Abstract

Evidence on the relation between women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to marital violence has been inconsistent across studies. This study examined how women’s various levels of microcredit participation are associated with marital violence against women (MVW), while also taking into account the husbands’ gender ideology. The study included 243 wife-abusive men in rural Bangladesh. Multiple regressions were performed to predict the frequency of MVW in the preceding year. Of the married women, 52.3 % were microcredit participants, 11.1 % of whom were active participants and 41.2 % nominal participants. The study showed that women’s active microcredit participation was negatively associated with MVW, and nominal participation was positively associated with MVW among the husbands who held a more conservative gender ideology. The findings suggest that women-focused microcredit interventions should also take into account men’s gender ideologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Microcredit is widely considered to be a means of empowering women in ways that enhance their socioeconomic status. In many low-income countries, microcredit-based, women-focused, poverty reduction intervention has become a controversial issue connected with marital violence against women (MVW) (Hadi 2005; Kim et al. 2007; Schuler et al. 1998). The reason for this controversy is that the relation between women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to male marital violence has been inconsistent across studies. A few studies have indicated microcredit as a protective factor of MVW (Bates et al. 2004; Hadi 2005; Kim et al. 2007; Manderson and Mark 1997), but other studies have stated that women’s microcredit participation is as a risk factor of MVW (Bhuiya et al. 2003; Koenig et al. 2003; Naved and Persson 2005; Schuler et al. 1998).

In a patriarchal society like Bangladesh, microcredit participation can allow women to have an income of their own, which may in turn improve their socioeconomic status. However, there may not be a linear relationship between women’s microcredit participation and MVW. This connection might also be associated with factors related to men, such as their gender ideology (Atkinson et al. 2005). Previous studies have revealed that many female microcredit borrowers were just nominal microcredit participants, and the loan was actually controlled and used by their husbands (Goetz and Gupta 1996; Kabeer 2001; Karim and Law 2013). Consequently, women’s microcredit/loan-borrowing status may not necessarily ensure their active microcredit participation, loan control, and investment of the loan towards an income-earning project. This study, therefore, aimed: a) to assess how different levels of microcredit participation are associated with MVW, and b) to examine the moderating effects of the husbands’ gender ideology on the relationship between women’s microcredit participation and MVW.

Literature Review

Marital Violence in Rural Bangladesh

Male marital violence is a serious public health problem in rural Bangladesh. A recent nationwide survey showed that 77 % of currently married women had experienced physical, sexual, or psychological violence by their husbands in the past 12 months (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [BBS], & Statistics and Informative Division [SID] 2013). Patriarchy has often been regarded as the main cause of widespread MVW in Bangladesh (Baden et al. 1994; Hartmann and Boyce 1983; Jahan 1994). One study revealed that 79.3 % of Bangladeshi women believed that a man has the right to beat his wife under certain circumstances, such as if she does not complete the housework, disobeys the husband, or is unfaithful (García-Moreno et al. 2005). Baden et al. (1994) and Bhuiya et al. (2003) mentioned many cases of wife battering being used as a punishment. Another study indicated that patriarchal ideology legitimized male marital violence as a socially accepted action, whereby violence was used as a means of controlling women’s socioeconomic behaviors (Karim et al. 2012).

Microcredit and Women’s Socioeconomic Development

Microcredit is defined as the expansion of micro-loans to a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. It is also recognized as a poverty-reduction intervention in both low-income and high-income countries (Salt 2010; Schurmann and Johnston 2009). Microcredit programs target economically disadvantaged people who are typically abandoned by conventional banks, which rarely offer loans to individuals who lack collateral, stable employment, and a certifiable credit history. It is presumed that microcredit allows economically disadvantaged people to pursue income-generating entrepreneurial projects, which ultimately enable them to better afford to care for themselves and their family (Schurmann and Johnston 2009).

Women’s Status and Microcredit Programs in Rural Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in the world. About 26 % (from a low of 21 % in urban areas to a high of 35 % in rural areas) of the people live below the poverty line, earning less than US$2 per day (World Bank 2013). Poverty is most severe in rural areas, where 78 % of Bangladeshis live. Women in particular are constrained by property, education, freedom, and career. Therefore, microcredit programs mainly target women, who comprise almost 97 % of loan borrowers. Microcredit is not only considered an element in poverty reduction, but a means of empowering women in ways that improve their skills, capabilities, and socioeconomic status (Hadi 2001; Schuler et al. 1996). Hence, it is believed that women’s microcredit participation will enhance their socioeconomic status and, therefore, reduce their vulnerability to male marital violence.

Gender Ideology and Microcredit Participation

The term ideology bears a variety of meanings within specific literature. In this study, gender ideology was defined as people’s attitudes toward gender-specific roles, rights, and responsibilities (Kroska 2007). Kroska (2007) argued that the construct of gender ideologies is one-dimensional and ranges from conservative to liberal. She posited that in conservative ideology, men are expected to fulfill their (decision-making) family roles through bread-winning activities, and women are expected to fulfill their (dutiful) roles through homemaking and care-taking activities. In liberal gender ideology, on the other hand, both women and men share all bread-winning, care-taking, and decision-making roles (Kroska 2007).

Gendered Ideology and Gender Roles in Rural Bangladesh

Conservative gender ideology is believed to be the root of the patriarchal social structure prevalent in Bangladesh (Baden et al. 1994; Hartmann and Boyce 1983; Jahan 1994). Religious norms, such as purdah, constrain women from joining in activities outside the home. Purdah—the veiled seclusion of women—is a systematic way of subordinating women (Kabeer 1990). Because purdah does not allow women to move freely, it is considered that the husband’s main responsibility is to maintain the family financially and be the breadwinner, while the wife’s main task is to care for family members.

Gender Ideology and Women’s Microcredit Participation

Women’s microcredit participation was supposed to be a redefinition of traditional gender roles in rural Bangladesh because it would give women the opportunity to be the breadwinners of the household. However, in reality, it has been observed that few women actually have control over the loans (Goetz and Gupta 1996; Kabeer 2001). A previous study revealed that the loans given to married women were mostly controlled by the husbands (Karim and Law 2013). The study further discovered that this was related to the husbands’ gender ideology: conservative men controlled and used the loans taken by their wives (Karim and Law 2013). Therefore, the current study speculated that there might be a significant interaction effect of the husbands’ gender ideology in the relationship between microcredit and marital violence.

Microcredit and Marital Violence in Rural Bangladesh

Apart from the extension of microcredit programs and their popularity among policymakers, there has been a lack of consistent data about the success of microcredit. Studies have indicated both positive and negative consequences of microcredit for women. For example, a few studies have shown that microcredit participation improved women’s socioeconomic status, raised their self-esteem, and reduced their vulnerability to male marital violence (Ahmed et al. 2001; Hadi 2001; Mahjabeen 2008; Schurmann and Johnston 2009). Other studies, however, have stated that women’s microcredit participation increased their workload and family conflict, leading to an escalation of MVW as it threatened men’s patriarchal authority (Bhuiya et al. 2003; Hossain 2002; Meade 2010; Schuler et al. 1998). Inconsistency in data across studies related to the levels of women’s active/income-earning microcredit participation and empowerment has also been obvious. Further, these studies have seldom assessed the effects of microcredit on women’s vulnerability to marital violence in relation to their husbands’ gender ideology.

In general, there is a lack of studies analyzing how women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to male marital violence are associated with factors related to men. Such an understanding is imperative for women’s safety and well-being. Thus, this study examined how the magnitude/level of women’s microcredit participation is associated with their exposure to male marital violence, while also taking into account the husbands’ gender ideology.

Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

Many studies have assessed the relationship between microcredit and marital violence (Bhuiya et al. 2003; Frazier and Tix 2004; Hadi 2005; Kim et al. 2007; Koenig et al. 2003; Manderson and Mark 1997; Naved and Persson 2005; Schuler et al. 1998). Our previous study also revealed a significant association between the husbands’ gender ideology and the wives’ microcredit participation (Karim and Law 2013). However, there seems to be a gap in the literature that shows how gender ideology is influential on the relation between women’s microcredit participation and their vulnerability to marital violence. In the current study, we hypothesized that the husbands’ gender ideology may moderate the effects of women’s microcredit participation on MVW in rural Bangladesh.

The conceptual model used in this study was rooted in the ideological component of patriarchy theory. Patriarchy refers to the systematic organization of male supremacy and female subordination, which operates through social, political, religious, and economic institutions (Kramarae 1992). In a patriarchal family organization, men are considered the head of the household and, therefore, are primarily accountable for the economic support as well as for the authority of the family. Lerner (1986) argued that, patriarchy—male dominance over women—has emerged through a historical process and is maintained by culture and social institutions, living through practices such as gendered division of labor (e.g., economic work for men and home-making work for women) (Kidwai 2001; Kramarae 1992). In short, patriarchy theory asserts that, patriarchal gender ideology, which legitimizes male superiority and female inferiority (Kramarae 1992), is the source of gendered division of labor, gender inequality, and subordination of women (Bograd 1988; Dobash and Dobash 1977–78, 1979; Yllo 2005).

Gender ideologies may range from conservative, characterized by the belief that husbands should be the primary breadwinners and wives should remain at home, to liberal, the belief that husbands and wives should share the work involved in family life (Atkinson et al. 2005). Thus, the husbands’ gender ideology may moderate the relation between women’s microcredit participation and MVW (Goetz and Gupta 1996). For example, conservative men who believe they are supposed to provide economic support for the family may control their wives’ loans, which might result in increasing family conflict, leading to an escalation of MVW. In contrast, liberal men may see their wives’ active microcredit participation as support of the family economy. Gender ideology, therefore, may provide a lens through which to view the effects of the magnitude of women’s microcredit participation on MVW.

Given the above discussion, this study hypothesized that: H 1 : There will be a non-linear relationship between the levels of women’s microcredit participation and MVW. In other words, a) women’s active microcredit participation will be negatively associated with MVW, and b) women’s nominal microcredit participation will be positively associated with MVW. H 2 : Husbands’ gender ideology will moderate the relationship between microcredit participation and MVW. In particular, a) women’s active microcredit participation will be negatively related to MVW for liberal husbands, and b) women’s nominal microcredit participation will be positively related to MVW for conservative husbands.

Methods

Participants

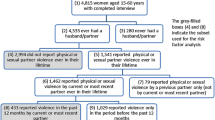

This study only used the current wife-abusive married men data from a larger study entitled “Gender Ideology, Microcredit and Marital Violence in Rural Bangladesh,” which was conducted in 2009. The first author of this paper was also the principal investigator of the 2009 study. The focus of the 2009 main study was to examine the relationship between women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to marital violence from a male perspective.

The 2009 study followed a cross-sectional design. Fieldwork was conducted in five, purposively selected, northwest Bangladesh villages. All villages were 20–30 km northwest of Rajshahi district headquarters. The presence of familiar microcredit programs was taken into account in selecting the villages. There were 15 microcredit organizations. For the main study, the participants were 342 randomly selected married men in the villages. The estimated minimum sample size was 310 out of a total of 1367 (Yamane 1967), however, the current study only included the data of the 243 wife-abusive men identified in the 2009 main study.

Dependent Variable

Marital Violence Against Women (MVW)

This study conceptualized MVW as any act by a husband that results in physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to his wife (García-Moreno et al. 2005). The frequency of marital violence over a one-year recall period was measured. A 14-item questionnaire was used, which included three aspects of violent behaviors: psychological assault, physical attack, and sexual coercion (see Table 1). For every item, each answer was rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = single time, to 4 = seven times or more. The summated scores across items yielded a total score, a higher score indicating women’s higher exposure to marital violence. The scale was mostly adapted from the questionnaire used in the “Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women” that was developed by a World Health Organization (WHO) team (García-Moreno et al. 2005).

Principal factor analysis (PFA) with oblique rotation was conducted to test the construct validity of the scale (Hair et al. 2010). Though the results related to pattern-matrix revealed a three-factor solution explaining 58.81 % of the total variance, the structure-matrix showed that all items of the scale were too highly correlated. High inter-correlations between the three subscales were also revealed. This suggested a unifactorial dimension of the scale, with an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.87 (Hair et al. 2010).

Independent Variables

Husband’s Gender Ideology

The Attitudes Towards Women Scale (AWS) used in this study was adapted from the 25-item short version of the AWS developed by Spence et al. (1973). The AWS was prepared to assess people’s gender ideology, focusing on their attitudes toward the rights and roles of women in contemporary society, and has been widely used to measure men’s gender ideology in particular (Goldson 2005). The following item is an example from the scale: “A woman should not expect to go to exactly the same places or to have quite the same freedom of action as a man.”

The AWS was developed in a Western context and had not been validated in Bangladesh. Therefore, the scale was translated into Bengali, and its representational validity was established. Four Bangladeshi postgraduate scholars were engaged in translating the scale independently, working to ensure the translation followed culturally appropriate meanings for the items. After that, a group discussion was arranged to finalize the translation. A few items were revised. For example, item number 11,“Women earning as much as their dates should bear equally the expense when they go out together,” was not considered culturally appropriate in the Bangladesh context. Therefore, the item was modified to: “Besides her husband, a woman should support the family through earning an income.” Other culturally sensitive items were modified similarly.

Each item of the AWS was scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = most conservative view, to 3 = most liberal view. Summated scores across items yielded a total score, a lower score indicating a conservative ideology. PFA was conducted to test the construct validity of the AWS scale (Hair et al. 2010). This suggested a unifactorial dimension of the translated AWS scale, with an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.92 (Hair et al. 2010).

Microcredit Participation

Women’s microcredit participation was conceptualized as women’s active involvement in the use of loans for earning an income. Participation was identified as having different levels: non-participation, nominal participation, and active participation. As Bina Agarwal (2001) has argued, mere membership cannot reflect true participation until women’s roles in it are taken into account. In the present study, the magnitude of women’s microcredit participation was examined by their involvement in the use of loans, such as: a) whether the woman borrowed a loan for 1 year or more; b) if the woman borrowed a loan, whether she was controlling the loan by herself; and c) if the woman was controlling the loan, whether she was using/investing the loan in an income-earning enterprise. Considering the answers to these questions, a nominal variable was created with three categories: a) Non-participation = non-borrowers of loans; b) Nominal Participation = women are loan-borrowers, but the loans are controlled and/or used by their husbands; and c) Active Participation = a woman herself controls the loan, and the loan is used for an income-earning enterprise.

Controlled Variables

Based on previous findings related to correlates and factors associated with marital violence in Bangladesh, the study proposed few controlled variables to be included in the analysis. Marital duration (in years), husband’s education, wife’s education, and household landholding were included as controlled variables. The men involved in the study were from 20 to 65 years old (M = 36.76, SD = 10.90). The ages of their wives ranged from 15 to 60 years, with a mean of 29.93 (SD = 9.42). The range of the men’s marital duration with their current wives was from 1 to 49 years, with a mean of 14.93 (SD = 10.35). Because of a high correlation among marital duration, husband’s age, and wife’s age, only marital duration was included in the analysis. Both the husband’s and the wife’s education were categorized into three levels: No education = did not attend any school; Low education = completed less than Secondary School Certificate, SSC (<10 years); and High education = attended higher education (> = SSC). For household landholding, respondents were asked to identify their land size level from three predetermined categories: Landless = having no land property, Marginal = owning less than 3 bigha (<99 decimals) of land, and Better-off = owning 3 bigha or more (> = 99 decimals) of land. Landholding size was included because it is one of the key determinants of household class position in rural Bangladesh.

Questionnaire Survey

A structured questionnaire was administered in face-to-face interviews. On-site, face-to-face interviews allowed the interviewer to interact with the respondents, which ensured a clear understanding of the survey questions as well as better-quality responses (Maxim 1999). The participation rate was high: almost 91 % of the respondents successfully completed the interviews.

Analytical Strategies

The data analysis was conducted in two parts using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc. 2007). First, descriptive statistics were conducted to provide profiles of the study participants, yearly frequency of male marital violence, gender ideology, and wife’s level of microcredit participation. Next, as a part of bivariate analysis, mean marital violence differences were tested using t-test and one-way ANOVA for categorical variables. Correlations were calculated for continuous variables. Second, multiple multivariate regressions were performed on the sample to identify factors associated with the Sqrt yearly frequency of MVW. The frequency of MVW was positively skewed (SK = 1.47, KR = 2.34); therefore, a square root transformation of the variable was performed, which approximately met the assumption of normality (SK = 0.59, KR = −0.25) (Bryman and Cramer 2009).

Because the predictor variable, microcredit participation, was a three-level categorical variable, we created two dummy coded variables: active participation and nominal participation. This enabled us to examine the effects of active participation and nominal participation compared to non-participation (Frazier and Tix 2004). Based on a theoretical cut-off point, the moderator variable, husbands’ gender ideology, was also categorized into two levels: liberal ideology, in which the AWS score was higher than 25, and conservative ideology, in which the score was 25 or lower. The starting point of liberal attitude on the 25-item AWS scale was set at any score above 25, and the scale considered 0 = most conservative view, 1 = conservative view, 2 = liberal view, and 3 = most liberal view. We chose effect coding (codes of −1 for liberal ideology and 1 for conservative ideology) because we wanted to interpret the first-order effects of microcredit participation and gender ideology as average effects (Frazier and Tix 2004). Finally, we created two interaction terms: a) the product of gender ideology code and active participation code, and b) the product of gender ideology and nominal participation code. To perform the analysis, we regressed the Sqrt frequency of MVW on active participation, nominal participation, and gender ideology in the main-effect model and then added the two interaction terms in the final model. Marital duration, husbands’ education, wives’ education, and household landholding were included in the models as controlled variables. In order to avoid the problem of multicollinearity, we included the centered values of all independent variables.

Ethical Issues

The 2009 study “Gender Ideology, Microcredit and Marital Violence in Rural Bangladesh,” was conducted in accordance with the operational guidelines and procedures recommended by the Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties, the University of Hong Kong (Reference No.: EA520309; date approved: March 31, 2009). All study participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and their oral consent was obtained before the data collection. Participants were reminded repeatedly that their participation was completely voluntary, and they had no obligation to complete the interviews and could drop out of the study at any time during the interview. The study participants were also informed that they might feel uncomfortable with some of the questions. Anonymity and confidentiality of the interviews were maintained.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean of the yearly frequency of MVW was 8.86 (SD = 7.63), ranging from 1 to 42, where frequency referred to the incidents of violent acts perpetuated by abusive men in the preceding year (Straus et al. 1996) (see Table 1). The average score of AWS indicated that the men were very conservative (M = 18.80, SD = 13.54). Using a theoretical cut-off point (Vittinghoff et al. 2005), the study revealed that only 21 % of the men upheld a liberal ideology (see Table 2). The study further showed that 52.3 % of the married women were microcredit participants (borrowers of micro-loans), with 11.1 % active and 41.2 % nominal participants. In other words, only 21.3 % of the loan-borrowing women were active microcredit participants who used the loans for earning an income, whereas in 78.7 % of cases, the loans were fully controlled by their husbands (see Table 2). Women’s income-earning projects included: goat, cow, and poultry raising; vegetable farming; food processing; handicrafts; setting up small shops; and so forth.

Bivariate Associations

From the bivariate analysis of the data, independent variables included in the analysis were found to be significantly associated with MVW (see Table 2). We also obtained bivariate correlations among the variables to make sure that the interaction terms and their components were not too highly correlated (see Table 3). This showed that marital duration, husbands’ education, wives’ education, husbands’ gender ideology, and wives’ microcredit participation were significantly associated with MVW (see Table 3). Therefore, results of bivariate analysis further indicated that the data met the preconditions for additional multivariate analysis and hypothesis testing. The results also showed that women’s higher level of education was negatively associated with both their non-microcredit participation and nominal participation, whereas women’s lack of education appeared to be positively associated with their active microcredit participation (see Table 3). Conversely, higher levels of educational attainment appeared to be positively associated with the liberal gender ideology of the husbands (see Table 3).

Multivariate Analysis and Results of Hypothesis Testing

Multiple regressions were used with Sqrt MVW as a dependent variable. In the main-effect model (Model 1 of Table 4), husbands’ gender ideology, two women’s microcredit participation variables (active participation and nominal participation), and four controlled variables (marital duration, husbands’ education, wives’ education, and household landholding) were included. These variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in total MVW scores, R 2 = .117, F(10, 232) = 3.059, p < .001. Women’s active microcredit participation appeared to be a significant protective factor of MVW, though women’s nominal microcredit participation and the husbands’ gender ideology were not shown to be significantly associated with MVW (see Table 4). In the final model (Model 2 of Table 4), the standardized regression coefficient for active microcredit participation was -.194, t(230) = −2.720, p < .007, meaning that there was a significant negative relation between women’s active microcredit participation and the yearly frequency of MVW in the sample. Therefore, H 1 —there will be a non-linear relationship between the levels of microcredit participation and MVW—was partly supported (see Table 4).

Next, two interaction terms, active participation × gender ideology and nominal participation × gender ideology, were entered into the second and final model of the regression (see Table 4). The interaction between women’s nominal participation and the husbands’ gender ideology was found to be statistically significant, β = .177, t (230) = 2.077, p < .039, but the interaction between women’s active participation and the husbands’ gender ideology did not appear statistically significant, β = .106, t (230) = 1.538, p < .126. Therefore, H 2 —husbands’ gender ideology will moderate the relationship between microcredit participation and MVW—was also partly supported. The R 2 change associated with the interaction terms was 0.02. In other words, the interaction between women’s microcredit participation and the husbands’ gender ideology explained an additional 2 % of the variance in the Sqrt MVW (see Table 4). Along with the interaction terms, the variables included in the final model accounted for a significant amount of variance in the MVW, R 2 = .136, F(12, 230) = 3.022, p < .001.

Controlled variables

Although household landholding did not appear to be a significant predictor of the frequency MVW in the final model, marital duration, β = −.280, t(230) = −3.848, p < .001, and both the husbands’ higher level of education, β = −.179, t(230) = −2.269, p < .024, and the wives’ higher level of education, β = −.182, t(230) = −2.125, p < .035, were suggested to be significant protective factors against the frequency of MVW in the sample (see Table 4).

For ease of presentation, Fig. 1 shows the yearly frequency of MVW, including the interaction effects of microcredit participation and gender ideology. From the figure, it can be perceived that women’s nominal microcredit participation may increase the frequency of MVW among husbands who hold a more conservative gender ideology. The figure also indicates that a woman’s active microcredit participation may reduce her vulnerability to male marital violence, regardless of the status of her husband’s gendered ideological positions (see Fig. 1).

Discussion

In summary, this study indicated that married women had experienced, on average, 8.86 incidents of marital violence by their husbands in the preceding year. It also revealed that 52.3 % of the women were microcredit participants (borrowers of micro-loans), with 11.1 % active participants (controlled and used the loans toward earning an income) and 41.2 % nominal participants (husband controlled and used the loans); in other words, only 21.3 % of the female microcredit-borrowers were active microcredit participants. The study also showed that most of the husbands were typically conservative: just 21 % upheld a somewhat liberal ideology. Multivariate analysis indicated that women’s active microcredit participation had a significant protective main effect on the frequency of MVW. It also appeared that women’s nominal microcredit participation may increase the frequency of MVW among husbands who hold a more conservative gender ideology (see Fig. 1).

We observed that the various levels of women’s microcredit participation were differently associated with their vulnerability to male marital violence in the sample. A body of previous studies indicated that microcredit participation improves women’s socioeconomic status and thereby reduces their vulnerability to male marital violence (Ahmed et al. 2001; Hadi 2001, 2005; Mahjabeen 2008; Schurmann and Johnston 2009). However, our current study revealed that only women’s active microcredit participation, as opposed to all kinds of microcredit participation, may reduce their vulnerability to male marital violence in rural Bangladesh. This result was consistent with that of our previous study which showed that women’s active microcredit participation significantly improves their socioeconomic status within the household (Karim and Law 2013).

We also saw in the case of one woman that microcredit participation may increase the frequency of MVW. Bhuiya et al. (2003), Koenig et al. (2003), Naved and Persson (2005), and Schuler et al. (1998) stated quite similar results in their studies and indicated that women’s microcredit participation, in general, escalated the risk of MVW. Our current study specifically revealed that women’s nominal microcredit participation may increase the frequency of MVW among husbands who hold a more conservative gender ideology. This result was consistent with the study of Atkinson et al. (2005), which showed a moderating effect of the husbands’ gender ideology on the relation between women’s socioeconomic status and the prevalence of MVW.

Our study notably indicated that women’s active microcredit participation as well as their improved socioeconomic status reduces their vulnerability to male marital violence. Previous studies also demonstrated that women’s improved socioeconomic status, such as independent income and higher education, reduced their vulnerability to male marital violence (Ahmed 2005; Aklimunnessa et al. 2007; Bates et al. 2004; Hadi 2000, 2005; Koenig et al. 2003). Furthermore, a recent study revealed that active microcredit participation increased women’s socioeconomic status as household co-breadwinner (Karim and Law 2013). Therefore, it is plausible that active microcredit participation improves the socioeconomic status of women and thereby reduces their vulnerability to male marital violence.

Our current study showed that women’s higher level of education is negatively associated with the frequency of MVW. It further indicated that women with higher education are not only less likely to borrow micro-loans, but they are similarly less likely to nominally participate in the programs, probably because women with higher education and higher socioeconomic status are not generally the target groups of the microcredit programs. The study also found that women with no education are more likely to actively participate in the microcredit programs. This result conformed to the result of the study by Kabeer (1990), who showed that economically disadvantaged women in rural Bangladesh are increasingly pushed into traditional male spaces—extra-household income-earning activities—influenced by the low economic condition of their household. Thus, though in different ways, both higher educational attainment and active microcredit participation may enhance the socioeconomic status of women within the household, and, therefore, both education and microcredit may similarly contribute to reducing women’s vulnerability to male marital violence.

Contrarily, previous studies have indicated that married Bangladeshi women’s participation in education, occupations, and other extra-household socioeconomic activities are traditionally controlled by their husbands (Baden et al. 1994; Cain et al. 1979). This is the reason the husbands’ gender ideology may provide a lens through which to view the levels of women’s microcredit participation. The current study also indicated that a husband’s conservative gender ideology may have a negative influence on his wife’s use of the loan. This finding was consistent with those of a previous study that showed microcredit-based, women-focused development intervention was generally constituted on an axis of prevailing gendered ideology in rural Bangladesh (Karim and Law 2013). Therefore, it is possible that the husbands’ gender ideology will moderate the relation between women’s nominal microcredit participation and MVW.

Nominal microcredit participation makes women economically burdened by the repayment obligation because women bear the formal responsibility for repayment, even though their husbands control the loan. Therefore, nominal microcredit participation may actually worsen women’s socioeconomic conditions within the household as well as make them more economically dependent on their husbands. This can then escalate women’s vulnerability to male marital violence among husbands who hold a more conservative gender ideology.

In short, the present study supports a proposal of the patriarchal theory of wife abuse whereby MVW appears to be maintained by women’s low socioeconomic status and moderated by the level of the husbands’ adherence to gendered ideology (Anderson 1997; Atkinson et al. 2005; Bograd 1988; Yllö 2005). Thus, women’s active microcredit participation and improved socioeconomic status may reduce their exposure to male marital violence. Women’s nominal microcredit participation and reduced socioeconomic status, however, may increase the frequency of MVW among men who hold a more conservative gender ideology.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

Although the current study is one of the few that has addressed women’s active microcredit participation from a gender perspective, it has some limitations that should be noted in order to understand the findings properly. With regard to the study participants, data on women’s experiences were collected entirely based on their husbands’ reports, which may contain biases. As a result, the frequency of women’s exposure to male marital violence might be underreported. It is also possible that conservative husbands negatively evaluated the participation level of their wives. Therefore, the study findings might be limited in their generalizability. The current study conceptualized gender ideology as one-dimensional, which might also preclude the possibility of multiple, complex, and/or combined factors in influencing MVW.

A number of possible confounding factors could also not be controlled for in the current study. For example, due to only a few non-Muslim study participants having been selected, religion could not be included in the analysis, and religion may influence both women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to MVW. Moreover, the current study followed a cross-sectional design that was correlational by nature, and, therefore, no causal inferences can be made from the results. This means that a thorough understanding of the directional relationship among the variables may not be achieved by the current study. Further study based on a longitudinal design is imperative in order to better understand these relationships.

While the current study has achieved optimum success regarding the purpose of the research and a reflection on the fulfillment, it lacks other perspectives to understand women’s income-earning scopes in relation to their microcredit participation in rural Bangladesh. For example, the current study could not focus on how women’s adherence to patriarchal ideology is associated with both women’s microcredit participation and their exposure to marital violence, though this may provide a better understanding about the phenomenon. Future studies should also take into account gender ideologies from multiple and complex point of views.

Because the study was conducted with men only, further research should include both women and men. Future research should integrate women’s experiences, especially their adherence to gendered ideologies, into the issues. The current study is also generally silent about how liberal women confront conservative men/husbands and how this influences their vulnerability to marital violence. Research based on qualitative methodologies might be imperative in order to understand this better. In addition, further research should address how women’s active microcredit participation is associated with resource and power imbalances between husband and wife.

Contributions, Implications, and Recommendations

In general, there has been a lack of empirical studies analyzing how women’s microcredit participation is practiced in relation to gendered ideology and male marital violence in rural Bangladesh. In the context of the dominant patriarchal gender ideology located there, the current study provides a good understanding of the way microcredit intervention has been practiced and under what conditions it can contribute to the marital well-being of women. This study also revealed that microcredit programs have largely been implemented on an axis of the traditional ideology in rural Bangladesh. In most of the cases, women’s loan-borrowing status could not ensure their income-earning microcredit participation. However, it has been indicated that, despite the high patriarchal social order prevalent in rural Bangladesh, women’s active microcredit participation can reduce their vulnerability to male marital violence.

The notable contribution of the current study is that it focused on married men in order to understand the relationship between gender ideology and marital violence. Within the background of women-focused microcredit intervention in a highly patriarchal society like rural Bangladesh, the husbands’ conservative ideology appears to be a negative influencing factor for women’s microcredit participation, socioeconomic status/rights, and marital well-being. These findings may have significant policy and practical implications, in context.

Based on this research, we have developed two main recommendations. First, women-focused microcredit intervention should not completely sidestep men; a focus on men’s gender ideology may also be worthy of study. Including men in microcredit programs could positively change their attitudes toward the socioeconomic roles, rights, and responsibilities of women. Women-focused microcredit organizations should particularly initiate programs for changing men’s patriarchal attitudes toward women. Before providing loans to married women, microcredit organizations may arrange frequent group meetings with the husbands in order to motivate them to be supportive of women’s extra-household socioeconomic enterprises. Dispossessed men’s credit needs should also be addressed by the microcredit organizations. Second, microcredit interventions should address patriarchal gender ideology by creating an environment where people may have a chance to rethink the importance of women’s socioeconomic roles and contributions. In other words, it is important to challenge the existing gendered ideology and to initiate a discussion within the community on people’s gendered roles, rights, and responsibilities. Community-level social action can be initiated in this regard. The pervasive nature of MVW appears to be socially operated by the patriarchal ideology prevalent in rural Bangladesh. Therefore, appropriate social policy and educational measures should be undertaken to address patriarchal gender ideology, the crucial factor in both women’s subordination to men and the pervasive nature of MVW in Bangladesh.

References

Agarwal, B. (2001). Participatory exclusions, community forestry, and gender: An analysis for South Asia and a conceptual framework. World Development, 29(10), 1623–1648.

Ahmed, S. M. (2005). Intimate partner violence against women: Experiences from a woman-focused development programme in Matlab, Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 23(1), 95–101.

Ahmed, S. M., Chowdhury, M., & Bhuiya, A. (2001). Microcredit and emotional well-being: Experience of poor rural women from Matlab, Bangladesh. World Development, 29(11), 1957–1966.

Aklimunnessa, K., Khan, M. M. H., Kabir, M., & Mori, M. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of domestic violence by husbands against wives in Bangladesh: Evidence from a national survey. The Journal of Men’s Health and Gender, 4(1), 52–63.

Anderson, K. L. (1997). Gender, status, and domestic violence: An integration of feminist and family violence approaches. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59(3), 655–669.

Atkinson, M. P., Greenstein, T. N., & Lang, M. M. (2005). For women, breadwinning can be dangerous: Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67(5), 1137–1148.

Baden, S., Green, C., Goetz, A. M., & Guhathakurta, M. (1994). Background report on gender issues in Bangladesh. BRIDGE (development–gender). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Bates, L. M., Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., & Islam, M. K. (2004). Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30(4), 190–199.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), & Statistics and Informative Division (SID). (2013). Report on Violence Against Women (VAW) Survey 2011. Dhaka: Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Bhuiya, A. U., Sharmin, T., & Hanifi, S. M. A. (2003). Nature of domestic violence against women in a rural area of Bangladesh: Implication for preventive interventions. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 21(1), 48–54.

Bograd, M. (1988). Feminist perspectives on wife abuse: An introduction. In K. Yllö & M. Bograd (Eds.), Feminist perspectives on wife abuse (pp. 11–26). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2009). Quantitative data analysis with SPSS 14, 15 and 16: A guide for social scientists. New York: Routledge.

Cain, M., Khanam, S. R., & Nahar, S. (1979). Class, patriarchy, and women’s work in Bangladesh. Population and Development Review, 5(3), 405–438.

Dobash, R.E., & Dobash, R.P. (1977–78). Wives: The appropriate victims of marital violence. Victimology, 2(3–4), 426–442.

Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. P. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. New York: Free Press.

Frazier, P. A., & Tix, A. P. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 115–134.

García-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2005). WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Goetz, A. M., & Gupta, R. S. (1996). Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World Development, 24(1), 45–63.

Goldson, A. C. (2005). Patriarchal ideology and frequency of partner abuse among men in batterer treatment groups. Miami Beach: ETD Collection for Florida International University.

Hadi, A. (2000). Prevalence and correlates of the risk of marital sexual violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(8), 787–805. doi:10.1177/088626000015008001.

Hadi, A. (2001). Promoting health knowledge through micro-credit programmes: Experience of BRAC in Bangladesh. Health Promotion International, 16(3), 219–227.

Hadi, A. (2005). Women’s productive role and marital violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Violence, 20(3), 181–189. doi:10.1007/s10896-005-3654-9.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th [Global Edition] ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall.

Hartmann, B., & Boyce, J. K. (1983). A quiet violence: View from a Bangladesh village. London: Zed Books.

Hossain, F. (2002). Small loans, big claims. Foreign Policy, 132, 79–82.

Jahan, R. (1994). Hidden danger: Women and family violence in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Women for Women.

Kabeer, N. (1990). Poverty, purdah and women’s survival strategies in rural Bangladesh. In H. Bernstein, B. Crow, M. Mackintosh, & C. Martin (Eds.), The food question: Profit verses people? (pp. 134–147). London: Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Kabeer, N. (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 29(1), 63–84.

Karim, K. M. R., Emmelin, M., Resurreccion, B., & Wamala, S. (2012). Water development projects and marital violence: Experiences from rural Bangladesh. Health Care for Women International, 33(3), 200–216.

Karim, K. M. R., & Law, C. K. (2013). Gender ideology, microcredit participation and women’s status in rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(1/2), 45–62. doi:10.1108/01443331311295172.

Kidwai, R. (2001). Domestic violence in Pakistan: The role of patriarchy, gender roles, the culture of honor and objectification/commodification of women. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Alliant International University, Los Angeles, CA.

Kim, J. C., Watts, C. H., Hargreaves, J. R., Ndhlovu, L. X., Phetla, G., Morison, L. A., … & Pronyk, P. (2007). Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. American Journal of Pubhc Health, 97(10), 1794–1802.

Koenig, M. A., Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. B., & Mozumder, A. B. M. K. A. (2003). Women’s status and domestic violence in rural Bangladesh: Individual- and community-level effects. Demography, 40(2), 269–288.

Kramarae, C. (1992). The condition of patriarchy. In C. Kramarae & D. Spender (Eds.), The knowledge explosion: Generation of feminist scholarship. London: Teachers College Press.

Kroska, A. (2007). Gender ideology and gender role ideology. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology [electronic resources]. Malden: Blackwell Pub.

Lerner, G. (1986). The creation of patriarchy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mahjabeen, R. (2008). Microfinancing in Bangladesh: Impact on households, consumption and welfare. Journal of Policy Modeling, 30(6), 1083–1092. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2007.12.007.

Manderson, L., & Mark, T. (1997). Empowering women: Participatory approaches in women’s health and development projects. Health Care for Women International, 18(1), 17–30.

Maxim, P. S. (1999). Quantitative research methods in the social sciences. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meade, J. (2010). An examination of the microcredit movement, http://www.connexions.org/CxLibrary/Docs/CX6992-MeadeMicrobank.htm

Naved, R., & Persson, L. Å. (2005). Factors associated with spousal physical violence against women in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning, 36(4), 289–300.

Salt, R. J. (2010). Exploring women’s participation in a U.S. microcredit program. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(3), 270–277.

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., & Badal, S. H. (1998). Men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh: Undermined or exacerbated by microcredit programmes? Development in Practice, 8(2), 148–157.

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., Riley, A. P., & Akhter, S. (1996). Credit programs, patriarchy and men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine, 43(12), 1729–1742.

Schurmann, A. T., & Johnston, H. B. (2009). The group-lending model and social closure: Microcredit, exclusion, and health in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 27(4), 518–527.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1973). A short version of the Attitudes toward Women Scale (AWS). Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 2, 219–220.

SPSS Inc. (2007). PASW statistics 16, release version 16.0.1. Chicago: SPSS: An IBM Company.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Develoyrnent and preliminary psycometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316.

Vittinghoff, E., Shiboski, S. C., Glidden, D. V., & McCulloch, C. E. (2005). Regression methods in biostatistics: Linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. New York: Springer.

World Bank (June 2013). Bangladesh Poverty Assessment: Assessing a Decade of Progress in Reducing Poverty, 2000–2010 (Bangladesh Development Series Paper No. 31). Dhaka, Bangladesh: The World Bank Office.

Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

Yllö, K. A. (2005). Through a feminist lens: Gender, diversity, and violence: Extending the feminist framework. In D. R. Loseke, R. J. Gelles, & M. M. Cavanaugh (Eds.), Current controversies on family violence (2nd ed., pp. 19–34). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply appreciative for the cooperation of Mr. Sajedur Rahman, Mr. Partha Sarathi Mohanta, Mr. Golam Muzahid, Ms. Sajanur Khatun, and Mr. Nur Hossain during the fieldwork. The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors are also thankful to the anonymous reviewers of this article for their constructive comments and suggestions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karim, K.M.R., Law, C.K. Microcredit and Marital Violence: Moderating Effects of Husbands’ Gender Ideology. J Fam Viol 31, 227–238 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9763-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9763-1