Abstract

A community-based research (CBR) study was carried out with single mothers who had left abusive relationships in order to better understand their experiences of finding a sustainable livelihood after experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). Using the photovoice method and guided by the Sustainable Livelihoods (SL) framework, participants took photographs representing their experiences of violence through their transition to single motherhood and beyond. The findings reported through their photos and stories reveal an often long and arduous journey amidst the complexity of single parenting and the effects of violence. As with many people living on a low income, they incorporated creative strategies to survive and enhance their own and their children’s quality of life. Important areas for change are suggested through aspects of the SL framework and primary prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to a pattern of physical, sexual, and/or emotional violence by an intimate partner in the context of coercive control (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). It is one of the major health and human rights problems of our time with estimates of one in three women affected worldwide (Davis 2002a; World Health Organization [WHO] 2005). Leaving relationships in which they have experienced IPV can push many women into poverty. This lowered economic status results from ongoing physical and mental health effects of IPV, further abuse, debt, and costs of moving away and staying safe (Wuest et al. 2003) with loss of material and fiscal assets. Single mothers have the added challenge of the former partner’s continued intrusion through custody, access, and child support conflicts (Wuest et al. 2006). Literature reveals the vulnerability of single mothers after leaving abusive partners, yet, knowledge of women after leaving has often focused on deficits with little known about their strengths or assets, particularly with regards to employment.

While employment itself provides no promise of a living wage, many single mothers want to work to improve their health and quality of life as well as that of their children. We knew little about the livelihood aspirations of women who have left abusive partners, the assets they have and need, and employment strategies they use to sustain their families in the short term and into the future.

Geographical and Employment Context

This study was carried out in the Greater Moncton area of New Brunswick, Canada that includes the three communities of Moncton, Dieppe, and Riverview. In 2011, these two cities and one town had a combined population of 140,500 (Statistics Canada 2012). In Moncton in 2006, there were 5, 815 single parent families of which 4, 845 were female headed (83.3 %) and 975 male headed (Statistics Canada 2006). In Canada in 2009, single mothers earned on average $47,700 compared to $65,400 for single fathers (Statistics Canada 2009). Researchers have examined part time employment noting that Canadian women in 2011 chose part time work 20 % of the time due to their own illness (3.1 %), caring for children (13.3 %), and other personal/family responsibilities (3.6 %) (Statistics Canada 2011b), whereas the total for men was 6.4 %, including 3.6 % for their own illness, 1.3 % caring for children, and 1.5 % for other personal or family responsibilities (Statistics Canada 2011a). In 2010, females in New Brunswick lost an average of 11.2 days due to illness and disability (Statistics Canada 2010b) whereas men lost 7.4 (Statistics Canada 2010a). These statistics show wide gender differences in single household, work, and income patterns and the reasons why women and men might choose part time over full time employment that then impacts their ability to achieve a sustainable livelihood.

Study Purposes

The overall aim of this inquiry was to explore and describe single mothers’ transitions to a sustainable livelihood after leaving an abusive partner. More specifically, to identify their goals for economic sustainability, their strengths and assets in the transition, socio-cultural factors that hinder or facilitate the transition and that increase or decrease their vulnerability, and appropriate supports for achieving a sustainable livelihood.

Theoretical Framework

The Sustainable Livelihoods (SL) framework includes an upstream antipoverty approach to community economic development (See Fig. 1), guides the examination of factors that affect people’s livelihoods and the relationships between them, and helps identify more appropriate entry points for interventions (Department for International Development DFID 1999; Murray and Ferguson 2002). A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets, and activities required for a means of living, and is sustainable “when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks and maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets” now and in the future (DFID 1999, section 2.4).

An essential characteristic of poverty is a limited ability to accumulate assets (Murray and Ferguson 2002). The Livelihood Assets Pentagon frames assets as evolving forms of capital that people are able to draw upon to achieve their livelihood goals: human capital includes skills, knowledge, health, and ability; social capital implies social networks and trust relationships; physical capital is infrastructure such as transportation, housing, and information; financial capital refers to all financial resources (savings and income); while natural capital refers to available natural resources. Natural capital was not included in the study as it was not relevant.

The Vulnerability Context includes external factors, largely outside people’s control, that have a direct impact on assets and options. Three areas of influence are shocks (economic, health), trends (more contract work, fewer benefits), and seasonality (time-limited work such as farming and fishing, price fluctuations). Policies, Institutions, and Processes are social and cultural institutions, organizations, policies, and legislation that control access to capital and influence strategies. Livelihood Strategies refer to the dynamic way people undertake various activities to achieve their livelihood outcomes. Livelihood Outcomes are people’s aspirations with respect to present and future livelihood and could include higher income, increased well-being, food security, and reduced vulnerability (DFID 1999; Murray and Ferguson 2002).

This research was also informed by a feminist perspective that views IPV and socio-economic status (SES) as issues of power, control, and oppression (Varcoe 1996, 2008). Violence against women “does not occur spontaneously but is linked to and embedded in the legal/social mechanisms and systems that inhibit and erode women’s equality rights” (Tutty 2006, p. viii).

IPV, Employment, and the SL Framework

The Vulnerability Context

Within the SL framework, we viewed IPV as a pervasive and unrelenting shock that can escalate over time, forcing many women to leave their partners and abandon homes, belongings, jobs, and social supports (Lutenbacher et al. 2003; Merritt-Gray and Wuest 1995). Unfortunately, the violence often intensifies after leaving, particularly for mothers faced with child custody, visitation, and child support, further increasing their vulnerability by putting their safety at risk (Davies et al. 2009; Fleury et al. 2000; Wuest et al. 2003). IPV also targets women’s efforts to establish independence by eroding their sense of competence and ability to trust and interferes with their access to relationships and resources (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2005).

While disclosure of IPV has become more socially acceptable, survivors continue to feel stigmatized with feelings of revictimization when convincing others of their experience (Lempert 1996; Wuest and Merritt-Gray 1999; Wuest et al. 2003) and face many barriers to accessing appropriate services (Kulkarni et al. 2010). Despite this, the process of leaving an abusive relationship can enhance women’s sense of control over their lives (Anderson and Saunders 2003).

Livelihood Assets

The asset pentagon is at the center of the model and situated within the vulnerability context. “Assets are both created and destroyed as a result of the shocks, trends, and seasonality of the vulnerability context” (DFID 1999, section 2.3, para 11).

Human Capital

The health impact for survivors of IPV is far reaching and includes both acute and chronic physical and mental health problems. Particularly intrusive and persistent are chronic pain, insomnia, hearing loss, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and bowel disturbances (Campbell 2002; Ford-Gilboe et al. 2006; Humphreys et al. 2010; Plichta 2004; Samuels-Dennis et al. 2010; Wuest et al. 2009). These influence a woman’s capacity to labour at home, work, or school and affect relationships with family and friends (Anderson et al. 2003; Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement for Women [CRIAW], 2002; Kimerling et al. 2009; Macy et al. 2005; WHO 2005; Wuest et al. 2003).

Women can become exhausted as a result of the attacks as well as the vigilance needed to survive prolonged IPV (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2005). Additionally, IPV often erodes women’s self-efficacy and confidence leading them to question their abilities to be successful. “Employment not only increases a woman’s financial well-being but it can also increase her social capital and social networks” (Gibson-Davis et al. 2005, p. 1152) with added gains in “mental respite” and “purpose in life” (Rothman et al. 2007, p. 140). However, an unstable work history, combined with pervasive health problems after leaving, can interfere with women’s ability to benefit from employment (Walker et al. 2004). The costs of health care are significantly higher than in non-abused women with increased use of emergency rooms, primary care, and medications that only add to the financial burden (Bonomi et al. 2009).

Social Capital

This refers to social resources that are both a means to achieving livelihood objectives and assisting in coping and recovery from shocks and insecurity (DFID 1999). Social support is seen as a critical protective factor in developing resiliency and other coping skills (Davis 2002b; Staggs et al. 2007). Isolation and control by abusive partners limits women’s social connections and leaving often compounds the isolation, especially if the departure requires relocation (Walker et al. 2004). The legacy of IPV and repeated violations of trust complicate the survivor’s ability to effectively engage and build meaningful connections with both formal and informal supports (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2005).

Physical Capital

Especially important for single mothers after leaving are safe and secure housing, basic household goods, utilities, transportation, and childcare (Anderson and Saunders 2003); however, many women begin their new life with little or no physical capital. Single mothers with a history of IPV face an additional challenge of needing to be safe from former abusers (Raphael 1999; Tolman and Rosen 2001). Rollins et al. (2012) found clear linkages between housing instability, health, and IPV and noted that unstable housing situations are as important to the development of mental health issues for women after leaving abusive relationships as is the severity of abuse. Leaving is also more difficult in the absence of other physical capital such as timely and accurate information concerning their rights, resources, and eligibility for programs and services (Davis 2002a).

Financial Capital

Even without the vulnerability context of IPV, women-headed households often experience dramatic downward mobility in income and social status following separation and divorce (Davies et al. 2009; Lorenz et al. 1997). Lindhorst et al. (2007) stressed the need for policy makers to recognize the long-term impact of IPV on economic sustainability. Furthermore, Crowne et al. (2011) found that employment instability can continue up to six years after leaving an abusive relationship. Single parents are 1 of 5 high-risk groups for consistent low income in Canada (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada 2008), with 51.6 % of women-headed families living in poverty (Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women CRIAW 2005) and 1 in 3 female single parents in New Brunswick living below the poverty line (Advisory Council on the Status of Women 2010).

In order for women to remain out of an abusive relationship, access to economic resources is critical (Anderson and Saunders 2003; Kwesiga et al. 2007; Moe and Bell 2004; Pennington-Zoellner 2009). Recognizing that sustainable employment is an important and socially acceptable way to build financial assets and security, limited structural support for low income single mothers, combined with risks to their own and their children’s well-being, may mean that responsible parenting involves a decision to return to social assistance (Bancroft and Vernon 1995; Bell 2003; Mullan-Harris 1996; Scarbrough 2001).

It is evident that the sections of the asset pentagon are very interdependent; a change in one can greatly influence another. This means that a loss in one area could seriously undermine other assets. On the other hand, actions to build or enhance assets can also have positive effects on other forms of capital that could increase women’s livelihood sustainability.

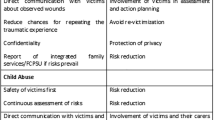

Policies, Institutions, and Processes

Women who have left an abusive relationship need a wide range of services to remain free, sustain their families, and deal with the multiple challenges faced by themselves and their children. When positive, these services can be empowering (Anderson et al. 2003; Merritt-Gray and Wuest 1995; Perrin et al. 2011) yet they are often fragmented, poorly coordinated, heavily bureaucratic, vary across sites, and do not deal with women’s complex needs in a comprehensive way (Allen et al. 2004; Cole 2001; Kulkarni et al 2010; Zweig et al. 2002). These shortcomings have “direct consequences for women’s safety and well-being” (Allen et al. 2004, p. 1016).

Some workplaces have created provisions such as Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) and flexible work schedules, yet there is little research on how EAPs respond to IPV (Pollack et al. 2010). With the high costs of IPV to employers in terms of medical expenses, turnover, lost productivity, and absenteeism, workplaces may choose to address the issue by terminating women’s employment rather than implementing supportive policy and programs (Moe and Bell 2004; Perrin et al. 2011). Swanberg et al. (2012) found that only about 15% of employers surveyed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2006 had a workplace violence policy relating to domestic violence. Several researchers note the difficulty of single mothers maintaining employment with the high cost, or lack, of structural supports (Butler et al. 2008; Edin and Lein 1997). Within work environments, disclosure of abuse can reduce negative effects and therefore assist in maintaining employment, yet this disclosure is most likely to occur when there is evidence of appropriate employment support (Swanberg et al. 2007).

Livelihood Strategies

Single mothers use various strategies to improve income and quality of life after leaving and, while much is known about the barriers they face, little is known about how they overcome these. Tutty (2006) stressed that education, upgrading, and training programs for women are particularly important in helping them leave especially when the abuser has been the primary family wage earner. Kneipp’s (2002) study revealed that lack of health insurance is the main reason women leave work and return to welfare.

Battered women, who experience ongoing harassment after leaving an abusive relationship, may have multiple episodes of short-term, entry-level employment, or underemployment, and with few or no health benefits or job security (Moe and Bell 2004; Staggs et al. 2007; Staggs and Riger 2005). Strategies used to “break through their current economic ceiling” involve many risks as they enter job retraining, return to school, fight for child support, relocate, or increase their debt load; all requiring a considerable degree of situational stability, self-efficacy, and confidence (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2005, p. 489).

Livelihood Outcomes

Increased well-being and better income are two important outcomes that are relevant to this study, although outcomes are unique for each person. The effects of IPV appear to be serious impediments to employment and self-sufficiency (Butler et al. 2008; Gennetian 2003; Murray and Ferguson 2002; VandeWeerd et al. 2011) while “waged work, increased financial autonomy, educational and vocational development can aid in healing (of IPV) if done in a safe, supportive context (Brush 2000, p. 1044). Paid employment is generally associated with better health and well-being for women (Anderson et al. 2003; Samuels-Dennis 2006). Klumb and Lampert (2004) consolidated 50 years of research on employment and women’s health and determined that employed women have improved self-efficacy and social affirmation along with lower mortality rates compared to women who are not employed. It appears that employment may decrease women’s vulnerability by enhancing human, social, and financial capital.

Methods

Photovoice, as one method of community-based research (CBR), was chosen for the way the process involves and engages participants as co-researchers in an active and collaborative process of inquiry. Photovoice is founded on principles of health promotion, education for critical consciousness, feminist theory, and a community-based approach to documentary photography (Wang 1999; Wang and Burris 1997; Wang et al. 1998). Cameras are provided for participants to record everyday life events or representations of the study focus that lead to discussion and reflection on the meaning of the images. The photos and the accompanying stories assist in sharing people’s expertise with those who have the power to form and inform policy. The photovoice acronym VOICE stands for Voicing Our Individual and Collective Experience and this approach works at a grassroots level to determine what is important to a community.

Recognizing and appreciating the importance of community stakeholders, we were joined by Moncton Head Start (programs for low income families), Moncton’s transition house Crossroads for Women, and Support to Single Parents. We were also guided by a Community Advisory Committee, that included representatives of the community partners, others interested or working in areas of poverty reduction, employment, education, or domestic violence as well as two participants from an earlier study with photovoice and single mothers (Duffy 2010). This committee met every six months with the academic researcher and research assistant. Members assisted with recruitment, provided input to the process, and contributed ideas for dissemination.

Ethics and Safety

Approval was obtained from the University of New Brunswick (UNB) Nursing Ethics Committee and the UNB Research Ethics Board. Safety protocols similar to those used by colleagues in previous research with women and IPV were used. Following recruitment and informed consent, participants received training on the SL framework, photovoice method, basic camera skills, and issues of ethics, power, and privacy around community photography. Digital cameras were provided and belonged to the women at the end of the project. In addition, they received a $15.00 honorarium at each meeting with childcare and transportation costs covered. Consent around shared ownership and use of photos was established initially and was ongoing. Participants chose which photos to make public and were made aware of their rights around withdrawing consent without negative consequences.

Sample

Inclusion criteria included; 1) being a single mother living in Greater Moncton, 2) age 18 and older, 3) English speaking, 4) having left an abusive relationship with an intimate partner at least one month ago, 5) having at least one dependent child living with them, and 6) willing to commit to participate for up to two years. Recruitment was through purposive sampling assisted by the three community partners with posters at each site and through their direct contacts with clients individually or in group sessions. The same advertisements were placed in public areas where women in post abuse situations might attend such as Victims Services. Partners received an orientation and recruitment package that included study information, contact permission forms for those who wished to be called, and a contact card to phone directly. As calls were received, the PI or the Research Assistant followed a flow chart to ensure inclusion criteria were met and that participants were fully informed. Safety issues were also reviewed and a one-on-one meeting was held with participants when possible.

Consistent with feminist methodology around representation of diverse perspectives and experiences, the women varied in culture (both Anglophone and Francophone), education (from Grade nine to one participant with a masters degree), age (18 to over 40), time out of relationship (two months to 15 years) and employment. Eight women were working full time, four working part time with two holding more than one part time position, eight were unemployed including two taking upgrading courses, and one on maternity leave. Monthly income ranged from $500 to $4000, with an average of $1368.00 or $16,416 annually. A 2012 provincial report on child poverty noted that a single parent with two children working full time at minimum wage would earn $15,000 below the poverty line (Human Development Council 2012).

Wang (1999) suggests 7 to 10 people as an appropriate photovoice group size. We recruited 20 women who were subsequently divided into two discussion/analysis groups; either a morning group at a partner agency or an evening group at the university to enable attendance. This number allowed for a feasible project in case of attrition.

Data Collection

Monthly photo assignments were based on sections of the SL framework with a one or two page handout prepared for each component that was reviewed at the end of the analysis discussion in preparation for the next month’s photo shoot. Participants were asked to photograph and keep field notes on their experiences in each of four areas of livelihood assets (human, physical, social, and financial capital), process and structures, and livelihood outcomes and strategies. Discussions were audio taped and transcribed to document the issues, themes, and stories emerging from the individual and group dialogue. Photographing continued until the participants agreed that the photos accurately represented their issues around the various sections of the SL framework and their recommendations for change.

Data Analysis

In photovoice, analysis is concurrent with data collection. As the women arrived at each meeting that lasted about three hours, their photographs were downloaded from their camera to a computer and projected on a screen. We followed the original three steps of analysis according to Wang and Burris (1997): 1. Selecting—Participants choose two or more of their photographs that have the most significant meaning. 2. Contextualizing—Participants describe the meaning of their images to group members guided by the photovoice acronym SHOWeD (S—What do you “See” in this photo? H—What is “Happening” here? O—How does this relate to “Our lives”? W—“Why” does this exist? and D—What can we “Do” to address this issue? Group members could ask questions and add to the discussion, helping to expand meaning and understanding. 3. Codifying—Participants identified issues or themes that emerged (Wang et al. 1998) and chose the photos and stories to be made public.

Once the two groups completed their respective photography and analysis sessions, they came together to share and integrate these findings. Through various meetings, the research team (academic researcher, research assistant, and the women) examined the assignment categories (components of the SL framework) and began to consider which photos, from all available, best described their experiences. This resulted in an adaptation of the SL framework we called the Study Process and Outcomes model (See Fig. 2) that describes their journey from IPV, important assets (capital) to their achieving a sustainable livelihood or not, and areas the group decided were priorities for change. Eventually, out of over 1000 photographs, 134 were chosen by the team to represent areas of the model and then a graphic designer integrated captions with photos. Final products for dissemination were developed collaboratively with participants and later with members of the Community Advisory Committee. Over a two and a half year period, each group met 14 times and then worked together for approximately 10 more sessions.

Findings

The findings are presented here according to sections of the Study Process and Outcomes Model (Fig. 2) along with examples of the photographs. A slide show of all 134 photos with section headings can be viewed at http://www.unb.ca/research/projects/photovoice/phase-two/research-findings.html.

The Vulnerability Context

Participants were clear in how violence had helped define and shape their present life. While IPV was seen as a major “shock” in the Vulnerability Context of the SL framework, the women’s vulnerability continued throughout the leaving process and afterwards as they began to care for their families in new contexts and is expressed under the following sections.

IPV

Although this study was with women who had left abusive relationships, all participants stressed the need to begin with the abuse experience. While they used some metaphor and analogy to depict the violence, such as in the photo with the eggshells (See Fig. 3), four of them thought this wasn’t enough and they came together to act out and photograph some of their experiences with a volunteer male “abuser.” This was a difficult process of re-living the abuse, but they insisted these pictures were the only way people could really begin to see and understand what they had experienced.

Participants defined abuse as “Anything that takes away our dignity” and used words such as hopelessness, trapped, afraid, a sick feeling that never goes away, and no way out. They described lives filled with fear, threats, intimidation, isolation, control, and cruelty involving physical, emotional, and/or sexual attacks often with a weapon.

Single Parenting

Subsequent to leaving the abusive relationship, the women had experienced and continue to experience high-level demands of single parenting. They are overwhelmed with the responsibility of providing basic needs to a reconstituted family (see Fig. 4) as they also recognize all they are missing due to limited income, such as recreation, travel, understanding, and support from family members and agencies. While struggling for dignity and accessible services, healing needs to occur in order for them and their children to attain some quality of life.

Livelihood Outcomes

The dreams and aspirations of the women include such basic things as a small house, reliable transportation, peace and serenity, safety, ability to adequately care for their children, and enough income to be comfortable (see Fig. 5). Unfortunately, most of these are out of their reach no matter what they do. This is the result of several things including their level of education and skills, health challenges, the energy and time required for child care and healing from IPV, market trends such as increasing contract and part time work with few if any benefits, and the requirement by many local employers for bilingualism.

Livelihood Strategies

Existing on a limited income, and with sustainable employment only a dream, they did many things to eke out a living. Some of these were income-generating such as making and selling crafts, renting space in their homes, and bartering for goods and services. Many others were income-conserving activities that included keeping old, dilapidated furniture; using food banks and second hand clothing depots; setting goals; budgeting; careful shopping and creative cooking with often nearly bare cupboards; moving back with parents; doing without heat and electricity for periods in the winter; and buying lottery tickets in the hopes of a better life in the future (see Fig. 6). Several made great sacrifices in order to attend courses and university in hopes of later finding a good job. Others sought social support and networking to improve their asset base, and improving or maintaining their health in order to work and care for their children.

Livelihood Assets

Many aspects of the previous sections relate to forms of capital that are critical to whether one has or is able to achieve a sustainable or unsustainable livelihood. Though sustainability is shown as a dichotomy in the model (Fig. 2), in reality it is more a continuum with each person having unique “amounts” of assets at different points in time. As mentioned earlier, these forms of capital, while depicted as separate sections in the SL framework, influence each other and are very much interrelated and overlapping. Therefore, it can be difficult to know which one might have occurred first to influence another.

Human Capital

A major component of this section involves health and wellness with clear connections to financial capital. One photo is of two medicine bottles with the caption Be Happy. The photographer described how others told her to “Just take Prozac”—implying that there is an easy way to get over her depression. She recognized at least part of the reason for her depression and asked, “Do they think Prozac is going to pay the bills and put food on the table?” Participants told stories of their attempts to find healing for themselves and their children through appointments with doctors, specialists, and counsellors and the need for frequent testing for chronic illnesses while dealing with inflexible employers not allowing time off for health-related visits. Even if a woman met expected work quotas, she was denied salary increases or promotions because she did not work full time hours. The stress of living with financial uncertainty and daily pressure to meet basic needs means that health is further compromised as is demonstrated in one photo of pills and healthy food that reads: Health and finances are related; Better health and nutrition means less medications.

During the study, the women were encouraged to evaluate strengths as well as challenges. They recognized their strong organizational skills, the growth that had occurred since leaving, and their efforts in continuous learning in order to keep up with rapid change. Figure 7 highlights their organizing abilities while the book in the center shows that in the midst of considerable busyness and responsibility, healing is very often a “do it yourself project.”

Financial Capital

Critical to health, quality of life, and a sustainable future is having stable and adequate income that is properly managed. Long recognized as one of the most important determinants of health, financial security is the most fleeting asset for these women (see Fig. 8). Healing from the abuse and its many effects while caring for children often results in limited opportunities for full time employment with benefits. In our bilingual province it can be very difficult for a unilingual person to find a full time job, especially when public services require provision in both languages. There are limited opportunities for adults to study language and the cost (in money and time) is beyond what most of the women have.

Social Capital

Another vital area that influences the quality of a transition from IPV to single motherhood is social support (see Fig. 9). Community agencies are essential for safety, training, building resiliency, and helping with physical resources. However, it was noted that assistance through food banks or soup kitchens is demeaning, as it makes one’s poverty public. While faith communities are important and supportive for some, others have reported experiencing judgmental attitudes and were offered help with religious strings attached. Old and new friends often filled the gap when the women had to move away from family and friends to keep safe or when relatives would not accept the reality of the abuse experience. Caring, responsive employees in such areas as police, Victim Services, and the courts made a difference in how these systems were navigated and whether or not the outcomes were positive.

Physical Capital

Transportation and housing emerged as critical assets to well-being and employment. Many working other than regular daytime hours found accessibility limited with bus schedules developed for consumers, not employees. Cost of vehicle repairs, fuel, and insurance also meant that car keys were often left hanging (see Fig. 10). Finding and keeping a job is nearly impossible without reliable means of transportation. Women who have left abusive relationships also need safe, affordable housing, yet often could only afford substandard accommodations in less than desirable neighbourhoods. Heating and electricity costs also impacted quality of life, particularly given that winter temperatures in this geographic region often stay well below the freezing point for long periods. Furthermore, not having a personal computer limits job searching and preparation of resumes. One positive physical asset is the public library for accessing reading and video materials as well as free Internet.

Opportunities for Change

The following recommendations for change, which emerged from discussions in the combined group, are organized under three categories. While each woman had preferences specific to her personal situation, the following are those that everyone agreed were important. The first two categories are taken from the SL framework: 1) protecting, building, and maintaining livelihood assets and 2) transforming structure and processes. Strategies within these categories often influence each other. For example, obtaining a good job, if available, is difficult without affordable childcare and transportation.

Protecting, Building, and Maintaining Assets

Human Capital

Early teaching and modeling of healthy relationships for males and females; early learning to set boundaries and respect for others’ boundaries; raising children with good self-esteem and social intelligence; opportunities for self-development; work-appropriate education and training in official languages; and good physical and emotional health with access to a broad range of affordable western and alternative health services.

Financial Capital

A living wage with benefits for everyone; countering the culture of the working poor who may choose to move from employment to income assistance programs in order to have more benefits; early education in budgeting and investing; access to savings and pensions to reduce vulnerability to violence and poverty; and, since leaving IPV often involves bankruptcy, access to credit may be needed to start a new life (see Fig. 11).

Social Capital

Social support and networks include friends, families, neighbours, peer mentors, and caring agencies and institutions. Women are often blamed for leaving abusive relationships and family or friends may not accept that the abuse occurred. Therefore, effective interventions from community agencies are even more critical when more personal level supports are missing.

Physical Capital

Recommendations here focus on accessibility including safe, healthy, and affordable housing and neighbourhoods; reliable and affordable public transport that serves shift workers; recreation for physical and emotional health and healing (see Fig. 12); and appropriate job training and equipment for sustainable employment.

Transforming Structures and Processes

Along with strengthening personal and physical assets, it is also critical to examine and work for change around many of the larger policies and practices in workplace and government settings.

Business Practices

Workplace support for women experiencing IPV and post abuse assistance including comprehensive employee assistance programs; family friendly and flexible work places (see Fig. 13); benefits for both part time and full time positions; and equal employment opportunities for men and women.

Laws and Policies

An increase in mental health services and accessibility to alternative health care; sustainable level of employment assistance throughout the healing process; appropriate educational strategies for sustainable employment; laws that promote a living wage for all; enacting pay equity laws and eliminating gender wage gaps; universal day care (see Fig. 14); and training respectful and caring public employees who do not discriminate.

Legal and Court Services

Access to domestic violence court systems for all with adequate numbers of social workers; continued IPV training for police and other interventionists; and enhanced collaboration between court agencies to ensure seamless and just outcomes of rulings.

Community Resources

A key recommendation involves a single entry point for IPV services (see Fig. 15) along with improved interagency collaboration to avoid duplication and gaps in provision. As the participants spent time together over the two years, they increased their knowledge of resources and often became supports for others, even creating a bartering system and sharing housing. However, it was obvious during their many discussions that each experience of leaving abusive relationships and finding appropriate resources was different and at times seemed to very much depend on “luck” or finding the right person to help. For example, women leaving abusive relationships often require frequent contact with the criminal justice system, which can be complex to navigate as well as lacking in appropriate and timely services (Letourneau et al. 2012). Therefore, while work continues on prevention of societal and family violence, a critical recommendation to mediate effects is for a single entry point for services and resources so that the journey out of IPV is a more effective, efficient, and supportive process for women and their children.

Primary Prevention of Violence

We added this third category of change to our model, noting the critical need for heightened attention on prevention of IPV and other forms of societal violence such as bullying and harassment. More specifically, there is a need to challenge media messages and images that make violence acceptable. Figure 16 represents one participant’s reminder to herself to “never again” be in an abusive relationship. A critical area of prevention is eradication of poverty, which is increasingly challenging as the gap between rich and poor widens in most areas of the world. Elimination of all forms of gender inequality is essential to enhancing women’s economic and social opportunities.

Boundaries: This symbol against violence is on my doorframe; it gives me strength. I got out of a bad situation and this reminds me “Never again.” These symbols should be in every home, school, and workplace—to represent that as a society we support zero tolerance of all forms of societal and family violence and abuse, including bullying in schools, workplaces, and neighbourhoods

Limitations

This study was carried out with a group of English-speaking participants due to the language of the academic researcher and therefore excluded women who might only speak French. While some participants were from the Francophone community, their command of English was at a high level, and it is not clear if there would be differences between the two official language groups. Future research should include both groups with comparisons made; as it is always preferable to discuss personal and sensitive topics in one’s first language. Women in rural areas were also not included and there may be differences; certainly in access to often centralized resources. The purposeful, yet convenience sampling through the partner agencies meant that women from other cultural groups may not have been reached, such as if we had specifically worked with the local multicultural association.

One challenge was the complexity of the SL framework and finding ways to make it understandable for participants. In addition, the study time frame of over two years, while building community and ownership of the project, presented a long-term commitment. As such, some initial participants were unable to complete the project. Some reasons for this included mental health and addiction issues, changes in interpersonal relationships (i.e., marriage), and new employment responsibilities.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study has offered a unique insight into the transition from IPV to single motherhood by analyzing participant photographs through individual reflections and group dialogue. The SL framework provided a multi-contextual guide for the women to photograph areas important to their experience of IPV, including leaving the abusive relationship, surviving the aftermath, and approaches to poverty reduction (where possible), based on various livelihood outcomes and strategies. One strength in this approach to development is the focus on assets as units of capital. Ford-Gilboe et al. (2009) found that women’s personal, economic, and social resources mediated the physical and mental health effects of partner violence after leaving. Far too often, we examine poverty through a deficit lens while Pyles and Bannerjee (2010), who use the language of capabilities, say it is a social justice approach that recognizes each person’s entitlement to reach their potential and it is the responsibility of governments to ensure this occurs.

The vulnerability context of the SL framework is an important concept that reminds us of the many environmental issues we often have little control over. In this study, we focused on IPV as a key shock. However, trends are also an important component. High unemployment rates, underemployment, and hiring practices, such as moves to more contract and part time work, also affect ability to achieve a sustainable livelihood. A third aspect of the vulnerability context is seasonality. An example is employment in school systems where workers are without salary for the summer months. Fluctuating food and fuel prices throughout the year are also seasonality factors. Most of us have little control over these except the choice of whether or not to purchase them. As shown in Fig. 17, choices are important and the ability to choose wisely is directly related to financial assets. In addition to influencing their family’s quality of life, achieving economic security through a sustainable livelihood can also increase women’s choices with regards to a romantic partner (Pennington-Zoellner 2009).

This research has revealed the complexity of women’s journeys from IPV and the challenges they face while attempting to heal and reconstitute a healthy family system. VandeWeerd et al. (2011) note the intricate relationship between IPV and employment, with women facing a “multiplicity of demographic…and mediating factors” as well as many direct and indirect barriers (p. 149). With employers being slow in taking responsibility for addressing IPV, strong and supportive state and national level policies are needed to increase workplace accountability (Swanberg et al. 2012).

Finding and maintaining employment in this complexity, along with societal employment trends, is challenging for all and impossible for some. Riger and Staggs (2004) remind us that in order to understand the various responses and choices women make around employment, we need to focus on multi-level contextual issues, not only individual characteristics, since “women’s lives are embedded within an interpersonal and institutional framework” (p. 982). Multilevel actions for change have been suggested that require involvement of governments, communities, workplaces, families, and individuals in the development of societies with zero tolerance of all forms of violence, while mediating the effects of IPV. As identified by the participants in this study, women who have experienced IPV need many supports if they are to have any chance of obtaining a sustainable livelihood and these include affordable housing and child care, sustainable employment with benefits, caring and responsive systems, and safe living and working environments (Bell 2003; Katula 2012; Pyles and Banerjee 2010). Prevention, as part of a comprehensive approach, involves reducing risk factors for violence that include “poverty, stress, substance abuse, depression, and history of child abuse” (Shobe and Dinemann 2008, p. 185).

The physical, emotional, social, and financial costs of IPV to individuals, families, and society, while difficult to measure, are staggering. With violence against women and girls commonly accepted in many societies (WHO 2005), multi-level strategies are needed that normalize non-violence as a way of life for all. An important component of any approach is addressing gender inequality since, “Violence against women is both a consequence and a cause of gender inequality” (WHO 2005, p. viii). Davies et al. (2009) remind us of the need to recognize and address the relationship between abuse and gendered and social inequalities that exist in most of society today. Otherwise we will continue to provide weak and short-term solutions to pervasive, coercive, and dangerous situations for countless women and children.

References

Advisory Council on the Status of Women (2010). Status report: Women in New Brunswick. Retrieved May 20, 2012, from http://www.acswcccf.nb.ca/media/acsw/files/english/2010report/Status%20Report%202010%20English.pdf.

Allen, N. E., Bybee, D. I., & Sullivan, C. M. (2004). Battered women’s multitude of needs: evidence supporting the need for comprehensive advocacy. Violence Against Women, 10(9), 1015–1035. doi:10.1177/1077801204267377.

Anderson, D. K., & Saunders, D. G. (2003). Leaving an abusive partner: an empirical review of predictors, the process of leaving, and psychological well-being. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 4(2), 163–191. doi:10.1177/1524838002250769.

Anderson, D. K., Saunders, D. G., Yoshihama, M., Bybee, D. I., & Sullivan, C. M. (2003). Long-term trends in depression among women separated from abusive partners. Violence Against Women, 9(7), 807–838. doi:10.1177/1077801203009007004.

Bancroft, W., & Vernon, S. (1995). The struggle for self-sufficiency: Participants in the self-sufficiency project talk about work, welfare, and their futures. Ottawa: SRDC.

Bell, H. (2003). Cycles within cycles: domestic violence, welfare, and low-wage work. Violence Against Women, 9(10), 1245–1262. doi:10.1177/1077801203255865.

Bonomi, A. E., Anderson, M. L., Rivara, F. P., & Thompson, R. S. (2009). Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research, 44(3), 1052–1067. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773-2009.00957.x.

Brush, L. D. (2000). Battering, traumatic stress, and welfare-to-work transition. Violence Against Women, 6(10), 1039–1065. doi:10.1177/10778010022183514.

Butler, S., Corbett, J., Bond, C., & Hastedt, C. (2008). Long-term TANF participants and barriers to employment: a qualitative study in Maine. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 35(3), 49–69.

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8.

Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women (CRIAW). (2005). Violence against women and girls. Ottawa: Author.

Cole, P. R. (2001). Impoverished women in violent partnerships: designing services to fit their reality. Violence Against Women, 7(2), 222–233. doi:10.1177/10778010122182415.

Crowne, S. S., Juon, H. S., Ensminger, M., Burrell, L., McFarlane, E., & Duggan, A. (2011). Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(6), 1282–1304. doi:10.1177/0886260510368160.

Davies, L., Ford-Gilboe, M., & Hammerton, J. (2009). Gender inequality and patterns of abuse post leaving. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 27–39. doi:10.1007/s10896-008-9204-5.

Davis, R. E. (2002a). Leave-taking experiences in the lives of abused women. Clinical Nursing Research, 11(3), 285–305. doi:10.1177/10573802011003005.

Davis, R. E. (2002b). “The strongest women”: exploration of the inner resources of abused women. Qualitative Health Research, 12(9), 1248–1263. doi:10.1177/104973230228248.

Department for International Development (DFID). (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: Author.

Duffy, L. (2010). Hidden heroines: lone mothers assessing community health using photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 11(6), 788–797. doi:10.1177/1524839908324779.

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Work, welfare, and single mothers’ economic survival strategies. American Sociological Review, 62(2), 253–266. Retrieved from http://www.jstor/stable/2657303.

Fleury, R. E., Sullivan, C. M., & Bybee, D. I. (2000). When ending the relationship does not end the violence. Violence Against Women, 6(12), 1363–1383. doi:10.1177/10778010022183695.

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wuest, J., & Merritt-Gray, M. (2005). Strengthening capacity to limit intrusion: theorizing family health promotion in the aftermath of woman abuse. Qualitative Health Research, 15(4), 477–501. doi:10.1177/1049732305274590.

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wuest, J., Varcoe, C., & Merritt-Gray, M. (2006). Developing an evidence-based health advocacy intervention for women who have left an abusive partner. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 38(1), 147–167.

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wuest, J., Varcoe, C., Davies, L., Merritt-Gray, M., Campbell, J., & Wilk, P. (2009). Modelling the effects of intimate partner violence and access to resources on women’s health in the early years after leaving an abusive partner. Social Science & Medicine, 68(6), 1021–1029. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2001.01.03.

Gennetian, L. A. (2003). Welfare policies and domestic abuse among single mothers: experimental evidence from Minnesota. Violence Against Women, 9(10), 1171–1190. doi:10.1177/1077801203255846.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., Magnuson, K., Gennetian, L. A., & Duncan, G. J. (2005). Employment and the risk of domestic abuse among low-income women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1149–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00207.x.

Human Development Council. (2012). Child poverty report card. Saint John: Author.

Humphreys, J., Cooper, B. A., & Miaskowski, C. (2010). Differences in depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and lifetime trauma exposure in formerly abused women with mild versus moderate to severe chronic pain. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(12), 2316–2338. doi:10.1177/0886260509354882.

Katula, S. (2012). Creating a safe haven for employees who are victims of domestic violence. Nursing Forum, 47(2), 217–225. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.2012.00278.x.

Kimerling, R., Alvarez, J., Pavao, J., Mack, K. P., Smith, M. W., & Baumrind, N. (2009). Unemployment among women: examining the relationship of physical and psychological intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(3), 450–463. doi:10.1177/0886260508317191.

Klumb, P. L., & Lampert, T. (2004). Women, work, and well-being 1950-2000: a review and methodological critique. Social Science & Medicine, 58(6), 1007–1024. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00262-4.

Kneipp, S. M. (2002). The relationships among employment, paid sick leave, and difficulty obtaining health care of single mothers with young children. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 3(1), 20–30. doi:10.1177/152715440200300104.

Kulkarni, S., Bell, H., & Wylie, L. (2010). Why don’t they follow through? intimate partner survivors’ challenges in accessing health and social services. Family & Community Health, 33(2), 94–105. doi:10.1197/FCH.06013e3181d59316.

Kwesiga, E., Bell, M. P., Pattie, M., & Moe, A. M. (2007). Exploring the literature on relationships between gender roles, intimate partner violence, occupational status, and organizational benefits. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(3), 312–326. doi:10.1177/0886260502695381.

Lempert, L. B. (1996). Women’s strategies for survival: developing agency in abusive relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 11(3), 269–289. doi:10.1007/BF02336945.

Letourneau, N., Duffy, L., & Duffet-Leger, L. (2012). Mothers affected by domestic violence: intersections and opportunities with the justice system. Journal of Family Violence, 27(6), 585–596. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9451-3.

Lindhorst, T., Oxford, M., & Gillmore, M. R. (2007). Longitudinal effects of domestic violence on employment and welfare outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(7), 812–828. doi:10.1177/0886260507301477.

Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., Johnson, C., & Chao, W. (1997). Married and recently divorced mothers’ stressful events and distress: tracing change across time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59(1), 219–232. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/353674.

Lutenbacher, M., Cohen, A., & Mitzel, J. (2003). Do we really help? perspectives of abused women. Public Health Nursing, 20(1), 56–64. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20108.x.

Macy, R. J., Nurius, P. S., Kernic, M. A., & Holt, V. L. (2005). Battered women’s profiles associated with service help-seeking efforts: illuminating opportunities for intervention. Social Work Research, 29(3), 137–150. doi:10.1093/swr/29.3.137.

Merritt-Gray, M., & Wuest, J. (1995). Counteracting abuse and breaking free: the process of leaving revealed through women’s voices. Health Care for Women International, 16(5), 399–412. doi:10.1080/07399339509516194.

Moe, A. M., & Bell, M. P. (2004). Abject economics: the effects of battering and violence on women’s work and employability. Violence Against Women, 10(1), 29–55. doi:10.1177/1077801203256016.

Mullan-Harris, K. (1996). Life after welfare: women, work, and repeat dependency. American Sociological Review, 61(3), 407–426. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2096356.

Murray, J., & Ferguson, M. (2002). Women in transition out of poverty. Ottawa: WEDC.

Pennington-Zoellner, K. (2009). Expanding ‘community’ in the community response to intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 24(8), 539–545. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9252-5.

Perrin, N. A., Yragui, N. L., Hanson, G. C., & Glass, N. (2011). Patterns of workplace supervisor support desired by abused women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(11), 2264–2284. doi:10.1177/0886260510383025.

Plichta, S. B. (2004). Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(11), 1296–1323. doi:10.1177/0886260504269895.

Pollack, K., Austin, W., & Grisso, J. A. (2010). Employee assistance programs: a workplace resource to address intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(12), 729–733. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1495.

Pyles, L., & Banerjee, M. M. (2010). Work experiences of women survivors: insights from the capabilities approach. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 25(1), 43–55. doi:10.1177/0886109909354984.

Raphael, J. (1999). Keeping women poor. In R. Brandwein (Ed.), Battered women, children, and welfare reform (pp. 31–43). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Riger, S., & Staggs, S. L. (2004). Welfare reform, domestic violence, and employment: what do we know and what do we need to know? Violence Against Women, 10(9), 961–990. doi:10.1177/1077801204267464.

Rollins, C., Glass, N. E., Perrin, N. A., Billhardt, K. A., Clough, A., Barnes, J., & Bloom, T. L. (2012). Housing instability is as strong a predictor of poor health outcomes as level of danger in an abusive relationship: findings from the SHARE study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(4), 623–643. doi:10.1177/0886260511423241.

Rothman, S., Hathaway, J., Stidsen, A., & de Vries, H. (2007). How employment helps female victims of intimate partner violence: a qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(2), 136–143. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.136.

Samuels-Dennis, J. (2006). Relationship among employment status, stressful life events, and depression in single mothers. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 38(1), 58–80.

Samuels-Dennis, J., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wilk, P., Avison, W. R., & Ray, S. (2010). Cumulative trauma, personal and social resources, and post-traumatic stress symptoms among income-assisted single mothers. Journal of Family Violence, 25(6), 603–617. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9323-7.

Scarbrough, J. W. (2001). Welfare mothers’ reflections on personal responsibility. Journal of Social Issues, 57(2), 261. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00212.

Shobe, M. A., & Dinemann, J. (2008). Intimate partner violence in the United States: an ecological approach to prevention and treatment. Social Policy & Society, 7(2), 185–195. doi:10.1017/S1474746407004137.

Human Resources and Skill Development Canada (2008). Low income in Canada: 2000-2006 using the Market Basket Measure - October 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2012, from http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/publications_resources/research/categories/inclusion/2008/sp-864-10-2008/page08.shtm.

Staggs, S. L., & Riger, S. (2005). Effects of intimate partner violence on low-income women’s health and employment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 133–145. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-6238-1.

Staggs, S. L., Long, S. M., Mason, G. E., Kirshnan, S., & Riger, S. (2007). Intimate partner violence. social support, and employment in the post-welfare reform era. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(3), 345–365. doi:10.1177/0886260506295388.

Statistics Canada. (2006). Family structure lone parents. Retrieved March 30, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/famil121a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2009). Salary lone fathers/mothers. Retrieved March 30, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/famil05a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2010a). Work lost due to illness (men). Retrieved March 30, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/health47b-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2010b). Work loss to illness (women). Retrieved March 30, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/health47c-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2011a). Reasons for part time work (men). Retrieved March 29, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/labor63b-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2011b). Reasons part time work (women). Retrieved March 30, 2012, from http://www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/labor63c-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2012). Population of census metropolitan areas. Retrieved June 25, 2012, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo05a-eng.htm.

Swanberg, J., Macke, C., & Logan, T. K. (2007). Working women making it work: intimate partner violence, employment, and workplace support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(3), 292–311. doi:10.1177/0886260506295387.

Swanberg, J., Ojha, M., & Macke, C. (2012). State employment protection statutes for victims of domestic violence: public policy’s response to domestic violence as an employment matter. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(3), 587–613. doi:10.1177/0886260511421668.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence. Findings from the national violence women survey. Washington: Department of Justice.

Tolman, R. M., & Rosen, D. (2001). Domestic violence in the lives of women receiving welfare: mental health, substance dependence, and economic well-being. Violence Against Women, 7(2), 141–158. doi:10.1177/1077801201007002003.

Tutty, L. (2006). Effective practices in sheltering women leaving violence in intimate partner relationships. Phase II report. Toronto: YWCA.

VandeWeerd, C., Coulter, M., & Mercado-Crespo, M. (2011). Female intimate partner violence victims and labor force participation. Partner Abuse, 2(2), 147–165. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.2.2.147.

Varcoe, C. (1996). Theorizing oppression: implications for nursing research on violence against women. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 28(1), 61–78.

Varcoe, C. (2008). Inequality, violence, and women’s health. In B. S. Bolaria & H. Dickinson (Eds.), Health, illness, and health care in Canada (4th ed., pp. 259–282). Toronto: Nelson.

Walker, R., Logan, T. K., Jordan, C. E., & Campbell, J. C. (2004). An integrative review of separation in the context of victimization: consequences and implications for women. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 5(2), 143–193. doi:10.1177/1524838003262333.

Wang, C. (1999). Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8(2), 185–192.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309.

Wang, C., Wu, K. Y., Zhan, W. T., & Carovano, K. (1998). Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy. Health Promotion International, 13(1), 75–86. doi:10.1093/heapro/13.1.75.

World Health Organization. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: Author.

Wuest, J., & Merritt-Gray, M. (1999). Not going back: sustaining the separation in the process of leaving abusive relationships. Violence Against Women, 5(2), 110–133. doi:10.1177/1077801299005002002.

Wuest, J., Ford-Gilboe, M., Merritt-Gray, M., & Berman, H. (2003). Intrusion: the central problem for family health promotion among children and single mothers after leaving an abusive partner. Qualitative Health Research, 13(5), 597–622. doi:10.1177/1049732303013005002.

Wuest, J., Ford-Gilboe, M., Merritt-Gray, M., & Lemire, S. (2006). Using grounded theory to generate a theoretical understanding of the effects of child custody policy on women’s health promotion in the context of intimate partner violence. Health Care for Women International, 27(6), 490–512. doi:10.1080/07399330600770221.

Wuest, J., Ford-Gilboe, M., Merritt-Gray, M., Varcoe, C., Lent, B., Wilk, P., & Cambell, J. (2009). Abuse-related injury and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as mechanisms of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Pain Medicine, 10(4), 739–747. doi:10.1111/j.526.4637.2009.00624.x.

Zweig, J. M., Schlichter, K. A., & Burt, M. R. (2002). Assisting women victims of violence who experience multiple barriers to services. Violence Against Women, 8(2), 162–180. doi:10.1177/10778010222182991.

Acknowledgments

Sincere appreciation to the women who participated as co-researchers in this study and taught me so much, as well to our supportive community partners and research assistant, Cathy Kelly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duffy, L. Achieving a Sustainable Livelihood After Leaving Intimate Partner Violence: Challenges and Opportunities. J Fam Viol 30, 403–417 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9686-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9686-x