Abstract

Long-term survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) are in a unique position to offer guidance and support to new survivors in a way that not only reflects their own experiences, but also the learned experience. The purpose of the present study was to examine IPV survivors’ messages of encouragement, advice, and hope for individuals who had recently left abusive relationships. The researchers utilized content analysis procedures to analyze participants’ (N = 263) responses to an open-ended question that was part of two larger mixed-methods studies. The research question was: What messages do long-term survivors of IPV want to send individuals who have recently left an abusive relationship? Findings illustrated participants’ messages to new survivors and were categorized into the following themes: (a) self-love and inherent strengths, (b) healing as a journey and process, (c) importance of social support, (d) leaving the abusive relationship behind, (e) focus on self-care, (f) guidance for new relationships, (g) practical issues and resources, (h) recommendations about children, (i) religious and spiritual messages, (j) obtaining education about IPV, and (k) advocacy and social action. This study filled a void in the literature and included the voices of survivors as contributors to the healing process of IPV. The findings illuminated clear themes that can be further explored and integrated into treatment approaches to assist individuals who have recently left abusive relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health issue defined as “physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, 2014, paragraph 1). Though leaving an IPV relationship is frequently understood as a one-time occurrence, it is a multi-faceted process that occurs over time (Khaw and Hardesty 2007; Patzel 2001) and continues post-IPV. The trauma effects following IPV are well-documented in the literature and include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Bergman and Brismar 1991), depression (Mechanic et al. 2008), substance abuse (Kaysen et al. 2007), negative financial consequences (Voth Schrag 2015), housing instability (Sullivan et al. 2018); negative physical and mental health outcomes (e.g., Coker et al. 2002), and social stigma (Murray et al. 2015a). Scholarship on IPV recovery and post-traumatic growth has also increased in the past several decades, highlighting the strengths of survivors and the prosperous lives they are able to establish following abuse (Ai and Park 2005; Allen and Wozniak 2011; Anderson et al. 2012; Baly 2010; Davis and Taylor 2006; Evans and Lindsay 2008; Flasch et al. 2015, 2019).

In this present study, we hoped to hear survivors’ own voices in terms of the messages they hoped to share with those who had recently left abusive relationships. Recommendations and advice for others provides a missing piece that may not be adequately uncovered by solely examining personal experiences. Other researchers have explored trauma survivors’ advice and recommendations for policy (Cerulli et al. 2015) and for service providers (Gagnon et al. 2018) and have found these perspectives to hold unique value. We wanted to use such as lens to better understand the advice and messages to other survivors. That is, being further along in the recovery process, what messages did our participants have for individuals who had recently left IPV relationships? This question was unique in that it did not ask for survivors’ own experiences, but rather for the culmination of meaning and lessons learned.

One aspect that has garnered increasing attention in the trauma recovery literature is the role of clients in advocacy and social justice efforts (Morgan and Coombes 2013; Flasch et al. 2015; Murray et al. 2015b; Ratts and Hutchins 2009). That is, when survivors engage in advocacy both for themselves and for others, they experience empowerment and meaning, which is healing and facilitates growth (Murray et al. 2015a, b; Flasch et al. 2015; Ratts and Hutchins 2009). On the receiving end, utilizing survivors’ perspectives honors their experiences and provides unique learning opportunities and insight for others in similar situations. Helping others has been a theme in many qualitative studies on the recovery process of survivors of IPV (e.g., Hou et al. 2013; Flasch et al. 2015, 2019; Murray et al. 2015b). Indeed, survivors have helped others by serving as advocates in the community and aiding in the creation of therapeutic approaches by taking part in research studies. This present study was another avenue for survivors to support new survivors. The current study was part of two larger studies that examined the stigma and recovery experiences following IPV. The focus of the investigation was to examine the specific messages of encouragement and advice from 263 participants (long-term IPV survivors) to new survivors. It is our hope that these messages add to the IPV recovery literature by infusing the voices of survivors in a way that has not yet been explored.

Recovery Experiences of Survivors of IPV

Though scholarship on trauma effects from IPV is well-documented, less attention has been paid to the healing experiences that facilitate IPV recovery and post-traumatic growth, though such literature is increasing. Recovery from IPV is a unique form of trauma recovery due to its intimate, complex, and chronic nature. In describing recovery from IPV, scholars have suggested varying definitions. Farrell (1996) described this process as “a multidimensional phenomenon consisting of physical, mental, and spiritual components… [that involves] … reconnecting the fragments of the self by putting into perspective the past experiences of abuse” (p. 31). Evans and Lindsay (2008) described it as integration rather than recovery, arguing that recovery from IPV is unlikely and even undesired. Further, Lewis and Watts (2015) named the recovery phase piece by piece based on survivors’ descriptions of taking one step at a time. Better understanding the process of recovering from IPV grounds the present study and helps provide context for participants’ messages to other survivors.

IPV Recovery as an Ongoing Process

In one study, Abrahams (2007) found that survivors of IPV progressed through a process similar to bereavement. Survivors initially encountered reception, in which they experienced denial and numbness; they then progressed to recognition, during which they dealt with feelings of anger and frustration and began to recognize and accept their experiences. Finally, in the reinvestment stage, survivors became more connected to the community and began to partake and reengage in life. Other researchers (e.g., Smith 2003; Wuest and Merritt-Gray 2001) have suggested similar developmental processes, in which survivors acknowledged their IPV experiences, dealt with struggles and challenges of the after-effects of IPV, and eventually managed to reconstruct themselves and heal. Still, researchers (e.g., Flasch et al. 2015) have found that the process of recovering from IPV is circular and interweaving, rather than linear. That is, survivors may progress through certain benchmarks of recovery, but specific events and triggers may catapult them back to earlier stages, where they may have to reconcile with unfinished business. Flasch et al. (2015) found that survivors’ recovery experiences rarely met a prescribed timeline, but, rather, intersecting experiences and growth moments served to piece together survivors’ growth and identities in a circular non-linear progression over time. Moreover, Davis and Taylor’s (2006) findings suggested that survivors experienced inner (i.e., journey with self) and outer (i.e., journey with others) processes within which were specific elements for recovery. This theme was echoed in Flasch et al. (2015) qualitative study of 123 survivors of IPV where the researchers found that survivors of IPV vacillated between simultaneous internal (e.g., recreating one’s identity) and external (e.g., building positive social supports) processes throughout their recovery experience. Though recovery from IPV is an individual and personal journey depending on a multitude of factors, it may be helpful to view it as an ongoing process contextualized in social and personal factors.

Social Support and Resources

Scholars have identified factors that affect the recovery process and may make healing more or less challenging. Such factors include social support, access to resources (both personal, social, and financial), resiliency, and the extent of abuse (Song 2012). For example, the recovery process of a survivor who has access to financial and social support (e.g., ability to pay for counseling or temporarily move in with a friend or family) may look different from a survivor who does not have those resources and who is unable to tend to psychological and practical needs (Patzel 2001; Sullivan et al. 2018; Voth Schrag 2015). Other factors that affect the recovery process include the extent of emotional and physical abuse. For example, mental and physical health needs may be more severe for some survivors, delaying their recovery (Coker et al. 2002; Mechanic et al. 2008).

Dumitrescu (2018) further emphasized the central role personal and community resources played in promoting departures from abusive relationships and mitigating the effects of IPV. That is, a culmination of factors (e.g., spirituality, hope, self-education, positive self-help, confidence, and social one) facilitated a survivor’s successful leaving, while fostering resilience. One of the most significant of these factors was social support, wherein inadequacies were highly influential in an individual’s decision to stay rather than leave the abusive relationship (Estrellado and Loh 2013; Zapor et al. 2015). Social support has also been found to be a mediating force between the negative effects of abuse and psychological well-being (Beeble et al. 2009). Community resources are often the hardest to acquire, and with the most barriers (Dumitrescu 2018), yet sourcing practical, legal, and financial support for individuals as they leave relationships is essential in maintaining an individual’s safety and independence (Bostock et al. 2009). Thus, recovery from IPV is comprised of unique processes and factors, all which influence the progression of healing.

Though we are beginning to better understand the complex process post-IPV, no study to date has explored what messages, advice, and words of encouragement long-term survivors of IPV may have for individuals who have just left abusive relationships. Long-term survivors of IPV are in a unique position to offer guidance and support to new survivors in a way that not only reflects their own experiences, but also includes the aspects they wished had been different or present in their own journeys, the lessons learned, and their hope for others. Such elements may be missed by solely asking about participants’ lived experiences. Therefore, this study aimed to add to the literature by better understanding messages of support and guidance from long-term survivors. Our research question asked, what messages do long-term survivors of IPV want to send individuals who have recently left an abusive relationship?

Methods

The present study was part of two larger studies that examined stigma and recovery experiences of survivors’ of IPV. The data set analyzed for this article was qualitative and derived from one specific open-ended question inquiring about messages by survivors of IPV to new survivors who had recently left IPV relationships. In both larger studies, the inclusion criteria were the same, the recruitment processes were the same, and the open-ended question under investigation was asked identically. Because the participants did not differ, it made sense to combine answers from both studies in order to achieve a larger sample.

Procedure and Recruitment

The original two studies from which the data for the current study were derived used a mixed methods research design to explore the role of stigma faced by survivors of IPV and to better understand IPV recovery. Both studies were approved by the researchers’ universities’ Institutional Review Boards (IRB). In the larger studies, the researchers recruited participants at the national level by posting study invitations to e-mail distribution lists (e.g., counseling and therapy-related), posting invitations on domestic violence and therapy-related social media platforms, and utilizing snowball sampling by e-mailing personal and professional community contacts and agencies to distribute recruitment e-mails and study invitations to potential participants. The participants met the following inclusion criteria: (a) they were at least 21 years of age, (b) they had previously experienced intimate partner violence, (c) they had been out of their most recent abusive relationship for at least two years, and (d) they spoke and could understand English. Participants who consented to participate completed an electronic survey created by the researchers using Qualtrics.

The survey for one study included a demographic section, questions about previous IPV experiences, questions about experienced stigma, questions related to overcoming stigma, and the open-ended question, “What message would you want to send to people who have recently left an abusive relationship?” The survey for the second study included a demographic questionnaire, questions about previous IPV experience, and several open-ended question asking participants about their recovery experiences post-IPV, including the question, “What message would you want to send to people who have recently left an abusive relationship?” The open-ended question asked in both larger studies was the focus of the current study. As an incentive for participation, the researchers held two drawings of $50 store gift-cards. Participants who were interested in participating in the drawing provided their contact information separate from their responses in order to maintain the anonymity of the survey responses.

We used content analysis methodology (Stemler 2001) to examine themes in participants’ messages to individuals who had recently left abusive relationships. Content analysis is defined as “any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages” (Holsti 1969, p. 14). Further, content analysis procedures allow researchers to sift through large amounts of data in a systematic fashion (GAO 1996). Since we had a large volume of narrative qualitative data from two larger studies, content analysis was an appropriate choice of methodology for this study.

Participants

The original two studies included 562 participants. For the present study, we only retained participants who had responded to the open-ended question about messages to new survivors. After removing unanswered responses, 263 participants remained. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 82 years (M = 40.82; SD = 12.59; Mdn = 39). There were 232 female participants (88.21%), 26 male participants (9.89%), 1 gender-fluid participant (0.38%), and 4 participants who did not list their gender (1.52%). Participants’ ethnicities included Caucasian/White (n = 208; 79%), Hispanic/Latinx (n = 17; 6.46%), African American/Black (n = 14; 5.32%), Mixed/Multiple ethnicities (n = 14; 5.32%), Asian (n = 4; 1.52%), and not reported (n = 6; 2.28%). Out of the participants, the majority had children (n = 157; 59.70%). Education level varied between High School Diploma/GED (n = 77; 29.28%), Bachelor’s Degree (n = 64; 24.30%), Associates Degree (n = 55; 20.91%), Graduate Degree (n = 38; 14.45%), Other (n = 16; 6.08%), and not reported (n = 3; 1.40%). Household income for participants was under $30,000 (n = 106; 40.30%), $30,000–$59,000 (n = 59; 22.43%), $60,000–$100,000 (n = 29; 11.03%), over $100,000 (n = 66; 25.10%), and not reported (n = 3; 1.40%). Participants’ current relationship status included single (n = 64; 24.33%), married (n = 63; 23.95%), in a committed relationship and living together (n = 58; 22.05%), divorced (n = 40; 15.21%), separated (n = 20; 7.60%), dating (n = 12; 4.56%), in a legally-recognized civil union (n = 4; 1.52%), and not reported (n = 2; 0.76%).

In terms of IPV history, participants’ abusive relationships lasted between 2 months and 46 years (Mdn = 5 years, 10 months). Participants had been out of their most recent abusive relationship between 2 and 39 years (Mdn = 6 years, 0 months). The most common number of abusive relationships that participants had experienced in their lifetime was 1 abusive relationship (n = 116; 44.12%), followed by 2 abusive relationships (n = 85; 32%), 3 abusive relationships (n = 31; 11.79%), more than 3 abusive relationships (n = 20; 7.60%), and not reported (n = 11; 4.18%). In their abusive relationships, nearly all participants had experienced emotional and verbal abuse (n = 259; 98.48%); the vast majority had experienced physical abuse (n = 213; 80.99%), and more than half had experienced sexual abuse (n = 169; 64.26%). Nearly all of the abusive partners were of a different sex than the victim (n = 253; 96.20%).

Data Analysis

Answers to the open-ended question, “What message would you want to send to people who have recently left an abusive relationship?” were extracted from the two original studies and compiled in a separate excel document by the lead researcher. The research team used an emergent coding strategy (Haney et al. 1998) and followed Stemler’s (2001) content analysis procedures for analyzing the data. First, the lead researcher reviewed the data and created an initial list of themes and categories. Second, a team of four researchers used the initial coding scheme to engage in a trial coding of 10 participant statements. The researchers defined a statement as a sentence or multiple sentences pertaining to the same topic or idea. For instance, one participant response could include several statements (e.g., a response about staying strong and getting mental health care was identified as two separate topics, or statements, and would thus receive two separate codes). The lead researcher split up participant responses into statements and identified 664 separate statements. The lead researcher used feedback from the trial coding to compile a final list of codes. The final coding scheme included 11 primary categories: (a) self-love and inherent strengths, (b) healing as a journey and process, (c) importance of social support, (d) leaving the abusive relationship behind, (e) focus on self-care (f) guidance for new relationships, (g) practical issues and resources, (h) recommendations about children, (i) religious and spiritual messages, (j) obtaining education about IPV, and (k) advocacy and social action. Additionally, other and no code were included as options for coding. Within each primary category, several sub-categories were listed. Four researchers independently coded the full set of data using primary and secondary codes. To increase trustworthiness, each statement was coded by two separate researchers. A third researcher then coded statements for which the initial two researchers did not reach agreement in either the primary or secondary coding categories.

To determine interrater reliability (IRR), we used Miles and Huberman’s (1994) procedures. We added the total number of agreements between researchers for both primary and secondary codes and divided it by the total number of statements (i.e., agreements plus disagreements). The ratio resulted in a percentage agreement across codes. Miles and Huberman (1994) suggested that an IRR of 80% agreement between researchers on 95% of the codes could be interpreted as sufficient agreement, or reliability. Our interrater reliability was 80.82% for complete codes (primary and secondary matched) and 97.73% for primary codes only (only primary code matched) across four researchers for 100% of the data. Thus, our interrater reliability constituted sufficient agreement overall (Miles and Huberman 1994). The consensus code was the code agreed upon by at least two researchers. For statements on which all researchers listed different primary codes, the item was designated into the no code category. For statements on which researchers only agreed on the primary code, the item was designated into the no secondary code for that category.

Findings

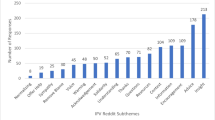

Table 1 provides the counts for the final consensus codes, both primary and secondary, for the 664 statements that were coded. This section summarizes the themes identified through the data analysis process in response to the open-ended question, what message would you want to send to people who have recently left an abusive relationship? Primary categories included (a) self-love and inherent strengths, (b) healing as a journey and process, (c) importance of social support, (d) leaving the abusive relationship behind, (e) focus on self-care, (f) guidance for new relationships, (g) practical issues and resources, (h) recommendations about children, (i) religious and spiritual messages, (j) obtaining education about IPV, and (k) advocacy and social action. The primary and secondary themes are listed below in order of highest to lowest frequency of participants’ responses.

Self-Love and Inherent Strengths

Self-love and inherent strengths included 170 statements where 64.64% of participants reminded new survivors of their inherent strengths and that they were worthy of love and happiness. Subthemes in this category included strength and courage; love, accept, and forgive yourself; deserve happiness and dignity; not your fault; praise from survivors; and other. In the strength and courage subtheme, participants praised new survivors and emboldened them to channel their inner strength. One participant stated, “You are a superhero, stronger than you can possible know, and keep telling yourself that until you believe it.” Another pointed out that the strength it takes to leave an abuser is akin to moving on, “Just as it took courage and strength to leave, you have the strength and courage to move forward and to be safe.” In the subtheme, love, accept, and forgive yourself, participant statements included those pertaining to the survivor’s ability to challenge their concept of self-worth and demand better for their lives. One participant stated, “Learn to love yourself. Forgive yourself. Become an optimist.” The subtheme deserve happiness and dignity centered around participants reminding survivors that they were deserving of fundamental rights. One participant stated, “You deserve love. You deserve peace. You deserve happiness. It is possible.” Another pointed to an internal sense of awareness and said, “You have all the power in the world right inside of you to make this life whatever you want it to be!”

Another subtheme, not your fault related to participants’ acknowledgment of the internalization of blame that some survivors develop. The subtheme praise from survivors included inspirational messages. One participant stated, “Be proud of yourself! You are amazing just for making the decision to end the relationship.” Within the other subtheme, participants shared general comradery and hope.

Healing as a Journey and Process

Healing as a journey and process included 137 statements where 52.09% of participants urged new survivors to view healing as a journey and to trust that things would get better. Subthemes in this category included it’s hard now, but it gets easier; small steps; post-traumatic growth; and other. In the subtheme it’s hard now, but it gets easier, participants encouraged new survivors to be patient and allow for healing over time. One participant identified with the difficulty in envisioning a life after IPV and acknowledged, “It may seem impossible now. Every bit of it.... Hope for the future, hope for ever finding love again, hope for your dreams, hope for children, hope for yourself… You will heal. You will be able to move on.” Another provided a gentle reminder that the pain would not last forever and said, “It hurts now. It hurts like you thought nothing ever could. But that goes away.” Lastly, one participant reported, “After the shock, when the fog lifts, things will start to get easier,” illuminating the slow but consistent progress to healing.

In the subtheme small steps, participants reassured new survivors to take it “one day at a time” and normalized the difficulty of leaving IPV relationships. This subtheme was different from it’s hard now, but it gets easier in that it focused specifically on the small steps that sometimes seemed insignificant but that were important to the overall progression of healing. One participant said, “No matter how small the steps and frustrating the progress may seem, you are on the road to recovery, a healing journey, and that is encouraging.” The subtheme post-traumatic growth described the transformation experienced by participants as a result of overcoming hardship. One remarked, “In the long run it will truly make you feel strong and powerful and make you feel much better about yourself.” Finally, the other subtheme involved additional statements that related to the journey and process of healing. Here, participants spoke to the nature of their experience as a true excursion, using metaphors to further illustrate positive outcomes. One participant shared,

I know this seems difficult and like the world is crashing down around you. However, the only thing that has crashed is the darkness and pain of a future not worthy of you. I know right now you may be scared, but after every storm there is a rainbow and there is a dawn that comes right when it seems the darkest, and the light breaks to show all the beauty of this world.

Importance of Social Support

The importance of social support category included 76 statements where 28.90% of participants outlined the need for and importance of informal social support, such as friends, family, and mentors. Subthemes in this category included find a support system; allow yourself to get support; seek out other survivors; don’t withdrawal recognize unhelpful people, distance self; and get involved socially (e.g. hobby). Within the subtheme find a support system, participants were eager to share the simple fact that help exists. One individual stated, “There is help out here for you. Look for it and keep looking for it. Sometimes it can be hard to find. Just insist. It will arrive.” Another subtheme, allow yourself to get support, was comprised of participant encouragement of survivors to take the steps needed to ask for help and especially to “trust that people want to help.” One urged, “Surround yourself with people that support you and believe you.”

The subtheme seek out other survivors included expressions of comradery and reminders to survivors that they were “in it together” and could learn from one another. One pointed to connecting with other survivors and stated, “Seek others who have been through it too and learn from them. Support each other.” In the subtheme don’t withdraw, participants stressed the need for social connection instead of isolation. One participant explained, “Don’t keep to yourself, don’t hide yourself or your feelings.” The subtheme recognize unhelpful people, distance self contained warnings to avoid inadequate social supports who perpetuated detrimental relationship patterns. An individual warned, “People will want to impose their views of your journey and when you are vulnerable… be aware.” The subtheme get involved socially (e.g. hobby) involved participants cheering survivors on, pushing them to “try doing new things, meet…different people.” Others encouraged them to explore the online space and said, “Get on [social media] - find support groups - this is where I [have] been able to keep some sanity – my online friends are priceless to me.” Lastly, other statements consisted of participants shedding light on the nature of social connections during this time in a survivor’s life.

Leaving the Abusive Relationship behind

This category included 68 statements in which 25.86% of participants shared advice and reminders for leaving an abuser. Subthemes in this category included don’t go back/sever connection; abusers don’t change; love is not supposed to hurt; learn from the abusive experience; and other. Within the subtheme don’t go back/sever connection, participants spoke of the absolute imperative to cut ties with abusers, despite the difficultly of leaving and staying away. One urged, “No matter how hard it may seem, no matter how he may try to convince you that he’s changed, run and don’t look back.” The subtheme abusers don’t change was comprised of individuals informing survivors that abusers typically repeat the cycle of abuse. A participant stated, “They do not change. They are ALWAYS sorry, but only until the next time.” The subtheme love is not supposed to hurt provided an opportunity for participants to highlight the inherent incompatibility of love and abuse.

In the subtheme learn from the abusive experience, individuals shared reminders to have strength in the face of an abuser’s likely remorse. An individual recounted,

They will call for a while and probably show a more human side of them to appeal to your heart because they know you are a caring person. Don’t give in to the manipulation, they just want you to think that you made the abuse seem worse in your head than it was. It sounds painful but don’t forget the abuse.

Statements coded as other included those meant to help survivors build a new perspective and expectation for love and relationships. One participant stated, “Remember, love means trust, respect, and honor.”

Focus on Self-Care

Focus on self-care included 59 statements by 22.43% of the participants and related to physical and emotional healing, in addition to self-care strategies for moving forward. Subthemes in this category included mental health; empowerment/self-esteem/finding self; expression; physical health; and other. Within the subtheme mental health, participants suggested ways in which survivors could heal by focusing on their mental wellbeing. One participant stated, “Counseling is very important, since the deepest wounds our abusers leave are the emotional ones.” The subtheme empowerment/self-esteem/finding self acknowledged the likely degradation of self that happens as a result of abuse as well as the criticality to rebuild. A participant explained, “It may take years, but you will regain your self-esteem.” Another implored, “Begin to identify things you love about yourself and grow that list daily.”

The expression subtheme encouraged resisting holding the pain inside. One participant instructed, “It’s okay to let go. It’s okay to not be strong sometimes. It’s okay to cry and scream and be afraid.” In subtheme physical health, participants recommended survivors start with the fundamentals of physical health. One participant advised, “Work with the practicals, i.e., [your] main needs are to eat properly regardless of how you feel, take your vitamins, monitor any disturbing sleeping patterns, [such as] if you have nightmares or simply can’t sleep.” Statements coded as other included participants’ recommendations of songs, books, and other resources penned for healing and growth.

Guidance for New Relationships

This category included 36 statements by 13.69% of participant and focused on guidance for new relationships, warning signs, and what love looks like after abuse. Subthemes in this category included there is love after IPV; focus on self before getting involved; and notice warning signs in new partners. The subtheme there is love after IPV included participants introducing hope for future love and healthy relationships. One participant stated, “There is someone out there who will truly love you AND make you feel safe. Don’t settle” and another one said, “Don’t let the pain someone else caused you to get in the way of someone good.”

In the subtheme focus on self before getting involved, participants emphasized the need to explore selfhood prior to a new relationship. One stated, “Learn to love yourself before jumping into another relationship.” Survivors shared cautionary tales urging participants to notice warning signs and red flags of dangerous relationships. One participant said, “You have to be alert to all the signs of abuse and if you see just a spark… get rid of that person quickly.” Participants also shared what to look for in new relationships: “Find someone who treats you with respect and loves your brain and who you are as a person.”

Practical Issues and Resources

This category included 28 statements by 10.65% of the participants outlining practical and tangible suggestions for new survivors. Subthemes in this category included safety first; invest in self (e.g. financial independence); legal support/rights; use all resources available; document everything; and other. The subtheme safety first involved participants pointing out practical tips for securing and maintaining safety as a foremost priority. One recommended, “Have a safe person and check in with them throughout the day, until things settle down. Have a safe word or phrase that will let them [know] you need help (just in case).” Another shared, “Most women who die at their partner’s hands, are killed when they leave the ex. That’s why hiding their address and phone number etc., and ensuring against tracking devices, is imperative for the safety of them and their children.” Invest in self involved participants offering concrete suggestions for securing independence, including fiscal and educational. One participant advocated, “Get an education so you can be totally independent.” Another encouraged, “Learn to be in charge of your own financials. Get a job.”

The subtheme legal support/rights consisted of ways in which new survivors could expand knowledge on the subject. One participant candidly stated, “Learn your rights!” Use all resources available was a subtheme in which participants prompted survivors to expand their awareness of possible help. One said, “Take advantage of all of the services offered by domestic violence organizations.” Others emphasized the importance of maintaining documentation of everything related to the abuse and legal measures. Additionally, the other subtheme involved statements asserting the basics of leaving for new survivors.

Recommendations for Children

This category included 16 statements where 6.08% of participants emboldened new survivors to prioritize the safety of themselves and their children, to consider the effects of IPV and leaving on children, and suggestions for how to handle issues of children. Subthemes in this category included children will be better off; advocate for children; and other. In the subtheme children will be better off, participants reminded new survivors of the dangers that staying with an abuser posed to their children and reinforced the thought that children should never be left behind or used as an excuse to stay. One participant recounted, “Yes, my children may have small scars from their father not being in their lives but I honestly feel they have become much better individuals than they would have if he had been in their lives…” Participants also highlighted the benefits for children by leaving the abuser. One said, “If you have children, they will one day thank you, and be assured that they will grow up to be happier and healthier adults.” Another participant acknowledged the potential for a generational pattern and declared, “If you won’t change for yourself, do it for your kids or they will grow up to walk in your footsteps.”

In the subtheme advocate for children, participants shared messages relating to children’s rights and navigating the legal system. One stated, “Be [an] advocate of your child, your rights, and [the] rights of children to be safe and loved.” Other statements mainly related to the encouragement of new survivors to consider how their choices would affect their children’s health and safety. These statements also highlighted the importance of prioritizing the survivor’s own safety. One said, “You can’t care for your children until you first care for yourself.”

Religious and Spiritual Support

This category included 13 statements where 4.94% of participants urged new survivors to utilize religious and spiritual support as a means of coping, restoring belief in love, and trusting that things would get better. Subthemes in this category included you are loved by God; pray; forgive the abuser; and spiritual encouragement. In the subtheme you are loved by God, participants encouraged new survivors to find comfort in God. One reassured, “God never leaves you. Look to Him for support and guidance.” The pray subtheme consisted of participants pointing to prayer and other spiritual pursuits to help survivors better understand their experience. Forgive the abuser subtheme involved participants attesting to the fact that forgiving their batterers was a means of moving forward and healing. One participant reassured, “Just stay calm, forgive if you can.” Lastly, the spiritual encouragement subtheme included simple maxims and other guidance, such as, “This too shall pass.”

Obtaining Education about IPV

This category included 8 statements where 3.04% of participants shared the importance of becoming educated about abuse and prevention in addition to exploring healthy relationships. Subthemes in this category included learn about abuse; and learn what is healthy. The learn about abuse subtheme contained encouragement to participate in support groups, listen to music, read books, and seek out conferences and other learning opportunities to increase survivor knowledge of IPV. One participant noted, “Seek out education about abuse and learn what not to do.” Another said, “Educate yourself on abusive relationships, so that you can heal.” Within the subtheme learn what is healthy, participants shared the importance of knowing the dynamics of a healthy relationship and how to avoid IPV relationships in the future. Participants also suggested the works of Deepak Chopra, Barry Goldstein, and Lundy Bancroft’s books, The Batterer as Parent and When Dad Hurts Mom.

Advocacy and Social Action

This category included 8 statements where 3.04% of participants shared the power of giving back and the value each individual’s survival plays in helping others currently involved in IPV relationships. Subthemes in this category included changing the world by leaving; and helping other survivors. The subtheme changing the world by leaving highlighted the larger implications of leaving an IPV relationship. One participant uncovered the intrinsic connectivity of survivors by saying, “There is a piece of you in every woman, and a piece of every woman in you.” Another pointed to the impact the act of leaving has on other survivors and stated, “When you leave, and stay away from an abusive relationship, you are empowering other women too.” The helping other survivors subtheme included participant suggestions to “join the fight to protect others” and informed survivors of the power of helping others through advocacy. Moreover, they provided examples of how transformative helping had been in developing their own self-concept. One participant reflected, “I am grateful to have experience[d] domestic violence because I am able to help others in a different way than someone who does not understand where the victims are coming from.” Another shared the anecdote that “volunteering is a great way to get some self-esteem back and help someone less fortunate while doing so.”

Discussion

Although we are gaining a richer awareness of the dynamics of IPV, there is still much to learn about the growth-facilitating and growth-hindering processes for survivors when they choose to leave an abusive relationship. Currently, no study has explored what messages, advice, and words of encouragement long-term survivors of IPV have for individuals who have recently left abusive relationships. This study sought to better understand themes from long-term survivors with the hope that this information would add to the IPV recovery literature by infusing survivors’ perspectives in a way that has not yet been considered. The findings reflect the voices of 263 survivors who made 664 statements based on the open-ended question, “What message would you want to send to people who have recently left an abusive relationship?” The statements coalesced around 11 primary themes: (a) self-love and inherent strengths, (b) healing as a journey and process, (c) importance of social support, (d) leaving the abusive relationship behind, (e) focus on self-care, (f) guidance for new relationships, (g) practical issues and resources, (h) recommendations about children, (i) religious and spiritual messages, (j) obtaining education about IPV, and (k) advocacy and social action.

Past research on the recovery process from IPV has primarily focused on survivors’ own experiences (i.e., positive and negative) after leaving abusive relationships. Missing from the literature was a retrospective look at the facilitative elements involved in survivors’ routes to recovery. These messages may be missed when solely exploring individuals’ own experiences because they do not emphasize the learned experience. That is, what were participants’ essential practical needs (e.g., financial independence; safety focus; physical and mental health care)? How did participants overcome certain struggles (e.g., dealing with unhelpful supports)? How were participants able to maintain boundaries and safety (e.g., take advantage of resources; not believe the abuser’s change language)? And, finally, were there certain elements, initially overlooked, that participants eventually realized were critical to recovery (e.g., self-compassion; viewing recovery as a long-term process that became easier)? Gaining this additional vantage point added an additional perspective to understanding the process of recovery and provided useful information for survivors at any stage in their recovery journey.

The findings in the present study show support for internal and external supports and processes that have been identified in previous studies (e.g., Davis and Taylor 2006; Flasch et al. 2015, 2019) and that might be vital to the course of recovery. For example, the themes of self-love and inherent strengths, focus on self-care, and religious and spiritual messages highlight the internal dynamics. Additionally, themes stressing the importance of social support, practical issues and resources, recommendations about children, and obtaining education about IPV and advocacy are similar to research findings that stress the impact of external and practical resources, but add a specificity that is often missing in existing literature. Within this group of themes, it is important to note that survivors placed added emphasis on the need for believing in and encouraging one’s inherent worth (i.e., internal factors) over the external factors of support. This is somewhat different from past research that emphasized the central need for external resources (Dumitrescu 2018; Bostock et al. 2009). The current findings stress the critical role of self-compassion, self-forgiveness, and encouragement throughout the course of recovery, perhaps as a foundation for being able to access outside resources.

Our findings further represent a unique contribution to the existing literature in that it provides a new data point for considering personal experiences of recovery from IPV. In general, the perspectives of the survivors in the present study were consistent with previous research findings (e.g., Abrahams 2007; Flasch et al. 2015; Lewis et al. 2015; Smith 2003; Song 2012; Wuest and Merritt-Gray 2001), in that they stressed the need for encouragement, seeing recovery as a long-term process, and the importance of obtaining outside help. This congruence is seen in the top three themes: self-love and inherent strengths (64.64%), healing as a journey and process (52.09%) and the importance of social support (28.90%). Additionally, our findings support the idea that recovery is a complex process and that healing occurs over time. Themes that illustrate this dynamic include healing as a journey and process, leaving the abusive relationship behind, and guidance for new relationships. Looking more closely at the details of the recovery process, the participants in the present study conveyed the struggle and recursive nature of recovery from IPV that researchers have attempted to illuminate. The findings contain consistent messages from survivors that healing takes time and that the process is difficult, but that it gets better and that growth comes after the pain. This blend of initial caveat paired with hope adds a unique perspective to past research that has attempted to define the multifaceted road to recovery from IPV.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the narrowness of the population under investigation. This sample was almost exclusively heterosexual (96.20%) and female (88.21%), so the results may not accurately represent sexual and gender minorities and people who identify as male. Further, 79% of the sample was Caucasian/White, which may have limited the voices, unique experiences, and contextual struggles of racial and ethnic minorities. We also did not distinguish between participants based on the type of abuse they experienced or the duration of the abusive relationship, which may have influenced messages of advice based on different recovery phases of survivors. Moreover, though participants were survivors of IPV who had been out of abusive relationships for at least two years, we did not have information regarding the wellness of the present participants. That is, responses were likely influenced by each individual’s healing process and could change over time. Additionally, though there is the potential for researcher bias in interpreting and categorizing the quotes in to themes and subthemes, the authors took detailed steps, including utilizing multiple coders and establishing interrater reliability to minimize bias.

Finally, this study was part of two larger studies in which the open-ended question regarding messages to survivors was asked at the end of each survey. Only about half of the participants in the larger studies answered the open-ended question used in present study. Thus, it is possible to speculate that there may be inherent differences between participants who chose to answer the question and those who did not. Further, because the open-ended question under investigation was located at the end of the surveys in the larger studies, it is possible that fatigue contributed to participants’ responses (e.g., shortened the responses). Despite these limitations, the present study provides valuable insight into longer-term IPV survivors’ messages for new survivors.

Implications for Practice

It is our hope that the themes distilled from the survivor responses provide encouragement and practical strategies for individuals during the critical time immediately after leaving abusive relationships. Additionally, findings may serve as potential content for mental health practitioners who provide counseling to this population. The voices from survivors in this study contribute a unique perspective to the literature and add a different vantage point to what might facilitate successful transition from an abusive relationship to a healthier life. These findings may be used to craft intervention materials that could be incorporated in counseling.

Specifically, interventions and support services can be developed to target the most common themes. The category that included the greatest number of statements focused on encouragement of self-love and inherent strengths. Knowing that survivors find these aspects helpful can facilitate the integration of these messages into treatment in the form of affirmation exercises or the development of support groups as a preferred counseling modality. Additionally, strategies aimed at providing social support and other resources can be helpful to survivors. The respondents noted how important it was to seek out other survivors and realize that the person seeking help was not alone in the struggle. As a response, agencies could explore developing a mentorship program where long-term survivors are paired with those new to the process. Best-practices in group work encourage psychoeducational groups utilize research to support the curriculum themes chosen (ASGW 2000). The findings of this study could thus be a valuable resource as a foundation for a group curriculum. Infusing the voices of survivors into the treatment protocol could be easily integrated into existing approaches, especially ones that address congruent themes (Dugan and Hock 2018). In this way, the additional strand of information can be used as a way to support and expand existing approaches of treatment.

Specific to enhancing outcomes in group counseling, group processes encourage the development of a sense of cohesion and universality as two primary acknowledged curative factors (Yalom and Leszcz 2005). The use of client/survivor stories as a method to generate cohesion and universality has been a practice in many types of groups, including substance abuse groups and offender treatment groups (Fall and Howard 2017) The stories or testimonials provide an insider-expert perspective that helps group members feel they are in the right place, are understood, and that there is hope for change. The findings of this study could be organized into thematic stories to be integrated into the curriculum of existing support groups with the clinical rationale of facilitating curative factors.

Future Research

The findings in the current study illuminate several pathways for further study. One avenue of inquiry is to explore the difference between messages of newly-IPV-free individuals versus those who have been out of abusive relationships for a longer time period. It is possible that there are qualitative differences in themes as the recovery process evolves. It may be helpful to see what changes occur in the themes over a two, four, or even ten-year span and discern how that might affect the support process of the survivor.

Though this sample was overwhelmingly heterosexual, the research on characteristics of IPV within sexual and gender minority relationships deserves attention. Applying the methodology of this study to such samples may prove helpful in providing understanding of the dynamics of IPV in these populations. Additionally, future studies could expand the lens of various populations to see how the messages vary across groups. For example, the current study included primarily White/Caucasian women; however, exploring perspectives of male-identified survivors or ethnic and religious minorities would be potentially valuable in increasing insight into the dynamics of these populations. The findings in the present study point to the importance of both internal and external supports, but the interaction between these two types of supports has not been studied. It would be interested to investigate how internal and external supports influence and impact access to one another. For example, do higher levels of internal support increase one’s ability to seek and procure a higher amount of external support, or vice versa? In other words, what is the relationship between internal and external support in the IPV recovery process? Lastly, great insight can be gathered by examining how survivors’ messages affect those who have recently left abusive relationships. The current study provided the vital foundation of accessing the voice of the survivor to provide possible elements of recovery; however, it did not measure the effect of these messages on new survivors, the intended audience. One potential avenue is to form a psychoeducational group based on the survivor message themes; data could be collected on the impact of these themes on the group members’ healing process.

Conclusion

This study fills a void in the literature and includes the voices of survivors as contributors to the healing process of IPV. The data provides insight from individuals who have successfully extricated themselves from abusive relationships. The findings illuminate clear themes that can be further explored and integrated into treatment approaches to assist individuals who have recently left abusive relationships. With this information, it is the authors’ hope that the messages will not only be helpful, but that the findings will promote further exploration into the knowledge survivors can impart to the treatment of the impact of IPV.

References

Abrahams, H. (2007). Supporting women after domestic violence: Loss, trauma and recovery. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Ai, A. L., & Park, C. L. (2005). Possibilities of the positive following violence and trauma: Informing the coming decade of research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504267746.

Allen, K., & Wozniak, D. F. (2011). The language of healing: Women's voices in healing and recovering from domestic violence. Social Work in Mental Health, 9(1), 37–55.

Anderson, K. M., Renner, L. M., & Danis, F. S. (2012). Recovery: Resilience and growth in the aftermath of domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 18(11), 1279–1299.

Association for Specialists in Group Work (ASGW). (2000). ASGW professional standards for the training of group workers. Journal for Specialist in Group Work, 25, 237–244.

Baly, A. R. (2010). Leaving abusive relationships: Constructions of self and situation by abused women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 2297–2315.

Beeble, M. L., Bybee, D., Sullivan, C. M., & Adams, A. E. (2009). Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016140.

Bergman, B., & Brismar, B. (1991). A 5-year follow-up study of 117 battered women. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 1486–1489.

Bostock, J., Plumpton, M., & Pratt, R. (2009). Domestic violence against women: Understanding social processes and women’s experiences. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.985.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014). Intimate partner violence: Definitions. Retrieved November 10, 2018, from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Cerulli, C., Trabold, N., Kothari, C. L., Dichter, M. E., Raimondi, C., Lucas, J., Cobus, A., & Rhodes, K. V. (2015). In our voice: Survivors’ recommendations for change. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9657-7.

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., & Smith, P. H. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 260–268.

Davis, K., & Taylor, B. (2006). Stories of resistance and healing in the process of leaving abusive relationships. Contemporary Nurse, 21(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2006.21.2.199.

Dugan, M. K., & Hock, R. R. (2018). It’s my life now (3 rded.). New York: Routledge.

Dumitrescu, A. (2018). Personal and community resources for the victims of domestic violence. Social Work Review / Revista De Asistenta Sociala, 17(3), 107–113.

Estrellado, A. F., & Loh, J. (2013). Factors associated with battered Filipino women’s decision to stay in or leave an abusive relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(4), 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505709.

Evans, I., & Lindsay, J. (2008). Incorporation rather than recovery: Living with the legacy of domestic violence. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31, 355–362.

Fall, K. A., & Howard, S. (2017). Alternatives to domestic violence (4th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Farrell, M. L. (1996). Healing: A qualitative study of women recovering from abusive relationships with men. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 32, 23–32.

Flasch, P. S., Murray, C. E., & Crowe, A. (2015). Overcoming abuse: a phenomenological investigation of the journey to recovery from past intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(22), 3373–3401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515599161.

Flasch, P. S., Boote, D., & Robinson, E. H. (2019). Considering and navigating new relationships during recovery from intimate partner violence. Journal of Counseling and Development, 97, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12246.

Gagnon, K. L., Wright, N., Srinivas, T., & DePrince, A. P. (2018). Survivors’ advice to service providers: How to best serve survivors of sexual assault. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(10), 1125–1144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1426069.

Haney, W., Russell, M., Gulek, C., & Fierros, E. (1998). Drawing on education: Using student drawings to promote middle school improvement. Schools in the Middle, 7(3), 38–43.

Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Hou, W.-L., Ko, N.-Y., & Shu, B.-C. (2013). Recovery experiences of Taiwanese women after terminating abusive relationships: A phenomenological study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 157–175.

Kaysen, D., Dillworth, T. M., Simpson, T., Waldrop, A., Larimer, M. E., & Resick, P. A. (2007). Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1272–1283.

Khaw, L., & Hardesty, J. L. (2007). Theorizing the process of leaving: Turning points and trajectories in the stages of change. Family Relations, 56, 413–425.

Lewis, S. D., Henriksen, R. C., Jr., & Watts, R. E. (2015). Intimate partner violence: The recovery experience. Women & Therapy, 38, 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2015.1059223.

Mechanic, M., Weaver, T., & Resick, P. (2008). Mental health consequences of intimate partner abuse: A multidimensional assessment of four different forms of abuse. Violence Against Women, 14, 634–654.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Morgan, M., & Coombes, L. (2013). Empowerment and advocacy for domestic violence victims. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(8), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12049.

Murray, C. E., Crowe, A., & Brinkley, J. (2015a). The stigma surrounding intimate partner violence: a cluster analysis study. Partner Abuse, 6(3), 320–336.

Murray, C. E., King, K., Crowe, A., & Flasch, P. S. (2015b). Survivors of intimate partner violence as advocates for social change. Journal of Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 7(1), 84–100.

Patzel, B. (2001). Women’s use of resources in leaving abusive relationships: A naturalistic inquiry. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22, 729–747.

Ratts, M. J., & Hutchins, A. M. (2009). ACA advocacy competencies: Social justice advocacy at the client/student level. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 269–279.

Smith, M. E. (2003). Recovery from intimate partner violence: A difficult journey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24, 543–573.

Song, L. (2012). Service utilization, perceived changes of self, and life satisfaction among women who experienced intimate partner abuse: The mediation effect of empowerment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 1112–1136.

Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation, 7, 1–6.

Sullivan, C. M., López-Zerón, G., Bomsta, H., & Menard, A. (2018). There’s just all these moving parts: Helping domestic violence survivors obtain housing. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0654-9.

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO, 1996). Content analysis: A methodology for structuring and analyzing written material. GAO/PEMD-10.3.1. Washington, D.C.

Voth Schrag, R. J. (2015). Economic abuse and later material hardship: Is depression a mediator? Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 30(3), 341–351.

Wuest, J., & Merritt-Gray, M. (2001). Beyond survival: Reclaiming self after leaving an abusive male partner. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 32, 79–94.

Yalom, I., & Leszcz, M. (2005). Theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Zapor, H., Wolford-Clevenger, C., & Johnson, D. M. (2015). The association between social support and stages of change in survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(7), 1051–1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515614282.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flasch, P., Fall, K., Stice, B. et al. Messages to New Survivors by Longer-Term Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J Fam Viol 35, 29–41 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00078-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00078-8