Abstract

In many countries, problem gambling is a significant public health concern. Gambling addiction has been linked to poor health, psychological distress, financial difficulties, and strained interpersonal relationships. In New Zealand, problem gambling is estimated to affect over 10% of the population. To minimize harm, the Gambling Act of 2003 was introduced to limit the number of electronic gaming machines in non-casino establishments. Beyond national-level restrictions, local governments were required to adopt gambling policies of their own and review them every three years. One specific policy that emerged at the local level, found exclusively in New Zealand, is the sinking lid. Sinking lids are designed to gradually reduce machine caps by prohibiting the transfer of gaming licenses. This study leverages variation in the geography and timing of local policy interventions to estimate the effect of sinking lids on gambling expenditure. Results suggest that sinking lids reduce gambling expenditure by 13% relative to regions not adopting policies beyond national-level restrictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Problem gambling in New Zealand

Problem gambling is a significant public health concern in New Zealand (NZ), affecting approximately eleven percent of New Zealanders each year (Department of Internal Affairs, 2008). Problem gambling has been shown to strain professional and interpersonal relationships, cause financial problems, and lead to feelings of shame, guilt, and depression (National Center for Responsible Gaming, 2012). Several studies associate pathological gambling with health and psychiatric problems (Cunningham-Williams et al., 1998; National Research Council, 1999; Petry, 2005). Pathological gambling is also linked to an increased risk of poor physical and mental health (Petry et al., 2005). The American Psychiatric Association (2013) lists jeopardizing or losing a significant relationship, job, or career opportunity as one of the major risks of problem gambling. In order to minimize harm from problem gambling, NZ overhauled its regulatory oversight of gaming in the early 2000s.

The Gambling Act of 2003 (hereafter, the “Act”) made sweeping changes to how NZ regulates non-casino gaming. The Act characterizes problem gambling as any gambling-related activity that creates negative consequences for the individual, their family, or the community. This definition includes those who suffer from pathological gambling, but also individuals whose gambling behavior is not considered severe enough to register as a psychological condition but is severe enough to cause harm. The Act defined electronic, non-casino slot machines as Class 4 gambling (for our purposes, referred to as electronic gaming machines, or EGMs). Several studies have found that Class 4 gambling is the most common form of gambling associated with pathological or problem gambling behavior (Abbott, 2006; Dowling et al., 2005; Storer et al., 2009). EGMs are generally located in enclosed, isolated spaces, are age-restricted, and are typically removed from areas patrons at a bar or club might commonly occupy.Footnote 1 The Act mandated a baseline set of restrictions regarding the number of EGMs per Class 4 venue, which was 18 machines per venue if allocated before October 17, 2001, and nine machines per venue thereafter. Recognizing geographic heterogeneity in gaming intensity and preferences, the legislation also asked territorial authorities (TAs) to adopt policies of their own. TA-level policies produced various responses: some TAs took no action beyond enforcing the Act; others adopted absolute caps based on the number of machines, venues, or both; others instituted per capita caps based on the number of machines, venues, or both; while others adopted “sinking lid” policies, restricting the transfer of Class 4 licenses in order to gradually reduce the availability of gambling outlets.

Although Class 4 gaming is common internationally, policy evaluations in this space are rare. This is likely due to a lack of data and the private nature of Class 4 gaming. The authors could only identify one quasi-experimental study focusing on the causal effect of EGM availability on EGM expenditure. According to a 2005 study by the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies, placing an absolute cap on EGMs in five “vulnerable communities” in Victoria, Australia did not appear to increase or decrease overall EGM expenditure. It is important to note, however, that the study relies on propensity score matching to estimate average treatment effects and is thus susceptible to bias from unobserved community-level characteristics. In terms of relevant NZ literature, there is little evidence regarding the effectiveness of Class 4 gambling policies. In a descriptive analysis of sinking lid policies by the Sapere Research Group in 2018, the authors note that reductions in EGMs are not strongly correlated with reduced expenditure in high deprivation neighborhoods, which may be due to the small magnitude of reductions relative to their existing numbers (Rook et al., 2018). The authors plot changes in EGM density versus the change in EGM expenditure per capita for each TA over fiscal years 2014–2017. Although some TAs showed reductions in both EGM density and gambling expenditure per capita, many did not. In fact, many TAs (especially those with high levels of deprivation) exhibited increased gambling expenditure per capita despite a reduction in EGMs. We argue that the use of micro-level Class 4 gambling expenditure data may be helpful in understanding the efficacy of local policies meant to curb problem gambling. Table 1 presents a summary of the literature, although we caution all studies (with the exception of the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies, 2005) identified are correlational, rather than causal, in nature. Some studies suggest a positive link between EGM availability and EGM expenditure (Australian Institute for Gambling Research, 1995; Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation, 2005). Other studies find no clear impact of EGM availability on gambling expenditure (Bondolfi et al., 2008; McMillen & Doran, 2006; Rook et al., 2018; South Australian Centre for Economic Studies, 2005). Several studies find that decreased availability of EGMs decreases the demand for problem gambling intervention services (Carr et al., 1996; Campbell & Lester, 1999; Bridwell & Quinn, 2002; Williams et al., 2012). Lund (2009) found that decreases in EGM availability did not have any meaningful effect on participation in other forms of gambling.

We use administrative data from the NZ Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) and the NZ Ministry of Health (MOH) to study the effectiveness of local government policy interventions on gambling expenditure. We leverage variation in the type and timing of policy interventions to assess efficacy. We utilize quasi-experimental methods to estimate how local government policy affected problem gambling behavior. We first focus on the direct impact of policy changes by examining the impact on Class 4 gaming availability—the number of EGMs and Class 4 venues in the community. Next, we turn to a measure of spending intensity—the amount of Class 4 gambling expenditures within the year, on a per capita basis. We find that any policy superseding the Act is effective in reducing venues and EGMs, relative to the reference group of TAs following baseline restrictions. Reducing access to Class 4 gambling via sinking lid policies is estimated to decrease gambling expenditure by between 10 and 14% within the first two years of implementation, relative to the baseline. Overall, results suggest that any policy to mitigate Class 4 gambling is better than none—players respond to supply restrictions, and this may mitigate community harm from problem gambling, as measured by Class 4 gambling expenditure. Sinking lid policies appear to be particularly effective in this effort.

Our study makes two contributions to the gambling literature. First, ours is the only study identified to use quasi-experimental panel data methods to estimate the causal impact of EGM availability on Class 4 gambling expenditure. We leverage the timing of policies and their geographic heterogeneity to identify how different local policies affect the availability of, and expenditure on, Class 4 gambling. Panel data methods allow us to control for time-invariant heterogeneity at the TA-level, as well as trends in gambling expenditure over time. Second, rather than appealing to a survey of self-reported gamblers (as in Australian Institute for Gambling Research, 1995 and Bondolfi et al., 2008, for example), we utilize expenditure data from all EGMs within NZ over nine years, which avoids non-reporting bias.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows: Sect. 2 details the legislative background in NZ; Sect. 3 briefly discusses relevant theoretical perspectives regarding problem gambling; Sect. 4 describes our administrative data; Sect. 5 presents the difference-in-differences empirical strategy; Sect. 6 reports main findings; Sect. 7 provides key conclusions and includes a discussion of relevant limitations.

Legislative Background

Problem gambling has been recognized as a significant issue in NZ since the early 2000s, when the Act made sweeping changes to the industry’s regulatory environment and declared gambling to be a public health concern (Adams et al., 2009). The Act had several explicit purposes, including controlling growth in gambling; minimizing community harm; clarifying legal versus prohibited gambling; and ensuring that gambling proceeds benefit the community. The Act also clarified regulatory agency roles. The DIA was made responsible for all forms of gambling law enforcement, while the MOH was tasked with organizing and funding NZ’s approach to addressing problem gambling. As part of their role, the MOH was required to regularly develop strategic plans focused on preventing and minimizing gambling harm in NZ.

Several TAs have put in place additional restrictions on Class 4 gambling, beyond those in the Act. We group these policies into three categories. First, some TAs have enforced absolute caps on the number of EGMs, the number of Class 4 venues, or both, within their jurisdiction. Second, some TAs have implemented per capita caps on the number of EGMs, the number of Class 4 venues, or both. Third, several TAs have adopted sinking lid policies. Sinking lid policies entail a cap on EGMs which is fluid, and only decreases when the transfer of a Class 4 gaming license is prohibited. For example, under a sinking lid policy, Bar X may currently have 20 EGMs under license. If Bar X were to move their location, or shut down altogether, then those 20 licenses are forfeited. Likewise, Bar X cannot sell or transfer their Class 4 EGM licenses to Bar Y by law. And if Bar X were to expand their operations, new Class 4 licenses would not be granted. In effect, sinking lids are a monotonically decreasing step function of EGM licenses over time. See Fig. 1 for a hypothetical illustration of how a sinking lid affects EGM caps over time.

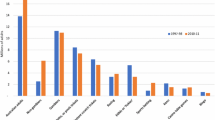

There is substantial geographic variation in Class 4 gambling policies over time. As illustrated by Fig. 2, over the sample period the proportion of TAs in the reference group (i.e., TAs not adopting any restrictions beyond the Act) or adopting a per capita cap decreases, while the proportion of TAs enacting absolute caps and sinking lid policies increases. In general, no TAs set absolute caps below the number of existing EGMs or venues. This supports the idea that some authorities use the sinking lid policy to initially reduce the number of EGMs or venues by a desired amount, before switching to an absolute cap once numbers have reduced. Furthermore, over the sample period, no TAs ever moved into the reference group from a more stringent local policy.

Common Policies that Limit EGM Access

Policies limiting access to EGMs cover a broad range, from the extreme (e.g., total bans) to those that are lower coverage in nature (e.g., age restrictions). Table 2 presents a brief overview of the most common policy categories internationally.

Around the world, several legal strategies have been enacted to limit access to EGMs. These include blanket bans, venue bans, and restrictions related to the legal gambling age and access to alcohol. Although rare, blanket bans have been implemented in several jurisdictions, including NZ where EGMs were banned until their legalization in 1988 (Abbott, 2017). In 2007, in response to rising concern regarding the harm caused by problem gambling, Norway banned all EGMs (Lund, 2009). Before the ban, EGM revenue had risen substantially from NOK 9 billion in 2001 to NOK 27 billion in 2005 where EGMs were available in a wide range of locations, including shopping centers and train stations (Norsk Tipping, 2010). While new EGMs were reintroduced into Norway in 2009, modern machines are under control of the government and have features designed to make them less harmful, such as mandatory play breaks, lower prizes, limits on gambling amount, and the inability to insert cash (Engebø, 2010). Blanket bans were also issued in the U.S. states of Alaska, Hawaii, and Utah (Friedl, 2020), as well as being issued in Hungary and Western Australia (except machines located within casinos) (Szczyrba et al., 2016; Stevens & Livingston, 2019).

Venue bans are a more common policy. For instance, in 2015, Poland banned EGMs in convenience locations, restricting them to casinos and gaming halls (Sulkunen et al., 2018). Similarly, in the Canadian province of British Columbia, EGMs are only permitted in casinos, gaming centers, and co-located racetrack casinos (Gaming Policy & Enforcement Branch, 2019).

A less intensive way of restricting access to EGMs, compared to bans, involves capping EGMs and/or venues in some form. Australia provides a good example. Each Australian state sets some form of cap on EGMs (Livingstone et al., 2019). This is similar to the reference policy in NZ that was created by the Act, whereby each TA faces a cap on number of EGMs per venue. The point of difference is that this base policy is the same across all TAs in NZ, whereas the base cap in Australia is state-specific. Also, in similar fashion to NZ, Australian states can undertake additional, stricter regulation. For instance, in the state of Victoria, in 2000, a per capita cap was introduced (over and above the base cap of 27,500 non-casino EGMs). The cap was specifically targeted at disadvantaged communities and was 11.7 EGMs per 1000 adults (McMillen & Doran, 2006). Municipalities within Victoria that initially failed to meet this threshold were given three years to comply.

Often, venue caps differ according to the type of venue in which EGMS are located. For example, hotels in Australian’s Northern Territory are permitted up to 20 EGMs, while clubs in the same state may have up to 55 (Livingston et al., 2019); most non-casino venues in Alberta, Canada are permitted up to 14 EGMs, while gaming entertainment centers in the same province may have up to 49 (AGLC, 2020); and in the U.S. state of Nevada, up to 7 EGMs are allowed in each convenience store, with a limit of 4 EGMs in liquor stores, while other venue types are assessed on an individual basis (Nevada Gaming Commission & Nevada Gaming Control Board, 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, NZ is the only jurisdiction that uses sinking lid policies to limit problem gambling. As indicated earlier, a sinking lid policy prohibits transferring EGM licenses, so venue closures and relocations result in permanent forfeiture of EGMs within the relevant TA.

Individual-level policies that limit EGM access

Most jurisdictions have a minimum gambling age, usually varying between 18 and 21 years, with limits often depending on the form of gambling (Sulkunen et al., 2018). In many jurisdictions, the minimum gambling age is set with reference to the minimum drinking age, especially since most gambling venues are liquor licensed. In Canada, for example, gambling and alcohol consumption are regulated under the same legislation: the Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act. While access to EGMs and liquor are often co-located, jurisdictions often regulate against intoxicated individuals gambling. In another example from Canada, individuals in Alberta who “appear to be intoxicated” are not allowed to engage with EGMs (AGLC, 2020).

In Europe, the most common gambling age is 18. Across much of the U.S., the gambling age is 21, although it is set at 18 in several states for casino gambling (American Gambling Association, 2020). In NZ, the gambling age is 20 for casinos, and 18 for EGMs outside of casinos.

Theoretical perspectives

A key determinant of gambling behavior is often described via the “availability hypothesis.” This theory argues that problem gambling is positively linked to exposure; as the opportunity to gamble increases, rates of pathological gambling also increase. Early research examining the state-level legalization of several new types of gambling in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s supported this hypothesis (Volberg, 1994).

In addition to the role of availability, NZ research suggests other mechanisms are also at work (Abbott, 2006, 2017). Abbott notes that three new types of gambling were legalized in NZ in the late 1980s: a national lottery, instant lotteries (commonly known as scratch tickets), and EGMs. Data suggest that availability of new venues and forms of gambling was associated with increased participation in gambling initially. However, this increase only continued for up to two years, after which gambling participation declined, coinciding with a decrease in problem gambling. This finding is consistent with the “adaptation hypothesis” which argues that populations adapt over time and that gambling prevalence may plateau or reduce, even with greater availability (Storer et al., 2009).

Another important perspective to note here is “pathological gambling as a disorder of impulse control” (Lesieur & Rosenthal, 1991; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This mental health approach is a useful lens through which to examine gambling behaviour, as well as an aid to diagnosing and treating pathological gambling.

In terms of policy response, NZ has adopted the public health model of gambling, first described by Korn and Shaffer (1999). This model recognizes the importance of the mental health lens, but seeks to offer a more holistic approach, including harm minimization. This policy approach targets the individual (problem gambler), the activity (gambling), the mechanism (EGMs) and the relevant environment (family, community, and society, among others) which contribute or could abate problem gambling and its related harms (Abbott et al., 2017).

This study examines the effectiveness of public health policies intended to reduce problem gambling through a decrease in availability. Given the availability hypothesis, we expect that as restrictions on Class 4 gambling are enacted, including a reduction in venues and/or EGMs (on a per capita basis), this will decrease the prevalence of gambling in affected communities. Importantly, while we can examine evidence of the availability hypothesis, our data do not allow us to directly test for the adaptation hypothesis, as policies at the TA-level are subject to review every three years. We are also not able to examine whether the reduction in Class 4 gambling availability has reduced the prevalence of gambling addiction in the community.

Data

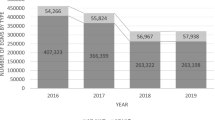

Data are sourced from the DIA, Stats NZ, and each local government body. We first sourced TA-level statistics on the outcome variables of interest—the number of Class 4 venues, the number of EGMs, and gaming machine proceeds (GMP) from the DIA. GMP measures net gaming machine spending by patrons (i.e., total revenue minus wins paid out), or player losses (Department of Internal Affairs, 2020). Data are quarterly and span the period Q2 2010–Q4 2018. We collapse this information to produce annual figures at the TA-level for our outcome variables, specifically the annual mean values for number of Class 4 venues and number of EGMs, and the annual sum of GMP. We adjust the venue and EGM indicators for population by dividing the annual mean values per 100,000 usual resident population within the TA. Annual GMP figures are adjusted for inflation using Q2 2019 NZ dollars as the base. Over our sample period, average annual EGMs and venues per 100,000 population decrease by 28.7% and 26.5% respectively, while player losses (measured in terms of real GMP per capita) decreases by 13.1%. The trend in machine spending is displayed in Fig. 3. The strong seasonal nature of Class 4 gambling in NZ is clear—Class 4 gambling is most popular in last quarter of each year and then abruptly drops in the first quarter of the next year. Figure 4 presents the average number of EGMs, per 100,000 population, over time. As expected, there is little evidence of a seasonal component to the stock of EGMs, and declines are gradual over the sample period.

We next sourced data on the type of Class 4 gambling policies adopted by TAs over time by contacting each of NZ’s 67 TAs under the umbrella of the Official Information Act (OIA). Responses were used to construct a novel panel of TA-level Class 4 gambling policy types over the period 2004 to 2019. This unique dataset also includes information on the specific number of EGMs and venues allowed within the TA over time, on a quarterly basis. We collapsed this information to produce annual policy indicators based on the first quarter of available information for each year. Therefore, gambling policies were sourced from Q1 for the years 2011–2018, and Q2 for the year 2010.

We control for the age, gender, and ethnicity distributions in each TA using data from Stats NZ. Ethnicity by age cohort is not available at the TA-level outside of census years. Therefore, to estimate ethnicity by age cohort for each TA, for each age cohort we first construct the proportion of five ethnic groups– Asian, European, Māori, MELAA (Middle Eastern/Latin American/African) and Pacific Peoples–for each census year 2006, 2013 and 2018. With these rates, we use spline functions to interpolate ethnicity rates in non-census years. We then apply these rates to available population levels available for each TA by year to obtain annual estimates of population by ethnicity, for each age cohort across TAs. We also include annual information on the socioeconomic deprivation level of each TA. The NZ Deprivation index is constructed by the University of Otago, to provide a socio-economic deprivation indicator. It is based on several measures from the Census, such as whether unemployed; whether living in an equivalized household with income below a relevant threshold; not owning home; among others. TAs are categorized into deciles, with the most deprived placed in the top decile (Ward et al., 2019). Deprivation scores are interpolated between census years using spline functions in a similar fashion to demographic indicators.Footnote 2 We also include estimated annual GDP growth rate for each TA, based on TA-level GDP estimates produced by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). This allows us to control for broad economic conditions at the local level, which we suspect are correlated with machine spending.

Our resulting sample is annual in nature, covers all 67 TAs in NZ, and spans the period 2010 to 2018. Table 3 provides definitions for our outcome variables, key policy indicators, and control variables. All descriptive statistics in Table 3 are unweighted TA-year means. Sinking lid policies were in place for approximately one out of three TA-year observations in our data. The share of observations in the reference group was approximately 20%. Average real GMP expenditure per capita over the sample was $186 NZD.

It should be noted that our main outcome of interest, real player losses from Class 4 gambling, is a strong indication of overall problem gambling in New Zealand. According to the literature, the vast majority of Class 4 gambling expenditure is problem gambling expenditure. For example, according to the New Zealand National Gambling Study, the proportion of self-reported problem gamblers that chose Class 4 gambling as their preferred gambling mode increased from 12% 1991 to 78% in 2002 (Abbott & Volberg, 1991; Paton-Simpson et al., 2003).Footnote 3 Further, problem gambling intervention service use data from the MOH show that over the period 2010–2018, 55% of individuals that received problem gambling services chose Class 4 gambling as their primary mode, while 64% listed Class 4 gambling as one of their top five modes of gaming.

Over half of all Class 4 gambling expenditure comes from individuals considered to be high risk or problem gamblers (Abbott et al., 2016). As such, problem gamblers are disproportionately represented by player losses. Additionally, New Zealand survey data has consistently indicated that Class 4 gambling is the mode associated with the most harm (Holland et al., 2017; Rossen, 2015; Thimasarn-Anwar et al., 2017; Tu & Puthipiroj, 2015).

Empirical Model

We evaluate the effectiveness of TA-level interventions using variation in geography and policy timing. We focus on Class 4 gambling, of which there are three distinct policy interventions: absolute venue and/or EGM caps (AC); per capita venue and/or EGM caps (PC); and sinking lid policies (SL). Policy interventions are captured by dummy variables equal to one if the policy was in place in the TA in a particular year, and zero otherwise. The reference group are TAs that did not impose any additional restrictions on Class 4 gambling beyond baseline restrictions set forth in the Act.

The econometric model may be expressed as:

where \(y_{it}\) is an outcome for TA i in year t. Three direct outcomes of interest are examined—the number of Class 4 venues; the number of EGMs; and machine spending.

To capture the impact of varying policy interventions at the TA-level, we use a difference-in-differences approach. X is a vector of demographic controls which includes ethnicity, age, and gender composition. X also includes the deprivation decile over the sample period to help capture socio-economic status at the TA-level, as well as annual GDP growth rates at the TA-level. One-year lags are included to estimate the delayed effect of policies on outcomes. Summing the contemporaneous and lagged impacts of each policy intervention provides an estimate of the cumulative impact in the first two years. TA and year fixed effects remove time-invariant factors which affect gambling behaviour within each TA. An idiosyncratic error term, \({\varepsilon }_{it}\), captures all other factors which are not taken account of in the model.

Because data are naturally clustered into TAs, ignoring this feature will result in standard errors that are misleadingly small and confidence intervals that are too narrow. As a result, estimates would appear more precise than they are. To obtain the correct standard errors we conduct inference using cluster bootstrapping (see Cameron & Miller, 2015, and MacKinnon, 2019 for details).

The identifying assumption in any difference-in-differences approach is that pre-treatment trends are similar across treatment and control groups. This is typically verified by visual inspection, or empirically using methods akin to event study models which check for placebo treatment effects before policy changes occur. In our case, due to having multiple treatment types enacted in different time periods, it is not clear how to visually inspect the parallel trends assumption. Instead, we empirically inspect this assumption by predicting our outcomes while including two leading policy indicators for each treatment type—one and two years prior to the actual policy change-alongside treatment dummy variables in levels and two lagged policy indicators. We refrain from adding additional leads/lags as it would leave us for too few observations for meaningful hypothesis testing. We examine the coefficients on leading indicators for each of our three main outcomes. Any coefficient statistically different from zero on leading indicators suggests that the parallel trends assumption does not hold. Table 4 presents the results of these tests. We find little evidence that there are any significant differences in pre-treatment trends in outcomes. Out of the 18 t-tests we conduct, in only one case do we find a coefficient on a pre-treatment policy indicator that is statistically different from zero. Specifically, we estimate a ten% decrease in player losses in the year prior to implementing a per capita cap. Although this effect is statistically significant, it is not unusual to detect a statistically significant coefficient when testing so many hypotheses (in our case the likelihood of committing at least one Type I error at the 5% significance level is 1 − 0.9518 = 0.603).

Results

Table 5 presents model estimates for our three outcomes of interest. There is evidence of effectiveness across all three forms of policy intervention (absolute cap, per capita cap, and sinking lid) of reducing venues and EGMs relative to the reference group. For example, as shown in column (1) of Table 5, the impact of an absolute cap policy (relative to the reference group) is a drop of 67 EGMs and approximately 7 venues (per 100,000 population) over one year. This equates to a 15% drop in EGMs and a 16.9% drop in venues, per 100,000 population. In terms of magnitude, numbers are marginally larger for the per capita cap policy (85 machines and eight venues respectively), and lower for the sinking lid policy (36 machines and four venues respectively). As shown in Table 5, the direct impact on the number of venues and EGMs are contemporaneous in nature, with no significant impacts in the following year.

The impact on gambling expenditure is of key importance and is shown in column (3) of Table 5. This variable is measured as the natural logarithm of machine spending in real 2019 dollars. Regression coefficients are therefore interpreted as a percentage change. For example, a coefficient of − 0.10 for an absolute cap indicates that compared to the reference group, this policy intervention resulted in a 10% decline in machine spending. When assessing the cumulative impact of policy interventions (sum of both contemporaneous and lagged effects), it appears that per capita caps and sinking lids are the most effective in reducing gambling expenditure. Compared to the reference group, either of these policy interventions has the cumulative impact of reducing machine spending by an estimated 13–14%. We find that absolute caps reduce overall gambling expenditure by 10%. Sinking lid policies appear to be the only policy intervention with evidence of both contemporaneous and lagged negative impacts on machine spending. We tested the sensitivity of our findings by replicating the regression model with weights based on the TA-level population statistics. Our results remain qualitatively similar, thus providing a reassuring signal of robustness of findings.

Lastly, we appeal to decomposition methods proposed by Goodman-Bacon (2018) to better understand what is driving our results. Goodman-Bacon showed that two-way fixed effects difference-in-difference models are a weighted average of results using three different groups as the control: timing groups, or groups that are treated at different times which can serve as other’s control groups in different time periods (e.g., groups treated later in the sample period can serve as controls for groups that are treated earlier on); always treated, the group that was treated before the sample period; and the never treated group. We present these results in Table 6. Decomposition indicates that over 80% of results are driven by TAs that adopted regulations beyond the Act before the sample period began in 2010. Reassuringly, all estimates using the three control groups are negative for each outcome. Notably, Goodman-Bacon decomposition requires a single binary treatment indicator and does not allow for controls. Thus, the decomposition is also an exercise in whether results are similar when assuming homogeneous treatment (i.e., absolute caps are identical to per capita caps and sinking lids) and no lagged treatment effects. Although point estimates for models of EGMs and Class 4 venues are now not statistically different from zero, the simplified model estimates an 11.7% decline in player losses upon enacting any Class 4 gambling policy beyond the Act.

Conclusions

The research aim of this paper is to understand the impact of local public health interventions on gambling activity. To conduct our empirical analysis, we gathered information on Class 4 gambling policies from all 67 TAs in NZ. This allowed us to construct a novel panel data set of TA-level Class 4 gambling policy types over time. In each year, a TA either had the baseline policy mandated by the Gambling Act 2003 or had more stringent regulation in the form of either an absolute cap on number of EGMs and/or venues; a per capita cap on number of EGMs and/or venues; or a sinking lid policy. We combined this policy information with data on machine spending from the DIA and demographic and economic indicators from Stats NZ and MBIE. A quasi-experimental difference-in-differences identification strategy relying on geographic and time variation in gambling policy is used to estimate the causal impact of Class 4 gambling policies on the number of venues, EGMs, and machine spending. Our analysis is at the TA-level and the sample period spans from 2010 to 2018.

We found that all three forms of policy intervention prevalent in NZ are effective in reducing Class 4 venues and EGMs relative to the reference group (i.e. TAs with no restrictions beyond those in the Gambling Act 2003). For example, absolute caps are estimated to reduce the number of EGMs by 67 (14.7%) and the number of venues by 7 (16.6%) on a per 100,000 population basis over one year. Estimated reductions are marginally larger for the per capita cap policy and lower for the sinking lid policy.

In terms of reducing machine spending, sinking lids and per capita caps appear the most effective. Compared to the reference group, these policies are associated with a cumulative reduction (sum of contemporaneous and lagged effects) in machine spending of between 13 and 14%. Absolute caps were shown to reduce cumulative expenditure by 10%, relative to the reference group. Sinking lids are the only policy estimated to reduce machine spending in both contemporaneous and lagged years.

There are three notable limitations that deserve discussion. First, we do not know the source of reduction in machine spending. More specifically, without individual-level data we cannot ascertain what proportion of the drop in spending is from casual gamblers compared to problem gamblers.

Second, we do not have information on other forms of gambling activity. Therefore, we do not know if the drop in machine spending created spill-over effects, such as a rise in online gambling activity. We also don’t have information on additional measures (perhaps more informal in nature) undertaken by TAs to try and curb problem gambling. Although, we can potentially assume that the policy intervention employed (whether absolute cap, per capita cap or sinking lid) is not only a signal of the level of commitment a TA has towards trying to reduce problem gambling, but also a proxy for the likely level of other informal activities aimed at this goal.

Third, policy changes are likely endogenous in our econometric model of Class 4 gaming outcomes—that is, certain events at the TA-level may simultaneously cause TAs to enact certain Class 4 gambling policies, and also directly affect EGM densities and gambling expenditure. For example, if several new Class 4 venues open within a particular year, by availability theory this would be expected to increase machine spending, and that several new venues opened within a short period of time could cause the local government to enact tougher gaming restrictions. In this case it is problematic to attribute any changes in subsequent spending to the policy itself. As another example, there may be cultural heterogeneity at the TA-level, where some regions have a less favorable view of Class 4 gaming in general. One might reasonably expect less Class 4 gambling and tougher gambling restrictions in such a TA. For these reasons, it is difficult to precisely identify a causal link between local gambling policy and machine spending. We note, however, that the inclusion of TA and time fixed effects should control for many forms of policy endogeneity. Any unobservable characteristics that do not change over time, such as a local culture of gambling disapproval, are captured by TA-level fixed effects. Any trends that occur over time, such as increasing spending due to new venues opening, is captured by time fixed effects.

Our results support the availability hypothesis. Recall that the availability hypothesis simply asserts that the more exposure individuals have to gaming outlets, the more gambling activity occurs. Over our sample period, we observe significant declines in Class 4 venues and EGMs on a per 100,000 basis at the TA-level. We also observe substantial declines in real per capita EGM spending at the TA-year-level. Further, we find evidence that stringent Class 4 gaming policies, including absolute caps, per capita caps, and sinking lids—designed to reduce the availability of gambling outlets, significantly decrease machine spending.

Data availability

Data on gambling expenditure, electronic gaming machines, and Class 4 gambling venues are publicly available on the New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs website. Data on local Class 4 gambling regulations are also publicly available and will be provided by the corresponding author upon request. Data on problem gambling intervention services may be requested from the New Zealand Ministry of Health.

Notes

We refer to a business that hosts Class 4 gaming as a “Class 4 venue”

More information on the NZ Deprivation Index can be found at the University of Otago website, https://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/departments/publichealth/research/hirp/otago020194.html (accessed 7 October 2020).

For comparison, in 2002 the percentage of problem gamblers that chose casino slot machines as their primary mode of gambling was ten percent.

References

Abbott, M. (2006). Do EGMs and problem gambling go together like a horse and carriage? Gambling Research: Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies (Australia), 18(1), 7.

Abbott, M. (2017). Gambling and gambling harm in New Zealand: A 28-year case study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(6), 1221–1241.

Abbott, M., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2016). New Zealand National Gambling Study: Wave 3 (2014). Report number 5. Auckland: Auckland University of Technology, Gambling and Addictions Research Centre.

Abbott, M., Browne, M., Bellringer, M., Greer, N., Kolandai-Matchett, K., Rawat, V., Langham, E., Rockloff, M., Du Preez, K.P. (2017) Measuring the burden of gambling harm in New Zealand.

Abbott, M., & Volberg R. (1991) Gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand: A report on phase one of the national survey. Department of Internal Affairs, Research Series No. 12, Wellington, December.

Adams, P. J., Raeburn, J., & De Silva, K. (2009). A question of balance: Prioritizing public health responses to harm from gambling. Addiction, 104, 688–691.

AGLC, 2020. Liquor Licencee Handbook. Retrieved from: https://aglc.ca/documents/liquor-licensee-handbook

American Gambling Association. (2020). State of the States 2020. https://www.americangaming.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AGA-2020-State_of_the_States.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

Australian Institute for Gambling Research. (1995). Report of the first year of the study into the social and economic impact of the introduction of gaming machines to Queensland clubs and hotels. Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Department of Families, Youth and Community Care.

Bondolfi, G., Jermann, F., Ferrero, F., Zullino, D., & Osiek, C. H. (2008). Prevalence of pathological gambling in Switzerland after the opening of casinos and the introduction of new preventive legislation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(3), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01149.x

Bridwell, R. R., & Quinn, F. L. (2002). From mad joy to misfortune: The merger of law and politics in the world of gambling. Mississippi Law Journal, 72(2), 565–729.

Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372.

Campbell, F., & Lester, D. (1999). The impact of gambling opportunities on compulsive gambling. Journal of Social Psychology, 139(1), 126–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549909598366

Carr, R. D., Buchkoski, J. E., Kofoed, L., & Morgan, T. J. (1996). “Video lottery” and treatment for pathological gambling: A natural experiment in South Dakota. South Dakota Journal of Medicine, 49(1), 30–32.

Cunningham-Williams, R. M., Cottler, L. B., Compton, W. M., & Spitznagel, E. L. (1998). Taking chances: Problem gamblers and mental health disorders—Results from the St. Louis epidemiologic catchment area study. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1093–1096.

Department of Internal Affairs (2008, October, 6). Problem gambling in New Zealand – a brief summary. DIA. Retrieved from https://www.dia.govt.nz/diawebsite.nsf/wpg_URL/Services-Casino-and-Non-Casino-Gaming-Problem-Gambling-in-New-Zealand-A-Brief-Summary?OpenDocument.

Department of Internal Affairs (2020) GMP quarterly dashboard, retrieved from https://www.dia.govt.nz/diawebsite.nsf/wpg_URL/Resource-material-Information-We-Provide-Gaming-Machine-Proceeds-(GMP)-Data (accessed 06 October 2020)

Dowling, N., Smith, D., & Thomas, T. (2005). Electronic gaming machines: Are they the ‘crack cocaine’ of gambling? Addiction, 100(1), 33–45.

Engebø J., (2010) From slot machines to gaming terminals—experiences with regulatory changes in Norway. Vienna, September 2010, viewed 10 November 2011. Retrieved from http://www.easg.org/media/file/vienna2010/presentations/Thursday/1330/P2/4_Jonny_Engebo.pdf

Friedl, J., (2020). Online Resource: A State-By-State Slot Machine Casino Gambling Series. Professor Slots. Retrieved from https://professorslots.com/online-resource/

Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch, (2019). Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch Annual Report 2018/2019. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/sports-culture/gambling-fundraising/gambling-in-bc/reports-publications-statistics

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2018). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing (No. w25018). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Holland, K., Tu, D., Gray, R., Hudson, S., & Li, J. (2017). New Zealanders’ Knowledge, Views and Experience of Gambling and Gambling Harm: Results from the 2014 Health and Lifestyles Survey. Retrieved from http://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/New%20Zealanders%20Knowledge%20views%20and%20experience%20of%20gambling%20and%20gambling%20harm%202014%20%28002%29.pdf

Korn, D. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (1999). Gambling and the health of the public: Adopting a public health perspective. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15(4), 289–365.

Lesieur, H. R., & Rosenthal, R. J. (1991). Pathological gambling: A review of the literature (prepared for the American Psychiatric Association task force on DSM-IV committee on disorders of impulse control not elsewhere classified). Journal of Gambling Studies, 7(1), 5–39.

Livingstone, C., Rintoul, A., de Lacy-Vawdon, C., Borland, R., Dietze, P., Jenkinson, R., Livingston, M., Room, R., Smith, B., Stoove, M., Winter, R. & Hill, P. (2019). Identifying effective policy interventions to prevent gambling-related harm, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Melbourne. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/identifyingeffective-policy-interventions-to-prevent-gambling-related-harm-640/

Lund, I. (2009). Gambling behaviour and the prevalence of gambling problems in adult EGM gamblers when EGMs are banned. A natural experiment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9127-y

MacKinnon, J. G. (2019). How cluster-robust inference is changing applied econometrics. Canadian Journal of Economics/revue Canadienne D’économique, 52(3), 851–881.

McMillen, J., & Doran, B. (2006). Problem gambling and gaming machine density: Socio-spatial analysis of three Victorian localities. International Gambling Studies, 6(1), 5–29.

National Center for Responsible Gaming. (2012). Gambling and health in the workplace: A research-based guide about gambling disorders for human resources and employee assistance professionals. Massachusetts.

National Research Council. (1999). Pathological gambling: A critical review. DC National Academy Press.

Nevada Gaming Commission & Nevada Gaming Control Board. (2020). State of Nevada Regulations. Retrieved from: gaming.nv.gov/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=16507

Norsk Tipping. (2010). Annual and social report 2010. Norsk Tipping. Viewed 10 November 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.norsk-tipping.no/selskapet/_binary?download=true&id=48334

Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation. (2005). VLT Time Change: Findings Report.

Paton-Simpson, G.R., Gruys, M.A., & Hannifin, J.B. (2003) Problem gambling counselling in New Zealand: 2002 national gambling statistics. Problem Gambling Purchasing Agency, Palmerston North, April.

Petry, N. M. (2005). Pathological gambling: Etiology comorbidity and treatments. American Psychological Association Press.

Petry, N. M., Stintson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and psychiatric disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 564–574.

Rook, H., Rippon, R., Pauls, R., Doust, E., & Prince, J. (2018). Gambling harm reduction needs assessment. Sapere Research Group.

Rossen, F. (2015). Gambling and Problem Gambling: Results of the 2011/12 New Zealand Health Survey. Centre for Addiction Research, Prepared for the Ministry of Health. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland UniServices Limited, The University of Auckland.

South Australian Centre for Economic Studies (2005). Study of the impact of caps on electronic gaming machines. Retrieved from: https://www.adelaide.edu.au/saces/system/files/media/documents/2019-06/study-of-the-impact-of-caps-on-electronic-gaming-machines.pdf

Stevens, M., & Livingstone, C. (2019). Evaluating changes in electronic gambling machine policy on user losses in an Australian jurisdiction. BMC Public Health, 19, 517. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6814-1

Storer, J., Abbott, M., & Stubbs, J. (2009). Access or adaptation? A meta-analysis of surveys of problem gambling prevalence in Australia and New Zealand with respect to concentration of electronic gaming machines. International Gambling Studies, 9(3), 225–244.

Sulkunen, P., Babor, T. F., Ornberg, J. C., Egerer, M., Hellman, M., Livingstone, C., Marionneau, V., Nikkinen, J., Orford, J., Room, R. & Rossow, I. (2018) The effects of changing availability. Setting limits: Gambling, science and public policy. Oxford Scholarship Online

Szczyrba, Z., Fiedor, D., & Smolová, I. (2016). Gamblerization of Post-Communist Society in Central Europe. 16th International Conference on Gambling & Risk Taking, June 8, 2016, Las Vegas. Audio recording available at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/gaming_institute/2016/June8/15/

Tu, D., & Puthipiroj, P. (2015). New Zealanders’ Participation in Gambling: Results from the 2014 Health and Lifestyles Survey. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency Research and Evaluation Unit.

Thimasarn-Anwar, T., Squire, H., Trowland, H. & Martin, G. (2017). Gambling report: Results from the 2016 Health and Lifestyles Survey. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency Research and Evaluation Unit.

Volberg, R. A. (1994). The prevalence and demographics of pathological gamblers: Implications for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 84(2), 237–241.

Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Ontario problem gambling research centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and long term care.

Ward, A.D., Trowland, A. & Bracewell P. (2019) The dynamic deprivation index: Measuring relative socio-economic deprivation in NZ on a monthly basis, Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 14(1), 157–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2019.1578807

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Arthur Grimes, Matthew Browne, John Wren, Eugene Rees, Cathy Nijman, Kerry Fitchett, and seminar attendees at the 2020 New Zealand Workshop on Applied Microeconomics, the School of Economics Seminar Series at Auckland University of Technology, and the School of Economics Seminar Series at the University of Wollongong for helpful comments. The authors are solely responsible for any errors.

Funding

This study was funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Code availability

The corresponding author will provide a Stata executable file upon request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erwin, C., Pacheco, G. & Turcu, A. The Effectiveness of Sinking Lid Policies in Reducing Gambling Expenditure. J Gambl Stud 38, 1009–1028 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10069-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10069-4