondents’ assessment of their current place of residence played a significant role in their plans for the future. The central theme that occurred in all of the qualitative interviews was that most interviewees viewed their respective community as the ideal residential location and the current neighborhood clearly having more advantages than disadvantages (Kramer and Pfaffenbach 2007).

In response to the open-ended questions in the questionnaire about the most important reasons for retaining the current living arrangements and the housing situation, the respondents gave reasons referring to the urban district or suburban community as well as their specific residence (see Table 3). Reasons relating to the district/community were a quiet neighborhood, sufficient shopping facilities for everyday needs, proximity to downtown, and a scenic environment. Home ownership, inexpensive housing, and accommodations adapted to the needs of the elderly were aspects most frequently mentioned in regard to the current residence. In many cases, either the respondents themselves or the owners of the rental property had just recently invested in improvements tailored to the needs of elderly residents. The motivation to retain current living and housing arrangements is, however, also owed to the location of the residence ensuring proximity to established social networks—whether family or good relationships with neighbors.

These preferences are exemplified by an answer given during a qualitative interview (a 59-year-old female draftsperson, Munich-Schwabing): “But I would never want to move away from here because the quality of living is just great here, it’s not on a main road, (…) the bedroom is in the back, it’s so quiet. (…) Giving up living in Munich—no, my husband would have to leave without me.” The respondent touches upon the non-willingness to move to their second home in a rural area in Bavaria. She values the urban infrastructure and the prevailing social network in her current living area, which makes it more appealing to her to stay where she is despite the more beautiful natural landscape in rural areas. In this case, there is no ideal amenity migration apparent, which in turn means that a multi-locality is maintained.

A strong relationship emerges between the number of previous moves and the potential willingness to move: The more often respondents have moved in the past, the more easily they can imagine moving upon retirement. That particularly applies to those participants who moved for occupational reasons. This cohort expresses plans to move upon retirement more frequently (Kappler 2013, p. 314, using the same data).

-

(b)

Reasons for staying in the current residence

In the qualitative interviews, the participants frequently argued for staying in their current residence by presenting reasons against moving. The interviewees mentioned reasons of personal nature such as the continuous loss of flexibility and a lack of interest in moving as arguments against moving. Another frequently mentioned reason in favor of staying in the current residence is its ideal size. A 60-year-old nurse in Leipzig-Grünau stated as follows: “If it’s up to me, I don’t really want to move. I’m 60 now. Of course, I may have to move to a retirement home one day, but otherwise I don’t really have any reason to move. And I must say, for me the apartment is just the right size.” This statement highlights that the young–old and the recently retired rarely express intentions of moving. As mentioned, however, the necessity of moving at an older age is acknowledged. A residence that has become quite spacious after the children have left home is often perceived as an advantage rather than a disadvantage: “When our children come to visit, we have plenty of room to accommodate them” (59-year-old former clerk in public administration, female, Berlin-Marzahn). A certain size of residence is obviously considered to be necessary to maintain social networks (Peace et al. 2007). This also confirms findings by Oswald et al. (2010) that larger residences are often seen positively by the young–old but that in very old age they become burdens.

As expected, home ownership and reluctance to change residence show a strong correlation at 0.2, at a level of significance of 0.01. The data collected in the quantitative survey do not allow drawing unambiguous conclusions on whether owning the residence leads to a positive impact (e.g., as a financial retirement security and the possibility to becoming older in a familiar physical and social environment) or negative impact (e.g., as a financial burden or hindering a desired change) on the ties one has to the location of residence. However, the data collected in the qualitative interviews point in the direction of desired rather than forced persistence.

5 Multi-local living arrangements: between staying and moving

Ownership of a vacation residence is frequently seen as an incentive to fully relocate to that location upon retirement, not least because such residences are usually situated in scenic regions. However, the opportunity to make intensive temporary use of such a residence may prevent owners from giving up their current principal residence increasing the propensity to retain the main residence in the long term. The percentage of respondents owning a vacation residence varies considerably between East and West German cities (see Fig. 2), and since owning such a residence is embedded in different habitus’ in the formerly divided parts of Germany, it therefore must be judged differently. In East German states, it is much more common for city dwellers to own a “dacha,” which typically is close to the principal residence (a distance of less than 50 km). It is usually simply furnished and often used on a daily basis. This tradition by contrast is not as typical for West German states; there you are more likely to own a vacation residence, which tends to indicate some level of wealth and is more often located abroad.

More than half of the respondents plan to make much more use of their vacation residence than in the past, which means living in a multi-local living arrangement (see Fig. 3). While only a slight majority currently spends more than several weeks there annually, more than 80 % would like to spend far more time there once they have retired. More than half of the respondents consider spending at least 3 months and 20 % 6 months of the year in their second home. Potentially, such an arrangement will not lead to moving one’s principal residence upon retirement. However, for the great majority of respondents in all cities, the existence of a vacation residence seems to be an incentive for more intensive use and hence for multi-local living arrangements rather than for moving there in all entirety.

Current use and planned use upon retirement of the own vacation residence (only owners of the residence considered). The surveys conducted in Munich, Karlsruhe, and Aachen did not ask about current use, which explains the difference in absolute numbers between the category “current use” and “use in retirement.” Source: own survey

The planned temporary change of residence encountered in the responses strongly corresponds to the phenomena observed by Breuer (2004), Kordel (2013), Janoschka and Duran (2014) for Spain and Åkerlund (2013) for Malta. We can thus argue that a proportion of the respondents have a high socioeconomic status, are “amenity-oriented” (Breuer 2004, p. 127), seasonal migrant retirees, the classic “snow birds,” who lead a multi-local life at two or more locations. The East German respondents enjoy their second residence even more frequently: It is a place they can frequent on a daily or weekly basis, while the close proximity allows them to maintain their local social relationships in everyday life.

Persistence and multi-local living arrangements are much more likely than moving permanently. We can therefore expect to increasingly witness what might be described as a “mobility continuum” (Hall and Müller 2004), which cannot be adequately grasped in terms of the distinction between migration and touristic visits. It thus seems fair to assume that retirement migration abroad will hardly have any noteworthy impact on the spatial structures of Germany’s urban regions since most senior citizens can be expected to retain their principal residence. The current home will then be available once the young–old have become old–old and wish to benefit from Germany’s health and care infrastructure. It will most likely rather be in locations of the second homes that the retreat of German senior citizens will be seriously felt and it may lead to conflicts between second home owners and local residents (“kalte Betten” in Switzerland or “volets clos” in France; Rolshoven and Winkler 2009, p. 101).

6 Conclusion: “aging in place” as a megatrend

The extraordinarily high satisfaction and identification with the current place of residence and surrounding neighborhood reflected in our study along with the partly high rates of home ownership give reason to expect continuously high residence persistence among future senior citizens. “Aging in place” therefore proves to be the main preference by far among the generation 50+ in Germany. The reasons that the respondents gave for staying where they live now range from high satisfaction with their place of residence in general, to the bonding force of home ownership, to financial aspects, and finally to existing social networks.

“Should I go?”, meaning to fully relocate upon retirement, was answered in the affirmative by only 7 % of the respondents. A much larger share of respondents sympathized with the idea of spending parts of the year at another location, for instance, at a vacation residence and thus be living in multi-local arrangements. If moving residence is considered at all, the respondents mostly had moves within the region in mind or, in the case of some city dwellers, a relocation abroad. Our findings give no indication that a trend toward reurbanization is taking place. Instead of a reurbanization trend, our results point more in the direction of sub- or counter urbanization. This is consistent with Sander et al.’s (2010, p. 16) findings, who predict a trend in retirement migration down the urban hierarchy to “high-amenity non-metropolitan regions.” International literature discusses “return migration” to rural regions, i.e., retirees returning to their places of birth and/or origin (Lundholm 2010), where ties have frequently been maintained through second or vacation residences.

In spite of claiming an increase in mobility among the young–old (Eichener 2001; Heinze et al. 1997), the large majority of respondents among the generation 50+ in our survey planned on staying in their current residence upon retirement. The reasons are manifold but indicate blueprints of action that are framed by structures as well as individual resources and dispositions. A more in-depth comparative international analysis of persistence could be a highly interesting future research endeavor.

Notes

One reason for choosing these cohorts lies in the fact that the initial empirical study was launched in 2005 in Munich and included respondents who were 51–60 years old at the time (birth cohorts 1945–1954). In the course of the study, we continued to focus on the same age cohorts to maintain comparability. This resulted in shifting the years of birth (of the cohorts considered) up to three years in the later stages of our research. By selecting this age group, which had not yet retired at the time of the survey, and focusing on their plans for the time immediately after retirement, we have been able to link the observations made to the specific age group in question more precisely than is usually possible in studies on migration and housing preferences of the retirees (see Sander et al. 2010, p. 10f).

Consideration of values and lifestyles in the analysis led to results similar to Jansen (2012), which state that there are no clear relationships apparent between intentions to migrate and values.

Most analyses distinguish between West and East Berlin because of the differences in the housing markets owed to the different housing policies of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic.

See the indicators and maps on urban and spatial development (INKAR, ed. by Bundesinstitut für Stadt-, Bau- und Raumforschung, 2012).

A large number of studies are discussed in detail in Kramer and Pfaffenbach (2011).

See the discussion in an earlier article (Kramer and Pfaffenbach 2009).

It must be noted, however, that after district reorganization in Berlin, it is no longer possible to clearly associate data on purchasing power and other economic parameters at the district level with the former East and West Berlin Districts.

When we speak of home ownership, we refer to any form of ownership of one’s residence, whether single family homes or condominiums, unless otherwise stated.

Home ownership rates in Germany are fairly low (49 %) in comparison with the rest of Europe. The mean average for countries in the EU25 was about 70 % and reached 89 % in Spain and even 95 % in Poland (GESIS – Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften in Mannheim 2014).

References

Adam, B., & Sturm, G. (2012). Deutsche Großstädte mit Bevölkerungsgewinnen—eine Übersicht. In Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR; Ed.), Die Attraktivität großer Städte: ökonomisch, demografisch, kulturell (pp. 5–12). Bonn.

Åkerlund, U. (2013). Buying a place abroad: Processes of recreational property acquisition. Housing Studies, 28(4), 632–652.

Amrhein, L. (2004). Die Bedeutung von Situations- und Handlungsmodellen für das Leben im Alter. In S. Blüher & M. Stosberg (Eds.), Alter(n) und Gesellschaft: Neue Vergesellschaftungsformen des Alter(n)s (pp. 53–86). Wiesbaden.

Beck, U. (1986). Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Frankfurt on the Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Bradley, D. E., Longino, J. C. F., Stoller, E. P., & Haas, H. W. (2008). Actuation of mobility intentions among the young-old: An event-history analysis. The Gerontologist, 38(2), 190–222.

Breuer, T. (2004). Successful Aging auf den Kanarischen Inseln? Versuch einer Typologie von Alterns-Strategien deutscher Altersmigranten. Europa Regional, 12(3), 122–131.

Breuer, T. (2005). Retirement migration or rather second-home tourism? German senior citizens on the Canary Islands. Die Erde, 136(3), 313–333.

Brühl, H., Echter, C. P., Frölich von Bodelschwingh, F., & Jekel, G. (2005). Wohnen in der Innenstadt. Eine Renaissance? Berlin.

Bucher, H., & Heins, F. (2001). Altersselektivität der Wanderungen. In Institut für Länderkunde Leipzig (Ed.), Nationalatlas Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Bevölkerung (pp. 120–123). Berlin/Heidelberg.

Bucher, H., & Schlömer, C. (2012). Eine demografische Einordnung der Re-Urbanisierung. In Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR; Ed.), Die Attraktivität großer Städte: ökonomisch, demografisch, kulturell (pp. 66–72). Bonn.

Buck, C. (2005). Zweit- und Alterswohnsitze von Deutschen an der Costa Blanca. Räumliche Identifikation und soziale Netzwerke im höheren Erwachsenenalter am Beispiel der Gemeinde Els Poblets. Dissertation, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) (Ed.) (2012). Indikatoren und Karten zur Raumentwicklung (INKAR). Bonn.

Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen (DZA; Ed.) (1996). Der Alterssurvey. Berlin.

Eichener, V. (2001). Mobil bleiben! Über das Umziehen im Alter. In Schader-Stiftung (Ed.), wohn: wandel. Szenarien, Prognosen, Optionen zur Zukunft des Wohnens (pp. 174–185). Darmstadt.

Fina, S., Planinsek, S., & Zakrezewski, P. (2009). Suburban crisis? Demand for single family homes in the face of demographic change. Europa Regional, 17(1), 2–14.

Flöthmann, E. J. (1997). Der biographische Ansatz in der Binnenwanderungsforschung. IMIS-Beiträge, 5, 25–45.

Friedrich, K. (2002). Migrationen im Alter. In B. Schlag & K. Megel (Eds.), Mobilität und gesellschaftliche Partizipation im Alter (pp. 87–96). Stuttgart.

Friedrich, K. (2009). Wohnen im Alter. Fluidität und Konstanz der Anspruchsmuster in raumzeitlicher Perspektive. In B. Blättel-Mink & C. Kramer (Eds.), Doing aging—Weibliche Perspektiven des Älterwerdens (pp. 45–54). Baden-Baden.

Friedrich, K., & Kaiser, C. (2001). Rentnersiedlungen auf Mallorca? Europa Regional, 9(4), 204–211.

Friedrich, K., & Warnes, A. M. (2000). Understanding contrasts in later life migration patterns: Germany, Britain and the United States. Erdkunde, 54, 108–120.

Gans, P., Schmitz-Veltin, A., & West, C. (2010). Wohnstandortentscheidungen von Haushalten am Beispiel Mannheim. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 68(1), 49–59.

GESIS–Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften in Mannheim. (2014): Social indicators monitoring (SIMon). Retrieved February 26, 2014, from http://gesis-simon.de/simon_eusi/index.php.

Glasze, G., & Graze, P. (2007). Raus aus Suburbia—rein in die Stadt? Studie zur zukünftigen Wohnmobilität von Suburbaniten der Generation 50+. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 65(5), 467–473.

Glatter, J., & Siedhoff, M. (2008). Reurbanisation: Inflationary use of an insufficiently defined term? Comments of the definition of a key concept of urban geography, with selected findings for the city of Dresden. Die Erde, 139(4), 289–308.

Haase, A. (2008). Reurbanisation—An analysis of the interaction between urban and demographic change: A comparison between European cities. Die Erde, 139(4), 309–332.

Hall, C., & Müller, D. (2004). Tourism, mobility and second home: Between elite landscape and common ground. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Hansen, E. B., & Gottschalk, G. (2006). What makes older people consider moving house and what makes them move? Housing, Theory and Society, 23(1), 34–54.

Heinze, R. G., Eichener, V., Naegele, G., Bucksteg, M., & Schauerte, M. (1997). Neue Wohnung auch im Alter. Folgerungen aus dem demographischen Wandel für Wohnungspolitik und Wohnungswirtschaft. Retrieved May 19, 2015, from http://archiv.schader-stiftung.de/docs/neue_wohnung_kurzfassung_ok.pdf.

Herfert, G. (2002). Disurbanisierung und Reurbanisierung. Polarisierte Raumentwicklung in der ostdeutschen Schrumpfungslandschaft. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 60(5), 334–344.

Hesse, M. (2008). Reurbanisierung? Urbane Diskurse, Deutungskonkurrenzen, konzeptionelle Konfusion. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 66(5), 415–428.

Hesse, M. (2012). Neue Attraktivität und wenn ja, wie viele? In Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR; Ed.), Die Attraktivität großer Städte: ökonomisch, demografisch, kulturell (pp. 89–96). Bonn.

Hirschle, M., & Schürt, A. (2008). Suburbanisierung … und kein Ende in Sicht? Intraregionale Wanderungen und Wohnungsmärkte. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 3, 211–227.

Inglehart, R. (1998). Modernisierung und Postmodernisierung. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Janoschka, M., & Durán, R. (2014). Lifestyle migrants in Spain. Contested realities of political participation. In M. Janoschka & H. Haas (Eds), Contested spatialities, lifestyle migration and residential tourism (pp. 60–73). Abington: Routledge.

Jansen, S. J. T. (2012). What is the worth of values in guiding residential preferences and choice? Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27, 273–300.

Kaiser, C. (2011). Transnationale Altersmigration in Europa. Sozialgeographische und gerontologische Perspektiven. Wiesbaden: Verlag Sozialwissenschaften.

Kappler, M. F. (2013). Ruhestandsmigration der deutschen Nachkriegskohorte. Umzugsneigungen und Umzugspläne im Übergang zum Ruhestand aus individueller Perspektive. Dissertation, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Kordel, S. (2013). Lifestyle-Mobilitäten deutscher Senioren in Spanien—das Beispiel der Gemeinde Torrox an der Costa del Sol. Mitteilungen der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 58, 53–66.

Kramer, C., & Pfaffenbach, C. (2007). Alt werden und jung bleiben—Die Region München als Lebensmittelpunkt zukünftiger Senioren? Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 65(5), 393–406.

Kramer, C., & Pfaffenbach, C. (2009). Persistence preferred—On future residential (im) mobility among the generation 50plus. Erdkunde, 63(2), 161–172.

Kramer, C., & Pfaffenbach, C. (2011). Junge Alte als neue “Urbaniten”? Mobilitätstrends der Generation 50plus. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 69(2), 79–90.

Kuhn, G. (2007). Reurbanisierung, Renaissance der Städte und Stadtwohnen. Informationen zur modernen Stadtgeschichte, 2, 121–130.

Laux, H. (2012). Demographic change in Germany. Processes, causes, challenges. Geographische Rundschau, Special Edition, 33–39.

Lundholm, E. (2010). Returning home? Migration to birth place among migrants after age 55. Population, Space and Place, 18(1), 74–84.

Michael Bauer Research GmbH (MB-Research) (Ed.) (2015). Kaufkraft 2014 in Deutschland. Retrieved May 29, 2015, from http://www.mb-research.de/_download/MBR-Kaufkraft-2014-Kreise.pdf.

Oswald, F., Hieber, A., Mollenkopf, H., & Wahl, H. W. (2003). Wohnwünsche und Wohnwirklichkeiten: Abschlussbericht. Heidelberg.

Oswald, F., Jopp, D., Rott, Ch., & Wahl, H.-W. (2010). Is aging in place a resource for or risk to life satisfaction? The Gerontologist, 51(2), 238–250.

Oswald, F., Wahl, H.-W., Schilling, O., Nygren, C., Fänge, A., Sixsmith, A., et al. (2007). Relationship between housing and healthy aging in very old age. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 96–107.

Peace, S., Wahl, H.-W., Mollenkopf, H., & Oswald, F. (2007). Environment and ageing. In J. Bond, S. Peace, F. Dittmann-Kohli & G. Westerhof (Eds.), Ageing in society (pp. 209–234). London.

Pettersson, A., & Malmberg, G. (2009). Adult children and elderly parents as mobility attractions in Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 15(4), 343–357.

Rauterberg, H. (2005). Neue Heimat Stadt. Die Zeit August 18, 33.

Rogers, A., & Watkins, J. (1987). General versus elderly interstate migration and population redistribution in the United States. Research on Aging, 9(4), 483–529.

Rolshoven, J., & Winkler, J. (2009). Multilokalität und Mobilität. Zeitschrift zur Raumentwicklung, 1(2), 99–106.

Sander, N., Skirbekk, V., Samier, K. C., & Lundevaller, E. (2010). Prospects for later life migration in urban Europe. Peri-urban land use relationships (PLUREL). Retrieved February 26, 2014, from http://www.plurel.net/images/D124.pdf.

Schäfers, B. (1995). Die Grundlagen des Handelns: Sinn, Normen, Werte. In H. Korte (Ed.), Einführung in die Hauptbegriffe der Soziologie (pp. 17–34). Opladen.

Schneider-Sliwa, R. (2004). Städtische Umwelt im Alter. Geographica Helvetica, 59(4), 300–312.

Sturm, G., & Meyer, K. (2008). “Hin und her” oder “hin und weg”—zur Ausdifferenzierung großstädtischer Wohnsuburbanisierung. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 3, 229–243.

Wagner, M. (1989). Räumliche Mobilität im Lebensverlauf. Stuttgart: Thieme.

Wahl, H. W. (2001). Das Lebensumfeld als Ressource des Alters. In S. Pohlmann (Ed.), Das Altern der Gesellschaft als globale Herausforderung (pp. 172–211). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Weichhart, P., Weiske, C., & Werlen, B. (2006). Place Idenity und Images. Das Beispiel Eisenhüttenstadt. Vienna.

Wiles, J. L., Allen, R. E. S., Palmer, A. J., Hayman, K. J., Keeling, S., & Kerse, N. (2009). Older people and their social spaces: A study of well-being and attachment to place in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Science and Medicine, 68(4), 664–671.

Williams, A., King, R., & Warnes, A. (1997). A place in the sun: International retirement migration from northern to southern Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 4(2), 115–134.

Wiseman, R. F. (1980). Why older people move: Theoretical issues. Research on Aging, 2(2), 141–154.

Wörmer, S. (2010). Die Wiederentdeckung des städtischen Wohnens. Untersuchungen der Wanderungen in die Stadt Aachen im Kontext von Reurbanisierungsprozessen. Munich.

Zaugg, V., van Wezemael, J. E., & Odermatt, A. (2004). Wohnraumversorgung für alte Menschen: ein Markt? Geographica Helvetica, 59(4), 313–321.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the German Research Foundation (DFG) for project funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kramer, C., Pfaffenbach, C. Should I stay or should I go? Housing preferences upon retirement in Germany. J Hous and the Built Environ 31, 239–256 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9454-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9454-5