Abstract

While emotional abuse has effects on social anxiety, little is known about mechanisms of this relationship, particularly in China. To address this gap, this cross-sectional study estimated mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety in Chinese culture. 569 adolescents and pre-adolescents (aged between 10 and 15 years, M = 11.68, SD = 0.83; 50.62% boys) completed a series of questionnaires inquiring about emotional abuse, social anxiety, loneliness, and self-esteem. Structural equation modeling was used to examine mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety. The results revealed that emotional abuse was positively associated with social anxiety and loneliness (r = .36, .29, respectively, p < .01), while it was negatively associated with self-esteem (r = − .22, p < .01). Mediational models testing indirect effects through the bootstrapping method revealed that the total effect of emotional abuse on social anxiety was positive and significant; this effect was mediated by self-esteem and loneliness. Findings suggest that loneliness and self-esteem mediates the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety. Decreasing loneliness and increasing self-esteem should be applied in interventions to reduce social anxiety of emotionally abused Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Child maltreatment, as a world public health issue, has been discussed for several decades, while its international prevalence is still high. For example, estimates of child maltreatment indicated that nearly a quarter of adults (22.6%) worldwide suffered physical abuse as a child, and 36.3% experienced emotional abuse (World Health Organization 2014). Moreover, child maltreatment is a risk factor for maladaptation, and a growing body of research has verified the relationship between child maltreatment and internalizing problems (Ackner 2013; Schulz et al. 2014; Suzuki et al. 2015). Some studies have also revealed that emotional abuse is more likely to increase the risk of internalizing problems (such as social anxiety) than any other type of maltreatment (Bruce et al. 2012; Simon et al. 2009). However, the mechanisms linking emotional abuse with social anxiety are still unclear. One possible explanation may be self-experience (i.e., loneliness and self-esteem), influenced by experiencing emotional abuse (Arslan 2016; Brown et al. 2016). Although associations between loneliness, self-esteem, and social anxiety also have been verified by some studies (Abdollahi and Talib 2016; Cavanaugh and Buehler 2015; Iancua et al. 2015), few researches have explored the roles of loneliness and self-esteem in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents.

Based on developmental psychopathology perspectives and attachment theory, negative experiences in parent–child relationships may be risk factors for later maladaptation (Kim and Cicchetti 2004; Lim et al. 2016). Individuals who exposed to negative parent–child relationships may internalize these negative experiences into their perceptions of the self and others (Kim and Cicchetti 2004; Sroufe et al. 1999); furthermore, these distorted perceptions may lead to later maladaptation, including internalizing and externalizing problems (Babore et al. 2017; Lim et al. 2016). Similarly, emotional abuse, as one type of negative experiences in parent–child relationships, may lead to the individual having biased perceptions of self and interpersonal relationships (Riggs 2010). Guided by developmental psychopathology perspectives and attachment theory, we aim to explore the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety, and estimate the mediating roles of loneliness and self-esteem in this relationship among Chinese adolescents.

Emotional Abuse and Social Anxiety

Emotional abuse may be a serious public health issue in China for its high prevalence and risk outcomes. China is more conservative than Western countries, and Chinese parents’ emotional expression may be influenced by Chinese traditional culture (Chen et al. 2015). And emotional expression may influence on parent–child relationship, which may lead to high prevalence in China. The international prevalence of emotional abuse may be 36.30% (Stoltenborgh et al. 2012), while it may be higher in China. For example, a study based on 1041 Chinese adolescents indicated that the prevalence of emotional abuse was 51.40% (Suna et al. 2019). Moreover, emotional abuse may be one of the most prevalent types of maltreatment in China (Chen et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2006). In addition, emotional abuse may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders or mental problems, such as social anxiety (Ackner 2013; Calvete 2014; Jangam et al. 2015), which may influence on an individual’s daily life.

Social anxiety, a high risk mental problem among adolescents (rating from 27.2% to 42.0%; Li et al. 2015b; Pontillo et al. 2017), may influence on an individual’s well-being and daily life (Azad-marzabadi and Amiri 2017; Ciarma and Mathew 2017; Li et al. 2017). Social anxiety for its high incidence and serious outcomes has been discussed for several decades, while the risk factors are still unclear. Based on developmental psychopathology perspectives and attachment theory, early negative experiences or parenting may be risk factors for social anxiety (Bruce et al. 2012). Brumariu and Kerns (2008) suggested that individuals exposed to early negative experiences or parenting may have distorted internal working models about self and others, which may lead to social anxiety.

Moreover, emotional abuse, as one kind of early negative experiences, may be more likely to associate with social anxiety (Bruce et al. 2012; Nanda et al. 2016; Simon et al. 2009). Similarly, some studies indicated that emotional abuse was positively associated with social anxiety in different samples, including adolescents and adults (Bishop et al. 2014; González-Díez et al. 2016; He et al. 2008). However, some studies did not confirm these results (Binelli et al. 2012; Hamilton et al. 2013). To address these inconsistent results, we explored the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents. We hypothesize, therefore, that emotional abuse may be associated with social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents.

Mediators of Self-Esteem and Loneliness

Since different self-construal patterns may influence the ways of individuals’ think, perceive themselves, feel emotions, and act (Matsumoto 1999), Chinese people may have different perceptions of emotional abuse, as well as effects of emotional abuse on self-esteem and loneliness. Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) theory of self-construal builds on dimensional interpretation of individualism and collectivism, which suggests that people in individualistic societies prefer to have higher independent self-construals, whereas the opposite relationship is expected in collectivist societies. Although the self-construal theory relies on the unsupported assumption of cross-national distinction in individualism and collectivism (Matsumoto 1999), it may also give us some ideas about cross-national differences to understanding people’s behaviors. While China has historically been categorized as a collectivist society (Voronov and Singer 2002), some researchers reported that China could not be considered a pure collectivist society, or may be an exemplary synthesis of individualist and collectivist values (Ho and Chiu 1994). Therefore, self-esteem and loneliness in Chinese survivors of emotional abuse may be different from individuals with other self-construal patterns.

Self-esteem, a component of self, is individuals’ evaluation of their worth as a person based on an assessment of the qualities that make up the self-concept, which may be influenced by early experiences (Shaffer and Kipp 2010). Emotional abuse may have effects on self-esteem (Ma et al. 2011; Malik and Kaiser 2016). Individuals who were emotionally abused as a child may feel less self-worth and more hopelessness (Lamis et al. 2014), which may make them have biased evaluations towards themselves. Moreover, Malik and Kaiser (2016) suggested that survivors of emotional abuse may have a propensity to internalize parental statement as part of their own evaluation.

Meanwhile, exposed to emotional abuse may influence on the individual’s self-esteem, and the impaired self-esteem may be associated with later maladaptation, such as social anxiety. Some studies demonstrated that self-esteem was associated with social anxiety (Ma et al. 2014; Nordstrom et al. 2014). For example, Abdollahi and Talib (2016) reported that low self-esteem predicted high social anxiety among 520 college students. Moreover, self-esteem may be a mediator in the relationship between child maltreatment and later maladaptation (Jua and Lee 2018). For instance, Arslan (2016) suggested that self-esteem mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and emotional problems.

In addition, emotional abuse may be not only associated with self-esteem, but also be associated with loneliness. Loneliness is an enduring condition of emotional distress that arises when being estranged from, misunderstood, or rejected by others (Rook 1984). Previous studies have indicated that child maltreatment may be a risk factor for loneliness (Appleyard et al. 2010); most studies focused on the relationship between sexual abuse and loneliness (Gobson and Hartshorne 1996; Rew 2002). Emotional abuse, as one kind of child maltreatment, may be associated with loneliness. Survivors of emotional abuse may be influenced by negative experiences of parent–child interactions, and they may have distorted understanding about interpersonal relationships, including mistrust towards others (Liu et al. 2018a); these distorted understanding about interpersonal relationships may make individuals feel more social isolation and loneliness (Akdoğan 2017).

Meanwhile, loneliness may be associated with social anxiety among adolescents and adults (Cavanaugh and Buehler 2015). Individuals who feel more loneliness may be in fear of closing to others and get less support from others, which make them feel more anxiety (Cavanaugh and Buehler 2015). For example, a study based on 1070 adults reported that early loneliness predicted later social anxiety (Lim et al. 2016). In addition, some studies have indicated that loneliness mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and later negative outcomes (Appleyard et al. 2010). For instance, Shevlin et al. (2014) suggested that loneliness mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and adult psychopathology.

Although some studies have revealed some mediators in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety (e.g. resilience; Liang et al. 2019), few studies explored the mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness in this relationship. Moreover, the direction of pathway between self-esteem and loneliness is unclear (Yıldız and Karadaş 2017; Zhao et al. 2017). We hypothesize, thus, that self-esteem and loneliness may mediate the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety.

The Current Study

Although associations among emotional abuse, social anxiety, self-esteem and loneliness have been explored bivariately by extensive studies, the mechanisms of emotional abuse and social anxiety are still unclear. The aims of the present study are to (a) investigate the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety, and (b) explore the mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents. We hypothesize that emotional abuse is positively associated with social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents. Moreover, self-esteem and loneliness play the mediating roles in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety.

Method

Participants

580 participants of this study were recruited from two primary schools in Southeast China from April, 2015 to May, 2015, which were used to explored the mechanisms linking emotional abuse with social anxiety among adolescents and pre-adolescents. 11 (1.9%) of the questionnaires had missing data (more than 15%; Davey and Savla 2010), which were removed from the statistical analyses. Of 569 participants, 49.4% of them were girls (n = 281); the mean age was 11.68 years (SD = 0.83), with a range from 10 to 15 years. 25.8% of them (n = 147) were the only child in the family. Moreover, participants came from families with different incomes (Table 1).

Procedures

Firstly, the authors presented the aims and questionnaires to the headmasters of the two primary schools, and obtained permissions after discussing some details. Secondly, participants were randomly recruited from nine classes for each primary school. Thirdly, participants, teachers and caregivers were acknowledged about the research before data collection process. Fourthly, participants were presented with an informed consent attached at the beginning of the measure booklets, which informed them about the purposes of the study and ensured that their answers would only be used anonymously for research purposes. Lastly, participants completed questionnaires in their classrooms within 30 min, and they received a small gift worth ¥5 ($0.75). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the authors’ institution, and procedures of the present study were safety for participants.

Measures

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form (CTQ-SF). The CTQ–SF (Bernstein and Fink 1998; Bernstein et al. 2003) is a self-report screening tool which used to measure childhood abuse and neglect. The Chinese adaption of CTQ-SF was developed by Zhao et al. (2005) and this adaption has been deemed valid and reliable among adolescents (Li et al. 2016) and young adults (Tian et al. 2017). It has 5 subscales to assess 5 different types of child abuse and neglect, such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Each subscale is composed of 5 items, with a total of 28 items including a minimization-denial subscale of 3 items. Responses to items are via 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always), and high average score indicate high childhood maltreatment. The Chinese version of childhood emotional abuse (EA) subscale was only administered in the present study. The Cronbach’s alpha of it was .75 and the data were consistent with the original questionnaire’s constructs (RMSEA = .081, CFI = .952, TLI = .904) in the present study.

Social Anxiety Scale for Children (SASC). The SASC (La Greca et al. 1988) is a self-report measure to access social anxiety for children; 10 items belong to two factors: one is fear of negative evaluation (FNE), the other is social avoidance and distress (SAD). Internal consistency approach, an item parceling strategy, was used to ensure better model fit (Landis et al. 2000) when the questionnaire has confirmatory dimensionalities with making all items from the same dimensionality into one parcel (Kishton and Widaman 1994; Little et al. 2002). Thus, FNE and SAD were presented in SEM model according to item parceling. The Chinese adaption of SASC was developed by Ma (1993) and it has been deemed valid and reliable among children and adolescents (Bu et al. 2017). Responses to items are via 3-point Likert scale (from 0 = never to 2 = always), and high average scores indicate high social anxiety. The Chinese version of SASC was administered in the present study. The Cronbach alpha of it was .73, and data were consistent with the original questionnaire’s constructs (RMSEA = .055, CFI = .928, TLI = .905) in the present study.

Children’s Loneliness Scale (CLS). The CLS is a 16-item self-report scale which used to access the loneliness for children; 10 items for loneliness and 6 items for other things. It was developed by Asher et al. (1984), and the Chinese adaption of CLS was developed by Wang et al. (1999). Responses to items are via 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always); high average scores indicate high loneliness. The Chinese version of CLS was administered in the present study, and it has been deemed valid and reliable among children and adolescents (Liu et al. 2018b) and the Cronbach alpha of it was .82 in the present study. The constructs of data in the present study were consistent with original questionnaire (RMSEA = .080, CFI = .782, TLI = .749). According to item parceling (Landis et al. 2000), the scale was to broken into 4 parts, loneliness 1 (LO1), loneliness 2 (LO2), loneliness 3 (LO3) and loneliness 4 (LO4).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES). The SES is a self-report questionnaire used to collect data of self-esteem. It was developed by Rosenberg (1965) with 10 items. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = very conformity to 4 = very inconformity). Ratings were averaged to form a total score; high scores indicate high self-esteem (SE). And the Chinese version of SES was used in the present study and it has been deemed valid and reliable among children, adolescents and adults (Liu et al. 2018a; Ma et al. 2014). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale is .83 in China (Dai 2010), and it was .73 in the present study. Moreover, the constructs of data in the present study were consistent with original questionnaire (RMSEA = .086, CFI = .852, TLI = .803). Similarly, SES is a unidimensional scale, so item parceling strategy was used in SE to ensure better model fit in construct models (Wu and Wen 2011).

Data Analysis

Before the data analysis, normality, missing values, and outliers were examined and the questionnaires with missing data were excluded. Descriptive analyses included all variables of interest for the total sample. A Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between all variables using SPSS 21. All tests were two-tailed for significance, and significance (p value) was set at .05.

To further explore the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety, structural equation models (SEMs) were constructed by using AMOS 22. At first, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test whether measurement models were acceptable fits to the sample data or not. And then SEMs were performed with maximum likelihood estimation which require continuous data and multivariate normality, and the data collected by Likert scale could regard as that kind of data (Bian et al. 2007). The goodness of model fit was assessed using Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Fit indexes were the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). Moreover, the cutoff value close to .95 for CFI, TLI, and cut-off value close to .08 for RMSEA indicate a good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Moreover, Bias-corrected bootstrap was conducted (1000 samples) to test the mediating effect (Fang and Zhang 2012; Shrout and Bolger 2002). Both direct and indirect effects of emotional abuse on social anxiety were estimated, which generated percentile based on confidence intervals (CI). In addition, age, gender, and family income were controlled in SEMs with regard them as some other influenced variables to social anxiety.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Results of descriptive statistics and correlation analysis are presented in Table 2. As indicated, emotional abuse was positively associated with social anxiety (r = .36, p < .01), as well as loneliness (r = .29, p < .01), i. e., individuals who obtained high scores of emotional abuse had high levels of social anxiety and loneliness. Emotional abuse was negative associated with self-esteem (r = − .22, p < .01), which suggested that individuals who scored higher on emotional abuse had lower level of self-esteem.

Measurement Model

The measurement model of each questionnaire was first tested in the current study, and the measurement models appeared to fit the data. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form: RMSEA = .081, CFI = .952, TLI = .904; Social Anxiety Scale for Children: RMSEA = .055, CFI = .928, TLI = .905; Children’s Loneliness Scale: RMSEA = .080, CFI = .782, TLI = .749; Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: RMSEA = .086, CFI = .852, TLI = .803.

The Relationship Between Emotional Abuse and Social Anxiety

SEM was used to measure direct relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety. Results of SEM indicated that emotional abuse was positively associated with social anxiety (β = .53, SE = .12, p < .001), and emotional abuse accounted for 28% of the variance in social anxiety directly (R2 = .28). And the structural model provided a good fit to the data (RMSEA = .064, CFI = .948, and TLI = .917).

Self-Esteem and Loneliness Mediated the Relationship Between Emotional Abuse and Social Anxiety

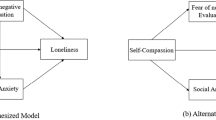

The CFA of all variables were done, and then SEM was used to investigate the hypothesized mediating effects of self-esteem and loneliness on the positively association between emotional abuse and social anxiety. Observe variables of fear of negative evaluation and social avoidance and distress were presented in final structural model, which had good model fits (RMSEA = .052, CFI = .964, TLI = .947). In addition, gender, age, and family income were controlled in the final structural model. Two separated final structural models (model A and B) were tested for there was uncertainty about the nature of the relationship between loneliness and self-esteem in the literature.

In the final structural model A (Fig. 1), the pathway was from self-esteem to loneliness. Emotional abuse was positively associated with loneliness (β = .25, 95% CI = [.129, .353], p < .001), while it was negatively associated with self-esteem (β = − .26, 95% CI = [−.361, −.174], p < .001). Loneliness was positively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = .40, 95% CI = [.301, .497], p < .001), while self-esteem was negatively associated with loneliness (β = − .41, 95% CI = [−.502, −.300], p < .001). Emotional abuse was positively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = .23, 95% CI = [.133, .327], p < .001) via loneliness alone and combination of self-esteem and loneliness; results of Bias-corrected method showed that 95% CI of indirect effects was [.076, .181], and 95% CI of direct effect was [.122, .361]. Thus, loneliness and self-esteem partially mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and fear of negative evaluation among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents.

Moreover, in the final structural model A (Fig. 1), self-esteem was negatively associated with social avoidance and distress (β = − .10, 95% CI = [−.199, .002], p < .01), and loneliness was positively associated with social avoidance and distress (β = .24, 95% CI = [.130, .350], p < .001). SEM results indicated that emotional abuse was indirectly associated with social avoidance and distress (β = .21, 95% CI = [.116, .305], p < .001) via self-esteem and loneliness. And results of Bias-corrected method showed that 95% CI of indirect effects was [.104, .261], and 95% CI of direct effect was [.136, .354]. Thus, loneliness and self-esteem partially mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and social avoidance and distress among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents. Therefore, self-esteem and loneliness mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety.

Emotional abuse accounted for 7.0% of the variance in self-esteem and 28% of the variance in loneliness. Together, emotional abuse, self-esteem and loneliness accounted for 30% of the variance in fear of negative evaluation and 18% of the variance in social avoidance and distress.

In the final structural model B (Fig. 2), the pathway was from loneliness to self-esteem. And results of Bias-corrected method were the same as model A. Moreover, emotional abuse accounted for 23% of the variance in self-esteem and 13% of the variance in loneliness. Together, emotional abuse, self-esteem and loneliness accounted for 30% of the variance in fear of negative evaluation and 18% of the variance in social avoidance and distress. In addition, model with separated fear of negative evaluation and social avoidance and distress components of social anxiety was also analyzed. But the model fits of it were not very good (RMSEA = .053, CFI = .894, TLI = .875).

Since the data was not longitudinal, some alternative models were tested in the current study. An alternative model which social anxiety mediated the association between emotional abuse and self-esteem, however, the model fits were not good (RMSEA = .057, CFI = .804, TLI = .781). Results indicated that emotional abuse was negatively associated with self-esteem (β = −.05, 95% CI = [−.251, .187], p > .05); self-esteem was negatively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = −.25, 95% CI = [−.409, −.084], p < .05), as well as social avoidance and distress (β = −.26, 95% CI = [−.573, .017], p < .05); emotional abuse was positively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = .52, 95% CI = [.386, .647], p < .05), as well as social avoidance and distress (β = .56, 95% CI = [.575, .416], p < .05). Moreover, another alternative model, which social anxiety mediated the association between emotional abuse and loneliness, was tested in the current study. Results indicated that the model fits were not good (RMSEA = .060, CFI = .751, TLI = .731).

Discussion

We verified the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents, and explored the mediating roles of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety. These findings give evidences for the assumptions based on developmental psychopathology perspectives that adverse childhood experiences may lead to individuals’ later maladaptation.

Results of present study were consistent with previous studies indicating that emotional abuse were associated with self-esteem and loneliness (Brown et al. 2016; Malik and Kaiser 2016), as well as social anxiety (Bruce et al. 2012; Bu et al. 2017). Emotional abuse may contribute to a sense of self as unworthy, resulting in lower self-evaluation. For example, a study of 150 youths indicated that child abuse negatively predicted self-esteem, suggesting that child abuse was a risk factor for the development of self-esteem (Dang 2014). Moreover, a prospective study with 1354 children suggested that child abuse significantly predicted later loneliness (Appleyard et al. 2010). In addition, some studies showed that emotional abuse was positively associated with social anxiety (Iffland et al. 2012). Hamilton et al.’ (2013) cross-sectional study with 225 adolescents in which emotional abuse predicted individuals’ social anxiety. These findings support the assumptions of developmental psychopathology perspectives and attachment theory.

Moreover, the present study also found that self-esteem and loneliness partially mediated relationships between emotional abuse and social anxiety. These results showed that self-esteem and loneliness were contributed to different outcomes (Rosenberg and Rosenberg 1978), including internalizing problems (i.e., social anxiety). Meanwhile, the result of the mediating role of self-esteem was consistent with Arslan’s (2016) cross-sectional study of adolescents, suggesting that self-esteem play a role in the relationship between emotional abuse and emotional problems. Gregera and colleagues (Gregera et al. 2017) also confirmed the mediating role of self-esteem between child maltreatment and psychopathology among adolescents and early adults, suggesting that self-esteem play a role in childhood maltreatment’s long-term effects on emotional problems. These findings indicated that individuals with high levels of self-esteem may have more positive evaluations of self, which may give them more self-efficiency to overcome adversity, and partially break the pathway from emotional abuse to social anxiety.

Meanwhile, loneliness as a mediator in the association between emotional abuse and social anxiety was confirmed in the present study. These findings were consistent with previous studies, suggested that loneliness was a mediator between child maltreatment and negative outcomes, such as physical sub-health (Li et al. 2015a), and aggression (Sun et al. 2017). Moreover, these findings suggest that individuals with low levels of loneliness may obtain more support from others and more likely to utilize their support systems, which may partially break the pathway from emotional abuse to social anxiety.

In addition, the results showed that self-esteem and loneliness were associated with each other, which consistent with previous studies (Dhal et al. 2007; Yıldız and Karadaş 2017). Moreover, a prospective study by Vanhalst et al. (2013) based on adolescents suggested that self-esteem predicted later loneliness, and the second time loneliness predicted later self-esteem. Although the result of the current study based on cross-sectional data, it still could give us information about the association between self-esteem and loneliness. The implications of these findings are significant, underscoring the role of self-esteem and loneliness involved in maltreated children’s adjustment and pointing to potentially modifiable mechanisms.

Implications

The results of this research may help understand relationships between emotional abuse and social anxiety, and how emotional abuse influences on social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents. One of the implications of the study is that it may help people know more negative outcomes of emotional abuse among Chinese primary students, and improve awareness of preventing emotional abuse in China, which may decrease prevalence of emotional abuse and implement more interventions to prevent it. Secondly, the study may be helpful for survivors of emotional abuse. For example, we can implement some projects to decrease the levels of loneliness and increase levels of self-esteem for reducing social anxiety of individuals who were emotionally abused.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. Firstly, self-report scales were used to measure all variables, which may decrease the accuracy of information. So, future research should collect data using several sources (e.g., peers, parents, and teachers) to increase the accuracy of the information. Secondly, cross-sectional design was used to examine relationships between emotional abuse and social anxiety, and results may not so convince. Moreover, results of cross-sectional study may not give us the causal mechanisms between emotional abuse and social anxiety, which may have less convince of understanding relationships among variables. In addition, cross-sectional design may give us less information about the variables which may lead us misunderstanding the relationships among variables. So, longitudinal studies should be conducted to confirm these results in future studies. Thirdly, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used to access the explicit self-esteem, but the implicit self-esteem may be more accurate to display the individuals’ real thinking. Therefore, future study should pay attention to compare the roles of different kinds of self-esteem in the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the association between emotional abuse and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents in this data. In line with our predictions, emotional abuse was positively correlated with social anxiety among adolescents and pre-adolescents. Using the SEM, we demonstrated that loneliness and self-esteem mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and social anxiety. Findings suggest that emotional abuse not only have a direct relationship with individuals’ social anxiety, but also have an indirect relationship with individuals’ social anxiety via loneliness and self-esteem. Decreasing the levels of loneliness and increasing the levels of self-esteem should be applied in interventions to reduce social anxiety of emotionally abused Chinese adolescents and pre-adolescents.

References

Abdollahi, A., & Talib, M. A. (2016). Self-esteem, body-esteem, emotional intelligence, and social anxiety in a college sample: The moderating role of weight. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 21(2), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2015.1017825.

Ackner, S. (2013). Emotional abuse and psychosis: A recent review of the literature. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 22, 1032–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.837132.

Akdoğan, R. (2017). A model proposal on the relationships between loneliness, insecure attachment, and inferiority feelings. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.048.

Appleyard, K., Yang, C., & Runyan, D. K. (2010). Delineating the maladaptive pathways of child maltreatment: A mediated moderation analysis of the roles of self-perception and social support. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941000009X.

Arslan, G. (2016). Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.010.

Asher, S. R., Hymel, S., & Renshaw, P. D. (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55(4), 1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00565.x.

Azad-marzabadi, E., & Amiri, S. (2017). Morningness-eveningness and emotion dysregulation incremental validity in predicting social anxiety dimensions. International Journal of General Medicine, 10, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S144376.

Babore, A., Carlucci, L., Cataldi, F., Phares, V., & Trumello, C. (2017). Aggressive behavior in adolescence: Links with self-esteem and parental emotional availability. Social Development, 26(4), 740–752.

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169–190.

Bian, R., Che, H., & Yang, H. (2007). Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Advances in Psychological Science, 15(3), 567–576.

Binelli, C., Ortiz, A., Muñiz, A., Gelabert, E., Ferraz, L., Filho, A. S., et al. (2012). Social anxiety and negative early life events in university students. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 34(Supl1), S69–S80.

Bishop, M., Rosenstein, D., Bakelaar, S., & Seedat, S. (2014). An analysis of early developmental trauma in social anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annals of General Psychiatry, 13(16), 1–14 http://www.annalsgeneralpsychiatry.com/content/13/1/16.

Brown, S., Fite, P. J., Stone, K., & Bortolato, M. (2016). Accounting for the associations between child maltreatment and internalizing problems: The role of alexithymia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.008.

Bruce, L. C., Heimberg, R. G., Blanco, C., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and social anxiety disorder: Implications for symptom severity and response to phamacotherapy. Depression and Anxiety, 29(2), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20909.

Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2008). Mother-child attachment and social anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Develop Psychology, 29(5), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.06.002.

Bu, Y., Chen, L., Guo, H., & Lin, D. (2017). Emotional abuse and children’s social anxiety: Mediating of basic psychological needs and self-esteem. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(2), 203–207.

Calvete, E. (2014). Emotional abuse as a predictor of early maladaptive schemas in adolescents: Contributions to the development of depressive and social anxiety symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.014.

Cavanaugh, A. M., & Buehler, C. (2015). Adolescent loneliness and social anxiety: The role of multiple sources of support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514567837.

Chen, S. H., Zhou, Q., Main, A., & Lee, E. H. (2015). Chinese American immigrant parents’ emotional expression in the family: Relations with parents’ cultural orientations and children’s emotion-related regulation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000013.

Chen, Y., Liu, X., Huang, Y., Yu, H., Yuan, S., Ye, Y., et al. (2017). Association between child abuse and health risk behaviors among Chinese college students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1380–1387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0659-y.

Ciarma, J. L., & Mathew, J. M. (2017). Social anxiety and disordered eating: The influence of stress reactivity and self-esteem. Eating Behaviors, 26, 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.03.011.

Dai, X. (2010). Handbook of mental assessment scales. Beijing: People’s Military Medical Press.

Dang, M. T. (2014). Social connectedness and self-esteem: Predictors of resilience in mental health among maltreated homeless youth. Mental Health Nursing, 35, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.860647.

Davey, A., & Savla, J. (2010). Statistical power analysis with missing data: A structural equation modeling approach. New York: Taylor and Francis Group.

Dhal, A., Bhatia, S., Sharma, V., & Gupta, P. (2007). Adolescent self-esteem, attachment and loneliness. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 3(3), 61–63.

Fang, J., & Zhang, M. (2012). Assessing point and interval estimation for the mediating effect: Distribution of the product, nonparametric bootstrap and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(10), 1408–1420. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.01408.

Gobson, R. L., & Hartshorne, T. S. (1996). Childhood sexual abuse and adult loneliness and network orientation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(11), 1087–1093.

González-Díez, Z., Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2016). The role of emotional maltreatment and looming cognitive style in the development of social anxiety symptoms in late adolescents. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1188920.

Gregera, H. K., Myhrec, A. K., Klöcknere, C. A., & Jozefiak, T. (2017). Childhood maltreatment, psychopathology and well-being: The mediator role of global self-esteem, attachment difficulties and substance use. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.012.

Hamilton, J. L., Shapero, B. G., Stange, J. P., Hamlat, E. J., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2013). Emotional maltreatment, peer victimization, and depressive versus anxiety symptoms during adolescence: Hopelessness as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(3), 332–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.777916.

He, Q., Pan, R., & Meng, X. (2008). Relationship of social anxiety disorder and child abuse and trauma. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 40–42. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2008.01.013.

Ho, D. Y. F., & Chiu, C. Y. (1994). Component ideas of individualism, collectivism, and social organization: An application in the study of Chinese culture. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S.-C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 137–156). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Huang, Q., Zhao, X., Lin, H., Liu, Y., Yin, Z., Zhou, Y., & Li, L. (2006). Childhood maltreat: An investigation among the 335 senior high school students. China Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 97–99. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2006.01.039.

Iancua, I., Bodnerb, E., & Ben-Zion, I. Z. (2015). Self-esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.018.

Iffland, B., Sansen, L. M., Catani, C., & Neuner, F. (2012). Emotional but not physical maltreatment is independently related to psychopathology in subjects with various degrees of social anxiety: A web-based internet survey. BMC Psychiatry, 12(49), 1–8 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/12/49.

Jangam, K., Muralidharan, K., Tansa, K. A., Raj, E. A., & Bhowmick, P. (2015). Incidence of childhood abuse among women with psychiatric disorders compared with healthy women: Data from a tertiary care center in India. Child Abuse & Neglect, 50, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.017.

Jua, S., & Lee, Y. (2018). Developmental trajectories and longitudinal mediation effects of self-esteem, peer attachment, child maltreatment and depression on early adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.015.

Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2004). A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother–child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 341–354 http://dx.doi.org/0091-0627/04/0800-0341/0.

Kishton, J. M., & Widaman, K. F. (1994). Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54, 757–765.

La Greca, A. M., Dandes, S. K., Wick, P., Shaw, K., & Stone, W. L. (1988). Development of the social anxiety scale for children: Reliability and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 17(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1701_11.

Lamis, D. A., Wilson, C. K., Shahane, A. A., & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Mediators of the childhood emotional abuse–hopelessness association in African American women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1341–1350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.006.

Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Behavioral Research, 3, 186–207.

Li, H., Gu, X., Tang, J., Wan, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2015a). Effects of loneliness on the relation between childhood abuse and physical sub-health among middle school students in Bengbu. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 23(1), 24–27.

Li, J., Wei, X., Huang, Y., Li, Y., & Liu, H. (2015b). Relationships among the interpersonal trust in college dormitory self-esteem and interaction anxiety. Chinese. Journal of School Health, 36(8), 1173–1176. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2015.08.020.

Li, Y., Lin, X., Hou, X., Fang, X., & Liu, Y. (2016). The association of child maltreatment and migrant children’s oppositional defiant symptoms: The role of parent–child relationship. Psychological Development and Education, 32(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.01.12.

Li, Z., Wang, T., Liang, Y., & Wang, M. (2017). The relationship between mobile phone addiction and subjective well-being in college students: The mediating effect of social anxiety. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 15(4), 562–568.

Liang, L., Zhang, S., & Wu, Z. (2019). Relationship among social anxiety, emotional maltreatment and resilience in rural college students with left-behind experience. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 33(1), 64–69.

Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Gleeson, J. F. M., & Zyphur, M. J. (2016). Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000162.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173.

Liu, C., Chen, X., Song, P., Lu, A., Wang, L., Zhang, X., et al. (2018a). Relationship between childhood emotional abuse and self-esteem: A dual mediation model of attachment. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(5), 793–800. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6655.

Liu, G., Zhang, D., Luo, S., & Fang, L. (2018b). Loneliness and parental emotional warmth and problem behavior in children aged 8–12. Journal of Chinese Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 586–589. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.036.

Ma, H. (1993). Social anxiety scale for children. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 7(S), 216–217.

Ma, M., Chen, W., & Huang, Z. (2011). The relationship among depression, emotional maltreatment and self-esteem in junior school freshmen. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 25(1), 71–73.

Ma, Z., Liang, J., Zeng, W., Jiang, S., & Liu, T. (2014). The relationship between self-esteem and loneliness: Does social anxiety matter? International Journal of Psychological Studies, 6(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v6n2p151.

Malik, S., & Kaiser, A. (2016). Impact of emotional maltreatment on self-esteem among adolescents. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 66(7), 795–799.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

Matsumoto, D. (1999). Culture and self: An empirical assessment of Markus and Kitayama’s theory of independent and interdependent self-construals. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 289–310.

Nanda, M. M., Reichert, E., Jones, U. J., & Flannery-Schroeder, E. (2016). Childhood maltreatment and symptoms of social anxiety: Exploring the role of emotional abuse, neglect, and cumulative trauma. Journal of Child & Adolescent, Trauma, 9, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0070-z.

Nordstrom, A. H., Swenson Goguen, L. M., & Hiester, M. (2014). The effect of social anxiety and self-esteem on college adjustment, academics, and retention. Journal of College Counseling, 17(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00047.x.

Pontillo, M., Guerrera, S., Santonastaso, O., Tata, M. C., Averna, R., Vicari, S., & Armando, M. (2017). An overview of recent findings on social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults at clinical high risk for psychosis. Brain Sciences, 7(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7100127.

Rew, L. (2002). Relationships of sexual abuse, connectedness, and loneliness to perceived well-being in homeless youth. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 7(2), 51–63.

Riggs. (2010). Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: What theory and research tell us. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(1), 5–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770903475968.

Rook, K. S. (1984). Research on social support, loneliness, and social isolation: Toward an integration. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 239–264.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, F. R., & Rosenberg, M. (1978). Self-esteem and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 7, 279–294.

Schulz, A., Becker, M., Auwera, S. V., Barnow, S., Appel, K., Mahler, J., et al. (2014). The impact of childhood trauma on depression: Does resilience matter? Population-based results from the study of health in Pomerania. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 77, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.06.008.

Shaffer, D. R., & Kipp, K. (2010). Developmental psychology: Childhood and adolescence (8th ed.). Belmont: Cengage Learning.

Shevlin, M., McElroy, E., & Murphy, J. (2014). Loneliness mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and adult psychopathology: Evidence from the adult psychiatric morbidity survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 591–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0951-8.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

Simon, N. M., Herlands, N. N., Marks, E. H., Mancini, C., Letamendi, A., Li, Z., et al. (2009). Childhood maltreatment linked to greater symptom severity and poorer quality of life and function in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 26, 1027–1032. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20604.

Sroufe, L. A., Carlson, E. A., Levy, A. K., & Egeland, B. (1999). Implications of attachment theory for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 1–13.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Krsnenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R. A., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2012). The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 21, 870–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2012.708014.

Sun, L., Heng, S., Niu, G., Li, J., Du, H., & Hu, X. (2017). Association between childhood psychological abuse and aggressive behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of the security and loneliness. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(2), 902–906.

Suna, J., Liu, Q., & Yu, S. (2019). Child neglect, psychological abuse and smartphone addiction among Chinese adolescents: The roles of emotional intelligence and coping style. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.032.

Suzuki, A., Poon, L., Kumari, V., & Cleare, A. J. (2015). Fear biases in emotional face processing following childhood trauma as a marker of resilience and vulnerability to depression. Child Maltreatment, 20(4), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559515600781.

Tian, Z., Liu, A., & Li, J. (2017). Mediating effect of belief in a just world and self-esteem on relationship between childhood abuse and subjective well-being in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 31(4), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2017.04.011.

Vanhalst, J., Luyckx, K., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Goossens, L. (2013). Low self-esteem as a risk factor for loneliness in adolescence: Perceived – But not actual – Social acceptance as an underlying mechanism. Journal of Abnormal Children Psychology, 41, 1067–1081.

Voronov, M., & Singer, J. A. (2002). The myth of individualism-collectivism: A critical review. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(4), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540209603912.

Wang, X., Wang, X., & Ma, H. (1999). Manual of assessment of mental health scale. Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Journal.

World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on violence prevention. Retrieved August 19, 2019, from https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/en/

Wu, Y., & Wen, Z. (2011). Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(12), 1859–1867. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2011.01859.

Yıldız, M. A., & Karadaş, C. (2017). Multiple mediation of self-esteem and perceived social support in the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(3), 130–139.

Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., & Li, L. (2005). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 20(9), 105–107.

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., & Ran, G. (2017). Positive coping style as a mediator between older adults’ self-esteem and loneliness. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(10), 1619–1628. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6486.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Qin, J. Emotional Abuse and Adolescents’ Social Anxiety: the Roles of Self-Esteem and Loneliness. J Fam Viol 35, 497–507 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00099-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00099-3