Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the levels of human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and vaccination awareness among members of the general population across three Nigerian States. A descriptive cross-sectional study among 758 persons selected by convenience sampling was conducted from March to July 2016. Structured questionnaires were administered to consenting participants and analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods in SPSS V20. Awareness to HPV infection and vaccination was very low at 1.40 ± 1.803 out of 6 points. Only 31.97% of respondents had heard about HPV while 17.5% were aware of the existence of a vaccine. The most prevalent sources of information amongst respondents who had heard about HPV were Doctors (13.08%) and the Media (9.91%). Bivariate analysis showed that respondents who consulted with gynaecologists, knew someone who had cervical cancer or had received HPV vaccination were more likely to be aware of HPV infection and vaccination. Gynaecologists (p < 0.0001) and previous vaccination (p < 0.0001) were the most important contributors to HPV awareness in a multivariate analysis. This study underpins the need for urgent intervention to raise awareness for HPV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The human papilloma virus (HPV) types 16 and 18 are responsible for at least 70% of all cervical cancer cases in women [10]. An estimated 530,000 women are affected by cervical cancer each year globally with over 80% of this burden resident in developing countries where there is often limited access to healthcare [22]. In Nigeria, the prevalence of HPV is estimated to be 3.5% with over 14, 000 cases and 8000 deaths annually [9]. Furthermore an estimated 53 million women aged ≥ 15 are currently at risk of contracting cervical cancer [9]. While a vaccine against HPV exists in Nigeria, there is very little adoption since the country is yet to fully include HPV vaccination into its routine immunisation program [9]. Stakeholders nonetheless have committed to scaling up access to HPV screening and vaccination in a bid to reduce the cervical cancer burden in the country. Efforts may however be ineffective if proper health awareness and promotion activities are not carried out. This study assessed the levels of HPV infection and vaccination among members of the general population across three Nigerian states.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional study from March to July 2016 across three major states in Nigeria; Lagos, Ogun and Abia States. The study population included University students and staff as well as persons from the general public who didn’t belong to a university. Participants from Ogun State were either staff or students affiliated with the following higher institutions; Covenant University, Bells University of Technology, Crawford University and Gateway Polytechnic (G. poly). Other participants from Lagos and Abia states were members of the general population who, at the time were not affiliated with a higher institution. Sampling was done via convenience sampling method. Participants were approached and the study design was explained to them. Persons who gave oral consent and completed the questionnaire were included in the study. Returned questionnaires were assessed for completeness and those with missing demographic information were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire

We developed a 24-item questionnaire after adequate review of literature. The questionnaire contained two main sections. The first section collected demographic information of participants such as age-group and marital status while the second section contained questions designed to assess the level of awareness of HPV infection and vaccine. A subset of six questions were used to generate an awareness score. One point was given for each correct response and zero for incorrect or no responses. The threshold for awareness in this study was set at 3.

Participants scoring 3 or more on the awareness assessment were further classified as having good awareness while those with scores < 3 were categorized as having poor awareness.

Data Analysis

Our study participants came from six different locations and were group into two main groups based on whether or not they were, at the time of recruitment, affiliated with an institution of higher learning. Participants from Covenant University, Bells University of Technology, Crawford University and Gateway Polytechnic were classified as ‘School’ and others from Lagos or Abia classified as ‘Non-School’.

Descriptive statistics was used to describe distributions. Proportions were compared using the Chi-squared test. Level of awareness, our dependent variable, was checked for normality using Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests alongside a histogram. Relationships between dependent and independent variables were assessed with either Mann–Whitney test for independent variables with two categories or Kruskal–Wallis test for independent variables with more than two categories.

All analysis was performed using IBM SPSS V20 for Windows and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

Description of Study Population

A total of 805 responses were collected and 757 were included based on completeness. 76.5% of the respondents were affiliated with a school with the largest proportion recruited from G. Poly (30.6%). Of the group not affiliated with a school 11.8 and 11.8% were recruited from Lagos and Abia respectively. In addition most participants were with the age group of 16–39 (88.6%), single (82.2%) and possessed post-secondary education (92.3%) (Table 1).

HPV Infection and Vaccination Awareness

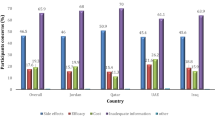

Six questions were used to assess awareness of HPV infection and vaccination. Table 2 contains the distribution of correct responses for questions measuring awareness stratified by class of respondent. The number of correct responses across all participants was poor with an average of 1.40 ± 1.803 (95% CI 1.27–1.53). Only 24.31% of respondents had three or more correct responses with most (48.35%) respondents having no correct responses (Fig. 1). The highest proportion of correct responses (31.97%) was for the question regarding previous hearing of HPV infection while the lowest (9.91%) was for the question regarding the name of the currently used vaccine for HPV prevention. Non-school respondents (41.01%) were more likely to have heard about HPV infection than respondents from a university (29.13%) (p = 0.003). Only 26.02% of respondents were aware that HPV infection could cause cervical cancer with non-school respondents more likely (p = 0.037) to have answered correctly. 31.31% of respondents were aware of the guidelines for cervical cancer screening while only 22.99% were aware that HPV was sexually transmitted. Although 17.57% of respondents were aware of a vaccine against HPV, only 9.91% correctly named the vaccine. The difference in responses relating to the HPV vaccine was not significant across participants from a school and otherwise.

Table 3 shows the distribution of the different sources of information and its effect on HPV awareness. Generally, respondents who had previously heard about HPV or guidelines for cervical cancer screening from at least one source were more likely to have more correct responses than respondents who hadn’t previously heard about HPV or cervical cancer screening guidelines. Doctors and Medical professionals were the most prevalent source of information for both HPV and cancer screening guidelines. Respondents whose source of information for HPV and cervical cancer screening guidelines was a doctor/medical professional had an average of 3.86 ± 1.66 and 3.34 ± 1.82 correct responses. Respondents who had no previous knowledge of HPV or cervical cancer screening guidelines had the lowest number of correct responses.

Post-Hoc Krukal–Wallis comparisons showed that respondents with previous knowledge from any source had significantly more correct responses than those who had no previous knowledge (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, respondents for whom their source of information about cervical cancer screening guidelines was a doctor/medical professional had significantly more correct responses than persons who were informed by friends and family (p = 0.015).

Table 4 shows independent predictors of awareness of HPV infection and vaccination. Respondents who were married were more likely to have answered more questions correctly compared to respondents who were single. Persons who consulted with gynaecologist had significantly more correct responses (p < 0.0001) than persons who consulted with other types of medical practitioners. The highest proportion of correct responses came from respondents who had previously been vaccinated or had a spouse who was vaccinated (3.37 ± 1.81) while the lowest was from persons who reportedly did not consult with any type of medical practitioner. Persons who knew someone with cervical cancer had an average of 3.06 correct responses as compared to an average of 1.42 amongst respondents who didn’t know anyone who had cervical cancer.

Only 5.27% of respondents stated that they had previously received vaccination for HPV while 69.71% were willing to be vaccinated. Cross tabulation of awareness and willingness to be vaccinated revealed that 82.2% of persons with good awareness were willing to be vaccinated as opposed to 65.1% of respondents with poor awareness. The difference among both groups was also statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Multivariate Analysis

All variables passed the test for multicollinearity at VIF threshold of 5. The independent predictors explained 24.5% of the variation in correct responses of study participants. Multivariate analysis of independent predictors showed that consulting with a gynaecologist and having previous vaccination were the most important predictors of awareness in this study (Table 5).

Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between awareness or knowledge of HPV and vaccine uptake or a willingness to get vaccinated [2,3,4, 6, 15, 17,18,19]. However, most of these studies focus on women, adolescent girls and healthcare professionals or students. There are fewer studies examining the awareness and perceptions among the general population. This study contributes knowledge to existing studies among the general population. Awareness to HPV was very low in this study with only a quarter of respondents having good awareness based on our set threshold. This is similar to previous studies where low knowledge was reported among different populations with differing levels of education across Nigeria [1, 3, 11, 12]. This similitude in findings was unexpected since most of the respondents in our study possessed post-secondary education. Further analysis, however, showed no relationship between awareness of HPV and education in our study. This lack of association between education and HPV awareness seems to be the case in the sub-Saharan region but not in developed nations where some studies have shown associations between increased education and HPV awareness [8, 13, 14, 20].

Previous studies from developed nations have shown the association of higher HPV knowledge with non-traditional sources of information such as the internet [5, 21]. This is somewhat contrasting with findings from our study where medical personnel and the media were the major sources associated with good awareness of HPV infection and vaccination. While the internet was also a source of information in our study, it wasn’t a major influencer of awareness. This could be as a result of the low internet penetration predominant in the sub-Saharan African region. Furthermore, university students, the predominant demographic in our study are known to rely on non-traditional sources of information such as social media, it is important for stakeholders in the health sector to begin to explore such platforms for the adequate dissemination of health information. On the other hand, the fact that non-traditional media platforms are unregulated could result in poor awareness and an unwillingness to receive vaccination which may stem from the myriad of wrong and/or critical information about HPV vaccine [7, 16].

Vaccine uptake among our study participants was very poor (5.27%) with most respondents stating that they didn’t need the vaccine or were unaware of the existence of a vaccine. This low uptake is probably due to the fact that Nigeria is yet to incorporate HPV vaccination into its immunisation schedule. Furthermore, a recent report on the situation of HPV infection and cervical cancer in Nigeria stated that 15% of Nigerian adolescent girls were already sexually active by age 15 while most become active by age 18 [9]. This is indicative of an urgent need to intensify efforts to make vaccines against HPV available in a bid to reverse the increasing cervical cancer burden since majority of our study respondents may soon exit the recommended age bracket for receiving a vaccine.

We found that respondents who consulted with a gynaecologist were more likely to be aware of HPV infection and vaccination. The reason for this is not clear from our data however we hypothesize that such respondents may have visited the hospital for screening of the cervix hence the higher level of awareness. We also found persons who knew someone who had cervical cancer were more aware than others, this is consistent with an earlier report among Latina immigrants [9].

Limitations of Study

Our study has a few limitations, we didn’t consider the effect of gender on HPV awareness among our study population. We expect that there would be significant differences between sexes since the female gender is more likely to perceive HPV infection as dangerous. We also didn’t assess the perceptions of respondents towards vaccines which has been shown to be a major influence on vaccine uptake.

Conclusion

Our findings underpin the need for urgent intervention by health stakeholders in a bid to raise HPV infection and HPV vaccine awareness among adolescent boys and girls. We recommend that such interventions take advantage of non-traditional media platforms to properly disseminate information.

Data Availability

The Data used in this study is available on request.

References

Abiodun, O., Sotunsa, J., Ani, F., & Olu-Abiodun, O. (2015). Knowledge and acceptability of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine among university students in South West, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3(10), 101–112.

Adejuyigbe, F. F., Balogun, B. R., Sekoni, A. O., & Adegbola, A. A. (2015). Cervical cancer and human papilloma virus knowledge and acceptance of vaccination among medical students in Southwest Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 19(1), 140–140.

Agida, T. E., Akaba, G. O., Isah, A. Y., & Ekele, B. (2015). Knowledge and perception of human papilloma virus vaccine among the antenatal women in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Nigerian Medical Journal, 56(1), 23–27.

Akanbi, O. A., Iyanda, A., Osundare, F., & Opaleye, O. O. (2015). Perceptions of Nigerian Women about human papilloma virus, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccine. Scientifica. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/285702

Almeida, C. M., Tiro, J. A., Rodriguez, M. A., & Diamant, A. L. (2012). Evaluating associations between sources of information, knowledge of the human papilloma virus, and human papilloma virus vaccine uptake for adult women in California. Vaccine, 30(19), 3003–3008.

Audu, B. M., Bukar, M., Ibrahim, A. I., & Swende, T. Z. (2014). Awareness and perception of human papilloma virus vaccine among healthcare professionals in Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 34(8), 714–717.

Betsch, C., Renkewitz, F., Betsch, T., & Ulshöfer, C. (2010). The Influence of vaccine-critical websites on perceiving vaccination risks. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(3), 446–455.

Blodt, S., Holmberg, C., Muller-Nordhorn, J., & Rieckmann, N. (2012). Human papilloma virus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: A survey among 18–25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. The European Journal of Public Health, 22(6), 808–813.

Bruni, L., Barrionuevo-Rosas, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Gómez, D., et al. (2017). Human papilloma virus and related diseases in Nigeria. 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2018, from, http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA.

Cutts, F. T., Franceschi, S., Goldie, S., Castellsague, X., de Sanjose, S., Garnett, G., et al. (2007). Human papilloma virus and HPV vaccines: A review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(9), 719–726.

Durowade, K., Osagbemi, G., Salaudeen, A., Musa, O., Bolarinwa, O., Babatunde, O., et al. (2013). Knowledge of cervical cancer and its socio-demographic determinants among women in an urban community of North-central Nigeria. Savannah Journal of Medical Research and Practice, 2(2), 46–54.

Ezenwa, B. N., Balogun, M. R., & Okafor, I. P. (2013). Mothers’ human papilloma virus knowledge and willingness to vaccinate their adolescent daughters in Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal of Women’s Health, 5(1), 371–377.

Klug, S. J., Hukelmann, M., & Blettner, M. (2008). Knowledge about infection with human papilloma virus: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 46(2), 87–98.

McBride, K. R., & Singh, S. (2018). Predictors of adults’ knowledge and awareness of HPV, HPV-associated cancers, and the HPV vaccine: Implications for health education. Health Education & Behavior, 45(1), 68–76.

Morhason-Bello, I. O., Adesina, O. A., Adedokun, B. O., Awolude, O., Okolo, C. A., Aimakhu, C. O., et al. (2013). Knowledge of the human papilloma virus vaccines, and opinions of gynaecologists on its implementation in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive health, 17(2), 150–156.

Nan, X., & Madden, K. (2012). HPV vaccine information in the blogosphere: How positive and negative blogs influence vaccine-related risk perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Health Communication, 27(8), 829–836.

Nnodu, O., Erinosho, L., Jamda, M., Olaniyi, O., Adelaiye, R., Lawson, L., et al. (2010). Knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer and human papilloma virus: A Nigerian pilot study. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 14(1), 95–108.

Ogochukwu, T. N., Akabueze, J., Ezeome, I. V., Aniebue, U. U., & Oranu, E. O. (2017). Vaccination against human papilloma virus in adolescent girls: Mother’s knowledge, attitude, desire and practice in Nigeria. Journal of Ancient Diseases & Preventive Remedies, 5(1), 1–6.

Perlman, S., Wamai, R. G., Bain, P. A., Welty, T., Welty, E., & Ogembo, J. G. (2014). Knowledge and awareness of HPV vaccine and acceptability to vaccinate in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e90912.

Radecki Breitkopf, C., Finney Rutten, L. J., Findley, V., Jacobson, D. J., Wilson, P. M., Albertie, M., et al. (2016). Awareness and knowledge of human papilloma virus (HPV), HPV-related cancers, and HPV vaccines in an uninsured adult clinic population. Cancer Medicine, 5(11), 3346–3352.

Rosen, B. L., Shew, M. L., Zimet, G. D., Ding, L., Mullins, T. L. K., & Kahn, J. A. (2017). Human papilloma virus vaccine sources of information and adolescents’ knowledge and perceptions. Global Pediatric Health, 4, 1–10.

WHO. (2017). Cervical cancer [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from http://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author AOE conceptualized, designed and monitored the study. She also read and approved the final draft of the manuscript. Authors MGS and AOE prepared the questionnaire used in this study. Author MGS, OPE and TTI administered the questionnaires and entered the data. Author OAO performed the statistical analysis and prepared the first draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee.

Informed Consent

Study design was explained to participants and oral consent obtained before administering questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eni, A.O., Soluade, M.G., Efekemo, O.P. et al. Poor Knowledge of Human Papilloma Virus and Vaccination Among Respondents from Three Nigerian States. J Community Health 43, 1201–1207 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0540-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0540-y