Abstract

As the genetic counseling field evolves, a comprehensive model of practice is critical. The Reciprocal-Engagement Model (REM) consists of 5 tenets and 17 goals. Lacking in the REM, however, are well-articulated counselor strategies and behaviors. The purpose of the present study was to further elaborate and provide supporting evidence for the REM by identifying and mapping genetic counseling strategies to the REM goals. A secondary, qualitative analysis was conducted on data from two prior studies: 1) focus group results of genetic counseling outcomes (Redlinger-Grosse et al., Journal of Genetic Counseling, 2015); and 2) genetic counselors’ examples of successful and unsuccessful genetic counseling sessions (Geiser et al. 2009). Using directed content analysis, 337 unique strategies were extracted from focus group data. A Q-sort of the 337 strategies yielded 15 broader strategy domains that were then mapped to the successful and unsuccessful session examples. Differing prevalence of strategy domains identified in successful sessions versus the prevalence of domains identified as lacking in unsuccessful sessions provide further support for the REM goals. The most prevalent domains for successful sessions were Information Giving and Use Psychosocial Skills and Strategies; and for unsuccessful sessions, Information Giving and Establish Working Alliance. Identified strategies support the REM’s reciprocal nature, especially with regard to addressing patients’ informational and psychosocial needs. Patients’ contributions to success (or lack thereof) of sessions was also noted, supporting a REM tenet that individual characteristics and the counselor-patient relationship are central to processes and outcomes. The elaborated REM could be used as a framework for certain graduate curricular objectives, and REM components could also inform process and outcomes research studies to document and further characterize genetic counselor strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The genetic counseling profession has evolved steadily over the past five decades, in part due to continual advancements in genetic technology. As the profession progresses, there is a growing need to establish comprehensive practice models describing why and how services are delivered to patients (Bernhardt et al. 2000; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). Models of practice consist of tenets, goals, strategies, and behaviors that characterize the field (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007).

A model of practice for genetic counseling provides a critical framework as the field endeavors to empirically document the processes and outcomes of genetic counseling (Bernhardt et al. 2000; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). The Reciprocal-Engagement Model (REM; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007), comprising one proposed model of genetic counseling practice, delineates five tenets (fundamental assumptions or beliefs) and 17 goals of genetic counseling practice (see Table 1 for complete listing of REM tenets and goals). To date, two studies have provided evidence for the validity of the REM goals (Hartmann et al. 2015; Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2015). The REM is a work in progress, however, as specific genetic counseling strategies, behaviors and outcomes related to the 17 goals have yet to be fully articulated and validated (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to further elaborate and provide supporting evidence of the REM by identifying genetic counselors’ and genetic counseling researchers’ perceptions of strategies that occur in genetic counseling sessions and mapping said strategies to REM goals.

Overview of Genetic Counseling Models of Practice

Historical Models

Historically, genetic counseling has drawn upon preexisting models of practice and methods from medicine, education, and psychology (McCarthy Veach et al. 2002). As the profession has evolved, genetic counseling has continued to borrow from a “teaching model” specific to healthcare and a “counseling model” grounded in psychology. While genetic counseling may be viewed as bridging these apparently related fields (Lewis 2002), there are important distinctions in healthcare and psychology that render them insufficient for capturing the profession (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007).

The teaching framework is based on a tenet that individuals seek genetic counseling for information; accordingly, the role of the genetic counselor is that of an educator. Genetic counselors, within a teaching model, use strategies and behaviors that “achieve neutrality, even-handedness, impartiality, and noncoerciveness” and are consistent with the tenet of nondirectiveness (Kessler 1997, p. 289). In contrast, the counseling framework is based on a belief that individuals seek genetic counseling for reasons that extend beyond information alone. Specifically, they seek support, alleviation of psychological distress, and promotion of autonomy and a greater sense of control regarding their life situation. Within this model, genetic counselors’ strategies and behaviors are aimed at “assess[ing] the counselees' strengths and limitations, needs, values, and decisional trends” (Kessler 1997, p. 290). Genetic counselors must possess a variety of counseling skills they tailor to each patient’s specific needs.

Genetic counselors typically draw from both models to differing degrees, and within the profession, there appears to be division about the validity of each one (Macleod et al. 2002). Kessler (1997) asserts that genetic counseling has endorsed the use of a teaching model over a counseling model. A few studies suggest that indeed genetic counselors pay less attention to the psychological and social needs of clients (e.g., Meiser et al. 2008). Nonetheless, some authors advocate for a more psychosocial model of genetic counseling (e.g., Austin et al. 2014; Biesecker 2003; Redlinger-Grosse 2016; Weil 2003; Yager 2014).

The Reciprocal-Engagement Model (REM)

Some authors have called for an independent, precisely defined model of genetic counseling (Biesecker 2003; Kessler 2000; McCarthy Veach et al. 2003). McCarthy Veach et al. (2007) proposed the REM as a practice model exclusive to genetic counseling. They developed the REM based on the results of a two-day consensus conference attended by genetic counseling program directors or their representatives (N = 23) from 20 of the 30 genetic counseling graduate programs in North America accredited at that time. Additionally, they incorporated in the model consultation with conference speakers, extant literature, and their own professional experience (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). Conference attendees were asked to define four components of the model of genetic counseling practice being taught in genetic counseling programs at that time. In order to guide discussion, they used Rieh and Ray’s (1974) definitions of the four components of a model: 1) Tenet - a principle, doctrine, or belief held in common by members of a group; 2) Goal - an aim, purpose; content specified as aim for activity; 3) Strategy - a careful plan or method, especially for achieving an end; and 4) Behavior - An action or reaction; personal conduct. Using these definitions, participants worked to develop consensus about the specific tenets and goals of genetic counseling. Time constraints precluded their ability to articulate more than a handful of strategies and behaviors.

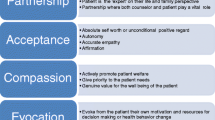

The REM emphasizes the counselor-patient relationship as the “conduit for processes and outcomes of genetic counseling” (McCarthy Veach et al. 2010, p. 3). The model consists of 5 genetic counseling tenets: genetic information is key, relationship is integral to genetic counseling, patient autonomy must be supported, patients are resilient, and patient emotions make a difference, and there are 17 corresponding goals. The five tenets mutually influence each other, and the genetic counselor-patient relationship is at the center (See Fig. 1).

The Reciprocal-Engagement Model (REM) of genetic counseling practice. Source: McCarthy Veach et al. (2007) Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Genetic Counseling

Hartmann et al. (2015) obtained evidence for the validity of the REM’s 17 goals in a survey of 194 practicing genetic counselors who rated the importance and feasibility of each goal. Factor analysis yielded four factors that accounted for 51% of the variance in participants’ ratings of the importance of each goal: Understanding and Appreciation, Support and Guidance, Facilitative Decision-Making, and Patient-Centered Education. Frequency ratings and open-ended comments about the REM goals suggest the goals may vary in their relevance and feasibility based on patient characteristics and/or genetic counseling specialty, and their attainment may be influenced by factors such as time-constraints of sessions. Hartmann et al. (2015) also asked their participants to provide one example of a successful genetic counseling session and one example of a session they regarded as not particularly successful. These data are not reported in their published article, and they comprise one of the data sets analyzed in the present study.

Research on Genetic Counseling Strategies

To date, a handful of researchers have studied genetic counseling strategies. Benkendorf et al. (2001) found that genetic counselors in reproductive genetic counseling engaged in three common activities: initiating transitions to the next agenda topic, providing medical information or instruction to patients, and facilitating patient decision-making. Hallowell et al. (1997) identified four counseling strategies in sessions with women receiving genetic counseling for familial breast and/or ovarian cancer: determining the patient’s agenda, drawing a family tree, estimating patient risk, and discussing appropriate risk management. Lobb et al. (2001) found two types of in-session strategies for women at high risk for familial breast cancer: providing information and communication.

Ellington et al. (2006) documented four discrete patterns of genetic counselors’ communication strategies: counselor-driven psychosocial communication (i.e., high level of genetic counselor psychosocial talk and low level of biomedical information), client-focused psychosocial communication (i.e., high level of genetic counselor questions and receptivity to client responses and low amount of biomedical information), client-focused biomedical communication (i.e., client and counselor provide biomedical information in high to moderate levels), and biomedical question and answer communication (i.e., high levels of client questions and genetic counselor biomedical talk). Roter et al. (2006) identified two teaching patterns of communication strategies (clinical and psychoeducational) and two counseling patterns (support and psychosocial). The patterns of teaching practice (and associated strategies and behaviors) included: high level of clinical information presented with a low proportion of open to close ended questions (clinical teaching); presentation of more personalized information and a greater balance between clinical and psychosocial content (psycho-educational teaching); low level of clinical and psycho-educational information presented and high level of emotional talk (supportive counseling); and high levels of psychosocial exchange and psychosocial questioning (psychosocial counseling). In a critical review of 18 studies of genetic counseling communication, Meiser et al. (2008) found prevalent communication patterns consistent with a biomedical model, such that counselors talked more than their patients.

Lerner et al. (2014) examined communication of genetic test results for susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease in 262 genetic counseling sessions. Identified behaviors included biomedical and psychosocial questioning and information giving and efforts to build partnerships. They identified three main patterns of communication: Biomedical-Provider-Teaching (40%), Biomedical-Patient-Driven (34.4%), and Psychosocial-Patient-Centered (26%). Meiser et al. (2008) concluded that genetic counseling communication behaviors are inconsistent with a more broadly defined model of genetic counseling that incorporates both a biomedical and psychosocial communication exchange.

Purpose of the Study

The REM comprises an initial step in delineating tenets, goals, strategies and behaviors of genetic counseling practice, but further research is needed to more fully identify strategies specific to the model (Fox et al. 2007; Hartmann et al. 2015; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). A more comprehensive, empirically-derived understanding of genetic counseling will not only help to define the field’s current contribution in healthcare, but also provide a foundation on which to base future empirically-supported clinical interventions. Therefore, the overall aims of the present study were to more fully develop the REM by more fully articulating genetic counseling strategies associated with the 17 REM goals, and provide further supporting evidence of the model.

Methods

The present research involves a secondary, qualitative analysis of data gathered from two prior investigations. The first data set originated from a focus group study of genetic counselors’ and genetic counseling researchers’ perceptions of genetic counseling outcomes and behaviors associated with the REM (see Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2015 for a full description of the methodology and participant demographics). Transcripts from these focus groups comprise Data Set #1 in the present study. The second data set (Data Set #2) is comprised of genetic counselor written examples of 67 successful and 63 unsuccessful genetic counseling sessions collected in a survey validation study of practicing genetic counselors’ perceptions of the importance and feasibility of the 17 REM goals (see Geiser et al. 2009; Hartmann et al. 2015 for complete methodology). See Supplementary Table 1 for participant demographics for Data Sets #1 and #2.

Procedures and Data Analysis

Following receipt of approval for exempt status from the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, analysis of Data Sets #1 and #2 proceeded in multiple steps consistent with the purposes of the present study. Figure 2 provides an overview of the methods for the present study.

Purpose 1: Articulation of Genetic Counselor Strategies Associated with the 17 REM Goals.

Data Set #1 (Focus Group Transcripts)

The first author analyzed the five focus group transcripts using a theory-driven process (MacFarlane and O’Reilly-de Brun 2012) to extract genetic counselor strategies. The classifications were independently reviewed and audited by the second and fourth authors. A finalized list of genetic counselor strategies, along with their corresponding REM goal(s) was then used as an a priori codebook for analysis of Data Set #2.

Data Set #2 (Successful and Unsuccessful Genetic Counseling Sessions)

The first author and a research assistant conducted a directed content analysis (Curtis et al. 2001; Elo and Kyngäs 2008; Hsieh and Shannon 2005) of the 67 successful and 63 unsuccessful genetic counseling session examples contained in Data Set #2. They coded each example using the REM goal(s) that were mentioned as being accomplished in the successful sessions and goals that were mentioned as not being accomplished in the unsuccessful sessions. They then attempted to code the corresponding strategies using the strategies contained in the a priori codebook. Of note, the REM goal(s) and by extension, strategies that were identified as present in the successful sessions and as lacking in the unsuccessful sessions were based solely on the descriptions provided. The data were not sufficient to discern additional goals and strategies not mentioned by respondents.

The second author audited the coding and provided feedback resulting in some modification of the process. Specifically, the strategies contained in the a priori codebook were noted to occur in the session examples with very limited frequency. The first author and the auditor concluded that their precise nature was too stringent for analyzing the written descriptions of the genetic counseling sessions. Thus, a decision was made to classify the genetic counselor strategies in Data Set #2 into broader conceptual domains. Using a Q-sort technique, a qualitative methodology for grouping a larger data set into smaller, more meaningful domains Akhtar-Danesh et al. 2008; Dziopa and Ahern 2011), they classified the specific strategies contained in the a priori codebook into broader strategy domains. Thus, the modified a priori codebook consisted of each of the 17 REM goals along with the broader strategy domains and corresponding categories (i.e., specific strategy examples that illustrated each domain) (See Table 1).

The successful and unsuccessful sessions were coded using the modified a priori codebook to capture the presence or absence of strategies and corresponding categories. If a new category emerged from a session (either because it was an entirely new strategy or it was a new strategy for the specified REM goal), it was noted and added to the modified a priori codebook as a category example to aid in defining a particular domain. The auditor reviewed the coding throughout this process, and any discrepancies were discussed to reach concordance.

Purpose 2: Provide Further Supporting Evidence for the REM

Frequencies and t-tests were calculated based on the coding of both Data Sets #1 and #2 as a means to offer supporting evidence of the REM. Directed content analysis looks for supporting and non-supporting evidence for a theory by examining frequencies and meaningful statistical differences (Curtis et al. 2001; Hsieh and Shannon 2005). Analyses included determining: 1) Frequency of strategy domains found in Data Sets #1 and #2; 2) Frequency of REM goals identified in Data Set #2 (in successful and unsuccessful session examples); and 3) Frequency of strategy domains by each REM goal identified in Data Set #2 (successful and unsuccessful session examples). In addition, t-tests of unequal variances were performed to look for statistically significant differences between the mean word count between the successful and unsuccessful session examples in Data Set #2, as well as to look for differences in the mean frequencies of the REM goals identified in the successful and unsuccessful sessions.

Additional Analyses

During the coding of Data Set #2, it was incidentally noted that many participants commented on how the patient either contributed to the success or lack of success of the session. Each example was coded as either the presence or absence of a patient contribution. Finally, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range, median, percentage) were calculated for demographic data for participants in Data Sets #1 and 2.

Results

Q-Sort of Strategies from Focus Group Data

A Q-sort of the 337 unique strategies contained in the a priori codebook from Data Set #1 resulted in 15 broader domains of genetic counselor strategies (see Table 2): assessment; collaborate with other health professionals; empower patient; establish genetic counseling goals and expectations; establish good communication; establish working alliance; facilitate decision-making; facilitate patient care; information gathering; information giving; practice self-awareness; provide pre and post-GC session care; provide culturally competent care; provide resources; and use psychosocial counseling skills/strategies. Each of the 15 domains was determined based on the conceptual similarity of the strategies contained therein. For example, the domain “Assessment” is comprised of categories such as “Assess family dynamics,” “Assess informational needs,” and “Assess patient’s nonverbal behaviors.” The domain “Information giving” is comprised of categories such as “Provide education/information,” "Tailor information based on patient's needs," and “Utilize diagrams/pictures to explain information.”

Genetic Counselor Strategies from the Examples of Genetic Counseling Sessions

Table 2 contains a list of the 15 strategy domains along with illustrative quotations from Data Set #1 and Data Set #2. The domains were identified as present in successful sessions and lacking in unsuccessful sessions. The domains are organized by corresponding REM goals, and the goals are grouped within the four factors described by Hartmann et al. (2015).

The REM was further evaluated by examining: 1) the frequency of the REM goals in Data Set #2; and 2) the frequency of the strategy domains by each REM goal identified in Data Set #2. First, in order to account for possible differences due to length of the successful and unsuccessful session examples, a mean word count was calculated. Results of a t-test indicated no statistically significant difference between the successful and unsuccessful session examples, t(128) = 1.16, p = .25 [mean = word 95.7 words (SD = 60.1 words), and mean = 108.6 words (SD = 66.2 words), respectively].

The mean number of REM goals identified as accomplished in each successful session was 4.16 (Possible range: 0–17; SD = 1.96). In contrast, the mean number of REM goals identified as not accomplished in each unsuccessful session was 2.83 (Possible range: 0–17; SD = 1.14). This is a statistically significant difference, t(128) = 4.72, p < 0.01.

The REM goals identified as being accomplished in the greatest number of successful session examples were: "Counselor helps the patient feel informed" (n = 43/67), and "Counselor knows what information to impart to each patient" (n = 34/67). Both of these goals are part of Factor 3: Facilitative Decision-Making.

The REM goals identified as not being accomplished in the greatest number of unsuccessful sessions were: "Counselor and patient establish a bond” (n = 27/63) (Factor 2: Support and Guidance; "Counselor works with patient to recognize concerns that are triggering the patient's emotions" (n = 26/63) (Factor 1: Understanding and Appreciation); “Counselor helps patient feel informed” (n = 26/63) (Factor 3: Facilitative Decision-Making); and “Good counselor-patient communication occurs” (n = 26/63) (Factor 4: Patient-Centered Education).

Overall, 12 of the 15 different strategy domains were identified as present in the successful sessions compared to 14 of the 15 different strategy domains identified as lacking in the unsuccessful sessions. One strategy domain “Collaborate with health professionals” was not identified in either successful or unsuccessful sessions.

The strategy domains present in the largest number of successful session examples were “Information Giving” [65.7% (44/67)] and "Use Psychosocial Counseling Skills and Strategies" [44.8% (30/67)]. The strategy domains lacking in the largest number of unsuccessful session examples were “Information Giving” [33.3% (21/63)] and Working Alliance [30.2% (19/63)].

Across the successful sessions, the REM goals with the greatest number of corresponding strategy domains were "Counselor helps the patient feel informed" (n = 14), "Counselor knows what information to impart to each patient" (n = 14) and “Counselor and patient establish a bond (n = 14). Across the unsuccessful sessions, the unaccomplished REM goals with the greatest number of strategy domains identified as lacking were: “Good counselor-patient communication occurs” (n = 13), “Counselor helps the patient to feel informed” (n = 12), "Counselor and patient establish a bond" (n = 11). Across the successful sessions, the goals with the fewest number of strategy domains were: "Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient self-esteem" (n = 6), and "Counselor's characteristics positively influences the process of relationship-building and communication between counselor and patient" (n = 3). Across the unsuccessful sessions, none of the strategy domains were identified as lacking for these goals: "Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient self-esteem," and “Counselor recognizes patient strengths.”

Patient Contribution

In a majority of the successful and unsuccessful sessions (79.1% and 85.7%, respectively), participants noted their perceptions of the patient’s contribution to the success or lack of success. Specifically, for successful sessions, participants mentioned patient engagement and desire to understand the presented information as ultimately leading to a successful decision and/or adjustment to a genetic diagnosis. Additionally, participants often mentioned the patient’s ability to emotionally open up to the genetic counselor as contributing to several successful aspects of the session - the working alliance, the patient’s understanding of the information, and the counselor’s ability to empower the patient’s decision-making and adaptation. Conversely, in the unsuccessful sessions, participants often mentioned the patient’s lack of engagement in the genetic counseling process and/or with the genetic counselor as being detrimental. In those instances, participants mentioned emotional factors that contributed to the patient’s inability to connect with the counselor and/or to hear the genetic information and recommendations the counselor presented. Table 3 contains examples of successful and unsuccessful sessions that illustrate the patient’s contributions.

Discussion

The present study extends and provides supporting evidence of the Reciprocal-Engagement Model (REM) of genetic counseling by: 1) more fully articulating genetic counseling strategies associated with the goals of the REM; and b) qualitatively demonstrating the presence and absence of genetic counselor goals and strategies in sessions genetic counselors perceive as being successful and unsuccessful. Data analyzed in the present research were obtained from two prior studies (Geiser et al. 2009; Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2015). The following sections contain a discussion of major findings, study limitations, implications for clinical training, research recommendations, and conclusions.

Genetic Counselor Strategies Associated with the REM Goals

Three-hundred thirty-seven individual strategies were identified from analysis of the focus group transcripts generated by Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2015), and every strategy corresponds to one or more of the 17 REM goals. While not unexpected, as Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2015) grounded their study in the REM, the alignment of genetic counselor strategies with REM goals provides qualitative supporting evidence for the model. Moreover, the present analysis yielded a more elaborated set of strategies than occurred during initial development of the REM (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). As previous authors have asserted (Hartmann et al. 2015; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007), identification of strategies genetic counselors use to accomplish the goals of their practice is necessary to both validate the REM and increase its utility for practitioners and researchers.

Strategies

Fifteen strategy domains were identified that more broadly characterize the 337 categories of unique strategies reflected in the data. The domains range from in-session strategies (e.g., Assessment, Information giving, Use psychosocial counseling skills/strategies) to strategies employed outside of sessions (e.g., Provide pre and post-GC session care, Practice self-awareness). McCarthy Veach et al. (2007) discussed how within the REM, concepts such as "understanding, framing, and facilitating constitute genetic counselor macro goals, with assessment as a corresponding macro strategy" (p. 725). Similarly, the 15 strategy domains identified herein could be considered macro strategies that broadly capture numerous specific strategies genetic counselors use to accomplish the goals of their practice.

This study yielded a wider range of genetic counseling strategies than has been documented in previous research. To date, investigations of genetic counseling strategies have been less comprehensive and limited to particular specialties such as prenatal and cancer genetic counseling (Benkendorf et al. 2001; Hallowell et al. 1997; Lobb et al. 2001). The strategies identified in the present study appear to characterize major approaches of genetic counselors irrespective of clinical specialty. Moreover, they are congruent with the current definition of genetic counseling: "Interpretation of family and medical histories to assess the chance of disease occurrence or recurrence; education about inheritance, testing, management, preventions, research and counseling to promote informed choices and adaptation to the risk or condition" (Resta et al. 2006, p. 77). This congruence provides further support for the REM of genetic counseling practice.

A majority of the strategy domains (e.g., collaborate with health professionals, establish good communication, facilitate decision-making, facilitate patient care, information gathering, practice self-awareness) are also consistent with a number of the practice-based competencies established by the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC 2015). This congruence provides further support of the REM.

In both the focus group and genetic counseling session data sets, many of the 15 strategy domains were associated with multiple goals across the four factors identified by Hartmann et al. (2015). Thus, it appears that no strategy domain is unique to an individual goal or factor. Moreover, numerous strategies appear to be perceived as important for achieving each goal. These findings support the REM authors’ assertion that "each element of the model is complementary and completes the other" (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007, p. 724). The present findings support the reciprocal nature of the REM, as for every goal, there is an interplay of both informational and psychosocial strategies.

Further Examination of Supporting Evidence for the REM

Supporting evidence of the REM was further assessed by calculating frequencies of REM goals and strategy domains extracted from the examples of successful and unsuccessful genetic counseling sessions. The first author qualitatively examined how the four REM factors and corresponding goals were accomplished in successful sessions and not accomplished in unsuccessful sessions. Of note, the length (i.e., word count) of the successful and unsuccessful sessions was examined to ensure that differences in frequencies were not due to length. A statistically significant difference in length was not obtained.

Frequency of REM Goals

There was a significantly greater number of REM goals identified as being accomplished in successful sessions compared to those identified as not accomplished in unsuccessful sessions. These findings may support the importance of achieving multiple REM goals in order to yield desired genetic counseling outcomes. Alternatively, these differences might be due to counselors having a more difficult time identifying and/or conveying unmet goals in unsuccessful sessions. Another possible explanation (as noted in some examples) is that respondents were more focused on patient factors that contributed to lack of success. While the session examples solely represent counselors’ perceptions, they provide some evidence in support of the REM goals.

The specific goals noted as accomplished in successful sessions differed from those identified as not accomplished in unsuccessful sessions. Information-oriented goals ("Counselor helps the patient feel informed" and "Counselor knows what information to impart to each patient") were the most prevalent goals mentioned in successful sessions. These goals are part of Factor 3: Facilitative Decision-Making. This is not surprising as informational goals relate to the REM tenet “Genetic Information is Key” (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007), and they are goals that were rated as high in mean importance and frequency by participants in the Hartmann et al. (2015) study. The provision of clear, accurate, and up-to-date genetic information remains integral to the process of genetic counseling (ACGC 2015). The prevalence of informational goals in successful sessions may also be indicative of a teaching model in genetic counseling (Kessler 1997; Lerner et al. 2014; Meiser et al. 2008; Roter et al. 2006). Alternatively, informational goals can be more circumscribed and thus may be easier to note in depicting a genetic counseling session.

In contrast, goals commonly noted as not accomplished in unsuccessful sessions were more varied. Three of these goals, "Counselor and patient establish a bond," "Counselor works with patient to recognize concerns that are triggering the patient's emotions," and “Good counselor-patient communication occurs,” generally are more psychosocially-oriented. These findings may indicate genetic counselors’ continued lack of comfort and certainty with the “art of genetic counseling” (Austin et al. 2014; Yager 2014), or with the fact that they involve a more active role on the part of the patient. The findings might also be related to genetic counselors’ greater ability to identify concrete success vis a vis information-provision (Meiser et al. 2008) versus a more nebulous, lack of success related to one’s ability to employ psychosocial skills (Austin et al. 2014). These results suggest the importance of genetic counseling training and continuing education grounded in a psychosocial model such as the REM.

Prevalence of Strategy Domains

Overall, there were more total strategy domains identified as present in successful sessions than as lacking in unsuccessful sessions. These results are consistent with the previous speculation that participants were better able to identify what “went right” in successful sessions than what “went wrong” in unsuccessful ones.

The most prevalent strategy domains in successful sessions were “Information giving” and "Use of Psychosocial Skills and Strategies." These results support the reciprocal nature of the REM, especially in the ways counselors address patients’ information and psychosocial needs. They are somewhat congruent with previous studies examining the communication strategies used in genetic counseling (Ellington et al. 2006; Lerner et al. 2014; Meiser et al. 2008; Roter et al. 2006). For instance, those studies have shown the communication process involves information giving within a psychosocial communication pattern. Of note, however, prior studies also demonstrate a consistently high prevalence of communication patterns suggestive of a teaching model of practice, rather than a counseling model (Ellington et al. 2006; Lerner et al. 2014; Meiser et al. 2008; Roter et al. 2006). The results of the present study, in contrast, suggest psychosocial strategies are not siloed or separated from information provision strategies. Rather, psychosocial skills and strategies can be used to promote information provision and the educational goals of the profession. The strategy domain “Collaborate with health professionals” was not identified in either successful or unsuccessful sessions, which may indicate that this is a strategy utilized outside of the genetic counseling session.

Additional noteworthy findings concern the REM goals for which the fewest strategy domains were identified. For successful sessions, these were: “Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient self-esteem" and "Counselor's characteristics positively influences the process of relationship-building and communication between counselor and patient." For unsuccessful sessions, these were also: “Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient’s self-esteem,” as well as “Counselor recognizes patient strength,” both of which are less-immediate goals. It was noted during the coding process that these goals appear to be more subjective in nature and more difficult to operationalize, specifically, concepts such as “self-esteem” or “counselor characteristics.” These also are the goals identified by some participants in the Hartmann et al. (2015) study as either long-term (i.e., “Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient self-esteem”), inappropriate (e.g., Counselor promotes maintenance of or increase in patient self-esteem"), or not a goal of practice (i.e., “Counselor recognizes patient strengths”). Thus, the present results support a potential re-examination of these goals with respect to their importance and relevance to genetic counseling practice.

Patient Contribution

A majority of successful and unsuccessful session examples included mention of patients’ contributions to success (or lack thereof). The REM is built upon a Rogerian model (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007) and considers the counselor-patient relationship as a conduit for genetic counseling processes and outcomes. Prior studies have demonstrated the importance of the patient’s contribution in development and maintenance of the relationship, as well as in effective genetic counselor-patient communication (Anderson et al. 2015; Berkenstadt et al. 1999).

Elaboration of the REM

The present findings allow for a more complete description of the strategies associated with REM tenets and goals. Table 1 provides a summary of the elaborated REM: the five tenets (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007), four goal factors, 17 goals (Hartmann et al. 2015), and strategy domains associated with each goal. While the distribution of strategies varied across the four factors and 17 corresponding REM goals, the overall picture of strategy domains supports the need to balance educational and psychological support in the process of genetic counseling (Austin et al. 2014; Biesecker 2003; Kessler 2000; McCarthy Veach et al. 2003). The REM appears to capture strategies consistent with both the counseling and teaching models (Kessler 2000) and as a practice model, demonstrates that the profession is "neither exclusively education nor is it exclusively psychosocial" (McCarthy Veach et al. 2007, p.725).

Study Limitations

There are several study limitations. The two data sets originated from studies that have inherent limitations. Redlinger-Grosse et al.’s (2015) focus group participants represent a small number of practicing genetic counselors, outcome researchers and training directors, and the participants may have been influenced by each other’s opinions, as well as by the group moderators. The successful and unsuccessful sessions identified by Geiser’s et al. (2009) genetic counselors are self-report, retrospective survey data lacking in the detail and nuance of interview data. The REM is based on genetic counseling practice in North America, and participants in the Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2015) and Geiser et al. (2009) studies were from that same geographic region. The extent to which the REM and the present findings reflect genetic counseling practice on an international level is unknown.

The directed content analysis methods used to analyze the data sets has inherent bias because researchers are more likely to find supportive rather than non-supportive evidence of the theory of interest (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). As the strategies comprising the a priori codebook were based originally on the REM, further research is needed to quantitatively validate the present findings in actual genetic counseling sessions.

The broad strategy domains identified in this study are based on numerous categories of strategies extracted from the focus group data. Given their highly specific nature and generally low prevalence in the genetic counseling session examples, the categories were “too thinly” sliced to be useful for the data analysis. The difficulty capturing specific strategies in an informative and parsimonious way may reflect the complex and subtle nature of genetic counseling processes (Hartmann et al. 2015; McCarthy Veach et al. 2007). Further research should more fully document strategies using observational or analogue designs.

Training Implications

Previous authors (Fox et al. 2007; Hartmann et al. 2015; McCarthy Veach et al. 1999) assert there is a need to systematically train students to work toward a model of practice that captures the unique strategies used in the field. The extension of the REM too include strategies may assist genetic counseling graduate programs to better define educational goals and objectives in accordance with an empirically-supported practice model. As stated, the strategy domains parallel many of the practice-based competencies set forth by the ACGC for preparing students to be entry level genetic counselors (ACGC 2015). Training programs may want to consider presenting training goals and objectives to students within the framework of the REM.

The present findings also suggest the importance of training and continuing education in both information giving skills and psychosocial skills. As genetic information expands, there is an ongoing struggle within the profession to “make room” in program curricula and continuing education venues for informational content. The present findings support calls for training in counseling skills commensurate with the changing informational needs of patients (cf. Austin et al. 2014; Yager 2014).

Research Recommendations

A next step in supporting and expanding the REM involves observational or analogue (simulated) studies to determine the extent to which the REM characterizes actual practice. Research of this type would help to identify the behaviors associated with the 17 REM goals and their corresponding strategies; counselor behaviors, in particular, could not be precisely identified in this study. Researchers should also examine how the REM generalizes to practice across multiple specialty areas and different geographic regions. Finally, identification of patients’ role in successful and unsuccessful genetic counseling interactions would aid understanding of how best to implement the REM.

Conclusions

This study further articulated strategies that correspond to the goals and tenets of the Reciprocal-Engagement Model of genetic counseling practice. Analysis of examples of successful and unsuccessful sessions yielded goals and strategies consistent with the REM, thus providing supporting evidence for the model. The findings help to elaborate the REM by more fully capturing the processes of genetic counseling sessions. As models are most useful when they can be applied broadly (Fox et al. 2007), arguably this extension of the REM will increase its applicability to a range of genetic counseling practice specialties and settings, enhance its utility as a model for linking genetic counseling processes to outcomes, and promote research documenting the effectiveness of practice (Redlinger-Grosse et al. 2015). An empirically-supported, comprehensive model of practice such as the REM may enhance genetic counseling services, by providing a framework for education, training, practice, and research.

References

ACGC (2015). ACGC Core Competencies. Retrieved from http://www.gceducation.org/Documents/ACGC%20Core%20Competencies%20Brochure_15_Web.pdf.

Akhtar-Danesh, N., Baumann, A., & Cordingley, L. (2008). Q-methodology in nursing research: a promising method for the study of subjectivity. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 30(6), 759–773. doi:10.1177/0193945907312979.

Anderson, S. R., Berrier, K. L., Redlinger-Grosse, K., & Edwards, J.G. (2015). The genetic counselor-patient relationship following a life-limiting prenatal diagnosis: an exploration of the Reciprocal-Engagement Model. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Austin, J., Semaka, A., & Hadjipavlou, G. (2014). Conceptualizing genetic counseling as psychotherapy in the era of genomic medicine. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 23, 903–909 http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-014-9728-1.

Benkendorf, J. L., Prince, M. B., Rose, M. A., De Fina, A., & Hamilton, H. E. (2001). Does indirect speech promote nondirective genetic counseling? Results of a sociolinguistic investigation. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 106, 199–207. doi:10.1002/ajmg.10012.

Berkenstadt, M., Shiloh, S., Barkai, G., Katznelson, M., & Goldman, B. (1999). Perceived personal control: a new concept in measuring outcome of genetic counseling. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 82, 53–59.

Bernhardt, B. A., Biesecker, B. B., & Mastromarino, C. L. (2000). Goals, benefits, and outcomes of genetic counseling: client and genetic counselor assessment. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 94, 189–197.

Biesecker, B. B. (2003). Back to the future of genetic counseling: commentary on “Psychosocial genetic counseling in the post-nondirective era”. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 12, 213–217.

Curtis, J. R., Wenrich, M. D., Carline, J. D., Shannon, S. E., Ambrozy, D. M., & Ramsey, P. G. (2001). Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 41–49.

Dziopa, F., & Ahern, K. (2011). A systematic literature review of the applications of Q-technique and its methodology. Methodology, 7, 39–55. doi:10.1027/1614-2241/a000021.

Ellington, L., Baty, B. J., McDonald, J., Venne, V., Musters, A., Roter, D., et al. (2006). Exploring genetic counseling communication patterns: the role of teaching and counseling approaches. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 15, 179–189.

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

Fox, M., Weil, J., & Resta, R. (2007). Why we do what we do: commentary on a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16, 729–730. doi:10.1007/s10897-007-9118-z.

Geiser, J., LeRoy, B., McCarthy Veach, P., Bartels, D., & Berry, S. (2009). Identifying success in genetic counseling sessions: counselor perceptions of the goals of the reciprocal engagement model. University of Minnesota.

Hallowell, N., Statham, H., Murton, F., Green, J., & Richards, M. (1997). “Talking about chance”: the presentation of risk information during genetic counseling for breast and ovarian cancer. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 6, 269–286.

Hartmann, J. E., Veach, P. M., MacFarlane, I. M., & LeRoy, B. S. (2015). Genetic counselor perceptions of genetic counseling session goals: a validation study of the reciprocal-engagement model. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24, 225–237. doi:10.1007/s10897-013-9647-6.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288.

Kessler, S. (1997). Psychological aspects of genetic counseling. IX. Teaching and counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 6, 287–295.

Kessler, S. (2000). Closing thoughts on supervision. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 9, 431–434.

Lerner, B., Roberts, J. S., Shwartz, M., Roter, D. L., Green, R. C., & Clark, J. A. (2014). Distinct communication patterns during genetic counseling for late-onset Alzheimer’s risk assessment. Patient Education and Counseling, 94, 170–179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.019.

Lewis, L. J. (2002). Models of genetic counseling and their effects on multicultural genetic counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 11, 193–212.

Lobb, E., Butow, P., Meiser, B., Tucker, K., & Barratt, A. (2001). How do geneticists and genetic counselors counsel women from high-risk breast cancer families? Journal of Genetic Counseling, 10, 185–199.

MacFarlane, A., & O’Reilly-de Brun, M. (2012). Using a theory-driven conceptual framework in qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 607–618. doi:10.1177/1049732311431898.

Macleod, R., Craufurd, D., & Booth, K. (2002). Patients’ perceptions of what makes genetic counselling effective: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 145–156. doi:10.1177/1359105302007002454

McCarthy Veach, P., Truesdell, S. E., LeRoy, B. S., & Bartels, D. M. (1999). Client perceptions of the impact of genetic counseling: an exploratory study. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 8, 191–216.

McCarthy Veach, P., Bartels, D. M., & LeRoy, B. S. (2002). Commentary on genetic counseling—a profession in search of itself. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 11, 187–191.

McCarthy Veach, P., LeRoy, B., & Bartels, D. M. (2003). Facilitating the genetic counseling process a practice manual. New York: Springer.

McCarthy Veach, P., Bartels, D. M., & LeRoy, B. S. (2007). Coming full circle: a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16, 713–728. doi:10.1007/s10897-007-9113-4.

McCarthy Veach, P., LeRoy, B., & Bartels, D. M. (2010). Genetic counseling practice: advanced concepts and skills. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Meiser, B., Irle, J., Lobb, E., & Barlow-Stewart, K. (2008). Assessment of the content and process of genetic counseling: a critical review of empirical studies. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 17, 434–451. doi:10.1007/s10897-008-9173-0.

Redlinger-Grosse, K. (2016). A different vantage point: commentary on 'Theories for Psychotherapeutic genetic counseling: fuzzy trace theory and cognitive behavior theory’. Journal of Genetic Counseling. Advance Online Publication: doi:10.1007/s10897-016-0024-0.

Redlinger-Grosse, K., Veach, P. M., Cohen, S., LeRoy, B. S., MacFarlane, I. M., & Zierhut, H. (2015). Defining our clinical practice: the identification of genetic counseling outcomes utilizing the reciprocal engagement model. Journal of Genetic Counseling. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9864-2.

Resta, R., Biesecker, B. B., Bennett, R. L., Blum, S., Estabrooks Hahn, S., Strecker, M. N., & Williams, J. L. (2006). A new definition of genetic counseling: national society of genetic counselors’ task force report. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 15, 77–83.

Rieh, J. P., & Ray, C. (1974). Conceptual models for nursing practice. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Roter, D., Ellington, L., Erby, L. H., Larson, S., & Dudley, W. (2006). The genetic counseling video project (GCVP): models of practice. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 142C, 209–220. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30094.

Weil, J. (2003). Psychosocial genetic counseling in the post-nondirective era: a point of view. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 12, 199–211.

Yager, G. G. (2014). Commentary on “Conceptualizing genetic counseling as psychotherapy in the era of genomic medicine”. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 23, 935–937. doi:10.1007/s10897-014-9734-3.

Acknowledgements

This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the first author’s Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Minnesota. The authors would like to thank Yu Huang, MA for her time and dedication in the qualitative coding process.

Dr. Christina Palmer served as Action Editor on the manuscript review process and publication decision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Krista Redlinger-Grosse, Patricia McCarthy Veach, Bonnie S. LeRoy, and Heather Zierhut declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota IRB. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Animal Studies

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

(DOCX 32.6 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Redlinger-Grosse, K., Veach, P.M., LeRoy, B.S. et al. Elaboration of the Reciprocal-Engagement Model of Genetic Counseling Practice: a Qualitative Investigation of Goals and Strategies. J Genet Counsel 26, 1372–1387 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0114-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0114-7